Abstract

The A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) is coupled to Gi/Go proteins, but the downstream signaling pathways in smooth muscle cells are unclear. This study was performed in coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMCs) isolated from the mouse heart [A1AR wild type (A1WT) and A1AR knockout (A1KO)] to delineate A1AR signaling through the PKC pathway. In A1WT cells, treatment with (2S)-N6-(2-endo-norbornyl)adenosine (ENBA; 10−5M) increased A1AR expression by 150%, which was inhibited significantly by the A1AR antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (10−6M), but not in A1KO CASMCs. PKC isoforms were identified by Western blot analysis in the cytosolic and membrane fractions of cell homogenates of CASMCs. In A1WT and A1KO cells, significant levels of basal PKC-α were detected in the cytosolic fraction. Treatment with the A1AR agonist ENBA (10−5M) translocated PKC-α from the cytosolic to membrane fraction significantly in A1WT but not A1KO cells. Phospholipase C isoforms (βI, βIII, and γ1) were analyzed using specific antibodies where ENBA treatment led to the increased expression of PLC-βIII in A1WT CASMCs while having no effect in A1KO CASMCs. In A1WT cells, ENBA increased PKC-α expression and p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phospohorylation by 135% and 145%, respectively. These effects of ENBA were blocked by Gö-6976 (PKC-α inhibitor) and PD-98059 (p42/p44 MAPK inhibitor). We conclude that A1AR stimulation by ENBA activates the PKC-α signaling pathway, leading to p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in CASMCs.

Keywords: A1 adenosine receptor agonist, coronary artery smooth muscle, protein kinase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling

molecular and pharmacological studies have demonstrated the existence of four adenosine receptor (AR) subtypes: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 (5, 17). All these receptor subtypes are coupled to G proteins (7, 9). Subsequent to binding with its receptor (s), adenosine initiates signaling cascades, and the most-characterized mechanism is the effect on adenylate cyclase (9). The activation of MAPK by G protein-coupled receptors can occur by several mechanisms. This activation may be dependent on or independent of PKA, PKC, Src tyrosine kinase, or Ras activation and involves the cross-activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (16, 21).

Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms found in eukaryotes comprise a related group of proteins that cleave the polar head group from phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphate.

The best-documented consequence of this reaction is the generation of two second messengers: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, a universal Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger, and diacylglycerol, an activator of several PKC isoforms (18, 19). In the past years, several mammalian PLC isoforms have been isolated, and their corresponding cDNA sequences have been determined. According to sequence similarity, these isoforms have been classified into three families: β, γ, and δ. The PLC-β isoform was identified to be coupled to A1ARs in rabbit intestine smooth muscle membranes by Murthy and Makhlouf (15). However, the isoform coupled to A1AR activation in coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMCs) has not yet been characterized.

The PKC family of serine/threonine protein kinases plays critical roles in many signal transduction pathways in the cell (12, 33). Eleven distinct isozymes have been identified in the mammalian cell. These have been divided into three subfamilies: 1) conventional or Ca2+-dependent isozymes (α, βI, βII, and γ); 2) novel or Ca2+-indedependent isozymes (δ, η, ɛ, and θ); and 3) atypical isozymes (ζ and λ/ι) (23). A previous study (9) from our laboratory has demonstrated that 2-chloro-adenosine (CAD) upregulates PKC in the porcine coronary artery, where it has been shown that prolonged exposure to CAD alone protects the activation and depletion of PKC by phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate. Marala and Mustafa (10, 11) demonstrated that A1AR-mediated upregulation of PKC is blocked by pertussis toxin, indicating the involvement of Gi/Go protein coupling. The activation of A1ARs also causes contraction through PLC in the A1AR wild-type (A1WT) mice aorta and a decrease in coronary flow in the A1WT mouse heart (29, 30). However, the exact mechanism of A1AR-mediated regulation of PKC and its role in vascular contraction are not yet fully understood.

There have been three major subfamilies of structurally related MAPKs identified in mammalian cells, which are termed p42/44 MAPK (ERK1/2), p38 MAPK, and JNK/SAPKs. The activation of the p42/44 MAPK (ERK1/2) pathway is an important cell signaling mechanism regulating multiple cell functions (16, 21). The A1AR specifically has been shown to activate p42/44 MAPK (ERK 1/2) in different cell lines in previous studies (8, 20, 25, 26). However, the importance of p42/44 MAPK (ERK 1/2) signaling and its relationship with PKC in causing A1AR-mediated contraction in vasculature are unknown.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of A1AR activation on PKC and PLC isoforms and p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) signaling using CASMCs from A1WT and A1AR knockout (A1KO) mice. Our data show that A1AR activation by (2S)-N6-(2-endo-norbornyl)adenosine (ENBA) activates PKC-α through PLC-βIII, leading to p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation in CASMCs and contraction of the vascular smooth muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The A1AR agonist ENBA and its antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) as well as PD-98059 and A1AR antibody were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). 12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)carbazole (Gö-6976) was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). PKC isoforms (α, β, and γ) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA). PLC isoforms (βI, βIII, and γ1), ERK, and β-actin antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). FBS and mouse serum were obtained from Equitech Bio (Kerrville, TX). All other cell culture supplies were obtained from GIBCO-BRL (Gaithersburg, MD).

