Abstract

Anthrax Lethal Toxin (LeTx) demonstrates potent MAPK pathway inhibition and apoptosis in melanoma cells that harbor the activating V600E B-RAF mutation. LeTx is composed of two proteins, PA and LF. Uptake of the toxin into cells is dependent upon proteolytic activation of PA by the ubiquitously expressed furin or furin-like proteases. In order to circumvent nonspecific LeTx activation, a substrate preferably cleaved by gelatinases was substituted for the furin LeTx activation site. Here we have shown the toxicity of this MMP-activated LeTx is dependent on host cell surface MMP-2 and −9 activity as well as the presence of the activating V600E B-RAF mutation, making this toxin dual specific. This additional layer of tumor cell specificity would potentially decrease systemic toxicity from the reduction of nonspecific toxin activation while retaining anti-tumor efficacy in patients with V600E B-RAF melanomas. Moreover, our results indicate that cell surface-associated gelatinase expression can be used to predict sensitivity among V600E B-RAF melanomas. This finding will aid in the better selection of patients that will potentially respond to MMP-activated LeTx therapy.

Keywords: anthrax lethal toxin, B-RAF, lethal factor, matrix metalloproteinase, protective antigen

Introduction

Chemotherapeutic regimens have limited activity in metastatic melanoma patients. Response rates are currently between 10 and 25% with median survival of 8 months for single agent dacarbazine (DITC) and no apparent benefit can be seen with polychemotherapy or biochemotherapy (1). Furthermore, interleukin-2 and interferon alfa addition to chemotherapy improves response rate and progression-free survival only in a select few patients (1). The poor clinical performance of these traditional treatments has lead to the development of agents that specifically target protein components of molecular pathways that drive melanoma proliferation and dissemination. Mutations leading to the constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway are common in melanoma. A specific valine to glutamic acid substitution at amino acid position 600 of the B-RAF protein component constitutively activates this pathway, resulting in loss of cell proliferation control (2). Enzymes implicated in melanoma metastasis are matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The extracellular matrix degrading function of these enzymes positively correlates with poor prognosis in melanoma patients (3). Further, activation of MAPK in melanomas causes increased MMP expression (4). Small molecular weight inhibitors which separately target these two pathways have been tested in melanomas, but have yielded little clinical benefit (2, 4). We therefore sought a more potent agent which targets these tumor systems.

We examined recombinant toxin compounds for melanoma therapy based on their extreme catalytic potency and the prior experience of our laboratories. Anthrax lethal toxin (LeTx), secreted from the gram positive Bacillus anthracis, demonstrates potent MAPK pathway inhibition (5). LeTx is composed of two proteins, the 83-kD protective antigen (PA) and the 90-kD lethal factor (LF). Toxin uptake into cells is dependent upon proteolytic activation of PA by ubiquitously expressed furin or furin-like proteases after PA binding to one of two widely expressed receptors, Capillary Morphogenesis Gene 2 (CMG2) and Tumor Endothelial Marker 8 (TEM8) (6). The activated PA subsequently heptamerizes, binds three LF molecules, and migrates into lipid rafts where subsequent internalization occurs. Progressive acidification of the early endosome induces PA heptamer pore formation and subsequent LF escape into the cytosol (7). The catalytic activity of LF causes the cleavage and inactivation of the MEKs, with the exception of MEK5, and thus the complete inhibition of all 3 branches of the MAPK pathway (8). LeTx induces cell cycle arrest and triggers apoptosis in human melanoma cells (9–10). However, specificity both in tissue culture and animal models was limited due to the presence of receptors on many normal tissues and the ubiquitous expression of furin. Hence we needed to provide an additional layer of specificity to LeTx to improve the melanoma therapeutic index in vivo.

Efforts have recently been taken to enhance the specificity of LeTx (11–12). Liu et al. modified LeTx by changing the furin cleavage sequence of PA, 164RKKR167, to a gelatinase (MMP-2/-9) selective cleavage sequence, 164GPLGMLSQ171. The engineered PA, PA-L1, when combined with LF retained melanoma cell cytotoxicity (11). In addition, it was three-fold less toxic to mice and had a 20-fold longer circulating half-life (11). At maximal tolerated doses (MTD), human C32 melanoma xenografts showed 90% tumor growth inhibition and 30% complete regressions with PA-L1/LF but no tumor growth inhibition with LeTx. The theoretical dual specificity of PA-L1/LF should provide a safe and effective melanoma therapeutic for a specific subset of patients. To confirm the molecular mechanism of the drug and identify biomarkers for patient identification, we undertook this study to examine the potency of PA- L1/LF in a series of human melanoma cell lines. Cell sensitivities to PA-L1/LF were correlated with the MMP-2/-9 activity levels as well as the presence of the B-RAF V600E mutation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

PA, PA-L1, LF, FP59, and LF-β-Lac were produced as previously described (13–15). FP59 consists of the first 254 amino acids of LF (the PA/PA-L1 binding domain) fused to the catalytic portion of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (amino acids 362–613) (15). FP59 when internalized in a PA/PA-L1 dependent mechanism inhibits protein synthesis and thus is toxic to all cells (15). The fusion protein LF-β-Lac consists of the PA binding domain of LF genetically fused to the β-Lactamase enzyme (13).

