Introductory paragraph

Organisms respond to changes in their environment, and many such responses are initiated at the level of gene transcription. Here, we provide evidence for a previously undiscovered mechanism for directing transcriptional regulators to new binding targets in response to an environmental change. We show that Rap1, a master regulator of yeast metabolism, binds to an expanded target set upon nutrient depletion despite decreasing protein levels and no evidence of posttranslational modification. Computational analysis predicted that proteins capable of recruiting the chromatin regulator Tup1 acted to restrict the binding distribution of Rap1 in the presence of nutrients. Deletions of TUP1, genes that encode recruiters of Tup1, or chromatin regulators recruited by Tup1, cause Rap1 to bind specifically and inappropriately to low-nutrient targets. These data, combined with whole-genome measurements of nucleosome occupancy and Tup1 distribution, provide evidence for a mechanism of dynamic target specification that coordinates the genome-wide distribution of intermediate-affinity DNA sequence motifs with chromatin-mediated regulation of accessibility to those sites.

Main Text

To survive in fluctuating environments, organisms must respond to changes in their surroundings. One of the primary means of response at the cellular level is the adjustment of levels of gene transcription1. In some cases, new transcriptional programs are established by the binding of regulatory proteins to new gene targets under a given environmental condition2. These regulatory factors then act to either activate or repress transcription. Four straightforward mechanisms for the regulation of transcription-factor targeting have been demonstrated. These include altering the regulatory factor's concentration in the nucleus3, altering binding affinity by post-translational modification4 or through an allosteric cofactor5, and altering binding properties by expression of a protein cofactor6. Here, we present experiments that provide evidence for a new mechanism of dynamic transcription factor target specification. In the proposed mechanism, the genome-wide distribution of DNA sequence motifs for which a factor has intermediate affinity is carefully coordinated with chromatin-mediated regulation of accessibility to those sites. In this way, rather than through use of a specific cofactor or post-translational modification, the genome itself is remodeled to change the targeting and biological outcome of an unaltered transcription factor.

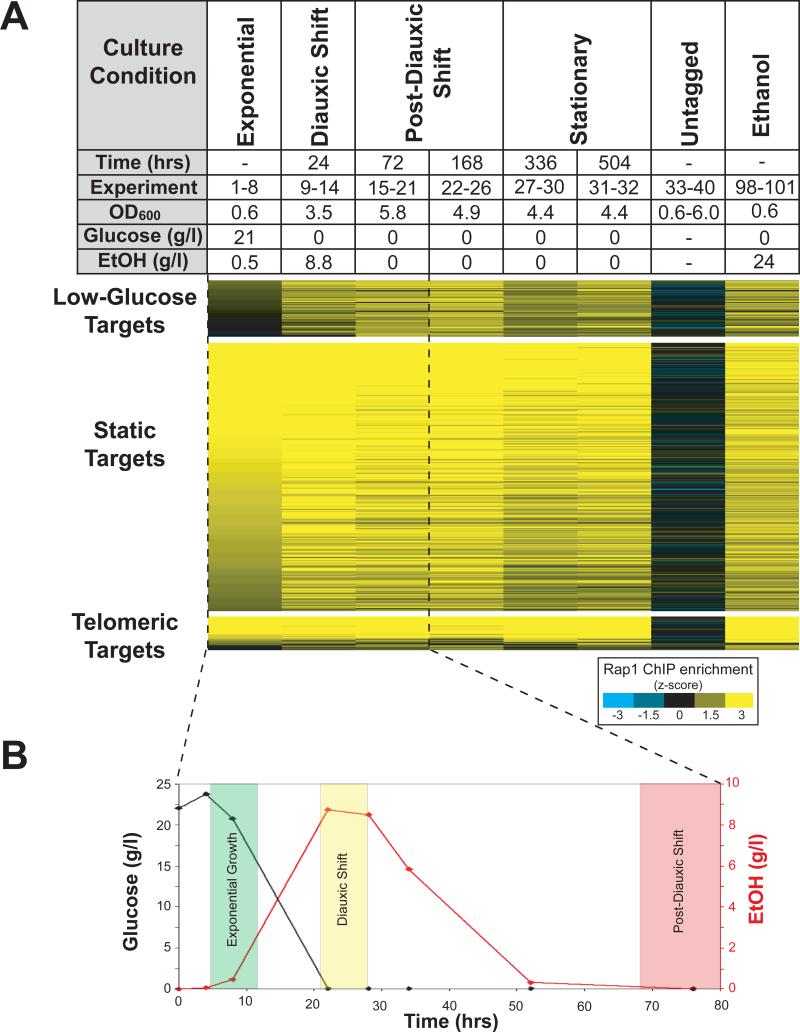

Rap1 (Repressor-Activator Protein 1) directs a transcriptional program that is central to yeast metabolism, activating the transcription of genes encoding the ribosomal protein subunits and glycolytic enzymes7-9. Nearly 40% of the mRNA initiation events in mitotically growing yeast are activated by Rap1, yet Rap1 is also required for the repression of these same genes in response to nutrient depletion10. Because of its central role in the cellular economy, we asked whether Rap1 was targeted to new genomic loci upon a change in the nutrient environment. The genome-wide localization of Rap1 was monitored as yeast consumed and ultimately depleted their carbon sources (Figure 1). We found that despite a decrease in Rap1 protein level (Figure S1) and no evidence of posttranslational modification11,12, Rap1 bound to an expanded target set. Fifty-two targets specific to low-glucose growth conditions were identified (hereafter “low-glucose targets”), while no targets specific to high-glucose growth were found. A representative subset of low-glucose targets was verified by ChIP-PCR (Figures S2 and S3).

Figure 1. Rap1 binds to new targets in the absence of glucose.

