Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated a role for angiotensin II (AngII) and myofibroblasts (myoFb) in cardiac fibrosis. However, the role of PKC-δ in AngII mediated cardiac fibrosis is unclear. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the role of PKC-δ in AngII induced cardiac collagen expression and fibrosis. AngII treatment significantly (p<0.05) increased myoFb collagen expression, whereas PKC-δ siRNA treatment or rottlerin, a PKC-δ inhibitor abrogated (p<0.05) AngII induced collagen expression. MyoFb transfected with PKC-δ over expression vector showed significant increase (p<0.05) in the collagen expression as compared to control. Two-weeks of chronic AngII infused rats showed significant (p<0.05) increase in collagen expression compared to sham operated rats. This increase in cardiac collagen expression was abrogated by rottlerin treatment. In conclusion, both in vitro and in vivo data strongly suggest a role for PKC-δ in AngII induced cardiac fibrosis.

Introduction

Cardiac fibrosis is seen in several pathological conditions, such as hypertension, myocardial infarction and heart failure [1]. In a normal heart, collagens (type I & III) are major extracellular matrix (ECM) components, which facilitate the transmission of systolic and diastolic contraction [1]. Under disease conditions increased accumulation of interstitial collagens leads to fibrosis, which results in myocardial stiffness that ultimately disrupts coordination of myocardial excitation-contraction coupling in both diastole and systole [1-5]. During pathological conditions of the heart, activated ranin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) in cardiovascular disease induces the expression of TGF-β1 that in turn promotes the phenotypic conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts (α-smooth muscle actin positive cells) [1]. Activated myofibroblasts (myoFb) participate in the production of ECM collagen in response to pro-remodeling factors (AngII, ET1, TGFβ1 etc) [6-12]. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that inhibition of phenotypic conversion of fibroblasts to myoFb by cAMP could prevent the cardiac fibrosis [13,14], suggesting a key role for myoFb in ECM collagen expression/fibrosis.

AngII mediates various cellular functions involving PKC signaling in cardiovascular function and disease. Protein kinase C (PKC)-δ was the first new/novel PKC isoform that was identified based on the structural homology of its nucleotide sequences with those of classical/conventional PKC isoforms [15]. The δ isoform of PKC is expressed ubiquitously among cells and tissues. Several lines of evidence indicate that PKC-δ plays a critical role in cellular functions such as the control of growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [16, 17].

Recent studies have demonstrated involvement of PKC-δ signaling in cardiac disease [18-20]. Although a recent study suggested the participation of PKC-δ in AngII induced transactivation of ERK1/2 (a member of tyrosine kinase pathway) in cardiac fibroblasts [21], the mechanistic and functional interaction between PKC-δ and AngII in cardiac fibrosis is largely unknown. Therefore, the present study was designed to understand the role of PKC-δ in AngII induced cardiac collagen expression and fibrosis using both in vitro and in vivo models.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture and real time PCR reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MA, USA). Collagen type I and beta actin gene-specific primers and TaqMan probes were synthesized (Synthegen, LLC, Houston, TX). Rottlerin, a PKC δ specific inhibitor was obtained from Biomol International (PA, USA). Type I collagen antibody was purchased from Biodesign international (Saco, Maine USA). PKC δ antibody (anti PKC delta rabbit polyclonal antibody) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Animal protocol

Animal housing and experimentation were in accordance with the NIH guidelines and Institutional Animal care and use committee approved protocols. Similar aged (8-12 week old) male rats were divided into the following experimental groups: 1. Control (animals infused with vehicle control for AngII and Rottlerin); 2. Rottleirn (IP injection, 300μg/day/kg bw); 3. AngII (450ng/min/kg bw, using mini osmotic pumps for 2 weeks); and 4. AngII + Rottlerin. Under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, Alzet mini-osmotic pumps (Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) were implanted subcutaneously in the dorsal neck of 12 male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, IN USA) weighing 350–400g. AngII (Sigma, St. Louis USA) dissolved in physiological saline, was infused at a rate of 450ng/kg/min for 2 weeks. We did not notice any abnormalities in body weight or kidney and body weight ratio in rottlerin treated rats compared to control rats, suggesting that 2-week rottlerin treatment may not affect the normal physiology of rats (data not shown).

