Abstract

Most human lymphomas originate from transformed germinal center (GC) B lymphocytes. While activating mutations and translocations of MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 promote specific GC lymphoma subtypes, other genetic and epigenetic modifications that contribute to malignant progression in the GC remain poorly defined. Recently, aberrant expression of the TCL1 proto-oncogene was identified in major GC lymphoma subtypes. TCL1 transgenic mice offer unique models of both aggressive GC and marginal zone B-cell lymphomas, further supporting a role for TCL1 in B-cell transformation. Here, restriction landmark genomic scanning was employed to discover tumor-associated epigenetic alterations in malignant GC and marginal zone B-cells in TCL1 transgenic mice. Multiple genes were identified that underwent DNA hypermethylation and decreased expression in TCL1 transgenic tumors. Further, we identified a secreted isoform of EPHA7, a member of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases that are able to influence tumor invasiveness, metastasis and neovascularization. EPHA7 was hypermethylated and repressed in both mouse and human GC B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with the potential to influence tumor progression and spread. These data provide the first set of hypermethylated genes with the potential to complement TCL1-mediated GC B-cell transformation and spread.

Keywords: DNA methylation, B-cell lymphoma, TCL1

Introduction

The TCL1 oncoprotein augments AKT activation and downstream signaling to promote cell proliferation and survival (Teitell, 2005). Dysregulated expression of TCL1 is a frequent molecular alteration in non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) that arise by transformation of germinal center (GC) B-cells (Teitell et al., 1999; Narducci et al., 2000; Said et al., 2001). Supporting an etiologic role in transformation, dysregulated expression of TCL1 in transgenic mouse B-cells throughout all stages of B-cell development promotes a spectrum of GC B-cell lymphoma subtypes that metastasize (Hoyer et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2006) or aggressive marginal zone-derived B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Bichi et al., 2002; Klein and Dalla-Favera, 2005; Yan et al., 2006). As TCL1 transgenic (TCL1-tg) mice develop lymphomas only after a prolonged latency (Hoyer et al., 2002) and fail to develop lymphomas for up to 20 months when crossed into a GC-deficient background (Shen et al., 2006), additional molecular alterations within the GC appear to be essential for B-cell transformation. Chromosomal translocations and aneuploidy have been identified in transformed GC B-cells in TCL1 transgenic mice (Shen et al., 2006), although it is unclear whether these genetic alterations drive or are merely reflective of the transformation process.

Cancer is associated with the accumulation of both genetic and epigenetic alterations (Esteller, 2003a; Herman and Baylin, 2003). DNA hypermethylation often correlates with inappropriate gene silencing and is well documented in primary human lymphomas and cell lines (Rush and Plass, 2002; Esteller, 2003b; Galm et al., 2006), and includes genes whose hypermethylation distinguish specific hematologic malignancies (Herman et al., 1997) or clinical outcome (Esteller et al., 2002). To date, altered DNA methylation in lymphoma has largely been addressed by direct candidate gene approaches. Therefore, it is likely that additional and important alterations in DNA methylation have yet to be described in lymphoma. Restriction landmark genomic scanning (RLGS) is a quantitative approach that distinguishes the methylation status of over 2000 genetic loci and is particularly well suited for studying DNA methylation in the invariant genetic background of inbred mouse strains (Costello et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2005). In this paper, we used RLGS to identify 115 lymphoma-associated alterations in DNA methylation in our TCL1 transgenic mouse model. We further investigated EphA7, a member of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases. We found that normal lymphocytes express and secrete a truncated isoform of EphA7 instead of the full-length EphA7 receptor. EPHA7 was selectively silenced by DNA hypermethylation in both mouse and human GC B-cell NHLs, with the potential to impact tumor growth and spread.

Results

DNA hypermethylation in TCL1-tg GC B-cell tumors

NotI—EcoRV–HinfI RLGS profiles were generated on GC B-cell tumors, bulk non-neoplastic splenic tissue and sorted non-malignant splenic B or T cells from TCL1-tg mice (Hoyer et al., 2002) (Supplementary Figure 1). The use of methylation-sensitive NotI permitted the assessment of CpG methylation at the NotI landmark site. All results were referenced to a previously described master mouse RLGS profile that assigns numbers and map coordinates to each RLGS locus (Yu et al., 2005). Initial comparison between RLGS profiles generated on non-malignant sorted B-cells versus sorted T cells revealed only two differences (1D19 lost and 3C05 gained in T cells versus B-cells) for 1800 analysed RLGS loci (data not shown). In contrast, whole spleens had 59 differences out of 1800 analysed RLGS spots compared with either the sorted B- or T-cell profiles (data not shown), indicative of cell-specific methylation patterns distinct to non-B- and non-T-cell populations in the spleen (i.e., macrophages, vasculature or other stromal elements).

