Abstract

Radiolabeling of liposomes with 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h) is attractive for molecular imaging and monitoring drug delivery. A simple chelation procedure, performed at a low temperature and under mild conditions, is required to radiolabel pre-loaded liposomes without lipid hydrolysis or the release of the encapsulated contents. Here we report a 64Cu post-labeling method for liposomes. A 64Cu-specific chelator, 6-[p-(bromoacetamido)benzyl]-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid (BAT), was conjugated with an artificial lipid to form a BAT-PEG-lipid. After incorporation of 0.5% (mol/mol) BAT-PEG-lipid during the liposome formulation, liposomes were successfully labeled with 64Cu in 0.1 M NH4OAc pH 5 buffer, at 35 °C for 30~40 min with an incorporation yield as high as 95%. After 48 hour incubation of 64Cu-liposomes in 50/50 serum/PBS solution, more than 88% of the 64Cu label was still associated with liposomes. After injection of liposomal 64Cu in a mouse model, 44 ± 6.9, 21 ± 2.7, 15 ± 2.5, and 7.4 ± 1.1 (n = 4) % of the injected dose per cubic centimeter remained within the blood pool at 30 min, 18, 28, and 48 hours, respectively. The biodistribution at 48 hours after injection verified that 7.0 ± 0.47 (n = 4), and 1.4 ± 0.58 (n = 3) % of the injected dose per gram of liposomal 64Cu and free 64Cu remained in the blood pool, respectively. Our results suggest that this fast and easy 64Cu labeling of liposomes could be exploited in tracking liposomes in vivo for medical imaging and targeted delivery.

Keywords: liposome, Cu-64, PET, BAT

Introduction

Liposomes are widely used in preclinical and clinical applications as carriers of drugs, genes, or contrast agents (1, 2). The incorporation of hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) on the surface of liposomes further improves their properties (3). To obtain the biodistribution of long-circulating liposomes and to obtain non-invasive images in animals and humans, past studies have utilized liposomes loaded or labeled with radionuclides such as indium-111 (4), technetium-99m (5-7), and gallium-67 (8) for single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Labeling with fluorine-18 (9, 10) has been used for positron emission tomography (PET).

Three distinct approaches have been developed for the labeling or loading of liposomes with radioisotopes: (a) entrapping a soluble radiotracer inside the aqueous liposomal core, e.g., via chelating the pre-loaded polar ligand with 111In (11), 67Ga (12), or 99mTc-complex (5, 7), or via extrusion with 2-[18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (2-[18F]FDG) (13); (b) inserting radiolabeled lipid into the liposome bilayer (9, 10), and (c) attaching 99mTc onto the surface of liposomes via the chelation between 99mTc and a chelator-lipid conjugate (14, 15). In contrast to the extensive studies using SPECT to track liposomes in vivo, reports of PET imaging of liposomes are limited, although PET has many potential advantages (16). Previous reports have focused on the use of fluorine-18 to label liposomes (9, 10), but its short 110-min half-life makes extended studies difficult. In the treatment of diseases such as cancer, it is desirable to create stable particles that can circulate and accumulate in tumors over days to weeks (17, 18). Because of the temperature dependence of liposome structures (19), these particles may not withstand exposure to high temperatures after formulation. Here, we report a gentle post-labeling method using 64Cu (half-life 12.7 h) and its application to track liposomes over 48 hours. For the surface chelation method, the incorporation of a lipid-PEG-chelate conjugate (Scheme 1) in the liposome bilayer (Figure 1) was chosen, as used in previous nuclear medicine studies (14, 20). Previous surface chelation methods used lipid-chelate conjugates such as octadecylamine diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) (15), dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine-diethylenetriaminetetraacetic acid (DPPE-DTTA) (20, 21), and hydrazino nicotinamide (HYNIC) conjugated-DSPE (14). However, none of those reagents have been shown to bind copper stably under physiological conditions, nor would they be expected to, due to the kinetic properties of the copper ion. Among several effective copper(II) macrocyclic chelators, such as DOTA, NOTA, TETA and TE2A (22, 23), we chose 6-[p-(bromoacetamido)benzyl]-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid, BAT(24), as the chelating ligand. BAT, a derivative of 6-benzyl-TETA (Scheme 1), has been found to form stable (25, 26) and highly selective complexes with copper(II) (27), and has been utilized for antibody labeling (28, 29) for preclinical and clinical trials. Although the cross-bridged ligand TE2A has been shown to be very stable for radiolabeling small molecules (30), the heating step (> 70 °C) required for the incorporation of 64Cu into TE2A exceeds the transition temperature of many liposomal formulations (thus releasing the contents) and could also alter lipid structure in other ways, such as hydrolysis.

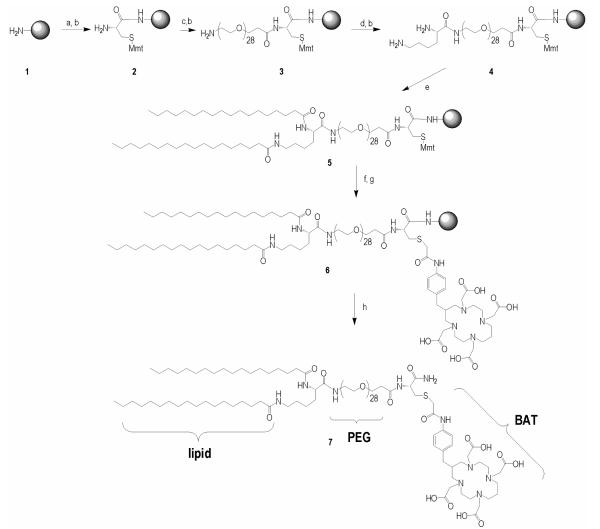

Scheme 1.

