Abstract

Desmosomes are the major players in epidermis and cardiac muscles and contribute to intercellular binding and maintenance of tissue integrity. Two important constituents of desmosomes are transmembrane cadherins named desmogleins and desmocollins. The critical role of these desmosomal proteins in epithelial integrity has been illustrated by their disruption in mouse models and human diseases. In the present study, we have investigated a large family from Afghanistan in which four individuals are affected with hereditary hypotrichosis and the appearance of recurrent skin vesicle formation. All four affected individuals showed sparse and fragile hair on scalp, as well as absent eyebrows and eyelashes. Vesicles filled with thin, watery fluid were observed on the affected individuals' scalps and on most of the skin covering their bodies. A scalp-skin biopsy of an affected individual showed mild hair-follicle plugging. Candidate-gene-based homozygosity linkage mapping assigned the disease locus to 8.30 cM (8.51 Mbp) on chromosome 18q12.1. A maximum multipoint LOD score of 3.30 (θ = 0.00) was obtained at marker D18S877. Sequence analysis of four desmoglein and three desmocollin genes, contained within the linkage interval, revealed a homozygous nonsense mutation (c.2129T>G [p.Leu710X]) in exon-14 of the desmocollin-3 (DSC3) gene.

Main Text

Desmosomes are cell-adhesion junctions that are required for connecting adjacent cells and maintaining the integrity of organs, such as the skin, that are particularly exposed to mechanical stress. These junctions are composed of assemblies of membrane-spanning cadherins and cytoplasmic plaque constituents. The transmembrane components comprise four types of desmogleins (DSG1, DSG2, DSG3, DSG4) and three types of desmocollins (DSC1, DSC2, DSC3) bridging the extracellular space and are embedded in the cytoplasmic plaques. The plaque components mediate the anchorage of cadherins with intermediate filaments through a protein complex consisting of desmoplakin, plakoglobin, and plakophilins.1

The four desmoglein and three desmocollin genes are localized adjacent to each other on the long arm of chromosome 18 (18q12.1) in humans.2,3 A very similar arrangement of these genes has been found on mouse chromosome 18, with two additional desmoglein genes (dsg1β, dsg1γ). Most of the desmosomal genes have been associated with inherited disorders that affect the skin and its appendages. This includes mutations in plakophilin (PKP1 [MIM 601975]), causing ectodermal dysplasia with sparse hair and skin fragility;4 desmoplakin (DSP [MIM 125647]) and plakoglobin (PG [MIM 173325]), underlying Naxos disease (MIM 601214), characterized by sparse wooly hair and cardiomypathy;5,6 and desmoglein4 (DSG4 [MIM 607892]), causing localized autosomal-recessive hypotrichosis (LAH [MIM 607903]).2 The desmogleins DSG1 and DSG3 also serve as autoantigens in the epidermal blistering diseases pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris, respectively.7,8 In a study involving a large number of patients with bullous disorders, Muller et al.9 have shown that autoantibodies against desmocollins are restricted to cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP).