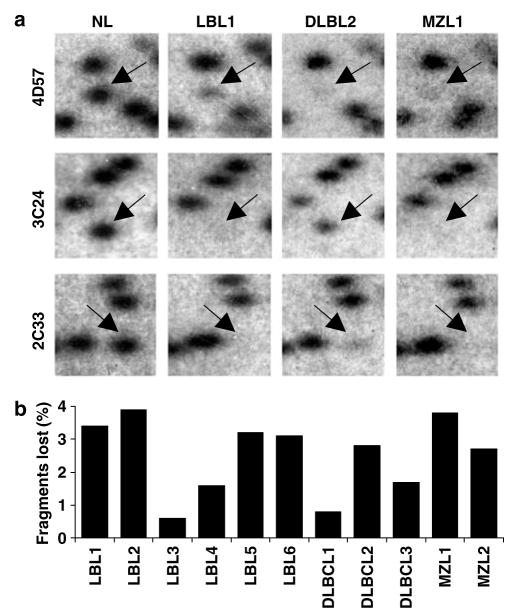

Our goal was to identify genes with the potential to suppress tumor growth or spread. Therefore, attention was focused on genes undergoing DNA hypermethylation in TCL1-tg B-cell tumors. Analysis was limited to those RLGS loci invariantly present in both the sorted B-cell profile and each of six separate profiles of TCL1-tg normal whole spleens. RLGS was performed on 11 TCL1-tg B-cell tumors, including six Burkitt-like/lymphoblastic lymphomas (LBL), three diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) and two marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) (Supplementary Table 1). Representative loci (4D57, 3C24 and 2C33) undergoing hypermethylation in one or more of the tumors are presented (Figure 1a). Of the 1741 RLGS loci analysed, 1626 loci were unaltered, whereas 115 loci were lost/hypermethylated in at least one tumor. The frequency of tumor-specific hypermethylation events ranged from 0.6 to 3.9% of the loci examined for each tumor, with a mean of 2.8% (Figure 1b). In the 11 tumors analysed, four loci were lost/hypermethylated in 10 tumors, three loci in nine tumors, seven loci in eight tumors, nine loci in seven tumors, nine loci in six tumors, 15 loci in five tumors, 18 loci in four tumors, 13loci in three tumors, 16 loci in two tumors and 22 loci in only one tumor. Statistical analysis using a standard goodness-of-fit test indicated that DNA methylation in TCL1-tg B-cell tumors occurred in a nonrandom distribution (P<0.0005). Using previously described methodologies (Yu et al., 2005), 78 of the 115 loci undergoing hypermethylation were cloned and verified (data not shown). Verified sequences were analysed by BLAT (Kent, 2002) and are summarized in Table 1. Most identified loci (71/78) were in close proximity to known genes or mRNA sequences, 50 of 78 were located in the 5′ region of a gene and 69 of 78 occurred within canonical CpG islands.

Figure 1.

RLGS analysis for tumor-associated DNA hypermethylation. (a) Representative RLGS loci for non-malignant TCL1-tg mouse spleen (NL) and specified TCL1-tg splenic B-cell tumors. Arrows indicate specific RLGS loci (4D57, 3C24 and 2C33) lost/hypermethylated in one or more of the tumors. (b) Frequency of altered RLGS loci for each tumor is indicated.

Table 1.

DNA methylation patterns in lymphomas of TCL1-tg mice

| Locus | LBL1 | LBL1a* | LBL1b* | LBL2 | LBL3 | LBL4 | LBL5 | LBL6 | DLBCL1 | DLBCL2 | DLBCL3 | MZL1 | MZL2 | Chromosome position of NotI |

Homology | GenBank accession number |

Gene context |

CpG island |

# of tumors* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C33 | 13:59285249 | Gas1 | NM_008086 | 5′ end | Yes | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 2F37 | X:55,560,988 | Sox3 | NM_009237 | 5′ end | Yes | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 3F56 | 12:46,129,739 | Foxg1 | NM_008241 | Body | Yes | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 4D57 | 4:28,999,648 | Epha7 | NM_010141 | Body | Yes | 10 | |||||||||||||

| 2E37 | 17:66,614,500 | mRNA | AK041052 | 5′ end | Yes | 9 | |||||||||||||

| 4G54 | 12:4,549,905 | mRNA | AK122572 | 5′ end | Yes | 9 | |||||||||||||

| 2C09 | 4:98,631,630 | Foxd3 | NM_010425 | 5′ end | Yes | 8 | |||||||||||||

| 2G50 | 12:64,004,021 | Mamdc1 | NM_207010 | 5′ end | Yes | 8 | |||||||||||||

| 3D03 | 2:63,953,750 | Fign | NM_021716 | 5′ end | Yes | 8 | |||||||||||||

| 2C14 | X:94,421,625 | - | - | - | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 3C09 | 9:88,074,776 | Tbx18 | NM_023814 | Body | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 3F33 | 16:96,463,991 | Hmg14 | NM_008251 | Body | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 4B16 | 2:68,327,187 | Stk39 | NM_016866 | 5′ end | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 4B22 | 5:130,774279 | mRNA | BC066072 | 5′ end | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 4B42 | 3:62,005,545 | mRNA | AK144976 | 5′ end | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 5B13 | 4:98,626,391 | EST | AV377040 | - | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 6D12 | 2:135,173,383 | mRNA | AK020944 | 5′ end | Yes | 7 | |||||||||||||

| 3B46 | 2:68,326,347 | Stk39 | NM_016866 | Body | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 3C10 | 2:84,412,897 | Zdhhc5 | NM_144887 | 5′ end | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 3C24 | 9:88,075,904 | Tbx18 | NM_023814 | 5′ end | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 3F09 | 3:44,840,447 | Pcdh10 | NM_011043 | 5′ end | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 4G73 | 8:90,392428 | Irx3 | NM_008393 | Body | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 5B21 | 13:101,510,565 | mRNA | AK032259 | Body | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 5C30 | 13:59284349 | Gas1 | NM_008086 | 5′ end | Yes | 6 | |||||||||||||

| 1D14 | 10:67,589,894 | Egr2 | NM_010118 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 1E19 | 4:13,670,306 | Mtg8 | AK032132 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 2B07 | 3:17,385,384 | Bhlhb5 | NM_021560 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 2F89 | 4:151,974,687 | EST | BI990953 | - | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 3B30 | 10:26,078,037 | mRNA | AK021041 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 4C11 | 16:14,160,631 | mRNA | AK016529 | Body | No | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 4D11 | 14:100,440,198 | Spry2 | NM_011897 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 4D26 | 10:18,242,971 | - | - | - | No | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 6C17 | 4:99,050,606 | Foxd3 | NM_010425 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 6D39 | 4:28,932,608 | Epha7 | NM_010141 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 6E07 | 6:61,148,968 | mRNA | BC107398 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 5D25 | 7:31,859,900 | Zfp537 | NM_172298 | 5′ end | Yes | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 1D16 | 7:31,861,437 | Zfp537 | NM_172298 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 1F21 | X:53,512,030 | Zic3 | NM_009575 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2C51 | 10:53,997,541 | mRNA | AK015334 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2D07 | 9:49,836,621 | Ncam1 | NM_010875 | Body | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2D17 | 13:47,861,015 | Id4 | NM_031166 | Body | No | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2E38 | 2:59,016,731 | Pkp4 | NM_026361 | Body | Yes | ||||||||||||||

