Abstract

A highly convergent synthesis of the sialic acid rich biantennary N-linked glycan found in human glycoprotein hormones, and its use in the synthesis of a fragment derived from the β-domain of human Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (hFSH) are described. The synthesis highlights the use of the Sinaÿ radical glycosidation protocol for the simultaneous installation of both biantennary side-chains of the dodecasaccharide as well as the use of glycal chemistry to construct the tetrasaccharide core in an efficient manner. The synthetic glycan was used to prepare the glycosylated 20–27aa domain of β-subunit of hFSH under a Lansbury aspartylation protocol. The proposed strategy for incorporating the prepared N-linked dodecasaccharide-containing 20–27aa domain into β-hFSH subunit was validated in the context of a model system providing, protected β-hFSH subunit functionalized with chitobiose at positions 7 and 24.

Introduction

Important recent developments in the fields of carbohydrate and polypeptide synthesis have now enabled organic chemists to consider the possibility, at various levels of realism, of gaining access to highly complex biomolecules through purely synthetic means.1 In particular, advances in the area of protein synthesis, including the development of solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS)2 as well as thiol-based ligation methods,3 have served to enable the preparation of polypeptides and small proteins. In nature, many biologically important proteins undergo post translational modifications, often resulting in the formation of highly complex heterogeneous glycoforms. The chemical synthesis of such glycoproteins still remains a daunting task, due to the paucity of chemical methods available for the incorporation of glycans into proteins, not to speak of the difficulties inherent in the syntheses of the complex glycans.

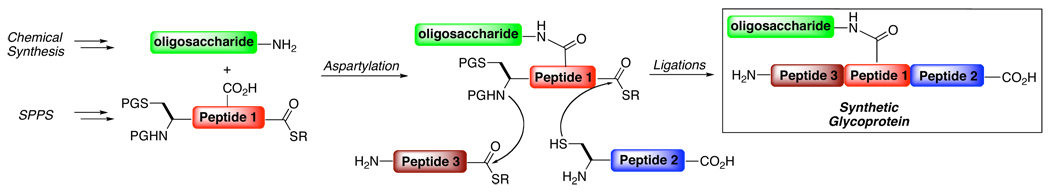

Our laboratory has a long-standing interest in the development of enabling protocols addressed to accomplishing de novo syntheses of naturally occurring glycoproteins of demonstrated therapeutic value. Each individual target will, of course, present its own unique set of synthetic challenges. Nonetheless, we are pursuing approaches for the general synthesis of glycoprotein target compounds. Our strategy for the assembly of N-linked glycoproteins is adumbrated in Figure 1.4 Thus, the oligosaccharide unit, prepared through chemical synthesis, is functionalized in the form of an anomerically aminated glycan. Next, the aminoglycan is merged with an aspartic acid-containing peptide under Lansbury aspartylation conditions.5 The resultant glycopeptide undergoes sequential ligations to provide the target glycoprotein. Indeed, we have been able to demonstrate the gross feasibility of this approach in the context of model systems. It is our ultimate goal to apply the convergent strategy outlined in Figure 1 to the total synthesis of highly complex glycoproteins (vide infra).

Figure 1.

Convergent approach to the synthesis of glycoproteins.