Solid phase synthesis of BAT-PEG-lipid Reagents: a) Fmoc-cysteine (2 eq.), HBTU (O-benzotriazole-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate) (2 eq.), DIPEA (4 eq.), 60 min; b) 20% piperidine in DMF, 2 × 10 min, 10 min; c) Fmoc-PEG28-COOH (1.1 eq.), HBTU (1.1 eq.), DIPEA (2.2 eq.), 60 min; d) Fmoc-Lys(Fmoc)-OH (2 eq.), HBTU (2 eq.), DIPEA (4 eq.), 60 min; e) stearic acid (4 eq.), HBTU(4 eq.), DIEA(8 eq.), 60 min; f) 1% TFA/DCM, 5 × 3 min; g) BAT(1.5 eq.), DIPEA (10 eq.), 4 hours; h) TFA/TIPS/H2O (95/2.5/2.5), 3 hours.

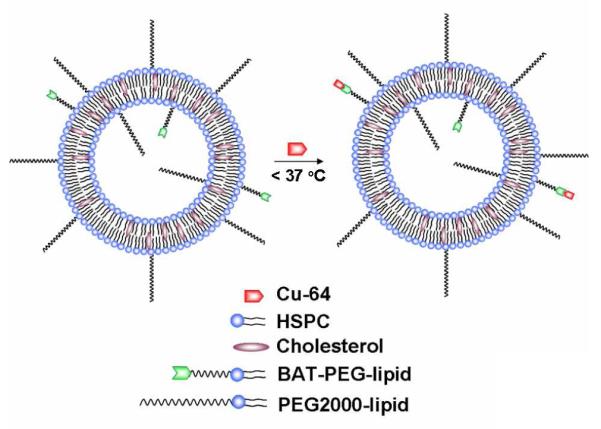

Figure 1.

Surface chelation model of 64Cu-labeled long circulating liposomes, where labeling was performed under mild conditions (< 37 °C) to preserve liposome stability and loading during labeling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Fmoc-Cys(Mmt)-OH, Fmoc-NH-PEG28COOH, Fmoc-Lys(Fmoc)-OH, and coupling agent (HBTU, 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate) were purchased from EMD Biosciences (La Jolla, CA), and stearic acid from Sigma-Aldrich. Fmoc-PAL-PEG-PS resin (0.16-0.21 mmol/g) was from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Solvents and other agents were all of analytical purity and from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) and VWR (Brisbane, CA). All lipids and a mini-extruder were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). 64CuCl2 was purchased from Trace life Science (Denton, TX, specific activity > 80,000 Ci/g for in vitro and in vivo studies) or Nordion (Ontario, Canada, specific activity > 5000 Ci/g for the feasibility study) under a protocol controlled by the University of California, Davis. High purity ammonium acetate (≥ 99.995%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). PBS was purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Mouse serum was purchased from Innovative research (Novi, MI). All eppendorf tubes and glassware for labeling were pre-washed with absolute ethanol and acetone and dried in an oven before use.

The synthesis of lipid-PEG-Cys(BAT) conjugate (7)

As shown in Scheme 1, 7 was synthesized by Fmoc solid phase synthesis. In brief, Fmoc-Cys(Mmt)-OH, Fmoc-PEG28-COOH, Fmoc-Lys(Fmoc)-OH and stearic acid were coupled to the PAL-PEG-PS resin sequentially, to obtain 5. After the protecting group, Mmt, was removed with 1% TFA/DCM, BAT (24) was coupled onto the resin in the solvent (DMF:DMSO:H2O = 1:1:1, v/v/v), at pH = 8.0 ± 0.5, adjusted with DIPEA. The reaction was monitored with DTNP solution. The final product (7 in Scheme 1) was cleaved from the resin by TFA/TIPS/H2O mixture (TFA/TIPS/H2O = 95:2.5:2.5, v/v/v) and purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), with the mass confirmed by MALDI-TOF (M+H+, measured: 2662, calculated: 2663). Reversed-phase HPLC was performed using a Phenomenex Jupiter 4μ Proteo 90A (250 × 4.6 mm, analytical), and a Phenomenex Jupiter 10μ Proteo 90A (250 × 10.0 mm, semi-preparative) with a gradient from 10-90% B in 30 min (solvent A: 0.05% TFA, solvent B: acetonitrile) and a flow rate of 1.5 or 3.0 mL/min for the analytical/semi-preparative column. The retention time of the BAT-PEG-lipid conjugate was 35.5 min. MALDI was measured with ABI-4700 TOF-TOF (Applied Biosystems) using matrix sinapinnic acid with a 3-layer sample preparation method (31). The MALDI spectral results are shown in Figure 2.

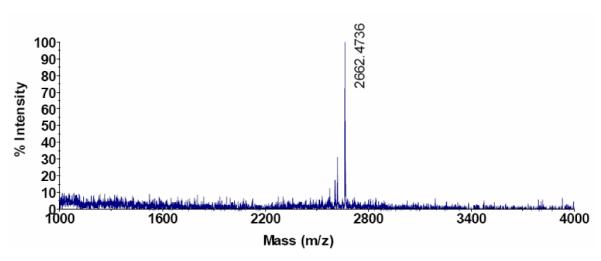

Figure 2.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) spectrum of conjugated BAT-PEG-lipid.

