Abstract

Objective

Interaction of macrophages with aggregated matrix-anchored lipoprotein deposits is an important initial step in atherogenesis. Aggregated lipoproteins require different cellular uptake processes than those used for endocytosis of monomeric lipoproteins. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that engagement of aggregated LDL (agLDL) by macrophages could lead to local increases in free cholesterol levels and that these increases in free cholesterol regulate signals that control cellular actin.

Methods and Results

AgLDL resides for prolonged periods in surface-connected compartments. While agLDL is still extracellular, we demonstrate that an increase in free cholesterol occurs at sites of contact between agLDL and cells due to hydrolysis of agLDL-derived cholesteryl ester. This increase in free cholesterol causes enhanced actin polymerization around the agLDL. Inhibition of cholesteryl ester hydrolysis results in decreased actin polymerization.

Conclusions

We describe a novel process that occurs during agLDL-macrophage interactions in which local release of free cholesterol causes local actin polymerization, promoting a pathologic positive feedback loop for increased catabolism of agLDL and eventual foam cell formation.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, foam cells, surface-connected compartment, Rho GTPases, F-actin

Introduction

A key step in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions is formation of lipid-loaded macrophage foam cells1. Soluble lipoproteins accumulate at sites of atherosclerotic plaque formation where they undergo modification, aggregation and anchoring to the extracellular matrix2–4. Monocytes migrate from the blood, differentiate into macrophages that degrade LDL, and become filled with re-esterified cholesterol droplets5, 6. These cholesteryl ester (CE)-filled foam cells acquire new biological properties, particularly loss of motility7; secretion of cytokines8, growth factors6 and proteases9; and induction of apoptosis10, 11. These processes contribute to early lesion growth and late complications leading to plaque rupture5, 12.

It has been proposed that aggregated lipoproteins (agLDL) tightly linked to the extracellular matrix play an important role in the development of atherosclerotic lesions4. The interaction of macrophages with retained and aggregated lipoproteins differs significantly from the uptake of monomeric lipoproteins. For example, aggregates and associated extracellular matrix components are too large to be taken up by endocytosis or even by phagocytosis without breaking the aggregates and/or matrix into smaller pieces. The breakdown of the lipoproteins requires the actin cytoskeleton and activation of the Rho-family GTPases Rac1 and/or Cdc4213.

Furthermore, for 1–2 hours after initial contact of a macrophage with a retained and aggregated LDL particle the agLDL remains topologically outside the macrophage even though it may be in deep plasma membrane invaginations14, 15. Interestingly, there is significant hydrolysis of CE while the agLDL remain extracellular, and this hydrolysis requires lysosomal acid lipase (LAL)14. To explain this, it has been suggested that selective CE uptake might deliver the CE to lysosomes, but such a process has not been observed. An alternative mechanism is that hydrolysis of CE in agLDL occurs extracellularly. Various types of macrophages and macrophage-related osteoclasts are able to form extracellular lytic compartments 16–18. Consistent with this, we have observed that macrophages can create extracellular acidic compartments upon contact with agLDL, and that they can secrete lysosomal contents into these contact zones (Haka et al., in preparation).

Herein, we test the hypothesis that macrophage interactions with agLDL lead to extracellular CE hydrolysis and a consequent increase in free cholesterol (FC) which induces local actin polymerization.

Materials and Methods

A complete description of Materials and Methods is supplied in the Supplementary Material, including Supplemental Figures I and II

Lipoproteins

Human LDL was prepared19 and conjugated to AlexaFluor-546 (Alexa546). We also reconstituted LDL with cholesteryl oleate, cholesteryl oleoyl ether, or cholesteryl-[4-14C]-oleate20.

Interaction of agLDL with macrophages and fluorescent labeling of cells

LDL was aggregated by vortexing, and aggregates were centrifuged and resuspended in serum-free DMEM/HEPES. Approximately 50μg/ml of agLDL was added to cells at 37°C.

Fluorescent labeling of cells

F-actin was labeled with Alexa488-phalloidin, free cholesterol (FC) was labeled with filipin, and the plasma membrane was labeled with Alexa488-cholera toxin subunit B (CtB).

Microscopy and image quantification

A Zeiss LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscope and a Leica DMIRB epi-fluorescence microscope were used for fluorescence imaging. Image analysis is described in the Supplemental Materials.

Transfection of siRNA

RNAi oligonucleotides (Dharmacon) were transfected using Lipofectamine for mouse peritoneal macrophages and HiPerFect for RAW 264.7 cells.

LAL reconstitution

Recombinant Pichia-derived Human LAL (phLAL) was added to RAW 264.7 cells as described21.

