Abstract

Ran-GTP interacts strongly with importin-β, and this interaction promotes the release of the importin-α-nuclear localization signal cargo from importin-β. Ran-GDP also interacts with importin-β, but this interaction is 4 orders of magnitude weaker than the Ran-GTP·importin-β interaction. Here we use the yeast complement of nuclear import proteins to show that the interaction between Ran-GDP and importin-β promotes the dissociation of GDP from Ran. The release of GDP from the Ran-GDP-importin-β complex stabilizes the complex, which cannot be dissociated by importin-α. Although Ran has a higher affinity for GDP compared with GTP, Ran in complex with importin-β has a higher affinity for GTP. This feature is responsible for the generation of Ran-GTP from Ran-GDP by importin-β. Ran-binding protein-1 (RanBP1) activates this reaction by forming a trimeric complex with Ran-GDP and importin-β. Importin-α inhibits the GDP exchange reaction by sequestering importin-β, whereas RanBP1 restores the GDP nucleotide exchange by importin-β by forming a tetrameric complex with importin-β, Ran, and importin-α. The exchange is also inhibited by nuclear-transport factor-2 (NTF2). We suggest a mechanism for nuclear import, additional to the established RCC1 (Ran-guanine exchange factor)-dependent pathway that incorporates these results.

Ran (Gsp1p in yeast) is a Ras-like GTPase that regulates diverse cellular processes, including nuclear transport, mitotic spindle assembly, and post-mitotic nuclear assembly (1, 2). Like other GTPases, Ran can bind GTP and GDP. Ran-GTP is generated in the nucleus by the guanine exchange factor RCC1 (regulator of chromosome condensation 1), which is associated with the chromatin (3). Ran-GDP is produced in the cytoplasm by the activation of the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ran by RanGAP1 (GTPase-activating protein) (4) and RanBP1 (Ran-binding protein-1, Yrb1p in yeast). The compartmentalization of RanGAP1 (cytoplasm) and RCC1 (nucleus) gives rise to the asymmetric distribution of Ran-GDP (cytoplasm) and Ran-GTP (nucleus) across the nuclear envelope. This asymmetric distribution of Ran-GDP and Ran-GTP plays a central role in nucleocytoplasmic transport by mediating assembly and disassembly of import and export complexes through interaction with the nuclear import machinery (for reviews, see Refs. 5–9).

The passage of molecules into the nucleus occurs through the nuclear pore complexes (NPCs)6 (10). Nucleocytoplasmic transport is driven by a series of protein-protein interactions and involves several soluble carriers named β-karyopherins. Import carriers are called importins and export carriers are called exportins. The classical nuclear import pathway involves importin-β (Kap95p in yeast) and the adaptor protein importin-α (Kap60p in yeast). In the cytoplasm importin-β binds to importin-α. Their interaction triggers a conformational change of importin-α that increases its affinity for cargo proteins containing a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (11, 12). The translocation of the resulting complex (importin-β·importin-α·NLS) involves interactions with the NPC proteins (nucleoporins), particularly the FXFG-repeat domains (11). The protein cargo is released in the nucleus by the action of Ran-GTP, which induces the dissociation of importin-α from importin-β by forming a stable complex with importin-β. The importins are then recycled to the cytoplasm. Importin-β transfers to the cytoplasm associated with Ran-GTP, and importin-α is exported by CAS (exportin2; Cse1p in yeast) in the form of an importin-α·CAS·Ran-GTP complex (13). Importin-β and importin-α are released from their complexes in the cytoplasm by the combined action of RanBP1 and RanGAP1. Importin-β and importin-α are then able to function in a new cycle of transport, whereas Ran-GDP is transported into the nucleus by NTF2 (nuclear-transport factor-2, Ntf2p in yeast) (14). In the nucleus Ran-GDP is transformed to Ran-GTP by the action of RCC1 (3).

The complexity of the nuclear import mechanism is highlighted by the fact that it involves the active participation of soluble factors other than Ran-GTP, importin-β, and importin-α. Indeed, Ran-GDP, RanBP1, and NTF2 have been shown to be involved in the docking and translocation events of nuclear import. Chi et al. (15) have demonstrated that Ran-GDP forms a stable complex with RanBP1 and importin-β; they suggested a role for Ran-GDP in the association of the importin-β·importin-α·NLS complex with the nuclear pore and speculated that the importin-β·importin-α·NLS·Ran-GDP·RanBP1 pentameric complex was the actual translocation complex that moved through the pore. This model has also been adopted by others (16–18) who have proposed that a stable Ran-GDP-containing complex was created on nucleoporin Nup358 (also called RanBP2) and that upon displacement of the importin-β·importin-α·Ran-GDP complex from the RBH (domain homologous to RanBP1) domains of Nup358 by RanBP1, binding of NTF2 triggered translocation to the nucleus. The role of NTF2 as the factor responsible for the translocation of the transport complex through the nuclear envelope has also been proposed by Paschal et al. (19). The role of Ran-GDP and RanBP1 in nuclear import has been demonstrated by a single mutation of a cysteine residue of importin-β; the mutation was required for binding Ran-GDP·RanBP1, but not Ran-GTP·RanBP1, and inhibited the nuclear import in permeabilized cells (20). The active role of RanBP1 in nuclear import has been further demonstrated by Künzler et al. (21), who showed that mutations in the Yrb1 gene encoding the yeast ortholog of RanBP1 impair nucleocytoplasmic transport.

Despite considerable evidence for the involvement of Ran-GDP, RanBP1, and NTF2 in nuclear protein import, the precise mechanism by which these molecules regulate this process has been unknown. Here we characterize the interaction between Kap95p and Gsp1p-GDP. We show that this interaction results in GDP-to-GTP exchange on Gsp1p. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Gsp1p, Kap60p, Kap95p, Yrb1p, and Ntf2p interact to regulate the GDP-to-GTP exchange on Gsp1p. We suggest a mechanism of nuclear import additional to the RCC1-dependent pathway that incorporates our observations.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning

For clarity, the nomenclature of nuclear transport factors in human and yeast relevant to the work here is presented in Table 1. Plasmids expressing Kap95p (importin-β) and Kap60p (importin-α) as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins have been described previously (19). Gsp1p (Ran), Yrb1p (RanBP1), and Ntf2p (NTF2) genes were amplified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA and cloned as glutathione S-transferase-tagged recombinant genes using the following forward and reverse primers (restriction sites are in bold, and the start codon is in italics): Gsp1p (GenBankTM accession number AY558363), 5′-CCGGATCCATGTCAGCACCTGCTCAAAACAATG-3′ and 5′-CCGAATTCTTATAAATCAGCATCGTCTTCATCAGGTAATG-3′; Yrb1p (GenBankTM accession number AY693117), 5′-CCGAATTCCTATGTCTAGCGAAGATAAGAAACCTGTCGTC-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTAAGCCTTTTTGTTGATTTCTTGAGCTTT-3′; Ntf2p (GenBankTM accession number AY558448) 5′-CCGAATTCCTATGTCTCTCGACTTTAACACTTTGGC-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTTAAGCAGAGTAATTCAAACGGAAGATATC-3′. The Gsp1p PCR product was cleaved by BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into PGEX-KG (Novagen), which was cleaved with BamHI and EcoRI. The Yrb1p and Ntf2p PCR products were cleaved by EcoRI and XhoI and ligated into PGEX-KG (Novagen), which was cleaved with EcoRI and XhoI.

