Abstract

Aims

In acute coronary syndromes (ACS), the optimal revascularization strategy for unprotected left main coronary disease (ULMCD) has been little studied. The objectives of the present study were to describe the practice of ULMCD revascularization in ACS patients and its evolution over an 8-year period, analyse the prognosis of this population and determine the effect of revascularization on outcome.

Methods and results

Of 43 018 patients enrolled in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) between 2000 and 2007, 1799 had significant ULMCD and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) alone (n = 514), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) alone (n = 612), or no revascularization (n = 673). Mortality was 7.7% in hospital and 14% at 6 months. Over the 8-year study, the GRACE risk score remained constant, but there was a steady shift to more PCI than CABG over time. Patients undergoing PCI presented more frequently with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), after cardiac arrest, or in cardiogenic shock; 48% of PCI patients underwent revascularization on the day of admission vs. 5.1% in the CABG group. After adjustment, revascularization was associated with an early hazard of hospital death vs. no revascularization, significant for PCI (hazard ratio (HR) 2.60, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.62–4.18) but not for CABG (1.26, 0.72–2.22). From discharge to 6 months, both PCI (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.23–0.85) and CABG (0.11, 0.04–0.28) were significantly associated with improved survival in comparison with an initial strategy of no revascularization. Coronary artery bypass graft revascularization was associated with a five-fold increase in stroke compared with the other two groups.

Conclusion

Unprotected left main coronary disease in ACS is associated with high mortality, especially in patients with STEMI and/or haemodynamic or arrhythmic instability. Percutaneous coronary intervention is now the most common revascularization strategy and preferred in higher risk patients. Coronary artery bypass graft is often delayed and performed in lower risk patients, leading to good 6-month survival. The two approaches therefore appear complementary.

Keywords: Left main disease, Acute coronary syndrome

Introduction

The optimal revascularization strategy for unprotected left main coronary disease (ULMCD) is the subject of ongoing debate. In theory, it is one of the best indications for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, mainly because randomized studies performed decades ago demonstrated a reduction in mortality with CABG vs. conservative medical treatment.1,2 However, since then, the feasibility of unprotected left main percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with bare-metal stents has been reported3–5 followed, more recently, by favourable outcomes with drug-eluting stents.6–9 Data on the management of ULMCD are available from a limited number of observational studies, all of which had small sample sizes; a recent pooled analysis identified 16 of these studies, involving a total of 1278 patients with ULMCD, and showed a 2.3% hospital mortality rate in patients who underwent PCI with drug-eluting stents.10 Propensity score matching methods have also been used and demonstrated similar outcomes for PCI and CABG revascularization in ULMCD.11,12 Randomized comparisons of PCI vs. CABG in patients with ULMCD are limited to the left main stenting trial, in which 105 patients were randomized to either strategy,13 and to the ULMCD subgroup in the recently presented SYNTAX (SYNergy Between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) study.14

In most of these studies, especially when randomizing or comparing matched cohorts, the highest risk patients were excluded. Indeed, acute (e.g. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)) or serious (e.g. cardiogenic shock) cases, the elderly, and patients with comorbid conditions are all more likely to be treated with PCI, while those with complex anatomies or ULMCD with concomitant multivessel disease are more likely to undergo CABG. We explored the treatment strategies applied to ULMCD in unselected patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a high-risk clinical situation that impacts treatment choices and clinical outcomes in a way not seen in studies that dealt mainly with stable and scheduled cases.

Methods

Full details of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) methods have been published.15–17 In brief, GRACE was designed to reflect an unselected population of patients with ACS, irrespective of geographic region. A total of 14 countries in North and South America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have contributed data to this observational study.

Adult patients (≥18 years) admitted with a presumptive diagnosis of ACS at participating hospitals were potentially eligible for this study. Eligibility criteria were a clinical history of ACS accompanied by at least one of the following: electrocardiographic changes consistent with ACS, serial increases in biochemical markers of cardiac necrosis (CK-MB, creatine phosphokinase, or troponin), and documented coronary artery disease. Patients with non-cardiovascular causes for the clinical presentation, such as trauma, surgery, or aortic aneurism, were excluded. Patients were followed up at approximately 6 months by telephone, clinic visits, or through calls to their primary care physician to ascertain the occurrence of several long-term outcomes. Where required, study investigators received approval from their local hospital ethics or institutional review board for the conduct of this study.

To enrol an unselected population of patients with ACS, sites were encouraged to recruit the first 10 to 20 consecutive eligible patients each month. Regular audits were performed at all participating hospitals. Data were collected by trained study co-ordinators using standardized case report forms. Demographic characteristics, medical history, presenting symptoms, duration of pre-hospital delay, biochemical and electrocardiographic findings, treatment practices, and a variety of hospital outcome data were collected. Standardized definitions of all patient-related variables, clinical diagnoses, and hospital complications and outcomes were used.15 All cases were assigned to one of the following categories: STEMI, non-STEMI, or unstable angina.

