Abstract

What makes us human? Specialists in each discipline respond through the lens of their own expertise. In fact, ‘anthropogeny’ (explaining the origin of humans) requires a transdisciplinary approach that eschews such barriers. Here we take a genomic and genetic perspective towards molecular variation, explore systems analysis of gene expression and discuss an organ-systems approach. Rejecting any ‘genes versus environment’ dichotomy, we then consider genome interactions with environment, behaviour and culture, finally speculating that aspects of human uniqueness arose because of a primate evolutionary trend towards increasing and irreversible dependence on learned behaviours and culture — perhaps relaxing allowable thresholds for large-scale genomic diversity.

After millennia of speculation, we can approach the question of what makes us human in a scientific manner, considering all the dimensions represented by many relevant disciplines. Studies of human genetic and genomic differences from our closest evolutionary relatives have much to offer. The evolutionary relatedness of humans and the African ‘great apes’ (now reclassified and grouped with humans and orangutans as hominids) was predicted by Huxley and Darwin1,2, and given molecular credence a century later by investigators such as Sarich, Wilson and Goodman3,4. Since the late 1800s, there has been an increasing interest in comparing humans with non-human hominids (NHHs), particularly chimpanzees, our closest living evolutionary relatives5. Initial studies involved anatomical and skeletal analyses of dead chimpanzees. Then came behavioural studies in captivity, particularly by Kohts, Köhler and Yerkes — and the field observations of Goodall, Imanishi, Nishida and others5. Much additional data concerning the behaviour, cognition, physiology and pathology of chimpanzees and other NHHs has since accumulated, showing how remarkably similar we are, and yet how different.

Early molecular comparisons by King and Wilson6 showed that the problem was going to be difficult, as all of the protein sequences they studied were practically identical. Ironically, this classic paper might have diminished enthusiasm for further molecular comparisons, because of the fear that significant differences would be difficult to determine. This attitude changed in the 1990s with the discovery of specific genetic differences between humans and other hominids7-9, and there were calls for the sequencing of the NHH genomes10-12, including a biomedical rationale13. Subsequent sequencing of the chimpanzee genome14 spawned many molecular comparisons between humans and other hominids, some aspects of which are cited throughout this Review. The possibility of obtaining genomic information from our closest extinct evolutionary cousins, the Neanderthals15,16, has further raised hope of elucidating the genetic components of what makes us human.

Of course, studies of genotypic variation need to be related to phenotypic differences12,17 (BOX 1); however, the gap between phenomic and genomic studies remains large. It is time to set aside divisive and unproductive ‘genes versus environment’ arguments18, and explicate the human phenotype as the outcome of complex and ongoing interactions among genomes and the environment — and the effects of behaviour and cultural activities. Two approaches are taken here. The first is a genome-wide one, in which we consider the genomic and other molecular mechanisms that could be involved in uniquely human features, surveying roles of protein-coding changes, gene expression differences and genomic structural variation. The second approach considers potential contributions of genomic changes to organ-system differences. In both instances, we have selected examples largely from our own work as representative of the spread of topics and results in this field. Investigations in this area also have potential implications for understanding uniquely human aspects of disease processes13,19,20.

Box 1 Human uniqueness — what do we need to explain?

Ultimately, it is necessary to understand uniquely human aspects of phenotype in the context of genotypic differences from the non-human hominids (NHHs). Many lists of such differences have been published and it is becoming increasingly clear that several of these differences are relative rather than absolute. Some commonly discussed features are relative brain size, hairless sweaty skin, striding bipedal posture, long-distance running, ability to learn to swim, innate ability to learn languages in childhood, prolonged helplessness of the young, ability to imitate and learn, inter-generational transfer of complex cultures, awareness of self and of the past and future, theory of mind, increased longevity, provisioning by post-menopausal females, difficult childbirth, cerebral cortical asymmetry and so on (see ref. 20 for a more extended listing).

The type of approach proposed in this Review is necessary in order to eventually correlate the genotype with these and many other phenotypic differences. In this regard it is striking that although we know a lot about the human phenotype (that is, the human phenome), remarkably little detail is known about the phenome of the NHHs. Thus, a decade ago we proposed a ‘great ape phenome project’17 that would attempt to identify all of these differences, with the goal of understanding which are indeed uniquely human characteristics.

Although this concept has gained interest, the opportunity to study the phenome of the NHHs is now greatly reduced, owing to recent decisions by the National Institutes of Health and other research agencies around the world that will markedly restrict or ban research on chimpanzees, and also stop all further breeding in captivity175. It is ironic that this ban is occurring just when the greatest opportunity exists in terms of emerging genomic information. Although there are clearly special ethical issues to be considered when exploring the phenotype of NHHs, it seems reasonable to suggest that studies that can be ethically done in humans can also be done in other hominids, of course with appropriate mechanisms for protection of individual rights and dignity175. Without such an approach, we will be left with piecing together limited information on the NHHs, and arbitrarily trying to relate them to our extensive knowledge of the human phenome174.

As it is unlikely that we will fully answer questions about human uniqueness soon, we will be somewhat speculative and bold in the last part of this Review, closing by presenting a somewhat contrarian view of human genome dynamics. These final sections are meant to provoke discussion and debate. We will suggest that some of the common ‘rules’ of Darwinian genomic evolution through natural selection do not fully apply in humans, and that primate genomes (and the human genome in particular) have partially escaped such mechanisms because of buffering by culturally transmitted learned behaviours.

Sources of molecular variation

Going beyond the ‘1% difference’

Remarkable similarities of known human and chimpanzee protein sequences initially led to the suggestion that significant differences might be primarily in gene and protein expression, rather than protein structure6. Further analysis of alignable non-coding sequences affirmed this ~1% difference. However, the subsequent identification of non-alignable sequences that were due to small- and large-scale segmental deletions and duplications21-23 showed that the overall difference between the two genomes is actually ~4%. Also, apart from coding regions (which make up ~2% of the entire genome), there is another ~2% of the two non-coding genomes that is highly conserved, but the function of which remains mostly unknown24. More recently it has emerged that many genes have undergone differential deletions or duplications in both humans and chimpanzees25-28. The discovery of various non-coding RNAs and the increasing appreciation of the role of post-translational modifications and epigenetic factors add even more complexity when translating genotype to phenotype. Together, these findings have dashed the hope that it would be simple to determine the key genetic differences between humans and our closest evolutionary relatives, that is, the genomic aspects of ‘what makes us human’.

Differences in protein-coding sequences

Classic analyses of adaptive evolution focused largely on regions of the genome that code for protein products, using well defined metrics based on the ratio of functional changes (amino-acid changes, Ka) to neutral changes (typically based on the surrounding non-coding variation rate, Ki, or the rate of synonymous changes, Ks). Genome-wide analysis of positive selection in the human versus chimpanzee by organ system revealed the anticipated result that more widely expressed or ‘housekeeping’ genes have a lower Ka/Ki ratio, as they are under more functional constraint than genes with more restricted or organ-specific expression patterns29,30. There has been some controversy around whether brain genes are under more constraint than genes in non-neural tissues30-34, and a recent paper argues that there are large numbers of selected amino-acid differences between humans and chimps35. A combination of methodological issues, as well as differences in interpretation, probably account for these apparent discrepancies, highlighting the current state of confusion around the role of protein sequence divergence in the evolution of human brain function in particular. In some cases, the conclusions drawn are probably due to the specific comparisons that were made (for example, the choice of genes or outgroup)36. More comprehensive analyses, using several metrics of brain specificity and a more complete list of genes, support an increase in functional constraint on hominid brain genes relative to most other tissues30,32-34,37.

