Abstract

Activation of the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B (5-HT2B), a Gq/11 protein-coupled receptor, results in proliferation of various cell types. The 5-HT2B receptor is also expressed on the pacemaker cells of the gastrointestinal tract, the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), where activation triggers ICC proliferation. The goal of this study was to characterize the mitogenic signal transduction cascade activated by the 5-HT2B receptor. All of the experiments were performed on mouse small intestine primary cell cultures. Activation of the 5-HT2B receptor by its agonist BW723C86 induced proliferation of ICC. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by LY294002 decreased base-line proliferation but had no effect on 5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation. Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor was inhibited by the phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 and by the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor inhibitor Xestospongin C. Calphostin C, the α, β, γ, and μ protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor Gö6976, and the α, β, γ, δ, and ζ PKC inhibitor Gö6983 inhibited 5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation, indicating the involvement of PKC α, β, or γ. Of all the PKC isoforms blocked by Gö6976, PKCγ and μ mRNAs were found by single-cell PCR to be expressed in ICC. 5-HT2B receptor activation in primary cell cultures obtained from PKCγ−/− mice did not result in a proliferative response, further indicating the requirement for PKCγ in the proliferative response to 5-HT2B receptor activation. The data demonstrate that the 5-HT2B receptor-induced proliferative response of ICC is through phospholipase C, [Ca2+]i, and PKCγ, implicating this PKC isoform in the regulation of cellular proliferation.

Tight control of cell proliferation is essential to maintain organ size and function. Proliferation needs to be tightly regulated to maintain a critical mass of a particular cell type while preventing dysplasia or malignancy. Cell proliferation is regulated by a complex interaction between extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors usually signal through cell surface receptors such as various growth factor receptors. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT,2 serotonin) is well established as a neurotransmitter and a paracrine factor with over 90% of 5-HT produced by the gastrointestinal tract (1, 2). There is now substantial evidence that, together with these established functions, 5-HT is involved in the control of cell proliferation through various 5-HT receptors, in particular the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B (5-HT2B (3–9)). The 5-HT2B receptor is Gq/11 protein-coupled. Activation of the 5-HT2B receptor regulates cardiac function, smooth muscle contractility, vascular physiology, and mood control. Recently it was demonstrated that activation of the 5-HT2B receptor also induces proliferation of neurons, retinal cells (3, 4), hepatocytes (5), osteoblasts (8), and interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) (9). ICC express the 5-HT2B receptor, and activation by 5-HT induces proliferation of ICC (9). ICC are specialized, mesoderm-derived mesenchymal cells in the gastrointestinal tract. Their best known function is the generation of slow waves (10), but they also conduct and amplify neuronal signals (11, 12), release carbon monoxide to set the intestinal smooth muscle membrane potential gradient (13), and act as mechanosensors (14, 15). Loss of ICC has been associated with pathological conditions such as gastroparesis (16–18), infantile pyloric stenosis (19, 20), pseudo-obstruction (21, 22), and slow transit constipation (23), whereas increased proliferation of ICC or their precursors is associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (24).

The mechanisms by which activation of the 5-HT2B receptor results in increased proliferation are not well understood. In cultured cardiomyocytes, stimulation of the 5-HT2B receptor activated both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3′-K)/Akt and ERK1/2/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways to protect cardiomyocytes from apoptosis (25). On the other hand, the 5-HT2 subfamily of receptors are also known to couple to phospholipase C (PLC) (26–28).

The objective of this study was to utilize the known expression of the 5-HT2B receptor on ICC to determine whether proliferation through the 5-HT2B receptor required PI3′-K or PLC. This study demonstrates that proliferation mediated by the 5-HT2B receptor requires PLC, intracellular calcium release, and the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway and identifies the PKC isoform activated by the 5-HT2B receptor in ICC as PKCγ.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

The mice were maintained and the experiments were performed with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic. BALB/c mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). PKCγ knock-out (PKCγ−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). 2–4-day-old mice were killed by CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation. The jejunum was quickly dissected out, flushed with ice-cold calcium-free Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen), and pinned onto a Sylgard-lined Petri dish, and the mucosa and mesentery were removed.

Reverse Transcription-PCR

To determine the expression of different PKC isoforms, PCR was performed on adult mouse jejunal muscle strip RNA. Adult mouse brain served as a positive control. Whole mouse brain was quickly dissected out on ice. Total RNA from jejunal muscle strips and brain was isolated using RNAbee (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using Gene Amp Gold RNA PCR reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Polymerase chain reaction for PKCα, β, γ, and μ message was performed on 50 ng of sample cDNA using 300 nmol/liter of gene-specific primers (supplemental Table S1) and AmpiTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Enzymatic Dissociation of ICC

To obtain freshly dispersed jejunal cells, muscle strips from three mice were pooled in a collagenase-based dissociation mixture. The mixture contained 2500 units of collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemical Company), 20 mg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 20 mg of trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), and 5 mg of adenosine triphosphate (Roche Applied Science) in 10 ml of calcium-free Hank's balanced salt solution. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 0.1 m NaOH. After 15 min of incubation at 32 °C in a gently shaken water bath, the tissue was triturated and spun down at 800 × g for 6 min. The cells were resuspended in 2 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen).

