Abstract

A 34-year-old African American woman with sickle cell disease and history of relatively severe hemolysis, chronic leg ulcers, and mild pulmonary hypertension presented with a new ischemic stroke. Recent research has suggested a syndrome of hemolysis-associated vasculopathy in patients with sickle cell disease, which features severe hemolytic anemia and leads to scavenging of nitric oxide and its biochemical precursor L-arginine. This diminished bioavailability of nitric oxide promotes a hemolysis-vascular dysfunction syndrome, which includes pulmonary hypertension, cutaneous leg ulceration, priapism, and ischemic stroke. Additional correlates of this vasculopathy include activation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules, platelets, and the vascular protectant hemeoxygenase-1. Some known risk factors for atherosclerosis are also associated with sickle cell vasculopathy, including low levels of apolipoprotein AI and high levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase. Identification of dysregulated vascular biology pathways in sickle vasculopathy has provided a focus for new clinical trials for therapeutic intervention, including inhaled nitric oxide, sodium nitrite, L-arginine, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, niacin, inhaled carbon monoxide, and endothelin receptor antagonists. This article reviews the pathophysiology of sickle vasculopathy and the results of preliminary clinical trials of novel small-molecule therapeutics directed at abnormal vascular biology in patients with sickle cell disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

The patient is a 34-year-old African American woman with homozygous sickle cell disease (SCD) undergoing hydroxyurea therapy for several years, with an 18-year history of leg ulceration (Figure 1). Steady-state laboratory values included hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL (35th percentile for SCD patients evaluated at the National Institutes of Health [NIH] between 1999–2003), reticulocyte count 370×103/μL (83rd percentile), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) highly elevated at 486 U/L (83rd percentile). The ratio of plasma arginine to ornithine was 0.54 (33rd percentile). The patient was found to have mild elevation of the N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level at 177 pg/mL, and on Doppler echocardiography, a borderline high tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity of 2.5 m/s, both suggestive of mildly elevated pulmonary systolic pressures.

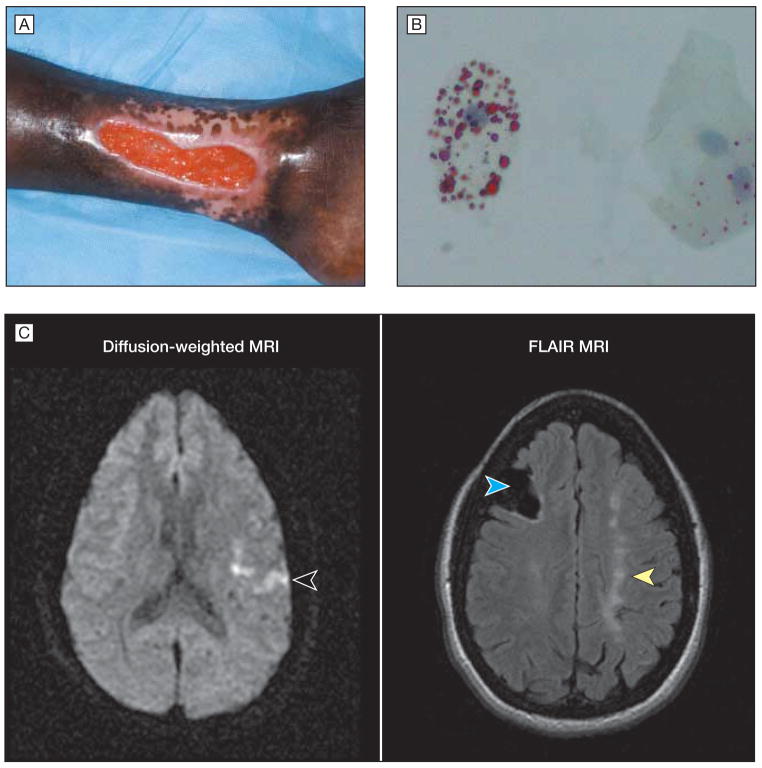

Figure 1.

Presentation of Patient With Sickle Cell Disease

A, The patient had a left medial ankle ulcer of 17 years’ duration. B, One day after hospital admission with vaso-occlusive pain crisis, the patient developed a pulmonary infiltrate, encephalopathy, and renal insufficiency. Induced sputum demonstrated lipid-laden macrophages by oil red O stain (magnification × 1000), which is indicative of fat embolus to the lung from infarcted marrow. C, Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented with acute dysarthria and right-hand weakness. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a bright signal in the left hemisphere (left image, arrowhead), indicating acute edema and new stroke. Additional images at the same time using the FLAIR technique (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) demonstrated right frontal lobe cavitation (right image, left [blue] arrowhead) and chronic watershed zone infarcts (right image, right [yellow] arrowhead) from previously unsuspected ischemic strokes. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed nearly absent flow in the internal carotid arteries (not shown).

During a subsequent hospitalization for vaso-occlusive crisis, the patient developed clinical features of encephalopathy, renal insufficiency, and pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph. Oil red O stain of an induced sputum specimen revealed lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 1) that was consistent with fat embolization from ischemic myelonecrosis. The episode resolved after aggressive transfusion with packed red blood cells. Two weeks after recovering from this episode, the patient developed acute right hemiparesis and dysarthria. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an acute cerebral infarct (Figure 1) that was accompanied by signs of previously unsuspected old focal and watershed zone infarcts (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance angiography demonstrated extremely severe chronic occlusion of bilateral internal carotid arteries with nearly absent blood flow.

