Abstract

The extensive glycosylation of HIV-1 envelope proteins (Env), gp120/gp41, is known to play an important role in evasion of host immune response by masking key neutralization epitopes and presenting the Env glycosylation as “self” to the host immune system. The Env glycosylation is mostly conserved but continues to evolve to modulate viral infectivity. Thus, profiling Env glycosylation and distinguishing interclade and intraclade glycosylation variations are necessary components in unraveling the effects of glycosylation on Env’s immunogenicity. Here, we describe a mass spectrometry-based approach to characterize the glycosylation profiles of two rVV-expressed clade C Envs by identifying the glycan motifs on each glycosylation site and determining the degree of glycosylation site occupancy. One Env is a wild-type Env, while the other is a synthetic “consensus” sequence (C.CON). The observed differences in the glycosylation profiles between the two clade C Envs show that C.CON has more unutilized sites and high levels of high mannose glycans; these features mimic the glycosylation profile of a Group M consensus immunogen, CON-S. Our results also reveal a clade-specific glycosylation pattern. Discerning interclade and intraclade glycosylation variations could provide valuable information in understanding the molecular differences among the different HIV-1 clades and in designing new Env-based immunogens.

Keywords: HIV, envelope glycoprotein, glycosylation, vaccine, mass spectrometry

Introduction

Among the distinct HIV-1 clades that have expanded worldwide, clade C infection is currently one of the fastest growing HIV-1 infections1–3. Indeed, it accounts for more than 50% of all global infections with 94% of HIV/AIDS clade C cases in sub-Saharan Africa4,5. Clade C viruses in general have unique biological and immunological properties that include ease of transmission6, exclusive CCR5 tropism during early infection7,8, sensitivity to neutralization from clade C serum donors9,10, and resistance to neutralization by carbohydrate binding antibody, 2G12, and by gp41 specific antibody, 2F59,11,12. Additionally, clade C Envs have unique molecular features, including highly conserved V3 region compared to clade B11,13, high amino acid sequence variability in the C3 region, a greater degree of amphipathicity of the α-2 helix14, shorter V1–V4 loops for better neutralization sensitivity15, and shorter gp120 early transmitted viruses10,11. These distinct molecular and immunological clade C Env features illustrate the relevance of correlating the clade-specific structural differences with the Env’s immunological properties. Establishing the relationship between clade-specific Env’s immunological properties and structural elements could provide fundamental knowledge about efficacious design of future HIV vaccine candidates.

One important molecular and structural feature of the Env that needs significantly more attention is the N-glycosylation profiles of Env. Env glycosylation is fundamental in every aspect of HIV biology that spans from proper Env folding and processing16,17, virus transmission10,18–20, and immune evasive mechanisms21–23. There are at least potential 24 N-linked glycosylation sites for a given Env that can be populated with high mannose, hybrid, or a highly diverse array of complex glycans24–28. The site utilization is known to vary within isolates and across different clades allowing the global glycosylation to evolve to maintain the glycan shield and facilitate viral transmission and dissemination23,29,30. Thus, the systematic analysis of the glycosylation profiles of Env could provide valuable insights in designing good Env immunogens.

An important step towards a systematic analysis of the glycosylation profiles of Env immunogen is to identify and compare distinct intraclade and interclade Env glycosylation profiles. A detailed characterization of the glycan patterns and determining the extent of site occupancy of potential N-glycosylation (PNG) sites are critical steps in elucidating certain glycosylation trends that influence the immunogenic and antigenic properties of Envs. And given the importance of glycosylation in HIV pathogenesis, molecular insights provided by glycosylation profiling are potentially useful in HIV vaccine development.

Recently, we have shown by a glycopeptide-based mass mapping approach that Envs’ glycosylation correlates with their immunological response27,28. We evaluated two recombinant Env immunogens- one derived from the Group M HIV-1 consensus (CON-S ΔCFI gp140) and one derived from a clade B primary isolate (JR-FL ΔCF gp140) and found that the better Env immunogen (CON-S) has predominantly high mannose glycans populating the region surrounding the immunodominant V3 region and has more unutilized glycosylation sites throughout the protein. While the CON-S glycosylation profile provides one example of the glycosylation profile of a good Env immunogen, several questions still remain. 1) Is the glycosylation profile displayed by CON-S a central glycosylation pattern for all consensus Env immunogens? 2) How do intraclade and interclade glycosylation profiles between Env immunogens vary? To address these questions it is necessary to examine distinctive glycosylation patterns of Env immunogens derived from other clades, including those from a clade consensus, and determine interclade and intraclade glycosylation trends.

Towards this goal, we characterized the glycosylation profile of two clade C recombinant Envs using the same glycopeptide-based mass analysis approach described in our previous study27,28. The clade C Envs are derived from immunogens expressing clade C consensus sequence, C.CON, and a clade C primary isolate sequence, C.97ZA012. Comparison of the glycosylation profiles of the clade C Envs reveals the following characteristic glycosylation profile - the consensus protein, C.CON, has a high level of high mannose glycans and a high degree of unutilized glycosylation sites compared to C.97ZA012. Our analysis also shows that both C.CON and C.97ZA012 share a common glycosylation pattern in the C2 and C3 regions where predominantly high mannose glycans are observed. This glycosylation profile could possibly influence the local Env structural conformation in these regions and may explain the increased infectivity in clade C viruses. Comparison of the glycosylation profiles of Envs of the same clade provides information on intraclade variations of glycosylation that help to modulate the intrinsic clade-specific molecular, structural, and immunological properties.

Experimental Section

Reagents

Ammonium bicarbonate, Trizma@ hydrochloride, Trizma@ base, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), acetic acid, HPLC grade acetonitrile (CH3CN) and methanol (CH3OH), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), urea, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (α-CHCA), iodoacetamide (IAA), dithiothreitol (DTT), and formic acid were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Water was purified using a Millipore Direct-Q3 Water Purification System (Billerica, MA). Sequencing grade trypsin (Tp), proteomics grade N-Glycosidase F (PNGase F) from Elizabethkingia meningosepticum, and glycerol-free PNGase F from Flavobacterium meningosepticum were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA), respectively.

Expression and Purification of HIV-1 Subtype C Envelope Proteins

C.CON and C.97ZA012 envelope proteins were obtained from the Duke Human Vaccine Research Institute in Durham N.C. These proteins were constructed with internal deletions, which generate marked improvement in oligomerization and immunogenicity31. Both Envs were expressed and purified as described in literature32,33. Briefly, recombinant vaccinia viruses (rVVs) expressing C.CON gp140 ΔCF and C.97ZA012 gp140 ΔCFI genes were used for production of soluble Envs34,35. For batch production of recombinant Envs, Envs were produced by infecting 293T cells with rVVs. The 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in T150 tissue culture flasks and were grown to confluence at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of about one before infecting with rVVs. At two hours postinfection, the cell culture was washed with serum free DMEM and the infection was allowed to proceed for 72 hours. Recombinant Envs were then purified from supernatants of rVV-infected 293T cell cultures using Galanthus nivalis lectin-agarose (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) column chromatography and stored at −70°C until use. A typical batch production of clade C Envs (using 30 T-150 TC flasks) would yield ~600–800 µg of protein. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance. Purified recombinant envelope proteins were concentrated for MS-based glycosylation analysis.

Digestion of envelope proteins

Details of protein digestion have been described elsewhere27. Briefly, samples containing 200 µg of the HIV-1 Envs, with protein concentration >4 mg/mL, were denatured with 6M urea in 100 mM tris buffer (pH 8.5) containing 3 mM EDTA. The proteins were reduced and alkylated with 10 mM DTT and 15 mM IAA at RT, respectively, and were digested at 37°C with trypsin at a protein:enzyme ratio of 30:1 (w/w) overnight, followed by a second trypsin digestion under the same conditions. The resulting HIV envelope glycoprotein digest was either subjected to off-line reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) fractionation for MALDI or RP-HPLC/ESI-FTICR MS analyses27,36. To ensure reproducibility and reliability of our method, protein digestion was performed three times on different days with Env samples obtained from the same batch and analyzed with the same experimental procedure. In addition, Env samples obtained from two different batches with different protein concentration were also digested and analyzed to determine lot-to-lot variations in glycosylation profile.

N-Deglycosylation

The Env deglycosylation experiment for MALDI MS analysis was performed as described elsewhere27. Briefly, glycopeptide enriched fractions were collected from an HPLC, as described above, and the glycans were released by adding 12 µL of 20 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) and 4 µL of diluted PNGase F solution (500 units/mL). The reaction was incubated overnight at 37°C and was stopped by heating the sample to 100°C. The resulting solution was subsequently analyzed by MALDI MS. Deglycosylation experiment for LC/ESI-FTICR MS analysis was performed by incubating ~50 µg of the Env with 1 µL of PNGase F solution (≥ 4500 units/mL) for a week at 37°C. Deglycosylated Env proteins were digested at 37°C with trypsin using the same digestion procedure described above. The resulting tryptic digest was analyzed by LC/ESI-FTICR MS.

