Abstract

Polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) is a widely expressed RNA binding protein. In the nucleus PTB regulates the splicing of alternative exons, while in the cytoplasm it can affect mRNA stability, translation, and localization. Here we demonstrate that PTB transiently localizes to the cytoplasm and to protrusions in the cellular edge of mouse embryo fibroblasts during adhesion to fibronectin and the early stages of cell spreading. This cytoplasmic PTB is associated with transcripts encoding the focal adhesion scaffolding proteins vinculin and alpha-actinin 4. We demonstrate that vinculin mRNA colocalizes with PTB to cytoplasmic protrusions and that PTB depletion reduces vinculin mRNA at the cellular edge and limits the size of focal adhesions. The loss of PTB also alters cell morphology and limits the ability of cells to spread after adhesion. These data indicate that during the initial stages of cell adhesion, PTB shuttles from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and influences focal adhesion formation through coordinated control of scaffolding protein mRNAs.

Polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB or hnRNP I) is a widely expressed RNA binding protein with an affinity for pyrimidine-rich RNA sequences that have clusters of CUC and UCU triplets (1, 45). It is predominantly localized to the nucleus, where it controls programs of alternative splicing regulation during neuronal and muscle differentiation (5, 6, 15). However, PTB is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein with several reported functions in cytoplasmic mRNA metabolism, including effects on mRNA stability, translation, and localization (42). For example, glucose stimulation of pancreatic beta cells can induce redistribution of PTB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and promote PTB binding to the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs for insulin and other proteins involved in insulin secretion (29). These PTB-bound messages exhibit enhanced stability, allowing increased insulin production (17, 29, 46). Export of PTB to the cytoplasm has also been reported during viral infection and during cell stress, such as hypoxia (2, 18, 24, 43). Under such conditions, cap-dependent translation is inhibited, while PTB-bound viral or cellular mRNAs can be translated via cap-independent mechanisms (2, 18, 24, 43).

We previously reported that activation of the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway and the phosphorylation of PTB serine 16 by PKA induce its redistribution to the cytoplasm (48). PKA activation was also shown to induce PTB relocalization and neurite outgrowth in the neuronal PC12 cell line, where PTB was found to bind to the 3′ UTR of actin mRNA (34). It was proposed that PTB directed the localization of actin mRNA to growth cones (34). Exons controlled by nuclear PTB are often derepressed by the downregulation of PTB during muscle and neuronal differentiation (5, 6). These exons are especially common in proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement and protein trafficking. However, the relationship between the nuclear and cytoplasmic functions of the PTB protein is not yet clear.

The localization of an mRNA allows synthesis of its encoded protein at a restricted position in the cytoplasm. This process plays important roles in locally regulating gene expression in neurons and in the germ line (36). One of the best-characterized examples of mRNA localization in somatic cells is the β-actin mRNA (10). Singer and colleagues have shown that the mRNA for β-actin is localized to the leading edge of migrating chicken embryo fibroblasts (28, 31, 41). This mRNA localization requires specific sequence elements within the β-actin 3′ UTR, called zipcode sequences, and a specific set of proteins, including the zipcode binding protein (ZBP1) (16, 22, 28). This system allows the local synthesis of the actin protein at sites where the cytoskeleton is being actively remodeled to push the edge of the cell forward.

A role for PTB in mRNA localization was discovered in studies of early development. The localization of Vg1 mRNA to the vegetal cortex of Xenopus oocytes requires PTB as well as the Vg1-RBP/Vera protein (homologous to chicken ZBP1) (11). PTB binds to the cis-acting VM1 motif (YYUCU), a site in the 3′ UTR of Vg1 mRNA that is required for its localization. Most recently, the Drosophila homolog of PTB was found to be essential to the proper localization of Oskar mRNA at the posterior pole of Drosophila oocytes (3). Oocytes carrying a mutation in PTB show delayed localization of oskar mRNA and a loss of translational repression during the localization process. Despite the clear implication of PTB in the localization of mRNAs in oocytes and the similarities of these processes to actin mRNA localization, the role of PTB in somatic cell mRNA localization has not been studied. PTB is predominantly nuclear under standard cell culture conditions, and any role in the cytoplasm is likely to be transient.

Mann and colleagues reported that several primarily nuclear RNA binding proteins colocalize with focal adhesion proteins in the cytoplasm of freshly adhering cells (12). The nuclear RNA binding proteins hnRNP K, hnRNP E1, and FUS/TLS were found to relocalize to structures called spreading initiation centers (SICs) that form transiently at the cell periphery during adhesion and early cell spreading (12). It was suggested that SICs were sites for localized rapid synthesis of focal adhesion proteins. Neither PTB nor specific mRNAs were identified in SICs, but PTB was reported as one of several RNA binding proteins associating with the focal adhesion protein paxillin in an adhesion-dependent manner (12).

In this report, we show that PTB is relocalized from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and the cell periphery during early cell adhesion to fibronectin. During adhesion, cytoplasmic PTB is associated with mRNAs for focal adhesion scaffolding proteins, and PTB is needed for proper mRNA localization and cell spreading. These data demonstrate a role for PTB in focal adhesion formation and the control of cytoskeletal functions, such as cell migration and attachment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents.

The immortalized RelA−/− (19) and vinculin−/− (49) mouse embyro fibroblast (MEF) cell lines, wild-type MEFs (CRL-2752; ATCC), and simian virus 40 (SV40)-transformed MEFs were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Primary MEFs were isolated on embryonic days 12.5 to 14.5, following the protocol outlined previously (47). HEK293 and HeLa cells were grown in DMEM-10% FBS. Antibodies used in the study were anti-PTB full-length (FL) polyclonal, anti-PTB (NT) polyclonal (6), anti-PTB (CT) polyclonal (6), anti-PTB (BB7) monoclonal (44), anti-nPTB (neuronal homolog) polyclonal (6), anti-vinculin monoclonal (Sigma), anti-Raver1 (5D5) monoclonal (50), anti-Sam68 polyclonal (Upstate), anti-hnRNP K monoclonal, anti-Myc (Santa Cruz), antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) (Santa Cruz), and beta-actin (Novus).

The short hairpin shPTB(A) in the BLS vector was described previously (6). The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) shPTB(B) was generated by synthesizing the oligonucleotide CGCGTCCCCGCAGTTGGAGTGACCTTACTTCAAGAGAGTAAGGTCACTTCAGCTGCTTTTTGGAAAT. A reverse complement having MluI/ClaI overhangs was annealed to this sequence. The annealed fragment was cloned into the MluI/ClaI-digested LV THM vector (Addgene) expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The Myc-tagged PTB expression construct was described previously (48). The EGFP expression vector was from Clontech.

Cell adhesion.

MEFs were incubated for 15 min in 2 ml Hanks'-based enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer (Gibco). Cells were lifted by adding 8 ml serum-free DMEM and pipetting up/down repeatedly, vortexed for 3 s to dissociate clumps, and placed on a rotator at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 7 ml DMEM with 10% FBS by pipetting up/down, and vortexed for 3 s. Resuspended cells (0.5 ml) were added to fibronectin (human plasma fibronectin; Gibco)-coated coverslips (25 μg/ml) in a six-well plate with 1 ml medium (DMEM with 10% FBS).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 min, and incubated with primary antibody for 1 h and with Alexa Fluor 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Coverslips were mounted on slides using the ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen).

