Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play an important role in regulation of gene expression through histone modifications. Here we show that the Aspergillus fumigatus HDAC HdaA is involved in regulation of secondary metabolite production and is required for normal germination and vegetative growth. Deletion of the hdaA gene increased the production of several secondary metabolites but decreased production of gliotoxin whereas over-expression hdaA increased production of gliotoxin. RT-PCR analysis of 14 non-ribosomal peptide synthases indicated HdaA regulation of up to 9 of them. A mammalian cell toxicity assay indicated increased activity in the over-expression strain. Neither mutant affected virulence of the fungus as measured by macrophage engulfment of conidia or virulence in a neutropenic mouse model.

Keywords: histone deacetylase, hdaA, secondary metabolism, Aspergillus fumigatus

Introduction

Both the structure and function of chromatin are affected by posttranslational modifications of histones, which include acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation (Turner et al. 2007). A recent genome-wide analysis in yeast shows the importance of chromatin modifiers in transcriptional regulation (Steinfeld et al. 2007). Among histone modifications, acetylation and methylation are the most widely studied and best understood (Brosch et al. 2008; Kurdistani and Grunstein 2003; Berger 2007). Both of these types of chromatin modifications have been demonstrated to have important effects on the production of fungal secondary metabolites (Shwab et al. 2007; Bok et al. 2009), which range from toxins to important antibiotics. Unlike genes involved in primary metabolic pathways, secondary metabolite (SM) pathway genes are almost always clustered in fungi. This fact makes fungal SMs well suited to regulation by localized modifications of chromatin structure. Fungi treated with methytransferase and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors were found to have increased diversity in natural product formation (Shwab et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2008).

It is generally known that the acetylation status of histones - controlled by the opposing actions of histone acetyltrasferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) - plays an important role in transcriptional regulation; however, the underlying mechanism is inconclusive. Some studies suggest that the acetylation status of histones affects chromatin structure. Hyperacetylation often favors euchromatin formation, leading to gene activation, while hypoacetylation favors heterochromatin formation and gene inactivation (Bulger 2005; Robyr et al. 2002; Trojer et al. 2003). Other studies seem to indicate that acetylation status could affect the interaction of regulatory proteins with histones rather than directly altering the structure of chromatin itself (Loidl et al. 1994; Loidl et al. 1998).

HDACs are enzymes that catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from lysine residues of core histone tails, but it is suggested that they also act on nonhistone substrates (Leipe et al. 1997). Several HDACs have been identified in filamentous fungi and their functions have been analyzed (reviewed in Brosch et al. 2008). In Aspergillus nidulans, HdaA, a major class 2 histone deacetylase, is involved both in normal growth under oxidative stress conditions and in regulation of telomere-proximal SM gene clusters (Tribus et al. 2005; Shwab et al. 2007). In addition, the production of SMs increased substantially in the hdaA deletion strain, though this effect was observed only with the telomere-proximal SM sterigmatocystin (ST) and penicillin (PN) clusters and not with the telomere-distal terraquinone (TR) gene cluster (Shwab et al. 2007). Moreover, HDACs seem to regulate SM clusters in other fungi. Treatment of a variety of fungi with the class 1 and class 2 HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) as well as other HDAC inhibitors including suberohydroxamic acid, vaplroic acid and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid increased production of numerous natural products, suggesting that HDACs may function in the regulation of SM among a broad range of fungal genera (Shwab et al. 2007, Williams et al. 2008).

SM production has been implicated as a factor in A. fumigatus virulence. Deletants of LaeA, a global regulator of SM clusters in Aspergillus and Penicillium species (Bok and Keller 2004, Kale et al. 2008, Kosalková et al. 2009), and deletants of genes specifically involved in production of a single metabolite, gliotoxin, have yielded A. fumigatus mutants impaired in pathogenicity (Bok et al. 2005, Kwon-Chung and Sugui 2008, Sugui et al. 2007, Spikes et al. 2008). Interestingly, SM was restored in an A. nidulans ΔlaeA background when combined with the ΔhdaA locus (Shwab et al. 2007), again supporting a role for chromatin remodeling in SM production. In this study, the A. fumigatus hdaA ortholog was deleted in order to determine its effect on SM production in this species. We find that ΔhdaA strains are aberrant in SM production in culture with many metabolites up-regulated but with the virulence factor gliotoxin repressed in production. Conversely, over-expression strains of hdaA produced more gliotoxin than wild type in culture. HdaA is also required for wild type germination and radial growth but its loss does not affect macrophage uptake of conidia or virulence in a neutropenic mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

A. fumigatus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. They were routinely grown on glucose minimal medium (GMM) amended with supplements as needed at 37°C (Shimizu and Keller 2001). For pyrG auxotrophs, GMM was supplemented with 5 mM uridine and uracil.

Table 1.

A. fumigatus strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AF293 | Wild type | Xue et al. 2004 |

| AF293.1 | pyrG1 | Xuen et al. 2004 |

| TIHL3.4 | pyrG1, pLMH26 (pyrG1+) | This study |

| TIHL1.10 | pyrG1, ΔhdaA::pyrG1 | This study |

| TIHL1.24 | pyrG1, ΔhdaA::pyrG1 | This study |

| TIHL5.5 | pyrG1, ΔhdaA::pyrG1, pIHL3 (hdaA+) | This study |

| TIHL5.7 | pyrG1, ΔhdaA::pyrG1, pIHL3 (hdaA+) | This study |

| TIHL4.3 | pyrG1, ΔcIrD::pyrG1 | This study |

Molecular genetic manipulation, Southern, and Northern analysis

DNA manipulations, Southern, and Northern analysis were conducted according to standard procedures (Sambrook and Russell 2001). Fungal DNA was isolated as described (Shimizu and Keller 2001) and RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers for probes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence1 | Use |

|---|---|---|

| AfuhdaAF1-F | 5’-GCCGACGTCCGTGTTGTCGACCTTATCGGTA-3’ | Amplification of upstream fragments of the hdaA gene |

| F1-RNCOI | 5’-GCCCCATGGACTTGGTCGCCTTAACATGCCA-3’ | |

| AfuhdaAF2-F | 5’-GCCACTAGTTGACAGATTCGCGCAGAACTCA-3’ | Amplification of downstream fragments of the hdaA gene |

| F2-RMLUI | 5’-GCCACGCGTTGATCATCACGGACCTGCCAGA-3’ | |

| HdaA-intF | 5’-CCTGAGCTGGACTTGTTCTACA-3’ | Screening of site-specific disruption of the hdaA gene |

| HdaA-disR | 5’-CTGACTAACAGGTCCGTACTGA-3’ | |

| F2-RkpnI | 5’- GCCGGTACCTGATCATCACGGACCTGCCAGA-3’ | Amplification of the hdaA gene Confirmation of the hdaA complementation |

| AfhdaA-R | 5’-TTGGATCAGGTGTCCGTAGCGT-3’ | |

| Gz-intF | 5’-AAGGGCCGGTAGTCTACCTCTTC-3’ | Amplification of the gliZ gene |

| Gz-intR | 5’-CGATCTGGTAGCTGCCCAGCTGGAAG-3’ | |

| JP-Actin-F | 5’-TGACAATGTTACCGTAGAGATCC-3’ 5’- | Amplification of the actin gene |

| JP-Actin-R | GGAGAAGATCTGGCATCACA-3’ |

Italicized (GCC) and underlined sequences were added as a clamp and for restriction enzyme digestion for convenient cloning, respectively.