Although using single nucleotide changes in coding sequence to assess genome evolution is well documented in the literature, one must be cautious about its general applicability24,38. The classic approach treats all exons as functionally equal, which can be a faulty assumption. For example, rapid evolution within a single domain of a protein can be missed if its other domains are undergoing purifying selection39. Thus it is preferable to use more recent methods that can detect positive selection on a small number of sites40. These concerns do not invalidate studies that are based on classic Ka/Ks or Ka/Ki ratios, which deservedly continue to have an important role in molecular analyses of genome evolution — but we should be aware of their potential limitations.

Over half of mammalian genes are alternatively spliced, several in a lineage-specific manner41, and mutations that change splicing are significant causes of Mendelian-inherited disease in humans. However, the potential adaptive regulation of splicing42-44 is not addressed in many studies of protein-sequence evolution. No detailed comparison of alternative splicing between humans and NHHs has been carried out. A recent candidate is neuropsin (also known as kallikrein-related peptidase 8, KLK8), which is a secreted serine protease preferentially expressed in the central nervous system and is involved in learning and memory. The longer spliced form of this mRNA is expressed only in humans, and not in non-human primates (NHPs), owing to a human-specific T-to-A mutation44.

Functionally important sequences might not encode proteins

There is no a priori reason to believe that protein-coding regions are more relevant to hominid evolution than changes in enhancers, promoters, 3′ UTRs45, non-coding RNAs46-48 or even more cryptic regulatory regions49-51. Indeed, many deleterious mutations have arisen in gene control elements during the evolution of humans and chimpanzees45. The calculated rate of adaptive evolution (positive selection) depends on the neutral background rate. Although this has been a powerful approach, which sequence is truly non-functional and thus an appropriate measure for neutrality is currently unknown52. Thus, intronic regions, synonymous coding changes and surrounding non-coding regions that we now know to be functionally relevant53-54 have been used to assess the rate of neutral evolution. Current estimates of adaptive protein evolution, therefore, might not be accurate in some cases, nor provide a complete picture of genome evolution. This is highlighted by the recent identification of 49 highly conserved non-coding sequences showing significant nucleotide divergence in humans (human accelerated regions; HARs), and one of which (HAR-1) encodes a novel non-coding RNA highly expressed during brain development47. Almost 1,000 human non-coding microRNAs (miRNAs) are listed in the miRBase at the Sanger Institute; many miRNAs are species specific, including those identified only in primate genomes, such as chimpanzee or human46. The extent to which non-coding RNAs regulate gene expression in mammals was unknown 10 years ago, and still almost nothing is known about primate- or human-specific miRNA selection or function. More surprises will require us to integrate new concepts of gene function and regulation49 into the assessment of human evolution55.

Differences in mRNA and protein expression

The idea that regions controlling mRNA expression are more important than coding sequences6 gave theoretical support for studies comparing genome-wide mRNA expression across different tissues between humans and chimpanzees56-60, particularly in the brain. As well as relating gene expression to organ-specific phenotypes, such expression studies can also provide an important platform for novel phenotype discovery, for example, by identifying molecular differences in specific cell types60,61.

Although microarray-based studies of inter-species gene expression are affected by many technical or methodological issues (reviewed in REFS 61-64), they revealed a few main themes. First, there is an apparent acceleration in the evolution of brain-enriched genes in humans versus chimpanzees, relative to other tissues29,57,60,65. This finding has been interpreted to signify positive selection, but is also consistent with relaxation of constraint66. A second, related observation is that in the human lineage there are more increases in gene expression than decreases60,65. This could indicate a general upregulation of brain energy metabolism in humans, a feature consistent with the expansion of the neocortex in the human lineage59,60. Third, a neutral model has been proposed to account for much of the gene expression changes in the brain, because there is more variation in non-nervous-system enriched genes than in brain-enriched genes67 (BOX 2).

Box 2 High degree of purifying selection in brain-expressed genes.

Why are coding-sequence changes in brain genes under a larger degree of purifying selection than in other tissues? The reason for this is not immediately clear as a wide range of brain function supports life to reproductive age in humans. Perhaps the complexity of brain function places limits on adaptive changes in sequence. Here, the supposition is that the rapid expansion of cortical surface area, and the subsequent interconnections between higher-order association areas from multiple brain regions that are necessary to support higher cognition, places a constraint on the sequence of involved genes.

But this notion, which is based on single nucleotide changes in protein-coding sequence, has to be reconciled with the CNV data, because CNVs in humans seem to be enriched among genes involved in neurodevelopmental processes. It is also possible that the actual selection of brain-enriched genes for analyses might be limited by tissue heterogeneity60; this might mean that the brain-enriched genes identified by microarrays29 are those with moderately high levels of expression across many brain regions, and thus the analyses would be biased towards genes involved in fundamental neural cellular functions. Methods that are based on deep library sequencing or single-cell analysis will be needed to address this issue more conclusively. It would be ironic if, overall, increased purifying selection of protein-coding regions on human brain genes is a necessary consequence of the phenotypic adaptations that have led to our social–cultural flexibility, which might be buffering other genomic changes. Of course, any overall metric of selection on the functional genome should consider the role of structural variation and non-coding regions, which might significantly alter estimates of the direction of selection.

In fact, of all the organs studied, the strongest evidence for positive selection in gene expression and protein sequence is observed in the testes67, not in the brain. However, important methodological issues, such as tissue heterogeneity62 and the manner in which differential gene expression is calculated (for example, the number of genes versus the sum of differential expression values), cloud the interpretation of these data64. Additionally, analyses by other investigators do not support a pervasive role for neutral evolution in hominid brain evolution68,69. Nevertheless, the neutral theory sets the context for the development of methods that distinguish between neutral and adaptive evolution on a gene-by-gene basis, as discussed later and in BOX 2.

Epigenetic differences

Few studies have assessed epigenetic changes specific to the human lineage. A small-scale survey of the regulatory regions of 36 genes in 3 tissues showed that most of the 18 significant differences in promoter methylation were in the brain70. However, changes in methylation status could be due to dietary factors, including folate supplementation. A clearer understanding of the evolution of the molecular pathways involved in epigenetic regulation and chromatin structure, rather than just measurement of gene methylation, is necessary to interpret these data.

Genomic mechanisms

Genome structural changes

In addition to many single base-pair substitutions in the human genome, there is also a surprising abundance of larger structural changes, including insertions, deletions and duplications14,22,26. Chimpanzee–human structural changes are fewer in number but affect many more base pairs (~140 Mb) than do single base-pair substitutions (~35 Mb). These two forms of genetic variation are not readily comparable and should be considered separately. The gain and loss of genomic DNA segments has accelerated in humans and chimpanzees when compared with Old World monkeys (see FIG. 1a for an example) and other mammals23,25,28,71,72. Interestingly, this acceleration in genomic structural variation seems to coincide with a slow-down in single base-pair substitution in hominids73,74.

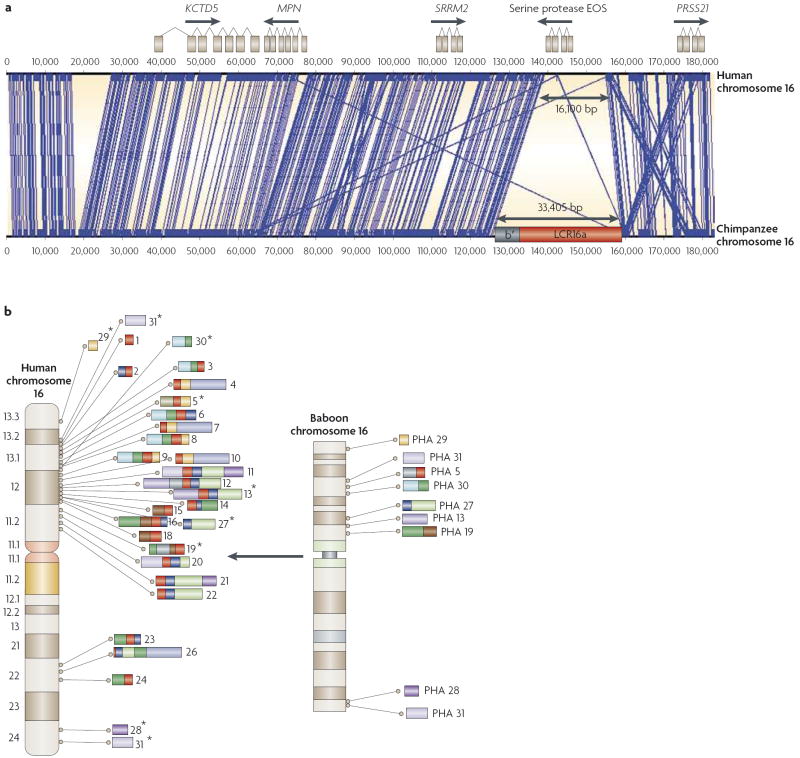

Figure 1. Structural variations and segmental duplications.

