Abstract

On sensory neurons, sensitization of P2X3 receptors gated by extracellular ATP contributes to chronic pain. We explored the possibility that receptor sensitization may arise from down-regulation of an intracellular signal negatively controlling receptor function. In view of the structural modeling between the Src region phosphorylated by the C-terminal Src inhibitory kinase (Csk) and the intracellular C terminus domain of the P2X3 receptor, we investigated how Csk might regulate receptor activity. Using HEK cells and the in vitro kinase assay, we observed that Csk directly phosphorylated the tyrosine 393 residue of the P2X3 receptor and strongly inhibited receptor currents. On mouse trigeminal sensory neurons, the role of Csk was tightly controlled by the extracellular level of nerve growth factor, a known algogen. Furthermore, silencing endogenous Csk in HEK or trigeminal cells potentiated P2X3 receptor responses, confirming constitutive Csk-mediated inhibition. The present study provides the first demonstration of an original molecular mechanism responsible for negative control over P2X3 receptor function and outlines a potential new target for trigeminal pain suppression.

ATP-activated P2X3 receptors are expressed almost exclusively by mammalian sensory neurons to play an important role in the transduction of painful stimuli to the central nervous system (1). Activation of P2X3 receptors by ATP released during acute and chronic pain is thought to send nociceptive signals to central pain-related networks (2). In view of the multitude of environmental stimuli normally reaching sensory terminals, the question then arises how inappropriate activation of P2X3 receptors is normally prevented. This process may contribute to suppression of continuous pain sensation in conjunction with central synaptic inhibition.

The molecular pathways triggered by algogenic substances and responsible for modulating P2X3 receptor structure and function remain incompletely understood. This topic is of particular interest because it can provide original clues for novel approaches related to treat pain. The nerve growth factor, NGF,2 is one of the most powerful endogenous substances which elicit pain and inflammation via the tyrosine kinase receptor TrkA (3). This neurotrophin stimulates an intracellular cascade that elicits PKC-dependent P2X3 receptor phosphorylation with ensuing facilitation of receptor currents. Conversely, suppression of NGF signaling powerfully down-regulates P2X3 receptor function (4). These observations are consistent with the raised NGF levels in acute or inflammatory pain conditions (3). The molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain, however, unclear.

A dynamic balance between tyrosine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is a major factor controlling the activity of many neurotransmitter receptors (5). TrkA stimulation activates intracellular signaling including Src tyrosine kinases (6) that, in neurons, are important modulators of ligand-gated receptors like nicotinic (7), NMDA receptors (8), and TRPV1 receptors (9). All these receptors are involved in mediating various types of pain in the spinal cord and sensory ganglia. There is, however, no available data on the role of tyrosine phosphorylation on P2X3 receptor function.

The fundamental regulator of Src signaling is the C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) that blocks it via tyrosine phosphorylation (Tyr-527, Refs. 10, 11). We explored whether tyrosine phosphorylation might regulate P2X3 receptors of sensory neurons by focusing on the P2X3 C-terminal domain Tyr-393 residue, which is included in a region with significant similarity with the Csk-phosphorylating region of Src. Our data demonstrate that Csk activation induced an increased tyrosine (Tyr-393 residue) P2X3 receptor phosphorylation with decreased receptor function, observed both in mouse trigeminal sensory neurons as well as a cell expression system. We, thus, propose that Csk-mediated P2X3 receptor inhibition is a novel mechanism to limit overactivation of P2X3 receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Constructs

pCDNA3-P2X3 (rat sequence, NCBI accession number: CAA62594) was provided by Dr. A. North (University of Manchester, UK). pCDNA3-Csk (12) was kindly provided by Dr. X. Y. Huang (Cornell University). pGEX-rat P2X3 C-terminal domain (13) was gently provided by Dr. P. Seguela (McGill University). pCDNA3-P2X3 or pGEX-P2X3 mutants were obtained using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the following primers: Y393A 5′-GACTCAGGGGCCGCTTCTATTGGTCACTAG-3′; Y393F 5′-GACTCAGGGGCCTTTTCTATTGGTCACTAG-3′; E384A 5′-TTCACCAGCGACGCGGCCACAGCGGAG-3′ and Q380A 5′-CAGGCCACAGCGGCGAAGCAGTCCACCGAT-3′. Correct mutagenesis was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing, while correct expression was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy experiments and Western blotting.

Cell Cultures and Transfection

Primary cultures of trigeminal ganglion neurons from C57-Black mice (12–14 days old) were cultured as described and used 24 h after plating (4). The following substances were added to the culture medium as required: anti-NGF neutralizing antibody (6 μg/ml, 1:5000; Sigma; 4); NGF (50 ng/ml; Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel), H89 (10 μm, Sigma), forskolin (10 μm, Sigma). Inhibitors were pre-applied for 30 min to serum-starved cultures. To block tyrosine phosphatases, living cells were incubated with sodium pervanadate (50 μm Na3VO4, Sigma) for 10 min at 37 °C (9, 14).

Transient transfection of pCDNA3-P2X3 receptors in HEK293T cells was carried out with calcium/phosphate method. Mock transfection was obtained with co-transfected with pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

C-terminal P2X3 peptides (amino acid residues 346–397) were used for in vitro kinase assay. Reactions were performed using 1 μg of substrate peptide and 1 μg of recombinant kinase GST-Csk (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. pGEX-P2X3 peptides were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells (GE Healthcare, Uppsala Sweden) and purified with a GST SpinTrap Purification module (GE Healthcare). The quality and quantity of input target peptides were checked with SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Activity of the commercial recombinant Csk was determined by the Supplier (Cell Signaling) using a radiometric method in a kinase dose-dependent assay based on Csk HTScanTM kit (Cell Signaling).