A) Rap1 ChIPs (Methods) were performed at the time points shown. For each time point, elapsed time, microarray experiment number (Table S1), optical density at 600 nm, concentration of glucose in the media, and concentration of ethanol in the media is indicated. In experiments 1-40, media initially contained 2% glucose as the sole carbon source. The enrichment, by z-score, of genomic regions by Rap1 ChIP is indicated by color (scalebar, lower right). Enriched loci were grouped into three categories: telomeric targets, static targets, and low-glucose targets (Methods). The 262 static targets were bound at all time points. Telomeric targets are located within 10 kb of a telomere. The 52 low-glucose targets were bound by Rap1 only after depletion of glucose, and include the promoters of genes involved in alternative carbon source utilization, stationary-phase survival, and other nutrient utilization pathways (Figure S5). To show that carbon source controls the observed redistribution of Rap1, we performed Rap1 ChIPs from cells that were grown in media identical to that used in experiments 1-40, except that 2.4% ethanol was provided as a carbon source (experiments 98-101, rightmost column). B) After 24 hours in culture, glucose was depleted completely and ethanol levels peaked at 8.8 g/l. After 72 hours, all ethanol in the media had been consumed. The shaded regions show when samples were ChIPed.

A transcription factor's target set could be expanded despite decreasing protein concentration if most potential binding sites were blocked during growth in glucose, but then in the absence of glucose, a subset of those sites were made available. In the case of Rap1, we reasoned that proteins involved directly in such a mechanism would have a genomic distribution in the presence of glucose that closely matched the Rap1 targets bound only in the absence of glucose. We identified eight such proteins using a computational approach (Methods and Figure S4), four of which (Sut1, Mig1, Nrg1, and Sko1) had been previously characterized to interact physically with the Tup1-Ssn6 repressor complex13,14. Identification of Tup1 itself through our screen was not possible because the genome-wide localization of Tup1 had not been reported. Tup1 is a well-characterized repressor that does not bind DNA directly15, but is instead recruited to specific loci by other sequence-specific factors. Mig1, Nrg1, and Sko1 recruit Tup1 to the promoters of glucose-repressed genes, starch degrading genes, and osmotic stress inducible genes respectively16-18. We hypothesized that Tup1 and its recruiters negatively regulate Rap1 binding to low-glucose targets.

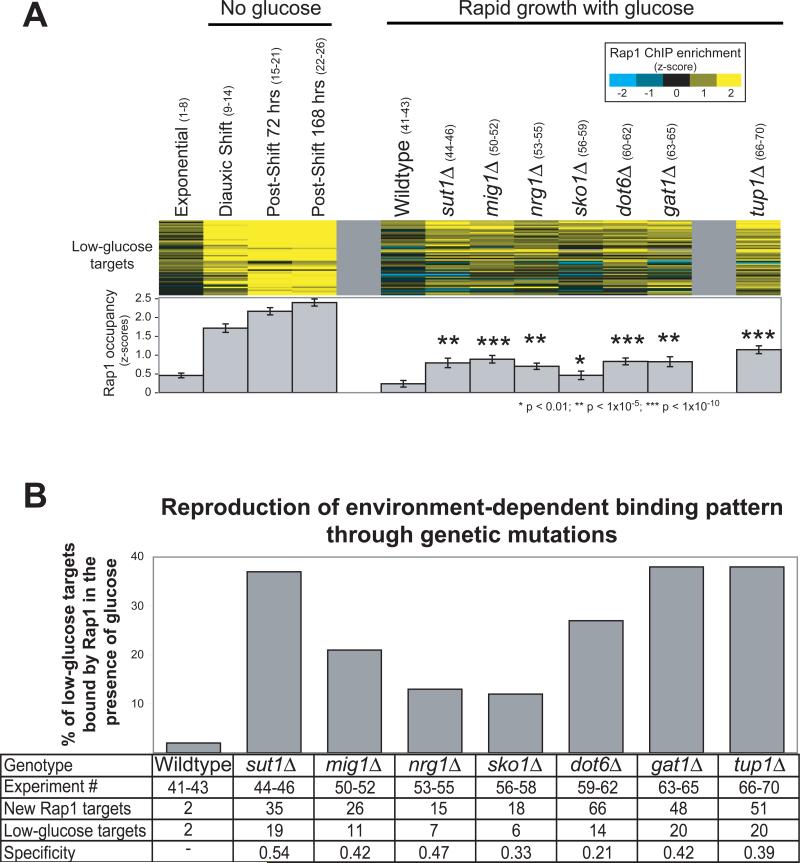

This predicts that in cells lacking Tup1 or its recruiters, Rap1 would bind inappropriately to low-glucose targets, even in the presence of glucose. We determined the genomic distribution of Rap1 in strains grown in high-glucose media, but lacking the genes encoding Tup1 or its recruiters. Compared to wild-type cells, all deletion strains exhibited a specific and significant increase in Rap1 occupancy at low-glucose targets, with deletions of the TUP1 gene itself showing the strongest effect (Figure 2A). Accordingly, many low-glucose targets were considered “bound” by Rap1 in the deletion strains (p-value cutoff of 0.005, Figure 2B). Recapitulation of a low-glucose Rap1 binding pattern through mutations in genes encoding Tup1 and its recruiters shows that these proteins are normally required to prevent the binding of Rap1 to low-glucose targets in a high-glucose environment.

Figure 2. In the absence of Tup1 or proteins that recruit Tup1, Rap1 binds specifically and inappropriately to low-nutrient targets.

A) Rap1 occupancy determined by ChIP is shown at the 52 low-glucose targets in the indicated mutant strains (z-scores for enrichment, scalebar upper right). Experiments 1-26 (shown in parentheses, detailed in Table S1) measure Rap1 occupancy over a timecourse as glucose is depleted from the media. Experiments 41-46 and 50-70 measure Rap1 occupancy at a single timepoint in the indicated strain during exponential growth in the presence of glucose. Enrichment in each deletion strain was compared to wildtype by t-test. B) For each strain the targets bound by Rap1 were determined by ChIPOTle35 (Methods). The percentage of low-glucose targets bound inappropriately by Rap1 is plotted. Error bars are not appropriate here because the percentage of targets bound is determined using all experimental replicates and takes measurement variability into account. Indicated at the bottom is the experiment number, the total number of new Rap1 targets observed relative to wild-type, the number of those new targets that were also low-glucose targets, and a statistic termed “specificity”, calculated as: (low-glucose targets / total new targets).

