Abstract

Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) coordinates cellular functions essential for sustaining tissue homeostasis; yet its regulation in the intestine is not well understood. Here, we identify a novel physiological link between Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and GJIC through modulation of Connexin-43 (Cx43) during acute and chronic inflammatory injury of the intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) barrier. Data from in vitro studies reveal that TLR2 activation modulates Cx43 synthesis and increases GJIC via Cx43 during IEC injury. The ulcerative colitis-associated TLR2-R753Q mutant targets Cx43 for increased proteasomal degradation, impairing TLR2-mediated GJIC during intestinal epithelial wounding. In vivo studies using mucosal RNA interference show that TLR2-mediated mucosal healing depends functionally on intestinal epithelial Cx43 during acute inflammatory stress-induced damage. Mice deficient in TLR2 exhibit IEC-specific alterations in Cx43, whereas administration of a TLR2 agonist protects GJIC by blocking accumulation of Cx43 and its hyperphosphorylation at Ser368 to prevent spontaneous chronic colitis in MDR1α-deficient mice. Finally, adding the TLR2 agonist to three-dimensional intestinal mucosa-like cultures of human biopsies preserves intestinal epithelial Cx43 integrity and polarization ex vivo. In conclusion, Cx43 plays an important role in innate immune control of commensal-mediated intestinal epithelial wound repair.

The intestinal epithelial cell (IEC)3 barrier provides the front line of mucosal host defense in the intestine. The IEC barrier confers anatomic integrity and immunologic protection of the intestinal mucosal surface. Because the IEC barrier constantly faces diverse populations of lumenal microbes and other potential threats, it must exert a highly defined process of continuous discrimination: excluding harmful antigens while allowing host-beneficial substances to permeate (1, 2). Para- and intercellular transit of molecules is modulated by a complex network of closely arranged tight (TJ) and gap junctions (GJ) between juxtaposed IEC. Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) is an essential, but not well understood, mechanism for cellular and tissue homeostasis that coordinates cell-cell passage of ions and small metabolites (<1 kDa). Thus, GJIC regulates cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation (3). GJ channels are formed by hexameric connexins at the plasma membrane. Cx43 is the major connexin and represents a key target in GJIC regulation (4). It is differentially phosphorylated at a dozen or more residues throughout its life cycle (5–9). Alteration of GJIC caused by changes in Cx43 has been proposed to be involved in the pathophysiology of diverse IEC barrier diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases, necrotizing enterocolitis, cancer, and enteric infection (10–12). However, immune mediators that allow protective GJIC via Cx43 to sustain IEC barrier function during mucosal damage have not yet been identified.

Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), a member of the TLR family that is constitutively expressed in IEC (13–15), recognizes conserved molecular patterns associated with both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria (16). We have previously shown that commensal-mediated TLR2 helps to maintain functional TJ barrier integrity of the intestinal epithelial layer. TLR2 enhances transepithelial resistance of the IEC barrier by apical redistribution of ZO-1 via protein kinase Cα/δ (17). Treatment with the TLR2 ligand PCSK protects ZO-1-associated IEC barrier integrity and decreases intestinal permeability in acute colitis (18). Previous studies in other cell types have demonstrated that the second PDZ domain of ZO-1 interacts with the carboxyl terminus of Cx43 (19, 20). ZO-1 binds to Cx43 preferentially during the G0 phase, enhancing assembly and stabilization of GJIC (21, 22). Like TLR2, Cx43 and ZO-1 reside in caveolin-1-associated lipid raft microdomains (23–25). We therefore hypothesized that the binding between ZO-1 and Cx43 may allow TLR2 to control IEC barrier function by GJIC.

In this study, we identified a new physiological mechanism of innate immune host defense in the injured intestine. Our findings indicated that Cx43 serves as an important component of the protective innate immune response of the intestinal epithelium. TLR2-induced GJIC via Cx43 appears to control IEC barrier function and restitution during acute and chronic inflammatory damage, enhancing mucosal homeostasis between commensals and host. UC-associated TLR2 mutant results in impaired GJIC by a proteasomal-dependent increase in Cx43 turnover.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Synthetic lipopeptide Pam3Cys-SKKKKx3-HCl (PCSK; Lots L08/02 and A10/02) was obtained from EMC Microcollections GmbH (17). Mouse monoclonal and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Cx43 (clone CX-1B1, which detects nonphosphorylated (P0) and phosphorylated (P½) forms of Cx43 (26); clone Z-JB1, which detects total Cx43 but partially cross-reacts with some phosphorylated forms (27)) and polyclonal antibody against ZO-1 (antibody 61-7300) were obtained from Zymed Laboratories Inc.-Invitrogen. Polyclonal antibodies to phosphorylated Cx43 at Ser368 (antibody 3511) (28) was purchased from Cell Signaling. Pan-cytokeratin polyclonal/monoclonal antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-human TLR2 monoclonal antibody (clone TL2.1) was from Alexis Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from GE Healthcare-Amersham Biosciences. Lactacystin was from Merck. All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified.

Animals

MDR1α−/− mice (FVB.129P2-Abcb1atm1Bor; >F7) and appropriate WT controls (FVB/N) were purchased and bred under the Research Agreement from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). TLR2−/− mice (Tlr2tm1Kir; >F10 (C57BL6/J); The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and their WT controls (C57BL6/J) have previously been described (18). All of the mice were housed and bred in the same room under strict specific pathogen-free conditions (Helicobacter species, murine norovirus-free) at the Central Animal Facility of University Hospital of Essen (Essen, Germany). Extensive animal health monitoring was conducted routinely on representative mice from this room (Gesellschaft für innovative Mikroökologie mbH, Wildenbruch, Germany). The animals were provided with autoclaved tap water and autoclaved standard laboratory chow ad libitum. All male MDR1α−/− developed loose stools and mucous discharge by ∼8 weeks of age in our specific pathogen-free room, and therefore only male MDR1α−/− were included in this study. Histology scoring was modified according to previous reports (29, 30), based on the specific characteristics of this murine colitis model (supplemental Table S3). Colitis was induced in TLR2−/− or WT by the addition of DSS (molecular weight, 36,000–50,000; Lot 6955H; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) in different concentrations in drinking water for 5 days (18). Female mice aged 8–11 weeks old were used for DSS studies. All of the protocols were in compliance with German law for use of live animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University Hospital of Essen and the responsible district government.

Cell Lines

Caco-2 and IEC-6 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained as described previously (17).

Plasmid Constructs and Cell Transfection

HA-tagged TLR2 full-length (TLR2-FL) and HA-tagged TLR4 full-length (TLR4-FL) plasmids in the same backbone vector were obtained from InvivoGen. UC mutant TLR2-R753Q was generated within the TLR2-FL expression construct and confirmed by sequencing (Trenzyme). Plasmids (EndoFree Maxi; Qiagen) were transfected into Caco-2 cells on a 12-well plate using 1 μg/well of TLR2-FL, TLR4-FL, or TLR2-R753Q (Lipofectamine LTX; Invitrogen). Stable transfectants were selected with 1 μg/ml blasticidin and maintained on poly-d-lysine-coated tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences). Transfection efficiency of the different clones was comparable with previous findings from other cell types (31), as tested by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry with anti-HA (InvivoGen; Cell Signaling). Caco-2 controls (mock) were untransfected cells without any exogenous DNA.

