Abstract

Over the past decade, Mexico has experienced a significant increase in trafficking of cocaine and trafficking and production of methamphetamine. An estimated 70% of U.S. cocaine originating in South America passes through the Central America-Mexico corridor. Mexico-based groups are now believed to control 70%–90% of methamphetamine production and distribution in the U.S. Increased availability of these drugs at reduced prices has led to a parallel rise in local drug consumption. Methamphetamine abuse is now the primary reason for seeking drug user treatment in a number of cities, primarily in northwestern Mexico. While cocaine and methamphetamine use have been linked with the sex trade and high risk behaviors such as shooting gallery attendance and unprotected sex in other settings, comparatively little is known about the risk behaviors associated with use of these drugs in Mexico, especially for methamphetamines. We review historical aspects and current trends in cocaine and methamphetamine production, trafficking and consumption in Mexico, with special emphasis on the border cities of Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana. Additionally, we discuss the potential public health consequences of cocaine use and the recent increase in methamphetamine use, especially in regards to the spread of bloodborne and other infections, in an effort to inform appropriate public health interventions.

Keywords: cocaine, methamphetamine, injection drug use, bloodborne infections, Mexico

Introduction

Mexico has been an important transit point along cocaine trafficking routes for decades. Over two thirds of the cocaine originating in South America that enters the United States passes through the Central America-Mexico corridor (DEA, 1996, 2003). However, only recently has Mexico become involved in the refining process and taken a more active role in cocaine trafficking.

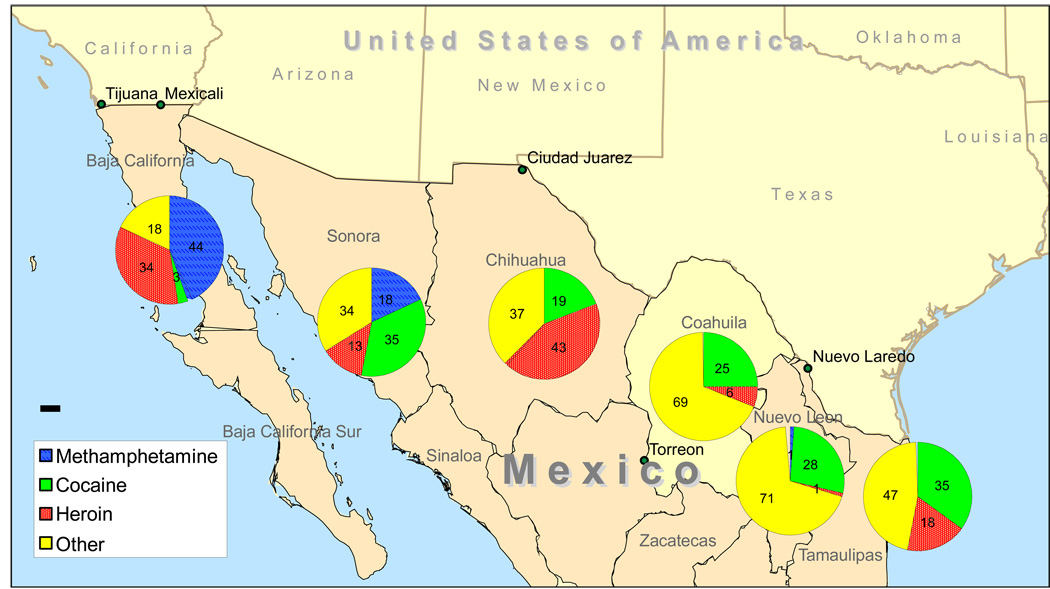

During the past decade, Mexico has also become an important producer of methamphetamine, which in turn has led to growth of local consumption markets. In the border city of Tijuana, Mexico’s northwestern most city, 44% of drug users cited methamphetamine (known as ‘crystal meth,’ or locally as ‘crico’ or ‘cri-cri’) as the most common reason for seeking treatment at drug user treatment centers, an increase from 30% in 2000 (ISESALUD, 2002). Other drug user treatment clinics in northwestern states, including Ensenada and Mexicali in the state of Baja California, La Paz in the state of Baja California Sur, and Culiacan in the state of Sinaloa, also cite methamphetamine as the most common problem for those seeking drug user treatment (SSA, 2002; Figure 1). Figure 1 illustrates how methamphetamine use is highest in western states whereas cocaine use predominates in the east (Maxwell et al., 2005; Patterson et al., 2005; Strathdee et al., In press).

Figure 1. Map of drug user treatment admissions in Mexican states bordering the U.S.

Pie charts above each of the six Mexican states bordering the U.S. show the percent of drug user treatment admissions by primary drug used. Data was compiled based on the Mexican Addiction Epidemiologic Surveillance System or SISVEA (Maxwell et al., 2005). The “Other” category includes marijuana, inhalants, alcohol, tobacco, and a variety of veterinary products.

Below, we describe the role of Mexico as a transit route for cocaine, and its increasingly important role in methamphetamine production and trafficking. We also describe recent trends in the use of these drugs in Mexico, and discuss potential public health implications, given that both have been associated with high risk behaviors such as unprotected sex and binge use in other settings (Bruneau et al., 1997; Melbye et al., 2002; Semple et al., 2003; Tyndall et al., 2003). Among injection drug users (IDUs), cocaine use has been closely linked to needle sharing and attendance at shooting galleries (Bruneau et al., 1997; Tyndall et al., 2003). Injection of methamphetamine has also been associated with more frequent engagement in sexual risk behaviors (Semple et al., 2004). As a consequence, use of these drugs has subsequently led to the spread of sexually transmitted and bloodborne infections among various populations. We report here on available literature regarding the extent to which these risk behaviors accompany cocaine and methamphetamine use in the Mexican context. Readers interested in Mexico’s growing role as a producer and trafficker of heroin are referred to a recent review on this topic (Bucardo et al, In press).

To obtain materials for this review we initially performed a broad search of standard medical and social science databases (e.g., PubMed and PsycINFO) using keywords such as cocaine, methamphetamine, trafficking, substance abuse, HIV, and Mexico. We then expanded our search to non-indexed major databases (e.g., LILACS), health and policy related websites maintained by federal and state governmental offices in Mexico and the United States, and abstracts of relevant conferences (e.g., International Conference on AIDS). Finally, data was obtained from personal contacts with members of non-governmental organizations, drug user treatment centers, and pharmacies.

Cocaine trafficking in Mexico

Although coca leaf is not cultivated to any appreciable extent within the country, Mexico has been a major transit point for cocaine since the 1970s. Before that time cocaine seizures by authorities were negligible, at less than ten metric kilograms (kg) per year. The amount of cocaine seized by drug enforcement officials surpassed 100 kg per year in the 1970s, four metric tons in 1985, and almost fifty metric tons in 1990 (Astorga, 1999). Up to 70% of all South American cocaine currently passes through the Central America-Mexico corridor (DEA, 2003) and approximately 50% enters by land along the 2000 mile long U.S.- Mexico border (Finckenauer et al., 2001).