Heart Tissue Histology and Immunostaining

After a segment of heart tissue was removed it was immersion fixed with phosphate buffered 4% formaldehyde for overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, tissues were incubated in 30% sucrose in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer overnight at 4°C and then embedded in tissue freezing medium (Fisher Scientifics USA). 10 μm frozen sections of the heart tissue were washed with PBST (phosphate buffered saline + 0.3% Triton X-100) and sections were incubated in blocking buffer (PBST containing 10% goat serum) for 30 min and then incubated overnight with anti type I collagen (1:200 dilution) or alpha smooth muscle actin (1.100) antibody. After washing, slides were incubated with specific FITC labeled secondary antibody (Vector labs, CA, 1:400 dilution). Mounted slides were immediately analyzed under fluorescence microscope. At least 6 random focal fields (400 x) were selected from each LV and fluorescent measured using Image J software (NIH).

Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Trizol method was utilized to isolate total RNA from heart tissue. RNA was electrophoresed on denatured 1.2% agarose gel and the RNA quality was analyzed based on the 28s and 18s rRNA ratio. Two micrograms of total RNA was used for synthesis of cDNA using Promega (Madison, USA) kit and their instructions for cDNA synthesis. qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using collagen type I (Fam/Tamra labeled TaqMan probes, respectively) and beta actin (using Texas red/Tamra labeled TaqMan probe) gene specific sequences (Table 1). Twenty micro liter reaction volume was prepared by mixing 10 μl of iQ- supermix, 1 μl of cDNA, type I collagen primers and probe (5μM and 200nM, respectively), along with β-actin probe and primers (5μM & 200nM, respectively) and nuclease free water. qRT-PCR conditions were adapted from Chintalgattu et al 2004 (22). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed utilizing a Cepheid Smart Cycler real-time PCR (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) or iCyclerIQ (Bio-Rad). Gene copy number for type I collagen and β-actin were calculated using type I collagen and β-actin standard curves, respectively.

Table 1.

Primer and probes used in qRT-PCR

| Gene Name | Gene bank Accession No. |

Primer sequence 5′--------3′ | Product size bp |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I collagen | XM_213440. | Forward | GCGAAGGCAACAGTCGATTC | 69 |

| Reverse | CCCAAGTTCCGGTGTGACTC | |||

| Probe | ACAGCACGCTTGTGGATGGCTGC | |||

| β–actin | NM_007393 | Forward | AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC | 138 |

| Reverse | CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT | |||

| Probe | CACTGCCGCATCCTCTTCCTCCC |

Transfection of PKC-δ siRNA and PKC-δ over expression vector

pcDNA vector containing rat PKC-δ and PKC-δ dominant negative and other PKC isoform over expression vectors obtained from Farese RV group [23]. pcDNA PKC-δ and dominant −ve vectors (0.5μg DNA/ 35mm well) were transfected semi confluence myoFb cells along with pcDNA GFP (0.5μg DNA/ 35mm well) over expression vector using lipopectemine 2000 reagent and manufacturer recommended protocol (Invitrogen USA). After 48 hours of transfection, GFP expressing myoFb were selected using standard flowcytometric method. GFP positive cells were grown in 6 well plates until 90% confluence and then incubated in serum free medium 24 hours and used in RNA and protein isolation. GFP alone transfection did not alter the collagen expression or PKC delta activity as compared to PKC-δ +GFP transfection (data not shown).

Rat PKC-δ siRNA sequences (as described were previously; reference [24]) duplex PKC-δ siRNA sequences obtained from Invitrogen (USA). Block it transfection kit (Invitrogen USA) and green fluorescent siRNA was used to check the transfection efficiency. 80-90% confluent myoFb were transfected with of PKC-δ siRNA (250ng final concentration) along with control fluorescent siRNA. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were used as down stream applications (qPCR, PKC delta activity, Western Blot).

