Abstract

Estrogen receptor (ER)-mediated effects have been associated with the modulation of myocardial hypertrophy in animal models and in humans, but the regulation of ER expression in the human heart has not yet been analyzed. In various cell lines and tissues, multiple human estrogen receptor α (hERα) mRNA isoforms are transcribed from distinct promoters and differ in their 5′-untranslated regions. Using PCR-based strategies, we show that in the human heart the ERα mRNA is transcribed from multiple promoters, namely, A, B, C, and F, of which the F-promoter is most frequently used variant. Transient transfection reporter assays in a human cardiac myocyte cell line (AC16) with F-promoter deletion constructs demonstrated a negative regulatory region within this promoter. Site-directed mutagenesis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays indicated that NF-κB binds to this region. An inhibition of NF-κB activity by parthenolide significantly increased the transcriptional activity of the F-promoter. Increasing NF-κB expression by tumor necrosis factor-α reduced the expression of ERα, indicating that the NF-κB pathway inhibits expression of ERα in human cardiomyocytes. Finally, 17β-estradiol induced the transcriptional activity of hERα promoters A, B, C, and F. In conclusion, inflammatory stimuli suppress hERα expression via activation and subsequent binding of NF-κB to the ERα F-promoter, and 17β-estradiol/hERα may antagonize the inhibitory effect of NF-κB. This suggests interplay between estrogen/estrogen receptors and the pro-hypertrophic and inflammatory responses to NF-κB.

Estrogens play an important role in mammal normal physiological functions and also in the pathology of several diseases (1). One important target organ for estrogen action is the cardiovascular system. Estrogen exerts its effects mainly through its cognate receptors, estrogen receptor α (ERα)3 and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand activated transcription factors (2). ERs have been identified in both vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells of blood vessel walls as well as in cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes, in humans, and rodents (3–8). These receptors have been found to mediate the effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) on the cardiovascular system, e.g. rapid vasodilatation, reduction of vessel walls responses to injury, decreasing the development of atherosclerosis, and preventing apoptosis in cardiac myocytes in heart failure (9–11). Our recent studies in patients with aortic stenosis and dilated cardiomyopathy showed that the expression of the ERα gene is regulated in a disease-dependent manner (5, 7). However, the mechanisms involved in the regulation of ERα gene expression in the human myocardium have not been addressed to date.

ERα expression has been detected in several tissues with considerably different expression levels among these tissues (12). The transcription of the ERα gene plays an important role in regulating the expression of ERα in a cell- and tissue-specific manner (13–16). The human ERα mRNA is transcribed from at least seven different promoters with unique 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTRs) (A, B, C, D, E, F, and T) (17, 18). All these ERα transcripts initiate at cap sites upstream of exon 1 and utilize a splice acceptor site at nucleotide +163 in the originally identified exon 1 (19). These multiple promoters are utilized in a cell and tissue type-specific manner (20). For example the predominant promoter variants utilized for the expression of the ERα gene are A and C promoters in the endometrium, C and F promoters in ovaries, and only F promoter variant in osteoblasts (12, 21). In addition to the differential promoter usage, it appears that there are a variety of cell/tissue-specific factors that interact with these various ERα promoters with trans-activating (AP1, ERBF-1, AP2) or trans-repressing functions, which also affect the regulation of the transcription of the ERα gene in a cell- and tissue- specific manner (22–24). Furthermore, it has been shown that E2 differentially regulates the levels of ERα in a cell type- and tissue type-specific manner. Although E2 down-regulates the level of ERα gene expression in MCF7 cells, it leads to an increase of ERα mRNA levels in other cell lines such as FEM-19 and ZR-75 and in tissues such as liver (12, 25, 26). These findings suggested that the differential regulation of ERα gene expression by E2 in part is due to different promoter usage and/or transcription factors present within a cell (12, 26).

To understand the molecular mechanisms controlling ERα gene expression in the human heart, we first report the characterization of the ERα promoter variants in the human left ventricular (LV) tissue and subsequently examine the molecular mechanism involved in the regulation of the most frequently utilized promoter variant. Finally, we study the effect of E2 and ERα itself on the transcriptional activity of the identified human ERα promoters.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissues and RNA Extraction

Human LV myocardial samples used in this study were composed of tissue samples of non-used donor hearts with originally normal systolic cardiac function, no history of cardiac disease, and normal postmortem histology. However, they did not qualify for transplantation at the time of organ harvesting because of functional reasons. All subjects were Caucasian. The study followed the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki. Total RNA from LV tissue of human hearts was isolated using the guanidinium isothiocyanate based method (RNAzolB, Friendswood) as previously described (5).

Determination of the 5′-UTRs of the Human Cardiac ERα Transcript

To determine the 5′-UTRs of the ERα transcript in the human myocardium, 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) was performed using a GenRacerTM kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The template for 5′-RACE was total RNA isolated from LV tissue of 5 human hearts (3 females and 2 males; age 55.8 ± 10.8). To increase the specificity and product yield of 5′-RACE, nested PCR was then performed using another internal gene-specific primer and geneRacer-nested primer. First strand synthesis of hERα cDNAs was carried out from isolated total RNA using a gene-specific primer, RV4 oligonucleotide, located in exon 2. Subsequently, for the amplification of cDNAs, we performed, first, hot-start PCR followed by nested PCR using the GenRacerTM 5′-primer and GenRacerTM 5′-nested primer as forward primer and the gene-specific primer RV1, RV2, RV3, and RV4 located in exon 1 or exon 2 of the ERα gene as the reverse primer (for primer sequences see supplemental Table 1). The PCR reactions were carried out under standard conditions. The 5′-RACE PCR products were subcloned into pCR®4-TOPO® vector using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) for subsequent DNA sequence analysis.