Three-dimensional Human Intestinal Mucosa-like Culture Model of Biopsies

Fresh tissue samples from healthy patients undergoing complete colonoscopy for regular colon cancer screening examinations and/or polypectomy were collected at the Endoscopy Unit, Department of Gastroenterology and Metabolic Diseases (Head: M. Rünzi, M.D.), Kliniken Essen-Süd (Essen, Germany). Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure, and the protocol was approved by the Human Studies Committee of Kliniken Essen-Süd. Small cecal specimens were obtained by gently touching down the biopsy forceps onto the mucosal surface. The samples were immediately washed twice in ice-cold Hanks' buffered salt solution (PAA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, gentamicin, and antibiotic/antimycotic solution; then mixed with or without PCSK (20 μg/ml) into a thin layer of cold liquid Matrigel (BD Biosciences) surrounding the biopsy, which was allowed to polymerize, forming a solid gel at 37 °C within 30 min; then covered with warm full L-15 medium; and cultured for 4 h. Matrigel biopsy blocks were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura), and stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Gap Junction Dye Coupling Assays

For assessment of GJ communication by microinjection, 5% Lucifer Yellow CH dye (lithium salt in 100 mm water solution; Invitrogen) was injected into IEC-6 cells, and dye transfer was quantitated by determining the number of directly adjacent cells that received dye (dye coupling). The cells were visualized using an inverted phase contrast/confocal laser microscope (LD-Achroplan 40×/0.6 corr (dry) objective; Zeiss LSM510; Axiovert 100M) and injected using a transinjector with micromanipulator (model 5246/5171; Eppendorf). The frequencies of dye transfer to directly adjacent cells were determined in the presence or absence of PCSK 37s after dye injection (pi = 60 hPa; pc = 20 hPa; ti = 0.2 s) with or without cell injury by acquiring fluorescent images in an automated time series with an interval of 11.671 s, with each confocal scan set to take 3.8 s. Control dye was 10% tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-dextran (molecular weight, 3000) in 100 mm LiCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.8. The nuclei were counterstained with cell-permeant SytoGreen fluorescent nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen). For assessment of GJ communication by scrape wound loading, Lucifer Yellow CH (0.05% dye in phosphate-buffered saline (without Ca2+ and Mg2+)) was loaded intracellularly by scraping Caco-2-TLR2-FL and Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells with a razor blade. The dye solution was left in the dish for 8 min. After washing, fixation, immunostaining with anti-Lucifer Yellow rabbit polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen) followed by FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch), and mounting with Vectashield/DAPI, the cells were examined for dye transfer using a laser-scanning confocal microscope Zeiss Axiovert 100M-LSM 510. The degree of communication was assessed by determining the extent of Lucifer Yellow transfer into contiguous cells.

siRNA Blockade of Rectal Epithelial Cx43 in DSS Colitis

The mice received 2.3% DSS in drinking water for 5 days, followed by oral PCSK therapy (see Fig. 6A). siRNA targeting murine Cx43 (siGENOME on-Target plus SMART pool; catalog number L-051694-00-0005; accession number NM_010288) and scrambled controls (siGENOME on-Target plus siCONTROL pool; catalog number D-001810-10-05) were obtained from Dharmacon and resuspended in sterile RNase-free water. siRNA was freshly lipoplexed with Lipofectamine 2000 in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and administered immediately (5 nmol in 20 μl of solution/mouse) to the rectum of isoflurane-anesthesized WT mice (C57BL6/J) once daily (days 3–5) using a P20 pipettor (Eppendorf), as described previously (32). Five hours after receiving the last siRNA treatment, control groups (n = 5 mice/group; group 1, Cx43siRNA (−PCSK); group 2, scrambled (−PCSK)) were sacrificed on day 5 without PCSK therapy, and the rectum was removed and evaluated for rectal epithelial Cx43 protein expression at the local site of siRNA application by immunohistochemistry, as described below. The rest (n = 4–5 mice/group; group 3, Cx43siRNA (−PCSK); group 4, Cx43siRNA (+PCSK); group 5, scrambled (−PCSK); group 6, scrambled (+PCSK)) were sacrificed on day 9 with or without PCSK therapy, and the entire colon was removed from cecum to anus, and colon length was measured as a marker of inflammation. For histologic examination, frozen cross-sections (7 μm; every 60 μm) throughout the application site of the rectum were obtained and stained with a hematoxylin-eosin kit (Polysciences). The degree of DSS-induced acute inflammation in the rectum was graded blinded, as described previously (18).

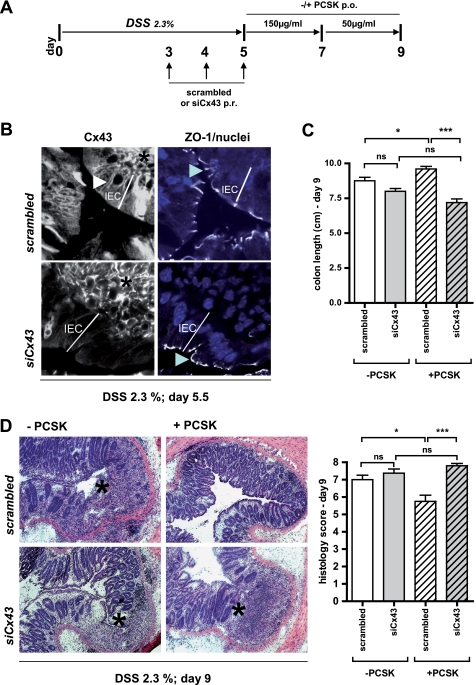

FIGURE 6.

TLR2-mediated IEC wound repair requires functional Cx43 in vivo. A, protocol scheme. WT (C57BL6/J) mice were exposed to DSS (2.3% in drinking water) for 5 days. Liposome-complexed siRNA targeting murine Cx43 or scrambled siRNA were administered per rectum once daily on days 3–5. After DSS exposure, the mice were treated with or without PCSK (days 5–7, 150 μg/ml; days 7–9, 50 μg/ml) and were sacrificed on day 9 (n = 4–5/group). B, to evaluate knockdown of Cx43 in DSS-inflamed rectal EC, control mice (n = 5/group) were sacrificed on day 5½. Compared with scrambled siRNA-treated DSS mice, expression of Cx43 protein (FITC, white, left panel, white arrowhead) was only down-regulated in surface rectal epithelial cells of siCx43-treated DSS mice, but not in deeper crypt areas or underlying lamina propria cells (black asterisk), as assessed by multi-channel confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0). The staining pattern of ZO-1 (CY5, white, right panel, blue arrowhead) remained unchanged following siRNA treatment (nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue)). The depth of surface rectal epithelial cells is marked by the white line. C and D, assessment of colon length (C) and histology (D) score with representative rectal cross-sections (hematoxylin and eosin; 10×) on day 9. The black asterisks indicate ulcers.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections were cut (7 μm) and mounted on Superfrost Plus Gold slides (Thermo). The cells were directly grown on coated culture slides. For detection of murine/human Cx43 (clone CX-1B1), ZO-1, and TLR2, sections were fixed in acetone (100%) for 1 min at −20 °C followed by air-drying and washing with phosphate-buffered saline. The sections were then blocked with normal goat serum (1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline) for 60 min at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies (1:50; for pan-cytokeratin, 1:25) overnight at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor®488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen) and/or CY5/FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) antibodies were used as secondary antibodies (1:100, 60 min, room temperature).

Confocal Laser Microscopy

After mounting with Vectashield mounting medium with propidium iodide or DAPI (Vector Laboratories), immunofluorescent sections were assessed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.3 (oil) or Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 (oil) differential interference contrast objectives; Zeiss Axiovert 100M-LSM 510), as described previously (18, 33). Briefly, the multitrack option of the microscope and sequential scanning for each channel were used to eliminate any cross-talk. All of the images were captured under identical laser settings. The results were only considered significant if more than 80% of the scanned sections/field exhibited the observed effect. Standardized three-dimensional reconstructions and extractions of co-localized areas were generated using LSM 510 v.3.2 software. Control experiments were performed with isotype control IgG (Santa Cruz or Ebioscience) or omitting the primary antibody. All of the experiments were repeated at least twice; representative results are shown for each experiment and subgroup as indicated.

Protein Analysis by Immunoblotting

Proteins from whole colon samples of distal parts were isolated using the T-PER tissue protein extraction reagent (Thermo) supplemented with complete mini protease ± PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor mixture tablets and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride Plus (Roche Applied Science). Dephosphorylation reaction of Cx43 was carried out by incubating tissue lysates for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence (1 unit/μg) of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Promega). ZO-1 was detected in whole colonic samples as described previously (18). The lysates were mechanically disrupted by a tissue disruptor homogenizer (Qiagen). For preparation of subcellular fractions, the ProteoExtract subcellular proteome extraction kit from Merck was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting and mouse 62-cyto/chemokine antibody array III (RayBiotech) were performed as described previously (18, 33). All of the experiments were repeated at least twice; representative results are shown for each experiment.

