Abstract

IL-10 is essential for inhibiting chronic and acute inflammation by decreasing the amounts of proinflammatory cytokines made by activated macrophages. IL-10 controls pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production indirectly via the transcription factor Stat3. One of the most physiologically significant IL-10 targets is tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFalpha), a potent pro-inflammatory mediator that is the target for multiple anti-TNFalpha clinical strategies in Crohn’s Disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 seem to be mediated by several incompletely understood transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Here we show that in LPS-activated bone marrow-derived murine macrophages, IL-10 reduces the mRNA and protein levels of TNFalpha and IL-1alpha in part through the RNA destabilizing factor tristetraprolin (TTP). TTP is known for its central role in destabilizing mRNA molecules containing class II AU-rich elements in 3′ untranslated regions. We found that IL-10 initiates a Stat3-dependent increase of TTP expression accompanied by a delayed decrease of p38MAPK activity. The reduction of p38MAPK activity releases TTP from the p38MAPK-mediated inhibition thereby resulting in diminished mRNA and protein levels of proinflammatory cytokines. These findings establish that TTP is required for full responses of bone marrow-derived murine macrophages to IL-10.

Keywords: Monocytes/Macrophages, Cytokines, Inflammation

Introduction

One of the key players in immune homeostasis is interleukin 10 (IL-10), a cytokine that was discovered 18 years ago as a T cell-secreted factor that inhibited cytokine production by Th1 cells (1). Over the years it became clear that IL-10 is produced by many cell types including T and B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, keratinocytes or epithelial cells (2). It is generally considered that the main biological function of IL-10 is to limit or shut down inflammatory responses. This notion is supported by the phenotype of IL-10-deficient mice that develop severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) due to spontaneous chronic inflammation, and are susceptible to endotoxin treatment because of acute overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (3, 4). Many of these phenotypes can be recapitulated by T cell-specific deletion of the IL-10 gene indicating that T cell-derived IL-10 is primarily responsible for chronic inflammation (5). Under conditions of acute inflammation the main source of IL-10 are macrophages and dendritic cells (6). On the cellular level, IL-10 inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and regulates differentiation and proliferation of various immune cells. These effects depend entirely on the activation of the transcription factor Stat3 by IL-10 (7–11). The events downstream of Stat3 activation that mediate the anti-inflammatory functions of IL-10 remain an area of active research. It is becoming increasingly clear that multiple mechanisms mediate the IL-10 function. On the one hand, IL-10 inhibits transcription of a subset of pro-inflammatory genes (12, 13). In a mouse model lacking 3′UTR in the Tnf gene the transcriptional mechanism was found to play a major role in IL-10 responses (13). On the other hand, IL-10 was also reported to act posttranscriptionally by increasing the rate of mRNA decay of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, or by inhibiting translation (12, 14, 15). The posttranscriptional regulation depends on 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) containing AU-rich elements (AREs) (16). However, far less is known about the IL-10-regulated effector genes that control the anti-inflammatory response. Several candidates have been described, but so far none have been shown to account for the majority of the anti-inflammatory effects (17). IL-10 was also demonstrated to upregulate the dual-specificity phosphatase-1 (DUSP1) in LPS-stimulated macrophages causing a more rapid inactivation of p38MAPK (18). The reduction of p38MAPK activity may lead to a decreased stability of ARE-containing mRNAs and/or reduced transcription by transcription factors that depend on p38MAPK. Recently, the transcriptional repressor ETV3 and the corepressor SBNO2 were characterized as IL-10/Stat3-induced genes that may contribute to the anti-inflammatory IL-10 effects (19). An important aspect of the above mentioned studies that remains to be resolved is how IL-10 inhibits specifically only a subset of inflammatory genes. These studies indicate that yet unknown IL-10/Stat3 target genes need to be discovered to complement the current knowledge about the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10.

Here we demonstrate that IL-10-mediated reduction of TNFα and IL-1α production by LPS-treated mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) is less efficient in cells lacking the RNA-destabilizing factor tristetraprolin (TTP). TTP is known to bind and destabilize mRNAs of several pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNFα) containing class II AREs in their 3′UTRs (20). TTP facilitates degradation of the bound mRNA by initiating the assembly of RNA decay machinery (21, 22). The RNA degradation activity of TTP is negatively regulated by p38MAPK-dependent signalling (23–25). Mice lacking TTP (encoded by the Zfp36 gene) develop multiple chronic inflammatory syndromes ranging from arthritis, to cachexia to dermatitis that can all be relieved by reduction of TNFα levels (26). By comparing LPS-treated wild-type and TTP-deficient BMDMs we show that IL-10 accelerates, in a TTP-dependent way, the decay of TNFα mRNA resulting in a reduction of secreted TNFα. Furthermore, IL-10 increases TTP expression in LPS-treated WT but not Stat3-deficient BMDMs. However, we show that the increased TTP levels are not sufficient to mediate the IL-10 effects. Instead, the IL-10 mediated reduction of p38MAPK activity in LPS treated BMDMs, that is known to be caused by upregulation of the p38MAPK phosphatase DUSP1 (18) is required to act in concert with TTP to reduce mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1α. We propose that the sustained activation of Stat3 by IL-10 causes both an increased TTP expression and a reduction in p38MAPK activity. The combination of these effects results in a reduction of mRNA stability and attenuation of cytokine production.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Stat3, p38MAPK and DUSP1 (sc-1102) antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) antibody was from BD Transduction Laboratories (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium), phosphotyrosine-Stat3 antibody (pY-Stat3) was from Cell Signaling (NEB, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). Rabbit antibody to TTP was obtained by immunizing rabbits with 44 C-terminal amino acids of TTP fused to GST. IL-10 and IL-6 (Sigma, Austria) were used at a concentration of 10 ng/ml, LPS from Salmonella minnesota (Alexis, Switzerland) was used at a concentration of 5–10 ng/ml, anisomycin and actinomycin D (both Sigma) were used at a concentration of 100 ng/ml and 5 µg/ml, respectively. SB203580 (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO and used at final concentration 4µM. ATP (Sigma) (1µM) was added 1 h prior to collecting the samples.

Cell culture

Primary macrophages were grown in L cell-derived CSF-1 as described (27). Zfp36−/− and Dusp1−/− mice (26) were on C57Bl/6 background. The Zfp36 gene encodes TTP which is the better known name and therefore is used throughout. For experiments with cells derived from TTP−/− and TTP+/+ mice littermates originating from TTP+/− colony were used. The LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl mice were obtained by crossing Stat3fl/fl mice (28) with LysMcre, strain B6.129P2-Lyzstml(cre)Ifo (Jackson Laboratories Bar Harbor, Maine, USA), all on C57Bl/6 background. Mice, 8 to 12 weeks old at the time of bone marrow collection, were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mouse experiments were carried out in compliance with national laws. Mouse macrophage line RAW 264.7 was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

Inducible expression of TTP

The open reading frame of the mouse TTP was PCR-amplified from cDNA. The PCR was used to add Flag tag DYKDDDDK at the C-terminus. The TTP-flag fragment was cloned into the pGL2-basic (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) containing a tetracycline-responsive element (TRE) in the promoter. The resulting plasmid pTRE-TTPfl was transfected into HeLa-Tet-off cells (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) using nucleofection (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany). After transfection the cells were incubated overnight in medium with (no TTP expression) or without (TTP expression) tetracycline (1 µg/ml).

ELISA

For ELISA, BMDMs were seeded the day before use at 2 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well plate. Supernatants were diluted 1:8 in DMEM (for TNFα) or 1:2 (for IL-1α), and cytokines were assayed using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to manufacturer′s instructions.

Quantitative Western blot

After treatment, whole cell extracts were prepared and assayed by Western blotting as described (29). Detection and quantitation of signals was performed using the infrared imaging system Odyssey (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Quantitation of gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol-Reagent (Invitrogen, Austria). Reverse transcription was performed with Mu-MLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). Following primers were used: for HPRT, the housekeeping gene used for normalisation, HPRT-fwd 5’-GGATTTGAATCACGTTTGTGTCAT-3’, and HPRT-rev 5’-ACACCTGCTAATTTTACTGGCAA-3’; for TTP, TTP-fwd 5’- CTCTGCCATCTACGAGAGCC-3’ and TTP-rev 5’- GATGGAGTCCGAGTTTATGTTCC-3’; for TNFα, TNFα-fwd 5′- CAAAATTCGAGTGACAAGCCTG-3′ and TNFα-rev 5′-GAGATCCATGCCGTTGGC- 3′; for SOCS3, SOCS3-fwd 5′-GCTCCAAAAGCGAGTACCAGC-3′ and SOCS3-rev 5′-AGTAGAATCCGCTCTCCTGCAG-3′; for TTP primary transcript, TTPpt-fwd For determination of mRNA decay by qRT-PCR the primers TNFα-fwd 5′- TTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGGGGTGATCGGTCC-3′ and TNFα-rev 5′- GTATGAGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGTGTGGG-3′; for IL-1α the primer set QT00113505 from Qiagen (Duesseldorf, DE) was used. Amplification of DNA was monitored by SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) (30).

RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay (RNA-EMSA)

To prepare extracts cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM NaPPi, 50 mM NaF, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 15.000 rpm. 12 µl cell extract (30 µg protein) from Raw 264.7 cells or 5 µl cell extract (15 µg protein) from pTRE-TTPfl transfected HeLa-Tet-off cells were incubated with 0.5 µl Poly-U RNA (100ng/µl), 0.5 µl Cy5.5-labeled TNFα-ARE (1pmol/µl), 1 µL RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (Fermentas) and 2.5 µL 5x Gelshift buffer (200 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 100 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.9, Glycerin 50% (v/v)) for 20 min at room temperature. For supershift assays, 0.5 µl TTP antiserum was added. Samples were then separated on a 6 % polyacrylamide gel. The Cy5.5 signal was detected and quantified using the infrared imaging system Odyssey (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Poly-U RNA and Cy5.5’-labeled TNFα ARE RNA were purchased from Microsynth AG (Switzerland). The sequence for Cy5 5’-labeled TNFα ARE was as follows: 5’-AUUAUUUAUUAUUUAUUUAUUAUUUA-3’.

Statistical analysis

Data from independent experiments were analyzed using univariate linear regression models and the SPSS program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). For qRT-PCR normalized copy numbers and for ELISA pg/ml were log-transformed. Residuals were plotted, visually inspected, and tested for normality. Design matrices were specified such that the coefficients for the relevant comparisons could be calculated, e.g., between the baseline and induced states and between genotypes. Only the significance levels are reported.

Results

IL-10 increases TTP expression in LPS-treated macrophages in a Stat3-dependent manner

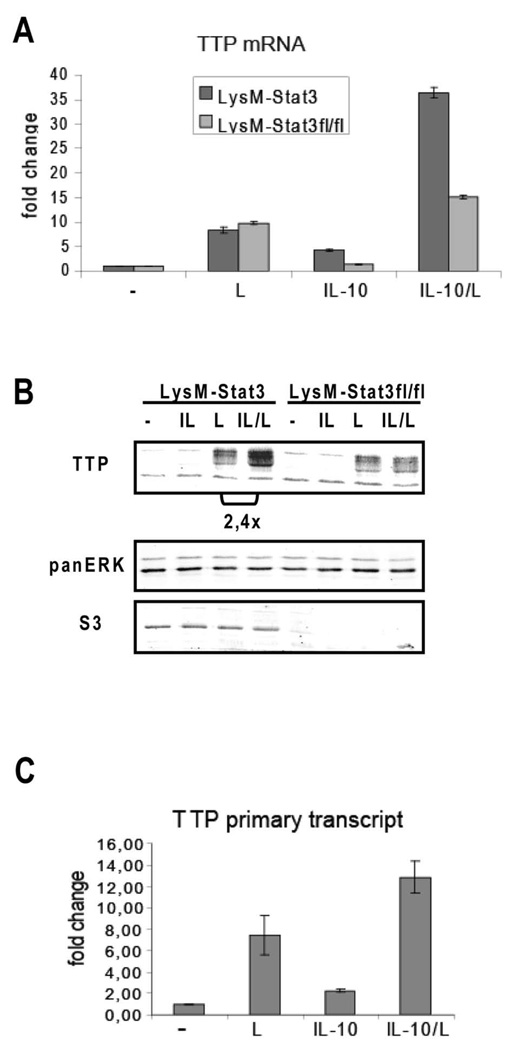

TTP expression has been reported to be controlled by the transcription factors Stat1 (in response to interferons) and Stat6 (in response to IL-4) (31). Affymetrix analysis revealed that LPS-induced TTP expression is further enhanced by IL-10 (data not shown) at 30 minutes post-treatment of Il10−/− BMDMs with IL-10 and LPS suggesting that TTP may represent a Stat3 target gene involved in the anti-inflammatory responses to IL-10. To examine the effect of IL-10 on TTP expression in more detail we investigated TTP gene expression in BMDMs conditionally deleted for Stat3 (LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl) and control LysMcre-Stat3 cells. LysMcre is known to delete loxP-flanked alleles in macrophage and neutrophil lineages with more than 90% efficiency (7). Treatment of BMDMs with IL-10 and LPS caused 2–3-fold increase in TTP mRNA (Fig. 1A) and protein levels (Fig. 1B) compared to LPS treatment alone. The IL-10-mediated increase in TTP expression required Stat3 since in LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl cells the TTP levels remained unchanged upon IL-10 treatment. The expression of Stat3 was reduced by more than 90% in LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl cells (Fig. 1B), thereby confirming the deletion efficiency by LysMcre. Analysis of TTP primary transcripts by PCR (Fig. 1C) and nuclear run-on assays (data not shown) revealed that the IL-10-mediated induction of TTP was caused by increased transcription.

Figure 1.

IL-10-mediated increase of TTP expression in LPS-treated macrophages depends on Stat3. A, BMDMs from LysMcre-Stat3 (LysM-Stat3) and LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl (LysM-Stat3fl/fl) mice were treated for 1 hour with LPS (L), IL-10 or both (IL-10/L). Induction of TTP mRNA was quantified using qRT-PCR. Bars indicate SDs, n=3. B, BMDMs from LysMcre-Stat3 (LysM-Stat3) and LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl (LysM-Stat3fl/fl) animals were left untreated or treated with IL-10 (IL), LPS (L) or both (IL/L) for 3 h. TTP protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting of cell extracts using TTP antibody. TTP appears in multiple bands representing phosphorylated forms. Blot was reprobed with Stat3 antibody to control for Stat3 deletion in LysMcre-Stat3fl/fl cells, and panERK antibody for loading control. Differences in TTP levels (normalized to panERK and quantitated using infrared imaging system Odyssey) in cells treated with IL-10/LPS compared to LPS alone are indicated. C, BMDM (wild type) were stimulated for 30 min with LPS (L), IL-10, or both (IL-10/L), total RNA was isolated, DNase-treated, and the amount of primary transcript was determined by qRT-PCR. Bars indicate SDs, n=3.

These findings document that IL-10-activated Stat3 increases expression of TTP in LPS-stimulated macrophages. IL-10 alone only weakly increased TTP transcription, and this induction was not sufficient to generate detectable levels of TTP protein. This way of regulation resembles that of interferon-induced TTP expression which was shown to be activated by interferons and the interferon-activated Stat1 only if p38MAPK signaling (by e.g. LPS) is stimulated in parallel (27). p38MAPK is known to increase by yet unclear mechanisms the transcriptional activity of several Stat members (32–34).

TTP is required for full inhibitory effect of IL-10 on TNFα and IL-1α production

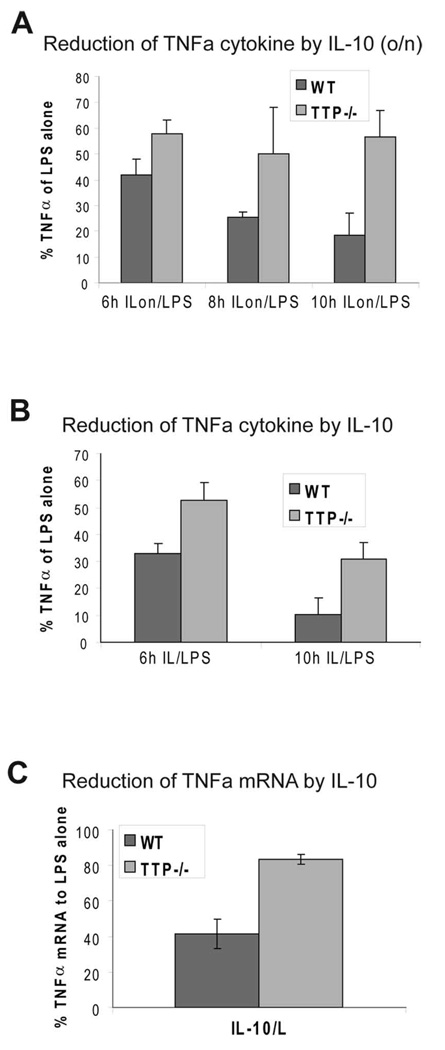

To test if TTP was an effector of the IL-10 anti-inflammatory responses we measured the amount of secreted TNFα by ELISA in BMDMs from TTP−/− and control wild-type littermates that were treated with LPS with or without pretreatment with IL-10. We measured TNFα production at 6, 8 and 10 h after LPS stimulation. After 10 h, TNFα was diminished by IL-10 to approximately 20% in control cells whereas in TTP−/− cells only a reduction to 60% was achieved (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained if cells were treated simultaneously with LPS and IL-10 (Fig. 2B) although the contribution of TTP to the IL-10 response was higher in the pretreatment protocol (Fig. 2A). These data show that TTP contributes to IL-10-mediated inhibition of TNFα cytokine production.