Reverse Transcriptase-PCR Analysis of 5′-UTRs

Total RNA isolated from 14 human LV samples (7 females and 7 males; age: 50.9 ± 12) was used as the template for reverse transcriptase-PCR. cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA from each sample using a random primer and a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit according to standard protocol (Applied Biosystems). PCRs were then carried out according to standard protocol using the following sense and antisense primers specific for each 5′-UTR variant of the hERα gene: A-variant, FW/RV; B-variant, FW/RV; C-variant, FW/RV; D-variant, FW/RV; E-variant, FW/RV; F-variant, FW/RV (for the primer sequences, see supplemental Table 1). The resulting PCR products were analyzed in 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Semiquantitative PCR Analysis

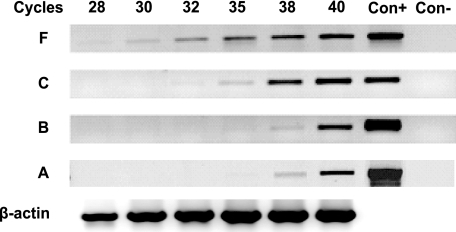

Semiquantitative PCR was performed on a cDNA pool generated from the RNA of the same 14 human LV samples using primers specific for 5′-UTR A-, B-, C-, and F-variants according to standard protocols. PCR reactions were stopped after 28, 30, 32, 35, 38, and 40 cycles of amplification. The amplification of human β-actin gene was used as a reference gene for semiquantitative comparison. Equal aliquots of each PCR reaction were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Cloning of the 5′-Flanking Regions of the hERα Gene and Construction of Reporter Plasmids

Human genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood samples from healthy volunteers (n = 3) by using QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To generate the reporter construct containing the 5′-flanking region of the hERα F-variant, the sequence of the 5′-UTR F-variant and a part of coding exon 1 of the hERα gene (from +55 to +359 bp, relative to transcription start site; accession number U68068/AJ002562) (17) was fused to the −1,218/+83-bp fragment of hERα promoter F sequence (from −118,358 to −117,140 bp; upstream of the originally described transcription start site (17)) using a splicing overlap extension method (SOE-PCR). The fragment +55/+359 bp, amplified with primer pairs FW-C1/RV-D1, was generated using human ERα cDNA as template, and the fragment −1218/+83 bp (relative to the transcription start site of F-variant), amplified with primer pairs FW-A1/RV-B1, was generated using human genomic DNA as template (see Fig. 1, also see supplemental Table 1). The primer RV-B1 was the reverse complement to the primer FW-C1. Amplified fragments were cloned into pCR®4-TOPO® and subsequently used as template for SOE-PCR amplification with primer pairs MluI site-linked FW-A1 and XhoI site-linked RV-D1. The resulting SOE-PCR fragment (referred herein and thereafter as full-length fragment F: −1218/+359 bp) was subcloned into a pCR®4-TOPO® vector using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). This sequence was then used as a template to prepare a series of deletion ERα F-variant DNA fragments (−910/+359 bp, −457/+359 bp, −910/−487 bp, and −910/−9 bp) by PCR (for primer binding sites see Fig. 1, FW-A6/RV-D1, FW-A5/RV-D1, FW-A6/RV-G4, FW-A6/RV-G1). Additionally, to generate reporter constructs containing the 5′-flanking region of hERα A-, hERα B-, and hERα C-transcript (−1019/+260 bp; −1303/−175 bp; −3215/−1859 bp respectively, relative to the originally identified transcription start site) (17), we performed PCR as described above (for the primer sequence see supplemental Table 1). The resulting sequences referred herein as to promoter variant A-, B-, and C- were then subcloned into the pCR®4-TOPO® vector. All constructs were verified by restriction site digestion and sequence analysis. Thereafter, luciferase reporter constructs were generated by using restriction sites MluI and XhoI; the resulting fragments were gel-purified and subcloned into promoterless pGl2-basic vector (Promega). The resulting luciferase reporter constructs are referred to as: A-promoter-pGL2, B-promoter-pGL2, C-promoter-pGL2, and F-promoter −pGL2. The different F-promoter constructs are as follows: −1218/+359-pGL2, −910/+359-pGL2, −457/+359-pGL2, −910/−487-pGL2, −910/−9-pGL2.

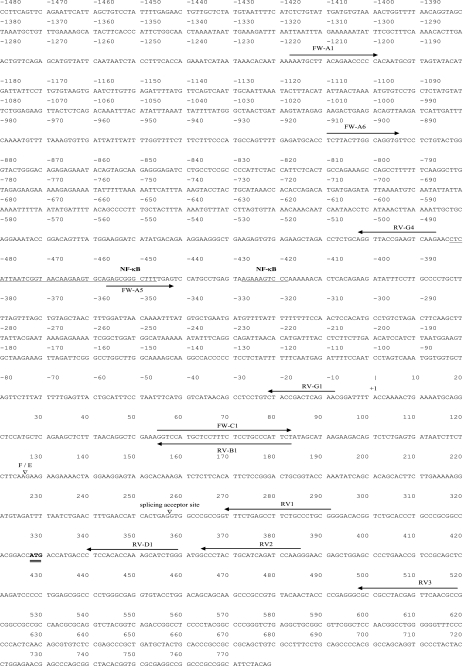

FIGURE 1.

Partial DNA sequence of the human ERα F-promoter with its 5′-UTR and the first coding exon. 5′-UTR variant F is directly spliced to the 5′-UTR variant E2. The splicing site of F and E exons (F/E) are indicated by an open triangle. The transcriptional start site is set as +1, and translation start site (ATG) is double-underlined. The location and name of the primers used for construction of luciferase reporter assays are shown by arrows. The region containing putative transcription factor binding site is underlined.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used for generating mutants of potential transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) binding sites within the hERα F-promoter. The −910/−9-pGL2 reporter construct was used as a wild type construct. PCR oligonucleotide primer pairs used for generating mutants are listed in supplemental Table 1. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing. Deletion constructs are referred to as M1 (−910/−9)-pGL2 and M2 (−910/−9)-pGL2.

