Abstract

We have developed a novel structure-based approach to search for Complimentary Ligands Based on Receptor Information (CoLiBRI). CoLiBRI is based on the representation of both receptor binding sites and their respective ligands in a space of universal chemical descriptors. The binding site atoms involved in the interaction with ligands are identified by the means of computational geometry technique known as Delaunay tessellation as applied to x-ray characterized ligand-receptor complexes. TAE/RECON1 multiple chemical descriptors are calculated independently for each ligand as well as for its active site atoms. The representation of both ligands and active sites using chemical descriptors allows the application of well-known chemometric techniques in order to correlate chemical similarities between active sites and their respective ligands. From these calculations, we have established a protocol to map patterns of nearest neighbor active site vectors in a multidimensional TAE/RECON space onto those of their complementary ligands, and vice versa. This protocol affords the prediction of a virtual complementary ligand vector in the ligand chemical space from the position of a known active site vector. This prediction is followed by chemical similarity calculations between this virtual ligand vector and those calculated for molecules in a chemical database to identify real compounds most similar to the virtual ligand. Consequently, the knowledge of the receptor active site structure affords straightforward and efficient identification of its complementary ligands in large databases of chemical compounds using rapid chemical similarity searches. Conversely, starting from the ligand chemical structure, one may identify possible complementary receptor cavities as well. We have applied the CoLiBRI approach to a dataset of 800 x-ray characterized ligand receptor complexes in the PDBbind database2. Using a k nearest neighbor (kNN) pattern recognition approach and variable selection, we have shown that knowledge of the active site structure affords identification of its complimentary ligand among the top 1% of a large chemical database in over 90% of all test active sites when a binding site of the same protein family was present in the training set. In the case where test receptors are highly dissimilar and not present among the receptor families in the training set, the prediction accuracy is decreased; however CoLiBRI was still able to quickly eliminate 75% of the chemical database as improbable ligands. The CoLiBRI approach provides an efficient prescreening tool for large chemical databases prior to traditional, yet much more computationally intensive, three-dimensional docking approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Computer Aided Drug Design (CADD) is frequently identified with two concurrent approaches: structure-based and ligand-based modeling. Structure-based methodologies employ either an experimentally (X-ray or NMR) determined or predicted three-dimensional structure of a target protein. This structure is used to scan available chemical databases or virtual combinatorial libraries for the identification of potential lead compounds, which are characterized by stereochemical complementarity to the active site and have a high predicted binding constant. The binding constant estimate requires a fast and accurate scoring function. Several successful studies have been reported in the literature using popular docking methods such as DOCK3–6 and AutoDock7;8. Typically, these approaches are capable of identifying a small number of compounds that can fit comfortably into the active site. Despite these success stories, accurate prediction of binding constants still represents a formidable task and is a focus of many ongoing investigations9.

Theoretically, the most accurate estimate of the free energy of binding can be obtained using energy based methods. These methods typically employ force fields originally developed for the refinement of experimentally-determined molecular structures or for molecular dynamics simulations. Examples include free energy perturbation (FEP)10;11 or Linear Interaction Energy (LIE) approaches12–14, which require significant computational resources. Application of continuum solvation models, instead of explicit solvent, can significantly reduce the cost of these calculations15. However, the computational cost of such methods is still too demanding to afford calculations in a high-throughput fashion, and therefore these calculations can only be practical if applied to either relatively simple systems or small sets of compounds with similar binding modes.

Ligand-based approaches rely on a series of ligands with known binding affinities to build correlations between ligand chemical structure and target properties of interest, such as binding constants or specific biological activities [see 16 for a recent review]. The ligand structures are typically represented by multiple chemical descriptors17, and statistical data modeling techniques are used to establish quantitative correlations between descriptors and binding affinities. Chemical descriptors and various chemical similarity measures (e.g., Euclidean distances between compounds in multidimensional descriptor space) are at the core of chemometric approaches to the analysis of molecular databases18. Such approaches afford rapid chemical similarity calculations and are widely used in database mining or rational library design to discover molecules similar to available compounds that are likely to have similar biological activity19. Chemical similarity searches are much more computationally efficient than structure based virtual screening. However, they are more likely to identify false positives that are too bulky or simply not stereochemically complementary to the actual binding site because the binding site information is not typically used as part of the query. Furthermore, chemometric approaches typically identify compounds that are highly similar to the training set compounds, making it difficult to identify novel ligands of a different structural class.

In this paper, we discuss a novel computational drug discovery strategy that combines the strengths of both structure-based and ligand-based approaches while attempting to surpass their individual shortcomings. To this end, we sought a representation that would allow us to characterize both receptor active sites and their corresponding ligands in the same universal, multidimensional, chemical descriptor space. We reasoned that mapping of both binding pockets and corresponding ligands onto the same multidimensional chemistry space would preserve the complementarity relationships between binding sites and their respective ligands. Thus, we expected that similar binding sites (where similarity is described quantitatively using one of the conventional metrics, such as Manhattan distance in multidimensional descriptor space) would correspond to similar ligands. This would imply that the relative location of a novel binding site in this chemistry space with respect to other binding sites could be used to predict the location of the ligand(s) complementary to this site in the ligand chemistry space. This virtual ligand(s) could then be used as a query in chemical similarity searches to identify putative ligands of the same receptor in available chemical databases.

To implement this strategy, we have used molecular descriptors based on Transferable Atom Equivalents (TAE) developed by Breneman and co-workers1;20;21. The major advantage of these descriptors over other descriptor types (discussed briefly in the next section) is that they are derived from the electronic and shape properties of isolated atoms or chemical groups. The additivity principle is used to calculate molecular descriptors by summing up the individual descriptor type values for all atoms in the molecule, using the RECON method. In the case of ligands, this leads to the generation of molecular descriptors, similar to other approaches. The same additivity principle can also be used to derive pseudo-molecular descriptors for any group of atoms, e.g., active site fragments, making the TAE descriptors exceptionally well suited for our approach.

In this paper, we report on the application of this chemometric structure based drug discovery strategy, termed CoLiBRI (identification of Complimentary Ligand Based on Receptor Information), to a training set of 800 diverse ligand-receptor complexes comprising the PDBBind dataset2. We show that the knowledge of the receptor active site affords the highly computationally efficient and accurate identification of its respective ligand(s) within a large compound database. The success of this pilot study indicates that the CoLiBRI method can become an efficient alternative to traditional structure based drug discovery approaches or used for rapid pre-screening and filtering most promising compounds prior to engaging more computationally intensive approaches.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODOLOGIES

Dataset

Coordinates for 800 chemically and functionally diverse ligand-receptor complexes were obtained from the PDBbind Database2 (PDB entry codes for these proteins are listed in the supplementary information). SYBYL v6.822 was used to pre-process the raw macromolecular structures, including elimination of the crystallographic water molecules, removal of salts, and addition of hydrogen atoms.