a Example of structural variation and segmental duplication difference between chimps and humans. An interspersed segmental duplication (33,405 bp) carries a copy of the rapidly evolving nuclear pore complex interacting protein gene (NPIP), a member of the morpheus gene family, into a new location on chromosome 16. The chimpanzee insertion results in a coordinated deletion (16,100 bp) of the serine protease EOS gene. As a result, chimpanzees carry an additional copy of the morpheus gene, carried within the duplicon LCR16a (low-copy repeat 16a), but have lost a serine protease gene that is present in humans. Blue lines identify regions of high sequence identity between chimpanzees and humans. b Human segmental duplication expansion on chromosome 16. Nine single-copy regions in Old World monkeys (as indicated on the baboon Papio hamadryas (PHA) chromosomal ideogram) became duplicated specifically within the human–great ape lineage of evolution. These loci were distributed to 31 different locations on human chromosome 16; 24 of these carry a human–great ape specific gene family known as morpheus (as indicated by the red-coloured duplicons)99. Rearrangements between these interspersed duplications are associated with mental retardation and autism in humans. Coloured blocks show the distribution of the duplicons between the two species, with the position of the ancestral loci indicated by asterisks. Figure is modified, with permission, from REF. 100 © (2006) National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Structural variation in the hominid genome shows several interesting features. First, this variation, especially in events >15 kb, is distributed non-randomly throughout the genome, with segmental duplications coinciding with hot spots of evolutionary change75,76. Seven of the nine pericentric inversions that distinguish human from chimpanzee chromosomes, for example, map to regions of segmental duplication77. Second, genes associated with immunity, chemosensory activity and reproduction are enriched within regions of primate structural variation14,22,28,78. Third, structural changes have strong effects on distal and local gene expression patterns, both within and between species58,79. Finally, there have been recent episodic or punctuated events during hominid genome evolution80-82. Below we consider various forms of structural variation, based on comparisons within and between primate species. We should caution that none of the NHP genomes has been sequenced as thoroughly as the human genome, and so conclusions must be tempered by the quality of underlying genomic sequence, especially over such dynamic regions.

Repeat elements and retroviruses

Approximately 50% of the human genome consists of various classes of repetitive DNA. A three-way comparison of chimpanzee, human and macaque genomes reveals few large-scale differences in repeat content since the divergence of humans and Old World monkeys over 25 million years (Myr) ago23. There are three notable exceptions. First, although NHH retrotransposition activity has generally decreased for both short and long interspersed nuclear elements (SINES and LINES), repeat activity of the Alu transposable element has been three times more active in humans than in chimpanzees. Thus, there are ~7,000 new Alu insertions within the human lineage compared with ~2,500 in the chimpanzee14. Second, the SVA element (a 2–3 kb repeat element composed of a SINE, a variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) and an Alu sequence) emerged specifically within the hominid ancestor ~20 Myr ago. Human, chimpanzee and gorilla genomes show the greatest number (~2,500) of these elements, with specific subfamilies emerging within each lineage83. Younger elements are enriched within GC-rich genomic regions and show considerable (~25%) polymorphism14,83. This bias, and the fact that ~200 elements map within 5,000 bp of annotated genes, has led to speculation that these elements have altered the transcriptional landscape of some human genes14. Finally, both gorilla and chimpanzee genomes have undergone recent, episodic expansions of endogenous retrovirus repeat families near or shortly after the time of speciation (5–8 Myr ago)80. Thus, hundreds of full-length copies of the Pan troglodytes endogenous retrovirus 1 (PTERV1) exist at non-orthologous locations in the genomes of the chimpanzee and gorilla, but not in the human genome80. This burst of retroviral germline integrations near the time of African hominid speciation might thus have contributed to creating lineage-specific phenotypic differences over a short period80. Humans might have been spared this retroviral invasion owing to selective mutations of the tripartite motif 5 (TRIM5) immune-response protein84. It is also interesting that humans do not carry endemic infectious retroviruses (BOX 3).

Box 3 Explaining the lack of endemic infectious retroviruses in humans.

Other than the recent introductions of HIV and human T leukaemia virus (HTLV) into humans from other animals, humans seem to be devoid of species-wide endemic infectious retroviruses. By contrast, like most other mammals studied, other hominids and non-human primates (NHPs) do have such viruses. Indeed, given the remarkable corroboration between the phylogenetic trees of primates and their lineage-specific simian foamy viruses (SFVs)176 our common ancestors with other hominids almost certainly had SFVs. The same is probably true of the lineage-specific simian infectious retroviruses (SIVs) found in most NHPs177. Assuming that the common ancestors of hominids carried multiple endemic infectious retroviruses, how did the human lineage eliminate them? Given that humans remain susceptible to re-infection with both SFVs178 and SIVs177 from other hominids, this seems unlikely to be explained solely on the basis of more efficient host restriction systems84. Rather, there seems to have been an episode in which the ancestral human lineage was somehow ‘purged’ of these endemic viruses. One testable hypothesis is that human-specific loss of the sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid, which would normally be acquired by such enveloped viruses, could restrict viral transmission because of the simultaneous appearance of antibodies against this sialic acid in hominins179,180

Gene deletions

Olson first suggested that deletions had a pivotal role in human evolution19,85. According to his ‘less-is-more’ hypothesis, the human was a “hastily made-over ape” in which irrevocable gene deletions were key factors in permitting human adaptations. Although a complete repertoire of such gene deletions does not exist, a total of 56 partially or predicted genes were confirmed as deleted in chimpanzees compared with humans and most were related to inflammatory response, parasite resistance or cell-surface antigens14. There is evidence for an almost twofold increase in gene loss in humans and chimpanzees when compared with macaques, and an almost fourfold increase in contrast to other mammals (for example, dogs, mice and rats)23,28,86. Interestingly, gene gain and gene loss might arise through the same mutational process (FIG. 1).

Most examples of human-specific gene losses have occurred within families of related genes with potentially redundant functions (for example, sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin 13, SIGLEC13)87, and/or are not universal to all humans (for example, caspase 12, CASP12)86. Thus, their significance for human uniqueness remains uncertain. There are few documented human-specific single-copy genes that have been lost from all living humans. The first example was the Alu-mediated inactivation of the cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase gene (CMAH)8, which probably occurred before the emergence of the Homo lineage88 and resulted in large changes in the cell-surface distribution of sialic acid types, and apparent secondary changes in the biology of various sialic acid-recognizing proteins89. Such deletions might have occurred in conjunction with changes in diet, pathogens or immune changes of human ancestral species.

Another example of human-specific gene loss is the sarcomeric myosin gene (myosin, heavy chain 16 pseudogene, MYH16), which underwent a 2 bp frameshift mutation90. This gene is expressed primarily within muscles of the hominid mandible, and its loss is hypothesized to have caused an eightfold reduction in the size of type II muscle fibres in humans, with an evolutionary timing claimed to coincide with a shift towards a gracile masticatory apparatus within Homo erectus and Homo ergaster. It was also hypothesized that associated changes in muscle insertions at the apex of the skull were permissive for encephalization. However, the timing and the biological significance of this gene loss have been contested91,92.

