Abstract

With the increasing interest in protein adsorption in fields ranging from bionanotechnology to biomedical engineering, there is a growing need to understand protein-surface interactions at a fundamental level, such as the interaction between individual amino acid residues of a protein and functional groups presented by a surface. However, relatively little data are available that experimentally provide a quantitative, comparative measure of these types of interactions. To address this deficiency, the objective of this study was to generate a database of experimentally measured standard state adsorption free energy (ΔGoads) values for a wide variety of amino acid residue-surface interactions using a host-guest peptide and alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) with polymer-like functionality as the model system. The host-guest amino acid sequence was synthesized in the form of TGTG-X-GTGT where G & T are glycine and threonine amino acid residues and X represents a variable residue. In this paper, we report ΔGoads values for the adsorption of twelve different types of the host-guest peptides on a set of nine different SAM surfaces, for a total of 108 peptide-surface systems. The ΔGoads values for these 108 peptide-surface combinations show clear trends in adsorption behavior that are dependent on both peptide composition and surface chemistry. These data provide a benchmark experimental data set from which fundamental interactions that govern peptide and protein adsorption behavior can be better understood and compared.

I. INTRODUCTION

Peptides have long been recognized as an important class of molecules in biochemistry, medicinal chemistry, and physiology1–4 and are becoming increasingly important in biomedical research5–8 and bionanotechnology,9 especially for areas related to peptide adsorption behavior at liquid-solid interfaces. For example, Sarikaya et al. and Serizwa et al. have performed a series of experiments to study the adsorption behavior of genetically engineered peptides (GEP) from phage display on various material substrates.10–14 From these studies, they showed that different sequences of the 20 primary amino acids exhibit a unique fingerprint of interaction with different material surfaces. The results of these studies are being used for the design of core-shell quantum dots as well as for other biomimetic applications in bionanotechnology. Peptide adsorption is also important in the study of peptides-lipid membrane interactions.15–17 White et al. have used pentapeptides models to study the partition free energy of unfolded polypeptides at cell membrane interfaces,18 from which they developed an experimentally based algorithm to predict the binding free energy and secondary structure of peptides and proteins that partition into the lipid bilayer interface.19–21 These studies are being used to provide insight into the processes that influence cellular function.

An understanding of how peptides interact with surfaces is also very important for understanding protein adsorption behavior because, at a fundamental level, protein adsorption processes can be considered to be represented by the combination of the individual interactions between the amino acid residues making up a protein, the solvent environment, and the functional groups presented by a surface. Therefore, a quantitative understanding of the relative strength of adsorption for individual amino acid residues as a function of surface chemistry should provide insights into the adsorption behavior of whole proteins. Although it can be expected to be difficult to directly predict protein adsorption behavior based on peptide-surface interactions alone,22 protein adsorption behavior can be predicted through the use of empirical force field-based molecular simulation methods.7, 23–27 However, the ability of empirical force field methods to accurately predict protein adsorption behavior first requires that force field parameters be validated to accurately represent atomistic-level interactions between amino acid residues and functionalized surfaces;28 this in turn requires that a suitable benchmark experimental data set be available from which molecular simulation results can be compared and assessed.28, 29

The objective of this study was therefore to generate a database of experimentally measured standard state adsorption free energy (ΔGoads) values for a wide variety of peptide-surface combinations using a relatively simple adsorption system so that adsorption behavior between different amino acid residues and surface functional groups can be quantitatively evaluated. The Gibbs free energy function was selected as the most appropriate parameter to be determined for these studies because it provides a direct assessment of the primary thermodynamic driving force that characterizes the overall tendency of a peptide to adsorb to a surface.30–32 Also, because the change in Gibbs free energy for peptide-surface interactions can be calculated by molecular simulation using a selected empirical force field,33 comparisons between the calculated and experimentally determined values of ΔGoads can be used to assess the validity of a force field to represent the molecular behavior of this type of system.

To achieve this objective we designed a host-guest peptide model in the form of TGTG-X-GTGT, where G and T are glycine and threonine, respectively, and X is a variable (guest) residue. Functionalized alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold were selected to provide the adsorbent surfaces.34, 35 ΔGoads values were determined from adsorption isotherms generated by surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy (SPR) for each peptide-surface combination using methods that we previously published,36 which were designed to enable bulk-shift effects to be directly determined from each adsorption isotherm and to minimize the effects of solute-solute interactions 6at the surface for the accurate determination of ΔGoads.

In this present paper, we report on the application of these methods to characterize the adsorption behavior of 12 different peptides on nine different SAM surfaces, thus providing a set of 108 different peptide-surface combinations. These results provide a quantitative measure of peptide adsorption behavior at a liquid-solid interface as a function of amino acid type and surface functionality, thus providing insights for understanding peptide and protein adsorption behavior for applications in bionanotechnology and biomedical engineering. Moreover, these results provide an experimental benchmark data set that can be used to support the evaluation, modification, and validation of force field parameters for the simulation of peptide and protein adsorption behavior.7, 23

II. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

II.a. Alkanethiol SAM Surfaces

All alkanethiols used in these experiments for the formation of the SAM monolayers on gold had a structure of HS-(CH2)11-R with the following R terminal groups: -OH, -CH3, -NH2, -COOH, -COOCH3, -NHCOCH3, -OC6H5, -OCH2CF3 or -(O-CH2-CH2)3OH (i.e., -EG3-OH) (alkanethiols purchased from Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA; Prochimia, Sopot, Poland; or Asemblon, Redmond, WA, USA). These alkanethiols were selected to create surfaces that present functional groups similar to a broad range of organic polymers; for example: hydrogels and chitin (OH), polyethylene and polypropylene (-CH3), methyl acrylates and polyesters (-COOCH3), Nylons and chitin (-NHCOCH3), and polystyrene and polyaromatics (-C6H5), as well as polymers with acidic (-COOH), basic (-NH2), and ethylene glycol (-EGn-OH) functional groups.

The bare gold surfaces for the SPR experiments were purchased from Biacore (SIA Au kit, BR-1004-05, Biacore, Inc., Uppsala, Sweden). Prior to use, all of the surfaces were sonicated (Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, CT) at 50 °C for 1 min in each of the following solutions in order: “piranha” wash (7:3 (v/v) H2SO4 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) / H2O2 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), and a basic solution (1:1:3 (v/v/v) NH4OH (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) / H2O2 / H2O). After each cleaning solution, the slides were rinsed with nano-pure water and dried under a steady stream of nitrogen gas (National Welders Supply Co., Charlotte, NC, USA). The cleaned slides were rinsed with ethanol and incubated into the appropriate 1mM alkanethiol solution in 100% (absolute) ethanol (PHARMCO-AAPER, Shelbyville, KY, USA) for a minimum of 16 hours. The formation of monolayers from the amine-terminated alkanethiols required additional procedures to be applied to avoid either upside-down monolayer and/or multilayer formation. These monolayers were assembled from basic solution to assure that the amine terminus remained deprotonated (i.e., uncharged), which helps prevent the formation of an upside-down monolayer and subsequent multilayer formation.37 Accordingly, the 100% (absolute) ethanol used to prepare the amine terminated thiols was adjusted to pH~12 by adding a few drops of triethylamine solution (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After coating, each of the SAM surfaces was stored in their respective alkanethiol solutions in a dark environment until used to prepare the biosensor surfaces.

After incubation in their respective alkanethiol solutions, all SAM surfaces were sonicated with 100% (absolute) ethanol, rinsed with nano-pure water, dried with nitrogen gas and characterized by ellipsometry (GES 5 variable-angle spectroscopic ellipsometer, Sopra Inc., Palo Alto, CA), contact angle goniometry (CAM 200 optical contact-angle goniometer, KSV Instruments Inc., Monroe, CT), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, performed at NESCA/BIO, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). All XPS spectra were taken on a Kratos Axis-Ultra DLD spectrometer and analyzed by the Kratos Vision2 program to calculate the elemental compositions from peak area. Once characterization confirmed the quality of each type of SAM surface, sensor chips for SPR were prepared by mounting the SAM-coated surfaces on the cartridges that go into the Biacore X SPR instrument. The cartridges were then docked with the SPR micro-fluidics channel and promptly used to perform an adsorption experiment following the procedures outlined below in Section II.c (SPR Adsorption Experiments).

