Abstract

Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and is commonly caused by hypertension. In rodents, transverse aortic constriction (TAC) is a model regularly employed in mechanistic studies of the response of the LV to pressure overload. We previously reported that inbred strains of male mice manifest different cardiac responses to TAC, with C57BL/6J (B6) developing LV dilatation and impaired contractility and 129S1/SvImJ (129) males displaying concentric LVH. In the present study, we investigated sex and parent-of-origin effects on the response to TAC by comparing cardiac function, organ weights, expression of cardiac hypertrophy markers, and histology in female B6 and female 129 mice and in F1 progeny of reciprocal crosses between B6 and 129 mice (B6129F1 and 129B6F1). Five weeks after TAC, heart weight increased to the greatest extent in 129B6F1 mice and the least extent in 129 and B6129F1 mice. Female 129B6F1 and B6 mice were relatively protected from the increase in heart weight that occurs in their male counterparts with pressure overload. The response to TAC in 129 consomic mice bearing the B6 Y chromosome resembled that of 129 rather than 129B6F1 mice, indicating that the B6 Y chromosome does not account for the differences in the reciprocal cross. Our results suggest that susceptibility to LVH is more complex than simple Mendelian inheritance and that parental origin effects strongly impact the LV response to TAC in these commonly used inbred strains.

Keywords: left ventricular hypertrophy, imprinting, cardiac fibrosis, transaortic constriction

the presence of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) is associated with increased mortality from cardiovascular disease. Although a strong determinant for the development of LVH is blood pressure (4), interactions between multiple genes and the environment likely contribute to the development of LVH. For example, age, sex, race, and stimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system all contribute to the development of LVH (20). Histologically, LVH is characterized by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, perivascular and interstitial fibrosis, and medial thickening of intramyocardial coronary arteries. LVH, in turn, is an independent predictor of the development of heart failure. In a recent study, every 1% increase in excess LV mass was associated with a 1% increase in heart failure (5). Consequently, an important goal in the field is to characterize the genetic susceptibility determinants of LVH and the subsequent development of LV systolic dysfunction in the setting of hypertension.

In mice, LV pressure overload generated by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) causes progressive LVH with histological features similar to those observed in human hypertrophic hearts. Male C57BL/6J (B6) mice develop LV systolic dysfunction within 5 wk of TAC. We previously reported (3) that male 129S1/SvImJ (129) mice exhibited concentric LVH with preserved systolic function 5 wk after TAC. Because B6129F1 mice were protected from early systolic dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis, similar to parental 129 mice, we postulated the presence of dominant modifiers on the 129 background that protected against the more severe pathological changes after TAC. In the present study, we report on the influence of sex and parent-of-origin effects on the response to TAC indicating that epigenetic regulation also contributes to differential susceptibility to LVH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All procedures conformed to the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Dept. of Health and Human Services Pub. No. NIH 78-23, 1996) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of North Carolina and the University of Kentucky. Mice [129, B6, and 129S1/SvImJ-Chr YC57BL/6J/NaJ(8) (129YB6)] were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Crosses between female B6 and male 129 mice and between female 129 and male B6 mice were set up to produce reciprocal B6129F1 and 129B6F1 offspring, respectively. Pups were weaned at 21 days, maintained on a 14-h light, 10-h dark cycle, and fed water and standard rodent chow (2018 Harlan Tekland Roden Diet) ad libitum.

Aortic banding.

Pressure overload of the LV was induced by thoracic aortic banding (TAC) in mice aged 8–12 wk. The aorta was ligated between the innominate and left common carotid arteries by tying a 7-0 silk suture around a tapered 27-gauge needle placed on top of the aorta. The tapered needle was removed, leaving the suture to produce a defined constriction of the vessel. The skin was closed with separate sutures (6-0 silk), and buprenorphine was administered for analgesia. Velocity of blood flow in the left and right carotid arteries was measured before and after ligation with a hand-held 20-mHz Doppler probe (Indus Instruments). Previous work indicates that the change in carotid velocity is proportional to the degree of development of LVH (13). All groups of mice had similar changes in left and right carotid velocities after TAC. Three to five mice of each genetic background underwent a sham operation in which the aortic arch was isolated and a suture was placed around the aorta, but not ligated, and subsequently removed. These mice displayed no change in left and right carotid velocities after TAC.