Mice.

The generation and initial characterization of A1WT and A1KO mice on a C57BL/6 background have been previously described (28). Heterozygous (+/−) mice were bred to obtain A1WT and A1KO mice. Male and female mice (8–12 wk old) were used in all experiments. All animal care and experimentation were approved and carried out in accordance with West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Cell culture.

CASMCs were isolated from 8- to 12-wk old A1WT and A1KO mice as previously described by our laboratory (31). Briefly, hearts from anesthetized mice were excised with an intact aortic arch and immersed in a petri dish filled with ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer. A 25-gauge needle filled with HBSS [containg (in mM) 5.0 KCl, 0.3 KH2PO4, 138 NaCl, 4.0 NaHCO3, 0.3 Na2HPO4·7H2O, 5.6 d-glucose, and 10.0 HEPES with 2% antibiotics] was inserted into the aortic lumen opening while the whole heart remained in the ice-cold buffer solution. The opening of the needle was inserted deep into the heart close to the aortic valve. The heart with the aortic notch was tied to the needle, and warm HBSS was passed through an intravenous extension set via an infusion pump at a rate of 0.1 ml/min for 15 min. HBSS was replaced with warm enzyme solution (1 mg/ml collagenase type I, 0.5 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 3% BSA, and 2% antibiotic-antimycotic), which was flushed through the heart at a rate of 0.1 ml/min. Cells in the perfusion fluid were centrifuged at 200 g for 7 min, and the cell-rich pellet was resuspended in equal parts of DMEM and Ham's F-12 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 10% (vol/vol) mouse serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B in 5% CO2-95% O2 at 37°C in a cell culture incubator. Smooth muscle cells were subcultured at a split ratio of 1:4 using 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA. CASMCs were identified and characterized as previously described by our laboratory (31).

Preparation of the isolated mesenteric artery for wire myograph experiments.

Intestines from A1WT and A1KO mice were excised and placed in oxygenated (5% CO2-95% O2) modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer [containing (in mM) 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 15 glucose, and 0.05 EDTA] at 37°C and pH 7.4. First-order branches of the mesenteric artery were isolated and cleaned of surrounding tissue. Arterial rings (3–5 mm long, 50∼100 μm inside diameter) were mounted on an isometric myograph (Danish Myo Techology, Aarhus, Denmark) as described by Mulvany and Nyborg (14). Each vascular ring was stretched to a resting tension (200 mg) that consisted mainly of passive tension and was allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 min. The optimal resting tension was determined by measuring the tension that produced the greatest contractile response after the addition of 50 mM KCl. The viability of the vascular ring was tested with 50 mM KCl, and integrity of the endothelium was confirmed by ACh (10−7 M). Vascular rings that did not contract after the addition of KCl or that relaxed <50% after the addition of ACh were eliminated from further study.

Western blot analysis for PKC isoforms in the membrane and cytosolic fractions.

CASMCs were maintained in serum-free media for 16 h. Cells were then treated with or without the A1AR agonist ENBA (10−5 M) for 100 min. To detect PKC isoforms in the cytosolic and membrane fractions, cells were lysed in Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 0.3 M sucrose, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM NaF, and protease cocktail inhibitor using 20-gauge syringes followed by centrifugation at 600 g for 10 min at 4°C. To separate the cytosolic and membrane fractions, the supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant served as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and served as the membrane fraction. Proteins were measured by the Bradford method (3) using BSA as the standard. For the measurement of the PKC α-isoform with and without pretreatment with PKC inhibitor in the membrane fraction, cells were pretreated with Gö-6976 (10−7 M) for 30 min before the addition of ENBA (10−5 M) for 100 min. Prestained Kaleidoscope (range: 7.1–208 kDa) and SDS-PAGE (low range: 20.5–112 kDa) standards were run in parallel as protein molecular weight markers. Equal amounts (40 μg) of protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk followed by an incubation with anti-PKC isoform antibodies (1: 1,000) for 16 h at 4°C with gentle shaking. After being washed, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG at 1:3,000) for 1 h at 20°C. For chemiluminescent detection, membranes were treated with ECL reagent for 1 min and subsequently exposed to ECL hyperfilm for 1–2 min. The band density of the protein was quantified by densitometry (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA), and values are expressed as percentages of control after normalization with β-actin values as previously described by our laboratory (2).

Western blot analysis for PLC isoforms, p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2), and A1ARs.

