Abstract

An efficient on-line digestion system that reduces the number of sample manipulation steps has been demonstrated for high throughput proteomics. By incorporating a pressurized sample loop into a liquid chromatography-based separation system, both sample and enzyme (e.g., trypsin) can be simultaneously introduced to produce a complete, yet rapid digestion. Both standard proteins and a complex Shewanella oneidensis global protein extract were digested and analyzed using the automated on-line pressurized digestion system coupled to an ion mobility time of flight mass spectrometer and/or an ion trap mass spectrometer. The system denatured, digested, and separated product peptides in a manner of minutes, making it amenable to high-throughput applications. In addition to simplifying and expediting sample processing, the system was easy to implement and no cross contamination was observed among samples. As a result, the on-line digestion system offers a powerful approach for high-throughput screening of proteins that could prove valuable in biochemical research; for example, quick screening of protein-based drugs.

Introduction

Within the last decade, the development and use of a multidimensional liquid chromatography (LC)- mass spectrometry (MS) based workflow for protein and peptide analysis has benefited biological research as well as, the pharmaceutical, food and biotech industries1,2. Sample preparation is typically one of the most time-consuming steps in the analysis workflow as it is typically carried out manually and carries an associated risk of artifacts that include sample contamination (e.g., keratins) and/or irreproducibility. Reducing these sources of error is particularly important for samples that are often only available in limited quantities and sizes, such as from clinical biopsies. Additional drawbacks to manual sample processing are the potential for larger sample/reagent consumption and increased costs due to the labor involved.

Classical proteomics approaches generally involve enzyme hydrolysis of a protein (either separated by polyacrylamide gels or in solution) followed by peptide identification using MS-based peptide mass fingerprinting or using LC-MS/(MS). Enzymatic digestions can take up to several hours to complete, although several methods based on high intensity focused ultrasound have been shown to accelerate the digestion process.3, 4 Ultrasound-enhanced digestions are usually performed off-line to ensure effective sonication, which makes the process difficult to automate. Another strategy that aims at on-line protein digestion uses immobilized enzymes;5,6 however, on-line digestions have rarely been used in an automated fashion due to issues associated with enzyme stability, clogging when using a solid trypsin bound matrix, and changing organic solvent concentrations necessary for on-line separations in addition to the reusability, longevity and durability of the immobilized enzyme7–9.

Herein we report the application of a fast on-line digestion system (FOLDS) that makes use of high pressure to accelerate enzyme digestion 10, 11 12,13 and reduces sample processing time to seconds rather than hours 14. The system consists of a flow injection LC system fitted with a pressurized loop to which sample and protease (e.g., trypsin) are simultaneously introduced. The protease effectively and rapidly digests the sample proteins and produces peptides for subsequent MS-based analysis. The reduced analysis time compared to classical methods makes it attractive for high-throughput proteomics. The performance of this system has been evaluated, and initially demonstrated with three different MS-based systems in our laboratory.

Experimental

Materials and Reagents

Sequencing grade trypsin was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Myoglobin, β-lactoglobulin, dithiothretiol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IAA), ammonium bicarbonate, formic acid and HPLC grade solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Apparatus