| 42G09 | 10:9,548,064 | mRNA | AK087498 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2G14 | 6:23,885,534 | Cadps2 | NM_153163 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 2G35 | 10:33,679,565 | mRNA | AK169009 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3C27 | 2:74,353,577 | Evx2 | NM_007967 | 3′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3D67 | 4:130,910,515 | Oprd1 | NM_013622 | 3′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3F42 | 1:4,452,847 | Sox17 | NM_011441 | 3′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3F76 | 2:74,499,328 | Evx2 | BC061467 | 3′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3G102 | 2:144,624,936 | Slc24A3 | AF314821 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 4B11 | 2:139,192,068 | mRNA | AK077398 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 5E24 | 10:28928152 | mRNA | AK044134 | 5′ end | Yes | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 1F11 | 2:59,092,478 | Pkp4 | NM_026361 | 5′ end | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 2F12 | 18:51,332,715 | mRNA | AK046456 | 5′ end | No | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 2F72 | 15:64,073,819 | mRNA | BC011343 | 5′ end | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 2G48 | 12:106,919,086 | Tnfaip2 | NM_009396 | Body | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 3D63 | 12:97,914,635 | Golga5 | NM_013747 | 5′ end | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 3G118 | 17:33,998,698 | mRNA | AK138323 | Body | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 4D49 | 13:24,749,912 | Vmp | NM_009513 | 5′ end | No | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 5B27 | 10:28,927,390 | mRNA | BC066079 | Body | Yes | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 1F02 | 2:74,366,378 | Hoxd13 | NM_008275 | 5′ end | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 1F14 | 8:12371081 | Sox1 | NM_009233 | 5′ end | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 1G09 | 3:147,968,915 | mRNA | AK142828 | 5′ end | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 2E09 | 1:154,165,496 | - | - | - | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 2G05 | 5:148,345,311 | mRNA | AK160904 | 5′ end | No | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 3C06 | 1:15,470,447 | - | - | - | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 3G119 | 4:77,615,797 | Ptprd | AK034145 | 5′ end | Yes | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 1C10 | 19:38,537,602 | Tbc1d12 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 1F30 | 11:8,576,675 | mRNA | AK089717 | Body | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2D30 | 10:39,979406 | - | - | No | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2E10 | 6:24,898,673 | mRNA | AK087465 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2F21 | 10:5,634,072 | Esr1 | AK036627 | Yes | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3B15 | 13:31,173,603 | FoxC1 | NM_008592 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3D22 | 4:88,678261 | Cdkn2a | NM_001040654 | 3′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3D28 | 12:71,498,554 | Tmem30b | NM_178715 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3F14 | 2:140136,707 | mRNA | AK134694 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 4D27 | 6:52,127,688 | Hoxa2 | NM_010451 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5D43 | 2:76,250,275 | Osbp16 | NM_145525 | 5′ end | Yes | 1 |

Black squares denote RLGS fragments with decreased intensity of >50%. Tumor diagnosis and RLGS scoring is listed and includes two daughter tumors (LBL1a and b) from adoptive transfer of parental LBL1 tumor cells into syngeneic mice. NotI position lists chromosome followed by position based on UCSC BLAT search (Aug. 2005 Freeze). For gene context, 5′ end indicates location directly upstream or within first exon, 3′ end indicates location within the last exon of a gene, body indicates within gene itself excluding 5′ and 3′ ends.

Daughter tumors are excluded from calculations of total tumors showing fragment loss. EST, expressed sequence tag.

Adoptive transfer of TCL1-tg LBL1 tumor cells into syngeneic mice results in the development of a phenotypically identical splenic lymphomas within 6 weeks (Hoyer et al., 2002). When the RLGS profiles of two of these daughter tumors (LBL1a and LBL1b) were compared with their LBL1 parental tumor, 1735 of the 1741 RLGS loci (99.6%) were identical (Table 1 and data not shown), indicating tumor-specific DNA methylation was stable for over 2 months (three weeks in culture and 6 weeks in syngeneic animals).

Validation of tumor-specific methylation detected by RLGS

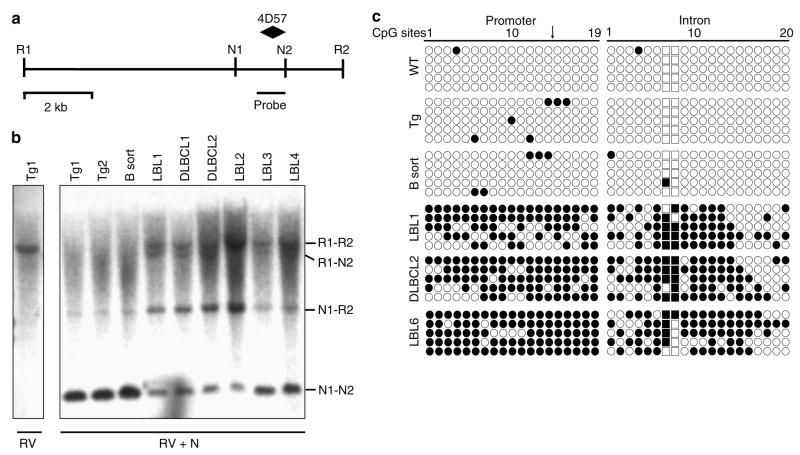

The 4D57 locus localized to a CpG island within the gene Epha7, a member of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases. Eph receptors and their ligands are capable of modulating immune cell function and development through diverse effects on receptor signaling, lymphocyte chemotaxis and adhesion (Wu and Luo, 2005). We chose to focus our attention on Epha7 owing to its frequent hypermethylation (Table 1) and the potential to influence the growth and spread of aggressive TCL1-tg B-cell tumors. Although loss of an RLGS fragment is usually due to DNA hypermethylation (Costello et al., 2000), it may also result from point mutation or genomic deletion. Therefore, confirmatory Southern analysis was performed on 4D57 and was designed to assess the methylation status of two distinct NotI sites (Figure 2a). Increased methylation of one or both NotI sites was seen for all tumors, as demonstrated by protection from NotI enzymatic digestion (Figure 2b). When compared with non-malignant samples, the tumors showed a marked reduction in intensity of the 1.3 kb lower band (both NotI sites unmethylated) and an inverse increase in the 7.2 or 3.1 kb middle bands (owing to methylation of either the first or second NotI site, respectively) and 8.9 kb upper band (both NotI sites methylated).

Figure 2.

Validation of promoter methylation for Epha7. (a) Schematic diagram of genomic EcoRV–EcoRV fragment (sites R1 and R2) of murine Epha7 containing two NotI sites (N1 and N2), as well as locations of the 4D57 NotI-HinfI RLGS fragment and Southern probe. (b) Southern hybridization for Epha7 on genomic DNA from non-malignant TCL1-tg spleens (Tg) or sorted B-cells (B sort) and malignant B-cell tumors. Digestions with EcoRV alone (first lane, RV) or in combination with methyl-sensitive NotI (remaining lanes, RV+N1) are indicated. Detected bands correspond to methylation of neither (N1–N2), both (R1–R2) or one of two NotI sites (R1–N2 or N2–R2). (c) Bisulfite sequence analysis of CpG islands located in the 5′ UTR and first intron of Epha7. Each row represents the sequence of an individual clone (open circle, unmethylated CpG site; filled circle, methylated site; squares, CpGs in the NotI site of the 4D57 locus; arrow, location of translational start site).