Echocardiography.

Two-dimensional short- and long-axis views of the LV were obtained by transthoracic echocardiography performed 5 wk after TAC with a 30-MHz probe and the Vevo 770 Imaging System (VisualSonics) as previously described (3). M-mode tracings were recorded and used to determine LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD), and LV posterior wall thickness in diastole (LVPWThD) over three cardiac cycles. LV fractional shortening (FS) was calculated with the formula %FS = (LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD.

Histology.

Mice were weighed and hearts, lungs, livers, and kidneys were dissected 5 wk after TAC or sham surgery. Hearts were cut in cross section just below the level of the papillary muscle. The base of the heart was formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were prepared at 200-μm intervals. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Sections were stained with Masson's trichrome (MT) or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and counterstained with hematoxylin (PAS-H) to measure fibrosis and cardiomyocyte size, respectively. Cardiomyocyte size was assessed by measuring cross-sectional area of 100 cardiomyocytes per PAS-H-stained section in 10 randomly selected fields having nearly circular capillary profiles and centered nuclei in the LV free wall. Cardiac fibrosis was determined by calculating the percentage of MT-stained area of interstitial fibrosis per total area of cardiac tissue in six random fields of view per section. Four random sections were analyzed and averaged per heart.

Gene expression.

Total RNA was extracted from the lower half of the LV with TRIzol (Invitrogen). After DNase treatment, 500 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems). The expression of α-myosin heavy chain (Myh6), β-myosin heavy chain (Myh7), atrial natriuretic peptide (Nppa), brain natriuretic peptide (Nppb), and medium-chain acyl dehydrogenase (Acadm) was determined by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) using Taqman Universal Master Mix and Assays-on Demand primers and probes (Applied Biosystems). Primers for 18S ribosomal RNA were used as an internal control. Results are represented as mean fold changes in expression relative to sham-operated LV expression, as indicated.

Statistical analysis.

All results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance within strains was determined by t-test or ANOVA with multiple pairwise comparisons as appropriate. The Mann-Whitney test was used for nonparametric analysis. Statistical analysis was performed with Sigma-STAT software, version 3.5 (Systat Software). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

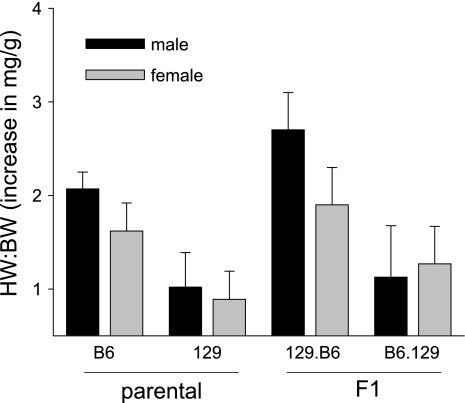

We previously investigated (3) strain-specific differences in the cardiac response to LV pressure overload caused by surgical TAC in male mice. We reported (3) that B6 male mice had an earlier onset and more pronounced impairment in contractile function than 129 and B6129F1 mice, which had preserved systolic function and relatively mild alterations in histology and markers of hypertrophy at 5 wk after TAC, suggesting a dominant protective effect of a 129 modifier(s). In the present study, we expanded our findings by comparing the development of LVH and LV dysfunction in response to TAC in B6 and 129 female mice and in F1 reciprocal cross (B6129F1 and 129B6F1) mice. In general, the increase in heart weight (HW):body weight (BW) after TAC in female mice paralleled the increases observed in male mice, although female mice on the B6 and 129B6F1 backgrounds were protected from LVH in that they displayed smaller increases in HW:BW than their male counterparts (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2). Surprisingly in light of our previous findings that 129 and B6129F1 mice had only modest increases in HW:BW at 5 wk after TAC, in this study we observed an increase in HW:BW in 129B6F1 mice after TAC that was at least similar to, if not greater than, the response we observed in B6 mice after TAC (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2). Lung weight (LuW):BW increased to the greatest extent in 129.B6 and B6 mice, suggesting more pronounced pulmonary congestion.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of increase in heart weight (HW):body weight (BW) in male and female C57BL/6J (B6), 129S1/SvImJ (129), and F1 mice. Data are presented as the increase in HW:BW (means ± SD) relative to age-, sex- and genotype-matched sham controls.