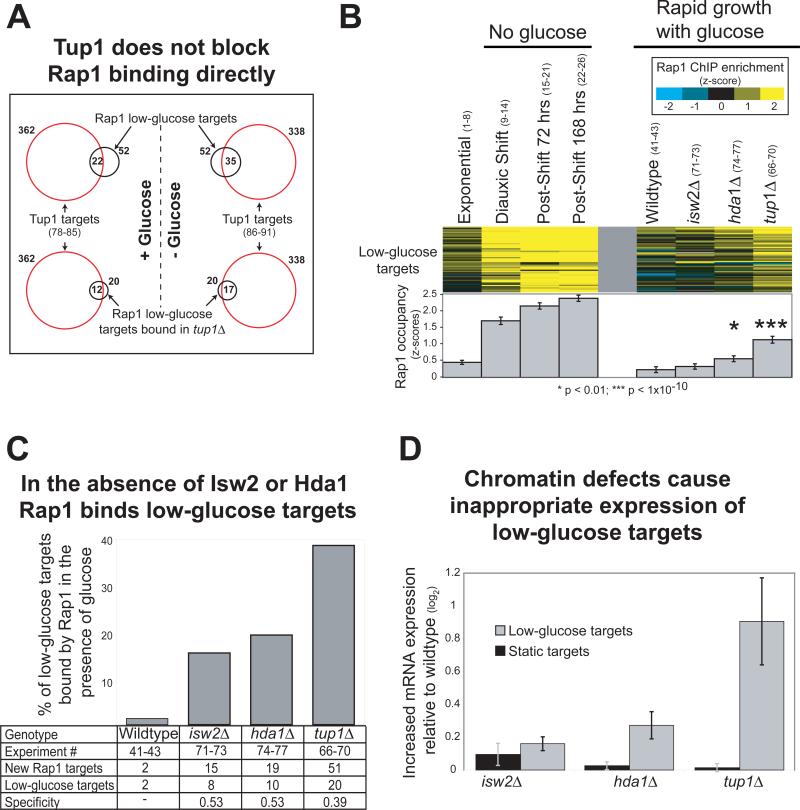

To further characterize the role of Tup1 in restricting the binding distribution of Rap1, we determined the genomic localization of Tup1 during exponential growth in the presence of glucose. We found that the majority of the low-glucose Rap1 sites that were inappropriately bound in tup1Δ strains were occupied by Tup1 in a wildtype strain. This provides evidence that inappropriate Rap1 binding in tup1Δ strains was caused directly by the absence of Tup1 at the affected loci (Figure 3A). If Tup1 blocked Rap1 binding directly, Tup1 would be predicted to vacate low-glucose Rap1 targets upon glucose depletion. To test this, we determined the genomic distribution of Tup1 after glucose depletion. Contrary to the prediction, low-glucose Rap1 targets bound by Tup1 in the presence of glucose remained bound after glucose was depleted. In fact, more low-glucose Rap1 targets were bound by Tup1 in low-glucose conditions (Figure 3A). Therefore, Tup1 itself does not block Rap1 binding directly.

Figure 3. Tup1 restricts Rap1 binding through chromatin-modifying co-factors.

A) Genomic loci bound by Tup1 in wildtype cells (red circles) as determined by ChIP-chip (p<0.005, Methods) during growth in the presence of glucose (left) and after glucose had been depleted from the media (right). Rap1 low-glucose targets are indicated by black circles (upper) and the subset of those targets also bound inappropriately in a tup1Δ strain is shown in the lower panel. Tup1 targets indicated in the lower panel are identical to those in the upper panels, and are reproduced for comparison to the respective Rap1 targets. B) Rap1 occupancy in strains lacking the Tup1-associated chromatin modifying proteins Isw2 and Hda1, as determined by ChIP-chip during exponential growth in the presence of glucose (see Figure 2A for details). C) Same as Figure 2B, but for the strains indicated. D) The average mRNA expression change23,28 (deletion over wildtype) of the genes downstream of 23 low-glucose Rap1 targets and 223 static targets. To avoid ambiguity regarding which gene might be regulated by Rap1, only genes downstream of unidirectional promoters are plotted.

Tup1 is known to alter local chromatin structure by interacting with chromatin-modifying proteins19-21, including Hda122. Hda1 is a class 2 histone deacetylase required for repression of a subset of Tup1-repressed genes23. To determine whether recruitment of Hda1 is required for Tup1's role in restricting Rap1 targets, we tested Rap1 localization in an hda1Δ strain. Rap1 occupancy of low-glucose targets was significantly higher in the absence of hda1, mimicking a low-glucose binding response (Figure 3B-C). Tup1 also interacts with Isw2, a member of the imitation-switch (ISWI) class of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes24-27. Rap1 occupancy at low-glucose targets was also increased in isw2Δ strains, but to a lesser degree than was observed for hda1Δ (Figure 3B-C).

To corroborate these results, we used existing data23,28 to ask if the mRNA expression of low-glucose targets was affected in tup1Δ, isw2Δ, or hda1Δ strains. Expression of low-glucose targets was increased in tup1Δ and hda1Δ, but not in isw2Δ strains, whereas the expression of static targets was unaffected by these mutations (Figure 3D). These results are concordant with the observed changes in Rap1 binding in the respective mutants, and demonstrate a downstream consequence on gene regulation for mis-targeting of Rap1. These results also indicate that at many loci, Hda1 is required for Tup1's ability to block Rap1 binding and repress transcription in the presence of glucose.

