Abstract

The objective of this paper is to profile the role of homelessness in drug and sexual risk in a population of young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Data are from a cross-sectional survey collected between 2000 and 2001 in New York City (N = 569). With the goal of examining the import of homelessness in increased risk for the onset of drug and sexual risk, we compare and contrast three subgroups: (1) YMSM with no history of homelessness, (2) YMSM with a past history of homelessness but who were not homeless at the time of the interview, and (3) YMSM who were currently homeless. For each group, we describe the prevalence of a broad range of stressful life events (including foster care and runaway episodes, involvement in the criminal justice system, etc.), as well as selected mental health problems (including past suicide attempts, current depression, and selected help-seeking variables). Additionally, we examine the prevalence of selected drug and sexual risk, including exposure to a broad range of illegal substances, current use of illegal drugs, and prevalence of lifetime exposure to sex work. Finally, we use an event history analysis approach (time–event displays and paired t-test analysis) to examine the timing of negative life experiences and homelessness relative to the onset of drug and sexual risk. High levels of background negative life experiences and manifest mental health distress are seen in all three groups. Both a prior experience of homelessness and currently being homeless are both strongly associated with both higher levels of lifetime exposure to drug and sexual risk as well as higher levels of current drug and sexual risk. Onset of these risks occur earlier in both groups that have had an experience of housing instability (e.g., runaway, foster care, etc.) but are delayed or not present among YMSM with no history of housing instability. Few YMSM had used drug prior to becoming homeless. While causal inferences are subject to the limitations of a cross-sectional design, the findings pose an empirical challenge to the prevailing assumption that prior drug use is a dominant causal factor in YMSM becoming homeless. More broadly, the data illustrate the complexity of factors that must be accounted for, both in advancing our epidemiological understanding of the complexity of homelessness and its relationship to the onset of drug and sexual risk among high risk youth populations.

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly young men who have sex with men (YMSM), continue to figure prominently in the spread of HIV infection, both in New York City (NYC) and in many areas of the United States (c.f., Waldo, McFarland, Katz, MacKellar, & Valleroy, 2000). For example, recent population-based estimates of incident HIV infections in NYC indicate significantly higher rates than previously recognized (Nash, Manning, & Ramaswamy, 2004). Nearly two-thirds of the new infections (65%) were male, and overall the data show significantly higher rates among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks. These increases are especially troubling because they follow a period of steadily declining rates of new infection among MSM, and suggest that existing prevention programming is not working, particularly in younger MSM cohorts. Among the factors contributing to this renewal in the growth of HIV infection rates in MSM populations, drug abuse has emerged as a significant contributing factor, both in relation to sexual risk as well as in the context of injection-mediated transmission risk (c.f., Thiede et al., 2003).

Similarly, the available epidemiological literature on homeless youth populations shows that drug and sexual risk are prevalent in this population (c.f., Kipke, Montgomery, & MacKenzie, 1993; Allen et al., 1994; Rotheram-Borus, Hunter, & Rosario, 1994; Bailey, Camlin, & Ennet, 1998; Clatts & Davis, 1999; Greene, Ennett, & Ringwalt, 1999; Lifson & Halcon, 2001; Cochran, Steward, Ginzler, & Cauce, 2002; Roy et al., 2003). A number of these studies have also highlighted the prevalence of a host of early negative life events among homeless youth, and noted that they are strongly correlated with drug abuse, particularly in homeless YMSM (Kipke et al., 1993; Sibthorpe, Drinkwater, Gardner, & Bammer, 1995; Rotheram-Borus, Mahler, Koopman, & Langabeer, 1996; Greene, Ennett, & Ringwalt, 1997; Kral, Molnar, Booth, & Watters, 1997; Clatts, Davis, Sotheran, & Atillasoy, 1998; Gleghorn, Marx, Vittinghoff, & Katz, 1998; Martinez et al., 1998; Molnar, Shade, Kral, Booth, & Watters, 1998; Ringwalt, Greene, & Robertson, 1998; Lock & Steiner, 1999; Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Bao, 2000; Noell & Ochs, 2001; Cochran et al., 2002; Roy et al., 2003). YMSM, notably a group that is overrepresented within the homeless youth population as a whole, are of particular concern in relation to risk for HIV infection because they have high risk behavioural interactions with two adult populations with high background seroprevalence of HIV infection, including adult MSM and adult injection drug users (IDUs) (Robertson, 1992; Kipke, O’Connor, Palmer, & Mackenzie, 1995; Bailey et al., 1998; Clatts & Davis, 1999).