The evolution of Mexico from a transit point to a major player in the cocaine trade grew in part out of intensified prosecution of Colombian drug cartels. In the mid-1980s, there was increased enforcement by the U.S. coastguard and U.S. federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents off the coast of the U.S. state of Florida (Finckenauer et al., 2001). In light of this crackdown, Colombian cartels permitted Mexico-based traffickers to take a greater role in the cocaine trade (Smith and Toro, 1997). From the 1980s onward, the Mexico/U.S. land border became the primary point of entry of cocaine into the United States (Reding, 1995). Initially, Colombian cartels passed on refined cocaine to Mexican middlemen, who would transport it across the U.S. southwest border, leaving stashes in locations where Colombian groups operating within the U.S. would later retrieve them (Finckenauer et al., 2001; Smith and Toro, 1997).

In 1989, nearly 21 metric tons of cocaine were seized by drug enforcement agencies from the Colombians (DEA, 2001). That same year, Mexican smugglers, reportedly annoyed with delinquency of payment from their Colombian partners, held back shipments to extort compensation (Finckenauer et al., 2001). These events led to a dramatic shift in the relationship between Colombian organized crime and Mexican transporters. By the mid-1990s, Mexican smugglers received up to half of the cocaine transported across the border as payment for services. This obviated the need for large cash transactions, which could be more easily monitored by prosecutors (DEA, 2001). Although with this change the Columbian cartels gave up a part of the large wholesale U.S. cocaine market, it eased logistics and removed some of the vulnerabilities of the Colombian cartels. The result has been that Mexican crime organizations now control much of the wholesale cocaine distribution in the West and Midwest of the United States (UNODC, 2001).

In light of stiff prosecutions against Colombian traffickers in the early 1990s, cocaine trafficking further shifted from the Caribbean to Mexico. In 1987, the amount of cocaine seizures was roughly equal between the Caribbean and Mexico, but by 1997 seizures in Mexico – believed to roughly reflect the total amount being trafficked – were more than twice that of the Caribbean (UNODC, 2001).

The transition of Mexican-based groups from ‘small-time’ smugglers to major traffickers was perhaps facilitated by the increase in cross-border trade with the advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In 1999, according to the U.S. Customs Service, Mexico and the U.S. had more than 190 billion U.S. dollars worth of legitimate trade, making Mexico the second largest trading partner of the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). More than 295 million people, involving upwards of 88 million cars and 4.5 million trucks and railroad cars, cross at 38 official border crossing points each year (U.S. Customs Service, 2004). In particular, the San Ysidro border crossing at the junction of Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico and San Diego, California, U.S.A. is reportedly the busiest land border crossing in the world, with 46 million persons and 14 million vehicles crossing annually (U.S. Customs Service, 2004). It is unknown to what extent increased trade flow may have facilitated drug transport, however in some cases the economic changes inherent with free trade may have led certain groups to become involved in the drug trade (Smith and Toro, 1997). For instance, Quinones et al. described how urban artisans known as Tepitenos (after the Mexico City barrio of Tepito) used to make a living by repairing and reselling junk. This provided a decent living in this poor neighborhood in the pre-NAFTA environment of high tariffs on legally imported consumer goods.

“As tariffs have fallen and the market for black-market merchandise dwindled, Tepitenos have found that there's only one thing that will generate the kinds of profits they're now used to. So Tepito has become Mexico's cocaine mart” (Quinones, 2001).

While prices vary by purity, it is estimated that within Mexico a kilogram of cocaine sells for $6,000–10,000 U.S. dollars and Mexican traffickers receive up to $19,000 per kg when delivering to the U.S. (DEA, 2003). The extent to which NAFTA will have an effect on the drug trade has yet to be fully realized (Smith and Toro, 1997).

The Colombia/Mexico drug connection has continued to evolve. Recent reports indicate that high-level traffickers in Colombia have sought to even further distance themselves from the day-to-day operations of cocaine distribution within the U.S., often turning over their distribution practices to Mexican-based organizations (DEA, 2001). A possible motive behind this is the extradition law enacted by the Colombian National Assembly in December 1997 (DEA, 2001). Recently, it has also been reported that coca base is now being smuggled into Mexico, whereby processing to cocaine hydrochloride is performed by Mexican traffickers (DEA, 2003). However, cocaine production is considered the exception rather than the rule, since the vast majority of cocaine trafficked in Mexico is already the finished product. This does not appear to be due to a lack of infrastructure - such as institutional and non-institutional networks required for cultivation, processing, and trafficking - for in the case of heroin, poppy cultivation, processing, and distribution is well organized (Bucardo et al., In press). Rather, it may be that the current situation provides the more ideal risk to benefit ratio for Mexican cocaine traffickers.

The west coast of Mexico has long been a favored smuggling route for cocaine (UNODC, 2001). These same routes are also believed to be a transit point for potassium permanganate, which is used in the cocaine purification process (UNODC, 2003). Eight percent of all cocaine seizures in the world took place in Mexico prior to 2001 (UNODC, 2001), however, the events following the terrorist attacks on the U.S. on September 11th 2001 led to the relocation of a large amount of U.S. interdiction forces from this area, opening the way for an even greater increase in drug trafficking along the Mexican coast (UNODC, 2003). At the same time, September 11th led to increased law enforcement all along the northern Mexico/U.S. border. The combined consequences of these two changes are reported to have resulted in increases in availability of illicit drugs in Mexican border towns (Bucardo et al., In press; Medina-Mora and Rojas Guiot, 2003).

Methamphetamine Production and Trafficking in Mexico

Up until the mid-1990’s, most methamphetamine production and trafficking in the U.S. was done by local outlaw motorcycle gangs and a variety of other small-scale, local producers (Finckenauer et al., 2001). However, in the 1990’s, with the crackdown of ‘meth’ laboratories in the U.S., Mexican drug organizations started producing high quality, low priced methamphetamine and thus began to out-compete U.S.-based groups (Smith and Toro, 1997).

Clandestine labs are believed to have initially obtained precursor chemicals, such as ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, from pharmaceutical or chemical companies producing or importing chemicals into Mexico (DEA, 2001). The Organization of American States Interamerican Commission for Drug Abuse Control reports that seizures of methamphetamine precursors have increased steadily in Mexico since the late 1990’s. They document an almost ten-fold increase in pseudoephedrine seizures between 1999 (348 kilograms) and 2003 (3,381 kilograms) (Organización de Estados Americanos, 2004). During the late 1990’s, illicit Mexican labs developed international connections with groups in Canada, Asia, and Europe to supply tons of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine (DEA, 2003). In January 2003, Canada, which had been the main supplier of pseudoephedrine to Mexico, enacted legislation to control its distribution (Government of Canada, 2002). The seizure that same year of 22 million pseudoephedrine tablets en route from Hong Kong to Mexico, however, suggests that Mexican traffickers have been resourceful in finding alternative suppliers (DEA, 2003).

The DEA now estimates that Mexico-based groups control 70 to 90% of methamphetamine production and distribution in the U.S. (DEA, 2001; UNODC, 2003). Baja California, Jalisco, Guerrero, and Michoacan are the main Mexican states in which methamphetamine production is believed to take place (DEA, 2002). In 1998, there were 96 kilograms of methamphetamine seized in Mexico; in 2001, 400 kg; and in 2003, 741 kg seized, representing an eight-fold increase over just 5 years (Organización de Estados Americanos, 2004). Similar increases have been seen in seizures at the southwestern U.S. border, from 504 kg in 1997 to 1370 kg in 2001 (DEA, 2002). Drug enforcement agencies in Mexico have only recently started to focus on methamphetamine, and thus seizures of clandestine laboratories and their product are comparatively low.

