Abstract

Context

Lead, mercury, and arsenic have been detected in a substantial proportion of Indian-manufactured traditional Ayurvedic medicines. Metals may be present due to the practice of rasa shastra (combining herbs with metals, minerals, and gems). Whether toxic metals are present in both US- and Indian-manufactured Ayurvedic medicines is unknown.

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of Ayurvedic medicines available via the Internet containing detectable lead, mercury, or arsenic and to compare the prevalence of toxic metals in US- vs Indian-manufactured medicines and between rasa shastra and non–rasa shastra medicines.

Design

A search using 5 Internet search engines and the search terms Ayurveda and Ayurvedic medicine identified 25 Web sites offering traditional Ayurvedic herbs, formulas, or ingredients commonly used in Ayurveda, indicated for oral use, and available for sale. From 673 identified products, 230 Ayurvedic medicines were randomly selected for purchase in August–October 2005. Country of manufacturer/Web site supplier, rasa shastra status, and claims of Good Manufacturing Practices were recorded. Metal concentrations were measured using x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy.

Main Outcome Measures

Prevalence of medicines with detectable toxic metals in the entire sample and stratified by country of manufacture and rasa shastra status.

Results

One hundred ninety-three of the 230 requested medicines were received and analyzed. The prevalence of metal-containing products was 20.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.2%–27.1%). The prevalence of metals in US-manufactured products was 21.7% (95% CI, 14.6%–30.4%) compared with 19.5% (95% CI, 11.3%–30.1%) in Indian products (P=.86). Rasa shastra compared with non–rasa shastra medicines had a greater prevalence of metals (40.6% vs 17.1%; P=.007) and higher median concentrations of lead (11.5 μg/g vs 7.0 μg/g; P=.03) and mercury (20 800 μg/g vs 34.5 μg/g; P=.04). Among the metal-containing products, 95% were sold by US Web sites and 75% claimed Good Manufacturing Practices. All metal-containing products exceeded 1 or more standards for acceptable daily intake of toxic metals.

Conclusion

One-fifth of both US-manufactured and Indian-manufactured Ayurvedic medicines purchased via the Internet contain detectable lead, mercury, or arsenic.

Ayurveda is a traditional medical system used by a majority of India’s 1.1 billion population.1 Ayurveda is also used worldwide by the South Asian diaspora and others.1 However, since 1978 more than 80 cases of lead poisoning associated with Ayurvedic medicine use have been reported worldwide.2,3 Ayurvedic medicines are divided into 2 major types: herbal-only and rasa shastra. Rasa shastra is an ancient practice of deliberately combining herbs with metals (eg, mercury, lead, iron, zinc), minerals (eg, mica), and gems (eg, pearl).4,5 Rasa shastra experts claim that these medicines, if properly prepared and administered, are safe and therapeutic.4,5 Of 70 Ayurvedic medicines manufactured in South Asia and sold in Boston, Massachusetts, stores in 2003, we found that 20% contained lead, mercury, and/or arsenic.6 Estimated daily lead, mercury, and arsenic intakes for these products were all higher than regulatory limits. We identified several rasa shastra medicines that could cause lead and mercury ingestions exceeding US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) limits by 3 to 4 orders of magnitude. Similar results have been found in other North American cities.7–10

The prevalence of metals in Ayurvedic medicines sold via the Internet and in those manufactured in the United States is unknown. Whether rasa shastra medicines account for most Ayurvedic medicines containing metals and whether they are manufactured by US companies or widely available to US consumers is also unknown.

Thus, this investigation was designed with 3 major objectives: (1) to determine the prevalence of Ayurvedic medicines available via the Internet containing detectable lead, mercury, or arsenic; (2) to compare the prevalence of toxic metals between US-and Indian-manufactured products; and (3) to compare the prevalence of toxic metals in rasa shastra vs non–rasa shastra medicines. We also compared the daily amounts of lead, mercury, and arsenic that would be ingested by persons taking these products according to packaging recommendations with acceptable metal consumption limits suggested by government, industry, and the World Health Organization.

METHODS

Selection of Ayurvedic Medicines

To select Internet-available Ayurvedic medicines for analysis, a strategy used by Morris and Avorn was adapted.11 An Internet search was conducted in November–December 2004 using 5 search engines (Google, Yahoo, AOL, MSN, and Ask Jeeves) and the key words Ayurveda and Ayurvedic medicine. Web sites listed on the first page of results from each search engine were reviewed and all products that met the following inclusion criteria identified: (1) traditional Ayurvedic herbs, formulas, or containing ingredients commonly used in Ayurveda; (2) indicated for oral use; and (3) available for sale. The 673 identified products were entered in a database and a computer-generated random number sequence was used to select 230 products for purchase. Presuming equal numbers of US-and Indian-manufactured products, this sample size provided 90% power to demonstrate a 10% difference in metal prevalence (α =.05). Products were ordered online during August–October 2005. Web site suppliers were not informed of the reason for our purchase.