RNA Extraction and PCR Analysis

Total RNA samples from cells and murine colons were extracted using the RiboPure RNA Isolation kit from Ambion and purified using the RNeasy mini kit with RNase-free DNase from Qiagen, following the manufacturers' instructions. For conventional RT-PCR analysis, reverse transcription of 50 ng of each RNA sample was performed with Sensiscript RT (Qiagen). 2 μl of the RT reaction was used for subsequent PCR (HotStar Taq DNA polymerase; Qiagen) in duplicate. PCR primers (Primer-BLAST, NCBI) were as follows: human Cx43, 5′-GGA CAT GCA CTT GAA GCA GA and 5′-CAG GAG GAG ACA TAG GCG AG (37 cycles); and human ZO-1, 5′-GTC TGC CAT TAC ACG GTC CT and 5′-GGT CTC TGC TGG CTT GTT TC (32 cycles). Species nonspecific GAPDH primers have previously been described (13). Negative controls included water or RNA sample as template. All of the PCR products were resolved by 1–2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA bands were visualized by staining the gel with ethidium bromide. For real time PCR analysis, QuantiTect Primer Assays (Qiagen) were used as the gene-specific primer pairs for human Cx43 (QT00012684), human ZO-1 (QT00077308), human GAPDH (QT01192646), mouse Cx43 (QT00173635), mouse ZO-1 (QT00493899), mouse TFF3 (QT00108857), mouse interferon γ (QT01038821), mouse IL-2 (QT00112315), mouse IL-12p40 (QT00153643), mouse IL-23R (QT00138719), mouse IL-4 (QT00160678), mouse IL-6 (QT00098875), mouse IL-10 (QT00106169), mouse IL-13 (QT00099554), and mouse GAPDH (QT00309099). Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed at least in duplicate using the one-step QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) on the Rotor-Gene 2000 real time amplification system (Corbett Research), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Copy numbers of individual transcripts were normalized in parallel against GAPDH as endogenous control (X/100,000 copies of GAPDH). The mRNA level in untreated cells or tissues (as indicated under “Results”) was defined as 1 arbitrary unit.

Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of two or more independent experiments, as indicated. The differences between means were evaluated using the two-tailed, unpaired t test (GraphPad Prism version 4.03, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), where appropriate. p values of <0.05 were considered as significant.

RESULTS

TLR2 Modulates Cx43 Synthesis in IEC

To determine whether ZO-1 complexes with cellular Cx43 in IEC, we performed co-immunolabeling using confocal laser microscopy. ZO-1 and Cx43 were predominantly localized at the apical and lateral plasma membrane in the human model IEC line Caco-2 (Fig. 1A) and were frequently but not exclusively co-localized at distinct cell-cell contacts (overlay panel) in typical punctuate staining patterns (extracted panel). Constitutive interaction between ZO-1 and Cx43 in Caco-2 cells was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (data not shown).

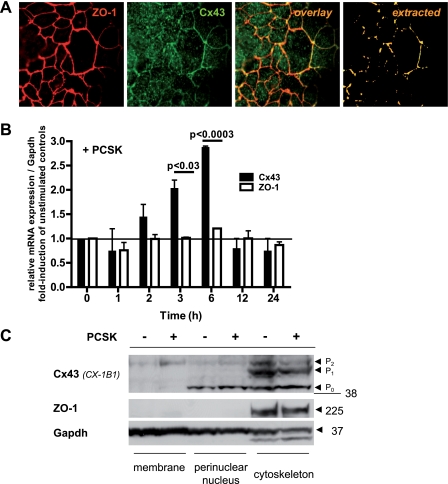

FIGURE 1.

TLR2 modulates Cx43 synthesis and redistribution in IEC. A, ZO-1 (CY5, red) constitutively co-localizes with Cx43 (FITC, green) at the apicolateral membrane in Caco-2 cells, as assessed by confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0). B, increase of Cx43 mRNA expression (3 or 6 h), but not ZO-1 mRNA, in Caco-2 cells by PCSK stimulation (20 μg/ml), as determined by real time RT-PCR analysis. The results are shown in relation to mRNA expression for the housekeeping gene GAPDH and normalized to unstimulated cells. The data are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 2 independent experiments). C, redistribution of Cx43 protein, but not ZO-1, in Caco-2 cells treated with PCSK (20 μg/ml) for 3 h, as determined by Western blotting of subcellular fractions (anti-Cx43, clone CX-1B1).

We next studied the effects of TLR2 in regulating synthesis of the ZO-1-Cx43 complex in IEC. Stimulation of Caco-2 cells with the synthetic TLR2 ligand PCSK increased Cx43 mRNA within 3 h, with a maximum of 3-fold activation after 6 h (Fig. 1B). After 12 h, Cx43 mRNA expression returned to low control levels. Subcellular fractions of intestinal epithelial Cx43 protein electrophoresed as typical multiple isoforms when analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C), including a faster migrating, nonphosphorylated form (P0; ∼42 kDa), and two slower migrating, phosphorylated forms, termed P1 (∼44 kDa) and P2 (∼46 kDa), consistent with previous reports from other cell types (5, 26, 34). PCSK stimulation for 3 h led to redistribution of Cx43-P2 from the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. In contrast, TLR2 stimulation did not modulate ZO-1 gene transcription or protein expression in IEC in vitro.

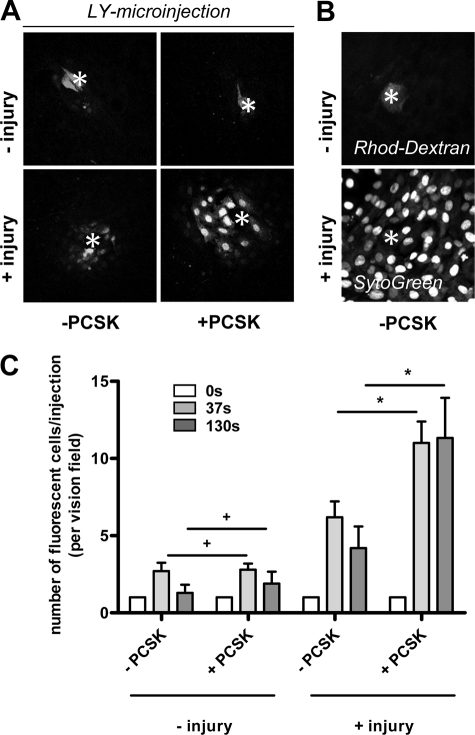

TLR2 Increases GJIC in Single IEC Injury

To analyze intestinal epithelial GJIC functionality in response to TLR2 activation, we next performed microinjection studies to determine the incidence and extent of dye coupling between IEC with or without PCSK treatment. For optimal microinjection conditions, we used IEC-6 cells, which form a simple, confluent monolayer of polyglonal epithelial cells in culture and express both TLR2 (18) and Cx43 (11). IEC-6 cells were microinjected with Lucifer Yellow, which readily passes through GJ (Fig. 2A). Rhodamine-dextran (not transferable through GJ) and SytoGreen (cell-permeant nuclear stain) were used as control markers of cell and nucleus intactness, respectively (Fig. 2B). Under basal conditions, most IEC-6 cells were not dye-coupled (Fig. 2A, upper panel). The presence of PCSK did not increase the efficacy of dye spreading. However, when the IEC-6 cell was injured by microinjection, the incidence of intercellular diffusion was increased, with most cells showing dye coupling with four or five neighboring cells (Fig. 2A, lower panel), suggesting that cellular damage is required to activate GJIC between otherwise quiescent IEC-6 cells. PCSK rapidly increased the extent of dye transfer around single cell injuries, showing 10–11 coupled cells/injection. In addition, GJ-mediated intercellular diffusion was sustained longer in PCSK-treated cells than in untreated cells after injury (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

TLR2 enhances GJ-mediated cell-to-cell coupling in single IEC injury. A, intercellular transfer of Lucifer Yellow (LY) dye microinjected into IEC-6 cells after 37 s and imaged by confocal laser microscopy (40×/0.6 corr Ph2, scan zoom 0.7) in the absence or presence of PCSK stimulation (20 μg/ml). Each microinjected cell is marked by an asterisk. Lucifer Yellow binds to DNA and thus labels nuclei preferentially. Lucifer Yellow dye only diffuses into neighboring cells when the microinjected cell is damaged by the microelectrode after dye filling. Stimulation of TLR2 with PCSK during cell injury leads to progressive penetration of Lucifer Yellow dye to farther layers of surrounded cells. B, representative images of controls are presented: rhodamine (Rhod)-dextran, which exceeds GJ pore size and is retained in the intact IEC-6 cell after microinjection (top panel); Syto Green nuclear counterstaining of confluent IEC-6 monolayers (bottom panel), as assessed by confocal laser microscopy (40×/0.6 corr Ph2, scan zoom 0.7). C, quantitation of IEC-6 dye coupling in the presence or absence of PCSK (20 μg/ml), as assessed by time lapse confocal imaging of microinjected cells with or without injury and evaluated by counting the neighboring fluorescent cells. The data are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3 independent experiments). *, p < 0.05; +, p > 0.05.

