Abstract

Biliverdin reductase A (BVR) catalyzes the reduction of biliverdin (BV) to bilirubin (BR) in all cells. Others and we have shown that biliverdin is a potent anti-inflammatory molecule, however, the mechanism by which BV exerts its protective effects is unclear. We describe and elucidate a novel finding demonstrating that BVR is expressed on the external plasma membrane of macrophages (and other cells) where it quickly converts BV to BR. The enzymatic conversion of BV to BR on the surface by BVR initiates a signaling cascade through tyrosine phosphorylation of BVR on the cytoplasmic tail. Phosphorylated BVR in turn binds to the p85α subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and activates downstream signaling to Akt. Using bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) to initiate an inflammatory response in macrophages, we find a rapid increase in BVR surface expression. One of the mechanisms by which BV mediates its protective effects in response to lipopolysaccharide is through enhanced production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) the prototypical anti-inflammatory cytokine. IL-10 regulation is dependent in part on the activation of Akt. The effects of BV on IL-10 expression are lost with blockade of Akt. Inhibition of surface BVR with RNA interference attenuates BV-induced Akt signaling and IL-10 expression and in vivo negates the cytoprotective effects of BV in models of shock and acute hepatitis. Collectively, our findings elucidate a potentially important new molecular mechanism by which BV, through the enzymatic activity and phosphorylation of surface BVR (BVR)surf modulates the inflammatory response.

Biliverdin reductase (BVR)2 mediates the rapid conversion of biliverdin to bilirubin (1, 2). BVR also functions as a dual tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase (3, 4) and as a transcription factor that binds promoters within Ap-1 sites (5). Biliverdin and bilirubin both possess potent cytoprotective properties in a variety of animal models (6, 7) including those for ischemia/reperfusion injury following small bowel or liver transplantation (8–10), vascular injury (11), and endotoxic shock (6, 12). The mechanisms underlying these effects are still poorly understood and to date have not been linked to BVR activity per se, but attributed rather to the antioxidant power of biliverdin and bilirubin.

The concept that BVR may be an ideal docking protein for SH-2 domains (4) combined with the known anti-inflammatory effects of the bile pigments and rapid conversion of BV to BR in vivo, led us to hypothesize that BVR is expressed on the membrane and through its kinase activity regulates Akt signaling via recruitment of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). We present novel findings that the ability of biliverdin to prevent LPS-induced morbidity and mortality most likely requires BVR surface expression for specific activation of PI3K-Akt and IL-10. We suggest that this is the major pathway by which biliverdin inhibits the inflammatory response and that these molecular events are natural protective mechanisms involved in the innate immune response to bacterial endotoxin that enables homeostasis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Treatment

The mouse macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7 (RAW), and HEK cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Invitrogen). For treatment, cells were seeded 24 h before experiment. Biliverdin (Frontier Scientific) was freshly prepared in DMSO (Sigma) and kept in the dark before and during treatment. Final concentration of DMSO in medium was <0.01%. LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 0127:B08, Sigma) was dissolved in PBS and used for treatment at concentrations ranging from 1 to 1000 ng/ml. GGTI-287, a selective inhibitor of geranylgeranyl transferase I (Calbiochem), geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (Sigma), and dl-β-hydroxymyristic acid (Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and used at concentrations of 1, 3, and 100 μm, respectively. LY294002 (Sigma; 10 μm) was used as a selective inhibitor of PI3K.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated and cultured as previously described (13). Adenovirus containing Cre recombinase was used at 50 multiplicity of infection on the third day of culture. Macrophages were treated and harvested on the fifth day of culture.

Animal Treatment

C57BL6/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. PI3K p85β−/−/p85α loxp mice were kindly provided by Prof. Lewis Cantley (BIDMC, Harvard Medical School). All animals were held under pathogen-free conditions and the experiments were approved by the BIDMC Animal Care and Use Committee. Lung, liver, and spleen as well as blood samples were harvested for immunohistochemical and immunostaining analyses from control and LPS-injected mice (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) for 6 h. Biliverdin/bilirubin was freshly dissolved in 0.2 n NaOH, adjusted to a final pH of 7.4 with HCl, and kept in the dark. Mice were administered biliverdin or bilirubin (35 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) 16 h and again 2 h prior to LPS/d-galactosamine (250 μg/kg, intraperitoneal/750 mg/kg, intraperitoneal; E. coli serotype 0127:08, Sigma). Serum bilirubin levels were evaluated spectrophotometrically (Sigma Kit), according to the manufacturer's protocol in a separate group of non-LPS-treated mice. For adenovirus experiments, mice were administered either Ad-BVR-siRNA or Ad-Y5 (2 × 109 plaque-forming units intraperitoneally) 5 days prior to LPS/d-Gal.

Immunohistochemistry

Liver, lung, and spleen tissue samples were embedded in freezing medium and stored at −80 °C. Five-μm sections were fixed in cold acetone and embedded in paraffin followed by immunohistochemistry using fluorescently tagged or horseradish peroxidase-tagged secondary antibody as previously described (10).

Immunofluorescence and Flow Cytometry and Total Internal Reflective Fluorescence (TIRF)

RAW cells were seeded on glass (Fisher) and treated with 10–100 ng/ml LPS for various time points as described. For detection of surface antigens, cells were rinsed in PBS and blocked with 0.5% BSA (bovine serum albumin, RIA grade, Sigma) in PBS for 1 h followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Staining of intracellular antigens was performed by membrane permeabilizers with Triton X-100 or methanol, followed by rinsing with PBS and blocking with 0.5% BSA in PBS. Fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed, fixed with 0.25% paraformaldehyde, and covered with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (+/−) mounting medium. Fluorescence was viewed with a Zeiss Apotome Axiovert microscope at ×40 or ×60 magnification.