BAT-liposome preparation

Lipids in chloroform were mixed in a test tube, and dried by gently blowing nitrogen gas with vortexing to create a thin film, which was further dried under vacuum overnight to completely remove chloroform. The dried lipid thin film was re-suspended by adding 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5) and incubated for 5-10 min at 60 °C. After 1 minute sonication, this lipid mixture was extruded by 21 passes through a 100 nm membrane filter (Whatman, NJ) at 60-62 °C on a heating block, to form 100 nm liposomes. The liposome solution was stored at 4 °C until needed for radiolabeling.

64Cu labeling of BAT-PEG-lipids

BAT-PEG-lipids (20 μg, 7.5 nmol) in chloroform (20 μL) were added into a glass test tube and chloroform was evaporated by gently blowing nitrogen gas with vortexing. After overnight under high vacuum, citrate buffer (0.1 M, 0.4 mL, pH 5.5) was added to the glass test tube containing BAT-PET-lipids. Buffered 64CuCl2 (5.31 mCi, 196.47 MBq) in ammonium citrate (pH 5.5, 0.1 M) was added to the lipid solution, which was transferred to a plastic tube. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C and monitored by radio TLC (eluant: chloroform:ethanol:H2O = 50:40:60, v/v/v), which showed 97% labeling yield after 40 min incubation. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was passed through an activated C-18 sep-pak cartridge and washed with deionized water (5 mL) and anhydrous acetonitrile (8 mL). Radioactivity remaining in the cartridge was extracted by mixed ethanol and chloroform solution (1 mL, 1:1, v/v). After the solution was removed under a nitrogen stream, the activity was re-suspended with 7% ethanol/PBS for the in vivo study. Radiochemical yield at the end of synthesis (EOS) was 59% and specific activity was greater than 575 Ci/mmol. Radiochemical purity on both radio TLC and reversed-phase HPLC was 99% (C4 column, 250 × 4.6 mm, analytical, solvent A: 0.05 volume% trifluoroacetic acid in deionized water, solvent B: acetonitrile, flow rate: 1.5 mL/min, gradient from 10-90% B in 30 min and 90-10% B in 30-60 min, retention time: 29.6 min).

64Cu labeling of liposomes

For the feasibility study

64CuCl2 (8.31 mCi, 307.47 MBq) in a volume of 35 μL (pH 1-2) was received and NH4OAc solution (4 μL, 1 M, pH 5.0) was added to adjust the pH. This solution (5.08 mCi, 187.96 MBq, 25 μL) was added to 475 μL of 0.1 M NH4OAc solution (pH 5.0) and the final concentration of 64Cu was 10 mCi/mL. This 64Cu solution (50 μL) was added to the liposome solutions (12 mg/300 μL, total lipid mol = 12.7 μmol, DPPC:DSPE-PEG2000:BAT-PEG-lipid = 90-x:10.0:x, mol/mol/mol, x = 0, 0.1, and 1.0). The concentration of BAT-PEG-lipids in 12 mg of lipids was 0, 12.7, and 127 nmol, respectively. After vortexing, the mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, EDTA solution (0.1 M, 35 μL) was added (final EDTA concentration 10 mM) and the mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Liposomes were separated by a G-75 column (GE Healthcare, NJ) in PBS, and fractions were collected in 250 μL tubes. The radioactivity was measured with a calibrated Cu-64 mode of CRC-15 DualPET (Capintec, NJ) with non-correction of Cu-67, and the incorporation yield was determined by equation (1) as decay corrected yield.

| (1) |

(Fl: radioactivity in liposome fractions, Fa: sum of all radioactive fractions)

For the in vitro study

liposomes (10 mg) containing 0.5 mol% of BAT-PEG-lipid (HSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000: BAT-PEG-lipid = 55.5:39:5.0:0.5, mol/mol/mol/mol, the number of BAT-PEG-lipids: 68.7 nmol) and without BAT-PEG-lipid (HSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG200 = 56:39:5.0, mol/mol/mol) were prepared by the procedure above. Both liposome formulations were incubated with 64CuCl2 (2.15 mCi) at 35 °C for 40 min. The purification continued as above and the labeling yield was determined by equation (1).

For the in vivo study

>Liposomes (1 mg, HSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000: BAT-PEG-lipid = 55.5:39:5.0:0.5, mol/mol/mol/mol, the number of BAT-PEG-lipid: 6.85 nmol) were prepared by the procedure above. 64CuCl2 (2.75 mCi) solution was added to 300 μL (0.1 M NH4OAc, pH 5) of BAT-liposome solution and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min. Purification continued as above. After the radioactivity decayed, size and zeta potential were measured with a NICOMPTM 380 ZLS (Particle Sizing Systems, CA).

In vitro stability test

Separated 64Cu-labeled liposomes (~ 1.0 mg lipids) in PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 0.5 mL) were added to 0.5 mL of mouse serum and albumin solution (final concentration: 8 mg/mL). The mixture was kept in a shaker (300 rpm) at 37 °C , a sample of 100 μL was taken from the solution at 48 hours and hand-loaded onto a sephachryl-300HR (GE Healthcare, NJ) packed column (15 mm I.D, 250 mm height), which was eluted with PBS under a pressure of 2 psi. Fractions (1.5 mL per fraction) were collected into test tubes, and radioactivity was measured with the 1470 Automatic Gamma Counter (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, MA). After the radioactive decay, the absorbance of all fractions was measured at 280 nm. Radio TLC assay: Each aliquot (10 μL) of six solutions described below was dissolved into 50% ethanol solution (100 μL) after 20 and 48 hour incubation at room temperature: 64CuCl2 in 0.1 M NH4OAc solution, 64CuCl2 in serum solution (PBS:serum = 1:1, v/v), 64CuCl2 in albumin solution, 64Cu-labeled liposomes in PBS buffer, 64Cu-labeled liposomes in albumin solution and 64Cu-labeled liposomes in serum solution (PBS:serum = 1:1, v/v). TLC was run on aluminum-backed silica gel sheets (silica gel 60 F254, EMD, NJ), developed with chloroform:methanol:H2O (50:40:6, v/v/v). The radio TLC was recorded by a radio-TLC Imaging Scanner (Bioscan, NW).