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The melanoma cell lines WM793B, WM46, WM983A, WM51, WM902B, WM1158, WM239A, WM3211, WM852, WM1361A are from the Wistar Institute collection and were maintained in 2% Tumor Medium (4:1 MCDB153 with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate and Leibovitz’s L-15 medium with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.005 mg/ml bovine insulin, 1.68 mM CaCl2, 2% fetal bovine serum). Cell lines C32, SK-MEL-24, WM115, Malme-3M, HT-144, WM-266–4, A2058, A375, 1205Lu, 451Lu, G361, A101D, SK-MEL-28, and SK-MEL-2 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown as recommended. The cell line SK-MEL-173 was provided by Dr. Alan Houghton (Sloan Kettering, New York, NY) and cultured in RPMI1640 +10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The 3H-thymidine incorporation inhibition assay was utilized as described previously (10). Briefly, cell lines were progressively weaned from serum-containing medium to AIMV serum-free media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Ten thousand cells per well were plated in 25% recommended medium/ 75% AIMV in Costar 96-well flat bottomed plates. Cells were allowed to adhere to the plate, and the medium was exchanged for 100% AIMV containing 1 nM LF/FP59. Serially diluted PA/PA-L1 ranging from a final concentration of 0–10,000 pmols/liter was added. After 48 hours at 37°C/5% CO2, one microcurie of 3H-thymidine (NEN DuPont, Boston, MA) in 50 µL of AIMV per well was added and incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for an additional 18 hours. The cells were then harvested with a Skatron Cell Harvestor (Skatron Instruments, Lier, Norway) onto glass fiber mats, and counts per minute (CPM) of incorporated 3H-thymidine were quantified using an LKB liquid scintillation counter gated for 3H (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Concentration of toxin that inhibited 3H-thymidine incorporation by 50% compared to control wells defined the IC50. The percent maximal 3H-thymidine incorporation was plotted versus the log of the toxin concentrations, and nonlinear regression with a variable slope sigmoidal dose-response curve was generated along with IC50 using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). Assays were performed in triplicate with IC50 variability between assays less than 30%.

PA-L1/LF-β-Lac FRET Flow Cytometry

Two hundred and fifty thousand cells per well were plated in a Costar 12-well plates in 25% recommended medium/75% AIMV. Cells were allowed to adhere to the plate at 37°C/5% CO2, washed once with AIMV, and fresh AIMV medium was added. Cells were then incubated overnight at 37°C/5% CO2. 90 nM LF-β-Lac alone or 26 nM PA-L1/90 nM LF-P-Lac was added to the conditioned medium and incubated for 5 hours at 37°C/5% CO2. Cells were then washed twice with AIMV and loaded with CCF-2/AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark using the alternative loading protocol as described by the manufacturer. After 4 washes with AIMV/2 mM Probencid (Sigma, St Louis, MO) the culture medium was replaced with AIMV/2 mM Probencid, which was incubated at room temperature in the dark for an additional 75 minutes to allow for FRET disruption. Cells were then trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), washed twice with ice-cold Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 2 mM Probencid, and resuspended in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution/2 mM Probencid at a concentration of 500,000 cells/ml. Analysis was performed using BD FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and data was analyzed by Diva (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cell lines were compared by using the mean blue fluorescence intensity of the PA-L1/LF-β-Lac treated cells, which was adjusted for nonspecific CCF-2/AM cleavage using the mean blue fluorescence of the LF-β-Lac treated negative controls, and subsequently divided by the mean green fluorescence of the LF-β-Lac negative controls adjusted for auto fluorescence of unstained, untreated controls, times 100 to generate percent control mean blue fluorescence.

PA-L1/LF-β-Lac FRET Microscopy

The PA-L1/LF-β-Lac FRET disruption assay was visualized via fluorescent microscopy. Two hundred thousand cells were plated in 8-well chamber slides (Lab-tek, Rochester, NY) in 25% recommended medium/75% AIMV. The cells were allowed to adhere, washed once with AIMV, and culture medium was replaced with AIMV. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C/5% CO2 and 26nM PAL1/90 nM LF-β-Lac was subsequently added to the conditioned edium. Cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for 5 hours. Cells were washed twice with AIMV, and loaded with CCF-2/AM using the alternative loading protocol as recommended by the manufacturer for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed four times with AIMV/2 mM Probencid, and incubated at room temperature for an additional 75 minutes to allow for FRET disruption in fresh AIMV/2mM Probencid. The culture medium was removed and the cells were visualized with a BX51 fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) fitted with excitation filter HQ405/20 nm bandpass, dichroic 425DCXR, emission filter HQ460/40nm (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) for blue fluorescence acquisition. For green image acquisition, excitation filter HQ405/20 nm bandpass, dichroic 425DCXR, emission filter HQ530/30nm (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) using a 10× objective for a total magnification of 100×. Images were obtained with a DP71 digital camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) using the same exposure time for each cell line and subsequently analyzed using DP manager (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Gelatin Zymography

Gelatin Zymography was performed as described previously (14). Briefly, for cell lysate analysis of MMP-2 –9 levels, 80–100% confluent T-150 flasks of cells were progressively weaned to 100% AIMV. Cells were lysed on ice for ten minutes using 1.5 ml lysis buffer per flask (0.5% (V/V) Triton X-100 in 0.1M Tris-HCl, pH 8.1), and removed with a rubber scrapper. Cell lysates were spun at 10,000 RPM using an Allegra 2502 centrifuge fitted with TA-10–250 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Cell lysate protein concentration was equilibrated to 0.65 mg/ml using the BCA procedure (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The lysate fraction contained plasma membrane sheets and vesicles, therefore MMP-2/-9 activities in the cell lysate were considered as cell surface gelatinase activities. For conditioned medium zymography, four million cells were incubated in 5 ml AIMV for 20 hours at 37°C/5% CO2. The culture medium was harvested and spun at 10,000 RPM at 4°C using an Allegra 2502 centrifuge fitted with TA-10–250 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). For concentration of gelatinases, conditioned medium/one milligram cell lysate protein was incubated with 50 µl gelatin sepharose beads (GE, St. Giles, UK) in equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% (V/V) Tween-20, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.6) for 1 hour at 4°C on an end-over-end mixer.