II.b. Host-Guest Peptide Model

For our adsorption studies, we used a unique custom-designed model peptide, which was introduced in our previous paper.36 This peptide, which was synthesized by Synbiosci Corporation, Livermore, CA, was designed with an amino acid sequence of TGTG-X-GTGT with zwitterionic end-groups, where G and T are glycine (-H side-chain) and threonine (-CH(CH3)OH side-chain), and X represents a “guest” amino acid residue, which can be selected among any of the 20 naturally occurring amino acid types. The threonine residues and the zwitterionic end-groups were selected to enhance aqueous solubility and provide additional molecular weight for SPR detection while the nonchiral glycine residues were selected to inhibit the formation of secondary structure, which, if present, would complicate the adsorption process and make the data more difficult to understand. The variable X residue was positioned in the middle of the peptide to best represent the characteristics of a mid-chain amino acid in a protein by positioning it relatively far from the zwitterionic end-groups. In this study, 12 different types of amino acids were used for the X residue to vary the overall characteristics of the peptides. These 12 amino acid residues are presented in Table 1. Each of these 12 peptides was synthesized and characterized by analytical HPLC and mass spectral analysis by Synbiosci Corporation, Livermore, CA, which showed that all of the peptides were ≥ 98 % pure.

Table 1.

12 designated amino acids used for the -X- residue in TGTG-X-GTGT; each amino acid has the structure of (-NH-CHR-CO-) with R presenting the side chain structure as shown here.

| -X- residue | Side Chain (R) | Property |

|---|---|---|

| Leucine (L) | -CH2-CH-(CH3)2 | Non-polar |

| Phenylalanine (F) | -CH2-C6H5 | Aromatic |

| Valine (V) | -CH(CH3)2 | Non-polar |

| Alanine (A) | -CH3 | Non-polar |

| Tryptophan (W) | -CH2-indole ring (C8H6N) | Aromatic |

| Threonine (T) | -CH(CH3)OH | Neutral polar |

| Glycine (G) | -H | Non-chiral |

| Serine (S) | -CH2-OH | Neutral polar |

| Asparagine (N) | -CH2-CO-NH2 | Neutral polar |

| Arginine (R) | -(CH2)3-NH-C(NH2)2+(pK=12.52)38 | Positively charged |

| Lysine (K) | -(CH2)4-NH3+ (pK=10.78)38 | Positively charged |

| Aspartic Acid (D) | -CH2COO− (pK=3.97)38 | Negatively charged |

II.c. SPR Adsorption Experiments

While the details of the development of our experimental procedures are presented in a prior publication, a brief description of these methods are presented here and in the following section.36 Adsorption experiments were conducted using a Biacore X SPR spectrometer (Biacore, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, pH=7.4; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) used as the running buffer, filtered and degassed before each SPR experiment.

Eight concentrations of each of the peptide solutions (0.039, 0.078, 0.156, 0.312, 0.625, 1.25, 2.50, 5.00 mg/mL) were prepared in the filtered and degassed 10 mM PBS through serial dilutions of stock solutions of the peptide in clean vials. The pH of each stock solution was adjusted to 7.4 with 0.1 N NaOH (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) or 0.1 M HCl (Mallinckrodt Chemical, Inc, Paris, KY) before dilution. The actual concentration of the stock and diluted peptide solution was then calibrated by BCA analysis (BCA protein assay kit, prod. 23225, Pierce, Rockford, IL) against a BSA standard curve and by the measurement of solution refractive index (AR 70 Automatic Refractometer, Reichert, Inc, Depew, NY).

Before the adsorption experiment, the SPR sensor chip was docked in the instrument and pretreated following a standard protocol that involved several injections of 0.3 vol. % Triton X-100 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) followed by a “wash” operation, which is necessary to obtain a stable SPR sensorgram response using this instrument. After the initial preparation step, each surface was prepared for an adsorption measurement by running 50 µL injections of concentrated peptide solution (5.0 mg/ml) over the SAM surface several times followed by PBS wash until a fully reversible adsorption signal was obtained. Then, eight different concentrations of each peptide solution were injected over each functionalized-SAM SPR chip in the random order with a flow rate of 50 µL/min followed by the PBS wash to desorb the peptide from the surface. Finally a blank buffer injection was administered to flush the injection port and a set of regeneration injections were then performed to prepare the surface for the next series of peptide sample injections.

II.d. Data Analysis

As described in our prior publication,36 the equations that are used for the determination of ΔGoads from the adsorption isotherms that are generated from the raw SPR data plots were derived based on the chemical potential of the peptide in its adsorbed state compared to being in bulk solution. The reversibility of the adsorption process is an essential condition for the application of these equations and was assessed for each peptide-surface system by comparing the SPR signal before the injection of peptide sample to the SPR signal after the period of desorption from SPR sensorgram under the same flow rate conditions. The SPR signal before adsorption and after desorption must be equal for a reversibly adsorbing system. ΔGoads values were only determined for peptide-surface systems that exhibited this characteristic behavior, with reversible thermodynamics then used to model the experimental data for the peptide-surface pairs that did not exhibit irreversible adsorption behavior. Once adsorption reversibility was ascertained, ΔGoads was determined by the following procedures (see reference 36 for a more detailed description of the development of these relationships).

SPR sensorgrams in the form of resonance units (RU; 1 RU = 1.0 pg/mm2)39 vs. time were recorded for six independent runs of each series of peptide concentrations over each SAM surface at 25 °C and the data were then used to generate isotherm curves for analysis by plotting the raw SPR signal vs. peptide solution concentration. During an SPR experiment to measure the adsorption of a peptide to a surface, the overall change in the SPR signal (i.e., the raw SPR signal) reflects both of the excess amount of adsorbed peptide per unit area, q (measured in RUs), and the bulk-shift response, which is linearly proportional to the concentration of the peptide in solution. This can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where Cb(moles/L, M) is the concentration of the peptide in bulk solution, C° is the peptide solution concentration under standard state conditions (taken as 1.0 M), m (RU/M) is the proportionality constant between the peptide concentration in the bulk solution and the bulk shift in the SPR response, K (unitless) is the effective equilibrium constant for the peptide adsorption reaction, and Q (RU) is amount of peptide adsorbed at surface saturation. Equation (1) was best-fitted to each isotherm plot of the raw SPR response vs. Cb by non-linear regression to solve for the parameters of Q, K, and m using the Statistical Analysis Software program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For a reversible adsorption process under equilibrium conditions,36 the concentration of the peptide at the surface (Cs (moles/L, M)) can be expressed as:

| (2) |

where δ (mm) is the thickness of the adsorbed layer and the unit of q is now (micro-moles/mm2), transferred from RU/ Mw where 1 RU = 1.0 pg/mm2 and Mw is the molecular weight (g/mole) of the peptide in test. When Cb approaches zero, under which conditions peptide-peptide interactions at the surface are minimized, the combination of equation (1) and equation (2) give:

| (3) |

where Q has the unit of (micro-moles/mm2), also transferred from RU/ Mw where 1 RU = 1.0 pg/mm2 and Mw is the molecular weight (g/mole) of the peptide in test. Now, based on the chemical potential of the peptide at the interface being equal to the chemical potential of the peptide in solution under equilibrium conditions36 and equation (3), the adsorption free energy can be expressed as:

| (4) |

Equation (4) thus provides a relationship for the determination of ΔGoads (kcal/mol) for peptide adsorption to a surface with minimal influence of peptide-peptide interactions based on experimentally determined parameters Q and K and the theoretically defined parameter δ, where R (kcal/mol K) is gas constant and T (K) is environmental temperature. The parameter δ is determined by assuming that its value is equal to twice the average outer radius of the peptide in solution with the peptide represented as being spherical in shape. The value of Rpep (radius of peptide molecule) is calculated as:36

| (5) |

where Vpep is the molecular volume of the peptide, ρ is the specific volume for a peptide or protein in solution, which is approximately 0.73 cm3/g,40 and Mw is the molecular weight of the peptide. For a peptide sequence of TGTG-X-GTGT peptide with X representing an amino acid with an average residue molecular weight of Mw = 118.9 Da,41 which results in Mw = 769.3 Da for the peptide, equation (5) gives a value of δ = 12.1 Å. Molecular dynamics simulations with similar peptides show this to be a very reasonable value for the adsorbed layer of this peptide.7, 33 Using theoretical values of δ, which are calculated for each peptide (see Table 2), combined with the values of Q and K, which are determined from the isotherm plots, ΔGoads can be determined for each peptide-SAM system using equation (4). Although this procedure for the calculation of ΔGoads involves this theoretical parameter, δ, it can be readily shown that the value of ΔGoads is actually fairly insensitive to the values of δ,36 thus providing a high level of robustness for the determination of ΔGoads using this method.

Table 2.