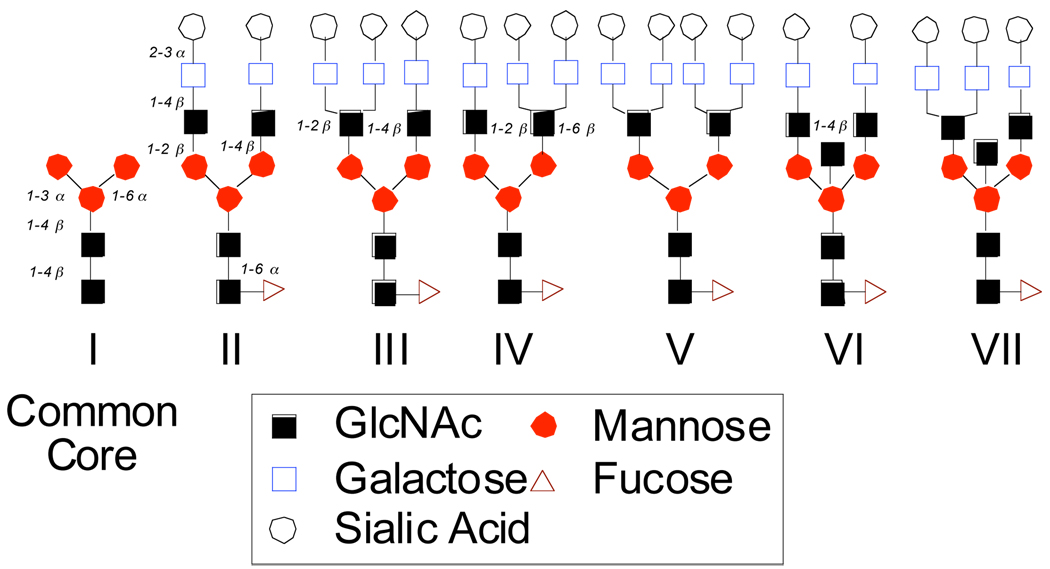

In investigating potential targets of N-linked glycoproteins with major biological activity, we first launched a program in the context of erythropoietin (EPO), used in the treatment of anemia.6 More recently we have been focused on Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (hFSH), which is used to treat anovulatory disorders associated with infertility.7 Other targets in our workscope include Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), Luteinizing Hormone (hLH), and Thyroid Hormone (hTH).8 Though these glycoproteins have varying structures and biological functions, all of them carry mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-sialo N-linked carbohydrates as illustrated in Figure 2. These structures possess a common core I (cf. Manα1–6[Manα1–3]Manβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–4[Fucα1–6]GlcNAc).9 The defucosylated version of I, previously synthesized by our group as well as by others,10 has been employed in the preparation of highly branched glycans frequently expressed on the prostate-specific antigen (PSA)11 and on gp120.12 A chemical total synthesis of structures II-VI constitutes a formidable challenge, due to the presence of multiple N-acetyl neuraminic acid (NAN) linkages as well as the labile fucose branching. The need to accommodate these chemically sensitive substructures serves to limit the range of available options for synthesis. We hoped to meet the challenge by synthesizing the dibranched dodecasaccharide II,8,9 a motif that has been found not only on all of the aforementioned hormones, but also on alpha fetoprotein,13 associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma, and on PSA.14 Once prepared, carbohydrate II could then be used to elaborate hormones by total synthesis according to the approach outlined in Figure 1.15 We first describe a pleasingly concise route to the 12-mer. From there we show how the 12-mer is incorporated in an FSH-like peptidyl domain. Finally, we demonstrate the general viability of the proposed scheme to a total synthesis of β-hFSH, through the total synthesis of a congener in which chitobiose units are inserted at the mature 12-mer linkage sites of the wild type.

Figure 2.

Sialylated N-linked carbohydrates found on some human glycoprotein hormones.

Results and Discussion

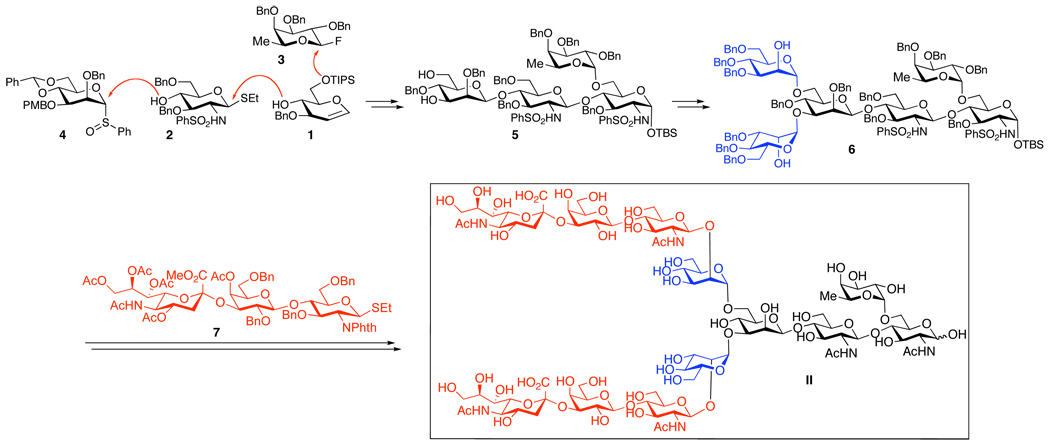

The synthetic logic toward dodecasaccharide II common to our targets is outlined in Scheme 1. The protecting group strategy was designed to minimize the number of required steps, while hopefully maximizing the yield and diastereoselectivity for the glycosidation steps. It was anticipated that global deprotection would be executed toward the end of the synthesis, presumably by reductive and base mediated steps.

Scheme 1. Synthetic strategy toward II.

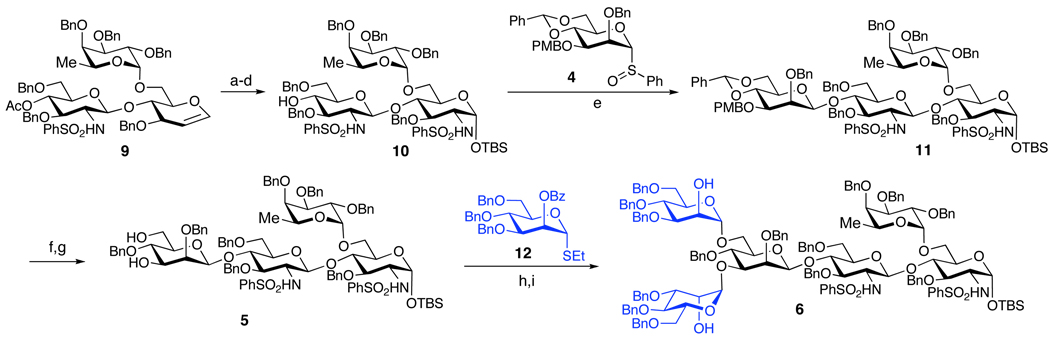

In order to take advantage of the symmetry of II, and to make the synthesis optimally convergent, a late stage bis-glycosidation of the hexasaccharide 6 with the sialic acid-containing trisaccharide 7 was planned. In turn, the symmetry of 6 would allow for a bis-glycosidation reaction of the precursor tetrasaccharide, 5. The latter would be assembled from the known building blocks 1–4, through the addition of an α-fucosylation step to the synthesis of the core I motif (i.e. Manα1–6[Manα1–3]Manβ1–4GlcNAcβ1–4GlcNAc), previously reported by our group.10c,d