Cell Lysates/conditioned medium were spun at 500RCF for ten minutes at 4°C using a Microfuge 18 centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and resuspended in 500 µl Wash Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% (V/V) Tween-20, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.6). After 4 washes with Wash Buffer, beads were resuspended in 30 µl 2× Tris-Glycine sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and loaded in 10% gelatin zymogram gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gels were run at 125 mV for 90 minutes, and developed according to Invitrogen. Positive controls consisted of recombinant 68-kD pro-form (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and 62-kD active form (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) of MMP-2 and the 92-kD pro-form (Millipore, Billerica MA) and 83-kD active form (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) MMP-9. MMP-2/-9 band density was determined with the Fluorchem SP densitometer (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) and calculated as a percent of the intensity of the recombinant gelatinase. Total gelatinase activity was calculated as the average of the percent control standard MMP-2 and MMP-9 of each cell line.

Western Blot

Cells were seated in T-75 flasks and weaned to 100% AIMV. Cells were lysed in RIPA Lysis buffer (0.5 M Tris pH 7.4, 0.25% Triton X-100, 0.02 M sodium deoxycholate, 0.15 M sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA) plus complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Basal, Switzerland). Cell lysates were equilibrated using the BCA procedure (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to 2 mg/ml. Westerns were performed as described previously using primary antibodies for PTEN (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), MMP-1, and MT1-MMP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (10). Band intensity was determined by the Fluorchem SP densitometer (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Verification of equal loading was performed using an anti-β actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Melanoma MAPK Mutational Status

Melanoma cells were grown to approximately 80% confluence, trypsinized, and incubated at 55°C for 3 hr in DNA extraction buffer (400 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA) containing 50 µg/mL RNase A, 2% SDS, and 50 µg/mL Proteinase K. Cells were then sheared using an 18G needle, extracted twice in phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:25:1), and then choloroform extracted. DNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry at 260 nm after ethanol precipitation.

For B-RAF mutation analysis of both Exon 11 and 15, PCR on total DNA was carried out in the presence of 1 µM of both B-RAF forward primer Braf11F (5’ – CTCTCAGGCATAAGGTAAT GTAC – 3’) and B-RAF reverse primer Braf11R (5’ – GAGTCCCGACTGCTGTGAAC – 3’) for Exon 11. Exon 15 primers were forward primer Braf15F (5’ – TCATAATGCTTGCT CTG ATAGGA – 3’) and reverse primer Braf15R (5’ – GGCCAAAAATTTAATCAGTGGA – 3’). Reactions were performed in 50 µl volumes consisting of 5 µl of 10× PCR buffer, 300 nM of each nucleotide, 10 µL of 5X Q solution, and 1.25 U of Proofstart Taq (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Exon 11 amplification was performed by 95°C for 12 minutes followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 45 seconds, 54°C for 90 seconds, 72°C for 90 seconds, and a final extension cycle of 72°C 3 minutes. Exon 15 amplification was performed by 95°C for 12 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 45 seconds, 56°C for 90 seconds, 72°C for 90 seconds, and a final extension cycle of 72°C for 3 minutes.

For NRAS mutation analysis, 1 µM of the NrasX3F (5’ –CACACCCCCAGGATTCTTAC – 3’) and NrasX3R (5’ – GTTCCAAGTCATTCCCAGTAG – 3’) were used to amplify Exon 3. Reaction mixtures were identical to B-RAF gene amplification and subjected to 94°C 12 minutes followed by 8 cycles of 94°C 45 seconds. Annealing temperature was decreased from 65°C by 2° every 2 cycles to 59 °C for 90 seconds, followed by 72°C for 90 seconds, 25 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 57°C for 90 seconds, 72°C for 90 seconds, and a final extension cycle of 72°C for 3 minutes. Correct PCR product size (403 bp for B-RAF Exon11, 233 bp for B-RAF Exon15, 438 bp for NRAS Exon3) was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Sequences were verified using the ABI 3700-capillary electrophoresis DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Significance of correlations was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). All analyses were done assuming Gaussian populations with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

PA-L1/LF cytotoxicity to melanoma cells

We tested a panel of twenty-five melanoma cell lines for sensitivity to PA-L1/LF, PA/LF, and PA/FP59 (Table 1). FP59 consists of the PA binding domain of LF (amino acids 12–54) genetically fused to the ADP-ribosylation domain of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (amino acids 362–613) and is toxic to all cells in which it becomes internalized (15). Sensitivity to PA/FP59 indicated adequate LeTx receptor expression, while PA/LF sensitivity confirmed MAPK dependence of the target cell. Cytotoxicity analysis revealed that 12 out of 25 cell lines were sensitive to PA-L1/LF. From our experience in clinical application of immunotoxins, we arbitraly set sensitivity at an IC50 < 200 pmol/L with < 10% of control 3H thymidine incorporation at 10 nM PA-L1/1 nM LF (Table 1a) (16). In determining the cause of PA-L1/LF resistance in the remaining 13 insensitive cell lines (Table 1b and c), both PA/FP59 and PA/LF cytotoxicity were compared. With the exception of SK-MEL-2 (PA/FP59 IC50 130 pmol/L), all cell lines exhibited adequate receptor expression for FP59 intoxication (Table 1c).

Table 1.

