Abstract

Keratins 8 and 18 (K8/K18) variants predispose carriers to the development of end-stage liver disease and patients with chronic hepatitis C to disease progression. Hepatocytes express K8/K18 while biliary epithelia express K8/K18/K19. K8-null mice, which are predisposed to liver injury, spontaneously develop anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) and have altered hepatocyte mitochondrial size and function. There is no known association of K19 with human disease and no known association of K8/K18/K19 with human autoimmune liver disease. We tested the hypothesis that K8/K18/K19 variants associate with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), an autoimmune cholestatic liver disease characterized by the presence of serum AMA. In doing so, we analyzed the entire exonic regions of K8/K18/K19 in 201 Italian patients and 200 control blood bank donors. Six disease-associated keratin heterozygous variants were identified in patients versus controls (K8 G62C/R341H/V380I, K18 R411H, and K19 G17S). Four variants were novel and included K19 G17S/V229M/N184N and K18 R411H. Overall, heterozygous keratin variants were found in 17 of 201 (8.5%) PBC patients and 4 of 200 (2%) blood bank donors (p<0.004, OR=4.53, 95% CI=1.5-13.7). Of the K19 variants, K19 G17S was found in 3 patients but not in controls; and all K8 R341H (8 patients and 3 controls) associated with concurrent presence of the previously-described intronic K8 IVS7+10delC deletion. Notably, keratin variants associated with disease severity (12.4% variants in Ludwig stage III/IV versus 4.2% in stages I/II; p<0.04, OR=3.25, 95% CI=1.02-10.40), but not with the presence of AMA. Conclusion: K8/K18/K19 variants are overrepresented in Italian PBC patients, and associate with liver disease progression. Therefore, we hypothesize that K8/K18/K19 variants may serve as genetic modifiers in PBC.

Keywords: intermediate filaments, autoantibodies, cirrhosis, keratin 8, keratin 18, keratin 19

Introduction

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a slowly progressive autoimmune liver disease characterized by periportal intrahepatic inflammation and immune-mediated destruction of the small bile ducts. The loss of cholangiocytes leads to decreased bile secretion and retention of toxic substances and may result in cirrhosis and eventually liver failure.1,2 PBC is found primarily in female patients, with middle-age onset, 1,3 with an estimated prevalence in the US and England of 30-40 per 100,000.4 PBC causes a significant economic burden and a mortality rate in the US of 0.24 per 100,000. 5,6 The cause of PBC is unclear but it is an autoimmune disease that appears to be related to environmental factors, such as chemicals and bacteria, acting on genetically susceptible individuals.1,3 The importance of genetic factors for the susceptibility to PBC is evidenced by the increased incidence among first-degree relatives of affected individuals,7 the high concordance rate among monozygotic twins,8 and the common coexistence with other autoimmune diseases.9 However, no definitive genetic associations with PBC onset or progression are established, though several genetic factors conferring susceptibility to PBC have been investigated.1,10-12

Keratins (K) are the largest subgroup among the intermediate filament (IF) family of cytoskeletal proteins. All IF proteins, including keratins, have a characteristic ‘rod’ domain that is flanked by N-terminal ‘head’ and C-terminal ‘tail’ domains. The 37 known human keratin functional genes, which exclude hair keratins, are grouped into relatively basic type-II (K1-K5/K6a-K6c/K7/K8/K71-K80) and relatively acidic type-I (K9/K10/K12-K20/K23-K28) keratins.13,14 Epithelial cells express at least one type-I and one type-II keratin13 in an epithelial cell-specific manner. For example, ‘simple’ (single-layered secretory or absorptive) epithelia as found in the liver, pancreas and intestine express primarily K8/K18 (with variable levels of K7/K19/K20) while keratinocytes express primarily K5/K14 basally and K1/K10 suprabasally.15 In the liver, hepatocytes express K8/K18 exclusively while biliary epithelia express K7/K8/K18/K19.15 Simple epithelial keratins carry out a number of functions including cytoprotection (e.g., from apoptotic injury); protein targeting and synthesis; and modulation of mitochondrial subcellular organization, size and function.15

The use of transgenic animals as potential human disease models has demonstrated the importance of keratin variants in various epithelial disorders including those involving the epidermis and liver. For example, K8-null mice manifest 94% embryolethality with extensive liver hemorrhage and susceptibility to liver injury.16,17 Similarly, transgenic mice that express K18 Arg89→Cys develop mild chronic hepatitis with a marked predisposition to liver injury.18 These animal model data led to human studies which demonstrated that K8 and K18 variants are over-represented in patients with various types of end-stage liver disease (12.4% of 467 explants) as compared with blood bank controls (3.7% of 349 donors, p<0.0001).19,20 In addition, patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have a K8 variant frequency that increases in a significant manner with fibrosis progression.21 Transgenic mice that express either of the two major human liver disease-associated K8 variants [K8 G62C22 and R341H (unpublished observations)] support the human genetic data since both mouse models are predisposed to liver injury when challenged with hepatotoxins.

