Abstract

Chronic cardiac allograft rejection is the major barrier to long term graft survival. There is currently no effective treatment for chronic rejection except re-transplantation. Though neointimal development, fibrosis, and progressive deterioration of graft function are hallmarks of chronic rejection, the immunologic mechanisms driving this process are poorly understood. These experiments tested a functional role for IL-6 in chronic rejection by utilizing serial echocardiography to assess the progression of chronic rejection in vascularized mouse cardiac allografts. Cardiac allografts in mice transiently depleted of CD4+ cells that develop chronic rejection were compared with those receiving anti-CD40L therapy that do not develop chronic rejection. Echocardiography revealed the development of hypertrophy in grafts undergoing chronic rejection. Histologic analysis confirmed hypertrophy that coincided with graft fibrosis and elevated intragraft expression of IL-6. To elucidate the role of IL-6 in chronic rejection, cardiac allograft recipients depleted of CD4+ cells were treated with neutralizing anti-IL-6 mAb. IL-6 neutralization ameliorated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, graft fibrosis, and prevented deterioration of graft contractility associated with chronic rejection. These observations reveal a new paradigm in which IL-6 drives development of pathologic hypertrophy and fibrosis in chronic cardiac allograft rejection and suggest that IL-6 could be a therapeutic target to prevent this disease.

Keywords: Chronic Rejection, Hypertrophy, Fibrosis, IL-6

Introduction

Cardiac transplantation remains the preferred treatment for end-stage cardiac diseases refractory to medical therapy (1, 2). While advances in immunosuppressive drugs have greatly decreased the incidence of acute graft rejection, chronic rejection (CR) remains a barrier to long-term graft survival (3). CR in cardiac allografts manifests as interstitial fibrosis, vascular occlusion, and progressive deterioration of graft function (4). Although multiple factors are associated with the onset and progression of CR, the etiology of this disease is poorly understood and there is currently no effective therapy (2).

Immune responses against the graft that ultimately result in CR can be studied in the mouse vascularized heterotopic cardiac transplant model (5–7). In this model, cardiac allograft function has historically been assessed by palpation of the abdominal graft, and it is widely accepted that progressive weakening of palpable heart contractions correlates with both progressive impairment of allograft function and CR. However, the anatomical, functional, and immunologic changes associated with CR are not well defined in this model.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by multiple cell types in response to immunologic challenge, stress, and infection (8, 9). In addition to its known effects on the differentiation and survival of immune cell lineages, IL-6 promotes inflammation by inducing leukocyte recruitment to many cell types, including cardiac myocytes (10). Furthermore, elevated levels of IL-6 have been associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy (11–15). Although several reports have correlated elevated levels of IL-6 in serum with cardiac dysfunction (16–19) and increased myocardial IL-6 with donor heart dysfunction (20), the effects of IL-6 on the progression of CR following transplantation have not been reported.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of serial non-invasive two-dimensional echocardiography in detecting the progression of CR and its correlation with the biological and immunologic changes associated with chronic graft failure. These echocardiographic, histologic, and molecular insights suggest that IL-6 plays a critical role in the cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with CR and that IL-6 may serve as a novel therapeutic target for preventing CR.

Materials and Methods

Mice

WT female C57BL/6 (H-2b) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC). The animals were kept under micro-isolator conditions. The use of mice for these studies was reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan’s Committee On The Use And Care Of Animals.

Vascularized Cardiac Transplantation

Heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed as described (5). In brief, the aorta and pulmonary artery of the donor heart were anastomosed end-to-side to the recipient’s abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava, respectively. Upon perfusion with the recipient’s blood, the transplanted heart resumes contraction. Graft function is monitored by abdominal palpation.

In Vivo mAb Therapy

Anti-CD4 (hybridoma GK1.5, obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), anti-CD40L (hybridoma MR1, kindly provided by Dr. Randy Noelle, Dartmouth College), and anti-IL-6 (hybridoma MP5-20F3, obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas VA, with permission of DNAX) mAbs were purified and resuspended in PBS by Bio X Cell (West Lebanon, NH). Allograft recipients were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells by i.p. injection of 1 mg of anti-CD4 mAb on days -1, 0, and 7 post transplant (6). For inductive anti-CD40L therapy, allograft recipients were injected i.p. with 1 mg of anti-CD40L on days 0, 1, and 2 post transplant (6). Anti-IL-6 mAb or control rat IgG was administered by i.p. injection of 1 mg on days -1, 1, and 3 and weekly thereafter (21).

2D Echocardiography

Serial non-invasive echocardiography was performed with a 30 MHz ultrasound probe (Vevo 770, VisualSonics Inc., Toronto, Canada). Mice were anesthetized using inhaled isofluorane. Anatomical and functional changes were assessed in the left ventricle (LV) of heterotopic cardiac grafts by obtaining short-axis views (at the mid-papillary level) of the grafts as reported by Scherrer-Crosbie et al. (22). Briefly, echocardiographic images were recorded in real time from both axial and longitudinal axes and saved for subsequent analysis. Measurements of posterior wall thickness (PWT) were performed in diastole and measurements for calculating fractional shortening (FS) were taken in both systole and diastole. This echocardiography technique was validated by measuring PWT of acutely rejecting BALB/c allografts in C57BL/6 recipients, and in syngeneic C57BL/6 controls as described (22). Echocardiography was performed on allografts in recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (which develop CR), allograft recipients given anti-CD40L mAb therapy (which do not develop CR), and syngeneic C57BL/6 graft controls. Serial echocardiography was performed to evaluate PWT, FS and left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF). Measurements were obtained on day 7 and then weekly from day 21 to day 49 post transplant.