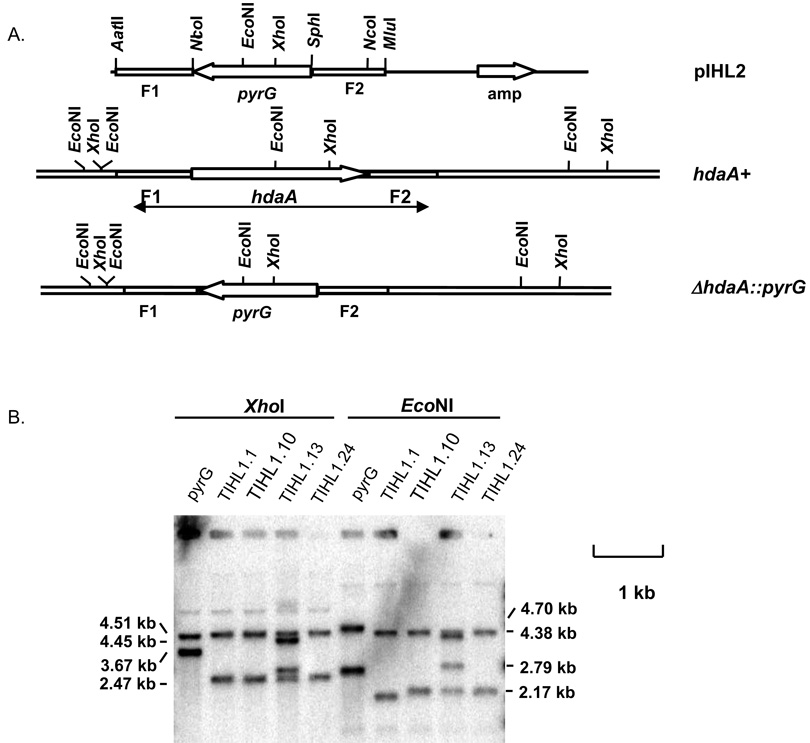

Disruption of the hdaA gene and complementation of ΔhdaA

A vector for the hdaA gene disruption, pIHL2, was constructed by insertion of a 1.1 kb upstream and a 1.0 kb downstream fragment of the hdaA gene on either side of the pyrG gene in pLMH26. The upstream and down stream fragments were obtained by PCR (Sambrook and Russell 2001) using TripleMaster polymerase (Eppendorf). Primers for PCR were designed based on the genomic sequence of the A. fumigatus hdaA gene (Gene ID: Afu5g198) (Broad Institute, http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/aspergillus_group/MultiHome.html) and are listed in Table 2. The AatII/NcoI fragments (upstream flanking fragments, primers AfuhdaAF1-F and F1-RNCOI) and SpeI/MluI fragments (downstream flanking fragments, primers AfuhdaAF2-F and F2-RMLUI) of PCR products were ligated to the equivalent restriction enzyme sites on either side of the pyrG gene in pLMH26 to construct pIHL2. The deletion construct (Fig. 1) was amplified using primers AfuhdaAF1-F and F2-RMLUI and the template pIHL2 and then used to transform A. fumigatus AF293.1 (a pyrG auxotroph, Xue et al. 2004) as described elsewhere (Bok et al. 2005). Transformants were screened for disruption by PCR using primers hdaA-intF and hdaA-disR. The site-specific disruption of the hdaA gene was confirmed by Southern analysis of the candidates screened by PCR. For Southern, standard procedure was used using a 32P labeled KpnI/SalI fragment of pIHL3 that covers the hdaA ORF and both upstream and downstream flanking sequences. As a control for Westerns, the clrD gene was also disrupted following details in Palmer et al. (2008) with the only difference being that clrD was replaced with A. fumigatus pyrG and not A. parasiticus pyrG in this study.

Figure 1. Disruption of the hdaA gene in A. fumigatus.

A. Schematic representation of a hdaA deletion construct. The PCR products (AatII-MluI fragments) were introduced into A. fumigatus (hdaA+ strain) to replace the entire hdaA ORF with the pyrG gene. B. Southern blot analysis of transformants. Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and EcoNI and separated by electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized with a 32P labeled KpnI/SalI fragment (shown as arrow in Panel A) that covers the hdaA ORF and both upstream and downstream flanking sequences. Lane 1 and 6 is TIHL3.4 (wild type hdaA). The other lanes are 4 transformants. Expected band sizes were 3.67 and 4.45 kb for wild type, 2.47 and 4.51 kb for ΔhdaA with XhoI digest, and 2.79 and 4.70 kb for wild type and 2. 17 and 4.38 kb for ΔhdaA with EcoNI digest, respectively. Transformants TIHL1.10 and 1.24 display correct fragment sizes.

To construct a plasmid for ΔhdaA complementation, the hdaA gene was recovered by PCR using primers AfuhdaAF1-F and F2-RKpnI. The primer F2-RkpnI was the same as F2RMLUI except for having the restriction enzyme site of KpnI instead of MluI. The KpnI/SalI framents of PCR products were ligated to the same sites of pUCH2–8, which contains the selectable marker hygromycin B phosphotransferase (Alexander et al. 1998), to create pIHL3. A ΔhdaA disruption mutant, TIHL1.24, was used for complementation. The complementation was confirmed by PCR using primers hdaA-intF and AfhdaA-R.

Phenotypic characterization and secondary metabolite analysis on solid media

Colony growth radius and spore production were measured as previously described (Jin et al. 2002). Germination rates of the strains were analyzed as described in Dagenais et al. (2008). SM production was assessed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). For TLC, 10 µl of 1 × 103 spore/µl was point-inoculated on the center of glucose minimal medium (GMM) or Czapek yeast agar (CYA) and cultured for 72 hr at 37°C. An agar plug of the center of colonies was removed and extracted for SMs according to the Smedsgaard’s method (Smedsgaard 1997). Extracts (15µl/sample) were loaded onto UV-coated silica TLC plates (Whatman, PE SIL G/UV, Maidstone, Kent, England) and metabolites were separated in the developing solvent toluene:ethyl acetate:formic acid (TFA, 5:4:1). Photographs were taken following exposure to UV radiation at 254 nm and 366 nm wavelengths.

Liquid culture secondary metabolite analysis

All A. fumigatus strains (107 spores/ml) were inoculated and grown in 50 ml liquid GMM at 25°C for 72 h, 96 h, and 144 h with shaking at 220 rpm. Biomass of all liquid cultures was collected through filtration using Miracloth (Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and lyophilized with the RCT60 lyophilizer system (Jouan Inc., Winchester, VA, USA) to adjust ethyl acetate volume for SM dilution. After the appropriate time period, 30 ml ethyl acetate was added to 50 ml whole culture and the mixture was agitated for 30 min at room temperature. The ethyl acetate extraction was then dried completely at room temperature and resuspended in 1 ml ethyl acetate. TLCs were performed as described above for solid culture. Gliotoxin is visualized at 255 nm.

Western analysis of histone modifications

Nuclei were prepared from the fungal strains TIHL3.4, TIHL1.24, TIHL5.7 and TIHL4.3 (Table 1). Spores (106 spores/ml) were inoculated into 200 ml of GMM and cultures were incubated for 48 hr at 37°C. Mycelia were collected by vacuum filtration and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen mycelia were ground to powder in a pre-chilled mortar under liquid nitrogen. Ground mycelia were transferred to 250 ml centrifugation tubes with 80 ml of nuclei isolation buffer (1 M sorbitol; 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5; 0.15 mM spermine; 0.5 mM spermidine; 10 mM EDTA; 2.5 mM PMSF) on ice. Samples were centrifuged in a GSA rotor (Sorvall, Asheville, NC) at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through a double layer of Miracloth (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA). The filtrate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g in a GSA rotor for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed and pellet was resuspended in 12 ml of suspension buffer (1 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 mM spermine, 0.5 mM spermidine, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM PMSF) on ice. The suspension was centrifuged in a JA-20 rotor (Sorvall) at 9,700 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of ST buffer (1 M sorbitol; 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5; 3 µl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail for fungi, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on ice. The suspension was transferred to a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 30 sec. The supernatant was transferred to a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and kept at −20°C.