Biodistribution study

All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of California, Davis Animal Use and Care Committee. A total of 10 animals (male FVB mice, 8-13 weeks, 25-30 g, Charles River, MA) were examined over the course of this study. For each image, four or three mice per group were anesthetized with 3.5% isofluorane and maintained at 2.0–2.5% and catheterized to ensure proper tail vein injection, after which bolus injections of 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipids (0.263 ± 0.013 mCi (9.73 ± 0.48 MBq) per animal), 64Cu-labeled liposomes (4.6-18 μmol/kg, 0.17-0.21 mCi (6.29-7.77 MBq) per animal) and 64CuCl2 (carrier free, 0.15-0.4 mCi (5.55-14.7 MBq)) in PBS (pH 7.2) were administered as PET scans were initiated, using a manually-controlled injection that was timed for uniform administration over 15 seconds. After the 48-h PET scans, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and organs of interest were harvested and weighed. Radioactivity was measured using a 1470 Automatic Gamma Counter.

PET scans and Time–activity curves (TAC)

PET scans were conducted with the microPET Focus (Concorde Microsystems, Inc., TN) over 60 minutes. Maximum a posteriori (MAP) files were created with ASIPro software (CTI Molecular Imaging) and used to obtain quantitative activity levels in each organ of interest as a function of time. TACs were obtained with region-of-interest (ROI) analysis using ASIPro software and expressed as percentage of injected dose per cubic centimeter (%ID/cc).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Fmoc solid phase synthesis was used to create the lipid-PEG-chelate conjugate to minimize hydrolysis of the ester group in the lipid conjugate and maximize purity of the final conjugate (7 in Scheme 1) (32). A short PEG spacer (28 repeat units, MW ~ 1232) was introduced to facilitate accessibility of 64Cu to the chelator by minimizing the steric effect of neighboring lipid head groups, while burying the chelator within the longer PEG brush (45 repeat units, MW ~ 1980) of the surrounding lipid molecules. In brief, Fmoc-Cys(Mmt)-OH, Fmoc-PEG28-COOH, Fmoc-Lys(Fmoc)-OH and stearic acid were coupled to the PAL-PEG-PS resin sequentially, to obtain 5 in scheme 1. After the protecting group, Mmt, was removed with 1% TFA/DCM, BAT was coupled to the resin in the mixture solvent (DMF:DMSO:H2O = 1:1:1, v/v/v), at pH = 8.0 ± 0.5, adjusted with DIPEA. The reaction was monitored with DTNP solution. The final product (7 in scheme 1) was cleaved from the resin by a TFA/TIPS/H2O mixture (TFA:TIPS:H2O = 95:2.5:2.5, v/v/v) and purified by HPLC, with the mass confirmed by MALDI (M+H+, measured: 2662, calculated: 2663, Figure 2).

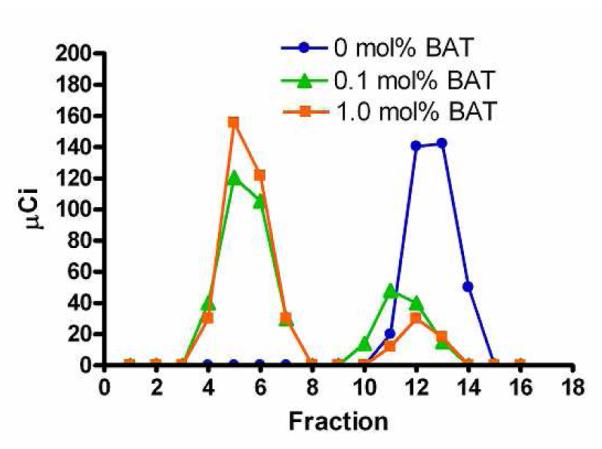

To check the feasibility of chelating 64Cu onto BAT liposomes, the chelation yields were compared for three temperature sensitive liposome formulations (33, 34), with 0, 0.1, and 1.0 mol% BAT-PEG-lipid, respectively (Figure 3). Similar to the labeling protocol developed for antibodies (25), chelation of 64Cu onto liposomes was performed in 0.1 M NH4OAc pH 5 buffer at room temperature for 60 min. Unchelated 64Cu was removed by mixing the liposome solution with 1/10 (v/v) 0.1 M EDTA solution for 20 min. 64Cu-labeled liposomes and 64Cu-EDTA complexes were separated with a Sephadex-G75 column with the normalized radioactivity of each fraction shown in Figure 3. The 64Cu chelation yields for 0, 0.1, and 1.0 mol% BAT liposomes were 0%, 83%, and 89%, respectively. Specific activity of the chelator was determined as 29.1 μCi (0.1 mol%) and 31.3 μCi (1.0 mol%) per 1 mg of total lipids and as 27.5 and 2.96 Ci per 1 mmol BAT-PEG-lipids. The number of BAT-PEG-lipid molecules in the 0.1 mol% BAT liposomes was 11 times more than the molecules of added 64CuCl2 (0.42 mCi).