Mass Spectrometry

MALDI MS and MS/MS experiments were performed on an Applied Biosystems 4700 Proteomics Analyzer mass spectrometer (Foster City, CA) operated in the positive ion mode. Samples were prepared by mixing equal volumes (1 µL each) of the analyte and matrix solutions in a microcentrifuge tube, then immediately deposited on a MALDI plate, and allowed to dry in air. Matrix used for the experiment consists of a 1:1 mixture of 10 mg/mL each of α-CHCA and DHB. Samples were irradiated with an ND-YAG laser (355 nm) operated at 200 Hz. High resolution mass spectra were acquired in the reflectron mode and were generated by averaging 3000 individual laser shots into a single spectrum. Each spectrum was accumulated from 60 shots at 50 different locations within the MALDI spot. The laser intensity was optimized to obtain adequate signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio and resolution for each sample. MALDI MS/MS data were acquired using a collision energy of 1 kV with air as collision gas.

LC/ESI-FTICR MS and MS/MS experiments were performed using a hybrid linear ion-trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (LTQ-FT, ThermoScientific, San Jose, CA) directly coupled to Dionex UltiMate capillary LC system (Sunnyvale, CA) equipped with a FAMOS well plate autosampler. Mobile phases utilized for the experiment consisted of solvent A: 99.9% deionized H2O + 0.1% formic acid and solvent B: 99.9 % CH3CN + 0.1% formic acid. Five microliters of the sample was injected onto C18 PepMap™ 300 column (300 µm i.d. × 15 cm, 300 Å, LC Packings, Sunnyvale, CA) at a flow rate of 5 µL/min. The following CH3CN/H2O multistep gradient was used: 5% mobile phase B for 5 min, followed a linear increase to 40% B in 50 min a linear increase to 90% B in 10 min. The column was held at 95% B for 10 minutes before re-equilibration. A short wash and blank run were performed between every sample to ensure no sample carry-over. The ESI source was operated in the following conditions: source voltage of 2.8 kV, capillary temperature of 200°C, and capillary voltage of 46 V. Data were collected in a data-dependent fashion in which the five most intense ions in an FT scan were sequentially and dynamically selected for subsequent collision-induced dissociation (CID) in the LTQ linear ion trap using a normalized collision energy of 30% and a 3 minute dynamic exclusion window.

Glycopeptide Identification

Glycopeptide compositions with singly utilized glycosylation site were elucidated using the web-based-tools, GlycoPep DB37 and GlycoPep ID38. Details of the analysis for glycopeptides have been described previously27,37,38. Briefly, compositional analysis was performed by identifying the peptide portion of a glycopeptide of interest from MS and MS/MS spectra generated from MALDI MS and LC/ESI-FTICR MS analyses. Peptide portions were elucidated from characteristic signature fragment ions of the cross-ring cleavages, 0,2X or 0Y1 ions in the MS/MS data using GlycoPep ID. Once the peptide portion is identified, plausible glycopeptide compositions are obtained from MS data using GlycoPep DB. For glycopeptides with multiply utilized glycosylation sites, experimental masses of singly charged glycopeptide ions from MS data were submitted to GlycoMod39. This program calculates plausible glycopeptide compositions from the set of experimental mass values entered by the user and compares these mass values with theoretical mass values, then generates a list of plausible glycopeptide compositions within a specified mass error. Plausible glycopeptide compositions in GlycoMod were deduced by providing the mass of the singly charged glycopeptide ion, enzyme, protein sequence, cysteine modification, mass tolerance, and the possible types of glycans present in the glycopeptide. Plausible glycopeptide compositions were manually confirmed and validated using MS/MS data.

Peptide Identification

Non-glycosylated peptides were identified by searching raw MS/MS data acquired on the hybrid LTQ FTICR mass spectrometer against a custom HIV database with 107 protein entries, obtained from the Los Alamos HIV sequence database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content), using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, UK, version 2.2.04). The peak list was extracted from raw files using BioWorksBrowser (Thermo Electron Corporation, version 3.5). DTA files were searched specifying the following parameters: (a) enzyme: trypsin, (b) missed cleavage: 2, (c) fixed modification: carbamidomethyl, (d) variable modification: methionine oxidation, and carbamyl, (e) peptide tolerance of 0.8 Da, and (f) MS/MS tolerance of 0.4 Da. Peptides identified from Mascot search were manually validated from MS/MS spectra to ensure major fragmentation ions (b and y ions) were observed especially for peptides generated from PNGase treated Envs containing potential N to D conversions.

Results

C.CON and C.97ZA012 Envs

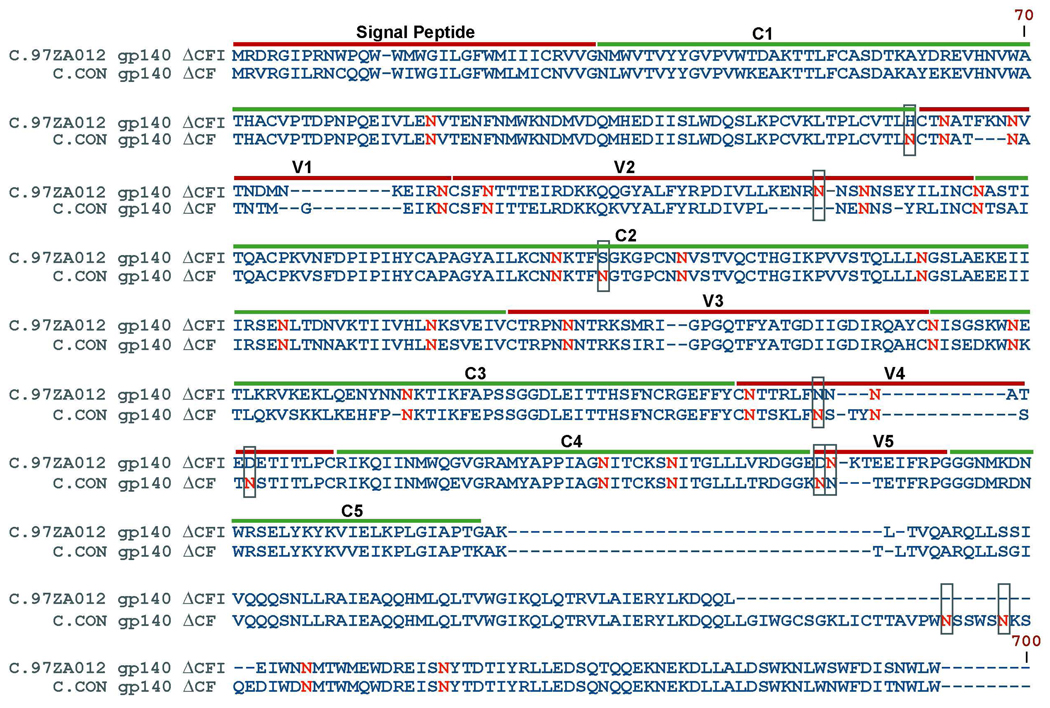

We evaluated the glycosylation profiles of two clade C Env immunogens, specifically, one protein is a synthetic Env sequence, C.CON, generated from the alignment of HIV-1 clade C gene sequences available from the 2003 Los Alamos HIV-1 Database; the other protein is a primary isolate Env, C.97ZA012, from an HIV-1 strain from South Africa12. Both Envs were constructed with shortened variable loops (V1–V5), and deletions of the cleavage site (C), fusion domain (F), (ΔCF) for C.CON and deletions of the cleavage site (C), fusion domain (F), the immunodominant region (I) in the transmembrane region (ΔCFI) for C.97ZA01232,33. The two C Envs are designated as C.CON gp140ΔCF and C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCFI. It should be noted that immunology data showed no apparent difference between gp140ΔCF and gp140ΔCFI constructs in terms of eliciting antibody response33. The full sequence alignment of C.CON gp140ΔCF and C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCFI with potential N-linked glycosylation (PNG) sites in red is shown in Figure 1. For consistency, the amino acid numbering positions were based on the reference strain, HXB2 (SwissProt accession number P04578). The protein sequence of the two Envs differs by 17%, as determined from the protein sequence alignment analysis tool, ClustalX40. There are 29 PNG sites for C.CON gp140ΔCF and 24 PNG sites for C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCFI. Between the two clade C Envs, 22 PNG sites are highly conserved and nine are not conserved as shown in green boxes (Figure 1). Conserved PNG sites are spread throughout the Env sequence with eight PNG sites located in the hypervariable regions: V1 (N133, N139, and N156), V2 (N160 and N187), V3 (N301), and V4 (N386 and N397), and 14 conserved PNG sites located in the conserved regions: C1 (N88), C2 (N197, N230, N241, N262, N276, and N289), C3 (N332, N339, and N356), and C4 (N442, and N448), and the transmembrane (N625 and N637) regions. PNG sites that are not conserved shown in green boxes in Figure 1 and are located in the C1, V2, C2, V4, V5, and transmembrane regions. For simplicity, C.CON gp140ΔCF and C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCFI are referred as C.CON and wild-type C, from here on and data presented in the following sections are from samples that were processed and analyzed three times using the same batch. These analyses obtained reproducible glycosylation profiles.