The exact number of methamphetamine production sites in Mexico is unknown. It is believed that Mexican organizations have labs throughout Mexico and California, including ‘super’ labs capable of producing hundreds of pounds per week (Finckenauer et al., 2001). The International Narcotics Control Strategy report stated that ten labs were destroyed in Mexico in 2002; however, Mexican officials in the state of Baja California claimed that 53 labs were closed in Baja California alone that year (DEA, 2003). These conflicting reports suggest lack of coordination and communication among drug enforcement officials or perhaps a lack of considering methamphetamine supply reduction a priority. Most methamphetamine labs are discovered as the result of fires or complaints of unpleasant odors by neighbors, rather than active investigation. Mexico is also a source for other substances that can be abused including anabolic steroids, veterinary products, such as ketamine, and pharmaceuticals such as Rohypnol (Organización de Estados Americanos, 2004).

Trends in Cocaine and Methamphetamine Use in Mexico

With the increased role of Mexico in the trafficking and production of illicit drugs, the perceived availability of drugs has increased locally and has been associated with increased experimentation and continued use in Mexican adolescents (Villatoro et al., 1998). Often drug shipments are delayed in Mexican border towns before delivery to the U.S., which has likely contributed to the high rates of local drug consumption in northern border cities compared to the rest of Mexico (Medina-Mora and Rojas Guiot, 2003; SSA, 1998). A 1998 national survey showed that the percentage of the general population 12–65 years of age reporting having ever used an illegal drug was 14.7% in Tijuana, which was almost three times that of the national average (5.3%); in fact, Tijuana is the city with the highest consumption of illicit drugs in the country, with the next highest being the northern border city of Ciudad Juarez at 9.2% (SSA, 1998). Between 90–95% of injection drug use in Mexico is believed to occur in cities where illicit drugs are produced or trafficked, which is a situation common in this border region (Magis-Rodriguez et al., 2002). Interestingly, a 1991 national survey of students throughout Mexico found that more than a third of those who had used cocaine, crack, or heroin used it for the first time in the United States. The second most common location of initial drug use was in the northern border state of Baja California (Medina-Mora et al., 1993). A high proportion of initial use was also reported in the western states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Jalisco (Medina-Mora et al., 1993).

To monitor drug use trends, the Mexican government recently implemented a national drug use epidemiologic surveillance system (SISVEA). It began in 1991 at eight sites in six states, primarily in cities bordering the U.S., but has since expanded to cover 53 cities in all 32 Mexican states (SSA, 2002). This system compiles data from sources such as forensic services, emergency rooms, and drug user treatment centers to provide broad, annual data on changes in patterns of consumption, risk groups, new drugs, and other factors associated with drug use within Mexico. Furthermore, since 1988 the Mexican National Institute of Psychiatry has conducted a periodic National Survey on Addictions (ENA) which also provides valuable information on the growing drug abuse problem (SSA, 1998). Occasional in-depth studies by universities and government agencies have further helped to describe the latest trends and concerns regarding drug abuse in Mexico.

In the decade between the first National Survey of Addictions in 1988 and the most recently published survey results in 1998, the percentage of Mexicans reporting ever having used an illegal drug in their lifetime increased from 3.3% to 5.3% among the urban population 12–65 years of age (SSA, 1998). Nationwide, the most popular drugs used were marijuana, which had been used by 4.7% of the population, cocaine by 1.5%, and inhalants by roughly 1% (SSA, 1998). This still lags far behind Mexico’s northern neighbors. The percentage of U.S. residents aged 12 or older reporting illicit drug use at least once in their lifetime (46%) is 8 times greater than Mexico (U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004), and the percentage of Canadians aged 15 and older (23.1%), is 4 times greater than the Mexican figures (Statistics Canada, 1994). Although the prevalence of illicit drug use is still comparatively low in Mexico, this does not discount the importance of combating recent increases in the rate of drug use, especially in border areas. Furthermore, of note is the predominance of cocaine use in Mexico. Whereas 16% of Canadians who had ever used an illicit drug in their lifetime had used cocaine or crack, 28% of Mexicans who had used drugs reported such use (Statistics Canada, 1994; SSA, 1998).

Cocaine consumption

In the 1800s, cocaine and coca wines were commonly prescribed pharmaceuticals in Mexico and were easily available at markets and pharmacies (Astorga, 1999). Yet only recently has abuse of cocaine become a public health issue in Mexico. Cocaine use rose during the 1980s and 1990s along with Mexico’s increased role in cocaine trafficking. In the decades before this period, consumption was not generalized – reportedly occurring mainly among persons of high socioeconomic status, intellectuals, and artists (Tapia-Conyer et al., 2003). From 1988 to 1998, the percentage of people reporting ever having used cocaine increased from 0.33% to 1.5% (SSA, 1998). This period also corresponded with new formulations and routes of administration (e.g., speedball, crack cocaine, injection) (Tapia-Conyer et al., 2003).

According to the 2002 SISVEA, cocaine was the most common drug of abuse among those seeking treatment (38% of 18,070 patients) at government drug user treatment centers in Mexico and the second most common drug of abuse at centers operated by non-governmental organizations (19% of 31,819 persons seen that year) (SSA, 2002). Of persons reporting cocaine use, approximately 90% were men, a third were between the ages of 20 and 24, and over half consumed the drug daily. Prior heavy abuse of alcohol or tobacco was common in cocaine users, and approximately 6% of all those in treatment used cocaine as their first illicit drug (SSA, 2002). This national survey also found that it was common to mix cocaine with other drugs; only 38% of those in treatment had used cocaine alone. Approximately one fifth mixed cocaine with heroin, in the form of speedball, and 17% mixed cocaine with methamphetamine (SSA, 2002).

An investigation of cocaine use in Ciudad Juarez indicated that on average five different drugs (including alcohol and tobacco) were used before drug users switched to cocaine. Not surprisingly, there was a non-significant trend towards administration by injection in those who were heavy rather than moderate or light users; nearly 90% of those who continued cocaine use for eight years became heavy users (Tapia-Conyer et al., 2003). In a study of IDUs in drug user treatment centers in Tijuana, most were poly-drug users with 96% having used heroin, 80% cocaine, 57% speed, 50% crack, and 34% methamphetamine (Badillo et al., 1998). Likewise, poly-drug use has been found to be common in the prison population. A 2000 survey found that the prevalence of injection drug use was 37% among Tijuana prisoners and 24% in Ciudad Juarez, with 92% injecting heroin, 36% inhaling cocaine, and 46% injecting speedball (Magis-Rodriguez et al., 2000).