Calculated values of Mw and δ for each peptide.

| Guest Residue (-X-) | -L- | -F- | -V- | -A- | -W- | -T- | -G- | -S- | -N- | -R- | -K- | -D- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Mw (g/mole) | 764 | 798 | 750 | 722 | 837 | 752 | 708 | 738 | 765 | 807 | 779 | 765 |

| δ(Å) | 12.1 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 12.1 |

IV. Results and Discussion

IV.a. Surface Characterization

Table 3 presents the advancing water contact angle, layer thickness, and atomic composition for each of the nine SAM surfaces. All of the values in Table 3 fall within the expected range for these types of surfaces.42–49

Table 3.

Atomic composition (by XPS), advancing contact angle (by deionized water in air) and layer thickness (by ellipsometry) results for Au-alkanethiol SAM surfaces with various functionalities. An asterisk (*) indicates negligible value. (Mean (± 95% confidence interval), N = 3.)

| Surface Moiety | C (%) | S (%) | N (%) | O (%) | F (%) | Contact Angle (°) | Thickness (Ǻ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM–OH | 56.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.6) | * | 7.5 (0.2) | * | 15.5(2.1) | 13.0(1.0) |

| SAM–COOH | 47.6(1.8) | 1.6(0.1) | * | 7.6 (0.3) | * | 17.9(1.3) | 15.8(1.9) |

| SAM–(EG)3OH | 54.8 (0.3) | 2.3(0.1) | * | 13.2(0.6) | * | 32.0(3.3) | 19.0(3.0) |

| SAM–NH2 | 54.0 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.3) | * | 47.6(1.8) | 14.7 (2.5) |

| SAM–NHCOCH3 | 48.6 (0.6) | 1.7(0.1) | 4.0(0.1) | 6.0 (0.7) | * | 48.0(1.5) | 17.0(2.0) |

| SAM–COOCH3 | 45.4 (4.3) | 2.5 (0.2) | * | 10.8(0.6) | * | 62.8(1.7) | 11.0(4.8) |

| SAM–OC6H5 | 56.2 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.2) | * | 5.3 (0.9) | * | 80.0(4.1) | 14.4 (4.0) |

| SAM–OCH2CF3 | 44.1 (2.0) | 1.7(0.2) | * | 6.2(1.1) | 13.0(0.5) | 90.5 (0.8) | 16.1 (4.4) |

| SAM–CH3 | 64.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.2) | * | * | * | 110.0(3.0) | 11.0(1.0) |

The XPS results show that the surfaces contain the expected elemental composition with minimal levels of contamination, and the thicknesses indicate that each SAM surface is composed of a complete monolayer of the respective alkanethiol as opposed to a multi-layer. These results thus indicate that the SAM surfaces used in this study were of high quality and appropriately represented the intended surface chemistries for our peptide adsorption experiments.

IV.b. SPR Adsorption Analysis

Adsorption isotherms for each of our 108 peptide-SAM systems were generated from the raw experimental data by plotting the changes in RU vs. peptide solution concentration. Examples of the raw SPR data (RU vs. time) and the corresponding isotherms (RU vs. solution concentration) are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Values of the parameters Q, K, and m were then determined by fitting equation (1) to each of the data plots by non-linear regression using SAS, and these parameters were then used to calculate ΔGoads for each peptide-SAM system from equation (4). The resulting values for Q, K, and m are presented in the supplementary information section and the subsequent values of ΔGoads are presented in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, the peptides are grouped with respect to the side-group functionality of their guest (X) residue (i.e., nonpolar, polar, or charged characteristic). The SAM surfaces in Table 4 are listed at the top of the columns from left-to-right in order of their respective degree of hydrophilicity as determined by their contact angle values as presented in Table 2. Each of the SAMs represents a neutrally charged functional group, except for the COOH and NH2 SAMs, which represent negatively and positively charged groups, respectively, with pKd values of 7.4 and 6.5, respectively, based on bulk-solution conditions.50 The peptides in Table 4 are listed according to the standard hydrophobicity scale of the guest residue as reported by Hessa et al.,51 beginning with the most hydrophobic amino acid, with the guest amino acids separated into categories designated as nonpolar, polar, and charged residues.

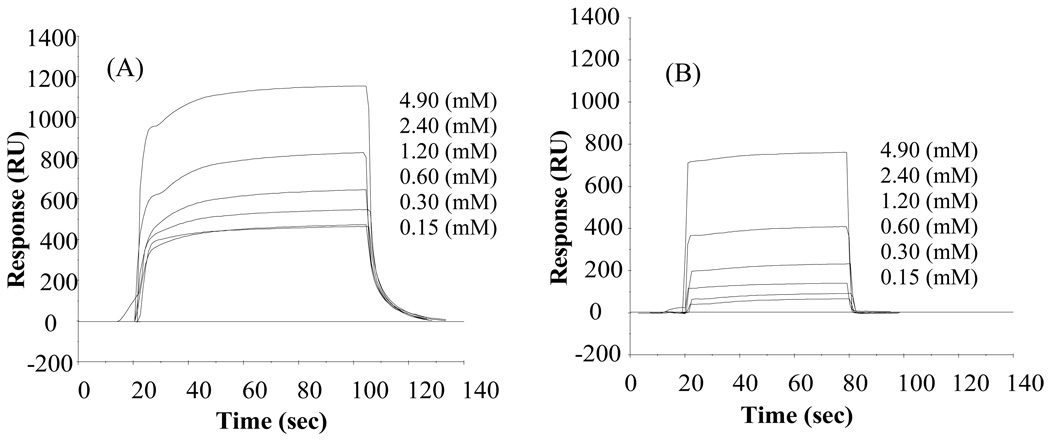

Figure 1.

Response curves (SPR signal (RU) vs. time for TGTG-L-GTGT on (A) SAM-CH3 and (B) SAM-OH surface. (Not all of the concentration curves are listed for clarity sake because some of the low concentration curves overlap one another and are thus not separately distinguishable).

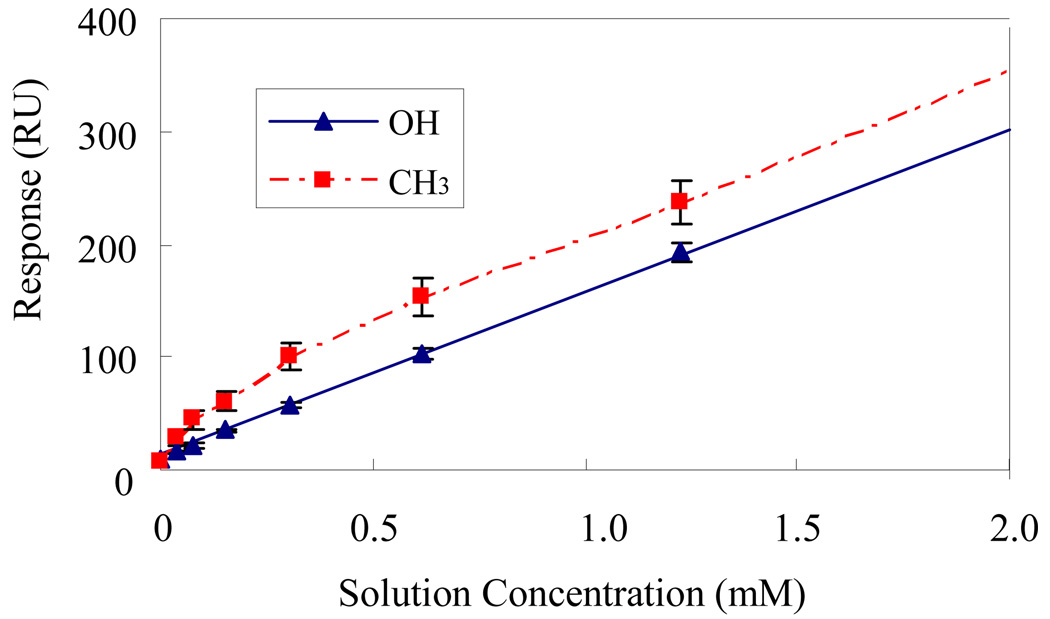

Figure 2.

Corresponding adsorption isotherm for TGTG-L-GTGT on both of SAM-OH solid line SAM-CH3 surfaces (dotted line). Note that the adsorption response plotted on the y-axis includes bulk-shift effects, which are linearly related to solution concentration. (Error bar represents 95% C.I., N = 6.)

Table 4.