COMMENT

During this patient’s lifetime, she has manifested a chronic severe hemolytic anemia accompanied by clinical complications of pulmonary artery systolic hypertension, leg ulcers, and stroke. The more severe hemolytic rate is indicated by her low hemoglobin level, marked reticulocytosis, and high LDH level at steady state, all affected more severely than the average patient with homozygous sickle cell anemia. Her hemolytic severity was likely even more severe for the first 2 decades before beginning hydroxyurea therapy in adulthood, which attenuates the hemolytic rate in SCD. At baseline, she manifested modest elevations in tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity and NT-proBNP, both of which are markers associated with increased pulmonary pressures and early mortality in SCD.1,2 The proliferative cerebrovascular disease of SCD, which caused the extremely severe obstructive vasculopathy and clinically silent previous brain infarcts observed on the magnetic resonance imaging of her brain, likely developed gradually over many years. As we see in this patient’s case, the acute ischemic stroke is often preceded by the acute chest syndrome, which in her case was accompanied by other features of multiorgan failure syndrome, also called the fat or marrow embolization syndrome.3

Epidemiological and mechanistic evidence has evolved over the last several years that pulmonary hypertension (PH), ischemic stroke, cutaneous leg ulceration, and priapism (in males) comprise a clinical syndrome linked to severe intravascular hemolysis, which compromises nitric oxide bioavailability, which is marked by a high plasma hemoglobin, plasma nitric oxide consumption, high serum LDH, high plasma arginase activity, and low ratio of arginine to ornithine.4 It is unclear whether these chronic vascular complications are mechanistically related to the syndrome of rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, and sudden death occasionally observed in individuals with sickle trait.5 As additional investigations unfold, there are a number of additional features of this sickle vasculopathy that appear to overlap with another more well-known proliferative arteriopathy, namely atherosclerosis. We will review the data supporting this model and the new therapeutic targets identified through this new understanding of disease mechanism.

Scavenging of Nitric Oxide by Cell-Free Plasma Hemoglobin

The polymerization of sickle hemoglobin induces red blood cell rigidity that impairs blood flow in the microcirculation. Sickling also induces red blood cell membrane damage and depletion of cellular antioxidant capacity associated with a severe hemolytic anemia.6 One of the important consequences of intravascular hemolysis is the release of red blood cell contents into plasma that are normally compartmentalized away from endothelial cells. This results in loss of the diffusion barriers that normally prevent hemoglobin from reacting with nitric oxide, the crucial regulator of vascular homeostasis. In this rapid, nearly diffusion-limited reaction, nitric oxide reacts with plasma hemoglobin to yield inert nitrate and methemoglobin and produces a state of reduced nitric oxide bioavailability.7 The relative deficiency of nitric oxide contributes to a chronic vasoconstriction, endothelial expression of cell adhesion molecules, and activation of hemostatic pathways that includes activation of platelets.

The best characterized clinical consequence of nitric oxide scavenging due to intravascular hemolysis is PH. Approximately one-third of adults with SCD have at least mild PH, as indicated on screening echocardiography studies by a tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity of 2.5 m/s or higher.1,8,9 The pulmonary pressure rises with time, often producing dyspnea on exertion by the time the tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity reaches 3 m/s, which is observed in 9% of adult patients.10 Progressive PH produces right ventricular failure and eventual cor pulmonale. SCD patients with even mild elevations of tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity of 2.5 m/s or greater have an approximately 10-fold relative risk for early mortality, even higher with concurrent left ventricular diastolic dysfunction.1,11,12

Death in these patients often occurs before the full development of cor pulmonale, perhaps because their cardiovascular functional reserve is weakened by chronically high cardiac output, decreased oxygen-carrying capacity due to severe anemia, and by the chronic organ dysfunction often seen in adults with SCD. Markers of high pulmonary pressure, including high tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity or elevated serum NT-proBNP, are the most sensitive predictors of early death in SCD.1,2,9,11

Mortality in patients who develop acute chest syndrome, a vaso-occlusive episode in the lung induced most commonly by infection or by embolization of infarcted marrow and fat (as in this patient), is limited to those patients who have the most severely elevated tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity accompanied by fulminant progression of right ventricular failure.13 Antecedent high tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity at steady state appears to contribute to this more severe tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity elevation during acute vaso-occlusion.14

Limits in Nitric Oxide Synthase Substrate Availability by Arginase

Arginase is another red blood cell cytoplasmic protein released into plasma during intravascular hemolysis. Converting arginine to ornithine as part of the urea cycle in other tissues, arginase-1 is of uncertain physiological function in the red blood cell. It is particularly abundant in red blood cells from patients with SCD, which suggests that arginase activity is highest in young red blood cells and reticulocytes, similar to many other red blood cell enzymes. Its decompartmentalization from the erythrocyte to plasma in patients with SCD is associated with 39% lower arginine plasma levels compared with African American control participants with slightly higher mean (SD) ornithine levels.15

The resulting low arginine-to-ornithine ratio of 0.71 (0.39) vs 1.20 (0.49) (P<.001) suggests that the ectopically localized arginase enzyme is active in plasma.16 Mean (SD) low arginine-to-ornithine ratio is related in SCD patients to PH status, categorized as normal, mildly elevated, or highly elevated at 0.74 (0.41) vs 0.72 (0.39) vs 0.49 (0.18), respectively (P = .03, linear regression). SCD patients with a low arginine-to-ornithine level have a 2.5-fold risk ratio for early mortality (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–5.2; P=.006). The arginase-linked limitation in nitric oxide production appears to compound the clinical impact of the rapid nitric oxide consumption induced by cell-free plasma hemoglobin.15

Intravascular Hemolysis and Decreased Nitric Oxide Bioavailability Marked by LDH

A third protein released into plasma during intravascular hemolysis is LDH. Although this enzyme is found in every tissue of the body and released during damage to that tissue, the red blood cell LDH isoenzymes appear to account for much of the variability in serum LDH levels in SCD patients at steady state.17 Although LDH is not postulated to cause vasculopathy, it is a sensitive and easily measured surrogate marker of levels of plasma hemoglobin, arginase, nitric oxide consumption, and nitric oxide resistance as measured in forearm blood flow physiology studies in patients with SCD.