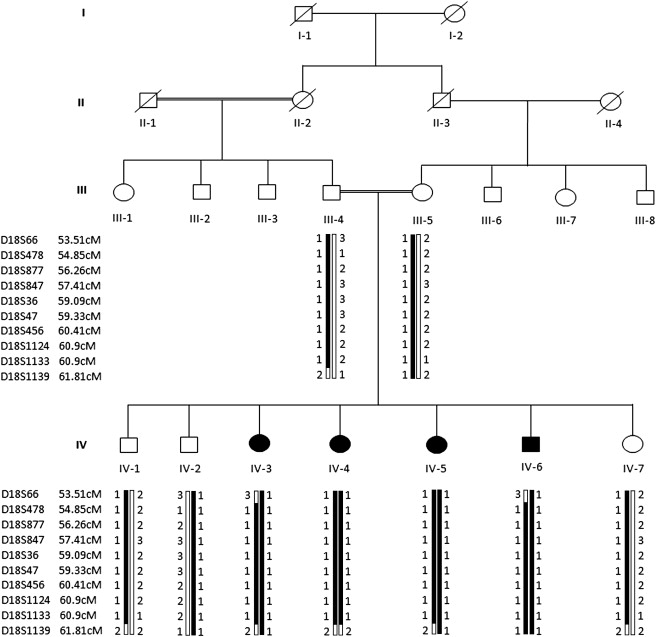

In this study, we have investigated a large family with clinical manifestations of autosomal-recessive hereditary hypotrichosis and a high degree of consanguinity (Figure 1). The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. The family originated from Kandahr city of Afghanistan and has four affected individuals, including one male (IV-6), aged 5 years, and three females (IV-3, IV-4, IV-5), aged from 12 to 18 years. All of the four affected individuals underwent examination at a local government hospital in Pakistan. Affected individuals of the family showed features of hereditary hypotrichosis. At birth, hairs were present on the scalp. After ritual shaving, which is usually performed a week after birth, hairs grew back on the scalp. The hairs were fragile and started falling again after 2–3 months (Figure 2). In time, only sparse hair was left on the scalp. In affected individuals, vesicles (less than 1 cm in diameter) were observed on the scalp and skin of most of the body (Figure 2). Mucosal vesicles were not observed in any of the four affected individuals. From time to time, these vesicles disappeared but then reappeared again. All of the four affected individuals of the family complained of a bursting of the vesicles with a release of fluid and the development scars on the skin site that normally took 3–4 months to heal.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of a Consanguineous Family from Afghanistan Segregating Autosomal-Recessive Hypotrichosis

Double lines are indicative of consanguineous unions. Clear symbols represent unaffected individuals, whereas filled symbols represent affected individuals. The disease interval is flanked by two markers, D18S66 and D18S1139. For genotyped individuals, haplotypes are shown beneath each symbol, revealing that all affected individuals are homozygous for the same haplotype, whereas normal parents and healthy siblings are heterozygous carriers between markers D18S66 and D18S1139. Genetic distances in centiMorgans (cM) are depicted according to the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map (build 36.2).

Figure 2.

Clinical Findings of Affected Individuals with Hereditary Hypotrichosis

(A and B) Affected female individuals IV-3 and IV-5 at 18 and 12 years of age, respectively. Both individuals have sparse and fragile hair on scalp.

(C) Right arm of an affected individual, IV-5, showing vesicles on the skin.

(D) Scalp biopsy of an affected individual, IV-3. Histological examination shows: hf, hair follicle; epi, epidermis; sg, sebaceous glands; swg, sweat glands.

The affected individuals were nearly devoid of normal eyebrows, eyelashes, axillary hair, and body hair. Teeth, nails, palms, soles, sweating, and hearing were normal in all affected individuals. Electrocardiography results showed that affected individuals had no cardiac abnormality. In one affected individual (IV-3), levels of serum immunoglobulin-A (IgA), IgE, and IgD, quantitated by ELISA against control subjects, showed no change. Heterozygous carrier individuals had normal hairs and were clinically indistinguishable from genotypically normal individuals.

A scalp-skin biopsy of an affected individual (IV-3) of the family showed slight follicular plugging, a mild presence of perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory cells, and normal hair follicles (Figure 2). The sebaceous glands appear morphologically normal and connected to the hair follicles.

To identify the gene underlying the hypotrichosis and skin-vesicle phenotype in the family, we followed a classical linkage-analysis approach. Linkage in the family was searched for with the use of highly polymorphic microsatellite markers linked to three genes, including DSG4 (MIM 607892) (markers D18S877, D18S847, D18S36, D18S456, D18S1133), LIPH (MIM 607365) (markers D3S2314, D3S1618, D3S3609, D3S3583, D3S3592, D3S1530), and P2RY5 (MIM 609239) (markers D13S1312, D13S168, D13S164, D13S273, D13S284, D13S1807).10 Conditions used for PCR amplification of the microsatellite markers have been described previously.11

