Abstract

This study describes a method for using teacher nominations and ratings to identify socially influential, aggressive middle school students for participation in a targeted violence prevention intervention. The teacher nomination method is compared with peer nominations of aggression and influence to obtain validity evidence. Participants were urban, predominantly African American and Latino sixth-grade students who were involved in a pilot study for a large multi-site violence prevention project. Convergent validity was suggested by the high correlation of teacher ratings of peer influence and peer nominations of social influence. The teacher ratings of influence demonstrated acceptable sensitivity and specificity when predicting peer nominations of influence among the most aggressive children. Results are discussed m terms of the application of teacher nominations and ratings in large trials and full implementation of targeted prevention programs.

Keywords: selective interventions, teacher ratings, halo effects, ecological risk

An important issue in violence prevention research is the identification of high-risk children to participate in targeted programs (August et al., 1995; Lochman & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group [CPPRG], 1995). Targeted or indicated programs focus on high-risk children who already demonstrate some symptoms or signs of problems (Coie et al., 1993; Institute of Medicine, 1994). Extending the concept of risk from the individual level to the school level of analysis, the extent to which aggressive children are able to influence others becomes, along with individual aggression, a marker for risk (Henry et al., in press). In this paper, our interest was in determining how well teachers could select students whom other students saw as influential from among the most aggressive youth.

There are a number of challenges in the design of effective procedures to select high-risk children. One is to have selection procedures that are based on developmentally appropriate factors that constitute risk. Another is to have selection procedures that are relevant to the particular context in which screening procedures take place. Screening procedures usually take place in the school setting, most typically in elementary schools. Although, there have been studies of selection procedures with elementary school children (e.g., Huesmann et al., 1994; Lochman & CPPRG, 1995), there has been only limited study of selection procedures targeting middle-school-age adolescents. The purpose of this paper is to describe and validate a method to identify middle school students at high risk for aggression who are influential among their peers.

An important first step in choosing youth for a targeted intervention is to identify developmentally appropriate risk factors, and to then develop selection procedures based on these risk factors (Coie et al., 1993; Lochman & CPPRG, 1995). Typically, selection procedures have used ratings of aggressive problems to select high-risk children (e.g., August et al., 1995; Casat et al., 1999; Huesmann (et al., 1997; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group, 2002), The current study builds on this work by focusing on, an additional characteristic of a subset of aggressive youth that could influence school-levels of aggression, namely, the degree to which youth are influential among their peers.

Early adolescence is a critical developmental transition, and such developmental transitions represent important windows of opportunity to alter risk factors and related processes (Coie & Jacobs, 1993; Reid & Eddy, 1997). Strategies to select high-risk youth should be sensitive to shifts in risk factors during these key transitions. The entry to middle school brings with it important changes in individual and contextual risk factors that impact risk-taking behaviors. Thus, procedures to select high-risk students should take into account developmentally sensitive risk processes that are relevant to the middle school transition.

One of the most important developmental shifts in risk processes that occurs in early adolescence is the increasing importance of peer influences on risk-taking behaviors (Coie & Jacobs, 1993; Miller-Johnson & Costanzo, in press). As children transition into adolescence, parental influences decrease as peers become increasingly important socializing agents (Dishion et al., 1994), There are also developmental changes in links between peer acceptance and aggressive and other problem behaviors. Whereas problem-prone elementary school age children are typically rejected by their peers, by middle school, being aggressive may actually enhance social status (Coie et al., 1992; Luthar, 1997). Aggression may be particularly status-enhancing in distressed urban settings (Coie & Jacobs, 1993; Guerra, 1998). Those youth who are both, well liked by their peers and involved in problem behaviors are viewed as being leaders in an unconventional, “anti-establishment” sense and are highly influential among their peers. In settings where aggressive students are popular among peers, the process of social mimicry might result in increased levels of aggression among students who would not normally have behaved aggressively (Moffitt, 1993). Therefore, those early adolescents who influence other teens or are mimicked by others may be critical instigators of risk-taking behavior among other youth, in addition to displaying high levels of problem behavior themselves (Miller-Johnson et al. in press). This “deviancy training” can take the form of talking, bragging, and boasting about aggressive and delinquent behaviors (Dishion et al., 1996). Moreover, a small group of the most seriously aggressive children in a school commit most of the aggressive and violent behaviors. Thus, by targeting students who are both highly aggressive and influential among their peers, prevention programs can have two important effects Smith et al. (in press). First, by lowering rates of violence among these students who committed the majority of problem behaviors, there would be direct effects on the overall school rates of aggression. Second, because these high-risk, influential children have a substantial impact on the learning, adoption, and perpetuation of aggressive and violent behavior by their peers, successful intervention efforts with these students may produce indirect effects on other students. Therefore, it is critical that we have a valid and practical method for identifying students who are both aggressive and influential.