While the high prevalence of negative life events among homeless youth is well documented, longitudinal studies of homeless youth populations are scant, and much of the available literature is based on cross-sectional data derived from treatment and quasi-treatment settings. While the preponderance of this evidence shows that the lives of these youth is fraught with multiple sources of adversity, it is unclear in the available data where the onset of drug abuse is situated in the life course, and where it is situated relative to other sources of risk, and hence what antecedent role, if any, drug abuse may play in establishing risk trajectories and poor health outcomes among YMSM.

Based on data collected in a controlled comparison, epidemiological study of YMSM in NYC, this paper describes the prevalence and timing of a wide range of stressful life events, including housing instability. Included in this array of stressful life events are a selected set of mental health markers. We also show the prevalence and timing of selected high risk behaviours, including the onset of both drug use and sexual risk, with the overall goal of illuminating the role of homelessness in increasing risk for negative health outcomes among YMSM.

Methods

Data collection was initiated in September of 2000 and completed in May of 2001. With the explicit goal of building theoretical sources of variability in the sample, subjects were recruited using a targeted sampling approach that included a wide variety of natural settings in which young men who have sex with men congregate (Watters & Biernacki, 1989; Clatts, Davis, & Atillasoy, 1995). Settings were identified during a year long community assessment process, and included a wide range of venues MSM use for finding sexual partners (e.g., public sex locations, public parks, etc.), venues used for establishing a commercial sex transactions (e.g., male prostitution areas, “hustler” bars, etc.), as well as venues in which YMSM gather for more general social interactions (e.g., bars, clubs, etc.). Recruitment venues were scheduled at random to reduce potential sampling biases. The participants in the overall sample were recruited in bars, clubs, and cafes (32%), outdoor “street hangouts” and parks (42%), indoor and outdoor “hustling” venues (16%), and community-based agencies serving high risk youth (10%).

Interviewers approached young males and asked if they would participate in a brief health survey. Those who agreed to participate were brought to a more private setting in the immediate vicinity and assessed for eligibility using a set of screener questions constructed to both establish eligibility and mask study criteria. Eligibility was restricted to young men between the ages of 17 and 28 years who reported sexual contact with a male partner in the previous six months. Approximately 80% of the eligible respondents agreed to participate. The structured interview lasted about an hour and usually occurred on the same day youth were recruited and screened. The interview was translated into Spanish by a certified translator and back-translated to insure accuracy. Two percent of the interviews took place in Spanish and most interviewers were bilingual in English and Spanish. All but two participants completed the interview and there was little missing data. Youth received $25 for their participation. The study procedures were approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of the National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., including approval to enroll 17 year olds without parental consent.

A total of 569 YMSM completed the interview protocol which was conducted using a face-to-face computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) format. Domains included demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race), sexual identity and gender affinity, familial socio-economic status, educational attainment, history of housing instability (including experience in foster care and runaway episodes), involvement with the criminal justice system, exposure to violence and victimization, mental health status (including history of suicide, current level of depression symptomology, and help-seeking), both lifetime exposure to and current use of illegal drugs, and help-seeking activities.

We describe the overall sample, highlighting similarities and differences between the three comparison groups of interest for this analysis: (1) YMSM with no history of homelessness (56%, N = 320); (2) YMSM with a past history of homelessness (but who were not homeless at the time of the interview) (29%, N = 166); and (3) YMSM who were homeless at the time of the interview (15%, N = 83). We compare each of the three groups in relation to relative risk for a wide range of negative events (including housing instability and homelessness) as well as subsequent poor health outcomes (including exposure to and ongoing use of a wide range of illegal drugs and sex work). Finally, we describe the onset and sequence of negative life events among each group. We initially conducted a series of multivariate logistic regression analyses using drug use (both specific drugs and classes of drugs) as the outcome variables. However, these analyses did not yield consistent good fitting logistic models predicting drug use. Therefore, we present time–event displays and paired t-test analyses to illustrate the trajectories of homelessness, drug use and sexual risk (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and within subjects analyses (t-test and p-value) about age of onset of negative events and drug use

| Foster | Runaway | Group home |

Suicide | Police contact |

Jail | Sex work |

Crack | Coke | Heroin | Club drugs |

IDU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster | 60 | 54 | 39 | 70 | 53 | 64 | 27 | 33 | 21 | 36 | 12 | |

| Runaway | 5.86** | 75 | 93 | 149 | 99 | 120 | 51 | 109 | 40 | 118 | 25 | |

| Group home | 7.52** | 2.45* | 39 | 81 | 61 | 60 | 29 | 44 | 19 | 51 | 11 | |

| Suicide | 6.95** | 1.23 | −0.73 | 99 | 63 | 84 | 29 | 73 | 28 | 96 | 21 | |

| Police contact | 10.81** | 6.25** | 1.89 | 3.76** | 158 | 147 | 67 | 124 | 54 | 148 | 30 | |