Chemical descriptors

Several important considerations went into finding the most capable descriptors in the context of our studies. There are two major classes of traditional chemical descriptors that are derived from either two-dimensional chemical graphs (e.g., molecular connectivity indices, charge descriptors, and others 23–29), or from three-dimensional molecular models using relative atomic positions in addition to atom properties. A major benefit of 2D compared to 3D chemometric methods is that the former neither requires a conformational search nor structural alignment of molecules. Accordingly, 2D methods are more easily automated and adapted to the task of database searching, or virtual screening30. In fact, 2D descriptors have been shown to be superior to 3D descriptors in database mining31. However, most 2D chemical descriptors are typically calculated from only complete molecular graphs. Consequently, they can not be used to characterize active sites that are composed of fragments or individual atoms of amino acid residues that are involved in specific contacts with ligands. A notable exception is the TAE descriptors, as discussed in the Introduction.

The TAE/RECON method that was developed by Breneman and co-workers is based on the Bader's quantum theory of atoms in molecules (AIM). The TAE method of molecular electron density reconstruction utilizes a library of integrated atomic “basins”, as defined by the AIM theory, to rapidly reconstruct representations of molecular electron density distributions and van der Waals electronic surface properties. RECON is capable of rapidly generating 6-31+G* level electron densities and electronic properties of large molecules, proteins or molecular databases, using TAE reconstruction. A library of atomic charge density fragments has been assembled in a form that allows for the rapid retrieval of the fragments, followed by rapid molecular assembly. Additional details of the method are described elsewhere 1;20;21.

Calculation of TAE/RECON descriptors for ligands and their binding sites

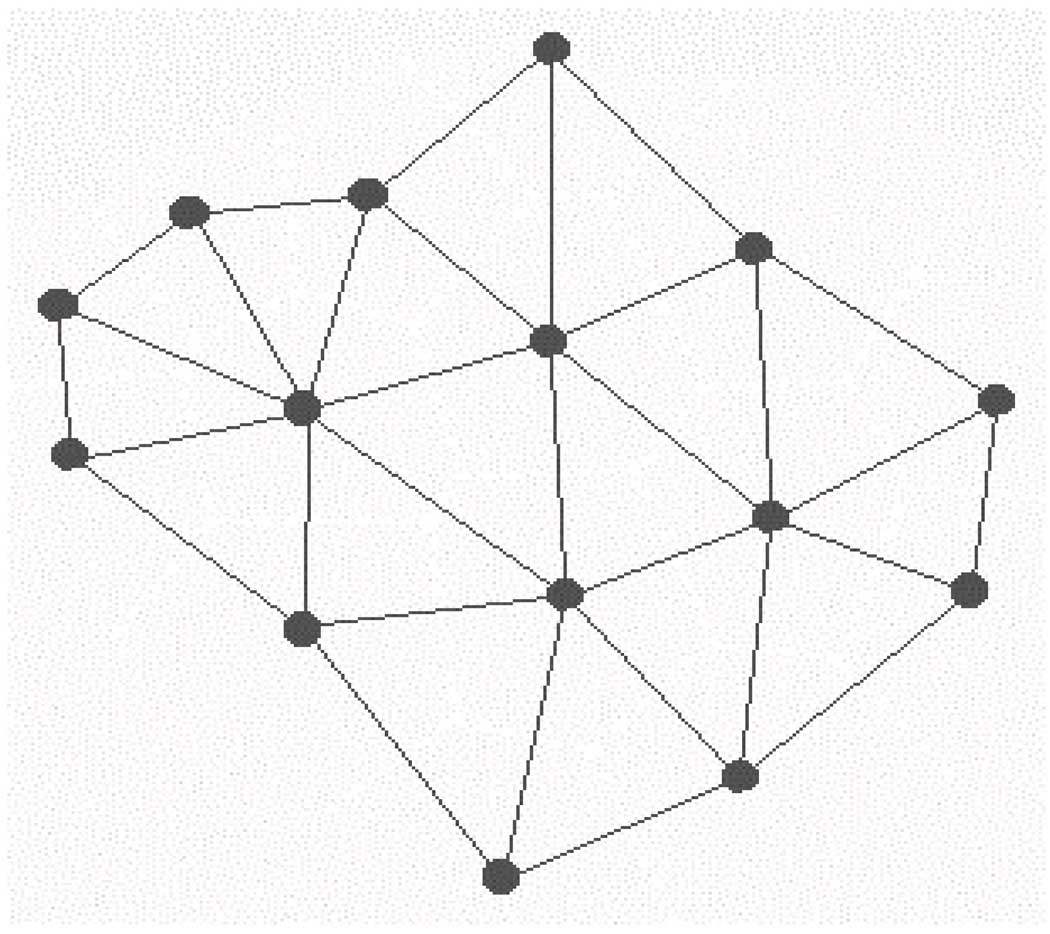

The calculation of TAE/RECON descriptors for the ligands (extracted from their protein complexes) was straightforward. However, similar calculations for the binding sites first required the identification of individual atoms or amino acid fragments involved in specific ligand-receptor interactions. To this end, we have utilized a computational geometry technique known as Delaunay tessellation to isolate the protein atoms that make contacts with bound ligands. Applied to a collection of randomly distributed points, Delaunay tessellation partitions the space occupied by these points into and aggregate of space filling, irregular triangles (in 2D) or tetrahedra (in 3D) with the original points as vertices. Thus, this approach effectively identifies all narest neighbor triplets (or quadruplets) of vertices. An example of Delaunay tessellation in two dimensions is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Delaunay tessellations of a collection of random points in 2D.

