Abstract

In mice and young adult humans, the subventricular zone (SVZ) contains multipotent, dividing astrocytes, some of which, when cultured, produce neurospheres that differentiate into neurons and glia. It is unknown whether the SVZ of very old humans has this capacity. Here, we report that neural stem/progenitor cells can also be cultured from rapid autopsy samples of SVZ from elderly human subjects, including patients with age-related neurologic disorders. Histological sections of SVZ from these cases showed a GFAP-positive ribbon of astrocytes similar to the astrocyte ribbon in human periventricular white matter biopsies that is reported to be a rich source of neural progenitors. Cultures of the SVZ contained (1) neurospheres with a core of Musashi-1-, nestin-, and nucleostemin-immunopositive cells, as well as more differentiated GFAP-positive astrocytes; (2) SMI-311-, MAP2a/b-, and β-tubulin (III)-positive neurons; and (3) galactocerebroside-positive oligodendrocytes. Neurospheres continued to generate differentiated progeny for months after primary culturing, in some cases nearly two years post initial plating. Patch clamp studies of differentiated SVZ cells expressing neuron-specific antigens revealed voltage-dependent, tetrodotoxin-sensitive, inward Na+ currents and voltage-dependent, delayed, slowly inactivating K+ currents, electrophysiologic characteristics of neurons. A subpopulation of these cells also exhibited responses consistent with the kinetics and pharmacology of the h current. However, while these cells displayed some aspects of neuronal function, they remained immature, as they did not fire action potentials. These studies suggest that human neural progenitor activity may remain viable throughout much of the life span, even in the face of severe neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords: neural stem cells, neural precursors, neurospheres, neuronal differentiation, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

The subventricular zone (SVZ), which lies subjacent to the ependyma of the lateral ventricle, is an area of brain that is rich in neural progenitor cells (for reviews see Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000; Gage et al., 1995; McKay, 1997; Ming and Song, 2005; Temple and Alvarez-Buylla, 1999; Weiss et al., 1996). In rodents, the SVZ contains dividing, mulitpotent astrocytes that differentiate into neuroblasts destined for the olfactory bulb (Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo, 2002; Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996; Doetsch et al., 1999; Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993; Morshead et al., 1998). The adult human SVZ also contains dividing neural precursors that are clearly multipotent in vitro (Kirschenbaum et al., 1994; Kukekov et al., 1999; Moe et al., 2005b; Pincus et al., 1998; Sanai et al., 2004; Westerlund et al., 2003), and may be multipotent in situ (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006; Sanai et al., 2004). It has recently been shown, for example, that astrocytes cultured from human periventricular white matter biopsies containing the lateral part of the SVZ produced neurospheres and differentiated into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Interestingly, two of the biopsy samples used for cell culture in these experiments came from individuals in their mid to late 60s (Sanai et al., 2004). It is unknown whether the SVZ of very elderly subjects, who often have neurodegenerative disease, has the capacity to generate functionally viable neural stem/progenitor cells.

These studies, as well as our experience developing microglia and astrocyte cell cultures from rapidly autopsied neocortex of elderly subjects (Liang et al., 2002; Lue et al., 1996), suggested that short postmortem elderly human SVZ might also retain viable neural precursors that display multipotentiality in culture. Such cultures could have theoretical and practical value for several reasons. The functional characteristics of neuronal progenitors from elderly subjects, especially those with age-related neurodegenerative disease, are not well studied. Indeed, to our knowledge, only one report noted incidentally that the SVZ of elderly cortical stroke patients coming to autopsy showed histological evidence of neural stem/progenitor cells (Macas et al., 2006). Second, the research supply of SVZ material from human biopsies is limited, since investigators cannot dictate where neurosurgical resections, which produce the discarded tissue for experiments, will be directed. By contrast, rapidly autopsied SVZ—which is the largest neurogenic region of the human brain—is readily available at dozens of brain banks nationally and internationally, allowing functional study of neural stem cells in a host of neurodegenerative diseases. Finally, although biopsy material from the same patient has the critical advantage of permitting direct autologous donor-recipient transplantation, autopsied SVZ may nonetheless provide a more consistently available surrogate model for developing such applications.

Here, we show that rapid autopsy specimens of periventricular white matter/SVZ from elderly subjects, with and without neurodegenerative disease, contain multipotent neural precursors that can be expanded as neurospheres and differentiated into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes in vitro. In addition, we provide histological evidence that the elderly human SVZ in neurodegenerative disease contains the subependymal layer of GFAP+ astrocytes that has been demonstrated to be the source of neural stem cells in other species.

Materials and Methods

Autopsy brain tissue

Postmortem brain tissue for all experiments was obtained through the Sun Health Brain and Body Donation Program (Sun City, AZ). Specimens at autopsy were collected under IRB-approved protocols and informed consents that permitted use of the samples for research by the investigators. Subjects included in this study received antemortem evaluation by board-certified neurologists and postmortem evaluation by a board-certified neuropathologist. Evaluations and diagnostic criteria followed consensus guidelines for National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Centers.

Tissue for in vitro cell culture—qualitative and electrophysiological analyses

After brain removal, gross surface neuropathological abnormalities were documented, 1-cm thick frontal slabs were cut and photographed, and the slabs were bisected into hemispheres. Small blocks that included superior-lateral periventricular white matter were immediately dissected from right hemisphere slabs and processed for primary cell culture or for fixation and qualitative anatomical study (see below).

At expiration, subject ages for the morphological and electrophysiological analyses ranged from 56 to 97 years old (N=34), with a mean of 84.53 ± 1.6 (SEM) years. Postmortem intervals for the subjects averaged 3 h 2 ± 10 min. Diagnoses of patient condition included Alzheimer’s disease (N=14); Parkinson’s disease (N=1); Parkinson’s disease combined with Alzheimer’s disease (N=1); progressive supranuclear palsy (N=3); dementia with Lewy bodies (N=2); argyrophilic grain disease (N=1); frontotemporal lobar degeneration (N=1); control with microscopic changes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history (N=8); and neurologically normal for age (N=3). The latter group will be referred to as NND. Subject tissue used for these in vitro studies was collected from cases coming to autopsy between December 2004 and August 2007. There were no pre-selection criteria, save for customary exclusions due to potential biohazards (e.g., prior history of hepatitis).

Tissue for in vitro cell culture—quantitative analysis

Fresh PVWM containing the SVZ was acquired as above from 10 different postmortem cases. At expiration, subject ages ranged from 69 to 91 years old (N=10), with a mean of 83.2 ± 2.0 (SEM) years. Postmortem intervals for the subjects averaged 3.0 h ± 12 min. Diagnoses of patient condition included Alzheimer’s disease (N=7); Parkinson’s disease combined with dementia (N=1); neurologically normal for age (N=1); control with amyloid angiopathy (N=1). Subject tissue used for these in vitro quantitative studies was collected from cases coming to autopsy between January 2007 and April 2008. Again, there were no pre-selection criteria.

Tissue for qualitative immunohistochemical studies

Fresh PVWM containing the SVZ was acquired as above from 23 different postmortem cases; however, these tissue slabs were fixed for immunohistochemical investigations of GFAP-δ distribution. At expiration, subject ages ranged from 70 to 92 years, with a mean of 84.4 ± 1.2 years. Postmortem intervals for these subjects averaged 2 h 43 min. Diagnoses of patient condition included Alzheimer’s disease (N=10); progressive supranuclear palsy with dementia (N=1); dementia with Lewy bodies (N=1); control with microscopic changes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history (N=6); and neurologically normal for age (N=5).

SVZ dissection, tissue dissociation, and primary cell culture

To obtain SVZ cultures, we modified a protocol originally developed by our laboratory to culture cortical microglia and astrocytes from postmortem brain (Lue et al., 1996). From right hemisphere slabs taken at autopsy, periventricular white matter/SVZ was dissected from the superior lateral wall of the lateral ventricle, from the most anterior aspect of the lateral ventricle to approximately 3 cm posterior to that point (Fig. 1A). These dissections typically included approximately 1 cm of white matter, but specifically excluded any striatal gray matter. For parallel, control cultures, neocortical tissue blocks from the same cases were dissected from frontal and/or parietal regions. These latter slabs always included all adjoining subcortical white matter, except for a 2-cm margin around the lateral ventricle that contained the SVZ. Eliminating the SVZ from these samples provided a control to evaluate whether neurosphere development in our SVZ cultures derived from the SVZ or from surrounding periventricular tissue necessarily included in the SVZ dissections.

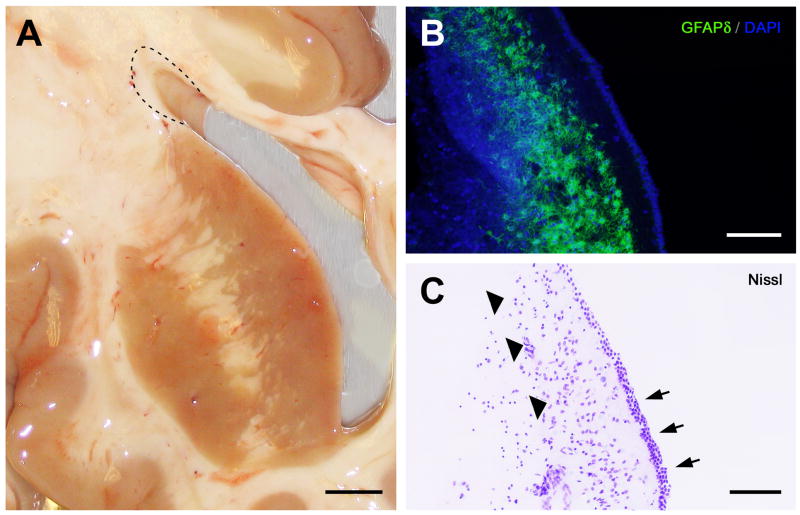

Fig. 1.

Dissection and anatomy of the human elderly subventricular zone. (A) Photograph of the right lateral ventricle and adjacent structures from an autopsied 96-year-old Alzheimer’s disease (AD) case with a postmortem interval (PMI) of 3.0 h. For cell culture, periventricular white matter samples (dashed line) that included the SVZ were dissected from the superior lateral wall of the lateral ventricle. Samples were collected from three to six levels of the frontally sectioned brain, typically from the anterior and mid-body of the lateral ventricle. The frontal section in panel A is just anterior to the level of the optic chiasm. Although samples for cell culture included white matter beyond the SVZ, neocortical control cultures from the same cases that included this white matter but excluded the SVZ did not develop neurospheres, as described elsewhere in the text (see Results). (B) GFAP-δ immunohistochemistry of the superior lateral wall of the human elderly lateral ventricle (frontal plane), showing a thin ribbon of GFAP-δ-immunoreactive astrocytes (green) lining the ventricular wall just deep to the ependyma. Cell nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). From an 85-year-old progressive supranuclear palsy case with a clinical history of dementia; PMI 4.45 h. (C) As can be seen in an adjacent cresyl violet-stained section of the same field, the characteristic ribbon of astrocytes (arrowheads) is actually separated from the ependymal layer (arrows) by a 50–100 μm hypocellular gap, similar to that observed in lateral ventricular biopsy samples from younger patients (e.g., Sanai et al., 2004; Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006). Scale bars: A, 2 mm; B, C, 100 μm.