A report presented at the U.S. Mexican Binational Demand Reduction Conference in 2002 suggests that cocaine may be replacing marijuana as the drug of choice in young people (DEA, 2002). Over 21% of adolescents in the Consejo Tutelar de Menores (juvenile detention center) had used cocaine (SSA, 2002). Cocaine use is also believed to be a problem in commercial sex workers. Since 1989 cocaine was documented as the primary illegal drug among sex workers in Ciudad (Cd.) Juarez (Ramos and Ortega, 1991). A 2002 survey of commercial sex workers in Cd. Juarez found that over half had used cocaine in the past month, with 39% reporting use within the past 48 hours (Valdez et al., 2002). More recently, a large, ongoing study of female sex workers in Cd. Juarez suggests that as many as half may be using cocaine (Dr. T.L. Patterson, personal communication, January 2005). A survey in 1989 conducted among sex workers in the northwestern border city of Tijuana found that 14.5% had used cocaine (Güereña-Burgueño et al., 1992), but preliminary findings of an ongoing study of 450 female sex workers in Tijuana suggests that methamphetamine is quickly gaining ground as the drug of choice among female sex workers in this city (25% of sex workers reported cocaine use and 21% reported methamphetamine). This is in contrast to the Cd. Juarez situation, where the same study has thus far found only 6% of Cd. Juarez sex workers use methamphetamines (Patterson et al., Submitted).

Despite its increasing use, surveys have indicated that use of cocaine, especially in the form of crack, is met with some degree of social stigma, even among those in drug user treatment (Medina-Mora et al., 1993; Ortiz et al., 1997). In surveys among women in Ciudad Juarez bars, local jails, and other settings, sedatives, heroin, and non-stimulant drugs in general were preferred (Hammet et al., 1992). During individual unstructured interviews, conducted by staff of the non-governmental organization Programa Compañeros in the late 1980’s, women in jail reported knowing how to make crack cocaine, yet they reported not to use it. These incarcerated women, who reported using sedatives and occasionally heroin, stated that they did not use crack because they did not like the high. They also mentioned that this was in spite of the generally lower cost of using crack cocaine compared to other drugs. The reason most often mentioned by the women was that crack was considered to cause a high that can cause women to lose control (Dr. R. Ramos, personal communication). However, dislike and even stigma associated with stimulants such as methamphetamines and crack cocaine may be breaking down. In 2005, there is information from Cd. Juarez that suggests the advent of methamphetamine (Patterson et al., Submitted). There is also anecdotal information that crack cocaine in now on the list of drugs used in Cd. Juarez by poly-drug users, although it is not clear to what extent women are now using crack (Dr. Joao Ferreira-Pinto and Maria Elena Ramos, personal communication).

Following the events of September 11, 2001, there was a reported short-term increase in the consumption of both cocaine and heroin in Mexican populations along the U.S./Mexico border (Medina-Mora and Rojas Guiot, 2003). Due to reduced demand in the U.S., coupled with stricter border control measures, less cocaine is exported to the U.S. This has led to an over-supply of cocaine which has resulted in decreased prices as dealers attempt to unload extra drug along trafficking routes, especially in border areas (UNODC, 2003). With increased cocaine use, there has been a parallel rise in demand for drug user treatment in Mexico (Medina-Mora and Rojas Guiot, 2003). In the 1990’s, a similar situation occurred in the Mexican state of Coahuila. Interdiction efforts in the Torreon area by the Mexican army resulted in a build up of drugs in the agricultural town of San Pedro de las Colonias. Small time dealers, many of whom were migrants who had previously lived in the United States, took advantage of the situation to offload their drugs locally, often cutting the drugs with other substances to further increase volume (Magis and Badillo, 2003). This resulted in cheap prices for both heroin and cocaine, with doses selling for 20–30 pesos (11 pesos = approximately 1 U.S. dollar (USD)); whereas a similar dose would cost 100–150 pesos in Mexico City and $20–50 USD on the U.S. side of the border (Magis and Badillo, 2003). Through in-depth interviews with hospital and drug user treatment personnel, ex- and current IDUs, and by accessing files from health providers and NGOs that work with IDUs, the increase in use and availability was linked with a subsequent epidemic of drug and overdose-related hospitalizations and fatalities as well as the transmission of bloodborne infections. Prior to this period, San Pedro had a total of 20 registered cases of AIDS, two of which were associated with injection drug use. A rapid assessment carried out through snowball sampling of drug users at the end of 1999 found 8% of IDUs to be HIV-positive (Magis and Badillo, 2003). The long term effects of current increased border security on drug availability, consumption, and disease transmission in Mexican border cities requires further study.

Methamphetamine use

Methamphetamine use has also become a major public health concern in Mexico as a consequence of the country’s growing role as a major production site. LSD and other synthetic drugs first began to be used in the 1950s. In the 1990s, the use of synthetic drugs, primarily in the form of amphetamines, re-emerged among young people (Medina-Mora and Rojas Guiot, 2003). In Mexico, methamphetamine is usually nasally inhaled or smoked after being heated. It is smoked in a variety of devices, such as hollowed-out light bulbs or ‘focos.’ It has also been reported to be injected alone or in combination with other drugs (e.g., heroin) (SSA, 2002; Strathdee et al., In press). In the U.S., it has also been ingested or used as an anal or vaginal suppository, especially preceding sexual intercourse among men having sex with men (Semple et al., 2002, 2003). Other than the euphoric ‘high’ and sociability associated with methamphetamine use, desired effects of methamphetamine can include enhancement of libido and/or energy and weight management (Semple et al., 2003).

In the most recent national SISVEA survey in 2002, methamphetamine or crystal was the third most common drug of abuse mentioned among those seeking treatment at non-governmental treatment centers throughout the country (16%). About half of methamphetamine users were between 20 and 29 years of age and 77% consumed it daily by inhalation or injection (SSA, 2002). Methamphetamine ranked as the primary reason for seeking drug user treatment in many centers in Mexico, including those in the western states of Baja California, Baja California Sur, and Sinaloa (SSA, 2002). Between 2000 and 2002, the percentage of those seeking drug user treatment and reporting methamphetamine as their first illicit drug rose from 6% to 15% in Tijuana (ISESALUD, 2002). Its cheap price and availability are believed to be major factors leading to its popularity in this city (Dr. Isaac Alba, Director, Clinica Ser, private Tijuana drug rehabilitation clinic, personal communication).

Additional insight into methamphetamine use in this region is observed in San Diego, California, which is just 10 miles north from the San Ysidro border crossing on Tijuana’s northern edge. In a study of HIV-infected men having sex with men in San Diego who regularly used methamphetamine, 95% also reported using other drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy (3, 4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine or MDMA), GHB (gamma hydroxybutyrate), ketamine, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), PCP (pencyclidine), or Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) (Patterson et al., 2005).