For flow cytometric analysis of surface antigens, cells were gently harvested, centrifuged (300 × g for 5 min), and washed in PBS. Cells were blocked in 0.5% BSA in PBS for 30 min followed by 30 min incubation with primary antibodies. Afterward, cells were washed with blocking buffer and resuspended in fluorescently labeled antibodies and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min followed by extensive washing with PBS. Cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences FACS Sorter).

TIRF measurements were performed on cells culture and stained as for immunofluorescence analysis with few modifications. Briefly, cells were seeded on the glass and after treatment, washed with 1× PBS. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Cells were rehydrated with 5 washes of PBS and blocked for 45 min with 2% BSA. Following staining cells were washed, stained with Hoechst for 30 s, and coverslipped with gelvatol and refrigerated until analysis with a TIRF microscope.

Source of Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for Western blotting analyses where indicated: rabbit anti-biliverdin reductase (Stressgen); rat anti-F4.80 (Vector Laboratory); mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Calbiochem); mouse anti-phosphotyrosine (Transduction Laboratories); and rabbit anti-phospho(Ser473)-Akt, rabbit anti-Akt, mouse anti-PI3K p85α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For fluorescence microscopy: FITC-anti-mouse IgG (Sigma); fluorescein anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratory); FITC anti-goat IgG (BD Sciences), and Alexa Fluor 350 anti-goat IgG (Molecular Probes) were used.

Cell Fractionations

Cytosolic and membrane cell fractions were isolated following the manufacturer's protocol of the Plasma Membrane Protein Extraction Kit (BioVision, CA). Briefly, cells were rinsed in ice-cold PBS, resuspended in homogenization buffer, and incubated on ice for 1 h. To isolate total cellular membrane proteins, cell or liver homogenate was centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and further centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. To purify plasma membrane protein, the pellet was resuspended in a 1:1 upper phase solution:lower phase solution, followed by 5 min incubation on ice. The lower phase was extracted twice with the upper phase solution by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min. The upper phase was collected and diluted in 5 volumes of water for 5 min on ice. The pellet of the plasma membrane protein was obtained by centrifugation for 10 min (14,000 × g). Protein extracts were subjected to further analyses by immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, and for biliverdin reductase activity assay as previously described (14).

Plasmids and Transfections

BVR198 (Tyr → Phe) Construction

Overlap extension PCR was applied for construction of point mutation in hBVR cDNA and followed by ligation to pcDNA3.1 plasmid between KpnI and XhoI restriction sites. The following primers were used with the underlined mutation and marked restriction sites: 1) 5′-CGACGGTACCGAAGGAAGAGACCAAGATGAA-3′; 2) 5′-GAAAGGAAGATCAGTTCATGAAAAT-3′; 3) 5′-GACACTCGAGTGGAAGTGCTACATCACCT-3′; 4) 5′-CTTTCCTTCTAGTCAAGTACTTTTACTGTCA-3′. In PCR-1, primers 1 and 4 were used to amplify a fragment of 609 bp and in PCR-2, primers 2 and 3 gave a fragment of 335 bp. Both fragments gave the whole BVR cDNA with point mutation in the PCR-3 with primers 1 and 3. Proper cloning and mutagenesis were verified by restriction site analysis and sequencing.

Mutant Vectors

The Glu97 and Glu47 mutants were generated as previously described and characterized (27). BVR97 (Glu → Ala) was cloned as a single fragment between the KpnI and NotI sites of pcDNA3.1 and the mutation was introduced using the following primer: 5′-TCC CGA GGG CCC TTC TCG ACA CGA AGC C. BVR47 (Glu → Ala) was cloned between the KpnI and XhoI sites of pcDNA3.1 using the following primers: 1) 5′-CTG AGC GGC CGC CAA TGA CAG TGT CAT GGG GTA GGC CAC AAG G; and 2) 5′-CGA GAA GGG CCC TCG GGA GCA TTG ATG GAG.

Dominant-negative Akt and control constructs were a kind gift from Dr. Alex Toker (BIDMC). RAW cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or Amaxa nucleofection reagents (Amaxa) according to the vendor's protocol. HEK cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 200 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transfection efficiency estimated by FACS analysis (BD Biosciences FACSort) was 30–40%.

RNAi Transfections

Pre-designed and verified annealed RNAi against BVRa, GFP RNAi, and negative control RNAi were purchased from Ambion (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). Fifty nm RNAi was used for each transfection together with 5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In some experiments re-transfection with RNAi after 2 days of incubation was performed. BVR protein knock-down was confirmed 100 h after transfection as previously described (15).

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Snap-frozen tissue samples were homogenized in ice-cold tissue lysis buffer (250 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing the protease inhibitor mixture Complete Mini) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were lysed by a freeze-thaw cycle in ice-cold lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 1 mm sodium fluoride, and the protease inhibitor mixture). Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 × g at 4 °C and supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). 10–20 μg of each protein sample was electrophoresed on NuPAGE 4–12% BisTris gel (Invitrogen) in NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Invitrogen). For co-immunoprecipitation, 100–500 μg of protein lysates in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm sodium fluoride, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 10 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and the protease inhibitor mixture) were mixed with appropriate antibodies and 30 μl of Protein A/G Plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz) and then rocked for 2.5 h at 4 °C. The proteins were washed with RIPA buffer and eluted (95 °C, 5 min in SDS loading buffer). The proteins were then subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Ready Gel Blotting Sandwiches; Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, probed with appropriate primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:5000, and visualized using Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) or Femto Maximum Sensitivity substrate (Pierce), followed by exposure to the autoradiography film (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, UT).

