Abstract

Manual therapists question integrating manual lymphatic drainage techniques (MLDTs) into conventional treatments for athletic injuries due to the scarcity of literature concerning musculoskeletal applications and established orthopaedic clinical practice guidelines. The purpose of this systematic review is to provide manual therapy clinicians with pertinent information regarding progression of MLDTs as well as to critique the evidence for efficacy of this method in sports medicine. We surveyed English-language publications from 1998 to 2008 by searching PubMed, PEDro, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, and SPORTDiscus databases using the terms lymphatic system, lymph drainage, lymphatic therapy, manual lymph drainage, and lymphatic pump techniques. We selected articles investigating the effects of MLDTs on orthopaedic and athletic injury outcomes. Nine articles met inclusion criteria, of which 3 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We evaluated the 3 RCTs using a validity score (PEDro scale). Due to differences in experimental design, data could not be collapsed for meta-analysis. Animal model experiments reinforce theoretical principles for application of MLDTs. When combined with concomitant musculoskeletal therapy, pilot and case studies demonstrate MLDT effectiveness. The best evidence suggests that efficacy of MLDT in sports medicine and rehabilitation is specific to resolution of enzyme serum levels associated with acute skeletal muscle cell damage as well as reduction of edema following acute ankle joint sprain and radial wrist fracture. Currently, there is limited high-ranking evidence available. Well-designed RCTs assessing outcome variables following implementation of MLDTs in treating athletic injuries may provide conclusive evidence for establishing applicable clinical practice guidelines in sports medicine and rehabilitation.

KEYWORDS: Edema, Lymphatic Pump Techniques, Lymphatic Therapy, Manual Lymph Drainage, Manual Therapy

Manual lymphatic drainage techniques (MLDTs) are unique manual therapy interventions that may be incorporated by medical practitioners as well as allied health clinicians into rehabilitation paradigms for the treatment of somatic dysfunctions and pathologies1–5. The theoretical bases for using such modes of manual therapy are founded on the following concepts: 1) stimulating the lymphatic system via an increase in lymph circulation, 2) expediting the removal of biochemical wastes from body tissues, 3) enhancing body fluid dynamics, thereby facilitating edema reduction, and 4) decreasing sympathetic nervous system responses while increasing parasympathetic nervous tone yielding a non-stressed body-framework state5. The physiological and biomechanical effects of MLDTs on lymphatic system dynamics in treating ill or injured patients have long been of interest to osteopathic, allied health, complementary, and alternative medicine practitioners5,6 although it was not until the 19th century that researchers began to theorize concepts regarding direct influences of human movement and manual inerventions, predominantely massage, on the lymphatic system1. Subsequent clinical scientists focused their efforts on advancing investigations on the biodynamic properties of the lymphatic system from which treatment interventions were developed for therapeutic purposes1,3.

Andrew Taylor Still, DO, proposed the initial principles of MLDTs with the advent of osteopathic manipulative techniques in the late 1800s1. Still's appreciation for the complexities of lymphatic system functionality influenced many of the ensuing pracitioners who evolved this body of work. Elmer D Barber, DO, a student at Still's American School of Osteopathy, was the first author to publish works on manual lymphatic pump techniques for the spleen, in 18981. Another pupil of Still's philosophies, Earl Miller, DO, instituted the manual thoracic pump technique in 19201. Emil Vodder, PhD, was an additional clinical scientist who contributed to the development and advancement of MLDTs1,7. Vodder focused his clinical research on gaining further insight into the treatment of various pathologies by manipulating the lymphatic system1,7. In his work with individuals afflicted by various health ailments, Vodder reported successful treatment results using his manual lymph drainage technique throughout the 1930s1,7. Vodder's treatment approach was similar to popular modes of Scandinavian massage therapies for that time period but it differed in that heavy pressure was discouraged and a light touch was substituted1,5,7. This has led to the advent of the current Vodder Method, which is used by various healthcare professionals in treating several edematous conditions1,7. Numerous other medical and allied health professionals, such as Bruno Chikly, MD, DO, have contributed to progressing the art and science of MLDTs, most notably with managing post-lymphadenectomy lymphoedema.