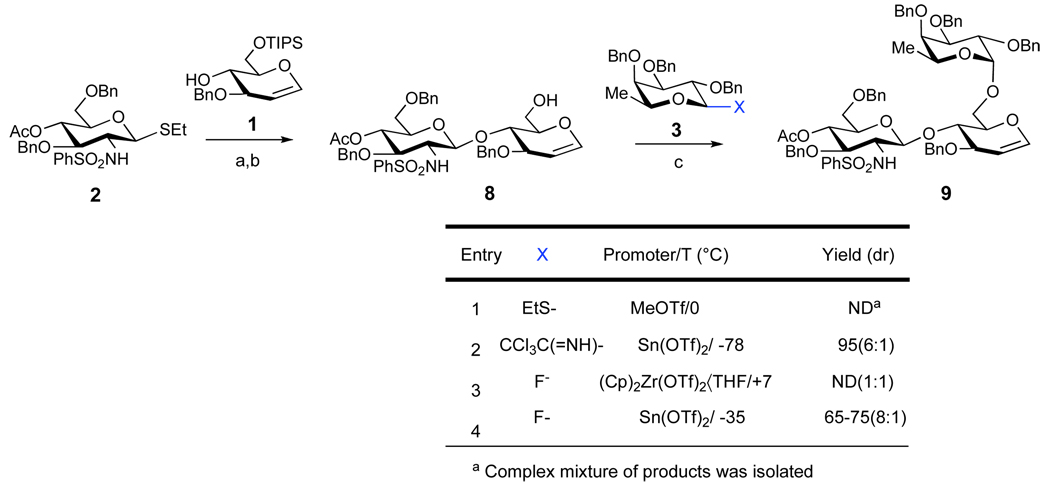

The progression to tetrasaccharide 5 commenced with the coupling of glycal 116 to the known glucosamine derivative 2,17 using MeOTf as a promoter (Scheme 2). The desired disaccharide was isolated in 55–72% yield as a 7:1 ratio of β:α anomers. This mixture was then treated with TBAF/AcOH in THF to remove the primary tri-isopropylsilyl protecting group. The resultant anomeric mixture was separable by column chromatography (98% yield). Next, the fucosylation of 8 was examined under various conditions. It was found that MeOTf-promoted 18 reaction of 8 with tri-O-benzyl-1-thioethylfucoside donor resulted in formation of a complex mixture of inseparable products (entry 1). When a mixture of anomeric fucosyl fluorides19 was employed in the coupling reaction, it was discovered that only the β-anomeric fluoride (3) was reactive, while the corresponding α-anomeric fluoride survived intact. The use of (Cp)2Zr(OTf)2•THF as a promoter20 (entry 3) gave poor levels of product diastereoselectivity at the newly fashioned glycosidic bond. Fortunately, however, Sn(OTf)2 was found to be a more favorable promoter. Following optimization, the reaction of the β -anomeric fluoride 3 and acceptor 8 proceeded in good yields (65–75%) and acceptable diastereoselectivity (8:1: α:β, entry 4).21 It was found that stoichiometric amounts of Lewis acid, administered in small portions, were required to drive the reaction to completion and to suppress yield erosion by isomerization of the β-anomeric fluoride to the more stable unreactive α-anomer. Superior to the fluoro method, the trichloroacetimidate derivative of tri-O-benzyl-L-fucose (entry 2) could be employed under Schmidt glycosidation conditions to provide the desired trisaccharide 9 in excellent yield (95%), and useful selectivity (6:1 α:β).22

Scheme 2. Assembly of the Trisaccharide Core.a.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) 1, MeOTf, DTBP, DCM, MS 4 Å, 0 °C; 55–72% (7:1 β:α); (b) TBAF, AcOH, THF; 98%; (c) 3, Sn(OTf)2 (4 × 0.25 equiv), DTBP, THF, MS 4 Å, −35 °C; 65–75% (8:1 α:β).

Having established a reliable route to 9, we next directed our attentions to the synthesis of the tetrasaccharide unit (5, Scheme 3). First, functionalization of the terminal glycal to the corresponding glucosamine derivative was achieved by the two-step procedure previously developed in our laboratory. 23 Thus, treatment of 9 with iodonium dicollidin perchlorate (IDCP) and benzenesulfonamide resulted in the formation of the 2-iodo-1-sulfonamide, which subsequently underwent a triethylamine-induced rearrangement in aqueous medium to the 2-sulfonamide-1-hydroxy derivative. The anomeric hydroxyl group of this product was protected, providing an anomeric silyl ether, exclusively as the α-anomer, and the acetate group was removed under Zemplèn conditions, furnishing the desired compound 10 (45–55%, 4 steps) as a single diastereomer. Subsequent triflatemediated β-mannosylation of 10 proceeded smoothly under Kahne-Crich protocols24 to provide tetrasaccharide 11 in 80–90% yield as a 6:1 β:α mixture of anomers. The undesired α-isomer could be removed during the deprotection of the C4 PMB group with cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN), to yield the desired product as a single isomer. Regioselective cleavage of the benzylidene acetal with BH3•THF in the presence of dibutyl boron triflate afforded the 3,6-diol, 5. Two-fold glycosidation of the latter with the mannose derivative, 12, was efficiently accomplished through the Sinaÿ radical activation protocol25 (80–90% yield), by analogy with the corresponding transformation employed in the PSA synthesis.11 The synthesis of hexasaccharide 6 was then completed through removal of the benzoate esters with NaOMe/MeOH (77–85% yield).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the 6.a.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) IDCP, PhSO2NH2, THF, MS 4 Å, 0 °C; (b) Et3N, H2O, THF; (c) TBSOTf, 2,6-lutidine, DCM; (d) NaOMe, MeOH, 45–55% (4 steps); (e) Tf2O, TBP, DCM, MS 4 Å, 80–90%, (5:1 α:β); (f) CAN, MeCN/H2O, 65–70%; (g) Bu2BOTf, BH3THF, DCM; 74–95%; (h) 10, (BrC6H4)3NSbCl6, MeCN, MS 4 Å, 10 °C to rt, 80–90%; (i) NaOMe-MeOH, 77–85%.