ELISA for IL-10

IL-10 was measured in culture medium using Quantikine Immunoassay (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical comparison was performed by use of Student's t test (SPSS Inc) (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

Membrane-associated Biliverdin Reductase Is a Functional Surface Antigen in Macrophages

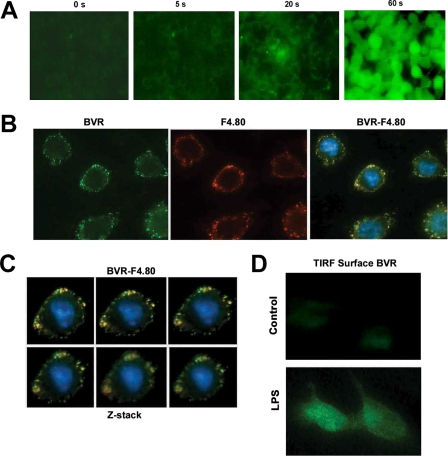

We employed several techniques, including TIRF microscopy, immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry (FACS) to demonstrate that BVR is expressed on the external plasma membrane. Live cell imaging of BVR activity showed rapid conversion (seconds) of non-fluorescent biliverdin to fluorescent bilirubin (emission at 512 nm), which was lost in the presence of trypsin (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S1). These observations lead us to hypothesize that BVR may be a membrane protein with an active site present on the external leaflet of the membrane. Co-immunostaining with BVR and the macrophage-specific F4.80 antibodies show the co-localization of surface BVR with the well characterized surface antigen in unstimulated RAW 264.7 (RAW) macrophages (Fig. 1B). BVR and F4.80 co-stained cells were then imaged by Z-stack analysis with similar results (Fig. 1C). The induced expression of BVR by LPS on the cell surface was observed via TIRF microscopy (Fig. 1D), which permits specific detection of surface-only expressed proteins.

FIGURE 1.

Biliverdin is converted to bilirubin by surface biliverdin reductase. A, time lapse studies of the conversion of biliverdin (non-fluorescence) to bilirubin (green fluorescence) in RAW macrophages. The representative pictures were taken 0–60 s following addition of 50 μm biliverdin at ×20 magnification. Images are representative of 8–10 fields of view from three independent experiments. B, immunofluorescence staining of BVR-FITC and F4.80-Cy5 in the membrane of RAW 264.7 macrophages. Non-permeabilized RAW cells were seeded on glass coverslips for 24 h and stained with antibody to BVR and F4.80 followed by application of fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. Images are representative of 6–8 fields of view from two independent experiments and were taken at ×40 magnification. C, Z-stack images of the same RAW cell taken at 0.2-μm intervals demonstrate co-localization of BVR and F4.80. Pictures were taken at ×40 magnification. D, TIRF microscopy of BVR surface expression in the presence and absence of 100 ng/ml LPS for 14 h. RAW cells were seeded on glass coverslips and treated with LPS. RAW cells were stained for BVR. TIRF microscopy allows the visualization of only proteins that are on the external cell membrane surface. Images are representative of two independent experiments and 3–5 fields of view.

