Abstract

The Na,K-ATPase is an αβ heterodimer responsible for maintaining fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in mammalian cells. We engineered Madin-Darby canine kidney cell lines expressing α1FLAG, β1FLAG, or β2MYC subunits via a tetracycline-regulated promoter and a line expressing both stable β1MYC and tetracycline-regulated β1FLAG to examine regulatory mechanisms of sodium pump subunit expression. When overexpression of exogenous β1FLAG increased total β subunit levels by >200% without changes in α subunit abundance, endogenous β1 subunit (β1E) abundance decreased. β1E down-regulation did not occur during β2MYC overexpression, indicating isoform specificity of the repression mechanism. Measurements of RNA stability and content indicated that decreased β subunit expression was not accompanied by any change in mRNA levels. In addition, the degradation rate of β subunits was not altered by β1FLAG overexpression. Cells stably expressing β1MYC, when induced to express β1FLAG subunits, showed reduced β1MYC and β1E subunit abundance, indicating that these effects occur via the coding sequences of the down-regulated polypeptides. In a similar way, Madin-Darby canine kidney cells overexpressing exogenous α1FLAG subunits exhibited a reduction of endogenous α1 subunits (α1E) with no change in α mRNA levels or β subunits. The reduction in α1E compensated for α1FLAG subunit expression, resulting in unchanged total α subunit abundance. Thus, regulation of α subunit expression maintained its native level, whereas β subunit was not as tightly regulated and its abundance could increase substantially over native levels. These effects also occurred in human embryonic kidney cells. These data are the first indication that cellular sodium pump subunit abundance is modulated by translational repression. This mechanism represents a novel, potentially important mechanism for regulation of Na,K-ATPase expression.

In eukaryotic cells, the primary protein responsible for maintaining cellular ionic homeostasis is the Na,K-ATPase or sodium pump (1). This is an integral plasma membrane P-type ATPase that actively transports three Na+ ions out of and two K+ ions into the cell accomplished by the hydrolysis of one ATP per transport cycle, thus maintaining intracellular low Na+ and high K+ concentrations. The secondary transport of a variety of ions and solutes across the membrane is enabled by the sodium electrochemical potential gradient resulting from sodium pump activity (2). The sodium pump plays a vital role in fluid and electrolyte balance and is a major factor in the regulation of blood pressure in humans.

The Na,K-ATPase functions as a heterodimer consisting primarily of α and β subunits. There are four distinct isoforms of α subunit (α1, α2, α3, and α4) and three isoforms of β subunit (β1, β2, and β3) that are tissue-specific in their expression (3, 4). The α subunit has 10 transmembrane domains (5), has an estimated molecular mass of 113 kDa, and is responsible for the catalytic functions of the enzyme (6). It is organized into actuator (A), nucleotide-binding (N) and phosphorylation (P) domains, and conformational transitions in these domains couple ATP hydrolysis to ion transport (7, 8). These conformational transitions in the α subunit are accompanied by structural changes in the β subunit (9). The α subunit is accompanied to the plasma membrane by the β subunit whose presence increases the stability the sodium pump at the membrane (10, 11). The β subunit, unlike the α subunit, does not require its association with the α subunit to exit the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 (12, 13). The estimated molecular mass of the β1 subunit is 33.6 kDa in its unglycosylated state, and it is normally about 55 kDa because it contains three sites of extensive glycosylation (14, 15). The glycosylation of β1 subunit, although not necessary for α interaction, is important for β subunit and sodium pump stability, and it has been implicated in affecting cell-cell adhesion (16–18). The β subunit also contains three extracellular disulfide bridges that are essential for stabilization of the cation-occluded state and enzymatic activity (19).

In most polarized epithelial cells, the α and β subunits are expressed at an equimolar ratio, assembled as heterodimers, and delivered to the basolateral membrane where they function in active transport (20, 21). To maintain cell viability under a variety of conditions, mechanisms have evolved to regulate the abundance of sodium pump subunits and ATPase activity. In low extracellular potassium conditions, sodium pump expression and activity increase to facilitate the uptake of potassium ions into the cell thus maintaining the electrochemical potential gradient in a variety of cell types (22, 23). The low potassium-stimulated increase of α1 and/or β1 transcription involves the coordination of cellular components including protein kinase A, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, histone deacetylase, protein kinase C, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (24). Transcription factors are also involved in sodium pump gene regulation as was observed in renal cells undergoing hypoxia where β1 transcription was enhanced by the binding of SP1/SP3 near the promoter region of β1 (25, 26). The up- or down-regulation of sodium pump expression and activity plays a role in preventing the exacerbation of some diseases as is the case during hyperbaric oxygenation of the lung where increased α1 and β1 subunit levels help to prevent pulmonary edema (27). In renal carcinoma-like cells, the increased expression of heterologous sodium pump β1 subunits reduces cell motility and invasiveness by forming intercellular interactions between adjacent β subunits (28, 29). Contrary to its disease preventative characteristics, altered sodium pump expression levels may contribute negatively toward cell health. For example, in mouse APP+PS1 cells, which develop amyloid plaques and memory deficits resembling Alzheimer disease, decreased levels of Na,K-ATPase activity and gene expression in the amyloid-containing hippocampi likely contribute to the disruption of ion homeostasis, blocking of intraneuronal signal processing, and neuritic dystrophia (30, 31).

In recent studies we have shown that overexpression of the β subunit in MDCK cells can be achieved with no change in α subunit levels (32). During that work we noticed that when exogenous β subunits were overexpressed the endogenous β subunit abundance fell. This suggested that some regulatory mechanism was present that served to limit sodium pump subunit abundance. In the present work we provide evidence that both α and β subunit levels are regulated and demonstrate that this regulation takes place via translational repression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Line Creation and Maintenance

The MDCK/FlpIn/T-Rex cell line used in these experiments was obtained by using a pcDNA6/TR vector (Invitrogen) to introduce a tetracycline-regulatable cytomegalovirus promoter into the MDCK/FlpIn cell line. The MDCK/FlpIn cell line was generously donated by the late Dr. Robert B. Gunn. This modified cell line allows gene of interest integration into a specific Flp recombination target (FRT) site when the Flp-In expression vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO (Invitrogen) containing the gene of interest and the Flp recombinase vector pOG44 (Invitrogen) are cotransfected into the cells via Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen 11668-027). In the MDCK/FlpIn/T-Rex transfected cells, binding tetracycline (tet) to the operon derepresses the cytomegalovirus promoter and induces expression of the gene of interest. In this work, the MDCK/FlpIn/T-Rex host cell line will be referred to as the MDCK cell line. Methods for creating the MDCK cell line stably expressing tet-inducible sheep Na,K-ATPase β1 subunit containing a carboxyl-terminal FLAG tag (MDCK/β1FLAG) or a carboxyl-terminal MYC tag (MDCK/β1MYC) were described previously (33). In a similar fashion, MDCK cell lines capable of tet-induced expression of either sheep α1 subunit containing a FLAG tag on the carboxyl terminus (MDCK/α1FLAG), rat β2 subunit containing a MYC tag on the carboxyl terminus (MDCK/β2MYC), or one of two chimeras containing sheep β1 fused to rat β2 sequences were also created. The β1/β2-MYC chimera contains 77 amino acid residues of the amino terminus, transmembrane domain, and 15 amino acid residues of the carboxyl terminus of β1 fused to 219 amino acids containing the carboxyl terminus of β2 and a MYC epitope tag. The β2/β1-FLAG chimera contains 82 amino acid residues of the amino terminus, transmembrane domain, and 15 amino acids of the carboxyl terminus of β2 fused to 236 amino acids containing the carboxyl terminus of β1 and a FLAG epitope tag. In certain experiments, an MDCK/FlpIn/T-Rex cell line stably expressing two distinguishable β1 subunits was necessary. To obtain this cell line, MDCK/β1FLAG cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1/V5-His C vector (Invitrogen) containing DNA from sheep β1 subunit tagged with a carboxyl-terminal MYC epitope (MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC). In this cell line, β1FLAG expression is controlled via a tet-regulatable promoter whereas β1MYC is constitutively expressed.

All cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Mediatech 10-013-CV) supplemented with 25 mm HEPES buffer (Mediatech 25-060-CI), 100 unit/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen 15240), and 10% tetracycline-free fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals S10350) was used for all cell lines. 6 μg/ml blasticidin (Research Products International Corp. 27073), 150 μg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen 46-0509), 400 μg/ml hygromycin B (Mediatech 30-240-CR), and/or 500 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen 10131-035) were added to the growth medium as appropriate for selection. Expression of the tet-regulatable genes of interest was achieved by adding 1 μg/ml tetracycline to the cell growth medium for various times. In some experiments, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide was also added to the growth medium. Cell density was maintained by splitting cells when they became confluent. Cells were split by washing two times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); incubated with 0.05% trypsin, EDTA until they detached from the plate; and then placed onto a new plate with fresh growth medium.

Membrane Preparation

Confluent cell monolayers were washed two times with PBS and harvested by scraping, and whole cells were pelleted at 1000 × g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in cold homogenizing buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 2 mm EDTA, 250 mm sucrose, pH 7.4) containing Complete-Mini protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche Applied Science). The cells were disrupted by sonication and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min. The disrupted cell supernatant was collected and either centrifuged at 55,000 rpm for 30 min in a TLA55 rotor to obtain total membranes (TMs) or placed in a five-step sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 45,000 rpm in a Beckman MLS50 swinging bucket rotor to separate enriched membrane fractions as described previously (5, 34). The ER-, Golgi-, and plasma membrane (PM)-enriched fractions were collected from the sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 55,000 rpm in a TLA55 rotor for 1 h, and the membrane pellet was resuspended in homogenizing buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined by the Lowry assay (5).

Antibodies

Antibody dilutions used for immunoblotting were as follows: 1:200,000 for mouse anti-α1 (ABR MA3-929), 1:200,000 for mouse anti-β1 (ABR MA3-930), 1:1000 for mouse anti-MYC (Cell Signaling Technology Inc. 2276), 1:1000 for rabbit anti-FLAG (Sigma F7425), 1:1000 for rabbit anti-FLAG (Abnova PAB0900), 1:5000 for mouse anti-actin (Abcam ab20272), 1:500 for mouse anti-actin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank JLA20), 1:5000 for mouse anti-β-Catenin (BD Transduction Laboratories 610153), and 1:5000 for mouse anti-α6F (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Optimized antibody dilutions used for immunoprecipitation were 1:50 for the polyclonal rabbit anti-α loop antibody that was raised against α1 subunit cytoplasmic M4M5 loop (35) or 1:50 for the polyclonal rabbit anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma F7425). Peroxidase AffiniPure goat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories 115-035-146) or goat anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories 111-035-144) secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5000.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were subject to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis according to previously described procedures (12). TM or membrane-enriched fractions were incubated at room temperature with 2× Laemmli sample buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol for 1 h. Samples were separated by 10, 12, or 15% SDS-PAGE; transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes; and blocked with 5% milk in PBS for 1 h. Primary or secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 1% milk + 0.1% Tween 20 and used for immunoprobing for 2 h at 25 °C or overnight at 4 °C. Following immunoprobing with primary and secondary antibodies, blots were washed three times with PBS + 0.1% Tween 20. Chemiluminescent Western blotting substrate (Pierce) was used for peroxidase detection, and the resulting signal intensity was quantified on a Bio-Rad Chemidoc XRS using Quantity One Version 4.6.2 software and corrected for protein loading using either anti-actin or anti-β-catenin antibodies when appropriate.

Immunoprecipitation

In immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments, 5–50 μg of TM or PM proteins were solubilized in 500 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer (150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 2 mm EDTA, pH 7.5) (36) containing 2% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside for 1 h at 4 °C. To remove insoluble material, the samples were spun in a TLA55 rotor for 30 min at 55,000 rpm. The soluble protein in the supernatant was collected, and 10% was saved for input lanes on a Western blot. The remaining supernatant was transferred to a new tube containing the immunoprecipitating antibody and incubated with rotation for 24 h at 4 °C. Then 100–200 μl of immobilized protein G-agarose beads (Pierce 20399) were added to the IP sample and allowed to rotate for 2 h at 25 °C. IP beads were pelleted at 500 × g for 5 min, and unbound supernatant was discarded. The IP beads were washed three times with 1 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer + 2% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside, once with 0.5 m NaCl in immunoprecipitation buffer, and once with deionized H2O. Each wash was for 5 min with rotation at 25 °C followed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 1 min and removal of the supernatant by aspiration. Precipitated proteins were eluted from the beads by incubating in 2× sample buffer + β-mercaptoethanol for at least 30 min at room temperature followed by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 5 min. The eluted proteins were resolved on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel and detected by Western blot analysis.

Endoglycosidase Treatment

To visualize the mass differences of endogenous β1 (β1E), β1FLAG, or β2/β1-FLAG subunits in anti-β1 antibody immunoblots, asparagine-linked glycosylation was removed from the subunits by peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F; New England Biolabs) treatment prior to SDS-PAGE according to manufacturer's instructions. To deglycosylate proteins after IP, proteins were immunoprecipitated as described above under “Immunoprecipitation,” and the washed protein-antibody-bead complex was incubated with 10 μl of PNGase F denaturation buffer for 10 min at 65 °C. Then 10 μl of Nonidet P-40 and 10 μl of G7 reaction buffer were added followed by incubation with 2 μl of PNGase F (New England Biolabs) for at least 2 h at 37 °C. The deglycosylated proteins were then eluted from the bead with 2× sample buffer + β-mercaptoethanol and used for subsequent SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

35S Radiolabeling

MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown on a 10-cm-diameter plate with or without tet for 5 days. The confluent cells were washed twice with PBS followed by adding starvation medium (methionine- and cysteine-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 25 mm HEPES) for 20 min. The starvation medium was removed, and 3 ml of pulse medium (starvation medium supplemented with 150 μCi of 35S-labeled methionine/cysteine (GE Healthcare AGQ0080)) was added to the cells for 24 h without or with tet. The pulse medium was removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS. Membrane fractions were collected, protein concentrations were determined, and 20 μg of PM protein was subjected to IP with anti-α loop antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were deglycosylated with PNGase F (see above), eluted from the beads with 2× sample buffer + β-mercaptoethanol, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blot, or the membranes were dried and exposed to film.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from either MDCK/β1FLAG or MDCK/α1FLAG cells grown in the presence or absence of tet for 3 days was isolated from cells using the RNeasy Mini kit and QIAShredder (Qiagen). After total RNA was eluted from the column with RNase-free H2O, RNA/DNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry at absorbances of 260 and 280 nm. Only samples that contained A260:A280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 were used. DNA was removed from RNA samples by adding deoxyribonuclease I (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's methods. Samples were then screened for contaminating DNA by conducting standard PCR methods using 2× PCR MasterMix (Fermentas) and primers described in Table 1. DNA-free mRNA was converted to cDNA by reverse transcription using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT)20 primers. Quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) were performed in triplicate using SYBR GreenER qPCR Supermix for iCycler (Invitrogen), an iQ5 Bio-Rad Cycler calibrated for SYBR Green dye according to the manufacturer's protocols, and species-specific primer sets (Table 1) to amplify β-actin, α1, or β1 cDNA from −tet or +tet samples. An initial uracil-DNA glycosylase incubation step at 50 °C for 2 min prior to qPCR cycling destroyed all contaminating dU-containing products. Inactivation of uracil-DNA glycosylase and activation of DNA polymerase was achieved by incubating samples at 95 °C for 8 min and 30 s. cDNA amplification by qPCR was performed by incubating reactions for 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. During the 60 °C incubation step, fluorescent signal acquisition occurred, and threshold values were determined. Finally melting curve analysis yielding a single peak for each primer set was achieved by incubating reactions at 95 °C for 1 min and 55 °C for 1 min followed by 80 cycles at 55 °C + 0.5 °C/cycle for 10 s. The relative quantity of mRNA from tet samples with respect to no-tet samples was determined using the Livak and Schmittgen method (2−ΔΔCT) (37) where ΔCT equals mean threshold cycle minus mean CT of β-actin and ΔΔCT equals ΔCT of tet sample minus ΔCT of no-tet sample. The threshold values for β-actin were similar in all samples regardless of varied tet growth conditions.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of qPCR primers for species-specific target genes