Cell Culture, Treatment, and Transient Transfection Reporter Assays

AC16 cells (human cardiomyocyte cell line) (27) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 (InvitrogenTM) supplemented with 12.5% fetal bovine serum (PAA Laboratories), penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml, 100 μg/ml; PPA), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml, InvitrogenTM) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. For stimulation experiments with E2 (10−8 mol/liter, Sigma), cells were cultured in phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 supplemented with 2.5% charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum (CS-FBS, Biochrom AG), penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml, 100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. AC16 cells were treated with parthenolide (10 μmol/liter, Biomol) for 6 h and with ICI 182,780 (10−5 mol/liter, Tocris) 30 min before starting the E2 treatment. For stimulation experiments with TNFα, AC16 cells were cultured in normal medium with TNFα (10 ng/ml, R&D system) for 15 and 30 min.

For the transient expression analysis of hERα promoter constructs, ∼1.5 × 105 cells/well were plated onto 6-well plates. After 24 h of incubation, promoter-luciferase reporter construct (1 μg) and the internal reference Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid phRL-TK vector (10 ng, Promega) were transfected to each well using FuGENE® 6 reagent according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche Diagnostics). For co-transfection experiments, 1 μg of each pSG-hERα66 vector (HEGO-vector, kindly donated by Dr. P. Chambon) or appropriate empty vector was used. After treatments, cell extracts were prepared, and Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were sequentially measured using the Dual-GloTM-Luciferase assay system (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions in a multilabel counter Victor3TM (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Variations in transfection efficiency were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. All transfections were carried out in triplicate for each construct and performed independently at least three times. Transfection results were averaged and are expressed as the mean ± S.E.

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts

Nuclear proteins from cultured (stimulated or non-stimulated) AC16 cells were extracted from cells grown in 100-mm culture plates. The AC16 cell pellets were resuspended in Nonidet P-40 containing saccharose buffer (for all buffers see supplemental Table 2). After centrifugation, the pellet was gently resuspended in a low salt buffer before the same volume of high salt buffer was gradually added in small aliquots to the cells. Afterward, the samples were incubated for 45 min at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. After centrifugation, the supernatant (nuclear proteins) was collected and stored at −80 °C. The protein concentration of nuclear extracts was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

Immunoblotting

Five μg of nuclear protein or 50 μg of whole cell extract isolated from AC16 cells was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were immunoblotted overnight with antibodies against anti-NF-κB p50 (1:500; H-119, Santa Cruz) or anti-ERα (1:300, G-20, Sc-544; Santa Cruz) followed by incubation for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000, Dianova). Nuclear-specific protein TFIID (TBP, N-12, Santa Cruz) or anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (Chemicon) was used for normalization. Immunoreactive bands were visualized with a chemiluminescent detection kit (ECLTM, GE Healthcare), and the density of protein bands were quantified by Alpha Ease FCTM software (Version 3.1.2, Alpha Innotech Corp.).

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

AC16 cells were grown on eight-chamber culture slides (BD Bioscience) at a density of 30,000 cells/well. The cells were treated with or without NF-κB inhibitor, parthenolide (10 μmol/liter), for 6 h. Cells were fixed with 3% buffered formaldehyde (20 min), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 4 min), blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS (1 h), and then stained overnight with rabbit anti-NF-κB p50 polyclonal antibody (1:100, H-119, Santa Cruz) and mouse anti-ERα monoclonal antibody (1:50, ab2746, Abcam). Subsequently the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and Cy-3 conjugated goat F(ab′)2 Fragment anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h. The nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 10 min. Subsequently, slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium for fluorescence (H-1000, Vectashield, Vector Laboratories). Confocal images were acquired using a Leica TCS-SPE spectral laser scanning microscope, and images were processed by Leica Application Suite AF software (Version 1.8.0).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays and Supershift Assays

For electrophoretic mobility shift assays, 5 μg of nuclear extracts were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 2 μg poly(dI-dC) and 60,000 cpm radiolabeled oligonucleotide (5′-AACCTCATTAATCGGTAACAAGAAGTGCAGAGCGGGCT-3′, containing the putative binding site for NF-κB (Fig. 1), adjusted to 20 μl with a 5× binding buffer (for the buffer, see supplemental Table 2). For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotides were added in a 100-fold molar excess to the reaction mixture before the addition of radiolabeled probe. For supershift assays, increasing amounts of antibody against NF-κB p50 (H-119, Santa Cruz) was added 30 min at 4 °C before the addition of the 32P-labeled probe. Each reaction was loaded on a native 5% polyacrylamide gel and run at 150 V for ∼2 h. After electrophoresis, gels were dried, exposed to imaging plates at −20 °C for up to 1 week, and visualized by autoradiography and quantified using phosphorimaging (GE Healthcare).

Statistical Analysis

All graphic representations and statistical analysis were accomplished using SPSS Program for windows (Version 13; SPSS, Inc.). Statistical comparisons between unpaired groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. A p value <0.05 was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

ERα Gene Is Regulated by the F-promoter Variant in the Human Heart

To identify the alternative 5′-UTR usage in ERα transcripts in the human heart, we performed nested 5′-RACE, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Sequence analysis of 41 positive clones demonstrated that 85.4% of these clones contained the 5′-UTR F-variant, 12.2% contained the C-variant, and 2.4% contained the B-variant. The existence of these three alternatives 5′-UTRs points to the presence of three alternative promoters of ERα in the human heart. Furthermore, this experiment suggests that the F-variant is the predominant promoter form of the ERα gene in the human myocardium, as a majority of the 5′-RACE clones were initiated by the promoter variant F (herein designated as F-promoter). To confirm the results obtained from 5′-RACE, we measured the relative abundance of the ERα transcripts containing different variants of the 5′-UTR by semiquantitative PCR. As shown in Fig. 2, the F-transcript exhibited the greatest abundance followed by C, B, and A transcripts. Additionally, 5′-UTR-specific PCR revealed that the transcript variants A, B, C, and F were present in all LV samples (data not shown). The 5′-UTR variants D and E were not detected in any tested sample. These findings suggest that the F-promoter is the most frequently utilized promoter in the basal transcription of the ERα gene in the human myocardium.