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of C.CON gp140 ΔCFI and C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCF. Dashes indicate gaps in amino acid sequence and the location of the variable (V1–V5) and conserved (C1–C5) regions are shown. Potential glycosylation sites are in red with difference in potential glycosylation sites are boxed. To standardize the sequence positions, numbering was based on the reference HIV strain, HXB2.

Glycosylation Analysis of C.CON and Wild-Type C Envs

To determine the glycosylation motifs on each glycosylation site as well as to identify unutilized glycosylation sites, the Envs were denatured, reduced, and alkylated with IAA before being subjected to an in-solution tryptic digestion. The resulting digest mixture was divided into two equal aliquots, with one aliquot analyzed by MALDI MS in both linear and reflectron modes and the other by LC/ESI-FTICR MS. Before mass analysis, both aliquots were subjected to reverse-phase HPLC to separate the glycopeptides from peptides. Similar to our previous study27,28, the glycopeptide compositions and the glycosylation site occupancy are unambiguously identified from tandem MS analysis and deglycosylation experiments in combination with the web-based analysis tools, GlycoPep DB, GlycoPep ID, and GlycoMod. A 100% glycosylation site coverage was obtained for both C.CON and wild-type C. Table 1 summarizes the glycosylation site coverage showing the identified tryptic peptides bearing single and multiple potential N-linked glycosylation (PNG) sites (NXT/S) and their respective glycosylation site occupancy. Table 1 shows that C.CON has a lower degree of glycosylation site occupancy compared to wild-type C. These glycosylation sites are either fully or variably unutilized. C.CON differs in the degree glycosylation site occupancy with wild-type C in the following regions: at the end of the V2 loop, the V4 loop, and the transmembrane region.

Table 1.

Tryptic glycopeptides detected by MALDI MS and LC/ESI-FTICR MS

| Glycopeptide | Number of Potential Glycosylation Sites |

Number of Utilized Sites |

|---|---|---|

| C.97ZA012 gp140 ΔCFI | ||

| A. Glycopeptides with fully utilized sites | ||

| EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQEIVLEN88VTENFNMWK | 1 | 1 |

| LTPLCVTLHCTN133ATFKNN139VTNDMNK | 2 | 2 |

| CNN230K | 1 | 1 |

| GPCNN241VSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLN262GSLAEK | 2 | 2 |

| SEN275LTDNVK | 1 | 1 |

| TIIVHLN289K | 1 | 1 |

| SVEIVCTRPNN301NTR | 1 | 1 |

| QAYCN332ISGSK | 1 | 1 |

| WN339ETLKR | 1 | 1 |

| LQENYNNN356K | 1 | 1 |

| GEFFYCN386TTR | 1 | 1 |

| LFNNN397ATEDETITLPCR | 1 | 1 |

| AMYAPPIAGN442ITCK | 1 | 1 |

| SN448ITGLLLVR | 1 | 1 |

| DGGEDN462KTEEIFRPGGGNMK | 1 | 1 |

| DQQLEIWN625MTWMEWDREISN637YTDTIYR | 2 | 2 |

| B. Glycopeptides with partially utilized sites | ||

| N156CSFN160TTTEIR | 2 | 1 and 2 |

| ENRN184NSN187NSEYILINCN197AST ITQACPK | 3 | 2 and 3 |

| C.CON gp140 ΔCF | ||

| A. Glycopeptides with fully utilized sites | ||

| EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQEVVLEN88VTEHFNMWK | 1 | 1 |

| LINCN197TSAITQACPK | 1 | 1 |

| CNN230K | 1 | 1 |

| TFN234GTGPCNN241VSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLN262GSLAEEEIIIR | 3 | 3 |

| SEN275LTNNAK | 1 | 1 |

| TIIVHLN289ESVEICTRPNN301NTR | 2 | 2 |

| QAHN332ISSEDKWN339K | 2 | 2 |

| LKEHPN356K/ LKEHPN356KTIK | 1 | 1 |

| AMYAPPIAGN442ITCK | 1 | 1 |

| SN448ITGLLLTR | 1 | 1 |

| DGGKN461NTETFRPGGGDMR | 1 | 1 |

| EISN637YTDTIYR | 1 | 1 |

| B. Glycopeptides with partially utilized sites | ||

| LTPLCVTLN130CTN133ATN136ATNTMGEIK | 3 | 2 |

| N156CSFN160ITELR | 2 | 1 and 2 |

| LDIVPLNEN187NSYR | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| GEFFYCN386TSK | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| LFN392STYN397STN411STITLPCR | 3 | 2 and 3 |

| LICTTAVPWN611SSWSN616K | 2 | 1 |

| C. Nonglycosylated Peptide | ||

| SQEDIWDN625MTWMQWDR | 1 | 0 |

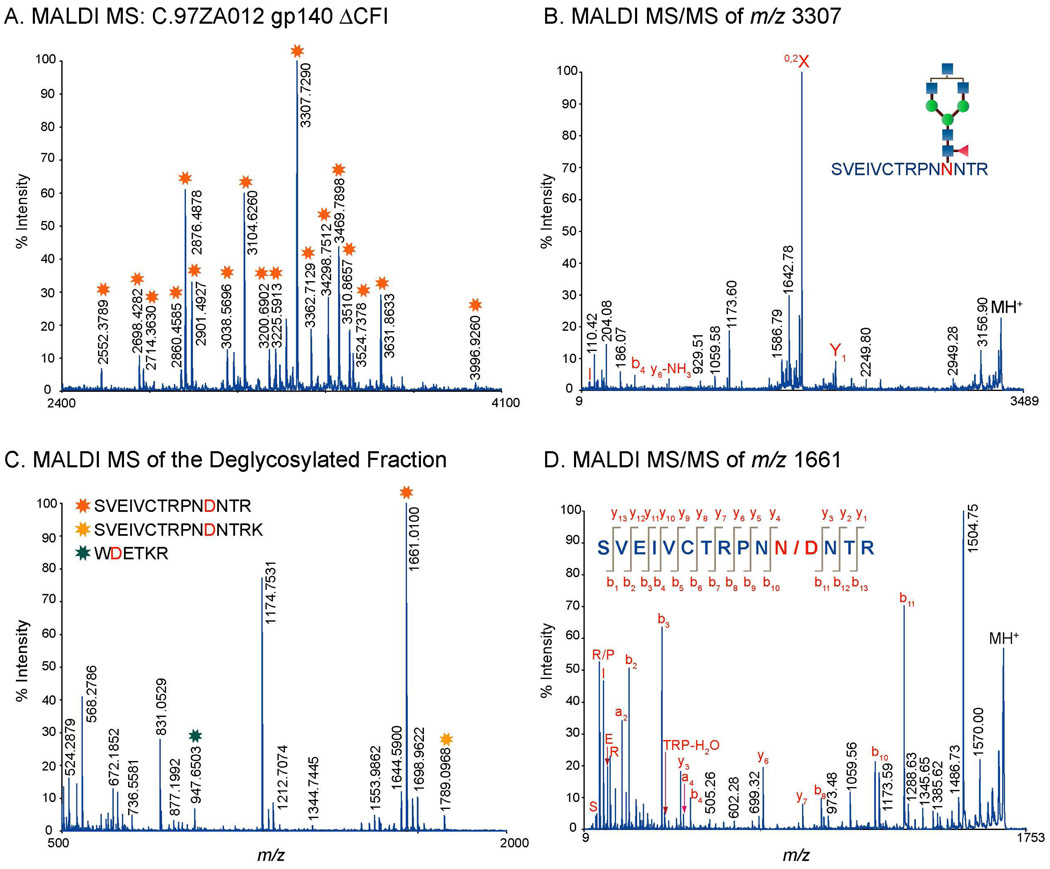

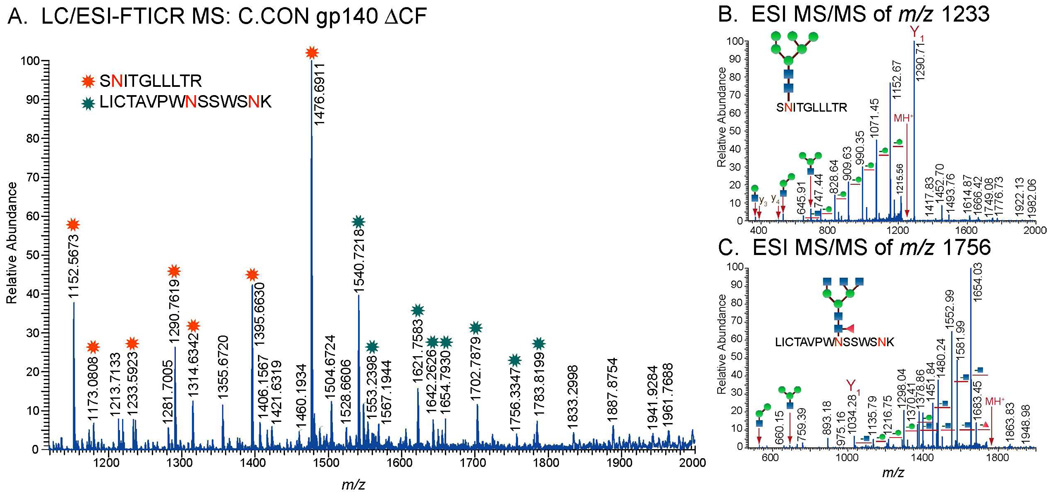

Glycopeptides identified from MALDI MS and LC/ESI-FTICR MS analyses bear glycans consisting of high mannose, hybrid, and complex type structures as shown in Table 2 (see Supplementary Table for a complete list). The glycopeptides have either single or multiple glycosylation sites. Figure 2A and Figure 3A show MALDI MS and LC/ESI-FTICR MS spectra typical of a glycopeptide rich fraction. These data show glycopeptides with the singly utilized glycosylation site found at the beginning of the V3 region for wild-type C (Figure 2A), and the C4 and the transmembrane regions for C.CON (Figure 3A). A characteristic feature of the mass spectra of glycopeptides with a singly utilized glycosylation site is a series of singly charged peaks in MALDI MS or doubly/multiply charged peaks in LC/ESI-FTICR MS separated by a mass difference equivalent to the mass of the monosaccharide units (hexose (Hex), N-acetylglucosamine (HexNAc), fucose (Fuc), and sialic acid (NeuNAc)). These characteristic patterns in the MS data helped identify ions that were likely glycopeptides.