Gene and segmental duplications

The converse of the less-is-more hypothesis is that ‘more is better’, as argued by Ohno93. Comparisons of primate gene copy-number difference by array comparative genomic hybridization (ArrayCGH)25,27,94, and by experimental and computational analyses of segmental duplications22,23,72, in addition to comparisons of gene content between macaque, human and chimpanzee genomes28, support an overall increase in duplication activity in the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans compared with other mammals (FIG. 1b). It is unclear, however, whether humans have an excess of such duplications compared with chimpanzees. After correcting for copy-number differences, the overall amount of lineage-specific duplications between humans and chimpanzees seems to be similar22 — although human duplications are genetically more diverse when compared with chimpanzee duplications22. Data from other hominids should allow firmer conclusions to be drawn.

Hominid duplications are remarkable in two respects: they are more interspersed and show a higher degree of sequence identity, especially among intrachromosomal duplications, than those in other sequenced mammalian genomes71,95. This complex duplication architecture has led to the formation of hominid-specific gene families in humans and chimpanzees (for example, the morpheus gene family; FIG. 1) that lack clear orthologues in the mouse genome95-97. Although the specific function of these gene families is unknown, several of them show strong signatures of positive selection and dramatic changes in their expression pattern. For example, neuroblastoma breakpoint protein family (NBPF) genes are highly expressed in brain regions that are associated with higher cognition, and they show neuron-specific expression98. The segmental duplications associated with these genes served as the focal point for the evolution of the complex organization of interspersed duplications within the human genome81,99,100. Moreover, the expansion of hominid segmental duplications seems to be responsible in large part for the acceleration of gene duplication in humans and chimpanzees28,81 and there is evidence that these ‘core duplicons’ have duplicated independently in different hominid lineages100 (FIG. 1b).

Copy-number variants

Copy-number variants (CNV) are abundant in humans and preferentially associate with duplicated genes101-103. Larger events (>500 kb) that affect genes occur more rarely but are enriched in individuals with cognitive disabilities, such as mental retardation104, autism105,106 and schizophrenia107. More limited surveys in the chimpanzee108, macaque109 and mouse110,111 reveal that copy-number variation is a common source of genetic variation for such mammals, although it is premature to determine whether humans have more CNVs than these other species.

There are, however, important differences in CNV distributions. Whereas human CNVs are enriched in genes that show evidence of positive selection112, mouse CNVs are more gene-poor and show potentially less adaptive evolution. Similar differences in gene density between humans and mice occur for segmental duplications72 — which might be regarded as a more ancient form of copy-number variation. Although CNV gene density differs between mice and humans, CNVs in both species are enriched for genes that are important in environmental responses, for example, drug detoxification, olfaction and immune response. High-resolution surveys of human CNVs, however, reveal additional categories: transcription factors (especially zinc-finger genes) and genes that are important in the development of the central nervous system and in synaptic transmission113. Consistent with this finding is the association of larger de novo CNVs with two common neurodevelopmental disorders, autism and schizophrenia105-107, as described above. Also striking is human lineage-specific amplification of multiple copies of a protein domain of unknown function (DUF1220) and of the morpheus gene family on chromosome 16 (FIG. 1). These are hominid gene-family expansions that show signs of positive selection and neuron-specific expression98, and the underlying duplications mediate rearrangements associated with neurocognitive disease.

Owing to its effect on gene dosage, the selective effect of large CNVs might be greater when compared with most single-nucleotide substitution events112. In populations with large effective population sizes, such as the laboratory mouse (n = 500,000), selection would operate more efficiently, either fixing advantageous alleles or eliminating weakly deleterious alleles. By contrast, populations with smaller effective population sizes, such as humans (n = 10,000), are more prone to the whims of genetic drift than they are to selection. The small effective population size in hominid ancestral populations would thus allow a greater fraction of weakly deleterious alleles to reach appreciable allele frequencies. As some copy-number changes are themselves mutagenic (that is, duplicated sequences can predispose to new mutation events, such as inversions, deletions and duplications through non-allelic homologous recombination), there is a cascading effect of increasing potential structural variation. This dynamic nature would lead to increased diversity and, we suggest, a broader range of adaptive responses owing to greater standing diversity and to the potential for new mutation.

Gene-conversion events

Large-scale gene conversion probably accounts for <10% of highly identical segmental duplications22, whereas small-scale gene conversion events are thought to account for the increased sequence diversity observed within 10 Mb of primate telomeres14. Most gene conversions tend to disrupt gene function. However, a human-specific gene conversion that maintained an ORF occurred in the gene for Siglec-11; this is the first known ‘human-specific’ protein, and it is expressed in human but not NHH brains114. The significance of this human-specific event is unknown, and such small-scale gene conversion events have not been carefully searched for throughout the human genome.

Are large-scale genomic changes accumulating more rapidly in humans?

As mentioned above, interspersed segmental duplications and deletions are prominent in hominid genomes111. Available evidence suggests a trend in the number of duplication and deletions, with human = chimpanzee > macaque > rodent > chicken > Drosophila = Caenorhabditis elegans. It is possible that humans are accumulating these large-scale genomic variations at a faster rate than other hominids, but the data are too limited to ascertain this. It would be useful to obtain comparative data on widely disparate human population groups, for example, African San versus Native Americans, as well as from various ‘subspecies’ of chimpanzee.

Similar questions arise about CNVs. Again, data from multiple species are lacking. CNV diversity might be higher in humans, despite the small effective population size. There could also be fitness benefits associated with the propensity to generate and tolerate more CNVs, for example, the expansion of amylase gene copies in humans115. It is interesting that in this case copy numbers progressively drop as we move from agricultural humans to non-agricultural humans to chimpanzee and bonobo. It is also interesting that CNVs are now being recognized as significant causes of neuropsychiatric conditions, and so the question is whether they are more common in more subtle forms of human-specific diseases related to brain function and social interaction.

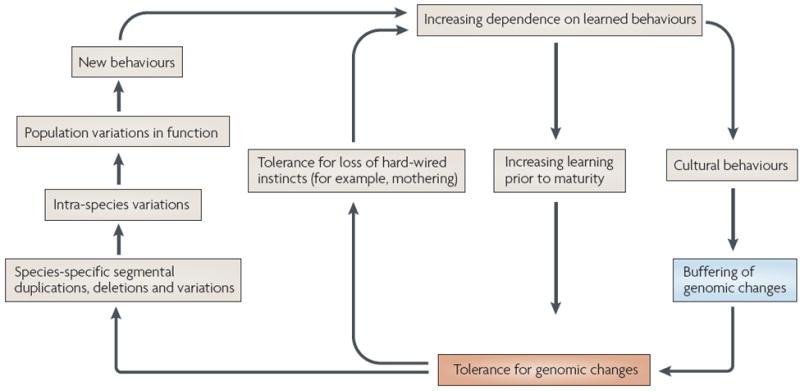

We propose below that the frequencies of large interspersed segmental deletions and duplications are greatest in hominids, followed by monkeys and then rodents, because they are better tolerated by hominids owing to buffering by the increasing dependence of important functions on learned rather than hard-wired behaviour. In this scenario, individuals bearing variant genomes might survive and even be beneficial to a human population, by contributing to genomic and phenotypic plasticity that is adaptive for the community at large, either in the short or long term.

Systems or network approaches

The inherent difficulty in determining whether a change in gene expression is adaptive or neutral argues strongly for the development of methods that place gene expression changes in a functional context. If gene expression changes were neutral they would not tend to accumulate in specific ontological or functional categories but, rather, would be randomly distributed. In this regard, it is notable that genes that are differentially expressed between human and chimpanzee brains are enriched for energy metabolism and protein-folding categories, consistent with their accelerated evolution62. One weakness of such an approach is that it does not assign any level of confidence to individual genes. Another is that genes can have multiple functions, and the Gene Ontology classifications do not take into account all biological processes (see below).