In contrast, the currently proposed criteria for successful management of most acute or chronic edematous conditions in allopathic-based orthopaedic sports medicine and rehabilitation have traditionally implemented cryotherapy, elevation, compressive dressings, suitable range-of-motion exercises, and applicable therapeutic modalities2,8. This commonly prescribed standard of care for injury to musculoskeletal tissues is often supplemented with bouts of oral anti-inflammatory analgesic medications2,8. These medications typically constitute non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs2,5,8, which have been the subject of increasing scrutiny and caution with the recent discovery of occasionally fatal side-effects.

Evidence-based practice is a common agenda in medical and allied health sciences, which serves to optimize rendering of health care services through the investigation of treatment interventions that yield positive patient outcomes for establishing clinical practice guidelines9,10. Use of MLDTs to improve functionality and maintain homeostasis of the lymphatic system is a topic that warrants critical appraisal for determining efficacy in sports medicine and rehabilitation. Hence, it is the purpose of this systematic review to present manual therapy clinicians with a synopsis of the history, theory, and application of MLDTs as well as to discuss current evidence that scrutinizes its efficacy in sports medicine.

Methods

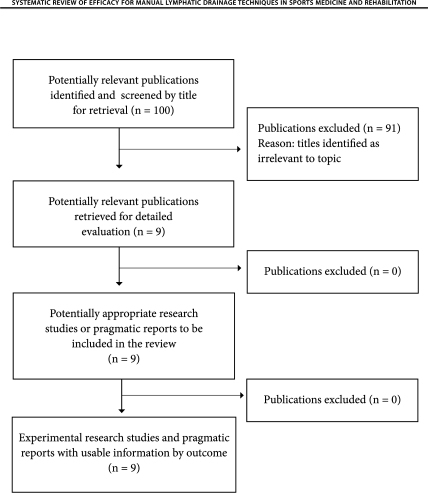

The elements of our clinical question were refined in a stepwise process employing the Participant, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) model (McMaster University, UK) (Figure 1). Manual lymph drainage is defined by MedlinePlus (United States National Library of Medicine) as “a light massage therapy technique that involves moving the skin in particular directions based on the structure of the lymphatic system. This helps encourage drainage of the fluid and waste through the appropriate channels.” This broad definition was used when surveying the relevant literature for our systematic review. Manual lymph drainage techniques reviewed included the Vodder Method and various lymphatic pumps, which demonstrate anatomical and physiological rationale supported by empirical evidence. Specialized concepts such as reflexology, craniosacral technique, and manual lymphatic mapping were not included due to the scarcity of reliable and valid evidence supporting these interventions.

FIGURE 1.

Description for components of the PICO model.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive survey of recent scientific articles in suitable peer-reviewed journals published between 1998 and 2008 was conducted. A series of literature searches used PubMed, PEDro, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library and SPORTDiscus electronic databases. The keywords consistently used were lymphatic system, lymph drainage, lymphatic therapy, manual lymph drainage, and lymphatic pump techniques. We screened the titles of all retrieved hits and identified potentially relevant articles by analyzing associated abstracts. Entire articles were obtained if we deemed the research study satisfied inclusion criteria. Additional publications were identified through manual searches of cited references for related articles retrieved.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of scientific publications that were complete articles with sufficient detail to extract the focal attributes of the research studies. Articles were eligible for inclusion in the critical appraisal if they were categorized as systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or cohort studies. Due to limited applicable original research studies, pragmatic pilot and case studies pertinent to musculoskeletal health as well as innovative animal-model experiments were also included. Patients enrolled in the research studies had to have suffered from medically diagnosed musculoskeletal ailments, which included bone fracture, acute ankle sprain, fibromyalgia, orthopaedic trauma, and Bell's palsy. Healthy humans participating in research studies that experimentally induced acute skeletal muscle damage following standardized exercise were also included. Furthermore, all research studies included in this systematic review used reliable measurement tools employed in the biomedical, health, and rehabilitation sciences.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles published in languages other than English or prior to 1998 were excluded. Research studies investigating therapies such as reflexology, craniosacral technique, and manual lymphatic mapping were also omitted. With the focus of this systematic review specific to treating orthopaedic and athletic injuries, investigations directed towards management of other somatic dysfunctions or pathologies, such as cancer and lymphoedema, were eliminated.