Several observations support the hypothesis that K8/K18/K19 variants may predispose to autoimmune liver disease. For example, 12 of the 467 previously analyzed cases of end-stage liver disease were patients with PBC in whom K8/K18 variants were found in 3 patients (25%).20 In addition, serum anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) are found in K8-null mice in association with alterations in mitochondrial size, organization and function (unpublished observations). These observations led us to examine the presence of keratin variants in a well-defined cohort of Italian patients with PBC as compared with blood bank controls. In addition to K8/K18, we also examined the potential presence of genetic K19 variants given K19 expression in biliary epithelia.15 Since the relative expression of simple epithelial keratins in biliary epithelia has not been examined, we also compared the expression of these keratins in the common bile duct and liver with the gallbladder and intestine. Of note, the association of K19 variants has not been described to date in any human disease, although few K19 polymorphisms have been reported in controls and patients with inflammatory bowel disease.23

Materials and Methods

Mice

One month old female FVB/N mice were used to compare keratin expression in several digestive tissues. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by removal of the common bile duct, liver, gallbladder and small intestine. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid N2 for subsequent biochemical analysis. All animals received humane care and their use was approved by the institutional animal care facility.

High salt extraction and Western blot analysis

Enriched keratin fractions were obtained by high salt extraction (HSE) as described.24 The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE followed either by Coomassie blue staining or by transfer to membranes for immunoblotting. Keratins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer) and the primary antibodies (Ab): rabbit anti-human(h)/mouse(m) K18 (Ab 4668)25; rat anti-mK19 (Troma-III; Developmental Hybridoma Bank); mouse anti-h/mK7 (RCR105, Progen Biotechnik GmbH); anti-mK20 (K20.8, Neo-Markers).

PBC patient and control cohorts

Genomic DNA was isolated from well-characterized 209 Italian PBC patients (Milan, Italy) and from 200 Italian blood bank donors (Modena, Italy). The diagnosis of PBC was based on internationally-accepted standards1 including the presence of 2 out of 3 criteria: (i) positive serum AMA, (ii) serum alkaline phosphatase >2× normal for ≥6 months, and/or (iii) a compatible liver histology. In subjects without detectable AMA, the patients had to fulfill both remaining criteria to be enrolled. Serum AMA were determined using indirect immunofluorescence and titers ≥1:40 were considered positive. Patients were considered to be positive for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) when they displayed elevated titers of anti-sp100 or -gp210 antibodies or positive indirect immunofluorescence. Liver biopsy staging was based on Ludwig's criteria,26 and the absence of liver fibrosis was defined as early-stage PBC (Ludwig stages I-II) and the advanced stage was defined as the evidence of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis (Ludwig stages III-IV) or those who had a liver transplant or a cirrhosis-related complication. The Mayo score was employed to evaluate the prognosis of liver disease at the time of DNA sampling.27 Patients positive for serum hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV antibody, with a history of alcohol abuse within one year of diagnosis, or bile duct obstruction (based on ultrasound, computer tomography and/or endoscopic evaluation) were excluded.

Human Genomic DNA Samples and PCR Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral whole blood using DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen Inc). All the exonic regions and exonic-intronic boundaries of K8/K18/K19 were analyzed using previously described primers.21,23 DNA fragments were amplified with a Touchdown PCR protocol using T-TaqTM Polymerase (Transgenomic) to obtain high amplification specificity.28 The PCR reactions were performed with a Gene Amp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems Inc).

Denaturing High Performance Liquid Chromatography (DHPLC)

The human samples were screened for the presence of K8/K18/K19 variants via DHPLC using WAVE™ Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomic).21,28 Samples with a “shifted” elution pattern were purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc) and sequenced bidirectionally to confirm the presence of a mutation. The mRNA sequences of K8 (NM002273), K18 (NM000224) and K19 (NM002276) were used to localize the coding variants while genomic sequences [hKRT8 (M34482), hKRT18 (AF179904) and hKRT19 (AF202321)] were employed for non-coding variants.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, the two-tailed t-test was used to compare two groups together, while the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric one-way ANOVA was used to compare more than two groups. K8/K18/K19 variant frequencies in patient and control groups were compared with the two-tailed Fisher exact probability test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Institute system (Version 9.1.3).

Results

Keratin expression profiles in mouse liver, common bile duct, gallbladder and jejunum