For Western analysis, proteins resolved by tricine-SDS-PAGE (Schagger 2006) were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) and then probed with anti-histone H3 (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) at 1:5,000, anti-acetyl H3 (Upstate) at 1:1,000, anti-acetyl H3K9 antibodies (Upstate) at 1:1,000 dilution and anti-H3K9 trimethyl (Upstate) at 1:2,000. Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was used at 1:20,000 dilutions (Pierce, Lockford, IL). Western blot processing was performed as described by the manufacturer (Pierce).

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR analysis

Real-Time PCR was used for detection of relative expression level of NRPSs in A. fumigatus. All Aspergillus strains (TIHL3.4, TIHL1.24, and TIHL5.7) were grown in GMM liquid media at 25°C and harvested at three time points: 3 days, 4 days, and 6 days. Total RNA was extracted from lyophilized mycelium with Iso-RNA Lysis reagent (5 PRIME Inc., Gaithersburg, UD). Extracted total RNA was purified with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and diluted in equal amounts (1 µg/µl per sample). To remove contaminated genomic DNA, purified RNA was treated twice with DNaseI (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 1 µg of DnaseI-treated RNA from each strain, three time points each, were synthesized to cDNA with iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA); no reverse transcriptase-treated RNA from each condition were used as negative controls. Reaction set-up for real-time RT-PCR was conducted with IQ SYBR® Green supermix (Bio-Rad) in total 20 µl reaction volume. The same real-time RT-PCR primers as in Cramer et al. (2006) were used for the 14 putative NRPS genes and My IQ™ single color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) performed relative expression level analysis. Temperature gradients for all NRPS primers were analyzed and then melt curve analysis was performed using the same product to confirm nonspecific products and primer dimers. For more exact results, real-time efficiency of all NRPS and the actin gene were tested with standard curve using the Ct (Threshold cycle) value of each real-time PCR reaction mixture including 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, and 1:16 dilution series of cDNA. Relative expression levels were calculated in IQ™5 optical system software using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). All values (3 replications) were normalized with the expression ratio of the actin gene as a reference and NRPS expression values of the wild type strain as a calibrator.

Macrophage phagocytosis assay

The MH-S and RAW 264.7 cell lines were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), gentamycin (Sigma), and 0.05mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). MH-S (105/ well) and RAW cells (5×104/well) were incubated overnight (18 hr) at 37°C, 5% CO2 in 16-well chamber slides (Nunc, Rochester, NY). Macrophages were co-incubated with conidia (2.5×105 conidia/well) for one hour, washed twice with RPMI media, and incubated an additional two hours before fixation in 2% formaldehyde. Calcofluor white (Sigma) was used to label and exclude extracellular conidia from analysis. The percent uptake (number of macrophages with conidia/total number of macrophages x 100) was determined from triplicate wells, and at least 100 macrophages per well were counted. These experiments were conducted in triplicate.

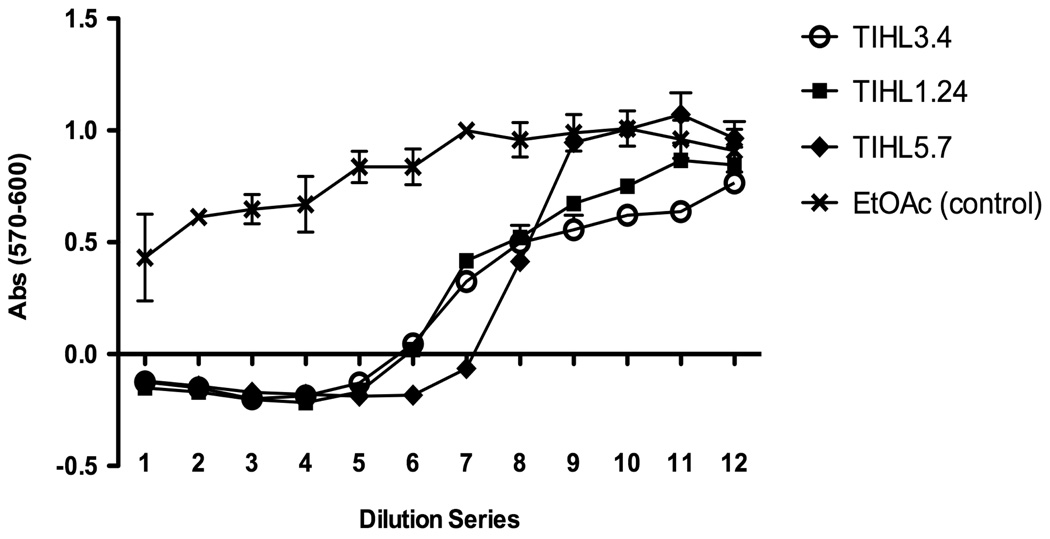

Mammalian cell toxicity assays

Ethyl acetate extracts, normalized across strains using the total dry biomass, were tested for mammalian cell toxicity against the RAW 264.7 cell line. 30 µl from each of four replicates per strain (TIHL3.4, TIHL1.24, TIHL5.7) were combined, evaporated, and resuspended in 360 µl of RPMI media to make the extract stock. Macrophages were cultured at 2×104 cells/well in 96-well plates for 24 hrs at 37°C, 5% CO2, and spent media was replaced with 80 µl of fresh RPMI media. 20 µl of 2-fold dilutions of each extract stock were then added in duplicate to the macrophages for 18 hrs at 37°C, 5% CO2, followed by the addition of 20 µl of 2 mM resazurin for an additional 2 hrs. Ethyl acetate was used as a control, and wells containing no compound (cells only) are shown as dilution 12 in the control series. Absorbance (570–600) was used to indicate cell viability.

Animal model of Aspergillus infection

Virulence of near-isogenic strains of A. fumigatus differing only in presence of hdaA genes (TIHL3.4, TIHL1.24 and TIHL5.7) was assessed in a lung infection model as described previously (Bok et al. 2006). Briefly, six week old, outbred Swiss ICR mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley) weighing 24–27 g were immunosuppressed by intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg) on days –4 and –1, and 3 and with a single dose of cortisone acetate (200 mg/kg) on the morning of infection. Anesthetized mice (10 mice/fungal strain) were infected by nasal instillation of 50 µl of 5 × 106 conidia/ml (day 0), and monitored three times daily for 7 days post-infection.