MyoFb isolation, PKC-δ kinase activity, western blot and cell proliferation assay

MyoFb were isolated, cultured, and treated according to previously published methods [6, 22]. PKC-δ kinase activity and western blot were analyzed as described previously [22]. Promega cell proliferation assay kit and manufacturer recommended assay protocol were used in the cell proliferation assay. Briefly, 40-50% confluent myoFb were cultured in serum free DMEM (Dulbecoo's modified Eagle's medium) for 24 hours and treated with AngII (10−7M) or AngII+rottlerin (3μM) and after 48 hours of treatment cell density was measured at 470nm using Promega assay reagents and protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as mean ± S.E.M. for a minimum of 4 to 6 determinations each of which was performed either in duplicate or triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using one-factor ANOVA, with P < 0.05 being considered significant.

Results

AngII induced PKC-δ kinase activity in both in vitro and in vivo

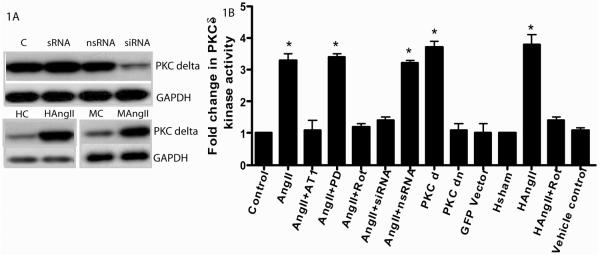

Western blot analysis of PKC-δ siRNA transfection showed several fold decrease in PKC-δ protein expression in cardiac myoFb as compared to nsRNA and control (Fig. 1A). Proteins from PKC-δ siRNA+AngII treated cells showed significant (*p<0.05) decrease in the PKC-δ kinase activity (1.4 folds) compared to nsRNA+AngII (3.2 folds) AngII (3.3 folds), fluorescent siRNA (1.1 folds) and control (1 fold) myoFb (Fig. 1B). Similarly rottlerin (PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor) treatment (1.2 folds)) significantly (*p<0.05) abrogated AngII induced PKC-δ kinase activity (Fig. 1B). PKC-δ over expression vector showed dramatic increase (*p<0.05) in PKC-δ kinase activity (3.7 folds) as compared to GFP-vector alone (1.1 folds) or PKC-δ dominant negative vector (1.2 folds) transfected myoFb (Fig. 1B). Protein lysates from rat heart showed rotterin+AngII (1.4 folds) treatment significantly (*p<0.05) decreased PKC-δ kinase activity as compared to AngII alone (3.8 folds), vehicle control alone (1.1 folds) rotterin alone (1.0 folds) treatment and sham control (1.0 folds) (Fig. 1B). This data suggests that AngII mediates PKC-δ kinase activity and PKC-δ inhibitors abrogate the AngII induced kinase activity both in vitro and vivo

Figure 1.

Fig 1A upper panel- Western blot Showing significant decrease (several folds) in the expression of myofibroblast PKC-δ in samples treated with PKC-δ siRNA compared to control, non specific siRNA (nsRNA) and scrambled siRNA (sRNA) (n=3). Fig 1A lower panel - shows significant increase in PKC-δ expression in both AngII treated myofibroblasts (MAngII) as well as AngII infused rat hearts (HAngII) compared to control myoFb (MC) and sham hearts (HC), respectively (n=4). Fig 1B shows the PKC-δ kinase activity in both myofibroblasts and rat heart. Myofibroblasts untreated and treated with AngII, AngII and its AT1 receptor blocker losarton (AngII+AT1 blocker), AngII and PKC-δ pharmacological blocker rottlerin (AngII+Rot), AngII and its AT2 receptor blocker (AngII+PD319177), Ang II its AT1 receptor specific siRNA (AngII+siRNA), PKC-δ over expression vector (PKCd). As compared, AngII+AT1, AngII+rot, and AngII+siRNA, AngII, AngII+PD, AngII+nsRNA and PKC-δ over expression vector showed significant increase in PKC-δ kinase activity (*p<0.05). AngII infused rat hearts demonstrated significant increase (*p<0.05) in PKC-δ kinase activity as compared to AngII along with PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor (HAngII+Rot) hearts or sham hearts.