Hydrolysis of cholesteryl-[4-14C]-oleate-containing LDL

LDL reconstituted with cholesteryl-[4-14C]-oleate was vortex-aggregated and incubated with cells in the presence of an acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) inhibitor followed by treatment with plasmin to release extracellular agLDL22. Lipids were extracted, and radiolabeled FC and CE were measured by thin layer chromatography (TLC).

Results

Extracellular agLDL in surface-connected compartments leads to the formation of F-actin-rich structures

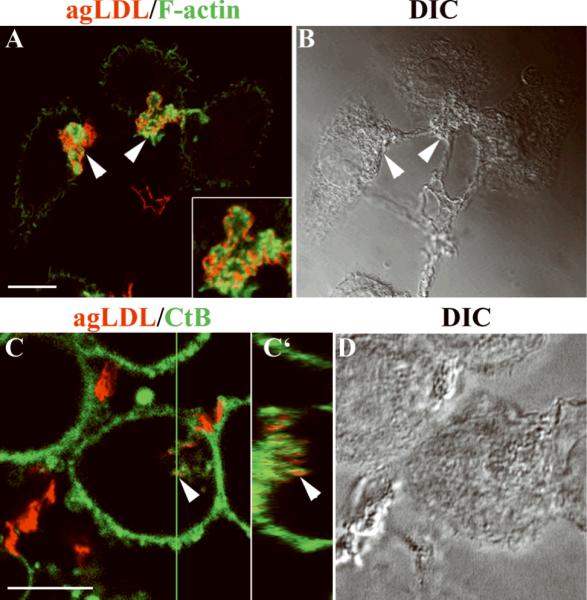

We examined the formation of F-actin in cells near sites of contact with agLDL. J774 cells were incubated with suspensions of Alexa546-agLDL followed by fixation and labeling of F-actin by Alexa488-phalloidin (Fig. 1A,B). After 30 minutes, an enrichment of F-actin was detected near the sites of contact with agLDL (arrowheads, Fig. 1A). An enlarged view (Fig. 1A, inset) shows that F-actin (green) is closely associated with the agLDL (red), indicating that actin polymerization is enhanced in the immediate vicinity of the contact with agLDL. Approximately half of the aggregates touching cells had F-actin enriched structures in their immediate vicinity within 30 minutes, and the fraction of agLDL surrounded by F-actin increased further at later times (not shown). Macrophage-like RAW cells, mouse peritoneal macrophages and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages all exhibit similar responses to agLDL (Supplemental Fig. III). To investigate a more physiological model, J774 cells were plated on top of agLDL bound to a smooth-muscle cell matrix. Similar F-actin structures near contact sites were observed (Supplemental Fig. III). The interaction with agLDL did not induce apoptosis (assessed by annexin V binding) or cell permeabilization (assessed by propidium iodide staining).

Figure 1. F-actin at the areas of contact between agLDL and macrophages.

J774 cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL for 30 minutes. Samples were either fixed and labeled for F-actin with fluorescent phalloidin (A, B) or labeled with fluorescent CtB before fixation (C, D). (A) Merged images showing F-actin (green) and agLDL (red). Arrowheads, agLDL associated with F-actin-rich structures. Inset, an enlarged view of an F-actin structure around agLDL. (B) Transmitted-light DIC image. (C, C') Alexa-488 CtB labeling showed that agLDL-containing compartments are connected to the cell surface. Arrowheads, compartments containing agLDL (red) also label with CtB (green). (D) Transmitted-light DIC image. Images in A, C are single confocal slices. C' is an axial slice through the 17μm thick confocal stack at the position of the green line in C. Axial-step is 0.45μm. Scale bars: 10μm.

Under the conditions used in these experiments, the sites of contact between cells and agLDL were surface-connected membrane invaginations (also called surface-connected compartments or SCCs), similar to those described previously14, 15. Cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL (red, Fig. 1C) at 37°C and then labeled on ice with Alexa488-CtB (green, Fig. 1C) to label the plasma membrane. Since the cells are not fixed or permeabilized, the macromolecular cholera toxin can only label glycolipids on the surface of the cells. Sites of contact with agLDL were labeled by CtB (Fig. 1C, arrowhead), indicating that they are connected to the cell surface. An axial slice through the confocal stack at the position of the green line shows that the part of the aggregate resembling a separate vesicle in the projection image is actually a deep SCC (Fig. 1C', arrowhead). After a 2 hour incubation of J774 cells with agLDL, some SCCs containing agLDL can still be observed, but Alexa546-agLDL can also be seen in organelles that are not connected to the surface (Supplemental Fig. IV). Individual SCCs could persist for more than 30 minutes as confirmed by live-cell observation (Supplemental Fig. V).