Protein Analysis, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

Trigeminal cultures were lysed in ODG buffer (2% n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 100 mm NaF, 20 mm orthovanadate) plus protease inhibitors mixture (Complete, Roche Applied Science). For phosphorylation studies, proteins were extracted in ODG buffer, immunopurified in TNE buffer (10 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA plus 100 mm NaF, 20 mm orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors) with rabbit anti-P2X3 or anti-Csk antibodies (0.5 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and pull down with protein A/G PLUS-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 4 h at 4 °C. For co-immunoprecipitation, proteins were extracted in the presence of 1% Triton X-100. Membrane protein biotinylation experiments were performed as previously described (4). Total cellular membranes were purified by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C (14). Samples were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gel and processed for Western immunoblotting using the following antibodies: anti-P2X3 (1:300; Alomone), anti-Csk (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Src-p527 (1:500; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-tyrosine horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated (1:3500; clone Y20; Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy). To avoid detection of immunoglobulin heavy chains in Western blot, a mouse anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Suffolk, UK) was used as secondary antibody.

Quality and correct reactivity of anti-Csk, anti-Src-p527 and anti-Src-p416 antibodies were tested analyzing with Western immunoblotting HEK protein lysates after Csk overexpression cells (not shown, 15).

Loading controls were performed processing total lysates with Western immunoblotting or stripping (RestoreTM, Pierce) and successive probing. Western blot signals were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence light ECL (GE Healthcare). For quantification, band density was measured using Scion Image software.

Co-immunofluorescence and Microscopy

Paraformaldehyde fixed trigeminal neurons were processed with a guinea pig anti-P2X3 antibody (1:400, Neuromics, Edina, MN) and a rabbit anti-Csk antibody (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or a rabbit anti-phospho-Src527 antibody (1:50, Cell Signaling). Immunofluorescence reactions were visualized using suitable AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies, or, for triple immunofluorescence reactions, with biotinylated antibody and streptavidin-AlexaFluor647-conjugated (1:500, Invitrogen). Cells stained with secondary antibodies only, showed no immunostaining. Membrane in vivo labeling was obtained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) AlexaFluor488-conjugated (1:200, Invitrogen). Specimens were observed with a confocal Leica TCS SP5 microscope (Ar-He, Ne laser). Quantitative analysis was obtained with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). Data are the mean of at least five independent experiments where an average of 260 cells was analyzed.

RNA Silencing

For siRNA experiments, trigeminal neurons (from 2 mouse) or HEK293 cells (5 × 104 cells/well in 12-well plate) were transfected, respectively, with mouse or human Csk siRNA SmartPools (100 nm, Dharmacon RNAi Technology, Lafayette, CO) using the DharmaFECTTM-1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). For transfection efficiency control, cells were transfected with scramble RNA and siGLO RISC-Free siRNA (Dharmacon). Efficiency of Csk silencing was tested with Western immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. 24 h after silencing HEK cells were transfected with pEGFP or pCDNA3-P2X3 plasmids and analyzed 48 h later.

Patch Clamp Recording

Trigeminal neurons or HEK cells were recorded in whole-cell configuration as described (4). Intracellular solution of recording pipette contained (in mm): 140 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 2 Mg2ATP, 2 GTP, 10 HEPES, and 10 EGTA (pH 7.2). Cells were continuously superfused (2 ml/min rate) with physiological solution containing (in mm): 152 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4).

Responses to selective P2X3 receptor agonist α,β-methylene-ATP (α,β-meATP, resistant to ectoATPase hydrolysis, Sigma) were measured in terms of peak amplitude. To express agonist potency in terms of concentration producing 50% of the maximum response (EC50 values), dose-response curves for α,β-meATP were constructed by applying different agonist doses to the same cells and fitting them with a logistic equation (Origin 6.0, Microcal, Northampton, MA). The onset of desensitization was estimated by calculating the first time constant of current decay (τfast) in the presence of agonist in accordance with our previous reports. Recovery from desensitization was assessed by paired-pulse experiments (4).

Computational Modeling and Src Family Sequence Alignment

To perform the sequence alignment, 346–397 amino acid residues of C-terminal portion of the rat P2X3 receptor (CAA62594) were aligned with the C-terminal amino acid residues 478–533 of Src (Q9JJ10) involved in Csk/Src interaction. To this aim, we used ClustalW and T-COFFEE algorithms (16, 17). After this step, computational homology modeling, in silico P2X3-Csk docking and alanine scanning were performed to identify candidate residues suitable for mutagenesis within the putative Csk-docking site of the P2X3 domain. Details are provided as supplemental information. Accordingly to computational predictions, we mutated potential residues (Gln-380 and Glu-384) in P2X3 sequence that might destabilize Csk-P2X3 C-terminal complex and we explored the consequences using Csk in vitro kinase assays.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± S.E., where n indicates the number of experiments in molecular biology/immunocytochemistry or the number of investigated cells in electrophysiology. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test, the Mann-Whitney rank sum test or the ANOVA test, as appropriate. A p value of ≤0.05 was accepted as indicative of a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Csk-mediated P2X3 Receptor Phosphorylation Leads to Down-regulation of Receptor Function

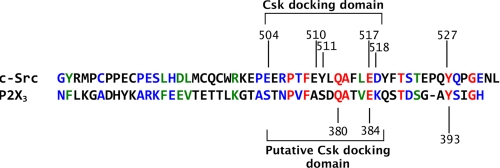

The tyrosine kinase Src is negatively controlled by the C-terminal Src kinase, Csk, via its docking to the Src C-terminal residues 504–518 (Fig. 1; 11, 18). By exploring the C-terminal region of the P2X3 receptor, we could identify a sequence homologous to the C-terminal portion of Src specifically binding Csk (40% homology, 33.3% identical residues and 6.7% strongly similar residues, Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

Similarity of C-terminal domains of P2X3 and of c-Src. Amino acid alignment of C-terminal domains of P2X3 and c-Src, natural substrate of Csk, was examined. Note alignment of Src Tyr-527 and P2X3 Tyr-393 residues. The Src/Csk docking domain and residues involved in the docking are indicated. Identical (red), strongly similar (green), and weakly similar (blue) residues are indicated. Within this domain, Src/P2X3 identical residues correspond to 33.3%, while 6.7% residues are strongly similar, and 26.7% residues are weakly similar. The Q380A and E384A residues important for Csk docking on P2X3 have been indicated.