Table 2.

Representative Glyopeptide Compositions for C.97ZA012 and C.CON. The complete list is found in Supplementary Tables 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B online.

| Env Domain |

Charge State |

Experimental Mass |

Theoretical Mass |

Mass Error |

Peptide Sequence | Mod | Glycan Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.97ZA012 gp140 ΔCFI | |||||||

| V1 | 2+ | 1546.7388 | 1546.6678 | 33 | LTPCVTLHCTNATFK | [Hex]5[HexNAc]2 | |

| 2+ | 1283.2672 | 1283.2263 | 32 | LTPCVTLHCTNATFK | [Hex]5[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1434.3174 | 1434.2757 | 29 | LTPCVTLHCTNATFK | [Hex]6[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1[NeuNAc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1247.5654 | 1247.5314 | 27 | LTPCVTLHCTNATFK | [Hex]9[HexNAc]2 | ||

| C2 | 4+ | 1701.5125 | 1701.5314 | 11 | GPCNNVSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLNGSLAEKEIIIR | [Hex]12[HexNAc]4 | |

| 4+ | 1823.1356 | 1832.0710 | 35 | GPCNNVSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLNGSLAEKEIIIR | [Hex]15[HexNAc]4 | ||

| 4+ | 1904.1096 | 1904.0974 | 6 | GPCNNVSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLNGSLAEKEIIIR | [Hex]17[HexNAc]4 | ||

| C2–V3 | 2+ | 1779.3263 | 1779.2562 | 39 | SVEIVCTRPNNNTR | [Hex]4[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1[NueNAc]1 | |

| 1+ | 3282.2622 | 3282.4045 | 43 | SVEIVCTRPNNNTR | [Hex]5[HexNAc]4 | ||

| 2+ | 1816.3529 | 1816.2746 | 43 | SVEIVCTRPNNNTR | [Hex]5[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 1+ | 3996.7792 | 3996.6742 | 26 | SVEIVCTRPNNNTR | [Hex]6[HexNAc]6[Fuc]1 | ||

| C4 | 2+ | 1367.1844 | 1367.1442 | 29 | SNITGLLLVR | [Hex]3[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | |

| 2+ | 1448.2194 | 1448.1705 | 34 | SNITGLLLVR | [Hex]4[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1151.5758 | 1151.5489 | 23 | SNITGLLLVR | [Hex]5[HexNAc]2 | ||

| 1+ | 3684.7815 | 3584.5716 | 59 | SNITGLLLVR | [Hex]7[HexNAc]6[Fuc]1 | ||

| C.CON gp140 ΔCF | |||||||

| C1 | 4+ | 1366.6536 | 1366.6102 | 32 | EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQE IVLENVTENFNMWK | [Hex]3[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1 | |

| 4+ | 1417.4248 | 1417.3800 | 32 | EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQE IVLENVTENFNMWK | [Hex]3[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 4+ | 1468.21.8 | 1468.1499 | 41 | EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQE IVLENVTENFNMWK | [Hex]3[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 4+ | 1447.67703 | 1447.6366 | 28 | EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQE IVLENVTENFNMWK | [Hex]5[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 4+ | 1350.1262 | 1350.0956 | 23 | EVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQE IVLENVTENFNMWK | [Hex]6[HexNAc]2 | ||

| V2-C2 | 2+ | 1547.7246 | 1547.6698 | 35 | LINCNTSAITQACPK | [Hex]4[HexNAc]3[Fuc]1 | |

| 2+ | 1794.8353 | 1794.7572 | 44 | LINCNTSAITQACPK | [Hex]4[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1[NeuNAc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1896.3878 | 1896.2969 | 48 | LINCNTSAITQACPK | [Hex]4[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1[NeuNAc]1 | ||

| C3 | 1+ | 2558.2378 | 2558.1389 | 39 | EHFPNKTIK | [Hex]3[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1 | |

| 1+ | 2761.3391 | 2761.2184 | 44 | EHFPNKTIK | [Hex]3[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1041.8371 | 1041.8127 | 23 | LKEHFPNKTIK | [Hex]5[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1 | ||

| V4 | 2+ | 1397.0778 | 1397.0330 | 32 | GEFFYCNTSK | [Hex]7[HexNAc]2 | |

| 2+ | 1478.1072 | 1478.0594 | 32 | GEFFYCNTSK | [Hex]8[HexNAc]2 | ||

| 1+ | 3117.2520 | 3117.1644 | 28 | GEFFYCNTSK | [Hex]9[HexNAc]2 | ||

| 2+ | 1575.6453 | 1575.6098 | 23 | GEFFYCNTSK | [Hex]4[HexNAc]4[Fuc]1[NeuNAc]1 | ||

| TM | 2+ | 1511.6934 | 1511.6371 | 37 | EISNYTDTIYR | [Hex]3[HexNAc]5[Fuc]1 | |

| 2+ | 1296.0817 | 1296.0418 | 31 | EISNYTDTIYR | [Hex]4[HexNAc]3[Fuc]1 | ||

| 2+ | 1458.1374 | 1458.0947 | 29 | EISNYTDTIYR | [Hex]7[HexNAc]2 | ||

| 2+ | 1620.2043 | 1620.1475 | 35 | EISNYTDTIYR | [Hex]9[HexNAc]2 | ||

Figure 2.

A. MALDI MS spectrum of the glycopeptide rich fraction generated from the proteolytic digest C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCF. B. MALDI MS/MS spectrum of the identified tryptic glycopeptide at m/z 3307. C. MALDI MS of the PNGase-treated glycopeptide rich fraction shown in A. D. MALDI MS/MS spectrum the deglycosylated peptide (m/z 1661, shown in C in the V3 region. Note that peaks with asterisks(*) in A are glycopeptide peaks.

Figure 3.

A. LC/ESI-FTICR MS spectrum of the glycopeptide rich fraction showing two identified glycopeptides in the C4 and the transmembrane region for C.CON gp140 ΔCFI. ESI-MS/MS spectra showing the fragmentation pattern of the glycopeptides in the C4 region (B) and the transmembrane region (C). Only one site is utilized. Note that peaks with asterisks(*) are glycopeptide peaks.

