Abstract

We aim to study socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol related cancers mortality (upper aero-digestive tract (UADT) (oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, oesophagus) and liver) in men and to investigate whether the contribution of these cancers to socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality differs within Western Europe. We used longitudinal mortality datasets including causes of death. Data were collected during the 1990s among men aged 30–74 years in 13 European populations (Madrid, the Basque region, Barcelona, Turin, Switzerland (German and Latin part), France, Belgium (Walloon and Flemish part, Brussels), Norway, Sweden, Finland). Socioeconomic status was measured using the educational level declared at the census at the beginning of the follow-up period. We conducted Poisson regression analyses and used both relative (Relative index of inequality (RII)) and absolute (mortality rates difference) measures of inequality. For UADT cancers, the RII’s were above 3.5 in France, Switzerland (both parts) and Turin whereas for liver cancer they were the highest (around 2.5) in Madrid, France and Turin. The contribution of alcohol related cancer to socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality was 29–36% in France and the Spanish populations, 17–23% in Switzerland and Turin, and 5–15% in Belgium and the Nordic countries. We did not observe any correlation between mortality rates differences for lung and UADT cancers, confirming that the pattern found for UADT cancers is not only due to smoking. This study suggests that alcohol use substantially influences socioeconomic inequalities in male cancer mortality in France, Spain and Switzerland but not in the Nordic countries and nor in Belgium.

Keywords: Adult, Aged, Alcohol Drinking, Digestive System Neoplasms, epidemiology, Educational Status, Europe, epidemiology, Humans, Liver Neoplasms, epidemiology, Lung Neoplasms, epidemiology, Male, Middle Aged, Neoplasms, mortality, Respiratory Tract Neoplasms, Smoking, adverse effects, Socioeconomic Factors

Keywords: men, Europe, education, alcohol-related cancers, mortality

Introduction

Alcohol drinking is an important determinant for many causes of death, including cancer 1, 2. In many populations, a strong association is observed between socioeconomic position and alcohol related mortality with higher mortality among subjects with a low socioeconomic position 3–5. With regards to mortality from specific cancers related to alcohol use (liver, larynx, oral cavity, pharynx, oesophagus), however, variations in the level of socioeconomic inequalities among men are found between European populations. Large inequalities are found in Spain and Italy and, especially, in France 6–10. On the contrary, some studies have suggested small socioeconomic inequalities in the Nordic countries and Switzerland 10–12.

Nevertheless, the literature is rather scarce and a European overview of differences in socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol related cancers is currently lacking. It would be of interest to document the true extent of the problem within Europe. Contrary to smoking 13, the role of alcohol in socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality has not yet been evaluated but may also be important. In addition, a comparison between European populations would show whether different patterns in socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol-related cancers are found within Europe and whether these patterns could be related to different drinking cultures. Differences in national levels of alcohol related cancers mortality rates are found between Western European countries, with substantially higher rates in Spain and Italy, and especially in France 14. In addition, different drinking cultures are observed in Western Europe between countries but also within some countries. Daily wine consumption especially during meal is more common in countries like Spain, Portugal, Italy or France or in the Latin part of Switzerland whereas binge drinking and beer consumption is more widespread in the UK, the Nordic countries and the German part of Switzerland 15–17.

The aim of this study was to investigate differences in socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol-related cancers mortality between Western European populations. Our dataset included longitudinal studies from 13 populations from South to North of Western Europe with information on causes of death. We included populations with contrasted situations with regards to overall levels of alcohol related cancers mortality rates and drinking cultures.

We will first investigate socioeconomic inequalities among men in alcohol related cancers mortality, and thereby distinguish liver and upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) cancers. We will then focus on the contribution of alcohol related cancers to socioeconomic inequalities in mortality from all cancers types together. As UADT cancers are also smoking related, we will finally study lung cancer as an indicator of the smoking situation in each population and evaluate to which degree the international patterns of inequalities in UADT cancers are correlated with those for lung cancer.

Material and methods

Longitudinal data from 13 European populations were used, including Madrid, the Basque region (Spanish part), Barcelona, Turin, Switzerland (Latin and German part), France, Belgium (Brussels, Walloon and Flemish part), Sweden, Norway and Finland. Most datasets covered the entire national population, except for France (a representative sample of 1% of the population), Madrid and Basque region (regions), Barcelona and Turin (urban areas). In Belgium and Switzerland, we distinguished regions with differences in alcohol consumption and drinking patterns that could induce differences in socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol related cancers. Men were selected at the time of the population census and followed up during the 1990s (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive information on the data sources

| Population | Follow-up period |

Number of person years at risk | Educational level (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of census | End of follow-up | Lower secondary or less | Upper secondary | Post-secondary | ||