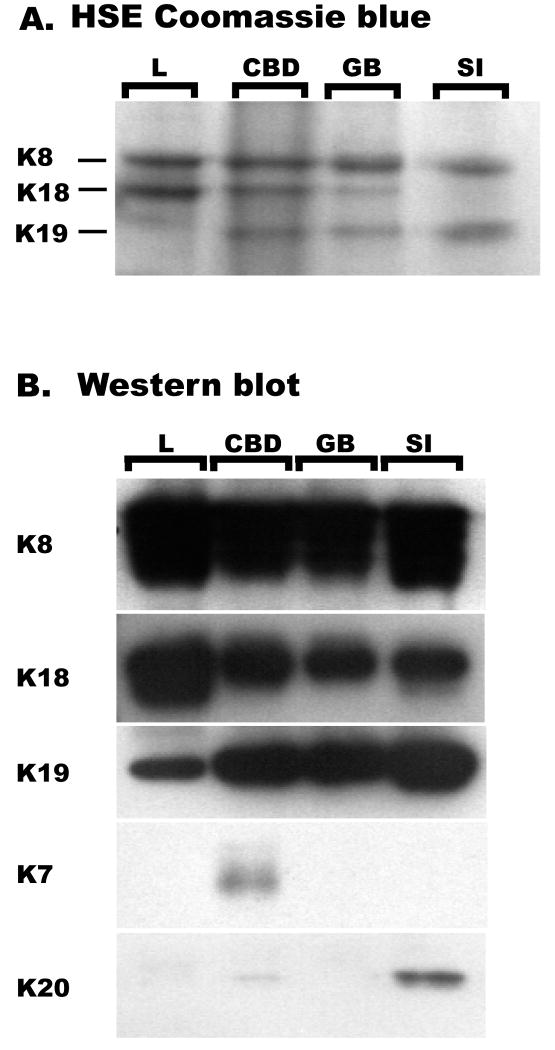

The stoichiometric expression of keratin subtypes in mouse liver, gallbladder and small intestine are known29,30 but those of the common bile duct are not. We analyzed the keratin-enriched protein fractions from these tissues by Coomassie staining (Figure 1A) and immunoblotting (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1, K8/K18/K19 are the major keratins in both gallbladder and common bile duct. In addition, the common bile duct, but not gallbladder, also expresses low levels of K7 and minimal amounts of K20 which can be detected by immune blotting (Figure 1B) but not by Coomassie staining (Figure 1A). In all tested organs, K8 is the major type-II keratin while K19 has limited expression in the liver (because of its absence in hepatocytes but presence in biliary epithelia).

Figure 1. Expression of keratins in the liver, common bile duct, gallbladder and small intestine.

Keratin-enriched fractions were prepared by high salt extraction (HSE) from liver (L), common bile duct (CBD), gallbladder (GB) and small intestine (SI) then separated by SDS-PAGE. The organs were resected from one month old female FVB/N mice. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue (A) or transferred to membranes and immuno blotted with antibodies to the indicated keratin species (B).

Demographics and characteristics of the PBC patients

The demographics and clinical information of the PBC patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 201 patients with PBC were included in the final analysis since 8 patient DNA samples were not reliably amplified. As expected, most patients were female (96%). AMA was positive in 151 patients (75%); 96 patients (48%) exhibited early PBC stages I-II and 105 patients (52%) had advanced disease. Several factors including age, total bilirubin levels and the Mayo score were significantly different in advanced versus early stages (p<0.05).

Table 1. Demographics of the PBC patient cohort**.

| Total n=201 (%) |

Stage I-II n=96 (%) |

Stage III-IV n=105 (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female # | 192 (96%) | 93 (97%) | 99 (94%) | 0.72 |

| Age at enrollment | 53±12 | 51±12 | 55±12 | 0.04 |

| AMA-positive # | 15 (75%) | 73 (76%) | 78 (74%) | 0.74 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.87±0.70 | 0.73±0.55 | 1±0.80 | 0.01 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.13±0.43 | 4.16±0.42 | 4.09±0.43 | 0.24 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.02±0.14 | 1.01±0.16 | 1.02±0.12 | 0.42 |

| Ascites (n) | 7 (3.5%) | 1 (1.04%) | 6 (5.7%) | 0.08 |

| Mayo score | 3.71±0.96 | 3.49±0.74 | 3.98±0.97 | 0.0001 |

The normal values of total bilirubin, albumin and prothrombin time are <1.0, >3.5 and <1.2, respectively (8 patients lacked data for total billirubin, albumin and prothrombin time); INR, international normalized ratio; continuous variables are expressed as the mean±SD; age was unknown in 17 patients; the p-Value compares the patients with mild (Stage I-II) and severe PBC (Stage III-IV).