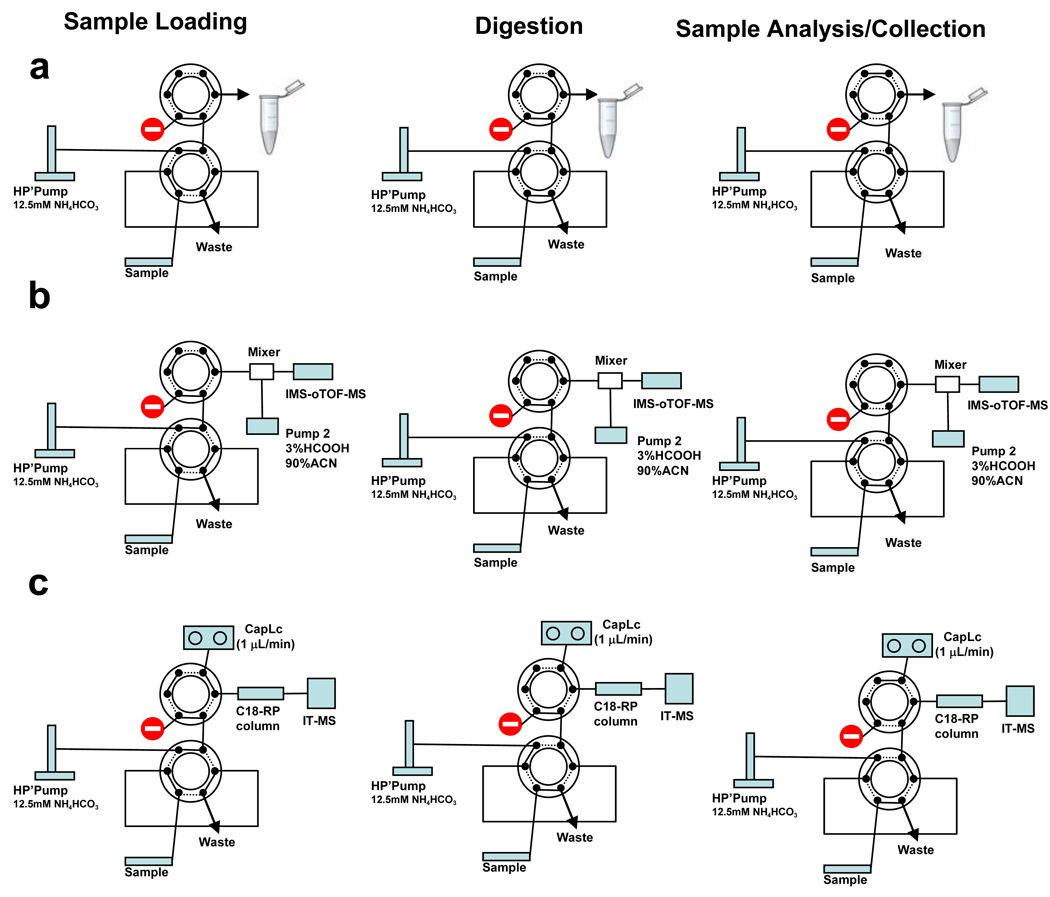

The fluidic components of the system consisted of a 6–port injection valve with a 5 µL sample loop and a 4–port valve (VICI Valco, Houston TX) rated to 15,000 psi. A 10,000 psi syringe pump (Teledyne ISCO, Lincoln, NE) supplied mobile phases to the system. The FOLDS was operated at pressures ranging from 0 up to 7000 psi and water was used as mobile phase. Details regarding valve, port, and sample loop placement are shown in Figure 1. Several modifications to the initial configuration (Figure la) were implemented to couple the system on-line to a mass spectrometer. For the system illustrated in Figure 1b, a second syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA) filled with 90% acetonitrile and 1 % formic acid was used to re-acidify the sample prior to ESI. In a third configuration (Figure 1c), the FOLDS was coupled to an Agilent LC 1100 equipped with a nano-flow pump (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Peptides were eluted using a gradient from 10 to 60% solvent B (Solvent A: 0.5% formic acid; Solvent B: 0.5% formic, 80% acetonitrile).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the fast on-line digestion system (FOLDS). The components include a syringe pump, and two six port injection valves. The valves are shown in the positions corresponding to the stage of experiment, a) Off-line set-up used with an FTICR MS. b) FOLDS coupled to a IMS-o-TOF MS instrument. A secondary syringe pump was needed to re-acidify sample prior to MS-analysis. c) FOLDS coupled to an LC-MS system. A RPLC separation column was coupled to the second six port valve and an ion trap was used for signal detection.

Digestion Procedures

Proteins were solubilized in a 12.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.2) and mixed with sequencing grade modified trypsin in a 1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio. Bovine serum albumin was first reduced with 10 mM DTT at 37 °C during 1 hour and alkylated with 50 mM IAA at room temperature for 45 min. The Shewanella oneidensis sample was prepared as described elsewhere 15 and used as a control. Otherwise, the soluble proteome was prepared in the same way as described above. The mixtures were loaded into the pressurized system for digestion, and digests were either collected for off-line experiments or analyzed directly using MS.

System Operation

The steps involved in operating the FOLDS are summarized in Table 1. System functionality is described according to three stages of sample processing: loading, digestion, and analysis or collection. During the sample loading stage, the loop is initially filled with 5 µl of sample and dissolved trypsin. To initiate protein digestion, the first valve is switched to the inject position to pressurize the system to 7,000 psi. The liquid flow to the rest of the system is blocked since the second valve is in the load position and the port is closed. In the digestion stage, the sample loop serves as a reaction chamber, and digestion is allowed to continue for 1 to 3 min. When the pressure-assisted digestion is finished, the second valve is switched to the inject position to initiate the sample analysis stage. The digested sample can be directly infused into a mass spectrometer, collected for off-line analysis, or directed to a reversed phase column for chromatographic separation.

Table 1.

Operating Sequence of the FOLDS Manifold

| System | Step | Injection value Position |

Selection value Position |

Pump P1 (flow rate) |

Pump P2 (flow rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Load | 1 | 0 µL/min | NA |

| 1 | 2 | Inject | 1 | 0 µL/min | NA |

| 1 | 3 | Inject | 2 | 50 µL/min | NA |

| 2 | 1 | Load | 1 | 0 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

| 2 | 2 | Inject | 1 | 0 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

| 2 | 3 | Inject | 2 | 50 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

| 3 | 1 | Load | 1 | 0 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

| 3 | 2 | Inject | 1 | 0 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

| 3 | 3 | Inject | 2 | 5 µL/min | 0 µL/min) |

| 3 | 4 | Load | 1 | 0 µL/min | 1 µL/min |

MS Analysis

Initially the FOLDS was employed in an off-line mode (Figure 1a) to characterize digestion efficiency. Samples were collected and dried down, and then resuspended in 10 µL of 40% MeOH:Water, 0.1 % formic acid buffer. Samples were electrosprayed using a TriVersa Nanomate (Advion Bioscienccs, Ithaca, NY) into a modified Bruker 12 Tesla APEX-Q FTICR mass spectrometer, as previously described 16. A mass spectrum was recorded every 2 s, and an average of three mass spectra was used for data analysis. For on-line applications, two different set ups were used. In the first set up, the FOLDS (Figure 1b) was coupled to a platform that incorporated a home-built IMS apparatus and Agilent 6210 oTOF mass spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The design of the IMS-oTOF analyzer has been described elsewhere 17,18. In another set of experiments, the FOLDS (Figure 1c) was coupled to capillary reversed phase LC-ion trap MS (LCQ or LTQ ion traps, Thermo-Fisher, San Jose, CA) and operated as previously described19.

Data Analysis

For high resolution MS-only analyses, proteins were identified using the MASCOT search engine,20 whereas the SEQUEST™21 database search engine was used for MS/MS analyses. A previously published method19 was used to calculate error rates associated with peptide identifications.