| Madrid | May 1996 | Dec 1997 | 1,756,059 | 64.1 | 17.4 | 18.5 |

| Basque region | May 1996 | June 2001 | 2,985,865 | 65.6 | 20.1 | 14.3 |

| Barcelona | Jan 1992 | Dec 2001 | 3,714,380 | 65.2 | 15.3 | 19.5 |

| Turin | Nov 1991 | Oct 2001 | 2,611,968 | 67.2 | 22.2 | 10.6 |

| France | Mar 1990 | Dec 1999 | 1,135,299 | 50.6 | 36.7 | 12.7 |

| Switzerland (Latin) | Dec 1990 | Dec 2000 | 3,180,536 | 24.6 | 51.6 | 23.8 |

| Switzerland (German) | Dec 1990 | Dec 2000 | 9,789,453 | 17.9 | 57.6 | 24.5 |

| Belgium (Walloon) | Mar 1991 | Dec 1995 | 4,053,514 | 63.0 | 21.4 | 15.6 |

| Belgium (Brussels) | Mar 1991 | Dec 1995 | 1,141,038 | 52.5 | 21.9 | 25.6 |

| Belgium (Flemish) | Mar 1991 | Dec 1995 | 7,506,231 | 61.5 | 22.2 | 16.3 |

| Norway | Nov 1990 | Nov 2000 | 10,021,675 | 29.9 | 48.4 | 21.7 |

| Sweden | Jan 1991 | Dec 2000 | 21,421,623 | 40.3 | 43.3 | 16.4 |

| Finland | Dec 1990 | Dec 2000 | 12,396,052 | 48.8 | 29.7 | 21.5 |

Analyses included men aged 30–74 at the census. The follow-up period was shorter for Belgium, Madrid and the Basque region. In order to have results on comparable ages in terms of observed ages at death, analyses for these three populations were conducted on slightly older age groups at baseline (35–79 for Madrid and 30–79 for Belgium and the Basque region).

The linkage between census data and mortality registries was achieved for more than 96% of all deceased persons in all populations except for Madrid (70%), the Basque region (93%) and Barcelona (94.5%). In these latter populations, however, no variation in this percentage was found according to age, sex or socioeconomic position (except in the Basque region for the latter factor). In order to avoid an underestimation of absolute mortality rates in these three populations, observed absolute mortality were increased by correction factors (1/0.70, 1/0.93 and 1/0.945 respectively).

The socioeconomic position (SEP) was measured with education declared at the time of the population census. This variable was categorized into three classes that corresponded to the ISCED (International Standard Classification of Education) classification: 0–2 (lower secondary education or less), 3–4 (upper secondary education), 5–6 (post-secondary education). The percentage of missing values for education was of 17% in Brussels, 5% in the Walloon and Flemish parts of Belgium and less than 3% for all other populations. These subjects were excluded from the analysis.

The cause of death was obtained by linkage with death registries. Analyses were conducted for all cancer mortality (ICD 9: 140–249), for lung cancer (ICD 9: 162–3, 165), and for alcohol related cancers: UADT (that groups oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus and larynx (ICD 9: 140–50, 161)) and liver (ICD 9: 155). UADT and liver cancer were selected for analyses because they are strongly associated with alcohol consumption 1, 18 and because they presented a substantial population attributable fraction (PAF) for alcohol (20–40% for UADT and 32% for liver 1, 19). Lung cancer was selected as an indicator for the cumulative exposure of the population to smoking. This approach is considered to be acceptable, although lung cancer mortality is only an approximate indicator 20.

The magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in mortality was estimated in both absolute and relative terms. To estimate relative inequalities, we computed relative indices of inequality (RII) using Poisson regression. The calculation of the RII is based on a ranked variable, which specifies for each educational group the mean proportion of the population with a higher level of education. For instance, the rank of the lowest educational group is calculated as the proportion of the population with middle or high education, plus half of the proportion of the population with a lowest educational level. The RII is then computed by regressing the mortality on this ranked variable. Thus, the RII expresses inequality within the whole socioeconomic continuum. It can be interpreted as the ratio of mortality rates between the two extremes of the educational hierarchy. As it takes into account the size and relative position of each educational group, it is well adapted to compare populations with different educational distributions 21, 22.

To estimate absolute socioeconomic inequalities we computed absolute rate differences between the lowest and the highest educational level, both for all cancer mortality and for the specific cancer types. Age-standardized mortality rates were computed, using the population of EU-15 plus Norway of 1995 as the standard population. The contribution of these different cancer types to socioeconomic inequalities in all cancer mortality was also calculated by expressing the rate difference for this cancer type as a percentage of the rate difference for all cancer mortality.

Results

The educational distributions highly differed between the populations (Table 1). The percentage of subjects with lower secondary education or less was the highest in the three Spanish populations and Turin (around 65%) and the lowest in Norway (less than 30%) and Switzerland (around 20%).