Tissue was quickly transported in ice-cold Hibernate A medium (BrainBits, LLC; Springfield, IL) to a sterile laminar flow hood, mechanically dissociated into 1–2 mm pieces, and digested with 0.25% trypsin (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) and 0.1% DNAse (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a shaking water bath at 30°C. Digestion was stopped with fetal bovine serum (FBS). After passing the cell and tissue suspension through progressively finer metal screens, it was diluted with complete DMEM (minus phenol red). Complete DMEM consisted of 500 ml DMEM (high glucose, plus or minus phenol red, as noted; Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA); 50 ml FBS (Gemini Bio-Products; West Sacramento, CA); 10 ml HEPES (Irvine Scientific); 5 ml sodium pyruvate (Mediatech Cellgro, Herndon, VA); 5 ml penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen-Gibco); and 0.5 ml gentamycin (Irvine Scientific). Cells and debris were separated using 50% percoll-gradient (Amersham/GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) centrifugation (13,000 rpm; refrigerated). The first layer of myelin and debris was discarded. The second layer of the gradient, which is rich in microglia and astrocytes (Lue et al., 1996) but also proved to be the most optimal source for neurospheres, was aspirated, washed, pelleted, gently triturated, washed a second time, resuspended in complete DMEM (plus phenol red), and transferred to a 75-ml tissue culture flask (Nunc, Rochester, NY).

Flasks with suspended cells were left undisturbed for 2–24 hours in a tissue culture incubator maintained at 37°C/7% CO2. As previously reported (Lue et al., 1996), some 98% of microglia became adherent under these conditions, such that culture supernatants that were relatively free of microglia could be transferred to a second set of 75-ml flasks for plating. To estimate viability and density of the cells remaining in suspension, 50 μl aliquots of cell suspension were subjected to trypan blue exclusion counting using a hemocytometer. In some cases, 10 ml of the suspension was also collected for mitogen expansion studies (see below).

The secondary flasks were left undisturbed, except for weekly medium replacement with complete DMEM, for 1–3 weeks in tissue culture incubators maintained at 37°C with 7% CO2, after which a portion of the supernatant was seeded into various receptacles depending on experimental requirements. When flasks became confluent, neurospheres and lightly adherent cell clusters were mechanically dislodged by brief gentle shaking, gently pelleted and triturated, and plated into a new flask; neurospheres were not intentionally dissociated during passage. Characterization studies typically used 6- or 12-well uncoated tissue culture plates (Corning, Lowell, MA) or plates and culture dishes coated with 10 μg/ml poly-L-lysine (PLL; Sigma) or a combination of PLL/10 μg/ml mouse laminin I (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Electrophysiology experiments employed uncoated or PLL/laminin-coated, sterilized Thermonox coverslips (Nunc) in 3- or 6-cm culture dishes. Immunocytochemical analysis was conducted in coated or uncoated 4-well chamber slides, flasks, and plates. Subsequent evaluations showed that the SVZ cultures in these vessels were primarily composed of semi-confluent astrocytes, nonadherent and adherent neurospheres, and various cell types budding from the neurospheres.

Mitogen expansion of SVZ neurospheres

In addition to allowing neurosphere-like clusters of cells to emerge in astrocyte-progenitor cultures maintained in complete DMEM, mitogen expansion of single-cell SVZ suspensions to neurospheres was undertaken in 11 cases using a modification of previously published protocols for embryonic and adult neural stem cells (Bez et al., 2003; Laywell et al., 2002; Ostenfeld et al., 2002; Reynolds and Weiss, 1992; Svendsen et al., 1999). Briefly, 10 ml of the single-cell suspensions being passed to secondary flasks (i.e., depleted of microglia) was gently pelleted, washed with proprietary, serum-free neurosphere proliferation medium (SFNPM; NeuroCult® NS-A Proliferation Kit; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), and resuspended in T-25 flasks (Corning) in SFNPM supplemented with 20 ng/ml recombinant human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), 10 ng/ml human fibroblast growth factor-basic (hFGF-b) (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 2 μg/ml heparin (StemCell Technologies). Fresh hEGF/hFGF-b-supplemented SFNPM was added every 2–3 days to the flasks. One to three weeks of exposure to hEGF plus hFGF-b resulted in SVZ neurospheres that detached from the flask surface and continued to grow in diameter. With this protocol, neurospheres from elderly postmortem SVZ reached diameters up to 400 μm in diameter. When needed for experiments, they were gently pelleted and plated on coated or uncoated culture plates, dishes, or Thermonox cover slips.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Antibody characterization

All antibodies used in the present study (Table 1) have been characterized previously, and the staining pattern for most of them is well established in human brain tissue. A brief summary is provided for each antibody, describing the target antigen, the antibody’s original production, characterization, and specificity controls (Saper and Sawchenko, 2003). In addition for each antibody used in the present study, we either omitted the primary antibody or used preimmune serum (for anti-GFAP-δ) in our immunostaining procedures as a specificity control, which resulted in no staining.

Table 1.

Antibodies used

| Antibody | Host | Dilution | Source/Catalog # | Immunogen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFAP | mouse monoclonal | 1:2000 | Chemicon (Millipore)/MAB3402 | purified GFAP | astrocytes |

| GFAP | rabbit polyclonal | 1:2000 | Dako/Z0334 | GFAP isolated from cow spinal cord | astrocytes |

| GFAP-δ | rabbit polyclonal | 1:750 | Chemicon (Millipore)/AB9598 &1 | QAHQIVNGTPPARG | astrocytes |

| HLA-DR (major histocompatibility complex, class II invariant chain) | mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | MP Biomedicals/69303 | activated human mononuclear cells | microgila |

| Nonphosphorylated neurofilaments | mouse monoclonal | 1:500 | Covance/SMI-311R | homogenized rat hypothalmi | neuronal |

| β-tubulin (III) | mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | Sigma/T8660 | CESESQGPK | immature |

| MAP2a/b | mouse monoclonal | 1:200 | Chemicon (Millipore)/MAB378 | bovine MAP2 | neuronal |

| galactocerebroside | rabbit polyclonal | 1:1000 | Sigma/G9152 | Purified galactocerebrosides I and II | oligodentrocytes |

| Nestin | mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | Chemicon (Millipore)/MAB5326 | PWDDSLRGAV AGAPKTALET ESQDSAEPSG SEEESDPVSL EREDKVPGPL EIPSGMEDAG PGADIIGVNG QGPNLEGKSQ HVNGGVMNGL EQSEEVGQGM PLVSEGDRGS PFQEEEGSAL KTSWAGAPVH LGQGQFLKFT QREGDRESWS |

neural |

| Nucleostemin | rabbit polyclonal | 1:000 | Chemicon (Millipore)/AB5689 | CEQSTRSFIL DKIIEEDDA |

stem marker |

| Musashi-1 | rabbit polyclonal | 1:200 | Chemicon (Millipore)/AB5977 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 5-21 of Musashi-1 | neural cell/proliferation |

| amyloid beta 17-24 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | Chemicon (Millipore)/MAB1561 | Synthetic amyloid beta protein, human, amino acid residues 1-24 | amyloid |

| amyloid beta 1-17 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:1000 | Chemicon MAB1560 | synthetic amyloid beta protein, human, amino acid residues 1-17 | amyloid |

antibody code 100501; Roelofs et al., 2005.

Glial brillary acidic protein (GFAP)

GFAP is a type III intermediate filament having a MW of 50,000 (Fuchs and Weber, 1994), and is expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) in astrocytes (de Armond et al., 1980). We used two different antibodies to localize GFAP. The first was a protein-A-column purified antibody (Cat# MAB3402, GA5 clone; Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA) produced in mice immunized with purified GFAP from porcine spinal cord (Debus et al., 1983a). On conventional immunoblots of whole brain homogenates, the antibody visualized a single band at 51 kDa (Debus et al., 1983a). This antibody stained cells of the human glioma cell lines U333CG and U343MG, which are known to contain GFAP (Paetau et al., 1979) and failed to stain cells of the human RD cell line, which do not contain GFAP but do contain other intermediate filaments (Debus et al., 1983b). In paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed tissue sections, the antibody stained only astrocytes in rat cerebellum and spinal cord and astrocytes in human optic nerve, brain, and astocytoma sections (Debus et al., 1983a). With identically fixed human brain tissue as in the present study, omission of the antibody resulted in no staining (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006), and when the antibody was progressively diluted from 1:500 to 1:5000, staining went from dense to light to imperceptible (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining astrocytes in SVZ (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006) and astrocytes in culture derived from periventircular human biopsies (Sanai et al., 2004).

The second anti-GFAP antibody (Cat# Z0334; Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA) was an affinity-purified antibody developed in the manufacturer’s R&D lab. Rabbits were immunized with GFAP isolated from cow spinal cord (Dahl et al., 1982). On conventional immunoblots of whole brain homogenates, the antibody visualized a single band at ~50 kDa (Coulpier et al., 2006). The manufacturer states that the antibody does not cross-react with other intermediate filaments in different cell types (i.e., cytokeratins in cells of epithelial origin, vimentin in mesenchymal cells), and in a dilution range of 1:100–1:500, the antibody does not stain elements in connective tissue, pancreas, heart, mucosal tissues, and lymphoid tissues. In PFA-fixed human cerebral cortex, the antibody stained astrocytes at dilutions from 1:500 to 1:3000, with no staining for antibody dilutions greater than 1:5000 using avidin-biotin-peroxidase procedures (Halliday et al., 1996). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining astrocytes in human SVZ (Zecevic et al., 2005).

Delta isoform of GFAP

Human GFAP-δ is a GFAP isoform that is encoded by an alternative splice variant of the GFAP gene, differing from the predominant splice form, GFAP-α, by its C-terminal protein sequence (Hol et al., 2003; Roelofs et al., 2005). The anti-GFAP-δ antibody was raised in rabbits against a recombinant peptide of the last 14 amino acids (produced by Pepscan, Lelystad, the Netherlands) of the human GFAP-δ protein sequence (Roelofs et al., 2005). An extensive BLAST search by these authors was carried out to exclude homology of the 14-aa-long C-terminal sequence to other proteins (Roelofs et al., 2005). On conventional immunoblots of whole cell lysates of human astrocytoma-derived cell lines U373 and U343, the antibody visualized a single band at ~60 kDa (Perng et al., 2008). The antibody selectively stained a subpopulation of astrocytes located in the subpial zone of the human cerebral cortex, the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, and, most intensely, a ribbon of astrocytes following the ependymal layer of the cerebral ventricles (Roelofs et al., 2005). Omitting the antibody or using pre-immune serum resulted in no staining with avidin-biotin-peroxidase procedures (Roelofs et al., 2005). This same antibody was also purchased from a commercial source (Cat# AB AB9598, lot 0603024570; Chemicon/Millipore), which is produced identically by the manufacturer as in the original study and has the same performance characteristics. The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody (code 100501; (Roelofs et al., 2005); Cat# AB9598, lot 0603024570) revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining a thin ribbon of astrocytes in human SVZ (Roelofs et al., 2005).

HLA-DR

HLA-DR is a major histocompatibility complex, class II (MHCII) cell surface receptor that is expressed in the human CNS primarily on microglia (McGeer et al., 1988). The anti-HLA-DR antibody (Cat# 693031, clone LN-3; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) used to identify microglia in the present study was produced in mice hyperimmunized with homogenized nuclei from pokeweed mitogen-stimulated, human peripheral-blood lymphocytes (Epstein et al., 1984; Marder et al., 1985). This antibody reacted with the HLA-DR surface antigen of 85% of human B cell lymphocytes (Marder et al., 1985), and stained microglia but not astrocytes of the human brain (Sasaki et al., 1991). The SDS-PAGE profile of two proteins immunoprecipitated with this antibody from human B lymphoid cell lysates had molecular weights of 29 and 33 kDa, the molecular weights of the two chains of the MHCII molecule (Goyert et al., 1982; Marder et al., 1985). With identically prepared cultures of enriched human microglia as in the present study, omission of the antibody resulted in no staining (Mastroeni et al., 2008). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining somata and processes of ameboid and ramified cells in enriched human microglia cultures (Mastroeni et al., 2008).

