Abstract

This article examines the ability of the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” to predict how panic attacks are generated and how panic attacks worsen posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The article does so by determining the validity of the Panic Attack–PTSD Model in respect to one type of panic attacks among traumatized Cambodian refugees: orthostatic panic (OP) attacks, that is, panic attacks generated by moving from lying or sitting to standing. Among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic, we conducted two studies to explore the validity of the Panic Attack–PTSD Model as applied to OP patients, meaning patients with at least one episode of OP in the previous month. In Study 1, the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” accurately indicated how OP is seemingly generated: among OP patients (N = 58), orthostasis-associated flashbacks and catastrophic cognitions predicted OP severity beyond a measure of anxious–depressive distress (SCL subscales), and OP severity significantly mediated the effect of anxious–depressive distress on CAPS severity. In Study 2, as predicted by the Panic Attack–PTSD Model, OP had a mediational role in respect to the effect of treatment on PTSD severity: among Cambodian refugees with PTSD and comorbid OP who participated in a CBT study (N = 56), improvement in PTSD severity was partially mediated by improvement in OP severity.

Keywords: stress disorder, posttraumatic, panic disorder, panic attack, flashbacks, catastrophic cognitions, Cambodian refugees, orthostatic intolerance

INTRODUCTION

PANIC ATTACK–PTSD MODEL

Several theorists have hypothesized that trauma results in panic attacks that play a key role in maintaining arousal and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [Falsetti and Resnick, 2000; Jones and Barlow, 1990]. In this article, we propose the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” to explain how panic attacks are generated and how they worsen PTSD.

The Panic Attack–PTSD Model (see Figure 1) includes the TCMIE Model of Panic Generation, which we have described in several articles [Hinton et al., 2004, 2005c, 2006b, 2007], and expands the TCMIE Model to demonstrate the relationship of panic attacks to anxious–depressive distress and PTSD. According to TCMIE Model, panic attacks may be generated by dysphoric associations to somatic sensations. This occurs when a sensation activates all or some of the following four types of fear networks (see below for further explanation): trauma memory networks (T), catastrophic cognitions (C), metaphoric associations, and/or interoceptive conditioning directly to fear and arousal-reactive sensations (I). Anxiety may then escalate (E) to the point of panic. (We believe that “fear of anxiety symptoms” assessed by instruments such as the Anxiety Sensitivity Index [ASI] is generated by these four types of dysphoric networks [see Hinton and Otto, 2006].)

Figure 1.

The Panic Attack–PTSD Model. It demonstrates how anxious–depressive distress contributes to the generation of panic attacks (the “TCMIE” Model), and the relationship of anxious–depressive distress and panic attacks to PTSD severity.

According to the Panic Attack–PTSD Model, anxiety and depression will worsen panic attack severity by several mechanisms. For one, more somatic symptoms will be induced owing to direct physiological mechanisms (viz., the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system) and owing to increased negative affectivity, the latter leading to memory bias, attentional bias for threat, attentional narrowing, and negative interpretive bias [Barlow, 2002]. In addition, anxiety and depression will result in fear networks being more readily activated if a somatic symptom is experienced. This is because anxiety and depression (a) increase the reactivity of fear networks (e.g., through increased amygdala reactivity) [Bouton et al., 2001; Chemtob et al., 1988; Nixon and Bryant, 2005] and (b) augment negative affectivity, the latter resulting in various mechanisms––memory bias, attentional bias for threat, attentional narrowing, and negative interpretive bias [Barlow, 2002]––that will cause symptoms to more easily activate fear networks.

According to the Panic Attack–PTSD Model, panic attacks will worsens PTSD severity in multiple ways: panic attacks (a) activate dysphoric networks, such as trauma-related fear networks, and (b) increase arousal. Increased activation of fear networks and arousal worsen PTSD [Chemtob et al., 1988; see too, Brewin and Holmes, 2003; Nixon and Bryant, 2005]. Though not shown in Figure 1, one would expect bidirectional effects, that is, feedback loops: worsened panic attacks and PTSD severity will each result in worsened anxious–depressive distress.

The Panic Attack–PTSD Model applies to all panic attack subtypes––for example, gastrointestinal panic (with gastrointestinal sensations activating dysphoric networks [TCMI]) or noise-induced panic attacks (with somatic sensations triggered by the noise-induced startle activating dysphoric networks [TCMI])––and the model applies to panic attacks when considered in aggregate. (That is, the total panic attack severity should be correlated to the total degree of fear of somatic and psychological symptoms, with that fear resulting from the four types of dysphoric networks [TCMI].) The Panic Attack–PTSD Model (which includes the TCMIE Model) can be used to explore panic attacks in other cultural groups. It provides insights into which traumatized patient groups and which traumatized cultural groups would be expected to have elevated rates of panic attacks and unique panic subtypes. The model also explains how panic attacks worsen PTSD severity and provides invaluable insights into how to treat those panic attacks in order to reduce PTSD severity [see Hinton et al., 2005a; Hinton and Otto, 2006].

Below we will show how the Panic Attack–PTSD Model applies to orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugees. We choose orthostatic panic (meaning panic triggered by rising from lying or sitting to standing) because of its frequency and clinical importance among Cambodian refugees. Among Cambodian refugees, sensations experienced upon standing, particularly dizziness and palpitations, activate dysphoric networks––extensive trauma associations and multiple catastrophic cognitions. In addition, traumatized Cambodians appear to have an impaired blood pressure to orthostasis owing to PTSD, among other causes, resulting in the frequent experiencing of somatic sensations upon standing that then may activate dysphoric networks (see below for further explanation).

RATES OF PTSD, PANIC DISORDER, AND ORTHOSTATIC PANIC AMONG CAMBODIAN REFUGEES

During Khmer Rouge rule (1975–1979), 1.7 million of Cambodia’s 7.9 million people died [Kiernan, 2002, p. 457]. Major traumas included slave labor, starvation, disease (e.g., malaria), physical displacement, lack of shelter (e.g., sleeping in the rain), physical and sexual violence, torture and killing of friends and relatives, and the constant threat of death by illness, starvation, or execution [Mollica et al., 1998]. As would be expected from these extraordinary levels of trauma, Cambodian refugees have high rates of psychopathology. In one study, 56% of the Cambodian refugees attending an outpatient psychiatric clinic had current PTSD, with elevated PTSD scores [on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; Hinton et al., 2006a]. In another study of psychiatric outpatients, 60% had panic disorder, including unusual subtypes. In that study, 29% of the patients had experienced an orthostatic panic episode in the last month, that is, panic triggered by shifting from a lying or sitting position to standing [Hinton et al., 2000].

