How does auditory cortex represent auditory stimuli, and how do these representations contribute to behavior? Recent experimental evidence suggests that activity in auditory cortex consists of sparse and highly synchronized volleys of activity, observed both in anesthetized and awake animals. Many neurons are capable of remarkably precise activity with very low jitter or spike count variability. Most importantly, animals are capable of exploiting such precise neuronal activity in making sensory decisions. Whether the ability of auditory cortex to exploit fine temporal differences in cortical activity is unique to auditory modality, or represents a general strategy used by cortical circuits remains an open question.

Sparse vs. dense population coding in auditory cortex

Almost 50 years ago, Hubel and Wiesel showed that many neurons in the primary visual cortex could be driven to fire at high rates by appropriately tailored “optimal” stimuli such as oriented bars. Optimal stimuli capable of driving neurons in other visual areas, such as area MT, were later identified. These and other findings have led to what is the de facto standard model of visual coding and processing. According to this model, population representations in the visual cortex are “dense,” consisting of many simultaneously active neurons with broad receptive fields, each contributing to the population response in a similar manner. This model of dense representations is the starting point for most thinking about cortical representations.

Although the model of dense representations has guided decades of fruitful research on coding in the visual system, it has not been as successfully applied to the auditory cortex. One reason is that it has been difficult to identify optimal stimuli capable of driving auditory cortex neurons to fire sustained trains of action potentials. As a result, the focus has been on the initial transient responses elicited at the onset of a stimulus (1, 2). Thus for many years it appeared that the auditory and visual systems might use different strategies to represent stimuli. According to this view, population representations in the auditory cortex are “sparse,” consisting of only a handful of rather selective neurons active at any given moment.

Which stimuli are optimal for single neurons and how the stimuli are represented across neuronal populations are complementary questions. Optimal stimuli provide an answer to a question: “What are the acoustic features that drive the particular neuron the most?” Identification of an optimal auditory stimulus would be very useful for the experimenter for a number of reasons. For example, it would allow her to study the topography of cortical representations across the auditory cortex. However, the fact that a particular neuron can be driven at a high rate when presented with an optimal sound says little about how that sound—or sounds in general—is represented across a population of neurons. A complementary question is therefore: “What is the typical response across the entire population to a particular stimulus?” This second question emphasizes more the point of view of the animal's brain.

The simple view of a dichotomy between visual and auditory representations has recently been challenged. It has long been clear that responses in the auditory cortex of anesthetized animals differ from those in awake animals. Whereas in the anesthetized animal sound-evoked responses are typically transient, in the awake animal both transient and sustained responses can be observed. The difference between responses in the anesthetized and awake preparations was noted in even the earliest electrophysiological studies of auditory cortex (3): “The search for correlates for the steady state [responses toward tones] at the cortical level has to a large extent been unsuccessful, and for such information as we do possess we have to thank those who have used unanesthetized preparations.” With the resurgence of work in the awake preparations in the last decade (4**), many researchers have emphasized the rich repertoire of neuronal responses in awake animals, often with a particular focus on sustained responses to sounds (5—7).

The observation that in the unanesthetized auditory cortex there are some neurons capable of sustained firing raised the possibility that some simple class of optimal stimuli, analogous to visual edges, might be identified. However, although a substantial fraction of neurons in auditory cortex can be driven at high rates (7**), the optimal stimuli needed to drive different neurons are very diverse: optimal stimuli must be carefully tailored for most neurons. Moreover, nearby neurons are not driven by the same optimal stimuli

The sparseness of representations in auditory cortex of awake head-fixed rats was recently estimated by sequentially sampling single neurons (8*). Neuronal activity was assessed using cell-attached recording methods. Unlike conventional extracellular recording methods (e.g. with a high-impedance tungsten electrode) which rely on a sufficient number of large well-isolated spikes to identify a neuron, cell-attached recording relies on physical contact between the glass recording pipette and the target neuron. For this reason cell-attached recording is not prone to bias recordings toward neurons with high firing rates. Hromádka and colleagues found that for a variety of simple and complex (“natural”), the typical response of in auditory cortex is sparse; only 5% of neurons responded to any given stimulus. Thus, although for any given neuron there might be an optimal stimulus which drives the neuron well, most stimuli are not optimal for most neurons and are represented sparsely across the population.