Patients with SCD in the highest quartile of LDH have a 61% prevalence of PH compared with 31% in the middle LDH quartiles, and 15% in the lowest LDH quartile (P < .001).17 Patients in the highest LDH quartile also have the highest prevalence of cutaneous leg ulceration and priapism (in males), which suggests that both complications are also related to disordered nitric oxide metabolism associated with intravascular hemolysis. The relationship of PH, leg ulcers, and priapism to intravascular hemolysis is supported by numerous reports of their occurrence in patients with other nonsickling hemolytic diseases.4

In contrast, high steady-state LDH levels are not associated with incidence of vaso-occlusive pain crisis, the acute chest syndrome, or osteonecrosis. Patients with above-median LDH values also have significantly earlier mortality.17 These results suggest that LDH might be a risk marker for the development of vasculopathic complications and related mortality, although this remains to be validated prospectively.

Endogenous Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibitors and PH

Asymmetric dimethylarginine is a naturally occurring inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase that is strongly associated with atherosclerosis and risk of death in the general population. It is normally produced through proteolysis of proteins that have been methylated on arginine residues, a common posttranslational protein modification. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is present at high levels in plasma from patients with SCD.18,19 Our own recent work has indicated that asymmetric dimethylarginine levels are highest in SCD patients with the highest hemolytic rate. Patients with PH have high asymmetric dimethylarginine levels, which suggests that asymmetric dimethylarginine and nitric oxide synthase inhibition might compound the hemolysis-related defect in nitric oxide bioavailability in patients with SCD19 (Kato et al). Moreover, our data indicate that homozygous SCD patients with higher than median asymmetric dimethylarginine levels have a significantly higher mortality rate than those with lower asymmetric dimethylarginine levels.

Association Between Disordered Apolipoprotein Metabolism and Endothelial Dysfunction in SCD

Apolipoprotein AI (apo AI) is a plasma protein required for normal endothelial function and reverse cholesterol transport in the general population, and low levels predict risk of cardiovascular disease. The levels of apo AI have been found to be low in patients with SCD.20,21 Recent data from our group indicate that patients with lower than median levels of apo AI have endothelial dysfunction, demonstrated by blunted vasodilatory effect of brachial artery infusions of acetylcholine.22 There is a trend toward highest prevalence of PH in SCD patients in the lowest quartile of apo AI levels (P=.06, log-rank test). Preliminary findings suggest that higher levels of other apolipoproteins are associated with PH in SCD, including apo AII, apo B, and serum amyloid A.22 High levels of these apolipoproteins are associated with cardiovascular disease in the general population. These results are consistent with correction of severe endothelial dysfunction in the sickle cell mouse by L4F, an apo AI mimetic drug, as indicated by improved vasodilatory response to acetylcholine.23

Activation of Endothelial Cells in Patients With SCD

Endothelial cell activation is a common feature of endothelial dysfunction in the general population. Activated endothelial cells are significantly more adhesive to platelets and leukocytes and promote in situ thrombosis. Patients with SCD have high levels of markers of endothelial activation, including soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, intercellular adhesion molecule 11, E-selectin, and P-selectin.24–30 In particular, the levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and endothelial soluble adhesion molecules display associations with PH and early mortality.31,32 Activated endothelial cells are significantly more adhesive to sickle erythrocytes and leukocytes in ex vivo rodent models of SCD, and vascular expression of adhesion molecules is associated with retinal disease in SCD.33–43

Clearly, endothelial cells are activated in patients with SCD, and particularly so in PH. This may be due to high levels of cytokines that are known to induce these adhesion molecules, and to low nitric oxide bioavailability since nitric oxide is known to suppress their expression.44–50 These activated endothelial cells may provide a platform in specific organs like the lung for decreased vasodilation, blood cell adhesion, and in situ thrombosis. Endothelial cells have different properties in the vascular beds of different organs, and hypothetically those in the target organs of sickle cell vasculopathy may be those vascular beds most dependent on nitric oxide bioactivity for normal function.

The Link Between Platelet and Hemostatic Activation, Hemolysis, and PH

Increased platelet activation, which increased further during vaso-occlusive crisis,51,52 was reported in patients with SCD several years ago. More recently, our group has confirmed and extended these observations. The percentage of circulating platelets that are activated correlates to the tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (r=0.58; P<.001), which suggests that the same mechanisms driving PH might also be driving platelet activation.53 Corroborating this idea, platelet activation also correlates with markers of hemolysis, including low hemoglobin level and high LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte counts. Since part of the program of nitric oxide activity is to suppress platelet activation, it appears likely that hemolysis-associated nitric oxide deficiency promotes platelet activation in SCD in parallel with promoting pulmonary vasoconstriction and vasculopathy. Consistent with this model, addition of cell-free hemoglobin ex vivo to platelets from healthy control participants causes platelet activation.53 More importantly, cell-free hemoglobin inhibits the ability of a nitric oxide donor to suppress platelet activation.

Further investigation is needed to determine whether these activated platelets are predisposed to form in situ pulmonary thromboses, a well-described complication of this and other forms of PH. In addition to this hemolysis-linked platelet activation, 2 other groups have reported hemolysis-linked hemostatic activation in SCD. Both groups found a significant correlation between markers of hemolytic severity and several markers of hemostatic activation, including thrombin-antithrombin complexes, fibrinogen plus prothrombin fragment, and dimerized plasmin fragment D.54,55 Trends toward association of these hemostatic activation markers with pulmonary hypertension were not significant in either group, but statistical power was limited in these 2 studies by the relatively small cohort sizes. Hemolysis appears to provoke activation of the cellular and plasma protein phases of hemostasis in patients with SCD, and this may be a factor in PH.