Table 1.

Organ and body weight in male mice 5 wk after TAC or sham surgery

| n | BW | HW:BW | LiW:BW | LuW:BW | KiW:BW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 TAC | 17 | 26.2±3.6 | 7.9±1.8*† | 50.0±5.3 | 6.3±0.9 | 13.8±1.5 |

| B6 Sham | 9 | 27.2±3.0 | 5.8±0.9 | 48.2±1.9 | 6.0±0.6 | 13.7±1.1 |

| 129 TAC | 11 | 27.2±3.0 | 6.3±0.9 | 38.9±3.4 | 6.0±0.6 | 15.7±0.7 |

| 129 Sham | 7 | 26.5±1.5 | 5.3±0.6 | 37.8±3.0 | 5.5±0.5 | 15.7±0.7 |

| 129B6F1 TAC | 7 | 31.2±1.8 | 7.5±1.1* | 48.6±7.6 | 6.3±0.5 | 14.3±1.3 |

| 129B6F1 Sham | 5 | 33±2.0 | 4.8±0.4 | 46.0±3.2 | 5.3±0.4 | 15.0±1.7 |

| B6129F1 TAC | 14 | 30.3±5.5 | 6.2±0.9 | 44.4±4.8 | 5.3±0.7 | 14.7±2.8 |

| B6129F1 Sham | 6 | 34.4±7.6 | 5.1±1.2 | 39.8±3.9 | 5.1±1.1 | 11.7±1.6 |

Results are means ± SD for n mice. TAC, transverse aortic constriction; Sham, sham surgery; B6, C57BL/6J; 129, 129S1/SvImJ; B6129F1, B6 × 129 F1 cross; HW, heart weight; BW, body weight; LiW, liver weight; LuW, lung weight; KiW, kidney weight.

Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) by pairwise comparison with B6.129;

statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) by pairwise comparison with 129.

Table 2.

Organ and body weight in female mice 5 wk after TAC or sham surgery

| n | BW | HW:BW | LiW:BW | LuW:BW | KiW:BW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 TAC | 8 | 20.8±1.2 | 6.5±0.9 | 50.6±2.6 | 6.8±0.3 | 13±0.8 |

| B6 Sham | 5 | 22.2±1.6 | 4.9±0.1 | 49.5±1.1 | 6.9±0.6 | 13±1.0 |

| 129 TAC | 10 | 22.5±1.3 | 5.6±0.9 | 38.5±1.9 | 6.7±0.8 | 12.9±0.8 |

| 129 Sham | 7 | 21.1±0.9 | 4.7±0.2 | 38.1±4.1 | 6.6±0.5 | 13.2±1.0 |

| 129B6 F1 TAC | 11 | 26.9±2.1 | 6.7±1.3 | 42.7±4.1 | 6.3±1.0 | 12.1±1.0 |

| 129B6F1 Sham | 7 | 27.0±2.0 | 4.9±0.5 | 41.1±4.5 | 5.9±0.8 | 12.1±0.3 |

| B6129F1 TAC | 9 | 27.8±2.7 | 6.1±0.8 | 45.4±8.7 | 6.3±0.6 | 13.0±3.0 |

| B6129F1 Sham | 5 | 28.3±2.4 | 4.9±0.7 | 44.0±4.1 | 5.7±0.2 | 11.9±1.5 |

Results are means ± SD for n mice.

Sex influence on genetic modifiers of LVH.