FC is enriched at the site of contact between agLDL and macrophages

In a previous study it was shown that there was significant CE hydrolysis while the agLDL particles were still outside the macrophage14. This hydrolysis was not seen upon incubation with macrophages lacking LAL. It was hypothesized that the hydrolysis was a consequence of selective uptake of CE into cells and hydrolysis in lysosomes. To determine whether CE hydrolysis might actually take place in SCCs, we used filipin, a fluorescent sterol-binding polyene that can be used for quantitative measurement of FC23, to detect FC.

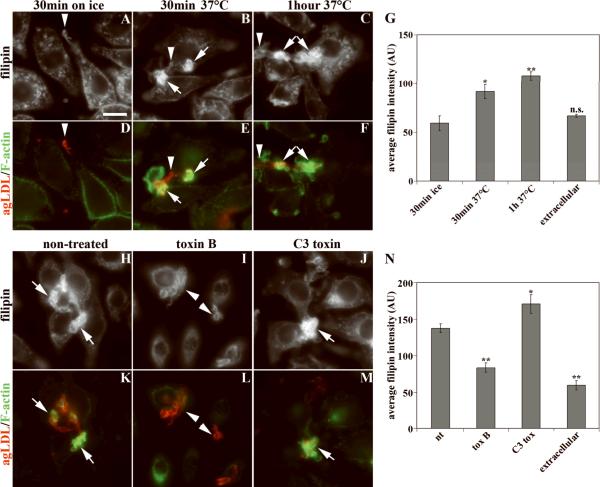

Cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL, fixed, and labeled with filipin and Alexa488-phalloidin (Fig. 2). Cells incubated with agLDL on ice for 30 minutes (Fig. 2A, D) showed weak filipin staining in the region contacting agLDL (arrowheads, Fig. 2A, D), and there was no increased F-actin near the agLDL (Fig. 2D). When cells were incubated with agLDL at 37°C, there was intense filipin staining near the agLDL (arrows, Fig. 2B, C), and these regions were enriched in F-actin (Fig. 2E, F). The bright filipin labeling indicates there is an increase in FC at sites of contact between agLDL and the cell. The agLDL itself contains low amounts of FC as shown by the weaker intensity of filipin labeling of regions of agLDL that are not surrounded by F-actin (arrowheads, Fig. 2A–F).

Figure 2. Generation of FC at contact sites between agLDL and macrophages.

(A–G) J774 cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL (red in D–F) for the indicated time periods either on ice (A, D) or at 37°C (B, C and E, F), fixed, and labeled with filipin (A–C) and Alexa488-phalloidin (green in D–F). Arrows show agLDL surrounded by F-actin-rich structures. Arrowheads show agLDL that is not surrounded by F-actin. (G) Quantification of average filipin intensity associated with agLDL touching cells and with agLDL not interacting with cells (extracellular), the latter reflecting the baseline FC content of agLDL. For statistical tests values were compared to cells incubated on ice. (H–N) J774 cells were either left untreated (H, K) or pretreated with toxin B (I, L) or C3 transferase (J, M), then incubated with Alexa546-agLDL (red in K–M) in the presence of inhibitors, fixed, and labeled with filipin (H–J) and Alexa488-phalloidin (green in K–M). Arrows show agLDL surrounded by F-actin-rich structures. Arrowheads show agLDL that is not surrounded by F-actin. (N) Quantification of average filipin intensity associated with agLDL touching cells and agLDL not interacting with cells. For statistical tests values were compared to non-treated cells. Error bars, SEM for 10 fields containing >100 cells. * p<0.05, ** - p<0.01, n.s. – non-significant difference. All images were taken on a wide-field fluorescence microscope. Scale bar: 10μm.

We quantified the average filipin intensity in pixels that contained agLDL. The filipin intensity for the cells incubated on ice was similar to the filipin intensity in aggregates that did not touch cells. After 30 minutes at 37°C, the filipin labeling in pixels that contained agLDL in contact with cells was significantly higher than for cells incubated on ice, and the filipin intensity remained elevated after a 1 hour incubation (Fig. 2G). These data indicate that at least a portion of the CE hydrolysis occurs while agLDL is outside the cell14. After a 2 hour incubation, increased intracellular filipin labeling is seen, and an increase in staining of lipid droplets by Nile Red is observed (not shown). Using biochemical assays, it was reported that about 10% of CE associated with agLDL enmeshed in extracellular matrix is hydrolyzed by J774 cells within 40 minutes, a time when most of the agLDL is still extracellular14.