Data Collection

We recorded the name of each medicine, its manufacturer, and the Web site supplier selling the product. Country of manufacture was defined as the country where the product was formulated (eg, made into a capsule or tablet) and packaged for sale. The country of the Web site supplier was determined from the contact information provided on the Web site. We also recorded formulation, indications, dosage(s), and cost. An Indian-trained Ayurvedic physician (A.S.) classified medicines as rasa shastra if they contained metals, minerals, or gems traditionally used according to 2 classic texts.4,5 Manufacturers claiming Good Manufacturing Practices or metal testing were noted. We determined whether US manufacturers were members of the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), a trade organization committed to “high-quality herbal products” and “promotion of self-regulation”12 from membership lists available on the association’s Web site. For Indian manufacturers, membership in the Ayurveda Drug Manufacturers’ Association (ADMA), committed to “standards and quality amongst its members,”13 was similarly noted. We asked US manufacturers anonymously by telephone where the herbs used for their products were grown. We presumed that herbs used by Indian manufacturers were grown in India. Classification of medicines by these characteristics was done without knowledge of the medicines’ metal content.

Products were transferred to plastic vials (Tri-State Distribution, Sparta, Tennessee) with anonymous unique identifiers and transported to the New England Regional EPA laboratory without interruption in chain of custody. From March to October 2006, samples were analyzed in duplicate for lead, mercury, and arsenic concentrations using x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy as previously described.6 The minimum lead, mercury, and arsenic concentrations that could be detected in the medicines with x-ray fluorescence were 5 μg/g, 20 μg/g, and 10 μg/g, respectively. Analysts were blinded to the medicines’ rasa shastra status, country of origin, and manufacturer characteristics. Standard reference materials were analyzed alongside the products as positive and negative controls.

Data Analysis

Product characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. The ratio of products with detectable lead, mercury, and/or arsenic to the number of products analyzed defined the prevalence of metal-containing Ayurvedic medicines in the sample. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated using the exact binomial distribution. Products were stratified by country of manufacture and the metal prevalences of US- and Indian-manufactured products were compared using the Fisher exact test. Reported metal concentrations are the means of the 2 determinations. In duplicate analysis of 4 products, one lead measurement was below the detection limit of 5 μg/g and the other was at or slightly above the limit; for each of these products the reported lead concentration is the mean of the latter measurement and 0. Median metal concentrations in US- and Indian-manufactured metal-containing products were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Similar analyses to compare metal prevalence and concentrations between rasa shastra and non–rasa shastra medicines were performed. The Fisher exact test was used to compare characteristics of metal- and non–metal-containing products such as the country of manufacture and Web site supplier, rasa shastra status, manufacturer membership in AHPA and ADMA, Good Manufacturing Practices claims, formulation, herb source, cost, and indication. All analyses were 2-tailed, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Product metal concentration, unit dose weight, and labeled recommended dosage(s)were used to calculate the amounts of lead, mercury, and arsenic that would be ingested on a daily basis if the product was taken as suggested by the manufacturer. These estimates were compared with established acceptable daily limits for metal ingestion. The California Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act (California Proposition 65) has established maximum allowable dose levels for chemicals causing reproductive toxicity (for lead, 0.5 μg/d).14 The American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/National Sanitation Foundation (NSF) International Dietary Supplement Standard 173 is a standard developed by NSF International, a US-based independent, non-profit, nongovernmental organization, and adopted by ANSI. ANSI 173 provides guidelines to the dietary supplement industry on methods to test and evaluate products, including accuracy of labeling and the presence of specific undeclared contaminants such as toxic metals. ANSI 173 states that dietary supplements should not contain undeclared metals that would cause intakes greater than 20μg/d of lead, 20 μg/d of mercury, and 10 μg/d of arsenic.15 The EPA has established daily reference doses of 21μg/d of inorganic mercury and 21 μg/d of inorganic arsenic for a 70-kg adult.16 The Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives establishes provisional tolerable weekly intakes for contaminants in foods of 25μg/kg of lead, 1.6μg/kg of mercury, and 15 μg/kg of arsenic, corresponding to acceptable daily intakes of 250 μg/d of lead, 50 μg/d of mercury, and 150 μg/d of arsenic for a 70-kg adult.17

SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board exempted the study from human subjects review.