Heme-Oxygenase–Carbon Monoxide Pathway

Free heme, a breakdown product of hemoglobin, is an oxidative substance that is toxic to the vascular system. One of the redundant vasculoprotective pathways of heme metabolism includes heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which breaks the heme ring. HO-1 provides anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, antiapoptotic, and antioxidant properties to the vasculature, which prevents atherosclerosis in the general population. HO-1 mediates these effects through its products carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and bilirubin. In mice with SCD, Nath et al have found high-level expression of HO-1 in circulating endothelial cells and renal blood vessels.56

Our group also has shown HO-1 messenger RNA in peripheral blood monocular cells elevated 2-fold higher than African American control participants associated with a 1.5-fold increase in the subunits of biliverdin reductase, and a 3-fold increase in total bilirubin, which is the end product of this pathway.57 HO-1 messenger RNA levels correlated significantly with a marker of carbon monoxide generation, carboxyhemoglobin levels, and with other markers of hemolysis including serum bilirubin and LDH. In 2 sickle cell mouse models, Belcher et al also found high-level HO-1 expression.58 These results suggest that hemolysis induces expression of HO-1 and biliverdin reductase in order to detoxify the oxidant stress of free heme.

Parallels of Sickle Vasculopathy to Atherosclerosis

Pulmonary hypertension, currently the most actively investigated component of the sickle vasculopathy syndrome, has many overlapping features with atherosclerosis (the best-described vasculopathy in the general population; Table). They are histopathologically very similar. Both are proliferative vasculopathies that feature oxidant stress, endothelial activation, and dysfunction, with platelet activation and in situ thrombosis. As summarized in the table, many other features also overlap. One notable difference is that atheromas are rarely seen in SCD and perhaps this relates to the very low total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels well described in SCD.59 In the NIH cohort, median level of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 81 mg/dL in SCD patients, compared with a reference range of 65 to 129 mg/dL (to convert cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply values by 0.0259). We would elaborate on the chronic sickle vasculopathy first described by Hebbel et al60 as mechanistically resembling atherosclerosis, but without atheromas and with a predisposition to slightly different vascular beds.

Table.

Comparison of Atherosclerosis and Sickle Cell Pulmonary Hypertension

| Observation | Atherosclerosis | Sickle Cell Pulmonary Hypertension |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular smooth muscle proliferation | Yes | Yes |

| Decreased nitric oxide bioactivity | Yes | Very severe |

| Oxidant stress | Yes | Yes |

| Endothelial dysfunction | Yes | Yes |

| Endothelial activation | Yes | Yes |

| Endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitors | Yes | Yes |

| Disordered apolipoproteins | Yes | Yes |

| Platelet activation | Yes | Yes |

| In situ thrombosis | Yes | Yes |

| Accelerated in renal insufficiency | Yes | Yes |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Yes | No |

| Atheroma formation | Yes | No |

| Commonly affected vascular beds | Coronary, cerebral | Pulmonary, cerebral |

Vascular Targets for Novel Small-Molecule Drugs

Inhaled Nitric Oxide

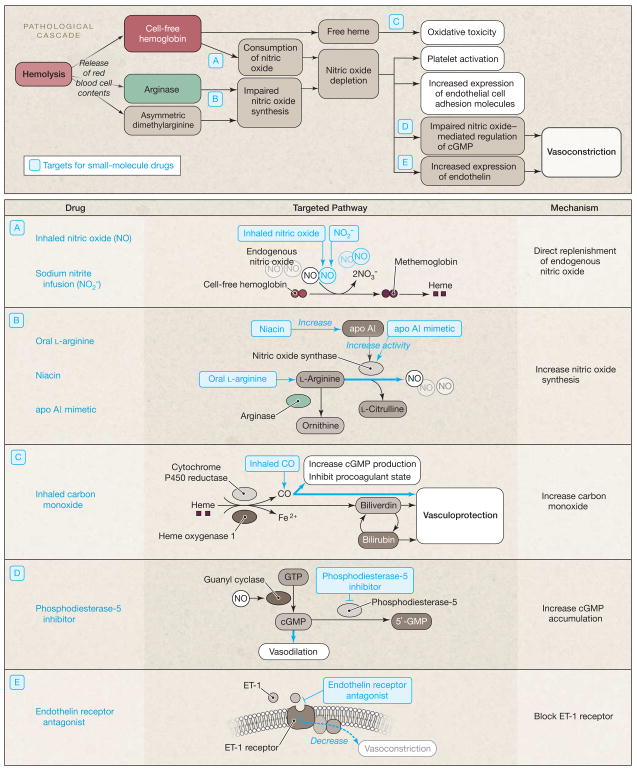

The development of a vascular model as a contributor to pathology in SCD provides a basis for new therapeutic strategies (Figure 2). Inhaled nitric oxide gas will react preferentially with the circulating plasma hemoglobin in the pulmonary vasculature to oxidize it to methemoglobin. Because methemoglobin will not react with and scavenge nitric oxide, this will limit the systemic vasopressor effects of plasma hemoglobin.7 Accordingly, in patients with SCD treated with inhaled nitric oxide, there was a significant conversion of the plasma hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which was associated with significant reductions in the ability of plasma to react with and quench nitric oxide.7 In a canine intravascular hemolysis model, inhaled nitric oxide attenuated the systemic and pulmonary vasoconstrictor effect of plasma hemoglobin and restored vascular responsiveness to sodium nitroprusside, an infused nitric oxide donor.61 A small pilot trial has suggested that inhalation of nitric oxide gas reduces pain in sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain crisis. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of children with SCD presenting with vaso-occlusive pain crisis, 10 children treated with inhaled nitric oxide at 80 ppm for 4 hours had lower pain scores and lower morphine use than 10 children who received placebo gas, without toxicity.62 A multicenter phase 2 clinical trial, the Delivery of Nitric Oxide for Vaso-Occlusive crisis (DeNOVO), is close to completion (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00094887).