To further validate RLGS results and obtain a detailed picture of DNA methylation across associated CpG islands, bisulfite sequencing was performed on the frequently lost 4D57, 3F09 and 5B13 loci (corresponding to the genes Epha7, Pcdh10 and Foxd3, respectively). As the NotI site for 4D57 is located within the first intron of Epha7, bisulfite sequencing was also performed on a second region covering the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and translational start site of Epha7. Both Epha7 regions were highly methylated in tumors compared with non-malignant spleens or sorted B-cells (Figure 2c). Likewise, bisulfite sequencing of the Pcdh10 promoter showed an average of 0.3 methylated CpG sites (1.7%) out of 17 CpG sites per clone for non-malignant spleen, and 10.8 methylated CpG sites (63%) out of 17 CpG sites per clone for tumor LBL1 (10 clones sequenced for each, data not shown). Bisulfite sequencing of the Foxd3 promoter showed an average of 0.6 methylated CpG sites (5%) out of 12 CpG sites per clone for non-malignant spleen and 7.1 methylated CpG sites (59%) out of 12 CpG sites per clone for tumor LBL1 (10 clones sequenced for each, data not shown).

Silencing of specific hypermethylated genes in TCL1-tg tumors

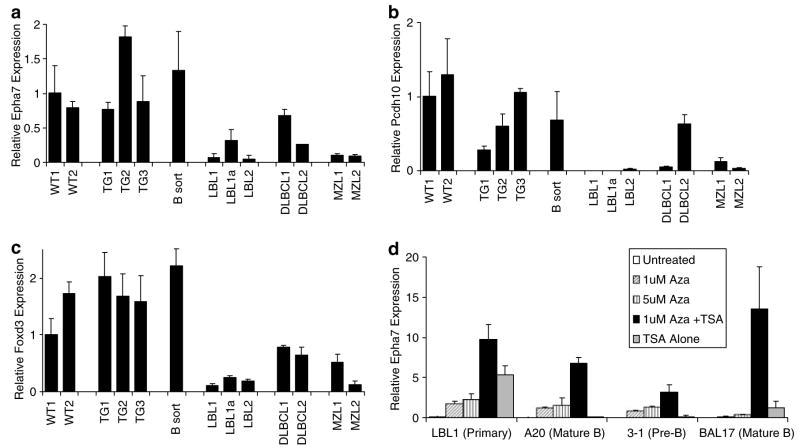

To determine whether DNA methylation correlated with gene silencing, expression of Epha7, Pcdh10 and Foxd3 were analysed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Figure 3a–c). When compared with sorted non-malignant B-cells, tumors with DNA hypermethylation at 4D57 had a 3- to 34-fold reduction in Epha7 expression, whareas one tumor (DLBCL1) without hypermethylation at 4D57 showed a less significant twofold reduction in expression (Figure 3a). Likewise, expression of Pcdh10 and Foxd3 in tumors was reduced 5–240-fold and 3–20-fold, respectively (Figure 3b and c). Epha7 expression was found to be comparatively low in established murine pre-B (3–1) and mature B-cell lines (A20 and BAL17). To further validate the epigenetic regulation of Epha7 expression, these cell lines or cultured primary TCL1-tg LBL1 cells were treated with the DNA demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) alone or in combination with the histone deacetylase inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA). Dose-dependent induction of Epha7 expression was seen in response to 5-aza-dC, with further substantial induction of Epha7 with the addition of TSA (Figure 3d), thus supporting epigenetic silencing of Epha7 in these malignant B-cells through combined DNA methylation and histone deacetylation.

Figure 3.

Gene silencing with increased promoter methylation in TCL1-tg lymphomas. Expression of Epha7 (a), Pcdh10 (b) or Foxd3 (c) in non-malignant wild-type spleens (WT), TCL1-tg spleens (Tg) or sorted B-cells (B sort), as well as in TCL1-tg B-cell tumors (LBL, DLBCL and MZL), were quantified by real-time PCR. (d) Real-time PCR analysis of Epha7 expression in cultured primary LBL1 tumor cells and murine B-cell lymphoma lines (A20, 3–1 and BAL17) before or after treatment with 5-aza-20-deoxycytidine (Aza) and/or 100 nM TSA.

Silencing and hypermethylation of EPHA7 in human B-cell lymphomas

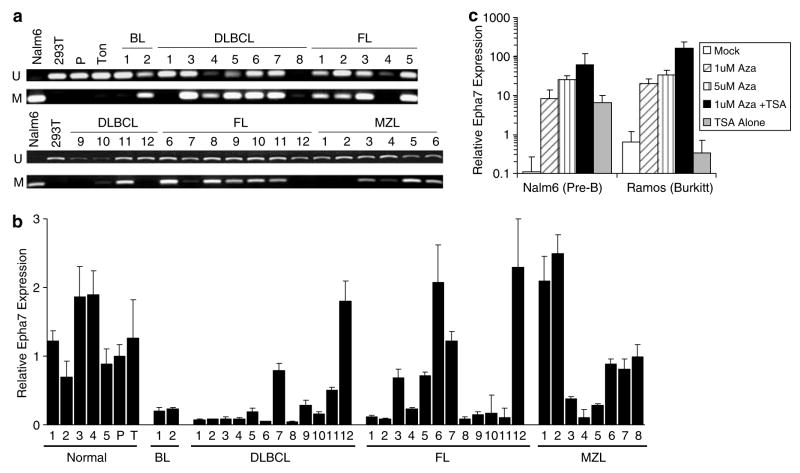

We next evaluated EPHA7 promoter methylation and gene expression in normal human lymphoid tissue and lymphomas. Primary human GC-NHL, including Burkitt lymphoma (BL), DLBCL, follicular lymphoma (FL) and MZL were chosen, paralleling lymphomas seen in TCL1-tg mice. Methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) analyses of DNA from normal human hyperplastic lymph nodes and tonsils demonstrated strong unmethylated bands and absent methylated bands for the EPHA7 promoter (Figure 4a). Similar results were obtained with the human embryonic kidney cell line 293T, consistent with a previous report (Wang et al., 2005). In contrast, MS-PCR demonstrated methylation of the EPHA7 promoter in 23of the 31 informative patient lymphoma samples and the human pre-B-cell line, Nalm-6 (Figure 4a). By real-time PCR, the majority of lymphoma samples showed a 4–20-fold reduction in EPHA7 expression when compared to DNA prepared from pooled hyperplastic lymph nodes, whereas each individual hyperplastic lymph node sample showed no significant reduction in EPHA7 expression (Figure 4b). In some instances, EPHA7 silencing did not appear to correlate with DNA hypermethylation (DLBL7, FL3, FL5, FL6 and MZL6), possibly owing to accompanying non-malignant lymphocytes in these samples. EPHA7 expression did not show any correlation with TCL1 expression status as determined by real-time PCR (data not shown). Robust induction of EPHA7 expression in human B-cell lines Nalm-6 or Ramos following 5-aza-dC treatment alone or in combination with TSA provided additional support for epigenetic silencing of EPHA7 in human B-cell neoplasms (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Promoter methylation and gene expression of EPHA7 in human lymphomas. (a) Methyl-specific PCR was performed on Nalm-6 or 293T cell lines, a pool of 5 non-malignant hyperplastic human lymph nodes (P), reactive tonsil (T) and primary human GC-NHL samples including Burkitt lymphomas (BL), DLBCL, follicular lymphomas (FL) and MZL. Upper and lower bands correspond to PCR products amplified by primers specific to unmethylated (U) or methylated (M) CpG sites following bisulfite conversion. (b) EPHA7 expression was measured by real-time PCR for the above samples, including each individual hyperplastic lymph node (N1–N5) from the pooled lymph nodes. (c) Real-time PCR analysis of EPHA7 from Nalm-6 and Ramos before or after treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Aza) and/or 100 nM TSA.