In particular, the P2X3 C-terminal Tyr-393 residue, a residue specific for the P2X3 subtype and is not conserved in the other P2X family members, appeared fully aligned with the target of Csk, Src Y527. Furthermore computational modeling (19) suggested also similar accessibility of these residues to the solvent, rendering them suitable targets to a similar kinase.

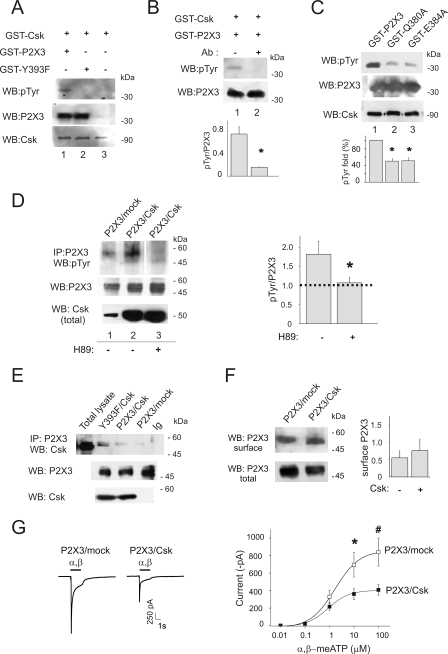

These observations prompted us to examine if P2X3 Tyr-393 was a target for Csk activity. Hence, we performed a cell-free in vitro kinase assay plus a Western blotting with phosphotyrosine antibodies. Using recombinant Csk and GST-P2X3 C-terminal domain purified from E. coli, we observed P2X3 tyrosine phosphorylation (n = 5; Fig. 2A, lane 1). This signal was not detectable when the same assay was run in the presence of a P2X3 antibody recognizing the P2X3 peptide 383–397 (n = 3, Fig. 2B, lane 2) or when GST-P2X3Y393F mutant was tested as substrate (n = 5, Fig. 2B, lane 3), demonstrating thus that P2X3 Tyr-393 was a target for Csk phosphorylation in vitro. Furthermore, following our computational modeling data, we performed mutagenesis of the specific P2X3 residues Q380A and E384A within the P2X3 region compatible with putative Csk docking (residues 371–386, see Fig. 1). This approach should help to explore Csk docking to the P2X3 subunits as suggested by the in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 2C). These experiments demonstrated a significantly reduced phosphorylation of mutants Q380A and E384A (50.2 ± 6.6%; and 51 ± 8.1% respectively, taken 100% wt signal, n = 3, Fig. 2C, lanes 2 and 3) in comparison with wt (lane 1), thus, supporting the existence of a Csk docking site on the P2X3 receptor C-terminal domain.

FIGURE 2.

Csk interaction with P2X3 subunits in HEK cells yields increased receptor phosphorylation and decreased function. A, in vitro kinase assay of GST-Csk and C-terminal P2X3 domain wt (GST-P2X3) or Y393F (GST-P2X3-Y393F). In vitro P2X3 tyrosine phosphorylation was visualized with Western blot and anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Input of recombinant P2X3 is shown (bottom lanes). B, neutralization of Csk activity was obtained with polyclonal anti-C-terminal P2X3 antibodies (lower panel, lane 2 and histogram, *, p = 0.03). wt signal 0.52 ± 0.15 AU, n = 5; wt plus peptide 0.17 ± 0.015 AU, n = 3; Y393F mutant 0.13 ± 0.015 AU, n = 5. C, in vitro kinase assay of GST-Csk and C-terminal P2X3 domain wt (GST-P2X3) or mutants (GST-P2X3-Q380A and GST-P2X3-E384A) visualized with Western blot and anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Input of recombinant P2X3 is shown (bottom lanes). D, Western immunoblots using an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody on immunopurified P2X3 receptors. P2X3 receptor phosphorylation increases with respect to mock cells (lane 1) when P2X3 is co-expressed together with Csk (lane 2). No co-immunopurification of Csk and P2X3 receptor was observed in these conditions. H89 (10 μm; 30 min) blocks P2X3 receptor phosphorylation (lane 3). Middle and bottom lanes show total P2X3 and Csk expression. Histograms show P2X3 phosphotyrosine levels (n = 4, *, p = 0.05). Values are normalized with respect to the P2X3 input signals. E, examples of Csk/P2X3 co-immunopurification show association between these two proteins in P2X3 and Csk co-expressing HEK cells (n = 3). Note higher co-purification levels when P2X3 receptor Y393F mutant is expressed (lane 2). P2X3 protein input used in immunoprecipitation is shown in the lower panel. F, membrane protein biotinylation and Western immunoblotting reveal the amount of P2X3 receptor expressed at the cell membrane level in HEK cells mock-transfected or transfected with Csk. Histograms show values normalized versus total P2X3 receptors (0.55 ± 0.21 AU for P2X3/mock and 0.75 ± 0.34 AU for P2X3/Csk expression, n = 3, p > 0.05). G, representative examples of currents induced by α,β-meATP (α,β, black bar) on HEK cells expressing P2X3 and mock plasmid or P2X3 together with Csk. Note smaller current amplitude after P2X3/Csk co-expression. The right panel shows dose-response curves for α,β-meATP-evoked currents in the two experimental conditions (P2X3 receptor plus mock plasmid, open squares; n = 10; co-expression of P2X3 plus Csk, filled squares; n = 10, *, p = 0.02 and #, p = 0.05). Note that co-expression of Csk depresses the P2X3- mediated current.