ORTHOSTATIC DIZZINESS IN TRAUMATIZED ENGLISH-SPEAKING POPULATIONS: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In previous wars, orthostatic dizziness was a common presentation of trauma-related disorder: in the Civil War, “irritable heart” [DaCosta, 1871]; in World War I, “effort syndrome” [Lewis, 1917; Skerritt, 1983]; and in World War II, “neurocirculatory asthenia” [Friedman, 1947; Jones, 1948, pp. 422–423; Taylor and Brown, 1944; Whishaw, 1939]. In the contemporary United States, orthostatic dizziness often occurs in chronic fatigue syndrome and Gulf War syndrome. In chronic fatigue syndrome, orthostatic dizziness is thought to reflect a disordered autonomic nervous system (ANS), incapable of making heart rate and BP adjustment to standing [Rowe and Calkins, 1998; Schondorf and Freeman, 1999]. Gulf War veterans with PTSD and comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome often have orthostatic dizziness complaints, and in one study, they had an impaired BP response to standing, with the systolic BP impairment being significantly correlated to PTSD severity (r = .64, p < .001) [Peckerman et al., 2003].

THE RATE OF ORTHOSTATIC PANIC AMONG PATIENTS WITH PANIC DISORDER

Though orthostasis-induced dizziness was identified in the original formulations of the cognitive-behavior model of panic disorder as being an important trigger of panic attacks [Clark, 1986], such panic attacks have been minimally studied in Western populations [e.g., Taylor, 2000]. One study of a large sample of panic disorder patients in the United States found that 34.9% had experienced an orthostasis-triggered panic attack [Scupi et al., 1997].

CONTRASTING RATES OF PANIC DISORDER, PANIC ATTACKS, AND ORTHOSTATIC PANIC AMONG DIFFERENT ETHNIC PATIENT GROUPS WITH PTSD

As indicated above, traumatized Cambodian refugees with have high rates of panic attacks, panic disorder, and orthostatic panic. In Cambodian patients with PTSD, the rates of these pathologies are extremely elevated: panic attacks in the last month (100%), panic disorder (95%), and orthostatic panic in the previous month (62%) [Hinton et al., 2007]. Studies suggest high rates of panic attacks in traumatized English-speaking populations. In one study [Falsetti and Resnick, 1997], 69% of the patients seeking services for trauma had panic attacks. Several studies indicate high rates of panic disorder in trauma victims, in one case a lifetime prevalence of 55% [Melman et al., 1992], and studies suggest that panic disorder rates depend on the severity of the trauma [Breslau, 1987]. The national comorbidity demonstrated elevated rates of comorbid panic disorder among men and women with PTSD in the United States (12.6% vs. 7.3%) [Kessler et al. 1995]. No studies of the rate of orthostatic panic in English-speaking populations with PTSD have been conducted.

According to the Panic Attack–PTSD Model, the rate of panic attacks, panic attack subtypes, and panic disorder will vary in trauma victims depending on several variables: the extent of negative associations (e.g., trauma associations) to and negative appraisals (e.g., extensive catastrophic cognitions) of sensations caused by autonomic arousal. High rates of subtypes of panic attacks (e.g., gastrointestinal-focused, startle-induced, exercise-induced) will result from extensive negative associations to and negative appraisal of autonomic arousal sensations: if a group has extensive trauma associations to and catastrophic cognitions about the sensations experienced upon standing (e.g., dizziness), then a high rate of orthostatic panic would be expected.

THE PANIC ATTACK–PTSD MODEL AS APPLIED TO ORTHOSTATIC PANIC AMONG CAMBODIAN REFUGEES

Below we use the Panic Attack–PTSD Model (Figure 1) to reveal how orthostatic panic is generated among Cambodian refugees and how it results in worsened PTSD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Panic Attack–PTSD Model as applied to orthostatic panic.

The generation of orthostatic panic attacks among Cambodian refugees (the TCMIE Model)

We have utilized the Multiplex (TCMIE) Model to explain panic attack generation in the Cambodian population [Hinton et al., 2004, 2005c, 2006b, 2007], including orthostatic panic. According to this model, initial orthostatic symptoms, especially dizziness, may result from multiple causes, such as (a) somatic scanning [Barsky, 1994], (b) impaired BP adjustment to orthostasis [Hinton et al., 2004], and (c) impaired vestibular adjustment to orthostasis [see Furman and Jacob, 2001].

Next the orthostasis-induced symptom, most often dizziness, may activate one or more of the following four types of fear networks:

Trauma associations (T) may be activated [Hinton et al., 2007], such as dizziness-encoded memories of events that occurred in the Pol Pot period: (a) being struck in the head; (b) being forced to do slave labor while starving, resulting in extreme dizziness, even fainting; (c) encountering corpses, often bloated and maggot-infested, causing dizziness and nausea; (d) witnessing public executions, including eviscerations, causing dizziness and nausea; and (e) seeing bloody and eviscerated bodies when caught in the fighting between the Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese troops, causing dizziness and nausea.

Catastrophic cognitions (C) may arise, such as dizziness-related catastrophic cognitions: fears that dizziness results from a sudden surge of blood and khyâl (a wind-like substance) toward the head that may cause syncope, neck rupture, deafness, and/or blindness, and that dizziness upon standing indicates an impaired heart [Hinton et al., 2004]. These fears result from the Cambodian ethnophysiology (i.e., the Cambodian conceptualization of bodily physiology). Cambodians believe that standing-up may cause the following: (a) khyâl (a wind-like substance) and blood to rush upward in the body and into the head (an event called “khyâl overload”), with the upsurge of khyâl and blood possibly bringing about asphyxia, neck vessel rupture, and syncope; (b) khyâl and blood to stop coursing outward along the limbs, but rather to ascend upward into the body, leading to the disasters outlined above (see “a”) and to the “death” of the limbs from a lack of perfusion (i.e., a stroke); and (c) the heart to pound rapidly, sending excessive khyâl and blood into the neck and head, with the upsurge possibly causing neck rupture and syncope, and with the agitated motions of the heart possibly leading to heart arrest. Dizziness upon standing is considered to indicate that khyâl and blood have surged into the head and that all the processes indicated above (a–c) may be occurring.

Metaphoric associations (M) may be activated, such as dizziness-related metaphors, which then may evoke distressing current life issues. For example, Cambodians often describe negative life events in dizziness tropes: if a child becomes gang involved, the patient will say that the child “shakes me” (grolok khnyom), or that the child causes him or her to have a “spinning brain” (lop khue) [Hinton and Otto, 2006]. Owing to these metaphors, thinking about such life events may induce dizziness, and dizziness may evoke these life events.