Results and Discussion

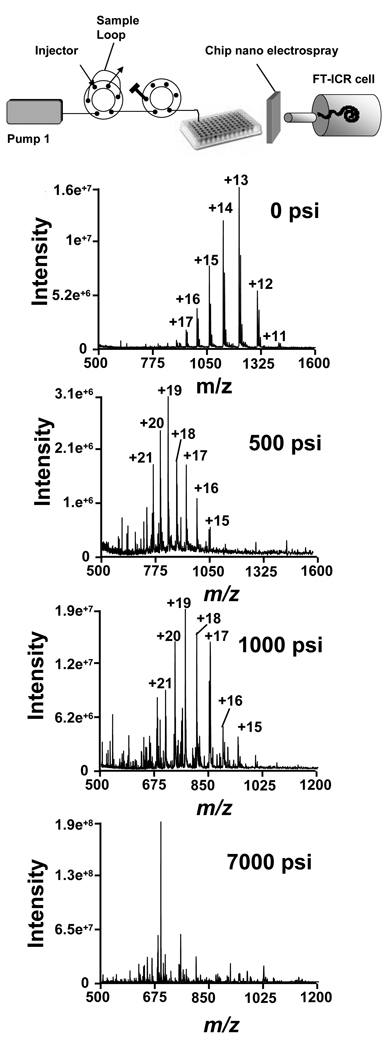

FOLDS, a fast on–line digestion system that takes advantage of high pressures to accelerate enzyme activity10,11,13,22 was evaluated in a series of experiments. In the first experiment, 1 pmol of myoglobin in 12 mM ammonium bicarbonate with trypsin was injected into the system (Figure 1a). The effect of pressure applied for a period of 1 min was evaluated for several pressures between 0 and 7000 psi. Samples were collected in reaction tubes and analyzed using ESI-chip-assisted direct infusion into a FTICR MS (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Upper panel shows the schematic workflow of the analysis. Sample loop was loaded with myoglobin and trypsin and pressurized during 1 min. The off-line samples were then analyzed using an T FTICR mass spectrometer. The lower panels show the corresponding spectra obtained when the sample was not pressurized (0 psi) or pressurized at 500 psi, 1000 psi or 7000 psi. Myoglobin charge states are indicated.

The use of FOLDS combined with ultra high resolution mass spectrometry allowed us to simultaneously detect any non-digested intact proteins along with dominant proteolytic peptides. When no pressure was applied, the eluted protein was detected with charge states that ranged from 11–15. When pressure was increased to 500 psi, the high protein charge states were still observed, but no peptide fragments. This finding is most likely due to a dramatic change in the protein tertiary structure that resulted in protonation of previously unexposed sites. In the third experiment, pressure was increased to 1000 psi. MS analysis revealed a mixture of both peptides and the intact protein, which indicates that both digestion and denaturation processes were occurring. At this pressure the peptides identified with less than three missed cleavages provided 100% protein coverage (see supplementary info). Since it has been previously demonstrated that complete digestion occurs in 1 min at 5000 psi 13, we increased the pressure in the FOLDS to 7000 psi. Although the maximum pressure of the pump is 10,000 psi, we chose the tower pressure of 7000 psi as a compromise between the tolerance of the system and the speed of digestion. Complete protein digestion was achieved in 1 min, where either no undigested protein or fragments with more than 3 missed cleavages were detected (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Identified Peptides after digestion at 7000 Psi during 1 min.

| Start— Enda | Mr (exp) | Δ Mass (ppm) | Number of missed cleavage sitesb |

Peptide Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 1814.892 | −1.71 | 0 | -.GLSDGEWQQVLNVWGK.V |