Under the conditions of our experiments, the majority of cell-associated cholesterol is FC. We incubated cells with cholesteryl-[4-14C]-oleate reconstituted agLDL. After 90 minutes, extracellular labeled agLDL was removed by plasmin treatment, which has been reported to release agLDL residing in the SCC22. More than 60% of the cell-associated radiolabeled cholesterol was FC (Supplementary Table 1). As discussed below, we have also demonstrated hydrolysis of CE in the agLDL that remains extracellular.

Formation of F-actin structures around agLDL and increase of filipin intensity requires Rac and/or CDC42 activities but not Rho activity

Inhibition of all Rho family GTPases by Clostridium difficile toxin B has been shown to inhibit the degradation of matrix-retained and agLDL by >90%, whereas the selective inhibition of Rho by C3 transferase had no effect13. We evaluated the role of Rho GTPases in forming the F-actin containing structures at sites of contact with agLDL and in the localized increase in FC. Cells pretreated with toxins were incubated with a suspension of Alexa546-agLDL for 30 minutes in the presence of toxins, fixed, and labeled with filipin and Alexa488-phalloidin (Fig. 2H–M). In control cells, filipin intensity increased, and F-actin rich compartments formed at sites of contact between agLDL and cells (Fig. 2H, K arrows). Treatment with toxin B inhibited the increase in filipin labeling (arrowheads, Fig. 2I), and the ability of cells to form an F-actin rich compartment around agLDL was blocked (arrowheads, Fig. 2L). Quantitative analysis showed that the average filipin intensity in pixels containing aggregates in contact with cells was significantly lower in cells treated with toxin B than in untreated cells (Fig. 2N). Treatment with C3 transferase inhibited activation of Rho as confirmed by an effector pull-down assay (not shown), but there was no effect on the increase in filipin intensity or actin polymerization around agLDL (Fig 2 J,M,N). These data indicate that actin polymerization around agLDL and the increase in FC require the activity of Rac and/or Cdc42 but not Rho.

Hydrolysis of CE is required for actin polymerization around agLDL

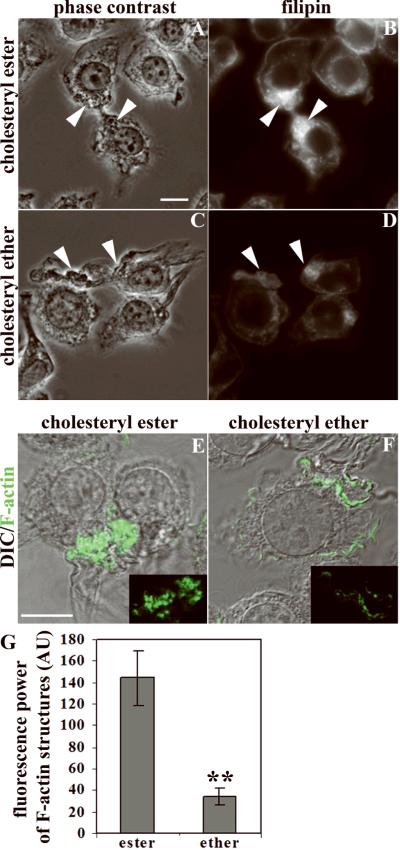

We examined whether a local increase of FC at the sites of contact between cells and agLDL is responsible for the increased actin polymerization observed around agLDL. We incubated J774 cells with agLDL containing a non-hydrolysable analog of CE – cholesteryl-oleyl ether. LDL reconstituted with either cholesteryl-oleyl ester or cholesteryl-oleyl ether was aggregated and incubated with cells for 30 minutes. The cells were fixed and labeled with filipin (Fig. 3A–D). Sites of contact between agLDL and cells were identified in phase-contrast microscopy images. A much greater filipin signal was observed in areas of contact with ester-containing aggregates (arrowheads, Fig. 3A,B) as compared with ether-containing aggregates (arrowheads, Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3. Reduced F-actin surrounding agLDL reconstituted with non-hydrolysable cholesteryl ether.

J774 cells were incubated with agLDL reconstituted with either CE (A, B, E) or cholesteryl ether (C, D, F). After 30 minutes incubation, cells were fixed and labeled with filipin (B, D) or Alexa488-phalloidin (green in E, F). Arrowheads show agLDL-macrophage contact areas. (G) Fluorescence power of Alexa488-phalloidin associated with agLDL in contact with cells was quantified for cholesteryl ether- and CE-containing agLDL. Error bars, SEM for 10 fields with >100 cells. ** p<0.01. Scale bars: 10μm. Images (A–D) were taken on a wide-field fluorescence microscope, (E, F) – single confocal slice superimposed with DIC.