Detection of keratin variants in PBC patients

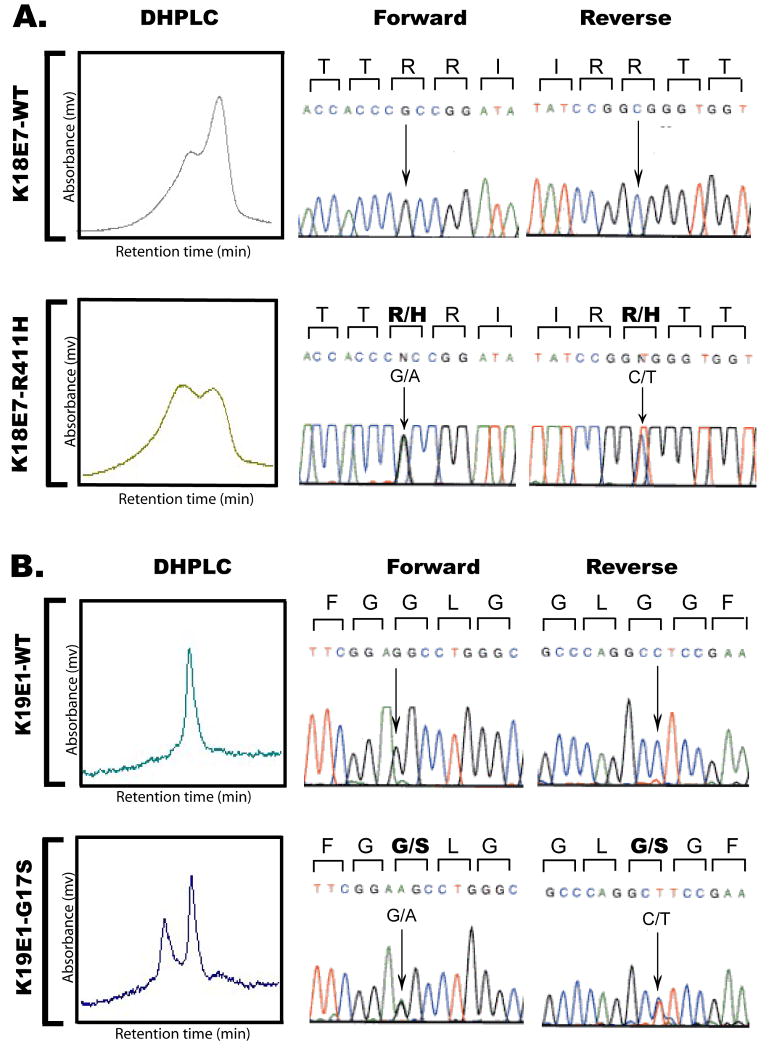

We analyzed all exonic regions of K8, K18 and K19 using DHPLC and subsequent DNA sequencing of the samples that displayed an abnormal elution profile off the DHPLC column. Of the 201 PBC patients, 17 (8.5%) harbored five disease-associated heterozygous exonic variants including three K8 (G62/R341/V380I), one K18 (R411H) (Figure 2A) and one K19 (G17S) (Figure 2B). Keratin variants are defined as ‘disease-associated’ (or biologically relevant) when they meet one or more the following criteria: (i) are overrepresented in liver disease patients when compared to the appropriate control group, (ii) alter a highly conserved amino acid, (iii) introduce or ablate a charge or a posttranslational modification site such as phosphorylation, or (iv) have been shown to cause a phenotype in transgenic mice. The variants K18 R411H and K19 G17S are newly described variants found in one and three PBC patients, respectively, and were not detected in the control group (Table 2; Figure 2). K18 R411 is not conserved among type-I keratins but is conserved across human, mouse and rat species, while K19 G17S is conserved among several type-I keratins (not shown) and across several species (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 2. Detection of keratin variants in patients with PBC and in blood bank donors.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood and individual K18/K19 exonic regions were amplified by touchdown PCR then analyzed by DHPLC. Samples with a shifted chromatogram pattern were sequenced in the forward and reverse directions. The nucleotide locations of the variants were determined as described in “Materials and Methods”. The novel heterozygous K18 exon 7-R411H (A) and K19 exon 1-G17S variants (B) are presented in comparison with their corresponding WT samples.

Table 2. Keratin variants in PBC and control groups+.

| Keratin gene | Variants | PBC (n=201) |

Control (n=200) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nucleotide | amino acid | |||

| KRT8 | 184G→T | G62C | 4 | 0 |

| 1022G→A | R341H | 8 [8] | 3 | |

| 1138 G→A | V380I | 1 | 0 | |

| 187A→G | I63V* | 1 | 0 | |

| 681A→G | L227L** | 28 | 32 | |

| IVS6 + 46A→T*** | 1 | 0 | ||

| IVS7 + 10 Del C*** | 8 [8] | 3 | ||

| KRT18 | 1232G→A | R411H (new) | 1 [1] | 0 |

| 689G→C | S230T* | 2 [1] | 0 | |

| IVS2 + 38G→A*** | 1 [1] | 1 | ||

| KRT19 | 49G→A | G17S (new) | 3 [1] | 0 |

| 685G→T | V229M (new) | 0 | 1 | |

| 179C→G | A60G* | 19 | 20 | |

| 90C→T | A30A** | 18 | 18 | |

| 471T→C | N157N** | 48 | 52 | |

| 552C→T | N184N (new)** | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 17 (8.5%) | 4 (2%) | ||

P<0.004; OR=4.5; 95% CI=1.5-13.7

Amino acids are denoted by the single-letter abbreviations; “new” highlights novel variants which have not been previously reported; brackets indicate the number of compound variants;

highlights “polymorphisms” rather than “mutations” based on previous studies;

highlights “silent” nucleotide mutations that do not result in an amino acid change;

highlights intronic variants, which were assigned to their respective intervening sequence (IVS). Note that the IVS number refers to the neighboring 5′ exon. For example, IVS7 + 10 Del C depicts a non-coding deletion found 10 nucleotides downstream from the 35′-end of exon 7 in intervening sequence 7.

IVS6+ 45A→T highlights a non-coding nucleotide substitution found 45 nucleotide downstream from 35′-end of exon 6 in intervening sequence 6.

Some of the other variants we identified are considered polymorphisms rather than pathogenic mutations. This group included K8 I63V, K18 S230T and K19 G60A, which were observed at comparable frequencies in the control and patient liver disease cohorts in previous studies.20,21 Four ‘silent’ non-amino-acid-altering exonic variants (including the novel K19 N184N) and three intronic variants (including the novel K18 IVS2 + 38G→A found in one patient with PBC and in one control), which did not associate with hepatitis C-related liver disease progression,21 are also considered non-pathogenic (Table 2).

Among the disease-associated variants, K8 R341H was the most common (found in 8 of 17 PBC patients). Seven patients had single and 10 had compound heterozygous variants, including one K18 R411H+K18 S230T, one K19 G17S+K18-IVS2+38G→A and the eight K8 R341H carriers who concurrently carried the K8 IVS7+10delC polymorphism. The exclusive association between K8 R341H and K8 IVS7+10delC, which was noted previously, 21,23 is also present in the control samples.

In the control group, the frequency of disease-associated exonic variants was 2% (4 of 200; that include K8 R341H and K19 V229M). The K8 R341H variant was observed in three subjects, while one donor carried a novel K19 V229M variant (Table 2), which is conserved among species and among several other type-I keratins (Supplemental Figure 1). Notably, there is a significantly higher frequency of disease-associated/biologically-relevant keratin variants (highlighted in bold lettering in Table 2) versus the control groups (p<0.004, OR=4.5, 95%, CI=1.5-13.7).