Morphometric Analysis of Cardiac Allograft Fibrosis and Hypertrophy

Graft fibrosis was quantified by morphometric analysis of Masson’s trichrome stained sections using iPLab software (Scanalytics Inc., Fairfax, VA). Mean fibrotic area was calculated from 10 to 12 areas per heart section analyzed at 200X magnification. To quantify cardiomyocyte area as a measure of hypertrophy, digital outlines were drawn around at least 80 cardiomyocytes from views of H&E stained grafts at 200X magnification. Areas within outlines were quantified using SCION IMAGE Beta4.0.2 software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD) to measure cardiomyocyte cell size (23). A minimum of 5 individual hearts were analyzed per group for both analysis techniques.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Graft RNA was isolated by homogenizing tissues in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Five μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed using Oligo dT, dNTPs, MMLV-RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), RNAsin (Promega, Madison, WI) in PCR Buffer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The cDNA was purified by a 1:1 extraction with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl (25:24:1) and precipitated in one volume 7.5M NH4OAc and two volumes absolute ethanol. Levels of IL-6, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and collagen αI message were determined by quantitative real time PCR using SYBR master mix (Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) in a Rotor-Gene 3000 thermocycler (Corbett Life Science, San Francisco, CA). Relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH expression using the Rotor-Gene Comparative Concentration utility.

Primer sequences were as follows:

ANP (Nppa) forward 5′ GGAGGTCAACCCACCTCTG 3′

ANP (Nppa) reverse 5′ GCTCCAATCCTGTCAATCCTAC 3′

collagen αI (Col1a1) forward 5′ TCCCTACTCAGCCGTCTGTGCC 3′

collagen αI (Col1a1) reverse 5′ AGCCCTCGCTTCCGTACTCG 3′

GAPDH (Gapdh) forward 5′ CTGGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTG 3′

GAPDH (Gapdh) reverse 5′ CAGTCTTCTGAGTGGCAGTG 3′

IL-6 (Il6) forward 5′ CGTGGAAATGAGAAAAGAGTTGT 3′

IL-6 (Il6) reverse 5′ TCCAGTTTGGTAGCATCCATC 3′

Flow Cytometry

Splenocytes were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3, PE-conjugated anti-CD4, and CY-conjugated anti-CD8 obtained from PharMingen (San Jose, CA). Cell analyses were performed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan (San Jose, CA) using forward vs. side scatter to gate on cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. p values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Experimental system

In the mouse vascularized cardiac allograft model, allografts in recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb do not undergo CR (6). In contrast, allografts in recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells develop CR as CD4+ cells begin to repopulate the periphery between 3 and 4 weeks following initial depletion (6, 24, 25). Hence, we compared events that occurred in these two settings to identify critical elements associated with the progression of CR. Specifically, we assessed anatomical and functional echocardiographic parameters, cardiac hypertrophy, intragraft IL-6 expression, and graft fibrosis in CR.

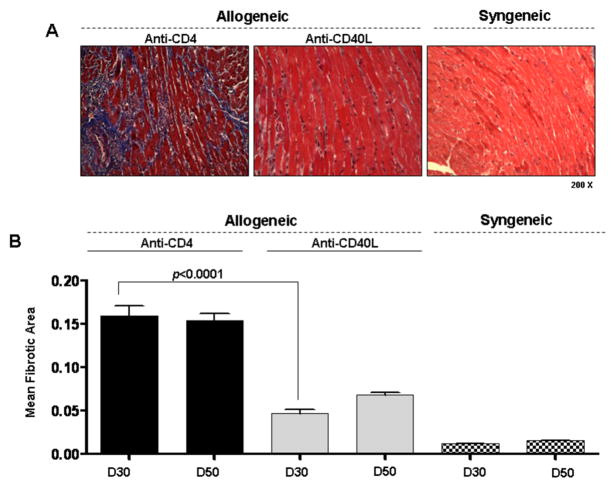

Fibrosis in allografts undergoing CR

Fibrosis was most prominent among grafts transiently depleted of CD4+ cells that develop CR as assessed by morphometric trichrome analysis (p<0.0001, Figure 1). Similarly, intragraft collagen αI transcript levels were greatest in CR grafts (data not shown). It should be noted that no significant changes were found in either graft fibrosis (Figure 1B) or collagen αI transcript levels (data not shown) between day 30 and day 50 post transplant in grafts undergoing CR, indicating that a full fibrotic response is present by day 30 in this model.

Figure 1. Fibrosis is increased in cardiac allografts undergoing CR.

(A) Representative Masson’s trichrome stains, in which fibrotic tissue stains blue, of heterotopic cardiac grafts at day 30 post transplant (200x magnification). Cardiac allografts from recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (Anti-CD4) or allograft recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb therapy (Anti-CD40L) are shown along with syngeneic control grafts. (B) Morphometric analysis of trichrome staining at day 30 and 50 post transplant in groups from (A). Bars represent the combined mean + S.E.M. of fibrotic (blue) area of 10–12 frames of view per heart taken from no fewer than 6 different cardiac grafts per group.

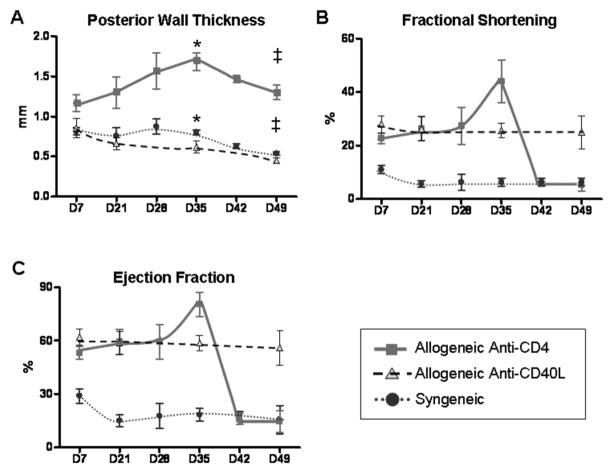

Echocardiographic assessment of the progression of CR

Serial echocardiography was performed to determine the anatomical and functional changes associated with the progression of CR. This echocardiographic technique was validated by assessment of unmodified syngeneic and allogeneic grafts as previously described (22). Increases in PWT in acutely rejecting allogeneic grafts as well as diminished thickening in control syngeneic grafts matched previously reported results (22) in both trend and magnitude (data not shown). It should be noted that LV intra-cavity thrombosis was observed in all groups. Following the first week post transplant, intra-cardiac thrombus retraction (toward the apex) occurred, allowing lucid visualization of all LV parameters as endocardial contour definition was clearly demarcated.