Interoceptive conditioning directly to fear and arousal-reactive sensations (I) may be activated, such as dizziness-type direct interoceptive conditioning. Interoceptive conditioning of dizziness directly to fear and arousal-reactive symptoms results from experiencing fear and arousal symptoms along with dizziness during panic attacks, most often during PTSD or panic disorder PAs that are characterized by prominent dizziness. Interoceptive conditioning directly to fear and arousal-reactive symptoms is hypothesized to be a key aspect of panic generation [for a review, see Barlow 2002]. In this case, the sensation is not conditioned to a memory of some past trauma event, but rather directly to the emotion of fear and to arousal-reactive symptoms. (To give one example, a patient may repeatedly panic upon noticing chest tightness, fearing that it indicates imminent death from a heart attack. Later, after a normal stress test and other cardiac exams, though the patient no longer fears heart attack during periods of chest pain, the patient still may panic upon experiencing chest tightness. This is hypothesized to result from direct conditioning of chest discomfort to fear and autonomic arousal resulting from the multiple prior panic attacks.)

If the orthostasis-induced symptom activates fear networks, anxiety increases. Increased anxiety worsens arousal-reactive sensations that are already present––including the symptom (e.g., dizziness) that initially activated the fear networks––and induces new arousal-type symptoms (e.g., palpitations). Subsequently, owing to worsened arousal-reactive sensations (e.g., dizziness), there is further activation of the four types of fear networks (Clark, 1986). If all four types of fear networks become activated and generate a PA, we refer to it as a “TCMIE” PA, with “E” meaning “escalating arousal and panic” (see Figure 2). Other combinations also may occur: if trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions are the only type of fear networks that are clearly activated, it would be referred to as or a trauma associations–catastrophic cognitions” PA, that is, a “TC” PA.

How anxious–depressive distress worsens OP severity

Anxious–depressive distress will worsen orthostatic panic by two main mechanisms (see Figure 2):

Anxiety and depression will worsen orthostatic symptoms by (a) impairing vestibular- and BP-adjustment to standing, resulting in more orthostasis-induced symptoms, particularly dizziness [Furman and Jacob, 2001; Hinton et al., 2004], (b) inducing symptoms through direct physiological effects (e.g., activation of the sympathetic nervous system), and (c) increasing negative affectivity, which brings about memory bias, attentional bias for threat, attentional narrowing, and negative interpretive bias [Barlow, 2002]; and

Anxiety and depression will lead to fear networks being more readily activated if an orthostatic symptom is experienced because they increase (a) the reactivity of fear networks (e.g., through increased amygdala reactivity) [Bouton et al., 2001; Chemtob et al., 1988; Nixon and Bryant, 2005] and (b) negative affectivity, which results in memory bias, attentional bias for threat, attentional narrowing, and negative interpretive bias [Barlow, 2002].

How OP worsens PTSD severity

OP worsens PTSD severity (see Figure 2). Increased orthostatic panic will lead to greater activation of dysphoric networks, including trauma-related fear networks, and to heightened arousal. Subsequently, activation of dysphoric networks and heightened arousal will worsen PTSD symptomatology. According to an influential model of PTSD chronicity, arousal plays a key role: it leads to a predisposition to activation of fear networks and to a general state of fearful hypervigilance [Chemtob et al., 1988; see too, Brewin and Holmes, 2003; Nixon and Bryant, 2005].

PREVIOUS STUDIES OF THE “PANIC ATTACK–PTSD MODEL” AS APPLIED TO ORTHOSTATIC PANIC

In an orthostatic challenge (sitting to standing) using a continuous BP assessment, we found that Cambodian OP patients (i.e., patients having panic triggered by orthostasis in the previous month) have an impaired systolic BP response at the systolic BP nadir (approximately 20 sec post-orthostasis) as compared to non-OP patients and that orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions predicted the degree of panic during the orthostatic challenge [Hinton et al., in press a; see too, Hinton et al., 2004]. In an orthostatic challenge (sitting to standing), only patients with a history of panic in the last month (i.e., OP patients) panicked, whereas none of the non-OP patients did [Hinton et al., in press a]. Also, among patients experiencing orthostatic challenge–induced panic, there were prominent orthostatic challenge–induced flashbacks and catastrophic cognitions, and among those patients, the severity of both orthostatic challenge–induced flashbacks and orthostatic challenge–induced catastrophic cognitions were correlated with (a) the severity of orthostatic panic in the previous month and (b) the severity of orthostatic challenge–induced panic. In a study of orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugees, we found that SCL scores, as well as orthostasis-associated flashbacks and catastrophic cognitions, were more elevated in the OP group as compared to the non-OP group [Hinton et al., 2005c]. In a study of Cambodian psychiatric patients, using both the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (a measure of the degree of fear of anxiety-related sensations) and a Cambodian-specific ASI Addendum, fear of orthostatic dizziness was the best predictor of the presence of psychopathology (viz., PTSD and panic disorder) [Hinton et al., 2005b].

STUDY AIMS

We designed two studies to further investigate the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” as applied to orthostatic panic. In Study 1, we hypothesized that (a) among the entire sample, OP patients would have greater psychopathology, including CAPS severity and PTSD rates, (b) among OP patients, orthostasis-associated flashbacks and orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions would predict OP severity beyond the measure of anxious–depressive distress, and (c) among OP patients, the effect of anxious–depressive psychopathology on severity of PTSD-type psychopathology (viz., Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) would be mediated by OP severity. In Study 2, we hypothesized that, among patients in a CBT study who had PTSD and comorbid orthostatic panic, PTSD improvement would be mediated by improvement in orthostatic panic severity.

STUDY 1

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

The patients were all part of the clinical caseload of the first author, and received treatment at a freestanding psychiatric clinic serving a large Cambodian population in Lowell, MA. To be eligible, the patient had to have a history of exposure to the Cambodian Genocide (1975–1979); to have been at least 7 years of age at the time of the beginning of the Cambodian Genocide (hence older than 35 at the time of the study); and to be less than 65 years of age. Patients with any of the following disorders were excluded: organic mental, schizophrenic, bipolar, other psychotic, substance abuse, or substance dependence. Of the screened patients, 5 did not meet inclusion criteria (1 owing to psychosis, 4 to substance abuse). Eligible patients were invited to participate, and informed consent was obtained after a full explanation of the survey. It was made clear to patients that nonparticipation would in no way affect care at the clinic and was completely voluntary. Eleven patients refused because of time constraints. Of the 130 participating patients, 72 were women, 58 men.

