Activation of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) in response to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) leads to pathophysiology of cells/tissues by overmodulation of gene transcription. PRDX6 plays a rheostat role in regulating gene transcription by controlling cellular ROS in maintaining homeostasis; thus, fine tuning of Prdx6 expression is required to optimize ROS levels. Using Prdx6- and Smad3-depleted cells, we show that Prdx6−/− cells bear active NF-κB and Smad3, and repression of Prdx6 transcription in redox-active cells (Prdx6−/−) is due to ROS-induced dominant Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling. The Prdx6 promoter (−1139 bp) containing repressive Smad3-binding elements and NF-κB sites showed reduced promoter activity in Prdx6−/− cells, and the activity was restored in Smad3−/− cells. Mutation of repressive Smad3-binding elements eliminated the repression of the Prdx6 promoter. Revival of promoter activity by application of TGFβ1 antibody to Prdx6−/− and Smad3−/− cells with increased Prdx6 mRNA and protein conferred resistance to TGFβ- and H2O2-induced insult, demonstrating that repression of Prdx6 transcription is Smad3-dependent. Promoter activity in Smad3−/− or Prdx6−/− cells was moderately increased by disruption of NF-κB sites, suggesting the role of NF-κB in tuning of Prdx6 expression. Findings revealed a mechanism of repression and regulation of PRDX6 expression in cells facing stress or aging and provided clues for antioxidant(s)-based new approaches in preventing ROS-driven deleterious signaling.

PRDX6 (peroxiredoxin 6) is a member of an emerging peroxiredoxin family that has GSH peroxidase as well as acidic Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 activities (1–7). The peroxiredoxins function in concert to detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 and play a cytoprotective role by removing ROS and by limiting ROS levels regulating cell survival signaling (1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9–11). The unique ability to regulate signaling and to maintain phospholipid turnover distinguishes PRDX6 from the other five peroxiredoxins (PRDX1 to -5). This molecule is widely expressed, occurring in high levels in the liver, lung, eye lens, and keratinocytes (1, 2, 10, 12–18), whereas reduced expression of PRDX6 can lead to cell death and tissue degeneration (10, 11, 15, 19–22). PRDX6 has been implicated in maintenance of blood vessel integrity in wounded skin (23, 24) and in development and progression of several diseases, including oxidative-induced cataractogenesis (25), psoriasis (12, 26) atherosclerosis (22), and Parkinsonian dementia (27). Accumulating evidence indicates that expression levels of PRDX6 contribute to pathophysiology of cells and tissues. Several studies have reported decreases in antioxidant levels and increases in ROS levels, leading to a decline in a number of physiological functions because of overmodulation of ROS-mediated gene expression and activation of such factors as TGFβ and NF-κB, hallmarks of the aging process and age-associated degenerative diseases (28–30). However, given the role of ROS as a mediator of normal or redox signaling, we believe that optimal regulation of Prdx6 expression may require fine tuning to avoid overshooting the desired beneficial effects to the point of perturbing the delicate redox balance essential to maintenance of normal cellular function. Recently, using targeted inactivation of the Prdx6 gene, we reported activation and expression of TGFβ and TGFβ-mediated suppression of Prdx6 mRNA and protein (1, 4, 5, 31), suggesting that this molecule may have a role in repression of Prdx6 transcription. Quantification by staining with H2DCF-DA established a higher prevalence of ROS in these cells. Also, the activation of TGFβ in Prdx6-deficient cells was associated with ROS and inhibited by PRDX6 overexpression or MnTBAP, a superoxide dismutase mimetic and a known ROS inhibitor, in view of our earlier finding(s) that Prdx6-depleted cells bear higher levels of ROS and are thereby more susceptible to oxidative stress and apoptotic cell death (1–5, 7–11).

TGFβ, a multipotent growth factor, is involved in various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, migration, and extracellular matrix formation (32–34). Activation of TGFβ has also been implicated in multiple fibrotic diseases, including those of the eye, such as glaucoma and anterior subcapsular cataract (35–38). Moreover, several mechanisms of TGFβ activation are known (39), and a diverse group of activators, including trauma, proteases, TSP-1, integrin, low pH, and ROS, can activate TGFβ1 (20, 40, 41). Using targeted inactivation of the Prdx6 gene, we have also shown that ROS levels are elevated in Prdx6−/− cells, and this is a cause of TGFβ activation. TGFβ initiates its signaling by interaction with the TGFβ type II receptor that proceeds to phosphorylation of type I, forming an activated complex and leading to the activation of TGFβRI kinase activity (42), which transmits the signal into cells through Smads-mediated or alternative signaling pathways (43). Growing evidence suggests that the TGFβ-mediated activation of Smads regulates downstream signaling by modulating the transcriptional activity, either by functional cooperation with transcriptional proteins, direct binding to DNA, or direct interaction with DNA-bound transcription factors (18, 44). The ability of TGFβ to induce or suppress the expression of several genes, including PAI-1, clusterin, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (JE/MCP-1), and type I collagen, depends on specific DNA-binding sites in the promoter regions of these genes (45–48). Although the molecular mechanism of TGFβ-induced activation of the gene promoter has been established, less is known about the way in which TGFβ signaling exerts its effect in repression of gene transcription. Earlier studies have documented that TGFβ plays a regulatory role in the modulation of the transcription of various genes via TGFβ-inhibitory elements (TIEs; nnnTTGGnnn) (49–52). Kerr et al. (50) have shown that a 10-base pair element in the transin promoter is required for the TGFβ1-inhibitory effects. Recently, Frederick et al. (47) discovered a potential consensus repressive Smad3-binding element (RSBE) in the c-myc promoter sequence overlapping the c-myc TIE (5′-TTGGCGGGAA-3′), a site that is notably different from a consensus Smad-binding element (SBE; 5′-GTCT-3′) and responsible for binding of Smad3 and repression of the c-myc gene.

Moreover, NF-κB, a redox-active transcriptional protein, is a ubiquitous, multisubunit transcription factor whose activation plays an important role in regulation of genes that function in inflammation, cell proliferation, cell survival, and apoptosis (53). Such factors are considered to be key regulators of cellular stress response. NF-κB is induced and activated by different stimuli and conditions, such as pathology, oxidative stress, hypoxia, inflammatory mediators, and the internal cellular microenvironment (54, 55). In unstimulated resting cells, NF-κB is inactive; it is induced by internal or external stresses (54, 56). NF-κB is a multisubunit transcription factor, and its activity is regulated by interaction with specific inhibitory proteins, Iκ-Bs. Upon cell stimulation, IκBs become phosphorylated and subsequently ubiquitinylated. Released NF-κB translocates into the nucleus and binds to the target sequences and initiates transcription of “defense genes” involved in inflammatory responses and pathophysiology of cells and tissues. This molecule may sense ROS-induced stress, and its function may be altered in relation to the levels of ROS in cellular microenvironment. Earlier study has shown that proapoptotic and antiapoptotic roles of NF-κB depend on cell type and cell environment (57). Recently, two putative NF-κB sites have been predicted in the Prdx6 gene promoter (31) and have been thought to be involved in Prdx6 regulation. However, based on current study using transactivation and mutational analysis of the Prdx6 promoter coupled with Smad3- and Prdx6-deficient lens cells as models as well as biochemical assays, we think the control of NF-κB signaling in tuning of Prdx6 gene expression is attenuated in Prdx6-depleted cells (redox state) or aging cells, due to activation of Smad3-mediated TGFβ-induced repressive signaling. The process attenuates Nrf2 activation of Prdx6 gene transcription (58) as well. Thus, autoregulation of Prdx6 disrupted in response to internal or external stressors. However, Web-based computer analysis (MatInspector; Genomatix) of the 5′-flanking region of the Prdx6 promoter revealed that it has various putative regulatory elements as follows: SP1, E2F-Myc, Nrf2, HIF1α, PBX1-MEIS1, EREs, GRE, GATA-1, HSF1, LEDGF, c-ETS-1, v-Myb, Oct1/Oct2, etc., including two sites of the NF-κB at −644 to −635 and −948 to −939 as well as two sites of RSBE (TIE) (45, 47) at −379 to −367 and −482 to −471 from the transcription start site.

In the present investigation, using Prdx6−/−- and Smad3−/−-deficient lens epithelial cells (LECs) and a variety of biochemical assays, we examined the regulation of Prdx6 expression by ROS-driven Smad3-mediated TGFβ1-induced adverse signaling in cells facing oxidative stress, and we have shown this as a model to study the ROS-induced TGFβ1-mediated adverse signaling in LECs that may lead to degenerative disorders, including cataractogenesis. We identified two novel NF-κB-binding elements and two RSBE elements in the Prdx6 promoter and demonstrated how Smad3, a protein known to be involved in regulation of TGFβ target genes, may attenuate Prdx6 gene transcription and thereby negatively regulate survival signaling in cells in the redox state. Given the role of ROS as a mediator of normal signaling, we propose a rheostat role for NF-κB in determining optimum regulation of Prdx6 expression to maintain physiological ROS levels. The studies reported here provide insight regarding how the gene network is changed during aging or oxidative stress and should provide clues potentially useful in the development of a transcription- or antioxidant-based therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation and Validation of LECs Isolated from the Lenses of Prdx6−/−, Prdx6+/+, Smad3−/−, and Smad3+/+ Mice

Lens epithelial cell lines from lenses isolated from Prdx6-targeted mutants (Prdx6−/−) and wild-type (Prdx6+/+) mice were generated and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum as described earlier (1). Prdx6−/−129/Sv mice were generated at Harvard Medical School under the supervision of Dr. David R. Beier (59). Prdx6−/− mutant mice of pure 129 background were used during the present study. Wild-type 129/Sv inbred mice of the same sex and age were used as control (Prdx6+/+). All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal house at Harvard Medical School. Smad3−/− knock-out mice were obtained from Dr. Beebe (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). These mice have been generated by Deng and co-workers (34). The generation, characterization, and mating of mutant mice and the progeny of Smad3-targeted mice have been described in detail (34). The resulting progeny were screened by PCR to identify Smad3−/− and wild-type mice. As mentioned above, lens epithelial cells were isolated from lenses isolated from the mice of identical age, and Western analysis was carried out to confirm the presence of αA-crystallin, a specific marker of LECs, in both Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ LECs (see Fig. 9B). LECs (passages 3–5) were used for the experiments.