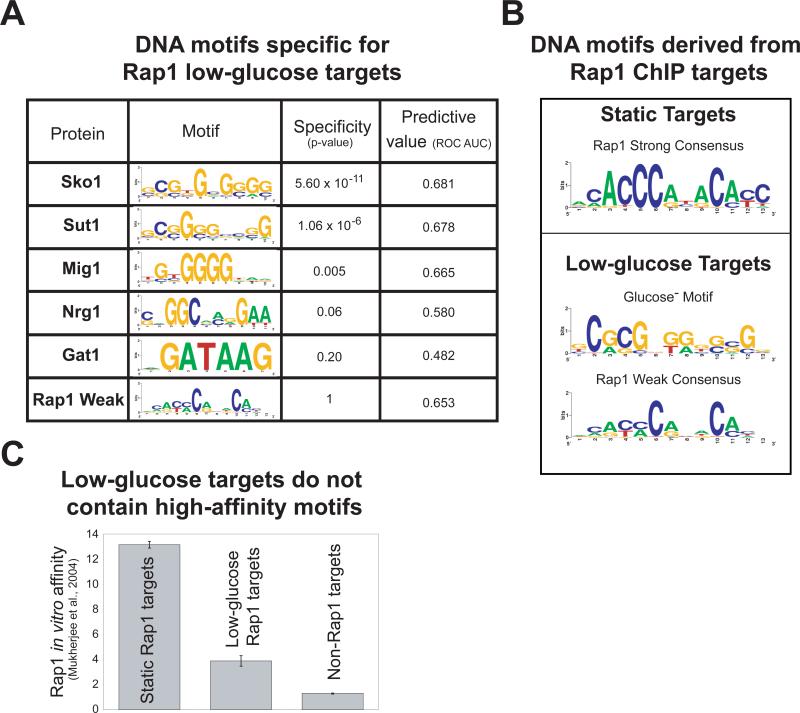

The data predict that motifs for Rap1 and for recruiters of Tup1 occur in the promoters of low-glucose Rap1 targets. Sko1, Sut1, and Mig1 motifs are indeed specific (p < 0.05) for low-glucose targets. Furthermore, the Sko1, Sut1, Mig1, Nrg1 and Rap1 motifs all provide information that distinguishes low-glucose targets from all other genomic loci (Figure 4A). More intriguing were the differences in the types of Rap1 motif found in static versus low-glucose Rap1 targets. For the static targets, a strongly stereotypic consensus motif that matched the previously characterized Rap1 binding site9 was discovered (“Rap1 strong”, Figure 4B). In contrast, 90% of the low-glucose targets contained a degenerate Rap1 motif of lower predicted affinity (“Rap1 weak”, Figure 4B). We confirmed the lower affinity of Rap1 for conditional promoters by analysis of existing protein binding microarray data29 (Figure 4C). Therefore, low-glucose targets are distinguished from constitutive targets by harboring binding sites for recruiters of Tup1 and intermediate-affinity Rap1 binding sites.

Figure 4. Low-glucose Rap1 targets contain Sko1, Sut1, or Mig1 binding sites and a weak Rap1 consensus motif.

A) The specificity of sequence motifs for low-glucose versus static targets was determined using ROVER41 with a site p-value cutoff of 0.001. The value of each motif in predicting Rap1 binding was determined using the area under (AUC) the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) plot42, with each promoter represented by the motif score generated by the MatrixScan module of BioProspector37. Motif scores encapsulate the similarity of DNA sequences at each locus to the specified position weight matrix (PWM). ROC plots show how low-glucose targets (true positives) were captured in relation to non-low-glucose targets (false positives) for a given motif score. A motif that had no predictive value would have an AUC of about 0.5; higher values are better (maximum = 1). B) Overrepresented DNA sequence motifs for static and low-glucose Rap1 targets were determined using MDscan and BioProspector37,38. The motif found for the static targets is the archetypical Rap1 binding motif. The most significant motif discovered for the low-glucose targets is very similar to the Sut1 binding motif2. We identified the Rap1-weak motif through a directed search using a degenerate Rap1-Strong PWM (methods). All PWMs are displayed as sequence logos40. C) Rap1 in vitro binding affinity for low-glucose-, static-, and non-Rap1 targets was enumerated using published protein binding microarray data29. “Protein binding microarray” is a technique that determines a protein's in vitro DNA-binding specificity for a set of arrayed loci or DNA sequences.

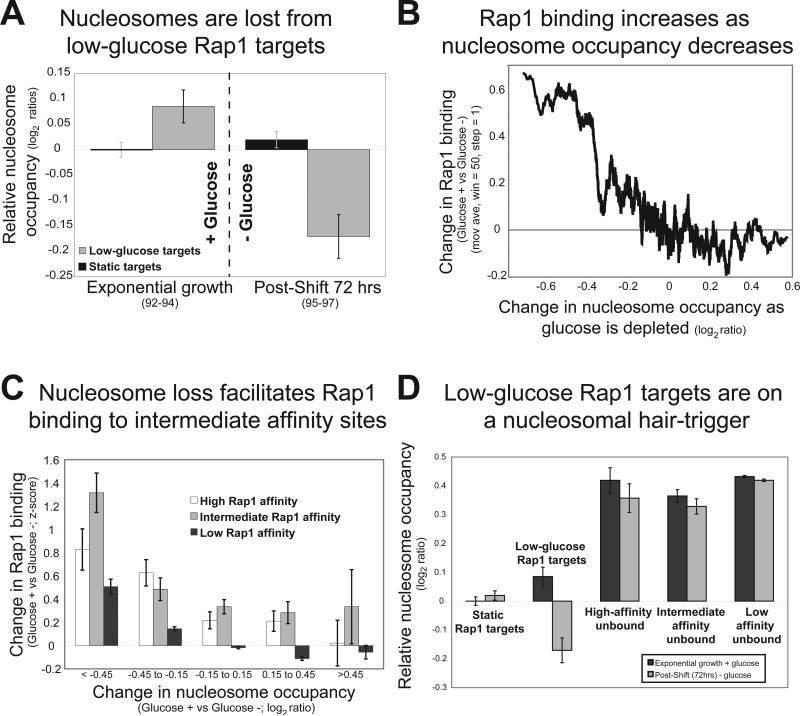

The results above demonstrate the role of the Tup1 in restricting Rap1 binding and show that the histone deacetylase Hda1 is required to maintain a high-fidelity Rap1 binding pattern. We hypothesized that Tup1 and Hda1 could block Rap1 binding at low-glucose targets by stabilizing one or more nucleosomes in the presence of glucose. We therefore determined genome-wide nucleosome occupancy in the presence of glucose and after glucose had been depleted from the media. In glucose, nucleosome occupancy is higher at low-glucose targets than it is at loci constitutively bound by Rap1 (Figure 5A). However, upon glucose depletion, the promoters of low-glucose targets exhibit a sharp nucleosome loss, which results in lower nucleosome occupancy than even the static targets (Figure 5A). We next explored the relationship between Rap1 binding and nucleosome occupancy. If nucleosome occupancy facilitates Rap1 binding to intermediate affinity sites, we would expect Rap1 binding to increase as a function of nucleosome loss at those sites. We found that Rap1 occupancy increases as nucleosomes are lost (Figure 5B). More telling, the loss is predicted to occur specifically at a subset of intermediate-affinity sites, as opposed to other high-affinity or low-affinity sites throughout the genome. Even though nucleosome loss does occur at other sites throughout the genome, the intermediate-affinity sites are most sensitive to these changes in terms of Rap1 binding (Figure 5C-D). These results strongly suggest a causal role for nucleosome loss in facilitating Rap1 binding to intermediate-affinity loci in low-glucose conditions.