Genotyping data and haplotype analysis showed linkage in the family to the DSG4 gene on chromosome 18q12.1 (Figure 1). The order of the markers, used in genotyping, was based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Build 36.2 sequence-based physical map (International Human Genome Sequence Consortium 2001). Analysis of all the marker genotypes within this region with PEDCHECK and MERLIN did not elucidate any genotyping errors. The results of the two-point12 and multipoint analyses13 are presented in Table 1. An autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance with complete penetrance and a disease-allele frequency of 0.001 were used in the analysis. The highest two-point LOD score at zero recombination fraction (θ = 0.00) of 2.68 was obtained at markers D18S36 and D18S547. Multipoint analysis generated a maximum LOD score of 3.30 with marker D18S877. Haplotypes were constructed with the use of SIMWALK214 for determination of the critical recombination events in the family. The centromeric boundary of the interval corresponds to a recombination event between markers D18S66 (53.51 cM) and D18S478 (54.85 cM), which occurred in affected individual IV-3. A recombination event between markers D18S1133 (60.90 cM) and D18S1139 (61.81 cM) in affected individuals IV-3 and IV-5 defined the telomeric boundary of the disease interval. The linkage interval flanked by markers D18S66 and D18S1139 contains 8.30 cM, which is 8.51 Mbp long according to Rutgers combined linkage-physical map (build 36.2) of the human genome. This region contains 30 genes.

Table 1.

Multipoint and Two-Point LOD Score Results between the DSC3 Gene and Chromosome 18 Markers

| Marker | cMa | Mbb | Multipoint LOD Score | Two-Point LOD Score at Recombination Fraction θ = |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | ||||

| D18S66 | 53.51 | 22.38 | −∞ | −∞ | −1.36 | −0.17 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| D18S478 | 54.85 | 23.40 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.18 |

| D18S877 | 56.26 | 24.97 | 3.30 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.25 |

| D18S847 | 57.41 | 25.95 | 3.29 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.25 |

| DSC3 | N/A | 26.85 | ||||||||

| DSC2 | N/A | 26.91 | ||||||||

| DSC1 | N/A | 26.96 | ||||||||

| DSG1 | N/A | 27.16 | ||||||||

| DSG4 | N/A | 27.23 | ||||||||

| DSG3 | N/A | 27.29 | ||||||||

| DSG2 | N/A | 27.35 | ||||||||

| D18S36 | 59.09 | 27.41 | 3.29 | 2.68 | 2.63 | 2.39 | 2.09 | 1.49 | 0.89 | 0.34 |

| D18S47 | 59.33 | 28.03 | 3.28 | 2.68 | 2.63 | 2.39 | 2.09 | 1.49 | 0.89 | 0.34 |

| D18S456 | 60.41 | 29.41 | 3.26 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.25 |

| D18S1124 | 60.90 | 29.66 | 3.08 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.25 |

| D18S1133 | 60.90 | 30.35 | 2.27 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.14 |

| D18S1139 | 61.81 | 30.89 | −∞ | −∞ | −3.55 | −1.65 | −0.97 | −0.45 | −0.20 | −0.05 |

Average-sex genetic distance in centiMorgans (cM), according to Rutgers combined linkage-physical human genome map.25

The physical position is based according to build 36.2 of the human genome (International Human Genome Sequence Consortium, 2001).

The DSG4 gene (MIM 607892), reported earlier as involved in hereditary hypotrichosis,2,15 was sequenced first with the use of primer sequences (Table S1, available online) in two affected individuals and one normal individual in the family. However, the sequence analysis failed to identify disease-causing variants in the family. Three other desmoglein genes (DSG1 [MIM 125670], DSG2 [MIM 125671], DSG3 [MIM 169651]), as well as three desmocollin genes (DSC1 [MIM 125643], DSC2 [MIM 125645], DSC3 [MIM 600271]), located adjacent to DSG4 on chromosome 18q12.1, were then sequenced. DNA sequencing was performed with the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, together with an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applera, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequence variants were identified via the Bioedit sequence alignment editor, version 6.0.7.