MEASURES

All measures were translated and then back-translated, as per standard procedure [Mollica et al., 1987]. To determine interrater and test–retest reliabilities, patients were independently interviewed by the first author (who is fluent in Cambodian) and a native Cambodian speaker (who was a physician in Cambodia and is currently training to be a social worker in the United States). The Cambodian speaker received extensive training in the instruments.

OP Module

We used a structured interviewed to assess for OP. As the initial probe question, we asked the following: “In the last 4 weeks, upon standing, did you suddenly feel anxious, dizzy, or ill?” If so, the patient was queried about the most recent episode, making sure that it (a) constituted orthostasis-induced dysphoria, (b) met panic attack criteria (as per the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) [First et al., 1995], and (c) was not preceded just before standing by a panic attack. If the episode did not meet all three criteria, the patient was questioned about the experiencing of any other orthostasis-induced episode in the last 4 weeks; and if such was the case, the episode was investigated as outlined above. With 20 patients, using these criteria, interrater reliability was excellent (κ = 1.0).

OP Severity Scale

We assessed OP severity in the previous 4 weeks on three dimensions [cf. Shear et al., 1997], each scored on a 0–4 Likert-type scale: (a) frequency, (b) degree of distress, and (c) length. So the score range of the OP Severity Scale was 0–12. With 30 patients, we determined the OP Panic Severity Scale’s interrater (Pearson r = .97) and test–retest (at 1 week; Pearson r = .88) reliability.

Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale

For the Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale, we used the following probe question: “In the last 4 weeks, when you stood up and felt anxious, dizzy, or ill, did you have any images of the past come into your mind?” If so, the patient was asked to describe the episode in order to verify that it occurred during an OP episode and that it constituted a flashback (i.e., a score of a least a “1” on the CAPS Flashback Intensity Scale). If both conditions were met, flashback severity was assessed by the CAPS Flashback Intensity Scale [Weathers et al., 2001], which rates severity on a 0–4 Likert-type scale. If a patient denied feeling anxious, dizzy, or ill at anytime upon standing up in the last 4 weeks, the patient was asked, “In the last 4 weeks, when you stood up, did you have any images of the past come into your mind?” With 20 patients, we determined the Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale’s interrater (Pearson r = .92) and test–retest (at 1 week; Pearson r = .85) reliability.

Orthostasis Catastrophic Cognitions Severity Scale

We used the following question format: “In the last 4 weeks, when you stood up and felt anxious, dizzy, or ill, did you have any of the following thoughts go through your mind? Did you think, ‘I am … [e.g., going to pass out]?’” We used 9 queries of the Panic Attack Cognitions Questionnaire [Clum et al., 1990], along with 7 questions about culturally specific fears concerning orthostasis-induced sensations [see Hinton et al., 2004, 2005c]: “khyâl overload,” “neck vessel rupture,” “deafness from khyâl from the ears,” “upward hitting abdominal khyâl,” “weak,” “weak heart,” and “death of the arms and legs.” Catastrophic cognition severity was assessed on a 0–4 Likert-type scale. If a patient denied feeling anxious, dizzy, or ill at anytime upon standing up in the last 4 weeks, the patient was asked, “In the last 4 weeks, when you stood up, did any of the following thoughts go through your mind? Did you think, ‘I am … [e.g., going to pass out]?’” We then asked about the 16 catastrophic cognitions. With 20 Cambodian patients, we assessed the Orthostatic Catastrophic Cognitions Severity Scale’s test–retest reliability (at 1 week; Pearson r = .89).

Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL) Scales

The SCL measures distress within the past week on several dimensions [Derogatis, 1994], with each item measured on a 0–4 Likert-type scale. For the present study, two subscales were used: anxiety (10 items) and depression (13 items). We used the composite score of the anxiety and depression scales as a measure of anxious–depressive psychopathology. With 20 Cambodian patients, we assessed the composite score’s test–retest reliability (at 2 weeks; r = .88).

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

The CAPS rates, on 0–4 Likert-type scales, the frequency and intensity of each of the 17 DSM-IV–based PTSD symptoms (Weathers et al., 2001). With 20 Cambodian patients, the CAPS has good interrater (r = .92) and test–retest (at 1 week; r = .84) reliability [Hinton et al., 2006a].

PTSD status

To determine PTSD presence, we used the “F1/I2 rule,” that is, frequency ≥ 1 and intensity ≥ 2 [for a review of the CAPS scoring rules, see Weathers et al., 2001]. As assessed with 20 patients, the F1/I2 rule coincides well with a Cambodian-speaking psychiatrist’s determination (κ = .89), as guided by the SCID module for PTSD [Hinton et al., 2006a].

PROCEDURE

A bicultural worker assessed the presence of current, that is, in the last month, orthostatic panic (OP Module), and, if present, its severity (OP Severity Scale). Blind to OP severity, the first author––who is fluent in Cambodian––then interviewed the patient to assess for the presence and severity of orthostasis-associated flashbacks (Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale) and orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions (Orthostatic Catastrophic Cognitions Scale). Blind to the patient’s OP status, a Cambodian bicultural worker administered the CAPS and SCL subscales.

RESULTS

In total, 45% (58/130) of the patients had orthostatic panic, with the OP patients having a mean OP Severity Scale score of 7.2 (SD = 2.5). For a comparison of OP patients to non-OP patients in terms of gender, age, CAPS, PTSD rates, SCL, Flashback frequency, and severity of orthostasis-associated cognitions, see Table 1. As indicated in Table 1, 52% (30/58) of the OP patients had orthostasis-associated flashbacks, and among those 30 patients, the Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale score was high (M = 3.43, SD = 0.82), with 63% (19/30) having a flashback rated as a “4” in intensity. Among OP patients, the mean Orthostatic Catastrophic Cognitions Severity Scale score was 2.8 (SD = 0.92). In the entire sample, 51.54% (67/130) of patients had PTSD. As shown in Table 1, CAPS scores were higher in the OP patients, as were rates of PTSD, 70.15% (47/67) versus 17.2% (11/63), giving an odds ratio of 11.1 (95% confidence interval, 4.8 to 25.9).

TABLE 1.