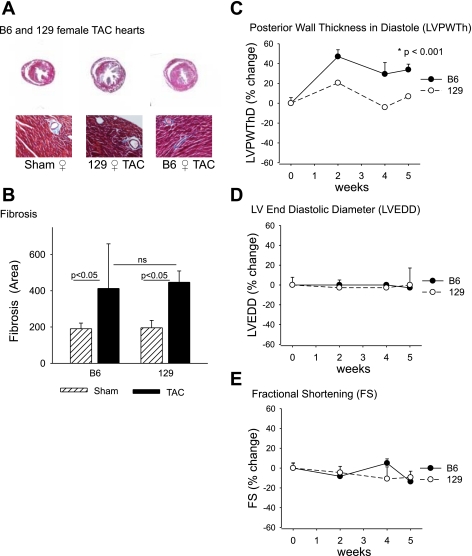

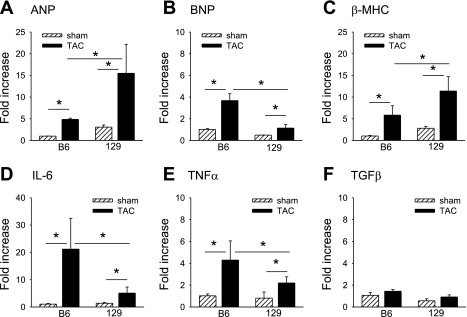

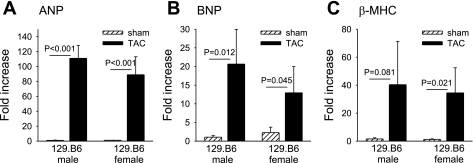

We examined in more detail the influence of female sex on the development of LVH after TAC in mice of different genetic backgrounds. Pressure overload increased HW:BW in female B6 mice (n = 8) by 136 ± 18% (P = 0.002) and in female 129 mice (n = 10) by 119 ± 20% (P = 0.03) relative to strain-appropriate sham-operated mice. No significant differences in LuW:BW or liver weight (Li):BW were noted in either B6 female or 129 female mice compared with strain-appropriate sham-operated animals (Table 2). Characteristic histological evidence for perivascular and interstitial fibrosis was observed after TAC (Fig. 2, A and B). Additionally, changes in LV size and function after TAC were monitored by echocardiography (Fig. 2, C–E). In B6 female mice, LVPWThD increased after TAC (P < 0.001), consistent with the increase in HW:BW. However, unlike the decline in LV function observed in B6 male mice (3), FS was preserved in B6 female mice at 5 wk after TAC (Fig. 2E). We previously reported that the LV response to TAC in B6 male mice involves extensive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis whereas 129 male mice have much milder alterations in LV histology after TAC. In contrast, the extent of interstitial and perivascular fibrosis was similar in B6 and 129 females after TAC (Fig. 2B). Pressure overload activates a fetal gene regulatory program with reexpression of “hypertrophy” genes including atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC), and β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) genes. Interestingly, 129 female mice after TAC had higher expression of the hypertrophy markers ANP (Fig. 3A) and β-MHC (Fig. 3C) as assayed by qPCR. ANP gene expression increased 15.4-fold in 129 females and 4.8-fold in B6 females (Fig. 3A; P < 0.05 by ANOVA), and β-MHC gene expression increased 11.4-fold in 129 females and 5.8-fold in B6 females (Fig. 3C; P < 0.05 by ANOVA). In contrast, B6 females had higher expression of inflammatory genes for IL-6 (21-fold increase in B6 females vs. 5-fold increase in 129 females relative to sham surgery, P < 0.05 by ANOVA; Fig. 3D) and TNF-α (4.2-fold vs. 2.2-fold increase relative to sham surgery, P < 0.05 by ANOVA; Fig. 3E).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the responses to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) in B6 and 129 female mice. A: representative Masson's trichrome staining of cardiac sections from B6 and 129 sham-operated or TAC hearts 5 wk after surgery [magnification ×1.6 (top), ×20 (bottom)]. B: quantitation of interstitial and perivascular fibrosis (% interstitial fibrosis) presented as means ± SD; ns, not significant. Echocardiography was used to measure increases in left ventricular (LV) posterior wall thickness in diastole (LVPWThD, C), LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD, D), and fractional shortening (FS, E). Results are presented as % change (means ± SD) from baseline for B6 (n = 8) and 129 (n = 6) female mice.