By contrast, network biology approaches allow individual genes to be placed within a functional context116,117 (BOX 4). Complex systems, biological or otherwise, exhibit properties of scale-free networks118. Furthermore, clusters of highly co-expressed genes, or modules, define groups of genes that are functionally related119-122. There is a small but significant correlation between being on the periphery of protein networks and the tendency to have undergone adaptive selection123, consistent with the functional relevance of network position. Oldham et al.120 reasoned that a comparative network approach would provide a general framework for identifying functional, or adaptive, changes in gene expression between chimpanzees and humans. Any changes in the network structure, for example, the network position of a specific gene, between two species provides a unifying manner in which to identify non-neutral (that is, functional) changes in gene expression relationship120 (BOX 4). This approach was used to concentrate on the specific genes or regions of the genome driving these adaptive changes. Overall, genes in modules corresponding to cerebral cortical modules, including those involving neuronal plasticity, showed the greatest divergence relative to sub-cortical brain regions, consistent with the primary role of the cerebral cortex in the evolution of human cognition and behaviour120. These studies provide a proof of principle, supporting the use of systems-biology approaches to inform cross-species comparisons, and facilitating the connection of phenotypes within specific organ systems to changes at the level of the genome.

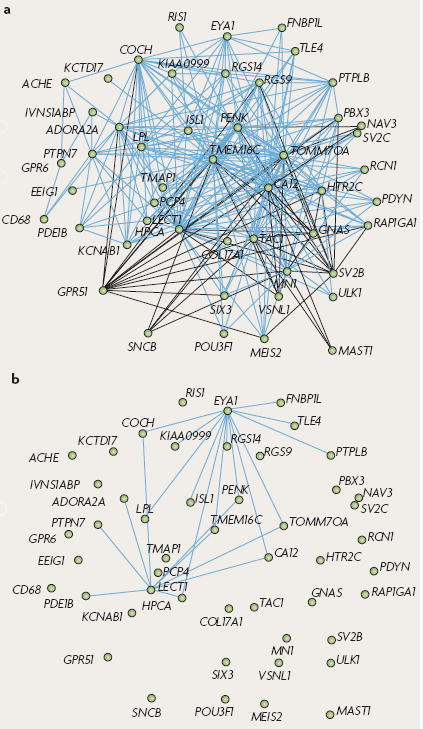

Box 4 Use of scale-free networks to study gene expression differences.

Complex systems, biological or otherwise, exhibit properties of scale-free networks118, which delineate an organization whereby a few nodes (that is, genes) are central, or ‘hubs’, serving as control points in the network, whereas most nodes are more peripheral and have few connections. This theoretical construct has been applied to gene expression data using a method called whole-genome network co-expression analysis (WGNCA)119-122 to provide a functional context to view transcriptome organization. Rather than simply studying differential expression, WCGNA uses the information from the measurement of co-expression relationships to create gene expression networks. The position of each gene in a given network is described by its connectivity (k), which summarizes its degree of connection to all other genes in the network. Genes with high k (hub genes) are crucial to the integrity and proper functioning of the network, and changes in their position between the networks of two species aids in discerning between adaptive versus neutral changes. The degree of network relationship between two genes is summarized by topological overlap (TO), a measure of network neighbourhood sharing118,119. Plotting genes on the basis of their degree of TO permits visualization of network structure; genes that cluster together define modules of functionally related genes. Comparison of networks between species, or between normal and diseased tissue, allows one to identify key functional changes that have occurred.

The figure demonstrates that differential connectivity in gene co-expression networks distinguishes adaptive evolutionary changes. Analysis of gene co-expression relationships using WCGNA in the human brain identifies modules that correspond to specific brain regions. Here, a module corresponding to the caudate nucleus is shown (a). Comparison of modules between humans and chimps can identify species-specific co-expression relationships (b). In part a of the figure, 300 pairs of genes with the greatest topological overlap in humans are depicted in a module that represents the caudate nucleus. Genes with expression levels that are negatively correlated (using Pearson correlation) are connected by black lines. Connections from part a that are present in humans but absent in chimpanzees are depicted in part b. Note that overall the module is highly conserved between the species, and most connections are not human specific. However, nearly all connections that are human specific converge upon two genes, eyes absent homologue 1 (EYA1) and leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 1 (LECT1), demonstrating a large change in network position; this is consistent with non-neutral evolution of these two genes, which are differentially expressed between chimpanzees and humans.

Figure is modified, with permission, from REF. 120 © (2006) National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Despite their great potential, there are limitations in using genome-wide approaches to exploring human uniqueness. First, it can be complicated to translate the results into a specific biological process or organ system. Second, as mentioned earlier, Gene Ontology and Panther-type gene classification systems do not take into account all possible biological processes. For instance, the genes involved in one biological process (sialic-acid biosynthesis, addition and recognition) are randomly scattered throughout the Gene Ontology and Panther categories39. Thus, genome-wide approaches need to be complemented by candidate gene approaches, as described in the following section.

An organ-systems view

Ultimately, it is necessary to connect specific genes and genomic processes to the phenotypes that are most relevant for human evolution. In particular, analyses could focus on genes and other genomic elements involved in those physiological and organ systems that show the most differences between humans and other hominids. Below, we consider relevant issues for some organ systems that feature aspects of human uniqueness.

Brain and nervous system

In considering human uniqueness, encephalization is typically the first aspect to be given attention, partly because it is the easiest to measure, even in fossil hominids. However, modern human brain size was reached >100,000 years before archaeological evidence of modern human behaviours is seen124. Taken together with other evidence, such as poor correlation between brain size and cognitive abilities125 and the remarkable abilities of individuals surviving extensive brain injury or surgery in infancy126, it is reasonable to say that encephalization has been overrated as being the key to human cognitive abilities. It was probably an important and necessary step along the way, but insufficient to achieve modern human cognition. Even the notion that human brain frontal lobes are selectively enlarged has been questioned by modern studies127.

Conversely, some uniquely human cognitive phenotypes are well delineated and can be connected to regions of the cerebral cortex, including language (peri-sylvian cortex and hemispheric asymmetry)128-130, artistic, musical and mathematic abilities (multiple regions), and planning (frontal systems). Others, such as primary sensory regions, have received little attention, but when rigorously assessed show significant morphological and molecular differences between humans and chimpanzees61,131. Thus, phenotype discovery and genotype correlation must be an important component of studies of human brain evolution128,130,132,133.

Social awareness is a potentially central area of cognition in which humans might excel relative to their closest primate relatives134,135, and the cortical regions involved in these functions are implicated in disorders of human social behaviour, such as autism136-138. Parallel distributed circuits that are involved in language and that use specific regions that are more developed in humans than in non-human primates have also been identified130,139. Understanding how evolution of our genome maps onto changes in the size and connectivity of these specific cortical association areas — key regions that underlie the remarkable development and flexibility inherent in human cognition and behaviour — is of central importance128. One exciting example might be the spindle cell (Von Economo) neurons, which are enriched in the human cingulate and insular cortex relative to NHHs, and are not found in non-hominid primates137,140. This cell type is also selectively vulnerable in frontotemporal dementia141. This highlights the potential of human diseases to help delineate the underlying functional relevance of specific brain phenotypes or genes.

Thus, in the context of clear adaptive evolution of certain brain phenotypes in humans, the underlying specific genetic changes should be identifiable. Several nervous-system genes undergoing adaptive evolution at the protein level have been identified in humans, including genes involved in neurogenesis, hearing and developmental patterning30. Apparent adaptive evolution of forkhead box P2 (FOXP2), a gene involved in human speech production, has been reported in the human lineage142,143, with the derived variant being shared with Neanderthals144. Remarkably, recent studies show that FOXP2 is also related to vocal learning in birds, in a circuit with functional homology to humans145-148, and is rapidly evolving in bats, which one can speculate might be related to their echolocation capacity149. This suggests that the phenotype involved is not language per se, but rather the development and function of circuits involved in sensory-motor integration that contribute to vocal motor learning in multiple species150. New evidence for adaptive selection on a subset of FOXP2 transcriptional targets in humans raises the possibility of potential co-evolution of a transcriptional programme downstream of FOXP2 (REF. 151). Thus, one can speculate that it might be the adaptive evolution of such a pathway, rather than of FOXP2 alone, that is connected to language and speech function in humans.