Mouse Interstitial Cells of Cajal and Fibroblast Co-cultures

Freshly dispersed cells obtained from the mouse small intestine were cultured on 22-mm glass coverslips covered with mouse fibroblasts as described before (29). These fibroblasts support ICC survival because of being genetically engineered to produce murine stem cell factor, the ligand for the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase protein expressed on ICC. Briefly, Sl/Sl4 mSCF248, murine stem cell factor secreting fibroblasts (provided by Dr. David Williams, Indianapolis), were plated on 22-mm human fibronectin-coated glass coverslips at 4.5 × 104 cells/coverslip in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (all from Invitrogen). After 30 h, fibroblast cell division was arrested by irradiation at 16,000 grays. After a 24-h recovery period, 250 μl of suspensions containing cells freshly dissociated from mouse jejunum were plated onto the Sl/Sl4 mSCF248 fibroblasts at a cell density of ∼3 × 105 cells/coverslip. The cells were allowed to sit for 30 min at 37 °C/5% CO2 before adding 2 ml of the culture medium to the well. These culture conditions result in cell cultures highly enriched in ICC.

Isolation of Single ICC

Single ICC were selected on the basis of detection of the ICC marker kit. This procedure was carried out on ice. Freshly dissociated cells were stained for Kit expression with the phycoerythrin-labeled anti-mouse CD117 (ACK2; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) diluted at 1:300 in flow cytometry staining buffer (eBioscience). The cells were incubated for 20 min in the dark on a shaker and washed three times with ice-cold staining buffer. Single ICC were selected based on the phycoerythrin-ACK2 immunolabeling and collected by gentle aspiration into a 30-μm-wide patch clamp pipette tip. Two to three cells were lifted out of the chamber and immediately expelled into a 200-μl tube on dry ice as described previously (30). For controls, two to three single cells not positive for phycoerythrin-ACK2 labeling were collected per tube.

Single-cell PCR

0.5 μg of yeast tRNA (Ambion, Austin, TX) and 10 μg of proteinase K (Roche Applied Science) were added per isolated cell. The sample was centrifuged at 3300 × g at 4 °C for 30 s to release RNA. Nucleases and proteinases were destroyed by incubation at 90 °C for 10 min, 55 °C for 30 min, and 90 °C for 10 min.

Two-step reverse transcription and PCR were performed using the TaqMan® Gold reverse transcription-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) as described by the manufacturer. 25-μl PCRs were set up by dividing all solutions by 2. 5 μl of the first PCR (94 °C for 5 min, 35 times 94 °C for 20 s, melting temp (Tm) for 20 s, 72 °C for extension time, and 72 °C for 10 min) was used for the nested PCR (94 °C for 5 min, 35 times 94 °C for 20 s, Tm for 20 s, 72 °C for extension time, and 72 °C for 10 min). The optimized PCR programs are reported in supplemental Table S1.

Drugs and Chemicals

BW723C86 was purchased from Tocris Cookson Inc. (Ellisville, MO); U73122 was from Invitrogen; U73343 was from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ); LY294002 was from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); calphostin C, Gö6976, and Gö6983 were from Calbiochem, 3-(2-aminoethyl)-5-((4-ethoxyphenyl)methylene)-2,4-thiazolidinedione hydrochloride (ERK inhibitor) was from Sigma-Aldrich; SB204741 was from Tocris Cookson Inc.; and Xestospongin C was from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI).

BW723C86 (100 mm), U73122 (10 mm), LY294002 (10 mm), calphostin C (1 mm), Xestospongin C (1 mm), U73343 (10 mm), SB204741 (100 mm), 3-(2-aminoethyl)-5-((4-ethoxyphenyl)methylene)-2,4-thiazolidinedione hydrochloride (25 mm), Gö6976 (10 mm), and Gö6983 (3 mm) stock solutions were made in Me2SO. Further dilutions were made fresh on the experimental day. All of the dilutions were maintained in solution using a 37 °C water bath. Primary cell cultures were treated at 1 h after plating and every 20 h with the compounds as indicated, for 2.5 days.

Data Analysis

All of the data analysis was carried out on the raw non-normalized data. For cell culture experiments, analysis of variance with a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons post test was done to compare groups of data. For experiments with two groups, Student's t test was used. All of the data are expressed as the means ± S.E., where n represents the number of experiments on individual dissociations.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical Staining of Primary Cell Cultures

Interstitial cells of Cajal were immunolabeled using the rat monoclonal anti-c-Kit antibody ACK2 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) as described previously (29). Briefly, acetone-fixed coverslips (4 °C, 10 min) were washed with PBS and incubated with 10% normal donkey serum (NDS; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 1 h to minimize nonspecific antibody binding followed by primary antibody (1/150, 120 μg/ml, in 5% NDS) incubation overnight at 4 °C. Next, the sections were rinsed in PBS.

Immunolabeling using a monoclonal antibody to Ki67 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) was used to identify proliferating cells. After the ACK2 staining procedure, the coverslips were post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed with PBS, and incubated with anti-Ki67 (2 μg/ml, in 5% NDS) for 4 h at room temperature. Next, the sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature with donkey anti-rat IgG conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories; 1.8 μg/ml in 2.5% NDS) and donkey anti-rabbit conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories; 7.5 μg/ml in 2.5% NDS).