Fig. 3.

Changes in expression of genes involved in inflammation and hypertrophy in B6 and 129 female mice. The hypertrophy markers atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP, A), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP, B), and β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC, C) were measured 5 wk after TAC (n = 3–5 mice/group). IL-6 (D), TNF-α (E), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β, F) were measured 1 wk after TAC. Results are expressed as fold change (means ± SE) relative to B6 sham-operated values. *P < 0.05.

Parental influence on genetic modifiers of LVH.

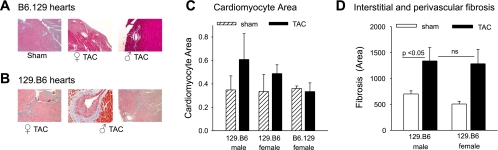

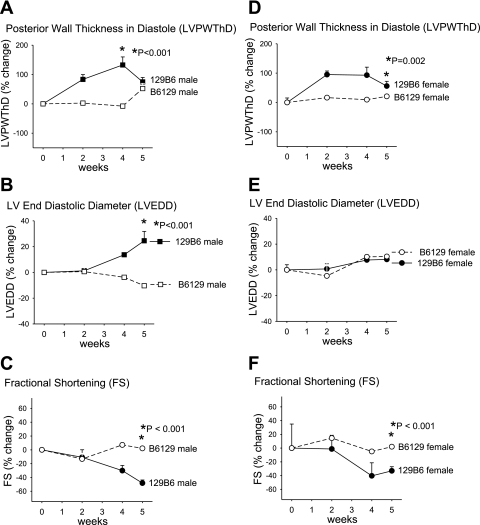

Next, we examined further the parent-of-origin effect on the development of LVH and systolic LV dysfunction. The reciprocal crosses between 129 and B6 mice produces F1 offspring (129B6F1 and B6129F1) with the same complement of autosomal alleles but inherited from opposite parents, as are the sex chromosomes. The difference in HW:BW in 129B6F1 and B6129F1 mice after TAC (Fig. 1 and Table 1) suggests that modifiers for the development of LVH may be subject to a parent-of-origin effect. Histologically, the response to TAC in the 129B6F1 mice was strikingly different (Fig. 4), with dramatic development of intimal hyperplasia observed in 129B6F1 but not B6129F1 coronary arteries (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the HW:BW measurements, the largest increase in cardiomyocyte size occurred in 129B6F1 male mice (Fig. 4C). Extensive perivascular and interstitial fibrosis was also observed in 129B6F1 mice (Fig. 4D). Echocardiographic analysis also demonstrated 136 ± 27% and 93 ± 27% increase in LVPWThD (Fig. 5, A and D) and 24 ± 7% and 8 ± 2% increase in LVEDD (Fig. 5, B and E) at 4–5 wk after TAC in 129B6F1 male and female mice, respectively. LV systolic function as assessed by FS declined by ∼35% in both 129B6F1 male and female mice but was preserved in B6129F1 animals (Fig. 5, C and F). These changes were accompanied by increases in gene expression for ANP (Fig. 6A), BNP (Fig. 6B), and β-MHC (Fig. 6C) after TAC in 129B6F1 mice.

Fig. 4.

Response to LV pressure overload in F1 offspring of B6 and 129 reciprocal crosses. A: representative Masson's trichrome staining of cardiac sections (magnification ×20) from B6.129 sham-operated and TAC hearts (A) and 129.B6 F1 sham-operated and TAC hearts (B) 5 wk after surgery. Collagen fibers are stained blue. C: cardiomyocyte area in F1 mice after TAC was measured in periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections and is reported as means ± SD. D: quantitation of interstitial and perivascular fibrosis (% interstitial fibrosis) presented as means ± SD.

Fig. 5.

