Abstract

High-frequency oscillations of a rigid sphere in an incompressible viscous fluid moving normal to a rigid plane are considered when the ratio of minimum clearance to sphere radius is small. Asymptotic expansions are constructed that permit an analytical estimate of the force acting on the sphere as a result of its motion. An inner expansion, valid in the neighborhood of the minimum gap, reflects the dominance of viscous effects and fluid inertia. An outer expansion, valid outside the gap, reflects the dominance of fluid inertia with a correction for an oscillating viscous boundary layer. The results are applied to the hydrodynamics of the tapping mode of an atomic force microscope and to the dynamic calibration of its cantilevers.

Keywords: asymptotic expansions, oscillating boundary layers, wall effects, atomic force microscopy

1. Introduction

The present problem is motivated by the need to better understand the fluid tapping mode of an atomic force microscope (AFM) when a microsphere is attached to the cantilever. The fluid tapping mode allows the high-resolution investigation of delicate biological samples with minimal damage [1, 2]. As a first step in understanding the hydrodynamic interaction with a nearby compliant surface, we first consider the hydrodynamic interaction with a rigid surface. The former problem is important for determining the material properties of soft materials at acoustic frequencies, e.g., tissues of the inner ear. The latter problem is relevant in its own right, since it provides a novel method for the dynamic calibration of AFM cantilevers. Stokes [3] first considered the hydrodynamics of small oscillations of a sphere in an unbounded viscous fluid. Brenner [4] used bipolar coordinates to study steady Stokes flow of a sphere toward a rigid plane. Cox and Brenner [5] reconsidered Brenner's problem [4] using singular perturbation techniques to study the case of small gaps and unidirectional fluid inertia (not oscillatory motion). Cooley and O'Neill [6] also used singular perturbation asymptotic expansions to study Brenner's problem when the clearance was small. It is well known that the present problem cannot be solved exactly in bipolar coordinates [7, 8]. By using the boundary integral equation technique, Feng, Ganatos, and Weinbaum [8] solved this problem numerically in the context of a Brinkman medium rather than an oscillating flow. Recently, Clarke et al. [9] studied the present problem for two-dimensional rather than axisymmetric flow. Here, the combination of small gap and high frequency is of particular interest for atomic force microscopy. While this case was not treated previously and would present difficulties if studied numerically, fortunately it can be studied using singular perturbation asymptotic methods. These techniques were originally developed in the 1960s fluid mechanics literature [6, 10] and are revived here to solve an important problem relevant to the nanomechanics of the AFM. The problem is singular as the gap approaches zero, since in that (outer) limit the sphere is tangent to the plane, and kinematic conditions cannot be satisfied on both the sphere and the plane. In the present problem the outer expansion is dominated by fluid inertia, rather than fluid viscosity, and the inner problem is dominated by both fluid viscosity and inertia. The outer inviscid solution is corrected for an oscillatory boundary layer. These features set this analysis apart from previous work. The inner lubrication-type expansion asymptotically matches to the outer inviscid expansion corrected for the oscillatory boundary layer.

2. Formulation

Consider a sphere of radius a0 undergoing small oscillations with frequency ω in an incompressible viscous fluid with density ρ and viscosity μ. Our goal is to calculate the hydrodynamic force acting on the sphere when the minimum clearance between the sphere surface and the rigid wall is h. It is assumed that the amplitude As of the sphere oscillation is small compared to h, so that the linearized unsteady Stokes equations for the fluid motion apply. Under this condition the nonlinear convective acceleration terms can be neglected compared to the temporal acceleration terms. We use cylindrical coordinates (a0r, θ, a0z) and scale the pressure P and velocity V⃗ as P = μUp/a0 and V⃗ = Uq⃗ = (Uu, 0, Uw), where U exp[−iωt] describes the oscillatory motion of the sphere in the z-direction. In the frequency domain, with the factor exp[−iωt] suppressed, the momentum and continuity equations are then, respectively,