However, connecting such genes involved in disorders of human cognition to the specific phenotypes undergoing selection poses significant challenges. A salient example involves two genes, abnormal spindle homologue microcephaly associated (ASPM) and microcephalin (MCPH1), the adaptive evolution of these genes in humans was claimed to be related to normal variation in brain size, on the basis of the fact that Mendelian mutations in each results in microcephaly in humans152,153. However, not all investigators have found evidence for the adaptive evolution of ASPM or MCPH1 (REF. 154). Also, neither gene is likely to contribute significantly to normal variation in human brain size155. This case illustrates the challenges of interpreting genetic data in the face of complex phenotypes, especially those that are poorly understood.

Sensory systems

With the possible exception of our tricolour stereoscopic vision and finger-tip tactile sensation, most human sensory systems have, if anything, lost acuity during our evolution. An interesting case documented at the genomic level seems to be the sense of smell, with which humans seem to have lost, by pseudogenization, many of the hundreds of olfactory-receptor genes that are found in rodents and in other primates156. Interestingly, the situation was found to be intermediate for the chimpanzee156 — although others have recently claimed that this is not the case157. As discussed later, buffering by cultural factors might have allowed such gene loss without negatively affecting the survival of the species. In this regard, it is of note that human olfactory perception differs widely between individuals, and that this might be related to genetic variation in human odorant-receptor genes157-159. Another interesting difference relates to the bitter-taste receptor genes in hominids, with humans having a higher proportion of pseudogenes than apes160-162.

Skin and appendages

Of all the organ systems, it is the skin and its appendages (such as sweat glands, hair and breasts) that show the most striking differences between humans and other hominids. Furthermore, this organ system is most accessible to safe and ethical sampling. Despite this, we are unaware of any systematic comparisons of the biology of the skin between humans and other hominids. One frequently noted difference is the poor wound-healing abilities of humans, a phenotype that is partially recapitulated in a mouse line that has a human-like genetic defect in the Cmah gene163.

Musculoskeletal system

Humans are generally more gracile than other hominids, with weaker muscles and less prominent muscle insertion points on our bones124. Apart from the MYH16 mutation mentioned above, little has been done to study the molecular basis of these differences. Other striking differences include our upright state after infanthood and our capacity for striding, bipedal walking and running164. Of course, it is not even clear if bipedalism is fully programmed genetically or if it is at least partially acquired by observation, learning and teaching. In this regard, the high frequency of human problems associated with bipedalism (for example, back and spine disorders) bears testament to the incomplete human adaptation to this locomotor state.

Reproductive system

There are also several apparent differences between humans and NHHs in reproductive biology and disease, particularly in females. Examples include difficult childbirth, the full development of breasts before pregnancy, the process of menopause, and the high degree of blood loss during menstruation, often leading to chronic iron deficiency. Again, there are as yet few molecular correlates of these differences. One clue is the human-specific expression of SIGLEC6 in the placental trophoblast, which seems to increase in expression during labour165.

Immune system

The striking difference in the reaction of the human and chimpanzee immune systems to the HIV or chimpanzee immunodeficiency virus, respectively, with the latter being resistant to progression to AIDS, as well as the apparent rarity of other T-cell-mediated disorders in chimpanzees19,20 indicates some fundamental differences in the responsiveness of the immune system. One candidate for explaining this difference is suppression of expression of inhibitory SIGLEC genes in human T cells166.

Practical implications

Overall, the organ-systems approach has much to offer, as it can complement genome-wide studies by focusing the efforts on specific phenotypes or features that seem to be uniquely human. Ultimately, the practical implications of understanding the genetic and genomic basis of uniquely human features range from understanding human cognition, with its frequent variations and abnormalities, to explaining diseases to which humans are particularly susceptible.

Uniquely human evolutionary processes?

Effects of behaviour and culture on the phenotype

Current understanding of genetic and phenotypic features of human evolution indicates that traditional evolutionary biology approaches have yet to explain most of the unique features of humans. We can therefore enter into more speculative discussions concerning how genome–environment interactions are modified by behaviour in warm-blooded animals in general and in primates in particular, and how these interactions are further modified by learning, teaching and culture in humans. Although we realize that much of what we suggest below is necessarily speculative there is general support from currently available knowledge, and we hope that this can form the basis for a rigorous and productive debate and research programme.

The phenotype of a fly or worm can be affected by its external and internal environment, but behavioural responses tend to be relatively hard-wired and stereotyped. With warm-blooded animals one sees a greater impact of postnatal care and of influence of learning from the prior generation — with humans being at one extreme end of this trend. Indeed, there is little doubt that, at least in mammals, behaviour can have profound effects on the genome and the phenotype by affecting the functional output of the genome either directly or indirectly. One example can be found in the two distinct developmental pathways of male orangutans, in which juveniles exposed to an aggressive mature conspecific male undergo permanent arrest of secondary sexual development167, allowing an alternative reproductive strategy.

In the case of hominids in general, and humans in particular, the further confounding issue is the effect of culture. For example, specific behaviours and their accompanying artefacts that are not hard-wired but are instead handed down from generation to generation by observation and, in the case of humans, by teaching, learning, conscious choice, and even by imposition through cultural practices or institutions. Thus, for example, genetically identical twins who happen to choose different careers (for instance, one an ascetic Buddhist monk the other a sumo wrestler) could end up with such markedly different physical, behavioural and cognitive phenotypes that an alien anthropologist might initially think they were different sub-species of humans.

In this regard, it is notable that even stereotyped mammalian behaviours that are considered crucial for species survival, such as effective mothering, seem to require observational learning in primates168-170. For example, one of the fears arising from the current National Institutes of Health ban on chimpanzee breeding171 is the narrow time window before there will be no more fertile chimp females who have observed maternal care by an older female, something that is required for successful rearing of an new chimpanzee infant169,170. The situation is quite different in a dog or mouse mother who has not previously observed maternal behaviour, and is yet able to carry out these vital functions instinctively. Another example is the great difficulty in reintroducing primates in general and apes in particular back into the wild172, which is at least partly due to the fact that they lack so many of the hard-wired behaviours required for survival173. Thus, we must consider the possibility that hominids in general and humans in particular have partially escaped from classic Darwinian selective control of some aspects of the genome (BOX 5; FIG. 2), and that humans have even escaped the final stage of Baldwinian genetic hard-wiring of long-standing species-specific learned behaviours (BOX 5). This might in turn help to explain the unusual degree of exaptation displayed by the human brain, presented as ‘Wallace’s Conundrum’ in BOX 6. The advantages of such novel changes are flexibility, plasticity, more rapidly developing population diversity and greater opportunities — but the disadvantages are that genomes cannot recover what has been irrevocably lost, and cultural advantages can be sensitive to the whims of history and fate.

Box 5 Have humans escaped Baldwinian hard-wiring of behaviours?

The Baldwin effect considers the costs and benefits of learning, in the context of evolution. Baldwin and others proposed that learning by individuals could potentially explain evolutionary phenomena that superficially seem to involve Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics181-183. Given sufficient organismal plasticity, abilities that initially require learning could be replaced by rapid evolution of genetically determined systems that no longer require that learning. Behaviours that were initially learned would thus become instinctive ones in later generations, either because of new mutations or by ‘genetic assimilation’ of pre-existing genomic variability182. If a learned behaviour fails to become hard-wired genetically, it should then be susceptible to rapid disappearance, as there is a significant cost to the individuals who have to display the phenotypic plasticity to be able to learn.