Echocardiography was used to monitor allografts in recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells, which undergo CR. Although it is true that heterotopic cardiac grafts contract against a reduced load, identical surgical procedure between groups assures similar loading conditions required for comparative assessments of graft hypertrophy and fibrosis. Allografts undergoing CR were compared to allografts in recipients receiving anti-CD40L therapy (that do not undergo CR) and also to syngeneic grafts (Figure 2). PWT was greatest in grafts undergoing CR from day 7 through day 49 post transplant, peaking at approximately day 35 (Figure 2A). The increase in PWT among CR grafts correlated with an increased FS and LVEF (Figure 2). These parameters remained stable in allograft recipients treated with anti-CD40L mAb, as well as in syngeneic grafts. Increases in PWT and cardiac functional parameters (FS and LVEF) by day 35 post transplant in the anti-CD4 treated group suggested an association of cardiac hypertrophy with CR. Following the peaks in PWT, FS and LVEF at day 35 post transplant, deterioration of graft contractility occurred by day 42 (Figure 2B and C). Together, the changes in graft contractile parameters between days 30 and 50 post transplant (Figure 2B and C) and the consistency of graft fibrotic area over the same time period (Figure 1B) indicated that day 30 represents a critical time point in this CR model.

Figure 2. Echocardiographic analysis suggests hypertrophy in grafts undergoing CR.

Serial echocardiography was used to monitor anatomical and functional parameters of cardiac allografts in recipients that were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (Anti-CD4, squares), in allograft recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb therapy (Anti-CD40L, triangles), or syngeneic graft recipients (circles). Echocardiographic parameters included posterior wall thickness (PWT) (A), fractional shortening (FS) (B), and left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) (C). Three transplants per experimental group were followed throughout the duration of the experiment. Individual points represent mean and bars represent ± S.E.M. at the given time points. * Day 35: Anti-CD4 vs. Anti-CD40L, p=0.004 and Anti-CD4 vs. Syngeneic, p=0.017. ‡ Day 49: Anti-CD4 vs. Anti-CD40L, p=0.0126 and Anti-CD4 vs. Syngeneic, p=0.0146.

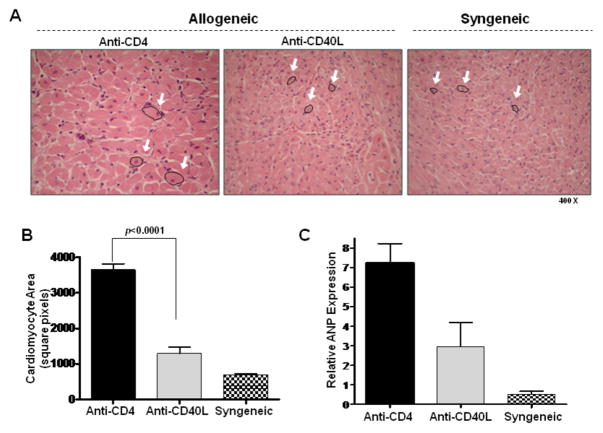

Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and elevated IL-6 expression in grafts undergoing CR

Echocardiography revealed an anatomical increase in PWT as well as functional increases in FS and LVEF, factors consistent with a hyperdynamic state, as is seen with LV hypertrophy. Cardiac hypertrophy has been defined as an increase in heart mass reflective of increased cell size rather than cell number (26). To verify the presence of hypertrophy, cardiomyocyte areas were evaluated histologically at day 30 post transplant (Figures 3A and 3B). Histologic analysis revealed that cardiomyocyte size was greatest in CR grafts when compared to allografts in recipients receiving anti-CD40L or syngeneic grafts (p<0.0001). Further, because increased levels of ANP expression have been correlated with cardiac hypertrophy (12, 27), intragraft expression of ANP was determined with quantitative real time PCR. Intragraft ANP expression correlated with cardiomyocyte size in CR grafts, allograft recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb, and syngeneic grafts (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Histologic confirmation of cardiac hypertrophy in CR grafts.

(A) H&E stains of day 30 post transplant cardiac allografts taken from recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (Anti-CD4) or recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb therapy (Anti-CD40L) as well as syngeneic control graft recipients. Arrows highlight representative cardiac myocytes. (B) Cardiomyocyte areas were quantified using morphometric analysis. Bars represent mean + S.E.M. of area measurements taken from at least 80 cardiomyocytes per heart from 5 different hearts per group. (C) Intragraft message levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a marker of cardiac hypertrophy, were measured with quantitative real time PCR in cardiac grafts from recipients in (B) at day 30 post transplant. Bars represent mean + S.E.M. of 3–5 grafts per group.

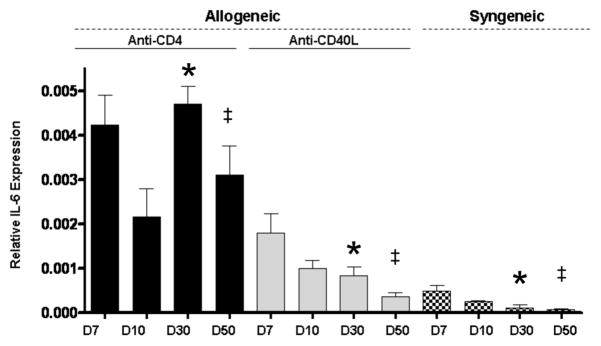

Since cardiac hypertrophy coincided with increased fibrosis in CR allografts, we hypothesized that there might be a common immunologic mediator of both processes. IL-6 has been linked to cardiac hypertrophy (28) and collagen production (29). Therefore, IL-6 expression was assessed in allografts undergoing CR, as well as in control grafts. IL-6 message levels were highest in CR grafts at all time points (Figure 4). While intragraft IL-6 message levels progressively decreased after day 7 among allografts treated with anti-CD40L and syngeneic grafts, CR grafts exhibited a significant resurgence of IL-6 expression (p=0.0141) on day 30 post transplant (Figure 4). Thus, a correlation was observed between CD4+ cell return (24, 25), intragraft IL-6 expression, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and graft fibrosis. This prompted our investigation into the role of IL-6 in the initiation of hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with cardiac CR.

Figure 4. Increased intragraft IL-6 expression in grafts undergoing CR.