Mounting and Analysis

Sections and immunostained cultures were mounted with Slow Fade Gold containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole from Invitrogen and examined using a fluorescence microscope. Immunostained cultures were examined for Kit-positive cells with the use of a fluorescent microscope (Olympus BX51WI; Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). A 20× (numeral aperture, 0.5) objective was used to count the number of Kit-positive cells/high power field. One field covered 0.94 mm2. At least 35 fields were counted per culture. Sampling from 35 fields was done because, based on previous studies, this sample size gives an accurate measure of the mean density of the cells and variation in the cell density.

RESULTS

Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B Receptor Is Mediated by Phospholipase C but Not by PI3′-K

The 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86 (50 nm) increased ICC numbers in culture in all experiments by an average of 35 ± 3.9% (mean ± S.E., n = 30 dissociations, p < 0.05, paired t test; Table 1) by activating proliferation of ICC as detected by Ki67 immunoreactivity (mean increase ± S.E. = 28.5 ± 3.8%, n = 30 dissociations, p < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 1). BW723C86 appeared to specifically activate 5-HT2B receptors because, in the presence of a selective 5-HT2B receptor antagonist SB204741, there was no proliferative response with the addition of BW723C86 (control, 16.0 ± 1.1% proliferating ICC; 50 nm BW, 24.4 ± 1.2%; n = 4, p < 0.05; 2 nm SB204741, 14.7 ± 1.5%, 2 nm SB204741 + 50 nm BW, 14.2 ± 1.0%, n = 4; p > 0.05 by analysis of variance with post test). The effect of the PI3′-K inhibitor LY294002 on the proliferative effect of activation of the 5-HT2B receptor was assayed. In the presence of 1 and 10 μm LY294002, base-line proliferation of ICC was reduced (Fig. 2A). However, inhibition of PI3′-K did not affect increased proliferation of ICC by BW723C86 (Fig. 2A), indicating that proliferation through the 5-HT2B receptor is PI3′-K-independent.

TABLE 1.

Treatment of primary cultures of ICC with the 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86 (50 nm) resulted in a significant increase in the number of ICC (p < 0.05, paired t test)

The data are the numbers of cells/field from 30 experiments on separate dissociations.

| Control | 50 nm BW723C86 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean cells/field | 7.70 | 10.40 |

| S.E. | 0.67 | 1.06 |

FIGURE 1.

The 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86 increases proliferation. The 5-HT2B agonist BW723C86 (50 nm) increased the number of proliferating ICC. Control, 18.6 ± 0.7%; 50 nm BW, 23.9 ± 1.3%. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p < 0.05 by paired t test (n = 30).

FIGURE 2.

Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor did not require PI3′-K but was dependent upon PLC. A, addition of the PI3′-K inhibitor LY294002 (1 and 10 μm) decreased base-line proliferation of ICC. However, in the presence of LY294002 (1 and 10 μm), activation of the 5-HT2B receptor by BW723C86 still increased proliferation of ICC. Control, 17.2 ± 2.1%; 50 nm BW, 20.5 ± 2.7%; 1 μm LY294002, 11.0 ± 2.0%; 1 μm LY294002 + 50 nm BW, 16.8 ± 2.8%; 10 μm LY294002, 3.6 ± 1.5%; 10 μm LY294002 + 50 nm BW, 11.6 ± 3.4%. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p < 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (n = 6). B, U73122 (1 and 10 μm) did not affect base-line proliferation. However, in the presence of 1 and 10 μm U73122, there was no proliferative response to BW723C86. Control, 19.8 ± 1.4%; 50 nm BW, 29.6 ± 4.4%; 1 μm U73122, 24.3 ± 5.0%; 1 μm U73122 + 50 nm BW, 21.7 ± 2.4%; 10 μm U73122, 16.6 ± 1.3%; 10 μm U73122 + 50 nm BW, 18.6 ± 2.0%. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p < 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (n = 6).

Base-line proliferation of ICC in culture was not affected by the PLC inhibitor U73122 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the proliferative response of ICC to 5-HT2B receptor activation was completely blocked by the U73122 (Fig. 2B), indicating that proliferation mediated by activation of the 5-HT2B receptor requires PLC. U73343, the inactive analogue of U73122, did not block the proliferative response to BW723C86 (control, 16.0 ± 1.1% proliferating ICC; 50 nm BW, 24.4 ± 1.2%, n = 4, mean ± S.E., p < 0.05; 1 μm U73343, 15.6 ± 1.3%, 1 μm U73343 + 50 nm BW, 22.6 ± 0.8%, n = 4, mean ± S.E., p < 0.05 by Tukey Kramer multiple comparisons test).

Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B Receptor Is Dependent upon Intracellular Calcium Release

Activation of phospholipase C mediates generation of diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, resulting in intracellular calcium release through opening of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channels. To test whether the proliferative effect of 5-HT2B receptor activation requires intracellular calcium release, the effect of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor antagonist Xestospongin C (31) on proliferation was assayed.

