Abstract

We summarized results in 38 consecutive patients (median age = 56 years) with hematologic malignancies (n=33), aplastic anemia (n=2) or renal cell carcinoma (n=1), who underwent salvage hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for allograft rejection. In 14 patients the original donors were used for salvage HCT, and in 24 cases different donors were used. Conditioning for salvage HCT consisted of fludarabine and either 3 or 4 Gy total body irradiation (TBI). Sustained engraftment was achieved in 33 patients (87%). Grafts were rejected in 5 patients (13%), 4 of whom had myelofibrosis. With a median follow-up of 2 (range, 0.3 to 7.8) years, the 2 and 4 year estimated survivals were 49% and 42%, respectively. The 2-year relapse rate and non-relapse mortality were 36% and 24%, respectively. The 2-year cumulative incidences of grades 2–4 acute and moderate-severe chronic graft-versus-host disease were 42% and 41%, respectively. In this cohort, TBI dose, grafts from original vs. different donors, related vs. unrelated donors, and HCT comorbidity scores did not impact outcomes. We concluded that graft rejection after allogeneic HCT could be overcome by salvage transplantation using conditioning with fludarabine and low dose TBI.

INTRODUCTION

Graft rejection is an infrequent but life-threatening complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), occurring historically at a frequency of 6% or less after bone marrow transplantation with myeloablative conditioning [1,2]. However, with expanding indications for HCT and widespread use of alternative donors and non-myeloablative conditioning regimens, graft rejection rates of 12–15% have been reported [3–5]. Factors influencing graft rejection include underlying diseases, previous chemotherapy, graft sources and composition, degrees of HLA disparity, intensity of conditioning regimens and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. In general, graft rejection has been associated with poor outcome [6].

Management of graft rejection is challenging, due to cytopenias, infections and organ toxicity resulting from the preparative regimens. Salvage allogeneic HCT represented a possible therapeutic strategy, although the available literature has been limited to small, single institution series [7–12]. The early experience with second allogeneic HCTs using myeloablative conditioning at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center was summarized by Radich et al [13]. Seventy seven patients with hematologic malignancies underwent second allogeneic HCTs for relapse after allogeneic marrow transplantation following high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation (TBI). In this series, patients older than 10 years had a 60% risk of non-relapse mortality (NRM) at 1 year. Second allogeneic HCTs were more successful in patients with severe aplastic anemia, who received cyclophosphamide-based conditioning regimens for both their first and second transplants (10-year survival was 83% for patients undergoing 2nd HCT between 1982 and 1996) [14].

In general, second myeloablative HCT, particularly in adults, has been associated with serious toxicities. For this reason, reduced intensity regimens were designed to escalate host immunosuppression necessary for successful engraftment. Baron et al. [15] described allogeneic HCTs after nonmyeloablative conditioning (2 Gy of TBI with or without fludarabine) in patients who had experienced relapse after autologous (n=137) or allogeneic (n=10) myeloablative HCT. The overall 3-year NRM rate was approximately 30%.

Here we summarize the multicenter experience with salvage allogeneic HCT in 38 patients with primary or secondary allograft rejection, using fludarabine and TBI of 3 or 4 Gy as preparative regimen.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This retrospective analysis included 38 consecutive patients with primary (n=18) or secondary (n=20) allograft rejection who underwent salvage allogeneic HCT after conditioning with fludarabine and low dose TBI (3 or 4 Gy) between March 2000 and November 2007 at 3 participating centers: the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC; n=16), Stanford University (SU; n=11) and the University of Leipzig (UL; n=11). Primary graft rejection was defined as failure to detect more than 5% donor CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood at any time point after HCT. Engraftment with mixed chimerism was defined as attainment of between 5% to 95% donor peripheral blood CD3+ T-cells at day 28. Following initial engraftment, a decline in donor peripheral blood CD3+ T-cells to ≤ 5% was considered secondary graft rejection. Patients with evidence of relapse/progression of their underlying disease following their first allograft were not included in this study.

Results were analyzed as of July 28, 2008. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Thirty-six patients had failed one, one patient had failed two and one patient failed three preceding allogeneic transplants. Three patients had autologous HCTs before their first allogeneic HCTs. There were 21 males and 17 females. Median age of patients was 56 (range: 8 – 68) years; with one exception patients were older than 21 years. Diagnoses included hematologic malignancies (acute myeloid leukemia, n=12; myeloproliferative disorder/chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis, n=6; chronic myeloid leukemia, n=4; non-Hodgkin lymphoma, n=4; myelodysplastic syndrome(MDS)/myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) overlap syndrome, n=3; acute lymphoid leukemia n=2; MDS with or without paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, n=2; multiple myeloma, n=1; plasma cell leukemia, n=1); aplastic anemia, (n=2); and renal cell cancer, (n=1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients, n | 38 |

| Median age (range) in years | 56 (8–68) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 21 (55) |

| Female | 17 (45) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| AA/SAA | 2 (5) |

| ALL | 2 (5) |

| AML | 12 (32) |

| CML | 4 (11) |

| MPD/CIMF | 6 (16) |

| MPD/MDS | 3 (8) |

| MDS +/− PNH | 2 (5) |

| NHL | 4 (11) |

| Plasma cell leukemia | 1 (3) |

| MM | 1 (3) |

| Renal Cell Ca | 1 (3) |

| Patient CMV status, n (%) | |

| negative | 14 (37) |

| positive | 24 (63) |

Abreviations: AA: aplastic anemia, ALL: acute lymphoid leukemia, AML: acute myeloid leukemia, CIMF: chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis, CML: chronic myeloid leukemia, CMV: cytomegalovirus, MM: multiple myeloma, MPD: myeloproliferative disorder, NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma, PNH: paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, SAA: severe aplastic anemia.