Values of ΔGoads (kcal/mol) for peptide-SAM combinations. An asterisk (*) indicates a condition in which peptide adsorption was so strong that it was determined to be irreversible, in which case ΔGoads could not be determined. The guest amino acids (X) are ranked by a standard hydrophobicity scale51 from the most-to-least degree of hydrophobicity. (Mean (± 95% confidence interval), N=6.)

| -X- | SAM-OH | SAM-COOH | SAM-EG3OH | SAM-NH2 | SAM-NHCOCH3 | SAM-COOCH3 | SAM-OC6H5 | SAM-OCH2CF3 | SAM-CH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Polar Guest Residues | |||||||||

| -L- | −0.003 (0.001) | −1.30 (0.43) | −0.40 (0.28) | −2.34 (0.80) | −1.04 (0.30) | −2.06 (0.31) | −2.68 (0.72) | −3.09 (0.31) | −3.87 (0.69) |

| -F- | * | * | −0.30 (0.13) | * | −2.44 (0.40) | * | * | −3.97 (0.24) | −4.16 (0.16) |

| -V- | −0.002 (0.001) | −1.11 (0.31) | −0.26 (0.06) | −3.90 (0.12) | −0.16 (0.10) | * | * | −3.99 (0.22) | −4.40 (0.31) |

| -A- | * | * | −0.97 (0.36) | * | * | * | * | * | |

| -W- | −0.001 (0.001) | −1.14 (0.52) | −1.72 (0.33) | −2.71 (0.32) | −1.94 (0.45) | −0.92 (0.36) | −1.65 (0.60) | −3.42 (0.27) | −3.89 (0.34) |

| Polar Guest Residues | |||||||||

| -T- | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.87 (0.46) | −0.28 (0.15) | −3.15 (0.50) | −0.16 (0.09) | −0.40 (0.14) | −2.89 (0.75) | −2.81 (0.40) | −2.76 (0.28) |

| -G- | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.68 (0.36) | −0.30 (0.20) | −2.56 (0.32) | −1.86 6(0.20) | −1.18 (0.30) | −3.51 (0.22) | −3.30 (0.37) | −3.40 (0.39) |

| -S- | −0.002 (0.001) | −1.10 (0.10) | −0.34 (0.11) | −2.09 (0.98) | −1.49 (0.47) | −1.55 (0.26) | −3.20 (0.28) | −3.22 (0.24) | −2.75 (0.23) |

| -N- | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.86 (0.38) | −0.59 (0.11) | −3.22 (0.41) | −1.64 (0.23) | −1.37 (0.68) | −3.02 (0.16) | −3.41 (0.32) | −4.33 (0.62) |

| Charged Guest Residues | |||||||||

| -R- | −0.002 (0.001) | −1.53 (0.19) | −0.20 (0.10) | −3.03 (0.31) | −1.60 (0.80) | −1.17 (0.35) | −2.26 (0.82) | −3.45 (0.31) | −4.15 (0.55) |

| -K- | −0.001 (0.001) | −1.71 (0.19) | −0.19 (0.07) | −3.14 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.07) | −1.77 (0.07) | −3.35 (0.25) | −3.54 (0.45) | −3.34 (0.39) |

| -D- | −0.003 (0.001) | −1.06 (0.09) | −0.44 (0.14) | −3.75 (0.20) | −1.93 (0.52) | −1.34 (0.50) | −3.89 (0.23) | −3.59 (0.37) | −3.54 (0.60) |

In the following paragraphs, we address the correlation between peptide adsorption affinity for these SAM surfaces, as indicated by ΔGoads, and the hydrophobicity characteristics of both the SAM surfaces and the peptides involved. The overall value of ΔGoads is a summation of all the energetic contributions that influence the adsorption behavior of the peptide under standard state conditions at constant temperature and pressure. These interactions involve the changes in secondary bonding interactions of the functional groups making up the peptide and the SAM surface with each other and the surrounding water molecules and ions (enthalpic contributions), and the influence of the adsorption process on both the conformational state of the peptide, SAM, and the solvent (entropic contributions). From a thermodynamic point of view, the process of adsorption will spontaneously occur if ΔGoads < 0, with lower values of ΔGoads (i.e., more negative) indicating a stronger adsorption response.

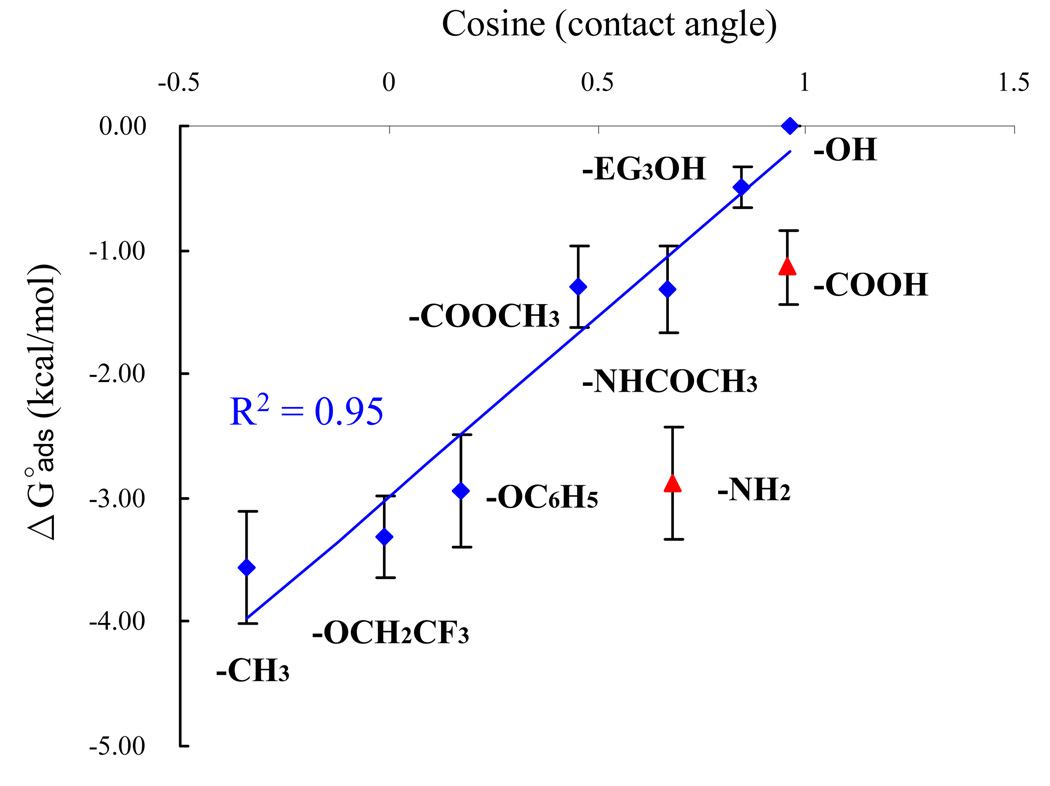

IV.c. Correlation Between Peptide Adsorption and Surface Hydrophobicity

Figure 3 presents a plot of the ΔGoads values from Table 4 versus the respective cosine of the contact angle values for each SAM surface (contact angle values are presented in Table 3). The ΔGoads values shown in Figure 3 represent the mean (± 95% confidence intervals (CI)) of the ΔGoads values from all of the host-guest peptides that exhibited reversible adsorption behavior on each SAM surface (i.e., peptides with X = A, F, and V, which tended to adsorb irreversibly, were excluded from these average values). The cosine of contact angle values here, which can be related to the free energy of replacement of water at the surface with the adsorbed peptide monolayer,44 provide an energetic scale for the peptide adsorption behavior on the different surfaces. As clearly indicated in Figure 3, the lowest mean ΔGoads value (i.e., greatest adsorption affinity) was obtained on the SAM–CH3 surface with the highest contact angle value and the highest mean ΔGoads value (i.e., least adsorption affinity) was obtained on the SAM–OH surface with the lowest contact angle value. These results also clearly show that this general relationship holds for each of the neutrally charged SAM surfaces, with peptide adsorption affinity increasing (i.e., ΔGoads gets more negative) in a manner that strongly correlates in a linear manner with the hydrophobicity of the SAM surfaces over the full range of contact angles. The physical meaning behind this linear relationship can then be understood as reflecting a decrease in the energetic cost of displacing interfacial water between the surface and our peptide models as surface energy decreases, resulting in a concomitantly stronger free energy change (more negative ΔGoads). However, in addition to the general linear trend in figure 3, the substantial amount of scatter around each data point from this trend-line suggests that specific functional group interactions also substantially influence the adsorption behavior. This same general trend is apparent for the charged SAM surfaces, but with an additional contribution of adsorption affinity due to the presence of relatively strong electrostatic interactions, which was expected based on the zwitterionic nature of each of the peptides.

Figure 3.

ΔGoads (kcal/mol) vs. cosine (contact angle) for TGTG-X-GTGT on SAM surfaces with various functionalities. The ΔGoads values represent the average value of all of the host-guest peptides that exhibited reversible adsorption behavior on each SAM surface (i.e., peptides with X = A, F, and V, which tended to adsorb irreversibly, were excluded from these average values). The blue line shows the linear regression for the non-charged SAM surfaces with r2=0.95. (The error bar represents the 95% C.I. with N = 9.)