PA-L1/LF, PA/LF, and PA/FP59 cytotoxicity to human melanoma cells. Twenty five melanoma cell lines were tested for PA-L1/LF sensitivity as described in the Methods section. Assays were performed in triplicate with IC50 variability between assays less than 30% and the IC50s were subsequently tabulated. (a) Twelve cell lines were sensitive to PA-L1/LF as well as PA/LF (IC50 < 200 pM with < 10% of control 3H thymidine incorporation at 10 nM PA-L1/1 nM LF) while 13 melanomas were resistant to PA-L1/LF. (b) The PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines G361, A375, A101D, SK-MEL-28, 451Lu, WM902B were sensitive to PA/LF (IC50 < 200 pM with < 10% of control 3H thymidine incorporation at 10 nM PA/1 nM) LF and thus exhibited MAPK dependency. (c) The PA-L1 resistant SK-MEL-2 demonstrated resistance to PA/FP59, which suggested low LeTx receptor expression. The PA/FP59 sensitive WM1361A, SK-MEL-173, A2058, WM1158, WM239A, and WM3211 were not sensitive to PA/LF, which indicated tolerance for LF-mediated MAPK inhibition.

| Cell Line | PA-L1/LF ([3H]thymidine, pmol/L) |

PA/LF IC50 ([3H]thymidine, pmol/L) |

PA/FP59 IC50 ([3H]thymidine, pmol/L) |

MAP Kinase Pathway Mutational Status |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a PA-L1/LF senstive melanoma cell lines | |||||

| SK-MEL-24 | 7 | 2 | 2 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| WM793B | 11 | 7 | 1 | V600E B-RAF | 29 |

| C32 | 11 | 8 | 1 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| WM115 | 19 | 8.7 | 0.65 | V600E B-RAF | 25 |

| WM46 | 55 | 12 | 7.8 | V600E B-RAF | |

| Malme-3M | 64 | 54 | 25 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| HT-144 | 104 | 25 | 2 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| WM983A | 109 | 16 | 5.1 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| WM-266–4 | 119 | 58 | 5 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| 1205Lu | 147 | 14 | 2 | V600E B-RAF | 29 |

| WM852 | 159 | 14 | 0.7 | Q61R NRAS | |

| WM51 | 177 | 54 | 15 | V600E B-RAF | |

| b PA-L1/LF resistant, PA/LF sensitive melanoma cell lines | |||||

| G361 | 225 | 44 | 9 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| A375 | 247 | 93 | 4 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| A101D | 335 | 30 | 3 | V600E B-RAF | |

| SK-MEL-28 | 359 | 15 | 2 | V600E B-RAF | 10 |

| 451Lu | 841 | 57 | 5.7 | V600E B-RAF | 30 |

| WM902B | 1010 | 33 | 10 | V600E B-RAF | |

| c PA/LF resistant melanoma cell lines | |||||

| SK-MEL-2 | 407 | 319 | 130 | Q61K NRAS | 10 |

| WM1361A | 419 | 248 | 4.7 | Q61R NRAS | 29 |

| SK-MEL-173 | 757 | 286 | 6.4 | Wild-type B-RAF | |

| A2058 | >10,000 | >10,000 | 1.9 | Heterozygous V600E B-RAF | |

| WM1158 | >10,000 | >10,000 | 0.5 | V600E B-RAF | |

| WM239A | >10,000 | >10,000 | 0.4 | Wild-type B-RAF | |

| WM3211 | >10,000 | >10,000 | 1 | Wild-type B-RAF/NRAS | |

PA/LF cytotoxicity analysis revealed that 18 cell lines were sensitive to LF-mediated MEK cleavage, including the 12 PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas (IC50 < 200 pmol/L with < 10% of control 3H thymidine incorporation at 10 nM PA/1 nM LF) (Table 1 a and b). These results are in agreement with previously published data from our laboratory and others in that the majority of the PA/LF sensitive cells are positive for the signature B-RAF V600E mutation (10–11). More importantly, 6 cell lines that were sensitive to PA/LF were resistant to PA-L1/LF (Table 1b). In addition, 6 cell lines were resistant to PA/LF as well as PA-L1/LF (Table 1c). Representative melanoma cell lines are shown from each group of cell lines in supplementary figure 1.

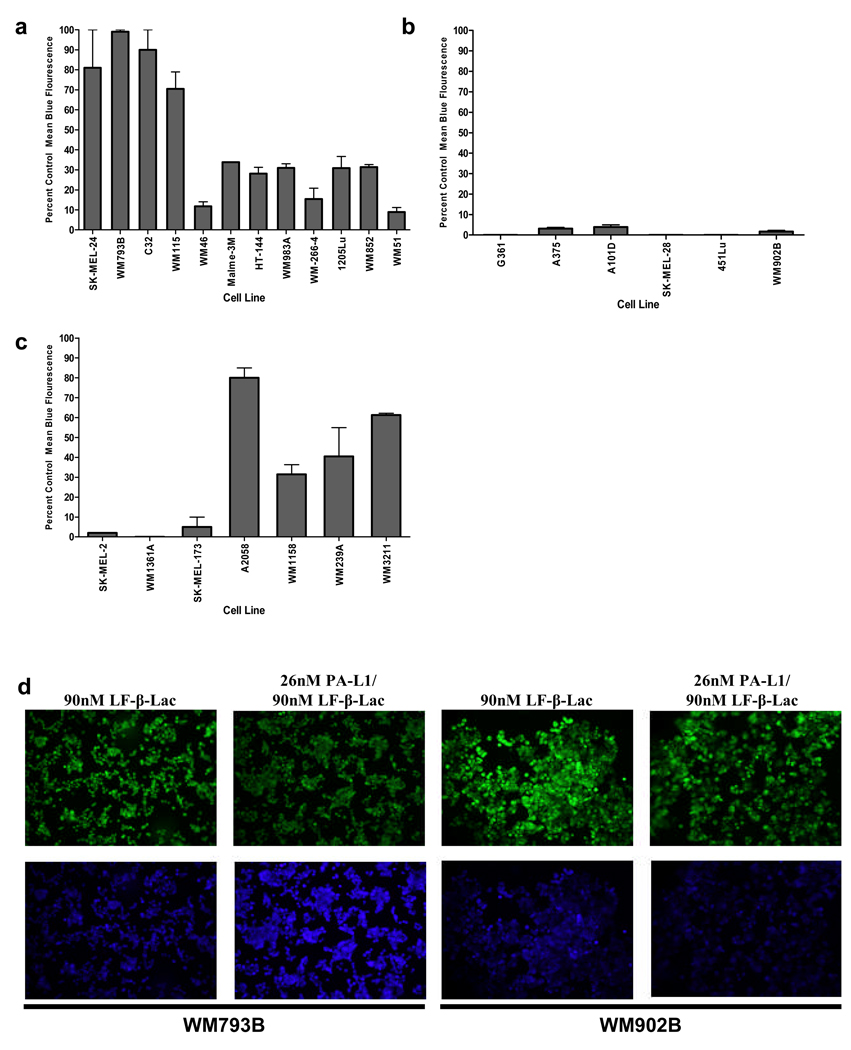

PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas show high PA-L1 activation