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

The following data were extracted from selected publications to assess the efficacy and effectiveness of MLDTs in sports medicine and rehabilitation as well as to analyze treatment protocols employed in retrieved research studies: experimental design; sampled population size; patients/participants treated; control group; mode of MLDT; MLDT regimen; clinician administering treatment; concomitant interventions; outcome measures. Methodological quality of all scientific articles was critically appraised in this review as delineated per the levels of evidence (May 2001) categorized by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) (Oxford, UK)9,10. Where applicable, selected RCT articles were further scrutinized with a validity score (PEDro scale).

Results

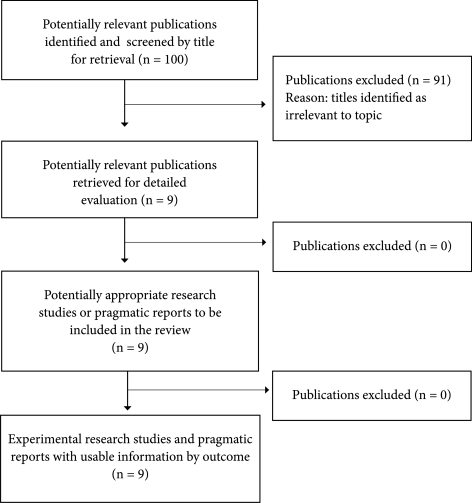

More than 100 titles were identified with the primary search in defined databases. However, the majority of the publications analyzed did not investigate the effects of MLDTs on musculoskeletal conditions in laboratory settings or clinical trials. Only nine articles were screened as potentially relevant for retrieval to a more detailed evaluation following analysis of associated abstracts (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

QUORUM statement flow diagram illustrating the results of our literature search strategy.

Diverse modes of MLDTs and outcome measurement tools were noted in the research studies. Three relevant human-subject research studies were selected for critical appraisal. One research study was classified as a RCT11; it experimentally induced acute skeletal muscle damage after a standardized exercise protocol. The control group in this experiment11 received no treatment. Another RCT12 evaluated MLDT intervention following radial wrist fracture. In this instance, the MLDT group's contralateral extremity served as an internal non-treatment control and differences in bilateral limb volume were compared against a group who received the standard of care for a similar injury12. A prospective randomized controlled nonconsecutive clinical trial2 was also identified assessing acute ankle sprains. In this research study, comparisons were made to a control group of participants who had sustained a similar injury and received the standard of care2.

The RCTs2,11,12 obtained a score of 6 or higher as scrutinized by the PEDro scale. All of the research studies lost two points as the result of not blinding the participants receiving and the therapists administering the MLDT treatments. However, it is inherent in manual therapy investigations that blinding is compromised because the patient perceives the intervention during treatment. Likewise, it is difficult for a manual therapist to administer a sham or placebo intervention without being cognizant of such during treatment. The validity scoring of the RCTs per the PEDro scare are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Validity scores of RCTs (PEDro scale).

| Authors, Year and Experimental Design | Schillinger et al11 RCT | Harén et al12 RCT | Eisenhart et al2 RCT (Low-quality) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ∗ Eligibility criteria were specified. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Subjects were randomly allocated to groups (in a crossover study, subjects were randomly allocated in order in which treatments were received). | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Allocation was concealed. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4. The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. There was blinding of all subjects. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome. | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Measures of at least one key variable outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups. | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 9. All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key variable outcome were analyzed by “intention to treat.” | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 10. The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11. The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome. | 1 | 1 | 1 |

This item is not used to calculate the validity (PEDro) score.