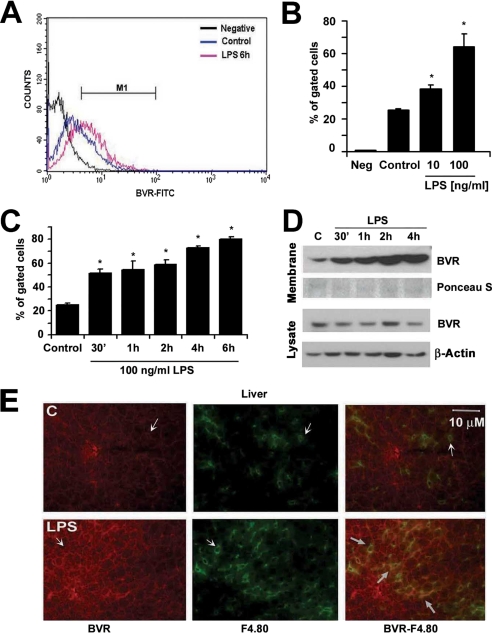

We next tested the effects of LPS on BVR expression in macrophages to potentially understand the anti-inflammatory actions of biliverdin that others and we have reported (6). There was a clear induction of BVR on the cell surface as measured by flow cytometry of non-permeabilized RAW cells (Fig. 2A). LPS administration resulted in a time- and dose-dependent increase in BVR surface expression as early as 30 min after treatment with LPS, suggesting post-transcriptional activation of BVR (Fig. 2, B and C). LPS had no effect on the level of total BVR (data not shown), whereas it up-regulated membrane-bound BVR. We confirmed the time-dependent increase in membrane BVR after LPS (100 ng/ml) treatment by immunoblotting the lysates of membrane fractions in macrophages (Fig. 2D). This was specific for membrane expression as no change in BVR expression in total lysates was observed Fig. 2D). To evaluate whether our in vitro data were reflected in vivo, we performed immunohistochemical staining for BVR in the livers of mice treated with LPS. Staining results revealed induction of BVR in hepatic macrophages 6 h after LPS injection (Fig. 2E) with surface expression detected by double staining with antibodies to BVR and the macrophage marker F4.80 (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Biliverdin reductase is a surface antigen in RAW macrophages and maintains enzymatic activity. A–C, cell surface expression of BVR in non-permeabilized and non-fixed RAW 264.7 macrophages in the presence and absence of LPS analyzed by flow cytometry. IgG-FITC conjugate was used as a negative control. Data are representative of three independent experiments. A, representative histogram of FITC-BVR-labeled non-permeabilized RAW cells control and treated for 6 h with 100 ng/ml LPS. M1 is a gate window that was chosen based on negative control staining. B, quantitative analysis of flow cytometry of RAW cell BVRsurf expression ± LPS (10–100 ng/ml) for 14 h. Neg, negative control; IgG-FITC, average % of gated cells (M1) ± S.D. is shown from three independent experiments performed in duplicates. C, kinetics of surface BVR expression by flow cytometry determined over time in RAW cells treated ± 100 ng/ml LPS. Results represent the average % of gated cells (M1) ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments. In B and C, * indicates p < 0.05 versus non-LPS-treated. D, immunoblotting of BVR in the membrane and total lysate fractions from RAW cells treated with 100 ng/ml LPS over time. Cytoplasmic membranes were isolated using a Membrane Isolation Kit as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Ponceau S staining is shown as a loading control in the membrane fraction. E, tissue expression of BVR-Cy5 and F4.80-FITC was detected in macrophages (Kupffer cells) in the liver, which was more pronounced 6 h following LPS injection. Arrows indicate positive BVR staining in Kupffer cells (co-localization with F.4.80 expression) as well as hepatocytes. Images are representative of 6–8 sections from four mice.

Finally, to substantiate BVR membrane localization and activity, we performed quantitative experiments with purified membrane fragments. Addition of biliverdin to cells resulted in rapid generation of bilirubin with an increase in absorbance at 450 nm at 1 h from 0.003 ± 0.001 to 0.007 ± 0.001 relative activity change in the cytosolic fraction versus an increase from 0.005 ± 0.002 to 0.015 ± 0.002 (p < 0.02) in purified membrane fractions. Collectively, the data presented in Figs. 1 and 2 support membrane-bound, enzymatically active BVR on the external leaflet of the plasma membrane.

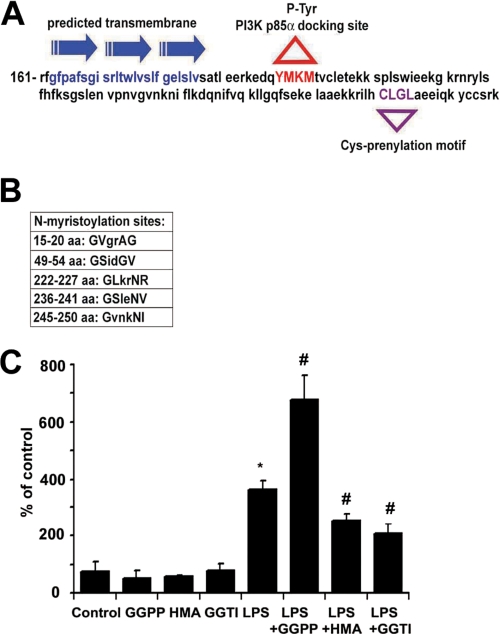

Sequence Analysis of BVR Identifies a Transmembrane Spanning Region

A structure analysis of BVR using the transmembrane prediction program (16) identified a 24-amino acid transmembrane segment among three α-helixes (163–186 amino acids) (Fig. 3A). The C terminus of BVR comprises specific prenylation sites for geranylgeranyl transferase (CLGL), which in addition to five myristoylation sites may be crucial for recruitment and association of BVR to the membrane (Fig. 3, A and B). Lipid modifications of many proteins enable them to localize to the plasma membrane (17). Inhibition of prenylation or myristoylation prevented LPS-induced cell surface BVR expression (p < 0.005), whereas addition of GGPP resulted in augmentation of LPS-induced BVR surface expression (Fig. 3C; p < 0.01 versus LPS). These data demonstrate that BVR is translocated from the cytosol to the cell membrane by post-translational protein modification, i.e. prenylation and myristoylation. The tyrosine phosphorylation motif (YMKM) is also present in the BVR sequence as previously described (4) (Fig. 3A). Although the data in Fig. 3 do not distinguish between internal and external BVR leaflet localization, the data in Figs. 1 and 2 support the concept that BVR is localized to the external plasma surface.

FIGURE 3.

Membrane localization of BVR is partially dependent on prenylation and myristoylation. A, predicted motifs and transmembrane domain (blue) in the sequence of BVR (161 amino acids are shown); Y198MKM, tyrosine phosphorylation motif (red) within which the tyrosine residue serves as the docking site for binding of the p85α subunit of PI3K; CLGL-prenylation motif (violet). B, predicted myristoylation sites in the BVR sequence as indicated. C, RAW cells were pre-treated with selective inhibitors of protein prenylation (GGTI), myristoylation (β-hydromyristric acid (HMA)), and an agonist of prenylation (GGPP) for 24 h followed by 14 h treatment with or without LPS (100 ng/ml). BVR surface expression was then measured by flow cytometry as described. Results represent means ± S.D., *, p < 0.005 versus non-LPS treated; #, p < 0.01 inhibitors/agonists + LPS versus LPS alone.