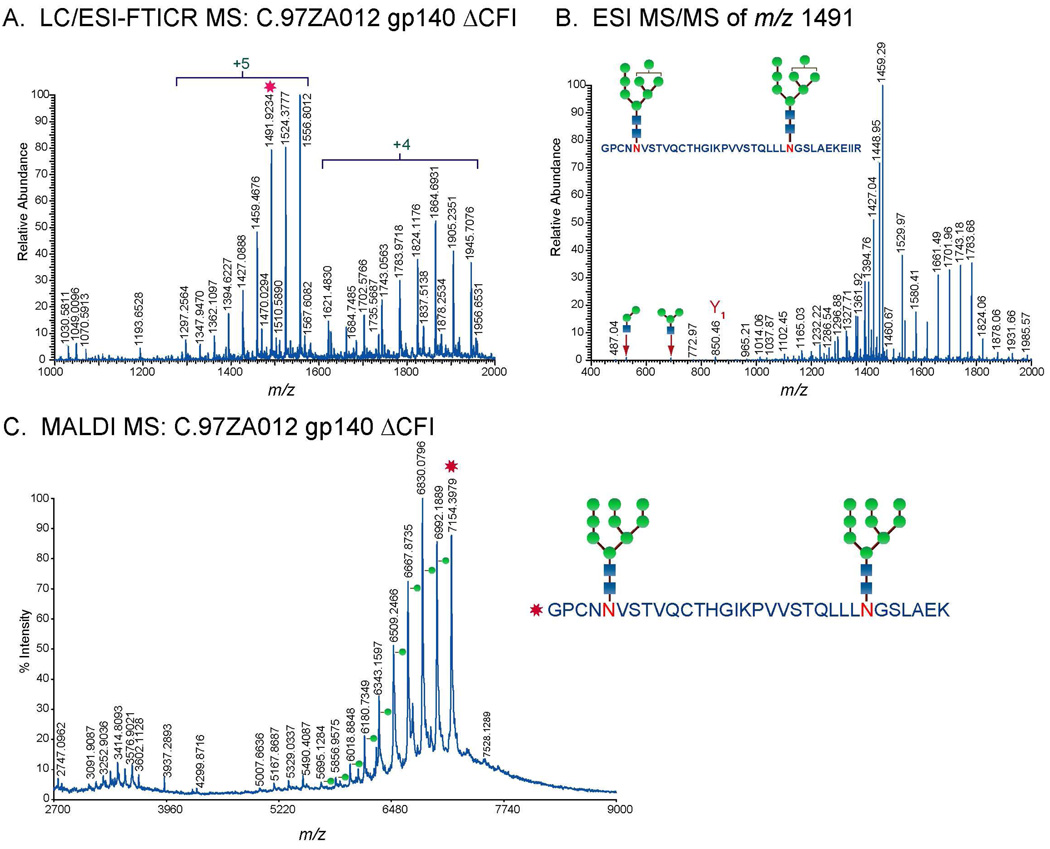

For both MS techniques, compositions of glycopeptides with one glycosylation site were elucidated from the fragmentation pattern of the glycopeptide peaks observed in the high resolution mass spectra. The peptide portion and the glycan compositions were identified from the MS/MS data (Figure 2B, Figure 3B, and 3C). The peptide portion was determined from the characteristic glycosidic cleavages, 0,2X or Y1 ions (Figure 2B, Figure 3B, and 3C). Peptide sequences identified from MALDI MS/MS were further validated from the MS and MS/MS analysis of the deglycosylated glycopeptide fraction of interest (Figure 2C and 2D). A typical MALDI MS spectrum of the deglycosylated fraction shows deglycosylated peptides with potential N to D conversion depending on the site utilization (Figure 2C). Peptide sequences were confirmed from the observed fragmentation pattern in MALDI MS/MS spectrum (Figure 2D). For glycopeptides with multiple glycosylation sites, glycopeptide compositions were determined from GlycoMod using the data obtained from high resolution LC/ESI-FTICR MS (Figure 4A) or MALDI MS in the linear mode (Figure 4C). Results from GlycoMod were validated using the MS/MS data (Figure 4B). Overall, a total of 300 unique glycopeptide compositions per Env were identified for both singly and multiply glycosylated glycopeptides. The full list of the identified glycopeptides is included in the supplementary information.

Figure 4.

A. LC/ESI-FTICR MS spectrum of the doubly glycosylated peptide with one missed cleavage, GPCNN241VSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLN262GSLAEKEIIIR, in the C2 region of C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCF. B. ESI-MS/MS spectra showing the fragmentation pattern of the doubly glycosylated peptide in A. C. MALDI MS spectrum of the doubly glycosylated peptide, GPCNN241VSTVQCTHGIKPVVSTQLLLN262GSLAEK, in the C2 region of C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCF measured in the linear ion mode.

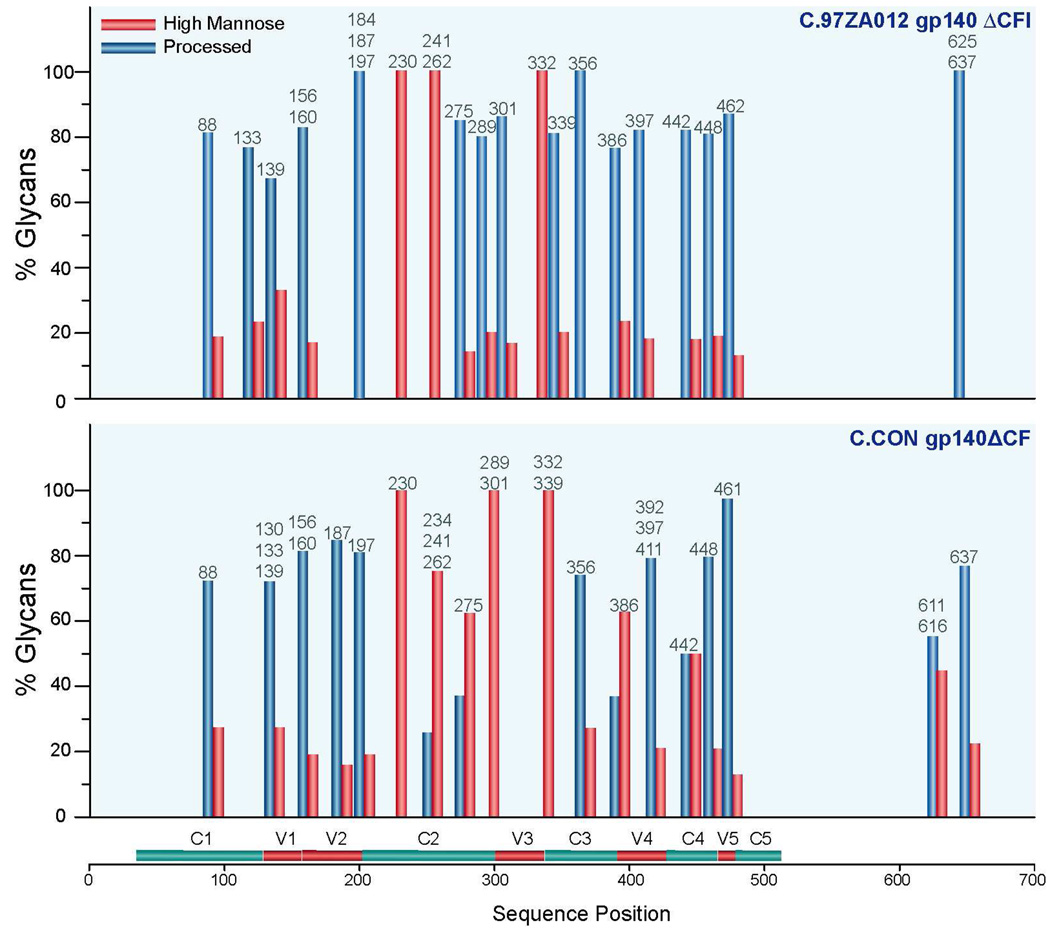

Glycan Profile of C.CON and Wild-Type C Envs

The glycan compositions of the two clade C Envs were broadly grouped according to the type of glycan found on each glycopeptide and were plotted in a bar graph. A glycopeptide could have a single or multiple glycosylation sites. Each glycopeptide is represented with a bar or a pair of bars corresponding to the glycan percentage of processed or high mannose glycans that is arranged according to the Env sequence position. The following criteria was used to determine the relative number of processed or high mannose glycans: “high mannose” includes structures with 5–9 mannose units and “processed glycans” includes both hybrid and complex type structures with hexose (Hex) ≥3 and N-acetylglucosamine (HexNAc) ≥ 4 or Hex ≥ 4 and HexNAc ≥ 327. Bar graphs showing the differential glycan profiles between the synthetic consensus Env, C.CON, and wild-type C, are shown in Figure 5. Comparison of the glycan profiles of wild-type C and C.CON shows similarities as well as differences throughout the Env. The glycan profile of wild-type C and C.CON are different in the following glycosylation sites in the corresponding Env regions: N275 and N289 in the C2 region, N301 in the V3 loop, N339 in the C3 region, N386 at the beginning of the V4 loop, N442 in the C4 region. These glycosylation sites have more high mannose glycans (%glycan ≥ 50) in C.CON compared to wild-type C. On the other hand, the glycan profiles on the conserved glycosylation sites, N230, N241, N262, and N332 in the C2 and C3 regions, for wild-type C and C.CON are the same. These glycosylation sites are populated with high mannose glycans. Glycosylation site at N234 in C.CON was not present in wild-type C due to a mutation.

Figure 5.

Summary of glycan compositions (in percent) on the identified glycosylation site. Glycan compositions were broadly categorized into two classes (see text). Unprocessed glycans include high mannose glycans while processed glycans include hybrid and complex type glycans.