To investigate the role of CE hydrolysis in the increase of F-actin near agLDL, we examined F-actin in cells incubated with either ester- or ether-containing agLDL (Fig. 3E,F). F-actin-rich structures that formed around agLDL reconstituted with CE were prominent (Fig. 3E), and their morphology was similar to that observed in cells interacting with agLDL made from native LDL. Contact with the cholesteryl ether-containing agLDL caused some actin polymerization, but the area of the F-actin structures and the brightness of the phalloidin labeling were much less than for agLDL containing CE (Fig. 3F,G). Quantitative analysis showed that the amount of F-actin around agLDL containing cholesteryl ether is significantly lower than around CE-reconstituted agLDL. These data show that formation of FC due to hydrolysis of CE at sites of contact between cells and agLDL is important for inducing local actin polymerization.

Depletion of FC by treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), a cholesterol chelator, also decreased local actin polymerization during interaction of macrophages with agLDL (Supplemental Fig. VI).

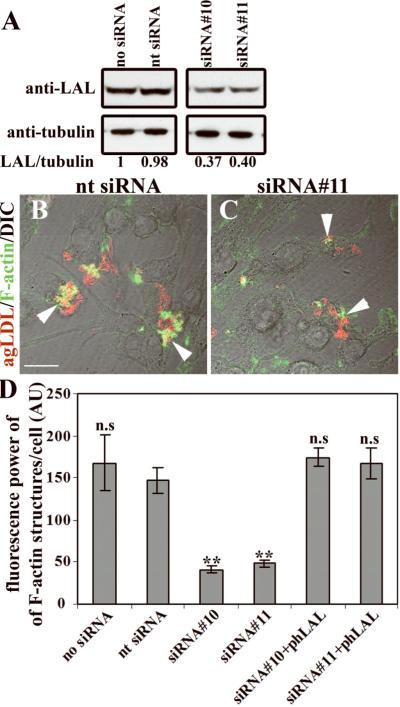

Knock-down of LAL reduces actin polymerization around agLDL

To test whether LAL-mediated CE hydrolysis is required for stimulation of actin polymerization around agLDL, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of LAL expression in RAW cells. The amount of LAL protein in the cells was reduced by more than 50% after treatment with LAL-specific siRNAs, while treatment with non-targeting siRNA did not cause a significant change in LAL expression (Fig. 4A). Samples were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL for 30 minutes, fixed, and labeled for F-actin (Fig. 4B,C). Treatment with non-targeting siRNA did not affect formation of F-actin structures around agLDL, but treatment with LAL-specific siRNA significantly reduced the formation of F-actin structures, as confirmed by quantitative analysis (Fig. 4D). To confirm the specificity of the siRNA-mediated effect, we added back recombinant phLAL (human LAL produced in Pichia pastoris)21 to LAL siRNA-treated cells. This mannosylated phLAL should enter macrophage cells via the mannose receptor and be delivered to lysosomes. Restoration of LAL to cells reversed the effect of siRNAs on the F-actin surrounding agLDL (Fig. 4D), demonstrating that a decrease in LAL specifically caused the decreased F-actin accumulation in siRNA knockdown cells.

Figure 4. siRNA-mediated knock-down of LAL reduces F-actin around agLDL.

(A) LAL protein levels in control and siRNA transfected cells. All lanes are from the same blot but are shown in two panels to remove extraneous lanes. (B, C) Transfected cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL (red) and labeled with Alexa488-phalloidin (green). Arrowheads, agLDL-macrophage contact areas. (D) Fluorescence power of Alexa488-phalloidin around agLDL was quantified for non-transfected cells, cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA, cells transfected with 2 different LAL-specific siRNAs, and cells treated with phLAL after LAL knock-down. For statistical analysis values were compared to non-targeting siRNA-transfected cells. Error bars: SEM for 14 fields containing >150 cells. ** p<0.01, n.s. – not significant. Scale bar: 15μm. Images are single confocal slices superimposed with DIC.

Similar results were obtained upon siRNA-mediated knock-down of LAL in mouse peritoneal macrophages (Supplemental Fig. VII).

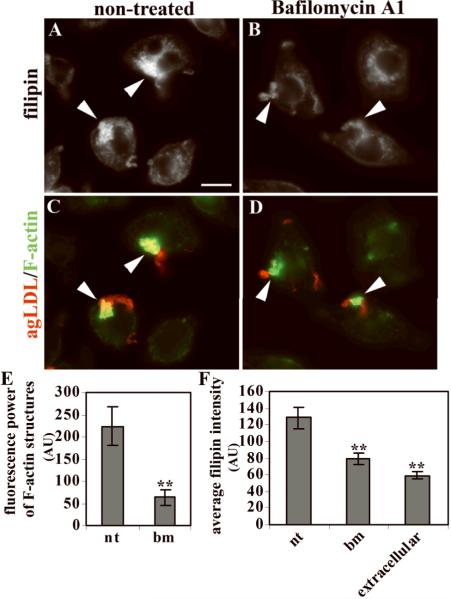

Treatment with Bafilomycin A1 inhibits FC production and formation of F-actin at sites of contact between cells and agLDL