A more practical issue facing screening procedures in middle school settings is determining who will identify high-risk students. Because of the size and departmental structure of many middle schools, we reasoned that core teachers who see students on a regular basis would be in the best position to provide nominations and ratings that could be used in selecting influential and aggressive students for intervention participation. We reached this conclusion after considering several issues arguing for and against the use of teacher information for this purpose. First, although teacher ratings are often used to select aggressive students for interventions, sociometric ratings by peers are the preferred method to assess social behaviors such as peer influences (Huesmann et al., 1994). Second, collection of sociometric data can be challenging in middle schools due to the need for assessments to include the names of all potential peer nominees, and the need for children providing nominations to know all of the other nominees. (Zakriski et al., 1999). Third, teacher ratings tend to show halo effects (Schachar et al., 1986).

We reasoned that, even in large middle schools, it would be possible to identify core teachers who have sufficient opportunity to observe students interacting with peers to provide valid ratings. In the current study, we used teacher ratings of both aggression and peer influence to identify high-risk students. Teacher ratings have been shown to be valid for assessing risk for aggression among middle school as well as elementary school students (Achenbach, 1991; Huesmann et al., 1997), and to show convergence with peer nominations of aggression (r’s = .69 – .79; Huesmann et al., 1994). In addition, there is some preliminary evidence to suggest that teachers may be accurate raters of peer social structure. For example, Yugar and Shapiro (2001) compared different methods of assessing social networks and found that teacher social network methods were as accurate as peer nominations in identifying a child’s best friend (~72% accuracy). However, the validity of teacher ratings for assessing peer influence has not been investigated. Thus, a second goal of this study was to validate teacher ratings of peer influence and aggression.

In summary, the present study was undertaken to evaluate a method for identifying high-risk, students using teacher ratings of aggression and influence among peers. Our first objective was to evaluate the discriminant validity of our measures of influence among peers. Specifically, we examined the extent to which peer and teacher ratings of peer influence tapped aspects of youth’s social behavior that were distinct from other measures, such as popularity among peers or rejection by peers. The second objective was to evaluate the convergent validity of teacher ratings of peer influence by comparing them with peer ratings. Third, we wanted to determine the accuracy with which teacher ratings could identify a group of socially influential students within the subpopulation of the most aggressive students. Finally, we wanted to determine the extent to which the selection procedure, using teacher nominations, would select students who were both aggressive and influential according to peer nominations.

METHOD

Participants

This study was conducted as a part of the pilot study for the Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project (MVPP Henry et al., in press; Miller-Johnson et al., in press). This is a large-scale evaluation of the Guiding Responsibility and Expectations in Adolescents Today and Tomorrow (GREAT) violence prevention program for middle school students. This 2 × 2 experiment examines the effects of a universal intervention (i.e., classroom curricula and teacher training; Meyer et al., in press; Orpinas et al., in press and a targeted intervention, i.e., multifamily groups for high-risk youth; Smith et al. (in press), singly and in combination, on aggressive and violent behavior.

We pilot tested the procedure for selecting targeted youth in one of the four sites participating in the MVPP. The site chosen involved a school district serving inner-city areas of a major midwestern city. This site was suited to this pilot study because its relatively small schools (approximately 60 sixth-grade children in each) made the process of obtaining permission and administering sociometric measures more feasible than would have been the case in the other three sites (as many as 400 sixth-graders per school). In addition, these schools had only limited departmental structure for sixth graders, meaning that groups of students remained together throughout most of the day. The pilot study in this site was conducted in four sixth grade classrooms at two schools. Data reported here were collected prior to the implementation of intervention programs.

The sample consisted of 124 male and female students from four sixth-grade classes (n’s = 27, 30, 33, and 34) in two urban schools. The sixth grade in those schools served approximately equal numbers of male (51.6%) and female (48.4%) students. Approximately two thirds of the sixth grade (67.2%) reported African American ethnicity, 35.9% reported Latino, and 7.8% reported non-Hispanic White ethnic identification. Student assent and parent consent for providing nominations were obtained from 63 students (51% of the potential sample). The number of nominators in each classroom ranged from a low of 14 (39.9%) to a high of 22 (73.3%). The remaining students in each classroom did not return parental permission forms after multiple attempts. All four sixth-grade homeroom teachers, two from each school, also consented to participate in this research