TABLE 1.

Nomenclature of soluble transport factors involved in nuclear import with their corresponding NCBI numbers in human and yeast

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

All constructs were expressed as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. The plasmids were introduced into Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) carrying the plasmid pGTf2 (Takara Bio Inc.) coding for a set of chaperones (GroES-GroEL-tig). Cells were grown in 2 liters of terrific broth (TB) medium containing 200 μg/ml ampicillin and 35 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37 °C to a cell density of 1–2 A600 (absorption at 600 nm) units. Cells were cooled down on ice, and 1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and 10 μg/ml tetracycline were added to induce expression of recombinant proteins and chaperones, respectively. After incubation (160 rpm) for 16–20 h at 18 °C, cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellets were frozen at −20 °C.

All purification steps were carried out at 5 °C. The pellets were thawed and resuspended in 50 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1× FastBreak Cell Lysis (Promega), 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 100 units of DNase. The homogenates were spun down at 25,000 × g for 1 h, and the cleared supernatants were subjected to glutathione affinity chromatography (glutathione-agarose; Scientifix). Fusion tags were cleaved using thrombin and separated by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex S200; GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the purified recombinant protein were passed once more through glutathione-Sepharose beads to remove residual traces of glutathione S-transferase and uncleaved protein. Purified proteins were equilibrated with 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl and concentrated in Amicon Ultra 10k (Millipore). Aliquots of purified proteins were snap-frozen and kept at −80 °C. For production of Ran-GDP and Gsp1p-GDP, purified proteins were incubated with a 50-fold excess of GDP and 5 mm EDTA for 40 min at 25 °C followed by the addition of 10 mm Mg2+. Proteins were then equilibrated with 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, concentrated, and snap-frozen at −80 °C.

Radiolabeled Nucleotide Assays

All such assays were performed in a total volume of 50 μl. For Gsp1p-[3H]GDP or Gsp1p-[3H]GTP exchange assays, Gsp1p-GDP (5 or 8 μm) was incubated for 40 min at 25 °C with 16 μm [3H]GDP (12.1 Ci/mmol; Amersham Biosciences) or on ice with 39 μm [3H]GTP (5.1 Ci/mmol; Amersham Biosciences) in the incubating buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.05% bovine serum albumin) in a total volume of 4.5 μl. Loading reactions were stopped by adding 0.5 μl of 100 mm MgCl2. [3H]GDP and [3H]GTP-loaded Gsp1p (5 μl) was then preincubated for 15 min at 25 °C with 45 μl of the reaction mixture. Reaction mixtures contained Kap95p, Yrb1p, Kap60p or Ntf2p, and MgCl2 (or EDTA) in the incubating buffer. Exchange reactions were started by the addition of 2 μl of 100 mm GDP or GTP. At various time points, 8-μl aliquots were filtered through BA85 nitrocellulose and washed with the rinsing buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 20 mm MgCl2). The protein-bound radioactivity retained on the filter was measured by scintillation counting and expressed as cpm units.

For Gsp1p-GDP loading assays, 5 μl of Gsp1p-GDP (5 or 8 μm) was preincubated for 15 min at 25 °C with 45 μl of the incubating buffer containing Kap95p, Yrb1p, Kap60p, or Ntf2p, and MgCl2 (or EDTA). Loading reactions were started by the addition of 2 μl of the nucleotide mixture (GDP, [3H]GDP, GTP, or [3H]GTP). At various time points protein-bound radioactivity contained in 8-μl aliquots was measured as mentioned above.

Purification of Ran·Kap95p Complex by Gel Filtration

Recombinant human Ran (1.5 mg (22)) was incubated at 25 °C for 40 min in the running buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl) supplemented with 5 mm EDTA, 0.89 μm [3H]GDP, and 1 mm GDP in a total volume of 1 ml. The loading reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 μl of 1 m MgCl2. The sample was applied to a Superdex S200 column, and gel filtration was performed in the running buffer. Fractions corresponding to purified Ran-[3H]GDP were pooled and concentrated to 0.5 ml. Purified Ran-[3H]GDP was then incubated with 4.2 mg of Kap95p in the running buffer for 30 min at 25 °C in a total volume of 1 ml. The sample was applied to a Superdex S200 column. Fractions corresponding to protein peaks were analyzed for their protein content by SDS-PAGE. The radioactivity corresponding to [3H]GDP contained in the fractions was measured by scintillation counting.

HPLC Analysis

The nucleotide-bound state of human Ran and its complex with Kap95p was assessed using isocratic HPLC. In each experiment 0.86 nmol of Ran protein was loaded onto a C18 reverse-phase column (Jupiter, Phenomenex) under ion-pair conditions in 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 10 mm tetrabutylammonium bromide, and 4% (v/v) acetonitrile. The stoichiometry of nucleotide bound was assessed using GDP and GTP nucleotide standards.

RESULTS

Kap95p (Importin-β) Promotes GDP Release and GTP Binding to Gsp1p (Ran)