PKC-δ plays a key role in AngII induced collagen expression

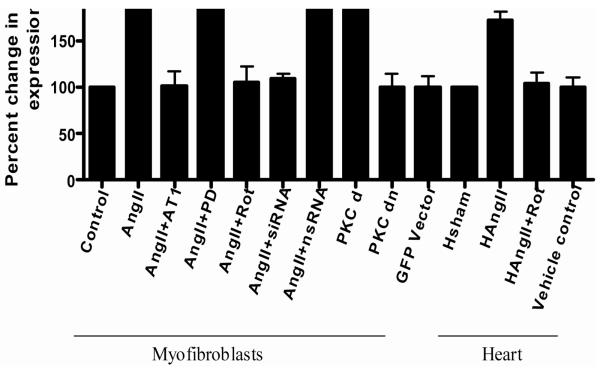

To determine whether rottlerin had any effect on the AngII mediated collagen type I expression, total RNA was extracted from treated (AngII, AngII+rottlerin, rottlerin) and untreated (Vehicle control) hearts that were subjected to quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The results shown in Fig. 1A demonstrated that rottlerin treatment (104%) abrogated AngII (172%) induced type I collagen expression, whereas rottlerin alone treatment did not alter the collagen expression when compared vehicle control. PKC-δ siRNA inhibition significantly reduced the AngII induced type I collagen expression (109%, 188% respectively) in primary cultures of myoFb. Similarly, PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor, rottlerin treatment also showed decrease in AngII induced collagen expression (106%; 188%, respectively) (Fig.2). PKC-δ over expression vector transfected cells showed significant increase (P<0.05) of collagen expression (212%) as compared to control (100%) or PKC-δ mutant vector (105%) transfected cells (Fig 2). This data strongly suggest a role for PKC-δ in AngII induced collagen expression/fibrosis both in vitro and in vivo system. The expression patterns for Type III collagen were similar to type I collagen in all experimental groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Shows the type I collagen expression in both in myoFb and rat heart. The AngII, AngII+PD, AngII+nsRNA and PKC-δ over expression vector (PKCd) induced significant amount of collagen expression and was abrogated in presence of AT1 blocker (AngII+Losarton), PKC-δ inhibitor rotllerin (AngII+Rot), and PKC-δsiRNA (AngII+siRNA) (*p<0.05). AngII+Losartan, PKC-δ mutant and vector alone did not alter the type 1 collagen expression in myoFb. AngII and PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor rottlerin (H AngII+Rottlerin) significantly reduced the AngII (H AngII) induced collagen expression in rat heart (*p<0.05).

Role of PKC-δ in AngII induced cardiac fibrosis and myoFb proliferation

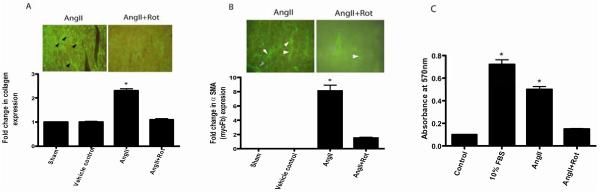

Immunofluorescence data showed that rottlerin treatment significantly (*p<0.05 AngII vs Rottlerin or control) abrogated the AngII induced type I collagen protein expression (2.3 folds) in the heart when compared to AngII+rottelrin (1.1 folds) vehicle control (1 fold) (Fig. 3A). Whereas, rottlerin alone treatment did not show significant effect on basal level of type I collagen expression in the heart (data not shown). Significantly higher myoFb phenotype (α smooth muscle positive) was noticed at the site of AngII induced fibrosis, suggesting that AngII induces the proliferation of myoFb (ECM producing phenotype), while these cells in turn produce the ECM (Fig 3A & 3B). On the other hand, AngII+rottlerin treatment significantly reduced the myoFb phenotype and collagen expression, suggesting a role for PKC-δ in AngII induced myoFb proliferation and collagen expression (Fig 3A & 3B). In in vitro, AngII induced myoFb proliferation was significantly reduced by rottlerin (3μM) treatment, suggesting a possible role for PKC-δ in AngII induced myoFb proliferation (Fig 3C).