Measures

Aggression

We collected validity data for the teacher nomination procedure by having the consented students complete ratings of their peers. Peer ratings were collected using the Peer Nominations of Aggression (Eron et al., 1971). The peer nomination procedure presented each child with a list of all boys and girls in his or her classroom, with the names grouped by gender. The child was asked to cross off every name that fits the question asked by the assessor (e.g., “Who pushes and shoves other children?,” “Who gets into fights a lot?”). There were no limits on the number of nominations students could make in order to increase the stability of the measurement. Each child’s score on the peer nominations was the ratio of the number of nominations to the number of nominators, averaged across scale items. This measure has been used for over 30 years with demonstrated reliability and validity in several cultures (Eron & Huesmann, 1987; Huesmann & Eron, 1992). In this study, the 10-item aggression scale had an internal consistency by Cronbach’s α of .96.

The teacher nomination procedure for aggression asked teachers to nominate up to 25% of the students in their classes. Teachers were given the following list of aggressive behaviors to guide them in nominating the most aggressive 25% of their students; 1) encourages other students to fight; 2) frequently intimidates other students; 3) has a short fuse, gets angry very easily; and 4) gets into frequent physical fights.

Influence Among Peers

Ratings of peer influence were similarly obtained from peers and teachers. For peer ratings, students nominated those classmates who fit each of the following peer influence descriptors: 1) “Which students have a lot of friends?” 2) “Who are the students that other students try to be like?” 3) “Who are the students whom other students listen to?” 4) “Who are the students other students respect?” 5) “Who are the students others obey because they are afraid not to?” 6) “Who are the students who are leaders?” 7) “Who are the students who lead the troublemakers?” and, 8) “Who are the students that other students think are cool?” As with nominations for aggression, students could nominate as many peers as they wished. Item analysis showed that item 5, “Who are the students others obey because they are afraid not to?” did not contribute to the internal consistency of the influence scale and it was removed from the final scale. The remaining seven items formed an influence scale with excellent internal consistency (.90 by Cronbach’s α). Importantly, the item about leading the troublemakers (item 7) correlated strongly with the total scale less that item (r = .62) as did the item asking which students others try to be like (r = .64), suggesting that the scale was tapping unconventional as well as conventional influence among peers.

Teacher ratings of peer influence were obtained on a subsample of students (n = 38). Immediately after making the aggression nominations, teachers rated students who had been nominated in the top quartile on, aggression. Teachers first nominated any students they wished to nominate and then gave ratings of influence because we were interested in selecting the most influential students within the aggressive students. This procedure was also intended to preserve a degree of independence between the teacher nominations of aggression and ratings of influence. Teachers were asked to give each student a single rating on influence among peers, using the following items to guide their ratings; 1) “Who are the students other students listen to about attitudes, how to behave, what’s good, important, or ‘cool?”; 2) “Who sets the trends among students?”; 3) “Who seems respected by other students?”; and, 4) “These should be the students that other students try to be like, try to imitate.” Social influence ratings were made a scale of “ 1” (not at all influential among peers) to “5” (very influential among peers).

Additional Peer Nomination Measures

We collected peer nomination measures of popularity and rejection among peers in order to test the discriminant validity of the peer social influence measure. Peer popularity was assessed using two items from the Peer Nomination Inventory: 1) “Which students are your friends?” and 2) “Which students have a lot of friends?” These items correlated .44 with each other. Peer rejection was assessed using a single item from the Peer Nomination Inventory, “Which students do you really not like?”

Procedures

Students completed the peer nominations at their school desks in a group administration conducted by an assessor unfamiliar to them. The administrator read each statement and paced the children so that sufficient time was spent on each question. The sixth-grade teachers completed nomination and rating forms without the research staff present and then returned these forms to the research staff. Teachers were paid $25 each for completing the measures. Students who returned signed parental consent forms were each given a $5 restaurant gift certificate, whether or not parents gave permission for them to provide nominations. For the purpose of this paper we define teacher-nominated aggressive students as those students nominated by their teachers for high levels of aggressive behavior (n = 38). We define selected students as those who were nominated for aggression and received a rating of 4 or 5 on the 5-point teacher social influence scale (n = 18). The selected students constituted the group that would have been recruited to participate in the targeted intervention.

RESULTS

First, we compare consented and nonconsented students on peer nomination measures. This was possible without violating consent because students were allowed to nominate any student in their classrooms, and no identifiers were retained on students without consent. Next, we provide descriptive statistics and correlations across the different measures. We then provide results on our first question of whether aggression and peer influence tap distinct dimensions of youth’s social behavior. Next, we present findings on the convergent validity of teacher and peer ratings of aggression and peer influence, and on the sensitivity and specificity of the teacher ratings of influence. Finally, we investigate the multivariate results of the selection procedure.