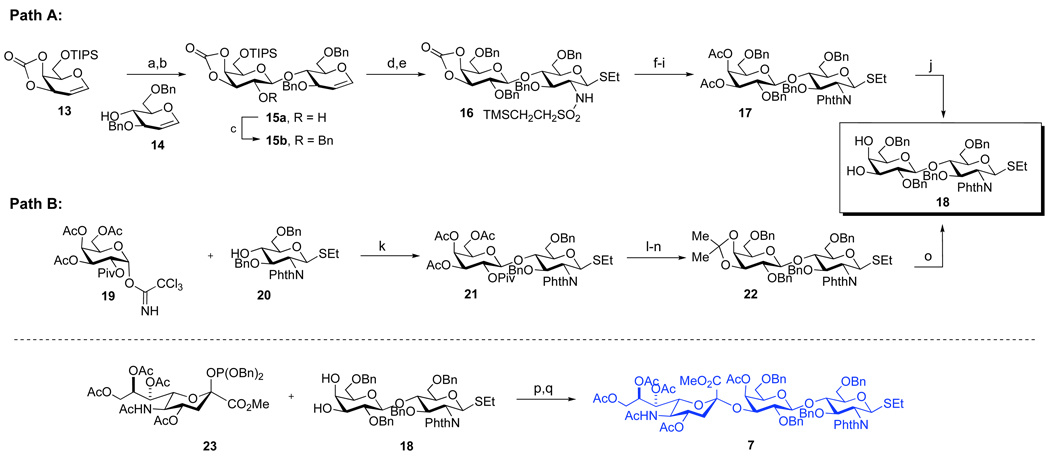

With hexasaccharide 6 in hand, we next turned to the synthesis of the sialic acid containing trisaccharide thiol donor, 7 (Scheme 4). The key disaccharide intermediate 18 could be prepared through two alternative pathways, as shown. According to Path A, the synthesis of 18 began with the known glycal intermediates, 13 and 14.26 Activation of 13 with DMDO,27 followed by reaction of the resultant dioxirane with 14 provided disaccharide 15a in 81% yield (2 steps). This product was benzylated to provide a fully protected glycal 15b, which underwent iodosulfonamidation and the subsequent “roll-over” reaction to yield the glucosamine derivative, 16 (92%, 2 steps).23 Compound 16 was next elaborated to the target disaccharide, 18, through a series of protecting group manipulations which included (1) replacement of the cyclic carbonate with acetate groups, (2) changing the sulfonamide group to the corresponding phthalimide moiety, and (3) removal of the acetate moieties through the action of sodium methoxide in methanol.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of the sialic acid containing trisaccharide 7.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) DMDO, DCM, 0 °C; (b) 14, ZnCl2, THF; MS 4 Å, 81% (2 steps); (c) BnBr, NaH, DMF, 70–80%; (d) IDCP, TMSCH2CH2SO2NH2, MS 4 Å, THF; (e) LHMDS, EtSH, DMF, 92% (2 steps); (f) NaOMe, MeOH, 90%; (g) Ac2O, Py, 92%; (h) CsF, DMF, 64–77%; (i) phthalic anhydride, Py, Piv2O, 74–85%; (j) NaOMe, MeOH, 86–90%; (k) TMOTf, DCM, MS 4 Å, −78 °C, 79% (>95:5 β:α); (l) NaOMe, MeOH, 97%; (m) (MeO)2CMe2, CSA, 68–80%; (n) NaH, BnBr, TBAI, THF, 80%; (o) HOAc (aq), 60 °C, 92%; (p) TMSOTf, MeCN, MS 4 Å, −40 °C (3.5:1 α:β); (q) Ac2O, Py, (35–45%, 2 steps).

Alternatively, the target disaccharide, 18, was reached through Path B, which was found to be more amenable to scale up. The synthesis commenced with Schmidt glycosidation of galactose donor 1928 with the known glucosamine acceptor 20,29 to provide the disaccharide 2130 in good yield and diastereoselectivity (79%, >95:5 β:α). This disaccharide was converted to 22 through NaOMe– mediated cleavage of the ester protecting groups, followed by selective re-protection of the 3,4-diol of the galactose as an acetonide, culminating in di-benzylation of the remaining hydroxyl groups (56%, 3 steps).31 The synthesis of the desired diol 18 was completed through removal of the acetonide function with aqueous acetic acid (92% yield). Finally, the coupling of 18 and known donor 23 was accomplished using TMSOTf as a promoter, following the protocol previously reported by our group.32 The resultant trisaccharide product was obtained as a 4:1 mixture of anomers, which was acetylated and purified to furnish 7 as a single α-anomer (35–45%, 2 steps).