Sparse representations may not be limited to the auditory cortex. Recent evidence supports the view that responses in visual cortex may actually be sparse rather than dense (9, 10). Sparse representations have also been proposed for the barrel (11, 12) and olfactory (13) systems. It has been argued on computational grounds that sparse representations offer several advantages over dense representations. For example, sparse patterns of cortical activity are easier to “read-out,” in a same way that a few fans shouting in an otherwise silent crowd during a curling match are easier to identify than many people talking slightly louder in audience watching a soccer game. Sparse cortical patterns are also easier to learn with a simple variant of Hebbian learning, simply because the presence of very few very active neurons (in a model) tends to strengthen the same set of synapses.

Auditory cortical responses are precise

There are two common measures of the variability with which single neurons represent sensory stimuli. The first is a measure of timing precision, or “jitter,” of spikes. The jitter is defined by reference to some event, such as the onset or termination of a stimulus. The most reliable stimulus-locked spikes in visual cortex have a jitter of less than five milliseconds (14, 15) and the most reliable responses in auditory cortex have jitter of less than one millisecond (1, 2). Studies have suggested various roles for the precise spike timing in auditory cortex, for example in tracking fine temporal structure of complex sounds (16), or discriminating animal vocalizations (17).

Another measure of neuronal reliability is the trial-to-trial variability in spike count. In contrast to some areas of visual cortex in which spike count variability is usually high (18)—consistent with a Poisson process—in auditory cortex some neurons can control spike count very tightly. Indeed, some neurons generate either zero or one spike on each trial in response to certain stimuli. Such “binary” responses can be found in both the anesthetized (1*) and unanesthetized cortex (5, 8, 19). Note that binary in this context does not mean a given neuron cannot produce more than one spike. Indeed, the same neuron can generate binary responses to some stimuli but sustained responses to others (see e.g. the binary responses in (8), Fig. 2c). The significance of binary responses is that it implies that at least some cortical areas are capable of neuronal precision much higher than expected from previous analyses of visual cortical responses.

Subthreshold responses reflect synchronized cortical input

Cortical neurons typically receive input from thousands of other cortical neurons (20, 21). Whereas spiking activity of a given cortical neuron reflects neuronal output, the underlying subthreshold activity reflects the activity of the specific subpopulation of neurons that provide input to the neuron. Studying subthreshold fluctuations of membrane potential of cortical neurons in-vivo can thus provide us with a window on population dynamics of “relevant” neurons, i.e. of neurons connected to the neuron under study.

In-vivo whole-cell recordings in the auditory cortex of anesthetized and awake rats reveal that subthreshold activity is characterized by large, infrequent deviations in membrane potential (“bumps”) (22). Consistent with sparse representations, these bumps indicate that the presynaptic neuronal population for any given neuron is characterized by extended quiet periods interrupted by brief and highly synchronous periods of intense activity. These bumps are consistent with sparse representations. Similar bumps have also been described in visual (23, 24) and barrel cortex (25).

Auditory cortex activity and behavior

As outlined above, representations in the auditory cortex consists of precise, sparse, and synchronous neuronal activity. How are these representations related to behavior? The data considered so far, whether recorded in the anesthetized or awake preparation, involved measuring the effect on neural responses of manipulating acoustic stimuli. To determine the relationship between neural activity and behavior requires a paradigm in which the animal's behavior is also manipulated.

From the earliest experiments it has been clear that neural activity in the auditory cortex depends on the animal's behavioral state (26). An important step toward understanding how changes in neuronal activity might contribute to auditory discrimination came from the discovery that attention to a particular target sound can change the response properties of neurons in the auditory cortex, for example by shifting their spectral tuning (27**). Interestingly, although attention can enhance the neuronal response to a particular frequency, simply engaging in an auditory task suppresses responses when compared to the baseline response recorded in the passive condition (28).

Most experimental paradigms seeking to relate neural activity to behavior rely on correlations: the behavioral contingencies are manipulated and concomitant changes in neural activity are detected. Although such experiments are suggestive, they do not establish a causal role for the correlations detected; these correlations could in principle be epiphenomena. To establish a causal role for neural activity in perception requires an experimental design in which neural activity is manipulated to cause behavior changes, as in the classical microstimulation experiments in area MT (29). Two recent experiments have used this microstimulation approach to probe the lower limit on the number of neurons in barrel cortex needed to drive behavior (30, 31)**.

Microstimulation has recently been used to probe the temporal limits of representations in auditory cortex (32*). As noted above, neurons can lock with millisecond precision to the fine timing of some stimuli. However, the tight temporal correlation between the acoustic stimulus and the neuronal response in auditory cortex does not imply that such time-locked neuronal responses can be used by the animal to generate a behavioral response. To determine whether such finely time-locked cortical responses can be exploited by the animal, Yang and colleagues implanted electrodes into the auditory cortex of rats and then trained these animals to distinguish patterns of microstimulation. Animals could reliably differentiate between stimuli in which timing differed by as little as three milliseconds. The result that fine timing can be exploited by the animal suggests that it may play a role in representations in auditory cortex.