CASMCs were starved in serum-free medium for 16 h before the addition of the agonist/antagonist. Cells were treated with ENBA (100 min), and PLC isoforms were detected using specific antibodies for PLC-βI, PLC-βIII, and PLC-γ1 in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs. For the measurement of p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2, total and phosphorylated forms), cells were pretreated with the PKC inhibitor Gö-6976 (10−7 M) and the MAPK inhibitor PD-98059 (10−5M) for 30 min before the addition of ENBA (10−5 M) for 10 min. At the end of the incubation period, cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 50 μg/ml aprotinin]. Forty micrograms of protein per lane were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with PLC-βI-, PLC-βIII-, and PLC-γ1-specific antibodies for PLC isoform detection and anti-phospho-p42/p44 MAPK (p-ERK1/2; 1:400) and anti-p42/p44 MAPK antibodies (1:400) for total p42/p44 MAPK (ERK) detection, followed by an incubation with secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG at 1:3,000 dilution) for 1 h at 20°C. A1AR expression was measured in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs with and without A1AR agonist (ENBA; 10−5 M; 100 min) treatment. The A1AR antagonist DPCPX (10−5M) was used 30 min before ENBA treatment to assess A1AR expression in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs. For Western immunoblot analysis, protein samples (40 μg protein/lane) of A1WT and A1KO CASMCs were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, elctrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with anti-A1AR antibody (1:1,000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature, and incubated with secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at 1:5,000 dilution) for 1 h at 20°C. Relative band intensities were determined as described above.

Immunofluorescence experiments for PKC-α.

Cells were plated on glass coverslips in 35-mm petri dishes until they reached subconfluence. Plated cells were then treated with ENBA (10−5M) for 100 min. For the measurement of PKC-α immunoreactivity with the PKC inhibitor, cells were pretreated with Gö-6976 (10−7 M) for 30 min before the addition of ENBA (10−5 M) for 10 min. Culture medium was first removed by aspiration, and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 5% Triton-X100. Cells were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. Mouse anti-PKC-α monoclonal antibody (1:1,000) was added, and samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed and subsequently incubated for 1 h with anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:50) followed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (1:1,000) for 1 min. After several washes, the coverslips were mounted with Vectashield mounting solution and examined on a Nikon Eclipse 300 upright microscope (Mississauga, ON, Canada) equipped with a Cool Snap fx digital camera (Roper Scientific, Hinsdale, IL). Images were acquired using a ×100 oil-immersion objective.

Data analysis.

Values are presented as means ± SE; n is the number of experiments using different animals/batches of CASMCs isolated from separate animals. Comparisons among different groups were performed with ANOVA followed by Tukey's method as a post hoc test. Comparisons between two groups were assessed by unpaired t-tests. P < 0.05 was taken as significant. All of the statistical analyses were performed using the Graph Pad Prism statistical package (version 3.0).

RESULTS

Functional (contraction) confirmation of A1AR-mediated signaling through PKC-α and MAPK in A1WT and A1KO mouse mesenteric arteries.

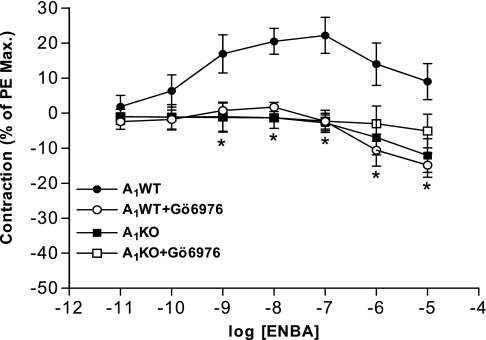

These experiments were conducted using a wire myograph to delineate the role of A1AR-mediated signaling in causing contraction. Treatment with the A1AR agonist ENBA increased contraction in a concentration-dependent manner in A1WT mesenteric arteries (Fig. 1). ENBA-induced contraction was ≈22% at 10−7 M in A1WT mouse mesenteric arteries, whereas no contraction was noted in A1KO arteries. ENBA-induced contraction in A1WT mesenteric arteries was significantly blocked by the PKC-α inhibitor Gö-6976 (10−7 M). The MAPK inhibitor PD-98059 (10−5 M) also blocked ENBA-induced contraction and shifted the curve toward the right with EC50 values being 0.77 and 16.54 nM for ENBA and ENBA + PD-98059, respectively (data not shown; n = 4). These data suggest that A1AR-mediated contraction in smooth muscle is via PKC-α and MAPK signaling pathways.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the PKC-α inhibitor Gö-6976 on (2S)-N6-(2-endo-norbornyl) adenosine (ENBA)-induced contractile responses in A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) wild-type (A1WT) and A1AR knockout (A1KO) mouse mesenteric arteries. PE, phenylephine. Results are expressed as means ± SE; n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with A1WT (untreated) controls.

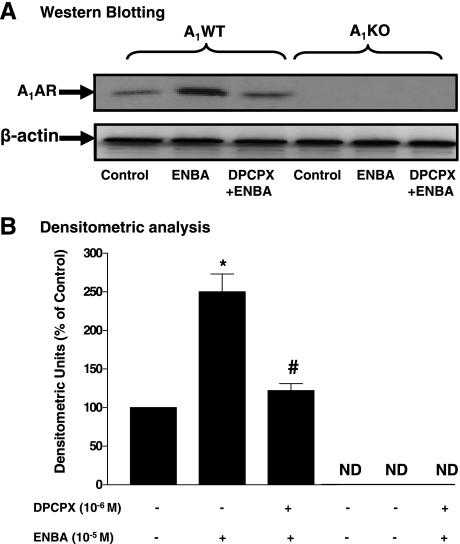

ENBA-induced A1AR expression in A1WT and A1KO mouse CASMCs.