Patients were diagnosed with STEMI when they had new or presumed new ST-segment elevation ≥1 mm seen in any location, or new left bundle branch block on the index or subsequent electrocardiogram with at least one positive cardiac biochemical marker of necrosis (including troponin measurements, whether qualitative or quantitative). In cases of non-STEMI, at least one positive cardiac biochemical marker of necrosis without new ST-segment elevation seen on the index or subsequent electrocardiogram had to be present. Unstable angina was diagnosed when serum biochemical markers indicative of myocardial necrosis in each hospital's laboratory were within the normal range. The main outcome measure of the present study was mortality evaluated in-hospital and at 6 months' follow-up. Other ischaemic and haemorrhagic endpoints were evaluated at same time points. Full definitions can be found on the GRACE web site at www.outcomes.org/grace. Hospital-specific feedback regarding patient characteristics, presentation, management, and outcomes are provided to each centre on a quarterly basis in the form of written reports.

Statistical analysis

Univariate comparisons were performed using Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables, the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel trend test for Killip class (ordinal), and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier curves show unadjusted cumulative mortality and stroke from hospital admission to 6 months according to the revascularization group. The groups were treated as time-varying covariates, so that if a patient underwent CABG on day 4 after admission they were counted as not having revascularization performed on days 0–3, and as having had CABG surgery from day 4 onwards.

Adjusted results for mortality were calculated from multiple Cox regression models, treating PCI and CABG as time-varying covariates. The results were adjusted for the GRACE risk score variables (age, cardiac arrest at presentation, Killip class, ST deviation on presentation, initial creatinine concentration, positive initial cardiac markers, heart rate, systolic blood pressure).17 In addition, we adjusted for significant Q-waves on presentation and mechanical ventilation. The Cox model included a time-varying indicator variable of whether an observation for a patient on day t occurs in hospital or after discharge. We then formed an interaction between this variable and revascularization to estimate distinct hazard ratios (HRs) for revascularization with in-hospital and post-discharge mortality.18 We ran all analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient population

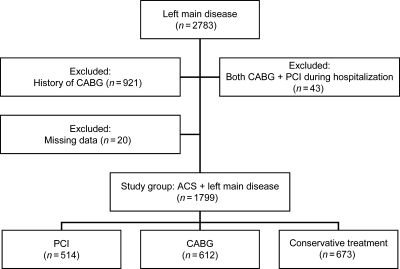

This analysis is based on 43 018 patients who presented to 106 hospitals with an ACS between 2000 and 2007, had complete 6-month follow-up data available, and underwent cardiac catheterization. Of these patients, 2783 had significant (>50% stenosis) left main disease identified on the coronary angiogram. To exclude patients with protected left main disease, all individuals with a history of CABG were excluded (n = 921, Figure 1). Patients with missing information on revascularization and those who underwent both types of revascularization during the index admission were also excluded. A total of 1799 patients with left main disease were therefore included in the analysis, and were categorized according to the initial treatment strategy as follows: PCI alone (n = 514), CABG alone (n = 612), or no revascularization during hospitalization (n = 673).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Baseline demographics

The median age of the population was 70 (inter-quartile range 60–78) years and 498 (28%) were women. The population was generally high risk, with 603 (40%) being above 75 years, 472 (26%) with a history of myocardial infarction, 158 (8.9%) with prior stroke, and 168 (9.4%) with renal insufficiency. The most severe patients presented with ongoing STEMI (n = 627, 35%, had new ST elevation or left bundle branch block), heart failure (n = 404, 23% had Killip class >I), and/or cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock (59, 3.4%). Most (n = 1688, 94%) patients had coronary lesions in addition to left main disease (Table 1). The median GRACE risk score17 was 141 (inter-quartile range 117–169) (equivalent to an approximate 3% risk of in-hospital death).

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics and clinical presentation

| Total population |

PCI (n = 514) |

CABG (n = 612) |

Neither (n = 673) |

P* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | ||

| Demographic | |||||||||||||

| Women | 498 | 1795 | 28 | 140 | 511 | 27 | 160 | 612 | 26 | 198 | 672 | 30 | 0.64 |

| Age >75 years | 603 | 1786 | 40 | 181 | 510 | 36 | 157 | 608 | 26 | 265 | 668 | 40 | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||||||||||

| Angina | 925 | 1794 | 52 | 217 | 514 | 42 | 340 | 611 | 56 | 368 | 669 | 55 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 472 | 1791 | 26 | 128 | 511 | 25 | 160 | 611 | 26 | 184 | 669 | 28 | 0.68 |

| Heart failure | 163 | 1797 | 9.1 | 31 | 510 | 6.1 | 46 | 609 | 7.6 | 86 | 668 | 13 | 0.35 |

| PCI | 229 | 1790 | 13 | 81 | 512 | 16 | 70 | 609 | 12 | 78 | 669 | 12 | 0.04 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 234 | 1785 | 13 | 59 | 509 | 12 | 77 | 607 | 13 | 98 | 669 | 15 | 0.65 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 100 | 1781 | 5.6 | 30 | 507 | 5.9 | 22 | 610 | 3.6 | 48 | 664 | 7.2 | 0.09 |

| TIA/stroke | 158 | 1782 | 8.9 | 37 | 508 | 7.3 | 56 | 610 | 9.2 | 65 | 664 | 9.8 | 0.28 |

| Renal insufficiency | 168 | 1793 | 9.4 | 44 | 512 | 8.6 | 48 | 610 | 7.9 | 76 | 671 | 11 | 0.66 |