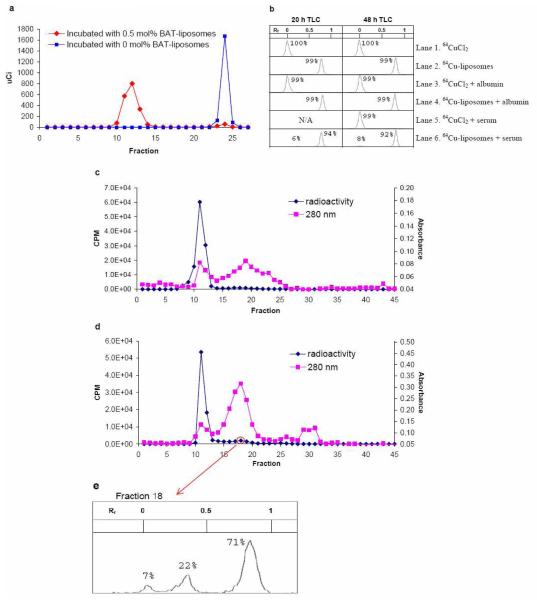

Figure 3.

Elution profiles of 64Cu-labeled liposomes after incubation with 64CuCl2 for 1 hour and EDTA for 20 min at room temperature in 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). The molar ratios of lipid-PEG-BAT are: 0 mol% (circle), 0.1 mol% (triangle) and 1.0 mol% (square), and are combined with 90 % DPPC and 10% DSPE-PEG2000 (mol/mol).

To demonstrate that this technique can successfully label multiple liposomal formulations and to demonstrate stability over 48 hours, in vitro and in vivo assays were performed with long circulating liposomes (35). The in vitro stability of 64Cu-labeled liposomes was also tested with 0.5 mol% BAT-PEG-lipids in a non-temperature sensitive formulation. Incubation of both liposomes with 64CuCl2 at 35 °C for 45 min, followed by treatment with EDTA solution for 15 min, gave an estimated 95% labeling yield with 0.5 mol% BAT liposomes (Figure 4a). Specific activity was measured as 0.194 mCi per 1 mg of total lipids or 28.2 Ci per 1 mmol BAT-PEG-lipids.

Figure 4.

In vitro assay of 64Cu-labeled liposomes: a) Elution profiles of liposomes with 0.5 mol% BAT-PEG-lipid (HSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000:BAT-PEG-lipid = 55.5:39:5.0:0.5, mol/mol/mol/mol, red diamond) and 0 mol% BAT-PEG-lipid (HSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000 = 56:39:5.0:0.5, mol/mol/mol, blue square) after incubation with 64CuCl2 for 40 min and EDTA for 15 min at 35 °C in 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Liposomes were separated by a size exclusion column. With 0.5 mol% BAT-PEG-lipid, 64Cu was associated with liposomes; without BAT-PEG-lipid 64Cu was not detected in the liposomal fraction. b) Radio TLC on silica plate was developed with eluant (chloroform:methanol:H2O = 50:40:6, vol/vol/vol). Retention factor (Rf) of 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid was 0.8 and that of 64CuCl2 was 0. Lanes 1-6 were measured at 20 and 48 hours as indicated in figure 3b. c) Chromatogram of the mixture of 64Cu-liposomes and albumin (8 mg/mL) in PBS after 48 h incubation at 37 °C. The mixture was separated by a size exclusion column Elution of liposomes and serum proteins was measured by gamma-counter (diamonds) and UV absorbance at 280 nm (squares). d) Chromatogram of the mixture of 64Cu-liposomes and serum in PBS (PBS:serum = 1:1, vol/vol) after 48 h incubation at 37 °C. e) Radio TLC of fraction 18 performed as in b). The peak (Rf 0.8) represents 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid. Small peak near 0 indicates free 64Cu and middle peak has not been characterized.

64Cu was not detected on liposomes lacking the BAT-lipid. Labeled liposomes in PBS (pH 7.4) were mixed with albumin (10 mg/mL) and mouse serum (PBS:serum = 1:1, v:v). Mixtures were allowed to stand at 37 °C and the stability was monitored by radio TLC (Figure 4b) and chromatography with a size exclusion column (Figure 4c-d). As shown in the TLC study (Figure 4b), radioactivity in the form of 64CuCl2 (lane 1), 64CuCl2 associated with albumin (lane 3) and 64CuCl2 associated with serum (lane 5) were retained at the origin. However, the relatively lipophilic 64Cu-liposomes (lane 2) (64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid on silica plate), shifted to Rf 0.8, including 99% of the radioactivity. 64Cu-liposomes incubated with albumin (lane 4) for 48 hours also showed 99% of the radioactivity in the Rf 0.8 region. This suggests that 64Cu-liposomes are inert to albumin. With 64Cu-liposomes incubated with mouse serum, 6% and 8% of the activity was found in Rf 0.0 after 20 and 48 hour incubation, respectively. The chemical form of the copper was not investigated further.

To further characterize the effect of serum on chelation stability, an analysis was performed using size exclusion chromatography, with aliquots of solution loaded into the size exclusion column after incubation with albumin and serum for 1 and 48 hours. The radioactivity was measured with a gamma-counter and absorbance of the serum component read at 280 nm. The size exclusion chromatogram of radioactivity from the albumin mixture (Figure 4c) showed that fractions (f1-30) contain more than 99% of the total radioactivity. Liposome fractions in the main peak (f7-15) and minor broad peak (f16-22) contained 95% and 4.1% of the total radioactivity, respectively. Thus, the labeled liposomes (radioactivity) and albumin (280 nm) could be separated and albumin, the major component of serum, did not affect the stability of the labeled liposomes.