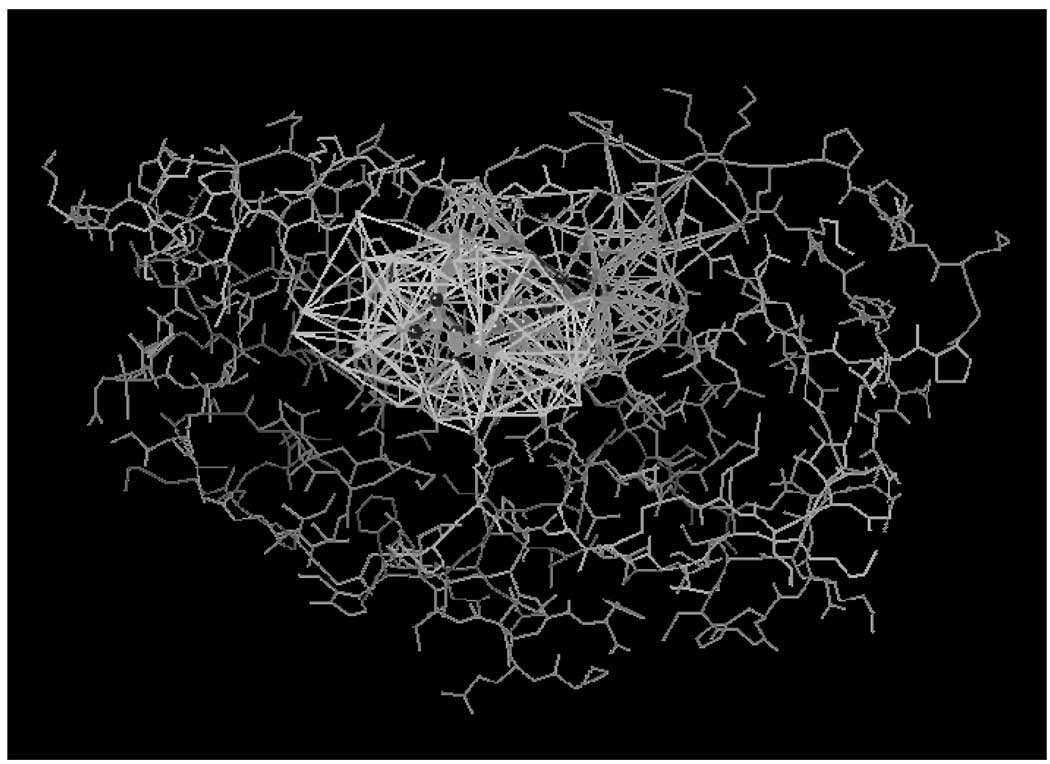

Protein-ligand complexes are represented by the coordinates of their heavy atoms (i.e., in a hydrogen-depleted form). Delaunay tessellation of this representation uniquely defines all sets of nearest neighbor atom quadruplets, including three types of interfacial quadruplets: three receptor atoms and one ligand atom; two receptor and two ligand atoms; and one receptor and three ligand atoms. Thus, Delaunay tessellation affords an easy way of detecting all receptor atoms that are nearest neighbors of the ligand atoms, which are specified as the active site. The RECON/TAE method is then used as described above to generate a set of descriptors for pseudo molecule constructed from the active site atoms. An example of tessellated ligand-receptor complex is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tessellation of ligand-receptor interface identifies all active site atoms that make contacts with ligand atoms.

The descriptors generated with TAE/RECON were range scaled prior to distance calculations (eq. 1).

| (1) |

We chose to scale descriptors so that their absolute ranges after scaling are the same. Had we used the real values, the value of the absolute distance between receptors or ligands would be biased by the descriptors that cover the largest ranges.

CoLiBRI algorithm

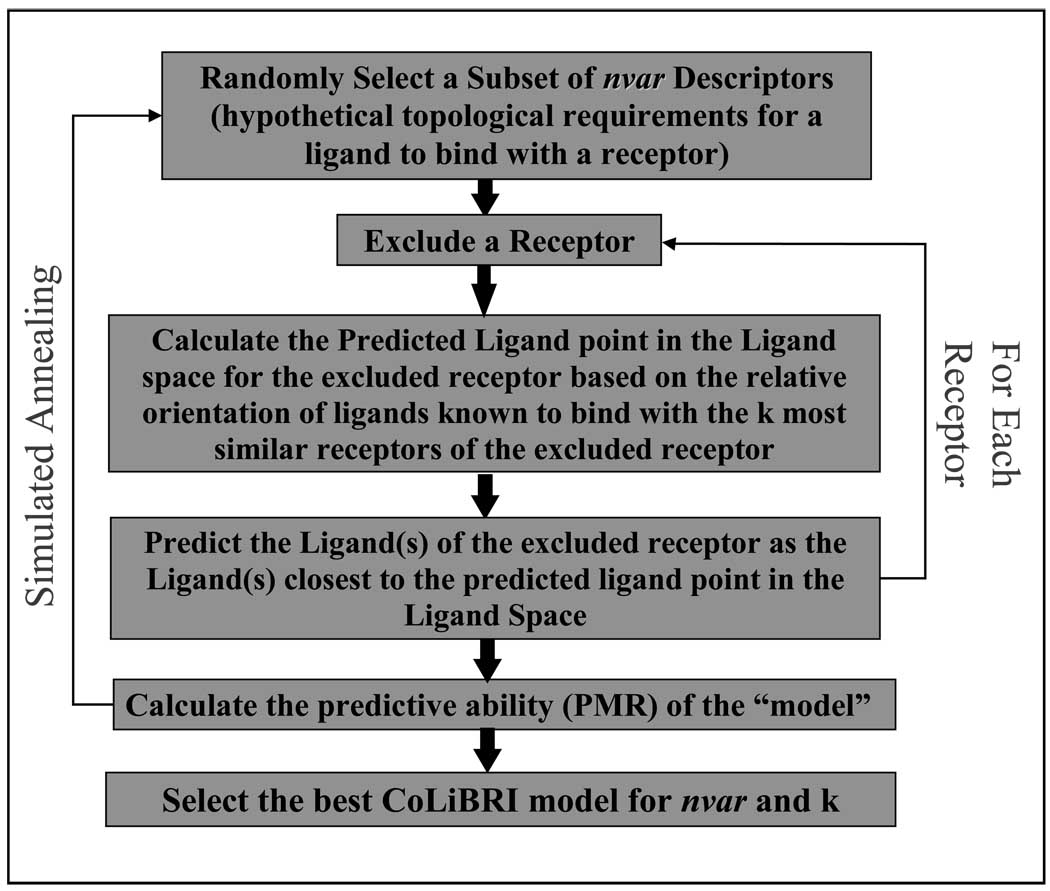

Using the TAE/RECON method, multiple descriptors were generated for both the receptor binding sites and their corresponding ligands so that each chemical entity is represented as a vector in a multidimensional TAE/RECON chemical space. Each dimension of this space corresponds to specific structural features of the ligands and active sites, but not every feature may be important for determining ligand-receptor complementarity. In order to select the subset of descriptors that best reflect the complementarity between receptors and their respective ligands, we have employed a Leave-One-Out (LOO) approach with variable selection. For each predefined number of variables, (nVar) we used stochastic sampling of the descriptors space and simulated annealing to optimize: (i) a selection of variables from the original pool of all molecular descriptors that are used to calculate relative similarities between receptors and their respective ligands (i.e., Euclidean distances in nVar-dimensional descriptor space), and (ii) the number of nearest neighbors (k) for each binding site in the receptor chemistry space used to estimate the position of the virtual complementary ligand in the ligand chemistry space. The overall flow chart of the CoLiBRI method is shown in Figure 3 and involves the following steps.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of CoLiBRI Method

(1) Select a subset of nVar descriptors randomly (nVar is a number between 1 and the total number of available descriptors). nVar is usually set to different values in several different runs. (2) Perform internal evaluation of this selection by a standard LOO cross-validation procedure and calculate the predictive mean rank (PMR) for the model as described below. (3) Repeat the procedure of generating trial correlations and calculate the corresponding PMR values (steps 1 and 2). The goal is to find the best topological requirements that minimize the PMR value of the CoLiBRI model. This optimization process is driven by a generalized simulated annealing (see below) using PMR as the objective function.

Cross-validation and the kNN principle applied to complementary prediction

The standard leave-one-out cross-validation procedure has been implemented as follows.