| Jail | 10.59** | 9.91** | 4.00** | 5.78** | 6.57** | 108 | 53 | 91 | 44 | 93 | 22 | |

| Sex work | 12.88** | 10.29** | 5.26** | 7.61** | 5.90** | 1.44 | 68 | 105 | 51 | 112 | 35 | |

| Crack | 8.86** | 6.88** | 6.51** | 3.46* | 6.42** | 2.16 | 2.69* | 69 | 38 | 58 | 20 | |

| Coke | 9.14** | 8.90** | 5.41** | 7.78** | 6.57** | 0.08 | −0.16 | −3.26* | 55 | 175 | 28 | |

| Heroin | 8.45** | 6.49** | 3.75** | 4.57** | 6.85** | 0.89 | 0.40 | −1.50 | 4.63** | 51 | 27 | |

| Club drugs | 10.83** | 10.84** | 7.33** | 10.49** | 7.81** | 1.78 | 2.26 | −0.78 | 0.43 | −1.08 | 28 | |

| IDU | 4.01** | 5.17** | 2.30 | 5.34** | 3.54** | 1.07 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.34 | 2.71 | 0.00 |

p<0.001.

p<0.01

Results

YMSM sample characteristics

Age and ethnicity

YMSM in the sample ranged from 17 to 28 years of age (M = 21.7, SD = 2.9). The three subgroups are relatively equally distributed in relation to age. The three groups differ in relation to ethnicity. Past homelessness is distributed across all four major racial groups, including African-Americans (23%), Hispanics (49%), Whites (21%), and other groups (8%). Similarly, current homelessness is widely distributed across all four groups, African-Americans (27%), Hispanics (53%), Whites (8%), and Others (12%). However, significant differences are seen among the three racial groups in relation to both past and current homelessness (χ2 = 31.96, p<0.001). Hispanics are more than twice as likely than Whites or African-Americans to have been homeless in the past. Similarly, Hispanics are almost seven times more likely than Whites, and almost twice as likely as African-Americans, to be currently homeless (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subgroups—never, past, and current homeless YMSM

| Never | Past | Current | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 21.8 (2.9) | 21.6 (2.9) | 21.4 (2.9) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White (%) | 34.7 | 20.5 | 8.4 |

| Black (%) | 21.6 | 22.9 | 26.5 |

| Hispanic (%) | 32.8 | 48.8 | 53.0 |

| Other (%) | 10.9 | 7.8 | 12.0 |

| Sexual identity | |||

| Gay/homosexual (%) | 74.4 | 56.0 | 36.1 |

| Bisexual (%) | 17.8 | 29.5 | 34.9 |

| Heterosexual (%) | 3.4 | 7.2 | 21.7 |

| Other (%) | 4.4 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| Transgender (%) | 6.6 | 7.8 | 19.3 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Mean score* | 39.2 (16.7) | 32.9 (16.8) | 31.9 (15.3) |

| Lower below median** (%) | 42.5 | 57.0 | 58.4 |

| Medium through high completed grade 12 (GED) (%) | 87.0 | 68.1 | 43.3 |

| Violence | |||

| Ever physically attacked (%) | 18.4 | 42.2 | 55.4 |

| Sexual orientation related suicide attempts (%) | 36.2 | 32.4 | 36.4 |

| Ever (%) | 26.6 | 41.8 | 43.4 |

| Multiple attemptsa (%) | 37.6 | 53.6 | 55.6 |

| Depression (CES-D)* | 5.8 (5.3) | 9.5 (6.3) | 11.9 (6.8) |

| Drug treatment | |||

| Detoxification (%) | 1.9 | 7.2 | 13.3 |

| Residential (%) | 0.9 | 5.4 | 7.2 |

| Outpatient (%) | 1.9 | 7.8 | 7.2 |

Mean (standard deviation).

Median score = 37.

Multiple suicide attempts were a percent of those reporting any suicide attempt.

Sexual and gender identity

The study was limited to a behaviourally defined population of males who self-reported a sexual exchange with another male within the past 6 months. Overall, most identify as “Gay” (63%), with smaller proportions identifying as bisexual (24%) or heterosexual (7%). A minority (6%) declined to self-identify with any of these categories. Differences in identity are statistically significant among the three housing status groups (χ2 = 61.17, p<0.001). A minority (9%) are Transgender, 42% of whom had never been homeless, 26% of whom had been homeless in the past, and 32% of whom were currently homeless.

Socio-economic status and education attainment

Using a series of questions based on the Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975), YMSM were asked about their families’ socio-economic status. YMSM with no history of homelessness have a higher mean score than either those with past homelessness or current homelessness. We were unable to locate data that would allow us to situate these scores within those shown in general youth and young adult populations. However, in comparing the three groups with one another, significant differences are seen between the never homeless and those with either past or current homelessness (t = 3.45, p<0.001), as well as between past and current homeless (t = 3.81, p<0.001).