RESULTS

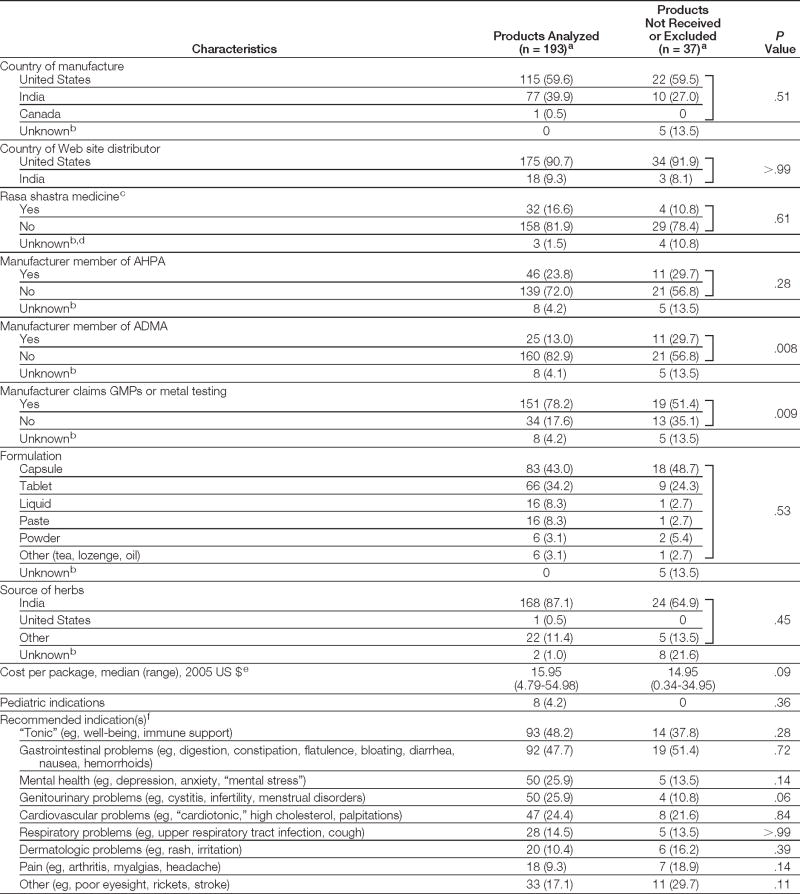

The Internet search identified 25 Web sites featuring 673 Ayurvedic medicines. Of 230 products randomly selected for purchase, we received and analyzed 193 (84%) made by 37 different manufacturers. Reasons for failure to fill our orders included the following: 21 products were no longer available or out of stock; 1 supplier refused to fill our order of 14 products after recognizing that we were authors of a previous study of Ayurvedic medicines6; 1 product received was a duplicate; and 1 product was excluded from study because it was for topical use only. Analyzed and unavailable products did not differ significantly for most characteristics assessed (Table 1).

Table 1.

General Characteristics of 230 Ayurvedic Medicines Randomly Selected for Purchase

|

Abbreviations: ADMA, India-based Ayurveda Drug Manufacturers’ Association; AHPA, US-based American Herbal Products Association; GMPs, Good Manufacturing Practices.

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Not included in statistical comparison between products tested and products not received or excluded.

Rasa shastra medicines are elaborately prepared compounds combining herbs with metals, minerals, and gems. An Indian-trained Ayurvedic physician (A.S.) classified medicines as rasa shastra if they contained metals, minerals, or gems traditionally used according to 2 classic rasa shastra texts.4,5

Rasa shastra status could not be determined because of a product with a proprietary name and an incomplete or absent listing of ingredients on the label and Web site.

One package would typically provide a 1-month supply of medicine if taken as directed.

Ayurvedic medicines often had multiple indications.

Overall, the prevalence of Ayurvedic medicines containing detectable lead, mercury, and/or arsenic was 20.7% (Table 2). Lead was the most commonly found metal, followed by mercury and arsenic. The prevalence of metal-containing products did not differ significantly between US- and Indian-manufactured products. The median lead concentration in Indian-manufactured vs US-manufactured lead-containing products was similar. Mercury was present in greater concentrations in Indian-manufactured products. Rasa shastra compared with non–rasa shastra medicines were more than twice as likely to contain metals. Rasa shastra metal-containing medicines had higher lead and mercury median concentrations than non–rasa shastra metal-containing medicines.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Median Concentrations of Lead, Mercury, and Arsenic in Ayurvedic Medicinesa

| All Products (n = 193) | US-Manufactured Products (n = 115) | Indian-Manufactured Products (n = 77) | P Valueb | Rasa Shastra Medicines (n = 32) | Non–Rasa Shastra Medicines (n = 158) | P Valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence, % (95% CI) Lead, mercury, or arsenic |

20.7 (15.2–27.1) | 21.7 (14.6–30.4) | 19.5 (11.3–30.1) | .86 | 40.6 (23.7–59.4) | 17.1 (11.6–23.9) | .007 |

| Lead | 19.2 (13.9–25.4) | 20.9 (13.9–29.4) | 16.9 (9.3–27.1) | .58 | 40.6 (23.7–59.4) | 15.2 (10.0–21.8) | .002 |

| Mercury | 4.1 (1.8–8.0) | 2.6 (0.5–7.4) | 6.5 (2.1–14.5) | .27 | 9.4 (2.0–25.0) | 3.2 (1.0–7.2) | .13 |

| Arsenic | 1.6 (0.3–4.5) | 2.6 (0.5–7.4) | 0 | .28 | 3.1 (0.1–16.2) | 1.3 (0.2–4.5) | .43 |

| Concentration, median (range), μg/g Lead |

7.5 (2.5–25 950) | 7.5 (3.0–20.5) | 11.0 (2.5–25 950) | .31 | 11.5 (2.5–25 950) | 7.0 (3.0–20.5) | .03 |

| Mercury | 103.8 (24.5–28 200) | 25.5 (24.5–34.5) | 13 050 (47.5–28 200) | .04 | 20 800 (13 050–28 200) | 34.5 (24.5–160) | .04 |

| Arsenic | 27.0 (10.5–27.5) | 27.0 (10.5–27.5) | 27.5 | 18.8 (10.5–27.0) | .54 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

The median metal concentration presented is for medicines with detectable amounts of the respective metal.