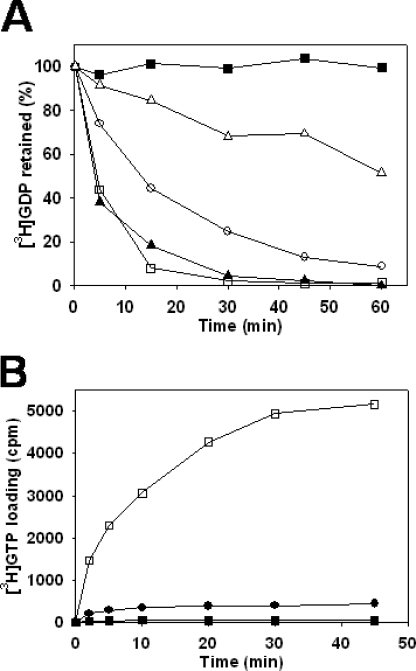

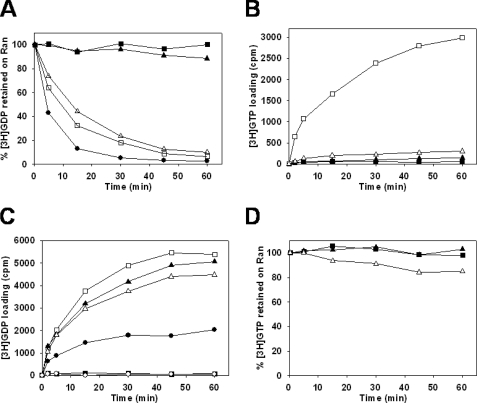

To investigate the functional consequences of the Ran-GDP·Kap95p interaction (22), we examined the effect of Kap95p on the binding of guanine nucleotides to Gsp1p. First, we examined the effect of Kap95p on the Gsp1p-GDP dissociation by monitoring the loss of Gsp1p-bound [3H]GDP in solution binding assays containing Gsp1p-[3H]GDP and excess Kap95p and GDP (Fig. 1A). In the binding buffer alone containing 1 mm Mg2+, Gsp1p-[3H]GDP was stable over 60 min, whereas it was strongly destabilized in the presence of EDTA, consistent with previous observations (3, 23). In 1 mm Mg2+, Kap95p promoted Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociation. Because the nucleotide binding of Ran depends on Mg2+ (24), we examined its effect on the GDP exchange activity of Kap95p. As expected, the release of [3H]GDP from Gsp1p by Kap95p was inhibited by increasing concentrations of Mg2+ (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Kap95p (importin-β) promotes GDP release from Gsp1p (Ran) and the selective binding of GTP. A, Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p; effect of the Mg2+ concentration. Gsp1p (0.8 μm) preloaded with [3H]GDP was incubated in the binding buffer in the presence of 10 mm EDTA (closed triangles) or 1 mm Mg2+ (closed squares), or in the binding buffer with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p in the presence of 1, 3, or 10 mm Mg2+ (open squares, open circles, and open triangles, respectively). After 15 min of incubation, 2 mm GDP was added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring radioactivity. B, [3H]GTP loading onto Gsp1p in the presence of Kap95p. Gsp1p-GDP (0.8 μm) was incubated in the binding buffer in the presence of 10 mm EDTA (closed circle) or 1 mm Mg2+ (closed squares), or in the binding buffer with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p in the presence of 1 mm Mg2+ (open squares). After 15 min of incubation, both GDP and [3H]GTP were added at 4 μm to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring radioactivity.

We next examined the effect of Kap95p on the loading of nucleotides on Gsp1p by incubating Gsp1p-GDP with equal amounts of [3H]GTP and GDP (Fig. 1B). In the absence of Kap95p in the binding buffer containing 1 mm Mg2+, as expected, no loading of [3H]GTP was observed. Kap95p, when compared with EDTA, caused high [3H]GTP loading on Gsp1p in the presence of 1 mm Mg2+. Ran has a 10-fold higher affinity for GDP compared with GTP (23); therefore, this result suggested that upon formation of the Kap95p·Gsp1p complex, Gsp1p adopted a conformational state that favored the binding of GTP over GDP.

Jointly, the results demonstrate that Kap95p promotes the conversion of Gsp1p-GDP to Gsp1p-GTP in vitro. Additional experiments demonstrated that Kap95 also induced the nucleotide exchange of human Ran with equal effectiveness (data not shown), consistent with the high degree of conservation between the human and yeast nuclear import pathways (6).

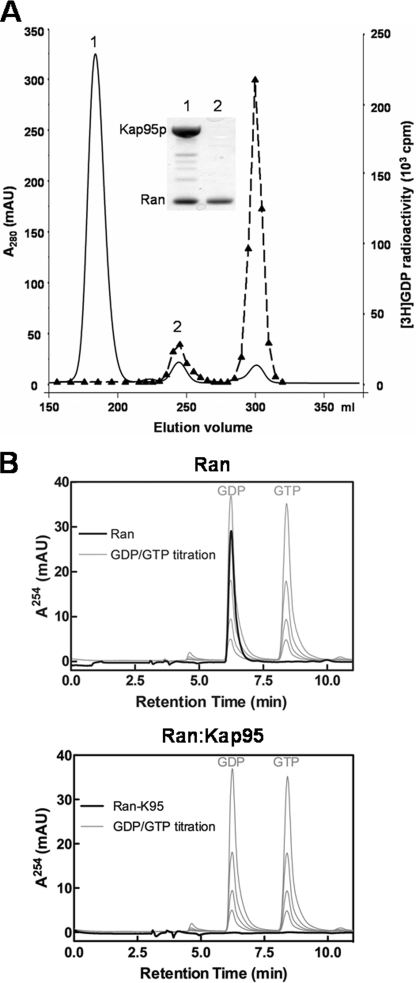

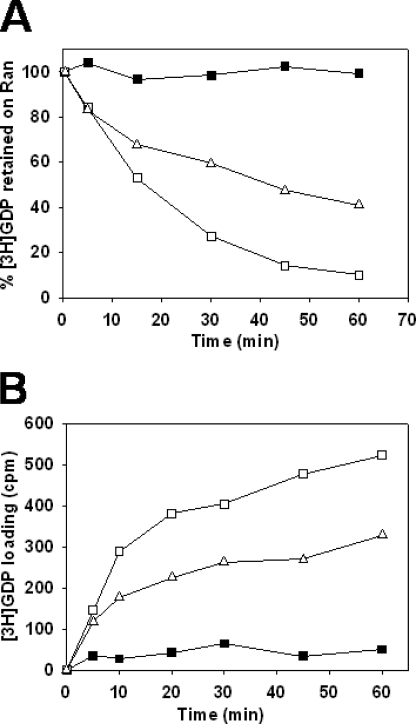

Nucleotide-free Ran and Kap95p (Importin-β) Form a Stable Complex That Resists Dissociation by Kap60p (Importin-α)