TLR2 Mutant Impairs GJIC in Injured IEC because of Proteasome-dependent Degradation of Cx43

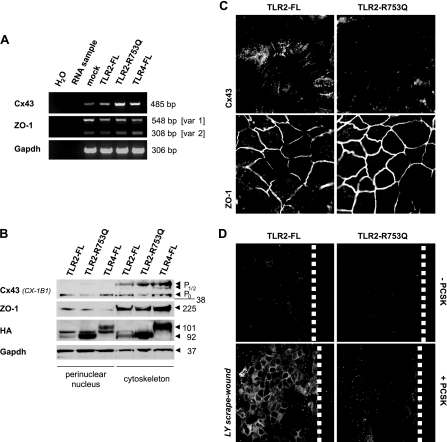

To further substantiate the biological link between TLR2 and GJIC via Cx43 in IEC, we investigated how a common TLR2 mutation may modulate Cx43 synthesis and functionality. We stably transfected the IEC line Caco-2 with HA-tagged TLR2 mutant (TLR2-R753Q) or full-length controls (TLR2-FL and TLR4-FL) and assessed basal Cx43 mRNA and protein expression levels. As shown in Fig. 3A, expression of Cx43 mRNA was constitutively increased in Caco-2 cells overexpressing the TLR2-R753Q mutant, when compared with Caco-2-TLR2-FL or Caco-2-TLR4-FL cells. These findings obtained with conventional RT-PCR were confirmed by real time RT-PCR analysis (data not shown). Cx43 protein is initially synthesized as the Cx43-P0 isoform and gets converted to P½ while being assembled into hemichannels en route from the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi to the plasma membrane (5). However, subcellular protein fractionation demonstrated a significant decrease of the Cx43-P0 isoform in perinuclear and cytoskeleton regions of Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q, which was not evident in cells expressing either full-length control TLR (Fig. 3B). We did not observe any compensating conversions to P½ or shifts to the plasma membrane and cytosol (data not shown), implying that the TLR2-R753Q mutant down-regulates early Cx43 protein expression at post-translational levels. As determined by confocal immunofluorescence, Cx43 protein in Caco-2-TLR2-FL cells (Fig. 3C) or Caco-2-TLR4-FL cells (data not shown) was intracellularly localized in perinuclear punctuate structures and organized as GJ plaques at intercellular contacts, comparable with untransfected Caco-2 cells (Fig. 1A). However, in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells, Cx43 protein was almost completely lost, except for a few signals at cell-cell junctions. Of note, mRNA and protein expression as well as localization of ZO-1 at cytoskeleton-based cell-cell contact sites remained unchanged in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells (Fig. 3, A–C).

FIGURE 3.

TLR2 mutant degrades Cx43 protein, which impairs cell-to-cell communication in IEC wounds. A, increase of base-line mRNA expression levels of human Cx43, but not ZO-1, in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q, when compared with Caco-2-TLR2-FL, Caco-2-TLR4-FL, or Caco-2-mock, as analyzed by conventional RT-PCR. B, decreased constitutive expression of the Cx43-P0 protein form in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q, but not in the other Caco-2 transfectants, as determined by Western blotting of subcellular fractions (anti-Cx43, clone CX-1B1). The lysates were also blotted with anti-ZO-1 confirming specificity and with anti-HA confirming efficiency of stable transfection, respectively. C, down-regulation of Cx43 protein, but not ZO-1, in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q (FITC/CY5, white), as confirmed by confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0). D, failure of GJIC in Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells 8 min after wounding in the presence of PCSK (20 μg/ml), as determined by scrape loading with Lucifer Yellow (LY) dye. Fluorescence views (FITC, white) show representative wound regions of Caco-2-TLR2-FL and Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q monolayers (40×/1.3, oil, scan zoom 1.0). The dashed white lines mark wound margins.

We then evaluated the functional implications of the TLR2 mutant-induced decrease of Cx43 on GJIC by scrape loading dye transfer experiments. Consistent with results using the microinjection technique in IEC-6 cells (Fig. 2C), the efficacy of dye spreading after scrape loading was low in control Caco-2-TLR2-FL cells but significantly increased in the presence of PCSK (Fig. 3D). In contrast, GJIC was functionally inhibited in wounded Cx43-deficient Caco-TLR2-R753Q cells exposed to PCSK, suggesting that Cx43 protein regulates TLR2-induced GJIC.

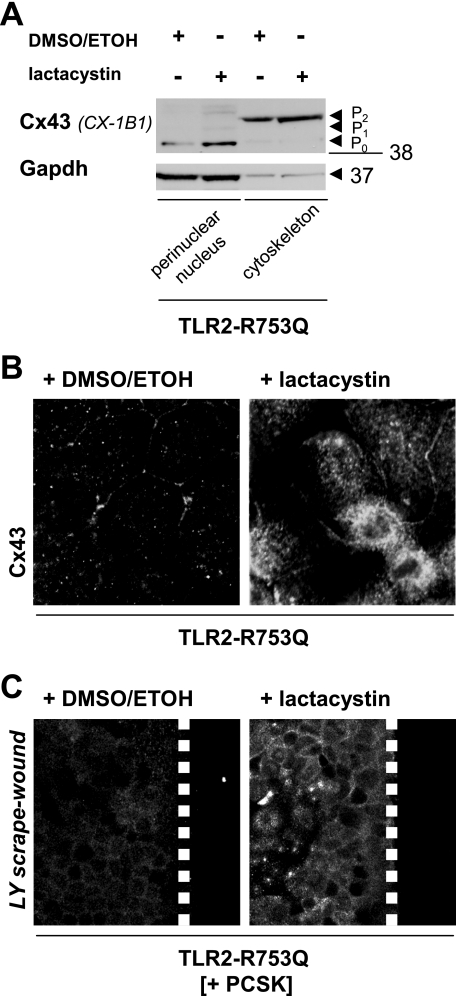

Cellular turnover of Cx43 protein involves balanced proteasome-dependent degradation (35, 36). TLR2 signaling has recently been interconnected with activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (37). To address whether the TLR2 mutant induces the loss of Cx43 protein through aberrant proteasomal activity, we incubated Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells with lactacystin, a specific proteasomal inhibitor that does not affect protein synthesis (38). One hour of treatment with lactacystin counteracted TLR2 mutant-mediated reduction of total Cx43 protein and led to a significant increase of Cx43-P0 in the perinuclear fraction and modest elevation of Cx43-P2 in the cytoskeleton, as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE of Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q subcellular lysates (Fig. 4A). Confocal immunofluorescence confirmed morphologically that lactacystin inhibited degradation of Cx43 protein found in perinuclear compartments and along distinct cell-cell contacts (Fig. 4B). Lactacystin rescued GJIC in wounded Caco-TLR2-R753Q cells when exposed to PCSK (Fig. 4C), indicating that TLR2-induced GJIC depends functionally on the presence of Cx43.

FIGURE 4.