FIGURE 2.

Expression levels of multiple ERα transcripts. The appearance of the PCR products was monitored at progressive cycles during the amplification (28, 30, 32, 35, 38, and 40 cycles). A PCR F-fragment appeared for F-fragment after 28 cycles of amplification (320 bp, marked with a F), for C-fragment after 32 cycles (162 bp, marked with a C), for B-fragment after 35 cycles (218 bp, marked with a B), and for A-fragment after 35 cycles (591 bp, marked with an A). Con+, cDNA from MCF-7 cells was used as the positive control (35 cycles for each ERα transcript); Con-, negative PCR control (without DNA). The β-actin gene (481 bp) was used as a reference gene.

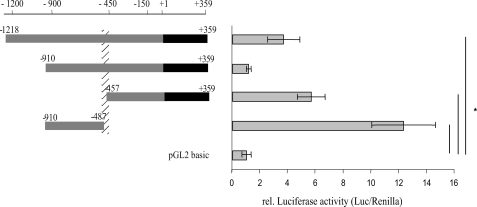

To identify the regulatory elements controlling the expression of the ERα gene in the human heart, the activity of 1.2-kilobase pair F-promoter (full-length) and the deletion F-promoter fragments were investigated by luciferase reporter assay in AC16 cells. The full-length luciferase reporter construct (−1218/+359-pGL2) showed ∼4-fold promoter activity in comparison with the promoterless construct pGl2-basic (Fig. 3). Deletion of the region from −1218 to −911 bp to yield −910/+359-pGL2 decreased the promoter activity. These findings suggest that the region from −1218 to −910 bp contains an enhancer element(s) and/or the region from −910 to +359 bp contains a strong negative cis-acting element(s). To determine the region responsible for lowering the promoter activity, we generated two expression constructs, −910/−487-pGL2 and −457/+359-pGL2. Interestingly, both expression constructs showed a significant increase of luciferase activity, 6- and 12-fold, respectively (Fig. 3). Because the region from −486 to −458 bp is not present in both of these constructs, we therefore speculated that this region and most likely the adjacent sequences (from −490 to −440 bp) contain a negative cis-acting element(s) critical for the basal F-promoter activity in AC16 cells (Fig. 3, hatched column). Computer-assisted analysis (MatInspector 7.4.3./06, TESS (TRANSFAC Version 6.0) and Alibaba2.1) of the sequence from −490 to −440 bp showed several potential transcription factor binding sites, including NF-κB among others (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 3.

Functional analysis of hERα F-promoter deletion constructs in AC16 cells. The length of the promoter fragments are displayed by numbers (bp) referring to the transcription start of F-transcript, +1 bp. One μg of the promoter reporter construct and 10 ng of the Renilla luciferase reporter construct, as internal control, were co-transfected into AC16 cells using FuGENE® 6 reagent. Values represent firefly luciferase activities normalized to Renilla luciferase activities. The region between −486 and −458 bp contains a negative cis-acting element(s) critical for the basal F-promoter activity (marked with a hatched column). *, p ≤ 0.008 relative luciferase activities of promoter constructs versus the activity of pGL2-basic. All experiments were done in triplicate. Results are expressed as the means of separate transfection experiments (n = 5). The error bars represent ± S.E.

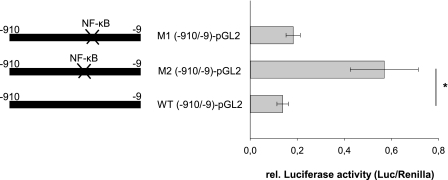

NF-κB Binds within the hERα F-promoter

The functional significance of the NF-κB binding site to the hERα F-promoter was first investigated by site-directed mutagenesis. Mutation within the NF-κB binding sites (M2 (−910/−9)-pGL2) resulted in a significant increase of basal F-promoter activity in AC16 cells (Fig. 4). In contrast, no significant changes in luciferase activity were observed when the second putative NF-κB binding site, located downstream of the identified regulatory region, was mutated (M1 (−910/−9-pGL2)-pGL2). This experiment suggests that the NF-κB binding site located within the region −490 to −440 bp mediates the inhibition of the basal activity of hERα F-promoter.

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptional activity of the F-promoter after site-directed mutagenesis of putative binding sites for NF-κB. Shown are AC16 cells were co-transfected with 1 μg of either wild type reporter construct (−910/−9-pGL2) or reporter constructs containing mutations within the NF-κB binding site (M2 (−910/−9-pGL2)-pGL2) or the second NF-κB binding site (M1 (−910/−9-pGL2)-pGL2) downstream of the identified inhibitory region and 10 ng of Renilla luciferase reporter construct. All experiments were done in triplicate, and luciferase activities were measured 24 h after transfection. Mutations within the NF-κB binding site (M2 (−910/−9-pGL2)-pGL2) resulted in significant changes in luciferase activity, whereas mutations within NF-κB binding site (M1 (−910/−9-pGL2)-pGL2) showed no changes. Results are expressed as the means of separate transfection experiments (n = 6). The S.E. is indicated by the error bars. *, p ≤ 0.004 for the mutation constructs, and the relative luciferase activities of mutated constructs are shown relative to the activity of the wild type construct.