Results

Deletion of the hdaA gene

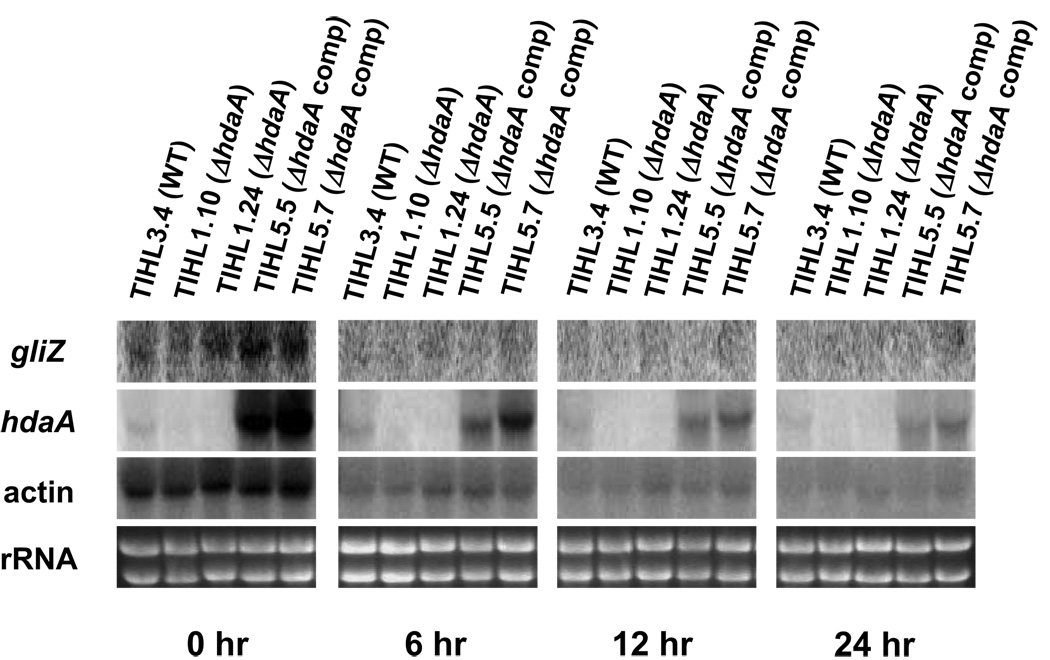

Search of the A. fumigatus genome revealed that the A. fumigatus hdaA gene is composed of 8 introns and 9 exons and encodes a polypeptide with 602 amino acids. The complete ORF of the hdaA gene was deleted and replaced with the A. fumigatus pyrG gene in AF293.1 (pyrG auxotroph). Site-specific disruption was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1). Disruption mutants showed the expected pattern of DNA hybridization for a single gene replacement. A wild type control (TIHL3.4) was constructed by transforming AF293.1 with pLMA26, which contains the native pyrG gene. Northern blot analysis showed that the expression of the hdaA gene was lost in disruption mutants, confirming the complete disruption of the hdaA gene (Fig. 2). Complementation of the deletant strain TIHL1.24 resulted in two strains (TIHL5.5 and TIHL5.7), each of which over-expressed hdaA (Fig. 2). The reason for the over-expression is unknown.

Figure 2. Gene expression during induction of asexual development.

Spores (1×106/ml) were inoculated to 200 ml of CYA media and incubated for 16 h at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Mycelium was collected by filtration with Miracloth. Filtrated mycelial mats were cut into four pieces and each piece was placed onto CYA plates and incubated for indicated time (1, 6, 12 and 24 hr). mRNA extracted from these time points was probed with gliZ, hdaA and actin.

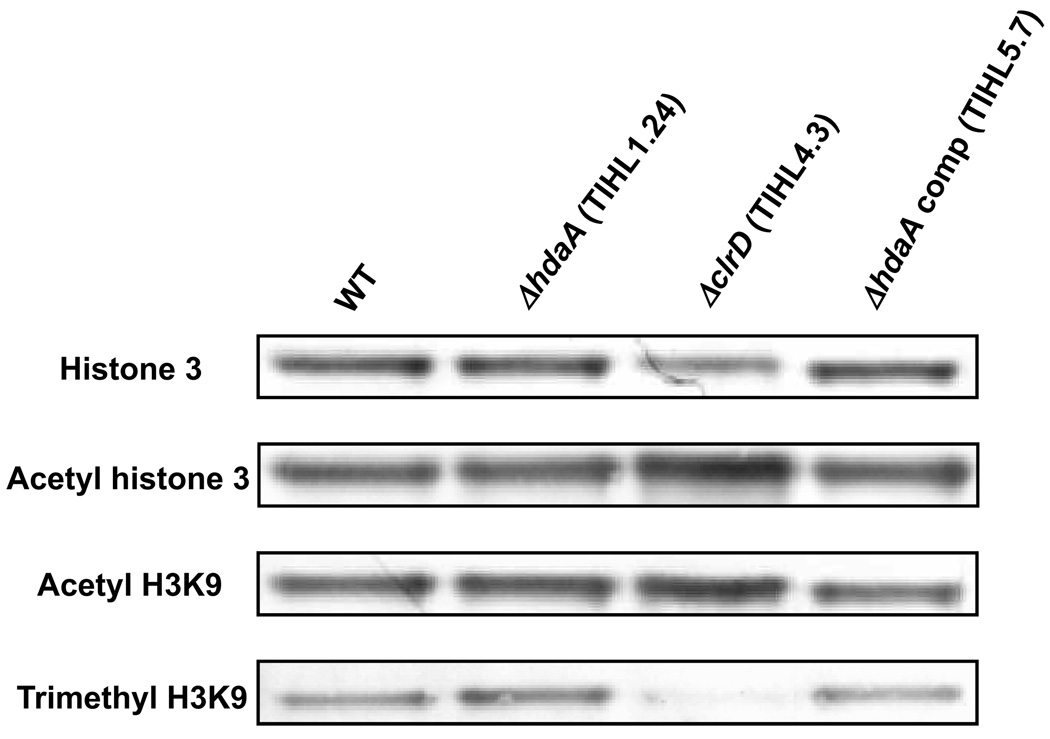

HdaA deacetylates H3K9

In A. nidulans, HdaA accounts for the predominant HDAC activity (Tribus et al. 2005). To see effects of ΔhdaA on histone modifications, histone 3 general acetylation, H3K9 acetylation, and H3K9 trimethylation were assayed by Western analysis. The levels of these modifications were compared among a ΔhdaA mutant, a wild type strain, and a ΔclrD mutant (where ClrD is required for H3K9 methylation, Palmer et al. 2008) as well as a complemented hdaA control. Whereas the level of histone 3 acetylation in ΔhdaA relative to wild type and complementation strains did not differ greatly, the level of H3K9 methylation was slightly higher in the ΔhdaA strain as determined by scanning density of the bands in Figure 3. The ΔclrD mutant showed considerable increases in the levels of H3 general acetylation and H3K9 acetylation, and showed a marked decrease in H3K9 methylation, as expected from a prior study (Palmer et. al. 2008).

Figure 3. Western analysis.

Nuclear proteins were separated by 10% Tricine-SDS-PAGE and followed by Western analysis. Antibodies used were anti-histone 3 (1:5,000), anti-acetyl histone 3 (1:1,000), and anti-acetyl H3K9 (1:1,000). Strains were TIHL3.4 (wild type), TIHL1.24 (ΔhdaA), TIHL4.3 (ΔclrD), and TIHL5.7 (ΔhdaA complement).