Comparison between US- and Indian-manufactured products.

Comparison between rasa shastra and non–rasa shastra medicines.

The Ayurvedic medicines with detectable metals and their manufacturers, Web site suppliers, rasa shastra status, and metal concentrations are summarized in Table 3. Ayurvedic medicines manufactured in the United States contained primarily lead at concentrations below 25 μg/g, whereas Indian-manufactured medicines contained both lead and mercury at concentrations that reached 104 μg/g. Rasa shastra medicines were more likely to be manufactured in India. Agnitundi Bati, Ekangvir Ras, and Arogyavardhini Bati were Indian-manufactured rasa shastra medicines distributed by US Web sites with extremely elevated lead and mercury concentrations. In contrast, US-manufactured rasa shastra medicines did not contain detectable mercury and had lower lead concentrations than those manufactured in India.

Table 3.

Ayurvedic Medicines Containing Detectable Lead, Mercury, or Arsenic

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Web Site Supplier (Country) | Rasa Shastra Medicine | Metal Concentration, μg/ga | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | Mercury | Arsenic | ||||

| US-Manufactured Ayurvedic Medicines | ||||||

| Prana–Breath of Life | Ayurherbal Corporation | By the Planet (USA) | 9.0 | 24.5 | ND | |

| AyurRelief | Balance Ayurvedic Productsb | Balance Ayurvedic Products (USA) | 5.5 | ND | ND | |

| GlucoRite | Balance Ayurvedic Productsb | Balance Ayurvedic Products (USA) | 6.0 | ND | ND | |

| Mahasudarshan | Banyan Botanicalsb,c | The Ayurvedic Institute (USA)c | 8.5 | ND | ND | |

| Kanchanar Guggulu | Banyan Botanicalsb,c | Banyan Botanicals (USA)b,c | 7.5 | ND | ND | |

| Shilajit | Banyan Botanicalsb,c | Banyan Botanicals (USA)b,c | X | 10.5 | ND | ND |

| Acnenil | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 3.0 | ND | ND | |

| Energize | Bazaar of Indiab | Bazaar of India (USA) | X | 8.5 | ND | ND |

| Hingwastikad | Bazaar of Indiab | Herbal Remedies USA (USA) | ND | 34.5 | ND | |

| Bakuchi | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 3.0 | ND | ND | |

| Brahmi | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 6.5 | ND | ND | |

| Chairata | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 6 | ND | ND | |

| Cold Aid | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 5.5 | ND | ND | |

| Trifala Guggulu | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 20.5 | 25.5 | 27.0 | |

| Heart Plus | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 7.5 | ND | ND | |

| Jatamansi | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 12.0 | ND | ND | |

| Kanta Kari | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 20.5 | ND | ND | |

| Licorice | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 5.5 | ND | ND | |

| Praval Pisti | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | X | 7.5 | ND | 27.5 |

| Prostate Rejuv | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | X | 11.5 | ND | ND |

| Sugar Fight | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 7.5 | ND | ND | |

| Tagar | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 12.0 | ND | ND | |

| Yograj Guggulu | Bazaar of Indiab | By the Planet (USA) | 17.5 | ND | 10.5 | |

| Lean Plus | Tattva’s Herbsb | Tattva’s Herbs (USA) | 6 | ND | ND | |

| Neem Plus | Tattva’s Herbsb | Tattva’s Herbs (USA) | 10.5 | ND | ND | |

| Indian-Manufactured Ayurvedic Medicines | ||||||

| Commiphora Mukul | Unknown | National Institute of Ayurvedic Medicine (USA) | ND | 47.5 | ND | |

| Bacopa Monniera | Unknown | National Institute of Ayurvedic Medicine (USA) | 6.0 | ND | ND | |

| Yogaraj Guggulu | Unknown | National Institute of Ayurvedic Medicine (USA) | ND | 160 | ND | |

| Ezi Slim | Goodcare Pharma | AllAyurveda.com (India) | 3.0 | ND | ND | |

| Ekangvir Ras | Baidyanathe | Bdbazar (USA) | X | 25 950 | 20 800 | ND |

| Agnitundi Bati | Baidyanathe | Bdbazar (USA) | X | 130 | 28 200 | ND |

| Brahmi | Baidyanathe | AllAyurveda.com (India) | 6.0 | ND | ND | |

| Amoebica | Baidyanathe | Bdbazar (USA) | 11.0 | ND | ND | |

| Arogyavardhini Bati | Baidyanathe | Bdbazar (USA) | X | 125 | 13 050 | ND |

| Vital Lady | Maharishi Ayurvedab | Maharishi Ayurveda USA (USA) | X | 5.5 | ND | ND |

| Worry Freed | Maharishi Ayurvedab | Maharishi Ayurveda USA (USA) | X | 7.0 | ND | ND |

| Ayu-Arthri-Tone | Sharangdhar Pharmaceuticals | AYU (USA) | X | 63 | ND | ND |

| Ayu-Hemoridi-Tone | Sharangdhar Pharmaceuticals | AYU (USA) | X | 2.5 | ND | ND |

| Ayu-Leuko-Tone | Sharangdhar Pharmaceuticals | AYU (USA) | X | 33 | ND | ND |

| Ayu-Nephro-Tone | Sharangdhar Pharmaceuticals | AYU (USA) | X | 340 | ND | ND |

Reported metal concentration is the mean of 2 measurements. If one measurement was below the detection limit and the other at or above the limit, the reported concentration is the mean of the latter measurement and 0. Measurements below x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy reporting levels (lead, ≥5 μg/g; mercury, ≥20 μg/g; arsenic, ≥10 μg/g) are expressed as not detectable (ND). A list of Ayurvedic medicines without detectable metals, their manufacturers, and their Web suppliers is available from the authors.