Comparison of Those Who Provided Nominations With Those Who Did Not

Because slightly over half of students provided peer nominations, it was important to determine the representativeness of the sample of nominators. Sixty-three students (50.8%) had consent to participate and provided peer nominations of all the students in their grade. To examine potential differences between nominators and those not providing nominations, we conducted F-tests of peer-nominated aggression, social influence, popularity, and rejection by nominator group. There was no significant difference between the nominators and nonnominators on aggression [F(1, 122) < 1, ns; d = .09]. On peer nominated influence, there was a significant difference, with the nominators (M = .25, SD = .13) scoring lower in social influence than the nonnominators [M = .31, S = .18; F(1, 122) = 5.36, p < .05; d = .42]. Nonnominators were also more popular than nominators [.55 vs. .47, F(1, 122) = 5.57, p < .05; d = .43) and there was no difference between nominators and nonnominators on peer rejection [F(1, 122) = .01, ns; d = 0.00], These findings suggest that overall, the nominators were somewhat less socially influential and popular than those students who did not have consent to participate.

Descriptive Information

Descriptive statistics and correlations among teacher ratings of influence and peer nominations of aggression, influence, popularity, and rejection are shown in Table 1. The correlation matrix shown is the result of pairwise deletion of cases with missing data. Teacher ratings of influence were only made on students already nominated for aggression, whereas peer nominations of aggression and influence were gathered for all children.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Teacher Influence Ratings and Peer Nominations

| Correlations |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | (n = 38)* | Peer-nominated (n = 124) | ||||

| Teacher ratings of social influence | 3.37 | 1.26 | 1.00 | ||||

| Aggression | 0.22 | 0.18 | .53** | 1.00 | |||

| Social influence | 0.28 | 0.16 | .70*** | .40*** | 1.00 | ||

| Popularity | 0.53 | 0.21 | .31* | −.23* | .33*** | 1.00 | |

| Rejection | 0.23 | 0.16 | −.02 | .58*** | −.12 | −.62*** | 1.00 |

Note: Because teachers rated the social influence of only the teacher-nominated aggressive students (n = 38) pairwise descriptive statistics and correlations are reported.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discriminant Validity

We addressed the question of whether social influence was distinct from, other measures of social factors by testing the extent to which teacher nominations and peer ratings of social influence were associated with peer nominations of rejection, popularity, and aggression. The results provided evidence for the discriminant validity of the social influence measures. As shown in Table 1, neither teacher nor peer reports of social influence were significantly associated with peer-nominated rejection. The positive correlation between teacher-rated social influence and peer-nominated popularity was only marginally significant, and the correlation between peer-nominated social influence and peer-nominated popularity, although statistically significant, was only moderate in magnitude (r = .33). Notably, both teacher and peer reports of social influence were positively associated with peer-nominated aggression.

To further explore the relation between measures of social influence and aggression, we tested whether peer-nominated social influence differed among students who were nominated by their teachers as aggressive as compared to those not nominated. The mean peer-nominated influence score was higher among the teacher-nominated aggressive students (.34) relative to the nonnominated students (.25). The difference between these means was statistically significant [t(122) = 3.13 p < .001; d = .57] and accounted for 7.5% of the variance in peer-nominated influence. This result was not consistent with our prediction that aggression and social influence would be distinct. However, given the correlation between influence and aggression seen in Table 1, it was also possible that this mean difference did not reflect the association between aggression and influence, but was the result of common method variation. If this were the case, and levels of peer-nominated aggression, were held constant, the relation between teacher-rated aggression and peer-nominated influence would be rendered non-significant or eliminated entirely. To evaluate this possibility, we entered the peer-nominated aggression as a covariate in an ANCOVA of peer-nominated influence on teacher nomination status. The difference on social influence between the teacher-nominated aggressive students and non-nominated students was rendered non-significant as expected [Means = .27 and .29; F(1, 121) < 1, ns; η2 = .01]. Thus, the observed association between teacher-nominated aggression and peer-nominated influence was due to a third variable, namely peer-nominated aggression, which correlated with teacher nominations of aggression and peer nominations of influence. These results suggest that teachers were discriminating between aggression and influence when rating peer influence, even among the most aggressive students.