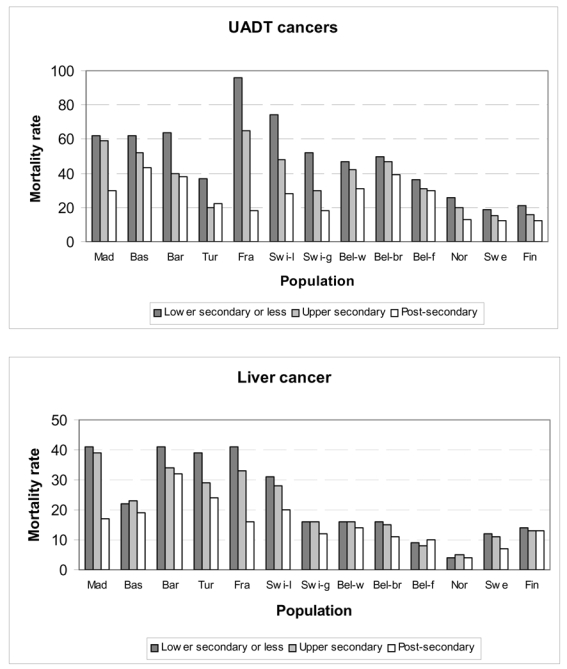

For UADT and liver cancers, we observed a regular inverse gradient in cancer mortality, with higher cancer rates for lower educational levels (Graph 1). Differences were found between populations and the situation is remarkable in France with the highest mortality rate among men with lower secondary education or less and among the lowest mortality rate among men with post-secondary education.

Graph 1. Alcohol related cancers mortality rates1 (per 100,000 person years) by education, per population.

1: Age-standardized mortality rate using direct standardization, per 100,000 person years

Note: UADT cancers group cancers of oral cavity, pharynx, larynx and esophagus.

Swi-l and Swi-g correspond to the Latin part and the German part of Switzerland. Bel-w, Bel-br and Bel-f correspond to the Walloon part of Belgium, Brussels and the Flemish part of Belgium.

For UADT cancers, the largest RII’s (above 3.5) were observed in France, Switzerland (German and Latin part), and Turin (Table 2). The RII was lower than 2 but still significant in Belgium. For liver cancer, the largest RII’s (above 2.5) were found in Madrid, France and Turin. In contrast, the RII was around 1 and non-significant in the Basque region, Belgium and Norway. For lung cancer, the largest RII’s (around 3 or above) were observed in Finland, Belgium and the German part of Switzerland. They were lower than 2 but still significant in the Spanish populations and France.

Table 2.

Mortality rates (MR) and relative indices of inequality (RII) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all cancers and by cancer type, per population

| UADT cancers1 |

Liver cancer |

Lung cancer |

All cancers |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | N2 | MR3 | RII (95% CI) | N2 | MR3 | RII (95% CI) | N2 | MR3 | RII (95% CI) | N2 | MR3 | RII (95% CI) |

| Madrid | 604 | 56 | 2.58 (1.71–3.89) | 392 | 38 | 2.76 (1.61–4.74) | 1,821 | 175 | 1.53 (1.22–1.92) | 6,133 | 591 | 1.52 (1.34–1.72) |

| Basque region | 1,519 | 59 | 2.04 (1.53–2.71) | 543 | 22 | 1.16 (0.72–1.87) | 3,133 | 125 | 1.31 (1.08–1.59) | 11,737 | 473 | 1.29 (1.17–1.43) |

| Barcelona | 1,974 | 52 | 3.12 (2.48–3.91) | 1,357 | 37 | 1.56 (1.20–2.02) | 6,254 | 169 | 1.80 (1.60–2.04) | 20,253 | 553 | 1.57 (1.47–1.68) |

| Turin | 735 | 33 | 3.61 (2.41–5.42) | 742 | 36 | 2.49 (1.69–3.68) | 3,895 | 179 | 2.53 (2.13–2.99) | 11,294 | 532 | 1.88 (1.71–2.06) |

| France | 816 | 78 | 4.30 (3.10–5.95) | 361 | 36 | 2.59 (1.63–4.12) | 1,462 | 147 | 1.64 (1.32–2.03) | 5,375 | 555 | 1.89 (1.69–2.13) |

| Switzerland (Latin) | 1,572 | 51 | 3.55 (2.92–4.31) | 807 | 27 | 1.62 (1.24–2.10) | 4,197 | 141 | 2.68 (2.38–3.01) | 14,862 | 504 | 1.85 (1.73–1.96) |

| Switzerland (German) | 2,893 | 32 | 3.99 (3.45–4.62) | 1,281 | 15 | 1.49 (1.21–1.85) | 10,681 | 123 | 2.96 (2.75–3.19) | 38,817 | 452 | 1.80 (1.73–1.87) |

| Belgium (Walloon) | 1,584 | 43 | 1.81 (1.44–2.29) | 524 | 15 | 1.11 (0.74–1.66) | 8,036 | 232 | 2.91 (2.58–3.28) | 19,982 | 583 | 1.81 (1.69–1.95) |