Figure 2.

TTP is required for full IL-10-mediated inhibition of TNFα production. A, Reduction of LPS-induced TNFα cytokine production in cells pretreated with IL-10. BMDMs from WT and TTP−/− mice were treated with LPS, or pretreated overnight with IL-10 followed by stimulation with LPS (ILon/LPS) for indicated time points, or left untreated (w/o). Supernatants were collected and analyzed for TNFα cytokine levels by ELISA. Reduction of TNFα cytokine levels by IL-10 pretreatment (IL-10 o/n) relative (in %) to LPS-alone treatment (100%) is depicted. SDs (n=4) are indicated. B, Effect of simultaneous treatment with IL-10 and LPS on TNFα cytokine production performed as described in A. Relative amounts of TNFα cytokine secreted by LPS-treated WT and TTP−/− BMDMs compared to cells simultaneously treated with IL-10/LPS are shown. SDs (n=3) are indicated. C, Reduction of LPS-induced TNFα mRNA in cells pretreated with IL-10. WT-BMDMs and TTP-deficient BMDMs (TTP−/−) were treated 2 hours with LPS or pretreated overnight with IL-10 followed by LPS addition (IL-10/L) and analyzed for expression of TNFα by qRT-PCR, normalized to HPRT mRNA. Shown is reduction of TNFα mRNA levels after IL-10/LPS treatment in relation to the sample treated with LPS alone. SDs (n=3) are indicated.

To investigate whether the incomplete IL-10-mediated inhibition of TNFα production in TTP−/− BMDMs resulted from differences in mRNA amounts or in mRNA decay we analyzed the amounts of TNFα mRNA in LPS-stimulated TTP−/− and control BMDMs with or without pretreatment with IL-10. In WT cells IL-10 caused a reduction of TNFα mRNA to 40% of the amount present in cells treated with LPS alone whereas in TTP−/− cells IL-10 caused a reduction to only 80% of the level in cells treated with LPS alone (Fig. 2C). In these experiments, TNFα mRNA was measured after 2 h of LPS treatment since the amount of TNFα mRNA peaks at this time point ((13) and data not shown). To further illustrate the role of TTP in IL-10-mediated decrease of TNFα mRNA we analyzed the rate of TNFα mRNA decay in LPS-stimulated TTP−/− and WT BMDMs with or without IL-10 pretreatment. Transcription was stopped after 3 h of LPS stimulation by addition of actinomycin D, and the degradation of TNFα mRNA was followed in 15 min intervals for a total of 45 min after imposing the transcriptional stop (Fig. 3A). In LPS-treated control BMDMs the decay rate of TNFα mRNA was increased 2,5-fold by IL-10 treatment (half life t1/2 without IL-10 = 32 min; t1/2 with IL-10 = 13 min). In LPS-treated TTP−/− BMDMs the residual TNFα mRNA decayed with a 2,5-fold longer half life (t1/2 = 82 min) compared to WT. This difference is similar to the one reported previously (35). Importantly, IL-10 treatment of LPS-stimulated TTP−/− cells did not increase the decay rate and the remnant mRNA levels were comparable to those in cells treated with LPS alone. LPS-stimulated macrophages produced endogenous IL-10 that is known to mask to some extent the effect of added IL-10 (e.g. (18)). Since TTP was recently shown to target IL-10 mRNA for degradation (36) we asked whether TTP−/− BMDMs produce more IL-10 after stimulation with LPS. Cytokine measurement revealed that TTP-deficient cells secrete 2–3-fold more IL-10 than the WT cells (supplemental Fig. S1). To assess the contribution of endogenous IL-10 to the IL-10-mediated TNFα mRNA decay we compared the TNFα mRNA levels and decay rates in IL-10−/− and WT cells. IL-10−/− BMDMs expressed 2-fold more TNFα than WT cells (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the reduction of TNFα mRNA by exogenous IL-10 was more pronounced in IL-10−/− cells compared to WT cells. The decay rate of TNFα mRNA was not affected by IL-10 treatment of WT cells stimulated for 1 or 2 h with LPS (Fig. 3C). However, IL-10 accelerated the decay rate in IL-10−/− cells treated for 2 h with LPS, but not for 1 h (Fig. 3D). Therefore, endogenous IL-10 can mask to a certain extent the effect of exogenous IL-10 on the mRNA decay. In addition, the IL-10-mediated increase in mRNA decay rate becomes more apparent at later time points of LPS treatment, consistent with the need for new protein synthesis (of e.g. TTP). Note that the duration of LPS treatment in Fig. 3A was 3 h and that the differences in IL-10-imposed inhibition of TNFα production in TTP−/− versus WT cells increased with time of LPS treatment (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 3.

TTP is required for IL-10-mediated acceleration of TNFα mRNA decay and for full IL-10-dependent reduction of IL-1α. A, IL-10-induced changes in decay of TNFα mRNA. WT-BMDMs and TTP-deficient BMDMs (TTP−/−) were pretreated with IL-10 overnight and stimulated for 3 hours with LPS followed by addition of actinomycin D (act D) (5 µg/ml) to stop transcription. After indicated time points TNFα mRNA was quantified using qRT-PCR. Values were normalized against the housekeeping gene HPRT. Remnant TNFα mRNA in % of the amount at the time point 0 of actinomycin D treatment is depicted. SDs (n=3) are indicated. B, Effects of endogenous IL-10 on TNFα mRNA induction in LPS- or LPS/IL-10-treated BMDMs. BMDMs derived from WT or IL-10−/− animals were treated for 1 or 2 h with LPS in the presence or absence of IL-10. The amount of TNFα mRNA in these cells was determined by qRT-PCR. C and D, TNFα mRNA decay in WT (C) and IL-10−/− (D) BMDMs. BMDMs were treated for 1 or 2 h with LPS in the presence or absence of IL-10. Thereafter, the transcription was stopped by actinomycin D and the remaining TNFα mRNA was determined at the indicated times by qRT-PCR. Remnant TNFα mRNA in % of the amount at the time point 0 of actinomycin D treatment is depicted. E, Reduction of IL-1α cytokine by IL-10. BMDMs from WT and TTP−/− mice were treated with LPS for 10 h in the presence or absence of IL-10. ATP was added 1 h prior to the collection of supernatants. Supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-1α cytokine levels by ELISA. Reduction of IL-1α cytokine levels by IL-10 pretreatment relative (in %) to LPS alone treatment (100%) is depicted. SDs are indicated, n=3. F, Reduction of IL-1α mRNA by IL-10. BMDMs from WT and TTP−/− mice were treated with LPS for 2 h in the presence or absence of IL-10. IL-1α expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Reduction of IL-1α mRNA by IL-10 treatment relative (in %) to LPS alone treatment (100%) is depicted.

To further substantiate the role of TTP in the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10, we measured the IL-10-mediated reduction of IL-1α protein and mRNA in TTP−/− and WT cells (Fig. 3E, F). Efficient LPS-stimulated production of IL-1α, a known IL-10 target (13), depends on a second stimulus, such as ATP, that activates the IL-1 processing function of the inflammasome (37). Although IL-1α is not a direct substrate of caspase-1, production of mature IL-1α has been shown to be inflammasome/caspase-1-dependent (37). BMDMs from WT and TTP−/− animals were stimulated with LPS (10 h) and ATP (1 h prior to the collection of supernatants) in the presence or absence of IL-10. IL-10 caused a decrease of IL-1α protein to 20% of LPS+ATP-treated WT cells, whereas in TTP−/− cells the IL-1α production was reduced only to 60% of the LPS+ATP-treated samples (Fig. 3E). Similar differences between WT and TTP−/− cells were determined also for IL-10-mediated decrease in IL-1α mRNA (Fig. 3F).

To rule out that the absence of TTP affected activation of Stat3 by IL-10, that might result in reduced IL-10 responsiveness of TTP−/− cells the IL-10-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat3 was determined in LPS-stimulated TTP−/− and WT BMDMs in the presence or absence of IL-10. The level of tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat3 was under all conditions comparable in both genotypes (supplemental Fig. S2A). In addition, the stimulatory effect of LPS was similar in TTP−/− and WT cells as judged by the activation of p38MAPK (supplemental Fig. S2B). Thus, a different activation of the critical pro-inflammatory (p38MAPK) and anti-inflammatory (Stat3) components in the WT and TTP−/− cells could be excluded as a reason for the observed differences in IL-10 responses.