Figure 2.

Pathological Cascade Caused by Intravascular Hemolysis and Targets for Pharmacologic Intervention in Sickle Cell Disease

apo AI indicates apolipoprotein AI; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; CO, carbon monoxide; ET, endothelin; Fe, iron; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; NO, nitric oxide.

Sodium Nitrite, a Novel Nitric Oxide Donor

The anion nitrite NO2 can be reduced by deoxyhemoglobin, deoxymyoglobin, and other deoxygenated heme enzymes to form nitric oxide and regulate physiological blood flow and hypoxic vasodilation.63–66 Nitrite has also been found to provide potent cytoprotection after ischemia-reperfusion injury to the heart, liver, and brain in animal models.67–70 This suggests that nitrite therapy might represent a novel hypoxia-targeted therapy for SCD (Figure 2).

A pilot trial from our group has demonstrated that nitrite induces vasodilation and enhances regional blood flow in adults with SCD.71 In a phase 1/2 clinical trial in 14 adults with homozygous SCD at steady state, sodium nitrite was infused into the brachial artery and blood flow was monitored by venous occlusion strain gauge plethysmography. In a dose-dependent manner, sodium nitrite infusion rates of 0.4, 4, and 40 μmol/min augmented mean venous plasma nitrite concentrations (P <.001) and stimulated forearm blood flow as much as 77% (SD, 11%) greater than baseline (P <.001).71 This nitrite response was blunted significantly compared with control patients without SCD, mimicking the pattern observed with other nitric oxide donors like sodium nitroprusside. Because sodium nitrite can be converted to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin at acid pH and low oxygen tension,72 we hypothesize it would ameliorate vaso-occlusive tissue infarction in SCD, and clinical trials are in preparation to test its potential to improve the outcome of vaso-occlusive episodes in patients with SCD. Consistent with this thesis, in a recent study of canine hemolysis, sodium nitrite increased blood flow in animals with plasma hemoglobin levels similar to those of patients with SCD.73

Arginine, Substrate for Nitric Oxide Synthase

Dietary supplementation of L-arginine has been studied as a means to correct its deficiency in SCD due to arginase activity, and to improve its availability as a substrate for nitric oxide synthase activity. In mouse models of SCD, arginine also significantly increased nitric oxide metabolites and certain antioxidant levels. It also reduced hemolysis, nitric oxide resistance, lipid peroxidation, and Gardos channel activity.74–76 In a pilot study, administration of large doses of arginine appeared to reduce pulmonary pressures in SCD patients with PH. Oral arginine, 0.1 g/kg of body weight, produced a 15.2% mean (SD) reduction in estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 63.9 (13) mm Hg to 54.2 (12) mm Hg (P=.002) after 5 days of therapy in 10 patients with SCD.77 Additional clinical trial results in patients with SCD are forthcoming.

Phosphodiesterase 5-Inhibitors

Under normal conditions, nitric oxide exerts its vascular effects principally by activating soluble guanylyl cyclase, which boosts intracellular levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). In the penile and pulmonary vascular beds, this signal transduction pathway is counterbalanced by phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme, which hydrolyzes cGMP. Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors slow the breakdown of cGMP, prolonging and amplifying nitric oxide–mediated signals in the pulmonary vasculature, and sildenafil is now approved for PH in the general population.

In a pilot study from our group, sildenafil therapy used in SCD patients for approximately 6 months decreased the mean (SD) estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure from 50 (4) mm Hg to 41 (3) mm Hg (difference, 9 mm Hg; 95% CI, 0.3 to 17 mm Hg; P=.04) and improved the mean (SD) 6-minute walk distance 384 m (30) to 462 m (28) (difference, 78 m; 95% CI, 40–117; P=.001). Confirmatory data have been reported in SCD and also in thalassemia (Figure 2).78 An NIH-sponsored multicenter clinical trial of sildenafil in SCD PH is now in progress (clinical-trials.gov identifier NCT00492531). Interestingly, 2 preliminary case series suggest its effectiveness also in sickle cell priapism.79,80 Sildenafil also reduces excessive platelet activation in SCD patients with PH.53

Augmenting Apo AI Levels

Niacin, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of dyslipidemias, is known to boost apo AI levels and endothelial-dependent blood flow in patients with hypercholesterolemia and our group is exploring its potential to improve blood flow in patients with SCD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00508989). L4F, a peptide mimetic of apo AI, has also been reported to improve endothelial dysfunction in the SCD mouse model.23

Carbon Monoxide

Inhaled carbon monoxide at low doses has shown therapeutic potential in mouse models of SCD. In the S+S-Antilles sickle cell mouse, carbon monoxide inhibits vascular stasis mediated in part via the transcription factor NF (nuclear factor)–κB, including expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules.58 This is consistent with data from another group that implicates carbon monoxide as a mediator of the vasorelaxation, antiproliferation, anti-inflammation, and neurotransmission downstream activities of HO-1.81 On the basis of these preclinical results, inhaled carbon monoxide at low concentrations may have therapeutic potential as a vasculoprotective or anti-inflammatory agent. A current clinical trial is testing the potential efficacy of inhaled carbon monoxide at low concentrations in reducing acute airway inflammation (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00094406).