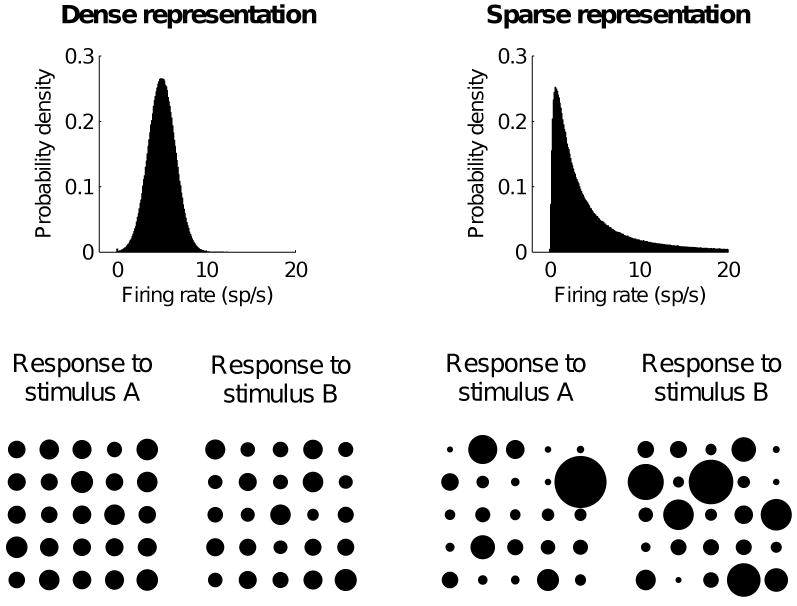

Figure 1.

Sparse representations provide more reliable stimulus discrimination. Firing rates in dense representation (left) are drawn from a hypothetical Gaussian distribution, whereas firing rates in sparse representation (right) are drawn from a lognormal distribution. Lower panels illustrate two firing rate patterns of 25 neurons drawn randomly from corresponding distributions (each circle corresponds to a single neuron, and its area is proportional to the neuron's firing rate). The firing rate patterns drawn from sparse distribution are dominated by a few outliers---a few neurons with high firing rates---which could be used to easily discriminate stimulus A from stimulus B. On the other hand, patterns drawn from dense distribution are very similar as all neurons have very similar firing rates.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1*.DeWeese MR, Wehr M, Zador AM. Binary spiking in auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(21):7940–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07940.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First report demonstrating that spike-count variability of cortical neurons can be much lower than previously suspected. The authors identified a population of “binary” neurons with very low spike-count variability, thus ruling out Poisson model as a universal description of cortical activity. Many neurons also exhibited extremely high spike time reliability with jitter of less than one ms.

- 2.Heil P. First-spike latency of auditory neurons revisited. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(4):461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galambos R. Neural mechanisms of audition. Physiological Review. 1954;34:497–522. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1954.34.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4**.Lu T, Liang L, Wang X. Temporal and rate representations of time-varying signals in the auditory cortex of awake primates. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(11):1131–8. doi: 10.1038/nn737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identified a population of cortical neurons in the awake marmoset which exhibit sustained firing in response to fast click trains. Such sustained firing is rarely seen in many standard anesthetized preparations.

- 5.Barbour DL, Wang X. Auditory Cortical Responses Elicited in Awake Primates by Random Spectrum Stimuli. J Neurosci. 2003;23(18):7194–7206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07194.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaese BH, Ostwald J. Complexity and temporal dynamics of frequency coding in the awake rat auditory cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(9):2638–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Wang X, Lu T, Snider RK, Liang L. Sustained firing in auditory cortex evoked by preferred stimuli. Nature. 2005;435(7040):341–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; By varying frequency, bandwidth, amplitude modulation, and frequency modulation, the authors showed that many neurons in auditory cortex of awake marmosets were capable of sustained firing in response to their “preferred” stimuli, while responding transiently to their “non-preferred” stimuli.

- 8*.Hromádka T, Deweese MR, Zador AM. Sparse representation of sounds in the unanesthetized auditory cortex. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(1):e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors used cell-attached recordings in auditory cortex of awake head-fixed rats to estimate population response to simple and complex sounds. Only about 5% of neurons responded vigorously at any given moment, suggesting that population activity was sparse.