Size exclusion chromatography (Figure 4d) following serum incubation also showed that fractions (f1-30) contain more than 99% of the total radioactivity. As shown in Figure 4d, three peaks, with fractions f9-15, f16-22, and f23-30, were found to have 88%, 9.1%, and 2.7% of the radioactivity, respectively. To elucidate whether the second peak (f16-22) contains 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid or dissociated 64Cu, radio TLC of one fraction was performed. TLC showed three peaks (Figure 4e) corresponding to Rf equal to 0 (7%), 0.35 (22%) and 0.8 (71%). If the result is compared with lane 2 in Figure 4b, the major peak (Rf of 0.8) corresponds with the 64Cu-liposomes. Radioactivity after the 14th fraction in Figure 4d is assumed to represent 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipids which associated with serum during incubation. Therefore, we estimate that more than 88% of the 64Cu remained associated with the liposomes after 48 h in serum. Prior work with 67Cu-antibodies labeled using BAT showed a dissociation of copper from the chelator of approximately 1% per day under physiological conditions in serum (25). The properties of liposomes, including possible exchange of lipids with other serum components, make it difficult to specifically measure the rate of copper dissociation for the system studied here.

The in vivo performance of 64Cu-labeled liposomes was studied, with the in vivo results compared with previously reported 99mTc-labeled liposome studies (14, 36). Liposomes with 0.5 mol% BAT-PEG-lipid were labeled with 64CuCl2 (3.0~4.0 mCi/mg lipids) at 37 °C for 40 min. The labeling yield was 62 ± 13% (n = 2) and the specific activity was 1.65 ± 0.29 (n = 2) mCi per 1 mg of total lipids or 242 ± 42 (n = 2) Ci per 1 mmol BAT-PEG-lipids. The size and zeta potential of liposomes before and after labeling are listed in Table 1. The liposomes were reduced in size by about 10 nm after labeling, likely due to a difference in osmolarity before (0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer, ~ 240 mOsm, pH 5.0) and after labeling (10 mM PBS buffer, ~ 300 mOsm, pH 7.4). Zeta potential was not significantly changed before (−40.8 mV) and after (−41.2 mV) labeling.

Table 1.

Size (nm) and Zeta potential (mV) of 0.5 mol% BAT-liposomes (n = 2).

| Liposome | Size (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | after | before | after | |

| BAT-liposome | 108.8 ± 5.5 | 97.2 ± 3.5 | -40.8 ± 4.3 | -41.2 ± 3.2 |

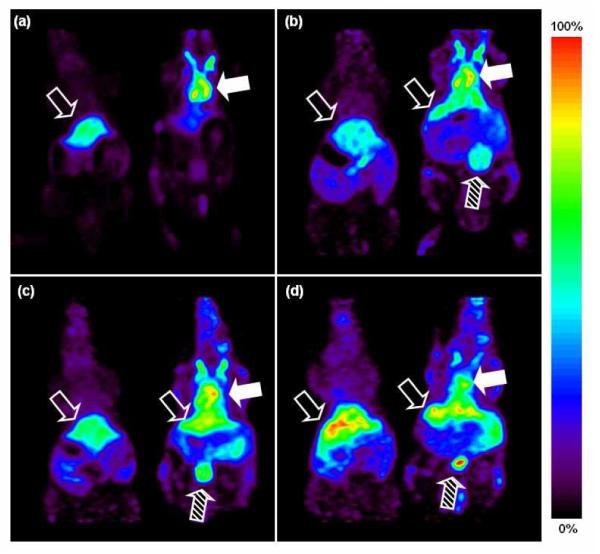

In vivo imaging with 64Cu-labeled liposomes was then performed in FVB mice with microPET and compared with free 64Cu (64CuCl2). All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of California, Davis Animal Use and Care Committee (Davis, CA). Figure 5 shows four images from 30-min scans at 0, 18, 28, 48 h after i.v. injection, for both a free 64Cu injection (left) and a liposomal 64Cu injection (right). Free 64Cu rapidly accumulated in the liver (Figure 5a-d) and accumulation was highest in the liver throughout the scan as in (37). In contrast, liposomal 64Cu remained in the blood pool (Figure 5a-d) through 18, 28, and 48 h. Uptake of the liposomes by the reticulo-endothelial system is expected with previous SPECT studies showing similar accumulation to that observed here (14). The accumulation of 64Cu in the liver and other organs can result from intracellular processes via metabolism of liposomes (38) and transchelation of 64Cu to ceruloplasmin (26), superoxide dismutase (SOD) (38, 39), or copper chaperone for SOD (40); however, comparing our results with previous liposomal SPECT studies using Tc-99m, these effects do not appear to be substantial.

Figure 5.

Coronal view of microPET image with two mice (left: 64CuCl2 injected, right: 64Cu-liposomes) at four time points ((a) 0, (b) 18, (c) 28, (d) 48 hrs after i.v. injection). Relative scale (the brightest spot is maximum) was applied for images. Filled arrow indicates blood pool, striped arrow indicates bladder, and unfilled arrow indicates liver.