Since PA-L1 activation is required for its oligomerization and LF binding, decreased PA-L1 activation may lead to reduced LF internalization. Therefore, in order to determine whether PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines are deficient in their ability to activate PA-L1, we utilized a Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) disruption based assay (13). Cells were treated with PA-L1 and LF-β-Lac, a β-Lactamase enzyme genetically fused to the PA binding domain of LF, and subsequently loaded with the fluorescent β-Lactamase substrate CCF-2/AM (13). Melanomas that had activated PA-L1 and internalized LF-β-Lac fluoresced blue from LF-β-Lac-mediated substrate cleavage while cells that did not activate PA-L1 fluoresced green (13). PA-L1/LF-β-Lac flow cytometry analysis indicated that the 12 PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas all had elevated LF-β-Lac activity (Fig. 1a). Cell lines that were extremely sensitive to PA-L1/LF (IC50 < 20 pmol/L) all showed between 70 and 100 percent mean blue fluorescence, while cells that had an IC50 between 55 and 177 pmol/L demonstrated an intermediate percent mean blue fluorescence. The 6 PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines all exhibited negligible LF-β-Lac activity (Fig. 1b). Moreover, the 7 cell lines which were resistant to both PA/LF and PA-L1/LF, including the low receptor expressing SK-MEL-2, exhibited variable (low to high) levels of LF-β-Lac activity that were often comparable to the PA-L1/LF sensitive cell lines (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

PA-L1 activation by melanoma cells. Melanomas were first treated with either 90 nM LF-β-Lac or 26 nM PA-L1/90 nM LF-β-Lac and then loaded with the β-Lactamase enzyme substrate, the membrane-permeable fluorogenic dye CCF-2/AM. Intact CCF-2/AM emits fluorescence at 520 nm (green) due to intramolecular fluorescence resonance transfer between 7- hydroxycoumarin and flourescin, while LF-β-Lac-mediated CCF-2/AM hydrolysis will cause an emission at 447 nm (blue) from the liberated donor coumarin. Melanoma PA-L1 activation and LF-β-Lac internalization will result in blue light emission, while cells that did not activate PA-L1 will emit green fluorescence (a) PA-L1/LF-β-Lac flow cytometry indicated that PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas exhibited high LF-β-Lac activity. (b) All of the PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines demonstrated negligible LF-β-Lac activity. (c) The PA/LF resistant cell lines showed varying levels of LF-β-Lac activity, with some being comparable to the PA-L1/LF sensitive cell lines. (d) The PA-L1/LF sensitive cell line WM793B (PA-L1/LF IC50 11 pM) and the resistant WM902B (PA-L1/LF IC50 1010pM) were treated with either 90 nM LF-β-Lac alone or 26 nM PA-L1/ 90 nM LF-β-Lac, loaded with CCF-2/AM, and visualized as described in the methods section. WM793B demonstrated high LF-β-Lac activity while LF-β-Lac activity in WM902B was negligible.

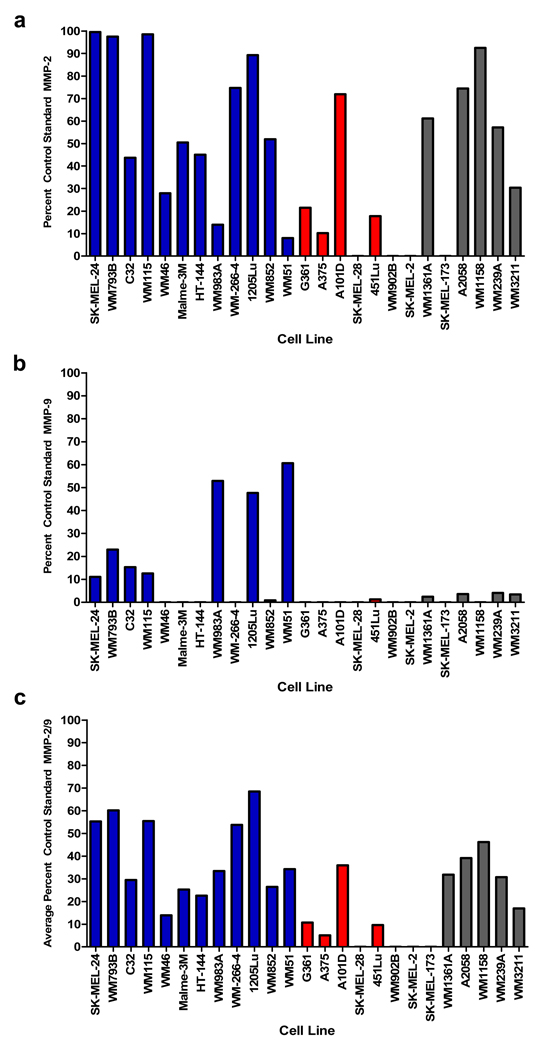

PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas exhibit elevated cell surface gelatinase activity

To test whether the melanomas that failed to activate PA-L1 expressed low levels of gelatinases, we utilized gelatin zymography to measure MMP-2 and −9 activity in both melanoma cell conditioned medium and lysates. Conditioned medium zymography analysis determined that neither MMP-2 nor MMP-9 activity correlated with PA-L1/LF sensitivity (Pearson r = 0.19, p = 0.44 for MMP-2, Pearson r = −0.24, p = 0.32 for MMP-9, respectively) (data not shown). Likewise, average conditioned medium gelatinase activity, which was obtained by averaging MMP-2 and MMP-9 percent control values, failed to significantly correlate with melanoma PA-L1/LF sensitivity (Pearson r = 0.021, p = 0.93). To further support this observation, the addition of 2 ng/well recombinant MMP-2 or MMP-9 to the culture medium did not enhance PA-L1/LF toxicity in the PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines. Furthermore, the addition of both gelatinases to yield an additional 4 ng/well of gelatinases in the culture medium did not produce any significant improvement in PA-L1/LF cytotoxicity in these cell lines (data not shown).

