Abstract

Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 are novel extracellular sulfatases that act on internal glucosamine 6-O-sulfate modifications within heparan sulfate proteoglycans and regulate their interactions with various signaling molecules, including Wnt ligands. Although the Sulfs are multidomain proteins, there is limited information available about how the subdomains contribute to their enzymatic and signaling activities. In this study, we found that both human Sulfs were synthesized as prepro-enzymes and cleaved by a furin-type proteinase to form disulfide-bond linked heterodimers of 75- and 50-kDa subunits. The mature Sulfs were secreted into conditioned medium, as well as retained on the cell membrane. Although the catalytic center resides in the N-terminal 75-kDa subunit, the C-terminal 50-kDa subunit was indispensable for both arylsufatase and glucosamine 6-O-sulfate-endosulfatase activity. We found that the hydrophilic regions of the Sulfs were essential for endosulfatase activity but not for arylsulfatase activity. Using Edman sequencing, we identified furin-type proteinase cleavage sites in Sulf-1 and Sulf-2. Deletion of these sequences resulted in uncleavable forms of Sulfs. The uncleavable Sulfs retained enzymatic activity. However, they were unable to potentiate Wnt signaling, which may be due to their defective localization into lipid rafts on the plasma membrane.

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs)2 are major components of the extracellular matrix/cell surface and regulate a variety of biological phenomena, including cell proliferation, cell migration, and differentiation (1). These effects are mediated through the ability of HSPGs to bind to a diverse repertoire of protein ligands. Among these are morphogens, growth factors, chemokines, and other classes of molecules (2, 3).

HSPGs consist of multiple heparan sulfate (HS) chains covalently linked to a limited set of core proteins. The HS chains contain repeating uronic acid and glucosamine disaccharide units. The binding functions of HSPGs depend on the fine structure of the attached heparan sulfate chains where sulfation modifications occur in four positions (N-, 3-O, and 6-O of glucosamine and 2-O of uronic acid) in highly variegated, yet highly regulated patterns (3, 4). 6-O-Sulfation of glucosamine is established to be critical for certain HSPG functions in organisms from Drosophila through mammals (5, 6).

Several years ago, we cloned cDNAs encoding two novel extracellular sulfatases (Sulf-1 and Sulf-2) in human and mouse (7), initiated by the identification of the Sulf-1 ortholog in the quail embryo (QSulf-1) (8). We and others showed that both Sulfs are neutral pH endosulfatases, which remove glucosamine-6-O-sulfate from internal glucosamine residues of highly sulfated subregions within heparin/HSPGs (7, 9, 10). The ability of these enzymes to modulate the heparin/HSPG interactions of a number of growth factors, morphogens, and chemokines has been confirmed in direct binding assays (9, 11–13). In some cellular contexts, the Sulfs act to promote signaling pathways (Wnts, bone morphogenetic protein, and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor) (9–11, 14), whereas in others the Sulfs are inhibitory (fibroblast growth factor-2 and transforming growth factor-β) (15–17). The importance of the Sulfs in development has been revealed by gene knockdown (8) and knock-out studies (11, 18–20). The phenotypes in single and double null mice include abnormalities in general growth, muscle innervation, muscle regeneration, skeletal tissue, and lung development. The Sulfs have been extensively investigated in cancer with some studies consistent with tumor suppression activity (15, 21, 22) and others with a pro-oncogenic role (23–25).

As is the case for the prototypic QSulf-1 (8), HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 consist of four domains from the N to C terminus: a signal peptide, a catalytic domain of 374 amino acids, a basic hydrophilic domain of 346/366 amino acids, and a C-terminal domain of 109/127 amino acids (7, 8). In the 17-member sulfatase family (26), the Sulfs share the most extensive sequence homology with lysosomal glucosamine-6-sulfatase in the catalytic and C-terminal domains, although the centrally inserted hydrophilic domain is absent from this enzyme and other sulfatases. Limited information has been available about the proteolytic processing of the Sulfs during synthesis. In the present study, we show that the mature form of each human Sulf consists of a heterodimer of 75- and 50-kDa subunits, which is formed through the action of a furin-type proteinase on a proprotein of 125 kDa. We investigate the structural requirements for the enzymatic and signaling activities of these proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Antibodies

The C-terminal His-tagged versions of human Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 in pcDNA3.1/Myc-His(−) vector (Invitrogen) have been described (7). The N-terminal FLAG-tagged/C-terminal His-tagged versions of human Sulf-1, Sulf-2, Sulf-1ΔCC, and Sulf-2ΔCC in the pSecTag vector were generated from previously described plasmids (12). The C-terminal truncation mutants of Sulfs in the pSecTag vector were produced by adding a stop codon after amino acids 544 and 538 of Sulf-1 and Sulf-2, respectively, by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). (The first methionine is set as 1 in amino acid numbering.) The hydrophilic domain deletions mutants of Sulfs in the pSecTag vector were generated by deleting amino acids 417–726 of Sulf-1 and 418–716 of Sulf-2 by PCR. The DNA fragments encoding the furin cleavage sites of Sulf-1 (amino acids 539–544 and 571–576) and Sulf-2 (amino acids 533–538 and 560–565) were deleted by PCR to generate the non-cleavable mutants of Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 in the pSecTag vector. D1 refers to the deletion of the first furin cleavage site, D2 to the deletion of the second furin cleavage site, and D1D2 to the deletion of both sites. Wnt1 and Wnt3a plasmids were provided by Dr. Laura W. Burrus, San Francisco State University (27). Wnt3 plasmid was provided by Dr. Jan Kitajewski, Columbia University. Super8XTopFlash, Super8XfopFlash, and RL-CMV were provided by Dr. Randy Moon, University of Washington. Sulf-2 polyclonal antibody H2.3, directed to the HSulf-2 peptide (amino acids 484–504) has been described (24). FLAG antibody (catalog number F3165) was from Sigma. His antibody was from Serotec (catalog number MCA1396). Flotillin antibody was from BD Bioscience (catalog number 610820).