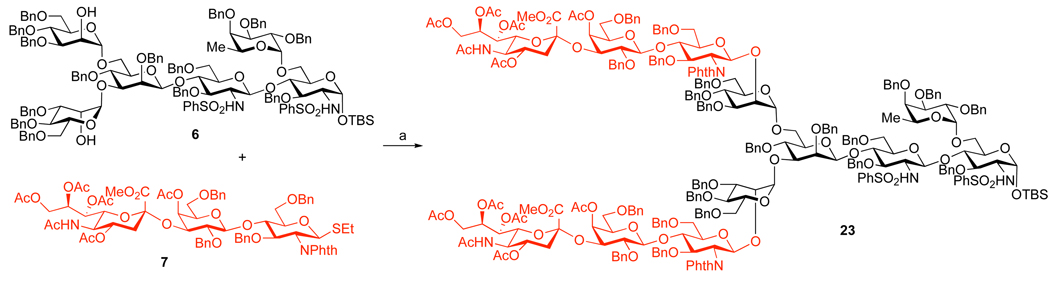

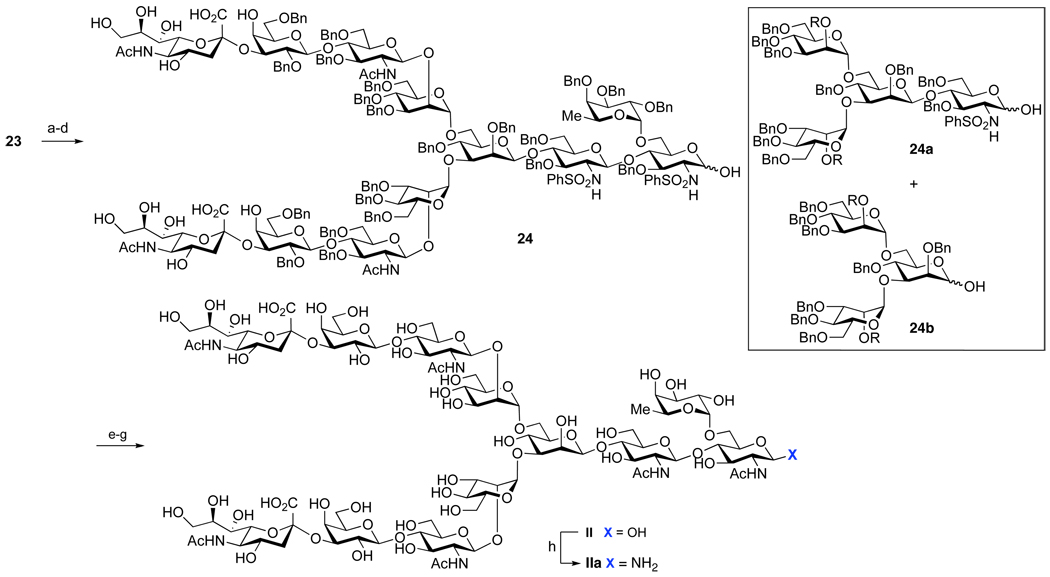

Having established routes to the key intermediates in the synthesis of II, the final bis-glycosidation of the hexasaccharide 6 with trisaccharide 7 was evaluated (Scheme 5). Of the various conditions examined, the Sinaÿ radical activation protocol25 was the most effective, producing the fully protected dodecasaccharide 23 in 74% yield, together with ca. 10–15% of the mono-glycosidated nonasaccharide.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of the protected dodecasaccharide.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) (BrC6H4)3NSbCl6, MeCN, MS 4 Å, 0 °C to rt, 74%.

Due to the high degree of functionalization of dodecasaccharide 23, the sequence for protecting group removal had to be evaluated with great care. Since the sialic acid methyl ester group would not be compatible with the usual conditions adopted for the removal of the phthalimide protecting group, the concomitant NaOMe-mediated hydrolysis of the methyl esters and acetyl protecting groups was undertaken first (Scheme 6). The resultant di-acid was treated with ethylenediamine, to remove the phthalimide protecting groups. The unmasked amines were re-protected through simultaneous reacetylation of the sialic acid portion.11 The subsequent removal of the anomeric t-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) protecting group (TBAF, AcOH) followed by cleavage of the acetates with sodium methoxide. Opening of the lactones with sodium hydroxide resulted in the formation of compound 24, together with the “peeling reaction” products 24a and 24b.33 Fortunately, the formation of 24a and 24b could be drastically reduced when the hydrolysis step was performed with NaOH in lieu of NaOMe. Finally, the benzyl and sulfonamide protecting groups were cleaved under our previously described Birch reduction conditions. The reader will note that this massive reductive deprotection can be conducted without reduction of the “reducing end” of the 12-mer.34 The product diamine was acetylated to yield the desired product, II. Our ultimate goal was to employ II for the construction of naturally occurring glycoprotein hormones. Accordingly, it was subjected to prolonged treatment with a saturated solution of NH4HCO3 at 40 °C.35 Excess of ammonium bicarbonate and water were removed by the repetitive lyophilization. This protocol provided glycosyl amine IIa in 54–63% yield over the entire deprotection sequence. Care was taken to minimize the exposure of IIa to aqueous medium, as anomeric amines are known to be unstable under these conditions.36

Scheme 6. Deprotection of the dodecasaccharide.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) NaOMe, MeOH; (b) NH2CH2CH2NH2, Toluene, n-BuOH, 90 °C; (c) Ac2O, Py; (d) TBAF, AcOH, THF; (e) NaOMe, H2O, MeOH; (f) Na, NH3, THF, −78 °C; (g) Ac2O, NaHCO3, H2O; (h) NH4HCO3, H2O, 40 °C (54–63% overall yield).

