Abstract

Recurrent Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses (KLAs) are rarely reported. Six cases of recurrent KLAs are characterized. Most of the patients had diabetes and K1 serotype KLAs. All of the isolates were uniformly susceptible to cefazolin. Distinct molecular fingerprints were found for the strains isolated from both primary and recurrent KLAs.

Pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae are an emerging disease. Over the past 15 years, K. pneumoniae has been identified as the predominant pathogen responsible for pyogenic liver abscesses in Taiwan (4). In the United States (12), one report documented that 41% of cases are caused by K. pneumoniae. An interesting finding was that this pathogen was isolated only from Asian and Hispanic patients (12). Although another study reported cases of KLAs in Caucasians in the United States (6), the numbers were low. The capsular serotype of K. pneumoniae was identified to be one of the major virulence factors involved in infections, including liver abscesses (4). Furthermore, the K1 and K2 serotypes were found to be the most prevalent capsular serotypes in KLAs (4). Approximately 50 to 75% of the patients with KLAs also presented with diabetes mellitus (DM) (6), and this relationship has also been documented in European studies (10, 13). In previous reports, diabetic patients were shown to be more susceptible to K. pneumoniae infection because poor glycemic control plays an important role in phagocytic resistance against K. pneumoniae (8). Cases of recurrent KLA are rarely reported in the literature. In the present study, we present six cases of recurrent KLA.

K. pneumoniae strains were isolated from patients presenting with liver abscesses at the Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan from 1996 to 2008. Liver abscesses were diagnosed by imaging studies (abdominal sonography and/or computed tomography), and pathogens were isolated from the abscesses (n = 13) or blood samples (n = 6). Prior to the diagnosis of KLA by using blood samples, samples that contained other pathogens were excluded from the study. The K. pneumoniae strains ATCC 4208 (K1), ATCC 13883 (K3), and ATCC 700603 (K6) were used as control serotypes. Patients presenting with a second abscess at least 1 year after the onset of the first KLA were categorized as having recurrent KLA and were enrolled in our study. Patients with both primary and recurrent KLAs were treated with either antibiotics or both antibiotics and percutaneous drainage; the complete resolution of the clinical presentations and imaging findings was observed at the follow-up.

Serotyping was performed by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis (5), and antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by Etest, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (2). Bacterial DNA was prepared and subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as described previously (15). The restriction enzyme XbaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) was used.

Since magA (mucoid-associated gene A) and rmpA (regulator of mucoid phenotype A) are two virulent genes associated with KLAs, genotypic analyses included the detection of these genes (16, 17). PCR was used to target the magA and rmpA genes. The primers used for the PCRs were as follows: magA, forward (5′-GGTGCTCTTTACATCATTGC-3′) and reverse (5′-GCAATGGCCATTTGCGTTAG-3′), and rmpA, forward (5′-ACTGGGCTACCTCTGCTTCA-3′) and reverse (5′-CTTGCATGAGCCATCTTTCA-3′) (16). The blaSHV-1a gene was used as an internal positive control with the forward and reverse primers 5′-ATCTGGTGGACTACTCGC-3′ and 5′-GCCTCATTCAGTTCCGTT-3′, respectively. The expected PCR products of magA, rmpA, and the positive internal control were 1,282, 535, and 213 bp in length, respectively.

Six patients (males, 3; females, 3; mean age, 59 years; range, 36 to 88 years) presenting with recurrent KLAs were enrolled between 1996 and 2008. The average duration between the first episode and recurrence was 7.6 years (range, 2 to 20 years). The most common underlying disease in these patients was DM (83% [five of six patients]). Concomitant gallstones, liver cirrhosis, and a peptic ulcer were noted in one patient. Poor glycemic control and glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels of >9% were noted in 80% of the patients (four of five) with DM. Severe complications, including brain abscesses, pulmonary embolisms, endophthalmitis, septic shock, or rupture of liver abscesses, were found in 33% of the patients (two of six) with primary KLAs. In contrast, there were no severe complications in patients with recurrent KLAs. The higher rate of complications observed in cases of primary KLA was considered to be associated with the delay in diagnosis and treatment with extended-spectrum antibiotics (1). Eighty-three percent of the patients (five of six) with recurrent KLAs received drainage because the size of the abscess was >4 cm. The survival rate for all patients with recurrent KLAs was 100%. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic data and clinical presentations of patients with recurrent KLAsa

| Characteristic(s) | Case

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sex/age (yr) | M/62 | F/58 | M/88 | F/36 | M/56 | F/58 |