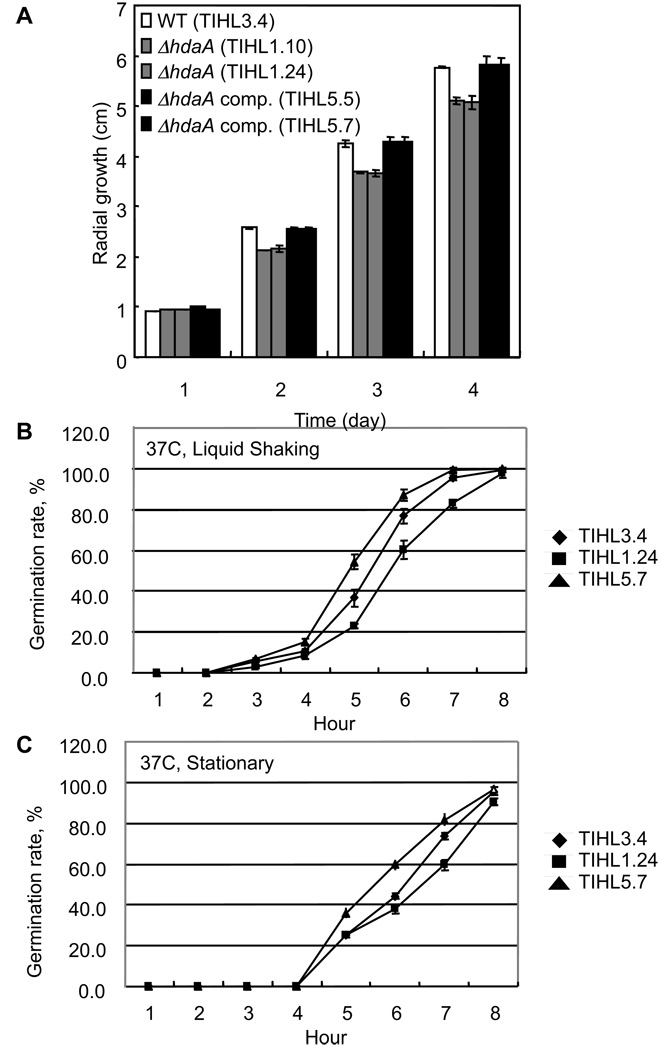

HdaA affects germination rate and vegetative growth

A. nidulans growth rate was not affected by hdaA loss on media of several different carbon and nitrogen sources (Tribus et al. 2005). However, A. fumigatus ΔhdaA strains showed a statistically significant reduction of growth under standard culture conditions on GMM and CYA media (Fig. 4a). This may be related to the decreased germination rate of this mutant (Fig. 4a and 4b). Interestingly the germination rate was increased in the over-expression complement although radial growth remained the same as wildtype.

Figure 4. Radial growth and germination of A. fumigatus strains.

A. Spores (104) were inoculated on the center of GMM plates and incubated at 37°C Radial growth was compared by measuring the diameter of colonies at indicated times. Values are the average of three colonies. B and C. Conidia were incubated in (B) shaking or (C) stationary liquid GMM/0.1% YE at the times indicated. 100 conidia for each strain were assessed for germination. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

In addition, colony morphology was slightly different from controls; pigmentation on the reverse side of ΔhdaA colonies was reduced and colony growth produced an uneven leading edge (data not shown). Conidial production was indistinguishable between ΔhdaA, complement ΔhdaA and wild type (data not shown). In contrast to findings reported for A. nidulans ΔhdaA (Tribus et al. 2005), the growth of A. fumigatus ΔhdaA was not affected under oxidative stress conditions (data not shown).

Production of secondary metabolites in ΔhdaA

In A. nidulans, the deletion of the hdaA gene resulted in increased gene expression and subsequent production of ST and PN, both of which are subtelomerically located. However, the telomere-distal TR cluster was expressed similarly in wild type and the ΔhdaA mutant leading to the hypothesis that HdaA negatively regulated subtelomeric clusters (Shwab et al. 2007). Here we examined the effects of ΔhdaA on SM production in A. fumigatus with regard to telomere proximity of NRPS genes by growing the fungus both in liquid shake and solid agar medium.

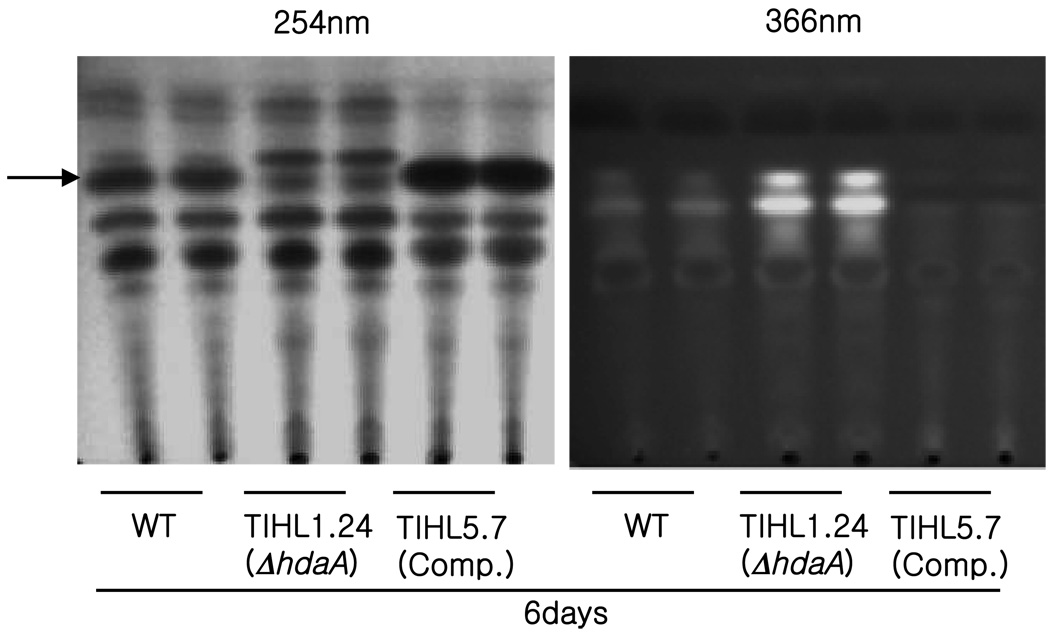

Growth in liquid shake conditions resulted in significant differences in the SM profile of the ΔhdaA strain and the complemented strain by both four and six days (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure 1a). RT-PCR analysis of NRPS gene expression in the three strains demonstrated that HdaA negatively regulated several NRPS but positively regulated the gliotoxin NRPS, GliP (NRPS10), which was repressed in ΔhdaA (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1b). This positive regulation was also true for NRPS9 encoding an unknown metabolite, possibly for NRPS4 (siderophore) in the earlier time points, and for NRPS11 (unknown). The complemented strain, which showed enhanced hdaA expression (Fig. 2), showed increased expression of both NRPS9 and NRPS10. The increase in NRPS10 expression was complementary to the increase in gliZ expression seen in Northern data (Fig. 2, gliZ is the transcription factor required for gliP expression, Bok et al. 2006). In contrast, our results showed that HdaA appeared to repressed the expression of 4 NRPS: NRPS1 (pes1 synthase), NRPS12 (unknown), NRPS13 (fumitremorgin B), NRPS14 (pseurotin) and possibly NRPS7 (putative siderophore). There appeared to be no correlation between the chromosome locality of the NRPS gene and regulation by HdaA (Table 3). Extracts from cultures grown in solid media did not show such striking differences in SM production (data not shown).

Figure 5. Thin layer analysis of secondary metabolites.

Spores (107/ml) were inoculated into GMM liquid media and incubated for 6 days at 25°C. The secondary metabolites were extracted with ethyl acetate and extracts were loaded onto UV-coated silica TLC plates. Metabolites were separated in developing solvent (toluene:ethyl acetate:formic acid, 5:4:1) and photos were taken following exposure to 254nm and 366nm UV radiation. Arrow points to gliotoxin which is only visualized in the 254nm picture (see Supplementary Fig. 1a in addition).

Table 3.