Image acquisition.

Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4-numerical-aperture oil objective lens, pinhole setting at 1 μm. Analysis was performed using Zeiss LSM Image Examiner software (v. 4.2).

UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation.

MEFs adhered for 20 min were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-5 mM MgCl2 and UV irradiated in a UV Stratalinker 1800 UV cross-linker (Stratagene) on ice with lid off. UV cross-linking was with 200 J/m2. Cells from four 15-cm plates were scraped in 2 ml cold PBS, pelleted, and resuspended with 150 μl of LSB (low-salt buffer) (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 100 U RNaseOUT [Invitrogen], and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitors [Roche]) and placed on ice for 5 min to swell cells. Cells were lysed on ice for 5 min after addition of 75 μl of 0.2 M sucrose-1% NP-40 in LSB (final concentration of sucrose was 66.6 mM, with 0.33% NP-40). Tubes were spun for 5 min at full-speed microcentrifugation at 4°C and the supernatant used for immunoprecipitation (IP). Lysates were precleared for 1 h with 100 μl Dynabeads. IP was 3 h with anti-HA or anti-PTB (NT) cross-linked Dynabeads preincubated with 100 μg/ml yeast tRNA (100 μl of beads covalently cross-linked to the Dynabeads according to the manufacturer's protocol). IP beads were washed 2× with lysis buffer (LSB with 66 mM sucrose and 0.33% NP-40) containing 150 mM NaCl, 2× with high-salt buffer (lysis buffer with 500 mM NaCl), and 2× with lysis buffer containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate. Proteinase K was used to treat the IP, phenol-chloroform extracted, and precipitated RNA. cDNA synthesis with random hexamer primers using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was carried out according to the supplier's protocol. Primers used for PCR were as follows: beta-actin, GCTGCGTTTTACACCCTTTC (forward) and GTTTGCTCCAACCAACTGCT (reverse); Src, ACTGTGTGCGCAGAACTGTC (forward) and CACTGTACCAGCCTCCACCT (reverse); paxillin, ATCCACCAATGGAAACTGGA (forward) and GTGAGGTGCTGGCTCTTAGG (reverse); vinculin, CAGAGTCACTGGGGTGTTAT (forward) and ATGCAGCACTTCAGCTCAGA (reverse); alpha-actinin 4, TGTGCCCCAGAGATACCTTC (forward) and CTATGGCAGGTCCTCTGCTC (reverse).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Transcripts (75 nucleotides) shown in Fig. 7 corresponding to the 3′UTR of vinculin having the two CU repeats were synthesized with T7 polymerase as described previously (44). Transcripts were gel purified, labeled with P32, and incubated with HeLa nuclear extract for 30 min. Antibodies were added to supershift RNA protein complexes, which were resolved by electrophoresis on 8% denaturing urea polyacrylamide gels and subsequently visualized by scanning on a Typhoon phosphorimager.

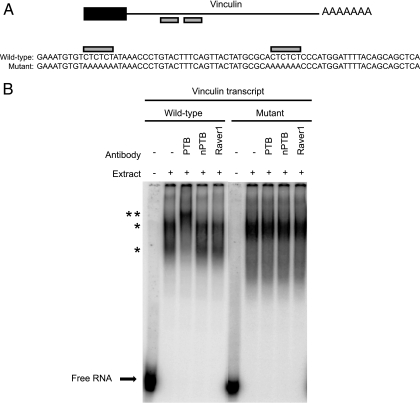

FIG. 7.

PTB binds CU repeats in the 3′ UTR of vinculin transcript. (A) Schematic showing potential PTB binding sites in the 3′ UTR of mouse vinculin mRNA. The black box indicates the carboxy-terminal coding region, the black line indicates the 3′ UTR, and the gray boxes highlight CU repeats. Transcripts synthesized for PTB binding experiments are shown below the schematic. Wild-type transcript corresponding to the CU repeat region (gray boxes) of the vinculin mRNA and a mutant transcript in which the CU repeats were changed to AA repeats are shown. (B) EMSA analysis of wild-type and mutant vinculin transcripts in HeLa nuclear extract. Labeled transcript was incubated with HeLa nuclear extract for 30 min and then incubated with the indicated antibodies to supershift RNA/protein complexes. Free RNA is shown at the bottom of the gel. A single asterisk identifies shifted RNP complexes, and the double asterisk identifies antibody-supershifted complexes.

Riboprobe synthesis.

In vitro transcription reactions from a PCR fragment of the vinculin 3′ UTR were carried out with aminoallyl UTP (Sigma) according to Ambion's published protocol. Primers used to generate vinculin 3′ UTR PCR fragments as templates for the in vitro transcription reactions were as follows: riboprobe 3, ATTGCTGCAGGAAAAAGTGG (forward) and GTGGCATGGTAAAAACAGAAA (reverse); riboprobe 5, TGTGTCAGCCTGTTAGCTCCT (forward) and TTTTCCCTAGAAGCACCAGAAG (reverse). Purified transcripts were conjugated to a fluorophore, either Cy3 or Cy5 monoreactive dye (GE Amersham), according to the protocol outlined by GE Amersham. One dye molecule per every 30 nucleotides (about five to seven dye molecules per riboprobe) was incorporated.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Cells or coverslips were washed with PBS-5 mM MgCl2, fixed with 4% PFA, and permeabilized with 70% ethanol overnight. Hybridization was carried out with 30 ng of labeled riboprobe, 8 μl freshly prepared deionized formamide, 4 μl of 20 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 4 μl 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and H2O to 32 μl. Probe was heated at 70°C for 10 min and then chilled on ice. Eight μl of 50% dextran sulfate was added, and 20 μl was spotted on a glass slide; an air-dried coverslip was placed on top and sealed with rubber cement, followed by incubation in a sealed humidified chamber in the dark at 45°C for 4 h or overnight. Washes were carried out with 2× SSC at room temperature for 15 min, 2× SSC-0.1% NP-40-10% deionized formamide for 30 min at 50°C, 0.1× SSC-0.1% NP-40 at 50°C for 30 min, and then 0.1× SSC-0.1% NP-40 for 30 min at 50°C if needed (as determined by nonspecific staining of the probe in the vinculin null cells). Coverslips were rinsed with 2× SSC, rinsed with PBS, rinsed with H20, and then mounted on slides as described above.

Immunofluorescence with FISH.

Cells were fixed with 4% PFA prepared with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated PBS. The immunofluorescence protocol was as described above, except the PBS used throughout was DEPC treated. For blocking and for incubation with primary antibodies, 50 mg/ml Ultrapure bovine serum albumin (Ambion) was used. After secondary antibody incubation, cells were washed with PBS and postfixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, washed with DEPC-treated 2× SSC several times, and then proceeded with FISH as described above.

RESULTS

PTB relocalizes to the cytoplasm during cell adhesion and early spreading.