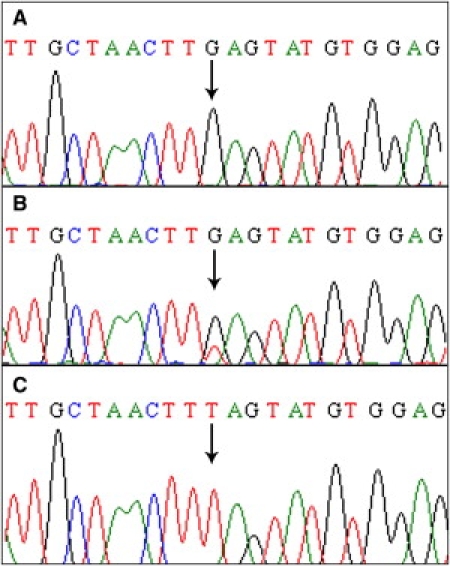

Sequence analysis of the DSC3 gene detected a homozygous nonsense mutation involving a T-to-G transversion at nucleotide position 2129 (c.2129T>G) in exon 14 of the gene (Figure 3). To our knowledge, this mutation has not been previously reported. The mutation resulted in the conversion of leucine to a premature stop codon at amino acid position 710 (p.Leu710X).

Figure 3.

Sequence Analysis of the DSC3 Gene Mutation c.2129T > G in the Family

Partial DNA sequence of the DSC3 gene from (A) a homozygous (affected) individual, showing a transversion (T>G); (B) a heterozygous carrier; and (C) a control individual, showing wild-type sequence. Arrows indicate position of the mutation.

The pathogenic sequence variant presented here was found in the heterozygous state in the obligate carriers and segregated with the disease in the family. To exclude the possibility that the nonsense mutation does not represent a nonpathogenic polymorphism, we screened a panel of 100 unaffected, unrelated, ethnically matched control individuals, and we did not identify the mutation outside of the family.

The pivotal role of the desmosomal proteins in epithelial integrity has been demonstrated by targeted ablation of the corresponding genes in mice, as well as their by disruption in human genetic disorders. Mice deficient in Dsc1, Dsc3, Dsg3, and Dsg4 exhibit skin and hair phenotypes. Mice carrying a targeted deletion of Dsc31 and Dsg316 develop defective hair anchoring in the telogen phase of the growth cycle. These mice also exhibit a skin phenotype that resembles pemphigus vulgaris.1,17 Mice carrying mutations in Dsc1 and Dsg4 exhibit skin and hair phenotypes, but defective hair anchoring is not a feature in these mutants.2,18 In humans, the role of DSG4 in skin has been established by identification of mutations in families with inherited hypotrichosis (MIM 607903).2

In the study presented here, we have reported a mutation, which to our knowledge has not been previously published, in the DSC3 gene in a family originating from a famous city of Kandahr in Afghanistan. Clinical features including hypotrichosis and skin vesicles were observed in all of the affected individuals of the family. These vesicles burst from time to time, releasing thin, watery fluid. Such a condition was not reported in any of the patients carrying mutations in other cadherin genes. The vesicles observed in our patients were not similar to skin blisters reported earlier in Dsc3 and Dsg3 null mice.