A pilot study evaluating the effect of MLDTs on fibromyalgia was also included13. Furthermore, two multimodal case studies were chosen pertaining to traumatic musculoskeletal injury4 and neuromuscular pathology14. Three patient animal-model experiments15–17 were also included as they represented innovative basic science investigations in the theoretical domain of proposed MLDT biomechanisms. The characteristics of the retrieved articles are listed in Table 2. A summary of the selected literature reviewed is presented in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of articles retrieved.

| Level of Evidence (CEBM) | Experimental Design | Validity Score (PEDro Scale) | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lb | RCT | 6/10 | Schillinger et al11 |

| lb | RCT | 7/10 | Harén et al12 |

| 2b | Prospective randomized controlled clinical trial | 6/10 | Eisenhart et al2 |

| 4 | Case study | N/A | Weiss4 |

| 4 | Pilot study | N/A | Asplund13 |

| 4 | Case study | N/A | Lancaster & Crow14 |

| 5 | Animal model | N/A | Déry et al15 |

| 5 | Animal model | N/A | Knott et al16 |

| 5 | Animal model | N/A | Hodge et al17 |

|

|||

TABLE 3.

Summary of literature reviewed.

| Author(s), Year | Participants | MLDT(s) | Results and Outcomes |

| Schillinger et al11 | 14 recreational athletes (7 women, 7 men) randomized into treatment and control groups of 7 participants undergoing a graded exercise test to anærobic threshold; consecutive enrollment of participants | Manual Lymph Drainage (Two 45-min sessions, one directly after exercise and a second 24 hrs post) administered by an experienced therapist (not specified) | Significant decrease of: aspartate aminotransferase in the treatment group (12.4 ± 3.8 IU.ml−1 to 10.8 ± 5.9 IU.ml−1) compared to control group (13.5 ± 3.1 IU.ml−1 to 14.5 ± 4.8 IU.ml−1), P < 0.05; lactate dehydrogenase in the treatment group (229.0 ± 64.7 IU.ml−1 to 177.7 ± 54.1 IU.ml−1) compared to control group (220.7 ± 28.8 IU.ml−1 to 220.7 ± 28.8 IU.ml−1), P < 0.05 measured directly after and 48 hrs post-exercise |

| Harén et al12 | 26 patients treated by external fixation of a distal radial fracture randomized into treatment (n = 12) and control (n = 14) groups; consecutive enrollment of participants | Vodder Method (Ten 45-min treatments, 18 days post-op over 6 weeks) administered by one occupational therapist | Significant decrease in volume measures between the injured and uninjured hands following removal of an external fixation device in the treatment (39 ± 12 ml) compared to control (64 ± 41 ml) group 3 days after, P = 0.04 and in the treatment (27 ± 9 ml) compared to control (50 ± 35 ml) group 17 days after, P = 0.02 |

| Eisenhart et al2 | 55 patients admitted to emergency department with an acute ipsilateral 1° or 2° ankle sprain randomized into treatment (n = 28) and control (n = 27) groups; nonconsecutive enrollment of participants | Lymphatic drainage technique as a component of osteopathic manipulative treatment, which as an ensemble consisted of one 10- to 20-min session administered by one doctor of osteopathy in an emergency department | Significant decrease of: edema compared before (2.07 ± 1.3 cm) and 5 to 7 days after (0.91 ± 1.0 cm), P < 0.001 measuring delta circumference (injured-contralateral); pain compared before (6.50 ± 2) and 5 to 7 days after (4.1 ± 1.7), P < 0.001 measured by a visual analog scale (1 to 10) |

| Weiss4 | 1 male patient with leg edema following orthopædic trauma | Manual Lymph Drainage (1 year following injury, 3 treatments per week over 7 weeks for 45 to 60 min) as a component of complete decongestive physiotherapy administered by a physical therapist | Upon discharge from therapy, leg edema decreased 74% and two wound areas decreased 89%; 10 weeks following treatment, leg edema decreased 80.9%, one wound healed, and a second wound area decreased 93% |

| Asplund13 | 17 female patients with chronic fibromyalgia | Vodder Method (12 treatments over 4 weeks for 1 hr) administered by a therapist (not specified) | Significant improvements in: pain at 4 weeks (P < 0.001) as well as 3 (P < 0.001) and 6 (P < 0.05) months following; stiffness at 4 weeks (P < 0.001) as well as 3 months following (P < 0.01); sleep at 4 weeks (P < 0.001); sleepiness at 4 weeks (P < 0.001) as well as 3 and 6 months following (P < 0.01); well-being at 4 weeks (P < 0.001) as well as 3 months (P < 0.001) following measured by visual analog scales |