Similar differences are seen in relation to educational attainment. Among the 366 currently out of school, 26% competed up to grade 11, 74% completed up to grade 12 or had a graduate equivalency diploma. Having completed grade 12 (or earned an equivalency degree) is significantly less common in the both past and current homelessness groups than among the never homeless. The majority (87%) of the never homeless completed grade 12 or had a GED, while only two thirds (68%) of the past homeless group, and less than half (43%) of the current homeless group, had done so (χ2 = 48.47, p<0.001).

Exposure to violence/victimization

Exposure to violence and victimization is prevalent across the sample. Nearly a third (31%) report exposure to violence, and over a third of these associate their exposure with their sexual identity. No significant differences are seen in risk for exposure across the never, past and current housing status groups.

Mental health indicators

Relatively high levels of a history of suicide are evident in the sample as a whole, with over a third (34%) reporting at least one suicide attempt and nearly half (47%) of these reporting multiple attempts. However, a history of suicide, multiple suicide attempts, and age of first suicide, are all distributed differently in the three comparison groups. Only about one quarter of the never homeless have attempted suicide, while 42% of the past homeless group and 43% of the current homeless group have at least one suicide attempt (χ2 = 15.48, p<0.001). These patterns were also reflected the distribution of multiple suicide attempts, with only about a third of the attempters is the never homeless group having made multiple attempts, while over half of the attempters in the past homeless and current homeless groups (38%, 54%, 56%, respectively) have made multiple suicide attempts. The never homeless group were less likely to report multiple suicide attempts than the past homeless group and the current homeless group (χ2 = 3.83, p<0.05; χ2 = 3.31, p = 0.06; respectively).

Using the short form (8 items) of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Huba, Melchior, Staff of The Measurement Group, & HRSA/HAB’s SPNS Cooperative Agreement Steering Committee, 1995), we assessed current depression as a general marker for psychological distress. With a normative score of seven or greater considered clinically significant, the overall sample evidences excessive levels of depression. The mean score for the overall sample is 7.8 and half (50%) have a score of seven or more. Significant differences are found among the three groups (F = 45.85, p<0.001). YMSM who are currently homeless are more likely to evidence clinically significant depression than the past homeless group and much more likely than the never homeless group (t = 2.73, p<0.01; t = 8.68, p<0.001; respectively).

Help seeking

Particularly striking given the high rates of distress, clinical depression, and drug use, YMSM report relatively low rates of help-seeking. For example, only 5% had entered a drug detoxification program, only 3% had been in residential treatment, and only 4% had been in outpatient treatment. Moreover, less than two-thirds of those who had entered treatment, completed the program (58%). As might be expected given their greater rates of exposure, past and current homeless are more likely to have been in a detoxification program, residential treatment program, or outpatient program (χ2 = 19.8, p<0.001; χ2 = 12.4, p<0.01; χ2 = 11.0, p<0.01; respectively). However, the fact that the higher risk group is more likely to have been exposed to treatment must be tempered with the recognition that relatively low overall treatment rates are seen in the sample as a whole. Moreover, given the high rates of non-completion observed in YMSM, it is unclear what types of clinically therapeutic treatment may have actually been achieved. Parenthetically, we noted in our earlier ethnographic interviews with YMSM in this study that youth consistently cited their sexuality as a problem in both accessing drug treatment and remaining in drug treatment.

Prevalence and distribution of homelessness and drug abuse among YMSM

Lifetime and current drug use

Overall, the sample evidences high levels of exposure to a broad range of illegal drugs, including marijuana (82%), crack-cocaine (15%), powder cocaine (39%), heroin (13%), speed (23%), MDMA (50%), ketamine (29%), and hallucinogens (28%). 7% (N = 39) report lifetime exposure to injection drug use. YMSM also report high rates of current use of one or more of these substances, including marijuana (60%), crack-cocaine (6%), powder cocaine (15%), heroin (4%), Speed (9%), MDMA (22%), ketamine (10%), and hallucinogens (2%). Additionally, 3% of the overall sample report current use of injection as a mode of drug administration (IDU). Rates of both lifetime exposure and current drug use are not equally distributed in the sample.

Never homeless—Lifetime and current drug use

High rates of lifetime exposure to drug are seem in YMSM with no history of homelessness, including powder cocaine (28%), Speed (20%), MDMA (47%), and ketamine (28%). Few (3%) report lifetime exposure to IDU. Substantial numbers of the never homeless YMSM also report ongoing (current) use of many of these substances, including powder cocaine (13%) and MDMA (22%).