Implications for the Spread of Sexually Transmitted and Bloodborne Infections

Cocaine use and disease transmission

In the U.S. and Canada, injection of cocaine has been associated with both high risk injection behaviors (e.g., frequent, episodic injection, needle sharing, shooting gallery attendance) and high risk sexual behaviors (e.g., involvement with the sex trade and unprotected sex). Several studies have shown an independent effect of cocaine injection on the risk of HIV seroconversion among IDUs (Bruneau et al., 2001; Strathdee et al., 2001; Tyndall et al., 2003). In Brazil, cocaine has been associated with a high risk of overdose (Mesquita, Kral, Reingold, Haddad et al., 2001), and among males, unprotected anal sex, bisexuality and prostitution (de Souza et al., 2002). An outbreak of HIV infection among IDUs in Vancouver in the mid-1990’s was attributed in part to a shift from heroin to cocaine as the main injected drug (Schechter et al., 1999; Strathdee et al., 1997; Tyndall et al., 2003). In the northern Mexican city of Cd. Juarez, cocaine use has been found to be strongly linked to the sex trade. In a recent survey of 75 sex workers (85% female), 51% reported using cocaine in the past month. Most (64%) started illicit drug use while a sex worker. Crack, as expected from the cocaine use trends mentioned in the previous section, was comparatively unpopular, with 5% reporting use in the past month. However, this study does differ from past studies of drug preferences in that there was a high rate of using cocaine alone (only 13% used cocaine with heroin in the form of speedball) and may indicate growing social acceptability of this drug (Valdez et al., 2002). Roughly half of women reported using drugs during sex work, with cocaine being the most common drug of use (used by 89% of those using drugs at work) (Valdez et al., 2002). The study also indicated a clear intersection between drug and sex networks, with 28% of sex workers identifying injection drug users as sexual partners in the previous year (Valdez et al., 2002).

Continual monitoring of drug use trends and administration methods can be of great benefit when developing public health interventions. In Montreal, Canada more frequent injection of cocaine was associated with a lower likelihood of injection cessation (Bruneau et al., 2004). On the other hand, obtaining syringes at needle exchanges and pharmacies was associated with a greater odds of injection cessation (Bruneau et al., 2004), underscoring the potential role of these interventions in reducing exposure to bloodborne infections and potentially mitigating drug use itself. However, sterile syringe coverage in the context of high frequency cocaine injection remains a challenge (Remis et al., 1998; Strathdee et al., 1997). In the recent survey of sex workers in Ciudad Juarez mentioned in the previous paragraph, 21% injected drugs, with 31% injecting cocaine and 38% injecting speedball (heroin and cocaine). Of these, 56% said they injected in the company of others and approximately a third admitted to sharing needles (Valdez et al., 2002).

In settings outside of Mexico, crack cocaine has been associated with sex trade involvement, including trading sex for drugs (Edlin et al., 1994; Spittal et al., 2003). Not surprisingly, crack use has been associated with high rates of HIV infection (Edlin et al., 1994). In contrast, HIV prevalence in Brazil decreased as injection of cocaine decreased and smoking of crack cocaine increased (Mesquita, Kral, Reingold, Bueno et al., 2001). These observations suggest that monitoring of drug use patterns may provide advance warning of potential changes in the subsequent spread of bloodborne infections. Crack smokers also have a high prevalence of oral sores, suggesting that in some cases these sores could facilitate oral HIV transmission (Faruque et al., 1996).

In a New York study, crack smoking was independently associated with tuberculin positivity (Howard et al., 2002) and in California, crack smoking was similarly associated with an outbreak of tuberculosis (Leonhardt et al., 1994). Although the rate of crack use appears to be low in Mexico and even less tolerated than cocaine, the high prevalence of tuberculosis in Mexico suggests that the potential exists for spread of tuberculosis if crack use were to become more common. To our knowledge, only one study has found cocaine use to be associated with tuberculosis in Mexico. In a population-based survey in the southern Mexican state of Veracruz, those with persistent cough were tested for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A total of 371 patients were followed an average of 32 months to monitor treatment outcome and mortality. Even though drug use is believed to be very low in this part of Mexico, 6% of those with tuberculosis regularly consumed illicit drugs. Consumption of cocaine was associated with a 20 fold increase in need for re-treatment during the follow-up period (Garcia-Garcia et al., 2001). This study suggests that there is a need to investigate whether there is a wider link between illicit drug use and tuberculosis, especially in regards to multi-drug resistance in Mexico.

Methamphetamine use and disease transmission

Although to our knowledge there are no published reports on particular risk behaviors associated with methamphetamine use in Mexico, use of methamphetamines has been associated with high-risk sexual activity and high HIV and STD prevalence among men having sex with men in the U.S. (Semple et al., 2003; Woody et al., 1999) and in countries such as Thailand, where it is also mass produced (Melbye et al., 2002). An ongoing study in Tijuana suggests that one of the main drugs of choice among female sex workers is methamphetamine, whereas among female sex workers in Cd. Juarez heroin predominates (Patterson et al., Submitted).

Binging on stimulant drugs such as crack, cocaine, and methamphetamine has also been associated with sexual behaviors that pose a higher risk of HIV infection, including greater numbers of partners, decreased condom use during vaginal and anal intercourse, and sex trade involvement (Chiasson et al., 1991; Edlin et al., 1994; Semple et al., 2002). In San Diego, HIV-infected men who have sex with men who reported methamphetamine binging and/or poly-drug use also reported greater unprotected anal sex with serodiscordant partners or partners of unknown HIV serostatus (Patterson et al., 2005; Semple et al., 2002).

In 2003, the DEA’s Special Testing and Research Laboratory showed that the national average purity of methamphetamine in the U.S. was 48%, but methamphetamine of Mexican origin had an average purity level over 80%. With increasing purity comes an increased chance of health-related problems and use of emergency medical services (DEA, 2003), since acute methamphetamine intoxication often results in agitation, violence, and death (Richards et al., 1999). Although the 2002 SISVEA reported emergency department and forensic statistics associated with drug use, information specific to methamphetamine use was not provided (SSA, 2002). Statistics that same year from San Diego show 81 methamphetamine-related deaths, or 3% of all certified deaths (DAWN, 2004b). The 2002 San Diego rate of amphetamine/methamphetamine-related emergency department visits was 68 per 100,000 persons (DAWN, 2004a). Chronic use of methamphetamines may also lead to heart failure, malnutrition, and permanent psychiatric illness (Richards et al., 1999; Shoptaw et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2003), indicating that the health threats of methamphetamine use go far beyond that of acute health emergencies.

Conclusions

The role of Mexico in trafficking of cocaine and trafficking and production of methamphetamine has increased substantially over the past decade. Only recently, however, has local use of these drugs become recognized as a public health problem. Because of this, many questions remain about the potential role cocaine and methamphetamine use may play in the spread of bloodborne and sexually transmitted pathogens in Mexico. From past studies in other settings, a direct link has been demonstrated between use of these drugs and unsafe sexual behaviors and transition to injection. There is therefore an urgent need to study the relationship between consumption, routes of administration, risky sexual behaviors, transition to injection and needle sharing behaviors in the Mexican context.

While studies conducted to date have provided a valuable glimpse at the drug problem in Mexico, there is a need for methodologic approaches which transcend data collection on individual behaviors to include macro-level factors associated with availability, purity, and price of drugs. Restricting studies to linear models when non-linear networks may be involved may lead to inappropriate conclusions and interventions. For this reason, tools such as artificial neural networks and respondent-driven sampling (Buscema et al., 1998; Heckathorn, 1997) are being employed to explore drug trends and disease transmission. Beyond the users themselves, examples of some of the key stake-holders in the drug situation in the Mexico include pharmacists, police officers, legal professionals, ‘small-time’ drug dealers, public health officials, drug user treatment providers, and NGO staff providing risk reduction. Because much of the drug abuse in Mexico has concentrated in border areas, it is also imperative to study the complex inter-relationship between drug interdiction, production, trafficking, migration, and risk behaviors along the 2000 mile porous border between the U.S. and Mexico. The daily flow of tourists, migrant workers, and commuters in both directions has enormous potential health implications for both countries.