| Recent† major surgery/ trauma | 108 | 1793 | 6.0 | 52 | 512 | 10 | 29 | 610 | 4.8 | 27 | 671 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Risk factors/medications | |||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 1215 | 1789 | 68 | 321 | 507 | 63 | 430 | 612 | 70 | 464 | 670 | 69 | 0.02 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 916 | 1790 | 51 | 233 | 508 | 46 | 351 | 609 | 58 | 332 | 673 | 49 | <0.001 |

| Smoking (current/former) | 1022 | 1793 | 57 | 271 | 512 | 53 | 370 | 612 | 61 | 381 | 669 | 57 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 524 | 1793 | 29 | 140 | 512 | 27 | 169 | 610 | 28 | 215 | 671 | 32 | 0.95 |

| Aspirin | 718 | 1799 | 40 | 177 | 514 | 34 | 266 | 612 | 44 | 275 | 673 | 41 | 0.002 |

| Warfarin | 78 | 1764 | 4.4 | 18 | 500 | 3.6 | 30 | 599 | 5.0 | 30 | 665 | 4.5 | 0.30 |

| Thienopyridine | 125 | 1771 | 7.1 | 39 | 500 | 7.8 | 31 | 604 | 5.1 | 55 | 667 | 8.2 | 0.08 |

| ACE inhibitor | 524 | 1786 | 29 | 123 | 510 | 24 | 169 | 607 | 28 | 232 | 669 | 35 | 0.17 |

| Statin | 506 | 1784 | 28 | 118 | 508 | 23 | 183 | 607 | 30 | 205 | 669 | 31 | 0.01 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||||||||

| New STE/LBBB | 627 | 1799 | 35 | 293 | 514 | 57 | 139 | 612 | 23 | 195 | 673 | 29 | <0.001 |

| ST depression | 771 | 1799 | 43 | 229 | 514 | 45 | 223 | 612 | 36 | 319 | 673 | 47 | 0.01 |

| T-wave inversion | 486 | 1799 | 27 | 117 | 514 | 23 | 177 | 612 | 29 | 192 | 673 | 29 | 0.02 |

| Q wave | 341 | 1799 | 19 | 119 | 514 | 23 | 110 | 612 | 18 | 112 | 673 | 17 | 0.04 |

| LVEF <40% | 311 | 1113 | 28 | 95 | 336 | 28 | 110 | 420 | 26 | 106 | 357 | 30 | 0.56 |

| Killip class | |||||||||||||

| I | 1344 | 1748 | 77 | 379 | 497 | 76 | 471 | 594 | 79 | 494 | 657 | 75 | 0.08 |

| II | 270 | 1748 | 16 | 72 | 497 | 15 | 89 | 594 | 15 | 109 | 657 | 17 | |

| III | 103 | 1748 | 5.9 | 32 | 497 | 6.4 | 28 | 594 | 4.7 | 43 | 657 | 6.5 | |

| IV | 31 | 1748 | 1.8 | 14 | 497 | 2.8 | 6 | 594 | 1.0 | 11 | 657 | 1.7 | |

| Cardiac arrest and/or cardiogenic shock | 59 | 1735 | 3.4 | 25 | 491 | 5.1 | 10 | 589 | 1.7 | 24 | 655 | 3.7 | 0.003 |

| Left main alone (vs. left main with other territory) | 111 | 1799 | 5.6 | 41 | 514 | 8.0 | 32 | 612 | 5.2 | 38 | 673 | 5.6 | 0.07 |

*PCI vs. CABG.

†Within previous 2 weeks.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

The baseline characteristics of patients differed significantly between the three strategies. The most severe patient characteristics were found in the group who did not undergo revascularization. The most severe presentation of the index ACS was found in the PCI group. Compared with the other two groups, patients undergoing PCI presented more frequently with an acute myocardial infarction (as opposed to unstable angina), after a cardiac arrest, or in cardiogenic shock, more frequently had a low ejection fraction (median 46%, inter-quartile range 35–57 vs. 50%, 35–60 in the other two groups, P < 0.05) or a recent history of major surgery or trauma (Table 1). They were also older (median of 71, IQR [60–79]) than patients undergoing CABG (median of 69, IQR [60–75]), but younger than those that did not undergo revascularization during the index hospitalization (median of 72, IQR [61–79]). The median GRACE risk score17 was 151 (equivalent to a 4% risk of in-hospital death) in PCI patients, 134 (≅2.4%) in CABG patients, and 143 (≅3.2%) in non-revascularized patients (P < 0.001 for linear trend).

Time to revascularization varied greatly between the PCI and CABG groups: in the PCI group, 48% of patients underwent revascularization on the day of admission vs. 5.1% in the CABG group. At 48 h, 69% of the PCI patients vs. 25% of the CABG patients were revascularized, the median delay to revascularization being 4.5 days for CABG. In revascularized patients, on average one or two stents were used in 79% (n = 376) of PCI patients, with the majority (n = 121, 70%) being bare-metal stents, whereas one to three grafts were placed in 88% (n = 510) of the CABG patients, with the majority (n = 426, 73%) receiving both venous and arterial grafts (Table 2). In PCI patients, there was a steady increase in the use of drug eluting stents over time, reaching 49% of stents implanted in 2007 (P < 0.001 for linear trend).