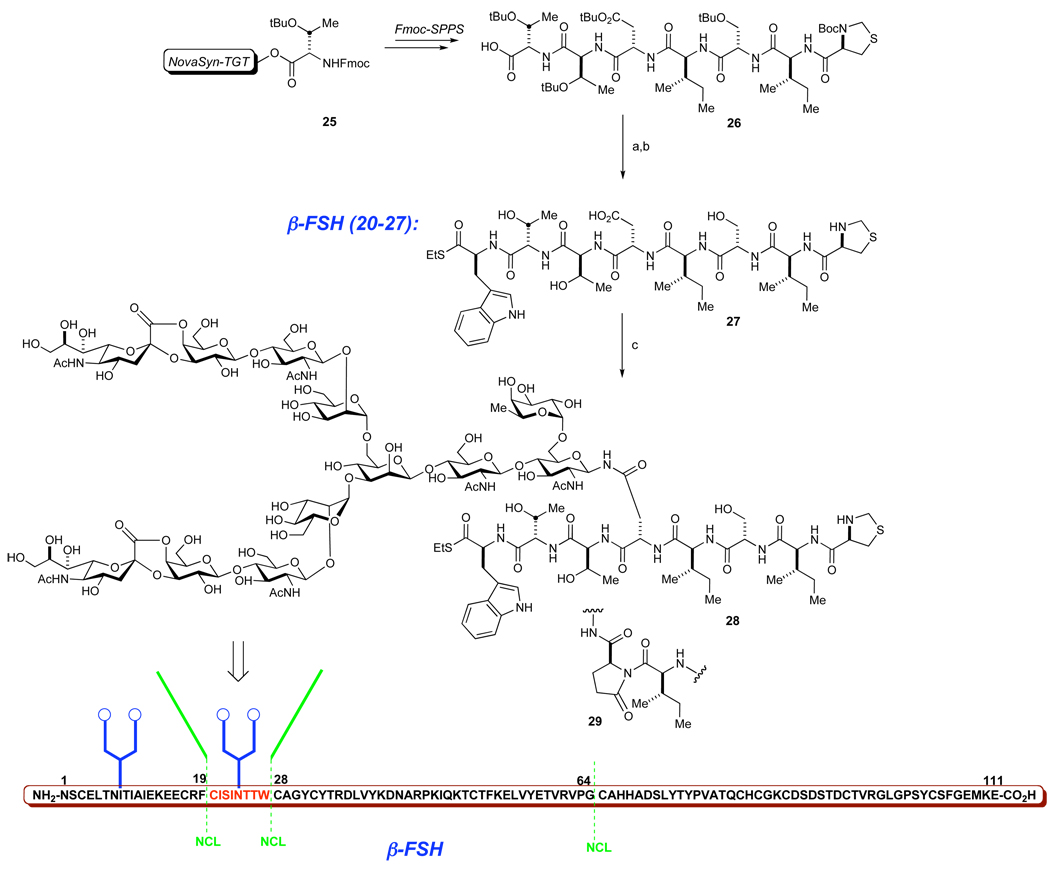

With the synthetic dodecasaccharide anomeric amine IIa in hand, we sought to evaluate its likely utility for the construction of the FSH β-subunit (Scheme 7).37 The complexity of the glycans, and a relatively long chain consisting of an 111 amino acid sequence serves to identify this glycoprotein as an extremely ambitious target for total synthesis. Fortunately, a relatively high frequency of cysteine distribution throughout the sequence allows one to consider bisecting this structure into simpler fragments, which could be assembled in the forward direction outlined in Figure 1. Accordingly, we defined as a target glycopeptide 27 (Figure 7), which could be constructed by a direct coupling of dodecasaccharide anomeric amine IIa and peptide 26 under modified Lansbury conditions.4,5 This glycopeptide contains C-terminal thioester and N-terminal Thz-protected cysteine that can be exploited to enable elaboration of 27 to β-subunit of FSH. The synthesis of 27 commenced with Fmoc SPPS of the protected peptide 26, starting from commercially available resin 25. After cleavage from the resin, 26 was coupled with tryptophane ethyl thioester under Sakakibara conditions with no epimerization being detected.38 Next, the peptide was treated with Cocktail B (trifluoroacetic acid, phenol, triisopropylsilane, H2O) to provide the desired precursor 27 (21% from 25).

Scheme 7. Coupling of the dodecasaccharide with the 20–27aa domain of hFSH β-subunit.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) H-Trp(SEt), EDC, HOOBt, TFE/CHCl3 (1:3); (b) TFA, PhOH, TIPS, H2O; 21% from 25; (c) IIa, HATU, DIEA, DMSO, ca. 25–35%.

Finally, we pursued the direct coupling of the dodecasaccharide with peptide 27. After some experimentation, the coupling was found to provide the desired product 28 in ca. 25–35% yield with one of the major side products being an aspartimide 29. Although 28 was isolated as a bis-lactone at the sialic acid termini, we believe that the required functionalities will be restored in the consequent ligation steps. 15b A crucial observation made during the preparation of 28 was the finding that the efficiency of the aspartylation reaction is drastically dependent on the quality of the anomeric amine after the Kochetkov amination. Thus, the use of highly pure batches of ammonium bicarbonate, prolonged lyophilization times and filtration of the insoluble residue were critical in providing reactive amine IIa.

It is known that ammonium bicarbonate is degraded during the course of such treatment, producing variable amounts of ammonium carbonate and ureas. These basic byproducts promote the formation of aspartamide, which is a serious impediment in the complex step.35,39 Not surprisingly, due to different conformational restrictions imposed by the aspartic acid residue, various peptide sequences exhibit different susceptibilities to such impurities. Only inorganic impurity free batches of IIa exhibited consistent reactivity in the Lansbury aspartylation of various peptides.

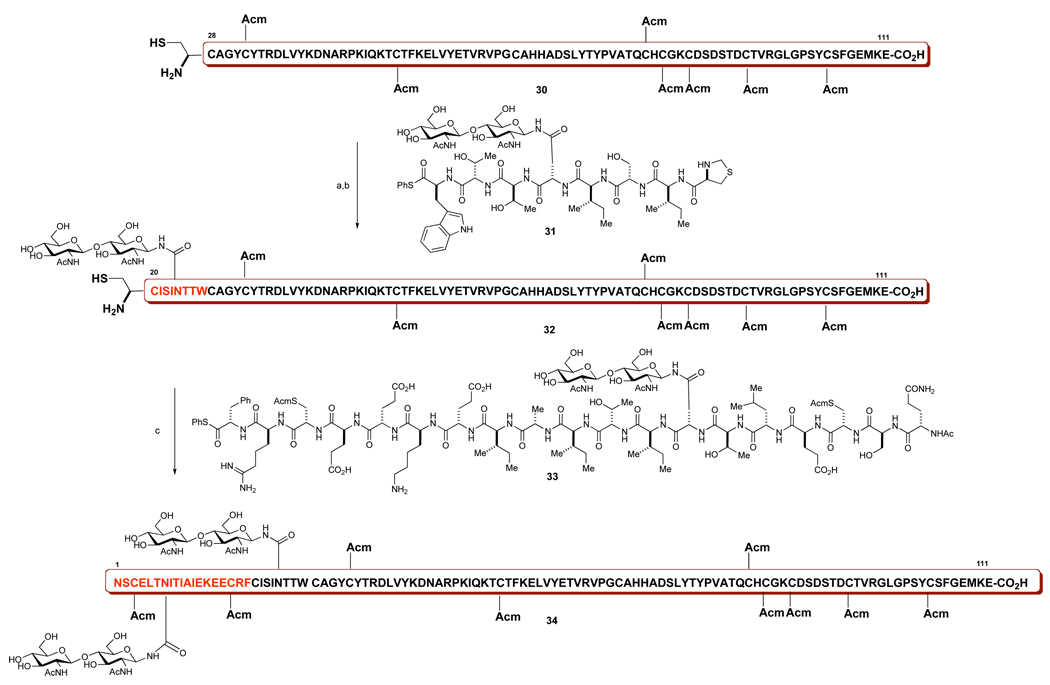

With the key dodecasaccharide-containing domain being successfully synthesized, we turned our attention to validating the proposed synthesis of β-FSH subunit (Scheme 7), using the corresponding fragments functionalized with a more available chitobiose disaccharide (Scheme 8). The glycopeptides 31 and 33 were prepared by methods similar to those described earlier for the preparation of compound 29 (Scheme 7).40

Scheme 8. Assembly of the β-FSH subunit with N-linked chitobiose.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) PhSH, Gnd·HCl, Na2HPO4, TCEPHCl (pH = 7.2); (b) NH2OMeHCl (pH = 4.6); 85% conversion, 15% yield; (c) PhSH, Gnd·HCl, Na2HPO4, TCEP·HCl (pH = 7.2), 64% yield.