These data establish that TTP plays an important role in IL-10-mediated downregulation of two critical inflammatory cytokines (TNFα and IL-1α).

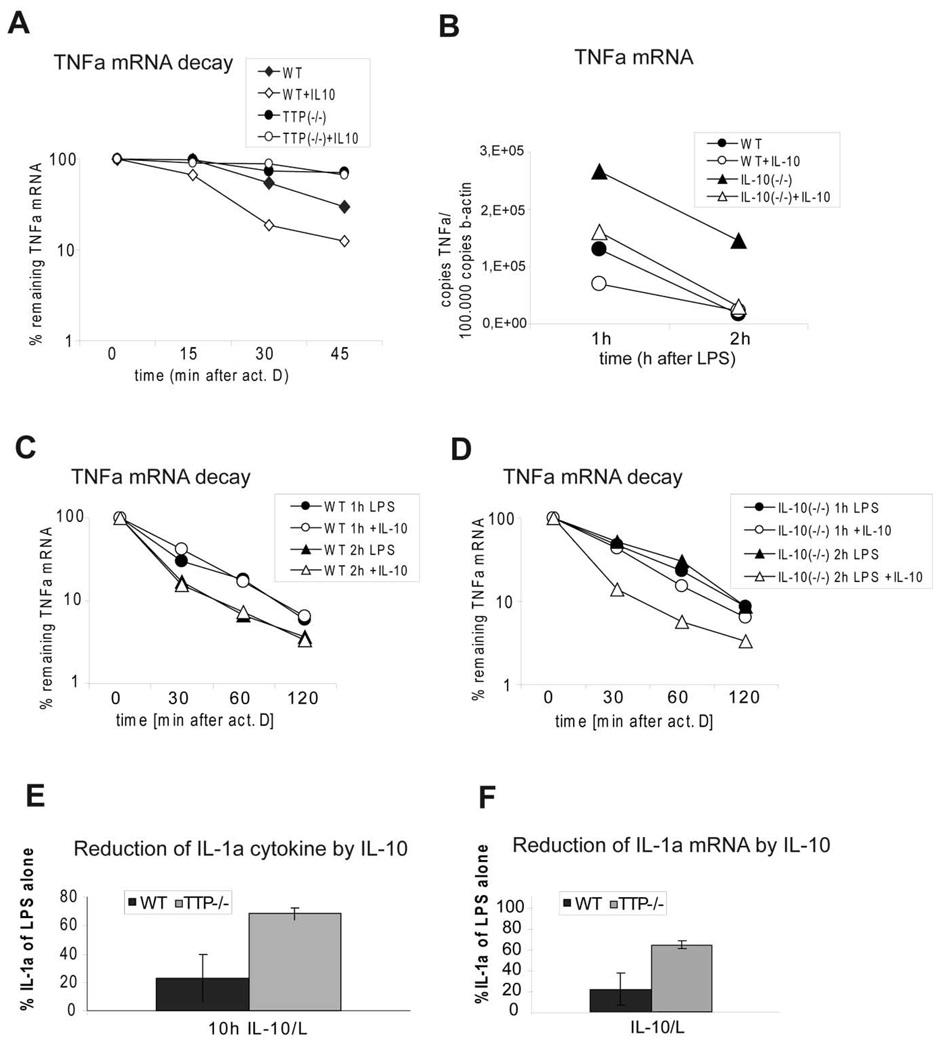

TTP function in IL-10 responses depends on IL-10-mediated reduction of p38MAPK activity at later phase of inflammation

IL-10 and IL-6 are both known to activate Stat3 yet only IL-10 exhibits anti-inflammatory properties (38–40). To examine whether and to what extent IL-6 was able to stimulate TTP expression, BMDMs were treated with LPS with or without IL-6. Interestingly, IL-6 was able to increase TTP expression in LPS-treated macrophages almost to the same extent as IL-10 (Fig. 4A). Yet, consistent with the known properties of IL-6, IL-6 was not able to inhibit TNFα (Fig. 4B) and IL-1α (Fig. 4C) in either WT or TTP−/− BMDMs. These data also implicate that the upregulation of TTP expression by IL-10 cannot solely explain the role of TTP in the anti-inflammatory effects of this cytokine. We speculated that the role of TTP in IL-10 responses might be explained by IL-10-dependent increase in TTP activity. TTP function is known to be negatively regulated by p38MAPK and its downstream kinase MK2 (41). IL-10 has been reported to modestly inhibit p38MAPK in the later phases of LPS treatment (18). The reduction of p38MAPK activity is caused by the IL-10-mediated upregulation of the dual specificity phosphatase DUSP1 ((18) and Fig. 4F). We reasoned that such a reduction in p38MAPK could relieve the p38MAPK-dependent inhibition of TTP thereby increasing the ability of TTP to downregulate its target mRNAs. To investigate whether IL-6 was also able to reduce p38MAPK activity, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS alone or together with either IL-10 or IL-6, and p38MAPK activity was monitored after 2, 4, and 6 h. Treatment of LPS-stimulated cells with IL-10 caused a modest (3-fold) but consistent inhibition of p38MAPK at 2, 4 and 6 h compared to the samples treated with LPS alone (Fig. 4D). To better document the IL-10 effect on p38MAPK phosphorylation the complete time course of IL-6- and IL-10-treated samples was run on a single gel (supplemental Fig. S3A). The LPS-induced activation of p38MAPK at an early time point (30 min) was not affected by IL-10 co-treatment (Fig 4E). Importantly, p38MAPK activity was not reduced by treatment with IL-6 at any time point examined (Fig. 4D, E and supplemental Fig. S3A). These findings are in agreement with the induction of mRNA for the MAPK phosphatase DUSP1 by IL-10 but not IL-6 in LPS-treated macrophages (18). To further support the role of DUSP1 in the IL-10-mediated effect on p38MAPK activity we examined p38MAPK phosphorylation in DUSP1−/− BMDMs treated with LPS alone or together with either IL-10 or IL-6 for 4 h. In DUSP1−/− cells IL-10 was no longer able to reduce p38MAPK phosphorylation after treatment (Fig. 4F). Consistent with the IL-10-mediated decrease in p38MAPK phosphorylation, at the 4 h time point the induction of DUSP1 by IL-10+LPS compared to LPS alone was more apparent than after a shorter treatment (1 h, supplemental Fig. S3B). The different effect of IL-10 and IL-6 on p38MAPK is in agreement with the anti-inflammatory properties that are exhibited by IL-10 but not IL-6. The difference between IL-10 and IL-6 with regard to their anti-inflammatory properties has been attributed to SOCS3 that, as part of the negative feedback loop, binds to the GP130 subunit of the IL-6 receptor but not to the IL-10 receptor (38–40). Thus, SOCS3, a Stat3 target gene, is able to inhibit signaling elicited by IL-6 but not by IL-10. Consequently, IL-10 induces a prolonged STAT3 activation whereas IL-6-mediated Stat3 activation is rapidly shut down. Consistently, in LPS-treated BMDMs IL-10 and IL-6 caused a comparable Stat3 activation after 30 min of cytokine treatment whereas after 2 h Stat3 remained active only in cells stimulated with IL-10 but not IL-6 (supplemental Fig. 3C). These data suggest that a sustained Stat3 activation is needed for inhibition of p38MAPK.

Figure 4.

Effects of IL-6 on TTP expression, TNFα and IL-1α production, and p38MAPK activation in LPS-treated BMDMs. A, IL-6 and IL-10 increase TTP expression to similar levels in LPS-treated BMDMs. BMDMs were stimulated for 2 h with LPS alone or together with IL-10 or IL-6, and whole cell extracts were prepared. Expression of TTP was analyzed by Western blotting. panERK antibody was used for loading control. B and C, IL-6 does not reduce TNFα production (B) or IL-1α (C) production in LPS-treated TTP−/− and control WT BMDMs. WT and TTP−/− BMDMs were stimulated for 10 h with LPS with or without co-treatment with IL-6. Amounts of TNFα and IL-1α in supernatants were determined by ELISA. SDs of three representative experiments (n=3) are indicated. D, IL-10 but not IL-6 decreases p38MAPK activity in LPS-treated BMDMs. Whole cell extracts of BMDMs treated for 2, 4 and 6 h with LPS alone or co-treated with IL-10 or IL-6 were analyzed for activation of p38MAPK by Western blotting using antibody to activated p38MAPK (pp38). Antibody to total p38MAPK (p38) was used for loading control. E, p38MAPK is not inhibited by IL-10 or IL-6 after 30 min of treatment. BMDMs were treated for 30 min with LPS with or without co-treatment with IL-10 or IL-6. p38MAPK activation was determined as in D. F, IL-10 no longer reduces p38MAPK phosphorylation in DUSP1−/− BMDMs. DUSP1−/− BMDMs were treated for 4 h with LPS alone, LPS+IL-10 or LPS+IL-6, and the activation of p38MAPK was examined as in D. Figures are representative of at least 3 experiments.