IL-6 message levels in cardiac allografts taken from recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (Anti-CD4), recipients receiving anti-CD40L mAb therapy (Anti-CD40L), or from syngeneic graft recipients were determined at given time points using quantitative real time PCR. Bars represent mean + S.E.M. of 3–6 grafts per group which were harvested at the given time points. * Day 30 Anti-CD4 vs. Anti-CD40L, p=0.0141 and Anti-CD4 vs. Syngeneic, p=0.0083. ‡ Day 49: Anti-CD4 vs. Anti-CD40L, p=0.0150 and Anti-CD4 vs. Syngeneic, p=0.0102.

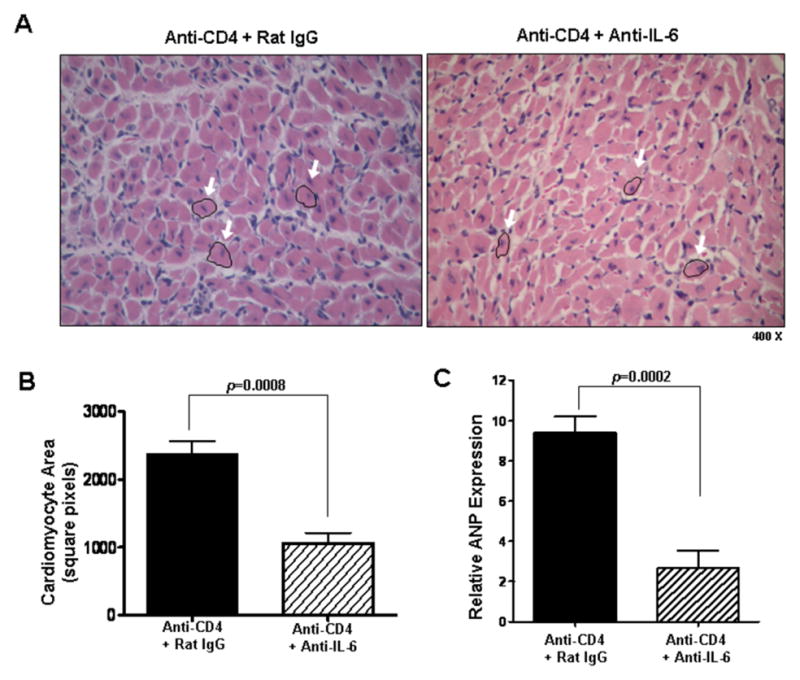

Neutralizing IL-6 reduces cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and normalizes echocardiographic parameters

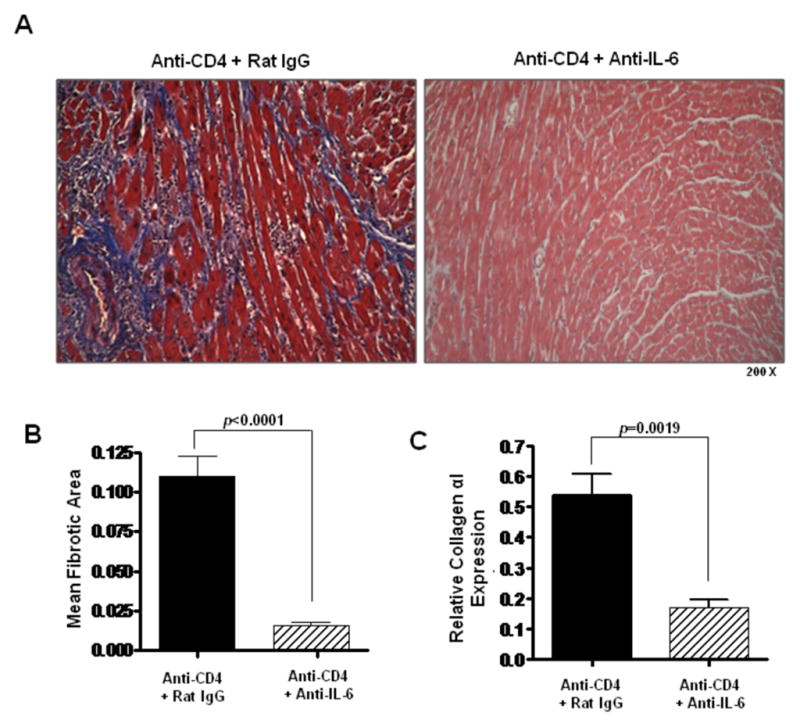

To better understand the role of IL-6 in promoting hypertrophy and fibrosis in CR, allograft recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells were treated with neutralizing anti-IL-6 mAb or control rat IgG. In recipients treated with anti-IL-6 mAb, cardiomyocyte area (p<0.0008) and intragraft ANP transcript levels (p=0.0002) were significantly reduced compared to recipients treated with control rat IgG (Figure 5). Decreases in these parameters implicate IL-6 as an inducer of cardiac hypertrophy and demonstrate that its neutralization can ameliorate cardiac hypertrophy associated with CR. Furthermore, IL-6 neutralization reduced graft fibrotic tissue area (p<0.0001, Figure 6A, B) and intragraft expression of collagen αI (p=0.0019, Figure 6C) compared to control grafts. These observations indicate that IL-6 promotes graft fibrosis associated with cardiac CR and that IL-6 neutralization can significantly decrease interstitial fibrosis associated with the disease.

Figure 5. Neutralizing IL-6 reduces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

(A) Representative views of H&E stained sections of day 30 post transplant cardiac allografts taken from recipients that were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells which also received either control rat IgG (Anti-CD4 + Rat IgG) or neutralizing IL-6 mAb (Anti-CD4 + Anti-IL-6). Arrows highlight representative cardiomyocytes. (B) Cardiomyocyte area quantitation of groups described in (A). Bars represent mean + S.E.M of area measurements taken from >80 cardiomyocytes per heart in each of 5 different grafts per group. (C) Intragraft atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) message levels in grafts described in (A) were determined using quantitative real time PCR. Bars represent mean + S.E.M. of tissue harvested from at least 5 different transplants per group.

Figure 6. Neutralizing IL-6 reduces cardiac fibrosis.