| 1 | 31 | 3402.732 | 0.03 | 1 | -.GLSDGEWQQVLNVWGKVEADIAGHGQEVLIR.L |

| 17 | 31 | 1605.845 | −1.43 | 0 | K.VEADIAGHGQEVLIR.L |

| 32 | 42 | 1270.655 | −0.55 | 0 | R.LFTGHPETLEK.F |

| 32 | 45 | 1660.845 | −0.84 | 1 | R.LFTGHPETLEKFDK.F |

| 32 | 47 | 1936.007 | −1.50 | 2 | R.LFTGHPETLEKFDKFK.H |

| 32 | 50 | 2314.247 | −0.22 | 3 | R.LFTGHPETLEKFDKFKHLK.T |

| 48 | 56 | 1085.55 | −4.05 | 1 | K.HLKTEAEMK.A |

| 48 | 63 | 1856.961 | −3.18 | 3 | K.HLKTEAEMKASEDLKK.H |

| 51 | 63 | 1478.728 | −0.54 | 2 | K.TEAEMKASEDLKK.H |

| 57 | 77 | 2149.248 | 0.23 | 2 | K.ASEDLKKHGTVVLTALGGILK.K |

| 57 | 78 | 2277.343 | 0.22 | 3 | K.ASEDLKKHGTVVLTALGGILKK.K |

| 64 | 77 | 1377.83 | −3.12 | 0 | K.HGTVVLTALGGILK.K |

| 64 | 78 | 1505.926 | −2.39 | 1 | K.HGTVVLTALGGILKK.K |

| 64 | 79 | 1634.024 | −0.18 | 2 | K.HGTVVLTALGGILKKK.G |

| 78 | 96 | 2109.142 | −0.90 | 2 | K.KKGHHEAELKPLAQSHATK.H |

| 79 | 96 | 1981.046 | −1.92 | 1 | K.KGHHEAELKPLAQSHATK.H |

| 80 | 96 | 1852.953 | −0.92 | 0 | K.GHHEAELKPLAQSHATK.H |

| 97 | 118 | 2600.487 | 0.92 | 2 | K.HKIPIKYLEFISDAIIHVLHSK.H |

| 97 | 133 | 4084.131 | −1.18 | 3 | K.HKIPIKYLEFISDAHHVLHSKHPGDFGADAQGAMTK.A |

| 99 | 118 | 2335.333 | 1.11 | 1 | K.IPIKYLEFISDAIIHVLHSK.H |

| 99 | 133 | 3818.984 | 0.55 | 2 | K.IPIKYLEFISDAIIHVLHSKHPGDFGADAQGAMTK.A |

| 103 | 118 | 1884.013 | −0.80 | 0 | K.YLEFISDAIIHVLHSK.H |

| 103 | 133 | 3367.667 | 0.18 | 1 | K.YLEFISDAIIHVLHSKHPGDFGADAQGAMTK.A |

| 119 | 133 | 1501.659 | −2.06 | 0 | K.HPGDFGADAQGAMTK.A |

| 134 | 145 | 1359.749 | −1.32 | 1 | K.ALELFRNDIAAK.Y |

| 134 | 153 | 2282.202 | −1.58 | 3 | K.ALELFRNDIAAKYKELGFQG.- |

| 140 | 153 | 1552.787 | −1.29 | 2 | R.NDIAAKYKELGFQG.- |

Position of the first and last residues of the peptide in the protein sequence.

Number of missed trypsin cleavage site among the peptide sequence.

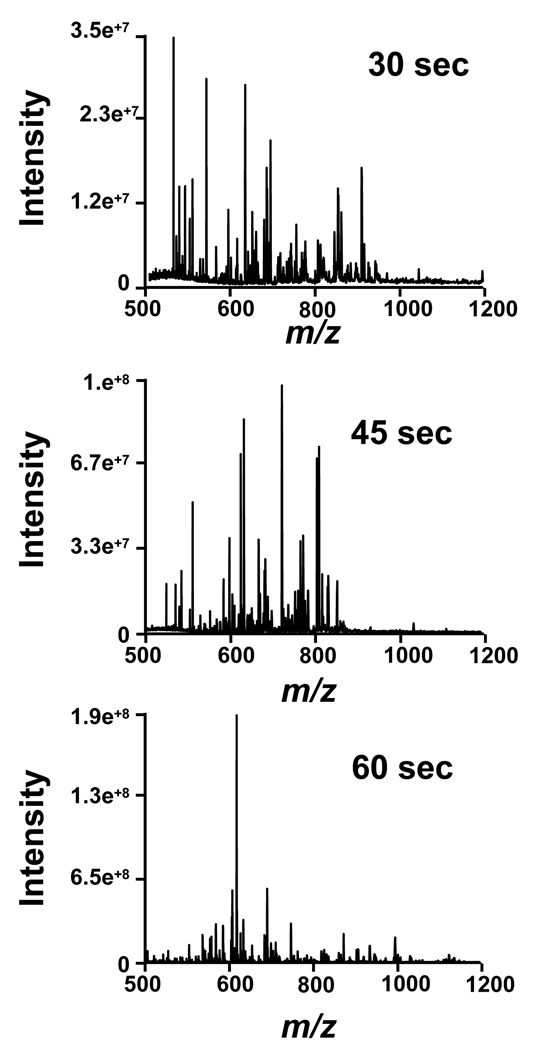

Since 7000 psi pressure facilitated complete and rapid digestion in 1 min, we further explored digestion kinetics at reaction times of 30 s and 45 s (Figure 3) at 7000 psi. Figure 3 shows that even at 30 s a satisfactory digestion was achieved, allowing protein identification through peptide mass fingerprinting yielding 100% protein coverage. However, a small portion of myoglobin remained intact. Consistent with the previous results, the intact protein was detected with charge states 21 and 23 respectively, indicating that the protein is effectively denaturated. For the 45 sec digestion, no remaining intact protein was detected and only one of the peptides detected had 4 missed cleavages, and five had 3 missed cleavages. This findings show that reasonably complete digestion can be achieved in only 45 sec. The results are summarized in Table 3 together with the MASCOT scores. The combination of high mass accuracy and the numerous peptides detected allowed unequivocal protein identification from data generated in less than 1 minute. A longer one minute digestion provided 100% coverage, as well as peptides with fewer missed cleavages.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the mass spectra obtained from FOLDS trypsin digestion of myoglobin as a function of the elapsed time at a pressure of 7000 psi.

Table 3.

Peptide mass fingerprinting results for time course digestion experiment performed at 7000 psi.

| Digestion Time (sec) |

Protein Identified |

Mascot Score |

Protein Coverage |

Average Mass Accuracy (ppm) |

Number of Peptide Peaks Matched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | MYG_EQUBU | 358 | 100% | −2.3 | 27 |