| Lancaster and Crow14 | 1 female patient with idiopathic Bell's palsy | Thoracic pump technique as a component of osteopathic manipulative treatment, which as an ensemble consisted of two 20-min sessions 1 week apart administered by a doctor of osteopathy | Complete relief of patient's unilateral facial nerve paralysis within 2 weeks while eschewing pharmacologic treatments |

| Déry et al15 | 63 Sprague-Dawley anesthetized rats (32 treatment, 31 control) by doctor of osteopathy | Lymph flow enhancing treatment (5 min per hour over 15 hrs) administered | Rate of appearance for fluorescent probe assessing lymph uptake greater during first nine hours of experiment in the treatment compared to control group |

| Knott et al16 | 5 healthy adult male mongrel dogs, surgically instrumented | Abdominal and thoracic pump techniques (Two 30-sec sessions at 1 Hz) administered by a doctor of osteopathy | Significant increase in lymphatic flow from 1.57 ± 0.20 mL·min−1 to 4.80 ± 1.73 mL·min−1 with abdominal pump techniques (P < 0.05) and from 1.20 ± 0.41 mL·min−1 to 3.45±1.61 mL·min−1 with thoracic pump techniques (P < 0.05) |

| Hodge et al17 | 8 healthy adult mongrel dogs, surgically instrumented | Lymphatic pump technique (abdominal) (Rate of 1 compression per sec for 8 min) administered by a doctor of osteopathy | Lymphatic pump technique (abdominal) significantly increased leukocyte count from 4.8 ± 1.7 × 106 cells/ml of lymph to 11.8 ± 3.6 × 106cells/ml (P < 0.01); lymph flow from 1.13 ± 0.44 ml/min to 4.14 ± 1.29 ml/min (P < 0.05); leukocyte flux from 8.2 ± 4.1 × 106to 60 ± 25 × 106 total cells/min (P < 0.05) |

Discussion

Foundations for Theory and Application to Evidence-Based Practice

Modern anatomists, physiologists, and medical practitioners consider the lymphatic system the crux of regulating homeostasis in the human organism1,3,5,6. Appropriate lymph dynamics are fundamental to an adequate immune system as well as facilitating cellular processes and by-product elimination2,3,6. However, congestion of the lymphatic system may arise as the result of various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which include restricted hemodynamics due to focal ischemia, systemic illnesses, tissue injuries, overexposure to adverse chemicals, food allergies or sensitivities, lack of physical movement or exercise, stress, and tight-fitting clothing5. In order to address stagnant lymph or impaired lymph dynamics, administration of MLDTs to the limbs has been proposed to aid transport of lymph from the extremities3,5–7. Furthermore, complementary lymphatic pump techniques are thought to augment lymph passage through larger, more extensive lymphatic channels in the thorax for the filtration and removal of pathological fluids, inflammatory mediators, and waste products from the interstitial space3,5,6. The majority of MLDTs are considered safe but contraindications typically include major cardiac pathology, thrombosis or venous obstruction, hemorrhage, acute enuresis, and malignant tumors3,5,18. Several modes of MLDTs, such as the Vodder Method and lymphatic pump techniques, are commonly practiced in osteopathic, complementary, and alternative medicine as well as physical rehabilitation for treating the lymphatic system. With applications specific to orthopaedic injury, MLDTs are proposed to stimulate the superficial component of the lymphatic system for aiding resolution of post-traumatic edema5. To an extent, the clinical effectiveness of such interventions has been suggested via pragmatic studies using MLDTs in physical rehabilitation interventions for musculoskeletal traumatic injuries4 and chronic conditions13 as well as neuromuscular pathology or dysfunction14. Unfortunately, few basic, applied, or clinical research studies have been conducted that conclusively validate the proposed biophysical processes of MLDTs in humans5.