Table 2.

Hospital management

| Total population |

PCI |

CABG |

Neither |

P* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | ||

| Medication | |||||||||||||

| Aspirin | 1697 | 1799 | 94 | 486 | 514 | 95 | 577 | 612 | 94 | 634 | 673 | 94 | 0.90 |

| Warfarin | 124 | 1764 | 7.0 | 20 | 500 | 4.0 | 63 | 599 | 11 | 41 | 665 | 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Thienopyridine | 1040 | 1787 | 58 | 446 | 511 | 87 | 248 | 609 | 41 | 346 | 667 | 52 | <0.001 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 1011 | 1781 | 57 | 292 | 509 | 57 | 432 | 606 | 71 | 287 | 666 | 43 | <0.001 |

| LMWH | 1100 | 1787 | 62 | 299 | 508 | 59 | 342 | 609 | 56 | 459 | 670 | 69 | 0.40 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 545 | 1778 | 31 | 286 | 509 | 56 | 150 | 601 | 25 | 109 | 668 | 16 | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1259 | 1786 | 71 | 373 | 510 | 73 | 433 | 607 | 71 | 453 | 669 | 68 | 0.55 |

| Beta-blocker | 1537 | 1789 | 86 | 423 | 511 | 83 | 550 | 606 | 91 | 564 | 672 | 84 | <0.001 |

| Calcium antagonist | 447 | 1779 | 25 | 85 | 507 | 17 | 184 | 608 | 30 | 178 | 664 | 27 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic | 941 | 1784 | 53 | 201 | 507 | 40 | 454 | 610 | 74 | 286 | 667 | 43 | <0.001 |

| IV inotropic drugs | 416 | 1771 | 24 | 105 | 505 | 21 | 254 | 600 | 42 | 57 | 666 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Statin | 1329 | 1784 | 75 | 391 | 508 | 77 | 439 | 607 | 72 | 499 | 669 | 75 | 0.08 |

| Revascularization | |||||||||||||

| Stents per patient | |||||||||||||

| 0 | – | – | – | 30 | 482 | 6.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | n/a |

| 1 | – | – | – | 246 | 482 | 51 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 2 | – | – | – | 136 | 482 | 28 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| ≥3 | – | – | – | 70 | 482 | 15 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Drug-eluting stent | – | – | – | 121 | 409 | 30 | – | – | – | – | – | – | n/a |

| Grafts per patient | |||||||||||||

| 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 578 | 2.4 | – | – | – | n/a |

| 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 117 | 578 | 20 | – | – | – | |

| 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 255 | 578 | 44 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 138 | 578 | 24 | – | – | – | |

| ≥4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 54 | 578 | 9.3 | – | – | – | |

| Type of graft | |||||||||||||

| Venous | – | – | – | – | – | – | 97 | 582 | 17 | – | – | – | n/a |

| Arterial | – | – | – | – | – | – | 59 | 582 | 10 | – | – | – | |

| Both | – | – | – | – | – | – | 426 | 582 | 73 | – | – | – | |

| IABP | 271 | 1752 | 16 | 99 | 501 | 20 | 143 | 593 | 24 | 29 | 658 | 4.4 | 0.009 |

*PCI vs. CABG.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; GP, glycoprotein; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; IV, intravenous; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; n/a, not applicable.

Trends in left main revascularization over 8 years

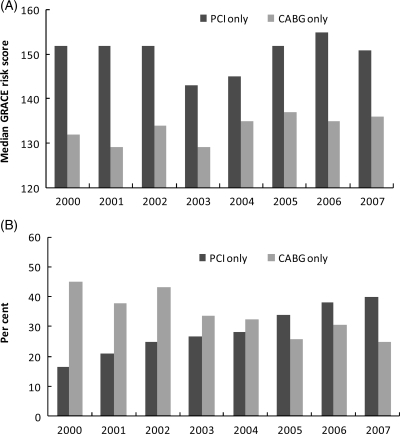

The median GRACE risk score remained constant over the 8-year study period, with a stable 20-point difference between PCI and CABG groups from 2000 to 2007 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Temporal trends in acute coronary syndrome (A) score severity and (B) type of revascularization in left main disease.

In 2000, the rate of CABG was 2.5-fold higher than the rate of PCI. There was a steady shift to more PCIs over time despite the same difference in risk score between CABG and PCI over this period (Figure 2B). In 2007, the PCI rate was 40% while the CABG rate was 25%. The proportion of patients who did not undergo revascularization remained stable over the study period (39% in 2000; 35% in 2007).