| Belgium (Brussels) | 429 | 47 | 1.48 (1.01–2.18) | 132 | 15 | 1.65 (0.81–3.38) | 1,590 | 175 | 2.97 (2.38–3.69) | 4,788 | 529 | 1.82 (1.61–2.050 |

| Belgium (Flemish) | 2,262 | 34 | 1.87 (1.53–2.28) | 557 | 9 | 0.98 (0.66–1.45) | 13,446 | 214 | 3.14 (2.85–3.46) | 33,990 | 544 | 1.79 (1.69–1.89) |

| Norway | 1,861 | 21 | 2.27 (1.90–2.71) | 384 | 4 | 1.00 (0.68–1.46) | 9,211 | 107 | 2.45 (2.26–2.65) | 38,722 | 449 | 1.45 (1.39–1.50) |

| Sweden | 3,331 | 17 | 2.03 (1.77–2.33) | 2,211 | 11 | 1.68 (1.42–1.98) | 13,804 | 70 | 1.81 (1.69–1.93) | 70,339 | 356 | 1.32 (1.28–1.35) |

| Finland | 1,868 | 19 | 2.38 (1.94–2.94) | 1,217 | 13 | 1.35 (1.05–1.73) | 12,489 | 138 | 3.48 (3.18–3.81) | 39,734 | 437 | 1.72 (1.64–1.80) |

UADT: upper aerodigestive tract (oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus)

Number of cancer deaths

Age-standardized mortality rate using direct standardization, per 100,000 person years

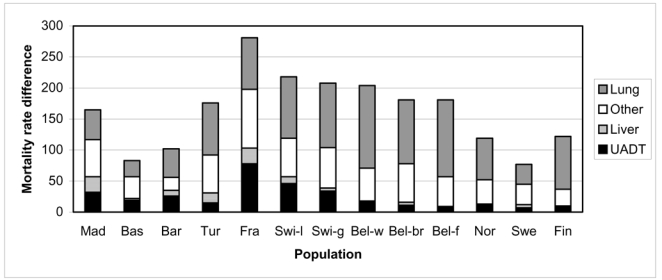

Absolute mortality rate differences by cancer site are presented in Graph 2. The most striking result is the large range of mortality rates differences found for UADT cancers: from 7 in Sweden to 78 per 100000 person years in France. It was between 20 and 40/100000 in the Spanish populations and Switzerland (German part) and 46 in Switzerland (Latin part). The contribution of these cancer sites to socioeconomic inequalities is presented in Table 3. The contribution of UADT cancers was the highest in France, Barcelona and the Basque region, (around 25%), followed by the Latin part of Switzerland and Madrid (20%). The contribution of liver cancer was much lower. However, we observed differences between populations with the largest contribution in Madrid (15%) and also a substantial contribution in France, Barcelona and Turin (9%) whereas it was lower than 6% in all other populations. All in all, the contribution of alcohol related cancer to socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality was 29–36% in France and the Spanish populations, 17–23% in the Swiss regions, and Turin, and 5–15% in Belgium and the Nordic countries.

Graph 2. Absolute mortality rate1 difference2 (per 100,000 person years) in all cancers mortality according to specific cancers, per population.

1: Age-standardized mortality rate using direct standardization, per 100,000 person years

2: between the two extreme educational levels (men with lower secondary education or less and men with post-secondary education)

Note: UADT= upper aero digestive tract (oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus)

Swi-l and Swi-g correspond to the Latin part and the German part of Switzerland. Bel-w, Bel-br and Bel-f correspond to the Walloon part of Belgium, Brussels and the Flemish part of Belgium.

Table 3.

Contribution (%) of different cancer sites to absolute socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality, per population

| Population | UADT cancer1 | Liver cancer | Lung cancer | Other cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid | 19 | 15 | 29 | 37 |

| Basque region | 25 | 4 | 31 | 40 |

| Barcelona | 26 | 9 | 45 | 20 |

| Turin | 8 | 9 | 48 | 35 |

| France | 27 | 9 | 29 | 35 |

| Switzerland (Latin) | 21 | 2 | 45 | 32 |

| Switzerland (German) | 16 | 3 | 50 | 31 |

| Belgium (Walloon) | 8 | 1 | 65 | 26 |

| Belgium (Brussels) | 6 | 3 | 57 | 34 |

| Belgium (Flemish) | 5 | 0 | 69 | 26 |

| Norway | 10 | 0 | 56 | 34 |

| Sweden | 10 | 5 | 42 | 43 |

| Finland | 7 | 1 | 70 | 22 |

UADT: upper aerodigestive tract (oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus)

Note: These percentages quantify the proportion of rate difference in cancer site mortality divided by the rate difference in all cancers mortality.