Proteasomal inhibition attenuates increased degradation of Cx43 in TLR2 mutant IEC. A, proteasomal inhibition counteracts TLR2 mutant-mediated perinuclear degradation of Cx43-P0 protein in IEC, as assessed by Western blotting of subcellular fractions (anti-Cx43, clone CX-1B1) of Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q after 1 h of treatment with the specific proteasomal inhibitor lactacystin (30 μm) versus controls (± inhibitor solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide/ethanol (DMSO/EtOH))). B, proteasomal inhibition allows assembly of Cx43 protein in the perinuclear compartment and at cell-cell contacts in TLR2 mutant IEC, as assessed by confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0) with antisera against Cx43 (FITC, white) of Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q after 1 h of treatment with specific proteasomal inhibitor lactacystin (30 μm) versus control (inhibitor solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide/ethanol)). C, restoration of GJIC in PCSK-stimulated (20 μg/ml) Caco-2-TLR2-R753Q cells after 1 h of pretreatment with lactacystin (30 μm) versus control (inhibitor solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide/ethanol)), as determined by scrape loading with Lucifer Yellow (LY) dye. Fluorescence views (FITC, white) show representative wound regions (40×/1.3, oil, scan zoom 1.0). The dashed white lines mark wound margins.

TLR2-deficient IEC Exhibit Loss of Cx43 Protein during Acute Inflammatory Injury in Vivo

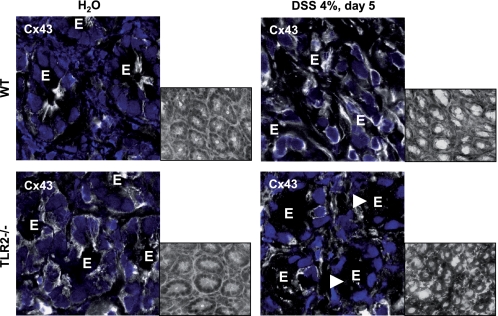

Next, we determined whether the loss of TLR2 function in vivo alters intestinal epithelial Cx43 morphology. Confocal immunofluorescence showed that Cx43 formed small but distinct GJ plaques at the apicolateral pole of IEC in WT colons (Fig. 5). In contrast, TLR2-deficient IEC demonstrated large, sheet-like GJ patches with irregular shapes, shifting into the cytoplasm and surrounding the entire cell. To investigate how intestinal epithelial Cx43 may be modified under conditions of inflammatory stress-induced damage in the presence or absence of TLR2, we used DSS colitis, a well established model of acute intestinal mucosal injury. Although intestinal epithelial Cx43 protein expression was significantly enhanced in DSS-WT colons, Cx43 protein was almost completely lost in TLR2-deficient IEC during the acute phase of DSS colitis (Fig. 5). Of note, intense Cx43 staining was still present in neighboring lamina propria mononuclear cells, implying IEC-specific loss of Cx43 in acute DSS injury in the absence of TLR2.

FIGURE 5.

GJ formation through Cx43 is altered in TLR2-deficient IEC in vivo. Cx43 is irregularly sequestered throughout the cytoplasm, and DSS-induced damage leads to complete loss of Cx43 in IEC, suggesting impairment of GJ pore formation in the absence of TLR2. Representative Cx43 (FITC, white)/propidium iodide (blue) immunofluorescence of the distal WT or TLR2-deficient colon with or without DSS exposure (4% for 5 days), as assessed by confocal laser microscopy (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0). E marks IEC. The white arrowheads indicate representative regions of interest to show the loss of Cx43 in DSS-TLR2−/− IEC. Insets show representative hematoxylin and eosin images (40×; gray-scaled).

Loss of Cx43 in IEC Impairs TLR2-mediated Wound Healing in Acute Inflammatory Injury in Vivo

Activation of GJIC via Cx43 may play an important role in wound repair (39, 40). We have previously shown that the TLR2 ligand PCSK given orally ameliorates mucosal inflammation and accelerates wound healing of the intestinal epithelial barrier in mice with acute DSS colitis (18). We therefore examined whether intestinal epithelial Cx43 expression is required for induction of TLR2-mediated mucosal restitution after acute inflammatory injury in vivo. Because knock-out of Cx43 is lethal in early postnatal life (41), we used mucosal RNA interference to specifically knockdown Cx43 in DSS proctitis. Rectal application of liposome-complexed siRNA has previously been shown to locally mediate gene-specific silencing in the inflamed rectum (32). After protocol adjustments based on the short half-life of Cx43 (Fig. 6A), we administered lipoplex siRNA targeting murine Cx43 or scrambled siRNA to DSS-WT rectum and assessed cell-specific expression of Cx43 protein in the inflamed mucosa on day 5½ (i.e. 77 h after the first siRNA enema). As shown in Fig. 6B, DSS treatment led to a significant increase in mucosal Cx43 protein expression in WT rectums (comparable with Fig. 5), whereas administration of the scrambled siRNA had no effect. In DSS-WT mice receiving Cx43 siRNA, Cx43 protein, but not ZO-1, was decreased in front line IEC at the local site of siRNA enemas in proctitis but remained elevated in underlying lamina propria layers. As described previously (32), siRNA administration had no significant effect on Cx43 in IEC at enema-distant locations in the colon (data not shown). These findings imply that our protocol of liposome-complexed siRNA decreases Cx43 specifically in IEC by day 5½ at the local site of enema application in DSS proctitis. We then continued to treat DSS-siCx43 and DSS-scrambled mice with PCSK at this predefined time point (Fig. 6A). Although PCSK therapy rapidly ameliorated rectal inflammation in DSS-scrambled mice, proctitis in DSS-siCx43 mice was not influenced by treatment with the TLR2 ligand during the acute phase of inflammation (Fig. 6C). Transient absence of Cx43 in IEC delayed PCSK-mediated early wound closure of rectal erosions and ulcerations, as assessed by histology (Fig. 6D) on day 9. The histological phenotype of ulcerative proctitis in PCSK-treated DSS-siCx43 mice was very similar to the phenotypes seen in either untreated DSS-siCx43 or untreated DSS-scrambled mice. Low dose lipoplex siCx43 by itself did not aggravate mucosal disease.