Manufacturer claims Good Manufacturing Practices or testing for metals.

US company is a member of the American Herbal Products Association.

Label specifically recommends pediatric use.

Indian company is a member of the Ayurveda Drug Manufacturers’ Association.

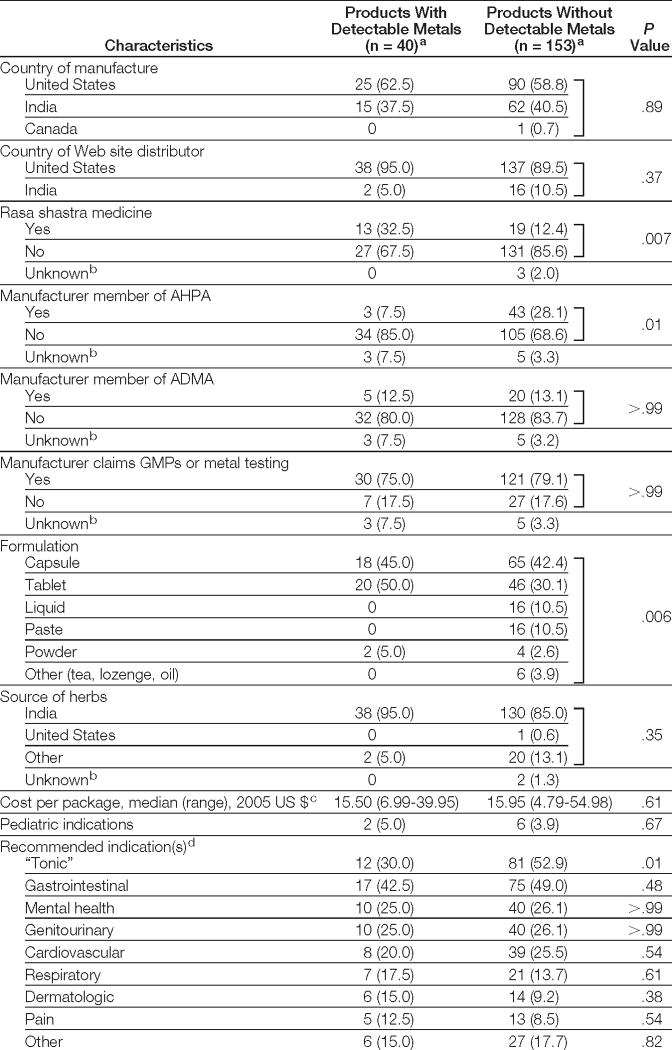

Characteristics of products with and without detectable metals are compared in Table 4. Country of manufacture and Web site distributor did not significantly differ. Manufacturers of 75% of the metal-containing products claimed Good Manufacturing Practices or metal testing, and these claims were not associated with a lower prevalence of toxic metals. Membership in ADMA was not associated with a lower likelihood of metal presence compared with nonmembership. Products made by AHPA members compared with nonmembers were less likely to contain metals. Products containing metals were more likely to be tablets and less likely to be liquids or pastes.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Ayurvedic Medicines With and Without Detectable Metals

|

Abbreviations: ADMA, India-based Ayurveda Drug Manufacturers’ Association; AHPA, US-based American Herbal Products Association; GMPs, Good Manufacturing Practices.

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Not included in statistical comparison between products with and without detectable metals.

One package would typically provide a 1-month supply of medicine if taken as directed.

Ayurvedic medicines often have multiple indications. See Table 1 for examples of indications.