- Choose a receptor in the training set and select its k nearest neighbors in the TAE/RECON binding site descriptor space. Identify the ligands of the kNN receptors in the ligand space and use their coordinates to predict the coordinates of the chosen receptor’s virtual ligand. The coordinates of the virtual ligand are calculated from equation 2 for k≥2 (different values of k are explored to find the best model as described below).

where XRPredi is the chosen receptor i, Xppi is the predicted ligand vector for the receptor i, XRk is the k nearest receptor, and XL←Rk is the ligand of the k nearest neighbor receptor. For the case where KBest = 1, then Xppj is simply the position of the nearest receptor’s ligand in the ligand space, XL←R1.(2) - Rank known ligands based on their chemical similarity to the virtual ligand. The similarities are evaluated as Euclidean distances (eq. 3) using only the subset of descriptors that correspond to the current nVar selection.

(3) Repeat steps 1 and 2 until every receptor in the training set has been eliminated once, and the receptor’s virtual ligand and the rank order of all compounds are predicted.

- Calculate the PMR for the model using eq. 4, where NLR is the number of ligand-receptor complexes in the training set, Nvar is the number of descriptors used to build the correlation, Xjd and Xid are the dth selected descriptor for ligands j and i, and Xppi d is the dth descriptor of the predicted ligand point.

(4) Repeat steps 1 through 4 for k = 3, 4, 5, etc. Formally, the upper limit of k is the total number of ligand-receptor pairs in the data set minus one; however, the best value has been found empirically to lie between two and five. The k value that leads to the lowest PMR value is chosen as optimal.

Simulated annealing based optimization for variable selection

The concept of simulated annealing (SA) is to simulate a physical process called annealing, in which a system is heated to a high temperature and then is gradually lowered to a preset temperature value. During this process, the system samples possible configurations according to the Boltzmann distribution. At equilibrium, low energy states will be mostly populated. The first implementation of the SA procedure was described by32 followed by the development of a more generalized mathematical optimization protocol. The implementation of SA in our studies is as follows. (1) Generate a trial solution to the underlying optimization problem. For example, a CoLiBRI model is built based on a random selection of nVar descriptors. (2) Calculate the value of the fitness function, which characterizes the quality of the trial solution to the underlying problem, i.e., the inverse of the PMR value for a model built using only the selected nVar descriptors (PMRCurrent). (3) Perturb the trial solution to obtain a new solution; i.e., change a fraction of the currently used descriptors to other randomly selected descriptors and build a new CoLiBRI model for the new trial set of nVar descriptors. (4) Calculate the new fitness function value for the trial solution as the inverse of the new PMR value (PMRNew). (5) Apply the optimization criteria: if PMRCurrent < PMRNew the new solution is accepted and used to replace the current trial solution; if PMRCurrent > PMRNew, the new solution is accepted only if the following Metropolis criterion is satisfied (eq. 5).

| (5) |

where rnd is a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 and T is a parameter analogous to the temperature in Boltzmann distribution law. (6) Steps 3–5 are repeated until the termination condition is satisfied. The temperature lowering scheme and the termination condition used in this work have been adapted from33 as implemented by34. Thus, every time a new solution is accepted or when a preset number of successive trial solutions (100 steps) do not lead to a better result, the temperature is lowered by a preset value, usually by 10% (the default initial temperature is 100). The calculations are terminated when either the current temperature of the simulations is lowered to the value of T=10−6 or the ratio between the current temperature and the temperature corresponding to the best solution found is equal to 10−5. In summary, the CoLiBRI generates both an optimum k value and an optimal subset of nVar descriptors, which together produce a model with the best internally predictive power, in terms of PMR. This model can be used to identify correlations between a receptor active site and its ligand(s) such that a predicted point can be found for any receptor; and vice-versa, a predicted receptor point can be found for any ligand.

Model validation

Training and Test Set Selection

The dataset of 800 ligand-receptor complexes characterized by TAE/RECON descriptors was divided into the training (data used for model building) and test (data used for model validation) sets using the sphere exclusion method implemented in this laboratory35. Only binding site descriptors were used for these calculations. The purpose for this division was to generate a subset of ligands that did not bind any of the receptors in the training set. For the prediction of test set receptor ligands, the entire database of ligands was used. For additional validation, the World Drug Index (WDI) database was added to the list of available test set ligands and CoLiBRI models attempted to identify known ligands from the entire database.

Data Shuffling

To ensure that the models used to predict a test set were not based on chance correlations, the training set ligand-receptor associations were randomly shuffled. This data was then used to build CoLiBRI models, which were used for the test set prediction. If no significant model could be built for this randomized dataset, it would suggest that the models built using the correct data accurately ligand-receptor complementarity in high-dimensional descriptor space.

RESULTS

Development and validation of training set models

A diverse training set of 670 receptor binding pockets was selected using a Sphere Exclusion Algorithm36, as described above and used by CoLiBRI to build models with the lowest PMR (Eq. 4). The remaining 130 receptors were used as a test set to evaluate the ability of the optimized model(s) to identify the correct ligand of each test receptor out of the original 800 ligands.

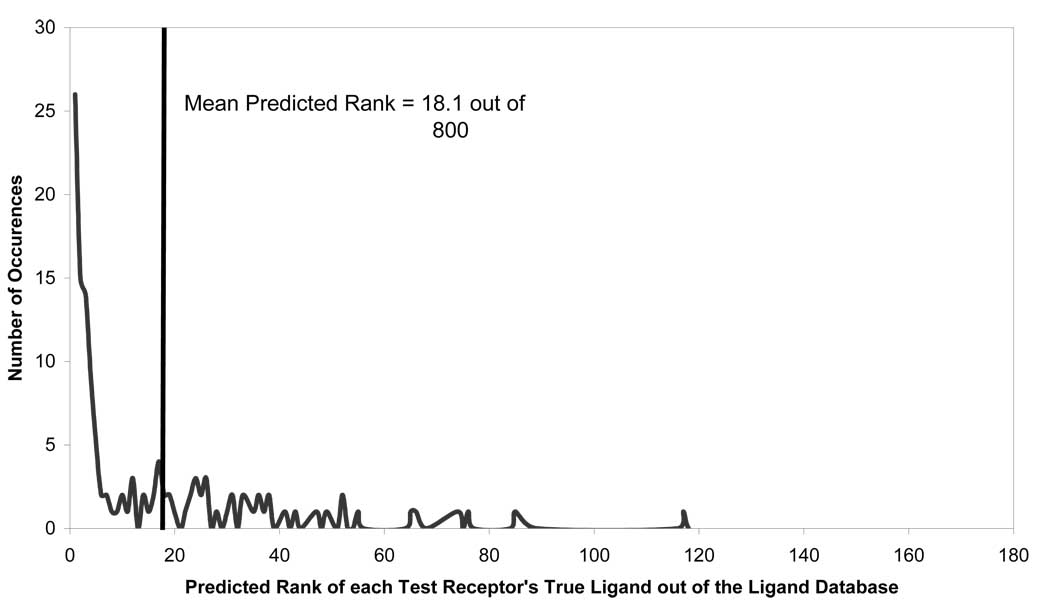

Previous studies from our group in the area of Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) indicated that the most reliable predictions of the test set data are obtained by using the consensus prediction approach37. In this approach, multiple variable selection models are built for the training set and used for the prediction of the test set ligands concurrently. To accomplish a consensus prediction, each model ranked all compounds in our ligand database based on the distance of each ligand to a test receptor’s virtual complementary ligand. We then re-ranked the ligands based on those that were most similar to the virtual ligand across multiple models. These studies have shown that the inclusion of variable selection improved the mean rank of the test set from 37 to 24 out of 800. Furthermore, by using 100 models for consensus prediction, the mean rank of the test set was improved from 24 to 18.1 out of 800, as shown in Figure 4. This increased the CPU time required to predict the test set by more than two orders of magnitude. Despite the increased CPU time, the calculations were still completed within 15 minutes. Since variable selection and consensus modeling vastly improved test set prediction, these methods were used in all subsequent model developments.