Cell Culture and Transfection

The human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line HS766T and the embryonic kidney cells HEK 293 were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's (DME H21) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The human breast cancer cell line MCF7 was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 10 μg/ml insulin. For transient transfections, FuGENE 6 (Roche, catalog number 11814443001) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Opti-MEM I (Invitrogen) replaced standard growth medium when conditioned medium (CM) was obtained.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

CM was first concentrated on a Amicon Ultra 30K MWCO microconcentrator (Millipore) prior to immunoprecipitation. For cell lysate immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl) in the presence of 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, catalog number P8340). Concentrated CM or cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with appropriate antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C and further incubated for 2 h at 4 °C after adding buffer-equilibrated protein A-agarose beads (Repligen, catalog number IPA400HC). After washing, the samples were electrophoresed on 7.5% SDS gels, followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Problott; Applied Biosystems, catalog number 400994). Reduction was achieved with Tris[2-carboxyethyl]phosphine (TCEP; BondBreaker; Thermo). The membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C in blocking buffer containing 5% nonfat milk in PBST (Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20), incubated with specific antibody in blocking buffer (1:500–1:2000) at room temperature for 2 h, washed three times with PBST, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (eBioscience, catalog number 18-8816) or anti-mouse (eBioscience, catalog number 18-8817) immunoglobulin diluted in blocking buffer (1:1000) at room temperature for 1 h. The proteins were detected using ECL Plus (GE Healthcare, catalog number RPN2132).

Exogenous Furin Digestion and Furin Inhibition Assay

Sulf protein was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates by FLAG or H2.3 antibodies followed by protein A-agarose beads. The beads were washed twice with wash buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mm CaCl2) and resuspended in reaction buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm 2-mercaptoethanol). Each sample was digested with 1 unit of furin (New England Biolabs, catalog number P8077) overnight at 30 °C. For the furin inhibition assay, cells were pretreated with decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (Biomol, catalog number PI-132) Furin inhibitor II (Calbiochem, catalog number 344931) for 3 h. The medium was replaced once with fresh inhibitors and cells were incubated for another 3 h. The medium was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with H2.3.

Arylsulfatase Assay

Recombinant Sulfs were precipitated by FLAG antibody conjugated to protein G beads (BioVision) or nickel beads (Qiagen, catalog number 30210) from CM derived from transiently transfected 293 cells. The resins with bound materials were washed twice with 50 mm HEPES (pH 8.0) and mixed with 10 mm 4-methylumbelliferyl sulfate (4-MUS, Sigma, catalog number M7133) and 10 mm MgCl2 in a total volume of 30 μl. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 100 μl of 0.5 m Na2CO3/NaHCO3 (pH 10.7) to each 30-μl aliquot of the reaction mixture. The fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone was measured in a CytoFluor II multiwell plate reader (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA), with an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm.

TOP/FOP Flash Assay

HEK 293 cells were plated onto 48-well plates as described above. DNA quantities used in transfections were as follows: pcDNA, pcDNA.Wnt1, pcDNA. Wnt3a, pLNC, pLNC.Wnt3 at 0.15 μg/well; pSecTag, pSecTag.Sulf-1, pSecTag.Sulf-1D1D2, pSecTag.Sulf-1ΔCC, pSecTag.Sulf-2, pSecTag.Sulf-2D1D2, and pSecTag.Sulf-2ΔCC at 0.15 μg/well; Super8XTopFlash and Super8XFopFlash at 0.1 μg/well; and RL-CMV at 15 ng/well. Luciferase measurements were carried out in a TD-20/20 luminometer.

Purification and Protein Sequencing of Sulf-1 and Sulf-2

HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with the C-terminal His-tagged versions of human Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 using FuGENE 6. CM (∼15 ml) was collected from three 10-cm dishes after 72 h and clarified by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min. 250 μl of nickel beads (Qiagen) were added to the CM and rotated overnight at 4 °C. Beads were collected in a Poly-Prep column (Bio-Rad) and washed twice with wash buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8). Sulf protein was eluted by elution buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8). The eluted material was separated by electrophoresis on a reducing SDS-7.5% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a Problott membrane. The membrane was stained with Gelcode Blue (Pierce, catalog number 24592) and protein bands were excised and sent to the University of California San Diego Protein Sequencing Facility for N-terminal sequencing.

[35S]HS Chain Digestion Assay

The procedures of Ref. 28 were adapted for this assay. Briefly, 35SO4-labeled heparan sulfate ([35S]HS) was prepared by metabolically labeling 293 cells for 5 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's H-21 medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum and 100 μCi/ml 35SO4 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Cells were lysed in hypotonic 0.25% Triton X-100 in 10 mm NaCl, 100 mm sucrose in 10 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.4) for 20 min on ice. The cell lysate was digested with proteinase K (10 μg/ml) overnight at 55 °C to degrade proteins. After boiling for 10 min, total glycosaminoglycans were precipitated with 3 volumes of 100% ethanol and 5 μg of dermatan sulfate (Sigma, catalog number C3788) at −20 °C. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in H2O. The material was further digested with 0.2 units of chondroitinase ABC (Sigma, catalog number C2905), followed by filtration with a 5-kDa filter unit (Millipore catalog number UFV5BCC00) to remove low molecular material. Recombinant Sulfs were precipitated from CM of Sulf-transfected 293 cells by nickel beads or FLAG antibody-conjugated to protein G. The resins with bound materials were washed 2 times with reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 50 mm MgCl2). [35S]HS (10 μl) was added to the resins in a volume of 200 μl of reaction buffer and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The supernatant was collected by centrifuging the reaction mixture at 14,000 × g for 15 min with the 5-kDa filter unit, and 35S counts/min was measured in the flow-through (representing free [35S]SO4) with a scintillation counter.

Membrane Fractionation and Lipid Raft Isolation

HEK 293 cells transfected with the N-terminal FLAG-tagged/C-terminal His-tagged versions of Sulf-1/Sulf-2 or HS766T cells (which express endogenous Sulf-2) were used for the membrane fractionation. Lipid rafts were isolated as follows (29): cells from a 60-mm dish were lysed in 1.5 ml of lysis solution (10 mm NaHPO4, pH 6.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% Triton X-100) at 4 °C. The lysate was mixed with the same volume of 80% sucrose. Eight sucrose density steps (35.6-5%, 1-ml per step made in the above buffer without detergent) were layered onto the 40% sucrose lysate, and centrifuged 40,000 × g for 20 h (Beckman SW41 rotor). Sixteen (0.69 ml/fraction) or nine (1.2 ml/fraction) fractions were collected. Equal volumes of the fractions were run on a 7.5% SDS gel followed by transfer to Problott membranes for Western blotting. The membranes were probed with FLAG antibody for recombinant Sulf-2, H2.3 for native Sulf-2 and with flotillin-1 antibody.