A retrospective chart review and waiver of informed consent for chart review were approved by the institutional review boards of all 3 participating Centers.

First/Preceding HCTs

Characteristics of the first/preceding allogeneic HCT are summarized in Table 2. With the exception of the unrelated umbilical cord blood units (UCB), patients and donors were tested for HLA-A, -B, -C and -DQB1 by at least intermediate-resolution DNA typing and for HLA-DRB1 by high-resolution techniques. Cord blood units were tested for HLA-A and B antigens and DRB1 alleles. Grafts were from HLA-identical siblings (n=11), HLA-matched unrelated donors (n=17) and HLA-mismatched unrelated donors (n=10, including 2 patients who received double unrelated UCB grafts). Additional details of HLA-disparity, including the number of mismatched HLA loci are summarized in Table 2. The stem cell sources were granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC; n=32), bone marrow (n=4) or UCB (n=2). The median CD34+ cell dose for PBSC grafts was 7.67 × 106 CD 34+ cells/kg recipient weight. The median total nucleated cell count of bone marrow and double UCB grafts were 1.55 × 108/ kg and 3.79 × 107/kg recipient weight, respectively. A total of 28 patients received non-myeloablative conditioning with 2 Gy TBI on day 0 with (n=27) or without (n=1) fludarabine 30 mg/m2/day on days −4 through −2. Seven patients received myeloablative conditioning with busulfan (n=6) or 12 Gy fractionated TBI (n=1) combined with cyclophosphamide. Three patients received anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) combined with either cyclophosphamide (n=1), cyclophosphamide/4 Gy TBI (n=1), or cyclophosphamide/fludarabine/2 Gy TBI (n=1). Postgrafting immunosuppression for the 29 patients receiving non-myeloablative or ATG/low dose TBI-based conditioning consisted of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and cyclosporine (CSP), as described [16].

Table 2.

Characteristics of 1st/preceding HCT.

|

Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Donor, n (%) | |

| HLA-identical sibling | 11 (29) |

| -matched unrelated | 17 (45) |

| -mismatched unrelated | 10 (26) |

| B-allele | 3 (8) |

| C-antigen | 3 (8) |

| C-antigen and C-allele | 1 (3) |

| DRB1-allele | 1 (3) |

| B-antigen/B-antigen (double UCB graft) | 1 (3) |

| A- and B-antigen/A- and B-antigen (double UCB graft) | 1 (3) |

| ABO mismatch n (%) | |

| Major | 16 (42) |

| Minor | 6 (16) |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | |

| PBSC | 32 (84) |

| Marrow | 4 (11) |

| UCB | 2 (5) |

| Cell Dose | |

| PBSC - Median CD34+ cell dose (range) × 106/kg | 7.67 (3.3 – 62) |

| Double UCB - Median TNC dose (range) × 107/kg | 3.79 (2.58 – 5.0) |

| Marrow - Median TNC dose (range) × 108/kg | 1.55 (1.18 – 2.6) |

| Conditioning, n (%) | |

| FLU, TBI (2 Gy) | 27 (71) |

| TBI (2 Gy) | 1 (3) |

| BU, CY | 6 (16) |

| CY - TBI (12 Gy) | 1 (3) |

| - FLU, ATG,TBI (2 Gy) | 1 (3) |

| - ATG, TBI (4 Gy) | 1 (3) |

| -ATG | 1 (3) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis, n (%) | |

| MMF - CSP | 29 (76) |

| - Tacrolimus | 1 (3) |

| Methotrexate - CSP | 4 (11) |

| - Tacrolimus | 4 (11) |

Abbreviations: ATG: anti-thymocyte globulin, BU: busulfan, CSP: cyclosporine A, CY: cyclophosphamide, FLU: fludarabine, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil PBSC: peripheral blood stem cell, TBI: total body irradiation, TNC: total nucleated cell, UCB: umbilical cord blood.

One patient given non-myeloablative conditioning received tacrolimus and MMF. Patients undergoing myeloablative conditioning received methotrexate and either CSP (n=4) or tacrolimus (n=4), as described [17,18]. Following HCT, patients were monitored with daily blood counts for evidence of engraftment. Donor chimerism was evaluated in peripheral blood CD3+ T-cells and granulocytes (CD33+ cells at FHCRC and CD15+ cells at SU and UL) separated by flow cytometry. Donor-host chimerism levels were evaluated on day 28, and, on most patients on days 84, 180 and 360 after HCT using polymerase chain reaction-based amplification of variable-number tandem repeat or short-tandem repeat sequences unique to donors and hosts, or by fluorescent in situ hybridization for X and Y chromosomes in some cases when patients and donors were sex mismatched.