Nonphosphorylated neurofilaments

Neurofilaments are neuron-specific intermediate filaments consisting of three major polypeptides with MWs of 200,000, 150,000, and 68,000 (Hoffman and Lasek, 1975). The anti-neurofilament antibody (Cat# SMI-311R; Covance, Emeryville, CA) was produced in mice immunized with homogenized rat hypothalami (Sternberger et al., 1982). On conventional immunoblots of rat brain homogenates, cytoskeletal preparations, or isolated neurofilaments, the antibody visualized a doublet band at 200 kDa (Goldstein et al., 1983; Sternberger and Sternberger, 1983). The antibody recognized high-molecular weight, non-phosphorylated neurofilaments from tissue of all parts of the CNS of rat brain (Ostermann et al., 1983; Sternberger et al., 1982), and stained neurons in fetal and adult human brain (Ulfig et al., 1998); it did not stain non-neuronal elements in liver, lung, thymus, adrenal gland, and intestine of rats (Ostermann et al., 1983). When the antibody was progressively diluted from 1:2000 to 1:5000, staining intensity diminished progressively until there was no staining with dilutions greater than 1:6000 (Goldstein et al., 1983). Omission of the antibody resulted in no staining in rat brain using avidin-biotin-peroxidase procedures (Shetty and Turner, 1995). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining somata and processes of bipolar and multipolar neurons in culture (Shetty and Turner, 1995).

β-tubulin(III)

β-tubulin isotype III is a neuron-specific microtubule protein with a MW of ~50,000 (Sullivan and Cleveland, 1986). The anti-β-tubulin(III) antibody (Cat# T8660, clone SDL.SDlO; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) was produced in mice by immunization with chemically synthesized peptide (BioSearch Corporation, San Rafael, CA.) corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of human β-tubulin(III) (Sullivan and Cleveland, 1986) conjugated to bovine serum albumin and m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide (Banerjee et al., 1990). After fusion, hybridoma cells were screened with purified β-tubulin(III) as the target, the clone SDL.SDlO was selected, and ascites were produced (Banerjee et al., 1990). The manufacturer states that on conventional immunoblots of whole cell extract of rat brain, the antibody visualizes a single band at 46 kDa. The same molecular-weight band was also visualized in immunoblots of whole cell lysates of human neuroblastoma cells and of cultured human olfactory epithelium cells (Hahn et al., 2005). The antibody tested positive against isolated β-tubulin(III) and negative to α-tubulin and β-tubulin(II) (Banerjee et al., 1990). Immunohistochemistry (peroxidase-antiperoxidase method/DAB) on human biopsied olfactory epithelium using the same concentration of IgG isotype serum as the anti-β-tubulin(III) antibody or using nonimmune mouse serum resulted in no staining (Hahn et al., 2005). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining somata and processes of bipolar and multipolar neurons in culture differentiated from human embryonic neural stem cells (Wright et al., 2003).

Microtubule-associated protein (MAP2a/b)

MAP2 is one of a number of high-molecular-weight brain polypeptides (MW 300,000) (Kim et al., 1979) that associates with microtubules (Berkowitz et al., 1977) in neuronal cell bodies and dendrites (Caceres et al., 1984). By SDS gel electrophoresis, MAP2 separates into two closely migrating polypeptides designated as MAP2a and MAP2b (Binder et al., 1984). The anti-MAP2a/b antibody (Cat# MAB378, clone AP-20; Chemicon/Millipore) was produced in mice immunized with purified bovine MAP2 (Caceres et al., 1984). The manufacturer states that it reacts with MAP2 in human, rat, mouse, avian, bovine, and amphibian nervous system. On conventional immunoblots of whole brain or hippocampi extracts, this antibody visualized a doublet band at 300 kDa (Caceres et al., 1984). The epitope for this antibody lies between amino acids 995 and 1332 of human MAP2 (Kalcheva et al., 1994), and the antibody reacted with MAP2a/b but not with MAP2c (Fujimori et al., 2002). The antibody stained neuronal perikaryon and dendrites in rat hippocampus and cerebellum (Caceres et al., 1984) and human spinal cord (Kikuchi et al., 1999); preadsorption of the antibody with a molar excess of purified brain MAP2 or incubation with nonimmune serum eliminated staining (Caceres et al., 1984). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining somata and processes of bipolar and multipolar neurons in culture (Caceres et al., 1986).

Galactocerebroside

Galactocerebroside is the major galactosphingolipid of myelin and is expressed in cell membranes of oligodendrocytes in the CNS. The anti-galactocerebroside antibody (Cat# G9152, Sigma) is a pooled, delipidized antiserum produced in rabbits by repeated injections of a mixture of purified galactocerebrosides I and II conjugated to Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) (Benjamins et al., 1987). As assessed in a liposome-glycolipids ELISA assay, the antibody recognized only galactocerebrosides I and II at a titer of 1:10240 and did not react with other glycolipids such as sulfatide, psychosine, glucocerebroside, mixed gangliosides, asialo GM1, monogalactosyl diglyceride, digalactosyl diglyceride, ceramide, phosphatidyl choline or cholesterol as assessed by dot-blot immunoassay (Benjamins et al., 1987). In the same study, Western blot analysis of mouse brain homogenates showed that the antibody did not cross-react with any glycoproteins in brain tissue. The antibody stained oligodendrocytes in culture (Benjamins et al., 1987) and stained cells of two human cell lines (U373-MG and SK-N-MC) of CNS origin known to have galactocerebroside on their cell surface and failed to stain HTB-138 cells, a human glioma cell line that does not have galactocerebroside on their cell surface (Harouse et al., 1991). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining small round cells with an associated network of elaborate processes having the morphology of cultured oligodendrocytes (Benjamins et al., 1987).

Nestin

Nestin is a high-molecular-weight (MW 240,000), class VI intermediate filament protein transiently expressed during mammalian development (Hockfield and McKay, 1985) and in proliferating CNS stem cells (Lendahl et al., 1990). The protein-A-column purified anti-nestin antibody (Cat# MAB5326, clone 10C2; Chemicon/Millipore) was developed in the manufacturer’s R&D laboratory based on the work of Messam et al. (Messam et al., 2002; Messam et al., 2000a; b). It was made in mouse (Messam et al., 2000b). As with the manufacturer, these authors used as an immunogen a 150-amino-acid fragment derived from cloned nestin cDNA of human fetal brain cells coupled to glutathione S-transferase (Messam et al., 2000a). This sequence corresponds to positions 1464 to 1614 of the human nestin protein sequence (Dahlstrand et al., 1992). On conventional immunoblots of whole cell lysates from U373 and U251 human glioma cell lines and the immortalized human neuroglial cell line, SVG (Major et al., 1985), the purified antibody visualized a doublet band that migrates to 220 kDa-240 kDa (Messam et al., 2000a). The antibody does not cross-react with either vimentin or GFAP (Gu et al., 2002), and cultured fetal human neural progenitors are immunopositive (Messam et al., 2000a). Omission of the antibody resulted in no staining (Gu et al., 2002; Messam et al., 2000a). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining small cells with short processes in undifferentiated, human neural progenitor cell cultures (Messam et al., 2000a).

Nucleostemin

Nucleostemin is a 61.997 kDa protein found in the nucleoli of embryonic stem cells and adult neural stem cells (Tsai and McKay, 2002), and in primitive cells in bone marrow and cancer cells (Ma and Pederson, 2007). It is not found in differentiated cells of most adult tissues (Tsai and McKay, 2002). The anti-nucleostemin antibody (Cat# AB5689; Chemicon/Millipore) was developed in the manufacturer’s R&D laboratory based on the work of R. D. McKay’s lab (Tsai and McKay, 2002). It was raised in rabbits against a synthetic peptide corresponding to an 18-peptide sequence (positions 513–530) near the C-terminal end of the human nucleostemin protein (Charpentier et al., 2000). The antibody stained nucleoli in proliferating cells of the U2OS human osteosarcoma cell line (Ma and Pederson, 2007). On conventional immunoblots of whole cell lysates of these cells (Ma and Pederson, 2007) or NT2/D1 cells (manufacturer’s R&D laboratory), the antibody visualized a single band at ~63 kDa. A study by Ma et al. using this antibody provides a specificity control (Ma and Pederson, 2007): The antibody failed to stain nucleoli of cells when the endogenous tumor suppressor p14ARF (ARF)—an upstream negative regulator of nucleostemin is—expressed and, conversely, strongly stained nucleoli in proliferating cells when ARF is knocked down through siRNA (Ma and Pederson, 2007). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining subnuclear-appearing organelles having the morphology of nucleoli in small round proliferating human cells (Ma and Pederson, 2007).

Musashi-1

Musashi-1 is an RNA-binding protein that plays roles in maintenance of stem-cell state, differentiation, and tumorigenesis. It is selectively expressed in neural progenitor cells, including neural stem cells (Sakakibara et al., 1996). The affinity-purified, anti-Musashi-1 antibody (Cat# AB5977; Chemicon/Millipore) was developed in the manufacturer’s R&D laboratory based on the work of H. Okano’s lab (Sakakibara et al., 1996). It was raised in rabbits against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 5-21 of Musashi-1; the manufacturer states that the purified antibody reacts with human and mouse Musashi-1. On conventional immunoblots of whole eye and neural retina extracts, the antibody visualized a single band at 39 kDa (Raji et al., 2007). This antibody stained the paranuclear cytoplasm of proliferating cells in the SVZ (Maslov et al., 2004) and in undifferentiated cells of neurospheres derived from the SVZ (Widera et al., 2006). No staining was observed when the antibody was omitted (Widera et al., 2006). The pattern of staining observed in the present study with this antibody revealed the same pattern of cellular morphology that has been reported previously, staining the cytoplasm of small round cells in undifferentiated, proliferating neurospheres derived from the SVZ (Widera et al., 2006).

Amyloid β

Amyloid β protein is an ~4,000 Da (Haass et al., 1992) alternative proteolytic-cleavage peptide of the ubiquitously expressed type I integral membrane glycoprotein amyloid β-protein precursor (Selkoe, 1994), and that accumulates abnormally in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients as extracellular deposits commonly known as plaques (Roher et al., 1986). We used two different monoclonal antibodies to localize amyloid β. The first was an antibody (Cat# MAB1561, 4G8 clone; Chemicon/Millipore) produced in mice immunized repeatedly with a purified, KLH-conjugated-24-residue synthetic peptide (produced by Peninsula Laboratories/Bachem Americas, Inc., Torrance, CA) corresponding to the published sequence of the Alzheimer’s disease cerebrovascular amyloid peptide (Glenner and Wong, 1984). The manufacturer states that the protein-A-column purified antibody recognizes an epitope located between amino acids 18-22 of the amyloid β peptide. The manufacturer also states that on conventional immunoblots of whole human brain lysates the antibody visualizes a band migrating at ~5 kDa. By ELISA, the antibody detected as little as 0.2 ng of purified human amyloid β/100 ul (Kim, 1988). The antibody selectively stained both vascular and neuritic plaque amyloid found in Alzheimer brain tissue (Alafuzoff et al., 2008; Kim, 1988) and amyloidβ in cultured hippocampal neurons (Brewer, 1996). Preadsorption of the antibody with amyloidβ peptide (residues 12-28), omission of the antibody, or addition of an irrelevant IgG resulted in no staining (Brewer, 1996). For a positive control for this antibody in the present study, we used human frontal sections containing both the SVZ and cerebral cortex, the latter of which should show positive staining. The pattern of staining observed revealed the same pattern of extracellular staining that has been reported previously, staining both vascular and neuritic plaque amyloid found in cerebral cortex of Alzheimer brain tissue (Alafuzoff et al., 2008; Kim, 1988).