Primers used to amplify species-specific cDNA synthesized from RNA of various cell types for use in quantitative PCR are shown. ATP1B1, endogenous Na,K-ATPase β1 subunit; ATP1A1, endogenous Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit; ACTB, endogenous β-actin; ATP1B1-FLAG, FLAG epitope-tagged exogenous Na,K-ATPase β1 subunit; ATP1A1-FLAG, FLAG epitope-tagged exogenous Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit.

| Gene product | Species | Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bp | ||||

| MDCK/β1FLAG cells | ||||

| ATP1B1 | Canine | CAAGGATAGAATTGGGAACGTG | AGTGGGAAAGATTTGTGCTTGT | 277 |

| ATP1A1 | Canine | CGGCCTTCTTCGTCAGTATC | CAGGGCAGTAGGACAGGAAA | 160 |

| ACTB | Canine | CCACGAGACCACCTTCAACT | ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC | 262 |

| ATP1B1-FLAG | Sheep | GGAAAAAGTCGGAAGCATAGAGT | CATCATCATCCTTATAATCCATGC | 268 |

| HEK/β1FLAG cells | ||||

| ATP1B1 | Human | TATTTTGGACTGGGCAACTC | AGTGGGAAAGATTTGTGCTTGT | 252 |

| ATP1A1 | Human | ACACACTCTGCATCCGACAC | AGTCTTTCCGGGTGTTCCTT | 240 |

| ACTB | Human | CCACGAAACTACCTTCAACT | ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC | 243 |

| ATP1B1-FLAG | Sheep | GGCAAGCGAGACGAAGATAA | CATCATCATCCTTATAATCCATGC | 288 |

| MDCK/α1FLAG cells | ||||

| ATP1B1 | Canine | CAAGGATAGAATTGGGAACGTG | AGTGGGAAAGATTTGTGCTTGT | 277 |

| ATP1A1 | Canine | GTAAGACCAGGAGGAACTCAG | TCACAACGTGCAGGACAC | 286 |

| ACTB | Canine | CCACGAGACCACCTTCAACT | ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC | 262 |

| ATP1A1-FLAG | Sheep | GCAAGACCAGGAGGAATTCC | TTTATCATCATCATCTTTATAGTCG | 282 |

RESULTS

Overexpression of Exogenous β1FLAG Causes Down-regulation of Endogenous β1 Subunits in MDCK Cells

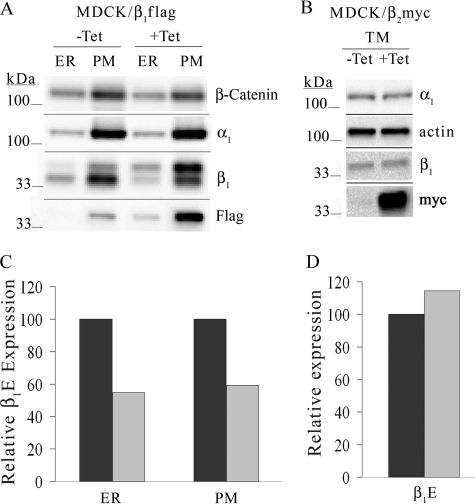

Our previous report demonstrates that the exogenous expression of Na,K-ATPase β1 subunit in MDCK cells increases total β1 subunit expression more than 200% over native β1 levels but does not alter α1 subunit abundance (33). To determine whether the exogenous expression of β1FLAG subunit affects β1E subunit abundance, membrane-enriched protein fractions from MDCK/β1FLAG cells grown in the presence or absence of tetracycline were treated with PNGase F to remove the three N-linked glycans on β1E and β1FLAG subunits, allowing visual distinction of their respective 35.2- and 36.3-kDa molecular masses. The Western blot in Fig. 1A shows that α1 subunit abundance was unchanged when β1FLAG was induced via the presence of tet. Cells treated with tet exhibited an increase in the total amount of β1 subunits mostly due to β1FLAG expression (Fig. 1A, upper band in anti-β1 blot), although the abundance of β1E subunit (Fig. 1A, lower band in anti-β1 blot) was reduced by about 40% (compare lanes 1 and 3 or lanes 2 and 4). Quantification of β1E signal intensity (Fig. 1C) was determined by densitometry (see “Experimental Procedures”). This effect was not due to the presence of the FLAG epitope because overexpression of MYC-tagged β1 subunits had the same effect (data not shown).

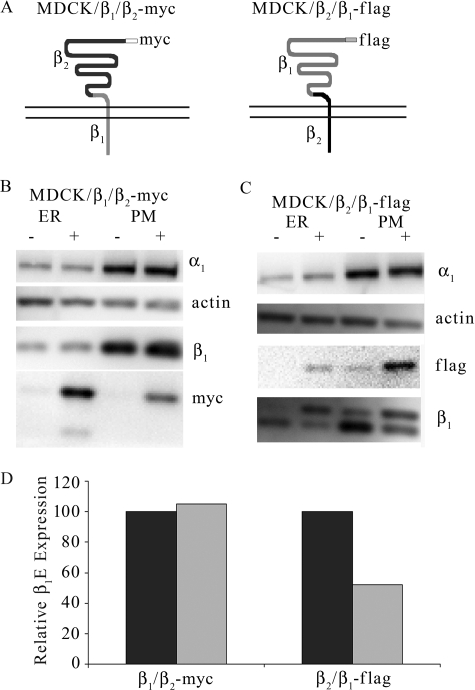

FIGURE 1.

Isoform-specific subunit overexpression causes reduction in β1 subunit abundance. MDCK/β1FLAG or MDCK/β2MYC cells were grown in medium containing 1 μg/ml tet for 5 days (+) or grown in tet-free medium (−). Cells were harvested and fractionated, and protein concentrations were determined. 5 μg of ER, PM, or TM protein was treated with PNGase F followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot detection. Membranes were probed with anti-actin, anti-β-catenin, anti-α1, anti-β1, anti-MYC, or anti-FLAG antibodies. A, relative abundance of β1E subunits from the ER- or PM-enriched fractions of MDCK/β1FLAG cells were quantified and are displayed in C. B, total membranes from MDCK/β2MYC cells were analyzed by Western blot, and β1 subunit abundance was quantified and is shown in D. Quantification of β1E subunit expression from +tet samples (light bars) was determined and corrected for β-catenin or β-actin loading controls and is shown as a percentage from −tet samples (dark bars).

Isoform Specificity of Down-regulation

To determine whether the reduction in β1E subunit abundance is an effect specific to β1 isoform overexpression, we used the MDCK/β2MYC cell line. When these polarized cells are grown in the presence of tet, they express β2MYC subunits in the ER and at the basolateral membrane, and the β2MYC subunits are not associated with α1 or β1 subunits (33). MDCK/β2MYC cells were grown in the absence or presence of tet for 72 h. Total membranes were collected and used for immunoblot analysis to visualize both ER- and PM-localized subunits. Fig. 1B demonstrates that although β2MYC subunit was expressed at significant levels in the presence of tet (lower panel) its overexpression did not significantly alter β1 or α1 subunit expression levels. Endogenous β1 subunit abundance was quantified from the anti-β1 immunoblot and is shown in Fig. 1D.