During the GDP nucleotide exchange occurring on the Ran·Gsp1p·Kap95p complex, Ran·Gsp1p must pass through an intermediate free of nucleotide. We analyzed the stability of the nucleotide-free human Ran·Kap95p complex (Fig. 2A). Kap95p was incubated with an excess of Ran preloaded with [3H]GDP, and the sample was resolved by gel filtration. Two protein peaks were observed, one corresponding to a 1:1 complex between Ran and Kap95p and another one corresponding to free Ran. The radioactivity profile showed two peaks, one overlapping the free Ran protein peak the other one corresponding to free GDP. The integration of the radioactivity found in the two peaks corresponded to the initial activity associated with Ran-[3H]GDP before the addition to Kap95p. No radioactivity was detected in the protein peak containing the Ran·Kap95p complex, demonstrating that the addition of Kap95p to Ran-[3H]GDP generated a stable 1:1 complex between Kap95p and nucleotide-free Ran. To confirm the nucleotide free status of the Ran·Kap95p complex, we conducted a similar experiment with Ran preloaded with GDP instead of [3H]GDP. We analyzed the two resultant protein peaks by reverse-phase HPLC (Fig. 2B). The HPLC data confirmed that Ran was associated with GDP in a 1:1 stoichiometry and that GDP was excluded from the Ran·Kap95 complex.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of the Ran·Kap95p (importin-β) complex by gel filtration chromatography. A, excess of purified recombinant Ran preloaded with [3H]GDP was incubated with purified Kap95p for 30 min at 25 °C in the running buffer. The sample was then subjected to size exclusion chromatography on Superdex S200 column. Fractions corresponding to protein peak 1 (Ran·Kap95 complex) and protein peak 2 (Ran alone) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (inset). Lanes 1 and 2 correspond to peak number 1 and 2, respectively. [3H]GDP radioactivity was measured for each fraction (closed triangles). mAU, milliabsorbance units. B, analysis of the nucleotide-bound state of Ran alone (upper panel) and its complex with Kap95p (lower panel) by reverse-phase HPLC. Standards of GDP and GTP nucleotide were titrated (light gray) to assess the stoichiometry. Ran alone was consistent with a 1:1 stoichiometry of bound nucleotide.

To further investigate the stability of the Ran·Kap95p complex, we examined the ability of Kap60p to dissociate the complex (Fig. 3). Excess of Kap60p protein was added to Ran·Kap95p complex in the binding buffer alone or in the presence of excess of Mg2+ and GDP. Kap60p was unable to dissociate the Ran·Kap95p complex in buffer alone, implying that under these conditions the affinity between nucleotide-free Ran and Kap95p was higher than between Kap60p and Kap95p (3 × 10−8 m−1 for importin-α·importin-β (25)). However, the addition of excess of Mg2+ and GDP allowed Kap60p to dissociate the Ran·Kap95p complex, suggesting that GDP and Mg2+ destabilized the Ran·Kap95p interaction. Together, these results demonstrated that upon binding with Ran-GDP, Kap95p is able to release the nucleotide and thereby increase the affinity between Kap95p and nucleotide-free Ran such that they cannot be dissociated by Kap60p.

FIGURE 3.

Dissociation of the Ran·Kap95p (importin-β) complex by Kap60p (importin-α). 1 mg of Ran·Kap95p and 2 mg of Kap60p were incubated for 30 min at 25 °C in a total volume of 0.5 ml. The sample was applied to a Superdex 75 column, and gel filtration was performed in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl. Fractions corresponding to peaks numbers 1 and 2 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (inset). Lanes 1 and 2 correspond to peaks number 1 and 2, respectively. Lane 3 corresponds to peak number 1 obtained in a similar experiment done without addition of Kap60p. A, Ran·Kap95p complex resists dissociation by Kap60p in the absence of Mg2+ and GDP. B, Mg2+ (2 mm) and GDP (5 mm) induce dissociation of Ran·Kap95p complex by Kap60p. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

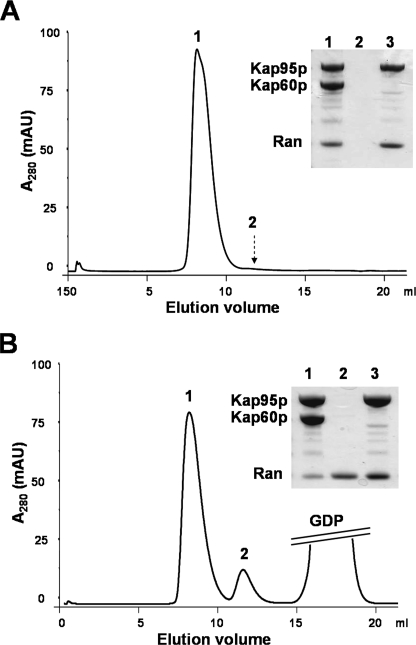

Yrb1p (RanBP1) Co-activates the GDP Nucleotide Exchange by Kap95p (Importin-β)

Ran-GDP has the ability to form a trimeric complex with RanBP1 and importin-β (15). It was, therefore, of interest to assess the GDP exchange activity of Gsp1p-GDP in the presence of Yrb1p and Kap95p. Yrb1p promoted Kap95p-mediated dissociation of Gsp1p-[3H]GDP, whereas in the absence of Kap95p, no dissociation was observed with or without Yrb1p (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Yrb1p (RanBP1) is a co-activator of the GDP nucleotide exchange by Kap95p (importin-β). A, Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p and Yrb1p. Gsp1p (0.5 μm) preloaded with [3H]GDP was incubated in the binding buffer containing 2 mm of Mg2+ with no addition (closed square) or with the addition of 0.8 μm Yrb1p alone (open circles), 0.8 μm Kap95p alone (open squares), or 0.8 μm Kap95p and 0.8 μm Yrb1p (closed triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 2 mm GDP was added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring protein-bound radioactivity. B, [3H]GTP loading onto Gsp1p in presence of Kap95p and Yrb1p. Gsp1p-GDP (0.5 μm) was incubated in the binding buffer containing 2 mm Mg2+ with no addition (closed squares) or with the addition of 0.8 μm Yrb1p alone (open circles), 0.8 μm Kap95p alone (open squares), or 0.8 μm Yrb1p and 0.8 μm Kap95p (closed triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 4 μm concentrations of both GDP and [3H]GTP were added to the samples, and incubation was carried out for the indicated times before measuring protein-bound radioactivity.

We then carried out nucleotide loading assays on Gsp1p in complex with Kap95p and/or Yrb1p and with equal amounts of [3H]GTP and GDP (Fig. 4B). In the presence of Kap95p, Yrb1p significantly promoted the [3H]GTP loading on Gsp1p, exceeding [3H]GTP loading when only Gsp1p-GDP and Kap95p were present. The data showed that virtually 100% of Gsp1p of the Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap95p complex was loaded with [3H]GTP upon GDP nucleotide exchange. Consistent with the data shown above (Fig. 4A), Yrb1p had no effect on the loading of [3H]GTP on Gsp1p in the absence of Kap95p. These results established that the formation of the Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap95p complex induced the release of GDP from Gsp1p and promoted the selective binding of GTP.