RESULTS

Both Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 Form Disulfide-linked Heterodimers

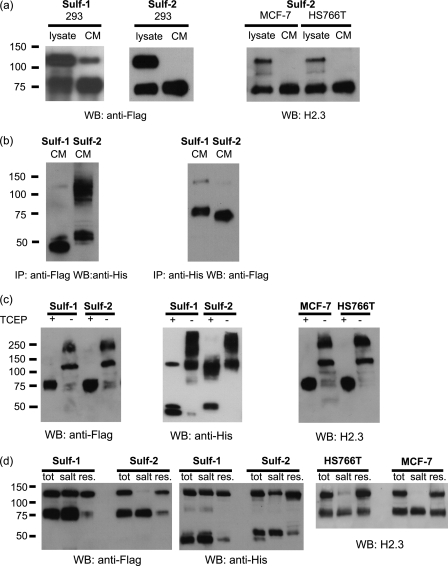

The largest molecular mass form of the HSulfs in whole cell lysates is ≈125 kDa, of which 100 kDa is protein and the remainder is predominantly N-glycans (7). To investigate proteolytic processing of Sulfs during their maturation, 293 cells were transfected with the FLAG/His HSulf plasmids, encoding a FLAG tag at the N-terminal of the protein and a His tag at the C-terminal. Detergent lysates of the transfectants and CM obtained from the cells were analyzed by FLAG Western blotting under reducing conditions. Cell lysates of both Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 transfectants contained a reactive ≈75-kDa band (77-kDa for Sulf-1 and 73-kDa for Sulf-2) in addition to the expected 125-kDa band (Fig. 1a). The 75-kDa band was dominant in CM, whereas the 125-kDa band was barely discernable. Native Sulf-2 produced by a breast cancer cell line (MCF7) and a pancreatic cancer cell line (HS766T) (24, 25) was analyzed with an antibody directed to a peptide in the N-terminal region of Sulf-2 (H2.3). Western blots of native Sulf-2 were similar to those for the recombinant protein (Fig. 1a). To determine the origin of the 75-kDa bands, Sulf protein from CM was immunoprecipitated by a His antibody followed by Western blotting with a FLAG antibody, and vice versa. For both Sulfs, the His-immunoprecipitated/FLAG Western blot combination yielded the 75-kDa band, whereas the FLAG-immunoprecipitated/His Western blot combination yielded a ≈50-kDa band (48-kDa for Sulf-1 and 52-kDa for Sulf-2) (Fig. 1b). Next, we analyzed Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 in CM by Western blotting under both reducing and non-reducing conditions. Without reduction, we detected a 125-kDa band with either the His antibody or the FLAG antibody, whereas with reduction (TCEP) we detected the 75- and 50-kDa bands by FLAG and His antibodies, respectively (Fig. 1c). Comparable results were obtained with native Sulf-2 from both MCF7 and HS766T cells (Fig. 1c). Thus, we conclude that for each Sulf, the 50- and 75-kDa components associate to form a heterodimer of 125-kDa via disulfide bonds.

FIGURE 1.

Subunit organization of the Sulfs. a, left, 293 cells were transfected with FLAG/His Sulf1/2 plasmids. Cell lysates and CM were probed by Western blotting with FLAG antibody under reducing conditions. In addition to the predicted 125-kDa band, a 75-kDa band was detected in cell lysates. In CM, a strong 75-kDa band was present, whereas the 125-kDa band decreased or disappeared for Sulf-1 and Sulf-2, respectively. Right, cell lysates and CM from HS766T cells and MCF7 cells were probed by Western blotting (WB) with H2.3 antibody (Sulf-2 peptide antibody). Again in CM, a strong 75-kDa band, instead of the 125-kDa band, was detected. b, CM from the 293 cells transfected with FLAG/His Sulf1/2 plasmids were immunoprecipitated with FLAG antibody and Western blotted with His antibody (left) or immunoprecipitated (IP) with His antibody and Western blotted with FLAG antibody (right), all under reducing conditions. The high molecular band (∼100 kDa) from Sulf-2 His-WB could be a dimer of the Sulf-2 C-terminal subunit but was not the full-length Sulf-2, as this band was not detected in FLAG Western blotting. c, left, CM from the 293 cells transfected with FLAG/His Sulf1/2 plasmids was concentrated 50-fold and probed with FLAG or His antibodies under reducing and nonreducing conditions (±TCEP). The high molecular mass forms (≥250 kDa) observed under non-reducing conditions are higher order oligomers. Right, CM from the HS766T cells and MCF7 cells were concentrated 50-fold and Western blotted with H2.3 under reducing and nonreducing conditions. d, left, 293 cells were transfected with FLAG/His Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 plasmids, two dishes for each. Cells from one dish were directly lysed in lysis buffer (tot), the other dish of cells was first washed once with 1 m NaCl (salt) and then lysed (res). Protein from those three fractions were analyzed by FLAG and His Western blot. Right, MCF-7 and HS766T cells were directly lysed (tot), or first washed once with 1 m NaCl (salt) and then lysed (res). The three fractions were analyzed by H2.3 Western blotting.

To check whether human Sulfs can associate with the cell membrane and if so, in what form, we used a transient high salt wash treatment. This procedure has been established to release QSulfs from intact cells (28). Salt washes of 293 cells transfected with the FLAG/His Sulf plasmids contained both the 75- and 50-kDa bands, as revealed by FLAG and His Western blotting, respectively (Fig. 1d). The processed form of Sulf-2 was also the predominant form on the cell surface of HS766T and MCF7 cells (Fig. 1d).

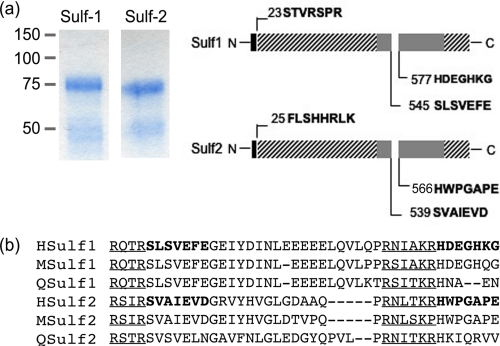

Sulfs Undergo Removal of Signal Peptides and Furin-type Proteinase-mediated Cleavage during Maturation