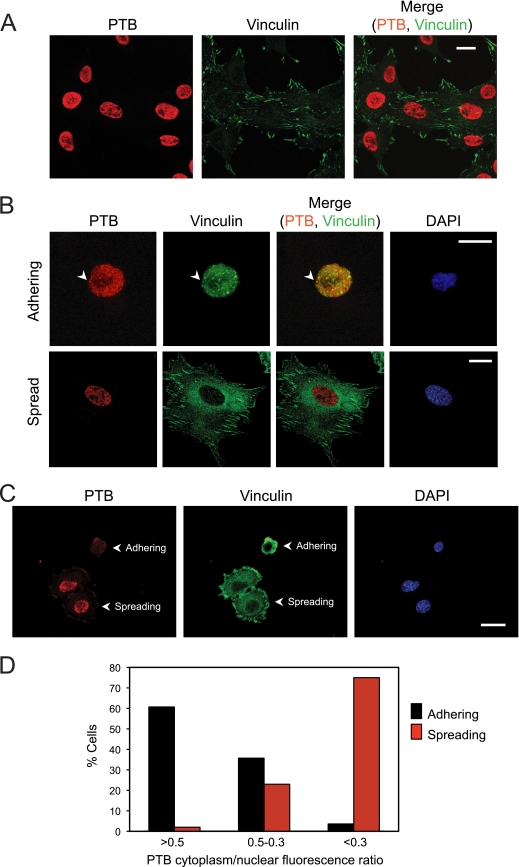

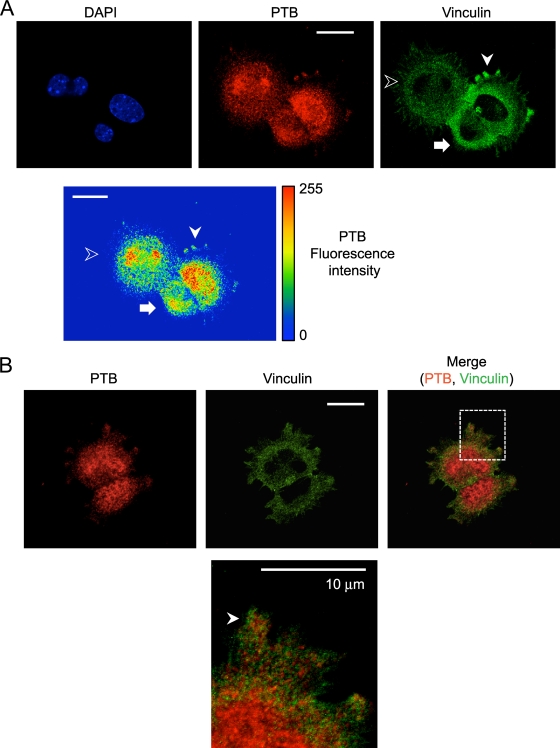

Several RNA binding proteins are seen to relocalize from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during adhesion of fibroblasts to fibronectin (12). In typical monolayer cell cultures, PTB is more than 90% nuclear as measured by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). We examined whether PTB might also relocalize to the cytoplasm after detachment from the substrate and readhesion to fibronectin. Immortalized MEFs were nonenzymatically detached from the substrate by pipetting in serum-free cell dissociation buffer (Gibco). Cells were maintained in suspension for 1 h to dissociate focal complexes, resuspended in serum-containing medium, allowed to adhere on fibronectin, and processed for immunocytochemistry. Newly adhering cells lacking focal adhesions displayed punctate vinculin staining throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). As these cells adhered and spread, they developed classical elongated focal adhesions. We observed a striking relocalization of PTB to the cytoplasm of the early-adhering cells (Fig. 1B). Once cells have formed focal adhesions and extended processes, they again exhibit the typical distribution of high nuclear and low cytoplasmic levels of PTB (Fig. 1B and C). Quantifying the total PTB fluorescence, we found that 60% of the early-adhering cells had a cytoplasm-to-nucleus PTB ratio greater than 0.5 (Fig. 1D). In contrast, after the cells had begun to develop focal adhesions and were actively spreading, more than 70% showed a cytoplasm-to-nucleus PTB ratio of less than 0.3 (Fig. 1D). In the early-adhering cells, some of the cytoplasmic PTB colocalized with vinculin in punctate structures that were possibly the previously described SICs (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). However, much of the PTB and vinculin protein in the cytoplasm did not colocalize, and other vinculin puncta were PTB negative. Interestingly, in cells that had adhered and were beginning to spread, PTB was observed within protrusions forming at the cell periphery (Fig. 2A). Vinculin protein was also observed in these protrusions but did not precisely colocalize with PTB. Instead, the two proteins were found mostly in separate but closely adjacent regions within a protrusion (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 1.

PTB relocalizes from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during adhesion. (A) MEFs were plated on fibronectin. After 24 h, the cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies to PTB and vinculin. (B) MEFs were lifted, maintained in suspension for 1 h, and replated on fibronectin. Cells were allowed to adhere for 12 min (adhering) or 90 min (spread). Nonadhered cells were removed by washing, cells were fixed, and immunofluorescence was performed with antibodies to PTB and vinculin. The arrowhead shows PTB vinculin colocalization at a possible SIC. (C) MEFs adhered for 15 min were fixed and immunofluorescence performed with anti-PTB and antivinculin antibodies. Adhering cells were identified by an absence of focal adhesions (punctate vinculin staining in the cytoplasm), and spreading cells were identified by the presence of focal adhesions at the cell periphery. (D) The mean fluorescence intensity for PTB across the nucleus and the cytoplasm was determined for both adhering and spreading cells using Zeiss image analysis software. Cells were grouped as having a PTB cytoplasm-to-nucleus ratio of either >0.5, 0.5 to 0.3, or <0.3 (n = 56 for adhering and n = 47 for spreading). Magnification, ×40 (A) or ×63 (B and C). Scale bars, 20 μm.

FIG. 2.

PTB localizes to cell protrusions during early cell spreading. MEFs were fixed after 20 min of adhesion to fibronectin and immunostained with antibodies to PTB and vinculin. (A) An adhering cell is indicated by the arrow, and an early spreading cell with PTB in protrusions is indicated by the white arrowhead. A more fully spread cell with elongated focal adhesions is indicated with the unfilled arrowhead. The heat map shows the fluorescence intensity of the PTB. (B) The arrowhead in the enlarged image in the bottom panel indicates a protrusion with PTB staining adjacent to vinculin staining. Scale bars, 20 μm, except the enlarged image in panel B (10 μm).

We tested several PTB antibodies to monitor PTB relocalization during MEF adhesion to fibronectin. Antibodies raised to the full-length PTB protein (anti-PTB FL), to the amino-terminal peptide of PTB (anti-PTB NT), or to the carboxy terminus of PTB (anti-PTB CT) all show PTB to be mostly nuclear in fully spread MEFs (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). All three PTB antibodies detect increased cytoplasmic PTB during adhesion of MEFs to fibronectin (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). In addition to wild-type immortalized MEFs, we also tested primary MEFs and an SV40-transformed MEF cell line, as well as other immortalized MEF cell lines (RelA−/− and vinculin−/− cells). We observed PTB relocalization to the cytoplasm and protrusions during adhesion and spreading in all these cells (data not shown). In contrast, the transformed cell lines HEK293 and HeLa did not show PTB movement to the cytoplasm during adhesion (data not shown). These cell lines were also reported not to form SICs by de Hoog et al. (12).