Conversely, several unique research studies have demonstrated evidence in animal models supporting the proposed biomechanisms underpinning MLDTs. Déry et al15 displayed increased measures of lymph uptake in a rat model subsequent to the application of a lymphatic pump technique. Furthermore, innovative studies by Knott et al16 and Hodge et al17 measured greater thoracic duct flow as well as leukocyte count respectively in a canine model with abdominal and thoracic lymphatic pump techniques. The laboratory techniques of Knott et al16 and Hodge et al17 specifically represent landmark contributions to this body of work by obtaining real-time indices for lymph mobilization with the implementation of MLDTs commonly applied in clinical osteopathic medical practice. Though the findings of Déry et al15, Knott et al16, and Hodge et al17 have supported proposed keystone theoretical concepts and suggested the potential efficacy of MLDTs in animal models, extrapolation of these findings to applicability in the human species is currently inconclusive.

Efficacy in Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation

Unfortunately, the literature regarding the influence of MLDTs for specific conditions encountered in conventional athletic injury rehabilitation is limited. To date, the most pertinent current research studies on the efficacy of MLDTs in sports medicine and rehabilitation are the work of Schillinger et al11, Eisenhart et al2, and Härén et al12. Several pilot13 and case studies4,14 have been published that suggest clinical effectiveness of MLDTs for several musculoskeletal conditions but they have failed to bolster the CEBM level of evidence and grade of recommendation supporting efficacy of such interventions in sports medicine and rehabilitation.

Schillinger et al11 conducted a randomized controlled trial that analyzed biochemical indices of structural skeletal muscle cell integrity upon the implementation of MLDTs following a bout of endurance treadmill running to anaerobic threshold. Compared to control participants who received no manual therapy interventions, the MLDT group displayed a statistically significant decrease in concentrations of blood lactate dehydrogenase and aspartate aminotransferase immediately following a treatment session and at a 48-hour follow-up. The observed decrease in serum levels of specific skeletal muscle enzymes following an MLDT intervention demonstrates the potential for expedited regenerative and repair mechanisms to skeletal muscle cell integrity following structural damage as the result of taxing loads associated with physical activity11. Eisenhart et al2 investigated the effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) on acute ankle sprains managed in an emergency department. Participants randomly assigned to the OMT group received lymphatic drainage techniques in conjunction with the current standard of care compared to a control group prescribed only the standard of care. Results of one OMT session produced statistically significant decreases in pain and edema. At the follow-up evaluation one week post-intervention, the OMT group displayed improvement in outcome measures for range of motion compared to the control group. Though the results of Eisenhart et al2 demonstrate potential MLDT efficacy for this orthopaedic injury commonly treated by physical rehabilitation specialists, the definitive contribution of lymphatic drainage techniques in a multimodal OMT paradigm is difficult to ascertain. However, this research study may serve as a springboard for subsequent investigations on the effect of MLDTs in treating commonly encountered orthopaedic conditions.

Härén et al12 conducted a prospective cohort research study that evaluated the efficacy of MLDTs following wrist bone fracture and subsequent treatment of the distal radius. In this experimental design, all enrolled patients received the standard of care for this condition with participants then randomized into MLDT and control groups. In addition to the standard of care, the MLDT group received 10 MLDT treatments. Härén et al12 reported that the MLDT group displayed statistically significantly decreased measures of hand volume suggesting less edema present in the injured extremity. This preliminary evidence supports efficacy of MLDTs in sports medicine and rehabilitation specific to managing wrist bone fractures. However, continued investigations with larger sample sizes are required to confirm and validate the results of the three aforementioned human research studies.

Applicable case and pilot studies have produced results that support the clinical effectiveness of incorporating MLDTs into multimodal treatment interventions for musculoskeletal4,13 and neuromuscular14 ailments. These positive outcomes include statistically significant decreases in pain13 as well as clinically significant reductions in edema4, improvements in wound healing4, and restorations of anatomical structure and physiological functions4,14. These pragmatic reports suggest that MLDTs are effective in a treatment paradigm when used in conjunction with other interventions. Although these results support the potential effectiveness of MLDTs for musculoskeletal conditions in a context that mirrors real-world clinical practice, unfortunately the specific contribution of MLDTs to these positive outcomes remains unknown. This is generally due to the research methods employed, i.e., predominately quasi-experimental designs, which rank low according to CEBM standards for ranking the levels of evidence and validity scores scrutinized by the PEDro scale9,10. Hence, these pragmatic studies fail to support efficacy, in the strictest terms, of MLDTs in sports medicine and rehabilitation19.