Past homeless—Lifetime and current drug use

YMSM with a past history of homelessness evidence higher levels of exposure to illegal drugs, including crack-cocaine (22%), powder cocaine (60%), heroin (20%), Speed (29%), MDMA (60%), ketamine (34%), and hallucinogens (41%). Twelve percent report lifetime exposure to IDU. In comparing the never homeless group with those YMSM with a past history of homelessness, the past homeless group is significantly more likely to have lifetime exposure to wide array of drugs, including marijuana, crack-cocaine, powder cocaine, heroin, speed, MDMA, hallucinogens, IDU. With respect to current drug use, the past homeless YMSM are more likely than those with no history of homelessness to be currently using marijuana, crack cocaine, powder cocaine, heroin, and IDU (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of substance use

| Lifetime drug use | Current drug use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | χ2 | % | χ2 | |||||

| N-P | N-C | P-C | N-P | N-C | P-C | |||

| Marijuana | 13.0*** | 4.3* | 0.5 | 25.4*** | 8.3** | 0.9 | ||

| Never homeless | 76.0 | 46.2 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 89.7 | 70.3 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 86.6 | 64.2 | ||||||

| Crack | 23.7*** | 49.7*** | 5.5* | 4.8* | 30.4*** | 8.1** | ||

| Never homeless | 6.7 | 1.9 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 22.0 | 6.1 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 36.4 | 17.7 | ||||||

| Coke | 45.6*** | 5.6* | 7.0** | 4.7* | 0.7 | 0.5 | ||

| Never homeless | 28.0 | 12.3 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 59.9 | 19.5 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 41.8 | 16.3 | ||||||

| Heroin | 22.5*** | 32.7*** | 1.7 | 8.9** | 27.4*** | 4.1* | ||

| Never homeless | 5.8 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 20.0 | 6.1 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 27.5 | 13.8 | ||||||

| Speed | 4.1* | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.03 | 0.3 | ||

| Never homeless | 20.1 | 7.9 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 28.5 | 10.4 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 23.1 | 7.6 | ||||||

| MDMA | 6.9** | 3.3 | 12.3*** | 0.9 | 1.6 | 3.2 | ||

| Never homeless | 46.8 | 19.9 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 59.5 | 23.1 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 35.4 | 15.0 | ||||||

| Ketamine | 1.7 | 1.6 | 4.1* | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.8 | ||

| Never homeless | 27.8 | 11.3 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 33.5 | 8.6 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 20.8 | 5.1 | ||||||

| Hallucinogen | 25.9*** | 9.4** | 0.7 | 2.9 | 8.2** | 1.1 | ||

| Never homeless | 19.3 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 41.1 | 2.4 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 35.4 | 5 | ||||||

| IDU | 16.8*** | 20.2*** | 0.5 | 10.3*** | 26.2*** | 2.9 | ||

| Never homeless | 2.5 | 0.3 | ||||||

| Past homeless | 11.5 | 3.6 | ||||||

| Current homeless | 14.6 | 9.6 | ||||||

N, Never homeless group; P, past homeless group; C, current homeless group.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Current homeless—Lifetime and current drug use

Relative to the never homeless and past homeless groups, currently homeless evidence still greater prevalence of lifetime exposure to current use of drugs, including crack cocaine (36%), powder cocaine (42%), heroin (28%), Speed (23%), MDMA (35%), ketamine (21%), and hallucinogens (35%). An alarming 15% of the currently homeless group report some kind of lifetime exposure to IDU. Moreover, currently homeless YMSM report higher levels of ongoing (current) use of many of these substances, including crack-cocaine (18%), powder cocaine (16%), heroin (14%), Speed (8%), and MDMA (15%). 10% of the currently homeless group report current IDU. YMSM who are currently homeless are more likely than those who have never been homeless to be currently using crack-cocaine, heroin, and IDU. YMSM who are currently homeless are more likely than those with a past history of homelessness to be currently using crack-cocaine, powder cocaine, heroin, and IDU.

Timing and order of negative events in relation to the onset of drug use

Having established that high levels of lifetime and current drug use are prevalent among YMSM, particularly among currently homeless YMSM, we examined the timing and onset of drug abuse relative to the timing of other negative life events across these three groups. Here we use age of onset data to provide three types of comparisons: First, we show the order in which each negative life event occurs in relation to chronological age; second, we show the order in which these events occur relative to one another; and third we show how these events are distributed across the three housing status groups. Events included in the trajectory include first exposure to foster care, first runaway experience, first time living in a group home, first involvement with the police or arrest, first incarceration, first involvement in sex work, first exposure to a wide range of illegal drugs, and first injection drug use.