Convergent Validity

The second hypothesis predicted strong associations between peer nominations of influence and teacher ratings of influence. As can be seen in Table 1, the correlation between teacher ratings of influence and peer nominations of influence was highly significant (r = .70, p < .001). Because peer-nominated influence correlated significantly with peer-nominated aggression, we wanted to determine the extent to which common method variance in the peer nominations might have inflated the correlation between teacher and student ratings of peer influence. “We used a regression analysis to calculate the partial correlation between teacher and peer measures of social influence, controlling for peer-nominated aggression. This analysis found that the partial correlation between teacher and peer measures of influence, controlling for peer-nominated aggression, remained highly significant (r = .70, p < .001), Thus, our results show evidence for convergent validity between teacher and peer ratings of influence.

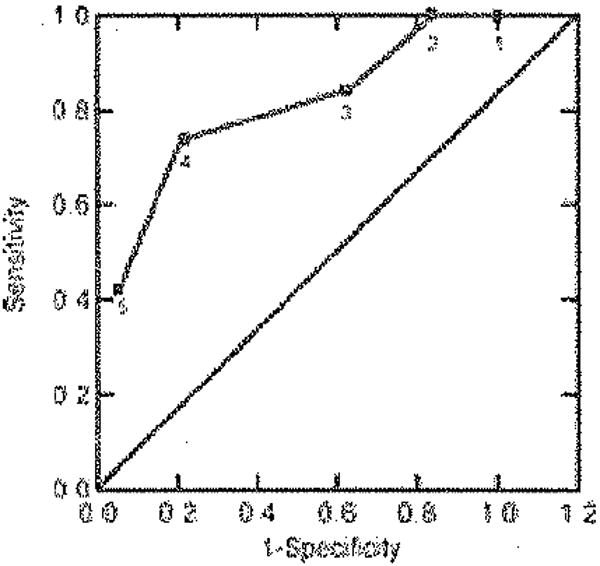

Related to the issue of convergent validity is the definition of a cut score to define students who will be recruited for intervention. To determine the optimal cut score for selecting influential students among those nominated for aggression, and to evaluate the adequacy of the teacher influence measure for selection, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the measure. We dichotomized the peer-nominated influence scores of the students nominated for aggression to produce a categorical score that would allow calculation of sensitivity and specificity. Figure 1 is a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve of the teacher ratings of peer influence. The curve plots the sensitivity of the measure (proportion correctly selected) against the reflected specificty of the measure (1—proportion correctly not selected) for the 38 highly aggressive students rated by teachers. Each potential cut score (1–5) is labeled. The distance between the curve and the diagonal suggests that the measure is substantially more accurate in selection than would be expected by chance alone. In addition, the curve clearly shows that a cut score of 4 on the teacher influence measure maximizes both sensitivity (.74) and specificity (.79). This score was used as a cut score for selecting influential students among those nominated for aggression.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve of the teacher influence measure predicting dichotomized peer-nominated influence scores, and showing potential cut scores.