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

where β2 is the dimensionless frequency parameter . Note that iβ2q⃗ in (2.1) is the linearized version of iβ2(q⃗ + As/a0 q⃗ · ∇q⃗). Since As ≪ h, As/a0 ≪; ε (the clearance parameter ε is defined below), the nonlinear convective term can be neglected. Since the problem is axisymmetric, it is convenient to express the velocity components u and w in terms of the Stokes stream function Ψ(r, z):

| (2.3) |

which satisfy (2.2) identically. The pressure can be eliminated from (2.1) by taking its curl, which leads to

| (2.4) |

where

| (2.5) |

The boundary conditions are u = w = 0 on the rigid wall located at z = 0, and u = 0 and w = −1 on the approaching sphere. In terms of the stream function these conditions are equivalent to

| (2.6) |

| (2.7) |

on the wall and sphere, respectively. The surface of the portion of the sphere closest to the wall is described by the relation

| (2.8) |

where ε = h/a0 is the clearance parameter. In what follows we seek an approximate solution to the problem defined by (2.1)–(2.8) subject to the conditions that ε ≪ 1, β2 = ε−2α ≫ 1, with α2 = ρωa0h/μ = O(1), which correspond to small clearance and high frequency. This scaling is important for the tapping mode of the AFM. We now construct inner and outer expansions as Cooley and O'Neill [6] did for the steady problem, but here we must take care to include the oscillatory effects.

3. The Inner Region Expansion and Solution

In the neighborhood of the origin, O'Neill and Stewartson [10] introduced the stretched coordinates R, Z defined by

| (3.1) |

This scaling is motivated by (2.8), which transforms and expands to

| (3.2) |

where . Equation (2.7) suggests the expansion for the stream function

| (3.3) |

otherwise there will be no O(1) forcing, which results in the following dominant equation stemming from (2.4):

| (3.4) |

The rigid wall boundary conditions (2.6) yield

| (3.5) |

Using a Taylor series expansion to transfer the sphere boundary conditions (2.7) to Z = H yields

| (3.6) |

Analysis of the correction term ψ1 can be carried out but is not required in the present analysis. The solution of (3.4) subject to (3.5) and (3.6) is

| (3.7) |

where .

4. The Outer Region Expansion and Solution

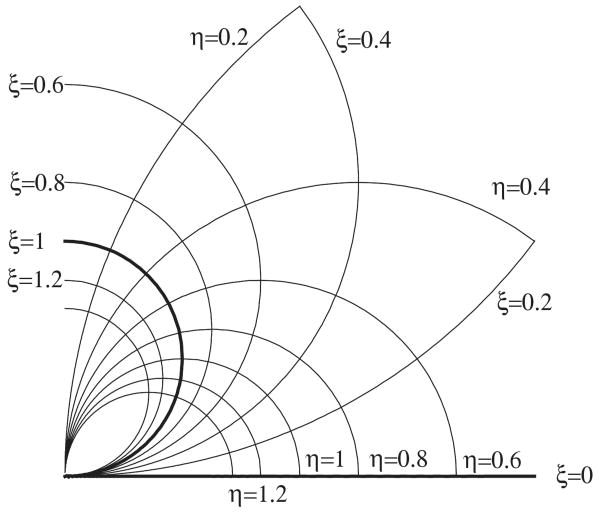

Away from the origin we construct an outer expansion letting ε → 0 in the unstrained (r, z) coordinates. In this limit, O'Neill and Stewartson [10] first noticed that the sphere becomes tangent to the wall (cf. (2.8)). They then introduced the new tangent sphere coordinates (ξ, η) defined by the relations

| (4.1) |

Since

| (4.2) |

curves of constant ξ correspond to a family of circles tangent to the plane z = 0 at the origin. Curves of constant η form an orthogonal family of circles. The rigid wall is now given by ξ = 0, and the sphere is given by ξ = 1; see Figure 4.1. The origin r = z = 0 corresponds to η = ∞ and must be excluded since the sphere cannot penetrate the wall. Instead we shall require matching to the transition layer expansion as η → ∞. As ε → 0, we note that β2 = ε−2α2 becomes large and (2.4) is dominated by the inviscid operator E2ψ = 0, which becomes