The strongest evidence from RCTs suggests that MLDTs may be efficacious in the resolution of enzyme serum levels associated with acute structural skeletal muscle cell damage11 as well as in the reduction of edema following wrist bone fracture of the distal radius12 and acute ankle sprain2. However, based on CEBM standards for ranking the levels of evidence, there is currently an insufficient and inconsistent ensemble of evidence to support a grade of recommendation on which to establish clinical practice guidelines for the use of MLDTs in rehabilitating athletic injuries.

Manual lymphatic drainage techniques remain a clinical art founded upon hypotheses, theory, and preliminary evidence. Researchers must strive to clarify the biophysical effects that underpin its various proposed therapeutic applications in the human organism. Randomized controlled trials and longitudinal prospective cohort studies are required to establish the efficacy of MLDTs in producing positive outcomes for patients rehabilitating from sports-related injuries. Researchers employing such experimental designs should use diligence in selecting specific modes of MLDTs to be incorporated in respective intervention regimens so that diverse forms of the therapy are avoided with investigated treatment protocols. The applied and clinical sciences research studies of Schillinger et al11, Eisenhart et al2, and Härén et al12 along with advanced basic science experimental methods implemented by Knott et al16 and Hodge et al17 may serve as groundwork references for future hybrid investigations in this domain of manual therapy. Once this facet of a proposed research paradigm has been established, the focus might expand to include determination of optimal treatment durations as well as the most effective rate and frequency of administered MLDTs for the development of a defined intervention algorithm.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Daniel Monthley, MS, ATC, for his assistance in reviewing and editing drafts of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chikly BJ. Manual thechniques addressing the lymphatic system: Origins and development. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:457–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenhart AW, Gaeta TJ, Yens DP. Osteopathic manipulative treatment in the emergency department for patients with acute ankle sprains. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103:417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesho EP. An overview of osteopathic medicine. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:477–484. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.6.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss JM. Treatment of leg edema and wound=s in a patient with severe musculoskeletal injuries. Phys fler. 1998;78:1104–1113. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.10.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korosec BJ. Manual lymphatic drainage therapy. Home Health Care Mang Pract. 2004;17:499–511. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson MM. Mechanisms of change: Animal models in osteopathic research. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:593–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasseroller RG. The Vodder school: The Vodder method. Cancer. 1998;83:2840–2842. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12b+<2840::aid-cncr37>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birrer RB, Fani-Salek MH, Totten VY, Herman LM, Polti V. Managing ankle injuries in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:751–770. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeon PO, Medina JM, Hertel J. Hierarchy of evidence–based clinical research in sports medicine. Athletic fler Today. 2006;11:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medina JM, McKeon PO, Hertel J. Rating the levels of evidence in sports medicine research. Athletic fler Today. 2006;11:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schillinger A, Koening D, Haefele C, et al. Effect of manual lymph drainage on the course of serum levels of muscle enzymes after treadmill exercise. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:516–520. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000219245.19538.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Härén K, Backman C, Wiberg M. Effect of manual lymph drainage as described by Vodder on œdema of the hand after fracture of the distal radius: A prospective clinical study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2000;34:367–372. doi: 10.1080/028443100750059165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asplund R. Manual lymph drainage therapy using light massage for fibromyalgia sufferers: A pilot study. Phys fler. 2003;7:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancaster DG, Crow WT. Osteopathic manipulative treatment of a 26-year-old woman with Bell's palsy. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Déry MA, Yonuschot G, Winterson BJ. The effects of manually applied intermittent pulsation pressure to a rat ventral thorax on lymph transport. Lymphology. 2000;33:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knott EM, Tune JD, Stoll ST, Downey HF. Increased lymphatic flow in the thoracic duct during manipulative intervention. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:447–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodge LM, King HH, Williams AG, et al. Abdominal lymphatic pump treatment increases leukocyte count flux in thoracic duct lymph. Lymph Res Biol. 2007;5:127–134. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ernst E. The safety of massage therapy. Rheumatology. 2003;42:1101–1106. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz JM, Cleland J. Effectiveness versus efficacy: More than a debate over language. J Orthop Sports Phys fler. 2003;33:163–165. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.4.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]