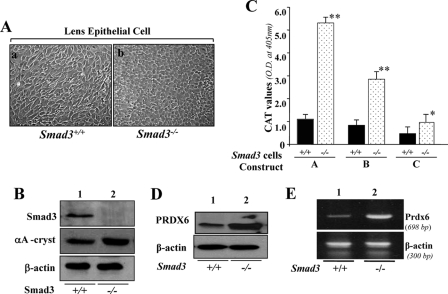

FIGURE 9.

A, photomicrograph of Smad3+/+ and Smad3−/− lens epithelial cells cultured in vitro and validation of their integrity. Smad3+/+ (a) and Smad3−/− (b) LECs were isolated from their corresponding mouse lenses and maintained in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum (1). B, integrity of these cells was validated using αA-crystallin antibody (middle), a specific marker of LECs, and Smad3-specific antibody (top) using Western analysis. Bottom, β-actin, an internal control. C–E, unlike Prdx6−/− cells, Smad3−/− cells displayed enhanced Prdx6 promoter activity and increased expression of PRDX6 protein. C, a representative of transactivation assay experiments showing CAT activities in Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ cells cultured in serum-depleted media. Cells were transfected with equal amounts of Prdx6 promoter linked to CAT. CAT activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” CAT activity of deletion mutant constructs in Smad3−/− cells (dotted bar) and Smad3+/+ cells (black bars) was monitored. Western analysis (D) and RT-PCR (E) showing expression of PRDX6 protein and mRNA in Smad3−/− cells, respectively.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer, as described previously (1, 4). Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded onto a 10% SDS-gel, blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and immunostained with primary antibodies at the appropriate dilutions (αA-crystallin antibody (a kind gift from Dr. Jack Liang, Harvard Medical School); PRDX6 monoclonal antibody (Lab Frontier, Seoul, Korea); TGFβ1, pIκBα, IκBα, Smad3, and RelA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); pSmad3 antibody (BIOSOURCE International Inc.). Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1500 dilution). Specific protein bands were visualized by incubating the membrane with luminal reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and exposing to film (X-Omat; Eastman Kodak Co.) and recorded with a FUJIFILM-LAS-4000 luminescent image analyzer (FUJIFILM Medical Systems Inc.). To ascertain comparative expression and equal loading of the protein samples, the membrane stained earlier was stripped and reprobed with actin antibody (Sigma).

Construction of Prdx6 Promoter-Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase (CAT) Reporter Vector

The 5′-flanking region (−1139 to +109 bp) (Fig. 1, Construct A) was isolated from mouse genomic DNA and sequenced. A construct of −1139 bp was prepared by ligating it to basic pCAT vector (Promega) using the SacI and XhoI sites. Similarly, constructs of deletion mutants of different sizes (Fig. 2, Constructs B and C) of the Prdx6 promoter with appropriate sense primers bearing SacI and reverse primer with XhoI were made and used in the present study. The plasmid was amplified and used for the CAT assay. Primers were as follows: Construct Afor, 5′-CTGAGAGCTCCTGCCATGTTC-3′; Construct Bfor, 5′-CTTCCTCTGGAGCTCAGAATTTAC-3′; Construct Cfor, 5′-CACAGAGCTCGTTCTTGCCACATC-3′; Constructs A, B, and Crev, 5′-CAGGAACTCGAGGAAGCGGAT-3′.

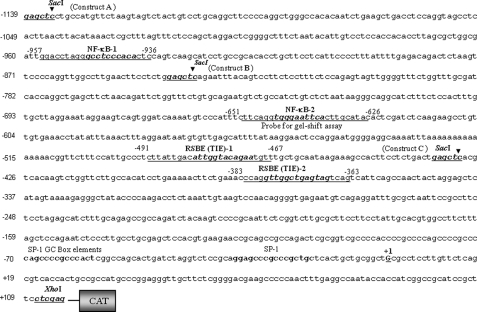

FIGURE 1.

5′-Proximal regulatory region of Prdx6 gene promoter linking to CAT. Nucleotide sequences spanning from −1139 to +109 were linked to CAT reporter vector. The consensus sequences for the predicted two NF-κB (NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2) and two RSBE/TIE binding sites are shown in boldface and italic type, respectively, and were mutated in experiments assessing the contribution of each site to promoter activity. Underlining indicates the position of oligonucleotides employed in gel shift and supershift assays. The transcription start site is indicated by +1, and SacI and XhoI restriction sites used for marking deletion mutants of Prdx6-CAT-constructs are shown in boldface type.

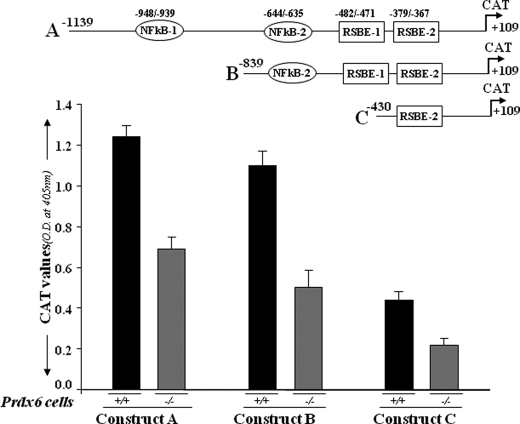

FIGURE 2.

Transcriptional repression of different deletion mutants of Prdx6 gene promoter linked to CAT in Prdx6+/+ and Prdx6−/− cells. The top drawing illustrates the putative transcription-binding elements in the Prdx6 promoter. Construct A consists of two NF-κB sites (NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2) and two repressive Smad3-binding elements (RSBE-1 and RSBE-2). Two deletion mutants were generated: Construct B with one NF-κB and two RSBE sites and Construct C with one RSBE site only. Cells were transiently transfected with Prdx6-CAT Construct A, B, or C. After 72 h, protein was extracted, and CAT activity was measured. The transfection efficiencies were normalized using a plasmid secreted alkaline phosphatase basic vector. The data represent the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), following the company's protocol. Briefly, amino acid exchanges (NF-κB-1 (negative strand) or NF-κB-2 (CC to AA or G to C) and RSBE/TIE-1 or -2 (GG to AA or T to A and G to C)) were generated by point mutations in the Prdx6-CAT constructs. The following complementary primers were used (changed nucleotides are in boldface type and underlined): NF-κB-Mut-1for, 5′-GATTGGACCTAGGGCCTCCCACACTCCAGTCAAG-3′; NF-κB-Mut-1Rev, 5′-CTTGACTGGAGTGTGGGAGGCCCTAGGTCCAATC-3′; NF-κB-Mut-2for, 5′-CATTTCTTCAGGTGGGAATTCACTGCATACAC-3′; NF-κB-Mut-2Rev, 5′-GTGTATGCAGTCAATTCGCACCTGAAGAAATG-3′; RSBE/TIE-1-MutFor, 5′-CCCTCTTATTGACATTGGTACAGAATGTTTGCTGC-3′; RSBE/TIE-1-MutRev, 5′-GCAGCAAACATTCTGTACCAATGTCAATAAGAGGG-3′; RSBE/TIE-2-MutFor, 5′-CTTCTGAAACCCAGGTTGGCTGAGTAGTCAGTC-3′; RSBE.TIE-2-MutRev, 5′-GACTGACTACTCAGCCAACCTGGGTTTCAGAAG-3′.

Epicuran Coli XL1-Blue super-competent cells (Stratagene) were transformed with resultant plasmid, and clones were grown on Luria-Bertani/Amp Petri dishes. The plasmid was amplified, and the mutation was confirmed by sequencing.

Transfection and CAT Assay

The CAT assay was performed using a CAT-ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science). Prdx6−/− or Smad3−/− LECs as well as their respective wild-type LECs were transfected/co-transfected using Superfectamine with Prdx6-CAT reporter constructs and 1 μg of SEAP vector, as reported earlier (1). After 72 h of incubation, cells were harvested, extracts were prepared, and protein was normalized. CAT-ELISA was performed to monitor CAT activity following the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microtiter plate ELISA reader. Transactivation activities were adjusted for transfection efficiencies using the secreted alkaline phosphatase value (1). In a parallel experiment, NF-κB regulation of the Prdx6 gene was validated by cotransfecting cells with a dominant-negative mutant of IκBα (a kind gift of Dr. Rakesh K. Singh, University of Nebraska medical Center Omaha, NE). ROS is an inducer of NF-κB activation. To determine whether NF-κB activation is associated with elevated ROS expression cells, Prdx6−/− cells were transfected with Prdx6 promoters (Constructs A, B, and C) and treated with variable concentrations of antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine (NAC).

Determination of NF-κB Activation Using HIV-1LTR-CAT

HIV-1LTR-CAT constructs (a kind gift from Dr. Carole Kretz-Remy) were used to transfect cells. The HIV-1 promoter contains binding sites for many transcriptional factors, including NF-κB, and can be up-regulated 12–150-fold following various stresses, including oxidative stress (60). We used pLTR-CATWT, pLTR-CAT EcoRI (where two κB consensus sequences are mutated to perfect palindromic κB sites), and pLTR-CAT PstI (where NF-κB sites are disrupted) to monitor that activation of NF-κB. We transfected these constructs to the cells, and after 72 h, CAT-ELISA was performed, as described earlier (1, 2, 4, 61).