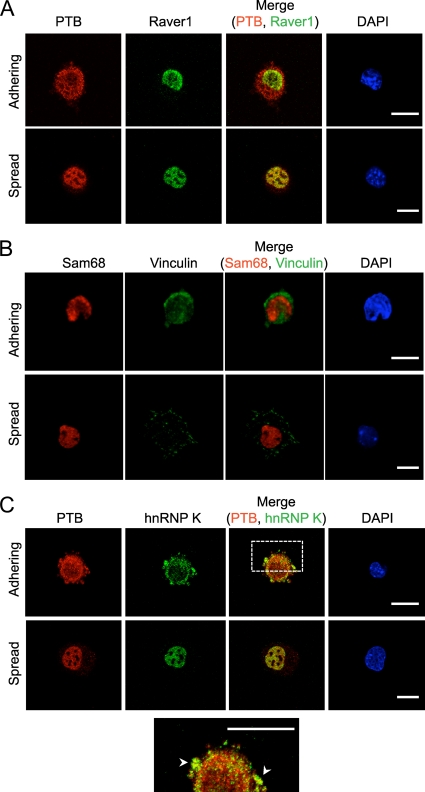

hnRNP K also relocalizes during cell adhesion.

To examine if other shuttling RNA binding proteins also relocalize during MEF adhesion, we tested Raver1, Sam68, and hnRNP K (Fig. 3A to C). All three proteins are predominantly nuclear in typical cell monolayers. Raver1 is an RRM protein known to interact with both PTB and vinculin and acts as a cofactor with PTB in repressing splicing of some exons (21, 25, 27). Sam68 is a KH-domain RNA binding protein with previously described functions both in the nucleus, where it affects alternative splicing, and the cytoplasm, where it affects mRNA translation and interacts with Src tyrosine kinase (7, 33). HnRNP K is a KH-domain RNA binding protein implicated in control of translation of specific mRNAs (4, 38). HnRNP K has also been found within the cytoplasm and in SICs of adhering MRC5 lung fibroblasts (12). Similarly to PTB, hnRNP K redistributed to the cytoplasm during cell adhesion (Fig. 3C). We also observed partial colocalization between PTB and hnRNP K in cytoplasmic protrusions of adhering and spreading cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast to PTB and hnRNP K, both Raver1 and Sam68 remained almost entirely nuclear during cell adhesion (Fig. 3A and B). Sam68 has been reported to associate with focal adhesion proteins during adhesion (12). However, we did not detect its relocalization during adhesion in MEFs.

FIG. 3.

hnRNP K, but not Raver1 or Sam68, relocalizes to the cytoplasm during cell adhesion. MEFs were lifted and maintained in serum-free medium on a rotator for 1 h at 37°C and then replated on fibronectin-coated coverslips in the presence of serum. Cells were incubated for 15 min (adhering) or overnight (spread), fixed, and immunostained with antibodies to Raver1 and PTB (A), Sam68 and vinculin (B), or PTB and hnRNP K (C). Adhering cells were identified by cytoplasmic staining for PTB (A and C) or by punctate vinculin staining (B). The expanded view at the bottom shows a partial overlap between PTB and hnRNP K in the cytoplasm and periphery. Arrowheads indicate regions of colocalization. Scale bars, 20 μm.

PTB depletion decreases the size of focal adhesions and alters the morphology of the cell periphery.

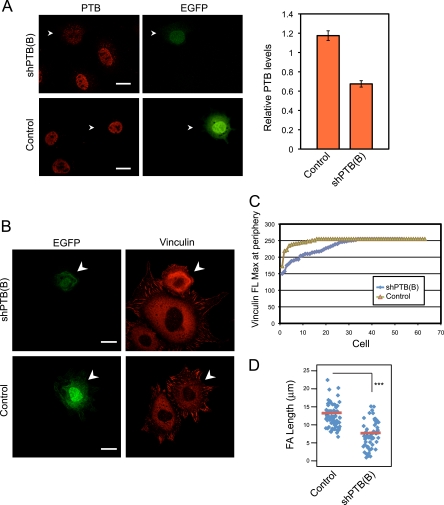

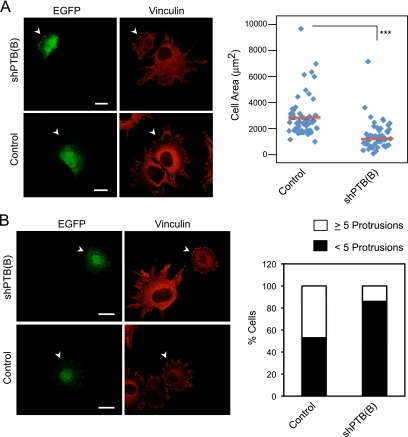

We depleted PTB with a specific shRNA to examine its effect on focal adhesion formation. ShPTB(B) was expressed from a vector also expressing EGFP, allowing identification of transfected cells. This shRNA reduced the PTB level by 40% in MEFs (Fig. 4A). This depletion of PTB was accompanied by decreased vinculin staining at the cell periphery (Fig. 4B and C). The average focal adhesion length was also significantly decreased in PTB-depleted cells (Fig. 4B and D). PTB depletion also reduced the surface area of the cells, indicating a decrease in cytoplasmic spreading (Fig. 5A). Finally, cells lacking PTB displayed a rounder shape, which was quantifiable as a reduction in the number of protrusions extending from the cellular edge (Fig. 5B). To control for off-target effects, we also tested a different shRNA [shPTB(A)] to PTB. MEFs transfected with shPTB(A) also showed a rounded cell shape and less cell spreading (see Fig. S2A to C in the supplemental material). Thus, PTB is needed for proper development of cellular protrusions and focal adhesion formation during cell spreading.

FIG. 4.

PTB knockdown decreases vinculin levels at the cell periphery and decreases the size of vinculin-containing focal adhesions. (A) MEFs were transfected either with empty vector (control) or with vector expressing a short hairpin targeting PTB [shPTB(B)]. After 3 days, cells were fixed and stained with anti-PTB antibody. The arrowhead indicates a green fluorescent protein-positive transfected cell. Scale bars, 20 μm. The mean fluorescence for PTB in the nucleus was measured for transfected and nontransfected cells from the same optical fields. The mean ratio of PTB fluorescence in transfected cells relative to that in nontransfected cells is plotted in the graph ± standard errors of the means [control, n = 72; shPTB(B), n = 65]. (B) MEFs transfected as for panel A were lifted and allowed to readhere to fibronectin for 90 min. The cells were fixed and stained for vinculin. Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive transfected cells. The shPTB(B)-transfected cells display less vinculin staining at the periphery and smaller focal adhesions. Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) The vinculin staining at the cell periphery of control and PTB knockdown cells was quantified using Zeiss image analysis software, and the maximum vinculin fluorescence (FL Max) at the periphery for each cell was plotted. Each data point represents a single cell examined. (D) Length of the longest focal adhesion (FA) for each cell was measured and the results displayed as a scatter plot. The red bar shows the mean, and asterisks indicate statistical significance measured by a paired t test (***, P < 0.0001). The numbers of cells measured are as follows: control, n = 63; shPTB(B), n = 52.

FIG. 5.