IV.d. Correlation Between Peptide Adsorption and Amino Acid Hydrophobicity Scale

As noted in the previous subsection, Figure 3 shows a strong correlation between the hydrophobicity of the SAM surface and the strength of adsorption for this set of peptides. In addition to this relationship, the adsorption behavior of the peptides can also be evaluated as a function of their relative degree of hydrophobicity based on the amino acid hydrophobicity scale of Hessa et al.51 To investigate these relationship, we separated the SAM surfaces into three general groups based on their water contact angle: strongly hydrophobic (contact angle > 65°), hydrophilic (contact angle < 65°), and charged (SAM-COOH and SAM-NH2) and then plotted ΔGoads for each of the host-guest peptides in rank order from left to right with respect to their relative degree of hydrophobicity (see Fig. 4 – Fig. 6).

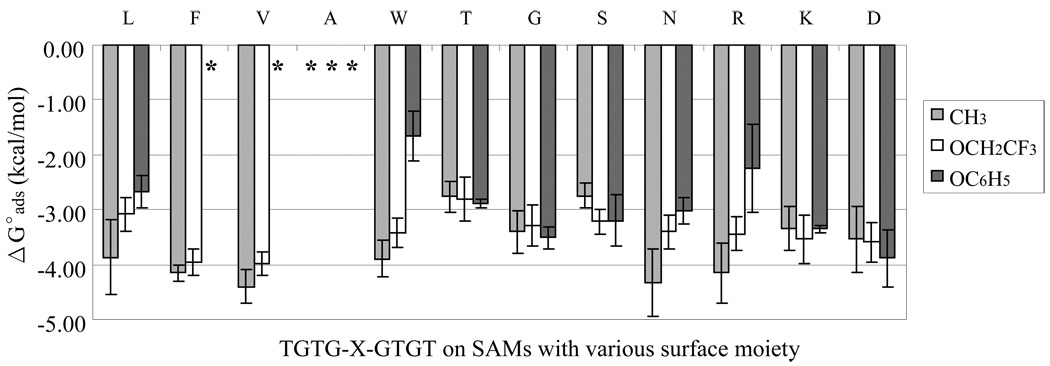

Figure 4.

Comparisons of ΔGoads for each peptide on the hydrophobic surfaces (water contact angle > 65°): SAM–CH3, SAM–OCH2CF3 and SAM–OC6H5 surfaces. The amino acid label across the top of each set of columns designates the X residue of the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide. Peptides are ordered by a standard hydrophobicity scale51 from the most-to-least degree of hydrophobicity. (An asterisks (*) indicates that adsorption was irreversible. The error bars represent the 95% C.I. with N = 6.)

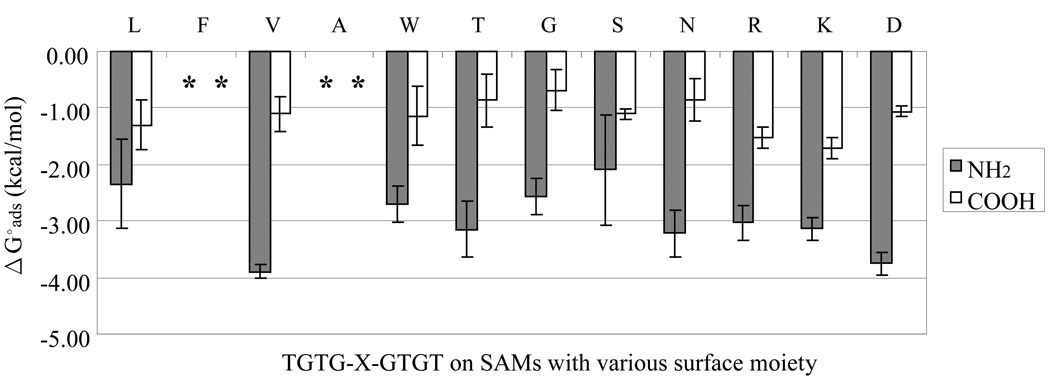

Figure 6.

Comparisons of ΔGoads for each peptide on the charged surfaces: SAM–COOH and SAM–NH2 surfaces. The amino acid label across the top of each set of columns designates the X residue of the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide. An asterisks (*) indicates that adsorption was irreversible. The error bar represent the 95% CI. with N = 6.)

IV.d.1. Hydrophobic Surfaces

The SAM-CH3, SAM-OCH2CF3 and SAM-OC6H5 surfaces are regarded as hydrophobic because of their high surface contact angle (> 65°). The presence of hydrophobic groups on these surfaces should be reflected in their ability to interact with hydrophobic groups presented by molecules in aqueous media. Although still not fully understood, hydrophobic interactions are believed to originate from the perturbed structure of water molecules adjacent to nonpolar functional groups compared to the bulk solvent such that when two non-polar functional groups are brought together, part of this ordered hydration shell is released to the bulk solution with a corresponding increase in system entropy and subsequent decrease in free energy. 36, 52–54

Fig. 2 shows the ΔGoads of our set of 12 different guest amino acid residues for our host-guest TGTG-X-GTGT peptides on the hydrophobic SAM surfaces. For this peptide model, the peptides differ only by the side-chain structure of the middle guest amino acid residue (X) and thus the characteristics of this amino acid can be expected to primarily be responsible for the differences in the observed adsorption behavior of the peptide. From the results shown in Fig. 4, it should first be noted that when T and G were used as the guest residues, the guest residue had the same characteristics as the host amino acid residues. For these cases, the peptides adsorbed with moderately strong adsorption affinity to each of these three hydrophobic SAM surfaces with an overall average of ΔGoads= – 3.1 kcal/mol. Comparison of this value with the ΔGoads values of the full set of peptides, which range from – 2.5 to – 4.5 kcal/mol, provides an indication of the relative strength of adsorption for each guest amino acid compared to G and T amino acids, which fall in the middle of this hydrophobicity scale.

Taking into consideration that irreversible adsorption indicates binding affinity that was too strong to be measured using our adsorption isotherm method, it is apparent from Fig. 4 that in several cases substitution with a guest residue that rank relatively high on the hydrophobicity scale (e.g., F, V, and A with aromatic, aliphatic, and aliphatic side chains, respectively) resulted in relatively high binding affinity to these surfaces, as expected. This behavior, however, was not entirely consistent, with several of the peptides with a lower degree of hydrophobicity compared with T and G (e.g., N and R, which have polar and positively charged side chains, respectively) exhibiting as strong, if not stronger, binding affinity than the peptides with guest amino acids that rank higher on the hydrophobicity scale (e.g., L and W amino acids with aliphatic and aromatic side chains, respectively). These results indicate that the adsorption behavior of an unstructured peptide to a hydrophobic surface is not strongly influenced by the hydrophilicity of the amino acid residues making up the peptide. We propose the following reasons to explain this somewhat unexpected adsorption behavior. First, each amino acid in our host-guest peptide model contains non-polar functional groups (e.g., CH, CH2 and CH3 groups). Secondly, we purposely designed our peptide model to be unstructured and flexible in order to prevent the formation of secondary structure. We propose that the combination of these characteristics enabled these peptides to interact with their aliphatic and/or aromatic segments hydrophobically adsorbed to the SAM surfaces while their hydrophilic functional groups were positioned in a manner to remain hydrated and away from the hydrophobic groups on the SAM surface. This behavior may thus explain why even the peptide with the most hydrophilic guest residue (i.e., D) adsorbed to the hydrophobic surfaces with an affinity that was just as strong, if not stronger, than the affinity of the most hydrophobic guest residue (i.e., L).