Normal B and T lymphocytes express and secrete a truncated form of EphA7 protein

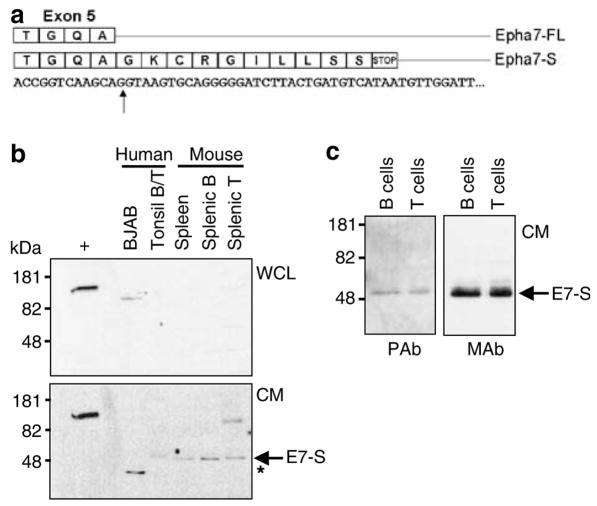

A previous study using semi-quantitative reverse transcription RT–PCR and Northern analysis shows that EPHA7 is expressed by fetal bone marrow pro-B and pre-B-cells, but not by more mature fetal B-lineage or adult B-lineage cells (Aasheim et al., 1997). Given the differences in primers used in this prior and our current study (covering the 3′ versus 5′ end of the full-length gene, respectively), we explored the possibility of an alternate EPHA7 transcript and found a variant fulllength 3.5-kb murine Epha7 mRNA (AK032973) entry in GenBank. This alternate transcript encompasses the first five exons of full-length Epha7 with read-through/termination in the fifth intron. It is predicted to encode a 451 amino acid, N-terminal truncated form of EphA7 protein comprising most of its extracellular domain, but lacking the transmembrane and intracellular domains (Figure 5a). PCR, using primers to the 5′ and 3′ ends of AK032973, was performed and successfully amplified a 3.5 kB product from murine splenic B-cell cDNA. This PCR product was cloned, sequenced and found to be identical to AK032973 (data not shown).

Figure 5.

A variant transcript of EPHA7 encodes EphA7-S, a soluble protein secreted by lymphocytes. (a) Nucleotide sequence and predicted amino acid sequence for full-length EphA7 (EphA7-FL) at the end of exon 5 (arrow-splice site) and for the variant transcript (EphA7-S) based on sequencing of a cDNA clone from murine splenic B-cells. (b) EphA7 expression was determined by Western blot (polyclonal antibody) on WCL or serum-free CM from the human B-cell line BJAB, sorted normal human tonsil B or T cells, normal murine whole splenocytes and sorted normal murine splenic B or T cells. WCL from Nalm-6 cells stably transfected with EphA7-FL served as a positive control (+). Arrow indicates EphA7-S (E7-S), asterisk indicates unidentified immunoreactive band in BJAB CM. (c) Western blots on CM from sorted normal human tonsil B or T cells using rabbit polyclonal (PAb) or rat monoclonal (MAb) antibodies against the extracellular domain of EphA7.

EphA7 Western blots on whole cell lysates from sorted B and T cells from both mouse spleens and human tonsil failed to detect full-length EphA7 protein, as expected (Figure 5b). In contrast, Western blots on conditioned media (CM) from these same cells detected a 50-kDa band (Figure 5b), consistent with translation of the 3.5-kb variant transcript and secretion of the protein (which we now designate as EphA7-S) by the cells. Two different antibodies recognizing the extracellular domain of EphA7 detected the same 50-kDa protein in CM from sorted B or T cells from human tonsil (Figure 5c). A distinct 40-kDa band was also detected in CM from the human Burkitt line BJAB (Figure 5b). Although the exact identity of this 40-kDa band was not determined, a previous study reports multiple EPHA7 transcripts (6.0, 4.4 and 2.0 kb) in BJAB cells by Northern blot, as well as nucleotide deletions in a sequenced EPHA7 cDNA clone from the same cells (Aasheim et al., 1997).

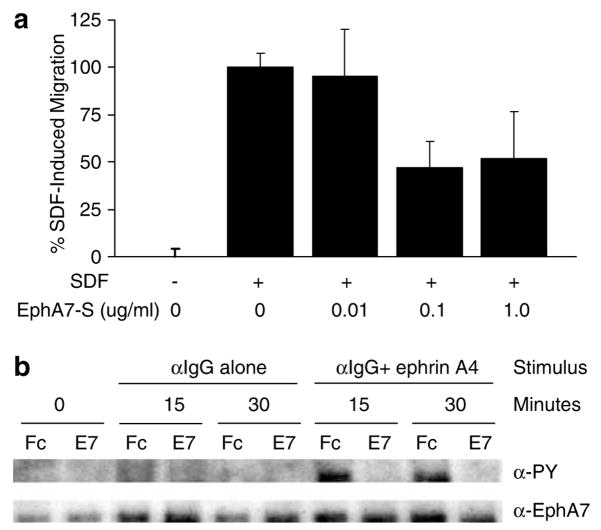

Soluble EphA7 partially inhibits chemokine-induced B-cell migration

Eph/ephrin signaling is known to alter chemokine-induced lymphocyte chemotaxis (Sharfe et al., 2002), which prompted us to ask whether soluble EphA7 could influence B-lymphocyte chemotaxis in a transwell migration assay. To test this possibility, Nalm-6 B-cells were allowed to migrate to SDF-1α with or without preincubation with EphA7-Fc, a purified recombinant protein comprising the first 549 amino acids of the extracellular domain of EphA7. SDF-1α-induced migration was partially blocked by EphA7-Fc in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.03for 0.1 or 1.0 μg/ml EphA7-Fc versus SDF alone, Student’s t-test) (Figure 6a). Eph/ephrin signaling has also been shown to influence T-cell proliferation and apoptosis (Wu and Luo, 2005). However, flow cytometric studies with Annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI) staining showed that soluble EphA7-Fc had no effect on apoptosis induced by IgM B-cell receptor ligation in the Ramos B-cell line (data not shown). Soluble EphA7-Fc also had no effect on the proliferation of Nalm-6 or Ramos B-cell lines at varying serum concentrations (1–10%), as measured by MTT assays (data not shown).