In our original description of the HSulfs, we predicted the probable sites of signal peptide cleavage and several potential furin cleavage sites in each protein (7). To define the actual cleavage sites, we performed Edman sequencing. 293 cells were transfected with the His Sulf plasmids (His at the C termini) and the Sulfs were purified from CM on nickel beads. Eluates were separated by reducing SDS-PAGE and blotted onto Problot membranes. Consistent with the findings described above, Gelcode Blue staining of purified Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 revealed 75- and 50-kDa bands under reducing conditions (Fig. 2a). The 75- and 50-kDa bands were eluted from the Problot membrane. Edman sequencing of the 75-kDa bands confirmed the removal of signal peptides and established that the mature proteins begin at position 23 for Sulf-1 and 25 for Sulf-2. Interestingly, the 50-kDa C-terminal subunits of Sulf-1/Sulf-2 were mixtures of two fragments, suggesting 2 cleavage sites (designated site 1 and site 2) in each protein. The protein sequences N-terminal of site 1 for Sulf-1/Sulf-2 are classical furin cleavage sequences (RXXR), whereas the sequences N-terminal of site 2 are less typical furin cleavage sites ((K/R)XXX(K/R)R) (30). These sequences are strongly conserved in human, mouse, and quail Sulfs (Fig. 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Edman sequencing of Sulf subunits . a, 293 cells were transfected with Sulf1/2 plasmids in pcDNA3.1/Myc-His(−) vector. Sulfs were purified from CM on nickel beads and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by Gelcode blue. The N-terminal bands (75 kDa) and C-terminal bands (50 kDa) for both Sulfs were subjected to Edman protein sequencing. The N-terminal sequences of the 75- and 50-kDa bands of Sulfs were identified. b, alignment of Sulf sequences surrounding the internal cleavage sites from several species. Amino acids identified by sequencing are in bold. Underlined sequences, which are immediately upstream of the cutting sites, are furin-type proteinase cleavage sequences and are highly conserved among species.

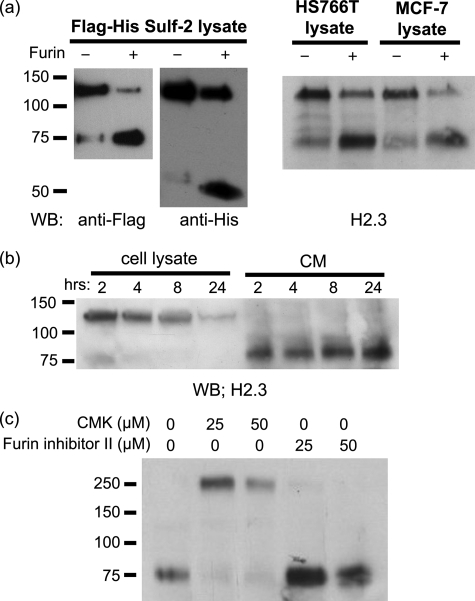

To confirm that a furin-type proteinase is responsible for processing of the Sulfs into 75- and 50-kDa subunits, 293 cells were transfected with FLAG/His Sulf-2 plasmid and Sulf-2 protein was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates. The immunoprecipitated protein was incubated with or without furin, followed by FLAG and His Western blotting. Furin treatment increased the signals for the 75- and 50-kDa bands with a corresponding decrease in the 125-kDa component (Fig. 3a). We obtained similar results with native Sulf-2 from HS766T and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3a) and with Sulf-1 (data not show).

FIGURE 3.

Cleavage of Sulf-2 by exogenous furin. a, left, 293 cells were transfected with the FLAG/His Sulf-2 plasmid. Sulf-2 was immunoprecipitated (predominant form 125 kDa) from cell lysates by FLAG antibody coupled to protein A beads. The bead-conjugated Sulf-2 was incubated overnight with or without furin. Digestion products were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with FLAG and His antibodies. Increased signals for 75- and 50-kDa subunits were observed after furin digestion. Right, a similar experiment was performed on endogenous Sulf-2 from HS766T cells and MCF7 cells. b, HS766T cells were pretreated with 100 μm cycloheximide. Cell lysates and CM were collected at different time points after treatment and analyzed by Western blotting with H2.3, directed to the N-terminal of Sulf-2. c, MCF7 cells were pretreated with a permeable furin-type proteinase inhibitor (decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethyl ketone, CMK) or furin inhibitor II for 3 h. Medium was replaced with fresh inhibitor and the cells were incubated for another 3 h. The medium was concentrated and analyzed for Sulf-2 by Western blotting with H2.3.

To establish the temporal sequence of Sulf processing, we blocked protein synthesis in Sulf-2-expressing HS766T cells and monitored Sulf-2 over time. The cells were continuously treated with 100 m cycloheximide. Cell lysates and CM were collected at different time points after treatment and analyzed by H2.3, the N-terminal directed antibody. With time, there was a decrease of the 125-kDa band in cell lysates and an increase in the 75-kDa band in CM (Fig. 3b). This result is consistent with a proteolytic processing step in which the 125-kDa precursor is cleaved into subunit products.

To obtain further information about the furin-type proteinase, we employed a cell-permeable furin inhibitor (decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethyl ketone) and a polyarginine inhibitor (Furin inhibitor II) (31, 32). MCF7 cells were exposed to the inhibitors at several concentrations for a total of 6 h (with replenishment at 3 h). Only the cell-permeable inhibitor, decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethyl ketone, efficiently inhibited cleavage (Fig. 3c). This finding provides further validation of the participation of a furin-type proteinase in Sulf processing and establishes that this step takes place inside the cell, presumably in the trans Golgi of the cells (30). Because the uncleaved form of Sulf-2 was present in CM, we also conclude that cleavage is not a prerequisite for secretion. Interestingly, the uncleaved form of Sulf-2 had a molecular mass of ≈250 kDa, twice that of the full-length protein, indicating that multimerization of the protein was facilitated in the absence of proteolytic processing. We suspect that the C-terminal region might be responsible for multimerization, because we observed the tendency of the 50-kDa subunit to form dimers by His Western blotting (Fig. 1b). This characteristic was not observed for the 75-kDa subunit.