Kap60p (Importin-α) Inhibits the GDP Nucleotide Exchange by Kap95p (Importin-β), Whereas Yrb1p (RanBP1) Counteracts This Inhibition

In the presence of 2 mm Mg2+, the release of [3H]GDP from Gsp1p by Kap95p was strongly inhibited by Kap60p (Fig. 5A). However, the addition of Yrb1p counteracted this inhibition, nearly restoring the rate of dissociation of Gsp1p-GDP obtained in presence of Kap95p alone.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Kap60p (importin-α) and Yrb1p (RanBP1) on Kap95p (importin-β)-mediated GDP nucleotide exchange. All assays were carried out at 25 °C in the binding buffer containing 2 mm Mg2+ unless stated otherwise. A, Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p. Gsp1p preloaded with [3H]GDP was incubated in the binding buffer with no other protein (closed squares) or with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p alone (open squares), 2.1 μm Kap95p and 2 μm Yrb1p (closed circles), 2.1 μm Kap95p and 3 μm Kap60p (closed triangles), or 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p and 2 μm Yrb1p (open triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 2 mm GDP was added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring radioactivity. B, [3H]GTP loading onto Gsp1p in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p. Gsp1p-GDP was incubated in the binding buffer with no other protein (closed squares) or with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p alone (open squares), 2.1 μm Kap95p and 3 μm Kap60p (closed triangles), or 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, and 2 μm Yrb1p (open triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 1.6 μm concentrations of GDP and [3H]GTP were added to all samples. The samples were incubated for the indicated times before measuring radioactivity. C, effect of the GTP concentration on the [3H]GDP loading onto Gsp1p in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p. Gsp1p-GDP was incubated in the binding buffer with no other protein (closed squares) or with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, and 2 μm Yrb1p (closed triangles, open triangles, closed circles, and open circles). As a loading control, Gsp1p-GDP was incubated in the binding buffer in the presence of 10 mm EDTA (open squares). After 15 min of incubation, 1.6 μm [3H]GDP was added to all samples with no other nucleotide (closed squares, open squares, closed triangles) or with the addition of 1.6 μm GTP (open triangles), 25 μm GTP (closed circles), or 480 μm GTP (open circles). The samples were incubated for the indicated time before measuring radioactivity. D, Gsp1p-[3H]GTP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p. Gsp1p preloaded with [3H]GTP was incubated in the binding buffer with no other protein (closed squares) or with 2.1 μm Kap95p and 2 μm Yrb1p (closed triangles) or 2.1 μm Kap95p, 2 μm Yrb1p, and 3 μm Kap60p (open triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 2 mm GTP was added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring radioactivity.

We carried out nucleotide loading assays on Gsp1p in the Gsp1p·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p complex upon GDP release. In loading assays with 1.6 μm [3H]GTP and GDP, the amount of Gsp1p loaded with [3H]GTP in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p (Fig. 5B) was small compared with the amount that underwent GDP dissociation (Fig. 5A). Indeed, after 1 h of incubation, ∼95% of Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociated in the presence of Kap95p, Ybp1p, and Kap60p, whereas under the same conditions only 10% of Gsp1p was loaded with [3H]GTP. This provided evidence that Gsp1p-GDP, Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p formed a tetrameric complex and that the conformation taken by Gsp1p in this complex favored the binding of GDP over GTP at equimolar concentrations of 1.6 μm. For technical reasons it was not possible to study the loading of [3H]GTP at physiological concentrations (1.6 μm GDP, 470 μm GTP (26)). We, therefore, instead monitored the loading of [3H]GDP in the presence of a gradient of GTP concentration reaching 470 μm at its maximum (Fig. 5C). The results showed that in the presence of 1.6 μm [3H]GDP and 470 μm GTP, the loading of [3H]GDP was totally inhibited, indicating that Gsp1p was fully loaded with GTP. These results indicated that at physiological concentrations of nucleotides, generation of Gsp1p-GTP from Gsp1p-GDP occurred when Gsp1p was associated with Kap95p, Kap60p, and Yrb1p in a tetrameric complex. We next investigated the status of Kap60p upon loading of Gsp1p with GTP in the Gsp1p·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p complex. We monitored the effect of Kap60p on the dissociation of Gsp1p-[3H]GTP in the presence of Yrb1p and Kap95p. The absence of Gsp1p-[3H]GTP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p and Yrb1p (Fig. 5D) confirmed our previous results establishing that the conformation of Gsp1p in the Gsp1p·Yrb1p·Kap95p complex favors the selective binding of GTP over GDP (Fig. 3). Only a slight release of [3H]GTP from Gsp1p was observed when Kap60p was added to Yrb1p and Kap95p. This result clearly indicated that Kap60p did not form a stable complex with Gsp1p-[3H]GTP, Kap95p, and Yrb1p.

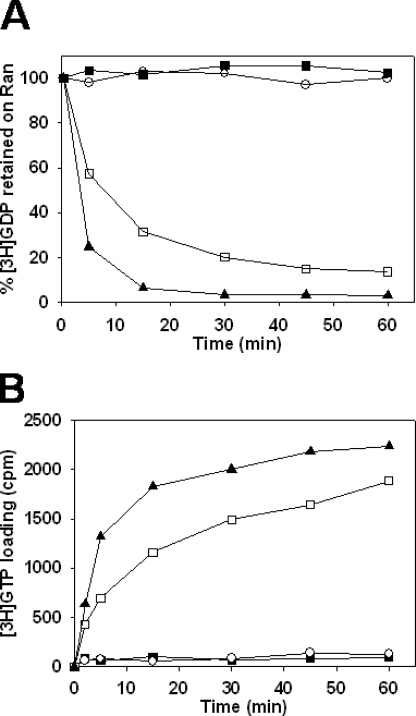

Ntf2p (NTF2) Inhibits Gsp1p-GDP (Ran-GDP) Nucleotide Exchange in the Presence of Kap95p (Importin-β), Yrb1p (RanBP1), and Kap60p (Importin-α)

NTF2 is a transport factor that imports Ran-GDP to the nucleus (14). NTF2 is an inhibitor of Ran-GDP dissociation (27), and it is involved in the formation of a pentameric complex with Gsp1p-GDP, Kap60p, Kap95p, and Nup36p, a nucleoporin containing an RBH domain (28). We, therefore, investigated the effect of Ntf2p on the GDP nucleotide exchange by Kap95p in presence of Kap60p and Yrb1p. We found that Ntf2p partially inhibited both GDP dissociation and GTP loading on Gsp1p (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of Ntf2p (NTF2) on Kap95p (importin-β)-mediated GDP nucleotide exchange. All assays were carried out at 25 °C in the binding buffer containing 2 mm Mg2+. A, Gsp1p-[3H]GDP dissociation in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, Yrb1p, and Ntf2p. Gsp1p (0.8 μm) preloaded with [3H]GDP was incubated with no other protein (closed squares) or with the addition of 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, and 2 μm Yrb1p (open squares) or 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, 2 μm Yrb1p, and 5 μm Ntf2p (open triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 2 mm GDP was added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring protein-bound radioactivity. B, [3H]GTP loading onto Gsp1p in the presence of Kap95p, Kap60p, Yrb1p, and Ntf2p. Gsp1p-GDP (0.8 μm) was incubated with no other protein (closed square), with 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, and 2 μm Yrb1p (open squares), or with 2.1 μm Kap95p, 3 μm Kap60p, 2 μm Yrb1p, and 5 μm Ntf2p (open triangles). After 15 min of incubation, 1.6 μm GDP and 4 μm [3H]GTP were added to the samples, and they were incubated for the indicated times before measuring protein-bound radioactivity.