Gelatin zymography of cell lysate MMP-2 produced a significant correlation with PA-L1/LF sensitivity (Pearson r = −0.66, p = 0.003) (Fig. 2a), while MMP-9 activity did not (Pearson r = −0.16, p = 0.51) (Fig. 2b). Like MMP-2, PA-L1/LF sensitivity demonstrated a significant correlation with average cell lysate gelatinase activity (Pearson r = −0.61, p = 0.006) (Fig. 2c). Representative melanoma cell lines are shown from each group of cell lines in supplementary figure 2. We also analyzed levels of MT1-MMP (MMP-14) via western blot since it has previously been shown that MT1-MMP is capable of activating PA-L1 and thus plays a role in PA-L1/LF intoxication (14). However, we found that melanoma cell line MT1-MMP expression did not correlate with PA-L1/LF sensitivity (Pearson r = −0.019) (data not shown). MMP-1 has also been shown to be significant in melanoma progression, though expression levels of these MMPs failed to correlate with PA-L1/LF sensitivity (Pearson r = .1528, p = .5451) (data not shown) (3).

Figure 2.

Gelatinase activity in melanoma cell lines. Gelatin zymography was performed using recombinant pro forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (68 kD and 92 kD, respectively) and active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (62 kD and 83 kD, respectively) as standard controls. Melanoma lysate gelatinase activity was identified as the pro form of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Zymography determined that PA-L1 sensitive cells (blue bars) over expressed either (a) MMP-2 (b) MMP-9 when compared to the PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1/LF resistant cell lines (red bars). Cell lines that were resistant to PA/LF (gray bars) exhibited MMP expression that was comparable to PAL1/ LF sensitive cell lines. (c) Total gelatinase activity was determined by averaging the percent control standard MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity of each cell line. Data presented is a representative of two separate experiments.

B-RAF mutational status in PA/LF resistant melanomas

In order to explain the cause of the 6 PA/LF resistant melanoma cell lines, we first determined the B-RAF status of the PA/LF resistant cell lines by PCR-sequencing of exons 11 and 15 of the B-RAF gene, producing the data tabulated in the right hand column of Table 1. We found that SK-MEL-173, WM239A, and WM3211 did not carry any mutations in either exon 11 or 15. We also found that WM1361A carried the Q61R NRAS mutation. Therefore, these cell lines did not carry the sensitizing V600E B-RAF mutation and thus were not sensitive to LF-mediated MEK cleavage. Furthermore, A2058 was heterozygous for the V600E B-RAF mutation. WM1158, although resistant to PA/LF, was positive for the V600E B-RAF mutation.

Discussion

In this study, 48% of the human melanoma cell lines tested were sensitive to PA-L1/LF. Although our studies indicated that modification of the furin-cleavage site did slightly reduce PA potency, we have successfully demonstrated the enhanced selectivity of PA-L1/LF. We were able to show that all PA-L1/LF sensitive melanoma cell lines exhibited high PA-L1 activation, as determined by a Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) disruption based assay (13). Subsequently, we demonstrated that these cell lines exhibited high cell lysate MMP-2 and/or MMP-9 activity. Furthermore we showed that 11/12 PA-L1/LF sensitive melanoma cell lines carried the B-RAF V600E mutation. In a study including non-melanoma human tumors, cells carrying this specific mutation were similarly highly susceptible to LF-mediated MAPK inhibition (11). These results show that the B-RAF V600E is closely associated with sensitivity to LF-mediated cell death. Furthermore, small molecular weight inhibitors of MEK1 show similar B-RAF V600E dependent melanoma cell cytotoxicity (17). Pathway dependency of tumors has been similarly described with malignancies bearing the Bcr-Abl oncogene and epidermal growth factor receptor mutations (18–19). Thus, the dual specific recombinant toxin PA-L1/LF requires both the over expression of MMP-2/-9 as well as MAPK dependency for anti-melanoma efficacy in vitro.

Of the 13 PA-L1/LF resistant melanomas, 6 were dependent on the MAPK pathway for survival as indicated by sensitivity to PA/LF as well as the presence of the V600E B-RAF mutation. These findings suggested that these cells were sensitive to LF-mediated MAPK inhibition, but failed to activate PA-L1 and thus did not internalize LF. This PA-L1 activation deficiency was confirmed by the PA-L1 activation assay, which demonstrated that these cells fail to cleave PA-L1. In addition, these melanomas expressed low and sometimes undetectable quantities of cell surface associated MMP-2/-9, as determined by lysate zymography.

Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that PA-L1/LF sensitivity is mediated by PA-L1 activation in V600E B-RAF melanomas. Our results indicate that membrane associated MMP-2/-9, but not free gelatinases, MT1-MMP, or membrane associated MMP-1 and MMP-7 appear to be the primary enzymes involved in PA-L1 cleavage. Proteolytically active MMPs can localize to the cell surface via high affinity binding sites in order to better direct ECM degradation (20). MMP-2, aside from being activated on the cell surface via TIMP-2/MT1-MMP complexes, can bind to αvβ3 integrins (20–21). Likewise, CD44 has been shown to serve as a cell surface docking molecule for the localization of MMP-9 (22).