Current and past studies have indicated that the drug use scene in Mexico is complex and may vary between and within states. Therefore, if public officials hope to stem the escalating problem of drug use in Mexico, there is a concomitant need to expand available treatment options and behavioral interventions for cocaine and methamphetamine addiction, especially in the context of poly-drug use.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge donor support for the Harold Simon Chair in International Health and Cross-Cultural Medicine. Many thanks to Dr. John Leake and Lourinda Brouwer who translated the abstract into French, and Saida Gracia Perez, and Angie Ellison, who edited the Spanish translation. This research was funded in part by a 2004 developmental grant from the UC San Diego Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program #P30 AI36214-06, NIH grants MH62554, R01 MH61146, R01 DA12116 and a NIDA administrative supplement (DA09225-S11). K. B. is supported by an NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (5 T32 AI07384) administered through the UCSD Center for AIDS Research.

Glossary

- DEA

United States federal Drug Enforcement Agency

- UNODC

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Biographies

Kimberly C. Brouwer, Ph.D.

Dr. Kimberly Brouwer is a Post-graduate Researcher in the Division of International Health and Cross-Cultural Medicine at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). She joined this faculty in January of 2004. Prior to this appointment, she worked for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initially as an Emerging Infectious Diseases Fellow and later as an epidemiologist, where she focused on aspects of HIV/malaria co-infections. Her Ph.D. is in molecular epidemiology from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. Since joining the faculty at UCSD she has collaborated with Mexican researchers in studies of injection drug use in cities along the U.S./Mexico border. Dr. Brouwer is currently principal investigator of a five-year grant to explore social and environmental factors affecting disease transmission and risk behaviors among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Dr. Brouwer's research interests also include studies of the epidemiology and molecular epidemiology of tropical infectious diseases.

Patricia Case, Sc.D., M.P.H.

Dr. Patricia Case is an Assistant Professor of Social Medicine and Director of the Program in Urban Health at the Harvard Medical School. She received her MPH from the University of California – Berkeley in 1991 and her Sc.D. from the Harvard School of Public Health in 1997, joining the faculty of Harvard Medical School the same year. Dr. Case has been collaborating on research activities assessing HIV among injecting drug user populations since 1986. Dr. Case’s research interests are wide ranging, but have primarily focused on the social context of infectious disease transmission among urban drug users. Her research approach combines field based qualitative methodologies with a more traditional epidemiological perspective in order to contextualize the findings of large quantitative studies. She has made major contributions to the national debate to legalize syringe exchange programs and in extending knowledge of understanding to the health concerns specific to women who have sex with women. Dr. Case is currently working on projects at the intersection of policy and behavior and is a NIDA-funded investigator on the Rapid Policy Assessment and Response project that uses rapid assessment techniques to evaluate HIV and drug use policy implementation in Poland, Ukraine and Russia and is collaborating on the development of similar HIV policy evaluation projects in several other countries.

Rebeca Ramos, M.P.H., M.A.

Rebeca L. Ramos was born in El Paso, Texas and has lived as a U.S./Mexico Borderlander all her life. Her formal education includes a Masters in Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1990) as well as graduate studies in Ethnohistory at the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Mexico City (1980) and in Social Anthropology, Universidad Ibero-Americana, Mexico City (1978). She is the Technical Director of the U.S. Mexico Border Health Association (USMBHA) responsible for all technical cooperation activities. She is also the founding associate of the Border Planning and Evaluation Center, a collaborative of public health specialists that fosters cooperation between academics and the community to strengthen processes and outcomes. During her tenure as Technical Director of the USMBHA, Ms. Ramos has been an innovator in public health, working primarily in the areas of substance abuse, HIV, TB, and diabetes. As head of the Technical Cooperation Division of the USMBHA she has coordinated over 300 health courses, seminars and symposia attended by an estimated 10,000 health and allied social services professionals. Ms. Ramos brought the USMBHA and the El Paso Community Foundation to partner for the development the Border AIDS Partnership whose mission is to increase funding for HIV/AIDS education, prevention, and care services in border counties. She is also President of Compañeros International, affiliated with the NGO Programa Compañeros which provides harm reduction services for injection drug users in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Ms. Ramos has received several awards for her work, including recognition in 1998 by Healthcare Forum/Healthier Communities for outstanding efforts to improve community health status and being named a 2001 Border Health Hero from the Pan American Health Organization.

Carlos Magis-Rodríguez, M.D., M.P.H.

Dr. Carlos Magis-Rodríguez is a physician and epidemiologist who has been working in the epidemiology of HIV since 1988 in the Mexican Ministry of Health. From 1990 to 1994 he was in charge of the National AlDS Case Registry. Since 1996, Dr. Magis-Rodríguez has been in charge of research at CONASIDA (Centro Nacional para la Prevención y Control del VIH/SIDA—The National Center for the Prevention and Control of AIDS). Since 1993 he has been interested in injection drug use and HIV. In 1996 he began a risk intervention project on the U.S.-Mexico border. The project was conducted in two different cities with incarcerated users and individuals who sought treatment in different NGO’s (non-governmental organizations). Dr. Magis-Rodríguez has presented in many diverse national and international HIV/AIDS meetings, and has published numerous papers and books on HIV/AIDS in Mexico. Recently he has participated in HIV/AIDS meetings sponsored by the University of California Office of the President (UCOP) and other agencies to address issues of mutual interest for researchers working on both sides of the California/Mexico border.

Jesus Bucardo, M.D., M.P.H.

Jesus Bucardo, M.D., M.P.H. is Assistant Clinical Professor at the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. He obtained his medical degree from the Universidad Autonoma de Baja California and his public health degree from San Diego State University. He completed his psychiatry residency training at UCSD and postdoctoral training at the UCSF-Center for AIDS Prevention Studies. He maintains a clinical practice with focus on cultural and community psychiatry at UCSD in a community mental health center near the U.S.-Mexico border. His current research interests include cultural adaptation of prevention interventions, psychosocial rehabilitation in schizophrenia, cultural psychiatry and use of traditional and alternative medicine methods in psychiatry with Latino populations in Mexico and the United States.

Thomas L. Patterson, Ph.D.

Dr. Thomas L. Patterson is a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. He received his Ph.D. in Comparative Psychology from the University of California, Riverside in 1977. Since that time he has conducted research in a number of areas including HIV/AIDS prevention, rehabilitation of older patients with psychosis, and stress responses of caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dr. Patterson has been conducting psychosocial research with HIV-positive populations since 1989. He is the Principal Investigator of a U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) funded sexual risk reduction intervention for “at risk” female sex workers in four Mexican cities along the U.S./Mexico border. In addition, he is Principal Investigator of a National Institute on Drug Abuse funded project testing a risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Dr. Patterson is also the principal investigator of an NIMH-funded sexual risk reduction intervention for HIV-negative, heterosexually-identified, meth-using men and women. He has published many papers and chapters in the field and serves on a number of AIDS review committees. Dr. Patterson is currently the editor of the journal AIDS and Behavior, and has served as co-editor and on the editorial boards of a number of other journals.