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis of NRPSs in wild type, ΔhdaA, and complemented ΔhdaA A. fumigatus strains.

| 3 days b | 4 days b | 6 days b | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRPSa (Gene Locus ID) | Secondary Metabolism Gene Cluster Number | Predicted product and function | LaeA Regulation HdaA Regulation | Distance from Telomere (Mb) | Wild Type | ΔhdaA | Complemented Control | Wild Type | ΔhdaA | Complemented Control | Wild Type | ΔhdaA | Complemented Control |

| NRPS1 | 1 | Nonribosomal peptide | Yes | 2.21 | 21.28±0.434 | 21.83±0.102 | 20.61±0.050 | 22.02±0.144 | 22.79±0.093 | 22.07±0.052 | 22.36±0.278 | 21.28±0.068 | 21.97±0.145 |

| (Afu1g10380) | synthase Afpes1 | Yes | 1.00±0.032 | 0.80±0.091 | 1.09±0.094 | 1.00±0.125 | 1.12±0.136 | 1.14±0.114 | 1.00±0.203 | 2.75±0.245 | 1.23±0.169 | ||

| NRPS2 | 2 | sidC, Ferrichrome | No | 0.20 | 22.63±0.054 | 22.72±0.043 | 21.74±0.028 | 21.9±0.155 | 23.64±0.132 | 23.14±0.005 | 23.98±0.083 | 23.97±0.088 | 23.55±0.109 |

| (Afu1g17200) | Siderophore | No | 1.00±0.093 | 0.83±0.068 | 1.19±0.097 | 1.00±0.155 | 0.90±0.084 | 1.31±0.082 | 1.00±0.146 | 1.26±0.109 | 1.08±0.115 | ||

| NRPS3 | 7 | sidE, Putative unknown | Yes–iron | 0.89 | 24.02±0.003 | 23.05±0.022 | 23.99±0.210 | 23.79±0.419 | 25.69±0.118 | 23.68±0.057 | 23.8 9±0.320 | 24.09±0.081 | 23.14±0.297 |

| (Afu3g03350) | Siderophore | No | 1.00±0.040 | 1.34±0.038 | 0.64±0.093 | 1.00±0.137 | 1.25±0.139 | 1.16±0.120 | 1.00±0.254 | 1.09±0.091 | 1.33±0.286 | ||

| NRPS4 | 7 | Nps6, Oxidative stress/ | Yes–iron | 0.91 | 24.52±0.032 | 25.34±0.060 | 24.3 0±0.081 | 23.89±0.163 | 26.36±0.017 | 25.62±0.010 | 25.48±0.313 | 25.66±0.284 | 26.41±0.090 |

| (Afu3g03420) | sidD, siderophore | (Yes weak) | 1.00±0.238 | 0.54±0.058 | 1.05±0.115 | 1.00±0.120 | 0.49±0.032 | 0.76±0.112 | 1.00±0.437 | 1.55±0.338 | 0.77±0.051 | ||

| NRPS5 | 8 | Putative unknown ETP | Yes | 0.66 | 19.67±0.457 | 19.48±0.047 | 19.32±0.110 | 20.10±0.169 | 20.73±0.064 | 20.13±0.065 | 20.50±0.460 | 20.79±0.036 | 21.48±0.010 |

| (Afu3g12920) | toxin | No | 1.00±0.321 | 1.34±0.126 | 0.87±0.094 | 1.00±0.137 | 1.25±0.139 | 1.16±0.120 | 1.00±0.320 | 1.13±0.858 | 0.50±0.043 | ||

| NRPS6 | 9 | Nonribosomal peptide | No | 0.48 | 25.02±0.221 | 25.98±0.197 | 24.88±0.082 | 25.80±0.085 | 27.48±0.253 | 24.89±0.189 | 28.05±0.500 | 29.12±0.097 | 28.11±0.114 |

| (Afu3g13730) | synthase, putative | No | 1.00±0.168 | 0.61±0.098 | 0.75±0.073 | 1.00±0.251 | 0.40±0.072 | 0.61±0.099 | 1.00±0.385 | 0.63±0.056 | 0.73±0.071 | ||

| NRPS7 | 11 | Putative unknown | No | 0.08 | 30.74±0.108 | 30.17±0.393 | 30.54±0.337 | 31.09±0.342 | 31.34±0.309 | 32.69±0.200 | 34.29±0.782 | 34.36±0.450 | 34.02±0.804 |

| (Afu3g15270) | Siderophore | Yes weak | 1.00±0.168 | 1.47±0.456 | 0.86±0.222 | 1.00±0.245 | 1.53±0.339 | 1.30±0.189 | 1.00±0.613 | 1.78±0.552 | 1.38±0.757 | ||

| NRPS8 | 15 | Nonribosomal peptide | No | 0.56 | 22.69±0.027 | 22.49±0.065 | 22.15±0.140 | 22.61±0.110 | 24.68±0.111 | 23.71±0.206 | 21.33±0.241 | 22.23±0.040 | 21.53±0.154 |

| (Afu5g12730) | synthase, putative | No | 1.00±0.088 | 1.00±0.087 | 0.93±0.115 | 1.00±0.161 | 0.60±0.090 | 1.0±0.148 | 1.00±0.211 | 0.68±0.047 | 0.7±0.091 | ||

| NRPS9 | 18 | Nonribosomal peptide | Yes | 1.56 | 22.49±0.012 | 23.61±0.048 | 22.77±0.032 | 22.54±0.063 | 25.32±0.113 | 22.88±0.033 | 21.44±0.201 | 21.87±0.096 | 20.40±0.133 |

| (Afu6g09610) | synthase, putative | Yes | 1.00±0.052 | 0.52±0.025 | 0.90±0.055 | 1.00±0.094 | 0.4±0.052 | 2.19±0.135 | 1.00±0.221 | 0.97±0.087 | 1.59±0.178 | ||

| NRPS10 | 18 | gliP, Gliotoxin | Yes | 1.44 | 19.71±0.463 | 21.82±0.335 | 20.13±0.431 | 19.72±0.603 | 23.05±0.061 | 19.84±0.025 | 18.16±0.396 | 19.91±0.057 | 18.07±0.080 |

| (Afu6g09660) | biosynthesis | Yes | 1.00±0.315 | 0.27±0.061 | 0.82±0.241 | 1.00±0.414 | 0.32±0.034 | 2.59±0.153 | 1.00±0.275 | 0.4U0.032 | 1.29±0.256 | ||

| NRPS11 | 19 | Nonribosomal peptide | Yes | 0.78 | 18.29±0.240 | 18.62±0.023 | 17.96±0.098 | 17.40±0.222 | 20.39±0.114 | 18.95±0.148 | 21.33±0.233 | 21.46±0.104 | 20.73±0.117 |

| (Afu6g12050) | synthase, putative | Yes weak | 1.00±0.191 | 0.69±0.054 | 0.82±0.087 | 1.00±0.178 | 0.36±0.046 | 0.93±0.111 | 1.00±0.260 | 1.17±0.150 | 1.18±0.202 | ||

| NRPS12 | 19 | Nonribosomal peptide | Yes | 0.76 | 20.00±0.070 | 19.8±0.055 | 19.57±0.077 | 18.85±0.050 | 21.25±0.135 | 20.64±0.051 | 22.94±0.349 | 22.72±0.071 | 22.53±0.029 |

| (Afu6g12080) | synthase, putative | Yes | 1.00±0.111 | 2.00±0.317 | 0.96±0.053 | 1.00±0.045 | 0.71±0.086 | 1.00±0.758 | 1.00±0.307 | 1.72±0.591 | 1.02±0.153 | ||

| NRPS13 | 22 | ftmPS, Fumitremorgin B or | Yes | 0.21 | 18.43±0.100 | 18.65±0.025 | 18.16±0.030 | 18.77±0.380 | 21.15±0.023 | 20.98±0.085 | 20.93±0.043 | 20.01±0.028 | 19.93±0.163 |

| (Afu8g00170) | derivatives | Yes | 1.00±0.109 | 0.75±0.059 | 0.78±0.064 | 1.00±0.258 | 0.71±0.051 | 0.74±0.066 | 1.00±0.094 | 2.50±0.174 | 1.60±0.196 | ||

| NRPS14 | 22 | PKS/NRPS hybrid, | Yes | 0.12 | 16.50±0.082 | 16.05±0.039 | 15.47±0.017 | 15.65±0.173 | 16.80±0.135 | 16.69±0.113 | 18.7±0.032 | 17.91±0.012 | 18.76±0.048 |

| (Afu8g00540) | pseurotin biosynthesis | Yes | 1.00±0.116 | 2.39±0.570 | 1.47±0.035 | 1.00±0.124 | 1.72±0.181 | 1.31±0.152 | 1.00±0.038 | 2.79±0.243 | 1.02±0.080 | ||