IV.d.2. Neutral Hydrophilic Surfaces

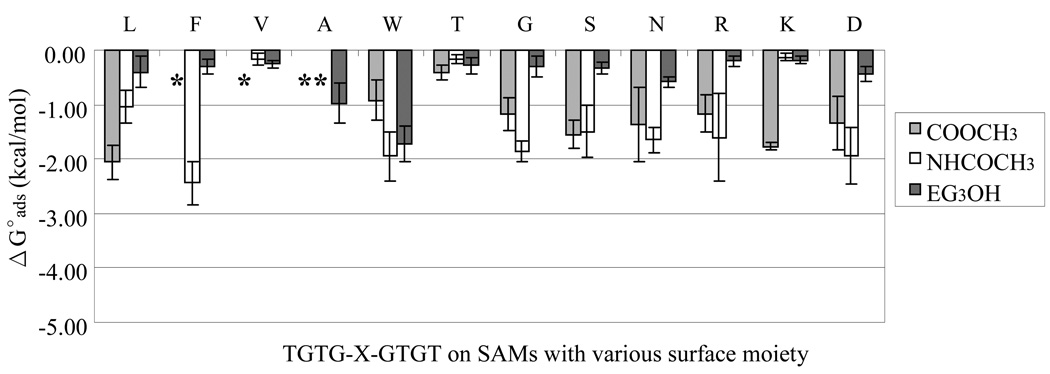

The SAM–COOCH3, SAM–NHCOCH3, SAM–EG3-OH, and SAM-OH surfaces are regarded as hydrophilic because of their relatively low surface contact angle (< 65°) compared with the hydrophobic SAMs. For this set of SAM surfaces, the SAM–NHCOCH3 and SAM–COOCH3 are moderately hydrophilic (contact angles between 45° to 65°) with a combination of both hydrophobic and hydrogen bondable hydrophilic groups, while the SAM–EG3OH and SAM-OH surfaces are much more hydrophilic (contact angles < 35°) and are considered to possess only hydrogen bondable groups. Fig. 5 shows the ΔGoads values for the 12 different guest residues in our host-guest peptide models on the SAM–NHCOCH3, SAM–COOCH3 and SAM–EG3OH surfaces, with the results for the SAM-OH being omitted due to the fact that ΔGoads = 0.0 kcal/mol for each of the reversibly adsorbing peptides on this surface.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of ΔGoads for each peptide on neutrally charged relatively hydrophilic surfaces (water contact angle < 65°): SAM–COOCH3, SAM–NHCOCH3, and SAM–EG3OH surfaces. The amino acid label across the top of each set of columns designates the X residue of the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide. The SAM-OH surface is not included in this plot because ΔGoads = 0.0 for each reversibly adsorbed peptide on this surface. (An asterisks (*) indicates that adsorption was irreversible. The error bar represent the 95% C.I. with N = 6.)

Considering the adsorption affinity of the peptides to the moderately hydrophilic SAM–NHCOCH3 and SAM–COOCH3 surfaces, the results in Fig. 5 show similar trends as with the hydrophobic surfaces shown in Fig. 4 in terms of a lack of strong correlation as a function of the peptide hydrophobicity scale. These surfaces, however, did exhibit significantly lower binding affinity for the peptides in general compared to the hydrophobic SAM surfaces, with ΔGoads values generally falling between – 1.0 and – 2.0 kcal/mol. The lack of strong correlation as a function of the peptide hydrophobicity scale on these SAM surfaces is attributed to the presence of the hydrophobic groups on both of the surfaces combined with the hydrophobic groups present in each of the peptides as discussed in the previous section. The significantly lower adsorption affinity of the peptides to these surfaces is attributed to the ability of the hydrophilic groups of the SAM–NHCOCH3 and SAM–COOCH3 surfaces to form hydrogen bonds with water, thus making it more difficult for the peptides to displace the adsorbed water layer from the surface. Despite their more hydrophilic nature, these SAM surfaces still yielded a greater incidence of irreversible adsorption for the peptides that possessed strongly hydrophobic guest residues (i.e., F, V, and A).

As shown in Fig. 5 and Table 4, the adsorption affinity of the peptides on the most hydrophilic SAM surfaces, SAM–EG3OH and SAM-OH, was very low. Except for a couple notable exceptions (i.e., A and W guest residues), the SAM–EG3OH surfaces provided ΔGoads > – 0.5 kcal/mol, thus showing relatively high resistance to adsorption, while the SAM-OH surface generally provided even lower adsorption affinity with ΔGoads = 0.0 kcal/mol. The non-adsorptive behavior for both of these SAM surfaces can be understood to result from a tendency for the functional groups on the SAM surface and the hydrogen-bondable groups of the peptides to form hydrogen bonds with the surrounding water molecules just as strongly as the tendency to form hydrogen bonds between the peptide and the SAM surface, thus providing little thermodynamic driving force to preferentially favor peptide adsorption. Notable exceptions for the adsorption behavior on the SAM-OH surface were found for the highly hydrophobic guest residues of F and A, which exhibited irreversible adsorption behavior even on this surface. In the case of A as guest residue, which has a single methylene side-group, it is believed that the relatively small size of the OH group of the monolayer enabled the relatively compact, hydrophobic side group of analine to insert in between the OH groups of the SAM surface to hydrophobically adsorb to the underlying alkane chains of the monolayer. This contention is further supported by the fact irreversible adsorption behavior for these peptides was not observed on the SAM-EG3OH surface, in which case it is proposed that the increased thickness of the EG3OH surface groups creates a thicker surface layer that sterically prevents these peptides from being able to come into direct contact with the underlying alkane chains of the monolayer.

While the irreversible adsorption behavior of the peptide sequence with F as guest residue to the hydrophobic SAM surfaces was not unexpected, its irreversible adsorption to several of the more hydrophilic SAM surfaces, including the OH-SAM, was surprising. These results, however, are in agreement with comparisons of the adsorption behavior of individual amino acids to bare silica in water as measured by liquid chromatography which have shown that phenylalanine amino acids (F) adsorb to a silica surface with an affinity approximately three times stronger that tryptophan (W).55, 56 Currently we still have no explanation for this behavior and we are seeking to develop a better understanding of peptide-surfaces interactions to further investigate this behavior.

IV.d.3. Charged SAM Surfaces

The SAM–COOH and SAM–NH2 surfaces were chosen to provide negatively charged and positively charged surfaces, respectively, in a solution with a pH of 7.4, with the pK values of these surfaces measured as 7.4 and 6.5, respectively, based on bulk solution conditions.50 Fig. 6 shows the ΔGoads values for the 12 different guest residues with our model peptide on the SAM–COOH and SAM–NH2 surfaces, with these results providing values in some cases that were expected and in other cases that were rather surprising.

When considering only the adsorption behavior of the charged peptides, the results exhibit the generally anticipated trends, although the differences between the oppositely charged peptides for a given charged surface are smaller than expected. The peptide with the negatively charged D guest residue (-COOH side group, pK = 3.9)38 did show slightly higher affinity for the positively charged SAM-NH2 surface than the peptides with the positively charged R and K guest residues (-NH2 side groups, pK = 12.0 and 10.0, respectively),38 and the positively charged peptides with the R and K guest residues did show slightly higher affinity for the negatively charged SAM-COOH surface compared to the negatively charged peptide with the D guest residue. What was surprising for each of these cases, however, was the fact that for all three of these charged peptides, adsorption affinity was significantly higher for the SAM-NH2 surface than the SAM-COOH surface independent of whether the net charge of the peptide was the same or opposite of the charged surface. In fact, this same trend in adsorption behavior was also found for the peptides with the noncharged guest amino acid residues. This difference is attributed to the relatively hydrophobic character of the SAM-NH2 surface compared to the strongly hydrophilic surface of the SAM-COOH surface, with hydrophobic effects thus dominating over the superimposed electrostatic effects for this peptide adsorption system.

Another surprising finding from the results for the charged-SAM surfaces is that there is no obvious trend of the peptides with noncharged guest residues adsorbing to the charged surfaces differently from those with the charged guest residues. This interesting and unexpected behavior is attributed to the fact that each of the peptides in this TGTG-X-GTGT peptide model was synthesized with zwitterionic end groups, with these oppositely charged end groups being separated by seven intervening mid-chain amino acid residues. This peptide design thus provides a mechanism for each of the peptides to interact with the charged SAM surfaces with its oppositely charged end group electrostatically attracted to the SAM surface with the same-charged end group remaining hydrated and relatively far from the surface, with these types of interactions possibly controlling the overall adsorption behavior. The significant differences between the different peptides may then be caused by the influence of the guest residue on the conformational behavior of the peptide, which can be expected to influence the manner in which the zwitterionic end groups are able to interact with each surface.

IV.e. Relevance of Results to Protein Adsorption Behavior

Many published studies (both experimental8, 36, 55, 57 and computational7, 23–26, 33) have obtained free energy values for peptide adsorption to surfaces that fall within a similar range of values as we have determined is this study, and these studies have also shown that adsorption free energy generally becomes more negative (i.e., stronger adsorption) as a peptide becomes larger due to the increase in the number of peptide-surface interactions that are involved. This size effect, combined with our present findings of irreversible adsorption behavior for even these small peptides on several of these SAM surfaces, suggests that the adsorption of whole proteins, which involve orders of magnitude greater number of interactions between amino acids and surface functional groups, can be expected to be irreversible as a general rule on most surfaces. This is especially the case as surfaces become more hydrophobic, which tend to cause a protein to unfold and spread out over a surface,29, 58, 59 which substantially increases the number of amino acid-surface interactions and contributes to the overall binding affinity.