Figure 6.

EphA7-S inhibits B-cell migration and ephrin ligand-induced EphA7 phosphorylation. (a) Nalm-6 B-cells (2×105 cells/well) were migrated for 2 h through a 5 μM pore membrane to recombinant SDF-1α (100 ng/ml), with or without pre-incubation with recombinant soluble EphA7-Fc (EphA7-S). Data is expressed as percentage of cells migrating to SDF-1α alone (typically 15–20% of input cells). All conditions were performed in triplicate. One of four representative experiments is shown. (b) EphrinA4-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of EphA7-FL expressing Nalm-6 cells was measured either in the presence of soluble EphA7-Fc or Fc alone. Cells were stimulated for indicated time, after which whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-EphA7 antibody followed by Western blot with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, then re-probed with anti-EphA7 to verify equal total EphA7-FL in each well.

Soluble EphA7 blocks ephrin-A4-mediated activation of full-length EphA7 receptor

Eph receptors and their cognate membrane-bound ephrin ligands interact at sites of direct cell–cell contact to initiate bidirectional signaling in both receptor- and ligand-expressing cells (Holmberg and Frisen, 2002; Palmer and Klein, 2003; Pasquale, 2005). Binding of clustered ephrin-A ligands to the full-length EphA7 receptor results in phosphorylation of its intracellular kinase domain, initiating a signaling cascade that results in cell repulsion (Holmberg et al., 2000). This prompted us to ask whether soluble EphA7 can affect ephrinA ligand-induced activation of full-length Eph receptor. We used recombinant ephrin-A4 ligand to stimulate Nalm-6 cells stably transfected with full-length EphA7, either in the presence or absence of soluble EphA7. Ephrin-A4 effectively initiated EphA7 phosphorylation, and this phosphorylation was completely inhibited by co-incubation with soluble EphA7 (Figure 6b). Thus, soluble EphA7 is capable of disrupting full-length EphA7 receptor signaling initiated through ephrin ligand/Eph receptor clustering and activation.

Discussion

Using RLGS, we identified 115 DNA hypermethylation events in B-cell lymphomas from TCL1-tg mice. Between 0.6 and 3.9% of all RLGS loci were hypermethylated in each TCL1-tg lymphoma, a frequency comparable with previous RLGS studies of human leukemia and mouse hematologic malignancies (Rush et al., 2001, 2004; Yu et al., 2005). Certain tumors showed a much higher frequency of methylation compared to others in our sample set, suggesting that tumor progression for a subset of these lymphomas may be critically dependent on DNA hypermethylation, akin to the subsets of sporadic colorectal tumors with CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (Kondo and Issa, 2004).

The nonrandom distribution of DNA methylation identified by RLGS points to a characteristic methylation pattern for B-cell lymphomas and expands on prior work describing distinct patterns of methylation for leukemias or lymphomas (Esteller, 2003b). Recently, RLGS was used to study DNA hypermethylation in an Il15 transgenic mouse model of T/natural killer (NK) cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Yu et al., 2005). Many of the tumor-associated DNA hypermethylation changes detected in those leukemias are identical to those found in this study of GC B-cell lymphomas, suggesting that a common methylation profile may be shared by distinct hematologic malignancies. Common epigenetic alterations could act to reinforce a pre-existing lymphoid-specific developmental pattern of gene expression and/or serve to dysregulate specific subsets of genes with critical roles in lymphomagenesis.

TCL1-tg mice provide unique models of mature B-lymphoid tumorigenesis, distinct from most other genetic, viral or environmental manipulations of mice that typically give rise to more immature forms of lymphoma (Teitell, 2005). TCL1 overexpression in the transgenic mice alone is insufficient for tumor development, indicating a need for additional critical molecular alterations. Therefore, genes that are targets of DNA hypermethylation and silencing in the TCL1-tg mouse model are potential tumor suppressor genes with importance in mouse and possibly human GC-NHL. Indeed, we were able to show parallel DNA hypermethylation and silencing of EPHA7 in human GC-NHL. EphA7 is a member of the largest known subgroup of receptor tyrosine kinases, the Eph receptors, that interact with membrane-anchored ephrin ligands to initiate bidirectional signaling in both receptor- and ligand-expressing cells (Pasquale, 2005). Eph/ephrin signaling is dependent upon cell–cell interaction and influences a variety of biological processes including tissue morphogenesis, angiogenesis, neural plasticity, stem cell fate and immune cell function (Pasquale, 2005).

Altered expression of various ephrin ligands and Eph receptors occurs in a variety of cancers, with diverse effects on tumor growth, survival, metastasis and angiogenesis. EPHA7 is highly upregulated in hepato-cellular and lung carcinomas (Surawska et al., 2004). Conversely, EPHA7 is a target of DNA hypermethylation and silencing in colorectal cancer (Wang et al., 2005). To our knowledge, our results are the first to show that EPHA7 is a target of hypermethylation and silencing in mature B-cell lymphomas. Earlier reports indicate that EPHA7 is not expressed in peripheral B lymphocytes (Aasheim et al., 1997; de Saint-Vis et al., 2003). However, our findings are not inconsistent with these prior studies, for RT–PCR primers used in prior studies would not have amplified the variant EphA7-S transcript described here. Of note, alternatively spliced mRNAs for murine Epha7 are detected by Northern blot with a probe to the 50 end of full-length Epha7, including a faint 3.5-kb transcript in mouse spleen (Ciossek et al., 1995). Likewise, a survey of normal human tissues by TaqMan PCR reveals EPHA7 expression across a wide range of tissue types, with low to intermediate levels of EPHA7 transcript found in spleen, using primers that cover the EphA7-S transcript (Hafner et al., 2004).