(A) Representative views of Masson’s trichrome staining of day 30 post transplant cardiac allografts taken from recipients transiently depleted of CD4+ cells which also received either control rat IgG antibodies (Anti-CD4 + Rat IgG) or neutralizing IL-6 mAb (Anti-CD4 + Anti-IL-6). (B) Morphometric analysis of graft fibrosis in groups described in (A). Bars represent the combined mean + S.E.M. of fibrotic (blue) area from at least 10 different frames of view from each of at least 6 different cardiac grafts. (C) Intragraft collagen αI message levels in cardiac allografts taken from recipients described in (B) were determined using quantitative real time PCR. Bars represent mean + S.E.M. of tissue harvested from at least 6 different transplants per group.

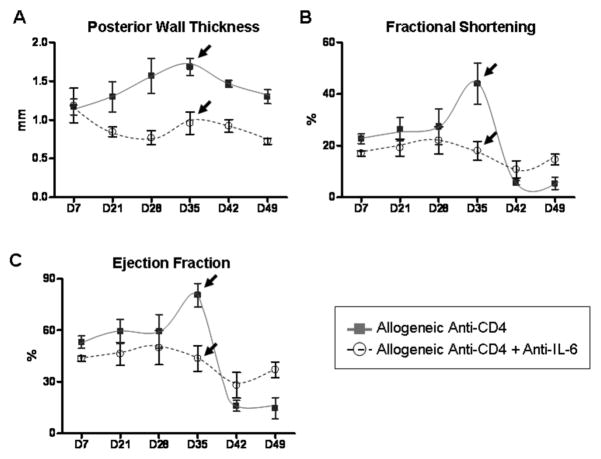

Since neutralizing IL-6 ameliorated both hypertrophy and fibrosis as determined by histologic and gene expression analyses, we assessed the effects of anti-IL-6 on anatomical and functional parameters of chronically rejecting hearts. Echocardiography revealed that neutralizing IL-6 prevented the increase in PWT and normalized FS and LVEF parameters in grafts which would otherwise undergo CR (Figure 7). Thus, hypertrophy, fibrosis and subsequent deterioration of graft contractility were ameliorated in grafts whose recipients were treated with anti-IL-6 mAb. These are the first data to demonstrate that IL-6 may provide a therapeutic target for preventing CR.

Figure 7. Neutralizing IL-6 ameliorates contractile parameter aberrations associated with CR.

Serial echocardiography was used to monitor anatomical and functional parameters in cardiac allograft recipients that were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells which also received neutralizing IL-6 mAb (Anti-CD4 + Anti-IL-6, circles). Results are plotted against 3 recipients that were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells (Anti-CD4, squares) from Figure 2. Echocardiographic parameters included posterior wall thickness (PWT) (A), fractional shortening (FS) (B), and left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) (C). For the anti-IL-6 mAb treated group, 5 transplants were followed throughout the duration of the experiment. Individual points represent mean and bars represent ± S.E.M. of grafts analyzed at the given time point.

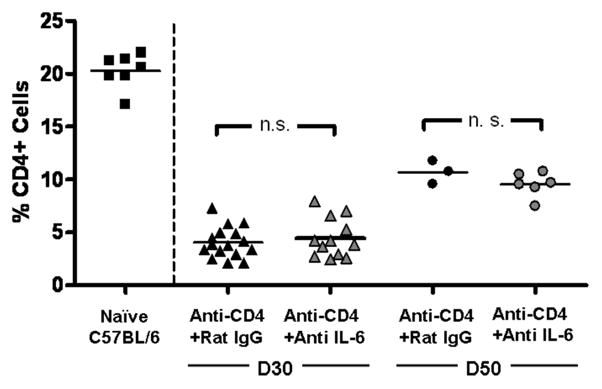

IL-6 neutralization does not inhibit CD4+ cell repopulation of the periphery

In this model of CR, CD4+ cells begin to repopulate the periphery between 3 and 4 weeks post-transplant (24, 25). To ascertain the effect of IL-6 neutralization on CD4+ cell repopulation, flow cytometry was performed on splenocytes taken from animals receiving anti-IL-6 mAb or control rat IgG. Both treatment groups had similar percentages of CD4+ cells on day 30 or day 50 post transplant (Figure 8), indicating that neutralizing IL-6 does not prevent CD4+ cell repopulation of the periphery.

Figure 8. Neutralizing IL-6 does not prevent CD4+ cell repopulation in cardiac allograft recipients.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed on splenocytes harvested from naive mice or allograft recipients that were transiently depleted of CD4+ cells which also received either control rat IgG antibodies (Anti-CD4 + Rat IgG) or neutralizing IL-6 mAb (Anti-CD4 + Anti-IL-6). Splenocytes were harvested from cardiac allograft recipients on day 30 (triangles) or day 50 (circles) post transplant. Lines represent group mean, n.s. = not significant.

Discussion

CR is characterized by the formation of patchy interstitial fibrosis and occlusion of vasculature structures accompanied by progressive graft dysfunction (3, 4). Currently, there is no therapeutic which specifically targets CR. Although several factors have been implicated with CR, the etiology and changes associated with the progression of the disease are not fully understood. To better define these changes we monitored the progress of CR using echocardiography.

Echocardiography has been demonstrated to be effective for monitoring acute rejection (22) and long term acceptance (30) of heterotopic mouse cardiac grafts. We used echocardiography to successfully monitor the progression of CR in mice. Further, we have identified critical elements of the disease process, notably that the fibrosis of CR is associated with cardiac hypertrophy and that both processes are driven by IL-6.

Grafts undergoing CR had increased PWT, a reproducible measure of cardiac rejection in mice (22). Such increases in PWT could be caused by immunologic and inflammatory processes associated with CR such as edema, graft-infiltrating cells, cell proliferation and collagen deposition (3, 4). However, echocardiographic functional analyses (FS and LVEF) revealed increased graft contraction coincident with increased PWT by day 35 post transplant in CR grafts (Figure 2). Together, these parameters suggested the presence of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (31) in grafts undergoing CR. Manifestations of hypertrophy were followed by significant deterioration of graft contractility by day 42 post transplant. Such declines in cardiac contractility mirror events observed in human heart failure (32). These observations implied that day 30 post transplant represents a critical time point of CR in this mouse model as it exhibits near terminal amounts of interstitial fibrosis (Figure 1) and increases in functional parameters indicative of hypertrophy (Figure 2).