| 45 | MYG_EQUBU | 375 | 100% | 1.3 | 29 |

| 60 | MYG_EQUBU | 482 | 100% | −1.0 | 28 |

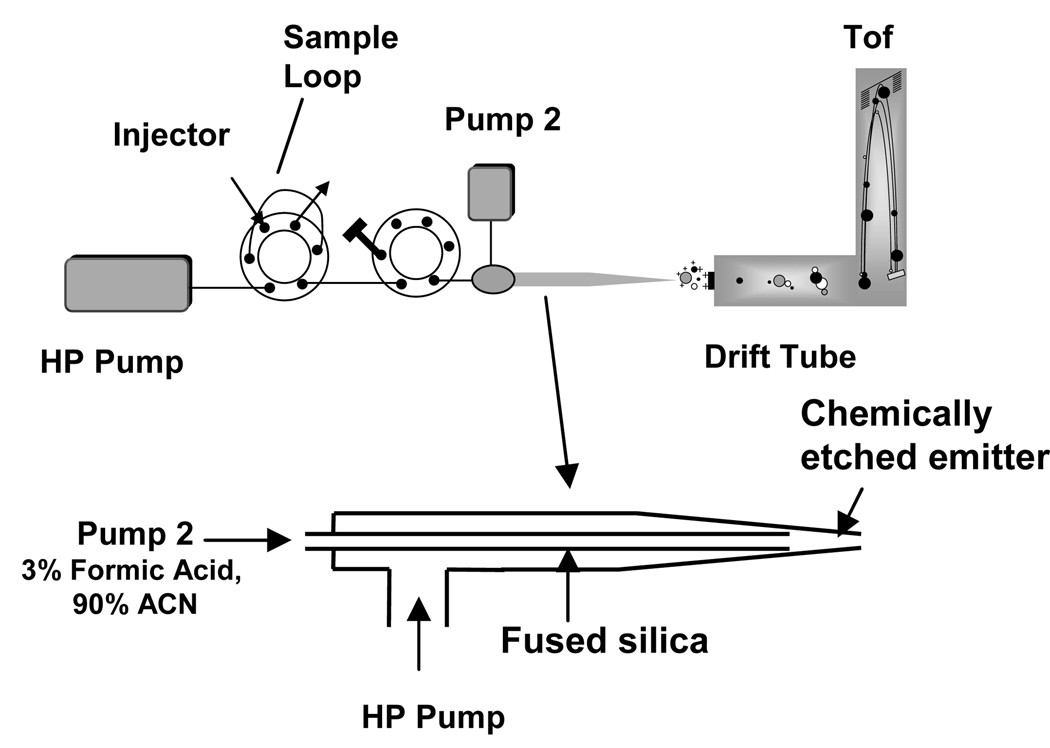

These initial experiments showed rapid and effective protein digestion could be achieved in a system amenable to fast and high-throughput applications; the next step was to examine direct coupling with a high-throughput proteomics platform. The FOLDS was coupled to IMS-TOF MS. The addition of an orthogonal separation such as ion mobility has some crucial advantages, such as the mobility separation is performed in ~100 milliseconds and time of flight mass spectra are generated in microseconds, allowing thousands of mass spectra per ion mobility separation. For applications to highly complex mixtures, this combination can provide improvements in the signal to noise ratio (e.g. due to separation of species different charge states), and detection of otherwise unresolved conformers. In initial experiments the FOLDS flow rate was relatively high (50 µL/min) and the sample loop only 10 µL, and we thus expected a loss of sensitivity due to high flow rates, possible sample dilution and the use of 100% aqueous mobile phase. To circumvent the last concern, an organic buffer (90% MeOH, 1% Formic acid) delivered by an independent syringe pump was mixed with the FOLDS eluent at the ESI emitter (Figure 4), to improve the ionization efficiency23. Back flow of the acidified solvent was prevented by the higher pressure afforded by the FOLDS pump.

Figure 4.

Upper panel: Experimental setup for on-line coupling of the FOLDS to a IMS-oTOF MS. Lower panel: Schematic diagram of the mixing of aqueous and organic buffer solutions at the ESI tip.

The FOLDS was investigated using myoglobin and 1 min pressure application (7000 psi) with and without trypsin. Figure 5 shows the results obtained for IMS-TOF-MS analysis of the digested myoglobin sample. Apparently, complete digestion was achieved, providing full protein coverage and unequivocal protein identification. The total analysis time from the start of injection to spectrum acquisition was < 90 sec. However, since the sample was pushed from the loop at such a high flow rates, the real acquisition time for the mass spectrometer was less than 10 sec. The key contributor to the speed of this analysis is the ability of the IMS-TOF MS to separate ions quickly in the gas phase, based mainly on their charge and gas-kinetic cross section. The IMS separation allowed differentiation between two peptides with close m/z (Figure 6a), and revealed the respective isotopic distributions (Figure 6b). We additionally evaluated this system in the analysis of an equimolar mixture of myoglobin and β-lactoglobulin (1 pmol each), as depicted in Figure 6c. Peptide mass fingerprinting identified both proteins with high MASCOT scores and yielded high protein coverage (Table 4).

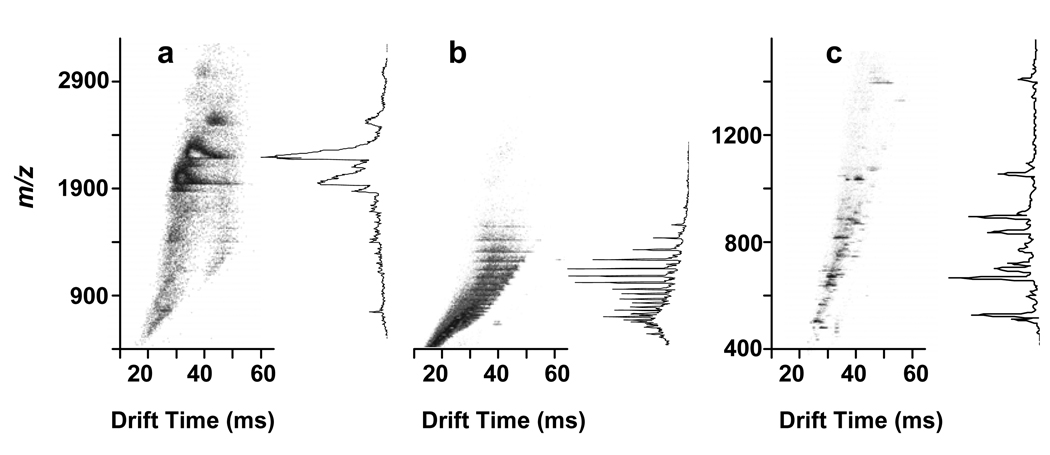

Figure 5.