Proper functioning of LAL requires an acidic pH. AgLDL-containing SCCs could be acidified by H+-pumping vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase), which resides in the plasma membrane and in internal organelles24. To test whether acidification of the agLDL-containing compartment is needed for extracellular CE hydrolysis and actin polymerization around agLDL, we treated cells with bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of the V-ATPase. J774 cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL in the absence or presence of bafilomycin A1 (1μM) for 30 minutes, fixed, and labeled with filipin and Alexa488-phalloidin. Little increase of filipin labeling was observed near aggregates touching bafilomycin A1-treated cells in comparison with non-treated cells (arrowheads, Fig. 5A,B), and the size of F-actin structures around agLDL was smaller in bafilomycin A1-treated cells (Fig. 5C,D). Quantification confirmed these results (Fig. 5E). Consistent with this, bafilomycin A1 reduced the amount of radiolabeled FC delivered to cells due to labeled CE hydrolysis by 90% in a biochemical assay (Supp. Table 1). (It should be noted that bafilomycin A1 treatment increases the lysosomal pH in J774 cells under these conditions – data not shown.) We have also measured the generation of FC from radiolabeled CE in extracellular aggregates by vigorously rinsing to remove agLDL from SCCs (A. Haka et al., in preparation). In that study, 3–4% of radiolabeled CE in agLDL was converted into radiolabeled FC extracellularly, and bafilomycin A1 inhibited the production of radiolabeled FC. Taken together, these data show the requirement for acidification by V-ATPase for hydrolysis of CE and induction of actin polymerization around agLDL.

Figure 5. Treatment with bafilomycin A1 reduces FC production and decreases F-actin at agLDL contact sites.

J774 cells were incubated with Alexa546-agLDL (red in C, D) in the presence (B, D) or absence (A, C) of bafilomycin A1, fixed, and labeled with filipin (A, B) and Alexa488-phalloidin (green in C, D). (E) Quantification of the fluorescence power of F-actin around agLDL; nt – not treated, bm – bafilomycin A1 treated. (F) Quantification of the average filipin intensity in parts of agLDL touching cells. For statistics values were compared to non-treated cells. Error bars: SEM for 10 fields containing >100 cells. ** p<0.01. Scale bar: 10μm. Images were taken on a wide-field fluorescence microscope.

Discussion

In previous studies we found that increasing macrophage plasma membrane cholesterol levels globally (by incubation of cells with cholesterol chelated to a carrier, MβCD) led to alterations in macrophage signaling and F-actin organization23, 25. Based on these observations, we speculated that contact of macrophages with agLDL in the vessel wall could lead to similar alteration in cellular F-actin organization as a consequence of FC transfer. In this study, we show directly that interactions of agLDL with macrophages lead to local increases in FC and that these localized increases in FC influence (and are influenced by) local changes in F-actin organization.

Although the uptake and degradation of agLDL was shown to be actin-dependent13, the spatial relationship of F-actin and lipoprotein aggregates was not explored. We have shown that global changes in F-actin are not induced by interactions with agLDL, but rather, F-actin-rich structures form almost exclusively at sites of contact between agLDL and the macrophage surface. This is reminiscent of the actin polymerization associated with phagocytic cups26. However, the process described here is distinct from phagocytosis because agLDL is not taken up immediately into a sealed, degradative compartment (i.e., a phagosome). Instead, agLDL remains in SCCs that are still open to the extracellular space, as demonstrated by the accessibility of the compartments to CtB.

The intimate spatial association of F-actin with the agLDL suggests that specific signaling mechanisms stimulate actin polymerization at areas of contact. Based on our previous work23, 25, we hypothesize that the local transfer of FC from agLDL drives the elaboration of F-actin rich membrane structures. We show here that macrophage engagement of agLDL leads to increases in FC at sites of contact with agLDL and that these sites colocalize with local increases in F-actin (Fig. 2). This process involves Rho-family GTPases, which are key regulators of many actin-dependent processes in cells27. Inhibition of Rac and Cdc42 activation completely abolished actin polymerization around agLDL. It appears that actin assembly leads to an increase in the area of contact with agLDL. We cannot rule out the possibility that other processes (e.g., stimulated secretion of lysosomal contents) are also affected.