To confirm whether the NF-κB transcription factor binds within the region −490 to −440 bp, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift/supershift assays using nuclear extracts prepared from AC16 cells and synthetic oligonucleotides containing the NF-κB binding site. Three different DNA-protein complexes were formed (Fig. 5). These shifted bands could be competed by 100-fold molar excesses of the unlabeled oligonucleotide (Fig. 5). The addition of antibody against NF-κB p50 resulted in a supershifted band demonstrating the binding of the p50 subunit of the NF-κB transcription factor to its consensus sequence (Fig. 5). Taken together, the transcription factor NF-κB (p50) interacts with the ERα F-promoter. Most likely, NF-κB functions as a suppressor in the transcriptional regulation of the ERα gene in the human heart.

FIGURE 5.

NF-κB binds to the −483 to −448-bp sequence within the hERα F-promoter. Electrophoretic mobility shift and supershift assays with the nuclear extracts from AC16 cells were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The DNA-protein complex was analyzed by gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography (lane 2). For competition assay, the nuclear extract was preincubated with a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide before the addition of the probe (lane 3). For the supershift assay, the nuclear extract was preincubated with a different amount of antibody, anti-NF-κB p50 (2, 4, and 6 μg) on ice for 30 min before the addition of the probe (lanes 4–6). Lane 1 contains only the labeled oligonucleotide. S and SS mark shifted bands and supershifted band, respectively.

Inhibition of NF-κB Increases the hERα F-promoter Activity

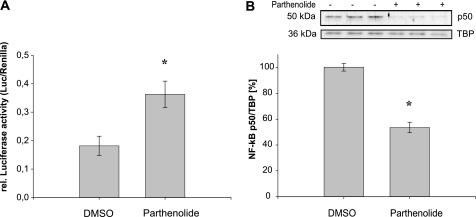

In further experiments, we confirmed the inhibitory effect of NF-κB on the expression of ERα gene. The AC16 cells were transiently transfected with the −910/−9-pGL2 expression construct and treated with parthenolide, a well known inhibitor of NF-κB activation (28). Parthenolide blocks the NF-κB activation by stabilizing its inhibitor IκB, resulting in cytoplasmic retention of NF-κB. The incubation of AC16 cells with parthenolide led to a significant increase of hERα F-promoter activity in comparison with vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 6A). We conclude that NF-κB binding reduces the transcriptional activation of the hERα promoter. Furthermore, the amount of NF-κB p50 was significantly decreased in the nuclear extract of AC16 cells treated with parthenolide (Fig. 6B). Thus, the inhibition of translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus leads to an increase of hERα F-promoter activity in AC16 cells.

FIGURE 6.

A, inhibition of NF-κB resulted in an enhanced luciferase F-promoter reporter activity in AC16 cells. The −910/−9-pGL2 reporter construct was cotransfected with Renilla luciferase reporter construct into AC16 cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were either treated with parthenolide (10 μmol/liter) or left untreated. Six hours after treatment the cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. B, parthenolide inhibits the translocation of NF-κB into nucleus. Representative Western blot performed with nuclear extracts of AC16 cells. Cells at 60–80% confluence were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or parthenolide (10 μmol/liter). After 6 h of treatment, cells were harvested, and nuclear proteins (5 μg) were isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were incubated with anti-NF-κB p50 antibody. Nuclear specific protein TFIID (TBP) was used for normalization as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results are expressed as the means of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. The error bars represent ±S.E. *, p < 0.05.

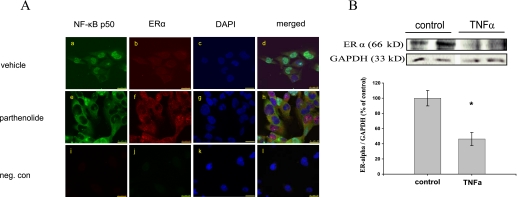

To characterize more extensively the inhibitory role of NF-κB in the regulation of hERα gene, we examined the effects of an inhibition of NF-κB on the hERα gene expression in AC16 cells using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Indeed, the inhibition of NF-κB p50 translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus was visualized after the treatment of the AC16 cells with parthenolide. In vehicle-treated cells, NF-κB was readily detected in nuclei and to a lesser extent in the cytoplasm, which was monitored by a strong green fluorescence (Fig. 7Aa). In contrast, in cells treated with parthenolide, only minimal NF-κB nuclear immunoreactivity was found (Fig. 7Ae). As expected, we observed in the parthenolide-treated cells an up-regulation/accumulation of ERα in both nuclei and cytoplasm of AC16 cells (Fig. 7, Ab and Af). Moreover, we investigated the role of NF-κB in the regulation of expression of hERα gene through activation of NF-κB by treatment of the AC16 cells with TNFα. We indeed could show that the proinflammatory stimulus TNFα, because of the induction of NF-κB activity, significantly reduced the expression of hERα in AC16 cells (p ≤ 0.01; Fig. 7B). These results confirm the ability of NF-κB to suppress the transcription of hERα gene. Thus, the NF-κB signaling pathway suppresses hERα gene expression in AC16 cells.

FIGURE 7.