Co-expression of full-length P2X3 receptors together with Csk in HEK cells was therefore carried out to investigate functional consequences of receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. Csk and P2X3 co-transfection led to robust co-expression of both proteins (Fig. 2D, lane 2) with a significant increase in P2X3 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2D, lane 2; n = 5). In accordance with the notion that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Csk is essential to enable this kinase activity (20), we observed that, in HEK cells, the PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μm; 30 min) prevented P2X3 tyrosine phosphorylation (10 μm; 30 min; Fig. 2D, lane 3, n = 4). It is noteworthy that basal adenylyl cyclase in these cells was sufficient to trigger activation of endogenous Csk, since H89 suppressed basal P2X3 tyrosine phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. S2A).

In basal condition, a small portion of Csk and P2X3 receptor interacted at cellular level, as observed by weak P2X3/Csk co-immunoprecipitation in HEK cells (Fig. 2E, lane 3). However, the co-immunoprecipitation signal was strongly detected when using the Y393F mutant (Fig. 2E, lane 2) despite the lack of phosphorylation (see Fig. 2A, lane 2). These data suggested that Csk and P2X3 receptors are part of a complex; however, highly dependent by phosphorylation state and conformation.

Whole-cell patch clamp experiments on HEK cells co-transfected with Csk and P2X3 indicated that P2X3 receptor-mediated currents evoked by the selective agonist α,β-meATP (≥10 μm) were significantly (p = 0.02 for 100 μm, p = 0.05 for 10 μm) smaller than those recorded from cells expressing the P2X3 alone (Fig. 2G; n = 10), although this effect was not associated with a significant variation in membrane receptor expression (n = 3, p > 0.05; Fig. 2F). Such smaller receptor responses were not accompanied by changes in the agonist EC50 value (indicative of drug receptor affinity, Table 1), in the Hill coefficient (indicative of the stoichiometry of drug receptor interaction, Table 1) or in the time constant of current decay (indicative of desensitization onset, 101 ± 8 ms for control versus 126 ± 10 ms for P2X3/Csk co-expression; n = 17 and 13, respectively). Likewise, no significant changes were observed in terms of P2X3 current recovery from desensitization (tested with a double agonist pulse application, 4) in the presence (58 ± 5% of the previous response; n = 8) or in the absence of Csk (60 ± 4% of the previous response, n = 18).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of P2X3 receptors and its Tyr-393 mutants

The table shows the kinetic properties of P2X3 receptors and its 393 mutants.

| Receptor | EC50 | Hill coefficient | Na |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | |||

| P2X3 wt | 2.05 ± 0.47 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | 10 |

| Wt/Csk | 1.74 ± 0.51 | 1.05 ± 0.13 | 10 |

| Y393A | 1 ± 0.21 | 1.24 ± 0.16 | 13 |

| Y393F | 1.56 ± 0.66 | 0.89 ± 0.16 | 6 |

| Y393A/Csk | 1.02 ± 0.25 | 1.23 ± 0.14 | 12 |

| Wt siRNA mock | 2.44 ± 0.92 | 1.10 ± 0.42 | 6 |

| Wt siRNA Csk | 1.67 ± 0.34 | 1.21 ± 0.42 | 10 |

a N indicates the number of neurons tested for these analyses.

Globally, our results suggest that Csk phosphorylated P2X3 receptors in cells and in vitro that was associated with decreased receptor function, when tested with high agonist concentrations, without concomitant alteration in receptor kinetic properties.

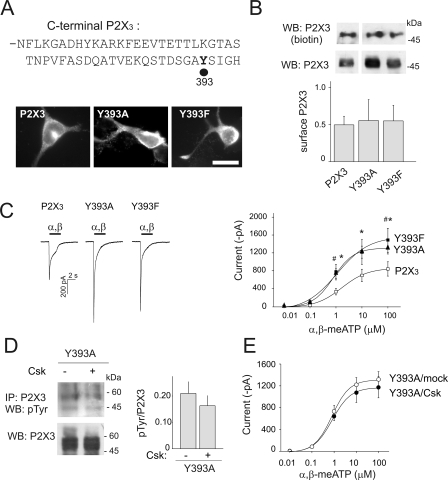

P2X3 Tyr-393 Receptor Mutants Are Insensitive to the Action of Csk in HEK Cells

Because Tyr-393 appeared to be the Csk target in the in vitro assays, we mutated this residue to explore its functional consequences with patch clamp recording from transfected HEK cells. Despite similar expression observed with immunofluorescence microscopy and membrane biotinylation assay (Fig. 3, A and B), the current amplitude evoked by α,β-meATP (100 μm) was larger in the P2X3 Y393A and Y393F mutants than in wt receptors (see examples and average data in Fig. 3C). The agonist dose response curves for P2X3 mutants displayed enhanced maximal effect, even though similar EC50 values suggested analogous agonist affinity (Table 1). Co-expression of the P2X3 mutants with Csk did not showed significant changes either in receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (n = 3, Fig. 3D) or current amplitude (Fig. 3E, n = 13). These data suggest that Tyr-393 was important to exploit the Csk modulation of P2X3 receptor functional response in an in vitro expression system.

FIGURE 3.