The second monoclonal anti-amyloid β antibody (Cat# MAB1560, 6E10 clone; Chemicon/Millipore) was produced and characterized identically as was the first, except that a synthetic peptide corresponding to the first 17 amino acids of the amyloid β peptide conjugated to KLH was used as the immunogen (Kim, 1990). The manufacturer states that on conventional immunoblots of whole human brain lysates the protein-A-column purified antibody visualizes a band migrating at ~5 kDa. Preadsorption of the antibody with amyloid β peptide (residues 12-28), omission of the antibody, or addition of an irrelevant IgG resulted in no staining of hippocampal neurons in culture (Brewer, 1996). The same positive control results for this second monoclonal anti-amyloid β antibody were obtained as with the first (4G8 clone).

Staining procedures

For immunohistochemical analysis of tissue sections, periventricular white matter/SVZ blocks were collected at autopsy in the same manner as that for cell culture. Tissue blocks were immersion fixed at 4°C for 24–36 h in freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1M PO4 (phosphate buffer, PB) or freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde/PB. The blocks were then washed extensively in PB, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, sectioned serially at 20 μm or 40 μm on a cryostat, and stored at −20°C in ethylene glycol/glycerol/PB solution until needed. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) fluorescence immunohistochemistry to identify astrocytes followed published protocols (e.g., Freund, 1993). Briefly, extensively washed sections were blocked with either 3% normal goat serum (NGS)/0.1% Triton X-100 or 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/0.1% Triton X-100, and then incubated with mouse anti-human GFAP (1:2000; Chemicon/Millipore), rabbit anti-human GFAP (1:2000; Dako North America, Inc) or rabbit anti-human GFAP-δ (1:750; Chemicon/Millipore; and [antibody code 100501; (Roelofs et al., 2005)], for 18–48 h at 4°C. The diluent for all solutions and washes was 0.05 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4. After three washes, the sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit Alexa-fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1500; Invitogen/Molecular Probes) for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C, washed, mounted on microscope slides, and coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). All washes included 1% NGS and 0.1% Triton in TBS. Deletion of primary antibody or incubation with pre-immune serum resulted in abolition of specific immunoreactivity. Adjacent serial sections were stained with cresyl violet for cell layer identification and verification that the ependymal layer of the adjacent immunofluorescent sections was intact. For some sections, nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) before mounting.

For immunocytochemical analysis of cell cultures, medium was aspirated and cultures were briefly washed with either room temperature phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen-Gibco) or 37°C PEM (100 mM PIPES, 2 mM EGTA, l mM MgSO4, pH 6.9), then fixed with either room temperature acetone-ethanol (1:1) or warmed 2% paraformaldehyde diluted in PBS for 15 min at 4°C (Giepmans et al., 2005). The cells were washed briefly, and nonspecific binding was blocked with either 3% NGS (Sigma) or 1% BSA (Sigma)/0.1% Triton for 45 min at room temperature. Cultures were then incubated with primary antibody diluted in either PBS or 1% NGS/0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The following antibodies and dilutions were employed in the various experiments: 1:1,000 anti-human B lymphocyte (CD74, clone LN-3) (MP Biomedicals); 1:500 anti-SMI-311 (Covance/Sternberger Monoclonal); 1:1000 anti-β-tubulin (IIl) (Sigma); 1:200 anti-MAP2a/b (Chemicon/Millipore); 1:2000 anti-GFAP (Chemicon/Millipore); 1:2000 anti-GFAP (Dako North America, Inc.,); 1:1000 anti-galactocerebroside (Sigma); 1:1000 anti-nestin (Chemicon/Millipore); 1:1000 anti-nucleostemin (Chemicon/Millipore); and 1:200 anti-Musashi-1 (Chemicon/Millipore). Following three brief washes, cells were incubated with species-appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa-Fluor 594 fluorophors (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, or in some cases overnight at 4°C in the dark. Washes throughout all steps were with PBS for acetone-ethanol-fixed cultures, or with 1% NGS/0.1% Triton X-100/PBS or 1% BSA/0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for paraformaldehyde-fixed cultures. Colocalization experiments were carried out by incubating cultures sequentially in two primary antibody solutions, each from a different species, followed by incubation with species-appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 for one marker and Alexa Fluor 568 or 594 for the other marker. As with tissue sections, we observed no immunostaining when primary antibodies were deleted, replaced with pre-immune serum or with irrelevant (e.g., anti-CD68) antibodies of the same IgG class.

Immunostained periventricular white matter/SVZ tissue sections and cell cultures were examined on Olympus IX51 and Olympus IX70 microscopes equipped with epifluorescence illumination or confocal laser scanning using argon and krypton lasers (IX70). Findings were documented photographically with a Nikon DS-LI and Olympus DP-71 color digital cameras or, for confocal microscopy, by Fluoview software (Olympus). Contrast and brightness adjustments and overlay compositing were done with Adobe Photoshop CS3. Red-green fluorescence in all figures was converted to magenta-green in Photoshop so that red-green color-blind readers can correctly interpret color information. Co-localization of the green and red fluorophors appears as white in the converted image.

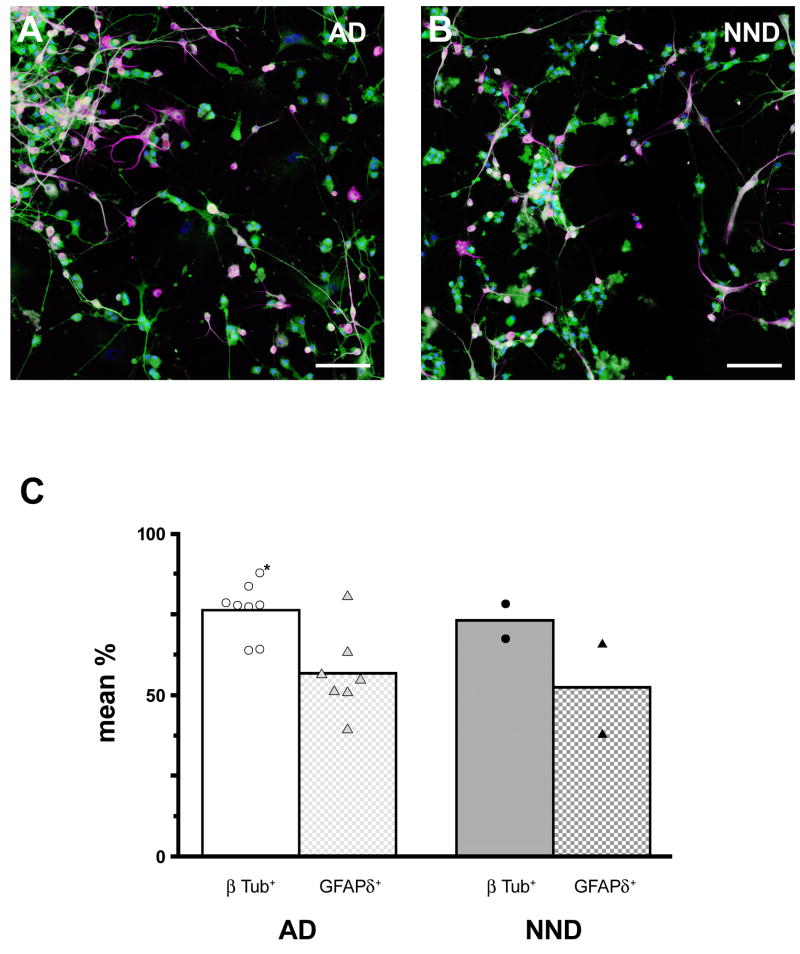

Quantitation of SVZ progenitor cell differentiation

All parts of the quantitation experiment were done blind with respect to case diagnosis. SVZ progenitor cells were acquired as before (see above) and maintained as adherent neurospheres in T-75 flasks until needed. Maintenance medium and feeding procedures were identical to those used for other cases described above for qualitative morphological and electrophysiological analyses.

For differentiation experiments, neurospheres were dislodged from the flasks, collected in suspension, gently centrifuged, and resuspended in DMEM complete. The pellet was triturated gently to achieve a suspension of single cells and small aggregates of cells (~2–10 cells). Equal volumes of cell suspension from each case were plated along with fresh DMEM complete into PLL/laminin-coated 12-well plates in quadruplicate (i.e., 500 μl/well, 3 cases per plate), and the cells were allowed to adhere for 24h in this medium. Plates were maintained in a 37 °C incubator, as before. We used a modified two-step procedure described by Wu et al. that enhances neuronal differentiation of stem cells (Wu et al., 2002). Briefly, plating medium was replaced by neuronal priming medium containing bFGF (Peprotech; 10 ng/ml), EGF (Peprotech; 20 ng/ml) and laminin (ATCC; 1μg/ml) dissolved in Neurobasal-A medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with N2 supplement (Invitrogen), Pen/strep, and L-glutamine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Triplicate wells from each case were exposed to priming medium for nine days, with half the volume of medium in each well being replaced with fresh priming medium every other day. For differentiation, mitogens were removed and cells were exposed to differentiation medium for ten days. Differentiation medium contained Neurobasal-A medium supplemented with B27 supplement, Pen/strep, and L-glutamine according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and 5% FBS. Again half the medium was replaced every other day with fresh differentiation medium. Cells were fixed with 2% PFA, as described above.

We carried out double immunocytochemical staining using a monoclonal antibody against the neuron-specific type III β-tubulin (1:1,000; Sigma) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against the δ isoform of GFAP (1:1,000; Chemicon/Millipore), the latter of which has been shown previously in the SVZ to stain the population of astrocytes that contain neural stem cells in the adult human brain (Roelofs et al., 2005). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor-488 and goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor-568 used at a concentration of 1:1,000. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, as before. Procedures followed those described above. Imaging was done with an Olympus IX51 microscope under epifluorescence illumination and documented digitally with an Olympus DP-71 color digital camera and software.