Clinical outcomes

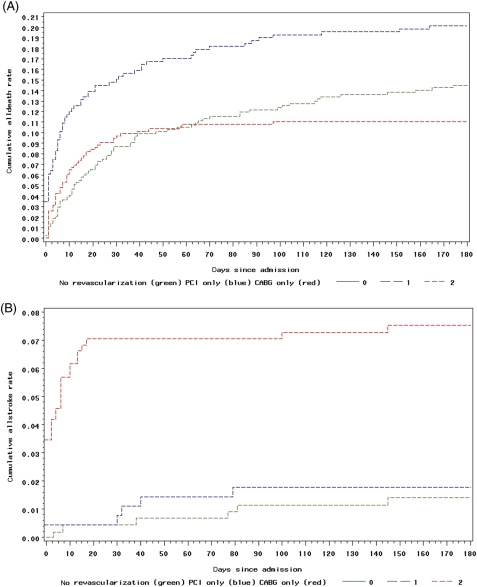

Hospital mortality was 7.7% (n = 139) in the whole population, 11% (n = 69) in those with new ST elevation or left bundle branch block on the index ECG, and 34% (n = 20) in patients who presented with cardiogenic shock and/or after a cardiac arrest (Table 3). The cumulative mortality rate from hospitalization to 6 months post-discharge in the ACS cohort with left main disease was 14%. As expected based on composite GRACE risk scores and percutaneous revascularization of the most acute cases, both in-hospital and 6-month mortality rates were higher in the PCI group (Table 3). The lowest mortality both in hospital and after discharge was in patients who had initially undergone a surgical revascularization strategy (Figure 3A). After discharge, patients who did not undergo hospital revascularization had the highest mortality rate at 6 months (n = 46, 10% vs. n = 17, 5.4% in the PCI group and n = 7, 1.6% in the CABG group) (Table 3). The initially non-revascularized patients had a 43% (n = 179) rate of surgical revascularization during the 6-month follow-up period. Ninety-two per cent of the 43% revascularized after discharge were scheduled for post-discharge revascularization in the hospital.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes

| Total population |

PCI |

CABG |

Neither |

P* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | n | N | % | ||

| Hospital outcome | |||||||||||||

| Death | 139 | 1797 | 7.7 | 55 | 514 | 11 | 33 | 611 | 5.4 | 51 | 672 | 7.6 | 0.001 |

| Death (patients with cardiac arrest and/or cardiogenic shock at presentation) | 20 | 59 | 34 | 10 | 25 | 40 | 3 | 10 | 30 | 7 | 24 | 29 | 0.71 |

| Death (patients with new STE/LBBB on index ECG) | 69 | 627 | 11 | 38 | 293 | 13 | 7 | 139 | 5.0 | 24 | 195 | 12 | 0.01 |

| Cardiac arrest/VF | 148 | 1780 | 8.3 | 65 | 509 | 13 | 31 | 604 | 5.1 | 52 | 667 | 7.8 | <0.001 |

| Sustained VT | 80 | 1788 | 4.5 | 34 | 510 | 6.7 | 16 | 609 | 2.6 | 30 | 669 | 4.5 | 0.001 |

| New episode of HF or pulmonary edema | 389 | 1794 | 22 | 115 | 513 | 22 | 153 | 612 | 25 | 121 | 669 | 18 | 0.33 |

| New cardiogenic shock | 162 | 1796 | 9.0 | 70 | 513 | 14 | 45 | 611 | 7.4 | 47 | 672 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Recurrent angina | 503 | 1796 | 28 | 120 | 514 | 23 | 177 | 611 | 29 | 206 | 671 | 31 | 0.04 |

| Re-infarction | 46 | 1267 | 3.6 | 16 | 408 | 3.9 | 13 | 394 | 3.3 | 17 | 465 | 3.7 | 0.71 |

| Renal failure | 138 | 1781 | 7.8 | 39 | 509 | 7.7 | 59 | 608 | 9.7 | 40 | 664 | 6.0 | 0.24 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 261 | 1793 | 15 | 55 | 511 | 11 | 155 | 612 | 25 | 51 | 670 | 7.6 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 19 | 1789 | 1.1 | 2 | 511 | 0.4 | 13 | 609 | 2.1 | 4 | 669 | 0.6 | 0.02 |

| Death/re(MI)/stroke | 133 | 1265 | 11 | 51 | 406 | 13 | 37 | 395 | 9.4 | 45 | 464 | 14 | 0.26 |

| Non-CABG major bleeding, plus haemorrhagic stroke | 53 | 1772 | 3.0 | 30 | 505 | 5.9 | 7 | 603 | 1.2† | 16 | 664 | 2.4 | n/a |

| Non-CABG major bleeding w/o haemorrhagic stroke | 74 | 1774 | 4.2 | 31 | 506 | 6.1 | 27 | 608 | 4.5 | 16 | 665 | 2.4 | 0.23 |

| Six-month outcomes (follow-up rate if survived to discharge) | 1206 | 1658 | 73 | 312 | 459 | 68 | 437 | 578 | 76 | 457 | 621 | 74 | 0.01 |

| Death | 70 | 1206 | 5.8 | 17 | 312 | 5.4 | 7 | 437 | 1.6 | 46 | 457 | 10 | 0.005 |

| Death (patients with new STE/LBBB on index ECG) | 33 | 404 | 8.2 | 14 | 178 | 7.9 | 3 | 97 | 3.1 | 16 | 129 | 12 | 0.19 |

| Myocardial infarction | 29 | 1136 | 2.6 | 14 | 293 | 4.8 | 3 | 417 | 0.7 | 12 | 426 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 15 | 1143 | 1.3 | 3 | 295 | 1.0 | 5 | 421 | 1.2 | 7 | 427 | 1.6 | 0.99 |