A, representative confocal images demonstrating the effect of NF-κB inhibition on the expression/accumulation of ERα. AC16 cells were treated with vehicle or parthenolide for 6 h and then fixed. NF-κB and ERα localizations were assessed by Immunofluorescence. The green fluorescence (fluorescein isothiocyanate) shows the location of NF-κB p50 and the red fluorescence (Cy-3), the location of ERα in AC16 cells. The nuclei were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). a and b, in most AC16 cells treated with vehicle, NF-κB was localized strongly in the nuclei, whereas ERα signal was detected at a low level in cytoplasm and nuclei. e and f, by contrast, in most AC16 cells treated with parthenolide, the staining pattern of NF-κB was predominantly cytoplasmic, with very low NF-κB p50 immunoreactivity in nuclei. In these cells, however, cytoplasm and a lot of nuclei showed very strong immunoreactivity for ERα in comparison to the untreated cells. c, g, and k, nuclei counterstaining using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. d, h, and l, merged images from a–c, e–g, and i–k, respectively. i–l show the negative control where the primary antibodies against NF-κB and ERα were omitted; 63× magnification; calibration bar, 25 μm. B, TNFα treatment significantly reduced the protein expression level of hERα in AC16 cells (p ≤ 0.01). A representative Western blot demonstrating protein expression of ERα in AC16 cells treated or non-treated with TNFα for 5 h is shown. Cells were harvested, and whole cell extracts (50 μg) were isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis. Blots were incubated with anti-ERα antibody. Membranes were subsequently re-probed with a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-specific antibody as the internal standard. Data are calculated as the percent of non-treated cells (controls set as 100%) and are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments (n = 3) carried out in duplicate.

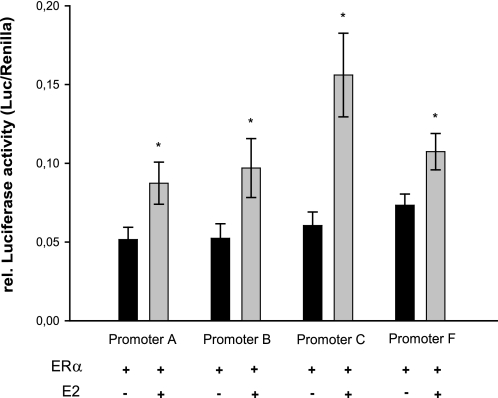

E2 Promotes the Transcriptional Activity of Different hERα Promoter Variants

To examine the effect of E2 on the activity of the ERα promoter variants A, B, C, and F, identified in the human myocardium, the luciferase reporter constructs containing these promoter fragments were transiently transfected into AC16 cells cultured in estrogen-free medium. The relative luciferase activities of all hERα promoter variants did not change significantly in response to E2 (10−8 mol/liter) alone in AC16 cells (data not shown). Because other studies showed an autoregulatory effect of ERα on some ERα promoter variants upon E2-treatment, we therefore co-transfected the various ERα promoter reporter constructs along with the pSG-hERα66 vector (Hego-vector) into AC16 cells. As shown in Fig. 8, in the presence of ERα the transcriptional activation of all analyzed hERα promoters was significantly elevated in response to E2, indicating that in the human myocardium, ERα promoter variants A, B, C, and F transmit the functional response to E2.

FIGURE 8.

E2 increases the transcriptional activity of different hERα promoter variants via ERα. Various luciferase reporter constructs (A-promoter-pGL2, B-promoter-pGL2, C-promoter-pGL2, F-promoter-pGL2 (−1218/+358-pGL2)) were co-transfected with HEGO-vector along with Renilla luciferase reporter construct into AC16 cells, and the cells were then treated with estrogen (E2, 10−8 mol/liter) or left untreated. After 48 h, the luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity in each experiment. The graph shows the relative changes in reporter activity in response to E2. Results are expressed as the mean of more than three independent experiments performed in triplicate. The error bars represent ±S.E. *, p < 0.05 versus without stimulation.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to demonstrate that in the human heart the expression of the ERα gene is regulated by multiple promoter variants, namely A, B, C, and F. Among them, however, the hERα F-promoter variant demonstrates the most frequently utilized promoter in the human heart. Moreover, activated transcription factor NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, binds to, and inhibits hERα F-promoter activation. This effect can be antagonized using parthenolide, a NF-κB inhibitor. Finally, the transcriptional activities of all identified hERα promoter variants are significantly elevated in response to E2 in AC16 cells. For this effect, hERα itself is necessary.

The human ERα mRNA is transcribed from at least seven different promoters with unique 5′-UTRs (A, B, C, D, E, F, and T), which are utilized in a cell- and tissue-specific manner (17, 18). Our data in the present study show that the transcript with the 5′-UTR variant F is the major transcript of the ERα gene, suggesting that the hERα F-promoter is the predominant promoter utilized to initiate the transcription of the ERα gene in the human heart. Several recent studies described that this distal F-promoter also plays a major role in the regulation of ERα mRNA in human bone and primary osteoblasts (16, 21, 29). However, the predominant promoter variants utilized for the expression of the ERα gene in human endometrium are the A and C promoters, in ovaries are the C and F promoters, and in liver is the E promoter (12). It has been proposed that all these multiple promoters are utilized for a physiological fine-tuning of the ERα gene expression in a tissue-specific manner (12, 20).

For further in vitro investigation, we have chosen a human adult left ventricular cardiomyocyte cell line, the AC16 cells (27). The presence of the combination of transcription factors, e.g. GATA4, MYCD, and NFATc4, in addition to cardiac- and muscle-specific markers, e.g. α-cardiac actin, α-major histocompatibility complex (α-MHC), β-MHC, α-actinin, Cx-40, is a good indication for the presence of a cardiac transcription program in these cells. This cell line, therefore, appears to be an appropriate model for studying regulation of ERα. As in the human heart, the transcription of the ERα gene in the AC16 cells is initiated from at least two promoters, C and F (data not shown). We, therefore, assumed that AC16 cells may contain the necessary transcription factors for regulation of hERα promoter activity.

One region within the F-promoter (−490 to −440 bp) contains a strong negative cis-acting element(s), critical for regulation of the basal F-promoter activity (Fig. 3), which includes a putative binding site for transcription factor NF-κB. Mutation within this binding site increases the basal F-promoter activity (Fig. 4), indicating the inhibitory role of these transcription factors on the hERα F-promoter activity. Interestingly, in human osteoblasts, an approximately similar region within the F-promoter was described to have an inhibitory effect on the transcriptional activity of the F-promoter (30). In human osteoblasts, however, the binding of transcription factor Runx2 within this region leads to transcriptional repression. These data support the view that hERα promoters are regulated in a tissue-specific manner.