β1 Subunit Synthesis Is Decreased during β1FLAG Overexpression

The apparent decrease in native β1 subunit levels during β1FLAG overexpression prompted us to investigate the abundance of newly translated β1FLAG and β1E subunits. We examined levels of newly synthesized α and β subunits by incorporating 35S-labeled methionine/cysteine into the growth medium of MDCK/β1FLAG cells. After 24 h, the PM-enriched fraction was collected, and proteins precipitated by an anti-α loop antibody were examined by autoradiography and Western blotting. The autoradiogram in Fig. 2A shows only proteins that were translated and associated with α subunit within 24 h after the addition of 35S. The amount of newly synthesized β1E subunits decreased by about 80% when β1FLAG expression was induced. The immunoblot in Fig. 2B (anti-β, lower band) shows both the 35S-labeled newly synthesized β1E subunits and unlabeled residual β1E subunits. These were reduced by about 65% when β1FLAG was expressed for 24 h (quantification in Fig. 2C). The disparity in the percentage of β1E reduction in the autoradiogram (80%) compared with the immunoblot (65%) is because the immunoblot, but not the autoradiogram, includes residual β1E subunits that were synthesized prior to 35S treatment. The residual β1E subunits likely account for about 15% of the β1E subunits detected in the immunoblots.

FIGURE 2.

Reduced protein synthesis of β1E when β1FLAG expression is induced. MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown in the presence or absence of tet for 5 days. Cells were then radiolabeled with 35S-labeled methionine/cysteine for 24 h with or without tet present in the growth medium. Cells were harvested and fractionated, and protein concentrations were determined. 20 μg of PM-enriched protein was subjected to IP by anti-α1 loop antibody, treated with PNGase F, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiogram (A) or Western blot detection using anti-α1 and anti-β1 antibodies (B). Endogenous β1 signal intensities from −tet (dark bars) or +tet (light bars) samples from autoradiogram or Western blot were quantified and are displayed in C.

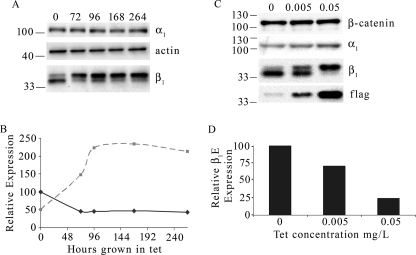

Because significant reduction of β1E subunit abundance occurred within 24 h post-β1FLAG induction, it was of interest to determine whether β1E levels would decrease further during longer tet treatments. MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown with tet for 0, 72, 96, 168, or 264 h. The Western blot of total membranes probed with anti-β1 antibody is shown in Fig. 3A and demonstrates that β1E subunit abundance was reduced by about 50% during the initial 72 h of tet induction and that further reduction did not occur over longer time periods (Fig. 3B). β1FLAG expression continued to increase after tet addition up to 96 h and then maintained an expression level of about 225% compared with the initial expression of β1E (Fig. 3B). To determine whether the extent of overexpression of β1FLAG causes a dose-dependent response in the down-regulation of endogenous β, MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown in 0, 0.05, or 0.005 μg/ml tet for 3 days. Immunoblots of plasma membrane-enriched fractions were probed with anti-α, anti-β-catenin, anti-β, and anti-FLAG antibodies and are shown in Fig. 3C. The increase in tet concentration was accompanied by an increase in β1FLAG overexpression (lowest panel) and a steady decrease in β1E abundance. Quantification in Fig. 3D shows that the reduction in β1E abundance was roughly 30 and 70% in cells grown with 0.005 and 0.05 μg/ml tet, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

β1E subunit abundance varies with overexpression level of β1FLAG. MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown in tet for varying amounts of time (A) or at varying concentrations (C). A, 10 μg of TM from MDCK/β1FLAG cells grown in 1 μg/ml tet for 0, 4, 72, 96, or 264 h was subjected to PNGase F treatment, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis using anti-actin, anti-β1, or anti-α1 antibodies. In the anti-β1 antibody immunoblot, the upper band signifying β1FLAG (dashed line) and the lower band corresponding to β1E (solid line) were quantified, corrected for actin loading, and plotted as a percentage of β1E at 0-h tet induction and are displayed in B. C, 5 μg of PM protein from MDCK/β1FLAG cells treated with 0, 0.005, or 0.05 μg/ml tet for 3 days was treated with PNGase F and subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were probed with anti-α1, anti-β1, anti-β-catenin, or anti-FLAG antibodies. Quantitation of β1E expression (lower band in anti-β1 immunoblot) was corrected for actin loading and determined as a percentage of expression in no-tet samples (D).

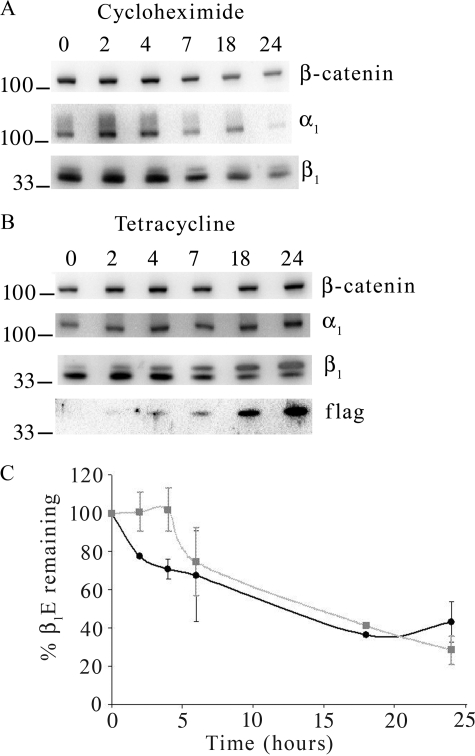

Unaltered Degradation of Endogenous β1 during Exogenous β1FLAG Expression

The decrease in endogenous β1 subunit levels that are seen when β1FLAG is overexpressed could be due to an increased rate of degradation of the endogenous polypeptide. Using cycloheximide to block translational elongation and synthesis of new proteins, we determined the degradation rate of β1E subunit under control (−tet) conditions. The degradation rate was then compared with the rate of the β1E subunit decrease during β1FLAG overexpression. MDCK/β1FLAG cells were treated for 0, 2, 4, 7, 18, or 24 h with either cycloheximide (Fig. 4A) or tet (Fig. 4B), and total cell lysates were collected and used for Western blot. β1E signal intensity was quantified and is displayed in Fig. 4C. The normal degradation rate of β1E subunit was determined by cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 4A), and ∼70% of β1E subunits were degraded in 24 h. This rate when compared with the rate of β1E subunit reduction when cells expressed β1FLAG showed a 55% decrease after 24 h (Fig. 4B). Thus there was not any dramatic increase in β1E subunit degradation rates caused by the overexpression of β1FLAG.

FIGURE 4.

Degradation of β1E is not increased by β1FLAG expression. MDCK/β1FLAG cells were grown in the presence of cycloheximide (A) or tetracycline (B) for 0, 2, 4, 7, 18 or 24 h and 10 μg of total membrane protein was PNGase F-treated and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-α1, anti-β1, anti-β-catenin, or anti-FLAG antibodies. The lower bands in anti-β1 antibody blots, representing β1E subunit expression, from cells treated with cycloheximide (square data points) or tetracycline (circle data points) were quantified and are displayed as a percentage of expression at 0 h (C). Data points containing S.E. bars are representative of three independent experiments.

Endogenous β1 Down-regulation Is Controlled Post-transcriptionally

To determine whether the down-regulation of β1E subunit during β1FLAG overexpression is due to changes in its mRNA abundance, qPCR was performed on mRNA- derived cDNA isolated from MDCK/β1FLAG cells with or without 72-h tet treatment. Each primer set used in qPCR experiments recognizes a particular region of the gene that is specific to the species in which the gene was derived, such as canine for endogenous β1, β1, or β-actin and sheep for exogenous β1FLAG (Table 1). The qPCR data in Table 2 indicate that the amount of β1FLAG mRNA in MDCK/β1FLAG cells was significantly increased when tet was added to cell growth medium (a 141.85 ± 38.22-fold change over trace amounts of β1FLAG mRNA in cells not treated with tet). At the same time, β1E and α1 mRNA exhibited no significant change when tet was added to cells (0.91 ± 0.33- and 0.84 ± 0.24-fold, respectively). This result strongly suggests that the effects on endogenous β subunit abundance are not mediated via mRNA, i.e. via transcriptional regulation.