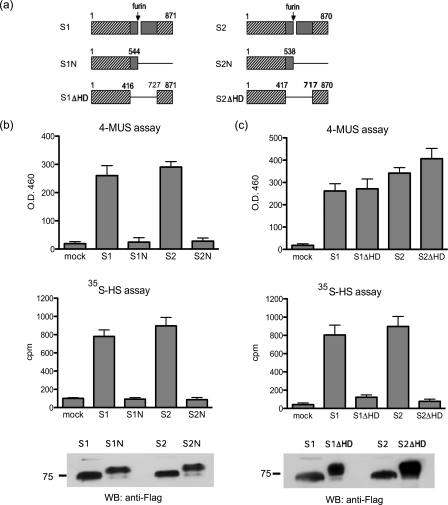

Structural Requirements for Enzymatic Activity

The catalytic center of the Sulfs resides in the N-terminal 75-kDa subunits (7, 8, 26). To determine whether the C-terminal 50-kDa subunits were required for activity, we prepared truncation mutants of the Sulfs, which lacked the entire C-terminal regions after site 1. 293 cells were transfected with wild-type FLAG/His Sulf plasmid and the truncation mutant plasmids. CM was immunoprecipitated by the FLAG antibody and the protein-bead complex was tested for enzymatic activity with two substrates: 4-MUS and 35SO4-labeled heparan sulfate ([35S]HS). 4-MUS is a general substrate, which can be used to measure arylsulfatase activity of many sulfatases (33) including the Sulfs (7), whereas heparan sulfate is the native substrate, which is used to measure the endosulfatase activity of the Sulfs (7, 9, 10, 13). Although the Sulf-1/Sulf-2 truncation mutants were expressed in CM at comparable levels to the wild-type proteins, they were completely inactive in both assays (Fig. 4b). One explanation is that the most C-terminal of the 9 evolutionarily conserved regions common to all 17 human sulfatases (26) resides in the 50-kDa subunits of the Sulfs. The other 8 conserved regions occur in the first 450 amino acids and reside in the 75-kDa subunits. Thus, in the Sulfs the C-terminal conserved region is separated from the other 8 by insertion of the hydrophilic domain. Ai et al. (28) showed that mutations within the hydrophilic domain of QSulf-2 cause a loss of endosulfatase activity against heparan sulfate. We hypothesized that a Sulf mutant, which contains all 9 conserved regions, but not the hydrophilic domain would retain arylsulfatase activity but would lose endosulfatase activity. To test this prediction, the hydrophilic domains (amino acids 417–726 for Sulf-1 and 418–715 for Sulf-2) were deleted according to sequence alignment with human lysosomal glucosamine-6-sulfatase (7, 8). The HD-less mutants showed similar arylsulfatase activity as the wild-type proteins. However, endosulfatase activity was completely lost in both cases (Fig. 4c). The neutral pH optimum for arylsulfatase activity, observed for the wild-type enzymes (7), was preserved in the mutants (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Enzymatic activity of Sulf C-terminal truncation and HD-deletion mutants. a, diagram of C-terminal truncation and HD-deletion Sulf mutants. The cross-hatching indicates the sulfatase-related regions and gray shading indicates the hydrophilic domains. b, the C-terminal truncation mutants and wild-type Sulfs were tested for activity in the 4-MUS and [35S]HS digestion assays. Similar amounts of enzymes were used in enzymatic assays as shown by FLAG Western blotting. c, the HD-deletion mutants and wild-type Sulfs were tested in the 4-MUS assay and [35S]HS assay. Data are means ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Uncleavable Sulfs Retain Enzymatic Activity

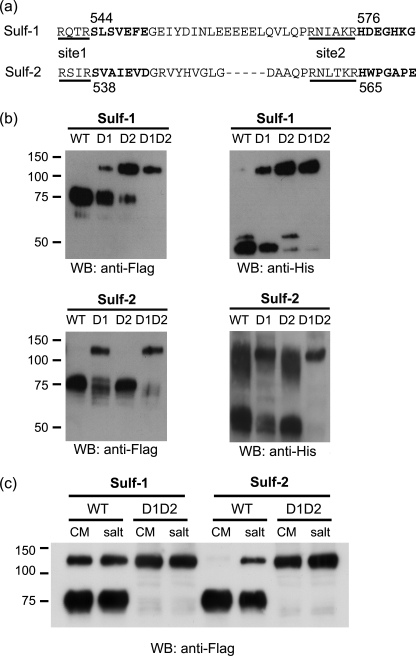

We next sought to determine the contribution of the processing steps to the biological activity of the Sulfs by preparing “uncleavable” versions. To obtain such mutants, we deleted the furin cleavage sequence at site 1 or site 2 or at both sites from the FLAG/His Sulf plasmid templates (Fig. 5a). Deletion mutants were transfected into 293 cells and CM was analyzed by FLAG and His Western blotting. For Sulf-1, each single deletion partially inhibited cleavage, whereas the double deletion prevented cleavage almost completely. For Sulf-2, deletion at site 1 partially blocked cleavage but deletion at site 2 had no effect. Cleavage was almost completely blocked when both sites were deleted (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that a furin-type proteinase cleaves Sulf-1 comparably at both sites, but acts on Sulf-2 preferentially at site 1. The double deletion mutations did not alter the proportion of the Sulf that was secreted versus retained on the cell surface (Fig. 5c).

FIGURE 5.

The generation of uncleavable Sulf mutants. a, the underlined sequences, which are immediately upstream of the N termini of the 50-kDa subunits (bold), are furin cleavage sites. Single (D1 or D2) or double deletions (D1D2) of these sequences were made by PCR. b, 293 cells were transfected with wild-type and the various deletion mutants were prepared in FLAG/His Sulf1/2 plasmids. CM was analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with FLAG and His antibodies. c, 293 cells were transfected with wild-type Sulfs and double deletion mutants with one 10-cm dish used for each condition. 5 ml of CM was collected after 72 h. The same cells were then washed with 5 ml of 1 m NaCl to strip off the Sulfs from the cell surface. 50 μl of CM and ×10 concentrated salt washes were analyzed by Western blotting with FLAG antibody.

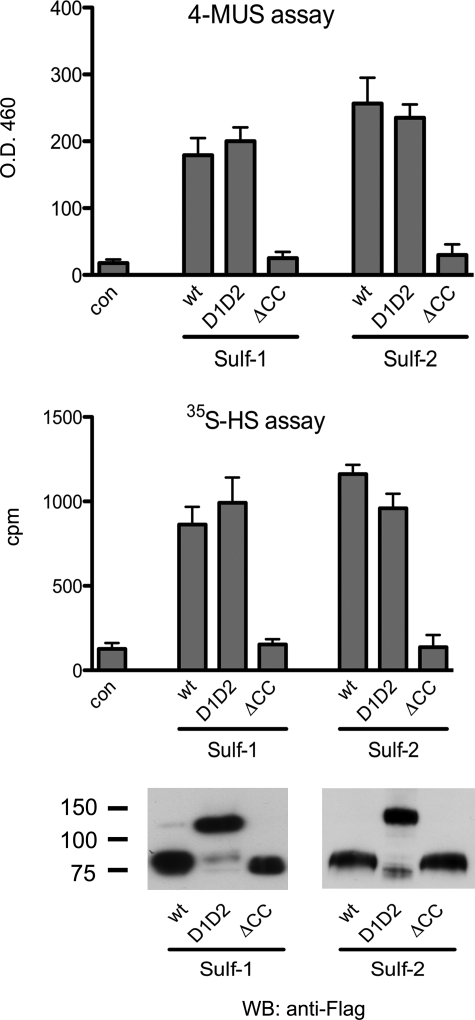

We carried out the 4-MUS and [35S]HS assays on the double deletion mutants of the Sulfs. The uncleavable mutants exhibited similar activities as the wild-type proteins in the two assays when measured at comparable concentrations (Fig. 6). Sulf1ΔCC and Sulf2ΔCC, which are enzymatically inactive forms of the enzymes with substitutions for cysteines in the actives sites (7) were included in both assays as negative controls.

