Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that the incidence of animal bites increases at the time of a full moon.

Design

Retrospective observational analysis.

Setting

Accident and emergency department at a general hospital in an English city.

Subjects

1621 consecutive patients, irrespective of age and sex.

Main outcome measures

Number of patients who attended an accident and emergency department during 1997 to 1999 after being bitten by an animal. The number of bites in each day was compared with the lunar phase in each month.

Results

The incidence of animal bites rose significantly at the time of a full moon. With the period of the full moon as the reference period, the incidence rate ratio of the bites for all other periods of the lunar cycle was significantly lower (P <0.001).

Conclusions

The full moon is associated with a significant increase in animal bites to humans.

Introduction

The word “lunacy” is derived from Luna, the Roman goddess of the moon, and from the belief that the power of the moon can cause disorders of the mind.1 The effect of the phases of the moon on human nature and behaviour is well documented; some studies show positive aspects of the association and some show negative aspects. Crime, crisis incidence, human aggression, human births, and traffic accidentsare all positively correlated with the phases of the moon.2–6 Some articles have suggested that the full moon has no influence on human insanity, alcohol intake, drug overdose, trauma, or the volume of patients in emergency departments.7–11

We are not aware, however, of any correlation between the full moon and injury to humans by animals. In ancient mythology the day of the full moon was a day for driving away misfortune and evil. We aimed to determine if any pattern exists of animal attacks on humans during a full moon.

Materials and methods

We collected data on new patients attending the accident and emergency department at Bradford Royal Infirmary during 1997 to 1999 after being bitten by an animal; the data came from the department's computer database, which records information on all new admissions.

We calculated the total number of patients in each calendar month and then distributed this number according to the days of the lunar months. We then compared the total numbers of patients on each day of each lunar month. All human and insect bites were excluded from our study.

According to the definition of a full moon (the middle day in the 29.531-day lunar cycle) (see also box), we divided the lunar month into 10 periods, with the first nine periods having three days and the last one having two (see table). The model we used in our statistical analysis accommodated this difference in days.

Lunar definitions

Full moon

The phase of the moon in which it is fully illuminated as seen from the earth. It is defined as three day periods in the 29.531-day lunar cycle, with the middle day generally described as the day of the full moon.

Lunation

The time between two successive new moons. This varies, but the approximate time is 29.530589 days (synodic period of the moon).

New moon

The phase of the moon when it is first visible as seen from the earth.

Blue moon

Sometimes a full moon will occur twice in a month. The second full moon in that month is called a blue moon.

Data were then analysed by using Stata (release 6.0) software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). We used a Poisson log linear model, with period of the moon as a categorical independent variable, and modelled the number of bites on this single factor. Cumulative incidence (number of patients reporting bites) for the 10 periods and also for each lunar day, was then analysed. Significance was set at a P value of <0.05.

Results

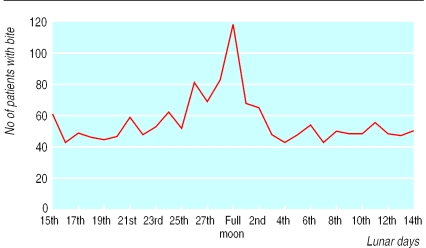

There were 37 full moon days and one blue moon day (see box) from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 1999. In all, 1621 new patients had been bitten by animals (56 cat bites (3.4%), 11 rat bites (0.7%), 13 horse bites (0.8%), and 1541 dog bites (95.1%)). The highest numbers of bites were on or around full moon days (table and fig 1).

Figure 1.

Number of animal bites according to day of lunar month

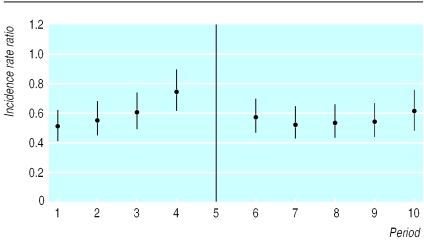

The incidence of animal bites in period 5 (time of full moon) was significantly higher than the incidence in the other periods in the lunar cycle (P<0.001; P=0.002 for period 4) (fig 2). When we excluded period 5, the incidence of bites in period 4 was also significantly higher than the incidence in all other periods except period 10. The rise in incidence seemed to accelerate therefore a few days before a full moon, peaking sharply on the day of the full moon before falling away rapidly to rate that was about half the rate at full moon.

Figure 2.

Incidence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of number of animal bites relative to number occurring at full moon

Discussion

In our study we showed that an association exists between the lunar cycles and changes in animal behaviour and that animals' propensity to bite humans accelerates sharply at the time of a full moon. Further experiments are needed to verify our hypothesis. Few other studies have correlated the influence of the full moon with behaviour of animals or insects. One article has suggested that the predatory activity of mites is significantly depressed during a full moon.12

The moon, ever present, will continue to influence different aspects of nature and humans. More studies are therefore needed to explore lunar effects on animals, especially their propensity to bite humans.

What is already known on this topic

Human behaviour is altered during the full moon period

No study has significantly correlated the effects of a full moon with the propensity of animals to bite

What this study adds

Animals have an increased propensity to bite humans during the full moon periods

Supplementary Material

Table.

Number of bites among new patients attending accident and emergency department, according to 10 periods of the lunar cycle

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lunar days | 16, 17, 18 | 19, 20, 21 | 22, 23, 24 | 25, 26, 27 | 28, full moon, 1 | 2, 3, 4 | 5, 6, 7 | 8, 9, 10 | 11, 12, 13 | 14, 15 |

| No of bites | 137 | 150 | 163 | 201 | 269 | 155 | 142 | 146 | 148 | 110 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Rita Stocks, assistant manager in the patient administration department at the Bradford Royal Infirmary, for providing valuable data from the computer.

Footnotes

Funding: No special funding

Competing interests: None declared.

A table showing the data supporting figure 2 is available on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Raison CL, Klin HM, Steckler M. The moon and madness reconsidered. J Affect Disord. 1999;53:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur CP, Sharma D. Full moon and crime. BMJ. 1984;289:1789–1791. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6460.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soyman P, Holdstock TL. The influence of the sun, moon, climate and economic conditions on crisis incidence. J Clin Psychol. 1980;36:884–893. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198010)36:4<884::aid-jclp2270360408>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sitar J. Chronobiology of human aggression. Cas Lek Cesk. 1997;136:174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghiandoni G, Secli R, Rocchi MB, Ugolini G. Incidence of lunar position in the distribution of deliveries. A statistical analysis. Minerva Ginecol. 1997;49:91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sitar J. The effect of the semilunar phase on an increase in traffic accidents. Cas Lek Cesk. 1994;133:596–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, Tennant C. Lunar cycles and violent behaviour. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;23:496–499. doi: 10.3109/00048679809068322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeCastro JM, Pearcey SM. Lunar rhythms of the meal and alcohol intake of humans. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:439–444. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00232-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharfman M. Drug overdose and the full moon. Percept Mot Skills. 1980;50:124–126. doi: 10.2466/pms.1980.50.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laverty WH, Kelly IW. Cyclical calendar and lunar patterns in automobile property accidents and injury accidents. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;86:299–302. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.86.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson DA, Adams SL. The full moon and ED patient volumes: unearthing a myth. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:161–164. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikulecky M, Zemek R. Does the moon influence the predatory activity of mites? Experientia. 1992;48:530–532. doi: 10.1007/BF01928182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.