In our host-guest peptide model, we specifically designed the host sequence to contain threonine and glycine amino acids to provide hydrophilic character and to minimize the development of secondary structure, respectively, as an attempt to create a system whose adsorption response was dominated by differences caused by the presence of the guest amino acid residues. However, SPR experiments do not provide information regarding the orientation or the conformation of the peptides when they adsorb. Therefore, we cannot determine whether the observed differences in peptide adsorption behavior are directly due to the interactions of the guest peptides with the surfaces and their orientations on the surfaces (e.g., whether a guest amino acid is adsorbed with its side-group facing towards the SAM surface or away from it), or if the differences in peptide adsorption behavior are actually due to the influence of the guest residues on the conformational behavior of the overall peptide, which will also influence its adsorption behavior. Because of these difficulties, it is not possible to directly translate the results from these peptide adsorption studies to predict actual protein adsorption behavior. When an actual protein adsorbs to a surface, its amino acid residues are presented to the surface in a much more restrained manner and, in addition, the adsorption behavior is influenced by adsorption-induced structural changes in the protein itself. Differences between the peptide adsorption results obtained from these present studies and protein adsorption behavior is especially apparent when considering our results for the SAM surface with the 3-mer segment of ethylene glycol (SAM-EG3-OH). In this case we were surprised to find a measurable adsorption response, although still relatively small, given that it has been well documented that polyethylene glycol (PEG) functionalized surfaces are highly resistant to protein adsorption.60–64 These results suggest that the small, flexible characteristics of our peptides coupled with the short chain length of the EG3-OH functional groups enabled these peptides to interact with the EG3-OH chains in a manner that is distinctly different than a large structured protein.

While these results thus cannot be directly applied to predict protein adsorption behavior, the main objectives of generating this large data set were to obtain insight into the adsorption behavior of short peptides and to support the development and validation of molecular simulation methods that do provide the potential to actually predict protein adsorption behavior.28 Molecular simulation methods, using empirical force fields, have already been well developed to simulate the folding/unfolding behavior of peptides and proteins in aqueous solution.65–68 Methods, however, have not yet been validated to confidently simulate the adsorption behavior of peptides and proteins to functionalized surfaces. The development of these methods require that the force field parameters that are used for the simulation of peptide adsorption behavior must first be properly evaluated, balanced, and validated so that they are able to accurately reflect the atomistic-level interactions that govern peptide adsorption behavior. This can only be achieved if a benchmark data set is first available against which molecular simulation results can be directly compared; the results presented in Table 4 provide this data set. We are currently conducting molecular simulations for these same peptide-SAM surface systems and calculating adsorption free energy using the CHARMM force field.28, 33 From comparisons between these simulations and the experimental data provided from this present study, force field parameters will be able to be evaluated, tuned, and validated to accurately represent peptide adsorption behavior. Once validated, these methods will then be able to be combined with the methods already available to simulate protein folding/unfolding behavior to enable both protein-surface interactions and adsorption-induced unfolding processes to be represented in the same simulation, thus providing the capability to accurately simulate the whole process of protein adsorption on a surface. Due to current limitations in computational power, such simulations will most likely be limited to the adsorption behavior of individual proteins at the present time. However, as computational power continues to grow, it is readily foreseeable that these methods will be able to be extended to the adsorption behavior of multiple proteins at the same time in order to simulate complex protein-protein interactions, such as Vroman effects and multilayer protein adsorption.

V. Conclusions

In a preceding paper, we developed and introduced a new experimental method for the characterization of peptide adsorption behavior that enabled ΔGoads to be determined using SPR spectroscopy in a manner that minimizes the effects of peptide-peptide interactions at the adsorbent surface and provides a direct means of determining bulk shift effects.36 In this paper we present results from the application of this method to characterize the adsorption behavior of a large series of 108 different peptide-SAM systems involving 12 different zwitterionic peptides (TGTG-X-GTGT with X = V, A, G, L, F, W, K, R, D, S, T and N; charged N and C termini) on nine different SAM surfaces (SAM–Y with Y=CH3, OH, NH2, COOH, OC6H5, (EG)3OH, NHCOCH3, OCH2CF3 and COOCH3). The results from these studies indicate that ΔGoads for this model peptide on non-charged surfaces generally correlates in a linear manner with the hydrophobicity of the surface as represented by its water contact angle, with specific interactions between the functional groups of the peptide and the SAM surfaces playing a secondary, but still significant role. Peptide adsorption behavior to the charged SAM surfaces also followed these same general trends, but with electrostatic effects providing an additional mechanism to enhance adsorption affinity, even for zwitterionic peptides with a net same-charge characteristic as the adsorbent surface.