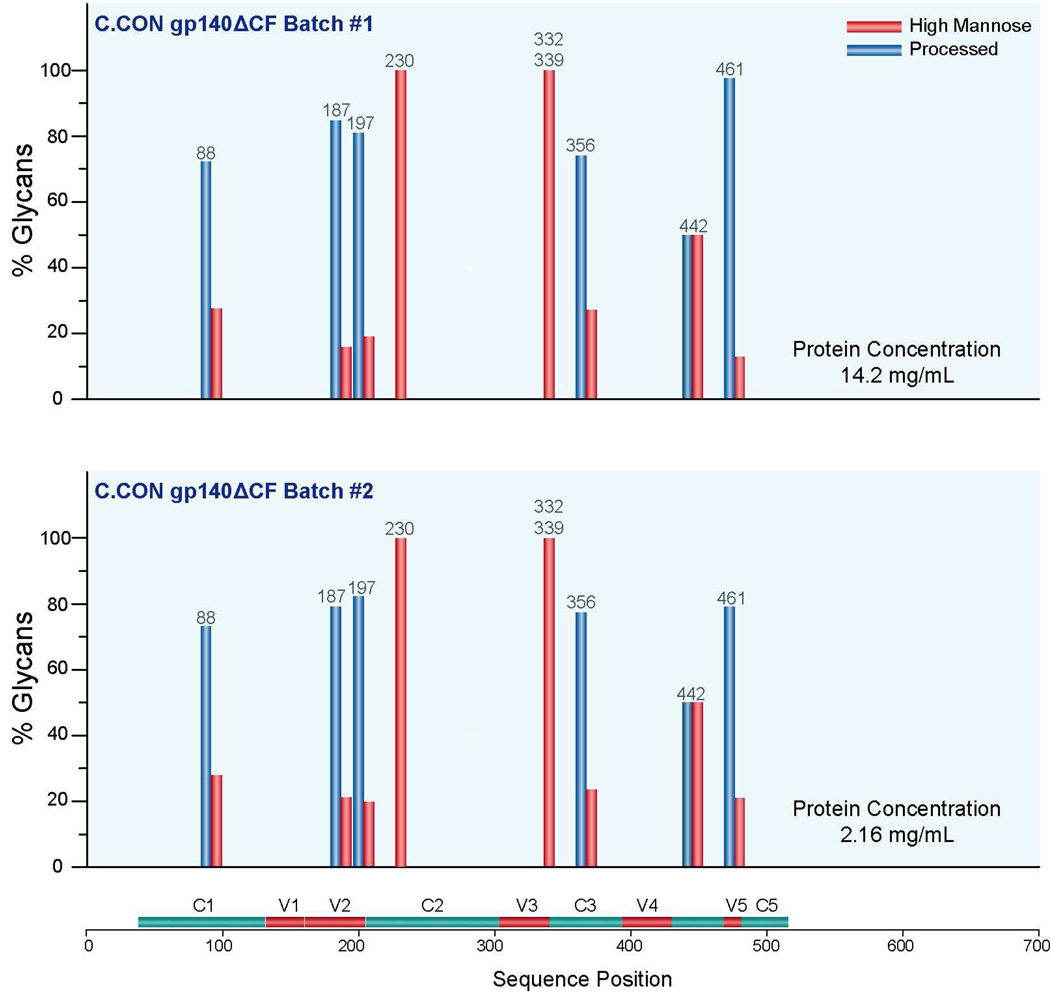

In an effort to determine the minimum concentration of Env needed for analysis and the variations in glycosylation profile between batches of the same protein, glycosylation analysis of C.CON from two different batches with different concentrations following the same procedure described above was performed. One batch (C.CON #1) has a protein concentration of 14.2 mg/mL and the other batch (C.CON #2) has a protein concentration of 2.16 mg/mL as determined from their absorbance. These two batches were produced from different rVV-infected 293T cell cultures. A 100% glycosylation coverage of the glycosylated peptides was obtained for C.CON #1 and 48% for C.CON #2. Based on these results, and previous analyses we have conducted on Envs with different initial concentrations, we determined that an initial protein concentration >4 mg/mL is needed for complete coverage. This corresponds to a concentration of about 28 µM. Due to these requirements, this type of analysis is well suited for analyzing recombinant protein but possibly not well suited for analyzing Env isolated off virions if present in low concentration.

To examine the variation in glycan profile between these samples, glycan profiles of the eight most abundant glycopeptides in C.CON #1 were compared with the same eight most abundant glycopeptides in C.CON #2. A bar graph showing the glycan profiles of C.CON #1 and C.CON #2 in Figure 6 shows remarkably similar glycan profiles. The similarity of these profiles reinforces the fact that differences in glycan profiles are not related to the analytical conditions, the starting concentration of the sample, or the particular batch of cells used. Rather, differences in the bar graphs, such as those in Figure 5 indicate fundamental differences in the proteins. We have not yet tested whether or not changing the cell line that produces the protein would change the glycosylation profile. However, it is fully reasonable to expect that a different cell line could generate protein with modified glycosylation and that a modified glycoprotein may have a different immunological response.

Figure 6.

Glycan compositions (in percent) of the eight most abundant glycopeptides from C.CON gp140 ΔCF samples produced from two different batches.

Discussion

Clade C is the most rapidly spreading form of HIV-1, and this is the first analysis of the glycan profiles of any clade C Env protein. The data reported here extends our previous work in comparing glycosylation profiles with immunogenicity data for two other Env immunogens. It is well established that Env glycosylation is crucial in host immune regulation by affecting protein conformation as well as masking key protein epitopes22,30,41–45. Thus, assessing the differences and similarities in glycosylation between Env immunogens and distinguishing the profiles that correlate to Env immunogenicity is important in the improvement of vaccine design and efficacy. We established previously by a glycopeptide-based mass mapping approach that a good immunogen has a glycosylation profile with higher levels of high mannose glycans surrounding the immunogenic V3 region and higher levels of unutilized glycosylation sites27. When compared with immunology data, such a glycosylation profile correlates to better induction of both humoral and cellular immunity in small animal and primate models33,46. Clearly, how well an Env immunogen induces a potent immune response depends in part on the number of PNG sites, the degree of glycosylation site occupancy, and the glycan motifs populating each glycosylation site. However, these elements vary considerably between isolates and across clades, due to the HIV genetic diversity14,47,48. Thus, evaluation of Env glycosylation is in part crucial in establishing the utility of Env immunogens as potential components of a vaccine regimen. As an important step in understanding the influence if glycosylation to immunogenecity the following questions must be addressed: (1) What are the interclade differences and similarities in the glycosylation profiles? (2) How does the glycosylation profile of a group M global consensus (CON-S) differ from a clade-specific consensus?

Interclade Variations in Glycosylation Site Occupancy and Env Immunogenecity

We characterized the glycosylation of two clade C Env immunogens to determine the variations in glycosylation profiles and correlate our results with immunology data. We showed that C.CON and wild-type C differ by 17% in amino acid sequence, which is well within the interclade genetic variation (>15%)47. The relative difference in Env amino sequence determines the number of PNG sites on the Env. In fact, for the collection of gp120 protein sequences in the Los Alamos HIV sequence data repository, the number of PNG sites ranges from 18–33, with a median of 2530,48. The relative variation in the number of PNG sites is due to an insertion or deletion specifically in the hypervariable regions48. In general, a loss of a PNG site and/or lesser degree of glycosylation site occupancy will impose lesser constraints on neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) to access key neutralization epitopes. Our results show that the consensus protein, C.CON, has more unutilized glycosylation sites compared to the wild-type C (See Table 1). There are seven unutilized sites for C.CON and two for wild-type C. Most of these unutilized glycosylation sites for both clade C Envs are conserved. Six of the seven unutilized sites for C.CON and the two unutilized sites for wild-type C are variably utilized. One of the seven unutilized sites for C.CON is not glycosylated at all. This non-glycosylated site is located at N625 in the transmembrane region and the same site is utilized in wild-type C. Glycosylation sites that are variably unutilized are located in the V1/V2 loops (N133, N156, and N187), V4 loop (N386 and N397) and transmembrane region (N616) for C.CON and in the V1/V2 region (N156 and N184) for wild-type C. Variably unutilized PNG sites that are not conserved between the two Envs (shown in green boxes in Figure 1) are either deleted or mutated in either C.CON or C.97ZA012. These PNG sites are located at N184 in the V2 loop for wild-type C and at N616 in the transmembrane region for C.CON. Corresponding glycosylation sites at N187 in wild-type C and at N616 in C.CON were deleted.

How these open glycosylation sites may influence the Env immunogenicity depend on their location and their distribution in the Env structure. More unutilized glycosylation sites in regions where neutralization epitopes are located would lead to better Env immunogenicity. Indeed, removal of glycans in the variable loops is known to increase neutralization sensitivity49. The variably unutilized glycosylation sites at N133, N156, and N187 for C.CON and N156 and N184 for wild-type C lie at the base of the V1/V2 loop and are proximal to the two disulfide bonds that define the V1/V2 loop. Glycosylation on these sites could affect the flexibility as well as the orientation of the V1/V2 loop. Additionally, it has been proposed that there is interaction between V1/V2 and V3 loops wherein glycans play a role in helping to protect the CD4 binding site against NAbs50. Thus, absence of glycans in the V1/V2 loop would make the CD4 binding site vulnerable to NAbs. Direct comparison of the glycosylation site occupancy between C.CON and wild-type C in the V1/V2 loop shows difference in glycosylation site occupancy at sites N133 and N187. Both of these sites are variably unutilized in C.CON but fully utilized in wild-type C. While the wild-type C Env nominally has an extra glycosylation site at N184 that is absent in C.CON, this site is only variably unutilized, which significantly mitigates its impact. Clearly, C.CON is less glycosylated compared to wild-type C. Less glycosylation in the V1/V2 loop in C.CON promotes better accessibility of Abs to the CD4 binding site.

Apart from the V1/V2 loop, there are two more variably unutilized PNG sites in C.CON at N386 and N397 in the V4 loop. N386 is located at the base of the V4 loop and proximal to the chemokine receptor binding site, while N397 is within the V4 loop51–55. The lack of glycans at these sites could allow for better accessibility of antibodies to the critical CD4 induced epitopes. Finally, the highly conserved glycosylation in the transmembrane region has been reported to effectively shield the underlying epitopes in this region56. The lack of glycan at N625 in C.CON could increase the neutralization sensitivity to this region, once it is exposed.