To obtain cell counts, we imaged three non-overlapping areas of well surfaces from each case. From each of these areas, single-channel (green, red, blue separately), high-resolution (4K × 2K pixels) montages were collected at 20× magnification. Acquisition image exposures were kept constant across all cases. The green channel captured β-tubulin III labeling, the red channel captured GFAPδ labeling, and the blue channel DAPI labeling. Montages were assembled and aligned in Adobe PhotoShop; each assembled montage sampled 2.18 mm2 of the well surfaces. The number of β-tubulin III+ cells in the merged green/blue channel of the digital montage was counted at 100 % magnification and separately the number of GFAPδ+ cells in the red channel of was counted. The total number of DAPI-labeled nuclei in the blue channel was also counted to obtain the total number of cells present in the sampled areas. Finally, the proportion of β-tubulin III+ cells was calculated as a percentage of total number of DAPI-labeled cells in each of the three sampled areas. These percentages were averaged to obtain a representative grand mean percentage for each case. The same percentages were calculated for GFAPδ+ cells.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological studies were conducted with SVZ cells that had been allowed to differentiate for periods of 3 days to 3 weeks after initial plating. The cells were maintained in complete DMEM in uncoated 3- or 6-cm plastic culture dishes (Corning), fibronectin- or PLL/laminin-coated culture dishes, or PLL/laminin-coated Thermonox coverslips in culture dishes. At room temperature (22 ± 1°C), the culture dishes were placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus IX70) and continuously superfused with a standard, extracellular solution composed of 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris base. Perforated, whole-cell patch recordings were then performed using previously described techniques (Horn and Marty, 1988; Wu et al., 2004). Briefly, patch pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with an intracellular recording solution containing 140 mM K-gluconate, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 using Tris base. The liquid junction potential (14 mV) was calculated using Clampex 9.2 (Axon Instruments/MDS, Sunnyvale, CA) and corrected post hoc. Amphotericin B was dissolved in DMSO (40 mg/ml; Sigma) and the stock solution was diluted with the internal (patch-pipette) solution to a final concentration of 200–300 μg/ml just before use. A tight seal (>2 GΩ) was formed between the electrode tip and the cell surface, which was followed by a transition from on-cell to whole-cell recording mode due to partitioning of amphotericin B into the membrane underlying the patch. After formation of the whole-cell configuration, access resistance lower than 60 MΩ was considered acceptable and typically was between 20–30 MΩ during perforated recordings. The series resistance was not compensated in this study. Cellular membrane potentials or currents were measured by a patch-clamp amplifier (200B; Axon Instruments). Data were filtered at 5 kHz, acquired at 11 kHz, digitized on-line (Axon Instruments Digidata 1322 series A/D board), and stored on a computer for later off-line analysis (pClamp V9; Axon Instruments). A U-tube system enabling fast application and removal of agonists/antagonists was employed to assess responses to glutamate and GABA. Both passive and active membrane properties were examined. The cells were typically voltage-clamped at −50 mV and depolarizing or hyperpolarizing command voltages were applied. In some cases, recorded cells were photodocumented and subsequently localized and characterized for neuronal and other phenotypes by immunocytochemistry. Origin (Microcal Software, Inc., Northhampton, MA) was used to plot waveforms. Samples sizes reported refer to numbers of cells.

Statistics

Unpaired t-tests and one-way anova were used for comparisons of case characteristics and neuronal differentiation (GraphPad Prism 5.0 software). Values are mean ± SEM. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. For the exact p values, see respective figures.

Results

GFAP architecture of the SVZ in elderly humans

The SVZ was qualitatively assessed in anterior, forty-micron, frontal sections for GFAPδ and CD74 immunoreactivity in 23 elderly cases. These cases are different from those used for cell culture (see Materials and Methods). We examined only the anterior SVZ, because this region is distinctly richer in neural stem/progenitor cells in the human brain (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006). Some cases were also immunostained for microglia (anti-HLA-DR).

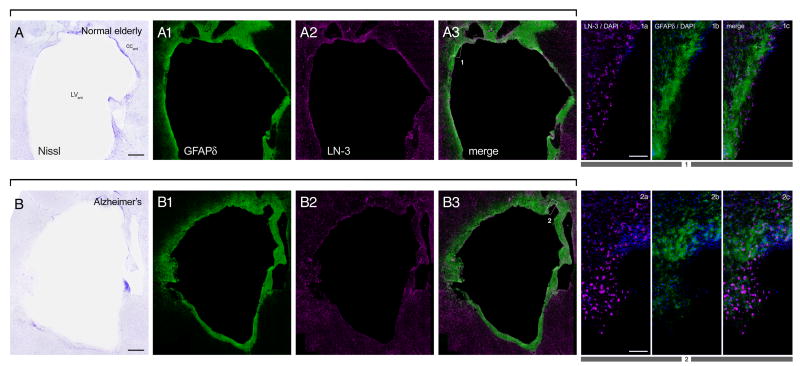

Frontal sections of the anterior periventricular white matter/SVZ from elderly human autopsy cases, regardless of diagnosis, exhibited a GFAPδ-immunoreactive astrocyte ribbon (Fig. 2) that is separated from the ependyma by a 50–100 μm hypocellular gap (cf. Fig. 1B). We also observed abundant HLA-DR-immunoreactive microglia in the SVZ of all disease groups (Fig. 2A2, B2), a cell type not previously reported to be a constituent of the human SVZ (c.f. Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006).

Fig. 2. Similar SVZ cellular architecture in Alzheimer’s disease and elderly control subjects.

Low magnification (A, A1–A3; B, B1–B3) montages and high magnification (1a–1c; 2a–2c) photomicrographs of Nissl and immunostained frontal sections of the lateral ventricle anterior to the caudate nucleus obtained from a normal elderly control subject (A) and an Alzheimer’s disease subject (B). GFAPδ immunoreactivity shows distribution of astrocytes, and LN-3 immunoreactivity (anti-HLA-DR) shows distribution of microglia. Boxes in low-magnification merge panels show where high-magnifications images were taken. DAPI counterstain (blue) in high magnification panels shows cell nuclei. In this figure and in all subsequent ones, red-green fluorescence was converted to magenta-green (see Materials and Methods). Portions of the ependymal layer were often denuded in all elderly cases. Panels in A from a 92 year-old control case with microscopic changes of AD but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history; PMI 3 h. Panels in B from a 78 year-old AD case; PMI 4 h. Scale bars: 1 mm, low magnification; 100 μm high magnification. Abbreviations: LVant, anterior lateral ventricle; CCant, anterior corpus callosum.

Initial plating of SVZ samples for cell culture

Table 2 summarizes the postmortem cases from which tissue was obtained for the different in vitro experiments. Microglia in the initial SVZ cell suspensions were adherent within a few hours of plating, such that supernatants collected from the microglia cultures contained few or no detectable microglia. Rather, the microglia-depleted supernatants consisted of some cellular debris and individual phase-bright cells, the vast majority of which were initially immunoreactive for GFAP (Fig. 3) but not for markers of microglia. We had a sufficient number of AD, NND, and PD cases to statistically evaluate any differences in initial cell viability (cells/ml/g of source tissue). One day after initial plating, there were no reliable differences in viability of the stem/progenitor cell-rich supernatant as a function of age at expiration (r2 = 0.013; p=0.567), PMI (r2 = 0.030; p=0.385), or diagnosis category (Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 3.655 on AD (n=20) vs. NND (n=4) vs. PD (n=3); p = 0.161).

Table 2.

Characteristics of cases used for qualitative and quantitative in vitro assessments of stem/progenitor cells derived from elderly postmortem SVZ.

| Case | Diagnosis | age (yr)a |

Gender | PMI (h)b | Neuro- spheres observedc |

Mitogen expansiond |

Prolifer- ation / stem cell ICCe |

Cell type ICCf |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

—In vitro Morphological and Electrophysiological Assessments— | |||||||||

| 1 | AD | 96 | F | 3.00 | √ | nestin, KI-67 | βTub, SMI311, GFAP, LN3, GC, map 2 | ||

| 2 | AD | 96 | F | 1.66 | √ | nestin, KI-67, Musashi-1, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GC, map 2 | ||

| 3 | AD | 69 | M | 2.75 | √ | nestin, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GFAPδ, GC, SMI311, | ||

| 4 | AD | 72 | M | 4.16 | √ | — | βTub, SMI311 | ||

| 5 | AD | 91 | F | 3.50 | √ | — | βTub, SMI311, map 2 | ||

| 6 | AD | 80 | M | 5.00 | √ | — | — | ||

| 7 | AD | 91 | F | 2.50 | √ | √ | nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GFAPδ | |

| 8 | AD | 69 | M | 2.50 | √ | √ | nestin, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GFAPδ | |

| 9 | AD | 84 | F | 3.00 | √ | √ | nestin | GFAP, LN3 | |

| 10 | AD | 89 | F | 3.50 | √ | √ | nestin, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP | |

| 11 | AD | 96 | F | 4.00 | √ | √ | nestin, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP | |

| 12 | AD | 92 | M | 2.00 | √ | — | — | ||

| 13 | AD | 82 | F | 2.50 | √ | — | — | ||

| 14 | AD | 90 | F | 2.45 | √ | — | βTub, GFAPδ | ||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 85.50 | 3.04 | |||||||

| SEM | 2.61 | 0.24 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | Controli | 90 | F | 4.00 | √ | — | βTub, GFAP, | ||

| 2 | Control | 75 | M | 4.33 | √ | nestin | βTub, GFAP | ||

| 3 | Control | 96 | F | 2.16 | √ | — | βTub, GFAP, GC, SMI311 | ||

| 4 | Control | 88 | M | 3.75 | √ | nestin, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GFAPδ, GC, map 2 | ||

| 5 | Control | 88 | F | 4.50 | √ | Musashi-1, nucleostemin | βTub, GFAP, GFAPδ, | ||

| 6 | Control | 77 | F | 3.00 | √ | √ | — | βTub, GFAP | |

| 7 | Control | 85 | M | 3.50 | √ | √ | — | — | |

| 8 | Control | 87 | F | 2.00 | √ | — | — | ||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 85.75 | 3.41 | |||||||

| SEM | 2.42 | 0.33 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | NNDj | 97 | M | 1.5 | √ | Musashi-1, nestin | βTub, GFAPδ, map 2 | ||

| 2 | NND | 75 | F | 2.75 | √ | — | — | ||

| 3 | NND | 86 | M | 4.75 | √ | — | βTub, GFAPδ | ||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 86.00 | 3.00 | |||||||

| SEM | 6.35 | 0.95 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | PDk/AD | 79 | M | 2.50 | √ | √ | nestin, nucleostemin, Musashi-1 | βTub, GFAP, LN3, GC, | |

| 2 | PD | 87 | F | 2.16 | √ | √ | — | βTub, GFAPδ | |

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 83.00 | 2.33 | |||||||

| SEM | 4.00 | 0.17 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | PSPl | 82 | F | 2.33 | √ | nestin | GFAP, GC, SMI311, map 2 | ||

| 2 | PSP/AD | 81 | F | 2.00 | √ | — | GFAP, GC, SMI311 | ||

| 3 | PSP | 94 | F | 2.50 | √ | — | — | ||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 83.00 | 2.33 | |||||||

| SEM | 4.00 | 0.17 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | DLBm | 87 | M | 3.75 | √ | √ | — | — | |

| 2 | DLB | 77 | M | 3.50 | √ | — | — | ||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 82.00 | 3.63 | |||||||

| SEM | 5.00 | 0.13 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | Argyrophilic grain disease (dementia) | 90 | F | 2.50 | √ | nestin | βTub, GFAP | ||

| 2 | Frontotemporal lobar degeneration | 56 | F | 3.00 | √ | nestin | GFAP, GC, SMI311 | ||

|

—In vitro Quantitative Assessment of Differentiation— | |||||||||

| 1 | AD | 87 | F | 3.00 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 2 | AD | 90 | M | 3.16 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 3 | AD | 81 | M | 2.50 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 4 | AD | 83 | M | 2.83 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 5 | AD | 79 | M | 2.66 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 6 | AD | 85 | M | 3.50 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 7 | AD | 87 | M | 2.50 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 83.14 | 2.88 | |||||||

| SEM | 5.00 | 0.14 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | Control | 90 | M | 3.66 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

| 2 | NND | 91 | M | 2.00 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ | |||