To delineate the A1AR signaling pathways leading to vascular contraction, further experiments were carried out in CASMCs. A1AR protein expression (36 kDa) was prominently expressed in A1WT CASMCs, whereas it was undetected in A1KO CASMCs. The A1AR agonist ENBA increased A1AR protein expression by 150% (P < 0.05) compared with the control. Pretreatment of A1WT CASMCs with DPCPX (10−6 M) before ENBA significantly inhibited the ENBA-induced increase in A1AR expression (Fig. 2). A1AR expression was undetected in the absence or presence of ENBA and DPCPX in A1KO CASMCs.

Fig. 2.

A1AR protein expression in A1WT and A1KO coronary artery smooth muscle cells (CASMCs). A: Western blot analysis. DPCPX, 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine. B: densitometric analysis. ND, not detected. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 5–7. *P < 0.05 compared with A1WT (untreated) controls; #P < 0.05 compared with ENBA alone.

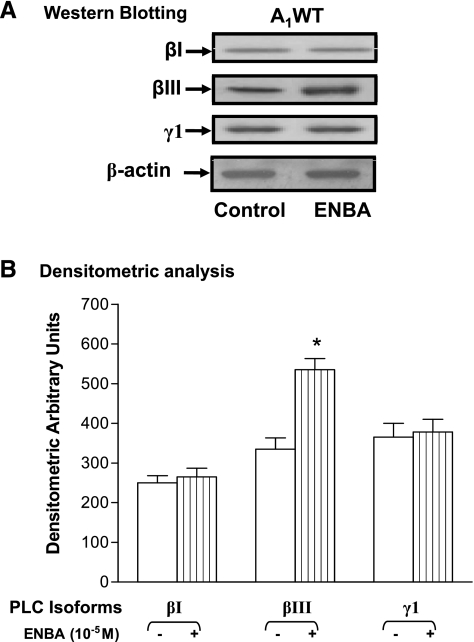

ENBA-induced PLC expression in A1WT and A1KO mouse CASMCs.

As shown in Fig. 3, ENBA-induced PLC protein (βI, βIII, and γ1) expression were analyzed using specific antibodies to these proteins in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs. The results (in arbitrary densitometric units) indicated that ENBA increased PLC-βIII (150 kDa) expression by 64% (P < 0.05) over control (untreated) in A1WT CASMCs, whereas the expression of PLC-βI (150 kDa) and PLC-γ1 (155 kDa) was unaltered in A1WT CASMCs compared with their corresponding controls (untreated). A1KO CASMCs did not show any differences between ENBA treatment and their respective controls for PLC-βI, PLC-βIII, and PLC-γ1 expression (data not shown). These data suggest that ENBA activates mainly PLC-βIII through A1ARs in A1WT CASMCs.

Fig. 3.

Phospholipase C (PLC) isoform (βI, βIII, and γ1) expression in A1WT CASMCs. A: Western blot analysis for PLC isoforms. B: densitometric analysis. data are presented as means ± SE; n = 3–4. *P < 0.05 compared with the respective controls.

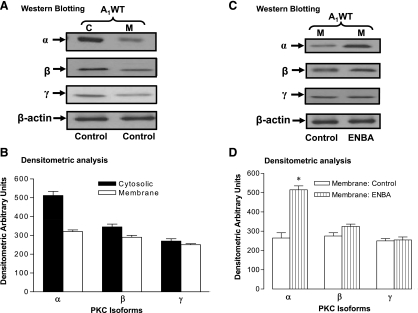

Expression of PKC isoforms in the cytosolic and membrane fractions of A1WT and A1KO mouse CASMCs.

The purpose of this experiment was to determine which PKC isoform predominates in the cytosolic and membrane fractions in A1WT CASMCs (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4A, antibodies directed against PKC-α, -β, and -γ revealed immunoreactive bands in A1WT CASMCs, indicating the presence of these isoforms. The apparent molecular masses of PKC-α, -β, and -γ were ∼82, 80, and 80 kDa, respectively. The densitometric value for the PKC-α-immunoreactive band was 512 ± 22 in the cytosolic fraction, whereas this value was 320 ± 9 in the membrane fraction, of A1WT CASMCs (Fig. 4B). PKC-β and -γ showed moderate levels of expression in the cytosolic and membrane fractions in these cells.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of PKC isoforms (α, β, and γ) in the cytosolic fraction (C) and membrane fraction (M) with and without ENBA treatment of A1WT CASMCs. A and C: Western blots analysis. B and D: densitometric analysis. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 4–5. *P < 0.05 compared with the respective membrane fractions.

A1WT CASMCs were starved overnight in serum-free medium and then treated with the A1AR agonist ENBA (10−5 M) for 100 min followed by isolation of the membrane fraction. In A1WT CASMCs, western blot analysis showed that ENBA treatment increased PKC-α expression in the membrane fraction by 94% compared with its respective untreated control (Fig. 4, C and D). The addition of ENBA did not show any significant distribution change in PKC-β and -γ in A1WT CASMCs (Fig. 4, C and D). These data suggest that PKC-α is the major isoform that predominantly translocates from the cytosolic to membrane fraction with ENBA treatment in A1WT CASMCs.