PTB knockdown decreases the cell area and number of protrusions formed during spreading. The extent of cell spreading and protrusion formation in MEFs treated as for Fig. 4B was compared between PTB knockdown and control cells. (A) Arrowheads indicate a green fluorescent protein-positive transfected cell. The cell surface area was measured using Zeiss image analysis software and data displayed as a scatter plot. For the control, n = 53; for shPTB(B), n = 51. The red bar in the plot shows the mean, and asterisks indicate statistical significance measured by paired t test (***, P < 0.0001). (B) Cells were also scored for number of protrusions formed during spreading. The panel on the left shows shPTB(B)-transfected cells with fewer protrusions than nontransfected cells or control-transfected cells. Arrowheads indicate a green fluorescent protein-positive transfected cell. The graph on the right shows the percentage of transfected cells having five or more protrusions or fewer than five protrusions [n = 53 for the control; n = 51 for shPTB(B)]. Scale bars, 20 μm.

We also tested the effect of increasing PTB expression on cell morphology and spreading. Surface area measurements of cells transfected with a PTB expression construct showed a clear increase in size compared to controls (P < 0.0002) (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). However, PTB overexpression did not affect focal adhesion size. Thus, increasing or decreasing the PTB protein level alters the rate of cell spreading on fibronectin in opposite directions.

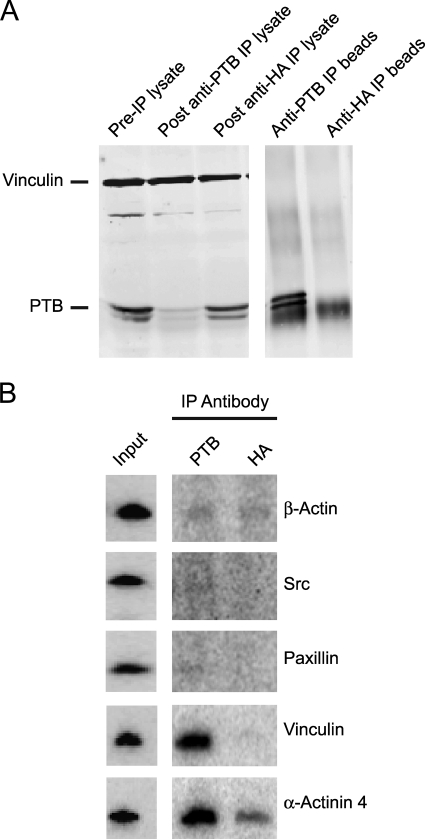

Transcripts encoding focal adhesion scaffolding proteins associate with PTB.

We next wanted to identify transcripts associating with PTB in the cytoplasm of adhering and early-spreading cells. Briefly adhered cells were subjected to UV irradiation to cross-link proteins to bound mRNAs. The cytoplasmic fraction of the cells was isolated, and PTB with cross-linked RNA was immunoprecipitated (Fig. 6A). We assayed for a variety of transcripts in the immunoprecipitate by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), including mRNAs for proteins involved in focal adhesion formation. Interestingly, both vinculin and alpha-actinin 4 mRNAs were detected in the PTB immunoprecipitates, whereas mRNAs encoding other focal adhesion proteins were not (Fig. 6B). We also detected mRNA for talin in PTB immunoprecipitates, but only in the RelA−/− immortalized MEFs (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Transcripts encoding focal adhesion scaffolding proteins associate with PTB in the cytoplasm of adhering cells. MEFs were lifted and maintained in suspension for 1 h, replated on fibronectin, and allowed to adhere for 20 min. Nonadhered cells were removed by washing. The remaining cells were UV irradiated to cross-link protein to RNA, the cytoplasmic fraction was isolated, and IP was performed with either anti-PTB or anti-HA control antibody. RNA in the immunoprecipitate was isolated, cDNA synthesized, and RT-PCR performed using primers for various focal adhesion protein transcripts. (A) Western blot for PTB and vinculin in the cell lysate and the IP. (B) RT-PCR for various focal adhesion transcripts using cDNA prepared from the IPs. Input is from cDNA prepared from RNA isolated from the pre-IP lysate.

Vinculin and alpha-actinin 4 are both scaffolding proteins that are typically deposited early during formation of focal adhesions (40). Both mRNAs have multiple CU repeat elements in their 3′ UTRs that may act as PTB binding sites (Fig. 7A and data not shown). Binding of PTB to the CU repeats in the vinculin transcript was examined by EMSA using a portion of the vinculin 3′ UTR containing two CUCUCU elements and a mutant vinculin transcript with the CUCUCU elements modified to AAAAAA (Fig. 7A). The wild-type vinculin RNA probe was incubated in a HeLa nuclear extract containing abundant PTB. This generated two RNP complexes that shifted upward in the gel from the free RNA probe (Fig. 7B). These complexes were supershifted by the PTB antibody but not by other antibodies, indicating the presence of PTB in the complex (Fig. 7B). Mutation of the potential PTB binding sites in the probe resulted in a different spectrum of complexes that were not supershifted by the PTB antibody (Fig. 7B). We conclude that PTB can directly associate with the CUCUCU elements in the vinculin 3′ UTR.

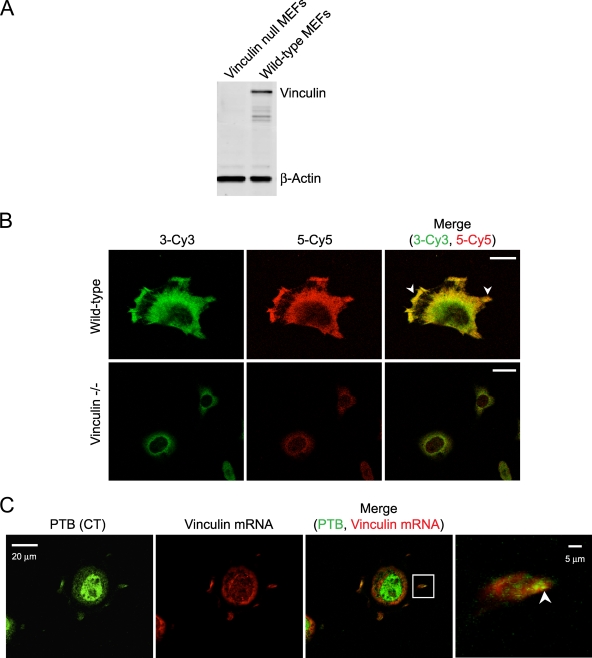

Vinculin mRNA is localized at the cell periphery with PTB during cell spreading.

MEFs transfected with the PTB shRNAs did not show an obvious decrease in total vinculin staining (Fig. 4B). However, PTB depletion in spreading MEFs led to less vinculin protein at the cell periphery (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that PTB may affect the spatial regulation of vinculin mRNA translation or the recruitment of the vinculin protein to the periphery. Since the PTB protein localized to newly forming protrusions at the cell periphery (Fig. 2), we asked whether PTB may affect the localization of vinculin mRNA during early cell spreading. To observe the vinculin mRNA in spreading cells, we performed FISH. Several RNA probes spanning the 3′ UTR of the vinculin transcript were tested for hybridization in wild-type and vinculin null MEFs. Two of the probes showed specific hybridization in the wild-type MEFs but not in vinculin null control cells (Fig. 8A and B). The overlap of the signal for these two probes was nearly complete. Both probes (riboprobes 3 and 5) detected vinculin mRNA at the cell periphery and specifically within protrusions and the leading edge of MEFs spread on fibronectin (Fig. 8B). Thus, vinculin mRNA localizes to cytoplasmic protrusions and the leading edge of spreading MEFs.