DISCUSSION

Kap95p (Importin-β) as a Nucleotide Exchange Factor; Comparison with Nucleotide Exchange Factor RCC1

The RCC1-dependent nuclear import pathway is the accepted mechanism for nucleocytoplasmic movement of cargo by importin-β and importin-α (2, 9, 29–32). However, this mechanism alone does not explain the involvement of Ran-GDP, RanBP1, and NTF2 in the docking and translocation events of nuclear import (15–21, 33–40). Here, we describe in vitro interactions between the yeast counterparts of these proteins, Kap95p, Kap60p, Gsp1p, Yrb1p, and Ntf2p, and the results suggest the possibility that in addition to the RCC1-dependent pathway, nuclear import could also be facilitated in at least some circumstances by Kap95p (importin-β)-mediated nucleotide exchange. Consistent with this possibility, it is interesting to note that some cell types have been reported to lack RCC1 (7).

Our results demonstrate that Kap95p (importin-β) induces the GDP-to-GTP exchange on Gsp1p (Ran), mimicking the activity of the known guanine exchange factor RCC1 (Fig. 1). However, although RCC1 has almost no preference for the nucleotide state of Ran and catalyzes the nucleotide exchange in both directions (23), nucleotide exchange by Kap95p (importin-β) is unidirectional because of the stable association of Kap95p (importin-β) with Gsp1p-GTP (Ran-GTP). The stability of the nucleotide-free Ran·Kap95p complex, demonstrated by the inability of Kap60p to dissociate it (Fig. 3), is probably the feature that accounts for the high affinity of Ran-GTP for Kap95p (importin-β) compared with Ran-GDP and, therefore, for the unidirectional path of the nucleotide exchange.

RCC1 and Kap95p share two interesting similarities with regard to their GDP nucleotide exchange activity. First, both RCC1 and Kap95p have a weak affinity for Ran-GDP. The reaction between Ran-GDP and RCC1 has a Km of 1.1 μm (23), whereas the interaction between Ran-GDP and importin-β has a KD of 2 μm (22). Another remarkable similarity between Kap95p and RCC1 is their ability to form a stable complex with nucleotide-free Ran. In the absence of Mg2+ and free nucleotides, RCC1 mixed with Ran-GDP or Ran-GTP forms a stable complex with nucleotide-free Ran (24). We show that under similar conditions Kap95p mixed with Ran-GDP forms a stable complex with nucleotide-free Ran (Fig. 2). The ability to form a stable complex with nucleotide-free Ran is the feature that confers to both RCC1 and Kap95p their nucleotide exchange activity. GDP and Mg2+, which stabilize the Ran-GDP association, dissociate RCC1·Ran complex when present in excess (24). We show similar GDP and Mg2+ dependence of the stability of the Gsp1p·Kap95p complex (Fig. 3). Increased concentration of Mg2+ inhibits the nucleotide exchange of Ran by RCC1 (24) and of Gsp1p by Kap95p (Fig. 1).

We do not consider it possible to directly compare the catalytic activities of Kap95p and RCC1 because their mode of action is different. RCC1 works as an enzyme and requires a high turnover to efficiently convert free Ran-GDP to Ran-GTP in the nucleus. The rate of the reaction depends of both Ran-GDP and RCC1 concentrations (23). By contrast, Kap95p does not work as an enzyme because it remains associated with the product. Indeed, in our assays (Fig. 5) Kap95p nucleotide exchange activity occurs in a tetramer complex (Kap95p·Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap60p), and the reaction gives rise to free Kap60p and Kap95p·Gsp1p-GTP·Yrb1p trimer. The rate of the reaction does not depend of the concentration of Ran-GDP and Kap95 because it occurs in a pre-established complex that travels from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. It most probably depends of the biochemical environment specific to the interior of nuclear pore (FXFG repeats and ionic strength).

Our previous research demonstrated the formation of a stable Ran-GDP·Kap95 complex (22). Here, we show that Kap95 can also form a complex with free Ran that remains stable in the absence of free Mg2+ and GDP (Fig. 3).

Kap60p (Importin-α), Yrb1p (RanBP1), and Ntf2p (NTF2) Regulate the GDP Nucleotide Exchange Reaction by the Gsp1p-GDP·Kap95p (Ran-GDP·Importin-β) Complex

The observation that the interaction of Gsp1p-GDP with Kap95p leads to the generation of the Gsp1p-GTP·Kap95p complex in vitro suggests that such a reaction could occur in vivo. Such a reaction would be undesirable in the cytoplasm but is unlikely because of the high local concentration of Kap60p, which inhibits the GDP nucleotide exchange by Kap95p (Figs. 3B and 5A), consistent with the higher affinity between importin-β and importin-α (1.1 × 10−8 m, (25)) than between Ran-GDP and importin-β (2 μm, (22)).

Yrb1p (RanBP1) has the opposite effect to Kap60p on the GDP nucleotide exchange by Kap95p, strongly enhancing Gsp1p·GDP dissociation and selective binding of GTP (Fig. 4). It acts as a co-activator of Kap95p because it has no effect on the GDP nucleotide exchange in the absence of Kap95p.

The human counterparts of Gsp1p-GDP, Yrb1p, Kap95p, and Kap60p have been reported to form a tetramer that may be involved in the translocation of cargo proteins across the NPC (15, 17). Our results show that GDP dissociation activity occurs on Gsp1p in the presence of Yrb1p, Kap95p, and Kap60p (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the loading of [3H]GTP was very weak in the presence of equal amounts of GDP. This contrasts with the loading of [3H]GTP occurring on the Gsp1p·Yrb1p·Kap95p complex (Fig. 4B) and demonstrates that in the Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p complex, Kap60p exerts a strong influence on the conformation taken by Gsp1p, forcing it toward a conformation prone to GDP binding. Our Gsp1p loading experiments with [3H]GDP and various concentrations of GTP show that GDP and GTP are competitors in terms of Gsp1p binding and that at physiological concentrations of GDP and GTP, 100% of Gsp1p is associated with GTP. Given that Kap60p does not form a stable complex with Gsp1p, Yrb1p, and Kap95p in the presence of GTP (Fig. 5D), one can predict that the binding of GTP to Gsp1p·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p induces the dissociation of Kap60p from the complex.