Antibodies against PKC-α, -β, and -γ revealed immunoreactive bands in A1KO CASMCs, indicating the presence of these isoforms. The cytosolic and membrane fractions from A1KO CASMCs showed the presence of PKC isoforms, with the PKC α-isoform predominating in the cytosolic fraction. The value for PKC-α was 495 ± 20 in the cytosolic fraction, whereas this value was 286 ± 12 in the membrane fraction, of A1KO CASMCs. PKC-β and -γ showed moderate levels of expressions in the cytosolic and membrane fractions of A1KO CASMCs (data not shown).

A1KO CASMCs were treated with ENBA (10−5 M) for 100 min followed by isolation of the membrane fraction. In A1KO CASMCs, Western blot analysis showed that ENBA treatment did not translocate the PKC α-isoform from the cytosolic to membrane fraction in these cells. In the membrane fraction, the addition of ENBA did not show any significant change in PKC-β and -γ distributions in A1KO CASMCs (data not shown). These data suggest that PKC-α is the major isoform predominating in the cytosolic fraction (untreated control) of both A1WT and A1KO CASMCs, but ENBA treatment causes the translocation of PKC-α to the membrane only in A1WT CASMCs.

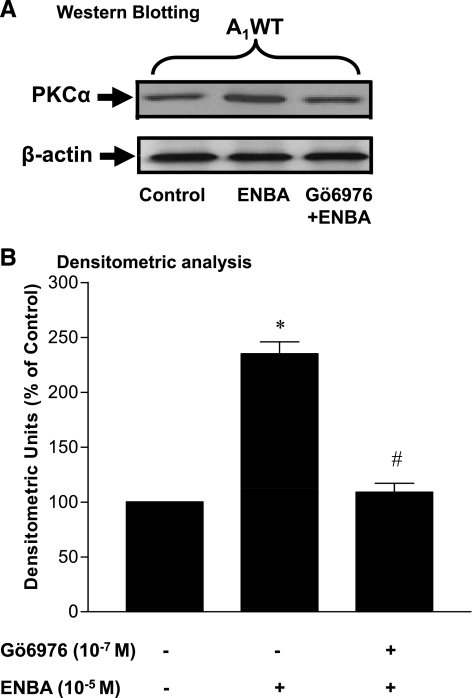

Effect of Gö-6976 on ENBA-induced PKC-α expression in A1WT and A1KO mouse CASMCs.

The purpose of this experiment was to determine whether ENBA treatment activated PKC-α expression and if this activation was inhibited by the specific PKC-α inhibitor Gö-6976. As shown in Fig. 5, ENBA (10−5M) increased PKC-α expression (82 kDa) significantly by 140% in A1WT CASMCs compared with the untreated control. Densitometric analysis showed that the ENBA-induced increase in PKC-α expression was reduced to 25% over the untreated control in the presence of Gö-6976 (Fig. 5). In the presence and absence of Gö-6976, ENBA did not show any effect on PKC-α expression compared with the control in A1KO CASMCs (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Gö-6976 (PKC-α inhibitor) on ENBA-induced PKC-α expression by Western blot analysis in A1WT CASMCs. A: Western blot analysis. B: densitometric analysis. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with the untreated control in A1WT CASMCs; #P < 0.05 compared with ENBA alone in A1WT CASMCs.

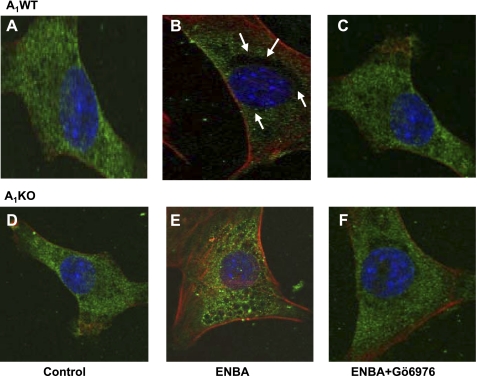

Effect of Gö-6976 on ENBA-induced immunofluorescence of PKC-α in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs.

The activation of PKC is associated with the translocation of PKC isoforms from the cytosolic fraction to the cell membrane (12, 33). To investigate the possible involvement of ENBA-induced PKC-α translocation, immunofluorescence labeling using PKC-α-specific monoclonal antibody was used in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs (Fig. 6). PKC-α immunoreactivity was found in both A1WT and A1KO CASMCs using PKC-α antibody (Fig. 6, A and D). Cells without PKC-α antibody did not show any immunofluorescence (data not shown). PKC-α immunoreactivity appeared to translocate toward the membrane after 100 min of treatment with ENBA in A1WT (Fig. 6B) but not A1KO (Fig. 6E) CASMCs. In A1WT cells, pretreatment with Gö-6976 led to a reversal of ENBA-induced translocation of PKC-α toward the membrane as PKC-α immunoreactivity was spread throughout the cell (Fig. 6C), whereas Gö-6976 had no effect on A1KO CASMCs (Fig. 6, E and F). These results demonstrate that the A1AR agonist ENBA led to a rapid translocation of PKC-α from the cytosol to the membrane in A1WT CASMCs.

Fig. 6.