Interclade Variations in Glycan Profiles and Env Immunogenecity

While there is mounting evidence that the lack of glycans on PNG sites or the absence of a PNG site is a good measure to differentiate a good immunogen from a poor immunogen, the diverse array of glycans decorating the glycosylation sites can also be characterized and correlated to the immunogenicity of different Envs. Indeed, the type of prevalent glycans on each glycosylation site and how they are distributed throughout the Env could help define the glycosylation pattern that potentially influences Env immunogenecity. This study takes a small step toward unraveling the correlation between glycosylation profiles and immunogenicity by comparing the profiles of two clade C proteins. MS analysis of the glycan profiles of wild-type C and C.CON shows distinct difference in the glycan patterns between the clade C Envs (Figure 5). C.CON generally displays a higher population of high mannose glycans compared to wild-type C in the C2 region, V3 loop, C3 region, V4 loop, and C4 region. When mapped onto the gp120 structure, these glycosylation sites (N275, N289, N301, N339, N386, and N442) are located in the outer domain of gp120 and are within the 2G129,11,12,57,58 and the IgG1 b12 binding sites59. Considering that high mannose glycans promote proper Env folding and stabilize protein conformation60–62, it is likely that the glycosylation sites with high mannose in C.CON provide conformational stability in this region. This stabilization could enhance the ability of C.CON to elicit a wider breadth of NAbs to this region. This interclade variation in glycosylation reflects a difference in structural conformation in this region between the two clade C Envs. The higher level of high mannose glycans in C.CON indicates a highly structurally conserved Env that in part correlates with its ability to induce wide breadth of NAbs compared to wild-type C63.

Clade C Specific Glycosylation Patterns that Could Correlate to Enhanced Infectivity

In addition to the differences in the glycan profile between the two clade C Envs, four conserved glycosylation sites in the C2 and C3 regions of C.CON and wild-type C have similar glycan patterns, specifically at N230, N241, N262, and N332 which predominantly bear high mannose glycans. Studies have shown that HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV are transmitted efficiently to T-cells when their respective Envs have high levels of high mannose glycans29. This process is mediated by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR, which are calcium dependent C-type lectins that facilitate HIV transmission and dissemination64,65. These C-type lectins have high affinity and binding specificity to high mannose glycans66–69. With this precedent, it is possible that the clade-specific glycan pattern in clade C Env observed in this study (mainly, the presence of high mannose glycans in the C2 region) is responsible for efficient transmission of clade C viruses through mediation by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. This glycan profile is remarkably conserved within clade C Env immunogens analyzed in this study and possibly important in modulating clade C infectivity. While the role of this glycosylation pattern in the Env’s immunology remains to be determined, future studies could focus in elucidating intraclade glycosylation variations that modulate DC-SIGN binding and infectivity.

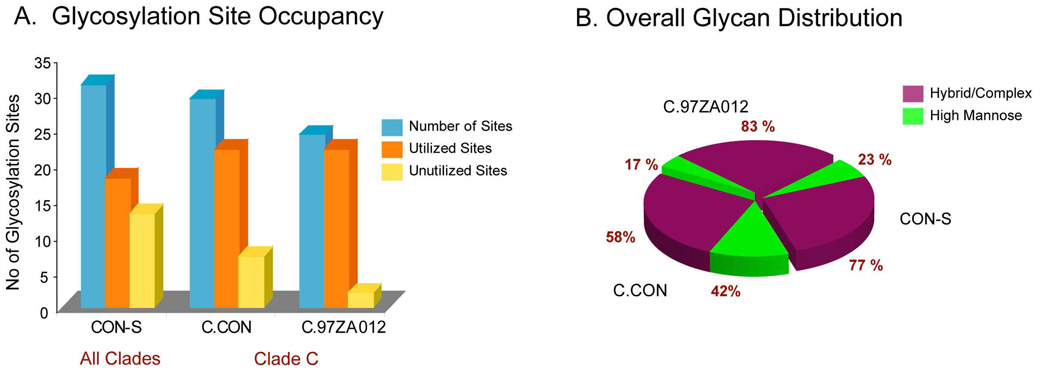

Glycosylation Profile of Two Consensus Immunogens

How does the overall glycosylation profile of the clade consensus, C.CON, compare to the group M consensus, CON-S? Figure 7A and 7B show a composite representation of the overall glycosylation profile that includes the unutilized glycosylation sites as well as the glycan profiles for CON-S, C.CON, and wild-type C. The data presented for CON-S were obtained from our previous study27,28. Comparison of the overall glycosylation profiles reveals that C.CON reflects a similar glycosylation pattern as CON-S. Both consensus Envs have high levels of unutilized glycosylation sites and high levels of high mannose glycans surrounding the immunogenic V3 region. CON-S has a higher number of total PNG sites and unutilized glycosylation sites compared to C.CON (Figure 7A). Additionally, the unutilized glycosylation sites and the respective distribution of these sites in the Env regions in C.CON follow a similar trend observed in CON-S. These unutilized glycosylation sites are well conserved in both of the consensus Envs, indicating a trend for more open glycosylation sites for good Env immunogens.

Figure 7.

(A). Summary of glycosylation site occupancy for C.CON gp140ΔCF, C.97ZA012 gp140 ΔCFI, and CON-S gp140ΔCFI. Glycosylation site occupancy data for CON-S was obtained from our previous study. (B). Composite distribution of the type of glycans in C.CON gp140ΔCF, C.97ZA012 gp140ΔCFI, and CON-S gp140ΔCFI.

When all glycosylation sites are considered for CON-S, C.CON, and wild-type C, C.CON has higher levels of high mannose glycans than the clade-generic consensus Env, CON-S (Figure 7B). This difference likely reflects clade specific differences, where clade C proteins have inherently more high mannose glycans in the C2 region. The fact that this is a clade-specific difference is further supported by data that shows the clade C wild type Env protein had a much higher level of high-mannose glycans, compared to the clade B wild-type Env protein, JR-FL (data not shown.) Lastly, taking into consideration the glycan profiles between C.CON and CON-S, the utilized glycosylation sites have high levels of high mannose glycans for both consensus Env immunogens between the C2 region and the beginning of the C3 region. This consensus Env glycosylation feature indicates that Env conformation in these regions is conserved for both C.CON and CON-S. These data correlate well with immunology data where both the clade consensus and group M consensus Env immunogens elicited wide breadth of NAbs when used as vaccine components in small animal models63.

Conclusions

Mass spectrometry-based glycosylation profiling of two rVV expressed clade C HIV-1 Envs described in this study provides an informative approach to differentiate glycosylation profiles of Env immunogens. A combination of MALDI-MS and LC/ESI FTICR-MS with liquid chromatography, tandem MS analyses, and web-based analysis tools were used to map the glycan motifs as well as glycosylation site occupancy in a glycosylation site-specific fashion. Our results show that the consensus protein, C.CON, has more unutilized glycosylation sites and a high level of high mannose glycans in the region surrounding the immunodominant V3 loop but also in the C4 region and at the beginning of V4 loop. Interestingly, the glycosylation profile of C.CON shows some degree of similarity to another consensus immunogen, CON-S, derived from the global group M env sequence. The common glycosylation features between C.CON and CON-S indicate that consensus Envs have similar functionally conserved Env conformations and therefore similar immunogenicity63. It is also important to note that our results also reveal a clade-specific glycosylation pattern in the C2 and the C3 regions.

While an effective vaccine against HIV infection remains elusive, considerable progress has been made so far in understanding the immunopathogenesis of HIV. The Env is a major target for vaccine design and one Env-based immunogen design strategy is delineating the Env glycosylation and modifying the glycosylation to improve the breadth of NAb coverage27,44,49,50,63,70–74. Thus, a systematic comparison of interclade and/or intraclade glycosylation profiles between Env immunogens may prove useful in distinguishing a definitive glycosylation patterns that positively contributes to Env’s immunogenicity and the knowledge gained from this study will certainly enhance vaccine design,

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1GM077226, PO1AI61734, and a collaboration from the AIDS Vaccine Development Grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to Barton F. Haynes. We would also like to thank the Applied Proteomics Laboratory at KU for instrument time.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Complete list of the glycopeptide compositions for C.CON gp140 ΔCF and C.97ZA012 gp140 ΔCFI. (Supplementary Tables 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.MMWR. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly Report. 2006;55(31):841. [PubMed]

- 2.McKnight A, Aasa-Chapman MM. Curr. HIV Res. 2007;5(6):554–560. doi: 10.2174/157016207782418524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS; 2008 Report on the Global Aids Epidemic. 2008