FIG. 8.

Vinculin mRNA colocalizes with PTB to the cell periphery of spreading fibroblasts. (A) Western blot for vinculin and beta-actin in wild-type and vinculin null MEFs shows an absence of vinculin protein in the null cells. (B) Wild-type and vinculin null MEFs were fixed with 4% PFA, and in situ hybridization was performed with two riboprobes specific to different regions of the 3′ UTR of vinculin mRNA. Riboprobe 3 was Cy3 labeled, and riboprobe 5 was Cy5 labeled. The arrowheads identify vinculin mRNA localization to protrusions and cell periphery. (C) Cells allowed to adhere for 20 min were fixed and immunofluorescence performed with anti-PTB (CT) antibody. Cells were postfixed with PFA, and in situ hybridization was performed with Cy3-labeled vinculin riboprobes 3 and 5 combined. The arrowhead in the enlarged image identifies regions of colocalization in newly formed protrusions. Scale bars, 20 μm except in the enlarged images to the right in panel C (5 μm).

To examine whether vinculin mRNA and the PTB protein colocalize during early cell spreading, in situ hybridization for vinculin mRNA was combined with immunofluorescence for the PTB protein. Although there were regions where the mRNA and protein showed independent signals, there was significant overlap at the cell periphery (Fig. 8C; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Notably, there were many overlapping pixels within cell protrusions as they began to form (Fig. 8C; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The Manders overlap coefficient of 0.9 (determined using Zeiss image analysis software) indicates significant colocalization of the PTB protein with vinculin mRNA in new protrusions.

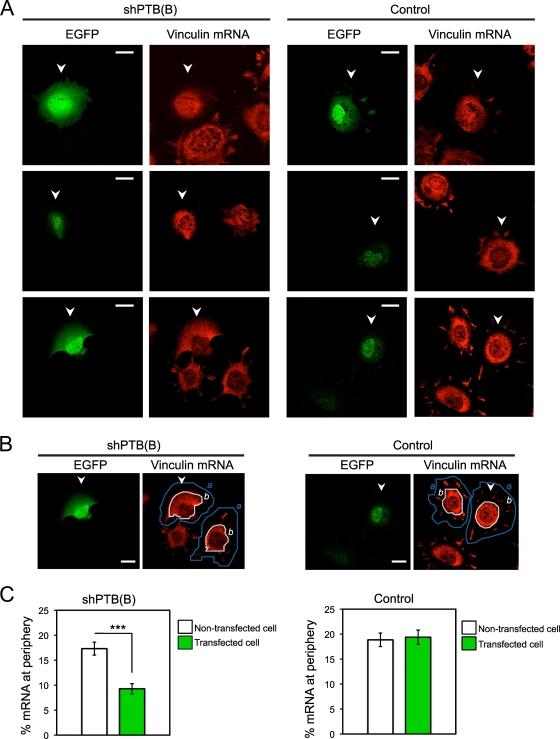

To determine if PTB affects the targeting of vinculin mRNA to the cellular edge, we depleted PTB with shPTB(B). Cells expressing the shRNA were identified by EGFP fluorescence. As seen previously, PTB depletion reduced the number of cell protrusions (Fig. 9A). Significantly, the level of vinculin mRNA was low in the limited protrusions seen in these cells, and the vinculin mRNA detected at the cell periphery was reduced compared to that in cells transfected with control empty vector (Fig. 9B and C). Thus, PTB is needed for vinculin mRNA localization to the cellular edge and for proper spreading of cells.

FIG. 9.

PTB knockdown decreases localization of vinculin mRNA to the cell periphery. (A) MEFs were transfected with shPTB(B) or empty vector (control). After 3 days, cells were replated on fibronectin and allowed to adhere for 90 min as described previously. FISH was performed using vinculin-specific probes (riboprobes 3 and 5 combined). Shown are representative images from three independent experiments of knockdown and control cells hybridized with labeled vinculin transcript. Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive transfected cells. (B) Vinculin mRNA fluorescence signal at the outer regions of transfected and nontransfected cells in the same optical field was quantitated as follows: total fluorescence for a cell (a, fluorescence total within the area outlined by the blue line) and the total fluorescence within the main cell body (b, fluorescence total within the area outlined by the white line) were calculated, and the percentage of mRNA localizing to the cell peripheral region was then calculated as (a − b)/a. This calculation was performed for a transfected cell and a nontransfected cell in the same optical field. Arrowheads indicate GFP-positive transfected cells. Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) The data show the means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments [for shPTB(B), n = 60 nontransfected and transfected cells; for control, n = 60 nontransfected and transfected cells). The asterisks indicate statistical significance measured by a paired t test (***, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

We find that the RNA binding protein PTB plays a role in focal adhesion formation during the early stages of cell adhesion and spreading. As cells attach and spread along a fibronectin substrate, both PTB and hnRNP K transiently relocalize from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Depletion of PTB reduces cell spreading and limits the formation of protrusions in the cellular edge. We further find that PTB is bound to mRNAs encoding several focal adhesion scaffolding proteins, including vinculin, and partially colocalizes with vinculin mRNA at the cell periphery. Loss of PTB reduces the size of vinculin stained focal adhesions in actively spreading cells.

PTB and vinculin mRNA are both present in new protrusions formed during the rapid cell spreading which occurs upon cell adhesion. But the vinculin protein and mRNA remain in these protrusions after PTB has returned to the nucleus. This differs from the localization and translation of β-actin mRNA at the leading edge of migrating fibroblasts (10, 14). β-Actin mRNA localization is controlled by the proteins ZBP1 and ZBP2, which bind to a 54-nucleotide region of the actin 3′ UTR. Like PTB, ZBP2 is primarily a nuclear protein. However, ZBP1 exhibits a long-lasting localization with the actin mRNA in lamellipodia as the cells migrate, in contrast to the brief localization seen for PTB early during adhesion and spreading. The continuous localization of the β-actin mRNA may reflect the continuous synthesis of this protein in the extending lamellipodia. PTB apparently acts transiently, perhaps to help initiate adhesion and spreading.

It was recently shown for developing Drosophila embryos that mRNAs exhibit a wide variety of localization patterns (32). The rules governing the localization and induced translation of specific messages in somatic cells will likely prove similarly complex. Cellular mRNAs assemble into complex mRNP structures containing many different RNA binding proteins, leading to a variety of translational control profiles. In addition to vinculin, PTB binds to the focal adhesion protein mRNAs for α-actinin and talin (data not shown), and there are many other mRNAs containing likely PTB binding sites in their 3′ UTRs. Conversely, different pools of a particular mRNA may assemble with different groups of proteins to address different synthetic needs. Indeed, only a fraction of the vinculin mRNA is localized to sites of focal adhesion assembly, and only a fraction colocalizes with PTB. It will be interesting to compare the proteins in the peripherally localized vinculin mRNPs with mRNPs showing a more diffuse distribution through the cytoplasm.