There remains some controversy about the exact definition of the Baldwin effect and its importance to evolution in general184. However, some authors have suggested a role for Baldwinian processes in the evolution of uniquely human features, such as human language abilities185,186. For example, Deacon’s proposal187 is that complexes of genes can be integrated into functional groups as a result of environmental changes that mask and unmask selection pressures, that is, a reverse Baldwin effect facilitated by niche construction188. In this regard, it is interesting that learned behaviours can be carried for many human generations without becoming hard-wired. For example, some long-isolated and small populations, such as Tasmanian Aboriginals, partially or completely lost many ancestral material practices, such as the making of fire and exploitation of certain marine food resources189. Apparently, such long-standing learned behaviours never become genetically hard-wired in humans and they remain dependent on intergenerational transfer by observation, learning and/or teaching. Perhaps humans have escaped the need for the last phase of the Baldwin effect that genetically hard-wires behaviours, and instead utilize extended developmental plasticity to invent, disseminate, improve and culturally transmit complex behaviours over many generations, without the need to hard-wire them. Of course, this advantage comes with great risk, as failure of cultural transmission can then result in permanent loss of a useful behaviour.

Figure 2. Are human genomes escaping from Darwinian natural selection and Baldwinian fixation of learned behaviours?

The figure shows potential mechanisms of behavioural and cultural buffering of genomic changes, potentially allowing hominid genomes to partially escape Darwinian selection and avoiding the need for the final phase of the Baldwin effect, in which learned behaviours eventually become hard-wired in the genome. The potential feedback loops shown could accelerate such processes, and even make some of them irreversible. See the main text and BOXES 5,6 for further discussion.

Box 6 Wallace’s Conundrum.

The 2009 Darwin Centenary celebrations will further downplay Alfred Russel Wallace’s co-discovery of the theory of evolution by natural selection190. Wallace lost favour with the scientific community partly because he questioned whether natural selection alone could account for the evolution of human mind, writing: “I do not consider that all nature can be explained on the principles of which I am so ardent an advocate; and that I am now myself going to state objections, and to place limits, to the power of ‘natural selection’. How could ‘natural selection’, or survival of the fittest in the struggle for existence, at all favour the development of mental powers so entirely removed from the material necessities of savage men, and which even now, with our comparatively high civilization, are, in their farthest developments, in advance of the age, and appear to have relation rather to the future of the race than to its actual status?”191.

Although Wallace was criticized for apparently invoking spiritual explanations192, one of his key points remains valid — that it is difficult to explain how conventional natural selection could have selected ahead of time for the remarkable capabilities of the human mind, which we are still continuing to explore today. An example is writing, which was invented long after the human mind evolved and continues to be modified and utilized in myriad ways. Explanations based on exaptation193 seem inadequate, as most of what the human mind routinely does today did not even exist at the time it was originally evolving. Experts in human evolution or cognition have yet to provide a truly satisfactory explanation. Thus, ‘Wallace’s Conundrum’ remains unresolved: “[…] that the same law which appears to have sufficed for the development of animals, has been alone the cause of man’s superior mental nature, […] will, I have no doubt, be overruled and explained away. But I venture to think they will nevertheless maintain their ground, and that they can only be met by the discovery of new facts or new laws, of a nature very different from any yet known to us.”191.

Perhaps this proposed novel ‘Wallacean’ evolutionary mechanism relates partly to our suggestion that aspects of human uniqueness arose when there was relaxation of selection for maintenance of genome integrity, thus allowing us to partially escape from conventional Darwinian and Baldwinian selection processes, and to become much more dependent on inter-generational cultural transfer.

Conclusions and perspectives

With the exception of the FOXP2 gene, in which mutations cause a defined phenotype in humans, and some human-specific consequences of the CMAH gene mutation, much of the discussion about genes involved in human uniqueness has been somewhat speculative. Indeed, it is difficult to predict which answers might be accessible to us in the next years, and which approaches will be most fruitful. How then should we best proceed towards explaining human uniqueness? More rigorous attempts to connect changes at the genome level to specific phenotypes are necessary174. Phenotypes as complex as human cognition and intelligence are unlikely to be explained by any of the current studies, many of which have relied on small sample numbers, limited methods and many unproven assumptions. Such attempts will only yield true success if experts from multiple disciplines coalesce into transdisciplinary teams that probe multiple hypotheses concurrently, while avoiding preconceived notions based on the understanding of the evolution of other species. From this perspective, there is also a need to study many more closely related species that can provide more solid outgroup information, and to address the need for larger sample sizes among each primate group. All of these approaches will be better informed by a broader understanding of what areas of the genome are functional, and improved methods for analysing differences between genomes will probably be fuelled by the emerging field of systems biology. In this manner, approaches beginning with genotype and those starting with phenotype will meet and provide a level of convergent evidence that has so far not been mustered in this arena. Perhaps this will direct us on a rational path towards understanding human uniqueness, taking into account the interlinked roles of changes in Darwinian, Baldwinian, Wallacean and other as yet unknown mechanisms that gave rise to the unusual features of our species.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge comments from P. Gagneux, R. Bingham, D. Nelson, P. Churchland, F. Ayala, S. Hrdy, and two anonymous reviewers; M. Oldham for adapting the figure in BOX 4; and funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), the Mathers Foundation and the Gordon and Virginia MacDonald Foundation (to D.H.G.). The authors have National Institutes of Health grant funding: GM32373 to A.V., H60233 to D.H.G. and GM58815 to E.E.E.

- Hominid

The term that is now often used to refer to the clade that includes both humans and great apes (that is, chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans). The term hominoid is also no longer routinely used for great apes. In recognition of these changes, we have introduced the term non-human hominids in place of great apes in most places. However, we recognize that the nomenclature is still in flux.

- Positive selection

A form of natural selection that increases the frequency of beneficial alleles in a population.

- Outgroup

A related but taxonomically distinct species that can be used to infer the ancestral state of a particular characteristic.

- Tissue heterogeneity

The presence of a large and variable number of cell types within a given tissue. Tissue heterogeneity in the brain might blunt the ability to detect the most variable low abundant genes in the brain relative to less complex tissue.

- Neutral theory

The word ‘neutral’ has two different meanings in population genetics literature. The strictly neutral model assumes that all mutations are neutral, whereas the biologically neutral model assumes that all mutations are either neutral or deleterious.

- Encephalization

An increase in brain size relative to body size.

- Array comparative genomic hybridization

(ArrayCGH). A technique used to measure the relative copy number of a test and reference DNA sample based on differential hybridization to DNA molecules fixed on a microarray.

- Copy-number variant

(CNV). A gain or loss of a >1 kb DNA region that contains genes. Most copy-number polymorphisms tend to be small (<10 kb) in size. De novo CNVs are variants that largely arise by new mutation, as opposed to hereditary transmission.

- Gene conversion

A non-reciprocal recombination process that results in an alteration of the sequence of a gene to that of its homologue during meiosis.

- Ontology

A hierarchical organization of concepts. The Gene Ontology framework provides one means for determining whether gene expression differences represent enrichment for specific functional categories.

- Scale-free network

A network in which a few nodes (for example, genes) are central (that is, they act as ‘hubs’) and therefore serve as control points in the network, whereas most nodes are more peripheral and have few connections.

- Parallel distributed circuits

Interconnected brain regions that work coordinately, to yield cognition and behaviour.

- Frontotemporal dementia

A degenerative disease that frequently involves dilapidation of social cognition.

- Pseudogenization

Changes within the coding region of a gene that prevent transcription of a functional protein product.

- Exaptation

When a useful feature arises during evolution for a different reason, but is subsequently co-opted for its current function.