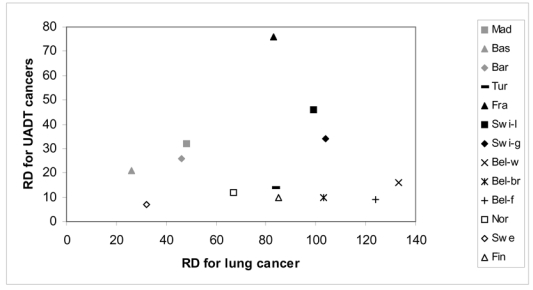

We do not observe a correlation between absolute inequalities for lung and UADT cancers (graph 3). Populations with the largest inequalities in lung cancer are not those with the largest inequalities in UADT cancers. Belgium shows large rate difference for lung cancer but small difference for UADT cancers. The rate difference for UADT cancers is similar in Madrid and the German part of Switzerland, whereas the rate difference for lung cancer is two times lower in Madrid. France shows particularly high difference for UADT cancers but only a medium rate difference for lung cancer. Also in terms of relative inequalities (RII’s), there is no correlation between mortality rates differences for lung and UADT cancers (see Table 2).

Graph 3. Mortality rate1 difference (RD) (per 100,000 person years) for upper aero digestive tract (UADT2) cancers and lung cancer, per population.

1: Age-standardized mortality rate using direct standardization, per 100,000 person years

2: UADT cancers group oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus cancers.

Note: Swi-l and Swi-g correspond to the Latin part and the German part of Switzerland. Bel-w, Bel-br and Bel-f correspond to the Walloon part of Belgium, Brussels and the Flemish part of Belgium.

Discussion

This study focused on differences between Western European populations with regards to socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol related cancer mortality. Large differences were found. Inequalities were largest in Spain, Switzerland and France and smallest in the Nordic countries and Belgium. In France, socioeconomic inequalities were remarkably large for UADT cancers. The contribution of alcohol-related cancers to socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality was high in France, Madrid and Barcelona (35%) compared to small (less than 5–15%) in Belgium and the Nordic countries. The lack of correlation between the inequalities found for lung and UADT cancers suggested that, even though smoking is a major risk factor for UADT cancers, large inequalities in UADT cancers were also due to other factors, probably alcohol drinking.

Evaluation of data

There are differences in the follow-up periods. Given the shorter follow-up period in Madrid, the Basque region and Belgium, we changed the age range at baseline for these populations such that studies were similar in terms of average at death. However, subjects may be slightly older or younger in these populations compared with others. This could have resulted in a slight under-estimation of relative socioeconomic inequalities and over-estimation of absolute inequalities for these populations. Nevertheless, these effects, if any, are likely to be small.

Some differences were found in the populations covered. In France and Switzerland, foreigners were excluded and analyses were thus conducted for more homogeneous populations. Perhaps the exclusion of foreigners has lead to underestimation of inequalities in alcohol-related cancers mortality in these countries. A large part of migrants, at least in France, come from Muslims countries and often do not drink alcohol for religious reasons 23. In France, they generally have low levels of UADT cancers mortality. For liver cancer, on the other hand, mortality rates among migrants are higher than in the native population but the etiology is different (due to Hepatitis B or C infection) 24–26.

Differences could occur between populations in the coding of causes of death. Even though data came from countries with reliable cause-of-death registries, national diagnosing practices may differ between countries. International comparisons revealed that more deaths were classified as cancer deaths in France than in other countries, probably leading to an overestimation of the French cancer mortality rates 27, 28. This bias could be a serious issue for absolute measures of inequalities, especially if it occurs more for some cancer sites (for instance UADT in France). With regards to relative measures of inequalities, our results would be biased only if diagnosing practices differ by socioeconomic position of the deceased, and if this applies especially to some cancer sites. There is no evidence to support this hypothesis.

In addition, there is a specific problem related to liver cancer mortality rates because of frequent misclassification of metastases as primary cancers. An American study suggested that between 27 and 31% of liver cancer deaths were due to metastases or secondary cancers instead of primary cancers 29. The results relating to liver cancer should therefore be considered cautiously. Unfortunately, no study investigated the potential association between socioeconomic position and misclassification as well as possible variations between countries. If the rate of misclassification does not differ by socioeconomic position, this problem would impact on absolute inequalities but not on relative inequalities.

Socioeconomic status was measured using information on educational level. We used a common classification for all populations that should avoid problems with the comparability between educational systems of different countries. However, large differences were observed between populations in the educational distributions. Part of these differences may be due to real differences in educational levels. But we cannot rule out the possibility that there are differences in the way in which educational systems are being squeezed into this common classification. However these differences probably have a weak influence on the results found here. We evaluated the sensitivity of the results to alternative educational classifications. In one type of analyses, for example, we used a classification into 4 educational levels by distinguishing between men who completed lower secondary education from men with primary education only. We also considered another classification in 3 educational levels in order to get population distributions that were as similar as possible between populations. The results obtained with these alternative classifications were quite similar to those presented here.