NF-κB is a nuclear transcription factor which regulates the transcription of various genes involved in cellular processes including inflammation, cell adhesion and migration, apoptosis, and development (for review, see Ref. 31). NF-κB is composed of five members of the Rel family, p50, p52, p65, RelB, and c-Rel, which is formed by homo- or heterodimerization of these proteins in a cell-specific manner (31). So far, p65, p50, p52, and RelB members of NF-κB family have been detected in cardiac myocytes (32–34). NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm as an inactive complex with IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB). Upon stimulation, IKK (IκB kinase) phosphorylates IκB, resulting in ubiquitination, degradation of IκB, and releasing of NF-κB, which subsequently translocates into the nucleus and modulates the transcription of target genes (35). Parthenolide, a well known inhibitor of NF-κB pathway, causes cytoplasmic retention of NF-κB by inhibiting phosphorylation and/or degradation of IκB (28). Our data show that the NF-κB p50 is able to bind to the inhibitory region (−483 to −448 bp) within the hERα F-promoter (Fig. 5) and negatively regulates the hERα gene expression in AC16 cells. Parthenolide-mediated depletion of NF-κB in nucleus abolishes the inhibitory effect of NF-κB on transcriptional activity of the hERα F-promoter (Fig. 6). Indeed, our immunocytochemical data in the AC16 cells show that higher levels of hERα are present in both nuclei and cytoplasm when NF-κB activity is inhibited (Fig. 7A). By contrast, increased amounts of NF-κB diminished the protein expression level of hERα in AC16 cells (Fig. 7B). These experiments indicate that NF-κB complex represses, at least partially, the basal F-promoter activity of the hERα gene.

In line with our data, Holloway et al. (35) showed that elevated NF-κB activity leads to the down-regulation of ERα in breast cancer cells. An inhibition of NF-κB activity in these cells resulted in up-regulation of ERα expression. NF-κB activation is increased in different heart diseases, such as hypertrophy (36–38), myocardial infarction (39, 40), ischemic-reperfusion (I/R) injury (41), and myocarditis (42). Inhibition of elevated NF-κB activity improves cardiac function and survival in these diseases. Many studies have addressed that the inhibition of NF-κB activity by E2-bound ER inhibits the NF-κB-dependent gene expression such as proinflammatory cytokines (for review, see Refs. 43 and 44). In this respect, a part of the cardiovascular benefits of estrogen are because of inhibition of NF-κB activity mediated by ligand-bound ER (34, 45). In postmenopausal women with established coronary artery disease, E2 has failed to slow the progression of atherosclerosis (46). This may be because of a decreased level of ER, especially ERα, in the atherosclerotic tissue (47). NF-κB activity has been shown to be increased in chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis and may contribute to this effect (48–51).

Finally, we analyzed the effects of E2 on the transcriptional activity of different hERα promoters in AC16. Human ERα promoter variants A, B, C, and F contribute to E2 responsiveness in the presence of hERα (Fig. 8). In agreement with our data, other studies showed that all active ERα promoters in MCF-7, FEM-19, and ZR-75 cells are up- or down-regulated in a coordinate way by E2, suggesting that the tissue-specific differential promoter usage along with transcription factors present within a cell might determine whether ERα expression is increased or decreased by E2 (12, 26). Additionally, in agreement with studies which reported the autoregulation of some ERα promoters by E2 (16, 26, 52, 53), our data show that for the E2-mediated transcriptional activity of hERα A-, B-, C- and F-promoter, the presence of hERα is necessary. The molecular mechanisms that result in the cell type-specific autoregulation of ERα expression level are not well understood. It is, however, assumed that the half-estrogen response elements within hERα promoters could be responsible for regulating all promoters in concert (26).

The experiments represented in this study only allow limited speculations on physiological or pathological functions of these promoters in the heart. However, the fact that the transcriptional activity of the ERα promoters in response to E2 is increased, the recognition of the molecular mechanisms controlling the tissue-specific patterns of hERα promoters, and the individual transcription factor/co-factor profiles within the cells could provide useful targets for prevention and treatment of heart disease. E2 was found to be particularly ineffective in the secondary prevention of atherosclerosis; the inhibition of ERα transcription by NF-κB may provide a clue to understanding the potential unresponsiveness of tissues with proinflammatory pathologies such as atherosclerosis to E2 supplementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. R. Hetzer, director of German Heart Institute Berlin, for providing human myocardial tissues and Prof. Dr. P. Chambon for providing HEGO vector. We also thank Dr. Hugo Sanchez-Ruderisch for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Nationales Genom Forschungsnetz and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK 754, FG 1054, RE 662/6-1).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- hER