Footnotes

FURTHER INFORMATION

The Varki laboratory: http://cmm.ucsd.edu/Lab_Pages/varki/varkilab/index4.htm

The Geschwind laboratory: http://geschwindlab.neurology.ucla.edu

The Eichler laboratory: http://eichlerlab.gs.washington.edu

miRBase, Sanger Institute: http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences

References

- 1.Huxley TH. Evidence as to Man’s place in Nature. Williams and Norgate; London: 1863. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darwfin C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. D. Appleton; New York: 1871. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarich VM, Wilson AC. Immunological time scale for hominid evolution. Science. 1967;158:1200–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3805.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syner FN, Goodman M. Differences in the lactic dehydrogenases of primate brains. Nature. 1966;209:426–428. doi: 10.1038/209426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Waal FB. A century of getting to know the chimpanzee. Nature. 2005;437:56–59. doi: 10.1038/nature03999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King MC, Wilson AC. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science. 1975;188:107–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1090005. Synthesizes diverse data sets to show that the level of molecular change that exists between chimpanzees and humans is dissonant with the numerous morphological differences seen between species. It concludes that regulatory differences in gene expression probably underlie species differences.

- 7.Maresco DL, et al. Localization of FCGR1 encoding Fcγ receptor class I in primates: molecular evidence for two pericentric inversions during the evolution of human chromosome 1. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;82:71–74. doi: 10.1159/000015067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou HH, et al. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo–Pan divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751. This is the first paper to report that a genetic difference between humans and other hominids results in a definite biochemical change — in human cell-surface sialic acids. Subsequently, more than 10 uniquely human changes in sialic-acid biology have been discovered, as described in reference 89.

- 9.Szabo Z, et al. Sequential loss of two neighboring exons of the tropoelastin gene during primate evolution. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:664–671. doi: 10.1007/pl00006587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConkey EH, Goodman M. A Human Genome Evolution Project is needed. Trends Genet. 1997;13:350–351. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigilant L, Pääbo S. A chimpanzee millennium. Biol Chem. 1999;380:1353–1354. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McConkey EH, Varki A. A primate genome project deserves high priority. Science. 2000;289:1295–1296. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1295b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varki A. A chimpanzee genome project is a biomedical imperative. Genome Res. 2000;10:1065–1070. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. Presents a detailed comparison of human and chimpanzee genomes, including confirmation (see also reference 21) that structural and copy-number changes affect four times the number of base pairs than single-nucleotide differences.

- 15.Noonan JP, et al. Sequencing and analysis of Neanderthal genomic DNA. Science. 2006;314:1113–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1131412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green RE, et al. Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA. Nature. 2006;444:330–336. doi: 10.1038/nature05336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varki A, et al. Great Ape Phenome Project? Science. 1998;282:239–240. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.239d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridley M. Nature via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes us Human. HarperCollins; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson MV, Varki A. Sequencing the chimpanzee genome: insights into human evolution and disease. Nature Rev Genet. 2003;4:20–28. doi: 10.1038/nrg981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varki A, Altheide TK. Comparing the human and chimpanzee genomes: searching for needles in a haystack. Genome Res. 2005;15:1746–1758. doi: 10.1101/gr.3737405. Includes a list of several phenotypic features that show apparent or real differences between humans and great apes.

- 21.Britten RJ. Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13633–13635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172510699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng Z, et al. A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications. Nature. 2005;437:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature04000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbs RA, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prabhakar S, Noonan JP, Pääbo S, Rubin EM. Accelerated evolution of conserved noncoding sequences in humans. Science. 2006;314:786. doi: 10.1126/science.1130738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fortna A, et al. Lineage-specific gene duplication and loss in human and great ape evolution. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman TL, et al. A genome-wide survey of structural variation between human and chimpanzee. Genome Res. 2005;15:1344–1356. doi: 10.1101/gr.4338005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumas L, et al. Gene copy number variation spanning 60 million years of human and primate evolution. Genome Res. 2007;17:1266–1277. doi: 10.1101/gr.6557307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn MW, Demuth JP, Han SG. Accelerated rate of gene gain and loss in primates. Genetics. 2007;177:1941–1949. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khaitovich P, et al. Parallel patterns of evolution in the genomes and transcriptomes of humans and chimpanzees. Science. 2005;309:1850–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.1108296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark AG, et al. Inferring nonneutral evolution from human–chimp–mouse orthologous gene trios. Science. 2003;302:1960–1963. doi: 10.1126/science.1088821. In this key paper, the mouse is used as an outgroup to identify genes undergoing positive selection in humans.

- 31.Dorus S, et al. Accelerated evolution of nervous system genes in the origin of Homo sapiens. Cell. 2004;119:1027–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi P, Bakewell MA, Zhang J. Did brain-specific genes evolve faster in humans than in chimpanzees? Trends Genet. 2006;22:608–613. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen R, et al. A scan for positively selected genes in the genomes of humans and chimpanzees. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakewell MA, Shi P, Zhang J. More genes underwent positive selection in chimpanzee evolution than in human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7489–7494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701705104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyko AR, et al. Assessing the evolutionary impact of amino acid mutations in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu XJ, Zheng HK, Wang J, Wang W, Su B. Detecting lineage-specific adaptive evolution of brain-expressed genes in human using rhesus macaque as outgroup. Genomics. 2006;88:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang HY, et al. Rate of evolution in brain-expressed genes in humans and other primates. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bustamante CD, et al. Natural selection on protein-coding genes in the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1153–1157. doi: 10.1038/nature04240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altheide TK, et al. System-wide genomic and biochemical comparisons of sialic acid biology among primates and rodents: evidence for two modes of rapid evolution. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25689–25702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan Q, et al. Revealing global regulatory features of mammalian alternative splicing using a quantitative microarray platform. Mol Cell. 2004;16:929–941. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang XH, Chasin LA. Comparison of multiple vertebrate genomes reveals the birth and evolution of human exons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13427–13432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603042103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calarco JA, et al. Global analysis of alternative splicing differences between humans and chimpanzees. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2963–2975. doi: 10.1101/gad.1606907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu ZX, Peng J, Su B. A human-specific mutation leads to the origin of a novel splice form of neuropsin (KLK8), a gene involved in learning and memory. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:978–984. doi: 10.1002/humu.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keightley PD, Lercher MJ, Eyre-Walker A. Evidence for widespread degradation of gene control regions in hominid genomes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030042. A surprising finding of poor evolutionary conservation in the regulatory regions of human and chimpanzee genes. The authors suggest that there is “a widespread degradation of the genome during the evolution of humans and chimpanzees”, a proposal that fits with our speculations here about relaxation of constraints on genomic diversity owing to buffering by culture and learning.

- 46.Berezikov E, et al. Diversity of microRNAs in human and chimpanzee brain. Nature Genet. 2006;38:1375–1377. doi: 10.1038/ng1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollard KS, et al. An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature. 2006;443:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature05113. A ranking of regions in the human genome manifesting significant evolutionary acceleration shows that most of these human accelerated regions (HARs) do not code for proteins. The most dramatic change is seen in HAR1, which is part of a novel RNA gene (HAR1F) that is expressed specifically in the developing human neocortex.

- 48.Landgraf P, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerstein MB, et al. What is a gene, post-ENCODE? History and updated definition. Genome Res. 2007;17:669–681. doi: 10.1101/gr.6339607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asthana S, et al. Widely distributed noncoding purifying selection in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12410–12415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Margulies EH, et al. Analyses of deep mammalian sequence alignments and constraint predictions for 1% of the human genome. Genome Res. 2007;17:760–774. doi: 10.1101/gr.6034307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pheasant M, Mattick JS. Raising the estimate of functional human sequences. Genome Res. 2007;17:1245–1253. doi: 10.1101/gr.6406307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng J, et al. Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution. Science. 2005;308:1149–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1108625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu JQ, et al. Systematic analysis of transcribed loci in ENCODE regions using RACE sequencing reveals extensive transcription in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]