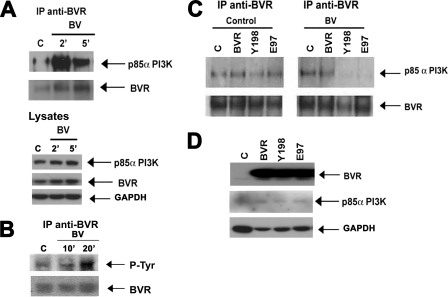

Phosphorylation of BVR in Response to BV Binding Leads to Interaction of BVR with the p85α Subunit of PI3K

To test our hypothesis that surface BVR interacts with a downstream kinase proximal to the membrane via its tyrosine phosphorylation motif, we explored a possible complex formation between BVR and the p85α subunit of PI3K in RAW macrophages. The p85α subunit of PI3K co-immunoprecipitates with BVR in BV-treated RAW cells without changing the total BVR or p85α expression in the lysates (Fig. 4A). After biliverdin treatment, BVR is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues (Fig. 4B) and there is greater binding of p85α to BVR (Fig. 4A). Mutation of the tyrosine that is responsible for the kinase activity (Tyr → Phe198) or catalytically inactive mutant (Glu → Ala97) resulted in a reduced interaction of BVR with p85α in response to BV (Fig. 4C). The Tyr198-Met199-Lys200-Met201 (YMKM) motif within BVR appears to be the binding site for the p85α subunit of PI3K leading to BV-BVR-mediated induction of Akt. Overexpression of BVR or either mutant had any effect on BVR or p85 expression (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

BV induces BVR interaction with the p85 α subunit of PI3K. A, immunoprecipitation of BVR in the total lysate of RAW cells treated with biliverdin (50 μm) for 2, 5, and 10 min and detection of p85α subunit of PI3K and BVR. Total BVR and p85α PI3K are also shown as control. Blots are representative for three independent experiments. B, BV induces BVR phosphorylation. Representative immunoblot demonstrating phosphorylation on tyrosine residues in BVR following BVR immunoprecipitation. C, immunoprecipitation of BVR in HEK cell lysates transfected with WT BVR (BVR), Y198P (Y198), and E97A (E97) mutants and treated with DMSO (control) or BV for 2 min and detection of the p85α subunit of PI3K. HEK cells were used to better observe the effects of mutant BVR versus WT vectors. Equal precipitation was confirmed by probing with anti-BVR antibody. Blots are representative of three independent experiments. D, immunoblot with antibodies against BVR and p85α PI3K in the lysates of HEK cells that were used as input samples for immunoprecipitation in C. The blot is representative of three independent experiments.

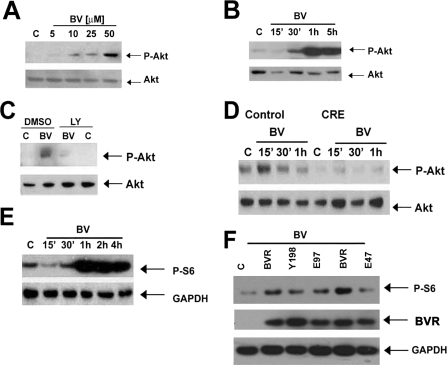

Given that Akt is downstream of PI3K, we next tested the effects of biliverdin administration on Akt activation. BV induced a time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of Akt in RAW cells (Fig. 5, A and B) and in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 5D). To test whether the effect of BV-induced activation of Akt is dependent on a PI3K-BVR interaction we used pharmacological and genetic approaches. The effect of BV on Akt phosphorylation is blocked by LY290024, a selective inhibitor of PI3K (Fig. 5C). We show that the effect of biliverdin is specifically mediated by the p85α subunit of PI3K but not the PI3Kβ subunit by employing bone marrow-derived macrophages from p85β PI3K−/− and conditional loxp p85α PI3K mice. The absence of p85α resulted in an inability of BV to activate Akt, whereas BV was able to activate Akt in bone marrow macrophages in wild type cells (Fig. 5D). Although there was increased phosphorylation of Akt after expression of WT BVR, introduction of a mutated (Tyr → Phe198) BVR blocked Akt phosphorylation (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

BV induces phosphorylation of Akt in macrophages. A, immunoblot analysis of P-Akt (Ser473) in the lysates of RAW macrophages treated with BV (5–50 μm for 1 h). B, BV-treated RAW cells (15 min to 5 h, at 50 μm). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. C, immunoblot analysis of P-Akt in RAW cells treated for 1 h with BV (50 μm) after 30 min of preincubation with 10 μm LY290024 or appropriate vehicle controls (DMSO). Data are representative of two independent experiments. D, BMDM were harvested and differentiated for 3 days from PI3K p85β−/−/p85α floxp and then infected with adeno-Cre-recombinase (CRE) or adeno-Y5-control. Biliverdin (50 μm, 15 min to 1 h) treatment was added on day 5 (differentiated macrophages) and immunoblotting for P-Akt was performed as above. Data are representative of three experiments. E, S6 phosphorylation (P-S6) kinetics in RAW cells treated with 50 μm biliverdin over time at the indicated time points. DMSO-treated controls (C) were harvested at 1 h. F, immunoblot of P-S6 in RAW cells overexpressing WT (BVR), Y198P (Y198), E97A (E97), or E47A (E47) mutant BVR ± biliverdin (50 μm) for 1 h. All membranes were reprobed for total Akt, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH), or total S6 where indicated.