Expression and Purification of TAT-HA-PRDX6 Fusion Protein

A full-length cDNA of PRDX6 was isolated from a human lens epithelial cell cDNA library and cloned into TAT-HA-PRDX6 prokaryotic expression vector, and recombinant protein was purified using an Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-Sepharose column, as described earlier (1, 2). Briefly, the host Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was transformed with pTAT-HA-PRDX6, and the cells were harvested in binding buffer and sonicated. After centrifugation, supernatant containing TAT-HA-PRDX6 was immediately loaded onto a 2.5-ml column. After washing, the fusion protein was eluted with an elution buffer and dialyzed. The purified protein can be either used directly for protein transduction or aliquoted and stored frozen in 10% glycerol at −80 °C for further use.

DNA and Protein Interaction Assays

Gel shift or supershift assays were carried out using nuclear extracts (1, 2, 4) isolated from Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ or Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ LECs to determine DNA binding activity of NF-κB or Smad3 to their respective elements present in the Prdx6 promoter. Oligonucleotides consisting of putative NF-κB or repressive Smad3-binding elements or respective mutant probes were commercially synthesized (Invitrogen), annealed, and end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Inc.). The binding reaction was performed in 20 μl of binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 75 mm KCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.025% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 μg of poly(dI/dC). Five fmol of the end-labeled probe was incubated on ice for 30 min with 5 μg of nuclear extract. The samples were then loaded on 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer for 2 h at 10 V/cm. The gel was dried and autoradiographed. For the supershift assay, 1 μl of antibody was added to the binding reaction, and this was further incubated for 30 min.

Cell Survival Assay (MTS Assay)

A colorimetric MTS assay (Promega) was performed as described earlier (1–6, 61). This assay of cellular proliferation uses 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2 to 4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium salt (MTS; Promega, Madison, MI). Upon being added to medium containing viable cells, MTS is reduced to a water-soluble formazan salt. The A490 nm value was measured after 4 h with an ELISA reader.

Assay for Intracellular Redox State

ROS levels of Prdx6+/+ and Prdx6−/− cells as well as the effect of NAC on ROS levels were measured using the fluorescent dye, H2-DCF-DA, a nonpolar compound that is converted into a polar derivative (dichlorofluorescein) by cellular esterases following incorporation into cells. For the assay, the medium was replaced with Hanks' solution containing 5–10 μm H2-DCF-DA. Following 30 min of incubation at room temperature, intracellular fluorescence was detected with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm using Spectra Max Gemini EM (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS

NF-κB and RSBEs Are Present in the Prdx6 Gene Promoter

Previously we reported a suppression in PRDX6 protein and mRNA level in lens epithelial cells (LECs) following the treatment of TGFβ1 or LECs facing oxidative stress (1, 4, 5). In addition, several laboratories as well as our own have observed modulation of PRDX6 expression in a variety of cells exposed to a variety of reagents/factors, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, TGFβ, dexamethasone, serum withdrawal, and H2O2. The changes have depended upon time and concentration of factors (1–7). However, the underlying mechanism involved in regulation of Prdx6 in the redox environment is not clear. Because PRDX6 is a protective protein and plays a role in signaling by limiting cellular ROS levels, the regulation of Prdx6/PRDX6 gene transcription may need fine tuning to control the expression of the protein. We predicted the presence of TGFβ-mediated repression of Prdx6 gene transcription due to an abundance of activated TGFβ in redox cellular microenvironment. To ascertain how Prdx6 expression is regulated, we analyzed redox-active putative transcription factor binding sites in the Prdx6 gene promoter. A Web-based computer analysis (MatInspector; Genomatix) of 5′-flanking region spanning from −1139 to +109 bp, disclosed the presence of two putative RSBE (TIE)-like sites at −379 to −367 and −482 to −471 (RSBE/TIE; 5′-nnTTGGCGGnnn-3′) (45, 47, 62) and two putative NF-κB sites at −644 to −635 and −948 to −939 (Fig. 1). NF-κB is a well known redox-active transcriptional factor, which binds to its specific binding sites. Based on computer prediction of SRBE and NF-κB sites of the Prdx6 gene, as a first step, we engineered deletion mutant constructs linked to CAT, as described under “Experimental Procedures” and in the legends to Figs. 1 and 2. Constructs were as follows: A-CAT with both SRBE/TIE and both NF-κB sites, B-CAT with one NF-κB and two RSBE sites, and C-CAT with one RSBE site only (47). We used oligonucleotides derived from the Prdx6 promoter containing NF-κB and RSBE binding sites in gel shift and supershift assays (as defined in Fig. 1) and CAT-linked wild type and mutant constructs to identify the functionality and contribution of these sites in regulation of the Prdx6 gene promoter in normal conditions as well as cells in the redox state.

Promoter Activity of Prdx6 Is Repressed in Prdx6−/−-depleted Cells

In earlier studies (1, 4), we demonstrated that LECs lacking Prdx6 display phenotypic changes and undergo spontaneous apoptosis, and these adverse changes are associated with higher expression and activation of TGFβ1 by ROS in Prdx6−/−-deficient LECs. Therefore, to identify any contribution of RSBEs (TGFβ1-mediated adverse signaling during oxidative stress) in the repression of the Prdx6 gene, we decided to utilize Prdx6−/− LECs (redox state) as a model for transactivation studies. After the cells were transiently transfected with the Prdx6 promoter containing the putative RSBE (TIE) and NF-κB element or deletion mutant constructs, CAT-ELISA was performed. As expected, a significant suppression of Prdx6 promoter activity was observed in all three constructs (Fig. 2, black bar versus gray bar), and CAT activity was decreased significantly in Construct B, consisting of two RSBE (TIE)-like elements. A pattern of progressive decline in promoter activity of deletion mutants (Constructs A–C) was observed in wild type cells, and that may be associated with the length of promoter lacking regulatory responsive sequences. However, a significant reduction in Prdx6 promoter activity in Prdx6−/− cells clearly suggests the repressive action of TGFβ1 signaling. On the basis of this finding, we hypothesize that since Prdx6−/− cells are under continuous oxidative stress and release bioactive TGF-β, this repression may be associated with Smad3-mediated TGF-β signaling (1, 4, 40, 41) due to overstimulation and activation of Smad3. Overexpression and activation of Smad3 has been reported to be one cause of gene repression (47).

TGFβ1 Treatment Repressed Prdx6 Promoter Activity and Is Restored by Neutralizing Antibody in Prdx6−/− Cells

To examine whether inhibition of promoter activity of Prdx6 is mediated by TGFβ1, we designed an experiment using Constructs B (both RSBE sites) and C (only one RSBE site) described above. In this experiment, wild type (Prdx6+/+) cells were treated with TGFβ1 (Fig. 3A), and Prdx6−/− cells were treated with TGFβ1-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 3B), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were transfected with Prdx6-CAT constructs and treated with TGFβ1 at 2 ng/ml and/or TGFβ1-neutralizing antibody (5–10 μg/ml). TGFβ1-mediated repression of Prdx6 promoter activity was observed in Prdx6+/+ cells treated with TGFβ1 (black bar versus striped bar), and the repression of promoter activity was similar to that in Prdx6−/− cells (black bar versus striped bar versus dotted bar), demonstrating that negative regulation of Prdx6 promoter activity is due to prevalence of TGFβ1-mediated signaling in Prdx6−/− (redox state). In a parallel experiment, TGFβ1-neutralized antibody (5–10 μg/ml) was added for 3 days. A restoration of the Prdx6 promoter activity (Fig. 3B, striped bar versus dotted bar) further provided evidence of the involvement of TGFβ1-mediated signaling in attenuating Prdx6 gene transcription.

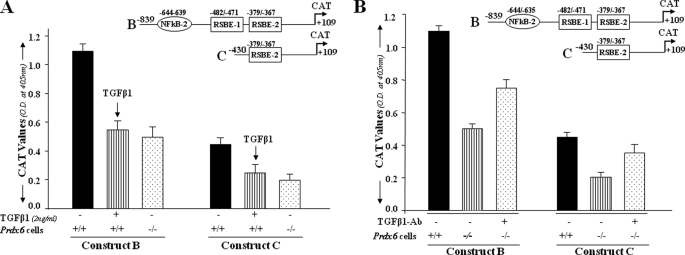

FIGURE 3.

A, TGFβ1-induced repression of Prdx6 gene transcription in Prdx6+/+ cells as seen in Prdx6−/−. The cells were transiently transfected with Prdx6-CAT Construct B or C containing an RSBE site(s) as in Fig. 2. Prdx6+/+ cells (striped bars) were treated with TGFβ1 at a concentration of 2 ng/ml for 3 days, and Prdx6−/− cells and untreated Prdx6+/+ cells served as control. CAT activity of these constructs in Prdx6−/− or TGFβ1-treated or -untreated Prdx6+/+ cells was compared. Results are mean ± S.D. from three experiments. B, TGFβ-neutralizing antibody reduced the repression of Prdx6 transcription in Prdx6−/− cells. Cells were transiently transfected with either Construct B or C, and TGFβ-neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems) was added at a concentration of 5 μg/ml for 3 days followed by CAT activity determination. Striped bars indicate untreated control, and dotted bars show cells treated with TGFβ1-neutralizing antibody.