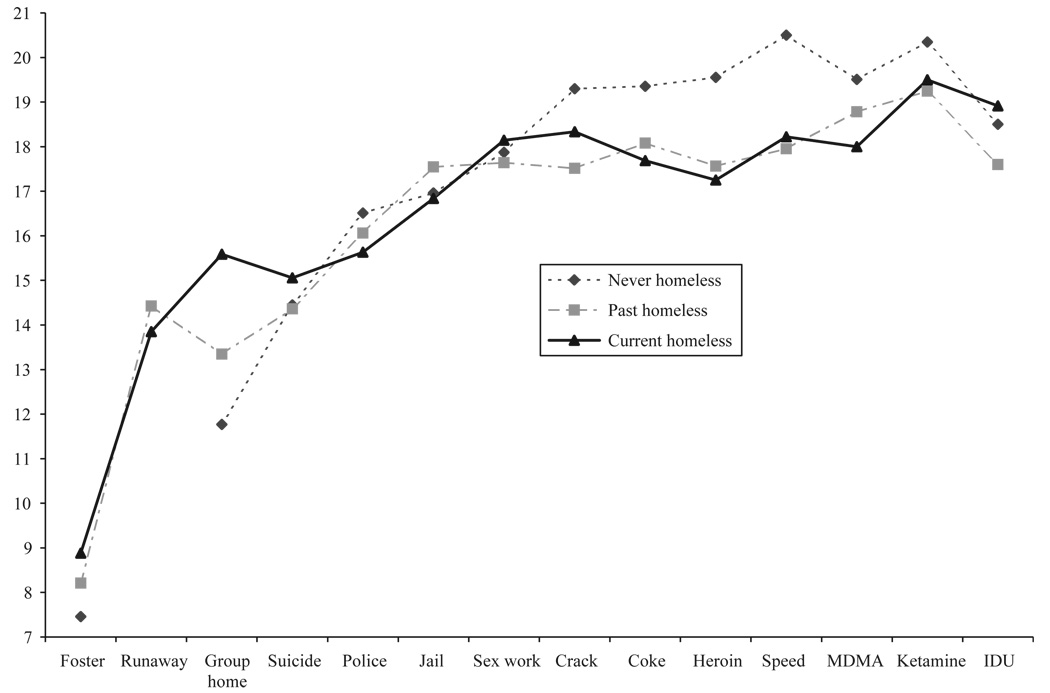

The trajectory data show that the timing of negative events occurs in a relatively consistent order, notably one that betrays many of the assumptions in the existing homeless youth literature which poses negative behavioural practices such as involvement in drug use or sex work as a causal factor in youth becoming homeless. Across all three groups, the data show a consistent temporal pattern (see Fig. 1) in which a constellation of negative life events occur before the onset of both drug use and sex work. Moreover, negative outcomes occur earlier for the two groups with exposure to homelessness relative to the group with no exposure to homelessness. For both the past homeless and current homeless groups, foster care, running away from home, and living in a group home, on average, all occur at the earliest chronological ages (mean ages of 8.6, 14.2, 14.5, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Life trajectory of onset of negative events.

Multiple suicide attempts are more prevalent among the two homeless groups and also occur, on average, at age of 14.4 for the never homeless, age 14.4 for the past homeless, and 15.1 for the current homeless. Involvement in the criminal justice system occurs next in the trajectory, as indicated by the onset of interactions with police at a mean age of 16.5 for the never homeless and 16.1 and 15.6, respectively, for the past homeless and current homeless groups. As expected, exposure to incarceration follows exposure to interactions with police in the trajectory, and on average, the current homeless reported earlier exposure to incarceration than the past homeless and never homeless groups (16.8, 17.5, 17, respectively). Again recalling that sex work is much more prevalent among the two homeless groups, onset of sex work typically follows the negative events described above, including exposure to housing instability, multiple suicide attempts, and involvement in the criminal justice system.

Within the sensitivity limitations of our measure, sex work and drug abuse appear at roughly contemporaneous points in the trajectory. Importantly, however, they both occur after exposure to a constellation of negative events such as housing instability, multiple suicide attempts, and incarceration. On average, the onset of sex work appears at age 17.9 in the never homeless group, at age 17.6 in the past homeless group, and age 18.1 in the current homeless group. Similarly, initiation of drug abuse typically follows all of these other types of negative events, including homelessness. For example, mean age of first exposure to crack-cocaine appears in the trajectory at age 19.3 in the never homeless group, at 17.5 in the past homeless group, and at 18.3 in the currently homeless group, with an average of 17.9. Cocaine appears at age 19.4 among the never homeless group, at 18.1 among the past homeless group, and at 17.7 among the currently homeless group, with an average of 18.0. Heroin appears at age 18.0 in the never homeless group, at 17.6 in the past homeless group, and 17.3 among the currently homeless group, with an average of 17.5. Speed appears at age 20.5 in the never homeless group, at 18.0 in the past homeless group, and at 18.2 in the currently homeless group, with an average of 18.1. MDMA appears at age 19.5 in the never homeless group, at 18.8 in the past homeless group, and at 18.0 in the currently homeless group, with an average of 18.4. Ketamine appears at age 20.3 in the never homeless group, at 19.2 in the past homeless group, and at 19.5 in the current homeless group, with an average of 19.3. Finally, initial exposure to injection drug use appears at 18.5 in the never homeless group, at 17.6 in the past homeless group, and at 18.9 in the currently homeless group, with an average of 18.2.