Endothelin Receptor Blockade

Endothelin-1 (ET-1), a small peptide hormone, is the most potent known endogenous vasoconstrictor. Nitric oxide normally represses ET-1 secretion and high levels are commonly found in low nitric oxide states. ET-1 is present at pathologically high levels in PH and antagonists of its receptor are approved for PH treatment (bosentan, ambrisentan, and sitaxsentan). A multicenter trial of bosentan in sickle cell PH was discontinued early secondary to slow enrollment and data are currently being analyzed (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT00310830, NCT00313196, and NCT00360087).

Patients with SCD tend to have high baseline ET-1 levels, which rise even higher during vaso-occlusive crisis. In a mouse model of sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis, Sabaa et al82 have found that bosentan can reduce hypoxia-induced vascular congestion in the lung and the kidney. Bosentan improved renal blood flow after hypoxia and reduced inflammation and tissue infiltration by neutrophils, which resulted in reduced nitrative stress. It also reduced hypoxia-induced mortality. Pilot clinical trials of bosentan during vaso-occlusive crisis are needed to determine whether endothelin receptor blockade is beneficial in patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Sickle cell vasculopathy constitutes a subphenotype of SCD including PH, ischemic strokes, cutaneous leg ulceration, and priapism that are epidemiologically linked, and with a presumably shared mechanism involving decreased nitric oxide bioavailability linked to intravascular hemolysis. The current model suggests that risk factors for developing this vasculopathy subphenotype include especially severe hemolysis, increasing age, iron overload, low levels of apo AI, and endothelial progenitor cells. Additionally, systemic hypertension, renal insufficiency, and subtle cholestatic liver dysfunction appear to be either causes or consequences of the subphenotype.1

This pathobiological insight suggests a new approach for assessing risk of specific complications and provides new targets for potential therapeutic intervention. Treatments proven to be of benefit in atherosclerosis should be tested for possible prevention of sickle cell vasculopathy in SCD patients at highest risk, including those with particularly high hemolytic rates. Further research is needed to determine whether the prevalence of sickle cell vasculopathy is reduced by hydroxyurea, which reduces the incidence of vaso-occlusive pain crisis and the acute chest syndrome. Efforts to induce fetal hemoglobin to high levels in a pancellular erythrocyte distribution should also be considered.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Drs Kato and Gladwin have been supported by intramural funds from the Department of Intramural Research of the NIH Clinical Center and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Dr Gladwin currently receives support from the Institute of Transfusion Medicine, the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania, and grant support through an NIH Collaborative Research and Development Agreement of inhaled nitric oxide gas with Ikaria.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

Footnotes

AT THE CLINICAL CENTER OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Author Contributions: Dr Kato had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kato, Gladwin.

Acquisition of data: Kato, Gladwin.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kato, Gladwin.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kato.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Gladwin.

Statistical analysis: Kato.

Obtained funding: Gladwin.

Study supervision: Kato, Gladwin.

Financial Disclosures: Dr Gladwin reports being named as a coinventor on a National Institutes of Health (NIH) government patent application for the therapeutic use of nitrite salts for cardiovascular indications and on a second patent for a hemoglobin-based blood substitute. Dr Kato reported no disclosures.

Additional Information: The patient data were collected as part of a registered clinical research protocol (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00081523). The patient presented in this article reviewed its contents and consented in writing to its publication.

Additional Contributions: We acknowledge the many research contributions from the staff of the Pulmonary and Vascular Medicine Branch of NHLBI, the Critical Care Medicine Department of the NIH Clinical Center, and the many sickle cell patients who have enrolled in these clinical trials.