Figure 4.

Predictive ability of CoLiBRI to identify ligands of 130 test binding pockets out of the original 800 ligands.

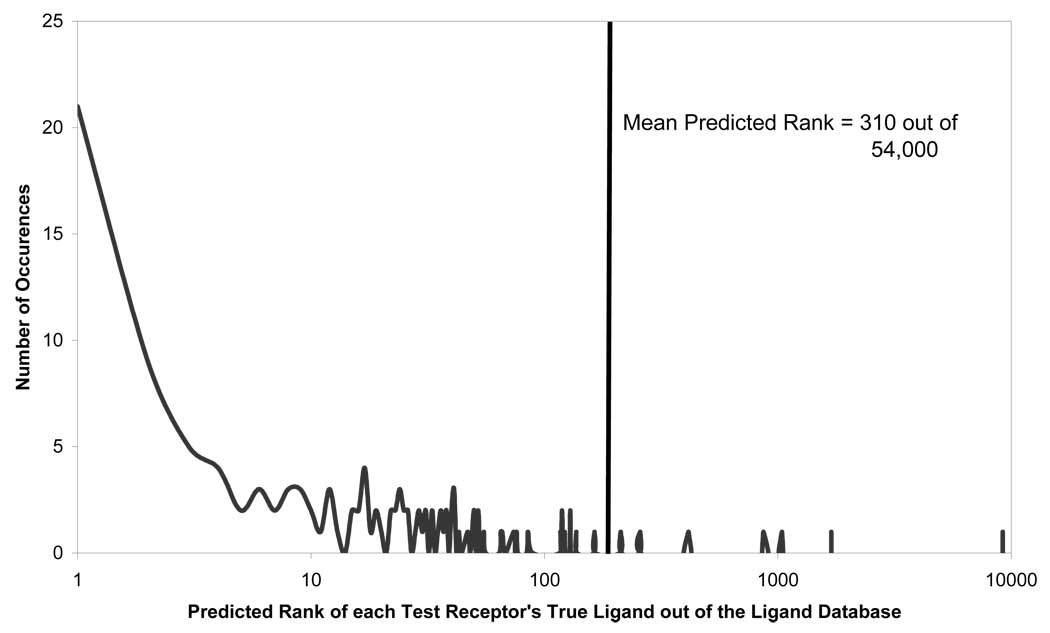

Application of CoLiBRI models to screening the WDI database

To simulate the use of CoLiBRI for screening large chemical databases, we added the 800 training set ligands to the WDI dataset38, which contains ca. 54,000 drugs and drug candidates. Training set CoLiBRI models were used in a consensus manner to predict the correct ligands for each of the 130 test receptors from of the entire combined database. The results illustrated that even when searching a large compound database, CoLiBRI is, on average, able to rank known ligands for a test receptor to within the top 310 ligands out of ca. 54,000, which translates to the top 1% of all compounds, as shown in Figure 5. The entire screening calculation for 130 test receptors took roughly four hours on a 2.4 GHz Pentium 4 machine. Figure 5 illustrates that most of the ligands were correctly identified within the top 12 ranked compounds; however there were two distant outliers that made the average rank much higher. These two outliers (PDB codes 1BM7 and 1G4J) did not contain a receptor-ligand complex from the same family as those in the training set, which could possibly explain the inaccuracy of the predictions. The ligands extracted from 1BM7 and 1G4J, flufenamic acid and 4-(Aminosulfonyl)-N-[(2,3,4,5,6-Pentafluorophenyl)methyl]-Benzamide, respectively, also do not appear to be very similar to ligands found within the training dataset. This additional dissimilarity may have also played a role in their poor prediction. As discussed in a later section, CoLiBRI appears to perform best when a receptor of the same family as the test set receptor is present in the training set. Otherwise, CoLiBRI is best used as a quick, rough filtering tool that can be used prior to the application of alternative less computationally efficient but perhaps more robust screening methodologies.

Figure 5.

Predictive ability of CoLiBRI to identify ligands of 130 test binding pockets from the WDI and the original 800 ligands.

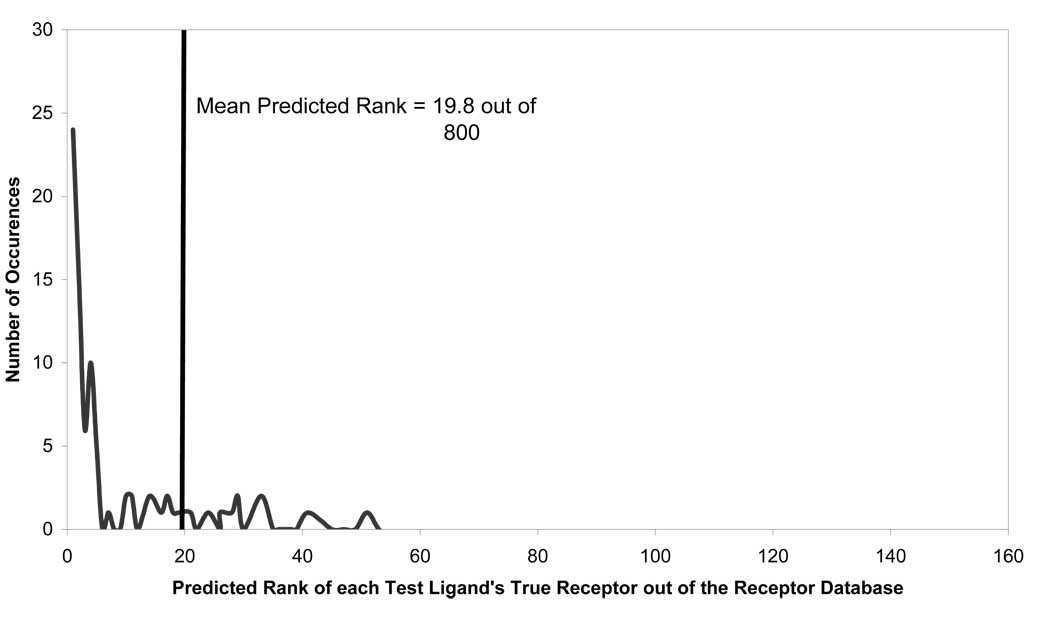

Identification of binding sites based on ligand information

As mentioned above, the CoLiBRI approach could be used to identify ligands based on the binding site descriptors, as well as predict binding sites for the ligands. The latter application uses the same formalism (Eq. 2–4), except that ligand coordinates are first mapped onto the binding site chemistry space, and then the virtual binding site is used as a query in chemical similarity calculations. We have tested CoLiBRI’s ability to identify the correct binding pockets for the same series of 130 test ligands for all 800 pockets. On average, CoLiBRI was able to successfully rank the correct binding pocket to be in the top 20 out of 800, or within the top 2.5%, as shown in Figure 6. As one can see from the graph, most of the predictions actually identified the correct binding pocket within the top 2 or 3 receptors. After careful analysis of the outliers, we discovered that they primarily fell within two classes: either there were multiple receptors of the same family in the dataset that a test ligand is known to bind with, and the correct binding site was ranked almost randomly within that top ranked family, or there were only one or no receptors of the same family in the training set.