Mean values or frequencies for demographics and psychometrics as a function of orthostatic panic status in a Cambodian psychiatric outpatient population (N = 130)

| Variable | OP patients (n = 58) | Non-OP patients (n = 72) | χ2(1) or t(128) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Gender (%) | 58.6 | 52.8 | 0.98 |

| Age | 50.61 (8.32) | 53.70 (7.43) | 2.22 |

| CAPS | 1.87 (0.75) | 0.71 (0.72) | 8.45** |

| Rate of PTSD (%) | 70.15 | 17.5 | |

| SCL | 2.51 (0.85) | 1.41 (0.74) | 9.75** |

| Orthostatic Flashbacks (%) | 52 | 0 | |

| OCC Severity Scale | 2.8 (0.92) | 1.21 (0.79) | 7.92** |

Note. Chi-square test used for the gender variable; t test for all other variables. OP patients = patients with at least one episode of orthostatic panic in the last month; Non-OP patients = patients without any episodes of orthostatic panic in the last month; SCL subscales = the average of the Symptom Checklist-90-R’s anxiety and depression subscale; OCC = Orthostasis Catastrophic Cognitions. All scales are rated on a 0–4 Likert-type scale.

p < .05,

p < .01

Among OP patients, we investigated whether orthostasis-associated flashbacks and orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions would predict OP severity beyond the measure of anxious–depressive distress. Sequential regression was employed to determine how much the addition of information regarding orthostasis-associated flashbacks (Orthostasis Flashback Severity Scale) and then orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions (Orthostatic Catastrophic Cognitions Severity Scale) improved prediction of OP severity beyond that afforded by anxious–depressive distress (SCL scales). Table 2 displays the B, B’s standard error, β, and R2 after each sequential addition of a variable. After Step 3, with all independent variables in the equation, R = .79, F(3, 54) = 30.8, p < .001. After Step 1, with SCL in the equation, R2 = .40, Fincl(1, 54) = 36.85, p < .001. After Step 2, with orthostasis-associated flashbacks added to the prediction of OP severity, R2 = .59, Fincl(1, 54) = 26.41, p < .001. After Step 3, with orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions added to the prediction of OP severity, R2 = .63 (adjusted R2 = .62), Fincl(1, 54) = 5.7, p < .05. Thus the addition of orthostasis-associated flashbacks and then orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions to the equation each reliably improved R2.

TABLE 2.

Hierarchical regression analysis summary for variables predicting the OP Severity Scale scores among OP patients (N = 58)

| Variable | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| SCL | 1.84 | 0.30 | .62* |

| Step 2 | |||

| SCL | 1.11 | 0.29 | .38* |

| OF Severity Scale | 0.68 | 0.13 | .51* |

| Step 3 | |||

| SCL | 0.77 | 0.31 | .26* |

| OF Severity Scale | 0.52 | 0.14 | .39* |

| OCC Severity Scale | 0.76 | 0.32 | .29* |

Note. R2 = .40 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .20 for Step 2; ΔR2 = .04 for Step 3 (ps < .05). OP patients = patients with at least one episode of orthostatic panic in the last month; SCL = The average of the Symptom Checklist-90-R’s anxiety and depression subscales; OF = Orthostatic Flashback; OCC = Orthostatic Catastrophic Cognitions. All scales are rated on a 0–4 Likert-type scale.

p < .05

Among PTSD patients, we investigated whether the effect of anxious–depressive distress (as assessed by the SCL subscales) on PTSD severity was mediated by OP severity. To demonstrate full mediation [Baron and Kenny, 1986], the following three conditions should be met: (a) a significant correlation between the predictor variable and the criterion; (b) significant correlations between the mediator and both the predictor and criterion variable; and (c) a reduction of the relationship between the predictor and criterion to nonsignificance when the mediator is included. Satisfying condition “a,” the SCL was significantly correlated to the CAPS score (β = .59, p < .01), and satisfying condition “b,” OP Severity Scale was correlated to the SCL (β = .62, p < .01) and the CAPS (β = .60, p < .01). To assess for condition “c,” we regressed the CAPS on both the SCL and OP Severity; upon doing so, SCL’s β dropped from .59 to .32 (p < .01), with the amount of explained variance increasing (adjusted R2 from .35 to .41; ΔR2 = .06) and OP’s β falling to .39 (p < .01). Though full mediation was not present (see Figure 3), the Sobel test [MacKinnon et al., 2002] revealed the role of OP severity as an intervening variable of SCL’s effect on CAPS severity to be highly significant (Sobel test z = 23.8, p < .001, two-tailed).

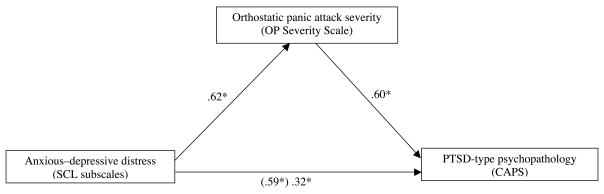

Figure 3.

Mediation of the link between anxious–depressive distress (SCL) and PTSD-type psychopathology (CAPS). All values are standardized regression coefficients (βs). The value given in the parenthesis is the beta for the regression of anxious–depressive distress (SCL) on PTSD severity (CAPS) before entry of the putative mediator (Orthostatic Panic Severity, i.e., the OP Severity Scale). The beta for this path decreased when the putative mediator (Orthostatic Panic Severity, i.e., the OP Severity Scale) was entered in the regression. *p < .01

STUDY II

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

In the second study, we pooled the results from two published CBT outcome studies [for details, see Hinton et al., 2005a; Otto et al., 2003] and one just completed study in order to obtain a large sample with PTSD and comorbid orthostatic panic. The sample size consisted of 56 patients, with 28 in waitlist, 28 in active treatment. Please see the two studies for details of the treatment, recruitment, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria. For the studies, it was made clear to patients that nonparticipation would in no way affect care at the clinic and was completely voluntary.

MEASURES

CAPS

See Study I, Measures section.

Orthostatic Panic Severity Scale

See Study I, Measures section.