TLR2 Ligand Delays Onset of Chronic Colitis by Protecting GJIC via Cx43 in IEC

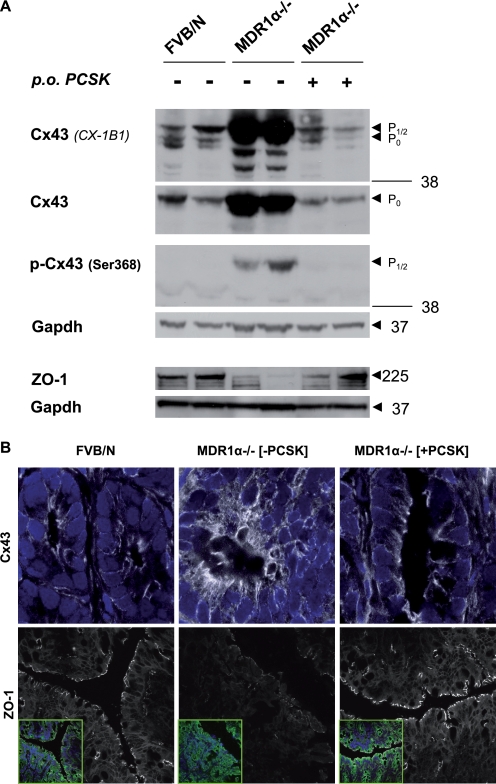

Based on these findings, we examined whether TLR2 stimulation could also prevent spontaneous chronic colitis by modulating GJIC via Cx43 in the IEC barrier. The human MDR1 gene is associated with susceptibility to UC (42). FVB/N mice deficient in MDR1α gene expression spontaneously develop chronic colitis, which resembles UC (43). Disease pathogenesis in MDR1α−/− mice mainly involves a primary IEC barrier dysfunction (44–46); yet possible alterations of distribution and function in intestinal epithelial Cx43 have not been investigated. An increase in Cx43 occurs during cellular injury in a variety of disease models (47). Phosphorylation at Ser368, which specifically decreases Cx43 channel conductivity, represents a functional marker of GJIC disruption during injury (6–9). We therefore investigated total Cx43 protein and Ser368 phosphorylation in MDR1α−/− with or without PCSK prophylaxis. Untreated MDR1α−/− mice with colitis showed accumulation of both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated Cx43 protein expression at 10 weeks of age (Fig. 7A). Untreated colitic MDR1α−/− mice demonstrated a shift toward increased amounts of the P½ isoforms of Cx43 (Fig. 7A; CX-1B1). When these cell lysates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase, all of the accumulated Cx43 converted to the faster migrating P0 form (supplemental Fig. S1), confirming that an increase in both phosphorylated and total Cx43 is generated in inflammatory MDR1α−/− colons. The increase in total Cx43 protein most likely reflected decreased degradation and not increased synthesis, because mRNA levels remained unchanged (data not shown). Probing the same blot (Fig. 7A) with an antibody (p-Cx43) that reacts only with Cx43 phosphorylated at Ser368 showed hyperphosphorylation of Cx43 at this specific site. Examining the morphological distribution by confocal immunofluorescence demonstrated irregular aggregates of increased Cx43 protein in colitic MDR1α−/− IEC, which were scattered diffusely throughout the cytoplasm forming bulky, disruptive GJ plaques at the plasma membrane (Fig. 7B), implying GJIC dysfunctionality. In contrast, ZO-1 mRNA and protein were down-regulated in colitic MDR1α−/− IEC (Fig. 7 and supplemental Table S1). However, treatment with the TLR2 ligand between days 47 and 67 postpartum completely blocked induction of Cx43 accumulation and Ser368 hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 7A and supplemental Fig. S1) and preserved GJ plaque architecture in MDR1α−/− IEC (Fig. 7B). ZO-1 protein remained localized to the apicolateral plasma membrane with a continuous staining pattern.

FIGURE 7.

TLR2 agonist blocks total Cx43 accumulation and its phosphorylation at Ser368 in MDR1α−/− IEC. MDR1α−/− mice (n = 4/group) received PCSK (150 μg/ml in drinking water) for 20 days and were sacrificed on day 67 postpartum. WT controls (FVB/N) were left untreated. A, treatment with the TLR2 ligand PCSK, which blocks induction of Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser368 in MDR1α−/− colons, and assessment of phosphorylation status of Cx43 in whole distal colonic tissues of FVB/N or MDR1α−/− mice (with or without PCSK exposure) by Western blotting (two representative samples are shown per group). Expression patterns of Cx43 forms (anti-Cx43: clones CX-1B1; Z-JB1) are compared with total protein levels of ZO-1. B, severe disruption and alteration of Cx43 (FITC, white) and concomitant loss of ZO-1 (CY5, white) in MDR1 α−/− IEC on day 67, which were prevented by PCSK treatment, as assessed by confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 2.0 (upper panels) or 0.7 (lower panels)). The cells were counterstained with DAPI for nuclei (blue) and anti-pancytokeratin (FITC, green), as presented in insets. Representative immunofluorescent images are shown.

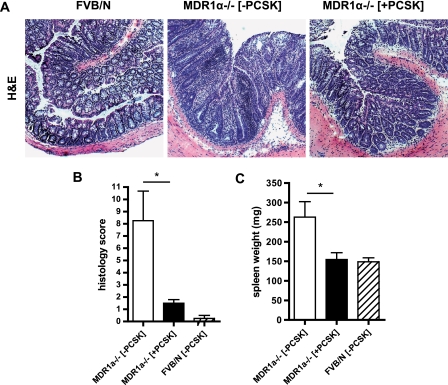

PCSK-mediated prevention of junctional barrier destabilization was associated with inhibition of disease onset (Fig. 8). Histological examination of untreated 10-week-old MDR1α−/− revealed pancolitis with massive thickening of the mucosa, occasional crypt abscesses, and evidence of inflammatory cell infiltrates in the lamina propria that were not evident after 20 days of prophylactic therapy with PCSK (Fig. 8A). Consequently, all colonic tissue sections of PCSK-treated MDR1α−/− demonstrated lower histopathologic scores of chronic colitis (Fig. 8B), which correlated with less cytokine and chemokine expression in MDR1α−/− colons (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Despite the lack of microscopic signs of disease, several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were elevated (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). PCSK control of GJ-mediated antigen transfer through the IEC barrier correlated with prevention of antigen-driven splenomegaly (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Treatment with TLR2 agonist prevents onset of spontaneous colonic inflammation. MDR1α−/− mice (n = 4/group) received PCSK (150 μg/ml in drinking water) for 20 days and were sacrificed on day 67 postpartum. WT controls (FVB/N) were left untreated. A, representative histology of the distal MDR1α−/− colon with or without PCSK treatment on day 67 (H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; 10×). B and C, evolution of histology scores (B) and spleen weight changes (C). The data are presented as the means ± S.E. (−PCSK) versus (+PCSK). *, p < 0.05.

TLR2 Preserves Cx43/ZO-1 Barrier Integrity in Primary Human IEC ex Vivo

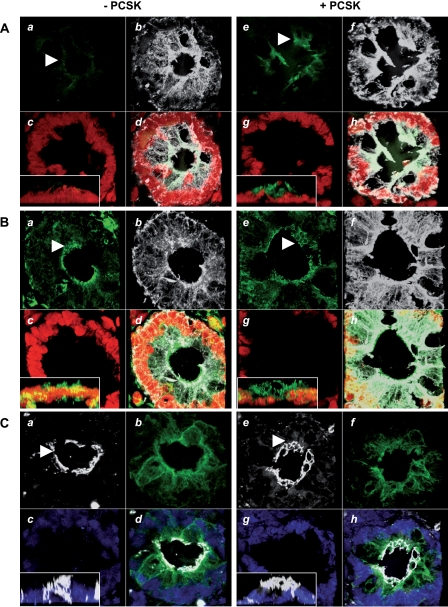

Finally, to validate that TLR2 activation also preserves GJ plaque assembly and associated GJIC in primary human IEC, we cultured human colonic pinch biopsies in a three-dimensional Matrigel-based culture model ex vivo. In the absence of PCSK, only minimal expression of TLR2 was detected in IEC (Fig. 9A), consistent with previous in vivo findings (48). Apicolateral GJ integrity of Cx43 (Fig. 9B) was disrupted, and ZO-1 (Fig. 9C) was found in all planes of flattened IEC clusters. In contrast, PCSK supplementation led to a cuboid three-dimensional geometry of IEC, indicative of polarized organization. TLR2 was present in a punctate pattern on the apicolateral IEC surface (Fig. 9A). In parallel, the typical pattern of the apical Cx43 ring assembly was contained (Fig. 9B) and associated with a well formed ZO-1 belt in three-dimensional cultures (Fig. 9C).

FIGURE 9.

Treatment with PCSK preserves apical GJ/TJ ring formation and barrier polarization in an ex vivo three-dimensional culture model of human colonic biopsies. Shown are apical up-regulation of TLR2 (A, panels a, d, e, and h; FITC, green), preservation of GJ ring formation of Cx43 (B, panels a, d, e, and h; FITC: green), and polarization of ZO-1 (C, panels a, d, e, and h; CY5, white) in PCSK-treated (20 μg/ml; 4.5 h) human colonic pinch biopsies cultured ex vivo in three-dimensional Matrigel, as assessed by confocal immunofluorescence (63×/1.4, oil, scan zoom 1.8 or 2.0). White arrowheads indicate regions of interest. Separate images (0.29-μm spacing) were collected through the region of interest, and three-dimensional reconstruction of 120 stacks was performed. The nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide or DAPI (panels c, d, g, and h; red or blue) and IEC with anti-cytokeratin (panels b, d, f, and h; CY5/FITC, white or green), respectively. Reconstructed Z stack is presented in insets.

DISCUSSION

Commensal bacteria exert several important immune functions that balance mucosal homeostasis in the intestine (49). Commensal-induced TLR2 plays a key role in maintaining functional barrier integrity of the intestinal epithelium (17, 18). In this report we identified a physiological function of TLR2 in the IEC barrier that regulates GJIC through modulation of Cx43 during acute and chronic inflammatory injuries.