C-terminal P2X3 receptor Tyr-393 residue is sufficient to control receptor properties and sensitivity to Csk. A, examples of HEK cells expressing the wt P2X3 receptors or the mutated forms Y393A or Y393F. Calibration bar: 10 μm. B, membrane protein biotinylation and Western blot reveal wt or mutants P2X3 receptor expression at cell membrane level (see histograms, values normalized versus total P2X3 receptors; n = 6, 3 or 5). C, representative examples of currents induced by α,β-meATP (α,β, black bar, 100 μm) and dose-response curves obtained from HEK cells expressing wt P2X3 receptors (open squares; n = 10) or Y393A or Y393F mutants (filled triangles and filled squares, respectively; n = 13 or 6; for 100 μm: p = 0.03, #, p = 0.05; for 10 μm: *, p = 0.01; for 1 μm: *, p = 0.008, #, p = 0.01). Note larger current amplitude for both mutated receptors. D, example of Western immunoblots of immunopurified Y393A receptor expressed alone or together with Csk. Bottom lanes show input of P2X3 levels. Histograms quantify tyrosine phosphorylation levels in the Y393A mutant when expressed with or without Csk (0.21 ± 0.04 and 0.16 ± 0.03 AU for tyrosine phosphorylation signals in the absence and in the presence of Csk co-expression, respectively, n = 3). Experiments performed with the Y393F mutant showed similar results (0.4 + 0.23 and 0.32 + 0.14 AU for tyrosine phosphorylation in the absence and in the presence of Csk, respectively, n = 4). E, dose-response curves for α,β-meATP evoked currents of Y393A receptors expressed a with mock plasmid (filled circles, n = 13) or together with Csk (open circles, n = 12).

NGF Neutralization Activated Csk in Trigeminal Neurons

To understand the physiological implications of the interaction between Csk and P2X3 receptors, we studied mouse trigeminal sensory neurons that constitutively express P2X3 receptors potently modulated by NGF: indeed, NGF neutralization decreases trigeminal pain in vivo and P2X3 receptor currents in neuronal cultures (4). It seemed, therefore, interesting to investigate the potential contribution by Csk signaling to the action of NGF.

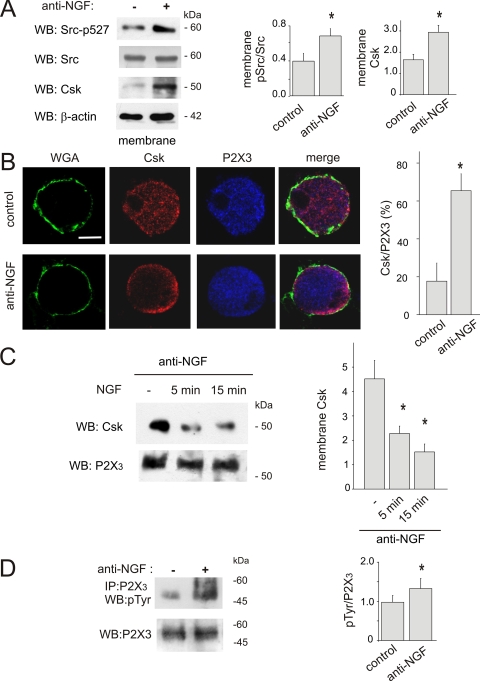

On trigeminal sensory neurons cultured in the presence of anti-NGF antibodies (4), membrane expression of Csk was significantly enhanced by NGF neutralization (Fig. 4A) together with a stronger Csk activity as demonstrated by concomitant Src inhibition (see anti-phospho-Src527 antibody and Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Neutralization of NGF activates Csk in mouse trigeminal neurons. A, purified membrane extracts from trigeminal neurons grown in control conditions or after application of anti-NGF antibody, tested with anti-Csk or anti-phospho-Src527 antibodies. The amount of total Src in membrane preparation is shown. Loading control was done with anti-β-actin antibody. Histograms show quantification of Western blot for Csk or Src527 optical density values (n = 5 experiments, *, p = 0.04 and *, p = 0.02, respectively). Signals of Src-p527 are normalized with respect to total Src. B, confocal images show cellular immunoreactivity of Csk (red) in control conditions (upper panels) and in the absence of NGF (lower panels). Membrane staining was obtained with in vivo labeling with WGA (green). Note Csk re-localization at membrane level after NGF neutralization. P2X3 receptors immunoreactivity (blue) was also shown. Calibration bar: 5 μm. Histograms quantify neurons with ring-like localization of Csk as percent of total of P2X3 immunoreactive neurons (n = 60 or 68 cells, *, p = 0.02). A total of twenty optical stack sections for each cell were analyzed (at 1-μm interval). C, decrease in Csk membrane localization after acute NGF (100 ng/ml, 5 or 15 min) applied to NGF-deprived (24 h) cultures. Amount of input P2X3 is also shown. Histograms show quantification of the effect in the different conditions (from 4.5 + 0.75 AU versus 2.28 + 0.30, *, p = 0.03, n = 4 after 5 min of NGF application or versus 1.52 + 0.32 AU, p = 0.02 n = 3 after 15 min of NGF application, n = 3 for 15 min NGF; *, p = 0.03). D, Western immunoblots of immunopurified P2X3 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (pTyr) from trigeminal cultures grown (24 h) in control conditions (lane 1) or after applying the anti-NGF antibody (lane 2). P2X3 inputs are shown (bottom lanes). Histograms show pTyr values expressed normalized with respect to the P2X3 input signal (0.79 ± 0.1, AU in control, n = 10, versus 1.17 ± 0.12 AU after anti-NGF, n = 9; *, p = 0.03).

To further validate Csk activation we examined, as a reliable index of this process, Csk translocation to the neuronal membrane (21). Confocal microscopy showed, after NGF neutralization, redistribution of Csk to membrane (Fig. 4B). Quantification of microscopy experiments showed a significantly larger number of P2X3 receptor expressing neurons with a ring-like distribution of Csk (Fig. 4B, p = 0.009). Conversely, rapid disappearance of membrane-bound Csk was induced when exogenous NGF (100 ng/ml for 5 or 15 min) was applied to anti-NGF antibody-treated mouse trigeminal neurons (p = 0.02 n = 3, Fig. 4C), indicating a close relation between extracellular NGF levels and Csk location at the membrane level.