Primary graft rejection was defined as inability to detect more than 5% donor CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood at any time point after HCT. Following initial engraftment, a reduction in donor peripheral blood CD3+ T-cells to ≤ 5% was considered secondary graft rejection, as detailed above. Based on these definitions 18 of 38 patients experienced primary graft rejection; the remaining 20 had secondary graft rejection.

Second/Salvage HCTs

Characteristics of the 2nd/salvage allogeneic HCT are summarized in Table 3. HLA typing, patient monitoring and chimerism testing were carried out as described above. None of the patients included in this analysis had evidence of relapse/progression of their underlying disease at the time of salvage allogeneic HCT. Pretransplantation comorbidities were determined retrospectively using an HCT-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) [19]. Salvage HCTs were performed at a median of 91 (range: 29 – 1004) days after the preceding HCT. If patients had HLA-identical sibling donors for their preceding HCT, the same donors were used for salvage HCT, depending on their availability. When patients had HLA-matched unrelated donors for their previous HCT, different donor were utilized for salvage HCT, except in 3 patients. In summary, donors for the second HCT were the same as for the first in 14 cases; 11 were HLA-identical siblings and 3 HLA-matched unrelated donors. In the remaining 24 cases different donors were used; 11 were HLA-matched unrelated, 11 HLA-mismatched unrelated, one HLA-haploidentical related and one double UCB graft (Table 4). Additional details of HLA-disparity, including the number of mismatched HLA loci are shown in Table 3. The stem cell sources were PBSC (n=36), bone marrow (HLA-haploidentical donor, n=1) or UCB (n=1). The median CD34+ cell count for PBSC grafts was 7.6 × 106 CD 34+ cells/kg recipient weight, the TNC counts were 6.22 × 108/kg recipient weight and 4.0 × 107/kg recipient weight for the marrow and double UCB grafts, respectively. The conditioning regimens consisted of fludarabine 30mg/m2/day on days −4 to −2, followed by 3 Gy TBI (n=24) or 4 Gy TBI (n=12) on day 0. The determination of the TBI dose (3 vs. 4 Gy) was center-dependent. Except for 2 patients with HLA-identical sibling donors, all patients treated at FHCRC received 4 Gy TBI. All patients treated at SU and at the UL received 3 Gy TBI. One HLA-haploidentical recipient received fludarabine, 30 mg/m2/day on days −6 to −2, cyclophosphamide, 25 mg/kg on days −6 and −5, and 4 Gy TBI on day −1. Another patient given a double UCB graft was conditioned with fludarabine, 40 mg/m2/day on days −6 to −2, cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/kg on day −6, and 4 Gy TBI on day −1. Postgrafting immunosuppression for 37 patients consisted of CSP and MMF, as described [16] and tacrolimus and MMF for one patient. Acute and chronic GVHD were graded as described [20,21]. Toxicities occurring within the first 100 days were scored using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0.

Table 3.

Characteristics of salvage HCT.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Median days (range) from prior HCT | 91 (29 – 1004) |

| Donor, n (%) | |

| Same as in prior HCT | 14 (37) |

| Different from prior HCT | 24 (63) |

| HLA-identical sibling | 11 (29) |

| -haploidentical related | 1 (3) |

| -matched unrelated | 14 (37) |

| -mismatched unrelated | 12 (32) |

| antigen (A: n=1; C: n=4) | 5 (13) |

| allele (A: n=1; B: n=1; C: n=1) | 3 (8) |

| DRB1-allele | 1 (1) |

| DRB1-allele, DQB1-allele | 1 (3) |

| A-antigen, C-antigen, C-allele | 1 (3) |

| A- and DRB1-antigen/A- and DRB1-antigen (double UCB graft) | 1 (3) |

| ABO mismatch, n (% | |

| Major | 9 (26) |

| Minor | 11 (28) |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | |

| PBSC | 36 (95) |

| Marrow | 1 (3) |

| UCB | 1 (3) |

| Cell Dose | |

| PBSC - Median CD34+ cell dose (range) × 106/kg | 7.6 (1.5 – 19.39) |

| Marrow - TNC dose × 108/kg | 6.22 |

| Double UCB - TNC dose × 107/kg | 4.0 |

| Conditioning, n (%) | |

| FLU - 3 Gy TBI | 24 (63) |

| - 4 Gy TBI | 12 (32) |

| - CY, 4 Gy TBI | 2 (5) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis, n (%) | |

| MMF - CSP | 37 (97) |

| - Tacrolimus | 1 (3) |

| HCT-CI at time of salvage HCT, n (%) | |

| 0–1 | 6 (16) |

| 2–3 | 12 (32) |

| 4–5 | 14 (37) |

| ≥6 | 6 (16) |

Abbreviations: CSP: cyclosporine A, CY: cyclophosphamide, FLU: fludarabine, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, PBSC: peripheral blood stem cell, TBI: total body irradiation, TNC: total nucleated cell, UCB: umbilical cord blood.

Table 4.

Donors in 1st and 2nd HCTs.

| 2nd HCT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different Donor | ||||||

| 1st HCT | Same Donor |

HLA- MURD |

HLA- MMURD |

Double UCB |

HLA- haploidentical |

|

| HLA-identical sibling | 11 | 11 | – | – | – | – |

| HLA-MURD | 17 | 3 | 10 | 4 | – | – |

| HLA-MMURD | 8 | – | 1 | 7 | – | – |

| Double UCB | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations: HLA-MMURD: HLA-mismatched unrelated donor; HLA-MURD: HLA-matched unrelated donor; UCB: umbilical cord blood.