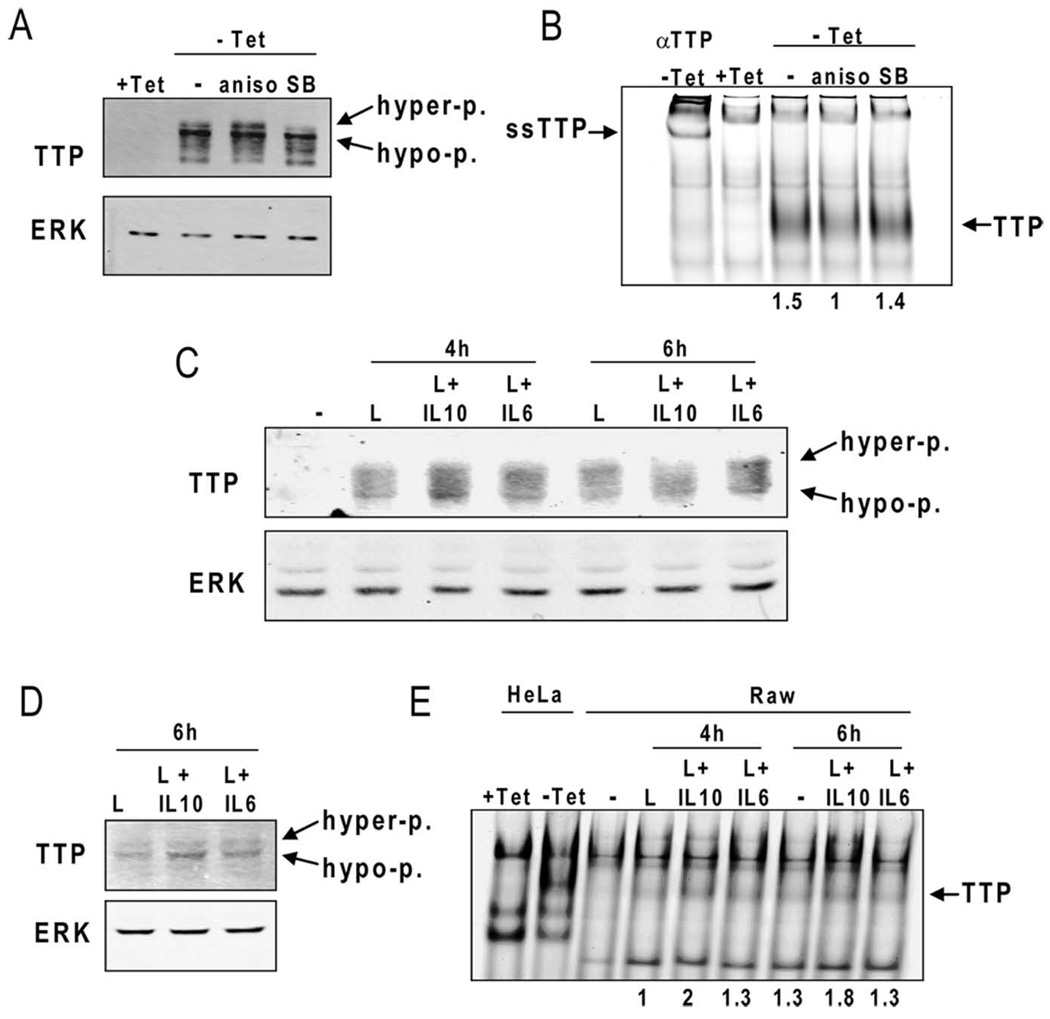

Although p38MAPK is needed for TTP expression and protein stability (24, 25, 42), the kinase negatively regulates TTP activity at least at two levels. First, phosphorylation of TTP at Ser52 and Ser178 by MAPKAP kinase 2 (MK2), a kinase downstream of p38MAPK, provides binding sites for 14–3–3 proteins that reduce the destabilizing activity of TTP (23, 43). Second, phosphorylation of TTP by MK2 was reported to negatively regulate its binding to AREs (25). To show that the IL-10-mediated decrease in p38MAPK activity was able to change TTP properties in terms of its phosphorylation and binding to AREs we analyzed the mobility of TTP in SDS-PAGE and binding of TTP to AREs in EMSA experiments. TTP appears in SDS-PAGE in form of multiple bands that reflect various degree of predominantly p38MAPK-dependent phosphorylation (24). To demonstrate p38MAPK effects on TTP phosphorylation and binding to AREs we first used an inducible expression of TTP in HeLa-Tet-off cells. This system allows manipulation of p38MAPK activity without affecting the transcription of the TTP gene that is known to require p38MAPK activity (27, 42). Stimulation of HeLa-Tet-off cells expressing TTP (i.e. without tetracycline) with anisomycin (a p38MAPK agonist (44)) resulted in a more pronounced appearance of a slower migrating hyper-phosphorylated TTP band whereas the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 reduced the amount of the hyper-phosphorylated TTP and also the total TTP level due to TTP protein destabilization (Fig. 5A). The analysis of the same extracts in an RNA-EMSA experiment revealed that anisomycin reduced binding of TTP to the TNFα ARE by 50% (Fig. 5B) whereas inhibition of p38MAPK resulted in a similar amount of ARE-bound TTP as in untreated cells (Fig. 5B) despite a reduced TTP protein level present in that sample (compare SB-labeled lanes in Fig. 5A and 5B). Consistent with the IL-10-mediated p38MAPK inhibition, the treatment of BMDMs with LPS+IL-10 resulted in a shift to less phosphorylated TTP bands in SDS-PAGE if compared to cells treated with LPS alone or with LPS+IL-6 (Fig. 5C). This shift to faster migrating TTP bands was more pronounced after 6 h of treatment. To address the IL-10 effect on TTP binding to AREs we employed the murine macrophage cell line Raw 264.7 since we were not able to detect TTP-ARE complexes in RNA-EMSA experiments if BMDM were used. LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 cells express at least 3–5-fold more TTP than BMDMs (data not shown). Similar to BMDMs, LPS+IL-10 treatment resulted in a more pronounced appearance of the hypo-phosphorylated TTP if compared to treatment with LPS alone or LPS+IL-6 (Fig. 5D). Consistently, LPS+IL-10 treatment caused an approximately 50–80% increase in the formation of TTP-ARE complexes in RNA-EMSA experiments compared to LPS alone or LPS+IL-6 treatments (Fig. 5E). These data show that IL-10 decreases the phosphorylation of TTP and enhances the in vitro binding of TTP to TNFα ARE in a manner similar to the pharmacological inhibition of p38MAPK. These findings are in agreement with an increased TTP activity under conditions of reduced p38MAPK activation as is the case in IL-10-treated cells. Interestingly, despite the reduced p38MAPK activity, and hence increased proteasome-mediated TTP degradation in IL-10-treated cells, the TTP protein levels were not diminished compared to LPS+IL-6-treated cells (Fig. 5C, D). We explain this observation by the sustained STAT3 activation and, hence, a strong STAT3-driven transcription of the TTP gene in IL-10-treated cells (supplemental Fig. 3C).

Figure 5.

IL-10 reduces TTP phosphorylation and increases in vitro binding of TTP to ARE. A and B, HeLa-Tet-off cells were transiently transfected with pTRE-TTPfl and equally split into four 6cm dishes. In three dishes, the expression of TTP was allowed overnight in medium without tetracycline (−Tet), whereas in one dish the TTP expression was blocked by tetracycline (+Tet). The (−Tet) cells were treated for 60 min with anisomycin (aniso) or SB203580 (SB). Whole cell extracts were prepared and split into one part for Western blot analysis (A), and a second part for RNA-EMSA (B). The position of hyper-phosphorylated (hyper-p.) and hypo-phosphorylated (hypo-p.) TTP is marked in A. In B, the TTP-ARE complexes (TTP) were identified by a supershift (ssTTP) using a TTP antibody (αTTP). The relative intensity of the TTP-ARE complexes (as indicated be the numbers 1.5, 1, and 1.4) was quantitated using the LI-COR Odyssey software (supplementary Fig. 4A). C, Whole cell extracts of BMDMs treated for 4 and 6 h with LPS alone or co-treated with IL-10 or IL-6 were analyzed for TTP expression and SDS-PAGE mobility by Western blotting using antibody to TTP. Equal protein loading was controlled by reprobing with an anti ERK antibody. The position of hyper-phosphorylated (hyper-p.) and hypo-phosphorylated (hypo-p.) TTP is marked. D, Whole cell extracts of Raw 264.7 treated for 6 h with LPS alone or co-treated with IL-10 or IL-6 were analyzed as in C. E, Whole cell extracts of Raw 264.7 cells treated for 4 or 6 h with LPS alone or co-treated with IL-10 or IL-6 were assayed for in vitro binding of TTP to TNFα ARE using RNA-EMSA. The relative intensity of the TTP-ARE complexes (as indicated by the numbers 1, 2, 1.3, 1.3, 1.8, 1.3) was quantitated using the LI-COR Odyssey software (supplementary Fig. 4B). To control the position of the TTP-ARE complexes extracts from HeLa-Tet-off cells expressing TTP (−Tet) or without TTP expression (+Tet) were used. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