Xestospongin C had no effect on base-line proliferation of ICC (Fig. 3A). Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor was completely inhibited by 333 nm and 1 μm Xestospongin C (Fig. 3A). 5-HT2B receptor activation in ICC increased intracellular Ca2+ (supplemental Fig. S1), and 5-HT2B receptor-mediated responses were abolished in the presence of Xestospongin C (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 3.

The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor inhibitor Xestospongin C and the nonspecific PKC inhibitor calphostin C inhibited the proliferative effect of BW723C86 on ICC. A, 333 nm and 1 μm Xestospongin (Xesto) C inhibited the increase in proliferation of ICC induced by BW723C86. Control, 22.0 ± 1.0%; 50 nm BW, 27.2 ± 1.6; 333 nm Xestospongin C, 24.6 ± 0.8; 333 nm Xestospongin C + 50 nm BW, 27.1 ± 1.7%; 1 μm Xestospongin C, 22.9 ± 1.8%; 1 μm Xestospongin C + 50 nm BW, 19.9 ± 0.8%. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p < 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (n = 6). B, 50 nm calphostin (Calph) partly inhibited the proliferative response by BW723C86, whereas 150 nm completely prevented the proliferative effect. Control, 21.6 ± 2.5; 50 nm BW, 25.2 ± 2.9; 50 nm calphostin C, 21.6 ± 2.2; 50 nm calphostin C + 50 nm BW, 24.1 ± 3.7; 150 nm calphostin C, 21.0 ± 1.9; 150 nm calphostin C + 50 nm BW, 20.7 ± 2.4. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p < 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (n = 6).

A Calcium-dependent Protein Kinase C Is Required for Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B Receptor

To examine whether the proliferative effect of the 5-HT2B receptor is mediated by protein kinase C, cells were treated with calphostin C, a nonspecific PKC inhibitor that inhibits all PKC isoforms except for PKCμ. In the presence of calphostin C, base-line proliferation of ICC was unchanged (Fig. 3B). In contrast, proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor was dose-dependently inhibited by 50 and 150 nm calphostin C (Fig. 3B). These data show that activation of a PKC is required for the proliferative effects of the 5-HT2B receptor and that the isoform involved is not PKCμ.

Next we studied the effect of the more specific PKC inhibitors Gö6976 and Gö6983. In the presence of the α, β, γ, and μ PKC inhibitor Gö6976 (100 nm), base-line proliferation of ICC was reduced (Fig. 4A). The proliferative response of ICC to BW723C86 was inhibited by Gö6976 (Fig. 4A). In contrast to Gö6976, the α, β, γ, δ, and ζ PKC inhibitor Gö6983 (30 and 100 nm), which does not inhibit PKCμ (IC50 = 20,000 nm), did not change base-line proliferation of ICC (Fig. 4B). Proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor was inhibited by Gö6983 (Fig. 4B). Taken together, the PKC inhibitor data indicate that 5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation requires a calcium-dependent conventional PKC. The data also demonstrate that PKCμ is involved in non-5-HT2B-mediated proliferation of ICC.

FIGURE 4.

The isoform specific protein kinase C antagonists Gö6976 and Gö6983 inhibited the increase in proliferation of ICC induced by BW723C86. A, the PKCα, β, γ, and μ inhibitor Gö6976 decreased base-line proliferation of ICC. Increased proliferation by adding BW723C86 was completely inhibited in the presence of 100 nm Gö6976. Control, 16.4 ± 0.82; 50 nm BW, 21.1 ± 0.56; 100 nm Gö6976, 13.6 ± 0.68; 100 nm Gö6976 + 50 nm BW, 15 ± 0.84; n = 8, p < 0.05. B, the PKCα, β, γ, and δ inhibitor Gö6983 had no effect on base-line proliferation of ICC. 30 and 100 nm Gö6983 fully inhibited the proliferative response by BW723C86. Control, 16.9 ± 0.50; 50 nm BW, 21.9 ± 0.76; 30 nm Gö6983 15.5 ± 0.96, 30 nm Gö6983 + 50 nm BW, 15.8 ± 0.91; 100 nm Gö6983, 15.3 ± 0.78; 100 nm Gö6983 + 50 nm BW, 16.9 ± 1.26. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p > 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (n = 6).

Proliferation through the 5-HT2B Receptor Requires ERK/MAPK Activation

To test whether proliferation through the 5-HT2B receptor requires ERK/MAPK activation, primary cultures were treated with 25 μm of ERK inhibitor, which inhibits ERK binding. The proliferative response of ICC to 5-HT2B receptor activation was inhibited in the presence of the drug (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

ERK inhibitor inhibited the proliferative effect of BW723C86 on ICC. 25 μm of the drug inhibited the increase in proliferation of ICC induced by BW723C86. Control, 16 ± 1.1% proliferating ICC; 50 nm BW, 24.4 ± 1.2%, n = 4, p < 0.05; ERK inhibitor (25 μm), 16.6 ± 0.4%; ERK inhibitor (25 μm) + 50 nm BW, 16.0 ± 1.2% (n = 4). p > 0.05 by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E.