- 4.Hemelaar J, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Osmanov S. AIDS. 2006;20(16):W13–W23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247564.73009.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geretti AM. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000200293.45532.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor BS, Sobieszczyk ME, McCutchan FE, Hammer SM. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(15):1590–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michler K, Connell BJ, Venter WDF, Stevens WS, Capovilla A, Papathanasopoulos MA. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2008;24(5):743–751. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tscherning C, Alaeus A, Fredriksson R, Bjorndal A, Deng H, Littman DR, Fenyo EM, Albert J. Virology. 1998;241(2):181–188. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bures R, Morris L, Williamson C, Ramjee G, Deers M, Fiscus SA, bdool-Karim S, Montefiori DC. J. Virol. 2002;76(5):2233–2244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2233-2244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Mokili JL, Muldoon M, Denham SA, Heil ML, Kasolo F, Musonda R, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Korber BT, Allen S, Hunter E. Science. 2004;303(5666):2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Derdeyn CA, Morris L, Williamson C, Robinson JE, Decker JM, Li YY, Salazar MG, Polonis VR, Mlisana K, Karim SA, Hong KX, Greene KM, Bilska M, Zhou JT, Allen S, Chomba E, Mulenga J, Vwalika C, Gao F, Zhang M, Korber BTM, Hunter E, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. J. Virol. 2006;80(23):11776–11790. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01730-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Zolla-Pazner S, Katinger H, Petropoulos CJ, Burton DR. J. Virol. 2004;78(23):13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelbrecht S, de Villiers T, Sampson CC, Megede JZ, Barnett SW, van Rensburg EJ. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2001;17(16):1533–1547. doi: 10.1089/08892220152644241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gnanakaran S, Lang D, Daniels M, Bhattacharya T, Derdeyn CA, Korber B. J. Virol. 2007;81(9):4886–4891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01954-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rademeyer C, Moore PL, Taylor N, Martin DP, Choge IA, Gray ES, Sheppard HW, Gray C, Morris L, Williamson C. Virology. 2007;368(1):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Luo LZ, Rasool N, Kang CY. J. Virol. 1993;67(1):584–588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.584-588.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Land A, Braakman I. Biochimie. 2001;83(8):783–790. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geijtenbeek TB, van KY. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;276:31–54. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-06508-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chohan B, Lang D, Sagar M, Korber B, Lavreys L, Richardson B, Overbaugh J. J. Virol. 2005;79(10):6528–6531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6528-6531.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Curlin ME, Diem K, Zhao H, Ghosh AK, Zhu H, Woodward AS, Maenza J, Stevens CE, Stekler J, Collier AC, Genowati I, Deng W, Zioni R, Corey L, Zhu T, Mullins JI. Virology. 2008;374(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reitter JN, Means RE, Desrosiers RC. Nat. Med. 1998;4(6):679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, Katinger H, Parren PW, Robinson J, Van RD, Wang L, Burton DR, Freire E, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA, Arthos J. Nature. 2002;420(6916):678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. Nature. 2003;422(6929):307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geyer H, Holschbach C, Hunsmann G, Schneider J. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263(24):11760–11767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizuochi T, Matthews TJ, Kato M, Hamako J, Titani K, Solomon J, Feizi T. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265(15):8519–8524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X, Borchers C, Bienstock RJ, Tomer KB. Biochemistry. 2000;39(37):11194–11204. doi: 10.1021/bi000432m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Go EP, Irungu J, Zhang Y, Dalpathado DS, Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Desaire H. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7(4):1660–1674. doi: 10.1021/pr7006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irungu J, Go EP, Zhang Y, Dalpathado DS, Liao HX, Haynes BF, Desaire H. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008;19(8):1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin G, Simmons G, Pohlmann S, Baribaud F, Ni H, Leslie GJ, Haggarty BS, Bates P, Weissman D, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. J. Virol. 2003;77(2):1337–1346. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1337-1346.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Gaschen B, Blay W, Foley B, Haigwood N, Kuiken C, Korber B. Glycobiology. 2004;14(12):1229–1246. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakrabarti BK, Kong WP, Wu BY, Yang ZY, Friborg J, Ling X, King SR, Montefiori DC, Nabel GJ. J. Virol. 2002;76(11):5357–5368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5357-5368.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao F, Weaver EA, Lu Z, Li Y, Liao HX, Ma B, Alam SM, Scearce RM, Sutherland LL, Yu JS, Decker JM, Shaw GM, Montefiori DC, Korber BT, Hahn BH, Haynes BF. J. Virol. 2005;79(2):1154–1163. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1154-1163.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Xia SM, Brock ME, Scearce RM, Vanleeuwen S, Alam SM, McAdams M, Weaver EA, Camacho Z, Ma BJ, Li Y, Decker JM, Nabel GJ, Montefiori DC, Hahn BH, Korber BT, Gao F, Haynes BF. Virology. 2006;353(2):268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakrabarti S, Sisler JR, Moss B. Biotechniques. 1997;23(6):1094–1097. doi: 10.2144/97236st07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moss B, Earl PL. Overview of the Vaccinia Virus Expression System. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Strul K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 60. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1998. 16.15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Go EP, Desaire H. Anal. Chem. 2008;80(9):3144–3158. doi: 10.1021/ac702081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Go EP, Rebecchi KR, Dalpathado DS, Bandu ML, Zhang Y, Desaire H. Anal. Chem. 2007;79(4):1708–1713. doi: 10.1021/ac061548c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irungu J, Go EP, Dalpathado DS, Desaire H. Anal. Chem. 2007;79(8):3065–3074. doi: 10.1021/ac062100e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper CA, Gasteiger E, Packer NH. Proteomics. 2001;1(2):340–349. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200102)1:2<340::AID-PROT340>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenouillet E, Gluckman JC, Jones IM. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994;19(2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudd PM, Dwek RA. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;32(1):1–100. doi: 10.3109/10409239709085144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Science. 1998;280(5371):1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Moore JP, Nabel GJ, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt RT. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5(3):233–236. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santra S, Korber BT, Muldoon M, Barouch DH, Nabel GJ, Gao F, Hahn BH, Haynes BF, Letvin NL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(30):10489–10494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803352105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, Novitsky V, Haynes B, Hahn BH, Bhattacharya T, Korber B. Science. 2002;296(5577):2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korber B, Gaschen B, Yusim K, Thakallapally R, Kesmir C, Detours V. Br. Med. Bull. 2001;58:19–42. doi: 10.1093/bmb/58.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binley JM, Wyatt R, Desjardins E, Kwong PD, Hendrickson W, Moore JP, Sodroski J. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1998;14(3):191–198. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwick MB, Kelleher R, Jensen R, Labrijn AF, Wang M, Quinnan GV, Jr, Parren PW, Burton DR. J. Virol. 2003;77(12):6965–6978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6965-6978.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koch M, Pancera M, Kwong PD, Kolchinsky P, Grundner C, Wang L, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski J, Wyatt R. Virology. 2003;313(2):387–400. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Sattentau QJ, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. J. Virol. 2000;74(4):1961–1972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1961-1972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzuto C, Sodroski J. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2000;16(8):741–749. doi: 10.1089/088922200308747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rizzuto CD, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski J. Science. 1998;280(5371):1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, Sweet RW, Robinson J, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski JG. Nature. 1998;393(6686):705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuste E, Bixby J, Lifson J, Sato S, Johnson W, Desrosiers R. J. Virol. 2008;82:12472–12486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01382-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanders RW, Venturi M, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Katinger H, Lloyd KO, Kwong PD, Moore JP. J. Virol. 2002;76(14):7293–7305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7293-7305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gray ES, Moore PL, Pantophlet RA, Morris L. J. Virol. 2007;81(19):10769–10776. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01106-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van RD, Xiang SH, Yang X, Zhang MY, Zwick MB, Arthos J, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Nabel GJ, Kwong PD. Nature. 2007;445(7129):732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyss DF, Choi JS, Li J, Knoppers MH, Willis KJ, Arulanandam ARN, Smolyar A, Reinherz EL, Wagner G. Science. 1995;269(5228):1273–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.7544493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jitsuhara Y, Toyoda T, Itai T, Yamaguchi H. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2002;132(5):803–811. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamaguchi H. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 2002;14(77):139–151. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao F, Liao HX, Hahn BH, Letvin NL, Korber BT, Haynes BF. Curr, HIV Res. 2007;5(6):572–577. doi: 10.2174/157016207782418498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu L, KewalRamani VN. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6(11):859–868. doi: 10.1038/nri1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lekkerkerker AN, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TBH. Curr. HIV Res. 2006;4(2):169–176. doi: 10.2174/157016206776055020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feinberg H, Mitchell DA, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Science. 2001;294(5549):2163–2166. doi: 10.1126/science.1066371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hong PW, Flummerfelt KB, de PA, Gurney K, Elder JH, Lee B. J. Virol. 2002;76(24):12855–12865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12855-12865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hong PW, Nguyen S, Young S, Su SV, Lee B. J. Virol. 2007;81(15):8325–8336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01765-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell DA, Fadden AJ, Drickamer K. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(31):28939–28945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haynes BF, Montefiori DC. Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 2006;5(4):579–595. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Humbert M, Dietrich U. AIDS Rev. 2006;8(2):51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pantophlet R, Burton DR. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:739–769. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saunders CJ, McCaffrey RA, Zharkikh I, Kraft Z, Malenbaum SE, Burke B, Cheng-Mayer C, Stamatatos L. J. Virol. 2005;79(14):9069–9080. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9069-9080.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolk T, Schreiber M. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;195(3):165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00430-006-0016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.