| Re-hospitalization for CV reason | 199 | 1166 | 17 | 68 | 299 | 23 | 45 | 426 | 11 | 86 | 441 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac catheterization | 121 | 1128 | 11 | 66 | 295 | 22 | 20 | 414 | 4.8 | 35 | 419 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| PCI | 65 | 1104 | 5.9 | 32 | 287 | 11 | 15 | 404 | 3.7 | 18 | 413 | 4.4 | <0.001 |

| CABG | 243 | 1116 | 22 | 34 | 292 | 12 | 30 | 405 | 7.4 | 179 | 419 | 43 | 0.06 |

*PCI vs. CABG.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CV, cardiovascular; ECG, electrocardiogram; LBBB, left bundle branch block; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STE, ST elevation; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 3.

(A) Cumulative death rate by revascularization group as a time-varying covariate. The number of patients analysed in each group were as follows: n = 513 for percutaneous coronary intervention, n = 607 for coronary artery bypass graft, and n = 670 for neither. (B) Cumulative rate of stroke by revascularization group as a time-varying covariate. The number of patients analysed in each group were as follows: n = 492 for PCI, n = 581 for CABG, and n = 633 for neither.

The two most frequent in-hospital complications in our ACS population with left main disease were episodes of recurrent ischaemia (n = 503, 28%) and heart failure (n = 389, 22%), which often may have prompted revascularization. Nine per cent (n = 162) of patients developed cardiogenic shock during hospitalization and significantly more of these had PCI (n = 70, 14%) than CABG (n = 45, 7.4%; Table 3). CABG revascularization was associated with a five-fold increase in stroke in comparison with the other two groups (Table 3, Figure 3B). There was no between-group difference for stroke after discharge up to 6 months (Table 3). Finally, there was no difference between groups for the triple ischaemic endpoint of death, re-infarction, or stroke (Table 3).

Cox regression model for death

The covariates (HR, 95% confidence interval (CI)) were cardiac arrest at presentation (0.74, 0.29–1.86), Killip class I–IV (1.27, 1.06–1.53), ST elevation (1.45, 1.01–2.06), ST depression (1.80, 1.30–2.49), Creatinine, per 1 mg (1.19, 1.09–1.32), positive initial enzymes (1.15, 0.81–1.64), age per 10 years (1.63, 1.39–1.91), pulse per 30 b.p.m. (1.20, 0.98–1.48), systolic BP per 20 mm hg decrease (1.20, 1.08–1.33), Q wave (1.12, 0.77–1.63), mechanical ventilator (3.04, 2.10–4.39). After adjustment for these covariates and considering PCI and CABG as time-varying covariates, revascularization was associated with an early hazard of hospital death compared with no revascularization that was significant for PCI (HR 2.60, 95% CI 1.62–4.18) but not for CABG (HR 1.26, 95% CI 0.72–2.22). From discharge to 6 months, both PCI (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.23–0.85) and CABG (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.04–0.28) were significantly associated with improved survival in comparison with an initial strategy of no revascularization.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study presents one of the largest data sets of ULMCD and certainly the largest experience in ACS. The incidence of ULMCD in patients with an ACS is not known precisely and we report here an incidence of 4% (1799 of 43 018), which may be an underestimate as many patients may have died early before enrolment and, cardiac catheterization was performed in only 62% of the patients enrolled in the registry. An important finding from this 8-year study is that PCI has become the preferred mode of revascularization for ULMCD and is used in the highest risk patients, but is associated with frequent repeat revascularizations in the following 6 months. In contrast, surgery is performed in lower risk patients and is associated with better survival but with more frequent acute strokes. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, both types of revascularization improved 6-month survival in comparison with an initial conservative medical strategy.

Although still debated, the use of percutaneous revascularization in ULMCD has increased in frequency, with improvements and standardization of techniques, including T-stenting, high pressure inflation, optimization of stenting with intravascular ultrasounds, the kissing-balloon technique, and restenosis reduction with drug-eluting stents. Our study confirms this impression in unselected patients presenting with an ACS, recruited in more than 100 multinational centres, and in whom PCI was the preferred revascularization strategy in the last 3 years of the study. There may be an early hazard for this approach in ACS patients, with an in-hospital mortality rate two- to four-fold higher than the rates usually reported for scheduled percutaneous revascularization of ULMCD.10,14,19,20 This is explained largely by the patients’ high-risk characteristics, due to the absence of exclusion criteria in GRACE, and, when ACS is complicated by cardiogenic shock and/or resuscitated cardiac arrest, in-hospital mortality reached 40% in the PCI group. Whether CABG would be a better option in shock patients is still discussed.21

Despite the trend over time to more frequent percutaneous revascularization, the group who underwent CABG was as large as the PCI and non-revascularization groups, and had the lowest non-adjusted mortality rate at hospital discharge and at 6 months. The GRACE risk score, which evaluates risk of in-hospital mortality in ACS patients,17 was significantly lower in CABG patients than in PCI patients, reflecting the selection of patients for CABG surgery. A similar observation was reported with the EuroScore and Parsonnet revascularization scores, which were lower for CABG than for PCI in the recent SYNTAX registry of patients who were not candidates for randomization in the SYNTAX study.14

In the present study, in-hospital death and cardiac arrest were less frequent in the CABG group, as was death, myocardial infarction, and revascularization from hospital discharge to 6 months. After adjustment, CABG revascularization was strongly and significantly associated with survival from discharge to 6 months in comparison with the group who did not undergo revascularization. Percutaneous coronary intervention was also significantly and positively associated with survival over the same period, although with a lower magnitude.