PROCEDURE

Therapy

Therapy consisted of 12 session of CBT, with one group in waitlist, another in treatment [for details, see Hinton et al., 2005a; Otto et al., 2003]. The treatment, which we refer to as “Flexibility and Sensation-Reprocessing Therapy” (FAST) owing to the emphasis on increasing psychological flexibility and modifying sensation-related networks (e.g., trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions), includes some of the following elements: (1) providing information about the nature of PTSD and PD; (2) muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing procedures, including the use of applied relaxation techniques; (3) performing a culturally appropriate visualization––a lotus bloom that spins in the wind at the end of a stem (an image encoding key Asian cultural values of flexibility)––while enacting analogous rotational movements at the neck after each relaxation of the neck and head musculature (these rotational movements also serve as an introduction to dizziness interoceptive exercises); (4) framing relaxation techniques as a form of mindfulness, that is, as an attentive focusing upon specific sensory modalities (e.g., muscular tension and the kinesthetics of breathing); (5) cognitive restructuring of fear networks, especially trauma memory associations to and catastrophic misinterpretations of somatic sensations; (6) interoceptive exposure to anxiety-related sensations in conjunction with re-association to positive images to treat panic attacks generated by sensation-activated fear networks, such as trauma associations, catastrophic cognitions, metaphoric associations, and interoceptive conditioning; (7) providing an emotional processing protocol to utilize during times of trauma recall, the protocol bringing about a shift from an attitude of pained acceptance to one of mindfulness (i.e., multi-sensorial awareness of the present moment); (8) exploring orthostatic panic (and neck-focused panic), as in firing sequences––for example, the sensations, activities, and thoughts that initiate the sequence leading to panic––and associated trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions; (9) exposure to and narrativization of trauma-related memories––most particularly, those associated with panic attacks and nightmares––by having the patient describe the event in detail, including sensory elements (but without repeated exposure, unless the same flashback recurs); and (10) teaching cognitive flexibility by (a) the lotus visualization and enactment; (b) a flexibility protocol; (c) practice in state shifting, or set shifting, during the emotional processing protocol, which entails shifting from (i) acknowledgment of the trauma event’s occurrence, (ii) to self and other pity, (iii) to loving kindness, and (iv) to mindfulness; and (d) practice in state shifting, or set shifting, within the mindfulness component, by shifting from one sensory modality to another.

Statistical analyses

We examined baseline differences between the CBT-treated participants and waitlist-control participants on demographic characteristics, PTSD severity, and orthostatic panic severity using one-way analyses of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We computed residualized change scores for the outcome measure and the putative mediator by regressing the posttreatment scores on the pretreatment scores for all study participants.

The hypothesis that the effects of CBT would be mediated by changes in orthostatic panic severity was tested in accordance with the analytic steps outlined by Baron and Kenny [1986] [for a description of the same analytic strategy as used in another study, see Smits et al., 2004]:

In Step 1, we tested the effects of treatment on the proposed mediator by performing and ANOVA with treatment group (CBT vs. waitlist) as the grouping factory and OP severity as the dependent variable.

In Step 2, we tested for the presence of a treatment effect by performing a series of univariate ANOVAs with treatment group (CBT vs. waitlist) as the grouping factor and residualized change scores of the outcome measure (CAPS) as the dependent variable.

In Step 3, the relationship between the proposed mediator and clinical outcome measure was examined, by performing analyses of covariance with treatment group (CBT vs. waitlist) as the grouping factor, residualized change scores of clinical status as the dependent variable, and orthostatic panic severity as the covariate.

In Step 4, we tested the relationship between treatment and PTSD severity after controlling for the effects of the proposed mediator. According to Baron and Kenny [1986], evidence for full mediation exists if the relationship between treatment and outcome is no longer significant after controlling for the effects of the mediator, whereas evidence for partial mediation exists if the relationship between treatment and outcome is significantly attenuated (but still significant) after controlling for the mediator effects. Therefore we compared the effect of treatment when the putative mediator was not controlled (Step 2) to the effect of treatment when the putative mediator was controlled.

RESULTS

EFFECT SIZES

The two group conditions did not differ in baseline severity of orthostatic panic or CAPS score. The treatment group improved across treatment, whereas the waitlist group did not. For effect sizes, see Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Mean and standard deviation for PTSD severity (CAPS) and orthostatic panic severity (OP Severity Scale) at pre- and posttreatment for the CBT and waitlist condition, as well as between-group effect sizes for the CAPS and the OP Severity Scale

| Treatment condition |

Between-group effect sizea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | CBT (n = 28) | Waitlist (n = 28) | |

| CAPS | 2.0 | ||

| Pretreatment | 72.18 (11.86) | 73.00 (13.94) | |

| Posttreatment | 40.92 (18.60) | 70.25 (10.28) | |

| OP Severity Scale | 2.2 | ||

| Pretreatment | 7.95 (1.94) | 8.26 (2.10) | |

| Postreatment | 2.82 (2.66) | 7.87 (1.85) | |

Between-group effect size = (MCBT-pre − MWL-post)/SDpooled, where SDpooled = √ (SDCBT-post2 + SDWL-post2)/2

MEDIATION ANALYSIS

Effects of treatment on the proposed mediator (mediation test–step 1)

Effect sizes for orthostatic panic are presented in Table 3. CBT-treated participants displayed significantly greater improvements in OP severity relative to the waitlist control participants, F(1, 54) = 95.82, p < .01. This confirms the presence of the first condition for mediation.

Effects of treatment on PTSD severity (mediation test–step 2)

Significantly greater improvement was observed among CBT-treated participants relative to waitlist control participants in respect to PTSD severity. The percentage of variance accounted for by treatment was F(1, 54) = 80.38, p < .01, η2 = 59%.

Relationship between change in the proposed mediator and treatment outcome (mediation test–step 3)

We found a significant covariation between residualized change in OP severity and the PTSD severity after controlling for treatment, F(1, 54) = 35.83, p < .01.

Effects of treatment on PTSD severity after controlling for the effects of the proposed mediator (mediation–step 4)

Analysis revealed that changes in OP severity partially mediated the effect of treatment on PTSD severity, with the effect of treatment on CAPS severity greatly dropping after controlling for the effect of OP severity: from F(1, 54) = 80.38, p < .01, η2 = 59% (see Step 2) to F(1, 54) = 4.41, p = .04, η2 = 8%.

DISCUSSION

The two studies support the validity of certain components of the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” as applied to orthostatic panic, namely, the interaction of anxious–depressive dysphoria, PTSD, and certain dysphoria networks, specifically, trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions. However, certain components of the model, such as certain dysphoria networks (specifically, metaphoric associations and direct interoceptive conditioning to fear and symptoms of autonomic arousal) were not assessed. In Study 1, among a large Cambodian patient sample, (a) OP patients had greater psychopathology, including CAPS severity and PTSD rates, and more activation of fear networks during orthostasis, that is, more orthostasis-associated flashbacks and more severe orthostasis-related catastrophic cognitions; (b) among OP patients, orthostasis-associated flashbacks and orthostasis-associated catastrophic cognitions predicted OP severity beyond the measure of anxious–depressive distress; and (c) among OP patients, the effect of anxious–depressive psychopathology on PTSD-type psychopathology (viz., the CAPS) was significantly mediated by OP severity. In Study 2, among patients with PTSD and comorbid orthostatic panic who participated in a CBT study, improvement in PTSD was partially mediated by improvement in orthostatic panic severity.