Smad3 in Nuclear Extracts of Prdx6−/− Cells Specifically and Directly Binds to RSBE in the Prdx6 Promoter

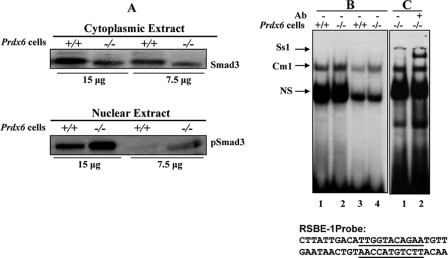

Since TGFβ initiates its signal through receptor binding, this activated receptor is then able to phosphorylate its intracellular effector substrates, which include the highly homologous Smad2 and -3 (47, 63–66). These cytoplasmically retained Smads form heteromeric complexes, which then translocate to the nucleus (67, 68). Based on research by Frederick et al. (47) showing TGFβ-induced Smad3-mediated repression of the c-myc gene by the direct interaction of RSBE (which is distinct from a consensus SBE) and Smad3, we conducted Western analysis to determine whether Smad3 is activated in Prdx6−/− cells. Cytoplasmic extract isolated from Prdx6−/− showed a diminished level of Smad3 protein (Fig. 4A, top), suggesting the possibility of its translocalization to the nucleus. Western analysis of nuclear extract isolated from the same cells with pSmad3 antibody (Smad3 phospho-specific Ab) revealed, indeed, that activated Smad3 is translocalized in the nucleus of Prdx6−/− cells. Since TGF-β is in the bioactive form in Prdx6−/−-depleted cells (1), we predicted that repressive Smad3-binding elements present in the Prdx6 promoter were responsible for the repression of the Prdx6 promoter. To determine whether Smad3 in the nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells binds to their respective responsive sites in the Prdx6 promoter, we performed a gel shift assay using oligonucleotides derived from the Prdx6 promoter containing an RSBE site (−491 to 467 or 383 to −363) (Fig. 4B). Nuclear extract from these cells bound to DNA probe and formed a shifted band designated as Cm1 with higher intensity than nuclear extract isolated from Prdx6+/+ cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–4). Lanes 3 and 4 represent double dilution of nuclear extract to show the comparative binding. A probable reason for residual activation of Smad3 in Prdx6+/+ was that the cells were cultured in serum-depleted medium to maintain their bona fide character, since lens cells are devoid of blood circulation. The Cm1 complex that appeared in the lanes was supershifted and formed a band after the addition of Smad3-specific antibody (sc-6202; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Ss1 (Fig. 4C, lane 2) and demonstrated the specificity of Smad3 and DNA interactions. A band (Ns) appeared in all lanes with approximately the same intensity, suggesting that it is nonspecific. This band was used to show equal loading, because it remained unaltered, demonstrating that not all nuclear proteins in Prdx6−/− cells changed their property.

FIGURE 4.

Expression levels of Smad3 and pSmad3 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells. A, cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared and resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western analysis for Smad3 and pSmad3 (compare lanes +/+ versus lanes −/−). B and C, representative gel shift and supershift assays showing binding of Smad3 present in the nuclear extracts of Prdx6−/− to RSBE-1 probe derived from the Prdx6 promoter. Nuclear extract (5 or 2 μg) from Prdx6−/− (B, lanes 2 and 4) or Prdx6+/+ (lanes 1 and 3) cells was incubated with radiolabeled probe having an SRBE-binding element (RSBE-1). Supershift assay was performed (C, lane 2) following incubation with Smad3-specific antibody (sc-6202; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Similar results were obtained with SRBE-2 (data not shown). NS denotes nonspecific binding and demonstrates equal loading of samples.

Mutation in RSBE Sites Present in the Prdx6 Promoter Abrogates Repression of Prdx6 Transcription in Prdx6−/− Cells and Is Unresponsive to TGFβ1 Treatment

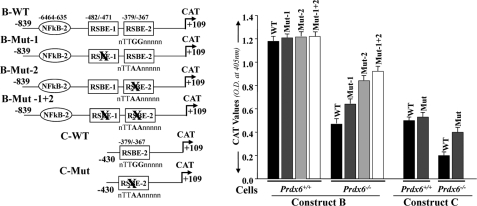

We next evaluated the functionality of RSBE sites in the Prdx6 promoter by mutating these sites (RSBE/TIE-1 (nnTTGGnnnnn to nnTTAAnnnnn) and/or RSBE/TIE-2 (nnTTGGnnnnn to nnTACGnnnnn)) and conducting the transactivation assay. We mutated RSBE/TIE binding sites in wild-type Constructs B and C and denoted them B-Mut-1, B-Mut-2, B-Mut-1 + 2, and C-Mut, respectively (Fig. 5, left). Cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding the CAT reporter under the control of wild-type or mutant Prdx6 promoter. As expected, the promoter activity of mutant promoter was increased in Prdx6−/− cells (Fig. 5, black bar versus gray, light gray, and open bars) when repressive Smad3-binding elements were disrupted (Construct B (Mut-1, Mut-2, and Mut-1 + 2) and Construct C (Mut)), suggesting that RSBE sites in the Prdx6 promoter were functional and were required for physical and functional interaction of Smad3 to repress Prdx6 promoter activity.

FIGURE 5.

Point mutation at RSBE site(s) of the Prdx6 promoter abrogated repression of Prdx6 transcription in Prdx6−/− cells. Left, schematic illustration of wild type (Constructs B and C having RSBE/TIE) and mutated (RSBE/TIE disrupted using site-directed mutagenesis) Prdx6 promoter constructs. Right, CAT activity of engineered wild type (black bars) and mutant (gray, light gray, and open bars) promoter constructs of Prdx6 was assessed for their transcriptional activity in Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells. All data were presented as the mean ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments.

We next tested the effect of TGFβ1 on Prdx6 promoter activity. Cells transfected with either wild type or mutant promoter (disrupted RSBE site) were treated with TGFβ1 for 48 h, and promoter activity was evaluated. Results disclosed that the treatment did not affect the mutant promoter activity, in contrast to wild type promoters (data not shown). We concluded that the RSBE sites in the promoter were functional, and repression of the Prdx6 promoter was associated with Smad3-mediated TGFβ1 signaling in cells facing oxidative stress. Thus, we found two active sites of RSBE that were involved in suppression of Prdx6 genes, and results unveil the TGF β1 suppression of Prdx6 mRNA and protein in LECs (5, 31).

NF-κB Is Present in Activated Form in Prdx6−/− Cells, a Model for Cells Facing Oxidative Stress

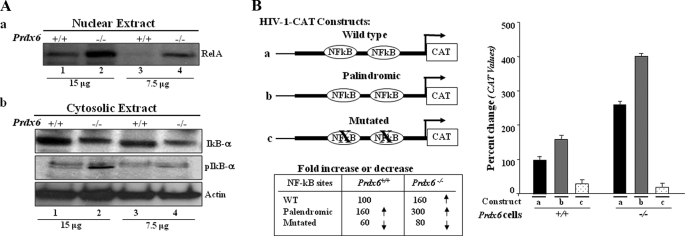

In the transactivation experiments described above, we observed a progressive decline in the pattern of Prdx6 promoter activity. Notably, the decline was related to deletion mutant promoter constructs lacking putative NF-κB sites. We predicted that the NF-κB site present in the promoter should be involved in regulating the Prdx6 gene. To test whether NF-κB is indeed present in the activated state in Prdx6−/− cells, we performed Western analysis with these redox-active cells to isolate nuclear and cytosolic extract and assess expression levels of important components of the NF-κB family. Western analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells revealed a diminished expression of RelA/p65 in Prdx6−/− cytoplasmic extract (data not shown), in contrast to nuclear extracts that had a higher level of RelA/p65, suggesting that NF-κB is activated and translocated into the nucleus (Fig. 6A, a, lanes 2 and 4). Under normal conditions, NF-κB (RelA/p65) resides in the cytoplasm through its interaction with IκB-α, IκB-β, or IκB-ϵ. Activation of NF-κB involves phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteolysis of IκB-α. Liberated NF-κB (p65 and p50) migrates to the nucleus, where it stimulates the transcription of target genes (69). Therefore, to test the degradation and phosphorylation of IκB-α in Prdx6−/− cells, the membrane stained earlier with RelA/65 antibody (cytoplasmic extract) was stripped and reprobed with IκBα or pIκBα antibodies. Results revealed the degradation as well as phosphorylation of IκB-α in Prdx6−/− cells (Fig. 6A, bottom, cytosolic extract, lanes 2 and 4) in contrast to Prdx6+/+ cells (lanes 1 and 3).

FIGURE 6.

A, presence of RelA/p65 in the nuclear extract and phosphorylated/degraded form of IκBα in the cytosolic extracts of Prdx6−/− cells. a, representative Western blot displaying predominant presence of NF-κB/p65 in nuclear extracts from Prdx6−/− cells. Nuclear extracts were isolated from Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells. Western analysis was conducted with anti-RelA/p65 (sc-7151; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using 15 and 7.5 μg of nuclear extract (a, lanes 1 and 2). b, cytoplasmic extracts were separated, and Western analysis was conducted using pIκBα (middle, lanes 2 and 4) or IκBα (top, lanes 2 and 4) in cytosolic extracts of Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells. B, transactivation of HIV-1LTR disclosed the presence of NF-κB signaling in Prdx6−/−-depleted cells. Relative CAT activity was measured in Prdx6−/− as well as in Prdx6+/+ cells using HIV-1LTR promoter constructs (left). Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells were transiently transfected with either wild type pLTR-CAT (a) or pLTR-CAT-EcoR1 (b; where NF-κB sites are palindromic) or pLTR-CAT-Pst1 (c; where NF-κB sites are mutated). Promoter activity was monitored using CAT-ELISA.