TABLE 2.

Relative gene expression in various cell types as determined by quantitative PCR

Relative -fold changes in gene expression from ≥3 independent qPCR experiments were determined. Mean threshold values of amplified cDNA derived from the mRNA of various cell types treated with tet were normalized against β-actin calculated in comparison with untreated (−tet) samples according to the Livak and Schmittgen method (2−ΔΔCT) (37). Each value represents means ± S.E.

| Gene | -Fold change |

|---|---|

| MDCK/β1FLAG cells | |

| β1 endogenous | 0.91 ± 0.33 |

| β1FLAG | 141.85 ± 38.22 |

| α1 | 0.84 ± 0.24 |

| HEK/β1FLAG cells | |

| β1 endogenous | 1.13 ± 0.28 |

| β1FLAG | 46.40 ± 13.33 |

| α1 | 1.22 ± 0.23 |

| MDCK/α1FLAG cells | |

| β1 | 1.043 ± 0.26 |

| α1FLAG | 40.02 ± 21.69 |

| α1 endogenous | 1.15 ± 0.39 |

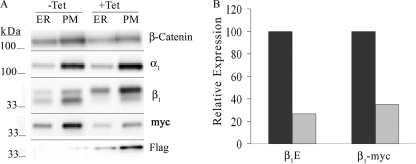

To determine whether the reduction in β1E subunits during β1FLAG expression is caused by regulatory machinery acting on the untranslated region (UTR) of β1E, we created the MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC cell line. In this cell line, both β1FLAG and β1MYC cDNA was derived from sheep, and neither contains β1 subunit 3′- or 5′-UTR. Transcription of tet-regulated β1FLAG subunit or stably expressed β1MYC subunit is enabled independently because each has their own cytomegalovirus promoter. MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC cells were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of tet, and ER- or PM-enriched membrane fractions were treated with PNGase F and subjected to Western blot analysis (Fig. 5A). The immunoblot probed with anti-β1 antibody revealed that the abundance of β1E subunit (lower band) in PM fractions was reduced by about 70% when β1FLAG was expressed. Similarly when β1FLAG was expressed, stable β1MYC subunit expression was reduced in PM-enriched fractions by about 65% as determined by probing with anti-MYC antibody (Fig. 5, A and B). Separation of β1FLAG and β1MYC on the anti-β1 immunoblot was not possible because they have very similar masses of 36.30 and 36.26 kDa, respectively. The tet-induced expression of β1FLAG subunit increased total β1 subunit abundance about 2-fold compared with untreated cells even though β1E and β1MYC expression were reduced.

FIGURE 5.

β1FLAG overexpression causes a decrease in β1MYC and β1E subunit abundance in MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC cells. MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC cells were grown in medium containing 1 μg/ml tet for 5 days (+) or grown in tet-free medium (−). Membrane-enriched fractions were harvested, and 5 μg of ER or PM protein was treated with PNGase F followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot detection. A, membranes were probed with anti-β-catenin, anti-α, anti-β, anti-MYC, or anti-FLAG antibodies. Signal intensities from anti-β1 (lower band) and anti-MYC immunoblots of the PM-enriched fraction were used to quantify β1E and β1MYC subunit abundance as a percentage of expression without tet (displayed in B).

The Extracellular Domain of Exogenous β1 Subunit Is Involved in Repressing Endogenous Subunit Abundance

To examine whether a specific region of overexpressed β1 is involved in down-regulating endogenous β1 subunits, we introduced one of two distinct epitope-tagged β1/β2 chimeras into the FRT site of MDCK cells. These constructs contain the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of either β1 or β2 fused to the extracellular domain of β2 or β1 as described in Fig. 6A. Because our previous report demonstrates that the β2 subunit does not assemble with the α1 subunit (33) and, as Fig. 1C demonstrates, its overexpression did not cause a reduction in β1 abundance, a decrease in β1E subunit abundance resulting from inducing chimera expression would be attributable to the domain(s) of the exogenous β1 subunit present in the chimera. Immunoblots of MDCK/β1/β2-MYC or MDCK/β2/β1-FLAG membrane-enriched fractions from cells grown in the presence or absence of tet for 6 days are shown in Fig. 6, B and C. In these immunoblots, the anti-β1 antibody recognized the β2/β1-FLAG but not the β1/β2-MYC chimera. Expression of the β1/β2-MYC chimera was induced when cells were treated with tet, and a significant portion of the β1/β2-MYC subunits was retained in the ER. The expression level of endogenous β1 subunit in ER- or PM-enriched fractions was not affected by β1/β2-MYC overexpression (Fig. 6B). Quantitation of β1E abundance in PM from Fig. 6B is displayed in Fig. 6D. The β2/β1-FLAG chimera, when induced with tet, was localized primarily at the plasma membrane. β2/β1-FLAG chimera overexpression resulted in a significant decrease in β1E subunit abundance (Fig. 6C). The abundance of endogenous β1 subunit (anti-β1 blot, lower band) after induction of β2/β1-FLAG (anti-β1 blot, upper band) was reduced by about 50% when compared with the normal β1 expression level (Fig. 6D). Neither of the chimeras, when expressed, caused a change in α1 abundance (Fig. 6, B or C, top panel).

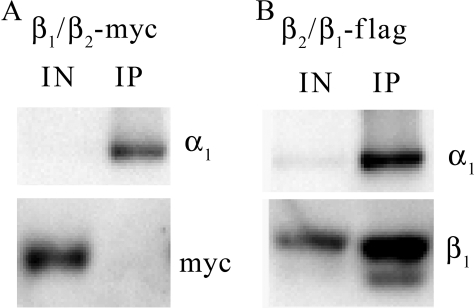

FIGURE 6.

Overexpression of β1/β2 chimeras have different effects on endogenous β1 subunit. A schematic representation of β1/β2-MYC and β2/β1-FLAG chimeras containing β1 (light gray) and β2 (dark gray) amino acid residues and FLAG or MYC epitope tags (gray box) is displayed in A. Both chimeras contain a short cytoplasmic amino terminus, single transmembrane segment, and long extracellular domain. MDCK/β1/β2-MYC or MDCK/β2/β1-FLAG cells were tet-treated for 6 days or left untreated prior to collecting ER- and PM-enriched fractions. Equal amounts of protein were treated with PNGase F, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blot. MDCK/β1/β2-MYC samples were probed with anti-α1, anti-actin, anti-β1, or anti-MYC antibodies (B). MDCK/β2/β1-FLAG samples were probed with anti-α1, anti-actin, anti-β1, or anti-FLAG antibodies (C). Quantitation of endogenous β1 subunit abundance from the PM-enriched fraction was corrected for loading by anti-actin and is displayed in D as a percentage of β1E from untreated samples.

The ability of the β1/β2 chimeras to assemble with α subunit is addressed in Fig. 7. MDCK/β1/β2-MYC or MDCK/β2/β1-FLAG cells were grown with tet for 72 h prior to harvesting cell lysates and anti-α loop immunoprecipitation. The overexpressed β1/β2-MYC chimera did not associate with α1subunit at detectable levels (Fig. 7A); however, the α subunit did co-precipitate β2/β1-FLAG chimeras (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

β2/β1-FLAG chimera assembles with α1 subunit, but β1/β2-MYC does not. 30 μg of total cell lysate from MDCK cells expressing either β1/β2-MYC (A) or β2/β1-FLAG (B) chimeras was collected and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-α loop antibody. Precipitated proteins were treated with PNGase F to deglycosylate all N-linked glycans. 10% of the initial lysate input (IN) and anti-α loop precipitated proteins (IP) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot probed with anti-α1, anti-MYC, and/or anti-β1 antibodies.