Causes of death

In patients who relapsed or progressed, relapse/progression was listed as primary cause of death regardless of other associated events. In patients with GVHD requiring immunosuppressive therapy who subsequently died from infections, GVHD/infection were listed as cause of death. Infection was listed as cause of death when it occurred in the absence of relapse/progression or GVHD. All deaths occurring in the absence of relapse/progression were considered non-relapse mortality (NRM).

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were reported using standard measures as appropriate for categorical and continuous data. The primary end point of this retrospective analysis was engraftment. Secondary end points included: overall survival, NRM, relapse/progression, acute and chronic GVHD.

Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cumulative incidence estimates were used for engraftment, relapse/progression, acute and chronic GVHD and NRM, treating death prior to the event of interest as a competing risk for engraftment, relapse and acute GVHD, and relapse as competing risk event for NRM [22]. Associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Greenwood’s formula for Kaplan-Meier estimates and the method described by Marubini and Valsecchi for cumulative incidence [23]. Comparisons between hazards of time to event outcomes were compared using the logrank test. All reported p-values were two-sided and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Engraftment

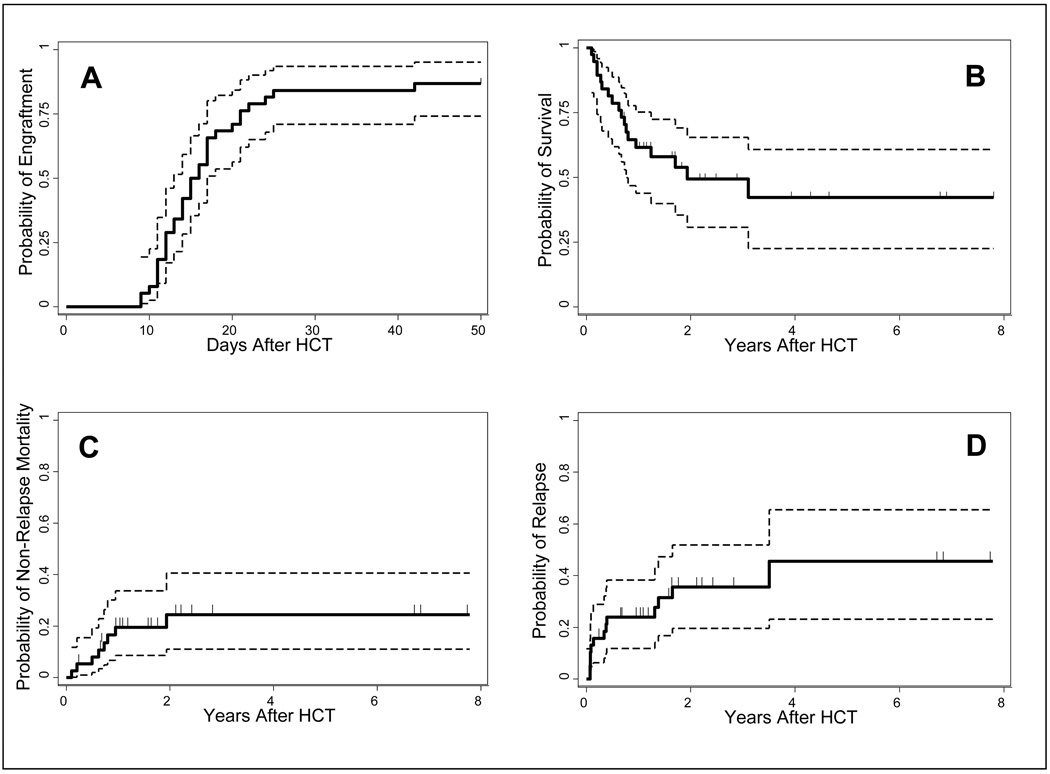

All patients experienced transient neutropenias. Thirty-three of 38 patients (87%) had sustained engraftment, with a median time to neutrophil engraftment of 15 (range 9 – 42) days (Figure 1A). Chimerism data were available on 32 of 33 engrafted patients. On day +28 after HCT, the median (range) peripheral blood CD3+ and CD33+/CD15+ cell chimerism levels were 98 (11–100)% and 100 (89–100)%, respectively.

Figure 1. Outcomes of Salvage HCT.

Neutrophil engraftment (A). Thirty-three of 38 patients had sustained engraftment (probability of engraftment: 0.87; 95 % CI: 0.74, 0.95). The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 15 (range 9 – 42) days. Survival (B) The 2 and 4-year estimated probabilities of survival were 0.49 (95% CI: 0.31, 0.66) and 0.42 (95% CI: 0.23, 0.61), respectively. Non-relapse mortality (C) The 2 year estimated probability of non-relapse mortality was 0.24 (95% CI: 0.11, 0.41). Relapse/Progression (D) The estimated probability of relapse/progression at 2 years was 0.36 ( 95% CI: 0.20, 0.52). The dashed lines represent 95% CI.