Response to LV pressure overload in F1 offspring of B6 and 129 reciprocal crosses. LVPWThD (A), LVEDD (B), and FS (C) in males and LVPWThD (D), LVEDD (E), and FS (F) in females are presented as % change (means ± SD) from baseline.

Fig. 6.

Expression of hypertrophy genes in sham-operated and TAC 129B6F1 mice. The hypertrophy markers ANP (A), BNP (B), and β-MHC (C) were measured 5 wk after TAC (n = 6 or 7 mice/group). Results are expressed as fold change (means ± SD) relative to 129B6F1 male sham-operated values.

Influence of Y chromosome on genetic modifiers of LVH.

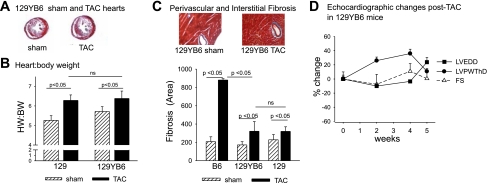

Recently, the parental origin of the Y chromosome was reported to strongly influence the size of cardiomyocytes in the AXB/BXA panel of recombinant inbred mice generated from B6 and A/J (A) mice (15). Since male B6 and 129B6F1 mice were most severely affected, we investigated whether the origin of the Y chromosome influenced the cardiac response, using 129 consomic mice bearing the B6 Y chromosome (8) (129YB6). HW:BW increased to a similar ∼115% extent in 129 and 129YB6 mice (Fig. 7B). Less interstitial and perivascular fibrosis was observed in both 129 and 129YB6 compared with B6 male mice (Fig. 7C). In addition, as we previously reported for 129 male mice, no decline in LV systolic function was observed in 129YB6 mice after TAC by echocardiography (Fig. 7D). 129YB6 mice also did not display the same extent of increase in expression of cardiac hypertrophy genes as observed in B6 mice (P = 0.004 for comparison of fold increase in BNP gene expression in B6 and 129YB6 male mice after TAC and P < 0.001 for comparison of fold increase in β-MHC gene expression in B6 and 129YB6 male mice after TAC). Together, these results indicate that the B6 Y chromosome alone does not confer susceptibility to development of LVH and decline in LV systolic function observed in the offspring of B6 male mice after TAC.

Fig. 7.

Lack of effect of B6 Y chromosome on LV hypertrophy (LVH) after TAC in 129 mice. A: representative Masson's trichrome staining of cardiac sections from 129YB6 sham-operated and TAC hearts 5 wk after surgery (magnification ×1.6). B: HW:BW in 129 and 129YB6 mice after sham operation or TAC. C: representative Masson's trichrome staining of cardiac sections (magnification ×20) and % interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in B6 and 129YB6 mice (mean ± SD). D: echocardiographic changes in LVPWThD, LVEDD, and FS in 129YB6 mice after TAC.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the present work is that offspring (129B6F1 and B6129F1 mice) of the reciprocal crosses between B6 and 129 mice have striking differences in the development of LVH and decline in contractile function following pressure overload of the LV. Because inbred strains of mice are homozygous at all loci, the reciprocal crosses between B6 and 129 mice should produce F1 offspring that have an identical complement of genes on autosomal chromosomes. The dramatic differences following TAC in the 129B6F1 and B6129F1 mice indicate that parent of origin-dependent gene expression strongly influences the increase in LV mass and decline in LV function that is elicited by pressure overload from surgical aortic constriction. Specifically, both male and female offspring of B6 male mice have larger increases in LV mass and greater declines in LV systolic function than offspring of 129 male mice. Increased LV mass, decreased contractility, and eccentric hypertrophy in B6 mice have been reported relative to the A/J inbred strain (9), and subsequent studies using consomic mice demonstrated that transfer of the B6 Y chromosome to the A/J background was sufficient to increase cardiomyocyte size, but not LV mass, relative to A/J mice (15). However, in our studies, examination of consomic 129YB6 mice excluded the B6 Y chromosome as conferring the parent-of-origin susceptibility to LVH and heart failure observed in the offspring of B6 male mice after TAC. The finding that the B6 × 129 cross generates B6129F1 mice with a mild phenotype after TAC similar to that observed in 129 mice excludes a contribution of maternal genome, including the X chromosome and mitochondrial genome, and eliminates an intrauterine influence. The fact that the 129B6F1 mice, produced from 129 × B6 crosses, have a more pronounced phenotype like that of B6 mice suggests that a paternal autosomal factor needs to be inherited for display of early LV systolic dysfunction and development of cardiac fibrosis and neointimal hyperplasia after TAC.