Relationship of keratin variants with PBC

Of the 17 patients who harbored relevant keratin variants, 4 were seen in 96 patients with early disease-stage (4.2%), while 13 were found in 105 subjects with advanced disease (12.4%; Table 3). The frequency of keratin variants in the advanced stage of PBC was significantly higher than in the early stage (p<0.04, OR=3.25, 95% CI=1.02-10.4), thereby suggesting that keratin variants associate with liver disease progression in PBC. On the other hand, there was no association between keratin variants and the presence of AMA, since 14 of 151 AMA-positive patients (9.3%) had relevant keratin variants as compared with 3 of 50 (6%) AMA-negative patients (p=0.47) (Table 3). The frequency of keratin variants among ANA-negative and ANA-positive PBC patients was also similar (Table 3). The 17 relevant keratin variants were found at similar frequencies in both sexes, and patients carrying the variants did not differ from the overall group with respect to their bilirubin and albumin serum levels, prothrombin time, Mayo score, or the presence of ascites (Table 4). We were not able to include analysis of the estimated duration of disease in those with and without the keratin variants due to incomplete data on cholestasis parameters prior to the diagnosis of PBC.

Table 3. Distribution of disease-associated keratin exonic variants among PBC disease stages, AMA-positive and negative, and ANA–positive and negative PBC patients+.

| Keratin gene | Variants | Stage | AMA | ANA* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I-II (n=96) |

Stage III-IV (n=105) |

AMA negative (n=50) |

AMA positive (n=151) |

ANA negative (n=77) |

ANA positive (n=117) |

|||

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | |||||||

| KRT8 | 184G→T | G62C | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1022G→A | R341H | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 | |

| 1138 G→A | V380I | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| KRT18 | 1232G→A | R411H (new) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| KRT19 | 49G→A | G17S (new) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 4 (4.2%) | 13 (12.4%) | 3 (6.0%) | 14 (9.3%) | 7 (9.0%) | 9 (7.7%) | ||

|

P (OR, 95%CI) |

0.04 (3.25, 1.02-10.4) |

0.47 (1.6, 0.44-5.82) |

0.73 (1.2, 0.42-3.37) |

|||||

Amino acids are denoted by the single-letter abbreviations. “New” highlights novel variants which have not been previously reported.

Seven cases (including one harboring a K8 62C variant) were excluded from analysis due to missing ANA values.

Table 4. The clinical features of PBC patients harboring significant keratin variants+.

| Presence of keratin variants | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=17) | No (n=184) | ||

| Sex (Male/Female) | 1/16 | 8/176 | 0.77 |

| Age at enrollment (year) | 55±13 | 53±12 | 0.59 |

| Total billirubin (mg/dL) | 0.70±0.28 | 0.88±0.73 | 0.30 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.25±0.32 | 4.11±0.44 | 0.22 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.00±0.13 | 1.02±0.14 | 0.56 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 1/16 | 5/171 | 0.53 |

| Mayo score | 3.65±0.20 | 3.82±0.79 | 0.54 |

Normal values of total bilirubin, albumin and prothrombin time are <1.0, >3.5 and <1.2, respectively; INR, international normalized ratio; Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±SD.