Nomenclature in Cramer et al. (2006)

Mean value of cycle threshold ± SD (upper numbers in each cell) and relative expression level ± SD (lower number in each cell). All data were triplicate.

Dataset of Actin gene and wild type A. fumigatus were used as reference gene and calibrator respectively

Host response to hdaA mutants

Considering the alteration in secondary metabolite production – albeit as observed in culture media -, we thought it possible the hdaA mutants might display altered virulence properties. Whereas macrophage uptake experiments (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and a neutropenic pulmonary mouse model (Supplementary Fig. 2b) showed no statistical difference between the wild type, ΔhdaA and over-expression ΔhdaA complement strains, extracts from the three strains differentially affected macrophage viability (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Effect of fungal extracts on mammalian cell viability.

RAW 264.7 cells (2×104/well) were cultured for 24 hrs in 96-well plates, and serial dilutions of extracts, normalized to dry biomass, were added to the macrophages for 18 hrs. Resazurin was used to determine cell viability; after a 2 hr incubation with resazurin, absorbance (570nm-600nm) was measured. Four replicates of extract per strain were combined and assayed in duplicate; mean absorbance +/− standard error is shown.

Ethyl acetate extracts, normalized across strains by dry biomass, were tested for toxicity against the mammalian cell line RAW 264.7. Extracts were evaporated, resuspended in RPMI media, and serial 2-fold dilutions (1–12) were added to macrophages for 18 hrs before assaying cell viability with resazurin. As seen in Figure 6, extracts from the wild type and ΔhdaA strains were indistinguishable in their ability to induce cell death at any dilution. Extracts from the over-expression strain induced slightly greater cell death at equivalent biomass (dilution 6 and 7), perhaps in part a result of the increased gliotoxin present in these samples (Fig. 5). There appeared a reduction in toxicity, however, in this strain at further dilutions which could be associated with lower production of other metabolites in this strain, possibly some of the metabolites observed in the 366 nm TLCs (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig.1a). No significant differences in cell death were observed in the ethyl acetate control wells as compared to the cells only control (dilution 12 of the ethyl acetate series).

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that chromatin modifications – including histone acetylation/deacetylation - are important in regulation of SM clusters in A. nidulans (Shwab et al, 2007, Bok et al. 2009). Here we have demonstrated that deletion of the hdaA gene encoding a putative histone deacetylase also results in an altered secondary metabolite profile in A. fumigatus (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 3). This result is consistent with our previous observations in which the inhibition of HDACs by TSA in Alternaria alternata and Penicillium expansum increased the production of numerous unknown secondary metabolites but also resulted in the loss of a few metabolites (Shwab et al, 2007). Chemical inhibition of HDACs has also been demonstrated to enhance the chemical diversity of secondary metabolites produced by fungi from the genera Clonostachys, Diatrype and Verticillium (Williams et al. 2008). A detailed look at ΔhdaA effects on three SM gene clusters in A. nidulans revealed that the two subtelomeric clusters were upregulated in the ΔhdaA mutant, leading us to propose that HdaA was a negative repressor of subtelomeric clusters in this species (Shwab et al, 2007). In the current study where we assessed the expression of all 14 NRPS genes in A. fumigatus, there was no association with distance from telomere and positive or negative HdaA effects on NRPS gene expression (Table 3). An examination of expression of additional SM clusters in A. nidulans should resolve the question as to whether HdaA regulation of SM clusters is location specific in A. nidulans but not A. fumigatus.

Regardless of location, there was considerable overlap in HdaA and LaeA regulation of NRPS. LaeA also regulated – all positively - NRPS1, NRPS4 (in high iron conditions), NRPS9, NRPS10, NRPS11, NRPS12, NRPS13 and NRPS14 (Table 3 and Perrin et al, 2007). In some cases, LaeA and HdaA showed opposite (e.g. NRPS1 Pes1 and NRPS14 pseurotin) and some cases similar (e.g. NRPS10 gliotoxin and NRPS9) regulation of these genes. Currently, the only metabolite with sufficient studies to strongly support a role in pathogenesis is gliotoxin (Bok et al. 2005, Kwon-Chung and Sugui 2008, Sugui et al. 2007, Spikes et al. 2008). Other metabolites may have a potential to damage mammalian cells including the Afpes1 metabolite required for virulence in an insect model of IA (Reeves et al. 2006), the tremorgenic mycotoxin fumitremorgin B whose derivatives are cytotoxic (Grundmann and Li 2005; Maiya et al. 2006), and pseurotin, an inhibitor of chitin synthase and an inducer of nerve-cell proliferation (Maiya et al. 2007).

We queried if the deletion of the hdaA gene would impact virulence due to the altered production of secondary metabolites in this mutant, some of which might be important for virulence. The deletion of LaeA, a positive regulator of many secondary metabolites, yielded a less pathogenic strain and this reduced virulence was associated with decreased levels of several metabolites including pulmonary gliotoxin (Bok 2005; Bok 2006). However, ΔhdaA virulence was not statistically different from that of wild type in a murine pulmonary model (Supplementary Fig. 2b), nor were any aberrancies in macrophage uptake observed (Fig. 2a). This was true for the over-expression ΔhdaA complement as well. It may be of interest to examine virulence of this mutant in a non-neutropenic mouse model or other model as other models have picked up differences in virulence undetected by the neutropenic model. The mammalian toxicity assay on the other hand suggested altered activity in the over-expression hdaA strain (Fig. 6) which could possibly be related to the increased gliotoxin production and/or diminishment of other metabolites in culture by this strain (Fig. 5). It is important to note that metabolites produced in culture do not necessarily correspond to metabolites produced in host cells.

The joint regulation of several NRPS by HdaA and LaeA, and subsequent altered metabolite profiles in mutants of these genes, supports a case for chromatin structure in regulation of these particular secondary metabolite genes. Alterations in expression may be associated with increased histone acetylation or altered histone methylation as a consequence of acetylation changes. For example, recently data has linked a decrease in H3K4 and K9 methylation with expression of silent gene clusters in A. nidulans (Bok et al. 2009). Hyperacetylation is generally considered to be associated with gene activation, though histone deacetylation also appears to promote gene expression in some instances (Wang et al. 2002; Fukuda et al. 2006). The conditions here did not support a strong role for HdaA acetylation of H3 as determined by Western analysis. The target for HdaA is yet to be determined in filamentous fungi, and our results suggest that histone 3 may not be a main target for HdaA or that other HDACs may be involved in histone 3 modifications. In addition to direct histone interactions, HdaA could possibly act on nonhistone regulatory and structural proteins that interact with chromatin. The changes in histone modifications observed in the ΔclrD mutant are consistent with expectations, with acetylation of H3 increasing and methylation decreasing, the latter observation reported earlier (Palmer et al. 2008).