Next, to learn whether the activation of the NF-κB signaling in Prdx6−/− is functional, we performed transactivation experiments utilizing pHIV-1 CAT constructs (a kind gift of Kretz-Remy); pLTR-CAT construct (wild type), which consists of binding sites for NF-κB (Fig. 6B, a); pLTR-CAT-EcoR1 (Fig. 6B, b, where NF-κB sites are palindromic); and pLTR-CAT-Pst1 (Fig. 6B, c, where NF-κB sites are mutated), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The promoter activity of Constructs A and B was significantly increased in Prdx6−/− cells in comparison with Prdx6+/+. On the other hand, Construct C, where NF-κB sites were mutated, did not show significant activity in either type of cells, demonstrating the presence of active NF-κB signaling in Prdx6−/− cells.

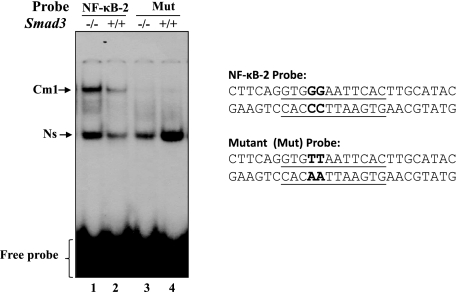

NF-κB in the Nuclear Extract of Prdx6−/− Cells Binds Directly to Its Responsive Elements in the Prdx6 Promoter and Regulates Its Transcription

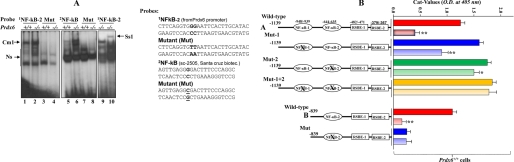

Changes in reduction-oxidation potential have been shown to influence the DNA binding activity of several transcription factors, such as oxyR, FOS/Jun, and NF-κB (19, 55, 56). To ascertain that NF-κB present in the nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells binds to its responsive sites in the Prdx6 promoter, a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide having NF-κB sites and its mutant were chemically synthesized. The gel shift assay was conducted with the nuclear extracts isolated from Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells using NF-κB −651CTTCAGGTGGGAATTCACTTGCATAC−626 and its mutant GG to AA binding sites following the method of Fatma et al. (1, 2) (Fig. 7A). As standard control, oligonucleotides containing the NF-κB site (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTCCAGGC-3′; catalog number sc2505; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and its mutant G to C were used to verify the results. Gel shift assay results demonstrated that nuclear extract isolated from Prdx6−/− cells was able to strongly bind to wild type 1NF-κB-2 probe and formed the Cm1 complex (Fig. 7A, left, lane 2, 1NF-κB-2). The nuclear extract did not bind to its mutants (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 and 4). However, there was mild interaction between nuclear extract derived from Prdx6+/+ cells as cells were cultured in serum-depleted medium. A similar experiment using standard 2NF-κB probe demonstrated active NF-κB in the nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells, which bound to its responsive elements (Fig. 7A, middle, lane 6), whereas mutant probe did not further validate the binding (Fig. 7A, middle, lanes 7 and 8). A supershift assay using antibody specific to RelA/p65 showed that the Cm1 band (Fig. 7A, right, lane 9) was supershifted to the Ss1 band after the addition of antibody (lane 10), suggesting the binding specificity of probe and NF-κB interactions. Similar results were obtained with NF-κB sites present in the Prdx6 promoter at positions −957 to −936 (Fig. 1). A band (Ns) appeared in all lanes with approximately the same intensity, signifying a nonspecific entity. This band confirmed equal loading as well, signifying that not all nuclear proteins in Prdx6−/− cells gained their DNA-binding property.

FIGURE 7.

A, nuclear extract from Prdx6−/− cells strongly bound to the NF-κB-responsive element present in the Prdx6 promoter. The 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes 1NF-κB-2 and 2NF-κB (as standard control) and their mutants were incubated with nuclear extract isolated from Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells, and a gel shift assay was performed. A supershift assay using Rel/P65 antibody following incubation with Prdx6−/− nuclear protein extract was carried out (Ss1; lane 10). B, point mutation at NF-κB sites identified by gel shift assay experiment (NF-κB-2) in the Prdx6 promoter Construct B abolished its transcriptional activity, whereas disruption of NF-κB-1 and/or NF-κB-2 in Construct A increased the promoter activity. Prdx6+/+ or Prdx6−/− cells were transiently transfected with equal amounts of wild type and their mutant promoter-driven CAT reporters (left panel, showing schematic representation of constructs in the experiment), and the CAT activity was measured. For Construct A, CAT activity of promoter mutated at NF-κB sites (Mut-1 (blue bar), Mut-2 (green bar), or Mut1 + Mut-2 (yellow bar)) was compared with the activity of wild type promoter constructs (WT (red bar)). In the same set of experiments, cells were also cotransfected with dominant-negative Iκ-Bα mutant (Iκ-BαAA; light red bar, light blue bar, and light yellow bar). For Construct B, cells were transfected either with wild-type NF-κB or its mutant, and CAT activity was monitored (B, WT versus Mut). In another set of experiments, cells were cotransfected with Iκ-BαAA (Construct B, light red and light blue bars). The CAT vector showed insignificant activity (data not shown).

NF-κB is a redox-active transcriptional protein and regulates many promoters containing variations in highly divergent consensus DNA-binding sequence. This variation may provide an opportunity for co-activators to find a place for functional interaction in modulating the target gene. Also, variation in consensus sequence in the NF-κB site may provide binding affinity that affects the transactivation potential of NF-κB (70, 71). NF-κB is highly activated in Prdx6−/− cells and binds to the Prdx6 promoter of its responsive element. Transactivation assays, as shown in Fig. 2, black bar, clearly demonstrated that Construct A with two sites and Construct B with only one site of NF-κB displayed significantly higher CAT activity than Construct C, which lacked the NF-κB site. However, from this experiment, it remained uncertain whether the higher activity of Constructs A and B resided exclusively in the NF-κB-responsive element. To test the functionality and contribution of each NF-κB binding site (NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2), in transcriptional regulation of the Prdx6 promoter, we altered 948GCCTCCCACA939 to AA (NF-κB-1) and 644TGGGAATTCA635 to C (NF-κB-2) and carried out a transactivation assay using wild type and mutant Prdx6 promoter constructs linked to CAT. Surprisingly, the promoter activity of mutated Construct A (Construct A; Mut-1 or Mut-2 or Mut-1 + Mut-2) was moderately increased (Fig. 7B, red bar versus blue, green, and yellow bars), and activity was NF-κB site-dependent. To validate the results, we used a dominant negative mutant NF-κB inhibitor (IκBαAA). Cotransfection of the dominant negative mutant attenuated NF-κB activity (Construct A and light red bars), confirming that both NF-κB sites present in the Prdx6 promoter are functional. Interestingly, the effect of dominant negative NF-κB inhibitor (Iκ-Bα AA) in attenuating Prdx6 mutant promoters (Construct A; Mut-1 and Mut-2) was significant but not as dramatic as was observed in the wild-type promoter. However, each of the two sites of NF-κB responded differently (Construct A; Mut-1 (blue and light blue bars) and Mut-2 (green and light green bars)). The Prdx6 promoter containing both disrupted NF-κB sites was unresponsive to negative dominant IκBα, further (Construct A; Mut-1 + 2; yellow and light yellow bars), suggesting that NF-κB is a regulator and involved in fine tuning of Prdx6 gene transcription and that it should be associated with the cellular requirement. Next, we intended to know the effect of a point mutation at the NF-κB site in Construct B (−839 to +109). The point mutation at the NF-κB-2 site (Construct B; Mut) dramatically abolished Prdx6 gene transcription and added further the weight to the possibility that the NF-κB-responsive elements present in the Prdx6 promoter were indeed functional and may act differently to regulate Prdx6 expression. Interestingly, similar results have been reported by Gallagher and Phelan (31), where they have suggested the repressive role of NF-κB in Prdx6 transcription. We found similar results, an increase of Prdx6 promoter activity when cells were treated with SN50, an inhibitor of NF-κB (data not shown). However, based on our results, we propose a regulatory role of NF-κB in Prdx6 gene transcription, where NF-κB controls Prdx6 expression, depending on cellular requirement. Similar patterns of transactivity of these constructs were noted in Prdx6−/− cells, but activity was significantly less due to the prevalence of Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling (data not shown). Moreover, it appears that the NF-κB-1 site functions differently from NF-κB-2 sites. This differential activity of NF-κB for different sites may be associated with regulatory specificity (due to variations in sequences) that may offer and ascertain which cofactors interact with the site (72). Collectively, results demonstrate that NF-κB sites present in the Prdx6 promoter are responsible for Prdx6 expression and thereby provide fine tuning for Prdx6 expression needed to maintain cellular homeostasis.