FIGURE 6.

Enzymatic activity of uncleavable Sulf mutants. 293 cells were transfected with plasmids for wild-type Sulf-1/2 or double deletion mutants. The inactive ΔCC mutant was included as a negative control. CM was immunoprecipitated by FLAG antibody and assayed against 4-MUS and [35S]HS. Similar amounts of enzymes were used in enzymatic assays, as shown by FLAG Western blotting (WB). Data are means ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Uncleavable Sulfs Lack Wnt Promoting Activity and Mislocalize on the Plasma Membrane

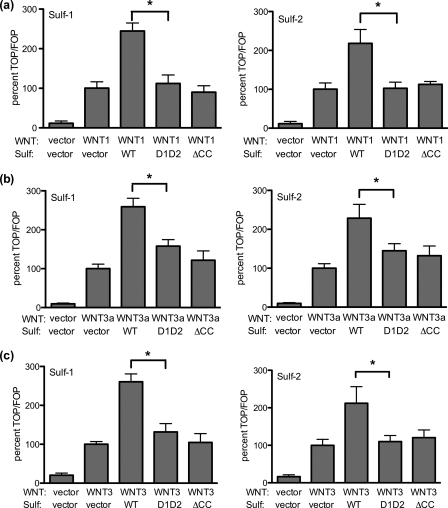

Promotion of Wnt signaling is a major biological function of the Sulfs (8, 9, 14, 25), presumably occurring via Sulf-mediated release of Wnt ligands from HSPG sequestration (9). We next asked whether the uncleavable Sulf mutants were active in the Wnt pathway by adapting previously described assays (9, 25). We used 293 cells, which are capable of Wnt signaling when provided with an exogenous source of Wnt ligands (25, 27). We measured Wnt signaling using the TOP/FOP flash assay, which quantifies β-catenin-dependent transcriptional activity. Burris and co-workers (27) have shown that 293 cells respond to Wnt ligands with a large increase in TOP/FOP flash activity. We transfected 293 cells with plasmids encoding Wnt ligands (Wnt1, Wnt3a, or Wnt3) and found an ≈40-fold increase in Wnt signaling in each case. For all three Wnts, the TOP/FOP flash signal was further enhanced by 2–3-fold when the 293 cells were transfected with a plasmid for either Sulf-1 or Sulf-2, but was not changed by the catalytically inactive forms (Fig. 7). These findings add Wnt3 and Wnt3a to the list of Wnt ligands (i.e. Wnt1, Wnt4, and Wnt11) for which signaling is promoted by the Sulfs (8, 9, 14, 25). Strikingly, the uncleavable Sulf mutants were unable to enhance signaling by Wnt1 or Wnt3, and had only a minor effect on Wnt3a signaling.

FIGURE 7.

The effects of uncleavable Sulfs on Wnt signaling. Wnt signaling activity was monitored by the TOP/FOP flash assay in the presence of wild-type Sulfs, uncleavable Sulfs, or inactive Sulfs (Sulf-1ΔCC and Sulf-2ΔCC). a, Wnt 1. b, Wnt 3a. c, Wnt 3. The signal promoted by each Wnt ligand alone is set at 100% (the Wnts increased TOP/FOP flash by ≈40-fold). Data are means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. * denotes p < 0.05 by Student's t test.

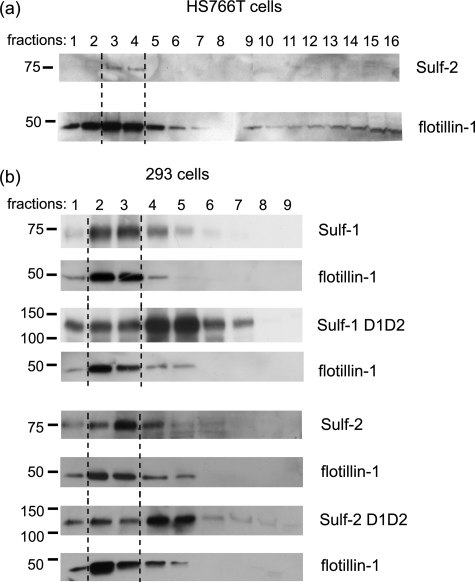

Because at least some Wnts are associated with lipid rafts on the cell surface (34), we wondered whether the Sulfs might also reside in these membrane subdomains. To address this question, we fractionated HS766T membranes by sucrose gradient centrifugation and examined the distribution of Sulf-2 in the different fractions. A significant portion of Sulf-2 was found in the lipid-raft fraction, as indicated by the presence of the raft-resident protein, flotillin-1 (35) (Fig. 8a). We extended this investigation to the recombinant Sulfs. 293 cells were transfected with the FLAG/His Sulf plasmids and the corresponding uncleavable mutants. In each case, wild-type Sulf was concentrated in the lipid raft fraction. However, the uncleavable mutant showed a markedly reduced accumulation in lipid rafts (Fig. 8b), indicating that the mutant was more evenly distributed on the cell surface.

FIGURE 8.

Membrane fractionation of Sulf-expressing cells. a, sucrose gradient fractionation of Sulf-2 expressing HS766T cells. 16 fractions were collected and analyzed by Western blotting with H2.3 and a flotillin-1 antibody. b, sucrose gradient fractionation of 293 cells transfected with plasmids for wild-type Sulf 1/2 or the uncleavable mutants. 9 fractions were collected and probed as above. Lipid raft-containing fractions were identified by the presence of flotillin-1.

DISCUSSION

The Sulfs regulate extracellular signaling events, which contrasts with the lysosomal subfamily of sulfatases, which are involved in the catabolism of sulfated substrates (36). The growing importance of the Sulfs in development and carcinogenesis has underscored the need for further biochemical characterization of these enzymes. Previous work on the Sulfs has shown that they undergo a series of post-translational modifications, which are important for their catalytic activity. For example, in common with other sulfatases (37, 38), the activity of both Sulfs relies on the conversion of a highly conserved cysteine within the catalytic domain into Cα-formylglycine, the site at which sulfate is directly bound (7, 8, 33). In addition, N-linked glycosylation is required for QSulf-1 activity (39). In contrast to this information about post-translational modifications, little has been reported concerning the proteolytic processing of these enzymes. The present study was prompted by the observation of Sulf fragments in Western blots (7, 16, 24, 25), which suggested chain cleavage and the possible existence of a subunit organization. Here, we provide information about the maturation of these enzymes, their subunit organization, and the requirements for their enzymatic and signaling functions. We found that both Sulf-1 and Sulf-2 are initially synthesized as prepro-proteins and are converted to pro-proteins by removal of their signal peptides. The pro-proteins are cleaved by a furin-type proteinase into two chains of 75 and 50 kDa, which form disulfide-linked heterodimers. A portion of the mature heterodimer is secreted, whereas a significant fraction is retained on the cell membrane. It is noteworthy that the QSulfs, in contrast to the HSulfs, are not secreted (28). The Sulfs are highly homologous across species; however, the hydrophilic domains, especially in their central regions, have reduced sequence identity. Because the hydrophilic domain is required for QSulf-1 and QSulf-2 membrane association (8, 28), it is plausible that the sequence variation in this domain accounts for the difference in secretion.