Although lysate MMP-9 activity alone failed to correlate with sensitivity, expression was mostly seen in PA-L1/LF sensitive and PA/LF resistant cells. In addition, a select few of the PA-L1/LF sensitive cells that expressed low levels of MMP-2 over expressed MMP-9, such as the case with WM983A and WM51. Since initial in vitro PA-L1 cleavage studies demonstrated that MMP-9-mediated PA-L1 cleavage efficiency was almost indistinguishable from MMP-2, we could not exclude the significance of this gelatinase in PA-L1 activation (14). Therefore, we reasoned that the activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 averaged, which did significantly correlate with PA-L1/LF sensitivity, would serve as a more dependable figure for the comparison of gelatinase activity between cell lines. Therefore, V600E melanoma cell lines that have elevated levels of cell surface associated MMP-2/-9 will activate adequate PA-L1 and consequently internalize sufficient quantities of LF for complete MAPK inhibition.

We also found that the remaining 7 melanoma cell lines were resistant to both PA-L1/LF and PA/LF. With the exception of SK-MEL-2, these cells were extremely sensitive to PA/FP59, which indicated adequate LeTx receptor expression for FP59 intoxication. In addition, these cell lines exhibited PA-L1 activation and cell surface associated MMP-2/-9 activity that was comparable to that of PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas. Taken together, these results indicated that the resistance exhibited by these 6 cell lines was independent of PA-L1 activation and LF internalization. In an attempt to determine the cause of resistance in this group of cell lines, we determined whether the sensitizing V600E B-RAF mutation was present. Our results indicated that 3 of the PA/LF resistant melanomas did not carry any mutations in exon 11 or 15 in the B-RAF gene and 1 melanoma carried a mutation in the upstream NRAS. In addition, 1 cell line harbored a heterozygous mutation in the B-RAF gene. Therefore, these cells do not express, or only partially express, the constitutively active B-RAF protein. As a result, these cell lines are not sensitive to MAPK inhibition.

However, we found that WM1158 was positive for the V600E B-RAF mutation. We determined whether the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/Akt/ GSK-3β pathway had a role in the observed PA/LF resistance. It has recently been shown that the activation of Akt causes the inhibition of GSK-3β-mediated cyclin D1 degradation and consequential G0-G1 cell cycle arrest (23). This activation is critical for recovery from LeTx-mediated cell cycle arrest and resistance to subsequent toxin challenge in human macrophages (23). Furthermore, Akt over activation can result from the loss of the lipid phosphatase PTEN in melanomas (24). Therefore, we reasoned that the activation of Akt, possibly through the deletion of PTEN, could potentially provide WM1158 cells an LF-mediated MEK cleavage bypass mechanism (24–25). We found that while WM1158 PTEN expression was not detectable via western blot, the pretreatment of WM1158 cells with either PI3-K or Akt inhibitors failed to enhance PA/LF cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the inhibition of GSK3β did not increase the resistance in PA/LF sensitive 451Lu cells. Thus, resistance mechanisms to PA/LF in B-RAF V600E/MMP-2 or 9 over-expressing melanoma cells are currently not defined. As noted in previous work from our laboratory, the presence of the V600E B-RAF mutation does not always translate to sensitivity to LF-mediated MEK cleavage (10). However, only 1 out of 19 V600E B-RAF melanomas was resistant to LF-mediated MAPK inhibition, which makes this type of resistance rare.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that both adequate cell surface associated MMP-2/-9 as well as the MAPK activating V600E B-RAF mutation are needed in order for PA-L1/LF to be active. This dual specificity has already demonstrated a 3-fold higher LD10 in addition to a 20fold greater circulating half-life when compared to LeTx (11). As a result; in vivo anti-tumor efficacy was dramatically improved by an elevated AUC from a higher dose and longer half-life (11). Moreover, we have shown that cell surface associated MMP-2/-9 activity significantly correlates with PA-L1/LF sensitivity and therefore is the primary mediator in sensitivity among V600E B-RAF melanomas in vitro. The contribution of this mechanism to the overall anti-tumor mechanism of PA-L1/LF in vivo remains unclear, since PA-L1/LF has been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction during angiogenesis (11, 26). However, this correlation of in vitro cytotoxicity to MMP-2/9 expression permits the application of simple biomarker assays on tumor samples for prediction of patient response to PA-L1/LF. Therefore, we propose tumor tissue PCR and sequencing for B-RAF V600E status and immunohistochemistry for expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (27–29). Taken together, these findings will ultimately aid in the selection of metastatic melanoma patients for systemic MMP-activated LeTx therapy.

Supplementary Material

Melanoma dose response curves from each group are presented. (a-b) WM793B and WM-115 are sensitive to all three toxins. (c) WM902B is sensitive to PA/LF and PA/FP59 but resistant to PA-L1/LF, suggesting that this cell line fails to activate PA-L1 but expresses both adequate toxin receptors and the sensitizing V600E B-RAF mutation. (d) WM3211 does not harbor the V600E B-RAF mutation, and therefore is not sensitive to PA/LF or PA-L1/LF.