Selection, Aggression, and Influence

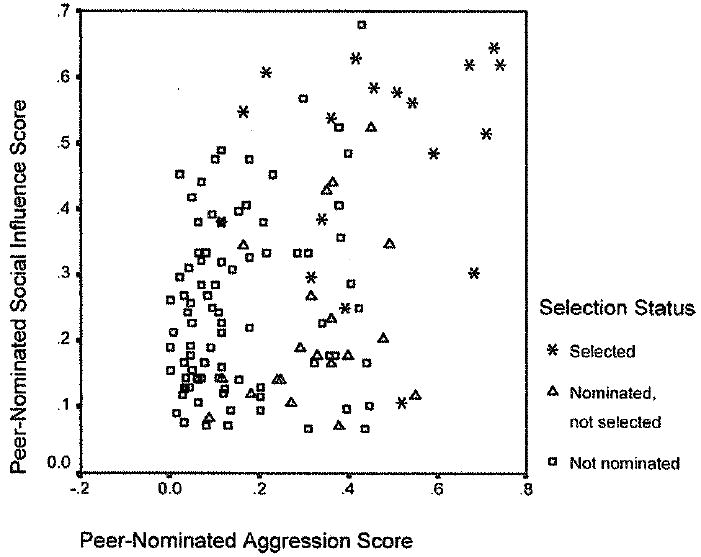

Our final analysis concerned differences between students nominated by their teachers for aggression and those selected for participation in the intervention based on both aggression and influence on the joint distribution of aggression and influence. Specifically, we hypothesized that students who were selected for the intervention because their teachers nominated them as aggressive and rated them as influential would have higher peer ratings of aggression and influence than would students who were either nominated but not selected, or students who were not nominated. A MANOVA comparing these three nested groups (total sample, nominated, selected) on peer-nominated aggression and influence scores returned significant multivariate effects for nominated status [multivariate F(2, 120) by Wilks λ = 40.66, p < .001, η2 = .40] and selected status (nested within nominated status) [multivariate F(2, 120) by Wilks λ = 18.98, p < .001, η2 = .24]. Examination of the univariate effects showed significant effects for nominated status on aggression [F(1, 121) = 78.01, p < .001, η2 = 39) and influence [F(1, 121) = 14.32, p < .001, η2 = .06]. Within nominated status, there were significant univariate effects for selected status on aggression [F (1, 121) = 10.52, p < .01, η2 = .08 ] and influence [F(1, 121)= 33.95, p < .01, η2 = .22]. Teacher-nominated aggressive students had a higher mean aggression score than nonnominated students (means = .40 and .27, d = .11), and within the teacher-nominated aggressive students, selected students had higher aggression scores than did those not selected (means = .47 and .32, d = .83). Teacher-nominated aggressive students were also viewed as more influential than non-nominated students by their peers (means = .35 and .25, d = .57), and within teacher-nominated status, the difference between selected and nonselected students was substantial (means = .48 and .22, d = .93).Figure 2 is a scatterplot of peer-nominated aggression and influence. The markers used to identify each case illustrate selection status. Those students who were nominated and selected based on teacher selection showed substantial differences in the joint distribution of their peer-nominated aggression and peer-nominated influence scores. These results support our hypothesis that the selection procedures identified students who were both aggressive and influential according to peer nominations.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of peer-nominated aggression and influence scores, showing teacher selection status.

DISCUSSION

The present study was undertaken to evaluate a method for identifying high-risk, students who were both aggressive and influential among their peers. Our findings suggested that the peer influence construct was not isomorphic with aggression and other domains of youth social behavior. In addition, teacher ratings of peer influence correlated highly with peer ratings, therefore showing good convergent validity, and the teacher measure of influence discriminated among influential and less influential students among the aggressive students. The selection procedure appears to have identified students who were both highly aggressive and influential among their peers. Specifically, this study suggests that when teachers are asked to first nominate an aggressive subgroup and then rate aggressive students on influence, their discrimination of relative influence is similar to that which would come from the students. This may mean that if done in this manner, teacher nominations can serve as good proxies to the more cumbersome peer nomination procedure in selecting students for targeted interventions.

The peer-nominated influence scale and the anchors for teacher ratings of influence were designed to tap influence among peers that was not necessarily conventional leadership. The correlation of the item assessing leadership of troublemakers with the full scale in the peer-nominated influence measure suggests that the measure was lapping social influence that was both “antiestablishment” and conventional in nature. Furthermore, the high correlation between the teacher and peer measures of social influence suggests that teachers were also attending to both conventional and unconventional social influence in making their ratings. The lack of a relation between the influence scale and an item assessing influence by intimidation suggests that what is being measured is influence over others that is not necessarily conventional but is also not coercive.

Analyses testing convergent validity found a strong relation between peer-nominated and teacher-rated social influence among the students nominated by their teachers for aggression. This relation held even when controlling for peer-nominated aggression. In fact, the correlation between teacher and peer measures of social influence found in this investigation was of a similar magnitude as the correlations reported between peer and teacher measures of aggression (e.g., Huesmann et al., 1994). This is significant because teacher reports, though widely used, have been criticized for halo effects (Epkins, 1994) and underreporting of problem behaviors (Biederman et al, 1998). Teachers are in an excellent position to observe social behavior, and to know the most socially influential children in their classes. It is not surprising that they would be able to accurately identify children’s degrees of social influence.

Overall, the procedure using teacher nominations for aggression and teacher ratings of children’s influence among their peers resulted in the selection of students who, according to peer nomination measures, were both significantly more aggressive and influential than their peers. Thus, the procedure appears to have served its intended purpose. Intervening with students in the belief that they will exercise influence over their peers was the aim of the targeted small group intervention of the Metropolitan Area Child Study (cf. Guerra et al., 1995; Letendre et al., in press; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group, 2002). However, the Metropolitan Area Child Study did not select students for intervention based on their degree of influence among peers. To our knowledge, the MVPP is the first prevention trial to explicitly include peer influence in its selection procedure.

These findings have implications for the methods used when targeting high-risk adolescents for preventive interventions. The theory behind the MVPP is that targeting students who are both aggressive and influential can contribute to short-term, reductions in school levels of aggression and prevent the emergence of aggressive behavior in the longer term. In order to conduct such selective preventive interventions, whether for research trials or full-scale implementation, it will be necessary to identify individuals who are most likely to increase risk in the target population. When such interventions are implemented in middle schools or high schools, the numbers of children and the absence of small self-contained ecological units make sociometric measures of influence impractical. This investigation provides evidence that teachers can provide accurate assessments of students’ degrees of influence among their peers. Thus, the use of teacher ratings rather than peer nominations can help make selection of appropriate students for intervention more practical.