|

| |||||||||

| MEAN | 90.50 | 2.83 | |||||||

| SEM | 0.5 | 0.83 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | PD/demn | 69 | M | 4.16 | √ | βTub, GFAPδ, GFAP | |||

age at expiration

postmortem interval

cases in which neurospheres developed in maintenance medium without explicit addition of mitogens

cases used for directed neurosphere expansion by EGF/FGF application

cases from which neurospheres were subcultured and assessed immunocytochemically (ICC) for the presence of stem cell and/or cell proliferation markers

cases from which neurospheres were subcultured, differentiated, and assessed immunocytochemically for the presence of markers for neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes (see Table 1 for antibody information)

cases from which neurospheres were subcultured, differentiated, and cells assessed for neuronal-associated Na+, K+, and Ih currents, and responses to GABA and glutamate using patch-clamp recording

cases used to assess the capacity of long-term maintained neurospheres to differentiate into neurons and astrocytes

microscopic changes of Alzheimer’s disease but insufficient for diagnosis (criteria not met for NIA-R AD designation)

neurologically normal for age

Parkinson’s disease

progressive supranuclear palsy

dementia with Lewy bodies

Parkinson’s disease with clinical history of dementia

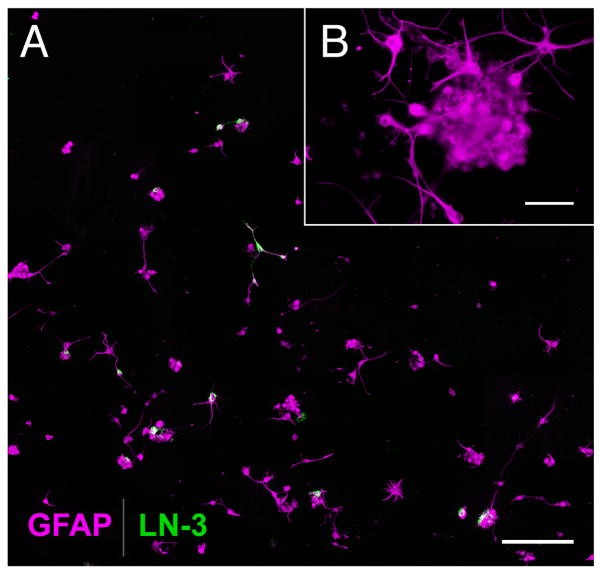

Fig. 3.

(A) Early-stage SVZ cultures are depleted of microglia and enriched with astrocytes. Relatively pure astrocyte-progenitor cultures were produced by first allowing microglia in the initial SVZ cell suspension to become adherent, then replating the remaining, non-adherent cells into a new flask, as shown here. These secondary flasks were therefore relatively depleted of microglia, as shown by the near absence of immunoreactivity for HLA-DR (green), a microglial marker. By contrast, nearly all the cells at this early stage of culture were immunoreactive for the astrocyte marker, GFAP (magenta). B shows a small GFAP-immunoreactive cluster of cells from the same culture reminiscent of an early-stage neurosphere. From an 89-year-old AD case; PMI 3.5 h. Scale bars: 250 μm; inset, 50 μm.

Development of neurospheres in SVZ cultures

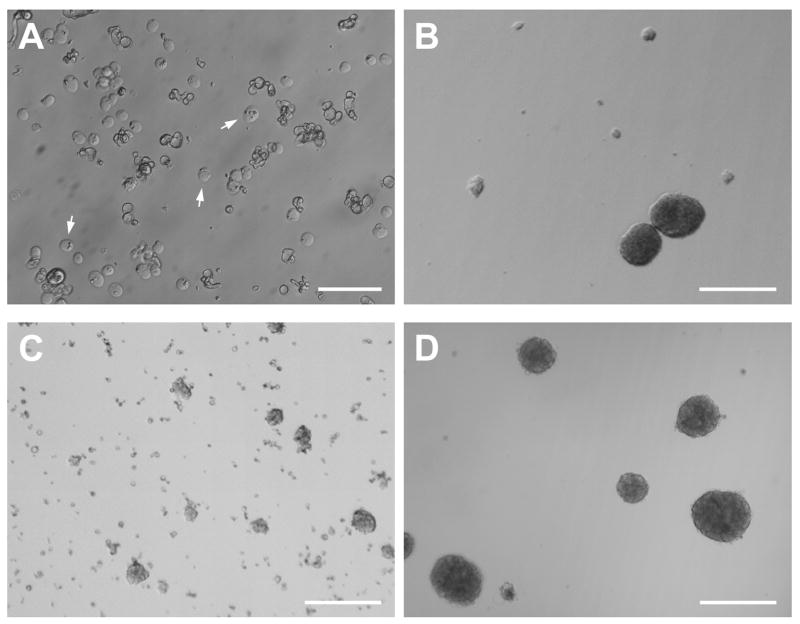

Thirty-four out of 37 seven cases attempted were successful in producing viable cultures. Tissue from two AD cases and one case with idiopathic late-onset cerebellar cortical degeneration failed to produce neurospheres in culture after one month. These cases did not differ remarkably from successful cases in terms of age (93, 79, 82 years) or PMI (3.0, 3.92, 3 h, respectively). For all other cases, approximately 5–14 days after plating, cultures from microglia-depleted SVZ supernatants began to exhibit small spherical aggregates of adherent and free-floating cells, some of which eventually bore the characteristic morphology of mature neurospheres (Fig. 4A). After several weeks in culture, adherence and increasing numbers of neurosphere-like clusters were noted (Fig. 4B), with densities ranging from as few as 11 putative neurospheres/2.5 mm2 at initial time points to as many as 33 such clusters/2.5 mm2 4–8 weeks later. Sizes of the putative neurospheres also increased with time, from approximately 15–20 μm diameters at initial time points to around 250 μm several weeks later. Diameters greater than 250 μm, however, were rare even after several months in culture, and some small neurospheres (~50 μm diameter) were always observed at later time points.

Fig. 4.

Morphology of neurospheres derived from human elderly autopsies of the SVZ. Microglia-depleted SVZ supernatants developed spherical aggregates of free-floating cells, some of which bore the characteristic morphology of neurospheres. (A) Phase-contrast micrograph of neurospheres and cell aggregates in suspension, shown here seven days after initial culturing. From a 69-year-old AD case; PMI 2.5 h. (B) Neurospheres from the same case as in A on the third passage. (C) Within hours of plating on laminin or poly-L-lysine substrates, adherent, neurosphere-like clusters of cells were observed with many fine processes and cells radiating outward, shown here at 2 weeks post-plating. From an 84-year-old AD case; PMI 3.0 h. Scale bars: A, B, 100 μm; C, 250 μm.

In addition to adherence to flask surfaces, adherence and development of neurosphere-like clusters appeared to be facilitated by the concurrent adherence of phase-dark, GFAP-immunoreactive cells with relatively large somas (50–70 μm) and other morphologic characteristics of type 1 astrocytes (Fig. 5A, 5B) (Raff et al., 1983). In confluent cultures, these cells typically surrounded or provided a bed for neurosphere-like cell aggregates, as well as more loosely organized groups of bipolar and multipolar phase-bright cells (Fig. 5C, 5D). In such cases, the phase-bright cells extended many fine processes that appeared to contact the protoplasmic astrocyte soma, sometimes spanning several hundred micrometers to do so (Fig. 5B). These findings are consistent with the supportive role widely ascribed to astrocytes in other culture studies (e.g. Song et al., 2002; Svendsen et al., 1998).

Fig. 5.

Association of neurospheres co-cultured with type 1 astrocytes. (A, B) Neurospheres and clusters of small, phase-bright cells were often observed attached to the surface of beds of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes having type 1 morphology (Raff et al., 1983). Arrowheads in B indicate possible contacts between clusters of putative progenitors and a type 1 astrocyte. (A, 96-year-old AD case; PMI 1.66 h; B, 88-year-old control case with microscopic changes of AD but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history; PMI 3.75 h. (C, D) In confluent cultures, these cells typically surrounded or provided a bed for neurosphere-like cell aggregates, as well as for more loosely organized groups of bipolar and multipolar phase-bright cells (C, 69-year-old AD case; PMI 2.75 h; D, 84-year-old AD case; PMI 3.0 h). Scale bars: A, B, 100 μm; C, D; 250 μm.