Following neutralization of extracellular endogenous NGF with anti-NGF antibodies (24 h, 4), mouse trigeminal neurons showed a large increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of their P2X3 receptors (p = 0.03, Fig. 4D). The effects of NGF deprivation on P2X3 phosphorylation in culture were even more evident following tyrosine phosphatase inhibition with pervanadate (250 μm; 25 min; 0.79 ± 0.1 AU in control versus 2.24 ± 0.58 AU after pervanadate; n = 3; p < 0.001), suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation rather than dephosphorylation was an important mechanism for the action by Csk on P2X3 receptors. On mouse trigeminal neurons, application of H89 (10 μm; 30 min) induced a slight increase of the constitutive N-terminal threonine phosphorylation of P2X3 receptors (0.24 ± 0.02 absolute gray levels for control and 0.26 ± 0.003 after H89 treatment, n = 3; supplemental Fig. S2B) previously described as attributed PKC activity (4). These results cannot exclude that, on trigeminal neurons, PKC or PKA should exert, at least partially, distinct and contrasting effects of the threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation state of P2X3 receptors.

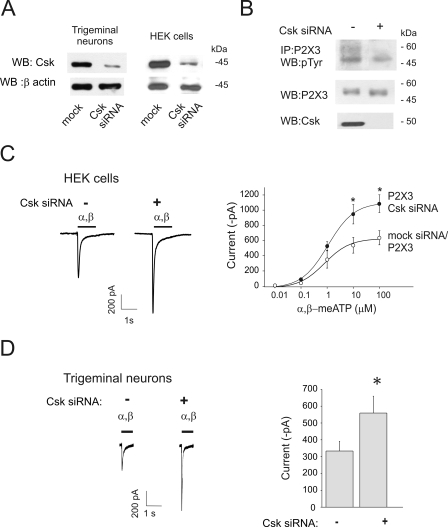

Role of Endogenous Csk on P2X3-mediated Currents of HEK Cells and Trigeminal Neurons

We tested the hypothesis that endogenous Csk exerts a constitutive control over P2X3 receptor function. Because transgenic mice lacking Csk are not vital (22), we examined our hypothesis by silencing Csk in HEK cells as well as in mouse trigeminal neurons (Fig. 5). Immunofluorescence and Western blotting demonstrated efficient silencing of Csk in HEK and in trigeminal ganglion cultures (n = 3, Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. S2B).

FIGURE 5.

Endogenous Csk has a constitutive inhibitory role on P2X3 receptors. A, Western blots showing very low expression of Csk after Csk siRNA in trigeminal neurons and HEK cells. Loading control is confirmed by β-actin signals (bottom lanes). B, example of Western blot showing tyrosine phosphorylation (pTyr) of P2X3 receptors in relation to silencing. After Csk siRNA, there is no change in total P2X3 receptor signal, disappearance of Csk and minimal pTyr of the P2X3 subunits. C, representative examples of currents induced by α,β-meATP (α,β, black bar, 100 μm) and dose-response curves from HEK cells expressing wt P2X3 receptors in control conditions (open circles; n = 11) or after Csk siRNA (filled circles; n = 6) that enhances responses to α,β-meATP, revealing background depression by endogenous Csk (*, p = 0.02 at 100 μm; *, p = 0.04 at 10 μm). D, α,β-meATP (α,β, 10 μm) evoked currents recorded from trigeminal neurons after mock (n = 29) or Csk silencing (n = 24). Histograms show quantification of mean current amplitude values (333 ± 57 pA for control n = 29 cells; 559 ± 100 pA for Csk siRNA, n = 24 cells; *, p = 0.04).

Western blotting with a phosphotyrosine antibody demonstrated that, in P2X3-expressing-HEK cells, there was no increase in P2X3 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation after silencing endogenous Csk (Fig. 5B), together with a significant rise in the maximal amplitude of the α,β-meATP-evoked current with respect to responses measured from mock silenced cells (p = 0.04 for 10 μm and p = 0.02 for 100 μm α,β-meATP, Fig. 5C). To explore any potential activity of residual Csk left after silencing in HEK cells, we decided to maximize the cAMP/PKA-mediated stimulation of endogenous residual Csk with forskolin application (10 μm, 5 min; known to be a strong Csk activator; Ref. 23) to either mock or siRNA-transfected HEK cells. Under these conditions, no significant change in P2X3 receptor phosphorylation or receptor current was found (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting efficient silencing of endogenous Csk.

We next tested the consequences of Csk silencing on the responses of P2X3 receptors of trigeminal neurons (Fig. 5D). Under these conditions, controlled experiments run in parallel with neurons treated with siRNA Csk or control non-targeting siRNA showed that the current amplitude evoked by 10 μm α,β-meATP was significantly larger after Csk silencing (n = 29 in control and n = 24 cells for Csk siRNA; p = 0.04; Fig. 5D). These data indicate that endogenous Csk was essential to curtail constitutive, functional overactivation of P2X3 receptors in an expression system and in trigeminal neurons.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of the present study is the demonstration that the kinase Csk exerted a powerful inhibitory control on the function of P2X3 receptors via phosphorylation of the P2X3 Tyr-393 residue. These data shed light on a new mechanism that controls the efficiency of signaling by pain-sensing P2X3 receptors. It is tempting to speculate that Csk activity represents a key endogenous brake to avoid inappropriate pain transduction.

Multiple Phosphorylation Processes Control the Operation of P2X3 Receptors in Trigeminal Neurons

In analogy with other ionotropic receptors (24), phosphorylation of P2X3 receptors is a mechanism to modulate how effectively this protein can sense its ligands (4). In keeping with this notion, we have recently shown that NGF enhances PKC-mediated threonine phosphorylation of P2X3 receptors with resulting gain of function (4). Less common is, however, to observe phosphorylation mechanisms to depress receptor activity. The present study has indicated, for the first time, how an important contribution to the NGF-mediated action on P2X3 receptor function was the modulation of Csk activity. Furthermore, native P2X3 receptors of trigeminal neurons generated significantly larger membrane currents after Csk silencing, confirming that these receptors were kept under constitutive inhibition by this kinase activity. Because anti-NGF treatment produces mouse trigeminal analgesia in vivo (4), depression of P2X3 receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation could contribute to lessened pain, despite unchanged receptor expression. In general, our data extend the role of Csk as a negative regulator of pain, because Csk would also inhibit the Src-mediated facilitation of TRPV1 (9) and NMDA (8) receptors that are important contributors to pain sensitivity.