Figure 5. Loss of nucleosomes allows Rap1 to bind to intermediate-affinity targets.

A) Nucleosome occupancy was determined by ChIP-chip with an anti-Histone H3 antibody during exponential growth in the presence of glucose (left) and after glucose had been depleted from the media (right). Nucleosome occupancy is plotted relative to static targets during exponential growth. Error bars indicate the standard error. During growth in the presence of glucose, unbound low-glucose targets have a higher nucleosome occupancy then bound-static targets (p = 0.073). In the absence of glucose, both groups of targets are bound by Rap1, but low-glucose sites have significantly lower (p < 5 × 10−5) nucleosome occupancy than static targets. Experiment numbers are indicated in parentheses. B) Loci were sorted by their change in nucleosome occupancy upon glucose depletion. A moving average of the change in Rap1 occupancy upon glucose depletion is plotted on the y-axis. C) Intergenic regions were grouped into three categories based on their Rap1 binding affinity (high, intermediate, or low affinity) as measured by PBM29. The 306 high-affinity regions had PBM p-values less than 1 × 10−6, the 288 intermediate affinity regions had PBM p-values between 0.01 and 1 × 10−6, and the remaining 4945 sites were classified as low-affinity. The average change in Rap1 occupancy (x axis) was determined for each group as a function of the change in nucleosome occupancy (y axis). D) Low-glucose Rap1 targets are on a nucleosomal hair-trigger. Nucleosome occupancy in the presence (black) and absence (gray) of glucose is plotted for all yeast intergenic regions. Values are relative to static Rap1 targets in the presence of glucose. Intergenic regions were separated into five groups: static Rap1 targets, low-glucose Rap1 targets, unbound loci containing high-affinity Rap1 sites, unbound loci containing intermediate-affinity Rap1 sites and unbound loci containing low-affinity Rap1 sites.

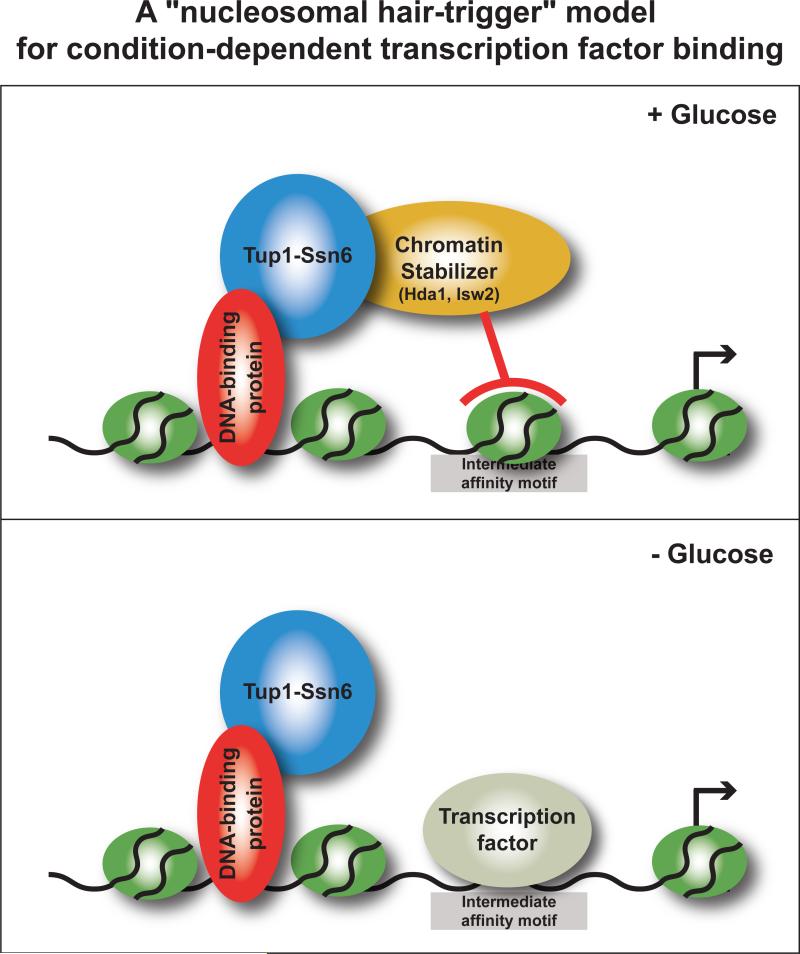

We propose a mechanism in which transcription factor binding is blocked at condition-specific targets by stabilizing nucleosomes at intermediate-affinity transcription factor binding sites (Figure 6). In our experimental system, we have identified several key players and steps in this mechanism. Sequence-specific DNA binding proteins recruit Tup1 to specific loci, which in turn serves to recruit the activities of the histone deacetylase Hda1 and the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler Isw2 to low-glucose targets. Our model proposes that in the presence of glucose, the activities of Hda1 and perhaps Isw2 stabilize a nucleosome to block an intermediate-affinity Rap1 binding site. In the absence of glucose, repression is relieved as a consequence of nucleosome release at the conditional promoters. Rap1 binds and remains bound to static sites through a combination of inherently low nucleosome occupancy and high Rap1 in vitro binding affinity, while selected intermediate-affinity sites are situated on a nucleosomal hair-trigger that allows conditional binding through elevated sensitivity to changes in nucleosome occupancy. This mechanism and the experiments performed here account for about half of the new targets bound by Rap1 upon glucose depletion, so it is likely that other mechanisms that influence environment-dependent target selection in this system await discovery.