Single ICC Expressed Gö6976-sensitive PKC Isoforms γ and μ

Experiments were directed toward determining which calcium-dependent PKCs are expressed in the intestinal smooth muscle wall and whether PKCμ is also expressed. Mouse brain cDNA was used as a positive control. Using PCR, PKCα, β, γ, and μ mRNAs of the expected size, 414, 557, 528, and 426 nt, respectively, were amplified from total RNA of mouse brain and jejunal muscle strips (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

The calcium-dependent PKC isoforms, PKCα, β, and PKCμ mRNAs were expressed in adult mouse jejunum muscle strips. mRNAs of the expected length were amplified from brain and jejunal muscle strips for PKCα (A, 414 nt), β (B, 557 nt), γ (C, 528 nt), and μ (D, 426 nt). Ladders, DNA molecular weight marker XIV (Roche Applied Science).

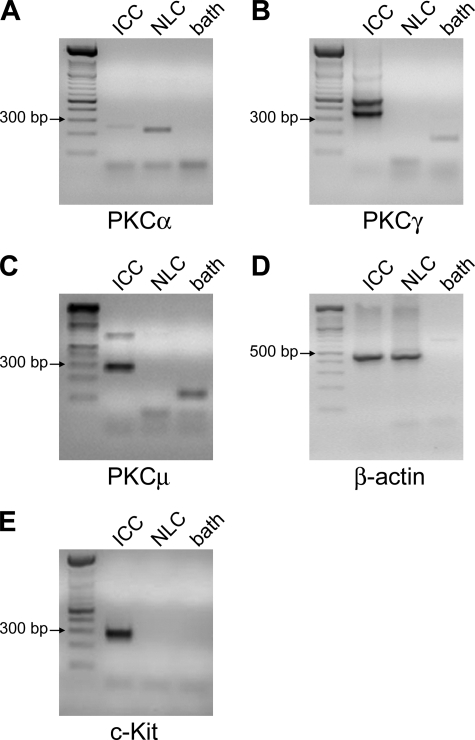

Next, nested PCR for PKCα, β, γ, and μ was performed on two or three single Kit-positive neonatal ICC and on two or three Kit-negative cells to identify the specific PKC isoforms expressed on ICC. mRNA for PKCα was amplified (223-nt product) from Kit-negative cells but not from ICC (Fig. 7A). mRNA for PKCβ could not be amplified from ICC nor from Kit-negative cells (data not shown). On the other hand, products of the expected length for PKCγ (334 and 528 nt; Fig. 7B) and PKCμ (248 nt; Fig. 7C) were amplified from mRNA extracted from ICC but not from Kit-negative cells. β-Actin mRNA was amplified (453 nt) from ICC and Kit-negative cells (Fig. 7D). As a control, a product of the expected length for Kit (285 nt; Fig. 7E) was amplified from mRNA isolated from ICC but not from Kit-negative cells. The identities of all bands were confirmed by sequencing. These data, taken with the PKC inhibitor data, suggest that 5-HT2B receptor signals through PKCγ.

FIGURE 7.

Single ICC expressed PKCγ and μ mRNAs. A, mRNA of the expected length was amplified from nonlabeled cells (NLC) for PKCα (223 nt). The faint band slightly above the expected size seen in the ICC lane was sequenced and was found to be nonspecific amplification. B and C, PKCγ (B, 334 and 528 nt) and μ (C, 248 nt) mRNAs were amplified from ICC but not from nonlabeled cells. D, β-actin mRNA was amplified from ICC and nonlabeled cells (453 nt). E, as a control, c-Kit mRNA was amplified from ICC but not from nonlabeled cells (285 nt). The identity of all amplification products was confirmed by sequencing. Ladders, DNA molecular weight marker XIV (Roche Applied Science).

The Proliferative Response of ICC by Activation of the 5-HT2B Receptor Is Absent in ICC Lacking PKCγ

To confirm the PKC inhibitor data, ICC cultures were obtained from PKCγ−/− mice. Activation of the 5-HT2B receptor by its agonist BW723C86 had no proliferative effect on ICC (Fig. 8). Functionality of the 5-HT2B receptor in the PKCγ−/− mice was confirmed by measuring contractility of jejunal circular muscle strips in response to the 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86. BW723C86 increased contractility in both PKCγ−/− and wild type tissue (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 8.

The proliferative response of ICC by activation of the 5-HT2B receptor is absent in PKCγ knock-out cultures. The 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86 (50 nm) did not increase proliferation in PKCγ−/− ICC. Control, 17.9 ± 1.1%; 50 nm BW, 15.0 ± 1.1%. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. p > 0.05 by paired t test (n = 4).

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence that activation of the 5-HT2B receptor increases proliferation through activation of PLC, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-mediated intracellular calcium release, activation of the calcium-dependent PKCγ, and ERK/MAPK activation.

The role of 5-HT in regulating gastrointestinal motility has been extensively studied. However, accumulating evidence, mostly from outside the gastrointestinal tract, shows that 5-HT can also regulate cell survival and proliferation. Four serotonin receptors have been implicated in transduction of the 5-HT signal to regulate cell survival and proliferation: 5-HT1A, 5-HT1D, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors. Activation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2C receptors results in increased numbers of newly formed neurons in rat brain (32–34), whereas 5-HT1A and 5-HT1D receptors regulate mitogenesis in human small cell carcinoma of the lung (35). 5-HT1A receptors are also involved in proliferation of T and B cells (36) and rat blood lymphocytes (37). A role for 5-HT2B receptors in cell differentiation and proliferation has been shown in various cell types and species including mouse enteric neurons, hepatocytes, mouse cardiomyocytes, and retinal cells in Xenopus (3–7, 38). We demonstrated previously that activation of the 5-HT2B receptor on murine ICC induces proliferation of ICC (9).