This benchmark data set provides fundamental insights into the governing factors that influence protein adsorption behavior; and just as importantly, provides a benchmark experimental data set that is needed for the evaluation, adjustment, and validation of force field parameters for the development of molecular simulation methods that can be applied to accurately simulation protein adsorption behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge NIH for funding support for this research (NIBIB grant # R01 EB006163). We also would like to thank Dr. James E. Harriss of Clemson University for assistance with the various aspects of SPR biosensor chip fabrication for these studies; and Ms. Megan Grobman, Dr. Lara Gamble, and Dr. David Castner of the University of Washington for assistance with surface characterization with XPS under the funding support by NIBIB (grant # EB002027).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hruby VJ, Matsunaga TO. Applications of Synthetic Peptides. In: Grant GA, editor. Synthetic peptides: a user's guide. 2nd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 292–376. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Laursen RA. Artificial antifreeze polypeptides: alpha-helical peptides with KAAK motifs have antifreeze and ice crystal morphology modifying properties. FEBS Lett. 1999;455(3):372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00906-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corradin G, Spertini F, Verdini A. Medicinal application of long synthetic peptide technology. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2004;4(10):1629–1639. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.10.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava AK, Castillo G, Wergedal JE, Mohan S, Baylink DJ. Development and Application of a Synthetic Peptide-Based Osteocalcin Assay for the Measurement of Bone Formation in Mouse Serum. Calcified Tissue International. 2000;67(3):255. doi: 10.1007/s002230001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen Z, Yan H, Zhang Y, Mernaugh RL, Zeng X. Engineering peptide linkers for scFv immunosensors. Anal Chem. 2008;80(6):1910–1917. doi: 10.1021/ac7018624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulmschneider MB, Ulmschneider JP. Membrane adsorption, folding, insertion and translocation of synthetic trans-membrane peptides. Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25(3):245–257. doi: 10.1080/09687680802020313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raut VP, Agashe MA, Stuart SJ, Latour RA. Molecular dynamics simulations of peptide-surface interactions. Langmuir. 2005;21(4):1629–1639. doi: 10.1021/la047807f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernekar VN, Latour RA. Adsorption thermodynamics of a mid-chain peptide residue on functionalized SAM surfaces using SPR. Mater. Res. Innovations. 2005;9:337–353. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baneyx F, Schwartz DT. Selection and analysis of solid-binding peptides. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18(4):312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun R, Sarikaya M, Schulten K. Genetically engineered gold-binding polypeptides: structure prediction and molecular dynamics. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2002;13(7):747–757. doi: 10.1163/156856202760197384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamerler C, Oren EE, Duman M, Venkatasubramanian E, Sarikaya M. Adsorption kinetics of an engineered gold binding Peptide by surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy and a quartz crystal microbalance. Langmuir. 2006;22(18):7712–7718. doi: 10.1021/la0606897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zin MT, Ma H, Sarikaya M, Jen AK. Assembly of gold nanoparticles using genetically engineered polypeptides. Small. 2005;1(7):698–702. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serizawa T, Sawada T, Matsuno H. Highly specific affinities of short peptides against synthetic polymers. Langmuir. 2007;23(22):11127–11133. doi: 10.1021/la701822n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serizawa T, Sawada T, Matsuno H, Matsubara T, Sato T. A peptide motif recognizing a polymer stereoregularity. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(40):13780–13781. doi: 10.1021/ja054402o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zemel A, Ben-Shaul A, May S. Membrane perturbation induced by interfacially adsorbed peptides. Biophys J. 2004;86(6):3607–3619. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.033605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladokhin AS, White SH. Interfacial folding and membrane insertion of a designed helical peptide. Biochemistry. 2004;43(19):5782–5791. doi: 10.1021/bi0361259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemel A, Ben-Shaul A, May S. Perturbation of a lipid membrane by amphipathic peptides and its role in pore formation. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34(3):230–242. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hristova K, White SH. An experiment-based algorithm for predicting the partitioning of unfolded peptides into phosphatidylcholine bilayer interfaces. Biochemistry. 2005;44(37):12614–12619. doi: 10.1021/bi051193b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White SH, Wimley WC. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376(3):339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ladokhin AS, White SH. Protein chemistry at membrane interfaces: non-additivity of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. J Mol Biol. 2001;309(3):543–552. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jencks WP. On the attribution and additivity of binding energies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(7):4046–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y, Dominy BN, Latour RA. Comparison of solvation-effect methods for the simulation of peptide interactions with a hydrophobic surface. J Comput Chem. 2007;28(11):1883–1892. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basalyga DM, Latour RA., Jr Theoretical analysis of adsorption thermodynamics for charged peptide residues on SAM surfaces of varying functionality. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64(1):120–130. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latour RA, Jr, Hench LL. A theoretical analysis of the thermodynamic contributions for the adsorption of individual protein residues on functionalized surfaces. Biomaterials. 2002;23(23):4633–4648. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latour RA, Jr, Rini CJ. Theoretical analysis of adsorption thermodynamics for hydrophobic peptide residues on SAM surfaces of varying functionality. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60(4):564–577. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agashe M, Raut V, Stuart SJ, Latour RA. Molecular simulation to characterize the adsorption behavior of a fibrinogen gamma-chain fragment. Langmuir. 2005;21(3):1103–1117. doi: 10.1021/la0478346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latour RA. Molecular simulation of protein-surface interactions: Benefits, problems, solutions, and future directions (Review) Biointerphases. 2008;3(3) doi: 10.1116/1.2965132. FC2–FC12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latour RA. Biomaterials: Protein-Surface Interactions. In: Bowlin GEWaGL., editor. The Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Bioengineering. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Informa Healthcare; 2008. pp. 270–284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynie DT. Biological thermodynamics. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. Gibbs free energy-applications; pp. 134–199. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norde W. Protein adsorption at solid surfaces: A thermodynamic approach. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994;66:491–496. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh N, Husson SM. Adsorption thermodynamics of short-chain peptides on charged and uncharged nanothin polymer films. Langmuir. 2006;22(20):8443–8451. doi: 10.1021/la0533765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien CP, Stuart SJ, Bruce DA, Latour RA. Modeling of Peptide Adsorption Interactions with a Poly(lactic acid) Surface. Langmuir. 2008;24(24):14115–14124. doi: 10.1021/la802588n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vericat C, Vela ME, Salvarezza RC. Self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiols on Au(111): surface structures, defects and dynamics. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2005;7(18):3258–3268. doi: 10.1039/b505903h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Using self-assembled monolayers to understand the interactions of man-made surfaces with proteins and cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:55–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei Y, Latour RA. Determination of the adsorption free energy for peptide-surface interactions by SPR spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2008;24(13):6721–6729. doi: 10.1021/la8005772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Chen S, Li L, Jiang S. Improved Method for the Preparation of Carboxylic Acid and Amine Terminated Self-Assembled Monolayers of Alkanethiolates. Langmuir. 2005;21(7):2633–2636. doi: 10.1021/la046810w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandapativ RR, Mahalakshmi A, Moganty RR. Specific interactions between amino acid side chains - a partial molar volume study. Can. J. Chem. 1988;66:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 39.BIAtechnology Handbook. Uppsala: Biacore AB; 1998. pp. 4-1–4-4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harpaz Y, Gerstein M, Chothia C. Volume changes on protein folding. Structure. 1994;2(7):641–649. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voet D, Voet JG, Pratt CW. Fundamentals of Biochemistry. 2002:80–81. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sigal GB, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Effect of Surface Wettability on the Adsorption of Proteins and Detergents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120(14):3464–3473. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silin VV, Weetall H, Vanderah DJ. SPR Studies of the Nonspecific Adsorption Kinetics of Human IgG and BSA on Gold Surfaces Modified by Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) J Colloid Interface Sci. 1997;185(1):94–103. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1996.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegel RR, Harder P, Dahint R, Grunze M, Josse F, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. On-line detection of nonspecific protein adsorption at artificial surfaces. Anal Chem. 1997;69(16):3321–3328. doi: 10.1021/ac970047b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mark SS, Sandhyarani N, Zhu C, Campagnolo C, Batt CA. Dendrimer-functionalized self-assembled monolayers as a surface plasmon resonance sensor surface. Langmuir. 2004;20(16):6808–6817. doi: 10.1021/la0495276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toworfe GK, Composto RJ, Shapiro IM, Ducheyne P. Nucleation and growth of calcium phosphate on amine-, carboxyl- and hydroxyl-silane self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials. 2006;27(4):631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubois LH, Nuzzo RG. Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of Model Organic Surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1992;43(1):437–463. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanahashi M, Matsuda T. Surface functional group dependence on apatite formation on self-assembled monolayers in a simulated body fluid. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;34(3):305–315. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970305)34:3<305::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sethuraman A, Han M, Kane RS, Belfort G. Effect of Surface Wettability on the Adhesion of Proteins. Langmuir. 2004;20(18):7779–7788. doi: 10.1021/la049454q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fears KP, Creager SE, Latour RA. Determination of the Surface pK of Carboxylic- and Amine-Terminated Alkanethiols Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2008;24(3):837–843. doi: 10.1021/la701760s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hessa T, Kim H, Bihlmaier K, Lundin C, Boekel J, Andersson H, Nilsson I, White SH, von Heijne G. Recognition of transmembrane helices by the endoplasmic reticulum translocon. Nature. 2005;433(7024):377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature03216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiggins PM. Hydrophobic hydration, hydrophobic forces and protein folding. Physica A: Statistical and Theoretical Physics. 1997;238(1–4):113. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsai YS, Lin FY, Chen WY, Lin CC. Isothermal titration microcalorimetric studies of the effect of salt concentrations in the interaction between proteins and hydrophobic adsorbents. Colloids Surf., A. 2002;197(1–3):111. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perkins TW, Mak DS, Root TW, Lightfoot EN. Protein retention in hydrophobic interaction chromatography: modeling variation with buffer ionic strength and column hydrophobicity. J. Chromatogr. A. 1997;766(1–2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basiuk VA. Thermodynamics of adsorption of amino acids, small peptides, and nucleic acid components on silica adsorbents. In: Malmsten M, editor. Biopolymers at Interfaces. Vol. Chapt. 3. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998. pp. 55–87. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uddin MS, Hidajat K, Ching CB. Liquid chromatographic evaluation of equilibrium and kinetic parameters of large molecule amino acids on silica gel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1990;29(4):647–651. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Latour RA, Trembley SD, Tian Y, Lickfield GC, Wheeler AP. Determination of apparent thermodynamic parameters for adsorption of a midchain peptidyl residue onto a glass surface. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000;49(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200001)49:1<58::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agnihotri A, Siedlecki CA. Time-Dependent Conformational Changes in Fibrinogen Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir. 2004;20(20):8846–8852. doi: 10.1021/la049239+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sivaraman B, Fears KP, Latour RA. Investigation of the Effects of Surface Chemistry and Solution Concentration on the Conformation of Adsorbed Proteins Using an Improved Circular Dichroism Method. Langmuir. in press doi: 10.1021/la8036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Latour RA. Thermodynamic perspectives on the molecular mechanisms providing protein adsorption resistance that include protein-surface interactions. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78(4):843–854. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gref R, Luck M, Quellec P, Marchand M, Dellacherie E, Harnisch S, Blunk T, Muller RH. ‘Stealth’ corona-core nanoparticles surface modified by polyethylene glycol (PEG): influences of the corona (PEG chain length and surface density) and of the core composition on phagocytic uptake and plasma protein adsorption. Colloids Surf., B. 2000;18(3–4):301. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee SW, Laibinis PE. Protein-resistant coatings for glass and metal oxide surfaces derived from oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated alkyltrichlorosilanes. Biomaterials. 1998;19(18):1669. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miqin Z, Desai T, Ferrari M. Proteins and cells on PEG immobilized silicon surfaces. Biomaterials. 1998;19(10):953. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ito Y, Hasuda H, Sakuragi M, Tsuzuki S. Surface modification of plastic, glass and titanium by photoimmobilization of polyethylene glycol for antibiofouling. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(6):1024. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck DAC, Daggett V. Methods for molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding/unfolding in solution. Methods. 2004;34(1):112. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brooks CL. Simulations of protein folding and unfolding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8(2):222. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fersht AR. On the simulation of protein folding by short time scale molecular dynamics and distributed computing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(22):14122–14125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182542699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaeffer RD, Fersht A, Daggett V. Combining experiment and simulation in protein folding: closing the gap for small model systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18(1):4. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.