Gelatin zymograms of representative melanomas are shown from each group of cell lines (a) PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas (b) PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1 resistant melanomas and (c) PA/LF resistant, PA-L1/LF resistant melanomas along with controls. pMMP-2/-9 designates proMMP-2/-9, aMMP-2/-9 designates active forms of MMP-2/-9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Jen-Sing Liu and Shu-Ru Kuo for helpful discussions and Alan Houghton for SK-MEL-173. We also thank Dr. Honying Zheng, Dr. Juhee Song and Courtney Ireland for technical assistance as well as Dr. Yunpeng Su and Dr. Cindy Meininger for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Scott & White Cancer Research Institute

Abbreviations

- PA

protective antigen

- LF

lethal factor

- LeTx

anthrax lethal toxin

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

Footnotes

The authors do not claim a conflict of interest

References

- 1.Queirolo P, Acquati M. Targeted therapies in melanoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann UB, Houben R, Bröcker EB, Becker JC. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in melanoma cell invasion. Biochimie. 2005;87:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denkert C, Siegert A, Leclere A, Turzynski A, Hauptmann S. An inhibitor of stressactivated MAP-kinases reduces invasion and MMP-2 expression of malignant melanoma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19:79–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1013857325012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duesbery NS, Resau J, Webb CP, et al. Suppression of ras-mediated transformation and inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis by anthrax lethal factor, a proteolytic inhibitor of multiple MEK pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4089–4094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061031898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young JA, Collier RJ. Anthrax toxin: receptor binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puhar A, Montecucco C. Where and how do anthrax toxins exit endosomes to intoxicate host cells? Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra AP, Boone SA, Liang X, Duesbery NS. Anthrax lethal factor proteolysis and inactivation of MAPK kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9402–9406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koo HM, VanBrocklin M, McWilliams MJ, Leppla SH, Duesbery NS, Vande Woude GF. Apoptosis and melanogenesis in human melanoma cells induced by anthrax lethal factor inactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:3052–3057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707699. USA 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abi-Habib RJ, Urieto JO, Liu S, Leppla SH, Duesbery NS, Frankel AE. BRAF status and mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2 activity indicate sensitivity of melanoma cells to anthrax lethal toxin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1303–1310. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S, Wang H, Currie BM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-activated anthrax lethal toxin demonstrates high potency in targeting tumor vasculature. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:529–540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707419200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KH, Liu S, Bankston LA, Liddington RC, Leppla SH. Selection of anthrax toxin protective antigen variants that discriminate between the cellular receptors TEM8 and CMG2 and achieve targeting of tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9834–9845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611142200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobson JP, Liu S, Rono B, Leppla SH, Bugge TH. Imaging specific cell-surface proteolytic activity in single living cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:259–261. doi: 10.1038/nmeth862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Netzel-Arnett S, Birkedal-Hansen H, Leppla SH. Tumor cell-selective cytotoxicity of matrix metalloproteinase-activated anthrax toxin. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6061–6067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora N, Klimpel K, Singh Y, Leppla S. Fusions of anthrax toxin lethal factor to the ADP-ribosylation domain of Pseudomonas exotoxin A are potent cytotoxins which are translocated to the cytosol of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15542–15548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong L, Suh DY, Frankel AE. Toxin conjugate therapy of cancer. J Seminoncol. 2005;8:591–595. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A, Tran MA, Liang S, et al. Targeting mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase in the mutant (V600E) B-Raf signaling cascade effectively inhibits melanoma lung metastases. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8200–8209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sequist LV, Lynch TJ. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer: an evolving story. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:429–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.090506.202405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White D, Saunders V, Grigg A, et al. Measurement of in vivo BCR-ABL kinase inhibition to monitor imatinib-induced target blockade and predict response in chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4445–4451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmann U, Westphal J, Van Muijen G, Ruiter D. Matrix metalloproteinases in human melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:337–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornebeck W, Emonard H, Monboisse J, Bellon G. Matrix-directed regulation of pericellular proteolysis and tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase 9 to the cell surface provides a mechanism for CD44-mediated tumor invasion. Genes Dev. 1999;13:35–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ha SD, Ng D, Pelech S, Kim SO. Critical role of PI3-K/Akt/GSK-3beta signaling pathway in recovery from anthrax lethal toxin-induced cell cycle arrest and MEK cleavage in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36230–36239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haluska FG, Tsao H, Wu H, Haluska FS, Lazar A, Goel V. Genetic alterations in signaling pathways in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2518. 2301s-2307s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsao H, Goel V, Wu H, Yang G, Haluska FG. Genetic Interaction between NRAS and BRAF Mutations and PTEN/MMAC1 inactivation in melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:337–341. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alfano RW, Leppla SH, Bugge TH, Duesbery NS, Frankel AE. Potent inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by the matrix metalloproteinase-activated anthrax lethal toxin: Implications for broad anti-tumor efficacy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7 doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5627. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorden A, Osman I, Gai W, et al. Analysis of BRAF and N-RAS mutations in metastatic melanoma tissues. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3955–3957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simonetti O, Lucarini G, Brancorsini D, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase 2, and matrix metalloproteinase 9 in cutaneous melanocytic lesions. Cancer. 2002;95:1963–1970. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spittle C, Ward MR, Nathanson KL, et al. Application of a BRAF pyrosequencing assay for mutation detection and copy number analysis in malignant melanoma. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:464–471. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smalley K, Contractor R, Haass N, et al. Ki67 expression levels are a better marker of reduced melanoma growth following MEK inhibitor treatment than phospho-ERK levels. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:445–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Melanoma dose response curves from each group are presented. (a-b) WM793B and WM-115 are sensitive to all three toxins. (c) WM902B is sensitive to PA/LF and PA/FP59 but resistant to PA-L1/LF, suggesting that this cell line fails to activate PA-L1 but expresses both adequate toxin receptors and the sensitizing V600E B-RAF mutation. (d) WM3211 does not harbor the V600E B-RAF mutation, and therefore is not sensitive to PA/LF or PA-L1/LF.

Gelatin zymograms of representative melanomas are shown from each group of cell lines (a) PA-L1/LF sensitive melanomas (b) PA/LF sensitive, PA-L1 resistant melanomas and (c) PA/LF resistant, PA-L1/LF resistant melanomas along with controls. pMMP-2/-9 designates proMMP-2/-9, aMMP-2/-9 designates active forms of MMP-2/-9.