Figure 3.

Fig 3A shows interstitial fibrosis in rat heart. AngII induced cardiac fibrosis significantly reduced by PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor treatment (*p<0.01) (n=4-6). Figure 3B shows significant increase in myofibroblast specific staining (alpha smooth muscle actin, white arrow head) in the AngII infused hearts as compared to AngII+Rottlerin, sham, vehicle control hearts (*p<0.05) (n=4-6). Gray arrowheads show the blood vessel staining. Figure 3C shows the myoFb cell proliferation in response to 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum), AngII, and AngII+Rottlerin (*p<0.05) (n=6).

Discussion

The present study shows that PKC-δ has a role in the AngII induced cardiac fibrosis. This study also demonstrated that a possible role for PKC-δ signaling in AngII induced myoFb proliferation and ECM expression at site of cardiac fibrosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that AngII induced myoFb proliferation and myoFb is associated with cardiac fibrosis (24-28). Earlier studies also reported up regulation of PKC-δ in several different pathological conditions of the heart (18-20). It is also known that AngII is one of the major humoral factors that cause pathological remodeling of the heart (29). More recently, it has been shown that PKC-δ association in AngII induced ERK activation in fibroblasts (21). However, mechanistically and functionally it is unclear how PKC-δ is involved in the AngII mediated pathological cardiac remodeling/fibrosis. To address this question, we choose well defined AngII infused fibrosis model (in vivo) and cardiac myoFb (in vitro).

Our in vitro studies with PKC-δ specific siRNA clearly demonstrated that silencing of PKC-δ expression by PKC-δ specific siRNA significantly decreased the PKC-δ protein expression, kinase activity and AngII induced collagen expression. To further prove the role of PKC-δ in collagen expression pathway, we generated a PKC-δ over expression and PKC-δ dominant negative expressing stable myoFb. The PKC-δ over expression myoFb showed significant increase in PKC-δ kinase activity and collagen expression as compared to control myoFb or PKC-δ dominant negative over expressing myoFb, suggesting a key role PKC-δ in the collagen synthesis pathway. Further PKC-δ specific pharmacological inhibitor rottlerin treatment significantly abrogated the PKC-δ kinase activity and AngII induced collagen expression in myoFb. These several lines of in vitro evidence using different methods clearly demonstrated a vitol role for PKC-δ in the AngII induced collagen synthesis. This data is constant with our previous report, which describes PKC-δ's role in endothelin −1 mediated collagen expression in myoFb (22). Studies from other groups also demonstrated the role of PKC-δ in TGFβ1 mediated collagen expression in renal and sclerodermal fibroblasts (11, 12). However, our study is the first study that clearly demonstrates PKC-δ's involvement in the AngII induced collagen expression.

Based on the encouraging in vitro data, we designed in vivo studies to prove our hypothesis that PKC-δ plays a role in AngII induced cardiac fibrosis. Results from both protein and RNA demonstrate that rotllerin treatment abrogated PKC-δ kinase activity and AngII induced cardiac fibrosis. Rottlerin alone treatment did not show significant effect on basal levels of collagen expression in the heart, suggesting that rottlerin specifically abrogates pathological accumulation of collagen expression in response to AngII in the heart. We also found that rottlerin+AngII treatment significantly decreased the cardiac hypertrophy (heart/body weight), blood pressure and as compared to treatment AngII alone (data not shown). Our ex vivo thoracic aortic compliance tissue bath data demonstrated abrogation of AngII mediated decrease in vascular compliance by rottlerin (data not shown), which may ultimately cause decrease in AngII induced BP. However, further research is required to understand the rottlerin effects on the vascular system.