Five patients, 4 with myelofibrosis and 1 with acute lymphocytic leukemia rejected their grafts. Two of the 5 rejecting patients had HLA-identical sibling donors, 2 had HLA-matched unrelated donors and 1 had an HLA-A allele-mismatched unrelated donor. Three of the 5 had the same donors as in their previous HCT (2 HLA-identical siblings and 1 HLA-matched unrelated donor) while 2 patients had different donors (1 HLA-matched-and 1 HLA-A allele-mismatched unrelated donor). Four of the 5 patients received 3 Gy and one 4 Gy TBI as part of their conditioning.

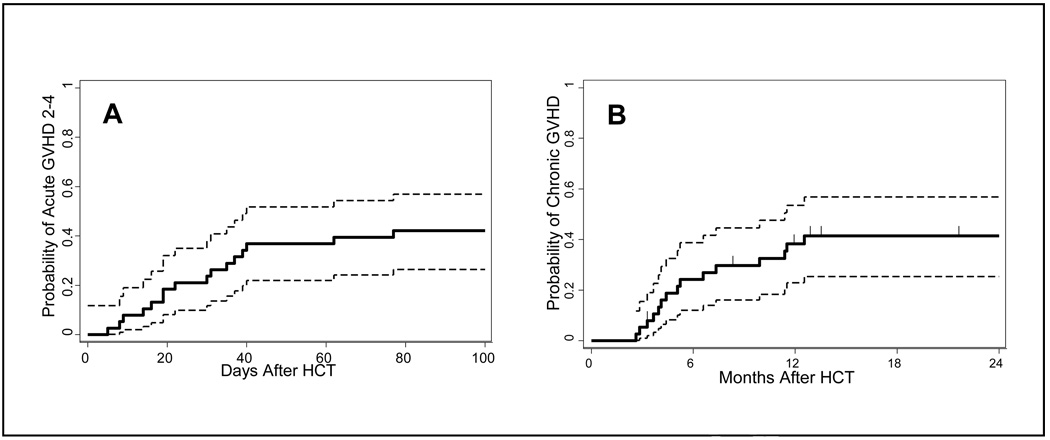

GVHD

All patients were assessed for acute GVHD. The cumulative incidences of acute GVHD, grades II-IV, III and IV, were 42%, 5% and 5%, respectively (Figure 2A). Of the 16 patients who developed grades II-IV acute GVHD, nine had HLA-mismatched unrelated donors, four had HLA-matched unrelated donors, two had HLA-identical sibling donors and one an HLA-haploidentical related donor. Moderate-severe chronic GVHD developed in 41% of transplanted patients (Figure 2B.). Four of the 11 patients with chronic GVHD have successfully discontinued systemic immunosuppressive therapy at a median (range) of 2.5 (1.4 – 7.4) years, while 7 are still receiving immunosuppression.

Figure 2. GVHD.

Grades 2–4 acute GVHD (A) The cumulative incidence of grades 2–4 acute GVHD at day 100 was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.57). The cumulative incidences of grade 3 and grade 4 acute GVHD were 0.05, each (95% CI: 0.009, 016). Moderate-severe chronic GVHD (B) The cumulative incidence of moderate-severe chronic GVHD at 2 years was 0.41 (95% CI: 0.25, 0.57). The dashed lines represent 95% CI.

Non-hematologic Toxicities, Non-relapse Mortality and Causes of Death

Table 5 summarizes non-hematologic toxicities within the first 100 days. Multiple toxicities could be accumulated in a given patient. A total of 8 episodes of severe non-hematologic toxicity occurred in 6 patients within the first 100 days, with fatal outcome in 2 patients (pneumonia and acute GVHD with gastrointestinal and liver involvement). The day 100 NRM was 5%.

Table 5.

Grades 3–5 non-hematologic toxicities, infectious complications and causes of death.

| Characteristic | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Non-hematologic toxicity at day 100 (events, n) | |||

| Cardiovascular | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Infectious | 70 | 0 | 1 |

| Metabolic | 29 | 2 | 1 |

| Neurologic | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Pulmonary | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Renal | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Infectious complications at day 100 (events, n) | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-neutropenic fever | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Adenovirus viremia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacteremia/bacterial sepsis | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| CMV reactivation | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| CMV duodenitis | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CMV pneumonitis | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fungal pneumonia/infection | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| HHV6 reactivation | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| RSV/viral upper respiratory tract infection | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Causes of Death, n | |||

| Relapse/Progression | 10 | ||

| GVHD with or without infection | 3 | ||

| Infection (Pneumonia) | 3 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | ||

There were 13 episodes of neutropenic fever, 17 episodes of documented bacteremia/sepsis and 4 episodes of bacterial pneumonia, of which one was fatal (Strenotrophomonas). Sixteen patients experienced CMV reactivation, 1 patient developed CMV duodenitis and 1 patient was diagnosed with CMV pneumonitis, none of which was fatal.

The leading causes of NRM were GVHD (n=3) and infections (n=3). One patient died of unknown causes (this patient’s death was classified as NRM). The estimated probability of NRM at 2 years was 24% (Figure 1C).

Relapse/Progression

Thirteen of 38 patients (34%) experienced relapse/progression, including 4 with AML, 4 with myelofibrosis, 2 with myeloproliferative disease/MDS and 1 each with NHL, CML and renal cell cancer. Ten of 13 patients died of relapse/progression, which remained the leading cause of death. The estimated probability of relapse/progression was 36% at 2 years (Figure 1D).