Two dimensional map obtained in the course of IMS-TOF MS experiments with 1 pmol of myoglobin digested with the FOLDS. a) Myoglobin spectra obtained without pressurization of the reaction loop. b) Myoglobin spectra at pressure of 7000 psi for 1 min, no trypsin used. c) Myoglobin spectra at a pressure of 7000 psi for 1 min, sample mixed with trypsin in the reaction loop.

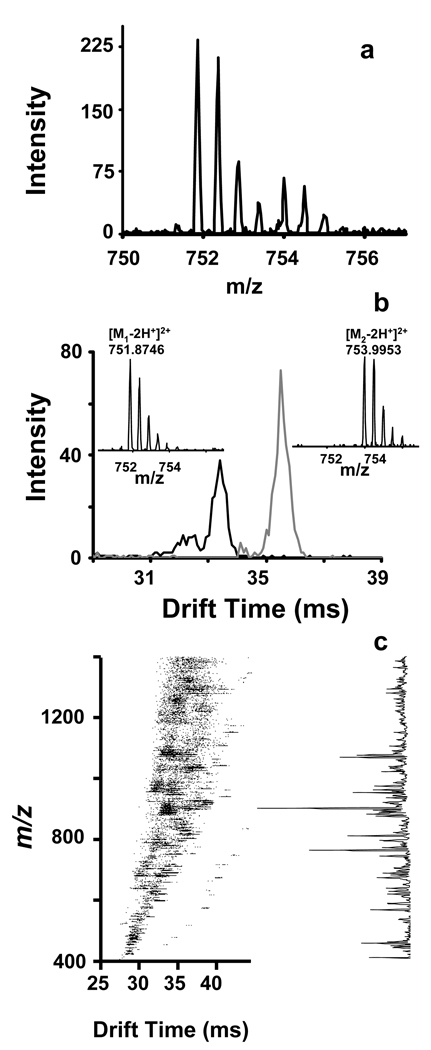

Figure 6.

a) Summed IMS-TOF MS spectra of the peptides shown in Figure 6b. The summed mass spectra demonstrate an overlap m/z domain. b) Reconstructed, multiplexed IMS-TOF MS spectra for peptides HPGDFGADAQGAMTK and KHGTVVLTALGGILK. Signal of each peptide was acquired in 200 IMS-TOF MS averages. c) Two dimensional IMS-TOF MS map and the summed mass spectrum obtained with an equimolar mixture of β-lactoglobulin and myoglobin.

Table 4.

Peptide mass fingerprinting results for a mixture of myoglobin and β-lactoglobulin digested using FOLDS (1 min at 7000 psi) and subsequently analyzed using IMS-oTOF-MS obtained using MASCOT search engine.

| Protein | Total Score | Expectation Value |

Number of Peaks Matched to Peptides |

% Protein Coveragea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture 1 | 164 | 2.3e-12 | 24 | |

| MYG_EQUBU | 103 | 2.9 e-06 | 14 | 80 |

| LACB_BOVIN | 57 | 0.12 | 10 | 37 |

Percentage of the amino acid sequence of the protein covered by the identified peptides.

One of the limitations of the FOLDS in the on-line direct infusion configuration is the use of salts and chaotropes, commonly used in sample processing, which can increase chemical noise, and reduce ionization efficiency. Additionally, as the complexity of the protein mixture increases, the confidence of protein identification using a peptide mass fingerprinting approach can decrease, and an additional separation step is often desirable. Coupling the FOLDS to reversed phase LC allows for desalting the post-digestion sample and decreases the complexity of individual MS scans facilitating more detailed analyses, such as with “shotgun” MS/MS24 or the AMT tag25 approaches. For this experiment, 10 pmol of BSA was reduced and alkylated in 8 M urea, diluted 10- fold with 12.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and mixed with trypsin. 1 pmol of the resulting sample was injected into the FOLDS. After 1 min digestion at 7000 psi, the peptide products were loaded onto a reverse-phase LC column at a flow rate of ~10 µL/min and then separated using a 20 min gradient (see Experimental section). The LC effluent was analyzed using an LCQ mass spectrometer in the MS/MS mode. High protein coverage (~70% of the amino acid sequence) was achieved and the 48 identified peptides were homogenously distributed across the protein sequence (Figure 7a), and similar to an overnight digestion.