These findings demonstrate a parent-of-origin effect alone or in combination with differences imparted by sex chromosomes and implicate a role for genomic imprinting in the response to pressure overload. Our findings would be consistent with a 129 resistance factor or a B6 susceptibility factor only functional or expressed when inherited from the father.

Consistent with previous reports investigating sex-specific responses to pressure overload in B6 mice (2, 22), we found that B6 females were protected from cardiac fibrosis and systolic dysfunction and had milder cardiac hypertrophy compared with B6 males. Evidence from several groups suggests that cardioprotection to pressure overload in B6 female mice is due to estrogen effects mediated through estrogen receptor 2β (ESR2) (2, 22). Moreover, ESR2 stimulation appears to be cardioprotective in other rodent models of cardiac stress, including ischemia-reperfusion injury (18) and myocardial infarction (19). Our results suggest that the protective effect of estrogen is blunted on the 129 background, where HWs in males and females were similar after TAC. Genetic background-dependent differences in the expression and protein levels of ESR2 have been observed in young female B6 mice and C3H/HeJ mice, with B6 mice having nearly 20-fold higher expression of ESR2 in the aorta and aortic smooth muscle cells and a higher transcriptional response to 17β-estradiol (E2) (21). Therefore, it is possible that higher expression levels of ESR2 exist in B6 female mice compared with 129 female mice, and that this elevated expression may explain relatively greater cardioprotection compared with males on this pressure overload-susceptible genetic background.