The 5-HT2B receptor is a Gq/11 protein-coupled receptor that can activate at least two mitogenic pathways including PI3′-K/Akt (25) and PLC (26–28). The effect of the PI3′-K inhibitor LY294002 and the PLC inhibitor U73122 on proliferation induced by activation of the 5-HT2B receptor was studied on primary ICC cultures. Although LY294002 dose-dependently decreased the percentage of base-line proliferating ICC, activation of the 5-HT2B receptor in the presence of LY294002 still increased ICC proliferation. These results demonstrate that proliferation of ICC through the 5-HT2B receptor is not dependent upon PI3′-K and that another signaling cascade, downstream of a so far unidentified receptor, induces proliferation of ICC through PI3′-K. Proliferation of ICC activated by BW723C86 was completely inhibited by U73122 and Xestospongin C, the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor inhibitor, and was therefore dependent upon PLC and intracellular Ca2+ release. In support of this observation, U73343, the inactive analogue of U73122, did not affect the proliferative response to BW723C86, and although both of these compounds do have some nonspecific effects, these observations are most consistent with their differential effects on PLC.

There are 11 reported isoforms of PKC classified in three subclasses. The conventional subclass, PKCα, β1, β2, and γ, requires Ca2+, diacylglycerol, and phospholipids for their activation, whereas novel PKCδ, ϵ, η, and θ are calcium-independent. The atypical PKC isoforms (PKCι, ζ, and μ, also known as protein kinase D1 in mouse) are independent of Ca2+ and diacylglycerol (39). PKCs are important regulators of cell proliferation. PKCα has been reported to increase cellular proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma (40) and goblet cells (41), whereas PKCθ regulates Kit expression and induces proliferation in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (42). Conversely, PKCβ and PKCδ down-regulate proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (43, 44), PKCδ also inhibits Caco-2 cell proliferation (45).

A role for PKCγ in mediating proliferation has not previously been established. Although neuronal PKCγ was implicated in the proliferation of astrocytes following repeated morphine administration in vivo, the mechanism of action was not studied (46). In contrast, overexpression of PKCγ reduced proliferation and resulted in differentiation of lens epithelial cells (47) and glioma cells (48), whereas mutations in PKCγ reduced its kinase activity, resulting in lower ERK phosphorylation and nuclear ERK translocation, reduced MAPK signaling, and reduced survival of Purkinje cells leading to spinocerebellar ataxia-14 (49). This is the first study demonstrating that 5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation is regulated by PKCγ.

Based on literature, ICC express various PKC isoforms including PKCγ (50, 51), PKCθ (50–52), and PKCϵ (53). In our hands, PKCα and PKCβ mRNAs were lacking in ICC, in line with Furness et al. (50). We confirmed the expression of PKCγ mRNA in ICC, as described in guinea pig (51) and human (50), and we demonstrated for the first time the expression of PKCμ mRNA in ICC.

The use of PKC inhibitors to determine specific PKC isoforms is fraught with difficulties because of the conflicting literature and the need to use correct drug concentrations based on the IC50 values of the different isoforms. We therefore used three different PKC inhibitors and confirmed our results in PKCγ−/− mice before concluding that the effects of 5-HT2B on proliferation are mediated through PKCγ. Calphostin C was used as a nonspecific PKC antagonist (inhibits all isoforms except for PKCμ). Gö6976 is used as a potent inhibitor of PKC α, β, and μ. However, 158 nm Gö6976 has been shown to inhibit all PKC activity in the brain (IC50 = 12.5 nm). PKC isoforms expressed in the brain include PKCα, βI, βII, and γ. Therefore PKCγ is also inhibited by Gö6976 in this concentration range, making Gö6976 an inhibitor of all the conventional PKCs and also of PKCμ (54–56). Gö6983 inhibits PKCα, β, γ, δ, and ξ at nanomolar range and PKCμ at 20 μm and can therefore be used to discriminate the role of PKCμ in the presence of other PKC isoforms (56). We found that calphostin C dose-dependently inhibited the proliferative effect of BW723C86 and had no effect on base-line proliferation. 100 nm Gö6976 and 30 and 100 nm Gö6983 fully inhibited proliferation of ICC induced by the 5-HT2B receptor agonist BW723C86, indicating that PKCα, β, and/or γ are required. Gö6976, which also inhibits PKCμ, decreased non-5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation as well. Based on these PKC inhibitor data and the fact that of the three possible isoforms only PKCγ mRNA was expressed in ICC, we concluded that 5-HT2B receptor-mediated proliferation was regulated by PKCγ. This result was confirmed in ICC obtained from PKCγ−/− mice, where activation of the 5-HT2B receptor did not result in a proliferative response despite the 5-HT2B receptor appearing to be functionally active. We found that base-line proliferation of ICC required PKCμ. It is known that overexpression of PKCμ activates MAPK (57) and inhibits the c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway (58, 59), thereby inducing cellular proliferation. PKCμ is also known to be activated by PI3′-K (60). Based on the experiments with LY294002 and the PKC inhibitor results, we can state that base-line proliferation of ICC likely requires PI3′-K and PKCμ, but the growth receptor(s) underlying this proliferative pathway remain unknown.