Our finding that murine and human peripheral lymphocytes secrete a truncated form of EphA7 is not without precedent. Aasheim et al. (2000) describe a splice variant of ephrinA4, which encodes a soluble protein secreted by B-cells and upregulated upon B-cell receptor ligation. Truncated Eph receptors retaining their ligand-binding capacity have been shown to block activation of the full-length receptor (Brantley et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2003; Dobrzanski et al., 2004). Accordingly, we found that recombinant soluble EphA7 blocked ephrinA4-induced EphA7-FL phosphorylation in vitro. Given its promiscuity for various ephrin-A ligands (Gale et al., 1996), it is intriguing to hypothesize that EphA7 secreted by lymphocytes might act as a decoy to block EphA receptor-ephrinA ligand clustering and activation. In this manner, soluble EphA7 could influence lymphocyte chemotaxis and trafficking by inhibiting Eph/ephrin interaction and signaling between adjacent lymphocytes or other neighboring cells (i.e., dendritic cells, macrophages or endothelium). Indeed, we demonstrated that soluble EphA7 partially blocked the chemotaxis of Nalm-6 B-cells in vitro, presumably by disrupting endogenous EphA/ephrin-A signaling between these cells. Blocking soluble EphA7 secretion may abrogate its inhibitory activity on cell migration, thus enhancing tumor cell spread and recruitment of accessory cells able to promote tumor growth. As increased expression and activation of full-length Eph receptors may be a common feature of tumors with more aggressive or metastatic potential (Wimmer-Kleikamp and Lackmann, 2005), epigenetic silencing of EPHA7 may serve to promote tumor aggressiveness by eliminating the inhibitory activity of secreted EphA7 on tumor-promoting EphA receptor signaling.

Materials and methods

Tumor samples and cell lines

The TCL1-tg mouse model has been described (Hoyer et al., 2002) and is covered in greater detail in Supplementary methods. Human tissue and tumors were obtained from the UCLA Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory in accordance with institutional guidelines and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Nalm-6 were provided by D Rawlings, whereas all other human and mouse lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Correction (ATCC). LBL1 cells were cultured from a TCL1-tg mouse with lymphoblastic lymphoma (Hoyer et al., 2002). For CM, cells were rinsed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and allowed to condition serum-free media for 24 h, which was concentrated 100-fold by Centriprep filter centrifugation (10 kDa cutoff, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). See Supplementary Information for details regarding mouse and human lymphocyte isolations, chemotaxis assays and drug treatments.

Nucleic acid isolation and RLGS

RNA and DNA were isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA for RLGS was isolated from snapfrozen mouse spleens and RLGS was performed as described previously (Costello et al., 2002). Tumor RLGS profiles were analysed by superimposing films against a background profile generated on sorted, non-malignant splenic B-cells (see below). Spot loss or decreased intensity of at least 50% was scored as ‘spot loss’ or hypermethylation event.

Southern blot

Genomic DNA (10 μg/sample) was digested with EcoRV and NotI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to positively charged nylon membrane. The Southern probe was generated by digesting the 4D57 RLGS clone with NotI and ScaI to generate an 872 bp Epha7 genomic fragment, which was then random-prime labeled with α[P32]dCTP.

Real-time PCR

For first strand cDNA synthesis, 2 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with random hexamer primers using the Superscript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). SYBR green real-time quantitative PCR assays were performed using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) 7700 sequence detector. Amplification reactions were carried out in 20 μl with cDNA, 300 nM forward/reverse primers and 10 μl of 2 × SYBR green master mix. Reaction parameters were 50°C for 5 s, 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s. Samples were analysed in parallel for 36B4 expression, which served as the normalization control. The human primers were: hEPHA7 forward (F) (5′-TACCCCGATACGAACATACCAG-3′), hEPHA7 reverse (R) (5′-AGGAAGACTGTTACAATCCCTCA-3′), h36B4 F (5′-TCG-AACACCTGCTGGATGAC-3′) and h36B4 R (5′-CCCGCTGCTGAACATGCT-3′). The murine primers were mEPHA7 F (5′-TCAAACTCGGTTCCCTTCGTGGAT-3′), mEPHA7 R (5′-AGA-AATCCAGTTAGTCCGCAGCCA-3′), m36B4 F (5′-AGATGCAGCAGATCCGCAT-3′) and m36B4 R (5′-GTTCTTGCCCATCAGCACC-3′). Other primer sequences are available upon request.

Bisulfite sequencing and MS-PCR

For bisulfite sequencing, PCR reactions of 35 cycles were performed (primers available upon request) on sodium bisulfite-treated DNA. PCR products were separated on agarose gels, extracted and cloned into pCR2.1 Topo vector (Invitrogen). Individual clones were then sequenced. MS-PCR for the human EPHA7 promoter was performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2005). Primer sets amplified a 229-bp product located at the same genomic site (forward primers located at −432 to −413and reverse primers located at −223 to −204, relative to the translational start site).