NTF2 has been shown to function as a Ran-GDP dissociation inhibitor (27). Our data (Fig. 6) do not allow one to distinguish if the inhibitory activity of Ntf2p on the GDP nucleotide exchange occurs through the formation of a pentameric complex with Gsp1p, Yrb1p, Kap95p, and Kap60p or if it occurs through the formation of a dimer with Gsp1p-GDP.

Biological Significance of the Nucleotide Exchange Activity of Kap95p (Importin-β)

Is the GDP nucleotide exchange activity of Kap95p described here of relevance to nucleocytoplasmic transport in vivo? A number of research groups have suggested that a nucleotide exchange reaction can occur locally at the NPCs, independently of RCC1 (11, 15, 17, 33, 36, 41, 42). For example, Chi et al. (15) proposed a model in which importin-β·NLS·importin-α·Ran-GDP·RanBP1 is the translocation complex that moves through the pore. They suggested that RanBP2 (Nup358), a nucleoporin localized at the cytoplasmic surface of the NPC, is the site of a series of docking, undocking, diffusion, and redocking events of the translocation complex and that at some point after docking, an exchange reaction to replace the GDP with GTP on Ran could occur, catalyzed by an unknown factor. In this model newly formed Ran-GTP releases the receptor complex from the docking site and is rapidly hydrolyzed by the concerted action of RanBP1 and RanGAP to allow redocking. Our data fit perfectly with such a model because we show that in the presence of physiological concentrations of GDP and GTP, conversion of Ran-GDP to Ran-GTP occurs in the Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p complex.

Another model consistent with our results involving the formation of a translocation complex including Ran-GDP and RanBP1 has been proposed by Melchior and Gerace (17). In this model, upon binding of the Ran-GTP·importin-β complex to RanBP2 (Nup358), the interaction of importin-α with importin-β induces GTP hydrolysis by the RanBP2-associated RanGAP1, giving rise to a stable Ran-GDP-containing transport complex with RanBP2. RanBP1 dissociates the complex from RanBP2, and the interaction with NTF2 induces translocation of the complex. Once the import complex has reached the nucleoplasm, either conversion of Ran-GDP to Ran-GTP in the complex or its replacement by free Ran-GTP produced by chromatin-bound RCC1 (36) leads to complex disassembly. In addition to the RCC1-dependent pathway being operative, our data are consistent with the former mechanism also being a possibility. In the vicinity of the nuclear pore, it is difficult to conceive how free Ran-GTP would replace Ran-GDP in the Ran-GDP·RanBP1·importin-β·importin-α complex because both Ran-GDP·RanBP1·importin-β·importin-α and Ran-GDP·RanBP1·importin-β complexes are stable and because the affinities of Ran-GDP and Ran-GTP for importin-β in presence of RanBP1 are indistinguishable (15). Therefore, in situ formation of Ran-GTP by the nucleotide exchange activity of importin-β (Kap95p) in the vicinity of the nuclear pore is a plausible event. NTF2 could then be a factor that protects the import complex from premature dissociation via importin-β (Kap95p)-mediated nucleotide exchange. Although the inhibition by Ntf2p of the conversion of Gsp1p-GDP to Gsp1p-GTP in the Gsp1p-GDP·Yrb1p·Kap95p·Kap60p complex is not fully efficient in our assays, one cannot exclude the possibility that the inhibition would be more efficient in presence of nucleoporins, particularly the FXFG repeat motifs that bind both NTF2 and importin-β (11, 43).

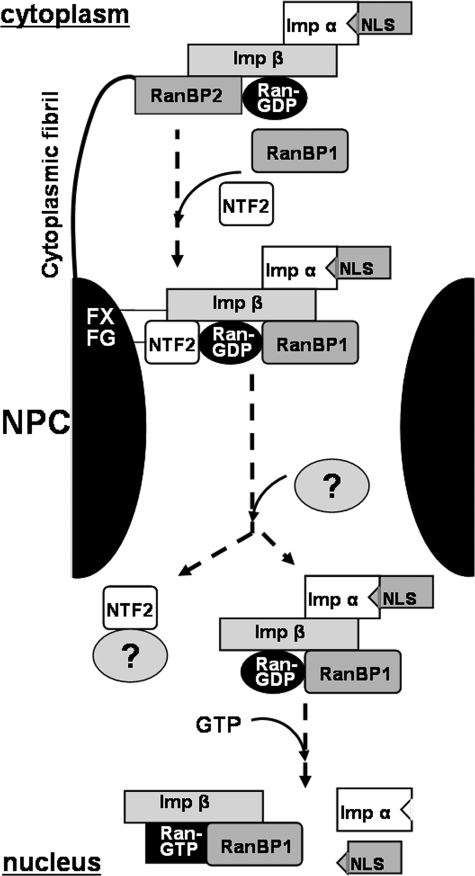

Fig. 7 shows a hypothetical model for nuclear protein import adapted from the models proposed previously (17, 44), which involves in situ GDP nucleotide exchange. In our model, which uses the more common human nomenclature for the nuclear import proteins, a Ran-GDP·RanBP1·importin-β·importin-α·NLS complex produced in the cytoplasm would interact with NTF2, leading to two effects (i) to generate the translocation of the complex by interacting with the FXFG repeats at the NPC and (ii) to protect the complex against in situ GDP nucleotide exchange. Arriving in the nucleus, NTF2 would be displaced by an unknown factor, rendering the cargo complex ready for GDP exchange. Subsequent to Ran-GTP formation, importin-α and NLS would dissociate from the complex, giving rise to a Ran-GTP·RanBP1·importin-β complex. Such a complex has been detected in vivo in the nucleus (40).

FIGURE 7.

Hypothetical model for the cargo complex disassembly in the nucleus via importin-β-mediated GDP nucleotide exchange. The nomenclature for human proteins is used in the figure; see Table 1 for the corresponding yeast counterparts. Imp α, importin-α; Imp β, importin-β; NLS, protein cargo with nuclear localization signal; NPC, nuclear pore complex including cytoplasmic fibril and Ran-binding protein 2 (RanBP2); FXFG, FXFG repeat motifs of nucleoporins that bind both NTF2 and importin-β. See under “Discussion” for other details.

Our model confers a biochemical function to RanBP1 in the nucleus. The requirement for RanBP1 in nuclear import has been demonstrated by many researchers; however, its role in this part of the pathway has remained obscure (15, 20, 34, 35, 39, 40). In our model the biochemical function of RanBP1 in the nucleus is to co-activate the GDP exchange by importin-β in the import complex. This function is accomplished through two biochemical effects; that is, the formation of a tetrameric complex that allows the association of Ran-GDP with the importin-β·importin-α complex and the stimulation of GDP dissociation from Ran followed by the formation of Ran-GTP. In combination with its function as RanGAP co-activator, RanBP1 could be seen as an adaptor of Ran, allowing the regulation of its nucleotide-bound status by different factors. Given the high occurrence of RBH domains in nucleoporins and their similar biochemical characteristic compared with RanBP1 (45), it would be interesting to test these domains for their potential to have a role in nucleotide exchange.