Steffanie A. Strathdee, Ph.D.

Dr. Steffanie A. Strathdee is an infectious disease epidemiologist who has spent the last two decades focusing on underserved, marginalized populations in developed and developing countries. Since January, 2004, she has been the Harold Simon Chair and Chief of the Division of International Health and Cross Cultural Medicine in the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at UCSD. Her recent work has focused on the prevention of blood borne infections and barriers to care among injection drug using populations, specifically HIV and viral hepatitis. In the last decade, she has published over 170 peer-reviewed publications on HIV prevention and the natural history of HIV infection. She is the principal investigator of several behavioral intervention studies among drug users, and has played a leading role in evaluations of needle exchange programs in Canada, the United States and India. Currently, she is engaged in research projects in a number of international settings, including Mexico, Brazil, Canada, Pakistan, India, Tajikistan and Russia. She is also principal investigator of a five year grant to characterize the epidemiology of blood borne infections among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Her projects have been funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and USAID.

Bibliography

- Astorga LA. Drug trafficking in Mexico: a first general assessment. [Accessed December 12, 2004];Management of Social Transformations - Discussion Paper No. 36. 1999 from http://www.unesco.org/most/astorga.htm.

- Badillo AR, Magis-Rodríguez C, Ortiz-Mondragon R, Lozada-Romero R, Uribe-Zúñiga PE. Int Conf AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. Persons who injecting drug in treatment and prisoners in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Brogly SB, Tyndall MW, Lamothe F, Franco EL. Intensity of drug injection as a determinant of sustained injection cessation among chronic drug users: the interface with social factors and service utilization. Addiction. 2004;99(6):727–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Lamothe F, Franco E, Lachance N, Desy M, Soto J, Vincelette J. High rates of HIV infection among injection drug users participating in needle exchange programs in Montreal: results of a cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997;146(12):994–1002. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Lamothe F, Soto J, Lachance N, Vincelette J, Vassal A, Franco EL. Sex-specific determinants of HIV infection among injection drug users in Montreal. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2001;164(6):767–773. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucardo J, Brouwer KC, Magis-Rodriguez C, Ramos R, Fraga M, Gracia Perez S, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Historical Trends in the Production and Consumption of Illicit Drugs in Mexico: Implications for the Prevention of Blood Borne Infections. Drug Alc. Depend. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscema M, Intraligi M, Bricolo R. Artificial neural networks for drug vulnerability recognition and dynamic scenarios simulation. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(3):587–623. doi: 10.3109/10826089809115887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Stoneburner RL, Hildebrandt DS, Ewing WE, Telzak EE, Jaffe HW. Heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 associated with the use of smokable freebase cocaine (crack) AIDS. 1991;5(9):1121–1126. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Amphetamine and Methamphetamine Emergency Department Visits, 1995–2002. 2004a [Google Scholar]

- Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Mortality Data From DAWN, 2002. Rockville, MD: 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza CT, Diaz T, Sutmoller F, Bastos FI. The association of socioeconomic status and use of crack/cocaine with unprotected anal sex in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002;29(1):95–100. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200201010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) [Accessed June 7, 2004];The South American cocaine trade: an "industry" in transition. 1996 June; from http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/intel/cocaine.htm.

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) [Accessed Jan 19, 2005];Drug trafficking in the United States, Report DEA-01020. 2001 September; from http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/intel/01020/

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) [Accessed January 7, 2005];Country brief: Mexico, Report DEA-02035. 2002 from http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/intel/02035/02035.html.

- Drug Intelligence Agency. [Accessed December 14, 2004];Mexico: country profile for 2003, Drug Intelligence Report DEA-03047. 2003 from http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/intel/03047/03047.pdf.

- Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, McCoy CB, Word C, Serrano Y, Inciardi JA, Bowser BP, Schilling RF, Holmberg SD. Intersecting epidemics--crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331(21):1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque S, Edlin BR, McCoy CB, Word CO, Larsen SA, Schmid DS, Von Bargen JC, Serrano Y. Crack cocaine smoking and oral sores in three inner-city neighborhoods. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1996;13(1):87–92. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finckenauer JO, Fuentes JR, Ward GL. Mexico and the United States: neighbors confront drug trafficking. [Accessed March 27, 2004];National Institute of Justice Publications. 2001 from http://www.ojp.gov/nij/international/trafficking_text.html.

- Garcia-Garcia ML, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Jimenez-Corona ME, Ponce-de-Leon A, Jimenez-Corona A, Bobadilla-del Valle M, Palacios-Martinez M, Canales G, Sangines A, Jaramillo Y, Martinez-Gamboa A, Balandrano S, Valdespino-Gomez JL, Small P. [Drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Orizaba, Veracruz. Implications for the tuberculosis prevention and control program] Rev. Invest. Clin. 2001;53(4):315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Canada Gazette: Precursor Control Regulations; [Accessed Jan 19, 2005];Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. 2002 from http://canadagazette.gc.ca/partII/2002/20021009/html/sor359-e.html.

- Güereña-Burgueño F, Benenson AS, Bucardo Amaya J, Caudillo Carreno A, Curiel Figueroa JD. [Sexual behavior and drug abuse in homosexuals, prostitutes and prisoners in Tijuana, Mexico] Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 1992;24(1–2):85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammet TM, Hunt DE, Rhodes W, Smith C, Sifre S. AIDS Outreach to Female Prostitutes and Sexual Partners of Infections Drug Users, Final Report Prepared for Community Research Branch (CRB) and National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) Rockville, MA 20857: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Howard AA, Klein RS, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN. Crack cocaine use and other risk factors for tuberculin positivity in drug users. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35(10):1183–1190. doi: 10.1086/343827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Servicios de Salud Publica del Estado de Baja California ISESALUD. Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiologica de las Adicciones (SISVEA) [Addiction Epidemiologic Surveillance System] -Tijuana 2000–2002. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt KK, Gentile F, Gilbert BP, Aiken M. A cluster of tuberculosis among crack house contacts in San Mateo County, California. Am. J. Public Health. 1994;84(11):1834–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magis C, Badillo A. [Consumption of injectable drugs and HIV/AIDS in a rural population] In: Magis C, Bravo-García E, Carrillo A, editors. La otra epidemia: El SIDA en el área rural. Serie Ángulos del SIDA. [The other epidemic: AIDS in rural areas. Angles of AIDS Series] Mexico City: 2003. p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Magis-Rodriguez C, Ruiz-Badillo A, Ortiz Mondragon R, Lozada R, Ramos R, Ramos ME, Ferreira-Pinto J. Int Conf AIDS. South Africa: Durban; 2000. Injecting drug use and HIV/AIDS in two jails of the North border of Mexico. Abstract no. ThPeD5469. [Google Scholar]

- Magis-Rodriguez C, Ruiz-Badillo A, Ortiz-Mondragon R, Loya-Sepulveda M, Bravo-Portela MJ, Lozada R. [Accessed January 5, 2005];[Study of risk practices for infection with HIV/AIDS in drug injectors from the city of Tijuana, Baja California INSP-CENIDS] 2002 from http://bvs.insp.mx/componen/svirtual/ppriori/09/0399/arti.htm.