Hypertrophy in CR grafts was confirmed by increased cardiomyocyte area (Figure 3B) and elevated levels of ANP (Figure 3C), a marker whose up-regulation has been linked to cardiac hypertrophy in multiple models (12, 27). Although cardiomyocyte hypertrophy has been reported in other models of cardiac failure (33–35), our data suggest a concomitance of cardiac hypertrophy with CR. Since it is widely accepted that immunologic factors contribute to CR, we considered that an immunologic factor might be promoting hypertrophy (28). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that increased IL-6 signaling is sufficient to induce cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular wall thickening in vivo (36). It should be noted that while sufficient to induce cardiac hypertrophy, IL-6 is dispensable for adaptive physiologic hypertrophy responses to exercise training (37, 38). Thus, while unnecessary for physiologic hypertrophy, IL-6 has been implicated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy in humans (11, 39) and animals (12–15).

Elevated intragraft IL-6 transcript levels at day 30 post transplant coincided with graft hypertrophy and fibrosis in grafts undergoing CR (Figures 1, 3, and 4). To our knowledge this is the first report correlating hypertrophy and elevated intragraft IL-6 expression with CR. It is of note that significant elevation of IL-6 expression in allografts undergoing CR at days 30 and 50 post transplant occurs after a suggested (but not significant vs. Anti-CD40L) increase at day 7 (Figure 4). The importance of this early peak in the bimodal expression of IL-6 is unclear, though it is not likely due to ischemic/reperfusion injury in that syngeneic control grafts did not exhibit a comparable early elevation of IL-6. One possibility is that the early elevation of IL-6 expression in allograft recipients treated with anti-CD4 mAb may be associated with the process of depleting CD4+ cells.

IL-6 has previously been suggested as a therapeutic target for hypertrophy (40), therefore, we neutralized IL-6 to assess its role in the hypertrophy associated with CR. Neutralizing IL-6 reduced cardiomyocyte area (Figure 5) and prevented the increases in PWT, FS and LVEF indicative of cardiac hypertrophy that were observed in CR grafts (Figure 7). These results implicate IL-6 as an inducer of hypertrophy in CR. Further, targeting IL-6 may ameliorate hypertrophy while stabilizing functional parameters in cardiac allografts undergoing CR.

It has been demonstrated in vitro that hypertrophic stimuli induce cardiac myocyte production of factors known to promote fibrosis, including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (41) and TGFβ (42). We have previously reported a strong correlation between intragraft expression of TGFβ and CTGF with CR (6). This raises the interesting possibility that IL-6 can induce similar pro-fibrotic gene expression in vivo. It should be noted that in addition to potential enhancement of TGFβ production through the induction of hypertrophy, IL-6 may also directly augment TGFβ signaling by regulating turnover and compartmentalization of its receptor (43). Furthermore, it has recently been reported that the C-terminal domain of CTGF can induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (44). Together these data suggest that IL-6 may induce other factors able to promote both hypertrophy and fibrosis in CR.

Neutralizing IL-6 not only decreased cardiomyocyte hypertrophy but also lessened fibrosis of the graft. This finding is consistent with previous in vitro studies in which IL-6 increased collagen transcript levels in co-cultures of cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes (29) and treatment with IL-6 neutralizing mAb decreased cardiac fibroblast proliferation (45). Further, IL-6 may induce factors that facilitate fibroblast survival (46). Thus, decreased survival, proliferation, and collagen αI transcript levels in cardiac fibroblasts may explain the anti-fibrotic effects of neutralizing IL-6 in our study.

Beyond its roles in hypertrophy and fibrosis, IL-6 is also a potent modulator of immune responses in multiple cell types of both the innate and adaptive systems (reviewed in (8, 9, 47)). Hence, it is possible that IL-6 neutralization ameliorates CR in this model through immunomodulatory effects. IL-6 neutralization could prolong graft survival by impairing the transition of graft-reactive immunity from innate responses to adaptive responses, perhaps through disruption of the neutrophil to monocyte recruitment progression (47). Additionally, lymphocyte homing to the graft may be impaired, as IL-6 can induce the expression of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1, CCL2) in fibroblasts (48) as well as promote T cell migration on fibronectin substrate (49). In addition to promoting recruitment, IL-6 can rescue T cells from apoptosis (50). It is therefore conceivable that neutralizing IL-6 could further enhance graft survival through both failure to recruit and increased apoptosis of graft-reactive T cells.

It is now known that the presence or absence of IL-6 may determine T cell responses to TGFβ, as TGFβ and IL-6 result in Th17 effector cells while TGFβ without IL-6 can generate FoxP3+ regulatory cells (51). The possibility that this axis of effector/regulatory T cell responses may be a key factor in CR is supported by historic observations of IL-6, TGFβ, and T cell receptor β constant region expression in rejecting human cardiac allografts (52). Furthermore, a role for IL-17 in the pathology of CR seems more likely in light of observations that IL-17 alone stimulates increased collagen production in primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts (53). This is consistent with a report that Th17 responses to collagen type V correlate with the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung transplant patients (54) and that IL-17 has recently been associated with the development of transplant associated vasculopathy (55).

We have demonstrated that neutralizing IL-6 does not inhibit CD4+ cell repopulation in this system (Figure 8). Therefore, we asked whether neutralizing IL-6 had other effects on CD4+ or CD8+ cell function. To this end, ELISPOT assays (21) were performed on splenocytes harvested on day 30 post transplant from allograft recipients that were initially depleted of CD4+ cells and treated with either anti-IL-6 mAb or rat IgG. ELISPOT assays for donor-reactive IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 producing cells were performed on whole splenocytes, splenocytes depleted of CD4+ cells, and splenocytes depleted of CD8+ cells. Similarly low frequencies (<50 spots/million cells) of donor-reactive cytokine producing cells were present in the spleens of rat IgG or anti-IL-6 treated recipients, indicating that IL-6 neutralization did not alter the immune response at the level of Th subset function. Hence, both CD4+ and CD8+ Th1, Th2, and Th17 remained hyporesponsive in the spleens of allograft recipients following transient depletion of CD4+ cells.