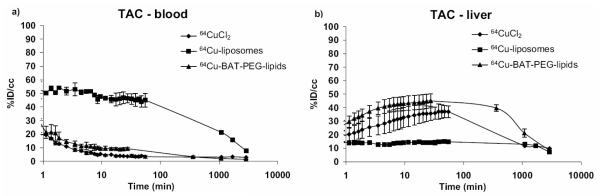

Time activity curves (TAC) corresponding to blood and liver are shown in Figure 6. Decay-corrected radioactivity in the blood pool decreased to 44 ± 6.9, 21 ± 2.7, 15 ± 2.5, and 7.4 ± 1.1 (n = 4) %ID/cc at 30 min, 18, 28, and 48 h, respectively (Figure 6). To compare our TAC data with (14) , the maximum %ID/cc (50 ± 8.9) at 2 min was fixed as the initial blood pool activity and the TAC estimates at 30 min, 18, 28, and 48 h were converted to 88%, 42%, 30%, and 15% of the original radioactivity in the blood pool. These values are similar to those observed by Laverman in a study of rats with 99mTc-HYNIC liposomes, which showed 40% of the initial blood-pool radioactivity remaining at 24 hours (14). Similarly, 38% of initial activity was retained in the blood pool at 20 hours following injection of labeled liposomes into rats in (36). A solution of 64Cu-BAT-PET-lipid (specific activity: 575 Ci/mmol) was also injected into the mouse tail vein (n = 3). As a result, radioactivity accumulated in the liver within 30 min and cleared in a manner similar to the injected 64CuCl2 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Time activity curves in blood and liver of mice (n = 3~4 per group) after bolus injections of 64CuCl2, 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid, and 64Cu-labeled liposomes. TACs for heart and liver (a and b) were obtained from microPET in each organ of interest as a function of time by drawing regions of interest (ROI).

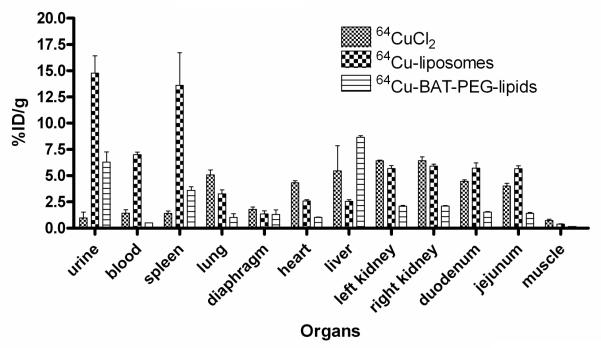

The biodistribution at 48 hours shows that activity in the urine, blood, and spleen of liposomal 64Cu was significantly higher than that of free 64Cu or 64Cu-BAT-PET-lipid (Figure 7). Subsequent studies have indicated that the activity within the spleen is dependent on the lipid dose injected, decreasing with larger amounts of lipid (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Biodistribution of liposomal 64Cu (n = 4), 64Cu-BAT-PEG-lipid (n = 3), and free 64Cu (n = 3) in mice at 48 hours after injection.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a novel 64Cu labeling method for liposomes. By solid phase synthesis, a BAT-PEG-lipid conjugate was prepared, and by incorporating BAT-PEG-lipid into liposomes and incubating the resulting liposomes with 64CuCl2, 64Cu liposomes were obtained with a labeling yield as high as 95%. The liposomal 64Cu was stable in mouse serum in vitro and was long-circulating in vivo. These results suggest that this novel labeling method (64Cu-BAT-liposomes) can be further exploited for tracking liposomes with PET in vivo.

Acknowledgement

The staff in the CMGI (Center forMolecular and Genomic Imaging, UC Davis) for handling 64Cu and imaging studies are gratefully acknowledged. The support of NIH CA 103828 is appreciated.

1 Abbreviations

- BAT

6-[p-(bromoacetamido)benzyl]-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid

- BMEDA

N,N-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-N’,N”-diethylethylenediamine

- Cys

cysteine

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid

- NOTA

1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N’,N”-triacetic acid

- DPPC

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DSPE-PEG-2000

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000]

- DTNP

2,2′-dithio bis-(5-nitropyridine)