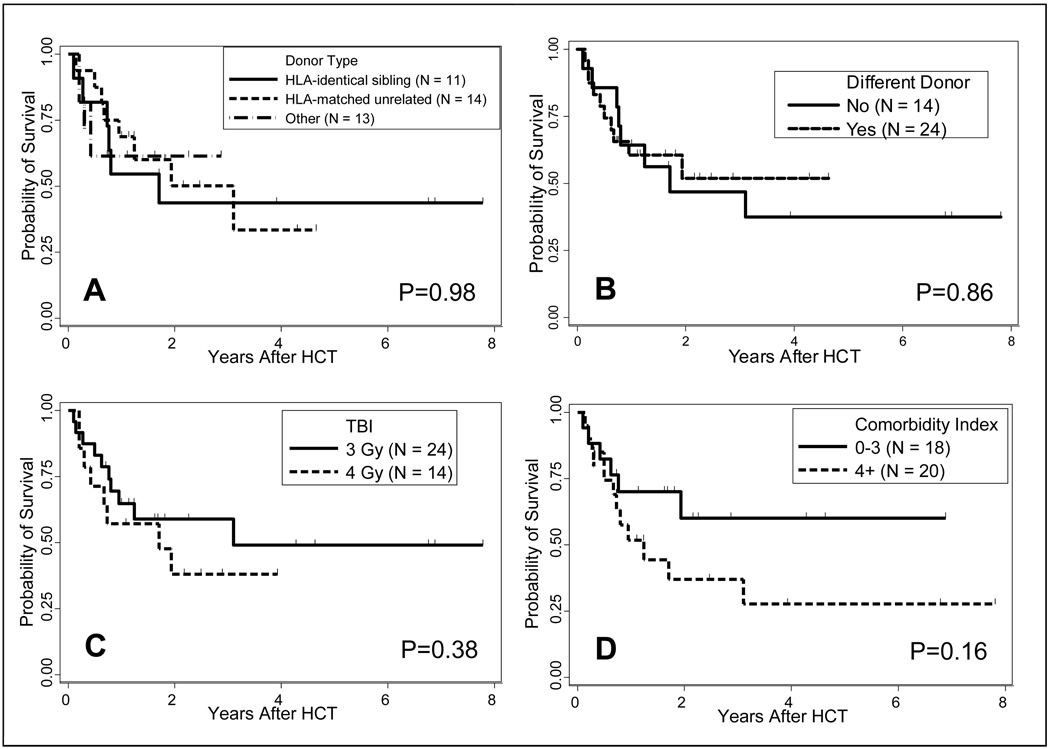

Survival

The median follow up among surviving patients was 2.0 (range 0.7 to 7.8) years. The estimated overall survival was 49% at 2 years and 42% at 4 years (Figure 1B). Within the limitations of the small number of patients studied, donor type did not have an impact on overall survival in univariate analysis (Figure 3A). At 2 years the estimated probability of survival for patients with HLA-identical sibling donors was 44% (95% CI: 15%, 70%, n=11), compared to 50% (95% CI: 21%, 73%; n=14) for patients with HLA-matched unrelated donors and 61 % (95% CI: 27%, 84%; n=13; P=0.98) for patients who received either HLA-mismatched unrelated, HLA-haploidentical related or double UCB grafts.

Figure 3.

Impact of donor type (A), using same vs. different donor (B), TBI dose (C) and HCT comorbidity index score (D) on overall survival.

Further, patients who received salvage HCT from the original donor had outcomes similar to those with different donors (Figure 3B), with a 2-year probability of survival of 47% (95% CI: 19%, 71%; n=14) compared to 52% (95% CI: 27%, 72%, n=25; P=0.86). Also, estimated probabilities of 2-year survival of patients receiving 3 or 4 Gy respectively, were comparable [59% (95% CI: 35%, 76%; n=24), and 38% (95% CI: 13%, 63%; n=14); P=0.38; Figure 3C].

Finally, while there was a trend toward worse overall survival for patients with high HCT Comorbidity Index scores, this difference did not reach statistical significance in univariate analysis (Figure 3D). Estimated 2-year probability of survival for patients with HCT-CI scores of 0–3 was 60% (95% CI: 30%, 81%; n=17) compared to 37% (95% CI: 15%, 60%) for patients with HCT-CI scores of 4 or more (n=21; P=0.16).

DISCUSSION

Primary and secondary graft rejections have been associated with poor prognosis. Because graft rejections are relatively uncommon, few studies have been published that address management of this serious complication. Rescue of patients with a salvage HCT is a promising approach that could potentially provide long term survival; however, there has been no consensus on donor selection or the nature of conditioning regimens.

An abstract from the 2008 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology summarizing data of the Center for International Bone Marrow Transplant Research on 122 patients undergoing second unrelated donor transplants after primary non-engraftment represented the largest current dataset, with a disappointingly low overall survival of 11% and high (86%) treatment related mortality at 1 year [24]. These results might be explained, in part, because of the use of myeloablative conditioning for second transplants in patients who had already been heavily pretreated.