Although PTB and hnRNP K both relocalize during cell attachment to fibronectin, they apparently play different roles in this process. Depletion of PTB decreases the size of vinculin-containing focal adhesions and the number of protrusions seen along the cellular edge during spreading. In contrast, de Hoog et al. (12) showed that interfering with hnRNP K increased cell spreading on fibronectin. This suggested a role for hnRNP K in controlling the rate of membrane extension, although the targets of hnRNP K in adhering fibroblasts are not known. Thus, PTB and hnRNP K likely serve separate functions in the control of cell adhesion and movement.

Analysis of the complex cellular translation apparatus controlling synthesis of the specialized cytoskeleton during adhesion and cell spreading will be an interesting direction for further experiments. Focal adhesion assembly is induced by signaling from integrin receptors upon interaction with fibronectin. This local stimulus instigates the recruitment of proteins, including paxillin, and mRNAs, including that for vinculin, to the developing focal adhesion (9). Interestingly, paxillin, which was recently shown to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, exhibits an adhesion-dependent association with PTB. Paxillin could thus assemble with PTB within the nucleus and possibly help target mRNA directly to initiating focal adhesions (13). Once recruited to an initiating site of attachment, PTB may dissociate from an mRNA and be recycled back to the nucleus. The nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of PTB is partly controlled by PKA phosphorylation (34, 48). However, posttranslational modifications affecting PTB in focal adhesion assembly could involve many other signaling molecules, including Src, FAK, or ILK. Src is present in focal adhesions (along with other kinases) and is known to regulate both hnRNP K activity and translational repression by ZBP1 (26, 39).

PTB and its bound mRNAs are presumably being actively transported to the cellular edge, but what components are important for this process are not yet known. The PTB that moves to the cytoplasm during adhesion is likely already bound to its target mRNAs, and this movement may depend on what is being expressed in a particular cell. We find that the response of PTB to adhesive interactions can vary from cell to cell; PTB redistributes to the cytoplasm during adhesion of mouse embryo fibroblasts but not adhesion of some other cell lines, such as 293 and HeLa. Tumor cells are well known to exhibit altered adhesive properties, and PTB has been reported to be upregulated in invasive glioblastoma and ovarian cancer (8, 23, 37). The effect of this increased concentration on cell adhesion and movement during tumor invasion should also be interesting to examine.

In Xenopus and Drosophila oocytes, PTB shows more stable enrichment at the sites of mRNA localization. In these systems, PTB appears to affect both the transport of an mRNA to its destination and repression of its translation during delivery (3, 11). The sequences that direct the localization can be quite complex, and many components of the mRNP that affect its cytoplasmic function are assembled in the nucleus, including the PTB protein (30). The movement of these mRNPs to their target sites in both Drosophila and Xenopus oocytes is mediated by kinesin motors on the microtubule cytoskeleton (36). The proteins responsible for the movement and anchoring of the mRNPs in somatic cells are not yet known, although processes similar to those in Drosophila and Xenopus oocytes take place in mammalian neurons and use some of the same components. PTB is present in neuronal growth cones of PC12 cells and was shown to affect their neurite outgrowth (34). Unlike PC12 cells, primary neurons switch their expression from PTB to its neuronal homolog, nPTB, as they differentiate (6, 15, 20, 35). nPTB has RNA binding and nucleoplasmic shuttling properties similar to those of PTB and can be observed in the processes of explanted neuronal cultures early after plating (unpublished observations), in keeping with a specialized role in neuronal adhesion.

We report that mRNAs for several focal adhesion proteins are bound by PTB and that PTB affects the assembly of this specialized component of the cytoskeleton. Interestingly, the set of pre-mRNA splicing targets of PTB in the nucleus is enriched in cytoskeletal and scaffolding proteins, in proteins that control cytoskeletal assembly, such as c-src, and in transport proteins, such as kinesin and dynein (5). Many of these pre-mRNA targets have exons that change during neuronal or muscle cell differentiation, when a highly specialized cytoskeleton must be assembled. The cytoplasmic function of PTB found here is presumably part of a larger role for the protein affecting cytoskeletal assembly, cell morphology, and movement during development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Geetanjali Chawla for the shPTB(B) construct, Kris DeMali for the vinculin null MEF cell line, Steven Smale for the RelA−/− MEF cell line, Arnold Berk for the SV40-transformed MEF cell line, Gideon Dreyfuss for the anti-hnRNP K antibody, and Brigitte Jockusch for the anti-Raver antibody.