The coupling studies commenced with construction of the 20–111aa subunit 32 by ligation of peptides 30 and 31. Thus, 31 and 30 underwent native chemical ligation in PBS (pH = 7.2) providing the desired product, which was treated in situ with O-methylhydroxylamine (pH = 4.5) to yield glycopeptide 32 (75% conversion, 27% yield after HPLC). The glycopeptide was isolated with its terminal cysteine residue deprotected and ready for coupling with glycopeptide 33. The all-crucial coupling step was conducted under standard NCL conditions (3% v/v PhSH, 6M Gnd·HCl, 0.1M PBS, pH = 7.2).3 The ligation between 33 and 32 proceeded smoothly. There was obtained the desired product 34 in 64% yield after purification by HPLC, together with the side product that presumably arises from the Met109 oxidation (ca.25%).40 We found this demonstration to be quite gratifying. Thus, the work shown here provides a plausible prospectus for reaching FSH itself. We now have significant confidence in the ability to generate the β FSH with fixed carbohydrates at wild type sites. Although the present demonstration involved a lactosamine model system, we are hopeful that these protocols will be applicable to inclusion of the dodecamer. Of course, from the stage corresponding to compound 34, in the 12-mer oligosaccharide series, we still have to master the intricacies of global deprotection and glycoprotein folding.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a highly convergent and stereospecific synthesis of the sialic acid rich biantennary N-linked glycan found in human glycoprotein hormones such as human Erythropoietin (hEPO), Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (hFSH), and Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) as well as in many other medicine-relevant glycoprotein targets. Our synthesis highlights the use of the Sinaÿ radical glycosidation protocol for the simultaneous installment of both biantennary side-chains, a task that is very difficult to achieve with complex carbohydrate systems. Moreover, it highlights the value of glycal chemistry first pioneered in these laboratories to construct the tetrasaccharide core (5) in an efficient manner. A carefully selected deprotection strategy allowed us to overcome the difficulties associated with the presence of the multiple sialic acid and labile fucose linkages, thus enabling access to significant quantities of the deprotected dodecasaccharide II.

We have also demonstrated that the presence of the multiple sialic acids as well as fucose branching does not pre-empt usage of the Kochetkov amination reaction or of subsequent Lansbury aspartylation of the resultant amine. The synthetic dodecasaccharide was used to prepare the glycosidated 20–27 domain of β-subunit of hFSH, which comprises an essential part of our program directed toward the synthesis of this glycoprotein hormone. Finally, the possibility of constructing the β-FSH subunit functionalized with N-linked dodecasaccharide was investigated using chitobiose-containing glycoproteins as a model. These studies demonstrate that the selected retrosynthetic bisections proposed for FSH could be successfully utilized for the preparation of the β-FSH subunit. Further synthetic efforts toward the construction of the homogeneous β-FSH with N-linked biantannary dodecasaccharide will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (CA103823 to SJD). P.N. thanks the National Institute of Health for a Ruth L. Kirschstein postdoctoral fellowship (CA125934-02). G.C. thank New York State Department of Health, New York State Breast Cancer Research and Education Fund (C020919). The Austrian Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (fellowship to B.F.) is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Dr. George Sukenick, Sylvi Rusli and Hui Fang of MSKCC NMR core facility for mass spectral and NMR spectroscopic analysis. We would like to express our appreciation to Rebecca Wilson for proofreadng the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and spectroscopic and analytical data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For selected examples of some recent syntheses or semisyntheses refer to: Becker CFW, Liu X, Olschewski D, Castelli R, Seidel R, Seeberger PH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8215–8219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802161.Pentelute BL, Gates ZP, Dashnau JL, Vanderkooi JM, Kent SBH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9702–9707. doi: 10.1021/ja801352j.Yamamoto N, Tanabe Y, Okamoto R, Dawson PE, Kajihara Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:501–510. doi: 10.1021/ja072543f.Torbeev VY, Kent SBH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1667–1670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604087.Kochendoerfer GG, et al. Science. 2003;299:884–887. doi: 10.1126/science.1079085.Kochendoerfer GG, Tack JM, Cressman S. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:474–480. doi: 10.1021/bc010128l.