Our model of cargo complex disassembly involving the in situ formation of Ran-GTP in the vicinity of the nuclear pore can easily co-occur with the accepted model featuring free Ran-GTP produced by chromatin-bound RCC1 that dissociates the cargo from importin-β. Interestingly, there is no obvious ortholog of RCC1 in plants (46), and loss of RCC1 function in a temperature-sensitive yeast mutant leads to only a decrease of nuclear import efficiency in vivo (47). These observations suggest the existence of a nuclear import pathway independent of RCC1, which could correspond to the pathway we describe here. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that RanBP1 mutants are defective in nuclear import (35). A mechanism involving an in situ formation of Ran-GTP in the transport complex would present the advantage of being independent of RCC1 and Ran-GTP, two versatile proteins that are involved in many vital functions in the cell other than nucleocytoplasmic transport, such as chromatin condensation, mitosis regulation, spindle assembly, and post-mitotic nuclear envelope assembly (2, 48). In different physiological stages of the cell, their concentrations may vary significantly. For example, RCC1 is absent from frog sperm chromatin (7) and is inactivated at the end of the S phase (49). A mechanism of cargo disassembly independent of RCC1 and free Ran-GTP would ensure the maintenance of a basal nuclear import activity independent of the physiological stage of the cell.

In summary, we have characterized new biochemical interactions between soluble factors involved in nuclear import. Our data obtained in vitro suggest that these interactions may have an important role in the disassembly of cargo complex in the nucleus, although the function remains to be demonstrated in vivo. The determination of the structure of the complex of Ran-GDP, RanBP1, importin-β, and importin-α could allow the design of mutants that would block the nucleotide exchange occurring on the complex and could be used as probes for in vivo experiments.

The model described in this paper answers many questions raised with regard to the factors responsible for the nucleocytoplasmic exchange observed at the NPC and to the function of RanBP1 in the nucleus. Given the high occurrence of RBH domains in nucleoporins and their similar biochemical characteristic compared with RanBP1 (45), it would be interesting to test these RanBP domains for their potential to have a role in nucleotide exchange.

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Grant (to B. K., B. J. C., and T. G. L.) and by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Integrative Legume Research (to B. J. C.).

- NPC

- nuclear pore complex

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- NTF2

- nuclear-transport factor-2

- RBH

- domain homologous to RanBP1

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dasso M. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12,R502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph J. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119,3481–3484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff F. R., Ponstingl H. (1991) Nature 354,80–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischoff F. R., Klebe C., Kretschmer J., Wittinghofer A., Ponstingl H. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91,2587–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melchior F., Gerace L. (1995) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7,310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Görlich D., Kutay U. (1999) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15,607–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macara I. G. (2001) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65,570–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chook Y. M., Blobel G. (2001) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11,703–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8,195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim R. Y., Ullman K. S., Fahrenkrog B. (2008) Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 267,299–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rexach M., Blobel G. (1995) Cell 83,683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobe B. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6,388–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutay U., Bischoff F. R., Kostka S., Kraft R., Görlich D. (1997) Cell 90,1061–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribbeck K., Lipowsky G., Kent H. M., Stewart M., Görlich D. (1998) EMBO J. 17,6587–6598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi N. C., Adam E. J., Visser G. D., Adam S. A. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135,559–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delphin C., Guan T., Melchior F., Gerace L. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8,2379–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melchior F., Gerace L. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8,175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaseen N. R., Blobel G. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96,5516–5521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paschal B. M., Delphin C., Gerace L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93,7679–7683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi N. C., Adam E. J., Adam S. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272,6818–6822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Künzler M., Trueheart J., Sette C., Hurt E., Thorner J. (2001) Genetics 157,1089–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forwood J. K., Lonhienne T. G., Marfori M., Robin G., Meng W., Guncar G., Liu S. M., Stewart M., Carroll B. J., Kobe B. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383,772–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klebe C., Bischoff F. R., Ponstingl H., Wittinghofer A. (1995) Biochemistry 34,639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bischoff F. R., Ponstingl H. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88,10830–10834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catimel B., Teh T., Fontes M. R., Jennings I. G., Jans D. A., Howlett G. J., Nice E. C., Kobe B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276,34189–34198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riddick G., Macara I. G. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168,1027–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada M., Tachibana T., Imamoto N., Yoneda Y. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8,1339–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nehrbass U., Blobel G. (1996) Science 272,120–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madrid A. S., Weis K. (2006) Chromosoma 115,98–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried H., Kutay U. (2003) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60,1659–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harel A., Forbes D. J. (2004) Mol. Cell 16,319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Görlich D., Mattaj I. W. (1996) Science 271,1513–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore M. S., Blobel G. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91,10212–10216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbett A. H., Koepp D. M., Schlenstedt G., Lee M. S., Hopper A. K., Silver P. A. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130,1017–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlenstedt G., Wong D. H., Koepp D. M., Silver P. A. (1995) EMBO J. 14,5367–5378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Görlich D., Panté N., Kutay U., Aebi U., Bischoff F. R. (1996) EMBO J. 15,5584–5594 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lounsbury K. M., Richards S. A., Perlungher R. R., Macara I. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271,2357–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong D. H., Corbett A. H., Kent H. M., Stewart M., Silver P. A. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17,3755–3767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Künzler M., Gerstberger T., Stutz F., Bischoff F. R., Hurt E. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20,4295–4308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plafker K., Macara I. G. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20,3510–3521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickmanns A., Bischoff F. R., Marshallsay C., Lührmann R., Ponstingl H., Fanning E. (1996) J. Cell Sci. 109,1449–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwoebel E. D., Talcott B., Cushman I., Moore M. S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273,35170–35175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayliss R., Ribbeck K., Akin D., Kent H. M., Feldherr C. M., Görlich D., Stewart M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293,579–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaseen N. R., Blobel G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274,26493–26502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villa Braslavsky C. I., Nowak C., Görlich D., Wittinghofer A., Kuhlmann J. (2000) Biochemistry 39,11629–11639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meier I., Brkljacic J. (2009) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12,87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tachibana T., Imamoto N., Seino H., Nishimoto T., Yoneda Y. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269,24542–24545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen T., Muratore T. L., Schaner-Tooley C. E., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Macara I. G. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9,596–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohba T., Seki T., Azuma Y., Nishimoto T. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271,14665–14667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]