It is clear from the literature that AngII mediates fibrosis by inducing the myoFb proliferation and these cells in turn participate in ECM collagen production in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner. In this study, we addressed the question of how PKC-δ inhibition reduced the AngII induced collagen expression either by decreasing myoFb proliferation or collagen expression or both. Our in vivo myoFb staining (α–SMA) suggests AngII induced myoFb proliferation; surprisingly rottlerin treatment significantly decreased the myoFb proliferation suggesting a possible role for PKC-δ in AngII induced myoFb proliferation. We found similar results with in vitro experiments. Lower concentrations (1.5μM) of rottlerin did not show much affect on myoFb proliferation but inhibited collagen expression (data not shown). Further studies are required to understand the specific or non-specific effects of rotterin on myoFb proliferation. This study clearly demonstrates that PKC-δ pharmacological inhibitor regulates the fibrosis by interfering with AngII induced myoFb proliferation as well as collagen synthesis.

Although several lines of evidence demonstrate rottlerin as a PKC-δ specific inhibitor (30-33), few studies suggested a non-specific role of rottlerin. Despite few controversies about rottlerin specificity, our current study suggests PKC-δ as a possible therapeutic target in AngII induced fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant, HL- R01-60047 awarded to LCK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berk BC, Fujiwara K, Lehoux S. ECM remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:568–575. doi: 10.1172/JCI31044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rysä J, Leskinen H, Ilves M, Ruskoaho H. Distinct upregulation of extracellular matrix genes in transition from hypertrophy to hypertensive heart failure. Hypertension. 2005;45:927–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000161873.27088.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirwany A, Weber KT. Extracellular matrix remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;48:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boluyt MO, O'Neill L, Meredith AL, Bing OH, Brooks WW, Conrad CH, Crow MT, Lakatta EG. Alterations in cardiac gene expression during the transition from stable hypertrophy to heart failure. Marked upregulation of genes encoding extracellular matrix components. Circ. Res. 1994;75:23–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díez J, Panizo A, Gil MJ, Monreal I, Hernández M, Pardo Mindán J. Serum markers of collagen type I metabolism in spontaneously hypertensive rats:relation to myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 1996;93:1026–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katwa LC. Cardiac myofibroblasts isolated from the site of myocardial infarction express endothelin de novo. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H1132–H1139. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01141.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chintalgattu V, Nair DM, Katwa LC. Cardiac myofibroblasts: a novel source of vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF) and its receptors Flt-1 and KDR. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katwa LC, Sun Y, Campbell SE, Tyagi SC, Dhalla AK, Kandala JC, Weber KT. Pouch tissue and angiotensin peptide generation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:1401–1413. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell SE, Katwa LC. Angiotensin II stimulated expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 in cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. J. Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1947–1958. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katwa LC, Campbell SE, Tyagi SC, Lee SJ, Cicila GT, Weber KT. Cultured myofibroblasts generate angiotensin peptides de novo. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:1375–1386. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber KT, Sun Y, Katwa LC, Cleutjens JP. Tissue repair and angiotensin II generated at sites of healing. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 1997;92:75–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00805565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber KT, Sun Y, Katwa LC. Myofibroblasts and local angiotensin II in rat cardiac tissue repair. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1997;29:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swaney JS, Roth DM, Olson ER, Naugle JE, Meszaros JG, Insel PA. Inhibition of cardiac myofibroblast formation and collagen synthesis by activation and overexpression of adenylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408704102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenga Y, Koh A, Perera AS, McCulloch CA, Sodek J, Zohar R. Osteopontin expression is required for myofibroblast differentiation. Circ. Res. 2008;102:319–327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitailo LA, Tibudan SS, Denning MF. Bax activation and induction of apoptosis in human keratinocytes by the protein kinase C delta catalytic domain. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;123:434–443. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayr M, Metzler B, Chung YL, McGregor E, Mayr U, Troy H, Hu Y, Leitges M, Pachinger O, Griffiths JR, Dunn MJ, Xu Q. Ischemic preconditioning exaggerates cardiac damage in PKC-delta null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H946–H956. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00878.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikkawa U, Matsuzaki H, Yamamoto T. Protein kinase C delta (PKC delta): activation mechanisms and functions. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2002;132:831–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein G, Schaefer A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Oppermann D, Shukla P, Quint A, Podewski E, Hilfiker A, Schröder F, Leitges M, Drexler H. Increased collagen deposition and diastolic dysfunction but preserved myocardial hypertrophy after pressure overload in mice lacking PKC epsilon. Circ. Res. 2005;96:748–755. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161999.86198.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun MU, LaRosée P, Simonis G, Borst MM, Strasser RH. Regulation of protein kinase C isozymes in volume overload cardiac hypertrophy. Mol, Cell, Biochem. 2004;262:135–143. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000038229.23132.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun MU, LaRosée P, Schön S, Borst MM, Strasser RH. Differential regulation of cardiac protein kinase C isozyme expression after aortic banding in rat. Cardiovasc, Res. 2002;56:52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson ER, Shamhart PE, Naugle JE, Meszaros JG. Angiotensin II-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation is mediated by protein kinase Cdelta and intracellular calcium in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension. 2008;51:704–711. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chintalgattu V, Katwa LC. Role of protein kinase Cdelta in endothelin-induced type I collagen expression in cardiac myofibroblasts isolated from the site of myocardial infarction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;311:691–699. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandyopadhyay G, Standaert ML, Kikkawa U, Ono Y, Moscat J, Farese RV. Effects of transiently expressed atypical (zeta, lambda), conventional (alpha, beta) and novel (delta, epsilon) protein kinase C isoforms on insulin-stimulated translocation of epitope-tagged GLUT4 glucose transporters in rat adipocytes: specific interchangeable effects of protein kinases C-zeta and C-lambda. Biochem. J. 1999;337:461–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irie N, Sakai N, Ueyama T, Kajimoto T, Shirai Y, Saito N. Subtype- and species-specific knockdown of PKC using short interfering RNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;298:738–743. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouzeghrane F, Mercure C, Reudelhuber TL, Thibault G. Alpha8beta1 integrin is upregulated in myofibroblasts of fibrotic and scarring myocardium. J .Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2004;36:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S, Ohta K, Hamaguchi A, Yukimura T, Miura K, Iwao H. Angiotensin II induces cardiac phenotypic modulation and remodeling in vivo in rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:1252–1259. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.6.1252. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schunkert H, Jackson B, Tang SS, Schoen FJ, Smits JF, Apstein CS, Lorell BH. Distribution and functional significance of cardiac angiotensin converting enzyme in hypertrophied rat hearts. Circulation. 1993;87:1328–1339. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber KT, Brilla CG, Campbell SE, Guarda E, Zhou G, Sriram ZK. Myocardial fibrosis: role of angiotensin II and aldosterone. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 1993;88:107–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72497-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brecher P. Angiotensin II and cardiac fibrosis. Trends. Cardiovasc. Med. 1996;6:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(96)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez SA, Gaidarova S, Saitta B, Sandorfi N, Herrich DJ, Rosenbloom JC, Kucich U, Abrams WR, Rosenbloom J. Role of protein kinase C-delta in the regulation of collagen gene expression in scleroderma fibroblasts. J Clin. Investig. 2001;108:1395–1403. doi: 10.1172/JCI12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Runyan CE, Schnaper HW, Poncelet AC. Smad3 and PKCdelta mediate TGF-beta1-induced collagen I expression in human mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2003;285:F413–422. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00082.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kucich U, Rosenbloom JC, Abrams WR, Rosenbloom J. Transforming growth factor-beta stabilizes elastin mRNA by a pathway requiring active Smads, protein kinase C-delta, and p38. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2002;26:183–188. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.2.4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gschwendt M, Muller HJ, Kielbassa K, Zang R, Kittstein W, Rincke G, Marks F. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:93–98. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]