Whether or not the difference in survival between the two modes of revascularization is due to the treatment strategies themselves or to differences in the patient populations undergoing such treatment is not possible to determine in this observational study. Although we attempted to adjust for all confounding variables measured, other important clinical or angiographic parameters that influence clinical outcome may have been overlooked or not even collected and we could not adjust for the selection of patients into the treatment groups. Moreover, considering PCI and CABG as time-varying covariates is a statistical approach that carries its own limitations. Half of the patients in the PCI group underwent revascularization on the day of admission, accumulating all the risks of the ACS event and of the revascularization procedure in the first 24 h, while the median time to revascularization was 4.5 days in the CABG group, selecting out patients who died from the event or developed a contraindication to surgery during the waiting period. Finally, CABG patients had a significant excess of stroke in comparison with the other two groups, a complication of CABG also identified in the SYNTAX study. Whether the procedure of revascularization itself or other factors such as single vs. double antiplatelet therapy is involved in this excess risk of stroke cannot be determined from our study. Altogether, the triple ischaemic endpoint (death, re-infarction, or stroke) did not differ significantly between groups during the hospital phase.

Evidence-based practice guidelines recommend rapid access to angiography and revascularization in both high-risk non-ST elevation and ST elevation ACS.22–25 Patients with ULMCD are among the highest risk patients presenting with an ACS but current consensus guidelines do not address the optimal timing and mode of revascularization for these individuals. The adjusted 6-month survival benefit observed with revascularization in our study suggests that these recommendations may well apply to ACS with ULMCD. Percutaneous coronary intervention of ULMCD is frequently performed in ACS patients and recent reports suggest a larger clinical benefit with drug-eluting stents than with bare-metal stents.26 Interestingly also, of the patients who did not undergo any type of revascularization during the index hospitalization, 43% underwent CABG revascularization during the 6-month period following discharge. This suggests that the initial very high risk of these patients should not preclude re-evaluation for potential revascularization at some point before hospital discharge.

Conclusions

Unprotected left main coronary disease in patients presenting with an ACS is a rare but serious situation, with high in-hospital mortality, especially in those presenting with STEMI and/or haemodynamic or arrhythmic instability. Percutaneous coronary intervention has become the most common strategy of revascularization in ACS patients with ULMCD and is generally preferred in patients with multiple comorbidities and/or in very unstable patients. In contrast, CABG surgery, when possible, is often delayed by a few days and is associated with good 6-month survival. Therefore the two modes of revascularization appear complementary in this high-risk group.

Funding

GRACE is funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France) to the Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA).

Conflict of interest: G.M.: research grant: Sanofi-Aventis, BMS, Eli Lilly; Consulting/speaker fees: Sanofi-Aventis, BMS, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, Schering Plough, TMC, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer. D.B.: National Heart Foundation of Australia, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Schering Plough. K.A.E.: research grant: Biosite, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, Hewlett Foundation, Mardigian Fund, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Varbedian Fund; Consultant/Advisory Board: NIH NHLBI, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. F.A.A.: research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Scios, and The Medicines Company and serves as a Consultant/Advisory Board member for Sanofi-Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Scios, and The Medicines Company. G.F.: none. M.S.L.: Speakers bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, Schering Plough. P.G.S.: research grant: Sanofi-Aventis (significant); Speakers bureau (modest): Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, GSK, Medtronic, Nycomed, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, The Medicines Company; Consulting/advisory board (modest): Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, Endotis, GSK, Medtronic, MSD, Nycomed, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, The Medicines Company. Stockholding: none. Á.A.: Sanofi-Aventis, Population Health Research Institute, Boehringer-Ingelheim. S.G.G.: research grant support and/or speaker/consulting honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Glaxo Smith Kline, Guidant, Hoffman La-Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Key Schering/Schering Plough, Merck Frosst, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company. Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hoffman La-Roche, Key Schering/Schering Plough, Merck Frosst, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company. Consultant/Advisory Board: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hoffman La-Roche, Sanofi-Aventis. J.M.G.: none.

Acknowledgements

We thank and express our gratitude to the physicians and nurses participating in GRACE. Sophie Rushton-Smith, PhD, provided editorial support for the manuscript and was funded by Sanofi-Aventis through the GRACE registry.