Discussion

The importance of keratin variants in human liver disease

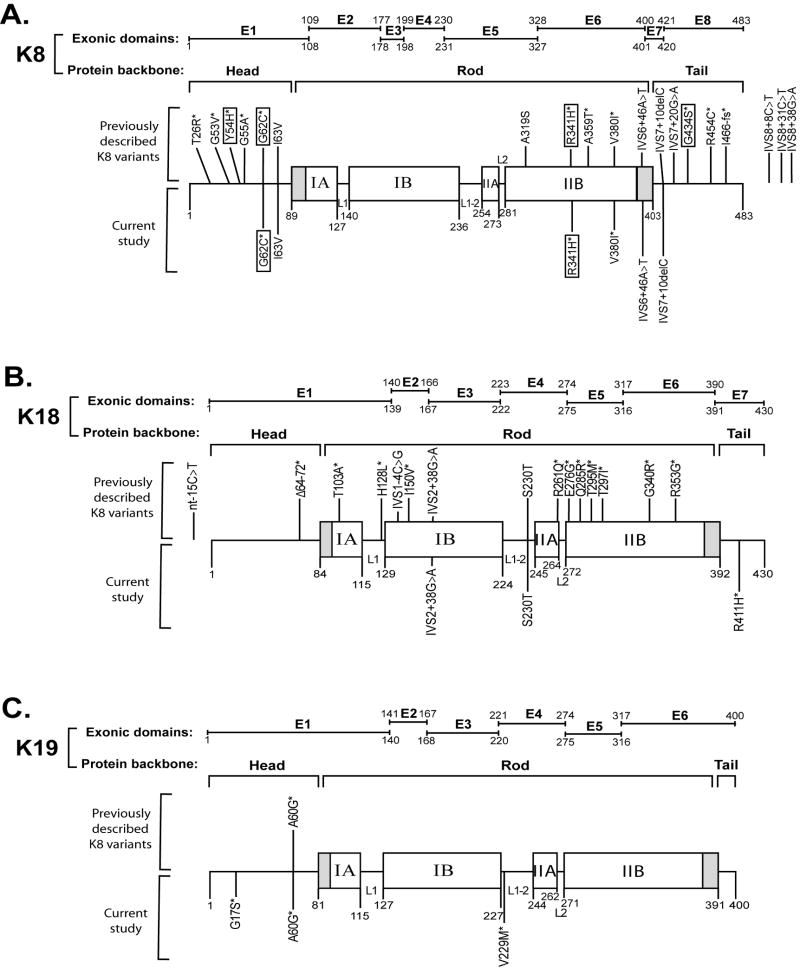

Our results show that keratin variants are over-represented in Italian patients with PBC when compared with blood bank donors (8.4% versus 2%; p<0.004, OR=4.5, 95%, CI=1.5-13.7). The frequency of keratin variants presented here is somewhat lower that seen in a US cohort of explants from patients with end-stage liver diseases of multiple etiologies (12.4% in liver explants versus 3.7% in blood bank controls)20 but similar to that observed in a German cohort with chronic HCV infection (7.8%).21 In addition, the distribution of K8/K18/K19 variants within the keratin protein backbone (Figure 3) mimics the previously published data and highlights several points. First, K8/K18/K19 variants are not found in the helix initiation and termination motifs of the rod domains of K8/K18/K19 (shaded areas at the beginning and end of the rod domain, Figure 3) which are the regions where most epidermal keratin mutations cluster.31,32 This provides a likely explanation as to why K8/K18/K19 mutations pose a prognostic risk rather than cause disease per se. Second, most variants are rare (<1% frequency) which leads us to pool their frequencies when carrying out power analysis. Third, K8 has the most keratin variants, as compared with K18 and K19, which may be related to the observation that K8 is the major keratin in hepatobiliary epithelial cells as observed in mice (Figure 1) and, presumably, also in humans though this has not been tested quantitatively. For K18, the novel R411H variant identified herein is the first K18 tail domain variant described to date.

Figure 3. Distribution of K8/18/19 variants within the keratin backbone.

The schematic shows K8 (A), K18 (B) and K19 (C) exonic regions together with their respective protein domains. Keratins exhibit a tripartite structure consisting of a central α-helical ‘rod’ as well as non-α-helical N-terminal ‘head’ and C-terminal ‘tail’ domains. The rod domain is subdivided into IA, IB, IIA and IIB parts divided by nonhelical linker (L1, L1-2, and L2) sequences. The shaded regions at the beginning and end of rod domains are highly conserved and represent mutation “hot spots” in epidermal keratins and other IF proteins. However, no human K8, K18 or K19 mutations have been identified to date in these hot spots. The K8/K18/K19 variants identified previously are displayed above the keratin protein backbone, while the variants described in this study are drawn below the protein backbone. Amino acids are represented by single-letter abbreviations. The most frequent K8 variants are boxed while unmarked variants are seen at lower frequencies. The likely biologically significant variants are highlighted by an asterisk. K18 R411H and K19 G17S are the two novel variants identified in PBC patients, while K19 V229M was observed only in one healthy blood bank donor. The intervening sequence (IVS) number refers to the neighboring 5′ exon. For example, IVS7 + 10 Del C depicts a non-coding deletion found 10 nucleotides downstream from the 3′-end of exon 7 in intervening sequence 7. E, exon; nt, nucleotides.

Genetic risk factors for human PBC

Genetic factors are likely to play an important role in PBC pathogenesis. For example, family members of patients with PBC have a higher risk of developing the disease with a concordance rate as high as 63% in monozygotic twins,8 which is among the highest reported in autoimmune diseases. Moreover, PBC predominance in females may relate to the higher incidence of X-chromosome monosomy in lymphoid cells.33 Several candidate genes and chromosomal loci have been described, but the data are inconclusive and at times contradictory.1,10,11,12 In addition, the focus has been primarily on proinflammatory and immunoregulatory-related genes, such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), interleukins (IL), T helper 1 (Th1) cells or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d receptor (VDR).3,10,11,12 Therefore, the findings herein provide for the first time a potential link between the keratin cytoskeleton and autoimmune liver disease, possibly also contributing to the high tissue specificity of PBC. To our knowledge, no such association has been described between IF genes and immune response modulation although leukocytes that lack vimentin have a reduced capacity to home to mesenteric lymph nodes and vimentin-null endothelial cells have a compromised integrity.34 In addition, K8-null mice develop spontaneous Th2-type colitis.35,36 It remains to be determined how K8/K18/K19 mutations may predispose to autoimmune liver disease. One hypothesis is that keratin mutation-induced susceptibility to hepatocyte/cholangiocyte injury and death over time results in an autoimmune disease due to release of potential autoantigens in a susceptible host. In support of this, K8-null mice develop serum AMA though they do not develop autoimmune liver disease per se (unpublished observations). Given the expression of K8/K18/K19 in a variety of epithelial tissues, the keratin-variant based predisposition to PBC (and potentially other autoimmune diseases) may also be liver-independent. For example, K8/K18/K19 are found in a subset of thymic epithelial cells, 37 and proper keratin architecture is crucial for thymic microenvironment, as seen in mice ectopically expressing K10 in thymic cells which develop severe thymic alterations.38

K19 joins the ranks of other disease-associated keratins

Our study identified three K19 G17S variants among the 201 PBC patients analyzed. Of note, the K19 G17S variant was not found in the Italian 200 control blood bank donors or in a previous study which analyzed 200 US patients with inflammatory bowel disease and 70 US control subjects (p=0.03 for comparison of PBC versus the pooled Italian and US non-PBC subjects).23 Therefore, the K19 G17S variant is significantly overrepresented in PBC patients, which adds K19 to the list of 16 epithelial keratins, whose variants are known to cause or predispose to the development of human disease.39,40 However, since K19 variants are rare, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings. In addition, further studies using K19-null mice are warranted to characterize the impact of K19-deficiency on liver injury. One study performed so far did not show an obvious liver phenotype in K19-null mice,29 while a mild skeletal mouse myopathy with a complex disorganization of muscular architecture was observed in these animals.41 The lack of an obvious disease phenotype in epithelial tissues of K19-null mice is likely to be related to the functional redundancy imparted by the expression of other type-I keratins (eg, K18 and K20).30,42