Figure 6.

Predictive ability of CoLiBRI to identify receptor binding pockets of 130 test ligands from the library of 800 binding pockets.

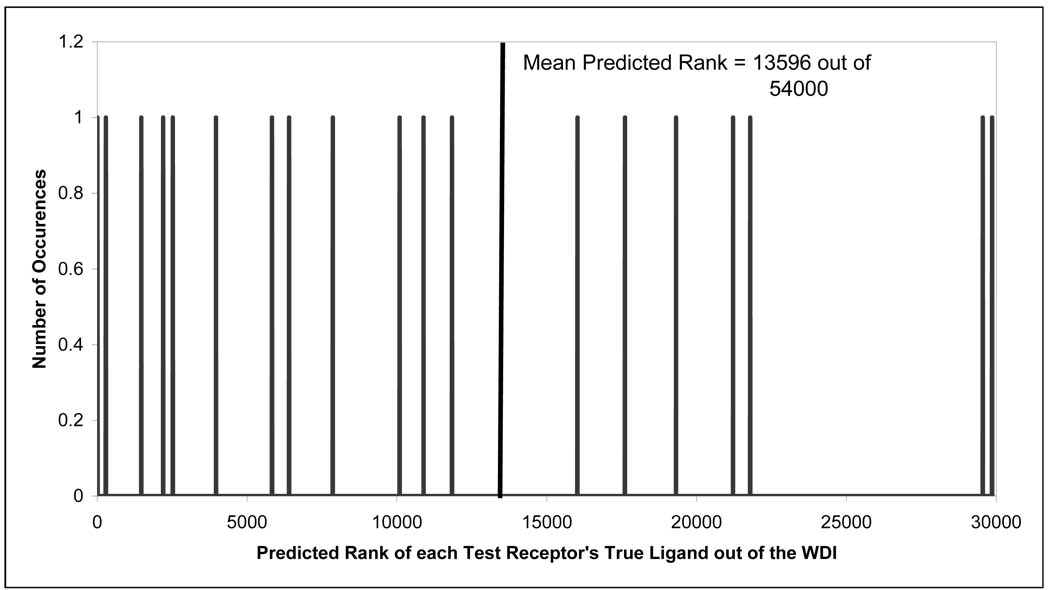

Identification of ligands for novel receptor families

As the most rigorous test for CoLiBRI, we explored its ability to predict ligands for receptors that did not have homologous receptor structures in the training set. To this end, we selected a test set of 22 ligand-receptor complexes that consists of receptors from three receptor families: 7 complexes from the peptidase M10A family, 7 complexes from the SRC-Tyrosine kinase family, and 8 complexes from the peptidase S1 family. We then used CoLiBRI to identify the correct ligands from the WDI for each of the test receptors. The results shown in Figure 7 demonstrate that the accuracy of CoLiBRI under this difficult test has decreased significantly; we were only capable of identifying the correct ligand within the top 25% of the database on average, as opposed to the results reported when test receptors were from the same family (Figure 5). This relative ineffectiveness of CoLiBRI under this test could still be acceptable when one needs to quickly screen a large, multimillion-compound library (25% accuracy for correct single hit identification is equivalent to the elimination of 75% of all compounds that are unlikely to be hits). These observations imply that the three test families are significantly different from the protein-ligand complexes in the training set so that the training set models are inapplicable to these test set proteins. In future studies, we shall consider introducing the model applicability domain for the CoLiBRI models, similar to our QSAR studies 35;39, to serve as a warning that the predictions may be inaccurate due to high dissimilarities between complexes known in the training set and test binding pockets or ligands.

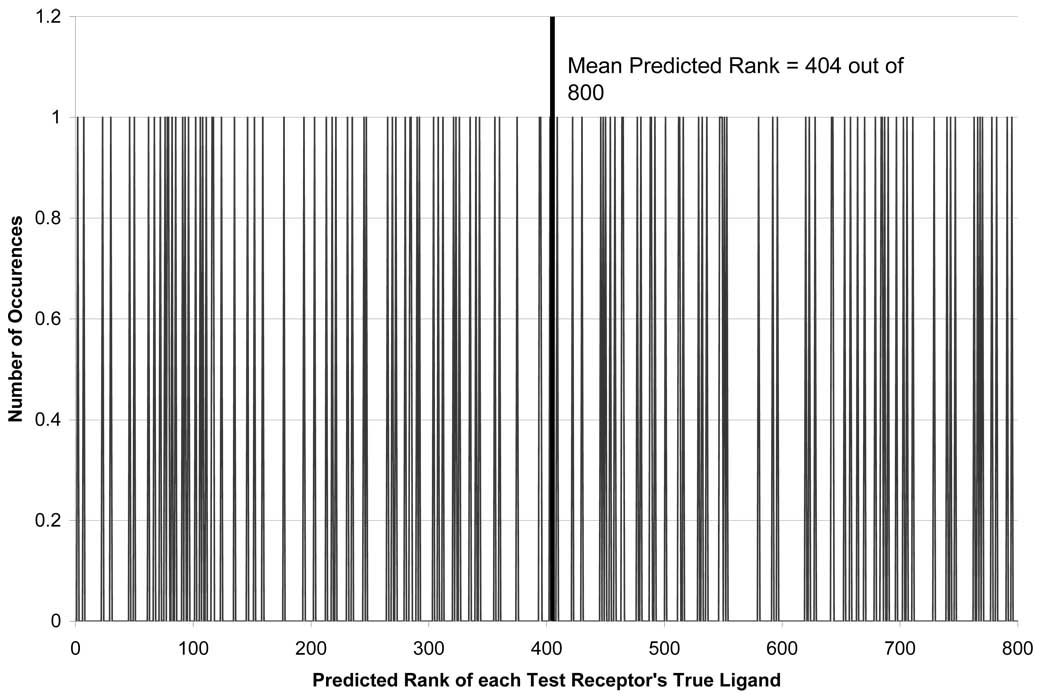

Figure 7.

Predictive ability of CoLiBRI to identify ligands of 22 test binding pockets from the WDI when there are no receptors of the same family in the training set.