Western blot and phosphorylation analysis

For EphA7 Western blots, CM (10 μg per sample) or RIPA whole cell lysates (50 μg per sample) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), transferred to membranes, incubated overnight with 1:1000 anti-Epha7 antibody (rabbit polyclonal K16, Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); or rat monoclonal clone 88712, R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA)) and then 1 h with 1:5000 horse radish peroside (HRP)-linked secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). For phosphotyrosine analysis, FL-EphA7-expressing Nalm-6 cells (2.5×106 cells/condition, see supplemental methods for details regarding generation of FL-EphA7-expressing Nalm-6 cells) were stimulated at 37°C for the indicated times with anti-IgG-crosslinked recombinant human ephrin-A4 (amino acids 1–171 of ephrin-A4 fused to the Fc region of human IgG1, R&D Systems) or anti-IgG alone in the presence of soluble recombinant EphA7 protein (amino acids 1–549 of the extracellular domain of mouse EphA7 fused to Fc) or recombinant Fc itself (R&D Systems). All proteins and anti-IgG were used at final concentrations of 40 μg/ml. Cells were rinsed 2× in cold PBS, lysed in radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer and lysates (equalized for volume and protein concentration) were incubated overnight at 4°C with monoclonal anti-Epha7 antibody. Next, samples were bound to Protein G-Plus agarose beads for 2 h, washed thrice in RIPA buffer, boiled, resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10, Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA, USA). Equal immunoprecipitation of Epha7 protein was verified by reprobing the same blot with anti-Epha7 antibody.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH Grants T32CA009120 (DWD), T32A107126 (RRS) T32CA09056 (SWF), HD041451 (YM), PNEY018228, R01CA90571, R01CA107300 and R01GM073981 (MAT), by the Margaret E Early Medical Research Trust, by CMISE, a NASA URETI Institute (NCC2-1364) (MAT) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (HCM). MAT is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- Aasheim HC, Munthe E, Funderud S, Smeland EB, Beiske K, Logtenberg T. A splice variant of human ephrin-A4 encodes a soluble molecule that is secreted by activated human B lymphocytes. Blood. 2000;95:221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aasheim HC, Terstappen LW, Logtenberg T. Regulated expression of the Eph-related receptor tyrosine kinase Hek11 in early human B lymphopoiesis. Blood. 1997;90:3613–3622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichi R, Shinton SA, Martin ES, Koval A, Calin GA, Cesari R, et al. Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia modeled in mouse by targeted TCL1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6955–6960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102181599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley DM, Cheng N, Thompson EJ, Lin Q, Brekken RA, Thorpe PE, et al. Soluble Eph A receptors inhibit tumor angiogenesis and progression in vivo. Oncogene. 2002;21:7011–7026. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, Brantley D, Fang WB, Liu H, Fanslow W, Cerretti DP, et al. Inhibition of VEGF-dependent multistage carcinogenesis by soluble EphA receptors. Neoplasia. 2003;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciossek T, Millauer B, Ullrich A. Identification of alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding variants of MDK1, a novel receptor tyrosine kinase expressed in the murine nervous system. Oncogene. 1995;10:97–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello JF, Fruhwald MC, Smiraglia DJ, Rush LJ, Robertson GP, Gao X, et al. Aberrant CpGisland methylation has non-random and tumour-type-specific patterns. Nat Genet. 2000;24:132–138. doi: 10.1038/72785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello JF, Smiraglia DJ, Plass C. Restriction landmark genome scanning. Methods. 2002;27:144–149. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saint-Vis B, Bouchet C, Gautier G, Valladeau J, Caux C, Garrone P. Human dendritic cells express neuronal Eph receptor tyrosine kinases: role of EphA2 in regulating adhesion to fibronectin. Blood. 2003;102:4431–4440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzanski P, Hunter K, Jones-Bolin S, Chang H, Robinson C, Pritchard S, et al. Antiangiogenic and antitumor efficacy of EphA2 receptor antagonist. Cancer Res. 2004;64:910–919. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-3430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Cancer epigenetics: DNA methylation and chromatin alterations in human cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003a;532:39–49. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0081-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Profiling aberrant DNA methylation in hematologic neoplasms: a view from the tip of the iceberg. Clin Immunol. 2003b;109:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M, Gaidano G, Goodman SN, Zagonel V, Capello D, Botto B, et al. Hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and survival of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:26–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Holland SJ, Valenzuela DM, Flenniken A, Pan L, Ryan TE, et al. Eph receptors and ligands comprise two major specificity subclasses and are reciprocally compartmentalized during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1996;17:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galm O, Herman JG, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetics in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood Rev. 2006;20:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner C, Schmitz G, Meyer S, Bataille F, Hau P, Langmann T, et al. Differential gene expression of Eph receptors and ephrins in benign human tissues and cancers. Clin Chem. 2004;50:490–499. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Civin CI, Issa JP, Collector MI, Sharkis SJ, Baylin SB. Distinct patterns of inactivation of p15INK4B and p16INK4A characterize the major types of hematological malignancies. Cancer Res. 1997;57:837–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Clarke DL, Frisen J. Regulation of repulsion versus adhesion by different splice forms of an Eph receptor. Nature. 2000;408:203–206. doi: 10.1038/35041577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Frisen J. Ephrins are not only unattractive. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer KK, French SW, Turner DE, Nguyen MT, Renard M, Malone CS, et al. Dysregulated TCL1 promotes multiple classes of mature B-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14392–14397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212410199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT – the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U, Dalla-Favera R. New insights into the phenotype and cell derivation of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;294:31–49. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29933-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Issa JP. Epigenetic changes in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:29–39. doi: 10.1023/a:1025806911782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narducci MG, Pescarmona E, Lazzeri C, Signoretti S, Lavinia AM, Remotti D, et al. Regulation of TCL1 expression in B- and T-cell lymphomas and reactive lymphoid tissues. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2095–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A, Klein R. Multiple roles of ephrins in morphogenesis, neuronal networking, and brain function. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1429–1450. doi: 10.1101/gad.1093703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–475. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush LJ, Dai Z, Smiraglia DJ, Gao X, Wright FA, Fruhwald M, et al. Novel methylation targets in de novo acute myeloid leukemia with prevalence of chromosome 11 loci. Blood. 2001;97:3226–3233. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush LJ, Plass C. Alterations of DNA methylation in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2002;185:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush LJ, Raval A, Funchain P, Johnson AJ, Smith L, Lucas DM, et al. Epigenetic profiling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals novel methylation targets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2424–2433. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said JW, Hoyer KK, French SW, Rosenfelt L, Garcia-Lloret M, Koh PJ, et al. TCL1 oncogene expression in B-cell subsets from lymphoid hyperplasia and distinct classes of B-cell lymphoma. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1–10. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharfe N, Freywald A, Toro A, Dadi H, Roifman C. Ephrin stimulation modulates T cell chemotaxis. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3745–3755. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3745::AID-IMMU3745>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen RR, Ferguson DO, Renard M, Hoyer KK, Kim U, Hao X, et al. Dysregulated TCL1 requires the germinal center and genome instability for mature B-cell transformation. Blood. 2006;108:1991–1998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawska H, Ma PC, Salgia R. The role of ephrins and Eph receptors in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:419–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitell M, Damore MA, Sulur GG, Turner DE, Stern MH, Said JW, et al. TCL1 oncogene expression in AIDS-related lymphomas and lymphoid tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9809–9814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitell MA. The TCL1 family of oncoproteins: co-activators of transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:640–648. doi: 10.1038/nrc1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kataoka H, Suzuki M, Sato N, Nakamura R, Tao H, et al. Downregulation of EphA7 by hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:5637–5647. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer-Kleikamp SH, Lackmann M. Eph-modulated cell morphology, adhesion and motility in carcinogenesis. IUBMB Life. 2005;57:421–431. doi: 10.1080/15216540500138337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Luo H. Recent advances on T-cell regulation by receptor tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:292–297. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000166497.26397.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan XJ, Albesiano E, Zanesi N, Yancopoulos S, Sawyer A, Romano E, et al. B-cell receptors in TCL1 transgenic mice resemble those of aggressive, treatment-resistant human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11713–11718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604564103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Liu C, Vandeusen J, Becknell B, Dai Z, Wu YZ, et al. Global assessment of promoter methylation in a mouse model of cancer identifies ID4 as a putative tumor-suppressor gene in human leukemia. Nat Genet. 2005;37:265–274. doi: 10.1038/ng1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.