Various findings of the present study (viz., elevated CAPS scores among OP patients; high rates of orthostatic panic among PTSD patients vs. much lower rates among non-PTSD patients; the mediational role of OP severity in respect to PTSD severity; improvement in PTSD mediated by improvement in OP severity) suggest orthostatic panic to be an important aspect of trauma-related disorder in the Cambodian refugee population. In assessing trauma-related illness in the Cambodian population, one should determine whether orthostatic panic is present in order to attain content validity [Keane et al., 1996, pp. 187, 193]. Content validity refers to a measure’s adequacy in profiling all dimensions of a construct, and in the case of trauma-related disorder in the Cambodian population, orthostatic panic is a central distress dimension. In our clinic, we have found OP severity to be one of the most sensitive indicators of psychological status. The present study suggests that orthostatic panic partially mediates the relationship between anxious–depressive distress and PTSD pathology. (In addition, anxious–depressive distress would be expected to have a direct effect on PTSD severity, not mediated by orthostatic panic; this direct path is shown in Figure 2. Other mediators, not depicted in the model, may also be involved.) Consequently, the clinician treating Cambodian refugees with PTSD should target orthostatic panic in order to reduce PTSD pathology. We have shown such an approach to be effective in treating Cambodian refugees [Hinton et al., 2005a].

The present study indicates that among Cambodian refugees orthostatic panic (and dysphoria) is largely produced by orthostasis-related trauma recall and catastrophic cognitions. Researchers assessing orthostasis-induced dysphoria among English speakers having disorders such as chronic fatigue syndrome should investigate the role of orthostasis-associated trauma recall and catastrophic cognitions in producing orthostasis-related distress. The present study suggests that orthostasis-related distress in those disorders may result from catastrophic cognitions (e.g., a patient with chronic fatigue syndrome considering orthostasis-induced dizziness to indicate a profound and dangerous “weakening” of the body), and that orthostasis-related distress in former syndromes (e.g., DaCosta’s syndrome in the Civil War) may have resulted in part from syndrome-generated catastrophic cognitions (e.g., a sufferer of DaCosta’s syndrome––also called Soldier’s Heart––interpreting orthostatic symptoms as evidence of a weak and dilated heart) [on the concept of syndrome-generated catastrophic cognitions and ethnophysiology-generated catastrophic cognitions, see Hinton et al., 2006c, in press b,c]. The role of orthostasis-associated trauma associations in these current and former syndromes should also be investigated.

More generally, the present article raises the question of whether cultural syndromes in other groups, especially panic attack–type cultural syndromes––e.g., ataque de nervios among Hispanic patients [Cintrón et al., 2005; Guarnaccia and Rogler, 1999; Hinton et al., in press b]––may also play a mediating role between general anxious–depressive distress and PTSD severity (and other types of psychopathology). Future studies should investigate whether this is true, and whether these cultural syndromes need to be specifically addressed in treatment.

The “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” should be useful to clinicians who wish to explore and to treat a patient’s panic attacks, and to delineate the relationship of those panic attacks to anxious–depressive dysphoria and PTSD severity. The present study focused on orthostatic panic attacks among Cambodian refugees. But the model can be applied to cultural groups that have high rates of a certain panic attack subtype, or to a particular patient having the frequent occurrence of a certain panic attack subtype. The model is also useful when assessing the general predisposition to panic attacks for a particular patient or patient group: the total severity the “TCMI”-type dysphoria networks concerning somatic and psychological symptoms of anxiety should be predictive of predisposition to panic attacks. (As discussed above, the ASI would be one way to quickly assess the degree of “fear of anxiety symptoms” that results from TCMI-type dysphoria networks [Hinton and Otto, 2006].) The Panic Attack–PTSD Model is a useful heuristic to explore the generation of panic attacks, and the relationship to PTSD severity; such knowledge will give insights into how to design treatment (e.g., reducing anxious–depressive distress through relaxation techniques; modifying catastrophic cognitions; and eliciting trauma associations). For an illustration of how the model can lead to important treatment interventions among patients with PTSD and comorbid panic attacks, see Hinton et al. [2005a].

The present study provides support for components of the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model,” namely, trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions. However, some components of the model, such as metaphoric associations and direct interoceptive conditioning fear and symptoms of autonomic arousal, were not assessed. Also, ideally we would have included a pure measure of negative affectivity. Moreover, we did not prove a causal relationships in the present study, but rather illustrated that certain model variables explained variance beyond a measure of anxious–depressive distress (i.e., the SCL) and that the decrease in orthostatic panic mediated CBT improvement. To further assess the “Panic Attack–PTSD Model” as applied to OP, a future study should prospectively monitor OP severity along with other model variables, serially assessing OP severity and CAPS severity during CBT to establish whether OP improvement precedes CAPS improvement or whether instead CAPS improvement precedes OP improvement. A future study should have a dismantling design to see how much a treatment targeting just OP improves PTSD; the study should assess OP and PTSD at multiple time points to investigate whether improvement in OP precedes improvement in PTSD severity. A larger study should investigate the model variables through structural equation modeling. A future study should examine bidirectional, looping-type effects: OP not only as being caused by anxious–depressive distress, but also causing it, and PTSD not only as being caused by anxious–depressive distress, but also as causing it. Longitudinal studies can explore these bidirectional effects. Such bidirectional effects may differ through time: differences between the initial phase in which PTSD and OP initially worsen as compared to a chronic phase when both these conditions have reached a certain level of severity. In addition, because the current study the patients in the current study came from the first author’s caseload, one cannot exclude demand effects and other such variables on the results. As a related problem, given that the patients were all from the first author’s caseload, there was not optimal blindness to OP severity during assessment of orthostatic flashbacks and catastrophic cognitions. But given the number of patients on the first author’s caseload, and that OP severity varies in a particular patient from month to month, it is unlikely the first author would be aware of the OP severity for a particular patient.

Future studies need to explore panic-type comorbidities (panic attack, panic disorder, orthostatic panic) in patients with PTSD across cultures, and to do so using a continuous measure of PTSD severity so that the rate of the comorbidities can be compared across patients with a similar severity of PTSD. According to the Panic Attack–PTSD Model, the rate of panic attacks (and panic disorder) in trauma victims will be greater if the group has extensive negative associations to autonomic arousal sensations (e.g., extensive catastrophic cognitions), and the rate of subtypes of panic attacks (e.g., gastrointestinal-focused, startle-induced, exercise-induced) will vary depending on the extent of negative appraisal of and association to autonomic arousal sensations. The model also predicts that processes increasing anxious–depressive dysphoria, such as generalized anxiety disorder, will also impact on the rate of panic attacks, which will then amplify the effects on PTSD-type distress. The role of panic attacks in maintaining PTSD, and the importance of decreasing panic attacks in treatment, needs to be explored in other cultural groups. The Panic Attack–PTSD suggests the psychopathological processes that generate distress and how to devise treatments.