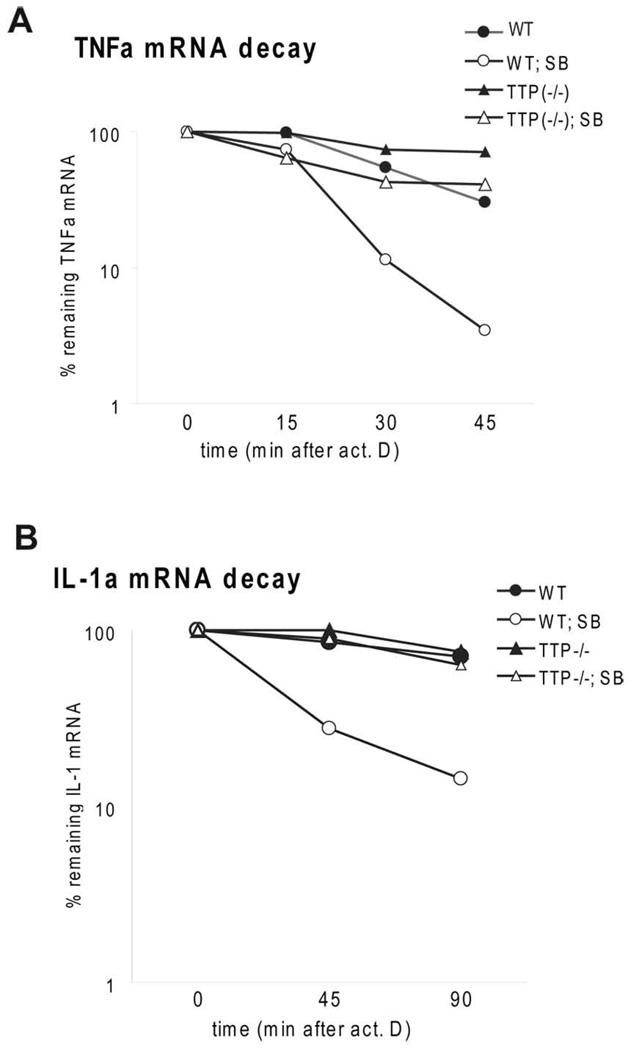

To test if p38MAPK activity protects mRNA from TTP-mediated decay we examined the stability of TNFα and IL-1α mRNAs in the presence of the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 in TTP−/− and control WT BMDMs. 2 h after LPS stimulation SB203580 was added together with actinomycin D. p38MAPK inhibition caused a 4-fold decrease of mRNA stability of TNFα (TNFα without SB: t1/2 = 31 min; TNFα with SB: t1/2 = 8 min) and an about 8–10-fold decrease in IL-1α mRNA stability (IL-1α without SB: t1/2 > 2 h; IL-1α with SB: t1/2 = 14 min) (Fig. 5). In TTP−/− cells the inhibition of p38MAPK caused only a modest (2-fold) decrease in mRNA stability of TNFα mRNA (TNFα without SB: t1/2 = 80 min; TNFα with SB: t1/2 = 37 min with SB) and no detectable decrease of IL-1α mRNA stability (IL-1α without SB: t1/2 > 2 h; IL-1α with SB: t1/2 > 2 h). These data indicate that the augmentation of mRNA decay by inhibition of p38MAPK is to a large part TTP-dependent. The contribution of TTP to the effects of p38MAPK inhibition depends on the nature of the target mRNA. We conclude that the IL-10-mediated reduction of p38MAPK activity increases TTP-dependent mRNA decay. The combined effect of IL-10 on p38MAPK activity and TTP expression contributes to the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-10.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that the mRNA destabilizing factor TTP plays an important role in anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10. BMDMs deficient in TTP show a strongly reduced anti-inflammatory response to IL-10. Two cytokines, TNFα and IL-1α, were here demonstrated to be inhibited by IL-10 in a TTP-dependent manner. IL-10 appears to regulate TTP function in two ways. First, IL-10 increases TTP expression in LPS-treated BMDMs. This augmented expression depends on Stat3, the key immediate effector of IL-10 effects. Second, IL-10 reduces at later time points the activity of p38MAPK in LPS-treated BMDMs hereby releasing TTP from the p38MAPK-mediated inhibition. Since the increased expression of TTP is not sufficient to initiate an anti-inflammatory response (as demonstrated by IL-6-mediated upregulation of TTP) we conclude that the TTP-dependent IL-10 effects can be best explained by the combination of higher TTP expression and reduction of p38MAPK activity.

TTP is known for its mRNA destabilizing activity most notably, but not exclusively, towards TNFα mRNA via AREs in 3′UTR. Thus, the IL-10-mediated rise in TNFα decay rate is consistent with the elevated TTP levels and activity. In addition to TNFα, our data suggest that IL-1α is also a TTP target. The 3′UTR of the murine IL-1α (Genbank accession number NM_010554; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/) contains three elements (UAUUUAUA, AUAUUUAU and UAUUAUUUAU) with similar sequences as the nonameric canonical sequence (UUAUUUAUU) recognized by TTP (45, 46). IL-1α has so far not been described as TTP target despite of several recently published global screens for novel TTP targets (36, 47). However, these searches revealed that in such global screens important targets might be missed (e.g. TNFα in the study of Stoecklin and colleagues (36)). In addition, the finding that TTP regulates also mRNAs with no obvious AREs in 3′UTR adds another degree of complexity to searches for TTP targets (47). The role of TTP in IL-10 responses is also in agreement with a study reporting IL-10-mediated ARE-dependent destabilization of CXCL1 mRNA (16). Importantly, in that study the IL-10-induced mRNA decay was not detectable before 2 h of LPS/IL-10 treatment. This time point correlates well with the appearance of TTP expression (42) and with our data showing that IL-10-mediated decay of TNFα mRNA is not apparent before 2 h of LPS treatment.

TTP-deficient cells are known to produce 2–3-fold more TNFα (both mRNA and cytokine) than WT cells (26, 48). At the same time, IL-10 mRNA was shown to be targeted by TTP for degradation (36) and we found that the TTP-deficient BMDMs produce more IL-10 cytokine (supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, TTP cells produce more of both the proinflammatory TNFα and the anti-inflammatory IL-10. Yet, the TTP cells still respond to IL-10 treatment (by e.g. Stat3 activation) and LPS treatment (by e.g. p38MAPK activation) similarly as the WT cells (Fig. 4). We conclude that despite of the 2–3-fold higher production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines the TTP-deficient cells display comparable immediate-early response to pro- (LPS) or anti-inflammatory (IL-10) stimuli as WT cells.