This selection procedure can be tailored to maximize either sensitivity or specificity for selecting either aggressive or influential students by adjusting the teacher-rated influence cut scores or the proportion of students teachers are to nominate. The fact that the intervention was intended to affect aggression through peer influence processes argued for greater sensitivity in detecting influential youth, and thus a lower cut score, whereas the cost of administering an indicated intervention argued for greater specificity and a higher cut score. We selected a cut score of 4 on the teacher ratings influence, believing it represented the most acceptable compromise (Kraemer et al., 1999). Greater sensitivity and specificity would certainly have been desirable, and might have been achieved with multiple assessments over a longer period of time (Petras et al., 2004). However, this selection procedure, like most assessments of risk for aggression, lacks a “gold standard” against which to measure the adequacy of a selection procedure. The peer-nominated influence scores were dichotomized in order to estimate sensitivity and specificity.

It is important to note the limitations of the current study. The first possible limitation is the proportion of students in each class who had consent to complete peer nomination measures. There were small but significant differences between, consented and nonconsented students on peer popularity and influence ratings, in which nominators were characterized as less popular and less influential than non-nominators. Thus, those students who provided peer nominations may have been somewhat less sensitive in identifying those students who were highly influential, given their relatively lower popularity and influence among peers. We did, however, find no significant difference between nominators and nonnominators on either aggression or peer rejection, and we do not believe that differences in consent status seriously compromise the validity of these results.

Asking teachers and consenting students to nominate students who do not have consent may have ethical implications that we believe are balanced by the societal good of conducting indicated interventions and by the minimal risk posed by these selection procedures. Although it is possible that nonconsenting students were exposed to greater risk than in everyday life through these procedures, the behaviors assessed by the peer nominations were common, not uniformly negative or necessarily stigmatizing. Many were positive behaviors and attributes (e.g., “Who do other kids try to be like?”). Additionally, limiting nominations to children with consent might have been more likely to stigmatize than would allowing children to nominate any class member, as being presented with a subset of children would invite speculation regarding why a child was in the subset.

Another possible limitation is that the study was conducted in school settings structured more like lower grade schools than large middle schools. The selection procedure was intended for a multi-site study, in which many middle schools were of substantial size. We believed that the validity of the procedure could not be tested adequately in such large middle schools, as students would be unlikely to know each other well enough to provide reliable sociometric data, and thus, to validate a method based on, teacher ratings. However, in the small schools chosen for this investigation, teachers might have been likely to have more opportunities to observe student behavior and understand patterns of social influence than would teachers in larger middle schools. The generalizability of this study’s findings may also be limited to some extent by the location of the schools. Both schools were in distressed, inner-city areas, where aggression may have been tolerated to a greater extent than would have been the case in other settings. Greater tolerance of aggression might tend to exaggerate the relation between aggression and influence found in this investigation.

Related to the limitation posed by school size is the issue of the small number of teachers and schools involved in this study. Given these limitations, the results are suggestive rather than conclusive. Future research with larger numbers of teachers and schools, and perhaps in larger schools and/or using multiple points of assessment, will be needed to establish the validity of this procedure.

In summary, our findings suggest that teachers can identify students who are considered both aggressive and influential by their peers. Social influence, whether measured by teacher ratings or peer nominations, appeared to be distinct from, other aspects of youth social behavior. Given the developmental relevance of peers as powerful socializing agents during early adolescence, our procedures for identifying students who are both aggressive and influential among their peers show promise for use in targeted prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by cooperative agreement number #99067 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project included Robin Ikeda, MD, Thomas Simon, PhD, Emilie Smith, PhD, and LeRoy Reese, PhD from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; David Rabiner, PhD, Shari Miller-Johnson, PhD, Donna-Marie Winn, Ph.D, Steven Asher, PhD, and Kenneth Dodge, PhD from Duke University; Arthur Home, PhD, Pamela Orpinas, PhD, William Quinn, PhD, and Carl Huberty, PhD from the University of Georgia; Patrick Tolan, PhD, Deborah Gorman-Smith, PhD, David Henry, PhD, and Franklin Gay, MPH from the University of Illinois at Chicago; and Albert Farrell, PhD, Aleta Meyer, PhD, Terri Sullivan, PhD, Kevin Allison, PhD from Virginia Commonwealth University