Furin belongs to the pro-protein convertase family (30). These are secreted proteases, which cleave precursor proteins into their mature/active forms by limited proteolysis at one or more internal sites (30). We identified two principle furin-type proteinase cleavage sites in both HSulf-1 and HSulf-2. The importance of these target sequences is indicated by the high degree of conservation in human, mouse, and quail. Blocking the cleavage by mutating both sites had little or no effect on the secretion of the Sulfs or their solubility. Moreover, Sulf activity against both 4-MUS and [35S]HS persisted in the uncleavable mutants, although a detailed comparison of enzyme kinetics remains to be done. Most significantly, the mutated Sulfs were unable to potentiate Wnt signaling.

The 75-kDa N-terminal subunit of each Sulf contains the conserved catalytic center of sulfatases, and it is necessary for enzymatic activity (7). This subunit is not sufficient for activity because, when it was expressed alone, it was inactive against both 4-MUS and [35S]HS. We reasoned that this complete loss of activity was because the N-terminal subunit lacks the most C-terminal of the evolutionarily conserved regions within the sulfatase family. By deleting the HD domains, we created proteins, which resembled lysosomal enzymes in that the 9 conserved regions were contiguous. These HD-less mutants demonstrated normal arylsulfatase activities but were inactive against heparan sulfate. Thus, the inserted hydrophilic domains distinguish the Sulfs from lysosomal exosulfatases and appear to endow the Sulfs with endosulfatase activity. Ai et al. (28) showed that the hydrophilic domains of QSulfs exhibit heparan sulfate binding activity and are thus likely involved in substrate binding by the enzymes. An analogy may be drawn between the Sulfs and collagenases/aggrecanases (40). These extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes contain catalytic domains, as well as noncatalytic “exosite” domains, which participate in the recognition of the natural substrates of the enzymes. Our results argue that the hydrophilic domains contain analogous exosites for the Sulfs.

Our findings also demonstrate that Sulf-2 accumulates in lipid-rich domains. This finding is in line with previous reports that large amounts of HSulf and QSulf are found in a detergent-insoluble membrane fraction (7, 16, 28), which is known to include lipid rafts (59). Interestingly, Wnt ligands are lipid-modified (34, 41, 42), and a lipid raft localization has been reported for Wnt1 (34). Additionally, glypicans, which are established HSPG partners for Wnt signaling (43, 44), also localize to lipid rafts (45, 46), as does the Wnt co-receptor LRP6 (47). Therefore, for optimal signaling it would seem most favorable if the Sulfs are concentrated in the same membrane microdomain as these other elements of Wnt signaling. Our data also show that localization of the Sulfs into lipid rafts was markedly reduced when furin-type proteinase cleavage was prevented, whereas their secretion and enzymatic activity were not apparently affected. Strikingly, the uncleavable mutants of both Sulfs lost their ability to potentiate Wnt signaling for three different Wnts. The altered membrane distribution due to lack of the furin-type proteinase cleavage event is therefore a plausible explanation for the reduced Sulf activity in signaling. Although the exact mechanism of how this cleavage could regulate Sulf accumulation in the lipid rafts is unknown, it is conceivable that this step is obligatory for a modification that controls the membrane subdomain localization. It is also possible that heterodimer organization of the Sulfs could be critical for their long-range activity. In our Wnt signaling reporter assay (TOP/FOP assay), we could not distinguish whether the increment of Wnt signaling by Sulf is a result of Sulf acting on the same cell, which produces the enzyme, or on neighboring cells, or both. Whether soluble, secreted Sulfs can integrate into the lipid rafts of neighboring cells (or of the secreting cell) is not known.

Several lines of evidence establish that furin-type proteinase activities contribute to cancer. Furin is up-regulated in several cancers (48–50) and in some cases inhibition of furin-type proteinases inhibits cancer cell invasiveness and proliferation (51–55). As the pro-oncogenic activity of the Sulfs in certain cancers may be based on promotion of Wnt signaling (25), the furin-type proteinase involved in these processing steps could be a therapeutic target.

Crystal structures of three human sulfatases, arylsulfatase A, B, and C, have been determined (56–58). However, the Sulfs have not yet been crystallized. Structural information derived from crystals will provide further understanding of how the Sulf subdomains contribute to removal of glucosamine-6-O-sulfate from specific HSPG substrates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kenji Uchimura from the National Institute for Longevity and Sciences, Japan, for useful discussions. We thank Dr. Laura Burris, California State University, San Francisco, for Wnt1 and Wnt3a plasmids, Dr. Randy Moon, University of Washington for Super8XTopFlash, Super8XfopFlash, and RL-CMV, and Dr. Jan Kitajewski for the Wnt3 plasmid.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 AI053194 and R21 CA122025 (to S. D. R.). This work was also supported by Tobacco-related Disease Research Program of the University of California Grant 17RT-0117.