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Conservation of K18 R411, K19 G17 and V229 residues among different species and among type I keratins. K18 R411 and K19 G17 residues were found to be altered in one and three PBC patients, respectively, but not in the control blood bank donors. On the other hand, K19 V229 was altered in one control patient, but not in the PBC patients who were studied. The K18 R411 residue is conserved among human, mouse and rat, but not among other species (A). Similarly, K19 G17 (B) is conserved in human, mouse, rat and chicken, but not other species. K19 V229 (C) is conserved among different species, while it is shared only in a few type I keratins. The red rectangles highlight the location of the keratin variants. Amino acids are presented by single-letter abbreviations. Hyphens represent gaps to optimize sequence alignment. The assignment of the specific location of the keratin subdomains was obtained from http://www.interfil.org/proteinsTypeInII.php and includes the start methionine. H=human.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the patients and other donors who have made it possible to carry out the genetic analyses. We also thank Evelyn Resurrection for assistance with the immune staining. Our work is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs and NIH grant DK52951 (M.B.O.); NIH Center grant DK56339 to Stanford University; NIH grant DK39588 (M.E.G); Guangdong province international cooperative grant 2004B50301015 (B.Z.); and the Emmy Noether program of German Research Foundation (grant STR 1095/2-1 to P.S.).

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- AMA

anti-mitochondrial antibody

- DHPLC

denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography

- h

human

- IFs

intermediate filaments

- IVS

intervening sequence

- K

keratin protein

- KRT

keratin gene

- m

mouse

- PBC

primary biliary cirrhosis

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Bihui Zhong, Division of Gastroenterology, First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, PR China; Palo Alto VA Medical Center and Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94304 USA.

Pavel Strnad, Palo Alto VA Medical Center and Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94304 USA; Department of Internal Medicine I, University Medical Center Ulm, Ulm, Germany.

Carlo Selmi, Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatobiliary Immunopathology Unit, Rozzano, Italy; University of Milan, Rozzano, Italy.

Pietro Invernizzi, Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatobiliary Immunopathology Unit, Rozzano, Italy.

Guo-Zhong Tao, Palo Alto VA Medical Center and Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94304 USA.

Angela Caleffi, Center for Hemochromatosis, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy.

Minhu Chen, Division of Gastroenterology, First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, PR China.

Ilaria Bianchi, Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatobiliary Immunopathology Unit, Rozzano, Italy; University of Milan, Rozzano, Italy.

Mauro Podda, Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatobiliary Immunopathology Unit, Rozzano, Italy; University of Milan, Rozzano, Italy.

Antonello Pietrangelo, Center for Hemochromatosis, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy.

M. Eric Gershwin, Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Clinical Immunology, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, USA.

M. Bishr Omary, Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan School of Medicine, 7744 Medical Science II, 1301 E. Catherine Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