Fig. 4.1. Tangent sphere coordinates.

| (4.3) |

A general solution to (4.2) is

| (4.4) |

Setting B(λ) = 0 implies ψ(0, η) = 0, which makes the wall a streamline. Choosing A(λ) = 2λe−λ/ sinh λ results in

| (4.5) |

which satisfies the second part of (2.7) on the sphere.

5. The Outer Boundary Layer Expansion and Solution

The inviscid outer solution can be corrected to satisfy the first parts of boundary conditions (2.6)–(2.7) by constructing boundary layers in the neighborhoods of ξ = 0 and ξ = 1. Here all we require is the boundary layer on the sphere. Consequently, we introduce a stretched boundary layer coordinate

| (5.1) |

along with the expansion for the boundary layer stream function

| (5.2) |

Introducing (5.1) and (5.2) into (2.4) yields the dominant equation

| (5.3) |

where Ω0 is defined by

| (5.4) |

and Λ2 is defined by

| (5.5) |

Ω0 is the dominant part E2ψ0, which is related to the vorticity of the flow. Since vorticity must vanish outside the boundary layer as ξ* → ∞, we take the decaying solution of (5.3),

| (5.6) |

Here we must take the root having a positive real part. Substituting (5.6) into (5.4) and integrating twice gives

| (5.7) |

Zero tangential velocity on the sphere Ψ0,ξ* (0, η) = 0 requires

| (5.8) |

while matching the boundary layer tangential velocity far from the sphere to the inviscid tangential velocity requires

| (5.9) |

where the right-hand side can be computed from (4.4). To complete the boundary layer solution we require the the sphere surface to be a streamline, Ψ0(0, η) = 0 in sphere-fixed coordinates, which leads to

| (5.10) |

6. Asymptotic Matching of Inner and Outer Expansions

Consider first the behavior of the outer boundary layer solution toward the gap for η ≫ 1. Then (5.5) shows that Λ ≪ 1, so we can expand the exponential in (5.7) for small argument (keeping ξ* fixed) to obtain

| (6.1) |

after applying (5.8) and (5.10). Expanding the integrand of (4.3) for small λ, then integrating and applying (5.9), yields the behavior of b(η) for large η: b(η) ≃ −2/η2+0(1/η4). Thus for large η we find

| (6.2) |

To show this matches asymptotically to the inner expansion we first convert (3.7) to sphere-fixed coordinates by subtracting R2/2 and then expanding it for x, y ≫ 1 to get the behavior away from the gap, and then for y − x ≪ 1 to get the behavior near the sphere surface:

| (6.3) |

Finally, expressing (6.3) in terms of boundary layer coordinates (ξ*, η) via (4.1) and (5.1) we have for η ≫ 1

| (6.4) |

which matches (6.2). The inner expansion and outer boundary layer expansion match in an overlap domain 1 ≪ η ≪ ε−1/2.

7. Force Acting on the Sphere

The cylindrical components of the force acting on any axisymmetric shape in an axisymmetric oscillatory Stokes flow are (0, 0, π μU a0f), where

| (7.1) |

the integral being taken from the top to bottom poles along a meridian γ, where n⃗ is an outward normal to the body. Equation (7.1) was first derived by Stimson and Jeffery [11] for steady Stokes flow. The extension to oscillatory Stokes flow (β ≠ 0) given here can be obtained following the method outlined in Happel and Brenner [12] in their rederivation of the Stimson and Jeffery result. As a check on (7.1) we note that when we use the Ψ originally derived by Stokes [3], (7.1) reproduces the following known result for the force on a sphere oscillating in an unbounded fluid derived by Landau and Lifshitz [13], who integrated stresses on the sphere:

| (7.2) |

In the present problem, the second integral in (7.1) can be evaluated simply from the boundary condition on the sphere. In spherical polar coordinates, r = sin θ, where θ is the polar angle measured from the top pole, , and dγ = dθ. Hence, the second integral produces the result . To evaluate the first integral in (7.1), we use the method of Cooley and O'Neill [6], who split γ into two regions separated by a meridional point γ0 located in a domain where inner and outer expansions match, and then sum contributions from the outer and inner expansions. First we consider the contribution from the outer expansion. In (ξ, η) coordinates we note the following relations derived by Cooley and O'Neill [6]:

We also note from (5.1) and (4.1),

and E2Ψ ∼ ε−1Ω0, where Ω0 is given by (5.4). The outer expansion then contributes to the first integral of (7.1):

| (7.3) |

Here η0 ≫ 1 lies in the overlap domain of the inner and outer expansions 1 ≪ η0 ≪ ε−1/2, and b(η) is given by (4.4) and (5.9). The integral in (7.3) can be evaluated by letting (0, η0) = (0, ∞) − (η0, ∞). The integration on (0, ∞) can be carried out in closed form, while the integration on (η0, ∞) can be evaluated asymptotically for large η0 with the result

| (7.4) |

where ζ is the Riemann zeta function and ζ(3) = 1.2026.

For the inner contribution to the force we return to (R, Z)-coordinates and we note the following relations derived by Cooley and O'Neill [6] that apply here:

The dominant contribution to the first integral of (7.1) from the inner expansion is

| (7.5) |

where the upper limit corresponds to η0 through . The total force on the sphere is . The integral can be evaluated asymptotically using the small argument expansion of the integrand for the lower limit and the large argument expansion of the integrand for the upper limit. It can be shown that the upper limit contributes a term that cancels the O(εη0)−2 term in (7.4) and contributes a term , resulting in the total force

| (7.6) |

where we must remember that we are free to choose any η0 in the overlap domain 1 ≪ η0≪ , subject also to the condition that the argument of the logarithmic term in (7.6) is large enough to justify using large argument asymptotics in the first place. A suitable choice is to take , which turns out to simplify the hydrodynamic added mass and resistance coefficients derived below. The hydrodynamic added mass M and the hydrodynamic resistance C are, respectively the positive coefficients of force proportional to the acceleration and velocity of the sphere. They are related to (7.6) by

| (7.7) |

| (7.8) |

where is the Stokes oscillatory boundary layer thickness. These can be compared with their values obtained in the absence of the wall, from (7.2):

| (7.9) |

| (7.10) |

Aside from relatively small differences in the oscillatory boundary layer corrections, the main effect of the nearby wall are the increased factors 3ζ(3) in the added mass and ao/h in the resistance.

8. Application to Atomic Force Microscopy

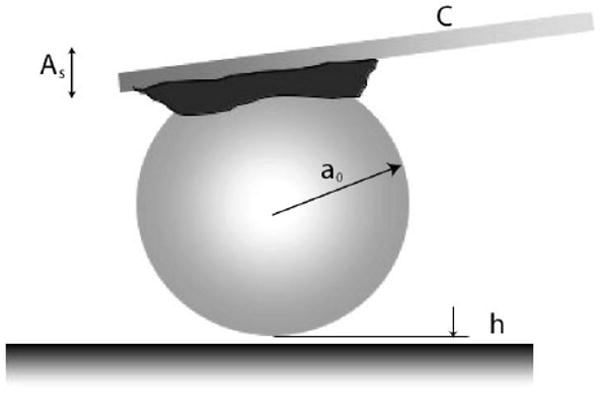

For some applications it is advantageous to attach a microsphere to the AFM cantilever [14]. For example, it affords the opportunity to better establish the hydrodynamic interaction than would be possible with the usual cantilever, which often has an inconvenient shape as far as hydrodynamics is concerned. The essential idea proposed here is that the sphere-wall interaction dominates the hydrodynamic changes that occur when the sphere-cantilever combination is brought into proximity to the wall (Figure 8.1). For a large enough microsphere, the cantilever-wall interaction will be small compared to the sphere-wall interaction and the present analysis should apply.