- human ER

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- E2

- 17β-estradiol

- LV

- left ventricle

- 5′-UTR

- 5′-untranslated region

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- SOE

- splicing overlap extension

- 5′-RACE

- 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- FW

- forward

- RV

- reverse.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mendelsohn M. E., Karas R. H. (2005) Science 308, 1583–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangelsdorf D. J., Thummel C., Beato M., Herrlich P., Schütz G., Umesono K., Blumberg B., Kastner P., Mark M., Chambon P., Evans R. M. (1995) Cell 83, 835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karas R. H., Patterson B. L., Mendelsohn M. E. (1994) Circulation 89, 1943–1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkov C. D., Rankin A. B., Vaughan D. E. (1996) Circulation 94, 727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordmeyer J., Eder S., Mahmoodzadeh S., Martus P., Fielitz J., Bass J., Bethke N., Zurbrügg H. R., Pregla R., Hetzer R., Regitz-Zagrosek V. (2004) Circulation 110, 3270–3275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grohé C., Kahlert S., Löbbert K., Stimpel M., Karas R. H., Vetter H., Neyses L. (1997) FEBS Lett. 416, 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmoodzadeh S., Eder S., Nordmeyer J., Ehler E., Huber O., Martus P., Weiske J., Pregla R., Hetzer R., Regitz-Zagrosek V. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 926–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ropero A. B., Eghbali M., Minosyan T. Y., Tang G., Toro L., Stefani E. (2006) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41, 496–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelsohn M. E., Karas R. H. (1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 1801–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simoncini T., Genazzani A. R., Liao J. K. (2002) Circulation 105, 1368–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J. K., Pedram A., Razandi M., Levin E. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6760–6767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flouriot G., Griffin C., Kenealy M., Sonntag-Buck V., Gannon F. (1998) Mol. Endocrinol. 12, 1939–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shupnik M. A., Gordon M. S., Chin W. W. (1989) Mol. Endocrinol. 3, 660–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho H. S., Ng P. A., Katzenellenbogen B. S. (1991) Mol. Endocrinol. 5, 1323–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freyschuss B., Sahlin L., Masironi B., Eriksson H. (1994) J. Endocrinol. 142, 285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denger S., Reid G., Brand H., Kos M., Gannon F. (2001) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 178, 155–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kos M., Reid G., Denger S., Gannon F. (2001) Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 2057–2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuda Y., Hirata S., Watanabe N., Shoda T., Kato J., Hoshi K. (2003) Endocr. J. 50, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson D. A., McPherson L. A., Carmeci C., deConinck E. C., Weigel R. J. (1997) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 62, 143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandien K. (1996) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 116, 207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambertini E., Penolazzi L., Giordano S., Del Senno L., Piva R. (2003) Biochem. J. 372, 831–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuur E. R., McPherson L. A., Yang G. P., Weigel R. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15519–15526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Z., Treilleux I., Brown M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 1274–1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanimoto K., Eguchi H., Yoshida T., Hajiro-Nakanishi K., Hayashi S. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 903–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clayton S. J., May F. E., Westley B. R. (1997) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 128, 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donaghue C., Westley B. R., May F. E. (1999) Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 1934–1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson M. M., Nesti C., Palenzuela L., Walker W. F., Hernandez E., Protas L., Hirano M., Isaac N. D. (2005) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 133–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hehner S. P., Heinrich M., Bork P. M., Vogt M., Ratter F., Lehmann V., Schulze-Osthoff K., Dröge W., Schmitz M. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1288–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penolazzi L., Lambertini E., Giordano S., Sollazzo V., Traina G., del Senno L., Piva R. (2004) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 91, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambertini E., Penolazzi L., Tavanti E., Schincaglia G. P., Zennaro M., Gambari R., Piva R. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 1548–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall G., Hasday J. D., Rogers T. B. (2006) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41, 580–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisner V., Criollo A., Quiroga C., Olea-Azar C., Santibañez J. F., Troncoso R., Chiong M., Díaz-Araya G., Foncea R., Lavandero S. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 4495–4500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helenius M., Hänninen M., Lehtinen S. K., Salminen A. (1996) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 28, 487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelzer T., Neumann M., de Jager T., Jazbutyte V., Neyses L. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 286, 1153–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holloway J. N., Murthy S., El-Ashry D. (2004) Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1396–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta S., Young D., Maitra R. K., Gupta A., Popovic Z. B., Yong S. L., Mahajan A., Wang Q., Sen S. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 375, 637–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Ha T., Gao X., Kelley J., Williams D. L., Browder I. W., Kao R. L., Li C. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H1712–H1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell N. H., Tang G., Yu C., Mercurio F., DiDonato J. A., Lin A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6668–6673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawano S., Kubota T., Monden Y., Tsutsumi T., Inoue T., Kawamura N., Tsutsui H., Sunagawa K. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H1337–H1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onai Y., Suzuki J., Maejima Y., Haraguchi G., Muto S., Itai A., Isobe M. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H530–H538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasaki H., Galang N., Maulik N. (1999) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 1, 317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Donnell S. M., Hansberger M. W., Connolly J. L., Chappell J. D., Watson M. J., Pierce J. M., Wetzel J. D., Han W., Barton E. S., Forrest J. C., Valyi-Nagy T., Yull F. E., Blackwell T. S., Rottman J. N., Sherry B., Dermody T. S. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2341–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medina R. A., Aranda E., Verdugo C., Kato S., Owen G. I. (2003) Biol. Res. 36, 325–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelligrino D. A., Galea E. (2001) Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 86, 137–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans M. J., Eckert A., Lai K., Adelman S. J., Harnish D. C. (2001) Circ. Res. 89, 823–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hodis H. N., Mack W. J., Azen S. P., Lobo R. A., Shoupe D., Mahrer P. R., Faxon D. P., Cashin-Hemphill L., Sanmarco M. E., French W. J., Shook T. L., Gaarder T. D., Mehra A. O., Rabbani R., Sevanian A., Shil A. B., Torres M., Vogelbach K. H., Selzer R. H. (2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 535–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura Y., Suzuki T., Miki Y., Tazawa C., Senzaki K., Moriya T., Saito H., Ishibashi T., Takahashi S., Yamada S., Sasano H. (2004) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 219, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brand K., Page S., Rogler G., Bartsch A., Brandl R., Knuechel R., Page M., Kaltschmidt C., Baeuerle P. A., Neumeier D. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 97, 1715–1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brand K., Page S., Walli A. K., Neumeier D., Baeuerle P. A. (1997) Exp. Physiol. 82, 297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lentsch A. B., Ward P. A. (2000) J. Pathol. 190, 343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindner V. (1998) Pathobiology 66, 311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castles C. G., Oesterreich S., Hansen R., Fuqua S. A. (1997) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 62, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Treilleux, Peloux N., Brown M., Sergeant A. (1997) Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 1319–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.