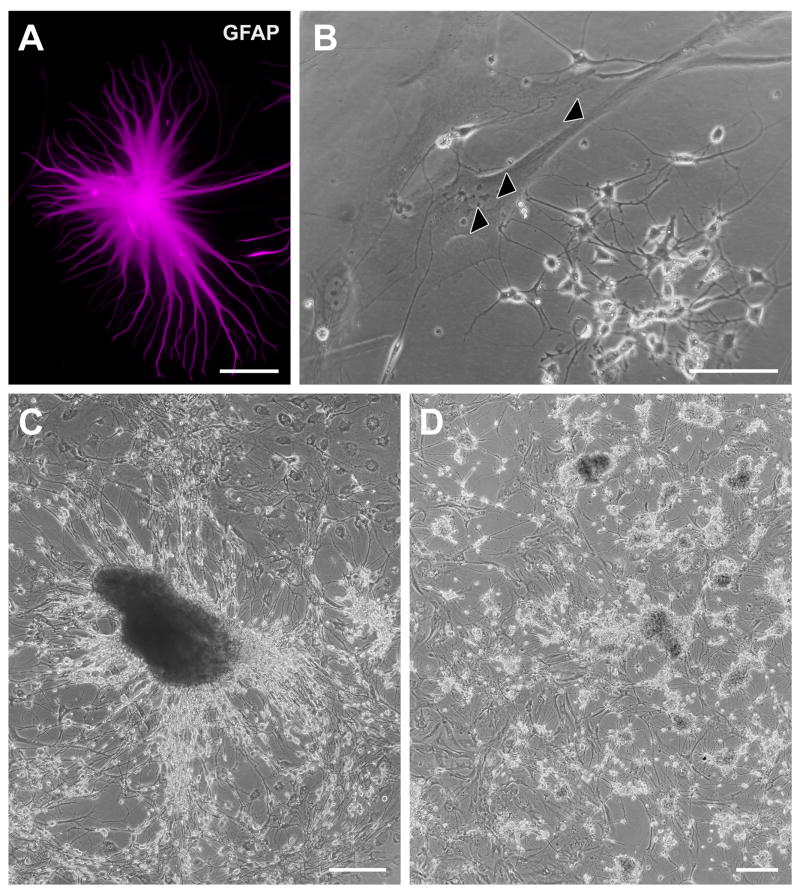

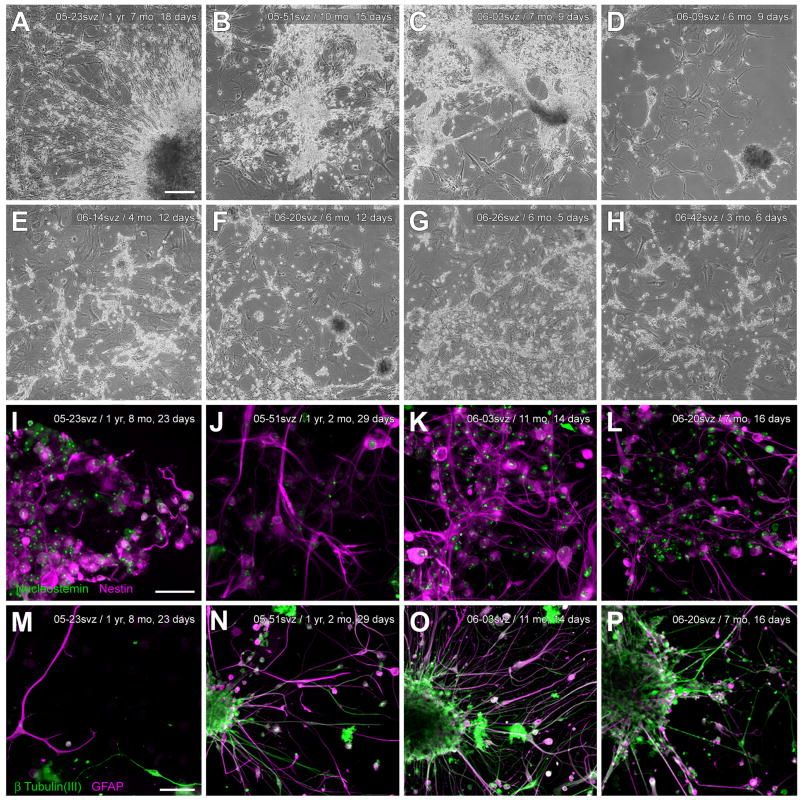

Neurosphere-like growth was manifest without application of specific exogenous growth—factors only complete DMEM containing 10% FBS was employed. However, by applying the mitogens hEGF and hFGF-b to microglia-depleted SVZ single-cell suspensions in serum-free medium (SFM), cells initially became adherent, expanded into spherical clusters over 1–3 weeks, and then released into free-floating spheres that continued to grow in diameter (Fig. 6A–D). Neurosphere diameters sometimes exceeded 400 μm, although some smaller diameter spheres were always present in subsequent passages. As with neurospheres co-cultured with type 1 astrocytes in serum-containing medium, mitogen-expanded neurospheres were obtained with SVZ material from neuropathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and normal non-demented cases.

Fig. 6.

Mitogen expansion of neurospheres derived from human elderly autopsies of the SVZ. (A) Microglia-depleted, SVZ single-cell suspensions treated with hEGF (20 ng/ml) and hFGF-b (10 ng/ml) in serum-free medium (see Materials and Methods) adhere initially to the uncoated flask surface, shown here (arrows) at 15 h (91-year-old AD case; PMI 2.5 h). (Some cellular debris is also present). (B) Within 1–3 weeks of continued mitogen exposure, fewer adherent cell clusters and more free-floating neurospheres were observed in suspension (15 days exposure, same case and flask as in A). (C) At early time points (5 days exposure) shown here in a different case (84-year-old AD case; PMI 3.0 h) many clusters of cells are still adherent, and diameters and morphology of neurospheres in suspension vary widely. (D) With continued exposure to hEGF and hFGF-b, neurospheres were mainly in suspension and had more spherical morphology (~9 weeks exposure; same case as in C). In parallel cultures derived from cortical tissue and adjoining periventricular white matter that intentionally discarded the SVZ, we never observed neurospheres develop with this mitogen expansion protocol, nor develop spontaneously in DMEM complete. Scale bars: A, 50 μm; B, C, D; 250 μm.

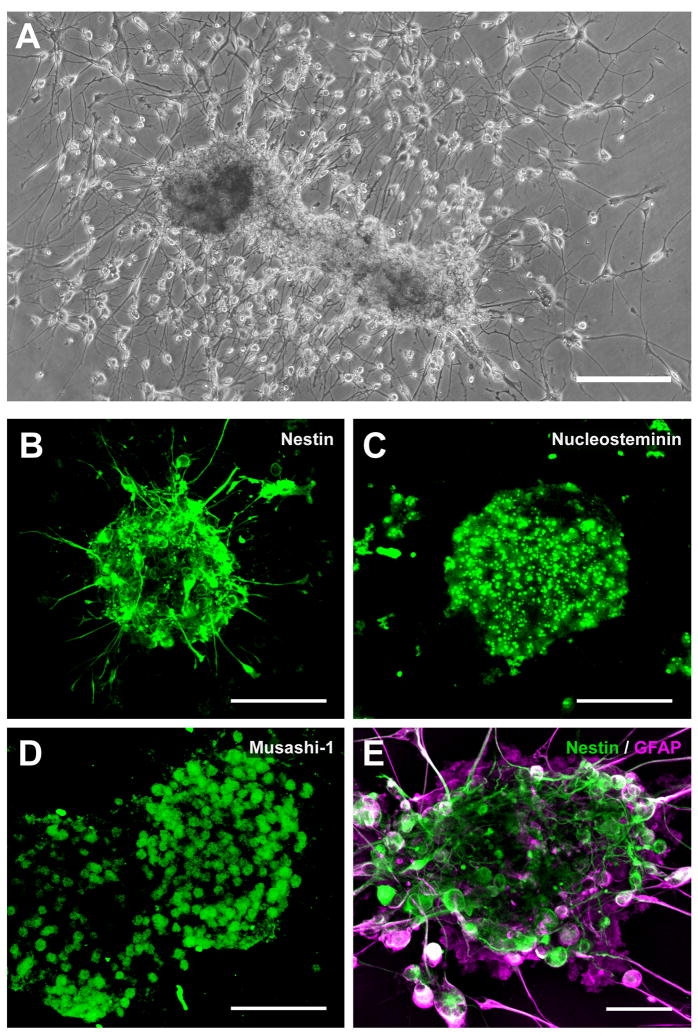

With unstimulated SVZ cultures, culture medium containing neurosphere-like clusters in suspension could be passaged repeatedly from the original flask or from subsequent daughter flasks, with each passage resulting in cluster adherence of a proportion of the neurospheres (Fig. 7A). For mitogen-stimulated cultures maintained in SFM, most neurospheres remained in suspension (cf. Fig. 6B, 6D), and could be passaged as such, until plated on a suitable substrate. As in previous studies (e.g. Feldman et al., 1996; Laywell et al., 2002; Song et al., 2002), PLL/laminin appeared to be a favorable substrate for these processes, quickening differentiation and ultimately yielding more highly complex networks of cells and processes. In particular, when grown on PLL/laminin substrates, neurospheres became adherent and exhibited clear signs of differentiation within 24 h, extending, over the next 3 days, fine processes that radiated outward (Fig. 7A, 7B). Adherent clusters tended to grow larger than non-adherent clusters. The aggregated cells exhibited a core that was immunoreactive for neural stem cell proteins, including nestin (Fig. 7B); nucleostemin (Fig. 7C); and Musashi-1 (Fig. 7D). GFAP-immunoreactive cells were often at the periphery of neurospheres, both at early and later stages of differentiation (Fig. 7E). On the basis of these properties, all of which have been used to identify neurospheres in rodent and human biopsy SVZ cultures (Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo, 2002; Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996; Doetsch et al., 1999; Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993; Moe et al., 2005b; Morshead et al., 1998; Sanai et al., 2004), we concluded that the adherent clusters of cells from human autopsied SVZ met criteria for neurospheres and/or neuronal progenitor cells, and they are so designated hereafter in this report.

Fig. 7.

Neurospheres produced from human elderly SVZ are immunoreactive for neural stem cell proteins. (A) Within 2 weeks of plating on uncoated surfaces, adherent, neurosphere-like clusters of cells were observed with many fine processes and cells radiating outward. From an 84-year-old AD case; PMI 3.0 h. (B, C, D) Confocal micrographs of neurospheres immunoreactive for neural stem cell markers. Plating on PLL/laminin quickened the development and complexity of processes, as shown previously. SVZ neurospheres were expanded from a single-cell suspension for ~4.5 weeks in SFM with EGF/FGF, plated for one day on PLL/laminin to allow adherence, then fixed and immunostained for the neural stem cell proteins nestin, nucleostemin, and Musashi-1. From a 79-year-old Parkinson’s disease case who also had AD; PMI 2.5 h. Deletion of the primary antibodies resulted in no specific immunostaining. (E) Confocal micrograph of a neurosphere 2 weeks after plating, showing nestin-immunoreactive core (green) and differentiating GFAP-immunoreactive cells (red) at the periphery (same case and culture as in A). Scale bars: A, 250 μm; B, C, D, 100 μm; E, 50 μm.

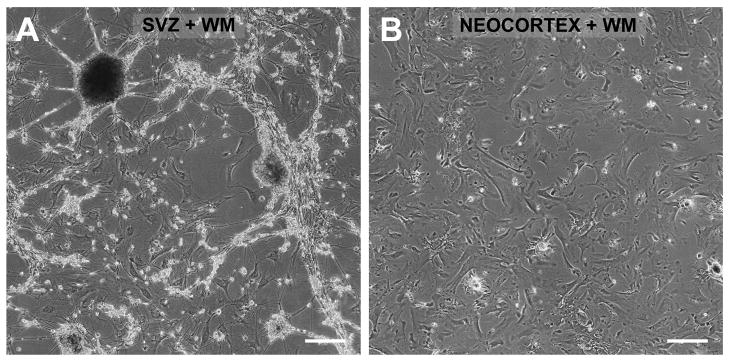

Notably, neurospheres were never observed in parallel, mitogen-stimulated or unstimulated cultures of neocortex from the same cases when the samples included deep subcortical white matter but specifically excluded the SVZ (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Neurospheres develop only from human elderly autopsied periventricular white matter (WM) that includes the SVZ. Cultures were produced and maintained in parallel using postmortem tissue from the same case (69-year-old AD case; PMI 2.5 h) that contained either (A) periventricular WM and adjoining SVZ (cf. Fig 1A) or (B) frontal cortex and adjoining subcortical WM excluding the SVZ. Microglia were depleted as before (see Materials and Methods). Neurospheres growing on top of putative astrocytes were observed only in cultures derived from SVZ+WM; only astrocytes developed in cultures derived from neocortex+WM. Images taken 28 weeks after plating. Scale bars: A, B, 250 μm.

Differentiation into specific brain cell types

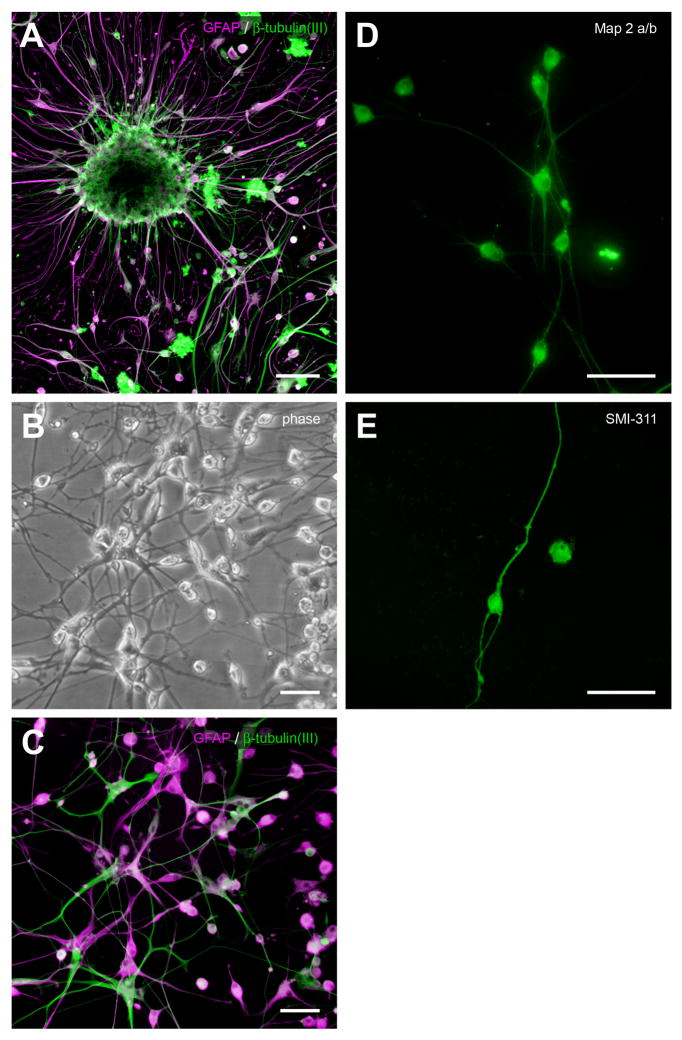

As noted, passaged neurospheres exhibited clear signs of differentiation within 24 h of adherence, extending, over the next 3 days, fine processes that radiated outward. At this time, many cells appeared to migrate away from the cluster of nestin and nucleostemin immunoreactive progenitor cells at the core of the neurosphere (Fig. 7E, Fig. 9A). Based on morphologic, eletrophysiologic, and antigenic criteria, these cells consisted of three distinct phenotypes: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes.