Finally, as IL-6 can augment antigen-specific antibody responses in mice (56), we assessed serum levels of donor-reactive IgM or IgG. No significant difference was observed between anti-IL-6 treated recipients or controls (data not shown). It should be noted that these observations do not rule out other immunomodulatory effects of IL-6 neutralization in this setting. Indeed, anti-IL-6 mAb might alter lymphocyte trafficking to the graft (10, 48, 49), lymphocyte survival (50), activation and differentiation (51), as well as the immunologic events initiating fibrosis.

In conclusion, we report the use of echocardiography for monitoring the in vivo changes occurring in CR, which helped identify a previously unrecognized immunologic axis in the development of chronic cardiac allograft rejection. These echocardiographic, histologic, and molecular findings suggest a critical role of IL-6 in the cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with CR. Together, these observations indicate that IL-6 neutralization may represent the first therapeutic approach to ameliorate hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with CR while stabilizing anatomical and functional parameters of the graft. The potential clinical relevance of our study is highlighted by a recent report in which echocardiography defined cardiac allograft hypertrophy as a prognostic marker for the development of allograft vasculopathy and increased patient mortality (57). As pointed out in an accompanying Editorial (58), cardiac allograft hypertrophy and its association with graft vasculopathy may provide a surrogate marker for patient survival in clinical trials of cardiac transplantation. Further, identifying the underlying mechanisms of the disease process should allow for the design of specific therapies aimed at halting the progression of cardiac allograft hypertrophy and CR.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01 HL070613 (DKB) and R01 AI061469 (DKB), T32 HL076123 (JAD), and an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AJB). DJP is supported by the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute, The Ruth Professorship, and NIH grants R01 HL055397, R01 HL086676, P01 HL098407 and T32 HL007853.

The authors would like to thank Kimber Converso and Dr. Mark Russell for their assistance in echocardiography data acquisition. We would also like to thank members of the Bishop laboratory for their enthusiasm and comments throughout the course of these investigations.