PKC-α immunoreactivity in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs. A and D: representative immunofluorescence photomicrographs of control cells showing PKC-α with green staining in A1WT (A) and A1KO (D) CASMCs. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). The green color around the nucleus shows PKC-α immunoreactivity. Arrows show the translocation of PKC-α in A1WT CASMCs toward the membrane after ENBA treatment (black empty area around the nucleus; B). ENBA-induced translocation toward the membrane was blocked by the PKC-α inhibitor Gö-6976 (C). Membrane translocation was not seen after ENBA treatment in A1KO CASMCs (E and F).

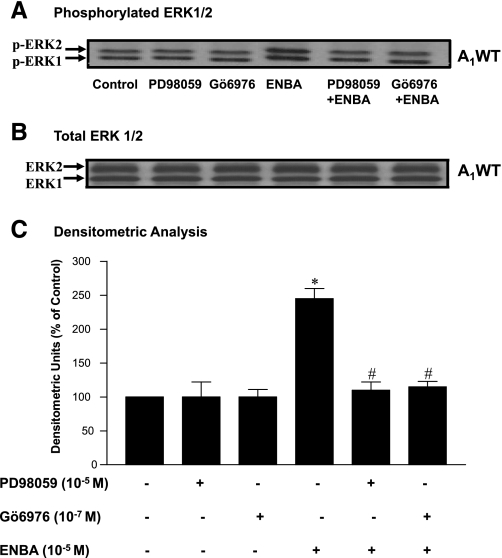

Effects of PD-98059 and Gö-6976 on ENBA-induced p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs.

As shown in Fig. 7, treatment of A1WT CASMCs with ENBA for 10 min increased p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2, 42/44 kDa) phosphorylation by 145% over the control, and this increase was significantly abolished in the presence of the MAPK inhibitor PD-98059 and the PKC inhibitor Gö-6976. In A1KO CASMCs, PD-98059 and Gö-6976 had no effect on p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation with ENBA (data not shown). These data suggest that PKC is an upstream regulator of p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) in A1WT CASMCs.

Fig. 7.

Effect of PD-98059 (MAPK inhibitor) and Gö-6976 (PKC-α inhibitor) on ENBA-induced p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation in A1WT CASMCs. A: phosphorylated p42/p44 MAPK (p-ERK1/2). B: total ERK. C: densitometric analysis of p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with controls (untreated); #P < 0.05 compared with ENBA alone.

DISCUSSION

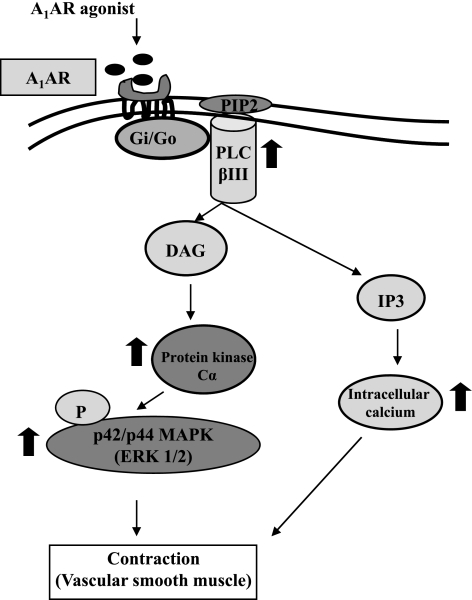

There is evidence from our laboratory and others that A1AR is involved in the regulation of vascular tone, including that in the coronary artery, through the inhibition of Gi/Go protein (13, 15, 29, 30, 32, 34). In the present study, we extended these findings to determine whether A1AR-mediated contraction is via PKC and p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) pathways in CASMCs using A1WT and A1KO mice. We also compared the distribution of different PKC isoforms in the cytosolic and membrane fractions in control and ENBA (A1AR agonist)-treated CASMCs from A1WT and A1KO mice. The distribution of PKC isoforms revealed domination of PKC-α in the cytosolic fraction in A1WT cells (Fig. 4). However, after treatment with ENBA, PKC-α translocated to the membrane in A1WT CASMCs (Fig. 4) but not in A1KO CASMCs. The major findings of the present study are as follows: 1) ENBA treatment in A1WT cells increased A1AR, PLC-βIII, and PKC-α expressions and p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation; 2) pretreatment with Gö-6976 and PD-98059 resulted in the inhibition of ENBA-induced PKC-α expression and p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation, respectively; and 3) pretreatment with Gö-6976 and PD-98059 inhibited the ENBA-induced contraction of mesenteric arteries in A1WT mice. These finding suggest that the activation of A1ARs leads to the following signaling pathways: A1AR → PLC-βIII → PKC-α → p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation → contraction (see the schematic presentation in Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Putative signaling mechanism for A1AR-mediated contraction in vascular smooth muscle. The activation of the A1AR originates from the binding of an extracellular ligand (A1AR agonist) and is followed by the activation of a G protein on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane. The G protein, using GTP as an energy source, then activates PLC-βIII, leading to the activation of PKC-α via diacylglycerol (DAG). PKC-α then phosphorylates p42/p44 MAPK, leading to the contraction of smooth muscle. On the other hand, inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3) also causes the contraction of smooth muscle through an increase in intracellular calcium. PIP2: phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate.