Contributor Information

Gregory J. Kato, Critical Care Medicine Department, Clinical Center, and Pulmonary and Vascular Medicine Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Mark T. Gladwin, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and the Hemostasis and Vascular Biology Research Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado RF, Anthi A, Steinberg MH, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels and risk of death in sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2006;296 (3):310–318. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohene-Frempong K. Stroke in sickle cell disease: demographic, clinical, and therapeutic considerations. Semin Hematol. 1991;28(3):213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Rev. 2007;21(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell BL. Sickle cell trait and sudden death–bringing it home. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(3):300–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT. Mechanisms and clinical complications of hemolysis in sickle cell disease and thalassemia. In: Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs DR, Nagel RL, editors. Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. 2. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, et al. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med. 2002;8(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ataga KI, Sood N, De GG, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 2004;117(9):665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Castro LM, Jonassaint JC, Graham FL, Ashley-Koch A, Telen MJ. Pulmonary hypertension associated with sickle cell disease: clinical and laboratory endpoints and disease outcomes. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(1):19–25. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado RF, Gladwin MT. Chronic sickle cell lung disease: new insights into the diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(4):449–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ataga KI, Moore CG, Jones S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sickle cell disease: a longitudinal study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(1):109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachdev V, Machado RF, Shizukuda Y, et al. Diastolic dysfunction is an independent risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(4):472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mekontso Dessap A, Leon R, Habibi A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale during severe acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(6):646–653. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1606OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado RF, Mack AK, Martyr S, et al. Severity of pulmonary hypertension during vaso-occlusive pain crisis and exercise in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(2):319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris CR, Kato GJ, Poljakovic M, et al. Dysregulated arginine metabolism, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and mortality in sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2005;294(1):81–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnog JJ, Jager EH, van der Dijs FP, et al. Evidence for a metabolic shift of arginine metabolism in sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol. 2004;83(6):371–375. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato GJ, McGowan VR, Machado RF, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a biomarker of hemolysis-associated nitric oxide resistance, priapism, leg ulceration, pulmonary hypertension and death in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2006;107(6):2279–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnog JB, Teerlink T, van der Dijs FP, Duits AJ, Muskiet FA. Plasma levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, are elevated in sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(5):282–286. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landburg PP, Teerlink T, Muskiet FA, Duits AJ, Schnog JJ CURAMA Study Group. Plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, are elevated in sickle cell patients but do not increase further during painful crisis. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(7):577–579. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki J, Waterman MR, Cottam GL. Decreased apolipoprotein A-I and B content in plasma of individuals with sickle cell anemia. Clin Chem. 1986;32(1 pt 1):226–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monnet D, Kane F, Konan-Waidhet D, Diafouka F, Sangare A, Yapo AE. Lipid, apolipoprotein AI and B levels in Ivorian patients with sickle cell anaemia. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1996;54(7):285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuditskaya S, Tumblin A, Hoehn GT, et al. Proteomic identification of altered apolipoprotein patterns in pulmonary hypertension and vasculopathy of sickle cell disease. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-142604. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou J, Ou Z, Jones DW, et al. L-4F, an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic, dramatically improves vasodilation in hypercholesterolemia and sickle cell disease. Circulation. 2003;107(18):2337–2341. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070589.61860.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleh AW, Duits AJ, Gerbers A, de Vries C, Hillen HF. Cytokines and soluble adhesion molecules in sickle cell anemia patients during hydroxyurea therapy. Acta Haematol. 1998;100(1):26–31. doi: 10.1159/000040859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnog JB, Rojer RA, Mac Gillavry MR, ten Cate H, Brandjes DP, Duits AJ. Steady-state sVCAM-1 serum levels in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(2):109–113. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duits AJ, Rojer RA, van Endt T, et al. Erythropoiesis and serum sVCAM-1 levels in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(3):171–174. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conran N, Fattori A, Saad ST, Costa FF. Increased levels of soluble ICAM-1 in the plasma of sickle cell patients are reversed by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2004;76(4):343–347. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duits AJ, Pieters RC, Saleh AW, et al. Enhanced levels of soluble VCAM-1 in sickle cell patients and their specific increment during vasoocclusive crisis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81(1):96–98. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan JS, Lip GY, Wright J, Bareford D, Blann AD. Plasma levels of tissue factor and soluble E-selectin in sickle cell disease: relationship to genotype and to inflammation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005;16(3):209–214. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000164431.98169.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setty BN, Stuart MJ, Dampier C, Brodecki D, Allen JL. Hypoxaemia in sickle cell disease: biomarker modulation and relevance to pathophysiology. Lancet. 2003;362(9394):1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato GJ, Martyr S, Blackwelder WC, et al. Levels of soluble endothelium-derived adhesion molecules in patients with sickle cell disease are associated with pulmonary hypertension, organ dysfunction, and mortality. Br J Haematol. 2005;130(6):943–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klings ES, Anton Bland D, Rosenman D, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and left-sided heart disease in sickle cell disease: clinical characteristics and association with soluble adhesion molecule expression. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(7):547–553. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Embury SH, Matsui NM, Ramanujam S, et al. The contribution of endothelial cell P-selectin to the microvascular flow of mouse sickle erythrocytes in vivo. Blood. 2004;104(10):3378–3385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaul DK, Hebbel RP. Hypoxia/reoxygenation causes inflammatory response in transgenic sickle mice but not in normal mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106 (3):411–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belcher JD, Bryant CJ, Nguyen J, et al. Transgenic sickle mice have vascular inflammation. Blood. 2003;101(10):3953–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setty BN, Stuart MJ. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is involved in mediating hypoxia-induced sickle red blood cell adherence to endothelium: potential role in sickle cell disease. Blood. 1996;88 (6):2311–2320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunz Mathews M, McLeod DS, Merges C, Cao J, Lutty GA. Neutrophils and leucocyte adhesion molecules in sickle cell retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(6):684–690. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.6.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaul DK, Liu XD, Zhang X, et al. Peptides based on alphaV-binding domains of erythrocyte ICAM-4 inhibit sickle red cell-endothelial interactions and vaso-occlusion in the microcirculation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291(5):C922–C930. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00639.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walmet PS, Eckman JR, Wick TM. Inflammatory mediators promote strong sickle cell adherence to endothelium under venular flow conditions. Am J Hematol. 2003;73(4):215–224. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setty BN, Betal SG. Microvascular endothelial cells express a phosphatidylserine receptor: a functionally active receptor for phosphatidylserine-positive erythrocytes. Blood. 