References

- 1.Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2003;362:53–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13808-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Zuin M, Podda M, Seldin MF, Gershwin ME. Genes and (auto)immunity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Genes Immun. 2005;6:543–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worman HJ. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis - Etiology, Diagonosis, Natural History, and Treatment. US Gastroenterology Review. 2006:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross RG, Odin JA. Recent advances in the epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendes FD, Kim WR, Pedersen R, Therneau T, Lindor KD. Mortality attributable to cholestatic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology. 2008;47:1241–1247. doi: 10.1002/hep.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bittencourt PL, Farias AQ, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Goncalves LL, Goncalves PL, Magalhaes EP, Carrilho FJ, et al. Prevalence of immune disturbances and chronic liver disease in family members of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:873–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selmi C, Mayo MJ, Bach N, Ishibashi H, Invernizzi P, Gish RG, Gordon SC, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: genetics, epigenetics, and environment. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:485–492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gershwin ME, Selmi C, Worman HJ, Gold EB, Watnik M, Utts J, Lindor KD, et al. Risk factors and comorbidities in primary biliary cirrhosis: a controlled interview-based study of 1032 patients. Hepatology. 2005;42:1194–1202. doi: 10.1002/hep.20907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DE, Donaldson PT. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:841–864. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osterreicher CH, Stickel F, Brenner DA. Genomics of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:28–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juran BD, Lazaridis KN. Genetics and genomics of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulombe PA, Omary MB. ‘Hard’ and ‘soft’ principles defining the structure, function and regulation of keratin intermediate filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schweizer J, Bowden PE, Coulombe PA, Langbein L, Lane EB, Magin TM, Maltais L, et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:169–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omary MB, Ku NO, Strnad P, Hanada S. Towards unraveling the complexity of ‘simple’ epithelial keratins in human disease. J Clin Invest. 2009 doi: 10.1172/JCI37762. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baribault H, Price J, Miyai K, Oshima RG. Mid-gestational lethality in mice lacking keratin 8. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1191–1202. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loranger A, Duclos S, Grenier A, Price J, Wilson-Heiner M, Baribault H, Marceau N. Simple epithelium keratins are required for maintenance of hepatocyte integrity. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1673–1683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku NO, Michie S, Oshima RG, Omary MB. Chronic hepatitis, hepatocyte fragility, and increased soluble phosphoglycokeratins in transgenic mice expressing a keratin 18 conserved arginine mutant. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1303–1314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku NO, Gish R, Wright TL, Omary MB. Keratin 8 mutations in patients with cryptogenic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1580–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku NO, Lim JK, Krams SM, Esquivel CO, Keeffe EB, Wright TL, Parry DA, et al. Keratins as susceptibility genes for end-stage liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:885–893. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strnad P, Lienau TC, Tao GZ, Lazzeroni LC, Stickel F, Schuppan D, Omary MB. Keratin variants associate with progression of fibrosis during chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1354–1363. doi: 10.1002/hep.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ku NO, Omary MB. A disease- and phosphorylation-related nonmechanical function for keratin 8. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:115–125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao GZ, Strnad P, Zhou Q, Kamal A, Zhang L, Madani ND, Kugathasan S, et al. Analysis of keratin polypeptides 8 and 19 variants in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:857–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ku NO, Toivola DM, Zhou Q, Tao GZ, Zhong B, Omary MB. Studying simple epithelial keratins in cells and tissues. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;8:489–517. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)78017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong B, Zhou Q, Toivola DM, Tao GZ, Resurreccion EZ, Omary MB. Organ-specific stress induces mouse pancreatic keratin overexpression in association with NF-kappaB activation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1709–1719. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludwig J, Dickson ER, McDonald GSA. Stageing of Chronic Nonsuppurative Destructive Cholangitis (Syndrome of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis) Virchows Arch A Path Anat and Histol. 1978;379:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00432479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickson ER, Grambsch PM, Fleming TR, Fisher LD, Langangworthy A. Prognosis in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Model for Decision Making. Hepatology. 1989;10:1–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strnad P, Lienau TC, Tao GZ, Ku NO, Magin TM, Omary MB. Denaturing temperature selection may underestimate keratin mutation detection by DHPLC. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:444–452. doi: 10.1002/humu.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao GZ, Toivola DM, Zhong B, Michie SA, Resurreccion EZ, Tamai Y, Taketo MM, et al. Keratin-8 null mice have different gallbladder and liver susceptibility to lithogenic diet-induced injury. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4629–4638. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Q, Toivola DM, Feng N, Greenberg HB, Franke WW, Omary MB. Keratin 20 helps maintain intermediate filament organization in intestinal epithelia. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2959–2971. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ku NO, Strnad P, Zhang BH, Tao GZ, Omary MB. Keratins let liver live: mutations predispose to liver disease and crosslinking generates Mallory-Denk bodies. Hepatology. 2007;46:1639–49. doi: 10.1002/hep.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uitto J, Richard G, McGrath JA. Diseases of epidermal keratins and their linker proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1995–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Battezzati PM, Bianchi I, Grati FR, Simoni G, Selmi C, et al. Frequency of monosomy X in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2004;363:533–535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieminen M, Henttinen T, Merinen M, Marttila-Ichihara F, Eriksson JE, Jalkanen S. Vimentin function in lymphocyte adhesion and transcellular migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:156–62. doi: 10.1038/ncb1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baribault H, Penner J, Iozzo RV, Wilson-Heiner M. Colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation in keratin 8-deficient FVB/N mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2964–2973. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habtezion A, Toivola DM, Butcher EC, Omary MB. Keratin-8-deficient mice develop chronic spontaneous Th2 colitis amenable to antibiotic treatment. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1971–1980. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savino W, Dardenne M. Developmental studies on expression of monoclonal antibody-defined cytokeratins by thymic epithelial cells from normal and autoimmune mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 1988;36:1123–1129. doi: 10.1177/36.9.2457046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos M, Río P, Ruiz S, Martínez-Palacio J, Segrelles C, Lara MF, Segovia JC, et al. Altered T cell differentiation and Notch signaling induced by the ectopic expression of keratin K10 in the epithelial cells of the thymus. J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:543–558. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omary MB, Coulombe PA, McLean WH. Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2087–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szeverenyi I, Cassidy AJ, Chung CW, Lee BT, Common JE, Ogg SC, Chen H, et al. The Human Intermediate Filament Database: comprehensive information on a gene family involved in many human diseases. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:351–60. doi: 10.1002/humu.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone MR, O'Neill A, Lovering RM, Strong J, Resneck WG, Reed PW, Toivola DM, et al. Absence of keratin 19 in mice causes skeletal myopathy with mitochondrial and sarcolemmal reorganization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3999–4008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hesse M, Grund C, Herrmann H, Bröhl D, Franz T, Omary MB, Magin TM. A mutation of keratin 18 within the coil 1A consensus motif causes widespread keratin aggregation but cell type-restricted lethality in mice. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Conservation of K18 R411, K19 G17 and V229 residues among different species and among type I keratins. K18 R411 and K19 G17 residues were found to be altered in one and three PBC patients, respectively, but not in the control blood bank donors. On the other hand, K19 V229 was altered in one control patient, but not in the PBC patients who were studied. The K18 R411 residue is conserved among human, mouse and rat, but not among other species (A). Similarly, K19 G17 (B) is conserved in human, mouse, rat and chicken, but not other species. K19 V229 (C) is conserved among different species, while it is shared only in a few type I keratins. The red rectangles highlight the location of the keratin variants. Amino acids are presented by single-letter abbreviations. Hyphens represent gaps to optimize sequence alignment. The assignment of the specific location of the keratin subdomains was obtained from http://www.interfil.org/proteinsTypeInII.php and includes the start methionine. H=human.