The A1AR coupled to Gi/o protein is known to regulate signaling pathways in various tissues, including the modulation of PLC activity, inhibition of PLA2 and adenylate cyclase, activation of K+ channels, and inhibition of Ca2+ channels (5, 17, 27, 34). To examine which PLC isoform mediates the activation of PKC and downstream signaling leading to contraction, various PLC isoforms were examined in CASMCs. In the present study, Western blot analysis demonstrated that PLC-βIII was predominantly activated by ENBA in A1WT CASMCs, whereas PLC-βI and PLC-γ1 were unchanged in A1WT and A1KO CASMCs compared with their respective controls. Our data showed that A1AR activation after treatment with ENBA leads to an upregulation of PLC-βIII expression in A1WT (Fig. 3) but not A1KO CASMCs. In a separate experiment, pretreatment of A1WT CASMCs with U-73122 (PLC inhibitor) completely abolished the ENBA-induced increase in PLC-βIII expression (data not shown). Similar findings have been reported by Shim et al. (27), showing that the A1AR is coupled to Gi protein, leading to activation of the phosphotidylinositol → PLC-βIII pathway.

The present study also evaluated the involvement of conventional or Ca2+-dependent PKC isoforms (α, β, and γ) in A1AR-mediated signaling in CASMCs. PKC-α was the most predominant PKC isoform affected by ENBA treatment in A1WT CASMCs. Therefore, it is likely that the PKC α-isoform may directly play a role in the A1AR-mediated contraction of vascular tissue and the decrease in coronary flow in A1WT as opposed to A1KO mice (29, 30). PKC-α signaling was further confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy experiments using a specific PKC-α antibody. PKC-α immunoreactivity appeared to translocate toward the membrane after A1AR activation in A1WT CASMCs (Fig. 6B), which was also confirmed by immnunoblot analysis (Fig. 4). These data support the possibility of a PLC-βIII-PKC-α signaling pathway due to A1AR activation.

To further confirm the involvement of PKC-α in A1AR-mediated (ENBA) mesenteric artery contraction, a specific PKC-α inhibitor (Gö-6976) was used. Gö-6976 has been used in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells as a PKC-α inhibitor previously (4, 22). Our functional experiments with mesenteric arteries from A1WT mice using a wire myograph showed that ENBA treatment led to an increase in concentration-dependent contraction, which was inhibited by treatment with the PKC-α inhibitor Gö-7976. These results indicate that PKC-α is involved in A1AR-mediated contraction in A1WT mesenteric arteries, whereas A1KO mesenteric arteries did not show any response with ENBA. These findings are supported by Fomin et al. (6), who demonstrated the involvement of PKC-α in the regulation of human uterine contraction.

Our functional experiments were conducted in mesenteric arteries isolated from the mouse, whereas all other data were generated using CASMCs. This was due to the fact that the isolation and functionality of organ bath experiments with coronary arteries from the mouse are very challenging and technically difficult. Therefore, we carried our functional experiments in mesenteric arteries (resistance vessel), which can be isolated relatively easily without a loss of functionality. Moreover, the functionality of the endothelium is also compromised during isolation of the mouse coronary artery. This could be considered a limitation of this study.

Most of the studies on AR signaling in vascular smooth muscle have been limited to the cAMP/PKA pathway, which is either regulated by the activation (A2AAR and A2BAR) or inhibition (A1AR and A3AR) of adenylate cyclase via G proteins. However, ARs are also coupled to other distinct signaling pathways through G proteins, which include MAPKs. ERK is a member of the MAPK family that regulates cell growth, differentiation, motility, and apoptosis through the stimulation of diverse classes of receptors, such as receptor tyrosine kinases and G protein-coupled receptors (16, 21). Each AR subtype has been shown to activate ERK1/2 (24), which may be PKC/Ras dependent or independent, but no study so far has examined its role in A1AR-mediated vascular contraction. In the present study, we have shown that ENBA treatment of A1WT CASMCs produced a significant increase in p42/p44 MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation, suggesting the involvement of ERK1/2 signaling in response to A1AR activation. The involvement of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway through A1AR activation was supported by the use of PD-98059, which selectively blocks the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK (1). The MAPK inhibitor PD-98059 also significantly inhibited ENBA-induced contraction in mesenteric arteries of A1WT mice (data not shown). Again, these results are consistent with our hypothesis that the A1AR induces downstream signaling via the MAPK pathway leading to aortic contraction or a decrease in coronary flow (29, 30). In addition, the A1AR has been shown to activate p42/44 MAPK (ERK 1/2) signaling in human- and animal-derived cell lines in previous studies (8, 20, 25, 26).

The fact that ENBA leads to an increase in both PKC-α expression and p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation suggests a link between these two signaling pathways. This link was supported by Western blot experiments (Fig. 7) that showed that the PKC-α inhibitor (Gö-6976) blocked the ENBA-induced increase in the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK. This suggests that PKC-α is an upstream regulator of p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in the A1AR-mediated contraction of vascular tissue (Fig. 8).