2008;111(2):905–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belcher JD, Mahaseth H, Welch TE, et al. Critical role of endothelial cell activation in hypoxia-induced vasoocclusion in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(6):H2715–H2725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solovey A, Lin Y, Browne P, Choong S, Wayner E, Hebbel RP. Circulating activated endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(22):1584–1590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsui NM, Borsig L, Rosen SD, Yaghmai M, Varki A, Embury SH. P-selectin mediates the adhesion of sickle erythrocytes to the endothelium. Blood. 2001;98(6):1955–1962. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haraldsen G, Kvale D, Lien B, Farstad IN, Brandtzaeg P. Cytokine-regulated expression of E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in human microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1996;156(7):2558–2565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiecker M, Darius H, Kaboth K, Hubner F, Liao JK. Differential regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression by nitric oxide donors and antioxidants. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63(6):732–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Caterina R, Libby P, Peng HB, et al. Nitric oxide decreases cytokine-induced endothelial activation: nitric oxide selectively reduces endothelial expression of adhesion molecules and proinflammatory cytokines. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(1):60–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI118074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi M, Ikeda U, Masuyama J, Funayama H, Kano S, Shimada K. Nitric oxide attenuates adhesion molecule expression in human endothelial cells. Cytokine. 1996;8(11):817–821. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Johnstone AP. Endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression and lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells: effect of nitric oxide. Exp Cell Res. 1997;235(2):431–434. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Space SL, Lane PA, Pickett CK, Weil JV. Nitric oxide attenuates normal and sickle red blood cell adherence to pulmonary endothelium. Am J Hematol. 2000;63(4):200–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(200004)63:4<200::aid-ajh7>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee SK, Kim JH, Yang WS, Kim SB, Park SK, Park JS. Exogenous nitric oxide inhibits VCAM-1 expression in human peritoneal mesothelial cells: role of cyclic GMP and NF-kappaB. Nephron. 2002;90(4):447–454. doi: 10.1159/000054733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westwick J, Watson-Williams EJ, Krishnamurthi S, et al. Platelet activation during steady state sickle cell disease. J Med. 1983;14(1):17–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wun T, Paglieroni T, Rangaswami A, et al. Platelet activation in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1998;100(4):741–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villagra J, Shiva S, Hunter LA, Machado RF, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ. Platelet activation in patients with sickle disease, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension and nitric oxide scavenging by cell-free hemoglobin. Blood. 2007;110(6):2166–2172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ataga KI, Moore CG, Hillery CA, et al. Coagulation activation and inflammation in sickle cell disease-associated pulmonary hypertension. Haematologica. 2008;93(1):20–26. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Beers EJ, Spronk HM, Ten Cate H, et al. No association of the hypercoagulable state with sickle cell disease related pulmonary hypertension. Haematologica. 2008;93(5):e42–e44. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nath KA, Grande JP, Haggard JJ, et al. Oxidative stress and induction of heme oxygenase-1 in the kidney in sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;158 (3):893–903. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jison ML, Munson PJ, Barb JJ, et al. Blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles characterize the oxidant, hemolytic, and inflammatory stress of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;104(1):270–280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belcher JD, Mahaseth H, Welch TE, Otterbein LE, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Heme oxygenase-1 is a modulator of inflammation and vaso-occlusion in transgenic sickle mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):808–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI26857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sasaki J, Waterman MR, Buchanan GR, Cottam GL. Plasma and erythrocyte lipids in sickle cell anaemia. Clin Lab Haematol. 1983;5(1):35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1983.tb00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hebbel RP, Osarogiagbon R, Kaul D. The endothelial biology of sickle cell disease: inflammation and a chronic vasculopathy. Microcirculation. 2004;11(2):129–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Zhi H, et al. Hemolysis-associated endothelial dysfunction mediated by accelerated NO inactivation by decompartmentalized oxyhemoglobin. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3409–3417. doi: 10.1172/JCI25040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiner DL, Hibberd PL, Betit P, Cooper AB, Botelho CA, Brugnara C. Preliminary assessment of inhaled nitric oxide for acute vaso-occlusive crisis in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2003;289 (9):1136–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9(12):1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, et al. Deoxymyoglobin is a nitrite reductase that generates nitric oxide and regulates mitochondrial respiration. Circ Res. 2007;100(5):654–661. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260171.52224.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(2):156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite restores NO homeostasis and is cardio-protective in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(4):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gonzalez FM, Shiva S, Vincent PS, et al. Nitrite anion provides potent cytoprotective and antiapoptotic effects as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(23):2986–2994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duranski MR, Greer JJ, Dejam A, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1232–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pluta RM, Dejam A, Grimes G, Gladwin MT, Oldfield EH. Nitrite infusions to prevent delayed cerebral vasospasm in a primate model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. JAMA. 2005;293(12):1477–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.12.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Elrod JW, Gundewar S, Ji SY, Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite supplementation protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(48):19144–19149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706579104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mack AK, McGowan VR, Tremonti CK, et al. Sodium Nitrite Promotes Regional Blood Flow in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease: A Phase I/II Study. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(6):971–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang Z, Shiva S, Kim-Shapiro DB, et al. Enzymatic function of hemoglobin as a nitrite reductase that produces NO under allosteric control. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2099–2107. doi: 10.1172/JCI24650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Shiva S, et al. Nitrite reductase activity of hemoglobin as a systemic nitric oxide generator mechanism to detoxify plasma hemoglobin produced during hemolysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H743–H754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00151.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dasgupta T, Hebbel RP, Kaul DK. Protective effect of arginine on oxidative stress in transgenic sickle mouse models. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41(12):1771–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Romero JR, Suzuka SM, Nagel RL, Fabry ME. Arginine supplementation of sickle transgenic mice reduces red cell density and Gardos channel activity. Blood. 2002;99(4):1103–1108. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaul DK, Liu XD, Fabry ME, Nagel RL. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation in transgenic sickle mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(6):H1799–H1806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morris CR, Morris SM, Jr, Hagar W, et al. Arginine therapy: a new treatment for pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):63–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-967OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Derchi G, Forni GL, Formisano F, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil in the treatment of severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Haematologica. 2005;90(4):452–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Feasibility of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in a pharmacologic prevention program for recurrent priapism. J Sex Med. 2006;3(6):1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bialecki ES, Bridges KR. Sildenafil relieves priapism in patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 2002;113(3):252. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ryter SW, Kim HP, Nakahira K, Zuckerbraun BS, Morse D, Choi AM. Protective functions of heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the respiratory system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(12):2157–2173. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sabaa N, de Franceschi L, Bonnin P, et al. Endothelin receptor antagonism prevents hypoxia-induced mortality and morbidity in a mouse model of sickle-cell disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(5):1924–1933. doi: 10.1172/JCI33308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]