- Maxwell J, Cravioto P, Galvan F, Cortes M. Patterns of Drug use on the U.S.-Mexico Border; College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Annual Meeting; June 18–23; Orlando, FL, U.S.A. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora ME, Rojas E, Juarez F, Berenzon S, Carreno S, Galvan J, Villatoro J, Lopez E, Olmedo R, Ortiz E, Nequis G. [Consumption of psychotropic substances in a Mexican junior and senior high school population] Salud Mental. 1993;16(3):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora ME, Guiot Rojas E. [Demand of drugs: Mexico in the international perspective] Salud Mental. 2003;26(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Melbye K, Khamboonruang C, Kunawararak P, Celentano DD, Prapamontol T, Nelson KE, Natpratan C, Beyrer C. Lifetime correlates associated with amphetamine use among northern Thai men attending STD and HIV anonymous test sites. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita F, Kral A, Reingold A, Bueno R, Trigueiros D, Araujo PJ. Trends of HIV infection among injection drug users in Brazil in the 1990s: the impact of changes in patterns of drug use. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2001;28(3):298–302. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200111010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita F, Kral A, Reingold A, Haddad I, Sanches M, Turienzo G, Piconez D, Araujo P, Bueno R. Overdoses among cocaine users in Brazil. Addiction. 2001;96(12):1809–1813. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9612180910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organización de Estados Americanos. [Accessed June 1, 2005];[Inter-American Observatory on Drugs - Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD): Statistical Drug Summary 2004] 2004 from http://www.cicad.oas.org/oid/Estadisticas/resumen2004/indiceesp.htm.

- Ortiz A, Soriano A, Galván J, Rodriguez E, González L, Unikel C. [Characteristics of cocaine users, their perception and attitude towards treatment services] Salud Mental. 1997;20(Suppl):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson T, Semple SJ, Zians JK, Strathdee SA. Methamphetamine-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men: Correlates of polydrug use. J. Urban Health. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti031. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Bucardo J, DelaTorre A, Fraga M, Staines H, Amaro H, Magis C, Strathdee SA. A Comparison of Drug Use Patterns and HIV/STD Prevalence among Female Sex Workers in Two Mexican-U.S. Border Cities; 67th annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; June 18–23; Orlando, FL. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Quinones S. True tales from another Mexico: the Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino, and the Bronx. 1st ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 2001. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos RL, Ortega H. HIV Prevention Among Female Sex Workers. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Reding A. Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Sep 17, 1995. The Fall and Rise of the Drug Cartels: With Colombia’s Kingpins Nabbed, America Faces More Elusive Targets in Mexico. Outlook. p.^pp. [Google Scholar]

- Remis RS, Bruneau J, Hankins CA. Enough sterile syringes to prevent HIV transmission among injection drug users in Montreal? J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1998;18(Suppl 1):S57–S59. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JR, Bretz SW, Johnson EB, Turnipseed SD, Brofeldt BT, Derlet RW. Methamphetamine abuse and emergency department utilization. West. J. Med. 1999;170(4):198–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MT, Strathdee SA, Cornelisse PG, Currie S, Patrick DM, Rekart ML, O’Shaughnessy MV. Do needle exchange programmes increase the spread of HIV among injection drug users?: an investigation of the Vancouver outbreak. AIDS. 1999;13(6):F45–F51. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Binge use of methamphetamine among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: pilot data and HIV prevention implications. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2003;15(2):133–147. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.133.23835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. A comparison of injection and non-injection methamphetamine-using HIV positive men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(2):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Peck J, Reback CJ, Rotheram-Fuller E. Psychiatric and substance dependence comorbidities, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk behaviors among methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men seeking outpatient drug user treatment. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(Suppl 1):161–168. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Toro MC. Drug Trafficking in Mexico. In: Bosworth B, Collins SM, Lustig N, Institution B, editors. Coming together?: Mexico-United States relations. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press; 1997. pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Spittal PM, Bruneau J, Craib KJ, Miller C, Lamothe F, Weber AE, Li K, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Surviving the sex trade: a comparison of HIV risk behaviours among street-involved women in two Canadian cities who inject drugs. AIDS Care. 2003;15(2):187–195. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia (SSA) [Accessed February 14, 2004];[National Survey of Addictions. Epidemiologic Data.] 1998 from http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/conadic/epidem.htm.

- Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia (SSA) [Accessed January 7, 2005];Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de las Adicciones (SISVEA) 2002 Informe 2002. [Addiction Epidemiologic Surveillance System. 2002 Report], from http://www.epi.org.mx./sis/descrip.htm.

- Statistics Canada. [Accessed Jan 19, 2005];Canada's Alcohol and Other Drugs Survey. 1994 from http://www.statcan.ca/english/Dli/Data/Ftp/cads/cads1994.htm.

- Strathdee SA, Davila-Fraga W, Case P, Firestone M, Brouwer KC, Gracia Perez S, Magis-Rodriguez C, Fraga MA. "Vivo para consumirla y la consumo para vivir" ["I live to inject and inject to live"]: High Risk Injection Behaviors in Tijuana, Mexico. J Urban Health. 2005 doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti108. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Galai N, Safaiean M, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Johnson L, Nelson KE. Sex differences in risk factors for HIV seroconversion among injection drug users: a 10-year perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(10):1281–1288. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PG, Rekart ML, Montaner JS, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11(8):F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia-Conyer R, Cravioto P, de la Rosa B, Galvan F, Medina-Mora ME. [Natural history of cocaine consumption: the case of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua] Salud Mental. 2003;26(2):12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17(6):887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime UNODC. World Drug Report. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) [Accessed March 17, 2004];Country Profile: Mexico. 2003 from http://www.unodc.org/pdf/mexico/country_profile_mexico.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed January 27, 2005];Foreign Trade Statistics: Top Ten Countries with which the U.S. Trades (YTD DEC99) 2002 from http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/top/dst/1999/12/balance.html.

- U.S. Customs Service. [Accessed March 17, 2004];Office history. 2004 from http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/cas/HTML/office_history.html.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2004

- Valdez A, Cepeda A, Kaplan CD, Codina E. Sex work, high-risk sexual behavior and injecting drug use on the U.S.-Mexico border: Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. Houston, TX: Office for Drug and Social Policy Research, Graduate School of Social Work, University of Houston; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Villatoro JA, Medina-Mora ME, Juarez F, Rojas E, Carreno S, Berenzon S. Drug use pathways among high school students of Mexico. Addiction. 1998;93(10):1577–1588. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9310157715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, Donnell D, Seage GR, Metzger D, Marmor M, Koblin BA, Buchbinder S, Gross M, Stone B, Judson FN. Non-injection substance use correlates with risky sex among men having sex with men: data from HIVNET. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;53(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Larson DF, Watson RR. Heart disease, methamphetamine and AIDS. Life Sci. 2003;73(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]