The in vitro studies presented here indicated that TLR2 stimulation instantly amplifies GJIC upon acute IEC injury. The TLR2 ligand PCSK may thus serve as a beneficial “alert” signal, communicating to the host the presence of damage and immediate need of appropriate wound repair responses. Increased GJIC coordinates cellular migration processes (39), which are essential to rapid restitution after IEC damage (50). Inhibition of GJIC impairs IEC migration (11). Small molecules exchanged by GJIC may include calcium (51), which serves as a second messenger in TLR2-dependent RhoA signaling (52, 53) and regulates IEC migration (54). Rho GTPases have recently been shown to dynamically modulate GJ permeability (55). Future studies are needed to determine whether TLR2 signaling enhances GJIC in autocrine loops through calcium-dependent RhoA activation in injured IEC.

Our data show that TLR2-mediated induction of GJIC depends functionally on the major GJ protein Cx43. Intestinal epithelial GJIC control by TLR2 involved both transcriptional regulation and post-translational modification of Cx43. TLR2 stimulation up-regulated Cx43 mRNA expression. In parallel, Cx43-P2 protein isoform redistributed to the plasma membrane, which suggests enhanced incorporation of hemichannels into GJ plaques (56) in response to TLR2 activation. Fully assembled GJ plaques have a rapid turnover with an estimated half-life of only 1.5 h (57). No significant change in total Cx43 protein amount was detected, suggesting that PCSK-mediated increase of Cx43 mRNA synthesis sufficiently replenishes the intracellular Cx43 pool maintaining stable protein levels. Cx43 constitutively co-localized with ZO-1, which is known to assist in regulation of GJ size and stability (21, 22). We have previously shown that TLR2 stimulation leads to immediate but transient trafficking of ZO-1 to the apical pole of IEC (17). Here, our results indicate that longer stimulation with PCSK primarily affects dynamics of Cx43 but neither synthesis nor recompartimentalization of its partner ZO-1.

Our findings demonstrate that IEC-specific deficiency of Cx43 impairs TLR2-induced GJIC during acute barrier injury. The absence of TLR2 induced loss of Cx43 in inflamed IEC, which correlated with increased morbidity and mortality in acute colitis (18). Down-regulation of Cx43-IEC by siRNA led to abrogation of TLR2-mediated IEC barrier restitution and delayed wound closure in acute inflammatory stress-induced injury in the intestine. Lack of Cx43 may diminish the passage of migration-stimulatory signals (40) via TLR2 signaling to cells at the IEC wound edge. Although the effect of mucosal RNA interference targeting IEC-specific Cx43 was transient and only limited to the local site of application in DSS proctitis, our data provide mechanistic proof-of-principle that TLR2-dependent induction of mucosal barrier healing requires intestinal epithelial Cx43 in vivo.

The anti-inflammatory effects of PCSK via TLR2 in acute chemically induced colitis have been shown previously (18). We now demonstrate that prophylaxis with this TLR2 ligand prevents spontaneous onset of chronic colitis. Pathogenesis of commensal-driven pancolitis in FVB/N mice deficient in MDR1α gene expression involves primary IEC barrier dysfunction associated with alterations in interferon γ-responsive genes in the lamina propria (43–46). Despite presence of CC-chemokines and pro-inflammatory interferon γ in the mucosal milieu, which disrupt Cx43 (11, 58), treatment with PCSK suppressed inflammatory induced accumulation, Ser368 phosphorylation, and morphological disruption of Cx43 in intestinal epithelial cells in parallel with delayed onset of mucosal disease. Collectively, the findings of this study show that a commensal-derived TLR2 ligand (59) protects the local mucosa by preservation of GJ/TJ-associated architecture and GJIC. However, when activated by pathogenic bacteria, TLR2 has previously been shown to disrupt GJIC in airway epithelial cells by induction of c-Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Cx43 (60), presumably aiming at protecting the host from bacterial invasion and dissemination through GJs (61). Thus, the outcome of innate immune regulation of differential GJIC functionality via TLR2 may depend on target organ barrier and conditions (commensals versus pathogens).

The mechanism of negative control through TLR2 signaling that abolishes hyperphosphorylation of Cx43 in MDR1α−/− colitis remains to be defined, including the possible role of interference by different protein kinase C isoforms and p42/p44 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase; Ref. 6, 7, and 17). Tolerance represents an essential mucosal defense mechanism maintaining intestinal hyporesponsiveness to luminal LPS. Induction of cross-tolerance (15) via TLR2 could contribute to inhibition of stress-induced decreased degradation and hyperphosphorylation of Cx43. Colitis in MDR1α-deficient mice appears to depend on the presence of LPS (44). Aberrant LPS signaling via TLR4 may alter the phosphorylation state of Cx43 (62). Treatment with a TLR4 antagonist inhibits the development of disease in MDR1α−/− by blocking the interaction of LPS with the immune system (63). The continuous presence of the TLR2 agonist PCSK by long term administration in relatively high concentrations may elicit LPS hyporesponsiveness in MDR1α-deficient mice, preventing LPS-induced Cx43 disruption and associated exaggeration of inflammatory responses in this genetically susceptible host.

Approximately 3–10% of Caucasians are heterozygous for the TLR2 polymorphism R753Q (64), which has recently been associated with a more severe disease phenotype in UC patients (65). We now demonstrate that the UC-associated TLR2-R753Q mutant exhibits a pathophysiological defect in intestinal epithelial GJIC. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent pathway is important in regulating endocytosis and subsequent proteolysis of Cx43 (35, 36). Overexpression of TLR2-R753Q did not directly reduce Cx43 synthesis but induced misrouted activation of the proteasome in IEC, which led to excessive degradation of the Cx43 protein, thus impairing GJIC during wounding. Proteasomal inhibition interfered with connexin degradation, which restored TLR2-mediated GJIC in IEC wounds. The link between the proteasome and TLR2-R753Q remains to be delineated at a molecular level. In preliminary array studies, we were not able to detect any significant mutant-dependent alterations of cyto-/chemokine secretion that may have caused the observed effects (data not shown). Proteasomal activity controls mucosal homeostasis in the intestine, and its imbalance may trigger intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases (66). Altered composition and activity of the 20 S proteasome complex by the R753Q mutant could be responsible for the reduction of Cx43 seen in the inflamed gut of some inflammatory bowel disease patients (11), contributing to extensive mucosal disease caused by innate immune deficiency of transferring commensal-mediated host repair responses to the front line of barrier injury.

Finally, to assess the role of TLR2 stimulation on the GJ/TJ-associated barrier of primary human IEC, we used an ex vivo three-dimensional model system of human colonic biopsies cultured short term with or without PCSK. Our results show that TLR2 is specifically up-regulated in response to PCSK in normal human primary IEC, which correlates with preservation of Cx43/ZO-1-associated barrier integrity and polarization. Yet human TLR2 expression is down-regulated in inflamed epithelium from UC patients (48), potentially impairing wound repair because of dysfunctional GJIC.

In conclusion, these studies provide the first evidence that TLR2 controls GJIC by modulating intestinal epithelial Cx43. They suggest that Cx43 deficiency results in a defect of TLR2-mediated wound repair during intestinal injury. Aberrant TLR2 mutant signaling impairs Cx43-mediated GJIC. Proteasomal-dependent hyperdegradation of Cx43 in enterocytes may functionally contribute to the more severe disease phenotype in UC patients with TLR2 mutant haplotype. Taken together, our findings provide a rationale for targeting the innate immune TLR2-Cx43-GJIC-axis in prophylaxis and therapy of human gastrointestinal diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Nierobis (GI Unit, University Hospital, Essen, Germany) for contributions and assistance during the project start-up phase and Dr. M. Rünzi (Kliniken Essen-Süd, Essen, Germany) for kindly providing human colonic biopsies. We also thank Dr. M. A. Alaoui-Jamali (McGill University, Montréal, Canada) and Dr. S. J. Lye (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Canada) for generously providing reagents during the study course and Dr. S. O. Mikalsen (Institute for Cancer Research, Oslo, Norway) for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) Senior Research Award 1790 (to E. C.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant Ca226/4-2 (to E. C.), and a grant from IFORES (to E. C.). This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK60049 (to D. K. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Fig. S1.