- 9.Vinje WE, Gallant JL. Sparse coding and decorrelation in primary visual cortex during natural vision. Science. 2000;287(5456):1273–6. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Sparse coding of sensory inputs. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(4):481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brecht M, Schneider M, Sakmann B, Margrie TW. Whisker movements evoked by stimulation of single pyramidal cells in rat motor cortex. Nature. 2004;427(6976):704–10. doi: 10.1038/nature02266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr JN, Greenberg D, Helmchen F. Imaging input and output of neocortical networks in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):14063–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinberg D, Koulakov A, Gelperin A. Sparse odor coding in awake behaving mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26(34):8857–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0884-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bair W, Koch C. Temporal precision of spike trains in extrastriate cortex of the behaving macaque monkey. Neural Comput. 1996;8(6):1185–202. doi: 10.1162/neco.1996.8.6.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buracas GT, Zador AM, DeWeese MR, Albright TD. Efficient discrimination of temporal patterns by motion-sensitive neurons in primate visual cortex. Neuron. 1998;20(5):959–69. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhilali M, Fritz JB, Klein DJ, Simon JZ, Shamma SA. Dynamics of precise spike timing in primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24(5):1159–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3825-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnupp JW, Hall TM, Kokelaar RF, Ahmed B. Plasticity of temporal pattern codes for vocalization stimuli in primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26(18):4785–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4330-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. The variable discharge of cortical neurons: implications for connectivity, computation, and information coding. J Neurosci. 1998;18(10):3870–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03870.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chimoto S, Kitama T, Qin L, Sakayori S, Sato Y. Tonal response patterns of primary auditory cortex neurons in alert cats. Brain Res. 2002;934(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braitenberg V, Schuz A. Cortex: statistics and geometry of neuronal connectivity. Berlin: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binzegger T, Douglas RJ, Martin KAC. A Quantitative Map of the Circuit of Cat Primary Visual Cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24(39):8441–8453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1400-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeWeese MR, Zador AM. Non-gaussian membrane potential dynamics imply sparse, synchronous activity in auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12206–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2813-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampl I, Reichova I, Ferster D. Synchronous membrane potential fluctuations in neurons of the cat visual cortex. Neuron. 1999;22(2):361–74. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson J, Lampl I, Reichova I, Carandini M, Ferster D. Stimulus dependence of two-state fluctuations of membrane potential in cat visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(6):617–621. doi: 10.1038/75797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okun M, Lampl I. Instantaneous correlation of excitation and inhibition during ongoing and sensory-evoked activities. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(5):535–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubel DH, Henson CO, Rupert A, Galambos R. “Attention” Units in the Auditory Cortex. Science. 1959;129:1279–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.129.3358.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Fritz J, Shamma S, Elhilali M, Klein D. Rapid task-related plasticity of spectrotemporal receptive fields in primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(11):1216–23. doi: 10.1038/nn1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper studied effect of attention on response properties of single neurons in auditory cortex. In behaving ferrets, the authors demonstrated that attention can rapidly and adaptively reshape receptive field properties as determined by estimating spectrotemporal receptive fields (STRFs).

- 28.Otazu GH, Tai L, Yang Y, Zador AM. Engaging in an auditory task suppresses responses in auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12 doi: 10.1038/nn.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salzman CD, Britten KH, Newsome WT. Cortical microstimulation influences perceptual judgements of motion direction. Nature. 1990;346(6280):174–7. doi: 10.1038/346174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.Houweling AR, Brecht M. Behavioural report of single neuron stimulation in somatosensory cortex. Nature. 2008;451(7174):65–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Huber D, Petreanu L, Ghitani N, Ranade S, Hromádka T, Mainen Z, Svoboda K. Sparse optical microstimulation in barrel cortex drives learned behaviour in freely moving mice. Nature. 2008;451(7174):61–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first reports establishing that even a few cortical spikes are sufficient to drive behavioural decisions. Houweling and Brecht (29) trained rats to detect a low-intensity cortical microstimulation in somatosensory cortex and showed that rats could detect even single neuron stimulation. Huber and colleagues (30) introduced channelrhodopsin-2 to a small fraction of layer 2/3 neurons in somatosensory cortex of mice and showed that animals could detect brief epochs of cortical activity in as few as sixty neurons.

- 32*.Yang Y, DeWeese MR, Otazu GH, Zador AM. Millisecond-scale differences in neural activity in auditory cortex can drive decisions. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(11):1262–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang and colleagues trained rats to discriminate patterns of cortical microstimulation delivered by chronically implanted electrodes. The authors showed that timing differences as low as three ms can be detected and used to drive animal's behaviour.