Fig. 8.1. Schematic of oscillating microsphere glued to cantilever.

The simplest description of the AFM tapping mode is the forced oscillation of an oscillator having mass m and spring constant k. Let Ap and As be the vertical displacement of the piezo head and the microsphere, respectively. Then the oscillator transfer function is given by

| (8.1) |

Here m denotes the unknown sum of the cantilever mass and its added hydrodynamic mass, as well as the mass of the attached microsphere, while M is the added hydrodynamic mass of the microsphere. One important application is the dynamic calibration of the cantilever spring constant k. A possible scheme would be to measure the phase lag φ of the sphere relative to the piezo head as some commercial AFM instruments can do. Equation (8.1) shows that when ,

| (8.2) |

independent of the value of C. Since only M is affected by the wall, the unknown mass m can be eliminated from (8.2) by making two frequency measurements (ωn, ωf) near the wall and far from the wall, respectively, where . Then k can be determined from

| (8.3) |

where the numerator can be computed from (7.7) and (7.9). Under the conditions of the validity of the theory, i.e., α < 1 and ε ≪ 1, we find that M > MStokes, and (8.3) predicts that ωn < ωf.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Emilios Dimitriadis, Sonya Smith, and Peter Bungay for helpful discussions, and also an anonymous referee for very helpful comments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the NIDCD intramural program project Z01-DC0000033-10.

References

- 1.Hansma PK, Cleveland JP, Radmacher M, Walters DA, Hillner PE, Bezanilla M, Fritz M, Vie D, Hansma HG, Prater CB, Massie J, Fukunaga L, Gurley J, Elings V. Tapping mode atomic force microscopy in liquids. Appl Phys Lett. 1994;64:1738–1740. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radmacher M, Fritz M, Hansma HG, Hansma PK. Direct observation of enzyme activity with the atomic force microscope. Science. 1994;265:1577–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.8079171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stokes GG. On the effect of internal friction of fluids on the motion of pendulums. Cambridge Phil Trans. 1851;9:8–106. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H. The slow motion of a sphere through a viscous fluid towards a plane surface. Chem Eng Sci. 1961;16:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox RG, Brenner H. The slow motion of a sphere through a viscous fluid towards a plane surface: II. Small gap widths, including inertial effects. Chem Eng Sci. 1967;22:1753–1777. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooley MDA, O'Neill ME. On the slow motion generated in a viscous fluid by the approach of a sphere to a plane wall or stationary sphere. Mathematika. 1969;16:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim S, Russel WB. The hydrodynamic interactions between two spheres in a Brinkman medium. J Fluid Mech. 1985;154:253–268. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng J, Ganatos P, Weinbaum S. Motion of a sphere near planar confining boundaries in a Brinkman medium. J Fluid Mech. 2000;375:265–296. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke RJ, Cox SM, Williams PM, Jensen OE. The drag on a microcantilever oscillating near a wall. J Fluid Mech. 2005;545:397–426. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Neill ME, Stewartson K. On the slow motion of a sphere parallel to a nearby plane wall. J Fluid Mech. 1967;27:705–724. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stimson M, Jeffery GB. The motion of two spheres in a viscous fluid. Proc Roy Soc A. 1926;111:110–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Happel J, Brenner H. Low Reynolds Number Hydrodynamics. Prentice–Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landau LD, Lifshitz EM. Fluid Mechanics. Pergamon Press; London: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitriadis EK, Horkay F, Maresca J, Kachar B, Chadwick RS. Determination of elastic moduli of thin layers of soft material using the atomic force microscope. Biophys J. 2002;82:2798–2810. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]