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- HSPC

hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine

- HYNIC

hydrazino nicotinamide

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- Mmt

4-monomethoxytrityl

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ROI

region of interest

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- TAC

time activity curve

- TETA

1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIPS

triisopropylsilane

References

- (1).Janoff AS. Liposomes : rational design. M. Dekker; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gregoriadis G. Liposome technology. 3rd ed Informa Healthcare; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006;1:297–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Harrington KJ, Rowlinson-Busza G, Syrigos KN, Uster PS, Vile RG, Stewart JS. Pegylated liposomes have potential as vehicles for intratumoral and subcutaneous drug delivery. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2528–2537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Phillips WT, Rudolph AS, Goins B, Timmons JH, Klipper R, Blumhardt R. A simple method for producing a technetium-99m-labeled liposome which is stable in vivo. Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. B. 1992;19:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(92)90149-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Awasthi VD, Garcia D, Klipper R, Goins BA, Phillips WT. Neutral and anionic liposome-encapsulated hemoglobin: effect of postinserted poly(ethylene glycol)-distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine on distribution and circulation kinetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;309:241–248. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bao A, Goins B, Klipper R, Negrete G, Mahindaratne M, Phillips WT. A novel liposome radiolabeling method using 99mTc-“SNS/S” complexes: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;92:1893–1904. doi: 10.1002/jps.10441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gabizon A, Papahadjopoulos D. Liposome formulations with prolonged circulation time in blood and enhanced uptake by tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:6949–6953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Marik J, Tartis MS, Zhang H, Fung JY, Kheirolomoom A, Sutcliffe JL, Ferrara KW. Long-circulating liposomes radiolabeled with [18F]fluorodipalmitin ([18F]FDP) Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Urakami T, Akai S, Katayama Y, Harada N, Tsukada H, Oku N. Novel amphiphilic probes for [18F]-radiolabeling preformed liposomes and determination of liposomal trafficking by positron emission tomography. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6454–6457. doi: 10.1021/jm7010518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Corvo ML, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, Van Bloois L, Cruz ME, Crommelin DJ, Storm G. Intravenous administration of superoxide dismutase entrapped in long circulating liposomes. II. In vivo fate in a rat model of adjuvant arthritis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1419:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ogihara-Umeda I, Kojima S. Increased delivery of gallium-67 to tumors using serumstable liposomes. J. Nucl. Med. 1988;29:516–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Oku N, Tokudome Y, Tsukada H, Okada S. Real-time analysis of liposomal trafficking in tumor-bearing mice by use of positron emission tomography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1238:86–90. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00106-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Laverman P, Dams ET, Oyen WJ, Storm G, Koenders EB, Prevost R, van der Meer JW, Corstens FH, Boerman OC. A novel method to label liposomes with 99mTc by the hydrazino nicotinyl derivative. J. Nucl. Med. 1999;40:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hnatowich DJ, Friedman B, Clancy B, Novak M. Labeling of preformed liposomes with Ga-67 and Tc-99m by chelation. J. Nucl. Med. 1981;22:810–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rahmim A. PET vs. SPECT: in the Context of Ongoing Developments. Iran. J. Nucl. Med. 2006;14:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Mazzola L, Torchilin VP. Polyethylene glycol-diacyllipid micelles demonstrate increased acculumation in subcutaneous tumors in mice. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:1424–1429. doi: 10.1023/a:1020488012264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Medina OP, Zhu Y, Kairemo K. Targeted liposomal drug delivery in cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004;10:2981–2989. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ponce AM, Vujaskovic Z, Yuan F, Needham D, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia mediated liposomal drug delivery. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 2006;22:205–213. doi: 10.1080/02656730600582956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Tilcock C, Ahkong QF, Fisher D. 99mTc-labeling of lipid vesicles containing the lipophilic chelator PE-DTTA: effect of tin-to-chelate ratio, chelate content and surface polymer on labeling efficiency and biodistribution behavior. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1994;21:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ahkong QF, Tilcock C. Attachment of 99mTc to lipid vesicles containing the lipophilic chelate dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine-DTTA. Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. B. 1992;19:831–840. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(92)90169-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Smith SV. Molecular imaging with copper-64. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2004;98:1874–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Copper chelation chemistry and its role in copper radiopharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007;13:3–16. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Moran JK, Greiner DP, Meares CF. Improved synthesis of 6-[p-(bromoacetamido)benzyl]-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane- N,N’,N”,N”’-tetraacetic acid and development of a thin-layer assay for thiol-reactive bifunctional chelating agents. Bioconjug. Chem. 1995;6:296–301. doi: 10.1021/bc00033a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kukis DL, Diril H, Greiner DP, DeNardo SJ, DeNardo GL, Salako QA, Meares CF. A comparative study of copper-67 radiolabeling and kinetic stabilities of antibody-macrocycle chelate conjugates. Cancer. 1994;73(Suppl S):779–786. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3+<779::aid-cncr2820731306>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mirick GR, O’Donnell RT, DeNardo SJ, Shen S, Meares CF, DeNardo GL. Transfer of copper from a chelated 67Cu-antibody conjugate to ceruloplasmin in lymphoma patients. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1999;26:841–845. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kukis DL, Li M, Meares CF. Selectivity of antibody-chelate conjugates for binding copper in the presence of competing metals. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:3981–3982. [Google Scholar]

- (28).McCall MJ, Diril H, Meares CF. Simplified method for conjugating macrocyclic bifunctional chelating agents to antibodies via 2-iminothiolane. Bioconjug. Chem. 1990;1:222–226. doi: 10.1021/bc00003a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kukis DL, DeNardo GL, DeNardo SJ, Mirick GR, Miers LA, Greiner DP, Meares CF. Effect of the extent of chelate substitution on the immunoreactivity and biodistribution of 2IT-BAT-Lym-1 immunoconjugates. Cancer Res. 1995;55:878–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Boswell CA, Sun X, Niu W, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Rheingold AL, Anderson CJ. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1465–1474. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Keller BO, Li L. Three-layer matrix/sample preparation method for MALDI MS analysis of low nanomolar protein samples. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2006;17:780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Chan WC, White PD. Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis : a practical approach. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Anyarambhatla GR, Needham D. Enhancement of the phase transition permeability of DPPC liposomes by incorporation of MPPC: A new temperature-sensitive liposome for use with mild hyperthermia. J. Liposome Res. 1999;9:491–506. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hossann M, Wiggenhorn M, Schwerdt A, Wachholz K, Teichert N, Eibl H, Issels RD, Lindner LH. In vitro stability and content release properties of phosphatidylglyceroglycerol containing thermosensitive liposomes. Biochim.Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2491–2499. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–436. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Bao A, Goins B, Klipper R, Negrete G, Phillips WT. Direct 99mTc labeling of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) for pharmacokinetic and non-invasive imaging studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;308:419–425. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Owen CA., Jr. Metabolism of radiocopper (Cu64) in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1965;209:900–904. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.209.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rogers BE, Anderson CJ, Connett JM, Guo LW, Edwards WB, Sherman EL, Zinn KR, Welch MJ. Comparison of four bifunctional chelates for radiolabeling monoclonal antibodies with copper radioisotopes: biodistribution and metabolism. Bioconjug. Chem. 1996;7:511–522. doi: 10.1021/bc9600372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bass LA, Wang M, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. In vivo transchelation of copper-64 from TETA-octreotide to superoxide dismutase in rat liver. Bioconjug. Chem. 2000;11:527–532. doi: 10.1021/bc990167l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wong PC, Waggoner D, Subramaniam JR, Tessarollo L, Bartnikas TB, Culotta VC, Price DL, Rothstein J, Gitlin JD. Copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase is essential to activate mammalian Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:2886–2891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040461197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]