Figure 6. A “nucleosomal hair-trigger” model for condition-dependent transcription factor binding through coordinated interplay between local chromatin structure and DNA-binding affinity.

See text for details. Note that rather than the typical case of chromatin remodeling proteins acting to remove a nucleosome to effect activation, in this mechanism the enzymes act to position nucleosomes into a repressive configuration. Therefore, the default state of this system is factor binding and gene activation.

METHODS

Growth conditions

Overnight cultures were diluted to OD600 0.1 in YPD media (2% glucose), and grown at 30°C to OD600 0.6-0.8 for “exponential“ samples. Samples were also taken after 24 hrs, 72 hrs, 168 hrs, 336 hrs, and 504 hrs. Samples for all deletion experiments were taken at OD600 0.6-0.8 in YPD (2% glucose). Mock experiments were performed using wildtype BY4741 without any tagged proteins. D-Glucose and ethanol levels were determined according to the manufacturer‘s instructions (Roche D-Glucose Cat. # 0716251, Ethanol Cat # 10176290035) for two independent replicates at 3 hr intervals for the first 12 hours, then three samples per day for three days, and then one sample a day.

ChIP-chip experiments and microarray hybridization

ChIP-chip experiments were performed as previously described9,30,31 using strains harboring TAP-tagged alleles of Rap1, Tup1, and Sut1 in a wild-type BY4741 background (Table S1). Briefly, whole-cell extracts for Rap1 tap-tagged proteins were prepared from 1% formaldehyde-fixed cells using lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 300 nM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1.0% Triton-X, 0.1 % Sodium deoxycholate, and 1 X protease inhibitors (Calbiochem)). Isolated chromatin was sheared to an average size of 0.8 kb. DNA fragments associated with Rap1-TAP were isolated by affinity purification using IgG sepharose in IPP150 (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP40), rocked overnight at 4°C, washed three times with IPP150 and once with TEV cleavage buffer (10mM Tris-Cl ph 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 1mM DTT). The TAP-tag was cleaved away from the IgG beads with 20 units TEV at 16°C for 2 hrs. After cross-link reversal at 65°C overnight, protein was degraded with Proteinase K, and DNA was isolated using Zymo columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (Zymo Research). For the Tup1-Tap and Sut1-Tap ChIPs the affinity purification protocol was preformed without TEV cleavage. The TEV cleavage step was replaced with eight wash steps: two washes at room temperature with lysis buffer, two washes with 50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 500mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1.0% Triton-X, and 0.1% Sodium deoxycholate, two washes with 10mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.25 mM LiCl, 2mM EDTA, 1.0% Triton-X, 0.1% Sodium deoxycholate, and two washes with TE. DNA was eluted with 50mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS. For ChIPs comparing wild-type and mutant extracts (Figures 2 and 3), BY4741 or BY4741 strains harboring deletions from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project32,33 (Open Biosystems) were used, along with antibodies raised to Rap1 amino acids 528-827 (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Rap1 Y-300: sc-20167). Rap1 ChIP was performed with identical antibodies for all comparisons between wild-type and deletion strains (Figures 2 and 3). Histone H3 ChIPs were preformed exactly as previously described34. ChIP-enriched and input DNA was amplified9, and competitively hybridized to PCR-based whole-genome DNA microarray covering all coding and noncoding regions at approximately 800 bp resolution. The arrays were scanned with an Axon 4000 scanner, and data were extracted using Genepix 5.0 software. Only spots of high quality by visual inspection, with less than 10% saturated input pixels and a signal intensity of greater than 500 (background-corrected sum of medians for both channels) were used for the analysis. All raw data is available through GEO (accession numbers pending).

Signal processing and target calling

ChIP-chip data were normalized by array median centering and standardized by the total array standard deviation30. The median standardized value was determined across all biological replicates. The standardized log ratio was used as input for ChIPOTle (V1.01) with the following parameters: Gaussian background distribution, step-size 0.25 kb, and window size 1 kb35. Standardized log ratios were converted to z-scores by centering and scaling. The peaks of Rap1 binding were categorized into three groups: i) “telomeric”, any peak (p < 10−8) in at least one time point located within 10-kb of the chromosome ends, ii) “static”, any peak (p < 10−8) in at least one time point AND p < 0.01 for all time points and iii) “low-glucose” any peak (p <0.001) in two consecutive low-glucose time-points (those spanning 24-504 hours) AND not bound during exponential growth (p < 0.05) in the experiments reported here AND not bound during exponential growth (p < 0.05) using previously published data9.

Computational screen for effector molecules

Two computational screens were performed to determine which variables best separate low-glucose Rap1 targets from static Rap1 targets and unbound sites (Figure S4). In screen 1, individual variables best separating low-glucose from static targets were identified using discriminant analysis with stepwise variable selection (SAS version 9.1). The genomic dataset analyzed contained published ChIP-chip data for 205 transcription factors, protein-binding microarray data, nucleosome occupancy, histone methylation, and GC content2,29,34,36. Screen 2 was preformed as above, except variables that best separate low-glucose from both static Rap1 targets and all unbound sites were identified. The importance of the selected variables were judged by their Wilks’ Lambda statistic and their Pearson-correlation coefficient to the two classifiers (screen 1 or 2).

Motif determination

Overrepresented sequence motifs were identified for low-glucose and static Rap1 targets using MDscan and BioProspector37,38. For these and previously known motifs, each Rap1 target was scanned using the MatrixScan module from BioProspector with a third-order Markov background model at a threshold of 0.0001. For low-glucose targets, the “Rap1-weak” motif was identified using the position weight matrix (PWM) discovered with the static targets (Rap1-Strong) at a permissive threshold of 0.0005. All discovered motifs were aligned to generate the Rap1-Weak PWM. Previously published PWMs were used for Sko139, Mig129, Sut1, Nrg1, and Gat12. PWMs were visualized using WebLogo40. The overabundance of the each motif in low-glucose relative to static targets was determined using ROVER (Relative OVER-abundance of cis-elements) with a site p-value cutoff of 0.00141.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Rap1 protein and mRNA levels decrease as glucose is depleted. A) 20 μg of whole-cell extract was separated by a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and probed with anti-Rap1 antibody. B) mRNA levels for Rap1, as measured by microarray43, decrease upon diauxic shift.