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Realmuto GM, Crosby RD, MacDonald AW. Community-based multiple-gate screening of children at risk for conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:521–544. doi: 10.1007/BF01447212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Biased maternal reporting of child psychopathology? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:10–11. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casat CD, North JH, Boyle-Whitesel M. Identification of elementary school children at risk for disruptive behavioral disturbance: Validation of a combined screening method. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1246–1253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Jacobs MR. The role of social context in the prevention of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Terry JR, Zakriski A, Lochman J. Early adolescent social influences on delinquent behavior. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, Ramey SL, Shure MB, Long B. The science of prevention. A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Griesler PC. Peer adaptation in the development of antisocial behavior: A confluence model. In: Huesmann LR, editor. Aggressive behavior: Current perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescents friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Epkins CC. Peer ratings of depression, anxiety, and aggression in inpatient and elementary school children: Rating biases and influence of rater’s self-reported depression, anxiety, and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:611–640. doi: 10.1007/BF02168941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eron LD, Huesmann LR. The stability of aggressive behavior in cross-national comparison. In: Kagitcibasi C, editor. Growth and progress, in cross-cultural psychology; Proceedings of the 8th Annual Meeting of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology; Istanbul, Turkey. 1987. pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Eron LD, Walder LO, Lefkowitz MM. The learning of aggression in children. Boston, MA: Little-Brown; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG. Social functionality of aggression as a moderator of prevention impact. In: Guerra NG, editor. Person in context approaches to prevention; Symposium conducted at the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; San Francisco, CA. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Eron LD, Huesmann LR, Tolan PH, van Acker R. A cognitive/ecological approach to the prevention and mitigation of violence and aggression in inner-city youth. In: Bjorkquist K, Fry DP, editors. Styles of conflict resolution: Models and applications from around the world. New York: Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Farrell A The Multisite Violence Prevention Project. The study designed by a committee: Research Design of the GREAT Schools and Families Project. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD. Childhood aggression and adult criminality. In: McCord J, editor. Advances in criminological theory: Crime facts, fictions, and theory. New Brunswick: NJL Transaction; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD, Guerra NG, Crawshaw VB. Measuring children’s aggression with teachers’ predictions of peer nominations. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Maxwell CD, Eron L, Dalhberg LL, Guerra NG, Tolan PH, Van Acker R, Henry D. Evaluating a cognitive/ecological program for the prevention of aggression among urban children. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(Suppl):120–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Measuring the potency of risk factors for clinical or policy significance. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Letendre J, Henry D, Tolan PH. Leader and therapeutic influences and prosocial skill building in school based groups to prevent aggression. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13:569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Screening of child behavior problems for prevention programs at school entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:549–559. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Sociodemographic disadvantage and psychosocial adjustment: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR, editors. Developmental psychopathology Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 459–483. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AL, Allison KW, Reese L, Gay F The Multi-site Violence Prevention Project. Choosing to be violence-free in middle-school: The student component of the GREAT schools and families universal program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.014. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Costanzo P. If you can’t beat ‘em… have them join you: Peer-based interventions during adolescence. In: Dodge K, Kupersmidt J, editors. Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention to policy: A festschrift in honor of John D Coie. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Costanzo P, Coie JD, Rose MR, Browne DC, Johnson C. Peer social structure and risk-taking behaviors among African American Early Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence in press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Sullivan T, Simon T The Multisite Violence Prevention Project. Evaluation of a multi-site violence prevention study: Measures, procedures and baseline data. American Journal of Preventive Medicine in press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A development taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Horne AM The Multisite Violence Prevention Project. A teacher-focused approach to prevent and reduce students’ aggressive behavior: The GREAT teacher program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.016. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras H, Chilcoat H, Ialongo N, Leaf P, Kellam S. Utility of the TOCA-R scores during the elementary school years in identifying later violence among adolescent males. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:88–96. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Eddy JM. The prevention of antisocial behavior: Some considerations in the search or effective interventions. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Schachar RJ, Sandberg S, Rutter M. Agreement between teachers’ ratings and observations of hyperactivity, inattentiveness, and defiance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00915450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Gorman-Smith D, Quinn W, Rabiner D, Tolan P, Winn DM The Multisite Violence Prevention Project. Community-based multiple family groups to prevent and reduce violent and aggressive behavior: The GREAT families program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.018. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yugar JM, Shapiro ES. Elementary children’s school friendship: A comparison of peer assessment methodologies. School Psychology Review. 2001;30:468–585. [Google Scholar]

- Zakriski AL, Seifer R, Sheidrick C, Prinstein MJ, Dickstein S, Sameroff AJ. Child-focused versus school-focused sociometrics: A challenge for the applied researcher. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1999;20:481–499. [Google Scholar]