In summary, the present study demonstrated that A1AR activation by ENBA activates PKC-α, leading to p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in CASMCs as well as contraction of vascular smooth muscle. The present study suggests that pharmacological modulation of the A1AR in CASMCs may present opportunities for the treatment of cardiovascular disorders and could be therapeutically targeted.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-027339 and HL-094447.

Acknowledgments

Image acquisition was performed in part through the use of the West Virginia University Microscope Imaging Facility at the Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center of West Virginia University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansari HR, Husain S, Abdel-Latif AA. Activation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and contraction by prostaglandin F2alpha, ionomycin, and thapsigargin in cat iris sphincter smooth muscle: inhibition by PD98059, KN-93, and isoproterenol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299: 178–186, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari HR, Nadeem A, Tilley SL, Mustafa SJ. Involvement of COX-1 in A3 adenosine receptor-mediated contraction through endothelium in mice aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3448–H3455, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding Y, Schwartz D, Posner P, Zhong J. Hypotonic swelling stimulates L-type Ca2+ channel activity in vascular smooth muscle cells through PKC. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C413–C421, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology: XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 53: 527–552, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fomin VP, Kronbergs A, Gunst S, Tang D, Simirskii V, Hoffman M, Duncan RL. Role of protein kinase C alpha in regulation of [Ca2+]i and force in human myometrium. Reprod Sci 16: 71–79, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain T, Mustafa SJ. Effects of adenosine analogues on ADP ribosylation of Gs protein in coronary artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H875–H879, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HT, Emala CW. Characterization of adenosine receptors in human kidney proximal tubule (HK-2) cells. Exp Nephrol 10: 383–392, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marala RB, Mustafa SJ. Direct evidence for the coupling of A2-adenosine receptor to Gs protein in bovine brain striatum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 266: 294–300, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marala RB, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine A1 receptor-induced up-regulationof protein kinase C: role of pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein(s). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1619–H1624, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marala RB, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine analogues prevent phorbol ester-induced PKC depletion in porcine coronary artery via A1 receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H271–H277, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martelli AM, Sang N, Borgatti P, Capitani S, Neri LM. Multiple biological responses activated by nuclear protein kinase C. J Cell Biochem 74: 499–521, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matherne GP, Linden J, Byford AM, Gauthier NS, Headrick JP. Transgenic A1 adenosine receptor overexpression increases myocardial resistance to ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6541–6546, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulvany MJ, Nyborg N. An increased calcium sensitivity of mesenteric resistance vessels in young and adult spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol 71: 585–596, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-beta 3 in intestinal muscle: dual requirement for alpha and beta gamma subunits of Gi3. Mol Pharmacol 47: 1172–1179, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers-Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev 22: 153–183, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50: 413–492, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebecchi MJ, Pentyala SN. Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol Rev 80: 1291–1335, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee SG. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu Rev Biochem 70: 281–312, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson AJ, Dickenson JM. Regulation of p42/p44 MAPK and p38 MAPK by the adenosine A1 receptor in DDT1MF-2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 413: 151–161, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roux PP, Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 320–344, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakwe AM, Rask L, Gylfe E. Protein kinase C modulates agonist-sensitive release of Ca2+ from internal stores in HEK293 cells overexpressing the calcium sensing receptor. J Biol Chem 280: 4436–4441, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salamanca DA, Khalil RA. Protein kinase C isoforms as specific targets for modulation of vascular smooth muscle function in hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol 70: 1537–1547, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulte G, Fredholm BB. Signalling from adenosine receptors to mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cell Signal 15: 813–827, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shearer TW, Crosson CE. Adenosine A1 receptor modulation of MMP-2 secretion by trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 3016–3020, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen J, Halenda SP, Sturek M, Wilden PA. Cell-signaling evidence for adenosine stimulation of coronary smooth muscle proliferation via the A1 adenosine receptor. Circ Res 97: 574–582, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim JO, Shin CY, Lee TS, Yang SJ, An JY, Song HJ, Kim TH, Huh IH, Sohn UD. Signal transduction mechanism via adenosine A1 receptor in the cat esophageal smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal 14: 365–372, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, Huang Y, Paliege A, Saunders T, Briggs J, Schner. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9983–9988, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tawfik HE, Schnermann J, Oldenburg PJ, Mustafa SJ. Role of A1 adenosine receptors in regulation of vascular tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1411–H1416, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tawfik HE, Teng B, Morrison RR, Schnermann J, Mustafa SJ. Role of A1 adenosine receptor in the regulation of coronary flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H467–H472, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng B, Ansari HR, Oldenburg PJ, Schnermann J, Mustafa SJ. Isolation and characterization of coronary endothelial and smooth muscle cells from A1 adenosine receptor-knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1713–H1720, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thong FS, Lally JS, Dyck DJ, Greer F, Bonen A, Graham TE. Activation of the A1 adenosine receptor increases insulin-stimulated glucose transport in isolated rat soleus muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 32: 701–710, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toker A. Signaling through protein kinase C. Front Biosci 3: D1134–D1147, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang SJ, An JY, Shim JO, Park CH, Huh IH, Sohn UD. The mechanism of contraction by 2-chloroadenosine in cat detrusor muscle cells. J Urol 163: 652–658, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]