- 2.Merrifield RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SBH. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wieland T, Bokelmann E, Bauer L, Lang HU, Lau H. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1953;583:129–149. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kemp DS, Galakatos NG, Bowen B, Tan K. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:1829–1838. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tam JP, Lu Y, Liu C, Shao J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:12485–12489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu C, Rao C, Tam JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:933–966. [Google Scholar]; (f) Tam JP, Yu Q. Biopolymer. 1998;46:319–327. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19981015)46:5<319::AID-BIP3>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Low DW, Hill MG, Carrasco MR, Kent SBH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6554–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121178598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Wu B, Chen J, Warren JD, Chen G, Hua Z, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4116–4125. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Yan LZ, Dawson PE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:526–533. doi: 10.1021/ja003265m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Crich D, Banerjee A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10064–10065. doi: 10.1021/ja072804l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Brik A, Yang Y-Y, Ficht S, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5626–5627. doi: 10.1021/ja061165w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Wan Q, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:9248–9252. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Haase C, Rohde H, Seitz O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6807–6810. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Chen J, Wan Q, Yuan Y, Zhu JL, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8521–8524. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Wan Q, Chen J, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15814–15816. doi: 10.1021/ja804993y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller JS, Dudkin VY, Lyon GJ, Muir TW, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:431–434. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Anisfeld ST, Lansbury PT., JR J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10531–10537. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Szymkowski DE. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Develop. 2005;8:590–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pavlou AK, Rechert JM. Nature Biotech. 2004;22:1513–1519. doi: 10.1038/nbt1204-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jelkmann W, Wagner K. Ann. Hematol. 2004;83:673–686. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ridley DM, Dawkins F, Perlin E. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1994;86:129–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Pang SC. Women’s Health. 2005;1:87–95. doi: 10.2217/17455057.1.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Herbert DC. Am. J. Anat. 1975;144:379–385. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001440311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dada MO, Campbell GT, Blake CA. Endocrinology. 1983;113:970–984. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-3-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rathnam P, Saxena BB. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:6735–6746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Saxena BB, Rathnam P. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:993–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Gharib SD, Wierman ME, Shupnik MA, Chin WW. Endocr. Rev. 1990;11:177–199. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-1-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pierce JG, Parsons TF. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981;50:465–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.002341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(9) Sairam MR. FASEB. 1989;3:1915–1926. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.8.2542111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mutsaers JHGM, Kamerling JP, Devos R, Guisez Y, Fiers W, Vliegenthart JFG. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;156:651–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Damm JBL, Kamerling JP, Van Dedem GWK, Vliegenthart JFG. Glycoconjugates. 1987;4:129–144. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hokke CH, Berwer AA, van Dedem GWK, van Ostrum JV, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81427-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Green ED, Baenziger JU. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Paulsen H, Lebuhn R. Carbohydr. Res. 1984;130:85–101. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsuo J, Nakahara Y, Ito Y, Nukada T, Nakahara Y, Ogawa T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995;3:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Danishefsky SJ, Hu S, Cirillo PF, Eckhardt M, Seeberger PH. Chem. Eur. J. 1997;3:1617–1628. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dudkin VY, Miller JS, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1791–1793. [Google Scholar]; (e) Totani K, Matsuo I, Ito Y. Bioorg. & Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:2285–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Dudkin VY, Miller JS, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:736–738. doi: 10.1021/ja037988s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dudkin VY, Miller JS, Dudkina AS, Antczak C, Scheinberg DA, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13598–13607. doi: 10.1021/ja8028137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Mandal M, Dudkin VY, Geng X, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2557–2561. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Geng X, Dudkin VY, Mandal M, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2562–2565. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taketa K. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:2595–2602. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajiri M, Ohyama C, Wada Y. Glycobiology. 2008;18:2–8. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For the completed syntheses of II refer to: Wu B, Hua Z, Warren JD, Ranganathan K, Wan Q, Chen G, Tan Z, Chen J, Endo A, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:5577–5579. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.045.Wu B, Tan Z, Chen G, Chen J, Hua Z, Wan Q, Ranganathan K, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8009–8011. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.045.Sun B, Srinivasan B, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:7072–7081. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800757.

- 16.(a) Nicolaou KC, Trujillo JI, Chibale K. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:8751–8778. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lohman GJS, Seeberger PH. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7541–7543. doi: 10.1021/jo034386i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schell P, Orgueira HA, Roehrig S, Seeberger PH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:3811–3814. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z-G, Warren JD, Dudkin VY, Zhang X, Iserloh U, Visser M, Eckhardt M, Seeberger PH, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4954–4978. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao L, Auzanneau F-I. Carbohydr. Res. 2006;341:2426–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaou KC, Caulfield TJ, Kataoka H, Stylianides NA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:3693–3695. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen JR, Allen JG, Zhang X-F, Williams LJ, Zatorski A, Ragupathi G, Livingston PO, Danishefsky SJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2000;6:1366–1375. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000417)6:8<1366::aid-chem1366>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spassova MK, Bornmann WG, Ragupathi G, Sukenick G, Livingston PO, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3383–3395. doi: 10.1021/jo048016l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wegmann B, Schmidt RR. Carbohydr. Res. 1988;184:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith DA, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:5811–5819. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Kahne D, Walker S, Cheng Y, Van Engen D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6881–6882. [Google Scholar]; (b) Crich D, Sun SX. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:435. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Zhang YM, Mallet JM, Sinay P. Carbohydr. Res. 1992;236:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)85007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marra A, Mallet JM, Amatore C, Sinay P. Synlett. 1990:572–574. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deshpande PP, Kim HM, Zatorski A, Park T-K, Ragupathi G, Livingston PO, Live D, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1600–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halcomb R, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6661–6666. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Seki M, Kayo A, Mori K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2357–2360. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schnabel M, Römpp B, Ruckdeschel D, Unverzagt C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:295–297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macindoe WM, Nakahara Y, Ogawa T. Carbohydr. Res. 1995;271:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Seeventer PB, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG. Carbohydr. Res. 1997;299:181–195. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spijker NM, Keuning CA, Hooglugt M, Veeneman GH, van Boeckel CAA. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:5945–5960. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharya SK, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:144–151. doi: 10.1021/jo9912496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkaline degradation of polysaccharides is a well-known process albeit rarely observed on the fully protected glycans. For an example of such degradations confer to: Aspinall GO, Krishnamurthy TN. Can. J. Chem. 1975;53:2171–2177.

- 34.Iserloh U, Dudkin V, Wang Z-G, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:7027–7030. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Likhosherstov LM, Novikova OS, Derevitskaja V, Kochetkov NK. Carbohydr. Res. 1986;146:C1–C5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isbell HS, Frush HL. J. Org. Chem. 1958;23:1309–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 37.For the application of dodecasaccharide II in the synthesis of homogeneous erythropoietin (EPO) fragments see reference 15b.

- 38.(a) Kuroda H, Chen YN, Kimura T, Sakakibara S. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1992;40:294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakakibara S. Biopolymers. 1995;37:17–28. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vetter D, Gallop MA. Bioconjugate Chem. 1995;6:316–318. doi: 10.1021/bc00033a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Refer to Supporting Information section for the details.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.