We were not able to detect any differences in the TTP expression or p38MAPK activity, the two key factors influencing the TTP function, when we compared the two protocols for IL-10 treatment. Thus, the higher absolute contribution of TTP to IL-10 responses in the pretreatment protocol suggests that IL-10 induces a cofactor of TTP during the pretreatment period. TTP serves as an adaptor protein linking mRNA to the mRNA processing and degradation machinery located in stress granules (SGs) and processing bodies (PBs) (21), (22). Some of the components of these complexes may be up-regulated by IL-10 during the pretreatment phase to enhance TTP function. Alternatively, IL-10-activated Stat3 may increase transcription of micro RNAs (miRNAs) such as miR16 that was shown to assist TTP in degradation of ARE-containing mRNAs (49). The influence of the experimental protocol on the IL-10 effects may also partially explain the discrepancy between our study and the study of Kontoyiannis and colleagues who found no evidence for a role of TTP in IL-10 responses in the simultaneous treatment protocol (14). Instead, they proposed a rapid (within 15 min of IL-10 treatment) inhibition of p38MAPK as the main mechanism of IL-10 action. We did not detect any inhibition of p38MAPK activity by IL-10 at early time points regardless of applied protocol for IL-10 treatment (supplemental Fig. S2A, B). These data are in agreement with several other studies showing no effect of IL-10 on p38MAPK activity at early time points (2, 12, 50, 51). In a kinetics analysis of p38MAPK activity IL-10 was found to exhibit a modest inhibitory effect on p38MAPK activity at later time points (after 3 h of LPS+IL-10 treatment) (18). The IL-10-mediated inhibition of p38MAPK correlated with the induction of the dual specificity phosphatase DUSP1, a MAPK phosphatase (18). We observed a similar reduction in p38MAPK phosphorylation in terms of both, the magnitude and kinetics, and found that DUSP1 was required for this effect. The inhibition of p38MAPK was caused specifically by IL-10 but not by IL-6, and correlated with the ability of IL-10 (but not IL-6) to induce sustained Stat3 activation. Consistently, IL-10 but not IL-6 was reported to increase expression of DUSP1 in LPS-treated macrophages (18). DUSP1 function as a critical p38MAPK-inactivating enzyme provides the most likely explanation for the susceptibility of DUSP1−/− mice to LPS-mediated toxic shock (52, 53). We speculate that the inhibition of the pro-inflammatory p38MAPK by IL-10 at the later stages of macrophage stimulation is a key factor in immune homeostasis since p38MAPK influences inflammation-related transcription, RNA stability, translation as well as secretion. To mimic the inhibition of p38MAPK by IL-10 at the late phase of stimulation we used the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580, and examined the effect of p38MAPK on TTP-dependent decrease of target mRNA molecules. Interestingly, whereas in case of TNFα a different decay rate (i.e. different decay rate in TTP+/+ and TTP−/− cells) was observed also without p38MAPK inhibition, for IL-1α mRNA the TTP-dependent decay was detectable only if p38MAPK was inhibited (Fig. 5). A similar requirement for p38MAPK inhibition has been recently described also for the TTP target CXCL1 (KC) mRNA (54). These findings indicate the p38MAPK-mediated control of TTP activity has differential impact on target mRNAs. While the TTP-dependent decay of some mRNAs (e.g. TNFα) proceeds in the presence of p38MAPK activity, the degradation of other mRNAs (e.g. IL-1α and CXCL1) is strongly dependent on the kinase inhibition. This mechanism may play an important role in the specificity of TTP-mediated RNA decay: depending on the activation status of p38MAPK or other kinases implicated in regulation of TTP activity (e.g. ERK of MK2), TTP would discriminate between various targets. The critical role that p38MAPK plays in TTP-mediated RNA decay also suggests that the tito determine RNA stability has a decisive effect on the outcome of the assay. The activation/inactivation profile of p38MAPK is likely to vary between different experimental settings (e.g. amount and quality of LPS, the use of primary or immortalized cells, the origin of primary cells such as bone marrow or peritoneum) so that this aspect may also contribute to the variability of published data. E.g., we did not observe an IL-10-mediated increase in TNFα mRNA decay in peritoneal-derived macrophages.

Suppression of inflammatory responses by IL-10 is one of the key features in immune homeostasis. Despite of many years of research the question of how a single cytokine can specifically inhibit various inflammatory reactions with such a high efficiency remains unresolved. Recent studies suggest that known as well as yet unknown IL-10 effectors interfere on different levels and by different mechanisms with the intracellular inflammatory networks. This multitasking system employed by IL-10 is likely to be essential for the efficiency and specificity of the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-10. E.g., the efficient and dominant inhibition of Tnf gene transcription by IL-10 still requires the remaining TNFα mRNA to be removed from the system, i.e. by TTP. While the primary IL-10-elicited signaling events, that involve the IL-10 receptor, Jak1 and Tyk2 kinases as well as the transcription factor Stat3, are to a large part common to all cell types, the more complex effects downstream of Stat3 may be cell type-dependent. Thus, the function and activity of the Stat3-induced IL-10 effectors may be regulated by the environment within the particular cell type, hereby helping to explain the still incoherent and sometimes contradictory studies of the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6.

Effects of p38MAPK inhibition on TTP-dependent reduction of mRNA for TNFα and IL-1α. A and B, WT and TTP−/− BMDMs were treated with LPS for 2 h, followed by treatment with SB203580 (SB) or solvent control. Actinomycin D was added simultaneously with SB203580. The decay rates of TNFα (A) and IL-1α (B) were monitored by qRT-PCR for times indicated. Remnant TNFα or IL-1α mRNA in % of the amount at the time point 0 of actinomycin D treatment is depicted.

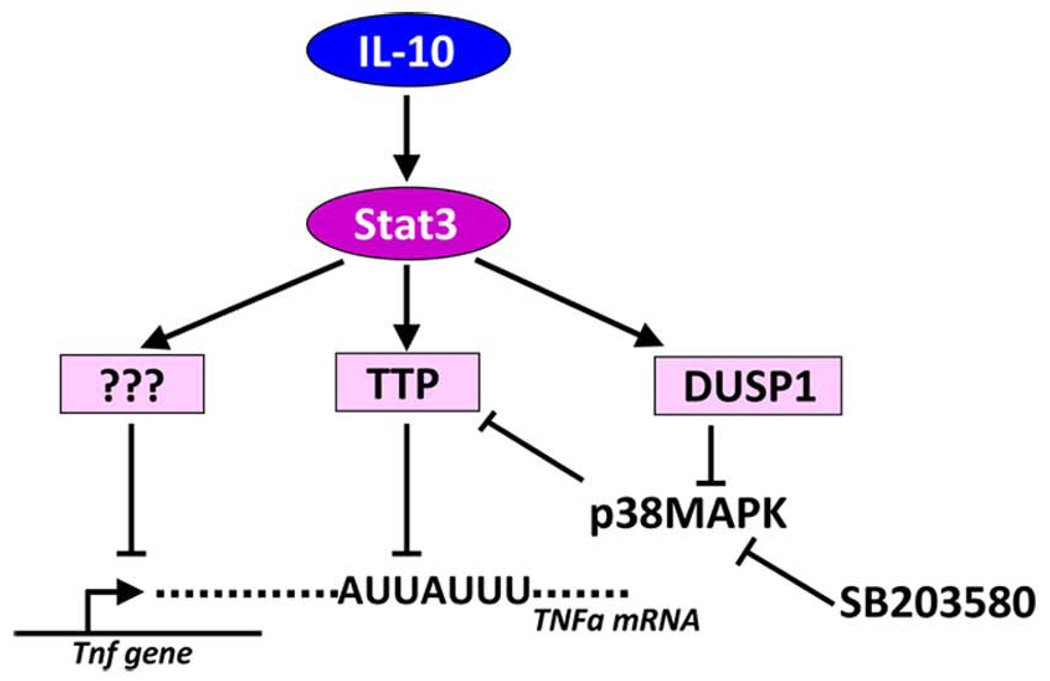

Figure 7.

Model of IL-10-mediated anti-inflammatory effects. IL-10 activates the transcription factor Stat3 that drives the expression of at least three effector genes. The still unidentified repressors of transcription are depicted by question marks. The other effector is TTP that requires the activity of a third effector, the DUSP1 phosphatase, that reduces the activity of p38MAPK thereby increasing the TTP destabilizing activity towards specific ARE-containing mRNAs. The activity of DUSP1 can be mimicked by e.g. the p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank S. Badelt for excellent technical help. The authors thank Bristol Myers Squibb for the permission to use Dusp1−/− mice.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grants SFB F28 and P16726-B14, and the European Science Foundation (ESF) grant I27-B03 to PK, by the Austrian Science Fund FWF SFB F28 and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research (BMWF GZ200.112/1-VI/1/2004) to MM, by the NIH grant AI062921 to PJM, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants SFB 576/TP-A11 and LA1262/4-1 to RL.