Supplemental Figure 2. Confirmation of ChIP-chip results. A. Representative agarose gel image of ChIP-PCR results, showing results from two genomic regions upstream of ENB1 and VHS1. ChIP (IP) samples are loaded next to their corresponding input (IN). The top band in every lane is the test fragment, and the bottom band is specific to a control (YHR131C). B. The average ratio (IP/Input) for Rap1 IPs, during exponential growth, after depletion of glucose (72 hrs), and in a tup1Δ background, is plotted with their standard error at 11 loci. The ratio for any site is determined by the (intensity of the test fragment in IP / intensity of the control fragment in IP) / (intensity of the test fragment in input / intensity of the control fragment in input) C. The average ratio (IP/Input) for Tup1 IPs is plotted with their standard error at 11 loci. D. Two biological replicates of Rap1 ChIPs after glucose depletion (72 hrs) were hybridized directly on the same microarray with Rap1 ChIPs from cells grown in high glucose. The average ratios reported from probes representing the 52 low-glucose Rap1 targets, 262 static Rap1 targets, and telomeric targets is plotted, along with their standard errors.

Supplemental Figure 3. Confirmation of ChIP-chip results at the SGA1 locus.

A. The open reading frames for SGA1 and FMC1 are shown. An upstream dubious open reading frame is shaded grey. Arrows indicate direction of transcription. The regions tested by ChIP-PCR (A-D) and the elements on the microarray (1-7) are shown below. B. Rap1 IPs during exponential growth (+ glucose) as measured by the microarray (top; 8 replicates) and PCR (bottom; 4 replicates). C. Rap1 IPs in low glucose (72 hrs) as measured by the microarray (top; 7 replicates) and PCR (bottom; 4 replicates). D. Tup1 IPs during exponential growth (+ glucose) as measured by microarray (top; 8 replicate) and PCR (bottom; 3 replicates). E. The enrichment at microarray element 4 is shown for the entire timecourse. F. A representative gel image for one replicate at each PCR region. IP (IP) samples are loaded next to their corresponding input (IN). The top band in every lane is the test fragment, which is compared to the bottom control band (YHR131C).

Supplemental Figure 4. Computational screens predict the involvement of Tup1-Ssn6 proteins in blocking Rap1p binding. A. Schematic representation of two computational screens for effector of Rap1 conditional binding. Screen 1 compares low-glucose targets versus static targets and screen 2 compares low-glucose targets versus all yeast intergenic regions. B. Results for the two computational screens listed by Pearson correlation (r) to the classifier variable. The p-value was estimated by 10,000 permutations. The GO biological process is listed for each protein (lower row).