Delivery of PRDX6 Restores the Prdx6 Gene Promoter Activity in Prdx6−/− Cells by Attenuating Smad3-mediated TGFβ1 Signaling

NF-κB is known to have diverse functions in conditions ranging from cell death to cell survival; it achieves these functions by regulating apoptotic and antiapoptotic genes. Proapoptotic and antiapoptotic roles of NF-κB depend upon cell types and cell environment (57). However, we believe that NF-κB regulation of survival genes may be attenuated due to dominant repressive signaling present in the cellular microenvironment during oxidative stress or in aging cells that may turn NF-κBs-mediated prosurvival signaling to death signaling. Figs. 2 and 5 demonstrate that repression of Prdx6 promoter activity could be reduced and attenuated activity could be restored by adding TGFβ1-neutralizing antibody or by disrupting the RSBE site in the Prdx6 promoter, suggesting the existence of TGFβ1-mediated repression of Prdx6/PRDX6 expression. In an earlier study, we found that Prdx6/PRDX6 expression was suppressed by activation of TGFβ1 in Prdx6−/− cells or the addition of TGFβ1 in cultured cells (1, 4, 5). That finding supports our hypothesis that TGFβ1 mediates repression of NF-κB-activation of Prdx6 gene transcription during oxidative stress. Since Prdx6−/− LECs are under continuous oxidative stress, we predicted that the addition of PRDX6 might restore NF-κB activation of Prdx6 gene transcription by limiting ROS expression and thereby halting the TGFβ1-mediated adverse signaling in these cells caused by ROS-driven overshooting or perturbing the delicate redox balance. We reconfirmed our earlier report (1) on whether Prdx6−/− cells are under oxidative stress. To this end, we quantified intracellular levels of ROS using H2-DCF-DA. Results established that Prdx6−/− cells harbor higher levels of ROS, and NAC treatment reduced the expression levels ROS in these cells (Fig. 8C). However, in the present study, the promoter activity of Prdx6 was repressed in Prdx6−/− cells while NF-κB was in the activated form (Figs. 2–5), and this happened as activated Smad3 in nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells bound to RSBE in the Prdx6 promoter (Fig. 4). Because PRDX6 is a protective protein and maintains cellular homeostasis by negatively regulating death signaling, we hypothesized that the addition of PRDX6 and/or NAC, an antioxidant to Prdx6−/− cells, might optimize the DNA activity of NF-κB and Smad3 and reverse repression of Prdx6. Prdx6−/− cells were treated either with TAT-HA-PRDX6 recombinant protein, which can efficiently internalize in cells in a dose-dependent fashion (4, 61, 73), or with NAC. Three days later, these cells were harvested, nuclear extract was isolated, and a gel shift assay was performed with RSBE/TIE-1 (Fig. 8A), NF-κB-2, or mutant (Fig. 8B) probe. The addition of TAT-HA-PRDX6 (4 μg/ml) significantly reduced Smad3 binding to SRBE/TIE (Fig. 8, lane 3) and NF-κB overactivation and its binding to probe in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 8B, lanes 2 (2 μg/ml) and 3 (4 μg/ml)), demonstrating the ability of PRDX6 to block Smad3-mediated signaling and normalize NF-κB activation and its binding in Prdx6−/− cells.

FIGURE 8.

A, PRDX6 delivery to Prdx6−/− cells restored the Prdx6 promoter activity by attenuating Smad3 binding to RSBE. Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells were cultured in the presence (4 μg/ml) or absence of PRDX6 (4). Nuclear extract was isolated and incubated with radiolabeled RSBE-1 probe, and a gel shift assay was performed. Binding affinity of nuclear extract from Prdx6−/− cells supplied with recombinant PRDX6 (lane 3, Cm1; see Figs. 1 and 4 for RSBE-1) was compared with nuclear extract of Prdx6−/− cells (lane 2) to radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe containing RSBE. B, gel shift assay showing binding of nuclear extract from Prdx6−/− cells to radiolabeled probe containing NF-κB binding site or its mutant probe (NF-κB-2; see Fig. 7); binding activity of nuclear extracts isolated from cells treated with PRDX6 (lanes 2 and 3) compared with that of cells where TAT-HA-PRDX6 was not added (lane 1). C, Prdx6−/− cells showing higher expression of ROS. An H2-DCF-DA assay was conducted to monitor the effect of NAC on levels of ROS (C, gray bars). D and E, cells were transiently transfected with different Prdx6-CAT constructs and were cultured with or without PRDX6 for 3 consecutive days (4 μg/ml) or treated with NAC (1 mm), an antioxidant. After 72 h, cells were harvested, and CAT activity was monitored (D, gray bars) or NAC (E, gray bars).

To test whether supplying PRDX6 to Prdx6−/− cells could restore repressed Prdx6 promoter activity, cells (wild type or Prdx6-depleted) were transiently transfected with different Prdx6-CAT constructs, A, B, or C, and were supplied either with TAT-HA-PRDX6 for 3 consecutive days (4 μg/ml) (Fig. 8D) or with NAC (1 mm), an antioxidant (Fig. 8E). CAT assay results revealed restoration of promoter activity in Prdx6−/− cells supplied with TAT-HA-PRDX6 protein (Fig. 8D, gray bars) as well as cells treated with NAC (Fig. 8E, gray bars) in comparison with untreated cells (Fig. 8, white bars). The results provided further evidence that ROS-driven TGFβ-mediated adverse signaling could be inhibited by maintaining PRDX6 expression during oxidative stress or by optimizing intracellular ROS levels. Prdx6-depleted cells lose their bona fide phenotypes and do not maintain homeostasis (1, 4). These findings indicate that TGFβ1-induced Smad3-mediated signaling is a plausible main culprit in repression of the Prdx6 gene in Prdx6−/− cells facing oxidative stress.

Smad3-dependent TGFβ1-mediated Repression of the Prdx6 Promoter Is Lost in Smad3−/−-deficient Cells

Our next experiments sought to determine whether Prdx6 promoter activity was restored in Smad3−/− cells, where TGFβ1-induced Smad3-mediated repressive signaling was inactive. The availability of targeted disruption of Smad3 in mice (46) was a powerful tool to confirm the functionality of Smad3-mediated repression of the Prdx6 gene promoter in cells facing oxidative stress. LECs from Smad3+/+ (wild type) and Smad3−/− (knock-out) mice were isolated and maintained in DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum, as described elsewhere (1) (Fig. 9A). Integrity of these cells was validated using Western analysis with Smad3-specific antibody (Fig. 9B, top). To examine whether cells isolated from lenses were indeed LECs, we conducted Western analysis using αA-crystallin antibody. Results revealed the presence of αA-crystallin, a specific marker for LECs, both Smad3+/+ and Smad3−/− cells of the third passage (Fig. 9B, middle). As shown in Fig. 9, bottom, Western analysis with β-actin antibody revealed equal loading.

We next investigated whether Prdx6 promoter activity was restored and increased in cells lacking Smad3. Smad3+/+ and Smad3−/− cells were transfected with Construct A, B, or C, and a CAT assay was performed (see “Experimental Procedures”). The activity of Prdx6 promoter constructs was increased ∼4-fold (Construct A; Fig. 9, two sites of NF-κB, dotted bar), 3-fold, (Construct B; Fig. 9, a site of NF-κB, dotted bar), and change in basal promoter activity of Construct C (lacking NF-κB site but with a RSBE site, dotted bar) was also observed. The Prdx6 promoter activity was comparable with the activity of mutant Prdx6 promoter, where RSBE sites were disrupted (Fig. 5). Collectively, the results established that the presence of Smad3 and its activation were responsible for the repression of Prdx6 promoter activity in cells facing oxidative stress, at least in eye lens, demonstrating that Smad3 was specifically and directly involved in repression of the Prdx6 promoter by TGFβ-mediated signaling. Western analysis disclosed that Smad3−/− cells harbored abundant levels of PRDX6, suggesting that suppression of Prdx6 was associated with Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling.

NF-κB in Nuclear Extract of Smad3−/− Cells Binds to Its Site(s) in the Prdx6 Gene and Tunes Prdx6 Transcription

We next sought to investigate the transactivation potential and DNA binding affinity of NF-κB in Smad3−/− or Smad3+/+ cells, as observed in Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ cells (Fig. 7A). First, we looked at DNA binding to probe containing the NF-κB site derived from the Prdx6 promoter and its interaction with nuclear extract isolated from Smad3−/− cells or Smad3+/+ cells cultured in serum-depleted medium. A gel shift assay was performed by using wild type probe containing the NF-κB-2 site (−651 to −626) and its mutant probe (see Fig. 10A). A Cm1 complex was observed in Smad3−/− cells with wild type probe but not with mutant probe, demonstrating that NF-κB in Smad3−/− cells directly binds to its responsive elements as expected. Binding affinity was significantly higher in Smad3−/− cells than in Smad3+/+. The stronger affinity of NF-κB in Smad3−/− cells may be associated with an abundance of activated NF-κB in nucleus, since Western analysis revealed significantly increased accumulation of this molecule in the nucleus of Smad3−/− cells (data not shown). Ns (Fig. 10) denotes nonspecific binding and also provides equal loading and suggests that all nuclear proteins in Smad3−/− cells are not activated. Next, we tested whether NF-κB is a regulator of transcription of the Prdx6 promoter in Smad3−/− cells, since transcriptional activity of Prdx6 along with Prdx6 mRNA and protein was found to be increased (Fig. 9). A transactivation assay was carried out by using wild type promoter and its deletion mutants. Interestingly, Prdx6 promoter activity was significantly increased in Smad3−/−-depleted cells compared with Smad3+/+ cells. The elevated promoter activity in Smad3-depleted cells demonstrates that Smad3-mediated recessive signaling is a causative factor in attenuation of Prdx6 expression (Fig. 9C, dotted bars versus black bars). Several reports have documented both prosurvival and proapoptotic roles for NF-κB (72), depending on cell type and cellular microenvironment. However, our findings support that the loss of NF-κB control of Prdx6 gene transcription was due to the prevalence of dominant Smad3-mediated repressive signaling in Prdx6−/− cells or cells under redox state. We think that once ROS-driven oxidative stress exceeded a certain threshold value, Smad3-mediated repressive signaling was triggered due to ROS-induced activation of TGFβ, thereby attenuating Nrf2 activation (58) and NF-κB regulation of Prdx6 transcription. We believe that, during aging, reduced expression of Prdx6 (49) is caused by the prevalence of this signaling. Moreover, up-regulation and activation of NF-κB have been reported during aging, since they are in redox state (74, 75), and higher levels of ROS in aging or aged organisms may account for this increased activity. Thus, our study provides evidence that aging-induced modulation of NF-κB activity played an important role by regulating survival genes, including antioxidants, but that the activity became attenuated due to ROS-induced activation of TGFβ-mediated adverse signaling.

FIGURE 10.