Several European countries were not included in this analysis. We did not include any country from Eastern Europe because of lack of longitudinal mortality studies. We also did not include the UK since British data were not accessible for small causes of death because of confidentiality rules. In the UK, a low contribution of non-lung cancers to socioeconomic inequalities in all cancer mortality was found in the 1980s 30 whereas this contribution was comparable to that of lung cancer in another study conducted in the 1990s 31.

Possible explanations of the results

Socioeconomic inequalities in the distribution of risk factors may largely explain the results. Smoking is a major risk factor for both lung and UADT cancers; the PAF for smoking for UADT cancers is indeed around 70%,. Therefore, smoking may potentially explain a large part of the observed inequalities in UADT mortality. Nevertheless, smoking alone cannot fully explain the international patterns in inequalities. The differences in inequalities in UADT cancer between countries with comparable inequalities in lung cancer mortality, especially between northern and southern countries, point to the effect of other factors. Given the high PAF found for alcohol (between 20 and 40%) 1, 19 for UADT cancers, alcohol consumption is certainly one of those factors.

Consequently, variations in drinking patterns between European populations may partly explain our results. It is unlikely that the type of alcohol accounts for the differences observed as the type of alcohol consumed does not seem to have an effect on risk of UADT cancers 32, 33. Differences in socioeconomic inequalities in the total amount of alcohol consumed may be the critical factor. In general, excessive alcohol consumption is found to be higher in men with low socioeconomic position, although results differ according to the country. No inequalities in high alcohol consumption are observed in Belgium 34 and inequalities are consistently reported for France 35, 36. A European study suggested that France was the country with the largest inequalities, but only for excessive consumption (more than 6 drinks per day) 34. Some studies do not report inequalities in Northern Italy 37 or Barcelona 38, whereas a European study observed inequalities in Spain, but only for excessive consumption 34. In Sweden, higher alcohol consumption was found among non-manual workers in the 1970s, but an equalization of the social differences in heavy drinking and a tendency to reversal were observed in later years 39. In Norway, higher alcohol consumption was observed in the upper education and income groups 40. Thus, even though the literature is not totally consistent, it is globally in accordance with our findings.

With regards to absolute inequalities, the absolute level of consumption has also to be taken into account. It is higher in France, Spain, Switzerland, Italy followed by Belgium and lower in Finland and especially low in Sweden and Norway 41. France thus presents a combination of both high level of alcohol consumption and relatively large inequalities in this consumption, followed by Spain. This may explain the largest absolute inequalities found in these populations.

We distinguished in Belgium and Switzerland different regions that could have relevant differences in drinking cultures. Whereas alcohol related cancer mortality rates gave a consistent “cultural” pattern with higher rates in the Walloon part of Belgium and especially in the Latin part of Switzerland, we observed in these regions only a slightly higher contribution of alcohol related cancers to inequalities in total cancer mortality. Few studies have been conducted on drinking pattern by linguistic region. They found no clear variations in Belgium 42 but higher daily and wine consumption in the Latin part of Switzerland compared to the German part 17. Our results for Belgium and Switzerland are thus globally consistent with these studies and with our results found in the bordering countries. However, we could have expected more pronounced differences between linguistic regions. It seems that between regions within the same country, the pattern of socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality only slightly differed around a global national pattern. These results suggest that national factors, such as common national histories, socioeconomic policies and health care systems, predominate over regional factors in determining socio-economic inequalities in cancer mortality.

The situation in France is remarkable because the large socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol related cancers, and especially in UADT cancers. The situation may not be homogeneous within France. Larger inequalities in all-cause mortality are found in French regions with a higher alcohol consumption, in particular in the North 43, 44. This result suggests that there could be large regional disparities in France in inequalities in alcohol-related mortality in general, and in alcohol-related cancer mortality in particular. The small size of our French dataset and resulting the lack of statistical power however hampered an regional analyses for France.

An important and consistent result in our study is that we do not observe large socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol-related cancer mortality in Northern Europe (Belgium and the Nordic countries). Some studies found a strong impact of alcohol drinking on health inequalities in the Nordic countries, but mainly through violent deaths 4, 5. Interestingly, it is also in those countries that binge drinking is more widespread, whereas Spain and France are characterized by higher levels of daily alcohol consumption. These results suggest that binge drinking is mainly associated with inequalities in violent deaths whereas high levels of daily consumption influences inequalities in mortality in part through specific cancers.

Other risk factors than alcohol drinking and smoking may also partly explain our results. Liver cancer is related to infection from Hepatitis B or C, but mainly in countries with high liver cancer incidence, which is not the case of Western Europe 45. Diet 46 and occupational exposures 47, 48 could also contribute to inequalities in mortality from UADT cancers, but their impact is likely to be weaker than that of alcohol.

Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival may partly explain socioeconomic differences in cancer mortality. Survival inequalities may be more important for cancers with a relatively good prognosis compared to cancer with very low survival rates 49–51. Thus, socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival might be more important for UADT cancers, as these have a better prognosis than liver or lung 52–55. Unfortunately, no comparative study is available on differences between European populations in socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival.

Conclusion

Inequalities in alcohol use have an impact on health inequalities in Europe. This has been shown by studies that found an impact of heavy drinking on socioeconomic inequalities in Northern Europe through poisoning, accidents and suicides. Our study showed that high alcohol consumption also impacts on health inequalities through cancer, but more so in Southern Europe (such as in Spain, France and Switzerland) than in Northern Europe. Thus, while heavy drinking is an important contributor to socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, there are large differences between populations in the relevant consumption patterns and associated causes of death.

Acknowledgments

G Menvielle received a funding from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale for this analysis. The Swiss data are from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. The construction of the Swiss National Cohort has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants No 32–5884.98 and 32–63625.00) and the Swiss University Conference (Network Public Health, Swiss School of Public Health). The project was in part funded by the European Commission, through the Eurothine project (from the Public Health Program, grant agreement 2003125) and the Eurocadet project (from the commission of the European communities research directorate-general, grant No SP23-CT-2005-006528).

Footnotes

Key statements: Inequalities in alcohol related cancers were larger in Southern Europe (Spain, France and Switzerland) than in Northern Europe.

The contribution of alcohol-related cancers to socioeconomic inequalities in cancer mortality was high in France, Madrid and Barcelona (35%) compared to small (less than 5–15%) in Belgium and the Nordic countries.

References

- 1.Boffetta P, Hashibe M, La Vecchia C, Zatonski W, Rehm J. The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking. Int J Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ijc.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Graham K, Rehn N, Sempos CT, Jernigan D. Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9:157–64. doi: 10.1159/000072222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makela P. Alcohol-related mortality as a function of socio-economic status. Addiction. 1999;94:867–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94686710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makela P, Valkonen T, Martelin T. Contribution of deaths related to alcohol use of socioeconomic variation in mortality: register based follow up study. BMJ. 1997;315:211–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7102.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemstrom O. Alcohol-related deaths contribute to socioeconomic differentials in mortality in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:254–62. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.4.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faggiano F, Lemma P, Costa G, Gnavi R, Pagnanelli F. Cancer mortality by educational level in Italy. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:311–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00051406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez E, Borrell C. Cancer mortality by educational level in the city of Barcelona. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:684–89. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menvielle G, Luce D, Geoffroy-Perez B, Chastang JF, Leclerc A Edisc group. Social inequalities and cancer mortality in France. 1975–1990. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:501–13. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-7114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faggiano F, Partanen T, Kogevinas M, Boffetta P. Socioeconomic differences in cancer incidence and mortality. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;138:65–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller H, Tonnesen H. Alcohol drinking, social class and cancer. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;138:251–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey Smith G, Leon D, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Socioeconomic differentials in cancer among men. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:339–45. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Cancer incidence, mortality from cancer and survival in men of different occupational classes. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:533–40. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000032370.56821.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackenbach JP, Huisman M, Andersen O, Bopp M, Borgan JK, Borrell C, Costa G, Deboosere P, Donkin A, Gadeyne S, Minder C, Regidor E, et al. Inequalities in lung cancer mortality by the educational level in 10 European populations. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bray F, Sankila R, Ferlay J, Parkin DM. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 1995. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:99–166. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Opinion Research Group EEIG. Health, food and alcohol and safety. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sieri S, Agudo A, Kesse E, Klipstein-Grobusch K, San-Jose B, Welch AA, Krogh V, Luben R, Allen N, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Clavel-Chapelon F, et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption in 10 European countries participating in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) project. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:1287–96. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calmonte R, Galati-Petrecca M, Lieberherr R, Neuhaus M, Kahlmeier S. Santé et comportement vis-à-vis de la santé en Suisse 1992–2002. [Health and health related behaviours in Switzerland 1992–2002] Office Fédéral de la Statistique. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boffetta P, Hashibe M. Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:149–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366:1784–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C., Jr Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet. 1992;339:1268–78. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91600-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pamuk E. Social class inequality in mortality from 1921 to 1972 in England and Wales. Popul Stud. 1985;39:17–31. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000141256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:757–71. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brahimi M. La mortalité des étrangers en France. [Mortality of foreigners in France] Population. 1980;3:603–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouchardy C, Parkin DM, Khlat M. Cancer mortality among Chinese and SouthEast Asian migrants in France. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:638–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouchardy C, Wanner P, Parkin DM. Cancer mortality among sub-Saharan African migrants in France. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:539–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00054163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouchardy C, Parkin DM, Wanner P, Khlat M. Cancer mortality among north African migrants in France. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:5–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Percy C, Muir C. The international comparability of cancer mortality data. Results of an international death certificate study. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:934–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jougla E, Pavillon G, Rossollin F, De Smedt M, Bonte J. Improvement of the quality and comparability of causes-of-death statistics inside the European Community. EUROSTAT Task Force on “causes of death statistics”. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1998;46:447–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Percy C, Ries LG, Van Holten VD. The accuracy of liver cancer as the underlying cause of death on death certificates. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:361–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunst AE, Groenhof F, Mackenbach JP, Health EW. Occupational class and cause specific mortality in middle aged men in 11 European countries: comparison of population based studies. EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. BMJ. 1998;316:1636–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7145.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huisman M, Kunst AE, Bopp M, Borgan JK, Borrell C, Costa G, Deboosere P, Gadeyne S, Glickman M, Marinacci C, Minder C, Regidor E, et al. Educational inequalities in cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and older men and women in eight western European populations. Lancet. 2005;365:493–500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17867-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlecht NF, Pintos J, Kowalski LP, Franco EL. Effect of type of alcoholic beverage on the risks of upper aerodigestive tract cancers in Brazil. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:579–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1011226520220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talamini R, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Dal Maso L, Levi F, Bidoli E, Negri E, Pasche C, Vaccarella S, Barzan L, Franceschi S. Combined effect of tobacco and alcohol on laryngeal cancer risk: a case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:957–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1021944123914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic differences in risk factors for morbidity and mortality in the European Community: an international comparison. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:353–72. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Laidier S. Quelques résultats sur les consommateurs de boissons alcooliques et de tabac en France en 1980. [Results on alcohol drinkers and smokers in France in 1980] SESI Informations rapides; 1983. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guignon N. Données sociales. Paris: INSEE; 1990. Alcool et tabac [Alcohol and smoking] pp. 254–57. [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Vogli R, Gnesotto R, Goldstein M, Andersen R, Cornia GA. The lack of social gradient of health behaviors and psychosocial factors in Northern Italy. Soz Praventivmed. 2005;50:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00038-005-4025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borrell C, Dominguez-Berjon F, Pasarin MI, Ferrando J, Rohlfs I, Nebot M. Social inequalities in health related behaviours in Barcelona. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:24–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romelsjo A, Lundberg M. The changes in the social class distribution of moderate and high alcohol consumption and of alcohol-related disabilities over time in Stockholm County and in Sweden. Addiction. 1996;91:1307–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91913076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strand BH, Steiro A. Alkoholbruk, inntekt og utdanning i Norge 1993–2000. [Alcohol consumption, income and education in Norway, 1993–2000] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2003;123:2849–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faso B, Salvador A. Alcohol per capita consumption, patterns of drinking and abstention worldwide after 1995. Eur Addict Res. 2001;7:155–57. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institut Scientifique de la Santé Publique. Enquête de santé par interview. [Health survey] Belgique 2001, 2002.