Translational Repression of Endogenous β1 in HEK Cells

To test whether the down-regulated expression of endogenous β1 subunit occurs in other cell types that overexpress exogenous β1FLAG subunit, we created an HEK293 FlpIn cell line that has the β1FLAG gene transfected into the cell FRT site. These HEK/β1FLAG cells showed the same β1FLAG and β1E subunit expression characteristics as observed in MDCK/β1FLAG cells, including the decrease in β1E subunits after tet addition to the growth medium (data not shown). The mRNA changes of β1E, α1, and β1FLAG that occurred following tet addition to HEK/β1FLAG growth medium were determined using qPCR and are shown in Table 2. Primer sets used for the amplification of cDNA in qPCR experiments (described in Table 1) were designed to specifically amplify endogenous α1, β1, or β-actin of human origin or exogenous β1FLAG of sheep origin. The change of β1FLAG mRNA was 46.40 ± 13.33-fold indicating that β1FLAG mRNA was increased significantly after tet addition compared with trace levels in no-tet samples. α1 and β1E mRNA were not significantly affected by the addition of tet to the growth medium (changes of 1.13 ± 0.28- and 1.22 ± 0.23-fold, respectively).

Regulation of α1 Subunit Abundance

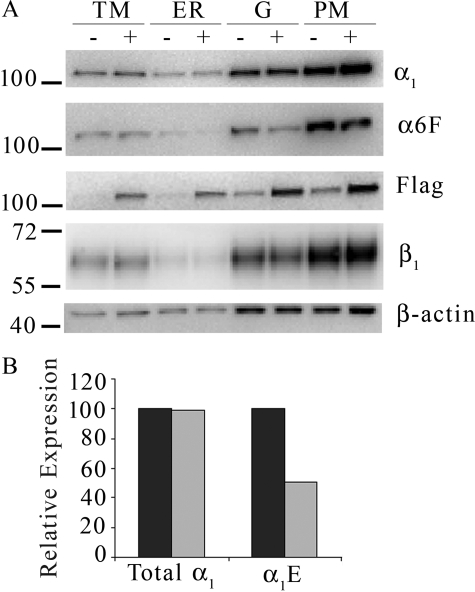

Because we had observed regulation of β subunit abundance in MDCK cells, an immediate question arose as to whether or not the sodium pump α subunit was under similar regulation. MDCK cells with α1FLAG integrated into the FRT site (MDCK/α1FLAG) were grown in the presence or absence of tet for 3 days to determine whether α1FLAG is expressed and distributed similarly to endogenous α1 (α1E) subunit. Western blots of membrane-enriched fractions in Fig. 8A show that the α1E and α1FLAG subunits are located primarily in the PM- and Golgi-enriched fractions as determined by anti-α6F and anti-FLAG antibodies, respectively. The anti-FLAG antibody blot demonstrates that exogenous α1FLAG was efficiently translated into protein when the cells were grown with tet. The blot probed with anti-α6F antibody to detect only the α1E subunits showed a marked decrease in tet samples. Interestingly the anti-α blot shows that total α1 expression levels, including both α1E and α1FLAG, remained unchanged when α1FLAG was expressed. Anti-α6F and anti-α antibody signal intensities from PM were quantified and are displayed in Fig. 8B. Clearly the total α subunit abundance remained unchanged; the level of the endogenous subunit decreased and compensated for the increase in heterologous α subunit expression.

FIGURE 8.

Overexpression of α1FLAG lowers α1E abundance without changing total α1 levels. MDCK/α1FLAG cells were grown with (+) or without (−) tet for 3 days prior to harvesting TM-, ER-, Golgi (G)-, and PM-enriched fractions and analyzing by Western blot. Immunoblots were probed with anti-FLAG, anti-α, anti-α6F, anti-β, and anti-β-actin antibodies (A), and relative expression levels of total α1 and α1E from −tet (dark bars) or +tet (light bars) PM-enriched samples were quantified (B).

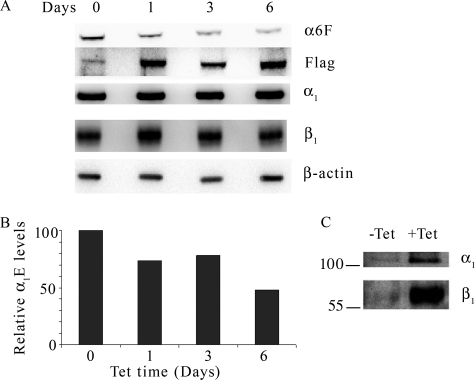

To determine whether the duration of induction affects the amount of α1FLAG and/or α1E expression, cells were grown in tet for 0, 1, 3, or 6 days, and subunit protein expression was analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 9A). The amount of total α and β expression was unchanged by the duration of tet treatment. α1FLAG expression increased over time. The Western blot probed with anti-α6F antibody shows that α1E abundance decreased over tet treatment time, falling to about 50% in 6 days. Quantitation of endogenous α subunit abundance is shown in Fig. 9B.

FIGURE 9.

α1E abundance decreases as α1FLAG expression increases. MDCK/α1FLAG cells were grown in the presence of tet for 0, 1, 3, or 6 days prior to harvesting total membranes. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were analyzed by Western blot using anti-β-actin, anti-α6F, anti-FLAG, anti-α1, and anti-β1 antibodies (A). α1E subunit abundance was quantified from the anti-α6F immunoblot and is displayed in B as a percentage of α1E abundance from 0-h tet samples. C, 20 μg of total membrane protein from MDCK/α1FLAG cells grown for 3 days with (+) or without (−) tet was subjected to anti-FLAG antibody IP. α1FLAG and β1 subunits were detected by Western blot analysis using anti-α1 and anti-β1 antibodies.

The association of α and β subunits is vital to having functional pump activity and basolateral localization in MDCK cells. To establish whether α1FLAG/β1 interactions occur when α1FLAG expression is induced, anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation was performed on total membranes from MDCK/α1FLAG cells grown with or without tet for 3 days. Western blots of immunoprecipitated proteins were probed with anti-α1 or anti-β antibodies and demonstrated that α1FLAG subunits are associated with β1 subunits (Fig. 9C).

mRNA Levels of Endogenous α1 Are Unaltered by α1FLAG Induction

To determine whether the reduction in α1E subunit abundance during α1FLAG expression is due to transcriptional changes, we performed quantitative PCR on mRNA- derived cDNA from MDCK/α1FLAG cells grown for 3 days with or without tet using species-specific primer sets to amplify either canine α1, β1, or β-actin cDNA or to amplify sheep β1FLAG cDNA (Table 1). Table 2 shows that although α1FLAG mRNA increased significantly after tet addition compared with trace amounts in tet-untreated cells the α1E and β1 mRNA levels were unaltered (changes of 1.04 ± 0.26- and 1.15 ± 0.39-fold, respectively). This suggests that the regulation of the α subunit abundance shares a common mechanism with the regulation of the β subunit we have reported here.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we demonstrated for the first time that when β1 subunits were overexpressed in MDCK cells and the total β1 level was increased by about 200% a significant decrease in the abundance of endogenous β1 subunit was observed. These changes took place without affecting α1 subunit levels. They occurred without significant effect on mRNA stability or on the degradation rate of β subunits. We thus propose that the β subunit abundance is under regulation of a mechanism that is post-transcriptional and involves repression of translation. We were able to expose this regulatory mechanism by the use of a robust overexpression system that was induced by the addition of tet to the growth medium. A similar regulatory mechanism could be seen acting on α subunit levels, but in this case the regulation seemed to be tighter, and total α subunit levels remained constant as expression of exogenous α1 subunits was compensated for by repression of the endogenous α subunit.