| Underlying disease(s) | Diabetes, liver cirrhosis, hypertension | Gastric and duodenal ulcers | Diabetes, gallstones, HCVD | Diabetes | Diabetes, hypertension | Diabetes, hypertension |

| HbA1c level (%) | 14.7 | ND | 9.2 | 17.5 | 6.9 | 13.7 |

| Onset interval (yr) | 7 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 20 | 2 |

| First abscess | ||||||

| Size (cm) | 5.8 | 8 | 3 | Ruptured | Unknown | 9.2 |

| Locationb | 4 | 4 | 6 | Unknown | Unknown | 6, 7 |

| Bacteremia | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | Unknown | No |

| Drainage | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Complication(s) | Brain abscess, endophthalmitis, pulmonary emboli | No | No | Rupture of abscess with septic shock | No | No |

| Recurrent abscess | ||||||

| Size (cm) | 2 | 6.2 | 8 | 10 | 7.5 | 7.1 |

| Locationb | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 5, 6 | 8 | 6 |

| Bacteremia | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Drainage | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Complication | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Prognosis | Survival | Survival | Survival | Survival | Survival | Survival |

M, male; F, female; HCVD, hypertensive cardiovascular diseases; ND, no data.

Location in the liver is as follows: 1, caudate lobe; 2, left posterolateral segment; 3, left anterolateral segment; 4, left medial segment; 5, right anteroinferior segment; 6, right posteroinferior segment; 7, right posterosuperior segment; 8, right anterosuperior segment.

The isolates obtained from all six patients with recurrent KLAs and three isolates from the primary KLAs were studied (Table 2). Serotype K1 was identified for 83% of the isolates (five of six) from recurrent KLAs. In the primary KLAs, 100% of the isolates (three of three) were serotype K1. The antibiograms of the strains isolated from both the primary and recurrent KLAs indicated that all the strains were resistant to ampicillin but uniquely susceptible to cefazolin and other extended-spectrum cephalosporins. In the past two decades, the antibiograms obtained for strains isolated from KLAs have remained unchanged. All serotype K1 isolates were positive for the magA gene. The rmpA gene was detectable in isolates from all primary and recurrent KLAs (nine of nine).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the isolates from the primary and recurrent KLAsa

| Isolate and characteristics | Case

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| First isolate | ||||||

| Serotype | K1 | ND | ND | K1 | ND | K1 |

| Antibiotic resistanceb | Ampicillin | Ampicillin | Ampicillin | Ampicillin | Ampicillin | Ampicillin |

| Detection of magA | + | ND | ND | + | ND | + |

| Detection of rmpA | + | ND | ND | + | ND | + |

| Recurrent KLA | ||||||

| Serotype | K1 | K1 | K1 | Non-K1/K2 | K1 | K1 |

| Resistance to different antibioticsb | Ampicillin resistance only | Ampicillin resistance only | Ampicillin resistance only | Ampicillin resistance only | Ampicillin resistance only | Ampicillin resistance only |

| Detection of magA | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Detection of rmpA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Abbreviations: ND, no data; +, positive; −, negative.

Drugs selected for susceptibility tests include the following: ampicillin, cefazolin, gentamicin, amikacin, ampicillin plus sulbactam, piperacillin plus tazobactam, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime, ertapenem, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin.

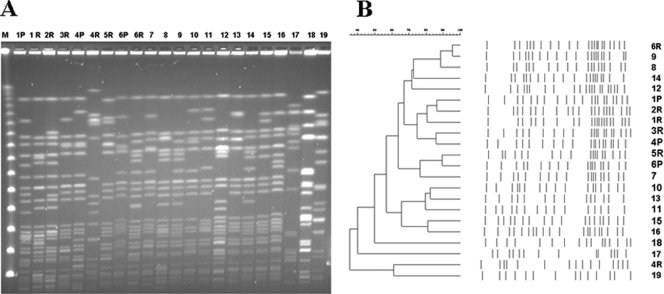

Six strains from three patients (primary and recurrent KLAs), 3 strains isolated from patients with recurrent KLAs, 10 strains from patients with community-acquired KLAs (serotype K1), and 3 ATCC K. pneumoniae control strains of serotypes K1, K3, and K6 were analyzed by PFGE. Distinct PFGE patterns were observed for all 18 strains (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(A) PFGE of strains isolated from recurrent KLAs and community-acquired KLAs. (B) Dendrogram obtained by subjecting strains from primary, recurrent, and community-acquired KLAs to PFGE. 1 to 6, recurrent KLAs (P, primary strain; R, recurrent strain); 7 to 16, community-acquired KLAs with serotype K1 strains; 17, ATCC 4208 (K1); 18, ATCC 13883 (K3); 19, ATCC 700603 (K6). The molecular fingerprints obtained for the six strains isolated from recurrent KLAs and the strains from primary KLAs were distinct from each other.