References

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky AJ. Panic disorder, palpitations, and awareness of cardiac activity. J of Nerv and Ment Dis. 1994;182:63–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199402000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M, Mineka S, Barlow DH. A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:4–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis G. Posttraumatic stress disorder: The etiological specificity of wartime stressors. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:578–583. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:339–376. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob C, Roitblat HL, Hamada RS, Carlson JG, Twentyman CT. A cognitive-action theory of post-traumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1988;2:253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cintrón JA, Carter MC, Suchday S, Sbrocco T, Gray J. Factor structure and construct validity of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index among island Puerto Ricans. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24:461–470. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, Broyles S, Borden JW, Watkins PL. Validity and reliability of the panic attack symptom and cognitions questionnaire. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1990;12:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- DaCosta JM. On irritable heart: A clinical study of a form of functional cardiac disorder and its consequences. Am J Med Sci. 1871;61:17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti SA, Resnick HS. Frequency and severity of panic attack symptoms in a treatment seeking sample of trauma victims. J Trauma Stress. 1997;4:683–689. doi: 10.1023/a:1024810206381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti SA, Resnick HS. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD with panic attacks. J Contemp Psychother. 2000;30:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY: 1995. p. 10032. Patient. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Functional cardiovascular disease. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins Company; 1947. p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Furman JM, Jacob RG. A clinical taxonomy of dizziness and anxiety in the otoneurological setting. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15:9–26. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Rogler LH. Research on culture-bound syndromes: New directions. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1322–1327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Ba P, Peou S, Um K. Panic disorder among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic: Prevalence and subtypes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00102-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Fama J, Pollack MH, McNally RJ. Gastrointestinal-focused panic attacks among Cambodian refugees: Associated psychopathology, flashbacks, and catastrophic cognitions. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Hofmann SG, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Dizziness- and palpitations-predominant orthostatic panic: Physiology, flashbacks, and catastrophic cognitions. J Psychopathol Behav Assess in press a. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Pollack MH, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in Cambodian refugees using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: Psychometric properties and symptom severity. J Trauma Stress. 2006a;19:405–411. doi: 10.1002/jts.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Safren SA, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH. A randomized controlled trial of CBT for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A cross-over design. J Trauma Stress. 2005a;18:617–629. doi: 10.1002/jts.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Um K, Fama JM, Pollack MH. Neck-focused panic attacks among Cambodian refugees; A logistic and linear regression analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2006b;20:119–138. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pollack MH. Rates of panic attacks, panic attack subtypes, and panic disorder among Cambodian refugees with PTSD. 2007 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chong R, Pollack MH, Barlow DH, McNally RJ. Ataque de nervios: Relationship to anxiety sensitivity and dissociation predisposition. Depress Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20309. in press b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Otto MW. Symptom presentation and symptom meaning among traumatized Cambodian refugees: Relevance to a somatically focused cognitive-behavior therapy. Cogn Behav Pract. 2006;13:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Park L, Pollack MH. Anxiety Presentations among East and Southeast Asians. Depress Anxiety in press c. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Safren SA, Pollack MH, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity among Cambodian refugees with panic disorder: A discriminant function and factor analytic investigation. Behav Res Ther. 2005b;43:1631–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Safren SA, Pollack MH, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity among Cambodian refugees with panic disorder: A factor analytic investigation. J Anxiety Disord. 2006c;20:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, So V, Pollack MH, Pitman RK, Orr SP. The psychophysiology of orthostatic panic in Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pollack MH, Pich V, Fama JM, Barlow DH. Orthostatically induced panic attacks among Cambodian refugees: Flashbacks, catastrophic cognitions, and associated psychopathology. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005c;12:301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. Physiological and psychological responses to stress in neurotic patients. J Ment Sci. 1948:392–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.94.395.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC, Barlow DH. The etiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990;10:299–328. [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Kaloupek DG, Weathers FW. Ethnocultural considerations in the assessment of PTSD. In: Marsella A, Friedman M, Gerrity E, Scurfield R, editors. Enthnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. 1995. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan B. The Pol Pot regime: Race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. Report upon soldiers returned as cases of ‘disordered action of the heart’ (DAH) or ‘valvular disease of the heart’ (VDH); Medical Research Committee; 1917. Special Series, No. 8. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman T, Randolf C, Brawman-Mintzer O, Flores L, Milanes F. Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1568–1574. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.11.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Wyshak G, Marneffe D, Khuon F, Lavelle J. Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: A screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:497–500. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Mcinness K, Poole C, Tor S. Dose-effect relationships of trauma to symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among Cambodian survivors of mass violence. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:482–488. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Bryant RA. Induced arousal and reexperiencing in acute distress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Hinton DE, Korbly NB, Chea A, Ba P, Gershuny BS, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among Cambodian refugees: Combination treatment with sertraline and cognitive-behavior therapy vs. sertraline alone. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckerman A, Dahl K, Chemitiganti R, LaManca JJ, Ottenweller JE, Natelson BH. Effects of posttraumatic stress disorder on cardiovascular stress responses in Gulf War veterans with fatiguing illness. Auton Neurosciences Basic Clin. 2003;108:63–72. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(03)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe P, Calkins H. Neurally mediated hypotension and chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Medicine. 1998;105:15S–21S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schondorf R, Freeman R. The importance of orthostatic intolerance in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:117–123. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scupi BS, Benson BE, Brown LB, Uhde TW. Rapid onset: A valid panic disorder criterion? Depress Anxiety. 1997;5:121–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)5:3<121::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerritt PW. Anxiety and the heart: A historical review. Psychol Med. 1983;13:17–25. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JA, Powers MB, Cho Y, Telch MJ. Mechanisms of change in cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: Evidence for the fear of fear mediational hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:646–652. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C, Brown G. Some observations on the validity of the Schneider test. J Aviat Med. 1944;13:214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Understanding and treating panic disorder. West Sussex, England: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Keane T, Davidson J. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw R. A review of the physical condition of 130 returned soldiers suffering from the effort syndrome. Med J Aust. 1939;16:891–893. [Google Scholar]