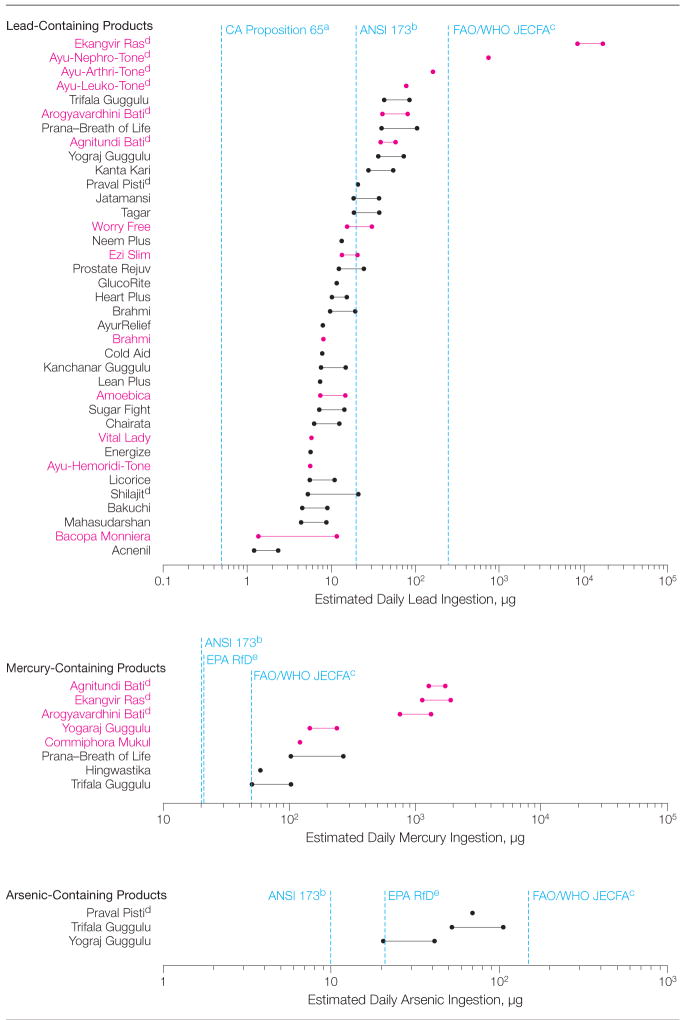

The Figure shows the daily amounts of lead, mercury, and arsenic that would be ingested if metal-containing medicines were taken according to manufacturers’ recommendations. Various regulatory standards for maximum daily metal intakes are presented for comparison. All metal-containing products would cause ingestions exceeding at least 1 regulatory standard. Indian-manufactured rasa shastra medicines would cause the greatest lead and mercury ingestions, often substantially exceeding all standards.

Figure.

Estimated Daily Ingestion Amounts of Lead, Mercury, and Arsenic for Metal-Containing Ayurvedic Medicines

Estimated daily ingestion levels for the respective metal-containing Ayurvedic medicines were calculated using the mean metal concentration in the product, unit dose weight, and recommended dosage(s) stated on the label. If the manufacturer recommended a range of dosages, a range of potential daily ingestion amounts is shown. India- and US-made products are shown in red and black, respectively.

aCalifornia Proposition 65 has established a maximum allowable dose level for lead of 0.5 μg/d.14 bAmerican National Standards Institute/National Sanitation Foundation International Dietary Supplement Standard 173 (ANSI 173) states that dietary supplements should not contain undeclared metals that would cause intakes greater than 20 μg/d of lead, 20 μg/d of mercury, and 10 μg/d of arsenic.15 cFood and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (FAO/WHO JECFA) provisional tolerable weekly intakes correspond to acceptable intakes of 250 μg/d of lead, 50 μg/d of mercury, and 150 μg/d of arsenic for a 70-kg person.17 dRasa shastra medicine.e United States Environmental Protection Agency reference doses (EPARfDs) for chronic oral intake of mercuric chloride and arsenic are both 0.3 μg/kg/d, corresponding to 21 μg/d for a 70-kg adult.16

COMMENT

In a random sample of commercially prepared Ayurvedic medicines purchased via the Internet, we found that nearly 21% contained detectable levels of lead, mercury, and/or arsenic, and the prevalence of these potentially toxic metals did not differ by country of manufacture; ie, United States vs India. Rasa shastra medicines were more than twice as likely as non–rasa shastra products to contain detectable metals. All metal-containing products exceeded 1 or more standards for acceptable daily metal intake. Several Indian-manufactured rasa shastra medicines could result in lead and/or mercury ingestions 100 to 10 000 times greater than acceptable limits.

Metals identified in our sample of Ayurvedic medicines are likely a result of the practice of rasa shastra or contamination. Many rasa shastra medicines are made with bhasmas, which are elaborately prepared with various forms of metals including cinnabar (mercuric sulfide), galena (lead sulfide), realgar (arsenic sulfide), and white arsenic (arsenic trioxide).4,5 Ekangvir Ras is an example of a rasa shastra medicine made with naga (lead) bhasma and parada (mercury). Ayurveda experts in India believe that if bhasmas are properly prepared according to ancient protocols, the metals undergo shodhana (“purification”), rendering them nontoxic and therapeutic. Case reports in the literature, however, have documented significant toxicity with the use of some of these products.2,3 The prevalence of metals in non–rasa shastra medicines was still substantial (17%) and could be a consequence of environmental contamination of the herbs18 or incidental contamination during manufacturing.