References

- 1.Al-khaldi A, Robbins RC. New directions in cardiac transplantation. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:455–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.082704.130518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dec W. Cardiac allograft rejection. c2001. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. c2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P, Pober JS. Chronic rejection. Immunity. 2001;14(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orosz CG, Pelletier RP. Chronic remodeling pathology in grafts. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9(5):676–680. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16(4):343–350. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csencsits K, Wood SC, Lu G, Faust SM, Brigstock D, Eichwald EJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta-induced connective tissue growth factor and chronic allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5 Pt 1):959–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa T, Visovatti SH, Hyman MC, Hayasaki T, Pinsky DJ. Heterotopic vascularized murine cardiac transplantation to study graft arteriopathy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(3):471–480. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naugler WE, Karin M. The wolf in sheep’s clothing: the role of interleukin-6 in immunity, inflammation and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(3):109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youker K, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Miller D, Michael LH, Rossen RD, et al. Neutrophil adherence to isolated adult cardiac myocytes. Induction by cardiac lymph collected during ischemia and reperfusion. J Clin Invest. 1992;89(2):602–609. doi: 10.1172/JCI115626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erten Y, Tulmac M, Derici U, Pasaoglu H, Altok Reis K, Bali M, et al. An association between inflammatory state and left ventricular hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2005;27(5):581–589. doi: 10.1080/08860220500200072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredj S, Bescond J, Louault C, Potreau D. Interactions between cardiac cells enhance cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and increase fibroblast proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202(3):891–899. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurdi M, Randon J, Cerutti C, Bricca G. Increased expression of IL-6 and LIF in the hypertrophied left ventricle of TGR(mRen2)27 and SHR rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;269(1–2):95–101. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sano M, Fukuda K, Kodama H, Pan J, Saito M, Matsuzaki J, et al. Interleukin-6 family of cytokines mediate angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rodent cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(38):29717–29723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briest W, Rassler B, Deten A, Leicht M, Morwinski R, Neichel D, et al. Norepinephrine-induced interleukin-6 increase in rat hearts: differential signal transduction in myocytes and non-myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446(4):437–446. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota H, Izumi M, Hamaguchi T, Sugiyama S, Murakami E, Kunisada K, et al. Circulating interleukin-6 family cytokines and their receptors in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2004;19(5):237–241. doi: 10.1007/s00380-004-0770-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(5):1201–1206. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsutamoto T, Hisanaga T, Wada A, Maeda K, Ohnishi M, Fukai D, et al. Interleukin-6 spillover in the peripheral circulation increases with the severity of heart failure, and the high plasma level of interleukin-6 is an important prognostic predictor in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(2):391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107(11):1486–1491. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birks EJ, Burton PB, Owen V, Mullen AJ, Hunt D, Banner NR, et al. Elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in myocardium and serum of malfunctioning donor hearts. Circulation. 2000;102(19 Suppl 3):III352–358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burrell BE, Csencsits K, Lu G, Grabauskiene S, Bishop DK. CD8+ Th17 mediate costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection in T-bet-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):3906–3914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherrer-Crosbie M, Glysing-Jensen T, Fry SJ, Vancon AC, Gadiraju S, Picard MH, et al. Echocardiography improves detection of rejection after heterotopic mouse cardiac transplantation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15(10 Pt 2):1315–1320. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.124644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nozato T, Ito H, Tamamori M, Adachi S, Abe S, Marumo F, et al. G1 cyclins are involved in the mechanism of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II. Jpn Circ J. 2000;64(8):595–601. doi: 10.1253/jcj.64.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop DK, Li W, Chan SY, Ensley RD, Shelby J, Eichwald EJ. Helper T lymphocyte unresponsiveness to cardiac allografts following transient depletion of CD4-positive cells. Implications for cellular and humoral responses. Transplantation. 1994;58(5):576–584. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199409150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piccotti JR, Li K, Chan SY, Eichwald EJ, Bishop DK. Cytokine regulation of chronic cardiac allograft rejection: evidence against a role for Th1 in the disease process. Transplantation. 1999;67(12):1548–1555. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marian AJ. Genetic determinants of cardiac hypertrophy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23(3):199–205. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282fc27d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caron KM, James LR, Kim HS, Knowles J, Uhlir R, Mao L, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy and sudden death in mice with a genetically clamped renin transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(9):3106–3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307333101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terrell AM, Crisostomo PR, Wairiuko GM, Wang M, Morrell ED, Meldrum DR. Jak/STAT/SOCS signaling circuits and associated cytokine-mediated inflammation and hypertrophy in the heart. Shock. 2006;26(3):226–234. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000226341.32786.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar S, Vellaichamy E, Young D, Sen S. Influence of cytokines and growth factors in ANG II-mediated collagen upregulation by fibroblasts in rats: role of myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(1):H107–117. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou YQ, Bishay R, Feintuch A, Tao K, Golding F, Zhu W, et al. Morphological and functional evaluation of murine heterotopic cardiac grafts using ultrasound biomicroscopy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33(6):870–879. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasad K, Atherton J, Smith GC, McKenna WJ, Frenneaux MP, Nihoyannopoulos P. Echocardiographic pitfalls in the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 1999;82(Suppl 3):III8–III15. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2008.iii8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob R, Gulch RW. The functional significance of ventricular geometry for the transition from hypertrophy to cardiac failure. Does a critical degree of structural dilatation exist? Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93(6):423–429. doi: 10.1007/s003950050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loyer X, Gomez AM, Milliez P, Fernandez-Velasco M, Vangheluwe P, Vinet L, et al. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase delays transition toward heart failure in response to pressure overload by preserving calcium cycling. Circulation. 2008;117(25):3187–3198. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mancuso P, Rahman A, Hershey SD, Dandu L, Nibbelink KA, Simpson RU. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin-D3 Treatment Reduces Cardiac Hypertrophy and Left Ventricular Diameter in Spontaneously Hypertensive Heart Failure-prone (cp/+) Rats Independent of Changes in Serum Leptin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51(6):559–564. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181761906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moens AL, Takimoto E, Tocchetti CG, Chakir K, Bedja D, Cormaci G, et al. Reversal of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis from pressure overload by tetrahydrobiopterin: efficacy of recoupling nitric oxide synthase as a therapeutic strategy. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2626–2636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirota H, Yoshida K, Kishimoto T, Taga T. Continuous activation of gp130, a signal-transducing receptor component for interleukin 6-related cytokines, causes myocardial hypertrophy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(11):4862–4866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminski KA, Oledzka E, Bialobrzewska K, Kozuch M, Musial WJ, Winnicka MM. The effects of moderate physical exercise on cardiac hypertrophy in interleukin 6 deficient mice. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iemitsu M, Maeda S, Miyauchi T, Matsuda M, Tanaka H. Gene expression profiling of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;185(4):259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2005.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaneko K, Kanda T, Yokoyama T, Nakazato Y, Iwasaki T, Kobayashi I, et al. Expression of interleukin-6 in the ventricles and coronary arteries of patients with myocardial infarction. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1997;97(1):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coles B, Fielding CA, Rose-John S, Scheller J, Jones SA, O’Donnell VB. Classic interleukin-6 receptor signaling and interleukin-6 trans-signaling differentially control angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, cardiac signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 activation, and vascular hypertrophy in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(1):315–325. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsui Y, Sadoshima J. Rapid upregulation of CTGF in cardiac myocytes by hypertrophic stimuli: implication for cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37(2):477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi N, Calderone A, Izzo NJ, Jr, Maki TM, Marsh JD, Colucci WS. Hypertrophic stimuli induce transforming growth factor-beta 1 expression in rat ventricular myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(4):1470–1476. doi: 10.1172/JCI117485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang XL, Topley N, Ito T, Phillips A. Interleukin-6 regulation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta receptor compartmentalization and turnover enhances TGF-beta1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):12239–12245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayata N, Fujio Y, Yamamoto Y, Iwakura T, Obana M, Takai M, et al. Connective tissue growth factor induces cardiac hypertrophy through Akt signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370(2):274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fredj S, Bescond J, Louault C, Delwail A, Lecron JC, Potreau D. Role of interleukin-6 in cardiomyocyte/cardiac fibroblast interactions during myocyte hypertrophy and fibroblast proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204(2):428–436. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Das AM, Seideman J, Griswold D, Afuh CN, Kobayashi T, et al. The CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) mediates fibroblast survival through IL-6. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37(1):121–128. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0253OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones SA. Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):3463–3468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sporri B, Muller KM, Wiesmann U, Bickel M. Soluble IL-6 receptor induces calcium flux and selectively modulates chemokine expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Int Immunol. 1999;11(7):1053–1058. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissenbach M, Clahsen T, Weber C, Spitzer D, Wirth D, Vestweber D, et al. Interleukin-6 is a direct mediator of T cell migration. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(10):2895–2906. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teague TK, Marrack P, Kappler JW, Vella AT. IL-6 rescues resting mouse T cells from apoptosis. J Immunol. 1997;158(12):5791–5796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao XM, Frist WH, Yeoh TK, Miller GG. Expression of cytokine genes in human cardiac allografts: correlation of IL-6 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) with histological rejection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93(3):448–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venkatachalam K, Mummidi S, Cortez DM, Prabhu SD, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Resveratrol inhibits high glucose-induced PI3K/Akt/ERK-dependent interleukin-17 expression in primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(5):H2078–2087. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01363.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burlingham WJ, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, Haynes LD, Xu Q, Bobadilla JL, et al. IL-17-dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3498–3506. doi: 10.1172/JCI28031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan X, Paez-Cortez J, Schmitt-Knosalla I, D’Addio F, Mfarrej B, Donnarumma M, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):3133–3144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takatsuki F, Okano A, Suzuki C, Chieda R, Takahara Y, Hirano T, et al. Human recombinant IL-6/B cell stimulatory factor 2 augments murine antigen-specific antibody responses in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1988;141(9):3072–3077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raichlin E, Villarraga HR, Chandrasekaran K, Clavell AL, Frantz RP, Kushwaha SS, et al. Cardiac allograft remodeling after heart transplantation is associated with increased graft vasculopathy and mortality. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torre-Amione G. Cardiac allograft hypertrophy: a new target for therapy, a surrogate marker for survival? Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]