References

- 1.Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams LM, Ricchetti G, Sarma U, Smallie T, Foxwell BM. Interleukin-10 suppression of myeloid cell activation--a continuing puzzle. Immunology. 2004;113:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg DJ, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W, Menon S, Davidson N, Grunig G, Rennick D. Interleukin-10 is a central regulator of the response to LPS in murine models of endotoxic shock and the Shwartzman reaction but not endotoxin tolerance. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2339–2347. doi: 10.1172/JCI118290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roers A, Siewe L, Strittmatter E, Deckert M, Schluter D, Stenzel W, Gruber AD, Krieg T, Rajewsky K, Muller W. T cell-specific inactivation of the interleukin 10 gene in mice results in enhanced T cell responses but normal innate responses to lipopolysaccharide or skin irritation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1289–1297. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siewe M, Bollati-Fogolin L, Wickenhauser C, Krieg T, Muller W, Roers A. Interleukin-10 derived from macrophages and/or neutrophils regulates the inflammatory response to LPS but not the response to CpG DNA. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:3248–3255. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Forster I, Akira S. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams L, Bradley L, Smith A, Foxwell B. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is the dominant mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;172:567–576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maritano D, Sugrue ML, Tininini S, Dewilde S, Strobl B, Fu X, Murray-Tait V, Chiarle R, Poli V. The STAT3 isoforms alpha and beta have unique and specific functions. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:401–409. doi: 10.1038/ni1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams LM, Sarma U, Willets K, Smallie T, Brennan F, Foxwell BM. Expression of constitutively active STAT3 can replicate the cytokine-suppressive activity of interleukin-10 in human primary macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6965–6975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denys A, Udalova IA, Smith C, Williams LM, Ciesielski CJ, Campbell J, Andrews C, Kwaitkowski D, Foxwell BM. Evidence for a dual mechanism for IL-10 suppression of TNF-alpha production that does not involve inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase or NF-kappa B in primary human macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;168:4837–4845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray PJ. The primary mechanism of the IL-10-regulated antiinflammatory response is to selectively inhibit transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8686–8691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500419102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontoyiannis D, Kotlyarov A, Carballo E, Alexopoulou L, Blackshear PJ, Gaestel M, Davis R, Flavell R, Kollias G. Interleukin-10 targets p38 MAPK to modulate ARE-dependent TNF mRNA translation and limit intestinal pathology. Embo J. 2001;20:3760–3770. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajasingh J, Bord E, Luedemann C, Asai J, Hamada H, Thorne T, Qin G, Goukassian D, Zhu Y, Losordo DW, Kishore R. IL-10-induced TNF-alpha mRNA destabilization is mediated via IL-10 suppression of p38 MAP kinase activation and inhibition of HuR expression. Faseb J. 2006;20:2112–2114. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6084fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas R, Datta S, Gupta JD, Novotny M, Tebo J, Hamilton TA. Regulation of chemokine mRNA stability by lipopolysaccharide and IL-10. J Immunol. 2003;170:6202–6208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuwata H, Watanabe Y, Miyoshi H, Yamamoto M, Kaisho T, Takeda K, Akira S. IL-10-inducible Bcl-3 negatively regulates LPS-induced TNF-alpha production in macrophages. Blood. 2003;102:4123–4129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer M, Mages J, Dietrich H, Schmitz F, Striebel F, Murray PJ, Wagner H, Lang R. Control of dual-specificity phosphatase-1 expression in activated macrophages by IL-10. European journal of immunology. 2005;35:2991–3001. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Kasmi KC, Smith AM, Williams L, Neale G, Panopolous A, Watowich SS, Hacker H, Foxwell BM, Murray PJ. Cutting Edge: A Transcriptional Repressor and Corepressor Induced by the STAT3-Regulated Anti-Inflammatory Signaling Pathway. J Immunol. 2007;179:7215–7219. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrick DM, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. The tandem CCCH zinc finger protein tristetraprolin and its relevance to cytokine mRNA turnover and arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:248–264. doi: 10.1186/ar1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kedersha N, Stoecklin G, Ayodele M, Yacono P, Lykke-Andersen J, Fritzler MJ, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Golan DE, Anderson P. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;169:871–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franks TM, Lykke-Andersen J. TTP and BRF proteins nucleate processing body formation to silence mRNAs with AU-rich elements. Genes Dev. 2007;21:719–735. doi: 10.1101/gad.1494707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoecklin G, Stubbs T, Kedersha N, Wax S, Rigby WF, Blackwell TK, Anderson P. MK2-induced tristetraprolin:14-3-3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. Embo J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brook MC, Tchen R, Santalucia T, McIlrath J, Arthur JS, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Posttranslational Regulation of Tristetraprolin Subcellular Localization and Protein Stability by p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2408–2418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2408-2418.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hitti T, Iakovleva E, Brook M, Deppenmeier S, Gruber AD, Radzioch D, Clark AR, Blackshear PJ, Kotlyarov A, Gaestel M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 regulates tumor necrosis factor mRNA stability and translation mainly by altering tristetraprolin expression, stability, and binding to adenine/uridine-rich element. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2399–2407. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2399-2407.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor GA, Carballo E, Lee DM, Lai WS, Thompson MJ, Patel DD, Schenkman DI, Gilkeson GS, Broxmeyer HE, Haynes BF, Blackshear PJ. A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency. Immunity. 1996;4:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer I, Schaljo B, Vogl C, Gattermeier I, Kolbe T, Muller M, Blackshear PJ, Kovarik P. Interferons limit inflammatory responses by induction of tristetraprolin. Blood. 2006;107:4790–4797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonzi T, Maritano D, Gorgoni B, Rizzuto G, Libert C, Poli V. Essential role of STAT3 in the control of the acute-phase response as revealed by inducible gene activation in the liver. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1621–1632. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1621-1632.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovarik P, Stoiber D, Novy M, Decker T. Stat1 combines signals derived from IFN-gamma and LPS receptors during macrophage activation [published erratum appears in EMBO J 1998 Jul 15;17(14):4210] Embo J. 1998;17:3660–3668. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison TB, Weis JJ, Wittwer CT. Quantification of low-copy transcripts by continuous SYBR Green I monitoring during amplification. Biotechniques. 1998;24:954–958. 960, 962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Ikeda K, Maezawa Y, Suto A, Takatori H, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. IL-4-Stat6 signaling induces tristetraprolin expression and inhibits TNF-alpha production in mast cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1717–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsauer K, Sadzak I, Porras A, Pilz A, Nebreda AR, Decker T, Kovarik P. p38 MAPK enhances STAT1-dependent transcription independently of Ser-727 phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12859–12864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192264999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pesu M, Aittomaki S, Takaluoma K, Lagerstedt A, Silvennoinen O. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates interleukin-4-induced gene expression by stimulating STAT6-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38254–38261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Sassano A, Majchrzak B, Deb DK, Levy DE, Gaestel M, Nebreda AR, Fish EN, Platanias LC. Role of p38alpha Map kinase in Type I interferon signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:970–979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoecklin G, Tenenbaum SA, Mayo T, Chittur SV, George AD, Baroni TE, Blackshear PJ, Anderson P. Genome-wide analysis identifies interleukin-10 mRNA as target of tristetraprolin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11689–11699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Galan JE, Askenase PW, Flavell RA. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M, Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, Hirano T, Chien KR, Yoshimura A. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:551–556. doi: 10.1038/ni938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang R, Pauleau AL, Parganas E, Takahashi Y, Mages J, Ihle JN, Rutschman R, Murray PJ. SOCS3 regulates the plasticity of gp130 signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:546–550. doi: 10.1038/ni932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Forster I, Clausen BE, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Roberts AW, Alexander WS. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandler H, Stoecklin G. Control of mRNA decay by phosphorylation of tristetraprolin. Biochemical Society transactions. 2008;36:491–496. doi: 10.1042/BST0360491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahtani KR, Brook M, Dean JL, Sully G, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 controls the expression and posttranslational modification of tristetraprolin, a regulator of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6461–6469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.6461-6469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson BA, Stehn JR, Yaffe MB, Blackwell TK. Cytoplasmic localization of tristetraprolin involves 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18029–18036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukunaga R, Hunter T. MNK1, a new MAP kinase-activated protein kinase, isolated by a novel expression screening method for identifying protein kinase substrates. Embo J. 1997;16:1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Worthington MT, Pelo JW, Sachedina MA, Applegate JL, Arseneau KO, Pizarro TT. RNA binding properties of the AU-rich element-binding recombinant Nup475/TIS11/tristetraprolin protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48558–48564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blackshear PJ, Lai WS, Kennington EA, Brewer G, Wilson GM, Guan X, Zhou P. Characteristics of the interaction of a synthetic human tristetraprolin tandem zinc finger peptide with AU-rich element-containing RNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19947–19955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emmons J, Townley-Tilson WH, Deleault KM, Skinner SJ, Gross RH, Whitfield ML, Brooks SA. Identification of TTP mRNA targets in human dendritic cells reveals TTP as a critical regulator of dendritic cell maturation. RNA (New York, N.Y. 2008;14:888–902. doi: 10.1261/rna.748408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4311–4323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jing Q, Huang S, Guth S, Zarubin T, Motoyama A, Chen J, Di Padova F, Lin SC, Gram H, Han J. Involvement of microRNA in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA instability. Cell. 2005;120:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donnelly RP, Dickensheets H, Finbloom DS. The interleukin-10 signal transduction pathway and regulation of gene expression in mononuclear phagocytes. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:563–573. doi: 10.1089/107999099313695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray PJ. STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory signalling. Biochemical Society transactions. 2006;34:1028–1031. doi: 10.1042/BST0341028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abraham SM, Lawrence T, Kleiman A, Warden P, Medghalchi M, Tuckermann J, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1883–1889. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammer M, Mages J, Dietrich H, Servatius A, Howells N, Cato AC, Lang R. Dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) regulates a subset of LPS-induced genes and protects mice from lethal endotoxin shock. J Exp Med. 2006;203:15–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Datta S, Biswas R, Novotny M, Pavicic PG, Herjan T, Jr, Mandal P, Hamilton TA. Tristetraprolin regulates CXCL1 (KC) mRNA stability. J Immunol. 2008;180:2545–2552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.