ICC are important regulators of gastrointestinal motility because they generate slow waves and determine the frequency of contractions, they act as amplifiers of neuronal signals and as mechanosensors, and they set the smooth muscle membrane potential gradient. A decreased number of ICC or a disrupted ICC network is associated with pathologic conditions such as slow transit constipation, diabetic gastroparesis, and pseudo-obstruction. Understanding the factors that underlie ICC survival and proliferation is important in determining how ICC networks are maintained and how to limit ICC loss or induce recovery in disease states associated with the loss of ICC. Recent observations indicate that turnover of ICC occurs in immature and adult ICC. We now know that there are several substances that help modulate ICC numbers in the gastrointestinal tract including a functional c-Kit-stem cell factor pathway (29), the insulin/insulin growth factor I signaling pathway (61), and cryoprotective molecules including nitric oxide (62) and heme-oxygenase 1 (16).

In summary, we showed that activation of the 5-HT2B receptor on ICC results in proliferation of ICC. This proliferative effect of the 5-HT2B receptor is mediated by activation of PLC, intracellular calcium release, and PKCγ.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Stoltz for tissue dissection, Dr. Arthur Beyder for help with figures, and Kristy Zodrow for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK52766 and DK57061.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

- 5-HT

- 5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin

- 5-HT2B

- 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B

- Gö6976

- 12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole

- Gö6983

- 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-5-methoxyindol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl) maleimide

- ICC

- interstitial cell(s) of Cajal

- PI3-K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular-regulated MAP kinase

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- ERK inhibitor

- 3-(2-Aminoethyl)-5-((4-ethoxyphenyl)methylene)-2,4-thiazolidinedione hydrochloride

- NDS

- normal donkey serum

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- nt

- nucleotide

- U73122

- 1-[6-[((17β)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5[10]-trien-17-yl)amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- BW or BW723C86

- α-methyl-5-(2-thienylmethoxy)-1H-indole-3-ethanamine hydrochloride

- U73343

- 1-[6-[((17β)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5[10]-trien-17-yl)amino]hexyl]-2,5-pyrrolidinedione