Fig. 9.

Development of neuron-like cells from elderly SVZ neurospheres. (A) When neurospheres were transferred to poly-L-lysine/laminin substrates and subcultured, they became adherent within 24 h, and cells with a more differentiated, bi- or multi-polar morphology began to appear at the neurosphere periphery, shown here about 2 weeks postplating. Confocal micrograph showing neurosphere immunostained for GFAP (red) and β-tubulin(III) (green) (88-year-old control case with microscopic changes of AD but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history; PMI 3.75 h). (B) Phase-contrast photomicrograph of differentiated cells about 200 μm away from a different neurosphere that was plated after the 18 weeks growing in culture, shown here at two weeks after subculturing (84-year-old AD case; PMI 3.0 h). (C) Epifluorescent photomicrograph of the same subculture and field, immunostained for β-tubulin(III) and GFAP. (D, E) Epifluorescent photomicrographs of putative neurons differentiated from elderly SVZ neurospheres that were immunoreactive for MAP2a/b and SMI-311, the latter a pan-neuronal neurofilament marker (D, same case as A, different subculture; E, 82-year-old progressive supranuclear palsy case; PMI 2.33 h). Scale bars: A, 100 μm; B–E, 50 μm; F, 25 μm.

Neurons

Putative neurons were phase bright, with bipolar and multipolar morphologies, relatively small somas less than 20 μm, and very complex processes (Fig. 9B). They were immunoreactive for neuron-specific markers such as β-tubulin (III) (Fig. 9C), MAP2a/b (Fig. 9D), and SMI-311 (Fig. 9E).

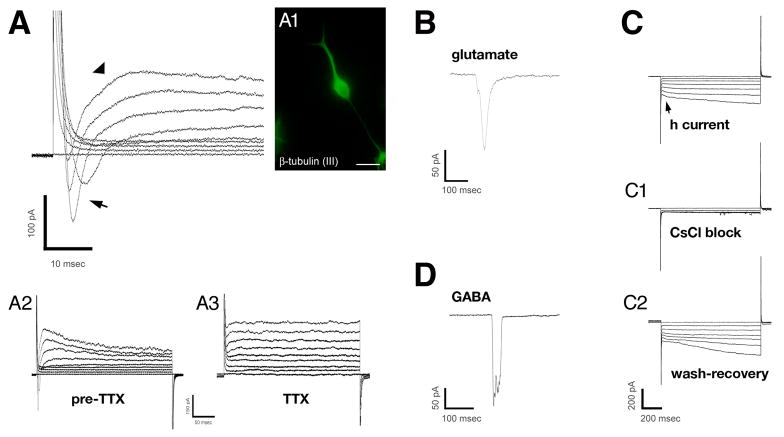

Patch-clamp electrophysiology supported the characterization of β-tubulin (III)-immunopositive cells as immature neurons (c.f. Moe et al., 2005a). Selection of cells for recording was initially based on morphologic characteristics (i.e., phase bright, small soma, bi-or multipolar), with subsequent immunocytochemical confirmation in some cases. Cells exhibiting neuronal morphology and immunoreactivity (Fig. 10A) had resting membrane potentials of −61.13 ± 1.60 mV (N=24 cells), and a wide range of electrophysiologic responses characteristic of neurons. These included fast activating and inactivating voltage-dependent, inward currents and slowly activating and inactivating outward currents (Fig. 10A). The fast, voltage-dependent, inward current was abolished by 1 μM tetrodotoxin (Fig. 10A3), suggesting the presence of classical TTX-sensitive, neuronal Na+ channels. Responses to exogenously applied glutamate (1 mM) and GABA (100 μM) were also observed in the putative neurons (Fig. 10B, 10D). In addition, under voltage-clamp mode, the hyperpolarizing voltage step-induced current (h-current) (Maccaferri et al., 1993) was observed in some cells (Fig. 10C). The h current was, on average, activated at −47.27 ± 1.60 mV (N = 11), and was blocked by the K+ channel blocker CsCl (1 mM) (Fig. 10C1). Although all these membrane potentials and responses are fully characteristic of neurons, no recorded cell exhibited spontaneous or depolarizing voltage-driven action potentials, suggesting that the neurons were not yet fully mature.

Fig. 10.

Electrophysiology of putative neurons differentiated from elderly human SVZ neurospheres. Patch-clamp recordings made in putative neurons differentiated from neurospheres derived from elderly, postmortem SVZ. (A) Example voltage-clamp records from a β-tubulin (III)-positive cell (A1) showing transmembrane currents in response to increasing voltage steps. Fast, voltage-dependent inward current (arrow) and slowly activating/inactivating outward current (arrowhead) were observed. Lower traces (A2, A3) show that the inward current was abolished by 1 μM TTX, suggestive of neuronal Na+ channels (upper extreme of traces are truncated for display purposes); the outward current, presumably carried by K+ ions was left intact (holding potential = −50 mV) (88-year-old control case with microscopic changes of AD but insufficient for diagnosis of AD due to a lack of dementia in their clinical history; PMI 3.75 h). (B) Responses of other putative neurons to glutamate (1 mM) (same case and subculture as in A, different cell) and GABA (100 μM) (90-year-oldcase diagnosed as argyrophilic grain disease (with clinical dementia); PMI 2.5 h). (C) Other putative neurons displayed an inward-rectified current (arrow) that was activated at hyperpolarizing membrane potentials and was blocked by CsCl (1 mM), suggesting the h current. From a 69-year-old AD case; PMI 2.75 h. Scale bar: A1, immunofluorescent image, 25 μm.

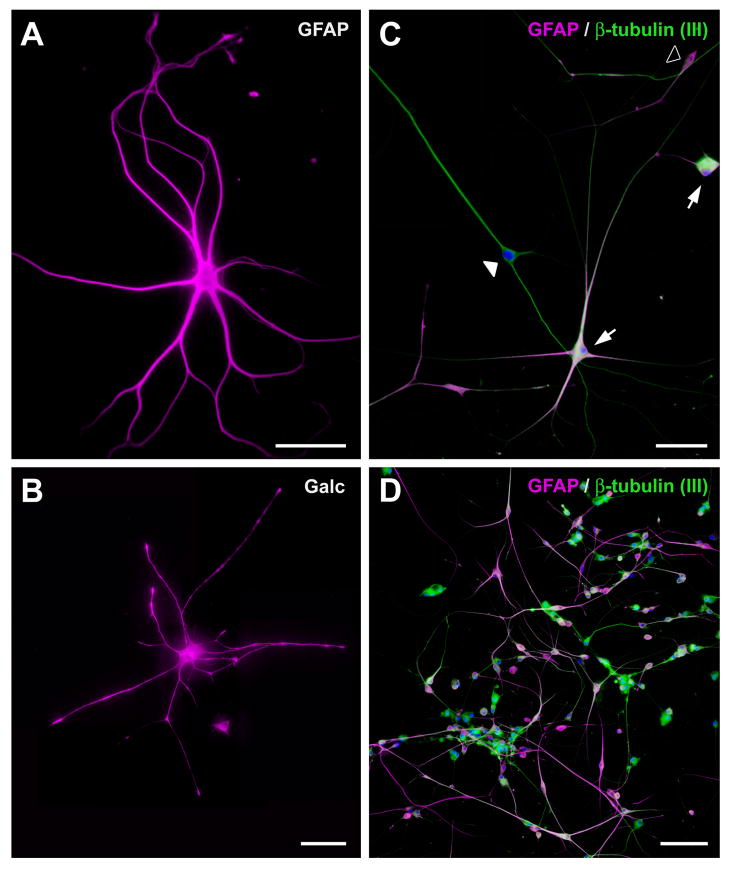

Non-neuronal and hybrid cells

GFAP-immunoreactive cells constituted a second cell type found distal to neurosphere cores (Fig. 11A). The most common had the multipolar stellate morphology and size of type 2 astrocytes (Raff et al., 1983) (Fig. 11A). However, as previously noted, phase-dark, GFAP-immunoreactive cells with relatively large somas (50–70 μm) and other morphologic characteristics of type 1 astrocytes were also observed (cf. Fig. 5).

Fig. 11.

Development of non-neuronal and hybrid cells in human SVZ cultures. (A) The most common type of cell that developed from SVZ neurospheres was the type 2 astrocyte, immunoreactive for GFAP (96-year-old AD; PMI 1.66 h). (B) Much less common were galactocerebroside-immunopositive (Galc) cells with oligodendrocyte morphology (same case as in A, different subculture). (C) As reported in rodent SVZ cultures (Laywell et al., 2005), a hybrid cell, the “asteron,” was also observed in human elderly SVZ cultures. These cells were immunoreactive for both the astrocyte marker GFAP (magenta) and the neuron-specific markerβ-tubulin (III) (green; DAPI counterstain). Note that with the GFAP and β-tubulin (III) double label, some cells, putative neurons, are labeled only with β-tubulin (III) (filled arrowhead); some cells, putative astrocytes, are labeled only with GFAP (open arrowhead); and some cells, asterons, distinctly show both markers (filled arrows). Such a finding in the same culture suggests that the failure of GFAP to stain putative neurons or, conversely, the failure of neuronal markers to stain putative astrocytes in samples double-labeled with both antibodies was not due, here or in the previous figures, to inadequate immunocytochemical methods with one or the other set of antibodies. From a 69-year-old Parkinson’s disease case; PMI 4.16 h. (D) Asterons often appeared to surround clusters of neurons (same case and subculture as in C). Scale bars: A, B, C, 50 μm; D, 100 μm.

Interestingly, in every SVZ culture that was immunostained for both astrocyte and neuronal markers, we observed some cells that colocalized both markers. (Fig. 11C). Although the numbers of these cells were not quantified, both bipolar and multipolar cells were observed. The pattern of staining shown in Fig. 11D is representative of all cases of different disease categories. First reported in murine SVZ cultures (Laywell et al., 2005), these so-called asterons have been suggested to represent a transdifferentiated state between the neuron and the astrocyte.

A third cell type encountered in neurosphere cultures was a cell immunoreactive for galactocerebroside (Fig. 11B). Unlike the other cell types, galactocerebroside-immunopositive cells with oligodendrocyte morphology were relatively rare, but could occasionally be observed when neurospheres were disaggregated from primary cultures and plated on PLL/laminin.

Quantitation of neuronal differentiation