Specificity of Regulation

The extent of exogenous overexpression and subsequent decrease of endogenous subunit is dependent on time and concentration of tetracycline in the medium (Fig. 3). The factors involved in decreasing the abundance of β1E are specific to β1 isoform overexpression and do not occur when proteins unrelated to the sodium pump are overproduced. The addition of tetracycline to induce expression of hCTR1 protein (the human high affinity copper transporter) at the plasma membrane of the MDCK cells did not alter the abundance of Na,K-ATPase subunits (38). Additionally the overexpression of the sodium pump β2 isoform, which has 38% identity to β1 subunit, did not alter endogenous β1 subunit levels (Fig. 1C). This suggests that the mechanism governing the decrease in β1E synthesis acts specifically in response to the overexpression of β1 isoform. Other examples of isoform-specific effects in studies of sodium pump subunit abundance have been described. In heterozygous knock-out α1 mouse hearts that have reduced α1 subunit expression, a compensatory increase in α2 expression occurs. Conversely heterozygous α2 hearts with reduced α2 expression do not exhibit changes in α1 levels (39). In β2/β1 knock-in mice where the β2 gene is replaced by the β1 gene, β1 expression abolished the lethal phenotype observed in β2-deficient mice (40). However, β2-deficient mice without β1 knock-in do not exhibit enhanced β1 expression. These reports, in addition to the results described in this work, support the proposal that sodium pump isoforms may have distinct pathways of regulation. Studies using HEK293 cells, a fibroblast-like cell line, also exhibited the down-regulation of endogenous β1 subunit during β1FLAG overexpression demonstrating that the repression is a phenomenon that extends beyond polarized epithelial cells and may be present in a variety of cell types.

The ability of our MDCK cell lines to synthesize robust quantities of exogenous protein allowed us the unique opportunity to characterize regulatory mechanisms that would otherwise be difficult to identify. Although α1FLAG subunits were expressed primarily at the plasma membrane and associated with β1 subunits, the endogenous α subunit was down-regulated to the same extent that exogenous α1FLAG was expressed, resulting in no change of total α subunit abundance (Figs. 8 and 9). Furthermore the increase of α1FLAG was proportional to the decrease of α1E; even after 6 days the total abundance of α1 was unchanged (Fig. 9). Transcriptional regulation also did not contribute to α1E reduction because the mRNA levels of endogenous α1 were relatively unchanged by α1FLAG overexpression (Table 2). This implies that α1 expression is tightly regulated at the translational level possibly through mechanisms that also control endogenous β subunit expression (see below).

Transcription and Protein Degradation Do Not Play a Role

Given the ability to down-regulate β1E and β1MYC protein abundance while maintaining α1, β1FLAG, and unrelated protein abundance when exogenous β1 was overexpressed, the cellular mechanism regulating expression must be gene- or protein-specific. In most cell systems, alterations in protein abundance is achieved through changes involving transcription, translation, degradation, protein folding, post-translational modifications, and/or interactions with other proteins (41). In β1FLAG-overexpressing cells, the down-regulation of β1E is not likely due to post-translational events including 1) increased degradation because the rate of decrease in β1E abundance during β1FLAG expression was the same as the degradation rate determined by cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 4), 2) improper folding of sodium pump subunits or a lack of post-translational modifications because β subunits become fully glycosylated and assemble with α subunits (32), and 3) retention by an ER-resident protein because most β subunits were localized to the plasma membrane (Figs. 1A and 5A). The significant reduction in the β1E protein level during overexpression is also not regulated by transcriptional mechanisms because β1E mRNA levels were unaltered by the overexpression of β1FLAG (Table 2). Our work provides evidence that the down-regulation of endogenous β1 abundance occurs during translation. Translational regulation has been reported in a previous study in which viral recombinants containing the Na,K-ATPase α and β isoforms were infected into MDCK cells, and although both α1 and β1 mRNAs were present at high levels, neither subunit was efficiently translated (42).

Polypeptide Coding Sequence Is Involved in the Regulation

The α1 and β1 subunits of sodium pump found in MDCK cells (21) or enzyme purified from dog kidney (43, 44) are expressed at an equal ratio and form into α/β heterodimers. To maintain equimolar ratios the cells must possess mechanisms that regulate subunit abundance. Because the α1 and β1 genes are located on different chromosomes and their expression is not mediated by a common cis-acting regulatory element (42, 45), they may have discrete pathways for regulation. Interestingly although the α1 and β1 subunits are maintained at equal concentrations, their mRNA levels often vary (46, 47). The fluctuation of α or β mRNA abundance does not directly alter the protein synthesis rate, therefore post-transcriptional regulation of Na,K-ATPase subunits has been suggested (47).

One way in which post-transcriptional mechanisms regulate subunit expression is via the UTRs of the gene. The untranslated regions of sodium pump isoform mRNAs are known to contain important information that can either enhance or repress translation. In a previous report, the presence of the α1 subunit 5′-UTR reduced the translation efficiency of α1 subunit compared with a truncated version of the gene. The same sequence encoding α subunit 5′-UTR, when added upstream to the β1 coding region, also reduced β1 subunit translation efficiency (48). The UTRs of β subunit also contain regulatory elements that affect the translation efficiency of β subunit mRNA. In vitro translation assays determined that the length of the 3′-UTR segment of β1 mRNA is inversely proportional to the translation efficiency possibly due to the presence of a protein-binding region in the UTR (49) and/or a regulating region located between the second and fifth poly(A) signals (50). Additionally microRNAs have recently been found to be common regulators of translation, and by acting on 3′-UTRs of mRNAs they increase mRNA degradation and subsequently reduce protein abundance (51, 52). Although the UTRs may be important in repressing the translation efficiency of sodium pump subunits in certain cases, they do not account for the observed repression in MDCK/β1FLAG/β1MYC cells. In these cells, the tet-regulated β1FLAG and constitutively expressed β1MYC both contain cDNA derived from sheep β1 coding regions lacking β1 UTRs and that are under the control of cytomegalovirus promoters. Therefore the decrease in β1MYC abundance caused by β1FLAG overexpression (Fig. 5) is not due to factors involving the mRNA UTRs or regions of the promoter.

Translational Repression of Eukaryotic Membrane Proteins

The decrease of endogenous sodium pump subunit abundance caused by exogenous overexpression has not previously been described, although translational repression has been reported for another membrane-associated protein. A study focusing on tubulin expression demonstrated that the exogenous expression of α-tubulin in Chinese hamster ovary cells caused a reduction in the abundance of endogenous α-tubulin but not β-tubulin, preserving their equimolar ratio (53). The observed down-regulation of α-tubulin is caused by a post-transcriptional mechanism and is not an effect of increased degradation of mRNA or protein, which does occur when β-tubulin is overexpressed (54). It was suggested that the overexpressed α-tubulin protein inhibits its own mRNA likely via regulatory elements in the mRNA 5′-UTR. The repression is reversible by the removal of the α-tubulin from its mRNA that is likely achieved by the binding of β-tubulin to the α-tubulin protein. Thus, when β-tubulin protein is present and available for assembly with α-tubulin protein, the α-tubulin protein releases α-tubulin mRNA, allowing translation to proceed. The regulation via this postulated autofeedback loop, describing a protein binding to its own mRNA thereby inhibiting translation initiation, is a unique and interesting explanation for the down-regulation of endogenous protein synthesis during exogenous overexpression. However, as described above, the translational regulation of sodium pump reported here does not involve elements in the mRNA UTR.