Interaction of Csk with P2X3 Receptors

Co-purification of Csk and P2X3 subunits as well as in vitro kinase assay demonstrated that a certain fraction of receptors directly interacts with Csk. Nevertheless, because Csk recognizes a tertiary structure of intracellular domains without a common consensus sequence (25), it was difficult a priori to demonstrate a discrete site for Csk binding. Starting from the sequence alignment between P2X3 and the Csk target domain of Src (11), we detected a compatible Csk binding region in the P2X3 C-tail. When we mutated the key P2X3 residues Q380A and E384A within the region compatible with Csk docking, the in vitro Csk-mediated phosphorylation was prevented. The weak phosphorylated signal for the wt P2X3 C-terminal domain in comparison with total substrate available was likely to be due to the absence of the complete receptor conformation obtainable only under in vivo conditions. Furthermore, although very few non-Src targets for Csk have been reported (26), we cannot completely exclude other indirect mechanisms coexisting in neurons to explain Csk-mediated P2X3 phosphorylation. For instance, certain signaling elements (or adaptor proteins) of the Src pathways, as well as cytoskeleton elements, could contribute to the action of Csk on P2X3 receptors. Nonetheless, it is unnecessary to assume the role of an unknown kinase in P2X3 phosphorylation because P2X3 receptors exhibited poor tyrosine phosphorylation after Csk silencing, a condition that should have per se hyper-activated other Src family kinases (27). Furthermore, P2X3 receptor tyrosine hyperphosphorylation and reduced functional activity were observed even after pharmacological inhibition of phosphatases, suggesting that P2X3 receptors displayed regulatory mechanisms distinct from other purinergic receptors, like P2X7 (28).

The Csk-mediated reduction of P2X3 receptor function was observed when a substantial fraction of receptors was activated. In analogy with P2X2 receptors (29), one might speculate that phosphorylation of trimeric P2X3 receptors could change the overall electrical charge of this domain, leading to a receptor conformation associated with impaired channel function and efficacy.

The Csk-mediated control over the P2X3 current amplitude was unlikely to be caused by concomitant changes in receptor sensitivity because of the unchanged threshold and slope of the agonist dose response plots. Likewise, no alteration in desensitization kinetics was detected, suggesting that the modulatory role of Csk was different from the one seen, for example, with the peptide NGF (4). In view of the well known compartmentalization of Csk and Src to membrane lipid rafts (30), it is feasible to presume that already described discrete redistribution of P2X3 receptors between rafts and non-raft domains (31) might determine the efficiency of the global cell response to the P2X3 agonist.

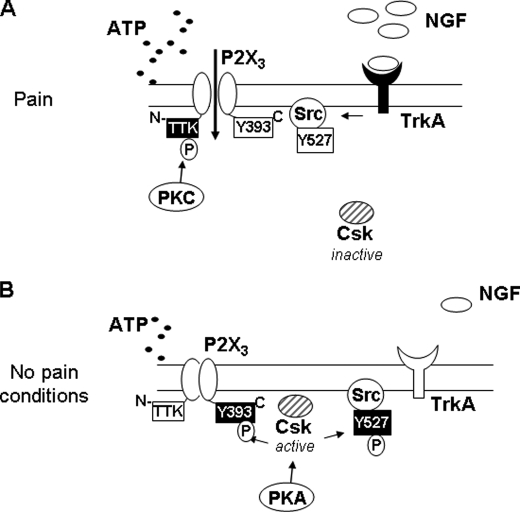

A New Role for the P2X3 Receptor C-terminal Residue Tyr-393

Electrophysiological studies indicate the high sensitivity of the P2X receptor family to sequence alterations because point mutations of conserved or nonconserved residues generate dramatic differences in receptor function (32). In the present study, the tyrosine residue Tyr-393, nonconserved among the P2X family members, was a gain setter for the P2X3 receptor function. Mutating this residue rendered the receptor insensitive to the depressant action of Csk and limited P2X3 tyrosine phosphorylation, suggesting that the Tyr-393 residue was a target for Csk, necessary and sufficient for its activity on P2X3 receptors (see model in Fig. 6, A and B). To the best of our knowledge, this is the only available example of a powerful gain of function of P2X3 receptors with a single amino acid mutation of the intracellular domains, without concomitantly altering the receptor kinetic properties.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed mechanism of action of Csk on P2X3 receptors of trigeminal sensory neurons. A, during pain states, excess NGF binds TrkA receptors to stimulate downstream signaling (including PKC), a process that together with enhanced release of ATP, strongly activates P2X3 receptors. PKC-mediated phosphorylation of threonine residues of the N-terminal domain of P2X3 subunit, together with relief of Csk inhibition of P2X3 receptors amplifies functional receptor responses. The outcome of all these effects is an increase in nociceptive neuronal firing and pain. B, under pain-free conditions when levels of ATP and NGF are low, PKA-mediated Csk activity is envisioned to inhibit Src (via Tyr-527 phosphorylation) and to depress P2X3 receptor responses (via Tyr-393 phosphorylation). This process intrinsically limits P2X3 receptor activity.

Under basal conditions, namely the absence of strong stimulation of P2X3 receptors, it is possible to hypothesize that the constitutive activity of PKA was an important factor to ensure Csk-mediated inhibition of P2X3 receptor function (Fig. 6B). During pain states, one might assume that elevated intracellular Ca2+ should facilitate the action of PKA on Csk: however, this is actually unlikely to take place because, under such conditions, strong activation of Src has been reported (8) to imply that Csk had transiently lost its function.