In order to empirically examine the temporal relationships between negative events, we conducted paired sample t-tests of all combinations of these events. In Table 3, we present the results of these comparisons. The upper right section of the table presents the sample size for each comparison, while the lower left section of the table presents the t-values and statistical significance (criteria = p<0.01). Overall, these results support the observation that negative events temporally precede the onset of sex work and drug use. Entering foster care preceded all other events; four events do not show a clear temporal relationship (running away, entering a group home, making a suicide attempt, and initial police contact), but each of these preceded all of the remaining events. The remaining events also do not show a clear temporal pattern, and all of these events (first time in jail, onset of sex work, and onset of use of different drugs) follow the association with unstable housing and family relationships described above.

Conclusions

There are a number of limitations to this study. Data were collected using a community based, targeted sampling approach and may not be formally representative of the YMSM population. Differences in the intervals between the onset of negative behaviours are in some cases modest. For example, the onset of both drug abuse and sex work occur in close temporal proximity, suggesting that they may be related in important ways that are not easily disentangled in the context of cross-sectional, retrospective data. More sensitive and comprehensive assessment, ideally in the context of a prospective study design, is needed to further illuminate these processes.

Despite these limitations, however, the data indicate that key sources of protective influence have failed this population. At a societal level, we expect that key social institutions—notably families, schools, the criminal justice system, and mental health services—serve as sources of support and protective influence in preventing exposure and accumulation of risks within the early life trajectories of youth and young adults. For example, and consistent with earlier studies of YMSM (Kruks, 1991; Remafedi, Farrow, & Deisher, 1991; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1994; Lock & Steiner, 1999; Noell & Ochs, 2001), these data show that high rates of suicide attempts and repeated suicide attempts are prevalent in YMSM, indicative of the fact that many of these young men are living with clinically significant and untreated psychological distress. Similarly, interactions with the criminal justice system and exposure to incarceration also occur frequently and early among YMSM, and yet have failed to deter progressive involvement in the street economy.

While onset of drug use is complex, the data show that few YMSM who have become homeless have used drugs prior to their becoming homeless. Moreover, and even in this high risk population, the onset of drug use is deferred or delayed among YMSM who have no history of housing stability or a past homeless experience. Thus, these data challenge the assumption that high rates of homelessness among YMSM may be substantially attributable to a prior and underlying problem with drugs. Similarly, these data challenge the assumption that high rates of involvement in illegal activities and the street economy, including sex work, can be causally attributed to an underlying and pre-existing problem with drugs. In short, both outcomes are better understood as adaptations to homelessness, rather than causes of it.

Clearly drug use is a critical issue for YMSM, and once established as a central behavioural adaptation, it may well become a critical factor in determining subsequent risk trajectory outcomes. Of particular concern are the high levels of injection drug use observed in this sample, both because of injection-mediated risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens such as HIV infection and more generally because injection may serve as a potent indicator that drug use has reached an acute level of severity and chronic dependence. As to the question of the origins of drug use, however, these data offer a compelling argument for understanding these behavioural risks not as artefacts of individual pathology, but rather as unintended medical consequences of YMSMs adaptation to homelessness, including the unmet internal and external needs which are characteristics of a homeless experience. While the sources of risk are many, and their relationship with one another increasingly complex, housing instability clearly plays a pivotal role in YMSM’s risk for exposure to drug and sexual risk as well as a formidable challenge to their management of risks. It logically follows then, that structural interventions—systemic approaches to more effective means of reaching, engaging, and retaining homeless YMSM in shelter services and permanent housing programs—should be central considerations in formulating HIV and other public health interventions targeted to this population.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11596), Michael C. Clatts, Ph.D., Principal Investigator. We would like to thank the young men who participated in the study. We would also like to acknowledge members of the staff: Kyle Ayers, Carlos Cortez, Jorge Cortias, Wil Edgar, Christian Kolarz, Steve Lankenau, Ph.D., Kalil Vicioso, and Salvador Vidal-Ortiz, and Dorinda Welle, Ph.D.