The role of receptors in the interaction of agLDL with macrophages is not well defined. Low-density-lipoprotein-receptor-related protein (LRP) has been shown to play a role in the uptake of agLDL28. However, several other LDL-binding receptors were examined for their potential role in uptake of agLDL, and none of them were sufficient for this process13. In studies in mice, it was found that knockout of the scavenger receptors SRA and CD36 did not significantly reduce macrophage foam cell formation in ApoE−/− mice on a Western diet29, 30. In addition heparan sulfate proteoglycans of the syndecan family, in particular syndecan-4, were shown to mediate uptake of lipase-modified LDL31, 32.

Our prior studies showed that delivery of FC to cells via MβCD (and thus without any engagement of receptors) is sufficient for the induction of actin polymerization23. To test the necessity of FC delivery for actin polymerization following engagement of agLDL, we inhibited CE hydrolysis by replacing CE in agLDL with non-hydrolysable cholesteryl ether . We also used two additional approaches suggested by our characterization of the SCCs (A. Haka et al., submitted): 1) knocking-down LAL levels, and 2) application of the V-ATPase inhibitor, bafilomycin A1. Under each of these conditions, the size of the F-actin rich structures around agLDL decreased significantly, indicating that agLDL-derived FC is required for F-actin polymerization. It should be noted that none of these treatments should affect receptor-mediated interactions with agLDL, indicating that such receptor interactions by themselves are not sufficient to trigger the increase in F-actin. Additionally, actin polymerization appears to be required for local FC accumulation because toxin B treatment inhibited the local increases in FC at agLDL-membrane contact zones. Thus, extracellular CE hydrolysis and local actin polymerization induced by agLDL are mutually dependent processes.

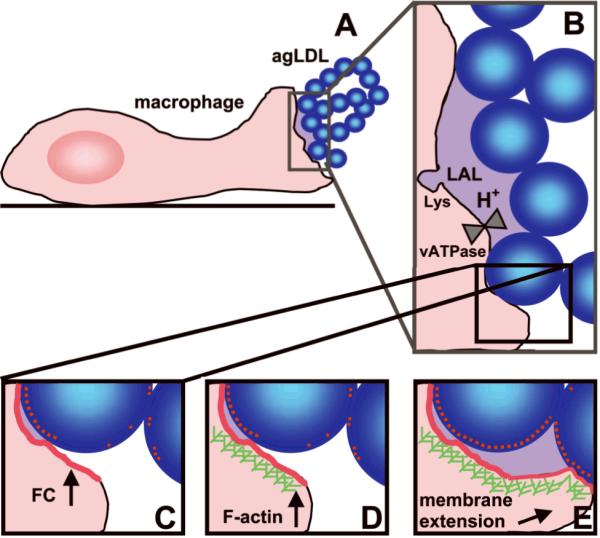

We propose a model for the interaction of macrophages with agLDL (Fig. 6). Upon contact with agLDL (Fig. 6A), an extracellular, acidified compartment is formed (Fig. 6B), allowing the hydrolysis of CE from agLDL (Fig. 6C). This leads to local increases in membrane FC (Fig. 6C), which induce localized actin polymerization (Fig. 6D) and membrane extension (Fig. 6E). This, in turn, promotes more extensive contact of the cell membrane with agLDL, resulting in further CE hydrolysis, FC transfer and actin polymerization, etc.; a pathologic cycle becomes established. The positive feedback loop may only be broken when the cell has hydrolyzed all the CE that is within reach. This model may evoke alternate approaches for the prevention of foam cell formation and atherosclerotic lesion progression.

Figure 6. Proposed feedback loop initiated by macrophage contact with agLDL.

Blue balls, agLDL. Red dots and lines, FC. Purple-shaded areas, acidified compartments. Green hatches, F-actin. Lys, lysosome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hong Du and Gregory Grabowski (The Children's Hospital Research Foundation, Cincinnati, OH) for generously providing recombinant phLAL.

Source of Funding This work was supported by NIH grant R37-DK27083.