- 43.Picheral H. Aspects régionaux de l’alcoolisme et de l’alcoolisation en France. [Regional aspects of alcoholism and alcohol drinking in France] Paris: La Documentation française; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jougla E, Rican S, Péquignot F, Le Toullec A. La mortalité [Mortality] In: Leclerc A, Fassin D, Grandjean H, Kaminski M, Lang T, editors. Les inégalités sociales de santé. Paris: La Découverte; 2000. pp. 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas London W, McGlynn K. Liver cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 772–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosetti C, Gallus S, Trichopoulou A, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Influence of the Mediterranean diet on the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1091–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boffetta P, Kogevinas M, Westerholm P, Saracci R. Exposure to occupational carcinogens and social class differences in cancer occurence. IARC Sci Publ. 1997;138:331–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menvielle G, Luce D, Goldberg P, Leclerc A. Smoking, alcohol drinking, occupational exposures and social inequalities in hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:799–806. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosso S, Faggiano F, Zanetti R, Costa G. Social class and cancer survival in Turin, Italy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:30–34. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kogevinas M, Marmot MG, Fox AJ, Goldblatt PO. Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:216–19. doi: 10.1136/jech.45.3.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Auvinen A, Karjalainen S, Pukkala E. Social class and cancer patient survival in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1089–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berrino F, Gatta G. Variation in survival of patients with head and neck cancer in Europe by the site of origin of the tumours. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2154–61. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faivre J, Forman D, Esteve J, Obradovic M, Sant M. Survival of patients with primary liver cancer, pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2184–90. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faivre J, Forman D, Esteve J, Gatta G. Survival of patients with oesophageal and gastric cancers in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2167–75. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Janssen-Heijnen ML, Gatta G, Forman D, Capocaccia R, Coebergh JW. Variation in survival of patients with lung cancer in Europe, 1985–1989. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2191–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]