Supplemental Figure 5. Rap1 binding and glycolysis

A) Rap1 binds upstream of at least one enzyme involved in each of the eleven steps required to metabolize glucose into ethanol. Static Rap1 targets are shown in red and low-glucose targets are in blue. Arrows indicate the flow of substrate. B) During growth in low-glucose, Rap1 binds upstream of genes involved in alternative carbon-source utilization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacob F, Monod J. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:318–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbison CT, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill EM, Kaffman A, Jolly ER, O'Shea EK. Regulation of PHO4 nuclear localization by the PHO80-PHO85 cyclin-CDK complex. Science. 1996;271:209–12. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu W, Roeder RG. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell. 1997;90:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zubay G, Schwartz D, Beckwith J. Mechanism of activation of catabolite-sensitive genes: a positive control system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;66:104–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitlinger J, et al. Program-specific distribution of a transcription factor dependent on partner transcription factor and MAPK signaling. Cell. 2003;113:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shore D. RAP1: a protean regulator in yeast. Trends Genet. 1994;10:408–12. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morse RH. RAP, RAP, open up! New wrinkles for RAP1 in yeast. Trends Genet. 2000;16:51–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieb JD, Liu X, Botstein D, Brown PO. Promoter-specific binding of Rap1 revealed by genome-wide maps of protein-DNA association. Nat Genet. 2001;28:327–34. doi: 10.1038/ng569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuta K, Tsujii R, Warner JR, Nishiyama M. The C-terminal silencing domain of Rap1p is essential for the repression of ribosomal protein genes in response to a defect in the secretory pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1063–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu H, et al. Analysis of yeast protein kinases using protein chips. Nat Genet. 2000;26:283–9. doi: 10.1038/81576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkworth RI, Munn AL, Kobe B. Protein kinases associated with the yeast phosphoproteome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RL, Johnson AD. Turning genes off by Ssn6-Tup1: a conserved system of transcriptional repression in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:325–30. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regnacq M, Alimardani P, El Moudni B, Berges T. SUT1p interaction with Cyc8p(Ssn6p) relieves hypoxic genes from Cyc8p-Tup1p repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1085–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzamarias D, Struhl K. Functional dissection of the yeast Cyc8-Tup1 transcriptional co-repressor complex. Nature. 1994;369:758–61. doi: 10.1038/369758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proft M, Serrano R. Repressors and upstream repressing sequences of the stress-regulated ENA1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: bZIP protein Sko1p confers HOG-dependent osmotic regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:537–46. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vit MJ, Waddle JA, Johnston M. Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1603–18. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SH, Koh SS, Chun JH, Hwang HJ, Kang HS. Nrg1 is a transcriptional repressor for glucose repression of STA1 gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2044–50. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davie JK, Edmondson DG, Coco CB, Dent SY. Tup1-Ssn6 interacts with multiple class I histone deacetylases in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50158–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson AD, et al. Ssn6-Tup1 interacts with class I histone deacetylases required for repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2737–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.829100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edmondson DG, Smith MM, Roth SY. Repression domain of the yeast global repressor Tup1 interacts directly with histones H3 and H4. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1247–59. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J, Suka N, Carlson M, Grunstein M. TUP1 utilizes histone H3/H2B-specific HDA1 deacetylase to repress gene activity in yeast. Mol Cell. 2001;7:117–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green SR, Johnson AD. Promoter-dependent roles for the Srb10 cyclin-dependent kinase and the Hda1 deacetylase in Tup1-mediated repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4191–202. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Reese JC. Ssn6-Tup1 requires the ISW2 complex to position nucleosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J. 2004;23:2246–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz C, Escribano V, Morgado E, Molina M, Mazon MJ. Cell-type-dependent repression of yeast a-specific genes requires Itc1p, a subunit of the Isw2p-Itc1p chromatin remodelling complex. Microbiology. 2003;149:341–51. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukiyama T, Palmer J, Landel CC, Shiloach J, Wu C. Characterization of the imitation switch subfamily of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1999;13:686–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelbart ME, Rechsteiner T, Richmond TJ, Tsukiyama T. Interactions of Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex with nucleosomal arrays: analyses using recombinant yeast histones and immobilized templates. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2098–106. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2098-2106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazzio TG, et al. Widespread collaboration of Isw2 and Sin3-Rpd3 chromatin remodeling complexes in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6450–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6450-6460.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee S, et al. Rapid analysis of the DNA-binding specificities of transcription factors with DNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1331–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck MJ, Lieb JD. ChIP-chip: considerations for the design, analysis, and application of genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. Genomics. 2004;83:349–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanlon SE, Lieb JD. Progress and challenges in profiling the dynamics of chromatin and transcription factor binding with DNA microarrays. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winzeler EA, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–6. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–41. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao B, Shibata Y, Strahl BD, Lieb JD. Dimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 36 demarcates regulatory and nonregulatory chromatin genome-wide. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9447–59. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9447-9459.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buck M, Nobel A, Lieb J. ChIPOTle: a user-friendly tool for the analysis of ChIP-chip data. Genome Biology. 2005;6:R97. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-11-r97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CK, Shibata Y, Rao B, Strahl BD, Lieb JD. Evidence for nucleosome depletion at active regulatory regions genome-wide. Nat Genet. 2004;36:900–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Brutlag DL, Liu JS. BioProspector: discovering conserved DNA motifs in upstream regulatory regions of co-expressed genes. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2001:127–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu XS, Brutlag DL, Liu JS. An algorithm for finding protein-DNA binding sites with applications to chromatin-immunoprecipitation microarray experiments. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:835–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proft M, Gibbons FD, Copeland M, Roth FP, Struhl K. Genomewide identification of Sko1 target promoters reveals a regulatory network that operates in response to osmotic stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1343–52. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1343-1352.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–90. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haverty PM, Hansen U, Weng Z. Computational inference of transcriptional regulatory networks from expression profiling and transcription factor binding site identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:179–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radonjic M, et al. Genome-wide analyses reveal RNA polymerase II located upstream of genes poised for rapid response upon S. cerevisiae stationary phase exit. Mol Cell. 2005;18:171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Rap1 protein and mRNA levels decrease as glucose is depleted. A) 20 μg of whole-cell extract was separated by a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and probed with anti-Rap1 antibody. B) mRNA levels for Rap1, as measured by microarray43, decrease upon diauxic shift.

Supplemental Figure 2. Confirmation of ChIP-chip results. A. Representative agarose gel image of ChIP-PCR results, showing results from two genomic regions upstream of ENB1 and VHS1. ChIP (IP) samples are loaded next to their corresponding input (IN). The top band in every lane is the test fragment, and the bottom band is specific to a control (YHR131C). B. The average ratio (IP/Input) for Rap1 IPs, during exponential growth, after depletion of glucose (72 hrs), and in a tup1Δ background, is plotted with their standard error at 11 loci. The ratio for any site is determined by the (intensity of the test fragment in IP / intensity of the control fragment in IP) / (intensity of the test fragment in input / intensity of the control fragment in input) C. The average ratio (IP/Input) for Tup1 IPs is plotted with their standard error at 11 loci. D. Two biological replicates of Rap1 ChIPs after glucose depletion (72 hrs) were hybridized directly on the same microarray with Rap1 ChIPs from cells grown in high glucose. The average ratios reported from probes representing the 52 low-glucose Rap1 targets, 262 static Rap1 targets, and telomeric targets is plotted, along with their standard errors.

Supplemental Figure 3. Confirmation of ChIP-chip results at the SGA1 locus.

A. The open reading frames for SGA1 and FMC1 are shown. An upstream dubious open reading frame is shaded grey. Arrows indicate direction of transcription. The regions tested by ChIP-PCR (A-D) and the elements on the microarray (1-7) are shown below. B. Rap1 IPs during exponential growth (+ glucose) as measured by the microarray (top; 8 replicates) and PCR (bottom; 4 replicates). C. Rap1 IPs in low glucose (72 hrs) as measured by the microarray (top; 7 replicates) and PCR (bottom; 4 replicates). D. Tup1 IPs during exponential growth (+ glucose) as measured by microarray (top; 8 replicate) and PCR (bottom; 3 replicates). E. The enrichment at microarray element 4 is shown for the entire timecourse. F. A representative gel image for one replicate at each PCR region. IP (IP) samples are loaded next to their corresponding input (IN). The top band in every lane is the test fragment, which is compared to the bottom control band (YHR131C).

Supplemental Figure 4. Computational screens predict the involvement of Tup1-Ssn6 proteins in blocking Rap1p binding. A. Schematic representation of two computational screens for effector of Rap1 conditional binding. Screen 1 compares low-glucose targets versus static targets and screen 2 compares low-glucose targets versus all yeast intergenic regions. B. Results for the two computational screens listed by Pearson correlation (r) to the classifier variable. The p-value was estimated by 10,000 permutations. The GO biological process is listed for each protein (lower row).

Supplemental Figure 5. Rap1 binding and glycolysis

A) Rap1 binds upstream of at least one enzyme involved in each of the eleven steps required to metabolize glucose into ethanol. Static Rap1 targets are shown in red and low-glucose targets are in blue. Arrows indicate the flow of substrate. B) During growth in low-glucose, Rap1 binds upstream of genes involved in alternative carbon-source utilization.