Similar findings were reported by Kedmi et al. [25] in a single-institution analysis of salvage HCTs performed between 1981 and 2007. In this cohort, 144 patients (median age 20.7 years) underwent salvage allogeneic HCT, 62 of them for primary or secondary graft rejection. The day 100 transplant-related mortality was 45.5%, with a 1 year overall survival of 20%. Twenty-three of 80 patients receiving reduced intensity regimen survived at 1 year as compared to 6 of 64 who received myeloablative regimens, though the specific regimens were not described.

Other, smaller series have described more encouraging results, but better outcomes seemed to be limited to pediatric patients [12,26,27].

Chewning et al [10] reported on 16 patients who received second allogeneic HCTs at a median of 45 days following first HCTs, using primarily fludarabine-based conditioning in combination with cyclophosphamide or thiotepa and added ATG or alemtuzumab. These regimens resulted in an impressive 100% engraftment rate. The overall survival at 3 years was 35%, but, importantly, only 1 of 8 patients older than 20 years survived more than 6 months.

Heinzelmann et al. [11] used total lymphoid irradiation in conjunction with anti-T-lymphocyte antibodies (OKT3 and/or ATG) for second HCTs, after allograft rejection or graft failure. Eleven of 14 patients engrafted (78%). Among 7 children the 2 year overall survival rate was 85.7%, with a very favorable toxicity profile. In contrast, none of the 7 adults survived beyond 200 days, with 6 dying of non-relapse causes.

Jabbour et al. [9] used fludarabine and ATG to condition 9 patients with allograft failure for second HCT (median age was 49 years). Six of the 9 (67%) engrafted, however, only one patient remained alive at last follow up; the high mortality rate was mainly due to acute GVHD and infections.

More encouraging outcomes were reported by Byrne et al. [8] in a study involving 11 adult patients undergoing second HCT after graft rejection. The preparative regimen for 2nd HCT consisted of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and alemtuzumab. Nine patients (81%) engrafted. With a median follow-up of 29 months 5 of the 11 patients were alive; there were 2 treatment-related deaths, while 4 patients died of progressive disease.

While differences in patient and transplant characteristics made direct comparison between the above series difficult, some generalized conclusions may be drawn. Many salvage transplants failed because of high relapse- and non-relapse mortality rates, the combined effects of pre-existing organ damage, more advanced disease and more profound immunosuppression associated with the second preparative regimen. The intensification of the immunosuppressive regimens promoted engraftment, but led to higher rates of infections and decreased graft versus tumor effects. Nonmyeloablative conditioning for salvage HCT produced better outcomes than high dose regimens, especially in adults.

In our study, conditioning with fludarabine and 3 or 4 Gy TBI for salvage HCT was well tolerated and resulted in an engraftment rate of 87%. The regimen was based on our primary nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen for allogeneic HCT, which consisted of fludarabine and 2 Gy TBI [3]. The TBI doses 3 and 4 Gy used for our salvage regimen were slightly higher, and were selected for specific reasons. The main components of engraftment resistance have been immune mediated host-versus-graft reactions [28]. The effector cells of these reactions, the host T-lymphocytes are radiation sensitive. The relationship between irradiation dose and cell killing is non-linear, thus 3 or 4 Gy TBI likely eradicated residual host immune cells that otherwise would have mediated graft rejection [29,30]. Studies in DLA-identical littermate dogs have shown that augmentation of immunosuppression by increasing TBI from 2 Gy to 4.5 Gy increased the rate of stable donor marrow engraftment from 0 to 41% in the absence of postgrafting immunosuppression [31–33]. One fundamental difference between the various forms of anti-T-lymphocyte antibodies (OKT3, ATG or alemtuzumab) and TBI was that while the former provided different degrees of in vivo depletion affecting both host and donor T-lymphocytes, TBI impacted only the host immune system, leaving the incoming donor lymphocytes intact. TBI, therefore, allowed donor T-cells to exert the desired graft- versus-host effect both for overcoming engraftment barriers and control of underlying malignancies.

With one exception our analysis included adult patients with primary or secondary allograft rejections. Their median age was 56 years; only one patient in this cohort was younger than 21, while the oldest patient was 68 years old. The 2 year NRM associated with our preparative regimen was 24%, which was comparable to that seen after our standard nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen of fludarabine and 2 Gy TBI in the first transplant setting [34,35]. Relapse has remained a problem, highlighting the importance of the functional preservation of donor T-lymphocytes to achieve potent allogeneic graft-versus-tumor effects.

An interesting finding in this cohort was that 4 of the 5 patients who failed salvage HCT were among 6 patients with myelofibrosis. While this number was too small to draw definitive conclusions, results suggested that alternative conditioning regimens should be developed for patients with myelofibrosis, who have failed their first HCT. Graft rejection has been a considerable problem in these patients after other conditioning regimens as well [36].

Based on the current analysis, we concluded that graft rejection following allogeneic HCT could be effectively corrected by salvage transplantation using conditioning with fludarabine and 3 or 4 Gy TBI, with resultant long-term survival in 40–50% of patients. This treatment modality could be offered to older patients, to those lacking HLA-identical sibling donors and to patients with comorbid conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the research nurses Michelle Bouvier and Hsien-Tzu Chen and data manager Gresford Thomas for their invaluable help in making the study possible. The authors also wish to thank Helen Crawford, Bonnie Larson and Sue Carbonneau for manuscript preparation, and the transplant teams, physicians, nurses, and support personnel for their care of patients on this study.