Capsular K antigens are currently known to influence the pathogenicity of K. pneumoniae (11). Among the 77 recognized capsular serotypes, K1 and K2 have been reported to have a significant association with increased virulence and infection rates (5). K1 and K2 are also the most prevalent serotypes isolated from blood, sputum, urine, and pus (5). Capsular antigens that influence antiphagocytosis and serum resistance to bactericidal activity have been reported in clinical K. pneumoniae infections (14). In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that serotypes K1 and K2 have increased lethality, and it is likely that their resistance to phagocytosis and intracellular killing contributes to their high infection rates (7).

Although the precise pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the formation of liver abscesses are not completely understood, previous studies have shown that DM is an important underlying factor that correlates with a high incidence of KLA, especially in combination with septic endophthalmitis (13). Among the patients with metastatic endophthalmitis, 92% were diabetic. Poor neutrophil function and impairment of opsonophagocytic function were noted in diabetic patients with poor glycemic control (3, 9). Of our patients, five were diabetic with poor glycemic control and had high HbA1c levels.

In conclusion, we discovered that poor glycemic control and the capsular serotype K1 are important factors that influence liver abscess formation and its subsequent recurrence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC 96-2314-B-016-006-MY1&2 and NSC 96-2314-B-016-018-MY1), Tri-Service General Hospital, the National Defense Medical Center (DOD-96-22&32), the Medical Foundation in Memory of Deh-Lin Cheng, and the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng, H. P., L. K. Siu, and F. Y. Chang. 2003. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin compared to cefazolin for treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae-caused liver abscess. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2088-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standard for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard, 10th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 3.Delamaire, M., D. Maugendre, M. Moreno, M. C. Le Goff, H. Allannic, and B. Genetet. 1997. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet. Med. 14:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fung, C. P., F. Y. Chang, S. C. Lee, B. S. Hu, B. I. Kuo, C. Y. Liu, M. Ho, and L. K. Siu. 2002. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut 50:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fung, C. P., B. S. Hu, F. Y. Chang, S. C. Lee, B. I. Kuo, M. Ho, L. K. Siu, and C. Y. Liu. 2000. A 5-year study of the seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae: high prevalence of capsular serotype K1 in Taiwan and implication for vaccine efficacy. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2075-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederman, E. R., and N. F. Crum. 2005. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100:322-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin, J. C., F. Y. Chang, C. P. Fung, J. Z. Xu, H. P. Cheng, J. J. Wang, L. Y. Huang, and L. K. Siu. 2004. High prevalence of phagocytic-resistant capsular serotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae in liver abscess. Microbes Infect. 6:1191-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin, J. C., L. K. Siu, C. P. Fung, H. H. Tsou, J. J. Wang, C. T. Chen, S. C. Wang, and F. Y. Chang. 2006. Impaired phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1 or K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91:3084-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazade, M. A., and M. S. Edwards. 2001. Impairment of type III group B Streptococcus-stimulated superoxide production and opsonophagocytosis by neutrophils in diabetes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 73:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohsen, A. H., S. T. Green, R. C. Read, and M. W. McKendrick. 2002. Liver abscess in adults: ten years experience in a UK centre. QJM 95:797-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahimian, J., T. Wilson, V. Oram, and R. S. Holzman. 2004. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1654-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomsen, R. W., P. Jepsen, and H. T. Sorensen. 2007. Diabetes mellitus and pyogenic liver abscess: risk and prognosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1194-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, J. H., Y. C. Liu, S. S. Lee, M. Y. Yen, Y. S. Chen, S. R. Wann, and H. H. Lin. 1998. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1434-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu, T. L., L. K. Siu, L. H. Su, T. L. Lauderdale, F. M. Lin, H. S. Leu, T. Y. Lin, and M. Ho. 2001. Outer membrane protein change combined with co-existing TEM-1 and SHV-1 beta-lactamases lead to false identification of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh, K. M., A. Kurup, L. K. Siu, Y. L. Koh, C. P. Fung, J. C. Lin, T. L. Chen, F. Y. Chang, and T. H. Koh. 2007. Capsular serotype K1 or K2, rather than magA and rmpA, is a major virulence determinant for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in Singapore and Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:466-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu, W. L., W. C. Ko, K. C. Cheng, C. C. Lee, C. C. Lai, and Y. C. Chuang. 2008. Comparison of prevalence of virulence factors for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses between isolates with capsular K1/K2 and non-K1/K2 serotypes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]