The 52 kb DSC3 gene contains 16 exons and, along with two other desmocollins (DSC1 and DSC2), is expressed in the epidermis. In mouse and human Dsc1/DSC1, expression is restricted to the uppermost portion of the epidermis,19 Dsc2/DSC2 is very weakly expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis20 and Dsc3/DSC3 expresses mainly in the basal and first suprabasal layers of the epidermis.21 DSC3, like other cadherins, is a transmembrane component of the desmosomes and comprises of a number of domains, including a signal sequence (amino acids 1–27), a propeptide (28–135 amino acids), an extracellular domain (136–690 amino acids), a transmembrane domain (691–711 amino acids), and a c-terminal cytoplasmic domain (712–896 amino acids). The extracellular domain has been further divided into five cadherin domains (136–243, 244–355, 356–471, 472–579, and 580–690 amino acids). The first four of these subdomains contain repeats of approximately of 110 amino acids, and the fifth subdomain contains four cystein residues. Each cadherin repeat is an independently folding sequence that contains motifs with conserved sequences DRE, DXNDNAPXF, and DXD.22 The multiple cadherin domains form calcium-dependent rod-like structures with a calcium-binding site at the domain-domain interface. Calcium ions bind to specific residues in each cadherin repeat to ensure its proper folding and confer rigidity upon the extracellular domain, which is essential for cadherin adhesive function. The intracellular regions of cadherin repeats interact with intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton elements via desmosomal plaque proteins plakophilin, plakoglobin, and desmoplakin.23 In addition to mediating cell-cell contact, cadherins are involved in cell fate, signaling, proliferation, differentiation, and migration.

The nonsense mutation (p.Leu710X) identified in the family here is located at the junction of the transmembrane and the c-terminal cytoplasmic domain of DSC3. The mutation results in a premature termination codon, thereby predicted as causing nonsense-mediated decay of the mRNA or instability of the truncated protein.24 The role of DSC3 in normal function of desmosomes, maintenance of structural integrity of the interfollicular epidermis, and anchorage of the telogen hair shaft has been demonstrated in mice.1 These authors have shown that the skin phenotype of the Dsc3 null mouse is more severe than that of any other demosomal cadherin null mouse. The skin blisters reported in Dsc3 null mice1 were not present in patients in our family. However, skin vesicles filled with thin, watery fluid were observed in all of the affected individuals of the family. The hair phenotype in our patients has some features similar to those of Dsc3 null and Dsg3 null mice.1,16 In all four affected individuals of the family presented here, hairs were present at birth. After ritual shaving, hairs reappeared, but patches of hair loss continued to occur from time to time. This pattern of hair loss, as described by Chen et al.,1 suggested a defect in the anchorage of telogen follicles. These authors have further shown that hair is anchored in the skin by two epithelial cell layers that surround the lower region of the hair shaft. Given that both of these cell layers show high levels of DSC3, it is probable that the absence of this protein results in loss of cell adhesion and hair loss. The study reported here demonstrated, to our knowledge for the first time, a mutation in the human DSC3 gene that resulted in hair loss and the development of skin vesicles.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their family members for their participation in the present research work. This work was funded by the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Islamabad, Pakistan.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

International Human Genome Sequence Consortium, 2001, http://compgen.rutgers.edu/RutgersMap

Online Mendalian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/

USCS Genome Bioinformatics, March 2006, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway

References

- 1.Chen J., Den Z., Koch P.J. Loss of desmocollin 3 in mice leads to epidermal blistering. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:2844–2849. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kljuic A., Bazzi H., Sundberg J.P., Martinez-Mir A., O'Shaughnessy R., Mahoney M.G., Levy M., Montgutelli X., Ahmad W., Aita V.M. Desmoglein4 in hair follicle differentiation and epidermal adhesion: evidence from inherited hypotrichosis and acquired pemphigus vulgaris. Cell. 2003;113:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittock N.V., Bower C. Genetic evidence for a novel human desmosomal cadherin, desmoglein 4. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;120:523–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath J.A., McMillan J.R., Shemanko C.S., Runswick S.K., Leigh I.M., Lane E.B., Garrod D.R., Eady R.A. Mutations in the plakophillin 1 gene result in ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norgett E.E., Hatsell S.J., Carvajal-Huerta L., Cabezas J.C., Common J., Purkis P.E., Whittock N., Leigh I.M., Stevens H.P., Kelsell D.P. Recessive mutation in desmoplakin disrupts desmoplakin-intermediate filament interactions and causes dilated cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and keartoderma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2761–2766. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKoy G., Protonotarios N., Crosby A., Tsatsopoulou A., Anastasakis A., Coonar A., Norman M., Baboonian C., Jeffery S., Mckenna W.J. Identification of a deletion in plakoglobin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with palomoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair (Naxos disease) Lancet. 2000;355:2119–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green K.J., Gaudry C.A. Are desmosomes more than tethers for intermediate filaments? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:208–216. doi: 10.1038/35043032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan J.R., Shimizu H. Desmosomes: structure and function in normal and diseased epidermis. J. Dermatol. 2001;28:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller R., Heber B., Hashimoto T., Messer G., Mullegger R., niedermeier A., Herti M. Autoantibodies against desmocollin in european patients with pemphigus. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03241.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wali A., Chishti M.S., Ayub M., Yasinzai M., Kafaitullah, Ali G., John P., Ahmad W. Localization of a novel autosomal recessive hypotrichosis locus (LAH3) to chromosome 13q14.11-q21.32. Clin. Genet. 2007;72:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azeem Z., Jelani M., Naz G., Tariq M., Wasif N., Naqvi S.K.H., Ayub M., Yasinzai M., Amin-ud-din M., Wali A. Novel mutations in G protein coupled receptor gene (P2RY5) in families with autosomal recessive hypotrichosis (LAH3) Hum. Genet. 2008;23:515–519. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cottingham R.W., Jr., Indury R.M., Schaffer A.A. Faster sequential genetic linkage computations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;53:252–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudbjartsson D.F., Thorvaldsson T., Kong A., Gunnarsson G., Ingolfsdottir A. Allegro version 2. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1015–1016. doi: 10.1038/ng1005-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobel E., Lange K. Descent graphs in pedigree analysis: application to haplotyping, location scores, and marker sharing statistics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;58:1323–1337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafiq M.A., Ansar M., Mahmood S., Faiyaz ul-Haque M., Leal S.M., Ahmad W. A recurrent intragenic deletion mutation in DSG4 gene in three Pakistani families with autosomal recessive hypotrichosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;123:247–248. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch P.J., Mahoney M.G., Cotsarelis G., Rothenberger K., Lavker R.M., Stanley J.R. Desmoglein 3 anchors telogen hair in the follicle. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:2529–2537. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch P.J., Mahoney M.G., Ishikawa H., Pulkkinen L., Uitto J., Shultz L., Murphy G.F., Whitaker-Menezes D., Stanely J.R. Targeted disruption of the pemphigus vulgaris antigen (desmoglein 3) gene in mice causes loss of keratinocyte cell adhesion with a phenotype similar to pemphigus vulgaris. J. Cell Biol. 2007;137:1091–1102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chidgey M., Brakebusch C., Gustaffson E., Cruchley A., Hall C., Kirk S., Merritt A., North A., Tselepis C., Hewitt J. Mice lacking desmocollin1 show epidermal fragility accompanied by barrier defects and abnormal differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:821–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuber U.A., Schafer S., Stehr S., Rackwitz H.R., Franke W.W. Patterns of desmocollin synthesis in human epithelia: immunolocalization of desmocollin 1 and 3 in special epithelia and in cultured cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1996;106:677–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theis D.G., Koch P.J., Franke W.W. Differential synthesis of type 1 and type 2 desmocollin mRNAs in human stratified epithelia. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1993;37:101–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chidgey M.A., Yue K.K., Gould S., Byrne C., Garrod D.R. Changing pattern of desmocollin 3 expression accompanies epidermal organization during skin development. Dev. Dyn. 1997;210:315–327. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199711)210:3<315::AID-AJA11>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrod D., Chidgey M. Desmosome structure, composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:572–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stappenbeck T.S., Lamb J.A., Corcoran C.M., Green K.J. Phosphorylation of the desmoplakin COOH terminus negatively regulates its interaction with keratin intermediate filament networks. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:29351–29354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maquat L.E. Defects in RNA splicing and the consequence of shortened translational reading frames. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;59:279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong X., Murphy K., Raj T., He C., White P.S., Matise T.C. A combined linkage physical map of the human genome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:1143–1148. doi: 10.1086/426405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.