References

- 1.Varnauskas E. Twelve-year follow-up of survival in the randomized European Coronary Surgery Study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:332–337. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808113190603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaitman BR, Fisher LD, Bourassa MG, Davis K, Rogers WJ, Maynard C, Tyras DH, Berger RL, Judkins MP, Ringqvist I, Mock MB, Killip T. Effect of coronary bypass surgery on survival patterns in subsets of patients with left main coronary artery disease. Report of the Collaborative Study in Coronary Artery Surgery (CASS) Am J Cardiol. 1981;48:765–777. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SJ, Park SW, Hong MK, Cheong SS, Lee CW, Kim JJ, Hong MK, Mintz GS, Leon MB. Stenting of unprotected left main coronary artery stenoses: immediate and late outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black A, Cortina R, Bossi I, Choussat R, Fajadet J, Marco J. Unprotected left main coronary artery stenting: correlates of mid-term survival and impact of patient selection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:832–838. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvestri M, Barragan P, Sainsous J, Bayet G, Simeoni JB, Roquebert PO, Macaluso G, Bouvier JL, Comet B. Unprotected left main coronary artery stenting: immediate and medium-term outcomes of 140 elective procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chieffo A, Morici N, Maisano F, Bonizzoni E, Cosgrave J, Montorfano M, Airoldi F, Carlino M, Michev I, Melzi G, Sangiorgi G, Alfieri O, Colombo A. Percutaneous treatment with drug-eluting stent implantation versus bypass surgery for unprotected left main stenosis: a single-center experience. Circulation. 2006;113:2542–2547. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SW, Park SW, Hong MK, Kim YH, Lee BK, Song JM, Han KH, Lee CW, Kang DH, Song JK, Kim JJ, Park SJ. Triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: impact on stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1833–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erglis A, Narbute I, Kumsars I, Jegere S, Mintale I, Zakke I, Strazdins U, Saltups A. A randomized comparison of paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents for treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MS, Kapoor N, Jamal F, Czer L, Aragon J, Forrester J, Kar S, Dohad S, Kass R, Eigler N, Trento A, Shah PK, Makkar RR. Comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery with percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Moretti C, Meliga E, Agostoni P, Valgimigli M, Migliorini A, Antoniucci D, Carrié D, Sangiorgi G, Chieffo A, Colombo A, Price MJ, Teirstein PS, Christiansen EH, Abbate A, Testa L, Gunn JP, Burzotta F, Laudito A, Trevi GP, Sheiban I. A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis on 1278 patients undergoing percutaneous drug-eluting stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seung KB, Park DW, Kim YH, Lee SW, Lee CW, Hong MK, Park SW, Yun SC, Gwon HC, Jeong MH, Jang Y, Kim HS, Kim PJ, Seong IW, Park HS, Ahn T, Chae IH, Tahk SJ, Chung WS, Park SJ. Stents versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1781–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brener SJ, Galla JM, Bryant R, 3rd, Sabik JF, 3rd, Ellis SG. Comparison of percutaneous versus surgical revascularization of severe unprotected left main coronary stenosis in matched patients. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buszman PE, Kiesz SR, Bochenek A, Peszek-Przybyla E, Szkrobka I, Debinski M, Bialkowska B, Dudek D, Gruszka A, Zurakowski A, Milewski K, Wilczynski M, Rzeszutko L, Buszman P, Szymszal J, Martin JL, Tendera M. Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Ståhle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ, Van Dyck N, Leadley K, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW SYNTAX Investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The GRACE Investigators. Rationale and design of the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) Project: a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2001;141:190–199. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.112404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steg PG, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Fox KA, Eagle KA, Flather MD, Sadiq I, Kasper R, Rushton-Mellor SK, Anderson FA GRACE Investigators. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Cannon CP, Van De Werf F, Avezum A, Goodman SG, Flather MD, Fox KA Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Investigators. Predictors of hospital mortality in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2008. pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemin RJ. Coronary artery bypass grafting versus stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: where lies the body of proof? Circulation. 2008;118:2326–2329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.820324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodés-Cabau J, Deblois J, Bertrand OF, Mohammadi S, Courtis J, Larose E, Dagenais F, Déry JP, Mathieu P, Rousseau M, Barbeau G, Baillot R, Gleeton O, Perron J, Nguyen CM, Roy L, Doyle D, De Larochellière R, Bogaty P, Voisine P. Nonrandomized comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in octogenarians. Circulation. 2008;118:2374–2381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MS, Tseng CH, Barker CM, Menon V, Steckman D, Shemin R, Hochman JS. Outcome after surgery and percutaneous intervention for cardiogenic shock and left main disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Silber S, Aguirre FV, Al-Attar N, Alegria E, Andreotti F, Benzer W, Breithardt O, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Dudek D, Gulba D, Halvorsen S, Kaufmann P, Kornowski R, Lip GY, Rutten F ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertrand ME, Simoons ML, Fox KA, Wallentin LC, Hamm CW, McFadden E, De Feyter PJ, Specchia G, Ruzyllo W. Task Force on the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1809–1840. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2002.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC, Jr, Anbe DT, Kushner FG, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW Canadian Cardiovascular Society; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:210–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, 2nd, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction); American College of Emergency Physicians; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association of Cardiovascular, Pulmonary Rehabilitation; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116:e148–e304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamburino C, Di Salvo ME, Capodanno D, Palmerini T, Sheiban I, Margheri M, Vecchi G, Sangiorgi G, Piovaccari G, Bartorelli A, Briguori C, Ardissino D, Di Pede F, Ramondo A, Inglese L, Petronio AS, Bolognese L, Benassi A, Palmieri C, Filippone V, De Servi S. Comparison of drug-eluting stents and bare-metal stents for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]