Additionally, a correlation between LV systolic decline and the development of extensive cardiac fibrosis and intimal hyperplasia was observed. 129B6F1 mice that have the greatest development of LVH, as assessed by HW:BW and LVPWThD, and early LV systolic dysfunction also have the most extensive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis and display neointima in the coronary vessels at 5 wk after TAC. Female mice are protected from the decline in LV function after TAC and also have less cardiac fibrosis. In unpublished work, we have observed that perivascular inflammation precedes the decline in systolic function in this model; however, whether the development of intimal hyperplasia and cardiac fibrosis causes or simply parallels the decline in LV function remains to be determined.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that susceptibility to LVH is more complex than simple Mendelian inheritance. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of parent-of-origin effects on the development of LVH and LV dysfunction in response to pressure overload. Given the common use of B6 and 129S1 strains to generate genetically engineered mice, studies to assess cardiac response to TAC using mixed B6 and 129 genetic background mice, and potentially even studies of mice after backcrossing, need to take into account the parental origin in addition to genetic variation. Finally, the finding of epigenetic regulation of the development of LVH and LV dysfunction has important implications for ongoing genomewide association studies, which do not detect epigenetic variation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-074219, HL-078663, and HL-080166 to S. S. Smyth and ES-010126 and CA-105417 to D. W. Threadgill.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation for the excellent technical assistance provided by Jessica Caicedo, Alyssa Moore, and Mynu Kappen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi S, Ito H, Akimoto H, Tanaka M, Fujisaki H, Marumo F, Hiroe M. Insulin-like growth factor-II induces hypertrophy with increased expression of muscle specific genes in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 789–795, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babiker FA, Lips D, Meyer R, Delvaux E, Zandberg P, Janssen B, van EG, Grohe C, Doevendans PA. Estrogen receptor beta protects the murine heart against left ventricular hypertrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1524–1530, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrick CJ, Rojas M, Schoonhoven R, Smyth SS, Threadgill DW. Cardiac response to pressure overload in 129S1/SvImJ and C57BL/6J mice: temporal- and background-dependent development of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2119–H2130, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DW, Giles WH, Croft JB. Left ventricular hypertrophy as a predictor of coronary heart disease mortality and the effect of hypertension. Am Heart J 140: 848–856, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Simone G, Gottdiener JS, Chinali M, Maurer MS. Left ventricular mass predicts heart failure not related to previous myocardial infarction: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur Heart J 29: 741–747, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeChiara TM, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Parental imprinting of the mouse insulin-like growth factor II gene. Cell 64: 849–859, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggenschwiler J, Ludwig T, Fisher P, Leighton PA, Tilghman SM, Efstratiadis A. Mouse mutant embryos overexpressing IGF-II exhibit phenotypic features of the Beckwith-Wiedemann and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndromes. Genes Dev 11: 3128–3142, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill AE, Lander ES, Nadeau JH. Chromosome substitution strains: a new way to study genetically complex traits. Methods Mol Med 128: 153–172, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoit BD, Kiatchoosakun S, Restivo J, Kirkpatrick D, Olszens K, Shao H, Pao YH, Nadeau JH. Naturally occurring variation in cardiovascular traits among inbred mouse strains. Genomics 79: 679–685, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang CY, Hao LY, Buetow DE. Insulin-like growth factor-II induces hypertrophy of adult cardiomyocytes via two alternative pathways. Cell Biol Int 26: 737–739, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CY, Hao LY, Buetow DE. Insulin-like growth factor-induced hypertrophy of cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes is L-type calcium-channel-dependent. Mol Cell Biochem 231: 51–59, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SD, Chu CH, Huang EJ, Lu MC, Liu JY, Liu CJ, Hsu HH, Lin JA, Kuo WW, Huang CY. Roles of insulin-like growth factor II in cardiomyoblast apoptosis and in hypertensive rat heart with abdominal aorta ligation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E306–E314, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li YH, Reddy AK, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Entman ML, Hartley CJ. Doppler evaluation of peripheral vascular adaptations to transverse aortic banding in mice. Ultrasound Med Biol 29: 1281–1289, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Yan H, Dawes NJ, Mottino GA, Frank JS, Zhu H. Insulin-like growth factor II induces DNA synthesis in fetal ventricular myocytes in vitro. Circ Res 79: 716–726, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llamas B, Belanger S, Picard S, Deschepper CF. Cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte size are governed by different genetic loci on either autosomes or chromosome Y in recombinant inbred mice. Physiol Genomics 31: 176–182, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludwig T, Eggenschwiler J, Fisher P, D'Ercole AJ, Davenport ML, Efstratiadis A. Mouse mutants lacking the type 2 IGF receptor (IGF2R) are rescued from perinatal lethality in Igf2 and Igf1r null backgrounds. Dev Biol 177: 517–535, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews KG, Devlin GP, Conaglen JV, Stuart SP, Mervyn AW, Bass JJ. Changes in IGFs in cardiac tissue following myocardial infarction. J Endocrinol 163: 433–445, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikolic I, Liu D, Bell JA, Collins J, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Treatment with an estrogen receptor-beta-selective agonist is cardioprotective. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42: 769–780, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelzer T, Loza PA, Hu K, Bayer B, Dienesch C, Calvillo L, Couse JF, Korach KS, Neyses L, Ertl G. Increased mortality and aggravation of heart failure in estrogen receptor-beta knockout mice after myocardial infarction. Circulation 111: 1492–1498, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlini S. Determinants of left ventricular mass in hypertensive heart disease: a complex interplay between volume, pressure, systolic function and genes. J Hypertens 25: 1341–1342, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potier M, Karl M, Elliot SJ, Striker GE, Striker LJ. Response to sex hormones differs in atherosclerosis-susceptible and -resistant mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E1237–E1245, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skavdahl M, Steenbergen C, Clark J, Myers P, Demianenko T, Mao L, Rockman HA, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen receptor-beta mediates male-female differences in the development of pressure overload hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H469–H476, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szebenyi G, Rotwein P. Insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in muscle development. Adv Exp Med Biol 293: 289–295, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]