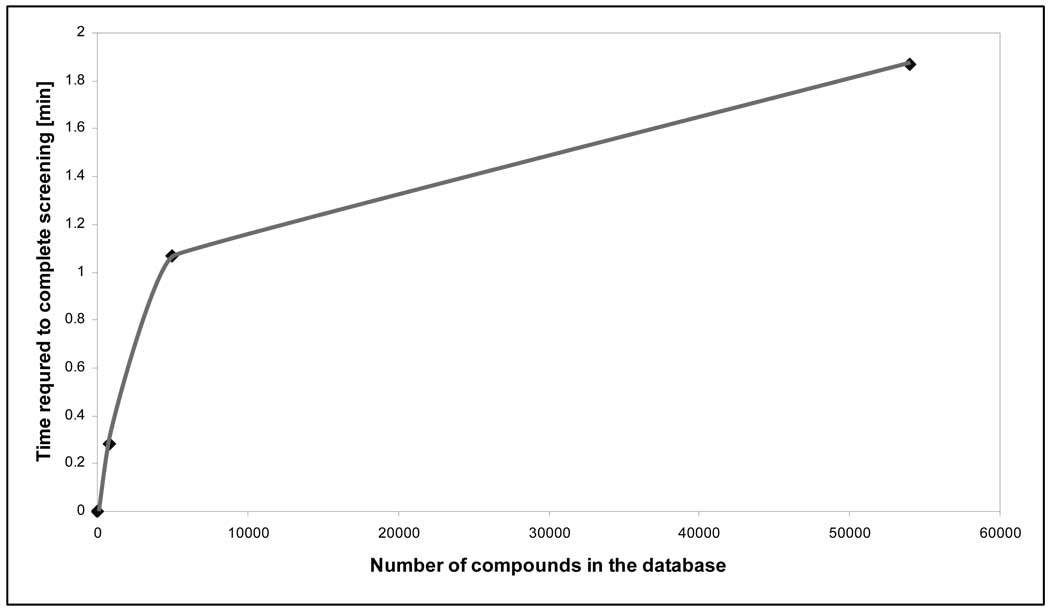

CPU requirements of CoLiBRI for efficient screening of large databases

The time required for CoLiBRI to screen the WDI with 100 CoLiBRI models for a single receptor took less than 2 minutes on a 2.4GHz Pentium 4 Desktop, as shown in Figure 8. These results illustrate that CoLiBRI may be successfully used as an efficient database filtering tool prior to more thorough and computationally intensive docking studies. The reason for the abrupt change in slope is due to a user-specified limit on the number of potential hits that are presented as output. For this computational speed assessment test, a limit was set to 5000 ranked ligands presented as output. Thus, CoLiBRI first ranks the first 5000 compounds (or a user-defined number) in the database using all models and then sequentially updates this sorted list as it searches the remainder of the compound database for additional viable hits.

Figure 8.

Time required for 100 CoLiBRI models to screen a single test receptor against various compound libraries on a P4 machine using a max. limit of 5,000 sorted hits displayed as output.

Validation of CoLiBRI models through random shuffling

In order to validate that the models were based on an inherently true correlation between properties of a receptor and its respective ligand, the ligands were shuffled such that for any one receptor, a randomly assigned ligand was used in place of the true ligand for model building. A test set of 130 receptors were then used to attempt the identification of the correct binding pockets using the models built on randomly associated ligand-receptor complexes. The PMRs for actual ligands (Figure 9) appear to be completely random suggesting that the models built with real data are based on actual complementarity correlations and are not artifacts of the model building process.

Figure 9.

Predictive ability of CoLiBRI to identify ligands of 130 test binding pockets when the training set ligand-receptor associations were shuffled and used for model building.

Discussion

The main objective of CoLiBRI is to build chemometric models that reflect complementarity between a receptor’s active site and its ligand, such that by knowing either the binding site or the ligand for a given receptor, a researcher could identify its complement from all other possibilities in a virtual database. In contrast with QSAR approach, which requires a dataset of known ligands for a particular receptor in order to build models and search for additional ligands of that receptor, CoLiBRI only requires the structure of the binding pocket. On the other hand, as compared with traditional 3D docking, CoLiBRI training set models are built across the entire available collection of diverse ligand receptor complexes as opposed to using a single receptor of interest for virtual screening. Consequently, CoLiBRI models use information about all other receptors when making prediction of ligands that bind to a particular receptor. In addition, CoLiBRI is significantly more computationally efficient that most 3D docking approaches.

As discussed above (cf Fig. 6), the “inverse” CoLiBRI approach could be also used to identify potential binding sites for a ligand. Binding to alternative sites is a frequent cause of side effects of drugs. The ability to identify potential undesirable interactions before a drug is brought to market is invaluable to the pharmaceutical industry. Foreknowledge of such interactions could send an otherwise effective compounds back through the lead optimization process before immense resources were lost in clinical trials. The structure of the ligand could be modified such that unwanted interactions are removed, while still maintaining its target property, thus leading to a highly useful drug.

To the best of our knowledge, the studies presented in this report are the first attempt to employ chemoinformatics approaches to the analysis of ligand-receptor complementarity. They could be extended in a number of ways. Thus, although this study was done using only TAE descriptors, in principle the descriptors for the receptor binding pockets and ligands could be of different types. This avenue worth further investigation: while TAE/RECON method appears to be unique in its ability to generate pseudo-molecular descriptors for the collection of active site atoms, a number of other descriptor types are specifically designed for ligands and may better describe their features. Three dimensional descriptors may also be used for the active site to preserve distance- and orientation-dependent interactions that may occur between a receptor and its ligands. Another important concept that we plan to examine in the future is the implementation of Support Vector Machines40 as an alternative to kNN. The current approach uses SA variable selection to optimize complementarity. The PMR function could easily be made continuous and applicable to Support Vector Theory by replacing k with a Gaussian weighting scheme and adding a continuous loss function. This could be done such that all neighbors in the initial starting space would be assigned distance dependent weights, where dissimilar neighbors would be given a weight of zero and closer neighbors would be given a weight higher than zero. Ligands or receptor active sites would be penalized based on their relative distance to their predicted point, which is calculated by orientations in the complementary space. This would allow us to take advantage of the inherent accuracy and generalization constraints of Support Vector Machines that may increase the predictive power of the models. Finally, as briefly mentioned above, a great deal of effort will be placed on defining adequate applicability domains for CoLiBRI models, which should prevent CoLiBRI from making unreliable predictions and therefore improve its accuracy.

Conclusions

We have developed a novel, predictive approach termed CoLiBRI to the analysis of ligand-receptor complementarity based on the representation of both ligands and their receptor active sites in a universal chemistry space. Unlike traditional docking methodologies that base their prediction of complimentary ligands using active site information alone, CoLiBRI predicts virtual ligands of the receptor based on its relative position in multidimensional chemistry space with respect to other known receptors. This representation affords straightforward and efficient identification of complementary ligands to a receptor from large databases of chemical compounds using rapid chemical similarity searches. Conversely, starting from the ligand chemical structure, one may identify possible complementary receptor cavities as well. This method is also distinct in that it penalizes the model for predicting an incorrect ligand for a receptor binding pocket, rather than optimizing the models by trying to correlate ligand binding to a single receptor. We have demonstrated that the knowledge of the active site structure affords identification of its complimentary ligands among the top 1% of a chemical database in 90% of cases, where a complex of the same receptor family was present in the training set. In the case where test receptors are highly dissimilar and not present among the receptor families in the training set, the prediction accuracy decreased significantly, however the method was able to quickly eliminate 75% of the chemical database as improbable ligands. Together, these results suggest that CoLiBRI can be used efficiently as a prescreening tool for traditional docking studies in order to identify a relatively small subset of compounds that are likely to contain actual hits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Tripos Assoc. for the software grant. These studies were supported in part by the NIH research grant GM066940.