To confirm and validate the activation of Akt by BVR, we employed BVR mutants on BV-induced downstream targets. We observed strong phosphorylation of S6 protein (Fig. 5E) as supportive evidence of Akt activation, which was inhibited by pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K (data not shown). Introduction of a catalytically inactive mutant Glu → Ala97 resulted in a loss in the ability of BVR to convert biliverdin to bilirubin (supplemental Fig. S2). Importantly, inhibition in the binding of p85α to PI3K to BVR (Fig. 5B), and subsequent loss of S6 phosphorylation (Fig. 5F) in cells treated with BV suggests that the activity of BVR is critical for the receptor function of BVRsurf. We also generated an additional BVR mutant Glu → Ala47, which is catalytically active (supplemental Fig. S3) but the edge of the binding pocket for BV and NADH/NADPH is disrupted. With expression of this particular mutant, we observed inhibition of biliverdin-mediated Akt signaling, whereas WT BVR-mediated BV signaling remained normal (Fig. 5F).

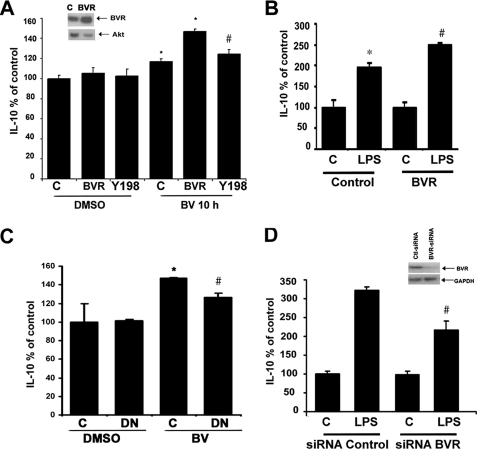

BVR-mediated Signaling through Akt Increases IL-10 Production in Macrophages

Previously we have shown that BV enhances IL-10 expression in macrophages and in vivo in rats. Therefore, we evaluated whether a functional link exists between BVR-mediated Akt signaling and production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Overexpression of BVR (70 ± 10% efficiency) led to increased IL-10 production in BV-stimulated RAW macrophages (Fig. 6A), whereas the Tyr → Pro198 mutant BVR blocked BV-induced signaling through PI3K-Akt to increase IL-10 (Fig. 6A). Moreover, introduction of a dominant-negative Akt abrogated BV-mediated induction of IL-10 (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Surface BVR mediates biliverdin Akt-IL-10 signaling. A, IL-10 expression was measured by ELISA in the media of RAW cells transfected with WT BVR or Y198P mutant BVR in the presence or absence of BV for 10 h. Results represent percent of control ± S.D. of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments. Vector transfection efficiency was determined to be 78 ± 10% by immunofluorescence. *, p < 0.05 BV treated and BVR + BV-treated RAW cells versus corresponding controls; #, p < 0.05 Tyr198 + BV versus BVR + BV. Inset shows BVR levels in the RAW cells transfected with BVR and control vector. B, IL-10 expression by ELISA in the media of RAW cells transfected with WT BVR and then treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. *, p < 0.01 LPS versus control; #, p < 0.05 BVR + LPS versus Control + LPS; data represent percent of control ± S.D. from three independent experiments in duplicate. C, IL-10 ELISA results in cells transfected with dominant-negative Akt or pcDNA3 controls ± BV (10 h), demonstrating that BV is unable to increase IL-10 in cells unable to signal through Akt. Data represent mean ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments in triplicate. D, IL-10 ELISA was performed in supernatants from RAW cells transfected with siRNA control or BVR-siRNA and then treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. Inset shows immunoblot of BVR in RAW macrophages transfected with BVR-siRNA or control RNAi. Blot is representative of two independent experiments to validate knockdown. Data represent percent of control ± S.D. and are representative of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01 LPS versus control; #, p < 0.05 siRNA BVR versus siRNA control. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

LPS stimulates rapid induction of HO-1 and biliverdin thereby becomes available as a substrate for BVR as heme is degraded. To test the function of BVR in LPS-mediated IL-10 production, we overexpressed or silenced BVR (Fig. 6, B–D). Overexpression of BVR enhanced LPS-induced production of IL-10 (Fig. 6B), whereas inhibition of BVR or Akt with siRNA or dominant-negative mutants led to significant inhibition of IL-10 production (Fig. 6, C and D). These data suggest that BV acts in part via a BVR-PI3K-Akt pathway to mediate its anti-inflammatory effects in response to LPS through augmented expression of IL-10 and offers one explanation for BV-elicited protection, in addition to its antioxidant power. The regulation of IL-10 expression by BV/BVR, whereas significant is not striking and we speculate that IL-10 regulation is only part of the mechanism by which BV modulates the inflammatory response to impart protection in the animal models described below.