The data presented here indicate a role for HdaA and histone acetylation in the development – particularly germination rate - of A. fumigatus as well as its production of secondary metabolites. A growth defect was also observed in an A. fumigatus ΔclrD mutant (Palmer et al. 2008), suggesting that histone modifications might have a role in A. fumigatus developmental biology. With regard to the regulation of SM clusters, it remains unclear what factors, such as chromosome location, are involved in determining why some gene clusters seem to be affected by this HDAC while others are not.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the research program 2009 of Kookmin University in Korea to I. L. and NIH R01 AI065728-01A1 to N.P.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander NJ, Hohn TM, McCormick SP. The TRI11 Gene of Fusarium sporotrichioides encodes a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase required for C-15 hydroxylation in trichothecene biosynthesis. Applied Environmental Biotechnology. 1998;64:221–225. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.221-225.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Keller NP. LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp. Eukaryotic Cell. 2004;3:527–535. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.527-535.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, Frisvad JC, Keller NP. LaeA, a regulator of morphogenetic fungal virulence factors. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4:1574–1582. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1574-1582.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Chung D, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, Frisvad JC, Kirby KA, Keller NP. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infectious Immunology. 2006;74:6761–6768. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00780-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Chiang Y-M, Szewczyk E, Reyes-Domingez Y, Davidson AD, Sanchez JF, Lo H-C, Watanabe K, Strauss J, Oakley BR, Wang CCC, Keller NP. Chromatin-regulation of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Chem Biol. 2009 May 17; doi: 10.1038/nchembio.177. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch G, Loidl P, Graessle S. Histone modifications and chromatin dynamics: a focus on filamentous fungi. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2008;32:409–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger M. Hyperacetylated chromatin domains: lessons from heterochromatin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:21689–21692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer RA, Jr, Stajich JE, Yamanaka Y, Dietrich FS, Steinbach WJ, Perfect JR. Phylogenomic analysis of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases in the genus Aspergillus. Gene. 2006;383:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais T, Chung D, Giles S, Hull C, Andes D, Keller NP. Abberancies in conidiophore development and conidial/macrophage interactions in a dioxygenase mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3214–3220. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00009-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H, Sano N, Muto S, Horikoshi M. Simple histone acetylation plays a complex role in the regulation of gene expression. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics. 2006;5:190–208. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann A, Li SM. Overproduction, purification and characterization of FtmPT1, a brevianamide F prenyltransferase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiology. 2005;151:2199–2207. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27962-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Bok JW, Guzman-de-Peña D, Keller NP. Requirement of spermidine for developmental transitions in Aspergillus nidulans. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;46:801–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale SP, Milde L, Trapp MK, Frisvad JC, Keller NP, Bok JW. Requirement of LaeA for secondary metabolism and sclerotial production in Aspergillus flavus. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2008;45:1422–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosalková K, García-Estrada C, Ullán RV, Godio RP, Feltrer R, Teijeira F, Mauriz E, Martín JF. The global regulator LaeA controls penicillin biosynthesis, pigmentation and sporulation, but not roquefortine C synthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochimie. 2009;91:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani SK, Grunstein M. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature Reviews Cell and Molecular Biology. 2003;4:276–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Sugui JA. What do we know about the role of gliotoxin in the pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus? Med Mycol. 2008;2:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13693780802056012. 2008 May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipe DD, Landsman D. Histone deacetylases, acetoin utilization proteins and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases are members of an ancient protein superfamily. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:3693–3697. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl P. Histone acetylation: facts and questions. Chromosoma. 1994;103:441–449. doi: 10.1007/BF00337382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiya S, Grundmann A, Li SM, Turner G. The fumitremorgin gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus: identification of a gene encoding brevianamide F synthetase. Chembiochem. 2006;7:1062–1069. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiya S, Grundmann A, Li X, Li SM, Turner G. Identification of a hybrid PKS/NRPS required for pseurotin A biosynthesis in the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Chembiochem. 2007;8:1736–1743. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JM, Perrin RM, Dagenais TR, Keller NP. H3K9 methylation regulates growth and development in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008;7:2052–2060. doi: 10.1128/EC.00224-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin RM, Fedorova ND, Bok JW, Cramer RA, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Nierman WC, Keller NP. Transcriptional regulation of chemical diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus by LaeA. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves EP, Reiber K, Neville C, Scheibner O, Kavanagh K. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase (Pes1) confers protection against oxidative stress in Aspergillus fumigatus. FEBS Journal. 2006;273:3038–3053. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robyr D, Suka Y, Xenarios I, Kurdistani SK, Wang A, Suka N, Grunstein M. Microarray deacetylation maps determine genome-wide functions for yeast histone deacetylases. Cell. 2002;109:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H. Tricine-SDS-PAGE. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:16–22. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwab EK, Bok JW, Tribus M, Galehr J, Graessle S, Keller NP. Histone deacetylase activity regulates chemical diversity in Aspergillus. Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6:1656–1664. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Keller NP. Genetic involvement of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase in a G protein signaling pathway regulating morphological and chemical transitions in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 2001;157:591–600. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedsgaard J. Micro-scale extraction procedure for standardized screening of fungal metabolite production in cultures. Journal of Chromatography A. 1997;760:264–270. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spikes S, Xu R, Nguyen CK, Chamilos G, Kontoyiannis DP, Jacobson RH, Ejzykowicz DE, Chiang LY, Filler SG, May GS. Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:479–486. doi: 10.1086/525044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld I, Shamir R, Kupiec M. A genome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrates the influence of chromatin modifiers on transcription. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:303–309. doi: 10.1038/ng1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugui JA, Pardo J, Chang YC, Müllbacher A, Zarember KA, Galvez EM, Brinster L, Zerfas P, Gallin JI, Simon MM, Kwon-Chung KJ. Role of laeA in the regulation of alb1, gliP, conidial morphology, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6:1552–1561. doi: 10.1128/EC.00140-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugui JA, Pardo J, Chang YC, Zarember KA, Nardone G, Galvez EM, Mullbacher A, Gallin JI, Simon MM, Kwon-Chung KJ. Gliotoxin is a virulence factor of Aspergillus fumigatus: gliP deletion attenuates virulence in mice immunosuppressed with hydrocortisone. Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6:1562–1569. doi: 10.1128/EC.00141-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribus M, Galehr J, Trojer P, Brosch G, Loidl P, Marx F, Haas H, Graessle S. HdaA, a major class 2 histone deacetylase of Aspergillus nidulans, affects growth under conditions of oxidative stress. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4:1736–1745. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.10.1736-1745.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojer P, Brandtner EM, Brosch G, Loidl P, Galehr J, Linzmaier R, Haas H, Mair K, Tribus M, Graessle S. Histone deacetylases in fungi: novel members, new facts. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:3971–3981. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM. Defining an epigenetic code. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:2–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb0107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Kurdistani S, Grunstein M. Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science. 2002;298:1412–1414. doi: 10.1126/science.1077790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RB, Henrikson JC, Hoover AR, Lee AE. Epigenetic remodeling of the fungal secondary metabolome. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry. 2008;6:1895–1897. doi: 10.1039/b804701d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Nguyen CK, Romans A, Kontoyiannis DP, May GS. Isogenic auxotrophic mutant strains in the Aspergillus fumigatus genome reference strain AF293. Archives of Microbiology. 2004;182:346–353. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0707-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.