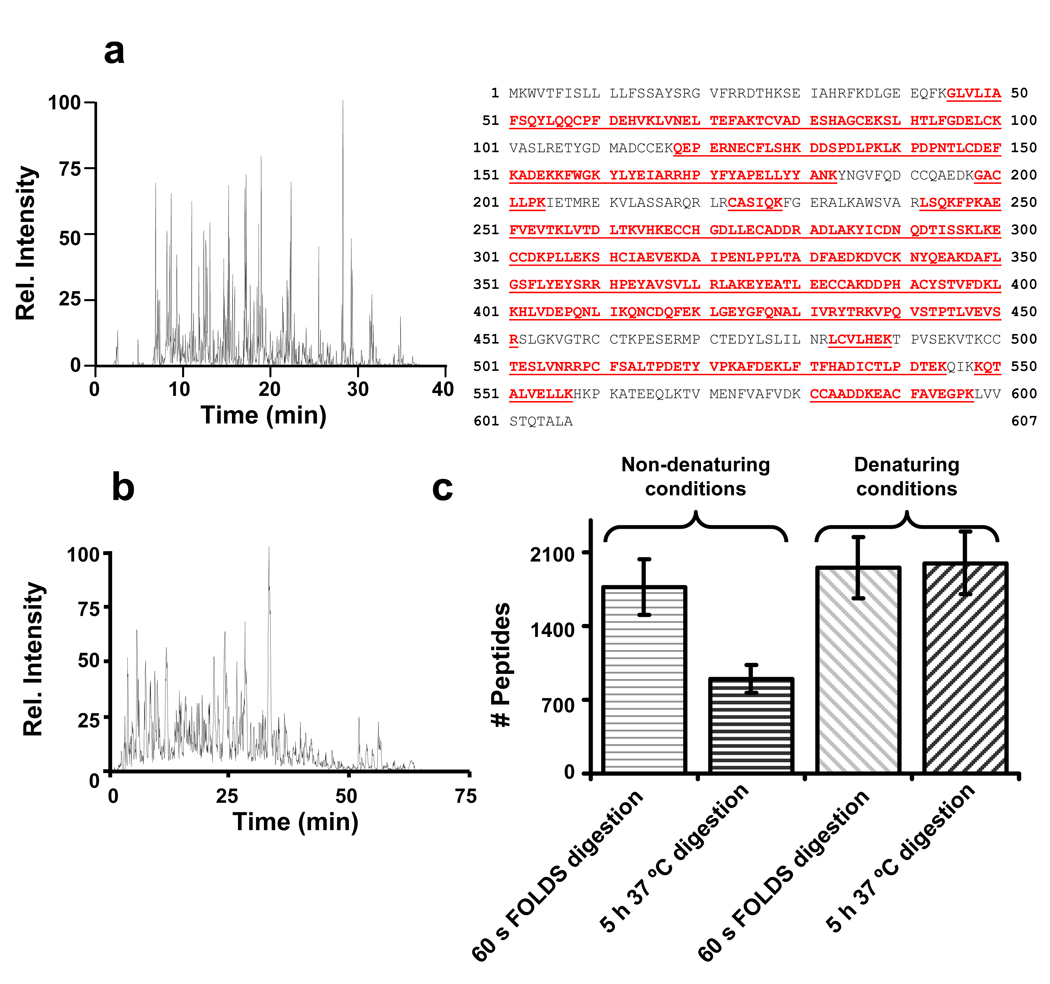

Figure 7.

Experiments with the FOLDS coupled to an RPLC-ITMS system, a) shows the base peak chromatogram obtained for 1 pmol of reduced and digested BSA after 1 min digestion. On the right, the protein coverage obtained after the MASCOT search. The portions of the sequence in red correspond to the identified peptides. b) Base peak chromatogram obtained in the LC-MS/MS analysis of Shewanella onidensis proteome sample after 1 min digestion with the FOLDS. c) Histogram comparing the number of identified peptides in the four analyzed samples at a 1 % false discovery rate following SEQUEST analysis. Horizontal line filled bars correspond to experiments without denaturation and alkyiation before digestion. Diagonal line filled bars correspond to those experiments where denaturation and alkylation was carried out before digestion. Error bars represent 15% error for one experiment.

As our previous study with myoglobin showed that pressure denatures proteins and concurrently accelerates reaction kinetics, a second experiment was performed to evaluate the effect of denaturation. S. oneidensis protein extracts were digested using a “conventional” thermomixer-based protocol and the FOLDS, with and without previous reduction and alkylation. S. oneidensis was used as the model system because bacteria are known to have a very low cysteine content26 which translates to few disulfide bridges, making it easier to study the role of pressure in protein denaturation. The use of the bacterium also allowed us to show that FOLDS is useful for analyzing complex protein mixtures. For the conventional protocol, a 10 µL aliquot containing 5 µg of S. oneidensis protein extract was digested with trypsin for 5 h at 37 °C and at ambient pressure without addition of chaotropes and without reduction/ alkylation of the proteins. For the analogous fast on-line digestion, the soluble portion of the proteome was resuspended in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate to which trypsin was added in a 1:50 enzyme:protein ratio, and then a 5 µg total protein sample was injected into the FOLDS and digested at 7000 psi for 1 min. The number of peptides identified from the conventionally-processed sample was less than the number identified from the FOLDS-processed sample. In this case, two aliquots of 25 µg of the S. oneidensis sample was reduced and alkylated in the presence of 8 M urea and then 5 µg subjected either to conventional trypsin digestion as described above or to FOLDS. In this case, the number of identified peptides with the conventional procedure that included reduction and alkylation was similar to that obtained with the FOLDS (Figure 7c). Remarkably, the number of peptides identified using FOLDS without reduction and alkylation was slightly lower compared to the number of peptides identified in experiments that involved denaturation and alkylation steps before digestion. However, the number of identifications was within the error margins expected for a shotgun proteomics experiment between different replicates.27 The number of identified cysteine-containing peptides was in the same range for all experiments. On the basis of this study, we hypothesize that in addition to accelerating digestion rates, increased pressure also acts to speed protein denaturation and facilitate formation of the complex between the enzyme molecules and the substrate, without the addition of a chaotrope. The results indicate trypsin remains active consistent with its stability for elevated temperatures 28.