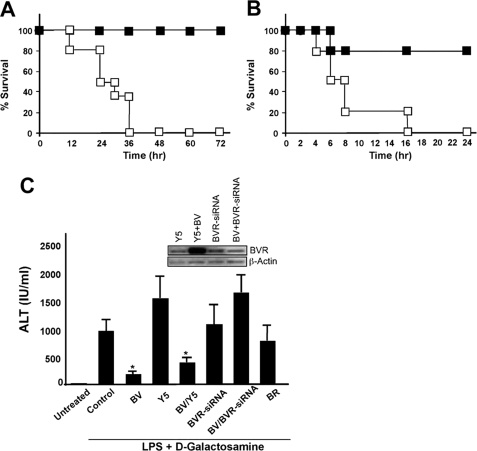

BV Protects against Lethal Endotoxemia and Acute Hepatitis via BVR

We next evaluated the in vivo conversion of biliverdin to bilirubin and the efficacy in a model of lethal endotoxic shock. Biliverdin given as a bolus to mice was rapidly converted to bilirubin, reaching a maximum concentration of bilirubin of 50 ± 7.4 μm at 5 min (the earliest time point measured) from a baseline of 6 ± 2.8 μm at 5 min (p < 0.001), and returning to baseline by 6 h (data not shown). We also tested the ability of biliverdin to prevent acute inflammation following a lethal injection of LPS alone or LPS/d-Gal (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) to induce acute liver failure. One group of mice received biliverdin (35 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) 16 and 2 h prior to LPS-treated mice or LPS/d-Gal-treated mice, whereas controls received saline in both models. In the experiment with LPS alone, all saline-treated mice were dead by 24 h, whereas 100% of biliverdin-treated mice survived long-term (Fig. 7A). We further confirmed our observation with LPS/d-Gal treatment and observed 80% survival rate in the BV-treated group (Fig. 7B). To test whether the protection conferred by biliverdin required the action of BVR, we blocked BVR with an adenovirus expressing BVR-siRNA based on the published sequence (7). Separate groups of mice were administered 2 × 109 plaque-forming units/mouse intravenously of either Ad-BVR-siRNA or Ad-Y5 control virus, diluted in normal saline. After 5 days, the time when viral expression is maximal and results in high and specific expression of the vector primarily in the liver, we administered LPS/d-Gal in the presence and absence of biliverdin. Six to eight hours later, serum alanine aminotransferase was measured and the livers were harvested and snap frozen for subsequent Western blot analyses. Animals treated with BV or BV+Y5 control virus showed significant inhibition in LPS/d-Gal-induced hepatitis as assessed by serum levels of alanine aminotransferase. BV, but not bilirubin (BR) at the doses tested, blocked LPS/d-Gal-induced increases in alanine aminotransferase, whereas those animals in which BVR was blocked with BVR-siRNA expressed serum alanine aminotransferase levels comparable with LPS/D-Gal controls (Fig. 7C). BVR knockdown was confirmed by Western blot in liver lysates (Fig. 7C, inset). These data validate our in vitro data showing that the protection afforded by BV requires the activity of BVR.

FIGURE 7.

Biliverdin requires biliverdin reductase to protect against lethal endotoxic shock and acute hepatitis in mice. A, mice were administered biliverdin (35 mg/kg, intraperitoneal, closed squares) or saline (open squares) followed by administration of a lethal dose of endotoxin (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and monitored for survival. Mice that survived 72 h survived long term. n = 4–6 mice/group. Note that BV administration prevented LPS-induced lethality. B, mice were administered BV or saline as above followed by injection of LPS and d-galactosamine and monitored for survival. Mice that survived 24 h in this model survived long term (n = 4–6 mice/group). C, liver injury as assessed by alanine aminotransferase. Mice were treated with Ad-BVR-siRNA, Ad-Y5 as control, or saline vehicle control. Five days later, all mice were administered BV, BR, or saline prior to LPS/d-galactosamine by Western blot (inset). Results are mean ± S.D. of four to six mice/group. Efficacy of BVR knockdown is shown in the representative inset blot. *, p < 0.03 versus control or Y5.

DISCUSSION

We describe here a novel paradigm showing that BVR, the enzyme that converts biliverdin to bilirubin, is a surface protein (BVRsurf) that initiates a signaling cascade upon the binding of biliverdin involving PI3K, activation of Akt, and downstream production of IL-10. We suggest that the remarkable anti-inflammatory effects of biliverdin, previously attributed solely to the antioxidant properties of biliverdin and bilirubin, are in very significant part mediated via this novel mechanism (6, 12). We submit that BVR functions in part as a ligand-activated signaling protein that resembles tyrosine kinase receptors and as such is directly involved in regulation of the innate immune response. We define this localized membrane form as BVRsurf.

BVR has been studied with regard to functions other than converting biliverdin to bilirubin. It has been shown by others that BVR can function as a kinase (3, 4) and as a transcription factor involved in the regulation of heme oxygenase-1 (5). BVR is present in various compartments of the cell including the inner cell membrane in endothelial cells in association with HO-1 (18, 19).

There are to date many reports in the literature demonstrating the ability of biliverdin to modulate the inflammatory response. The protective potential of biliverdin/bilirubin stems from a history of studies of the enzyme HO-1 (20, 21). HO-1 has emerged over the last decade as a powerful cytoprotective molecule, yet the mechanism(s) by which it functions remains unclear. HO-1 acts on heme and generates three products: biliverdin, carbon monoxide (CO), and Fe2+. Recent studies of these products have begun to shed light on the mechanisms of HO-1 action as a homeostatic gene (8, 22–24).