Another mode of translational regulation, referred to as feedback regulation, occurs when iron regulatory proteins (IRP) bind to the iron-responsive elements (IREs) on UTRs of mRNAs that code for iron metabolism proteins (55). The iron export protein ferroportin (FPN) usually contains an IRE in its 5′-UTR, and under iron-deficient conditions, its translation is repressed in a coordinated effort to sustain cytosolic iron levels (56). However, in duodenal and erythroid precursor cells, iron deficiency does not repress FPN1 protein translation even though other IRP-sensitive genes are affected, including divalent metal transporter 1 and transferrin receptor 1 (57). Apparently the FPN1 contains one of two possible promoters depending on the tissue in which it is expressed. One of the promoters does contain IREs that regulates translation, and the other does not inhibit translation because it does not contain the known IREs. The failure to down-regulate FPN1, via IRP1/IRP2, in tissue of the small intestine during iron depletion results in a more stable systemic iron environment. Again this form of translational regulation, in contrast to the present work, occurs through the mRNA UTR.

If either the autoregulation or feedback regulation involving protein interacting with its cognate mRNAs described for α-tubulin or IRE/IRP-sensitive genes is applicable to the down-regulation of β1E in our β1FLAG-overexpressing cells, it is reasonable to assume that the excess β1FLAG subunit must bind to the coding region of the repressed β1 mRNA as β1MYC synthesis is down-regulated and its mRNA does not contain native β UTRs. It is also likely that the region of β1 subunit capable of interacting with mRNA and inhibiting initiation is the amino terminus that resides in the cytosol. If the cytosolic side of β1 subunit is the region capable of binding mRNA, then expression of the β1/β2-MYC chimera but not the β2/β1-FLAG chimera would cause down-regulation of β1E. Expression of either chimera in MDCK cells showed that the extracellular side of β1 is necessary to reduce β1E abundance. The amino terminus and transmembrane domain of β1 had no effect on endogenous subunit abundance (Fig. 6). The critical region of the exogenous β1 is extracytoplasmic or in the lumen of the polysome. The chimera experiments suggest that β1 down-regulation occurs postinitiation possibly at the elongation stage of translation.

Summary

The regulation that we describe here is responsible for directing endogenous Na,K-ATPase subunit abundance, is isoform-specific, and is independent of transcription. We propose that the exogenous overexpression of either α or β subunit in MDCK cells stimulates the translational repression of the endogenous subunit, likely involving elongation during translation. However, the mechanisms acting on α1 subunit are more stringent than those that mediate β1 subunit expression. Identifying the mechanisms by which these cells regulate subunit abundance may lead to new techniques for controlling protein abundance and sodium pump activity in a variety of cell types. We are currently investigating the processes of translation to determine the stage at which regulation occurs and cellular components involved in the repression.

Acknowledgments

The α6F antibody developed by Douglas M. Fambrough and the JLA20 antibody developed by Jim Jung-Ching Lin were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD, National Institutes of Health and maintained by Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-39500.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- tet

- tetracycline

- FRT

- Flp recombination target

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- TM

- total membrane

- PM

- plasma membrane

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- PNGase F

- peptide N-glycosidase F

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- β1E

- endogenous β1

- α1E

- endogenous α1

- UTR

- untranslated region

- IRP

- iron regulatory protein

- IRE

- iron-responsive element

- FPN

- ferroportin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan J. H. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71,511–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Therien A. G., Blostein R. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279,C541–C566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweadner K. J. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254,6060–6067 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco G., Mercer R. W. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 275,F633–F650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Y. K., Kaplan J. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275,19185–19191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohtsubo M., Noguchi S., Takeda K., Morohashi M., Kawamura M. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1021,157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morth J. P., Pedersen B. P., Toustrup-Jensen M. S., Sørensen T. L., Petersen J., Andersen J. P., Vilsen B., Nissen P. (2007) Nature 450,1043–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyoshima C., Nakasako M., Nomura H., Ogawa H. (2000) Nature 405,647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutsenko S., Kaplan J. H. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269,4555–4564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Béguin P., Hasler U., Staub O., Geering K. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11,1657–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pontiggia L., Gloor S. M. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 231,755–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laughery M. D., Todd M. L., Kaplan J. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278,34794–34803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatto C., McLoud S. M., Kaplan J. H. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281,C982–C992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farley R. A., Miller R. P., Kudrow A. (1986) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 873,136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller R. P., Farley R. A. (1988) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 954,50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beggah A. T., Jaunin P., Geering K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272,10318–10326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vagin O., Tokhtaeva E., Sachs G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281,39573–39587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoshani L., Contreras R. G., Roldán M. L., Moreno J., Lázaro A., Balda M. S., Matter K., Cereijido M. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16,1071–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutsenko S., Kaplan J. H. (1993) Biochemistry 32,6737–6743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caplan M. J., Anderson H. C., Palade G. E., Jamieson J. D. (1986) Cell 46,623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mircheff A. K., Bowen J. W., Yiu S. C., McDonough A. A. (1992) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 262,C470–C483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang M. J., McDonough A. A. (1992) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 263,C436–C442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen J. W., McDonough A. (1987) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 252,C179–C189 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G., Kawakami K., Gick G. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 294,73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wendt C. H., Towle H., Sharma R., Duvick S., Kawakami K., Gick G., Ingbar D. H. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 274,C356–C364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendt C. H., Gick G., Sharma R., Zhuang Y., Deng W., Ingbar D. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275,41396–41404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris Z. L., Ridge K. M., Gonzalez-Flecha B., Gottlieb L., Zucker A., Sznajder J. I. (1996) Eur. Respir. J. 9,472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barwe S. P., Kim S., Rajasekaran S. A., Bowie J. U., Rajasekaran A. K. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 365,706–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajasekaran S. A., Palmer L. G., Quan K., Harper J. F., Ball W. J., Jr., Bander N. H., PeraltaSoler A., Rajasekaran A. K. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12,279–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickey C. A., Gordon M. N., Mason J. E., Wilson N. J., Diamond D. M., Guzowski J. F., Morgan D. (2004) J. Neurochem. 88,434–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickey C. A., Gordon M. N., Wilcock D. M., Herber D. L., Freeman M. J., Morgan D. (2005) BMC Neurosci. 6,7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clifford R. J., Kaplan J. H. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295,F1314–F1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laughery M. D., Clifford R. J., Chi Y., Kaplan J. H. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292,F1718–F1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang B., van Hoek A. N., Verkman A. S. (1997) Biochemistry 36,7625–7632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatto C., Wang A. X., Kaplan J. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273,10578–10585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caplan M. J., Palade G. E., Jamieson J. D. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261,2860–2865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Methods 25,402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maryon E. B., Molloy S. A., Kaplan J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282,20376–20387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James P. F., Grupp I. L., Grupp G., Woo A. L., Askew G. R., Croyle M. L., Walsh R. A., Lingrel J. B. (1999) Mol. Cell 3,555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber P., Bartsch U., Schachner M., Montag D. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18,9192–9203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You L., Yin J. (2000) Metab. Eng. 2,210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grindstaff K. K., Blanco G., Mercer R. W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271,23211–23221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi Y., Takagi T., Maezawa S., Matsui H. (1983) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 748,153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyte J. (1971) J. Biol. Chem. 246,4157–4165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang-Feng T. L., Schneider J. W., Lindgren V., Shull M. M., Benz E. J., Jr., Lingrel J. B., Francke U. (1988) Genomics 2,128–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz A., Bhat S. P., Bok D. (1995) Gene 155,179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corthesy-Theulaz I., Merillat A. M., Honegger P., Rossier B. C. (1991) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 261,C124–C131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devarajan P., Gilmore-Hebert M., Benz E. J., Jr. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267,22435–22439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shao Y., Ismail-Beigi F. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286,C580–C585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shao Y., Ismail-Beigi F. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 390,78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai E. C. (2002) Nat. Genet. 30,363–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee R. C., Feinbaum R. L., Ambros V. (1993) Cell 75,843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonzalez-Garay M. L., Cabral F. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135,1525–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Theodorakis N. G., Cleveland D. W. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12,791–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henderson B. R., Menotti E., Kühn L. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271,4900–4908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abboud S., Haile D. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275,19906–19912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang D. L., Hughes R. M., Ollivierre-Wilson H., Ghosh M. C., Rouault T. A. (2009) Cell Metab. 9,461–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]