Our finding that close to 21% of Ayurvedic medicines manufactured and distributed by US and Indian companies via the Internet contain lead, mercury, or arsenic is consistent with our previous report that 20% of Indian-manufactured Ayurvedic medicines purchased in South Asian ethnic markets in Boston contain these metals.6 However, the Ayurvedic medicines analyzed in the Boston study had higher median metal concentrations (lead, 40 μg/g; mercury, 20 225 μg/g; and arsenic, 430 μg/g) and were more often recommended for pediatric use (50% vs 5%) than the medicines analyzed in our Internet sample. Studies of Ayurvedic medicines purchased from stores in New York,7 Houston,8 Chicago,9 and Canada10 have also reported similar findings, and lead has been found in non-Ayurvedic herbal and vitamin supplements manufactured in the United States19,20 as well as in traditional medicines from other cultures.21,22

The public health impact of metals in rasa shastra and contaminated herbal medicines in India is unknown and controversial.23 Ayurveda advocates in India maintain that rasa shastra medicines have been used effectively and safely for millennia.4,5,23 They ascribe case reports of metal toxicity to improper commercial manufacturing practices or lack of supervision from a practitioner skilled in rasa shastra.23 However, many Ayurvedic medicine users believed to be unaffected may actually have unrecognized, misdiagnosed, or subclinical metal intoxications. Patients with Ayurvedic medicine–associated lead poisoning commonly undergo endoscopy for abdominal symptoms or bone marrow biopsy for anemia before they receive a correct diagnosis.24 Given widespread use of Ayurvedic medicines in India and throughout the world, observational studies assessing whether rasa shastra and non–rasa shastra medicine use are independent risk factors for increased lead burden are urgently needed.

Limitations of our study include potential misclassification of the product’s country of manufacture and rasa shastra status. Information provided by the Web site, label, and/or manufacturer was occasionally contradictory or ambiguous. However, this limitation does not affect the overall prevalence of metals in the sampled medicines, and any misclassification would have been nondifferential. Unobtainable products were not random and may have had a higher or lower likelihood of containing metals, thus potentially affecting the overall sample prevalence. We did not assess batch-to-batch variability in metal concentrations. However, this would likely not significantly alter overall prevalence estimates. Wide variation among published standards for acceptable limits of daily metal ingestion makes it difficult to assess the magnitude of potential toxicity for different products. Finally, we did not ascertain the specific physical form or chemical species of the metals. To the best of our knowledge, the physico-chemical form of metals in rasa shastra medicines and their bioavailability have not been fully characterized or reported. We are unaware of rigorous evidence supporting claims that bhasmas made using lead, mercury, and arsenic are nontoxic, and documented case reports of poisonings2,3 contradict these theories.

Regarding generalizability, products in our study can be purchased via the Internet without consultation from an Ayurvedic practitioner. Thus, our results may not reflect products recommended or provided by individual Ayurvedic practitioners to patients in the context of a patient-practitioner consultation.25 Compared with Ayurvedic practitioners in India, US practitioners are reportedly less likely to use rasa shastra medicines.25 Rasa shastra is not included in the scope of practice being developed by the US-based National Ayurvedic Medical Association, a professional organization for US-and Indian-trained Ayurvedic practitioners (Jennifer Rioux, PhD, personal communication, 2008). Internet products may also not be similar to those sold over the counter in mainstream US pharmacies and health food stores.

Despite these limitations, our data likely provide a relatively accurate snapshot of the prevalence of metal-containing Ayurvedic medicines sold via the Internet in 2005. A 2005 Institute of Medicine report concluded that “the regulatory mechanisms for monitoring the safety of dietary supplements... [should] be revised. The constraints imposed on FDA [US Food and Drug Administration] with regard to ensuring the absence of unreasonable risk associated with the use of dietary supplements make it difficult for the health of the American public to be adequately protected.”26 A 2006 National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference similarly stated that “public assurance of the safety and quality of [dietary supplements] is inadequate.”27 Our data demonstrating elevated levels of lead, mercury, and arsenic in publicly available Ayurvedic medicines and prior studies finding toxic metals in non-Ayurvedic supplements19–22 support these conclusions. New FDA regulations28,29 and current Indian policies23,30 do not specify any maximum acceptable concentrations or daily dose limits for metals in dietary supplements for domestic use. We suggest strictly enforced, government-mandated daily dose limits for toxic metals in all dietary supplements and requirements that all manufacturers demonstrate compliance through independent third-party testing.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Saper is supported by a Career Development Award (K07 AT002915-03) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), National Institutes of Health. Dr Phillips is supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award (5K24AT000589-07) from NCCAM.

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge Jennifer Rioux, PhD (University of North Carolina Department of Anthropology), Larry Culpepper, MD, MPH (Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center), and Karen Freund, MD, MPH (Department of Medicine, Boston Medical Center), for helpful reviews of earlier versions of the manuscript, for which they were not compensated. We also thank Florence Uzogara, MA, and Surya Karri, MBBS, MPH (Boston Medical Center, compensated by Department of Family Medicine funds), for research assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, NCCAM, EPA, CDC, or National Referral Centre for Lead Poisoning in India.

Author Contributions: Dr Saper had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Saper, Kales.

Acquisition of data: Saper, Khouri, Paquin, Thuppil.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Saper, Phillips, Sehgal, Davis, Kales.

Drafting of the manuscript: Saper.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Saper, Phillips, Sehgal, Khouri, Davis, Paquin, Thuppil, Kales.

Statistical analysis: Saper, Davis.

Obtained funding: Saper.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Saper, Khouri, Kales.

Study supervision: Saper, Phillips.

Financial Disclosures: In 2004, prior to the beginning of this study, Dr Sehgal was employed for 1 year as a research associate by Arya Vaidya Pharmacy, an Indian-based Ayurvedic medicine manufacturer. No products from Arya Vaidya Pharmacy were analyzed in this study. No other disclosures were reported.