References

- Allen DM, Lehman JS, Green TA, Lindegren ML, Onorato IM, Forrester W. HIV infection among homeless adults and runaway youth, United States, 1989–1992. AIDS. 1994;8(11):1593–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Camlin CS, Ennet ST. Substance use and risky sexual behavior among homeless and runaway youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23:78–88. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Davis WR. A demographic and behavioral profile of homeless youth in New York City: Implications for AIDS outreach and prevention. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1999;10:105–114. doi: 10.1525/maq.1999.13.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Davis WR, Atillasoy A. Hitting a moving target: The use of ethnographic methods in the evaluation of AIDS outreach programs for homeless youth in NYC. Qualitative Methods in Drug Abuse and HIV Research: National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph. 1995;157:117–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Davis WR, Sotheran JL, Atillasoy A. Correlates and distribution of HIV risk behaviors among homeless youths in New York City: Implications for prevention and policy. Child Welfare. 1998;77(2):195–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Steward AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparisons of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):773–777. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleghorn AA, Marx R, Vittinghoff E, Katz MH. Association between drug use patterns and HIV risks among homeless, runaway, and street youth in northern California. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51(3):219–227. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL. Substance use among runaway and homeless youth in three national samples. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(2):229–235. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1406–1409. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven: Yale University, Department of Sociology; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Huba GJ, Melchior LA Staff of The Measurement Group, & HRSA/HAB’s SPNS Cooperative Agreement Steering Committee. Module 26B: CES-D8 Form (Interview) Culver City, CA: The Measurement Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Montgomery S, MacKenzie RG. Substance use among youth seen at a community-based health clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14:289–294. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90176-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, O’Connor S, Palmer R, Mackenzie RG. Street youth in Los Angeles: Profile of a group at risk for human immune virus infection. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1995;149:513–519. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170180043006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Molnar BE, Booth RE, Watters JK. Prevalence of sexual risk behaviour and substance use among runaway and homeless adolescents in San Francisco, Denver and New York City. International Journal of STD AIDS. 1997;8(2):109–117. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruks G. Gay and lesbian homeless/street youth: Special issues and concerns. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson AR, Halcon LL. Substance abuse and high-risk needle-related behaviors among homeless youth in Minneapolis: Implications for prevention. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(4):690–698. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.4.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Steiner H. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth risks for emotional, physical, and social problems: Results from a community-based survey. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):297–304. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez TE, Gleghorn A, Marx R, Clements K, Boman M, Katz MH. Psychosocial histories, social environment, and HIV risk behaviors of injection and noninjection drug using homeless youths. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Shade SB, Kral AH, Booth RE, Watters JK. Suicidal behavior and sexual/physical abuse among street youth. Child Abuse Negligence. 1998;22(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D, Manning SE, Ramaswamy C. Descriptive epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in New York City: Incorporation of newly available population-based surveillance data on HIV (non-AIDS), 2001. Presented at the 11th conference on retrovirus and opportunistic infections; San Francisco, CA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noell JW, Ochs LM. Relationship of sexual orientation to substance use, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and other factors in a population of homeless adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G, Farrow JA, Deisher RW. Risk factors for attempted suicide in gay and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 1991;87:869–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt CL, Greene JM, Robertson MJ. Familial backgrounds and risk behaviors of youth with thrownaway experiences. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21(3):241–252. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JM. Homeless and runaway youths: A review of the literature. In: Robertson MJ, Greenblat M, editors. Homelessness: A national perspective. New York: Plenum; 1992. pp. 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Hunter J, Rosario M. Suicidal behavior and gay-related stress among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1994;9:498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mahler KA, Koopman C, Langabeer K. Sexual abuse history and associated multiple risk behavior in adolescent runaways. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(3):390–400. doi: 10.1037/h0080189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Cedras L, Weber AE, Claessens C, et al. HIV incidence among street youth in Montreal, Canada. AIDS. 2003;17(7):1071–1075. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305020-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibthorpe B, Drinkwater J, Gardner K, Bammer G. Drug use, binge drinking and attempted suicide among homeless and potentially homeless youth. Australian New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;29(2):248–256. doi: 10.1080/00048679509075917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede H, Valleroy LA, MacKeller DA, Celantano DD, Ford WL, Hagan H, et al. Regional patterns and correlates of substance use among young men who have sex with men in 7 US urban areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(11):1915–1921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR, McFarland W, Katz MH, MacKellar D, Valleroy LA. Very young gay and bisexual men are at high risk for HIV infection: The San Francisco Bay Area Young Men’s Survey. Journal of AIDS. 2000;24(2):168–174. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36(4):416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development. 2000;71(3):721–732. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]