- HSPG

- heparan sulfate proteolglycan

- 4-MUS

- 4-methylumbelliferyl sulfate

- [35S]HS

- [35S]SO4-labeled heparan sulfate

- CM

- conditioned medium

- HD

- hydrophilic domain

- TCEP

- Tris[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernfield M., Götte M., Park P. W., Reizes O., Fitzgerald M. L., Lincecum J., Zako M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 729–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop J. R., Schuksz M., Esko J. D. (2007) Nature 446, 1030–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher J. T. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 357–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esko J. D., Lindahl U. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 169–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habuchi H., Habuchi O., Kimata K. (2004) Glycoconj. J. 21, 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habuchi H., Nagai N., Sugaya N., Atsumi F., Stevens R. L., Kimata K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15578–15588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morimoto-Tomita M., Uchimura K., Werb Z., Hemmerich S., Rosen S. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49175–49185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhoot G. K., Gustafsson M. K., Ai X., Sun W., Standiford D. M., Emerson C. P., Jr. (2001) Science 293, 1663–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ai X., Do A. T., Lozynska O., Kusche-Gullberg M., Lindahl U., Emerson C. P., Jr. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viviano B. L., Paine-Saunders S., Gasiunas N., Gallagher J., Saunders S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5604–5611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ai X., Kitazawa T., Do A. T., Kusche-Gullberg M., Labosky P. A., Emerson C. P., Jr. (2007) Development 134, 3327–3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchimura K., Morimoto-Tomita M., Bistrup A., Li J., Lyon M., Gallagher J., Werb Z., Rosen S. D. (2006) BMC Biochemistry 7, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchimura K., Morimoto-Tomita M., Rosen S. D. (2006) Methods Enzymol. 416, 243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman S. D., Moore W. M., Guiral E. C., Holme A. D., Turnbull J. E., Pownall M. E. (2008) Dev. Biol. 320, 436–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai Y., Yang Y., MacLeod V., Yue X., Rapraeger A. C., Shriver Z., Venkataraman G., Sasisekharan R., Sanderson R. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40066–40073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamanna W. C., Frese M. A., Balleininger M., Dierks T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27724–27735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue X., Li X., Nguyen H. T., Chin D. R., Sullivan D. E., Lasky J. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20397–20407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holst C. R., Bou-Reslan H., Gore B. B., Wong K., Grant D., Chalasani S., Carano R. A., Frantz G. D., Tessier-Lavigne M., Bolon B., French D. M., Ashkenazi A. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lum D. H., Tan J., Rosen S. D., Werb Z. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 678–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratzka A., Kalus I., Moser M., Dierks T., Mundlos S., Vortkamp A. (2008) Dev. Dyn. 237, 339–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai J. P., Chien J. R., Moser D. R., Staub J. K., Aderca I., Montoya D. P., Matthews T. A., Nagorney D. M., Cunningham J. M., Smith D. I., Greene E. L., Shridhar V., Roberts L. R. (2004) Gastroenterology 126, 231–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai J., Chien J., Staub J., Avula R., Greene E. L., Matthews T. A., Smith D. I., Kaufmann S. H., Roberts L. R., Shridhar V. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23107–23117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai J. P., Sandhu D. S., Yu C., Han T., Moser C. D., Jackson K. K., Guerrero R. B., Aderca I., Isomoto H., Garrity-Park M. M., Zou H., Shire A. M., Nagorney D. M., Sanderson S. O., Adjei A. A., Lee J. S., Thorgeirsson S. S., Roberts L. R. (2008) Hepatology 47, 1211–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimoto-Tomita M., Uchimura K., Bistrup A., Lum D. H., Egeblad M., Boudreau N., Werb Z., Rosen S. D. (2005) Neoplasia 7, 1001–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nawroth R., van Zante A., Cervantes S., McManus M., Hebrok M., Rosen S. D. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sardiello M., Annunziata I., Roma G., Ballabio A. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 3203–3217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galli L. M., Barnes T. L., Secrest S. S., Kadowaki T., Burrus L. W. (2007) Development 134, 3339–3348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ai X., Do A. T., Kusche-Gullberg M., Lindahl U., Lu K., Emerson C. P., Jr. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4969–4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taipale J., Chen J. K., Cooper M. K., Wang B., Mann R. K., Milenkovic L., Scott M. P., Beachy P. A. (2000) Nature 406, 1005–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas G. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 753–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia A. L., Han S. K., Janssen W. G., Khaing Z. Z., Ito T., Glucksman M. J., Benson D. L., Salton S. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41595–41608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen S., Stefan C., Creemers J. W., Waelkens E., Van Eynde A., Stalmans W., Bollen M. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 3081–3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parenti G., Meroni G., Ballabio A. (1997) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7, 386–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhai L., Chaturvedi D., Cumberledge S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33220–33227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuermer C. A., Lang D. M., Kirsch F., Wiechers M., Deininger S. O., Plattner H. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3031–3045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diez-Roux G., Ballabio A. (2005) Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 6, 355–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cosma M. P., Pepe S., Annunziata I., Newbold R. F., Grompe M., Parenti G., Ballabio A. (2003) Cell 113, 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dierks T., Schmidt B., Borissenko L. V., Peng J., Preusser A., Mariappan M., von Figura K. (2003) Cell 113, 435–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ambasta R. K., Ai X., Emerson C. P., Jr. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34492–34499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagase H., Fushimi K. (2008) Connect. Tissue Res. 49, 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurayoshi M., Yamamoto H., Izumi S., Kikuchi A. (2007) Biochem. J. 402, 515–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willert K., Brown J. D., Danenberg E., Duncan A. W., Weissman I. L., Reya T., Yates J. R., 3rd, Nusse R. (2003) Nature 423, 448–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capurro M. I., Xiang Y. Y., Lobe C., Filmus J. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 6245–6254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin X., Perrimon N. (1999) Nature 400, 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe N., Araki W., Chui D. H., Makifuchi T., Ihara Y., Tabira T. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 1013–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharom F. J., Lehto M. T. (2002) Biochem. Cell Biol. 80, 535–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto H., Komekado H., Kikuchi A. (2006) Dev. Cell 11, 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng M., Watson P. H., Paterson J. A., Seidah N., Chrétien M., Shiu R. P. (1997) Int. J. Cancer 71, 966–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bassi D. E., Mahloogi H., Al-Saleem L., Lopez De Cicco R., Ridge J. A., Klein-Szanto A. J. (2001) Mol. Carcinog. 31, 224–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schalken J. A., Roebroek A. J., Oomen P. P., Wagenaar S. S., Debruyne F. M., Bloemers H. P., Van de Ven W. J. (1987) J. Clin. Invest. 80, 1545–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coppola J. M., Bhojani M. S., Ross B. D., Rehemtulla A. (2008) Neoplasia 10, 363–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassi D. E., Fu J., Lopez de Cicco R., Klein-Szanto A. J. (2005) Mol. Carcinog. 44, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khatib A. M., Siegfried G., Chrétien M., Metrakos P., Seidah N. G. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1921–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McMahon S., Laprise M. H., Dubois C. M. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 291, 326–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siegfried G., Khatib A. M., Benjannet S., Chrétien M., Seidah N. G. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 1458–1463 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bond C. S., Clements P. R., Ashby S. J., Collyer C. A., Harrop S. J., Hopwood J. J., Guss J. M. (1997) Structure 5, 277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hernandez-Guzman F. G., Higashiyama T., Pangborn W., Osawa Y., Ghosh D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22989–22997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lukatela G., Krauss N., Theis K., Selmer T., Gieselmann V., von Figura K., Saenger W. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 3654–3664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown D. A., London E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17221–17224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]