- SB204741

- N-(1-methyl-1H-indolyl-5-yl)-N[dprime]-(3-methyl-5-isothiazol yl)urea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertrand P. P. (2006) J. Physiol. 577, 689–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erspamer V. (1954) Pharmacol. Rev. 6, 425–487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Lucchini S., Ori M., Cremisi F., Nardini M., Nardi I. (2005) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 29, 299–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Lucchini S., Ori M., Nardini M., Marracci S., Nardi I. (2003) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 115, 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesurtel M., Graf R., Aleil B., Walther D. J., Tian Y., Jochum W., Gachet C., Bader M., Clavien P. A. (2006) Science 312, 104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nebigil C. G., Jaffré F., Messaddeq N., Hickel P., Monassier L., Launay J. M., Maroteaux L. (2003) Circulation 107, 3223–3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhasin N., LaMantia A. S., Lauder J. M. (2004) Anat. Embryol. 208, 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collet C., Schiltz C., Geoffroy V., Maroteaux L., Launay J. M., de Vernejoul M. C. (2008) FASEB J. 22, 418–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wouters M. M., Gibbons S. J., Roeder J. L., Distad M., Ou Y., Strege P. R., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2007) Gastroenterology 133, 897–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward S. M., Burns A. J., Torihashi S., Sanders K. M. (1994) J. Physiol. 480, 91–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iino S., Ward S. M., Sanders K. M. (2004) J. Physiol. 556, 521–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward S. M., Morris G., Reese L., Wang X. Y., Sanders K. M. (1998) Gastroenterology 115, 314–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2004) Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 16, 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strege P. R., Holm A. N., Rich A., Miller S. M., Ou Y., Sarr M. G., Farrugia G. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 284, C60–C66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thuneberg L., Peters S. (2001) Anat. Rec. 262, 110–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi K. M., Gibbons S. J., Nguyen T. V., Stoltz G. J., Lurken M. S., Ordog T., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2008) Gastroenterology 135, 2055–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster J., Damjanov I., Lin Z., Sarosiek I., Wetzel P., McCallum R. W. (2005) J. Gastrointest. Surg. 9, 102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zárate N., Mearin F., Wang X. Y., Hewlett B., Huizinga J. D., Malagelada J. R. (2003) Gut 52, 966–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer J. C., Berezin I., Daniel E. E. (1995) J. Pediatr. Surg. 30, 1535–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanderwinden J. M., Liu H., De Laet M. H., Vanderhaeghen J. J. (1996) Gastroenterology 111, 279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldstein A. E., Miller S. M., El-Youssef M., Rodeberg D., Lindor N. M., Burgart L. J., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2003) J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 36, 492–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenny S. E., Vanderwinden J. M., Rintala R. J., Connell M. G., Lloyd D. A., Vanderhaegen J. J., De Laet M. H. (1998) J. Pediatr. Surg. 33, 94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He C. L., Burgart L., Wang L., Pemberton J., Young-Fadok T., Szurszewski J., Farrugia G. (2000) Gastroenterology 118, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H., Hirota S., Isozaki K., Sun H., Ohashi A., Kinoshita K., O'Brien P., Kapusta L., Dardick I., Obayashi T., Okazaki T., Shinomura Y., Matsuzawa Y., Kitamura Y. (2002) Gut 51, 793–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nebigil C. G., Etienne N., Messaddeq N., Maroteaux L. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 1373–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julius D., Huang K. N., Livelli T. J., Axel R., Jessell T. M. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 928–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kursar J. D., Nelson D. L., Wainscott D. B., Cohen M. L., Baez M. (1992) Mol. Pharmacol. 42, 549–557 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox D. A., Cohen M. L. (1995) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 272, 143–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich A., Miller S. M., Gibbons S. J., Malysz J., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 284, G313–G320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ou Y., Gibbons S. J., Miller S. M., Strege P. R., Rich A., Distad M. A., Ackerman M. J., Rae J. L., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2002) Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 14, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gafni J., Munsch J. A., Lam T. H., Catlin M. C., Costa L. G., Molinski T. F., Pessah I. N. (1997) Neuron 19, 723–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banasr M., Hery M., Printemps R., Daszuta A. (2004) Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 450–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang G. J., Herbert J. (2005) Neuroscience 135, 803–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radley J. J., Jacobs B. L. (2002) Brain Res. 955, 264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cattaneo M. G., Fesce R., Vicentini L. M. (1995) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 291, 209–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdouh M., Albert P. R., Drobetsky E., Filep J. G., Kouassi E. (2004) Brain Behav. Immun. 18, 24–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sempere T., Urbina M., Lima L. (2004) Neuroimmunomodulation 11, 307–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wouters M. M., Farrugia G., Schemann M. (2007) Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 19, 5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ron D., Kazanietz M. G. (1999) FASEB J. 13, 1658–1676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu T. T., Hsieh Y. H., Hsieh Y. S., Liu J. Y. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 103, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shatos M. A., Hodges R. R., Oshi Y., Bair J. A., Zoukhri D., Kublin C., Lashkari K., Dartt D. A. (2009) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 614–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ou W. B., Zhu M. J., Demetri G. D., Fletcher C. D., Fletcher J. A. (2008) Oncogene 27, 5624–5634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukumoto S., Nishizawa Y., Hosoi M., Koyama H., Yamakawa K., Ohno S., Morii H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13816–13822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto M., Acevedo-Duncan M., Chalfant C. E., Patel N. A., Watson J. E., Cooper D. R. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 279, C587–C595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerda S. R., Mustafi R., Little H., Cohen G., Khare S., Moore C., Majumder P., Bissonnette M. (2006) Oncogene 25, 3123–3138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Narita M., Suzuki M., Narita M., Yajima Y., Suzuki R., Shioda S., Suzuki T. (2004) Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 479–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner L. M., Takemoto D. J. (2001) Mol. Vis. 7, 57–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finniss S., Lee H. K., Xiang C., Cazacu S., Zenklusen J. C., Fine H. A., Rennert J., Berens M. E., Mikkelsen T., Brodie C. (2006) Proc. Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res. 47, ( abstr. 4278) 1004–1005 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verbeek D. S., Goedhart J., Bruinsma L., Sinke R. J., Reits E. A. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 2339–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furness J. B., Hind A. J., Ngui K., Robbins H. L., Clerc N., Merrot T., Tjandra J. J., Poole D. P. (2006) Histochem. Cell Biol. 126, 537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poole D. P., Van Nguyen T., Kawai M., Furness J. B. (2004) Histochem. Cell Biol. 121, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blay P., Astudillo A., Buesa J. M., Campo E., Abad M., García-García J., Miquel R., Marco V., Sierra M., Losa R., Lacave A., Braña A., Balbín M., Freije J. M. (2004) Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4089–4095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X. Y., Ward S. M., Gerthoffer W. T., Sanders K. M. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 285, G593–G601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keenan C., Goode N., Pears C. (1997) FEBS Lett. 415, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martiny-Baron G., Kazanietz M. G., Mischak H., Blumberg P. M., Kochs G., Hug H., Marmé D., Schächtele C. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9194–9197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gschwendt M., Dieterich S., Rennecke J., Kittstein W., Mueller H. J., Johannes F. J. (1996) FEBS Lett. 392, 77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hausser A., Storz P., Hübner S., Braendlin I., Martinez-Moya M., Link G., Johannes F. J. (2001) FEBS Lett. 492, 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bagowski C. P., Stein-Gerlach M., Choidas A., Ullrich A. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5567–5576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hurd C., Waldron R. T., Rozengurt E. (2002) Oncogene 21, 2154–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vigorito E., Kovesdi D., Turner M. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 1455–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horváth V. J., Vittal H., Lörincz A., Chen H., Almeida-Porada G., Redelman D., Ordög T. (2006) Gastroenterology 130, 759–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi K. M., Gibbons S. J., Roeder J. L., Lurken M. S., Zhu J., Wouters M. M., Miller S. M., Szurszewski J. H., Farrugia G. (2007) Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 19, 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.