Role of the Sponsor: The Centers for Disease Control Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (CDC CLPPP) was provided with a list of Ayurvedic medicines to purchase for the study. The CDC CLPPP ordered the medicines with its funds. The CDC CLPPP also provided funds to the New England Regional EPA Laboratory to defray the cost of analyzing the medicines. Otherwise, the CDC LPPP and NCCAM had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for submission.

References

- 1.Gogtay NJ, Bhatt HA, Dalvi SS, Kshirsagar NA. The use and safety of non-allopathic Indian medicines. Drug Saf. 2002;25(14):1005–1019. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst E. Heavy metals in traditional Indian remedies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;57(12):891–896. doi: 10.1007/s00228-001-0400-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead poisoning associated with use of Ayurvedic medications—five states, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(26):582–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satpute AD. Rasa Ratna Samuchaya of Vagbhatta. Varanasi, India: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishtana; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shastri K. Rasa Tarangini of Sadananda Sharma. New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidas; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saper RB, Kales SN, Paquin J, et al. Heavy metal content of Ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2868–2873. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NYC health department warns against use of herbal medicine products made in India that contain lead or mercury [press release]. December 21, 2005. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr/pr124-05.shtml. Accessed March 21, 2008.

- 8.Houston department of health and human services detects lead, arsenic in seven South Asian traditional remedies [press release]. March 1, 2006. http://www.houstontx.gov/health/NewsReleases/Lead%20in%20Indian%20Remedies.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2008.

- 9.City health dept. warns of toxins in some South Asian medicines [press release]. July 26, 2005. http://egov.cityofchicago.org/city/webportal/portalContentItemAction.do?contentOID=536928660&contenTypeName=COC_EDITORIAL&topChannelName=Dept&channelId=0&entityName=Health&deptMainCategoryOID=-536887965&blockName=Health%2F2005%2FI+Want+To. Accessed February 8, 2008.

- 10.Health Canada warns consumers not to use certain Ayurvedic medicinal products [press release]. July 14, 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/_2005/2005_80_e.html. Accessed March 6, 2008.

- 11.Morris CA, Avorn J. Internet marketing of herbal products. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1505–1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Herbal Products Association. [Accessed March 21, 2008];AHPA Code of Ethics and Business Conduct. http://www.ahpa.org/Portals/0/pdfs/AHPA_CodeOfEthics.pdf.

- 13.Ayurveda Drug Manufacturers’ Association home page. http://www.admaindia.com/abtus.php. Accessed March 21, 2008.

- 14.Reproductive and Cancer Hazard Assessment Branch, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California Environmental Protection Agency. Proposition 65 safe harbor levels: no significant risk levels for carcinogens and maximum allowable dose levels for chemicals causing reproductive toxicity. January 2008. http://www.oehha.ca.gov/prop65/pdf/Feb2008StatusReport.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2008.

- 15.NSF International Standard/American National Standard #173 for Dietary Supplements. Ann Arbor, MI: NSF International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). http://www.epa.gov/iris. Accessed April 14, 2008.

- 17.Codex General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Foods. http://www.codexalimentarius.net/download/standards/17/CXS_193e.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2008.

- 18.Dwivedi SK, Dey S. Medicinal herbs: a potential source of toxic metal exposure for man and animals in India. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57(3):229–231. doi: 10.1080/00039890209602941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raman P, Patino LC, Nair MG. Evaluation of metal and microbial contamination in botanical supplements. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(26):7822–7827. doi: 10.1021/jf049150+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan SP, Nortrup DA, Bolger PM, Capar SG. Analysis of dietary supplements for arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(5):1307–1312. doi: 10.1021/jf026055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko RJ. Adulterants in Asian patent medicines. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(12):847. doi: 10.1056/nejm199809173391214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baer RD, Ackerman A. Toxic Mexican folk remedies for the treatment of empacho: the case of azarcon, greta and albayalde. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;24(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramachandran R. For better regulation. [Accessed April 14, 2008];Frontline. 2006 23(2) http://www.flonnet.com/fl2302/stories/20060210002004500.htm.

- 24.Kales SN, Christophi CA, Saper RB. Hematopoietic toxicity from lead-containing Ayurvedic medications. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(7):CR295–CR298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rioux J. Design and interpretation of data in “Heavy metal content of Ayurvedic medicine products” published in JAMA by Saper et al. Light Ayurveda J Health. 2005;3(4):24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Supplements: A Framework for Evaluating Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Panel. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: multivitamin/mineral supplements and chronic disease prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(5):364–371. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-5-200609050-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Issues dietary supplements final rule [press release]. June 22, 2007. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/news/2007/new01657.html. Accessed March 18, 2008.

- 29.Current Good Manufacturing Practice in manufacturing, packaging, labeling, or holding operations for dietary supplements; final rule. [Accessed March 18, 2008];Federal Register. 2007 June 25;34:838–34845. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~lrd/fr07625a.html. [PubMed]

- 30.Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homoeopathy. F. No. K-11020/5/97-DCC. October 14, 2005. http://indianmedicine.nic.in/html/acts/Orders_%20D&C_%20Act.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2008.