Conclusions

A fast on-line digestion system (FOLDS) was evaluated in conjunction with several different high throughput proteomics platforms, using both off-line and on-line sample introduction schemes. The high pressure system accelerates proteolysis, which eliminates the need for extended incubation times for effective protein digestions. FOLDS coupled to IMS-TOF MS provides an analysis platform with the capacity to rapidly detect large numbers of peptide ions, which is useful for single protein characterization or monitoring. An automated version of FOLDS 29 could prove valuable for ultra-fast high-throughput analyses or as a diagnostic/clinical tool (e.g., quick screening or characterization of environmental samples or rapid and early detection of disease biomarkers in blood, urine, or saliva). Its implementation would also reduce costs and decrease analysis time substantially since many sample preparations steps would be eliminated without a loss of data quality. In addition, we demonstrate for the first time the application of pressurized systems for complete on-line protein digestion for LC-MS/MS proteomics experiments. The evaluation of the system for a range of applications is currently underway in our group.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Penny Colton, Dr. Ryan Kelly and Dr. Eric Livesay for helpful suggestions. Portions of this work were supported by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (RR018522), NIH National Cancer Institute (R21 CA12619-01), and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s (PNNL) Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program. PNNL is operated by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy through contract DE-AC05-76RLO1830.

Abbreviations

- DTT

Dithiothretiol

- ESI

Electrospray Ionization

- IAA

Iodoacetamide

- IMS

Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry

- IT

Ion trap

- MeOH

Methanol

- MS/MS

Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- FOLDS

Fast On-Line Digestion System

- oTOF

Orthogonal Time-of-Flight

- RP

Reversed Phase

References

- 1.Guan FY, Uboh CE, Soma LR, Birks E, Chen JW, Mitchell J, You YW, Rudy J, Xu F, Li XQ, Mbuy G. Analytical Chemistry. 2007;79:4627–4635. doi: 10.1021/ac070135o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrera M, Canas B, Pineiro C, Vazquez J, Gallardo JM. Proteomics. 2006;6:5278–5287. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Ferrer D, Capelo JL, Vazquez J. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1569–1574. doi: 10.1021/pr050112v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez-Ferrer D, Heibeck TH, Petritis K, Hixson KK, Qian W, Monroe ME, Mayampurath A, Moore RJ, Belov ME, Camp DG, 2nd, Smith RD. J Proteome Res. 2008 doi: 10.1021/pr800161x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slysz GW, Lewis DF, Schriemer DC. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1959–1966. doi: 10.1021/pr060142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slysz GW, Schriemer DC. Anal Chem. 2005;77:1572–1579. doi: 10.1021/ac048698c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh YLF, Wang HQ, Elicone C, Mark J, Martin SA, Regnier F. Analytical Chemistry. 1996;68:455–462. doi: 10.1021/ac950421c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slysz GW, Schriemer DC. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2003;17:1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MT, Lee TD, Ronk M, Hefta SA. Analytical Biochemistry. 1995;224:235–244. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheftel JC. In: High Pressure and Biotechnology. Balny C, Hayashi R, Heremans K, Masson P, editors. London, U.K: John Libbey Eurotext, Ltd; 1992. pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cano MP, Hernandez A, DeAncos B. Journal of Food Science. 1997;62:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen Y, Moore RJ, Zhao R, Blonder J, Auberry DL, Masselon C, Pasa-Tolic L, Hixson KK, Auberry KJ, Smith RD. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75:3264–3273. doi: 10.1021/ac0300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Ferrer D, Petritis K, Hixson KK, Heibeck TH, Moore RJ, Belov ME, Camp DG, 2nd, Smith RD. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3276–3281. doi: 10.1021/pr7008077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Ferrer D, Cañas B, Vázquez J, Lodeiro C, Rial-Otero R, Moura I, Capelo JL. Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2006;25:996–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen Y, Zhao R, Belov ME, Conrads TP, Anderson GA, Tang K, Pasa-Tolic L, Veenstra TD, Lipton MS, Smith RD. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:1766–1775. doi: 10.1021/ac0011336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma S, Simpson DC, Tolic N, Jaitly N, Mayampurath AM, Smith RD, Pasa-Tolic L. Journal of Proteome Research. 2007;6:602–610. doi: 10.1021/pr060354a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belov ME, Buschbach MA, Prior BC, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2451–2462. doi: 10.1021/ac0617316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clowers BH, Ibrahim YM, Prior DC, Iii WF, Belov ME, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1021/ac701648p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Ferrer D, Martinez-Bartolome S, Villar M, Campillos M, Martin-Maroto F, Vazquez J. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6853–6860. doi: 10.1021/ac049305c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates IIIJR. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams MW, Kelly RM. Biocatalysis at Extreme Temperatures; Enzyme Systems Near and Above 100 °C. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu CC, Jong R, Covey T. Journal of Chromatography A. 2003;1013:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00778-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrads TP, Anderson GA, Veenstra TD, Pasa-Tolic L, Smith RD. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:3349–3354. doi: 10.1021/ac0002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahey RC, Hunt JS, Windham GC. J Mol Evol. 1977;10:155–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01751808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resing KA, Meyer-Arendt K, Mendoza AM, Aveline-Wolf LD, Jonscher KR, Pierce KG, Old WM, Cheung HT, Russell S, Wattawa JL, Goehle GK, Knight RD, Ahn NG. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:3556–3568. doi: 10.1021/ac035229m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Havlis J, Thomas H, Sebela M, Shevchenko A. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1300–1306. doi: 10.1021/ac026136s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livesay ET Keqi, Taylor Beverley, Buschbach Michael, Hopkins Derek, Lamarche Brian, Zhao Rui, Shen Yufeng, Orton Daniel, Moore Ronald, Kelly Ryan, Udseth Harold, Smith Richard. Analytical Chemistry. 2007;80:294–302. doi: 10.1021/ac701727r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]