I.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. This work was supported in part by NIH grant RO1GM49662 to D.L.B. D.L.B. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 August 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auweter, S. D., and F. H. Allain. 2008. Structure-function relationships of the polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65:516-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Back, S. H., Y. K. Kim, W. J. Kim, S. Cho, H. R. Oh, J. E. Kim, and S. K. Jang. 2002. Translation of polioviral mRNA is inhibited by cleavage of polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins executed by polioviral 3C(pro). J. Virol. 76:2529-2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besse, F., S. Lopez de Quinto, V. Marchand, A. Trucco, and A. Ephrussi. 2009. Drosophila PTB promotes formation of high-order RNP particles and represses oskar translation. Genes Dev. 23:195-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bomsztyk, K., O. Denisenko, and J. Ostrowski. 2004. hnRNP K: one protein multiple processes. Bioessays 26:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutz, P. L., G. Chawla, P. Stoilov, and D. L. Black. 2007. MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes Dev. 21:71-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutz, P. L., P. Stoilov, Q. Li, C. H. Lin, G. Chawla, K. Ostrow, L. Shiue, M. Ares, Jr., and D. L. Black. 2007. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes Dev. 21:1636-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla, G., C. H. Lin, A. Han, L. Shiue, M. Ares, Jr., and D. L. Black. 2009. Sam68 regulates a set of alternatively spliced exons during neurogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:201-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung, H. C., L. J. Corley, G. N. Fuller, I. E. McCutcheon, and G. J. Cote. 2006. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein and Notch1 are independently re-expressed in glioma. Mod. Pathol. 19:1034-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chicurel, M. E., R. H. Singer, C. J. Meyer, and D. E. Ingber. 1998. Integrin binding and mechanical tension induce movement of mRNA and ribosomes to focal adhesions. Nature 392:730-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condeelis, J., and R. H. Singer. 2005. How and why does beta-actin mRNA target? Biol. Cell 97:97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cote, C. A., D. Gautreau, J. M. Denegre, T. L. Kress, N. A. Terry, and K. L. Mowry. 1999. A Xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol. Cell 4:431-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Hoog, C. L., L. J. Foster, and M. Mann. 2004. RNA and RNA binding proteins participate in early stages of cell spreading through spreading initiation centers. Cell 117:649-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong, J. M., L. S. Lau, Y. W. Ng, L. Lim, and E. Manser. 2009. Paxillin nuclear-cytoplasmic localization is regulated by phosphorylation of the LD4 motif: evidence that nuclear paxillin promotes cell proliferation. Biochem. J. 418:173-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du, T. G., M. Schmid, and R. P. Jansen. 2007. Why cells move messages: the biological functions of mRNA localization. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairbrother, W., and D. Lipscombe. 2008. Repressing the neuron within. Bioessays 30:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farina, K. L., S. Huttelmaier, K. Musunuru, R. Darnell, and R. H. Singer. 2003. Two ZBP1 KH domains facilitate beta-actin mRNA localization, granule formation, and cytoskeletal attachment. J. Cell Biol. 160:77-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fred, R. G., L. Tillmar, and N. Welsh. 2006. The role of PTB in insulin mRNA stability control. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galban, S., Y. Kuwano, R. Pullmann, Jr., J. L. Martindale, H. H. Kim, A. Lal, K. Abdelmohsen, X. Yang, Y. Dang, J. O. Liu, S. M. Lewis, M. Holcik, and M. Gorospe. 2008. RNA-binding proteins HuR and PTB promote the translation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:93-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gapuzan, M. E., O. Schmah, A. D. Pollock, A. Hoffmann, and T. D. Gilmore. 2005. Immortalized fibroblasts from NF-κB RelA knockout mice show phenotypic heterogeneity and maintain increased sensitivity to tumor necrosis factor alpha after transformation by v-Ras. Oncogene 24:6574-6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabowski, P. J. 2007. RNA-binding proteins switch gears to drive alternative splicing in neurons. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:577-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gromak, N., A. Rideau, J. Southby, A. D. Scadden, C. Gooding, S. Huttelmaier, R. H. Singer, and C. W. Smith. 2003. The PTB interacting protein raver1 regulates alpha-tropomyosin alternative splicing. EMBO J. 22:6356-6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu, W., F. Pan, H. Zhang, G. J. Bassell, and R. H. Singer. 2002. A predominantly nuclear protein affecting cytoplasmic localization of beta-actin mRNA in fibroblasts and neurons. J. Cell Biol. 156:41-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He, X., M. Pool, K. M. Darcy, S. B. Lim, N. Auersperg, J. S. Coon, and W. T. Beck. 2007. Knockdown of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein suppresses ovarian tumor cell growth and invasiveness in vitro. Oncogene 26:4961-4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellen, C. U., G. W. Witherell, M. Schmid, S. H. Shin, T. V. Pestova, A. Gil, and E. Wimmer. 1993. A cytoplasmic 57-kDa protein that is required for translation of picornavirus RNA by internal ribosomal entry is identical to the nuclear pyrimidine tract-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7642-7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huttelmaier, S., S. Illenberger, I. Grosheva, M. Rudiger, R. H. Singer, and B. M. Jockusch. 2001. Raver1, a dual compartment protein, is a ligand for PTB/hnRNPI and microfilament attachment proteins. J. Cell Biol. 155:775-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huttelmaier, S., D. Zenklusen, M. Lederer, J. Dictenberg, M. Lorenz, X. Meng, G. J. Bassell, J. Condeelis, and R. H. Singer. 2005. Spatial regulation of beta-actin translation by Src-dependent phosphorylation of ZBP1. Nature 438:512-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jockusch, B. M., S. Huttelmaier, and S. Illenberger. 2003. From the nucleus toward the cell periphery: a guided tour for mRNAs. News Physiol. Sci. 18:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kislauskis, E. H., X. Zhu, and R. H. Singer. 1994. Sequences responsible for intracellular localization of beta-actin messenger RNA also affect cell phenotype. J. Cell Biol. 127:441-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knoch, K. P., H. Bergert, B. Borgonovo, H. D. Saeger, A. Altkruger, P. Verkade, and M. Solimena. 2004. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kress, T. L., Y. J. Yoon, and K. L. Mowry. 2004. Nuclear RNP complex assembly initiates cytoplasmic RNA localization. J. Cell Biol. 165:203-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence, J. B., and R. H. Singer. 1986. Intracellular localization of messenger RNAs for cytoskeletal proteins. Cell 45:407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lecuyer, E., H. Yoshida, N. Parthasarathy, C. Alm, T. Babak, T. Cerovina, T. R. Hughes, P. Tomancak, and H. M. Krause. 2007. Global analysis of mRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell 131:174-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukong, K. E., and S. Richard. 2003. Sam68, the KH domain-containing superSTAR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1653:73-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma, S., G. Liu, Y. Sun, and J. Xie. 2007. Relocalization of the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein during PKA-induced neurite growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773:912-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makeyev, E. V., J. Zhang, M. A. Carrasco, and T. Maniatis. 2007. The microRNA miR-124 promotes neuronal differentiation by triggering brain-specific alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 27:435-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin, K. C., and A. Ephrussi. 2009. mRNA localization: gene expression in the spatial dimension. Cell 136:719-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCutcheon, I. E., S. J. Hentschel, G. N. Fuller, W. Jin, and G. J. Cote. 2004. Expression of the splicing regulator polypyrimidine tract-binding protein in normal and neoplastic brain. Neuro-Oncol. 6:9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostareck-Lederer, A., and D. H. Ostareck. 2004. Control of mRNA translation and stability in haematopoietic cells: the function of hnRNPs K and E1/E2. Biol. Cell 96:407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostareck-Lederer, A., D. H. Ostareck, C. Cans, G. Neubauer, K. Bomsztyk, G. Superti-Furga, and M. W. Hentze. 2002. c-Src-mediated phosphorylation of hnRNP K drives translational activation of specifically silenced mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4535-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petit, V., and J. P. Thiery. 2000. Focal adhesions: structure and dynamics. Biol. Cell 92:477-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross, A. F., Y. Oleynikov, E. H. Kislauskis, K. L. Taneja, and R. H. Singer. 1997. Characterization of a beta-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2158-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawicka, K., M. Bushell, K. A. Spriggs, and A. E. Willis. 2008. Polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein: a multifunctional RNA-binding protein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36:641-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schepens, B., S. A. Tinton, Y. Bruynooghe, R. Beyaert, and S. Cornelis. 2005. The polypyrimidine tract-binding protein stimulates HIF-1α IRES-mediated translation during hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:6884-6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma, S., A. M. Falick, and D. L. Black. 2005. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein blocks the 5′ splice site-dependent assembly of U2AF and the prespliceosomal E complex. Mol. Cell 19:485-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spellman, R., and C. W. Smith. 2006. Novel modes of splicing repression by PTB. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:73-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillmar, L., and N. Welsh. 2004. Glucose-induced binding of the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB) to the 3′-untranslated region of the insulin mRNA (ins-PRS) is inhibited by rapamycin. Mol. Cell Biochem. 260:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams, T. M., H. Lee, M. W. Cheung, A. W. Cohen, B. Razani, P. Iyengar, P. E. Scherer, R. G. Pestell, and M. P. Lisanti. 2004. Combined loss of INK4a and caveolin-1 synergistically enhances cell proliferation and oncogene-induced tumorigenesis: role of INK4a/CAV-1 in mammary epithelial cell hyperplasia. J. Biol. Chem. 279:24745-24756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie, J., J. A. Lee, T. L. Kress, K. L. Mowry, and D. L. Black. 2003. Protein kinase A phosphorylation modulates transport of the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8776-8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, W., H. Baribault, and E. D. Adamson. 1998. Vinculin knockout results in heart and brain defects during embryonic development. Development 125:327-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zieseniss, A., U. Schroeder, S. Buchmeier, C. A. Schoenenberger, J. van den Heuvel, B. M. Jockusch, and S. Illenberger. 2007. Raver1 is an integral component of muscle contractile elements. Cell Tissue Res. 327:583-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.