Under such circumstances, the prevailing phosphorylation state of the P2X3 receptor is proposed to be PKC-mediated (Fig. 6A) with facilitation of the receptor currents. Indeed, the possibility of mutually exclusive effects of PKA and PKC on the P2X3 phosphorylation state and functional responses makes these kinases as potentially attractive yin and yang regulators of pain sensitivity (Fig. 6, A and B).

A Scheme for Regulation of P2X3 Receptors by Tyrosine Kinase

In chronic pain states, the strong activation of P2X3 receptors by large concentrations of ATP (2) is potentiated by algogenic substances like NGF (34) via complex multifactorial pathways that, as shown in the present study, include relief of Csk-mediated constitutive P2X3 inhibition (Fig. 6).

Because ATP-activated P2X3 receptors transduce acute (mechanical) and chronic (neuropathic) painful stimuli to the brain (33), inappropriate activation of this system may evoke pain hypersensitivity (hyperalgesia) even to non-painful stimuli (allodynia), a condition typical of severe pain disorders, including trigeminal neuralgia. If Csk is one endogenous inhibitor of P2X3 receptor signaling, manipulating Csk activity could promise a novel approach to pain suppression. This is an attractive hypothesis since Csk can target strong responses mediated by P2X3 receptors. The outcome of the action of Csk would be to create a low-pass filter for less painful stimuli that could be normally relayed without altering the sensory system gain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Seguela for pGEX plasmid, P. Mager for structural modeling data of P2X3 receptors, and A. Gnanasekaran, R. Abbate, and the staff of Centro Servizi Polivalenti di Ateneo (University of Trieste) for help.

This work was supported by grants from the Telethon Foundation (GGP07032), the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT), Fondi per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base project (to A. Nistri), and the Slovenian Research Agency ARRS project (to E. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and information.

- NGF

- nerve growth factor

- α,β-meATP

- α,β-methylene-ATP

- AU

- arbitrary units

- Csk

- C-terminal Src inhibitory kinase

- FSK

- forskolin

- ODG

- n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- TrkA

- tyrosine kinase receptor

- wt

- wild type

- PKA

- cAMP-dependent kinase

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Souslova V., Cesare P., Ding Y., Akopian A. N., Stanfa L., Suzuki R., Carpenter K., Dickenson A., Boyce S., Hill R., Nebenuis-Oosthuizen D., Smith A. J., Kidd E. J., Wood J. N. (2000) Nature 407, 1015–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnstock G. (2008) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 575–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pezet S., McMahon S. B. (2006) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 507–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Arco M., Giniatullin R., Simonetti M., Fabbro A., Nair A., Nistri A., Fabbretti E. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 8190–8201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalia L. V., Pitcher G. M., Pelkey K. A., Salter M. W. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 4971–4982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abram C. L., Courtneidge S. A. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 254, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charpantier E., Wiesner A., Huh K. H., Ogier R., Hoda J. C., Allaman G., Raggenbass M., Feuerbach D., Bertrand D., Fuhrer C. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 9836–9849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X. J., Gingrich J. R., Vargas-Caballero M., Dong Y. N., Sengar A., Beggs S., Wang S. H., Ding H. K., Frankland P. W., Salter M. W. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 1325–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X., Huang J., McNaughton P. A. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 4211–4223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nada S., Okada M., MacAuley A., Cooper J. A., Nakagawa H. (1991) Nature 351, 69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinson N. M., Seeliger M. A., Cole P. A., Kuriyan J. (2008) Cell 134, 124–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowry W. E., Huang J., Ma Y. C., Ali S., Wang D., Williams D. M., Okada M., Cole P. A., Huang X. Y. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 733–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernier L. P., Ase A. R., Chevallier S., Blais D., Zhao Q., Boué-Grabot E., Logothetis D., Séguéla P. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 12938–12945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna S., Roy S., Park H. A., Sen C. K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23482–23490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S. Q., Yang W., Kontaridis M. I., Bivona T. G., Wen G., Araki T., Luo J., Thompson J. A., Schraven B. L., Philips M. R., Neel B. G. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesk A. M. (2002) Introduction to Bioinformatics, pp. 160–215, Oxford, NY [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowan-Jacob S. W., Fendrich G., Manley P. W., Jahnke W., Fabbro D., Liebetanz J., Meyer T. (2005) Structure 13, 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mager P. P., Weber A., Illes P. (2004) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 4, 1657–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahamsen H., Vang T., Taskén K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17170–17177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawabuchi M., Satomi Y., Takao T., Shimonishi Y., Nada S., Nagai K., Tarakhovsky A., Okada M. (2000) Nature 404, 999–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imamoto A., Soriano P. (1993) Cell 73, 1117–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vang T., Torgersen K. M., Sundvold V., Saxena M., Levy F. O., Skålhegg B. S., Hansson V., Mustelin T., Taskén K. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 193, 497–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smart T. G. (1997) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7, 358–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D., Huang X. Y., Cole P. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2004–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumeister U., Funke R., Ebnet K., Vorschmitt H., Koch S., Vestweber D. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1686–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nada S., Yagi T., Takeda H., Tokunaga T., Nakagawa H., Ikawa Y., Okada M., Aizawa S. (1993) Cell 73, 1125–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim M., Jiang L. H., Wilson H. L., North R. A., Surprenant A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6347–6358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujiwara Y., Kubo Y. (2006) J. Physiol. 576, 135–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oneyama C., Hikita T., Enya K., Dobenecker M. W., Saito K., Nada S., Tarakhovsky A, Okada M. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 426–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vacca F., Giustizieri M., Ciotti M. T., Mercuri N. B., Volonté C. (2009) J. Neurochem. 109, 1031–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vial C., Roberts J. A., Evans R. J. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnelly-Roberts D., McGaraughty S., Shieh C. C., Honore P., Jarvis M. F. (2008) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324, 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giniatullin R., Nistri A., Fabbretti E. (2008) Mol. Neurobiol. 37, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.