- IEC

- intestinal epithelial cell(s)

- Cx43

- connexin-43

- DSS

- dextran sodium sulfate

- GJ

- gap junction

- GJIC

- gap junctional intercellular communication

- MDR1

- multidrug resistance gene

- TJ

- tight junction

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- UC

- ulcerative colitis

- WT

- wild type

- ZO-1

- zonula occludens-1

- PCSK

- Pam3CysSK4

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- FL

- full-length

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- RT

- reverse transcription

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Podolsky D. K. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277, G495–G499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sartor R. B. (2008) Gastroenterology 134, 577–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laird D. W. (2006) Biochem. J. 394, 527–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White T. W., Paul D. L. (1999) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61, 283–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musil L. S., Cunningham B. A., Edelman G. M., Goodenough D. A. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 2077–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lampe P. D., TenBroek E. M., Burt J. M., Kurata W. E., Johnson R. G., Lau A. F. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149, 1503–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards T. S., Dunn C. A., Carter W. G., Usui M. L., Olerud J. E., Lampe P. D. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167, 555–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao X., Reuss L., Altenberg G. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20058–20066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ek-Vitorin J. F., King T. J., Heyman N. S., Lampe P. D., Burt J. M. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, 1498–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubina M. V., Iatckii N. A., Popov D. E., Vasil'ev S. V., Krutovskikh V. A. (2002) Oncogene 21, 4992–4996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leaphart C. L., Qureshi F., Cetin S., Li J., Dubowski T., Baty C., Beer-Stolz D., Guo F., Murray S. A., Hackam D. J. (2007) Gastroenterology 132, 2395–2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velasquez Almonacid L. A., Tafuri S., Dipineto L., Matteoli G., Fiorillo E., Morte R. D., Fioretti A., Menna L. F., Staiano N. (2008) Vet. J. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cario E., Rosenberg I. M., Brandwein S. L., Beck P. L., Reinecker H. C., Podolsky D. K. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cario E., Brown D., McKee M., Lynch-Devaney K., Gerken G., Podolsky D. K. (2002) Am J. Pathol. 160, 165–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otte J. M., Cario E., Podolsky D. K. (2004) Gastroenterology 126, 1054–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medzhitov R. (2007) Nature 449, 819–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cario E., Gerken G., Podolsky D. K. (2004) Gastroenterology 127, 224–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cario E., Gerken G., Podolsky D. K. (2007) Gastroenterology 132, 1359–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giepmans B. N., Moolenaar W. H. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 931–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyofuku T., Yabuki M., Otsu K., Kuzuya T., Hori M., Tada M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12725–12731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh D., Solan J. L., Taffet S. M., Javier R., Lampe P. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30416–30421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter A. W., Barker R. J., Zhu C., Gourdie R. G. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5686–5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soong G., Reddy B., Sokol S., Adamo R., Prince A. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1482–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlois S., Cowan K. N., Shao Q., Cowan B. J., Laird D. W. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 912–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nusrat A., Parkos C. A., Verkade P., Foley C. S., Liang T. W., Innis-Whitehouse W., Eastburn K. K., Madara J. L. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 1771–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruciani V., Mikalsen S. O. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 251, 285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leykauf K., Salek M., Bomke J., Frech M., Lehmann W. D., Dürst M., Alonso A. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 3634–3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solan J. L., Fry M. D., TenBroek E. M., Lampe P. D. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 2203–2211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizoguchi E., Mizoguchi A., Takedatsu H., Cario E., de Jong Y. P., Ooi C. J., Xavier R. J., Terhorst C., Podolsky D. K., Bhan A. K. (2002) Gastroenterology 122, 134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen D. D., Maillard M. H., Cotta-de-Almeida V., Mizoguchi E., Klein C., Fuss I., Nagler C., Mizoguchi A., Bhan A. K., Snapper S. B. (2007) Gastroenterology 133, 1188–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merx S., Neumaier M., Wagner H., Kirschning C. J., Ahmad-Nejad P. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 1225–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Cristofaro P., Silbermann R., Pusch O., Boden D., Konkin T., Hovanesian V., Monfils P. R., Resnick M., Moss S. F., Ramratnam B. (2006) Mol. Ther. 14, 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cario E., Golenbock D. T., Visintin A., Rünzi M., Gerken G., Podolsky D. K. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 4258–4266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lampe P. D., Lau A. F. (2000) Arch Biochem. Biophys. 384, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laing J. G., Beyer E. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26399–26403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leithe E., Rivedal E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50089–50096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xue Y., Yun D., Esmon A., Zou P., Zuo S., Yu Y., He F., Yang P., Chen X. (2008) J. Proteome. Res. 7, 3180–3193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenteany G., Standaert R. F., Lane W. S., Choi S., Corey E. J., Schreiber S. L. (1995) Science 268, 726–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pepper M. S., Spray D. C., Chanson M., Montesano R., Orci L., Meda P. (1989) J. Cell Biol. 109, 3027–3038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwak B. R., Pepper M. S., Gros D. B., Meda P. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 831–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reaume A. G., de Sousa P. A., Kulkarni S., Langille B. L., Zhu D., Davies T. C., Juneja S. C., Kidder G. M., Rossant J. (1995) Science 267, 1831–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwab M., Schaeffeler E., Marx C., Fromm M. F., Kaskas B., Metzler J., Stange E., Herfarth H., Schoelmerich J., Gregor M., Walker S., Cascorbi I., Roots I., Brinkmann U., Zanger U. M., Eichelbaum M. (2003) Gastroenterology 124, 26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilk J. N., Bilsborough J., Viney J. L. (2005) Immunol. Res. 31, 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panwala C. M., Jones J. C., Viney J. L. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 5733–5744 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resta-Lenert S., Smitham J., Barrett K. E. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 289, G153–G162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collett A., Higgs N. B., Gironella M., Zeef L. A., Hayes A., Salmo E., Haboubi N., Iovanna J. L., Carlson G. L., Warhurst G. (2008) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 14, 620–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.VanSlyke J. K., Musil L. S. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 381–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cario E., Podolsky D. K. (2000) Infect Immun. 68, 7010–7017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hooper L. V., Wong M. H., Thelin A., Hansson L., Falk P. G., Gordon J. I. (2001) Science 291, 881–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciacci C., Lind S. E., Podolsky D. K. (1993) Gastroenterology 105, 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charles A. C., Naus C. C., Zhu D., Kidder G. M., Dirksen E. R., Sanderson M. J. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 118, 195–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teusch N., Lombardo E., Eddleston J., Knaus U. G. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chun J., Prince A. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 1330–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santos M. F., McCormack S. A., Guo Z., Okolicany J., Zheng Y., Johnson L. R., Tigyi G. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100, 216–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Derangeon M., Bourmeyster N., Plaisance I., Pinet-Charvet C., Chen Q., Duthe F., Popoff M. R., Sarrouilhe D., Hervé J. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30754–30765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Musil L. S., Goodenough D. A. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 115, 1357–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laird D. W., Castillo M., Kasprzak L. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medeiros G. A., Silverio J. C., Marino A. P., Roffe E., Vieira V., Kroll-Palhares K., Carvalho C. E., Silva A. A., Teixeira M. M., Lannes-Vieira J. (2009) Microbes Infect. 11, 264–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Punturieri A., Copper P., Polak T., Christensen P. J., Curtis J. L. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 673–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin F. J., Prince A. S. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 4986–4993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tran Van Nhieu G., Clair C., Bruzzone R., Mesnil M., Sansonetti P., Combettes L. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 720–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lidington D., Tyml K., Ouellette Y. (2002) J. Cell. Physiol. 193, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fort M. M., Mozaffarian A., Stöver A. G., Correia Jda S., Johnson D. A., Crane R. T., Ulevitch R. J., Persing D. H., Bielefeldt-Ohmann H., Probst P., Jeffery E., Fling S. P., Hershberg R. M. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 6416–6423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schröder N. W., Hermann C., Hamann L., Göbel U. B., Hartung T., Schumann R. R. (2003) J. Mol. Med. 81, 368–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pierik M., Joossens S., Van Steen K., Van Schuerbeek N., Vlietinck R., Rutgeerts P., Vermeire S. (2006) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Visekruna A., Joeris T., Seidel D., Kroesen A., Loddenkemper C., Zeitz M., Kaufmann S. H., Schmidt-Ullrich R., Steinhoff U. (2006) J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3195–3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.