Abbreviations

- ACAT

acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase

- agLDL

aggregated low density lipoprotein

- CE

cholesteryl ester

- FC

free cholesterol

- LAL

lysosomal acid lipase

- phLAL

human LAL produced in Pichia pastoris

- SCC

surface-connected compartment

- CtB

cholera toxin subunit B

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- V-ATPase

vacuolar ATPase

References

- 1.Maxfield FR, Tabas I. Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature. 2005;438:612–621. doi: 10.1038/nature04399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boren J, Gustafsson M, Skalen K, Flood C, Innerarity TL. Role of extracellular retention of low density lipoproteins in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:451–456. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabas I. Nonoxidative modifications of lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:123–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams KJ, Tabas I. Lipoprotein retention--and clues for atheroma regression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1536–1540. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000174795.62387.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P, Geng YJ, Aikawa M, Schoenbeck U, Mach F, Clinton SK, Sukhova GK, Lee RT. Macrophages and atherosclerotic plaque stability. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1996;7:330–335. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199610000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llodra J, Angeli V, Liu J, Trogan E, Fisher EA, Randolph GJ. Emigration of monocyte-derived cells from atherosclerotic lesions characterizes regressive, but not progressive, plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11779–11784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403259101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charo IF, Taubman MB. Chemokines in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Circ Res. 2004;95:858–866. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146672.10582.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Kranzhofer R, Clark S, Libby P. Macrophage foam cells from experimental atheroma constitutively produce matrix-degrading proteinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:402–406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng B, Yao PM, Li Y, Devlin CM, Zhang D, Harding HP, Sweeney M, Rong JX, Kuriakose G, Fisher EA, Marks AR, Ron D, Tabas I. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabas I. Consequences and therapeutic implications of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: the importance of lesion stage and phagocytic efficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2255–2264. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184783.04864.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakr SW, Eddy RJ, Barth H, Wang F, Greenberg S, Maxfield FR, Tabas I. The uptake and degradation of matrix-bound lipoproteins by macrophages require an intact actin Cytoskeleton, Rho family GTPases, and myosin ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37649–37658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buton X, Mamdouh Z, Ghosh R, Du H, Kuriakose G, Beatini N, Grabowski GA, Maxfield FR, Tabas I. Unique cellular events occurring during the initial interaction of macrophages with matrix-retained or methylated aggregated low density lipoprotein (LDL) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32112–32121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang WY, Gaynor PM, Kruth HS. Aggregated low density lipoprotein induces and enters surface-connected compartments of human monocyte-macrophages. Uptake occurs independently of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31700–31706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punturieri A, Filippov S, Allen E, Caras I, Murray R, Reddy V, Weiss SJ. Regulation of elastinolytic cysteine proteinase activity in normal and cathepsin K-deficient human macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;192:789–799. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rousselle AV, Heymann D. Osteoclastic acidification pathways during bone resorption. Bone. 2002;30:533–540. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Z, Huang Y, Adamopoulos IE, Walpole A, Triffitt JT, Cui Z. Macrophage-mediated biodegradation of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:582–590. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabas I, Lim S, Xu XX, Maxfield FR. Endocytosed beta-VLDL and LDL are delivered to different intracellular vesicles in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger M. Reconstitution of the hydrophobic core of low-density lipoprotein. Methods Enzymol. 1986;128:608–613. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)28094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du H, Schiavi S, Levine M, Mishra J, Heur M, Grabowski GA. Enzyme therapy for lysosomal acid lipase deficiency in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1639–1648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang WY, Ishii I, Kruth HS. Plasmin-mediated macrophage reversal of low density lipoprotein aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33176–33183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908714199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin C, Nagao T, Grosheva I, Maxfield FR, Pierini LM. Elevated plasma membrane cholesterol content alters macrophage signaling and function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:372–378. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000197848.67999.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinstein S, Nanda A, Lukacs G, Rotstein O. V-ATPases in phagocytic cells. J Exp Biol. 1992;172:179–192. doi: 10.1242/jeb.172.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagao T, Qin C, Grosheva I, Maxfield FR, Pierini LM. Elevated cholesterol levels in the plasma membranes of macrophages inhibit migration by disrupting RhoA regulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1596–1602. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castellano F, Chavrier P, Caron E. Actin dynamics during phagocytosis. Semin Immunol. 2001;13:347–355. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel M, Morrow J, Maxfield FR, Strickland DK, Greenberg S, Tabas I. The cytoplasmic domain of the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein, but not that of the LDL receptor, triggers phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44799–44807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning-Tobin JJ, Moore KJ, Seimon TA, Bell SA, Sharuk M, Alvarez-Leite JI, de Winther MP, Tabas I, Freeman MW. Loss of SR-A and CD36 activity reduces atherosclerotic lesion complexity without abrogating foam cell formation in hyperlipidemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:19–26. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.176644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore KJ, Kunjathoor VV, Koehn SL, Manning JJ, Tseng AA, Silver JM, McKee M, Freeman MW. Loss of receptor-mediated lipid uptake via scavenger receptor A or CD36 pathways does not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2192–2201. doi: 10.1172/JCI24061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyanovsky BB, Shridas P, Simons M, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR. Syndecan-4 mediates macrophage uptake of group V secretory phospholipase A2-modified LDL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:641–650. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800450-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuki IV, Kuhn KM, Lomazov IR, Rothman VL, Tuszynski GP, Iozzo RV, Swenson TL, Fisher EA, Williams KJ. The syndecan family of proteoglycans. Novel receptors mediating internalization of atherogenic lipoproteins in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1611–1622. doi: 10.1172/JCI119685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.