The sequence of amino acids in BVR is consistent with our findings regarding the signaling cascade initiated by biliverdin-BVR. The tyrosine motif of BVR present on the cytosolic side resembles the binding motif of platelet-derived growth factor receptor for the p85α subunit of PI3K. We suggest that biliverdin stimulates BVR phosphorylation of tyrosine 198, which is the critical residue within the membrane that enables BVR to bind the p85α subunit of PI3K and signal to activate Akt. The regulation of this interaction is complex and perhaps in part involves low constitutive regulation due to continuous heme turnover by the cell during normal metabolism and therefore constitutive low basal levels of biliverdin being generated. This would explain the baseline interaction between BVR and p85-PI3K. An EYP (Glu97-Tyr98-Pro99) motif in the active site is believed to be necessary for biliverdin to bilirubin conversion, which lies in the external N terminus region of the enzyme. Indeed our data using the E97A mutant of BVR strongly support this site as important for conversion of biliverdin to bilirubin and for transmission of signaling by BVR. The electrons necessary for the reduction of biliverdin may originate either from extracellular NADH (e.g. by membrane NADH dehydrogenase) (25) or donated from other sources such as transmembrane transporters of electrons (e.g. NADPH oxidase) (26). The E47A mutant did not affect conversion of biliverdin to bilirubin, however, it does affect the edge of the β2 strand of substrate and cofactor binding in the pocket, which likely influences the strength of their interaction with BVR as characterized and reported by Kikuchi et al. (27). If the binding of biliverdin is insufficient as is the case with many ligand-receptor interactions, BVR does not mediate the signaling to Akt and its downstream target S6 as evidenced by the E47A mutant. These data strongly suggest that conversion of BV to BR leads to a conformational change that is important in transmitting the signal. This aspect of BVR function may represent a similar transduction pattern as that observed with the Notch receptor. BVR in a manner similar to Notch could be cleaved and translocated to the nucleus to bind DNA as a cleaved fragment.

The expression of BVR on the surface is an important finding and provides a key piece of the puzzle in our understanding of this enzyme and for the cytoprotective heme oxygenase system in general. The presence of surface BVR offers a novel and regulated cell signaling mechanism by which biliverdin as a ligand can exert anti-inflammatory (protective) effects other than via its antioxidant power. First, we elucidate a signaling pathway by which biliverdin as a ligand for BVR can direct cellular function toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype in addition to its antioxidant power. And finally we present relevant in vivo findings supporting a role for BVR in regulating the immune response to prevent multiorgan injury and failure in response to endotoxin. We suggest that this is a major natural mechanism used by the body for defense and to re-establish and maintain homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge G. A. May and Kenichiro Yamashita for help with the animal experiments and Dr. Jozef Dulak for helpful contributions to the data analyses and interpretation. We thank the Julie Henry Fund at the Transplant Center of the BIDMC for their support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-071797 and HL-076167 (to L. E. O.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- BVR

- biliverdin reductase

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- IL

- interleukin

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- RNAi

- interfering RNA

- Ad

- adenovirus

- TIRF

- total internal reflective fluorescence

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- BR

- bilirubin

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonagh A. F. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 198–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doré S., Takahashi M., Ferris C. D., Zakhary R., Hester L. D., Guastella D., Snyder S. H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2445–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salim M., Brown-Kipphut B. A., Maines M. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10929–10934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner-Marmarosh N., Shen J., Torno M. D., Kravets A., Hu Z., Maines M. D. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 7109–7114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad Z., Salim M., Maines M. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9226–9232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarady-Andrews J. K., Liu F., Gallo D., Nakao A., Overhaus M., Ollinger R., Choi A. M., Otterbein L. E. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 289, L1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranano D. E., Rao M., Ferris C. D., Snyder S. H. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 99, 16093–16098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakao A., Otterbein L. E., Overhaus M., Sarady J. K., Tsung A., Kimizuka K., Nalesnik M. A., Kaizu T., Uchiyama T., Liu F., Murase N., Bauer A. J., Bach F. H. (2004) Gastroenterology 127, 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fondevila C., Katori M., Lassman C., Carmody I., Busuttil R. W., Bach F. H., Kupiec-Weglinski J. W. (2003) Transplant. Proc. 35, 1798–1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fondevila C., Shen X. D., Tsuchiyashi S., Yamashita K., Csizmadia E., Lassman C., Busuttil R. W., Kupiec-Weglinski J. W., Bach F. H. (2004) Hepatology 40, 1333–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ollinger R., Bilban M., Erat A., Froio A., McDaid J., Tyagi S., Csizmadia E., Graça-Souza A. V., Liloia A., Soares M. P., Otterbein L. E., Usheva A., Yamashita K., Bach F. H. (2005) Circulation 112, 1030–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W. W., Smith D. L., Zucker S. D. (2004) Hepatology 40, 424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin B. Y., Jiang G., Wegiel B., Wang H. J., Macdonald T., Zhang X. C., Gallo D., Cszimadia E., Bach F. H., Lee P. J., Otterbein L. E. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5109–5114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutty R. K., Maines M. D. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 3956–3962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegiel B., Bjartell A., Culig Z., Persson J. L. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 122, 1521–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persson B., Argos P. (1996) Protein Sci. 5, 363–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magee T., Seabra M. C. (2005) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maines M. D., Ewing J. F., Huang T. J., Panahian N. (2001) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 296, 1091–1097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H. P., Wang X., Galbiati F., Ryter S. W., Choi A. M. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 1080–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stocker R. (2004) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 6, 841–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otterbein L. E., Soares M. P., Yamashita K., Bach F. H. (2003) Trends Immunol. 24, 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerbraun B. S., Billiar T. R., Otterbein S. L., Kim P. K., Liu F., Choi A. M., Bach F. H., Otterbein L. E. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 1707–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sass G., Seyfried S., Parreira Soares M., Yamashita K., Kaczmarek E., Neuhuber W. L., Tiegs G. (2004) Hepatology 40, 1128–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berberat P. O., A-Rahim Y. I., Yamashita K., Warny M. M., Csizmadia E., Robson S. C., Bach F. H. (2005) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 11, 350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Sancho J., Sanchez A., Handlogten M. E., Christensen H. N. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 1488–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun I. L., Navas P., Crane F. L., Morré D. J., Löw H. (1987) Biochem. Int. 14, 119–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikuchi A., Park S. Y., Miyatake H., Sun D., Sato M., Yoshida T., Shiro Y. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.