References

- 1.Breneman CM, Thompson TR, Rhem M, Dung M. Electron Density Modeling of Large Systems using the Transferable Atom Equivalent Method. Comput. Chem. 1995;19:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R, Fang X, Lu Y, Wang S. The PDBbind database: collection of binding affinities for protein-ligand complexes with known three-dimensional structures. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2977–2980. doi: 10.1021/jm030580l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoichet BK, Kuntz ID. Matching Chemistry and Shape in Molecular Docking. Protein Engineering. 1993;6:723–732. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.7.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuntz ID, Meng EC, Shoichet BK. Structure-Based Molecular Design. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1994;27:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gschwend DA, Good AC, Kuntz ID. Molecular docking towards drug discovery. Journal of Molecular Recognition. 1996;9:175–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199603)9:2<175::aid-jmr260>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshiro CM, Kuntz ID, Dixon JS. Flexible Ligand Docking Using a Genetic Algorithm. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 1995;9:113–130. doi: 10.1007/BF00124402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodsell DS, Morris GM, Olson AJ. Automated docking of flexible ligands: Applications of AutoDock. Journal of Molecular Recognition. 1996;9:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199601)9:1<1::aid-jmr241>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osterberg F, Morris GM, Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. Automated docking to multiple target structures: incorporation of protein mobility and structural water heterogeneity in AutoDock. Proteins. 2002;46:34–40. doi: 10.1002/prot.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muegge I, Rarey M. Small Molecule Docking and Scoring. In: Lipkowitz KB, Boyd DB, editors. Reviews in Computational Chemistry. 17 ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollman P. Molecular-Dynamics and Free-Energy Perturbation Calculations - What Role Do They Play in Computer-Assisted Molecular Design. Faseb Journal. 1995;9:A1253–A1253. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kollman P. Free-Energy Calculations - Applications to Chemical and Biochemical Phenomena. Chemical Reviews. 1993;93:2395–2417. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aqvist J, Luzhkov VB, Brandsdal BO. Ligand binding affinities from MD simulations. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2002;35:358–365. doi: 10.1021/ar010014p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aqvist J, Medina C, Samuelsson JE. New Method for Predicting Binding-Affinity in Computer-Aided Drug Design. Protein Engineering. 1994;7:385–391. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Tropsha A. Calculation of the hydration free energies using an extended linear response method. J. Comp. Chem. 1999;20:749–759. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199906)20:8<749::AID-JCC1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou RH, Friesner RA, Ghosh A, Rizzo RC, Jorgensen WL, Levy RM. New linear interaction method for binding affinity calculations using a continuum solvent model. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:10388–10397. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tropsha A. Recent Trends in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships. In: Abraham D, editor. Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Sixth Edition ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. pp. 49–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingstone DJ. The characterization of chemical structures using molecular properties. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000;40:195–209. doi: 10.1021/ci990162i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett P. Chemoinformatics - similarity and diversity in chemical libraries. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner DB, Willett P. Evaluation of the EVA descriptor for QSAR studies: 3. The use of a genetic algorithm to search for models with enhanced predictive properties (EVA_GA) J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2000;14:1–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008180020974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazza CB, Sukumar N, Breneman CM, Cramer SM. Prediction of protein retention in ion-exchange systems using molecular descriptors obtained from crystal structure. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:5457–5461. doi: 10.1021/ac010797s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song M, Breneman CM, Bi J, Sukumar N, Bennett KP, Cramer S, Tugcu N. Prediction of protein retention times in anion-exchange chromatography systems using support vector regression. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002;42:1347–1357. doi: 10.1021/ci025580t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripos Inc. Sybyl User's Manual Version 7.8. St. Louis, MO: Tripos, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kier LB, Hall LH. Molecular connectivity VII: specific treatment of heteroatoms. J. Pharm. Sci. 1976;65:1806–1809. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600651228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kier LB, Murray WJ, Randic M, Hall LH. Molecular connectivity V: connectivity series concept applied to density. J. Pharm. Sci. 1976;65:1226–1230. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600650824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kier LB, Murray WJ, Hall LH. Molecular connectivity. 4. Relationships to biological activities. J. Med. Chem. 1975;18:1272–1274. doi: 10.1021/jm00246a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kier LB, Hall LH, Murray WJ, Randic M. Molecular connectivity. I: Relationship to nonspecific local anesthesia. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975;64:1971–1974. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600641214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kier LB, Hall LH. Molecular Connectivity in Chemistry and Drug Research. New York: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray WJ, Kier LB, Hall LH. Molecular connectivity. 6. Examination of the parabolic relationship between molecular connectivity and biological activity. J. Med. Chem. 1976;19:573–578. doi: 10.1021/jm00227a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray WJ, Hall LH, Kier LB. Molecular connectivity. III: Relationship to partition coefficients. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975;64:1978–1981. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600641216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen M, Beguin C, Golbraikh A, Stables JP, Kohn H, Tropsha A. Application of predictive QSAR models to database mining: identification and experimental validation of novel anticonvulsant compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2356–2364. doi: 10.1021/jm030584q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason JS, Good AC, Martin EJ. 3-D pharmacophores in drug discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2001;7:567–597. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH. Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953:1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun L, Xie Y, Song X, Wang J, Yu R. Cluster Analysis By Simulated Annealing. Comput. Chem. 1994:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng W, Tropsha A. Novel variable selection quantitative structure--property relationship approach based on the k-nearest-neighbor principle. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000;40:185–194. doi: 10.1021/ci980033m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golbraikh A, Shen M, Xiao Z, Xiao YD, Lee KH, Tropsha A. Rational selection of training and test sets for the development of validated QSAR models. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2003;17:241–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1025386326946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golbraikh A, Tropsha A. Predictive QSAR modeling based on diversity sampling of experimental datasets for the training and test set selection. Mol. Divers. 2002;5:231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1021372108686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen M, Beguin C, Golbraikh A, Stables JP, Kohn H, Tropsha A. Application of predictive QSAR models to database mining: identification and experimental validation of novel anticonvulsant compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2356–2364. doi: 10.1021/jm030584q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daylight. World Drug Index (WDI) 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tropsha A, Gramatica P, Gombar VK. The Importance of Being Earnest: Validation is the Absolute Essential for Successful Application and Interpretation of QSPR Models. Quant. Struct. Act. Relat. Comb. Sci. 2003;22:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. Springer Verlag; 1995. Vapnik, Vladimir. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.