NF-κB in the nuclear extract from Smad3−/− cells was transcriptionally active, bound strongly to its responsive element(s). A gel shift assay was conducted with the nuclear extracts isolated from Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ cells cultured in serum-depleted medium as described earlier following incubation with radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe, NF-κB-2 (lane 1), or its mutant. Similar results were obtained with NF-κB-1 probe (data not shown).

Smad3−/−-deficient LECs Display Increased Expression of Prdx6 mRNA and Protein and Engender Resistance against TGFβ-induced Insults

Prdx6−/− cells harbor elevated levels of TGFβ and undergo spontaneous apoptosis (1, 4, 5). Activation of TGF-β induces phenotypic changes and apoptosis in many cell types, including LECs. The current study found that TGFβ did so by activating Smad3-mediated repressive signaling and attenuating NF-κB control of Prdx6 gene transcription in cells facing oxidative stress. Next we asked whether the expression level of Prdx6 would be increased in Smad3−/− cells and whether these cells would confer resistance against TGFβ1-induced insult. Cells were exposed to variable concentrations of TGFβ1 (1, 2, and 5 ng/ml) for 24 or 48 h. Cells were photomicrographed, and cell viability was estimated using an MTS assay. Smad3−/− cells showed resistance against TGFβ1-induced adverse effects (Fig. 11A, left); in contrast, significant cell death could be seen in Smad3+/+ (right). In a parallel experiment, we assessed cell viability using a survival assay (MTS assay), and results clearly demonstrated that Smad3−/− cells efficiently engendered resistance against TGFβ1-induced insult (Fig. 11B, black bar). However, TGFβ1 at 5 ng/ml showed massive cell death. Although cell death also occurred in Smad3−/− null cells, cell viability was significantly higher (data not shown). We verified expression levels of PRDX6 in both types of cells using Western analysis and RT-PCR. As expected, a significant suppression in PRDX6 level was seen in Smad3+/+ cells after TGF-β treatment, whereas expression level remained unchanged in Smad3−/− cells (Fig. 11C). However, TGFβ1 at 5 ng/ml could reduce PRDX6 expression (data not shown). We concluded that TGFβ1-induced suppression of Prdx6 was due to the presence of Smad3-mediated signaling.

FIGURE 11.

A, Smad3−/− cells engendered resistance against TGFβ-induced insults. Photomicrographs of Smad3−/− (left) or Smad3+/+ (right) cells treated with TGFβ1 (2 ng/ml). Cells were cultured for 24 h in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and then washed. The medium was replaced with 0.2% bovine serum albumin in DMEM with or without TGFβ1 for 24 or 48 h. The arrows indicate dead cells. B, cell viability of Smad3−/− cells against TGFβ1-induced insults was estimated using an MTS assay (black bar). C, TGFβ1 failed to suppress Prdx6 expression in Smad3−/− cells (top, right lane). Western analysis was conducted using cellular extract isolated from Smad3−/− and Smad3+/+ cells treated or untreated with TGFβ1. Cell lysate was prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation buffer, samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE, and Western analysis was done with anti-PRDX6 antibody. β-actin was used as loading control. D, Smad3−/− LECs showed resistance against H2O2-induced oxidative stress-mediated damage. Smad3+/+ (black bars) and Smad3−/− (gray bar) cells were exposed to H2O2 at 100 or 200 μm for 2 h. Cell viability was estimated after 24 h of recovery using an MTS assay.

Smad3−/− LECs Engender Resistance against H2O2-induced Stress

To test Smad3−/− cell survival ability against H2O2-induced stress, cells were cultured and exposed to H2O2 at 100 or 200 μm for 2 h, following the methods of Fatma et al. (1, 2). Cell viability was estimated after 24 h using an MTS assay. Smad3-depleted cells counteracted the H2O2-induced oxidative stress and survived well (Fig. 11D, gray bar). Changes in the cellular microenvironment may lead to the modification of cell-signaling molecules, including transcription factors and proteins involved in protection. Diminished cellular antioxidant levels have been documented during aging. This reduced expression of PRDX6 may be related to ROS-induced overactivation of TGFβ-mediated adverse signaling. Our current and previous studies collectively support our hypothesis that ROS-induced activation of Smad3-mediated repressive signaling is one factor that negatively regulates survival signaling by repressing NF-κB-mediated regulation of Prdx6 gene transcription, at least in the eye lens.

DISCUSSION

Cellular pathology may be triggered by the dysregulation of several survival genes due to severe ROS-driven oxidative stress. Studies in a variety of experimental systems have demonstrated ROS induction and activation of TGFβs and their involvement in the modulation of gene transcription (20). Since ROS play a major role in signal transduction, oxidative dysregulation or modulation of ROS levels and thereby abnormal expression and activation of transcriptional proteins may be a major underlying mechanism for pathologic and abnormal physiologic changes in cells bearing reduced levels of cytoprotective proteins, such as PRDX6. Our present effort was intended to reveal the mechanism by which Prdx6 gene transcription is regulated at cellular and molecular levels and how this process goes awry in pathophysiological circumstances or in cells facing oxidative stress (redox state), as in Prdx6 depletion (1, 3, 4, 10). In this context, we analyzed the Prdx6 gene promoter spanning from −1139 to +109. MatInspector (Genomatix), a Web-based computer program, disclosed the presence of two putative NF-κB sites (Fig. 1, NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2) and two RSBE elements (Fig. 1, RSBE-1 and RSBE-2). A gel shift assay as well as a transactivation assay with deletion mutants and point mutation at specific sites of NF-κB and RSBE revealed that these sites were functional and contributed to regulation of Prdx6 gene transcription (Figs. 2–7). A further goal was to dissect out the contribution and role of NF-κB and Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling in regulation of Prdx6 gene transcription in cells having normal physiological condition as well as cells facing stress. We used Prdx6-depleted (Prdx6−/−) cells as a model for redox-active cells (1, 10, 11) and Smad3-depleted cells (Smad3−/−) and their wild type cells. Promoter activity of Prdx6 was significantly reduced in Prdx6−/− cells, suggesting that Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling is involved in repression of Prdx6 gene transcription through RSBE. This was confirmed by the finding that application of TGFβ1-neutralizing antibody restored Prdx6 promoter activity in Prdx6−/− cells (Fig. 3). Frederick et al. (47) have reported that Smad3 directly binds the RSBE element in the c-myc promoter and represses its promoter activity in the presence of active TGFβ. Moreover, several mechanisms of TGFβ activation are known, and TGFβ1 can be activated by a diverse group of activators, including ROS (40, 41). Earlier, we showed that ROS activation of TGF β in Prdx6−/− cells and in aged cells attenuates the functions of the transcriptional protein LEDGF (1, 48) Considering the TGFβ activation of Smad3 (pSmad3) in Prdx6−/− cells, we examined the involvement of Smad3 as a TGFβ-dependent effectors of changes in gene expression. Western analysis studies of cellular and nuclear extracts from Prdx6−/− and Prdx6+/+ with pSmad3 and Smad3 antibodies showed the accumulation of pSmad3 in nuclei of Prdx6−/− cells (Fig. 4A, bottom), whereas Smad3 was in the cytoplasm of Prdx6+/+ cells (Fig. 4, top). These results suggest that Smad3 is present in the activated form in Prdx6−/− cells. Nuclear Smad3 bound to the probes containing RSBE sites in gel shift and supershift assays, confirming that it binds directly to SRBE sites in the Prdx6 promoter (Fig. 4, B and C). However, some residual activity of Smad3 was also observed in nuclear extract of Prdx6+/+ cells, since the cells were cultured in serum-free medium, and the ROS-mediated activation of TGFβ was expected (1). Smad3 has been found to mediate TGFβ-dependent modulation of a number of genes (47, 76, 77). The inhibitory function of TGFβ on gene transcription and thereby on cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis has been well documented, but the way in which this factor represses gene transcriptions, including that of Prdx6, is not clear. Recently, roles of the Smad family in modulation of gene transcription have been explored extensively (78–81). Smads function downstream, where Smad1, -2, and -3 (R-Smads) interact directly with type I receptors upon ligand binding, undergo phosphorylation by kinases, and convey the signals from cell membrane to nucleus (79). Smads are unique in DNA binding activity. They bind DNA not only through interacting with other transcriptional proteins, such as FAST1 (82), but also by binding directly to specific DNA sequences (47, 83). Smad3 and Smad4 directly bind to a palindromic sequence GTCTAGAC as a consensus binding sequence (SBE) (84). Recently, Frederick et al. (47) identified an RSBE in the c-myc gene promoter. They showed that the c-myc TIE is a composite RSBE and is maximally composed of 5′-TTGGCGGGAA-3′, where Smad3 directly binds and represses c-myc gene transcription. Our current study found two RSBE sites in the proximal promoter region of Prdx6 (Fig. 1, RSBE-1 and RSBE-2), and these sites functionally and physically interacted with Smad3 and repressed Prdx6 transcription in Prdx6−/− (active Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling) (Figs. 4, 5, 9 (C, D, and E), and 10). The results suggest that the Smad3 molecule is a prerequisite for TGFβ-mediated inhibition of Prdx6 repression. TGFβ has been implicated in the etiology and progression of many diseases, including cataract (35). Our study demonstrated for the first time that ROS-driven activation of TGFβ suppressed the expression of Prdx6, a protective molecule, by Smad3-mediated repressive signaling, suggesting that the prevalence of such deleterious signaling during aging may be a plausible cause of degenerative disorders, including cataractogenesis.