Grant support

This study was supported by grants CA78902, CA18029, CA15704 and CA49605 from the National Cancer Institute, HL088021 and HL36444 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented as poster presentation at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 8, 2008 (Abstract #3272).

The authors have no relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, et al. Bone-marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:832–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197504172921605. 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kernan NA, Bartsch G, Ash RC, et al. Analysis of 462 transplantations from unrelated donors facilitated by The National Marrow Donor Program. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:593–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303043280901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, et al. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood. 2003;101:1620–1629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maris MB, Niederwieser D, Sandmaier BM, et al. HLA-matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;102:2021–2030. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laport GG, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorders. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rondon G, Saliba RM, Khouri I, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients who experienced graft failure postallogeneic progenitor cell transplantation. Results of a single institution analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Gomez-Almaguer D, Tarin-Arzaga LD, Morales-Toquero A, Cantu-Rodriguez OG, Manzano C. Second allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplants with reduced-intensity conditioning. Revista de Investigacion Clinica. 2006;58:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne BJ, Horwitz M, Long GD, et al. Outcomes of a second non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation following graft rejection. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:39–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbour E, Rondon G, Anderlini P, et al. Treatment of donor graft failure with nonmyeloablative conditioning of fludarabine, antithymocyte globulin and a second allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:431–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chewning JH, Castro-Malaspina H, Jakubowski A, et al. Fludarabine-based conditioning secures engraftment of second hematopoietic stem cell allografts (HSCT) in the treatment of initial graft failure. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzelmann F, Lang PJ, Ottinger H, et al. Immunosuppressive total lymphoid irradiation-based reconditioning regimens enable engraftment after graft rejection or graft failure in patients treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed N, Leung KS, Rosenblatt H, et al. Successful treatment of stem cell graft failure in pediatric patients using a submyeloablative regimen of campath-1H and fludarabine. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radich JP, Sanders JE, Buckner CD, et al. Second allogeneic marrow transplantation for patients with recurrent leukemia after initial transplant with total-body irradiation-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:304–313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stucki A, Leisenring W, Sandmaier BM, Sanders J, Anasetti C, Storb R. Decreased rejection and improved survival of first and second marrow transplants for severe aplastic anemia (a 26-year old retrospective analysis) Blood. 1998;92:2742–2749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron F, Storb R, Storer BE, et al. Factors associated with outcomes in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative conditioning after failed myeloablative hematopietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4150–4157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron F, Baker JE, Storb R, et al. Kinetics of engraftment in patients with hematologic malignancies given allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood. 2004;104:2254–2262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:729–735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratanatharathorn V, Nash RA, Devine SM, et al. Phase III study comparing tacrolimus (Prograf FK506) with cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation (BMT) Blood. 1996;88(Part 1) Suppl. 1 459a, #1826[abstr.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. Bone Marrow Transplant; 1994 Consensus conference on acute GVHD grading; 1995. pp. 825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marubini E, Valsecchi MG. Analyzing Survival Data from Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. Chichester, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schriber JR, Agovi MA, Ballen KK, et al. Second unrelated donor (URD) transplant as a rescue strategy for 122 patients with primary non engraftment: results from CIBMTR. Blood. 2008;112:295. #794[abstr.] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kedmi M, Resnick IB, Dray L, et al. A retrospective review of the outcome after second or subsequent allogeneic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grandage VL, Cornish JM, Pamphilon DH, et al. Second allogeneic bone marrow transplants from unrelated donors for graft failure following initial unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:687–690. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang P, Mueller I, Greil J, et al. Retransplantation with stem cells from mismatched related donors after graft rejection in pediatric patients. Blood Cells Molecules and Diseases. 2008;40:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storb R, Yu C, Barnett T, et al. Stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism in dog leukocyte antigen-identical littermate dogs given lymph node irradiation before and pharmacologic immunosuppression after marrow transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:1131–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vriesendorp HM. Radiobiological speculations on therapeutic total body irradiation. Oncology/Hematology. 1990;10:211–224. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(90)90032-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarbell NJ, Chin LM, Mauch PM. Total body irradiation for bone marrow transplantation. In: Mauch PM, Loeffler JS, editors. Radiation Oncology: Technology and Biology. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu C, Storb R, Mathey B, et al. DLA-identical bone marrow grafts after low-dose total body irradiation: Effects of high-dose corticosteroids and cyclosporine on engraftment. Blood. 1995;86:4376–4381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storb R, Raff RF, Appelbaum FR, et al. Fractionated versus single-dose total body irradiation at low and high dose rates to condition canine littermates for DLA-identical marrow grafts. Blood. 1994;83:3384–3389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storb R, Yu C, Wagner JL, et al. Stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism in DLA-identical littermate dogs given sublethal total body irradiation before and pharmacological immunosuppression after marrow transplantation. Blood. 1997;89:3048–3054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegenbart U, Niederwieser D, Sandmaier BM, et al. Treatment for acute myelogenous leukemia by low-dose, total-body, irradiation-based conditioning and hematopoietic cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:444–453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rezvani AR, Norasetthada L, Gooley T, et al. Non-myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation of relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre experience. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerbauy DMB, Gooley TA, Sale GE, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation as curative therapy for idiopathic myelofibrosis, advanced polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]