Recent studies have identified several ROS-signaling mechanisms in which antioxidants, such as PRDX6, are critically important and may serve as sensors for oxidative stress. Thus, in cells/tissues, some level of antioxidants is undoubtedly important in maintaining homeostatic conditions and protecting cells against the damaging effects of oxidative stress (85, 86). However, an increased or uncontrolled expression of antioxidants is not always beneficial to cells (21, 87). We believe that fine tuning is required to regulate the Prdx6 gene transcription necessary to maintain cellular homeostasis. Therefore, we asked how Prdx6 regulation is controlled both in cells under normal physiological conditions and in those facing oxidative stress. Recently, a functional antioxidant response element has been identified in the Prdx6 promoter (58). They showed that Nrf2 binds to the antioxidant response element and regulates Prdx6 gene transcription. Moreover, a basic local alignment search revealed a significant homology among human, mouse, and rat prdx6 gene promoters, ranging from −523 to −437 bp; this region contains several transcription factors and responsive elements that may participate in regulation of Prdx6 (data not shown). In the present study, by utilizing Prdx6−/− cells as a model system for redox active cells or aging cells, we found that NF-κB was present in activated form in Prdx6−/− cells (Fig. 6, A (a and b) and B). Nuclear extracts from Prdx6−/− cells as well as from Smad3−/− cells bound to NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2 probes derived from the Prdx6 promoter. Importantly, while assessing functional activity of each site of NF-κB, we found that point mutation at the NF-κB-2 site in Construct B (−839 to +109) dramatically eliminated the Prdx6 promoter activity (Fig. 7); in contrast, point mutation at NF-κB-1, NF-κB-2, or both in Construct A (−1139 to +109) of the Prdx6 promoter showed a moderate increase in promoter activity (Fig. 7). Thus, we surmise that NF-κB plays its role in fine tuning of Prdx6 expression, depending upon the cellular environment and cell types. However, Chu et al. (88) have predicted a negative role for NF-κB in antioxidant gene regulation. Recently, Gallagher and Phelan (31) showed an increase of Prdx6 expression in the presence of NF-κB inhibitor in H2.35 mouse hepatocytes. However, our study demonstrated the presence of two NF-κB sites, and these sites may play different roles in controlling Prdx6 gene expression to maintain optimum physiological levels of ROS. Furthermore, we demonstrated elevated levels of PRDX6 mRNA and protein expression in Smad3−/− LECs. These cells were resistant to oxidative stress as well as TGFβ-induced abuse, further suggesting that NF-κB optimizes Prdx6 gene expression beneficial to cells (Figs. 9–11), whereas Smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling is a major culprit in suppressing Prdx6 expression in this scenario. It has been reported that mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated healing (15, 89) and has been suggested that Smad3 plays a crucial role in tissue repair during injury (90). Importantly, recently, several reports have come forward documenting the role of PRDX6 in wound healing and in maintaining cell/tissue integrity (24). These studies as well as our own clearly indicate that PRDX6 is the real savior of cells or tissues, whereas Smad3-mediated attenuation of its expression leads to cellular damage in cells facing oxidative stress.

Earlier studies in fact demonstrated that NF-κB may function as both proapoptotic and antiapoptotic (57), and it does so by interacting with co-factors. The interaction depends on variations in the NF-κB-binding element present in the specific promoters as well as the availability of particular cofactors in the cells (71). NF-κB is a regulator of many promoters containing variations in a highly divergent core consensus DNA-binding sequence (53). Variability in consensus sequences of the κB site has been suggested to be related to specific regulatory function of NF-κB. The variation in gene regulation by NF-κB may involve two mechanisms: 1) variation at NF-κB binding sequence and selection of coactivator(s) according to cell requirements to maintain physiology (71) and 2) possible affinity of NF-κB dimer combinations for different sites (70). How NF-κB operates Prdx6 gene transcription in lens or LECs under redox conditions is largely unknown. Our present findings demonstrate that the Prdx6 gene has two functional NF-κB binding sites: NF-κB-1 (948GCCTCCCACA939, present at the negative strand) and NF-κB-2 (644TGGGAATTCA635). Once NF-κB is in the nucleus, it binds to κB consensus sequences (5′-GGGRNYYYCC-3′, where R is purine, Y is a pyrimidine, and N is any nucleotide) (91). However, variations in NF-κB sites have been reported (16, 92), in which p50 binds to 5′-GGGGATYCCC-3′ and p65 binds to consensus 5′-GGGRNTTTCC-3′. Considerable variation was possible in the sequences between NF-κB-1 and NF-κB-2 sites present in the Prdx6 promoter. However, perhaps the most unexpected finding of this study was that the point mutation of NF-κB sites in the promoter ranging from −1139 to +109 released promoter activity, although the activity was moderately increased, whereas disruption of NF-κB-2 sites of Construct B (−839 to +109) eliminated Prdx6 promoter activity. This observation requires that caution be exercised in making generalizations about the function of NF-κB sites in the gene promoter. Furthermore, the different κB motifs may be able to form selective associations with specific cofactors, suggesting that, in vivo, the cell may use this type of differential recognition of binding sequences to fine tune its response to various external signals. This fine tuning might control the expression levels of genes like Prdx6 that should be physiologically relevant to cell survival. However, based on deletion Constructs A and B, the present study revealed the possible presence of underlying putative enhancer elements between −839 and −1139 bp of the Prdx6 promoter. An analysis of this promoter region revealed several putative sites for transcriptional factor binding, such as ATF2 and ATF6, HNF4, NKXs, c-ETS (p54), KLF4 (Kruppel-like factor 4), MZF1, c-Maf, AP1, antioxidant response element/Maf, and AP1-related factors. These transcriptional proteins have diversified roles in gene regulation and should provide clues to the functions of PRDX6 and its effects in such varied situations as cell survival and differentiation to development of cancer (1, 4, 5, 9, 17, 23, 24, 31, 58, 93) Further work is needed to explore the role of transcriptional factors, particularly in Prdx6 regulation.

In summary, the present study unveiled a novel mechanism of Prdx6 repression, showing the involvement of Smad3-mediated TGFβ-induced dominant repressive signaling in cells facing oxidative stress. Additionally, we propose a novel role for NF-κB as a stress-sensing molecule that determines optimal regulation of Prdx6 transcription that may require fine tuning to avoid overshooting the desired beneficial effects to the point of perturbing the delicate redox balance necessary for the maintenance of cellular functions, at least in eye lens/LECs. Findings of this study add to knowledge of how the gene network is changed during aging or oxidative stress and how these changes act to turn survival signaling into deleterious signaling. Although a more complete understanding of LEC cellular response to oxidative stress is required, we believe that these events are causally related (i.e. that the age-related reduction in PRDX6 in lens tissues leads to oxidative damage of membrane or cytosolic or nuclear factors important to maintain normal lens physiology). As a consequence of this damage, the cell homeostatic system fails, leading to cataractogenesis or other degenerative disorders. The outcome of the study described here should provide significant insight into the progression and plausible etiology of oxidative stress-associated disorders and deliver the background for developing antioxidant and/or transcription factor(s) modulation-based therapy for preventing or treating cataract and age-associated diseases in general.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NEI, Grants EY-13394 and EY017613 (to D. P. S.). This work was also supported by a grant from Research for Preventing Blindness (to R. P. B.).

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- LEC

- lens epithelial cell

- SBE

- Smad-binding element

- RSBE

- repressive Smad3-binding element

- TGFβ

- transforming growth factor β

- TIE

- TGFβ-inhibitory element

- CAT

- chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunoassay

- NAC

- N-acetylcysteine

- MTS

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2 to 4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium salt

- Ab

- antibody

- H2-DCF-DA

- 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fatma N., Kubo E., Sharma P., Beier D. R., Singh D. P. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12,734–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fatma N., Singh D. P., Shinohara T., Chylack L. T., Jr. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276,48899–48907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher A. B., Dodia C., Manevich Y., Chen J. W., Feinstein S. I. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274,21326–21334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubo E., Fatma N., Akagi Y., Beier D. R., Singh S. P., Singh D. P. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294,C842–C855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubo E., Miyazawa T., Fatma N., Akagi Y., Singh D. P. (2006) Mech. Ageing Dev. 127,249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubo E., Urakami T., Fatma N., Akagi Y., Singh D. P. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 314,1050–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manevich Y., Fisher A. B. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38,1422–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J. R., Yoon H. W., Kwon K. S., Lee S. R., Rhee S. G. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 283,214–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan S. A., Wang X., Wallbrandt P., Forsman-Semb K., Paigen B. (2003) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 35,1110–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X., Phelan S. A., Forsman-Semb K., Taylor E. F., Petros C., Brown A., Lerner C. P., Paigen B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278,25179–25190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y., Feinstein S. I., Manevich Y., Ho Y. S., Fisher A. B. (2006) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 8,229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank S., Munz B., Werner S. (1997) Oncogene 14,915–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T. S., Dodia C., Chen X., Hennigan B. B., Jain M., Feinstein S. I., Fisher A. B. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274,L750–L761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparling N. E., Phelan S. A. (2003) Redox. Rep. 8,87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashcroft G. S., Yang X., Glick A. B., Weinstein M., Letterio J. L., Mizel D. E., Anzano M., Greenwell-Wild T., Wahl S. M., Deng C., Roberts A. B. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1,260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baeuerle P. A. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1072,63–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang X. Z., Li D. Q., Hou Y. F., Wu J., Lu J. S., Di G. H., Jin W., Ou Z. L., Shen Z. Z., Shao Z. M. (2007) Breast Cancer Res. 9,R76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X., Rubock M. J., Whitman M. (1996) Nature 383,691–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abate C., Patel L., Rauscher F. J., 3rd, Curran T. (1990) Science 249,1157–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annes J. P., Munger J. S., Rifkin D. B. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116,217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An J. H., Blackwell T. K. (2003) Genes Dev. 17,1882–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Phelan S. A., Petros C., Taylor E. F., Ledinski G., Jürgens G., Forsman-Semb K., Paigen B. (2004) Atherosclerosis 177,61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kümin A., Huber C., Rülicke T., Wolf E., Werner S. (2006) Am J. Pathol. 169,1194–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]