Abstract

AMT/Mep ammonium transporters mediate high affinity ammonium/ammonia uptake in bacteria, fungi, and plants. The Arabidopsis AMT1 proteins mediate uptake of the ionic form of ammonium. AMT transport activity is controlled allosterically via a highly conserved cytosolic C terminus that interacts with neighboring subunits in a trimer. The C terminus is thus capable of modulating the conductivity of the pore. To gain insight into the underlying mechanism, pore mutants suppressing the inhibitory effect of mutations in the C-terminal trans-activation domain were characterized. AMT1;1 carrying the mutation Q57H in transmembrane helix I (TMH I) showed increased ammonium uptake but reduced capacity to take up methylammonium. To explore whether the transport mechanism was altered, the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant was expressed in Xenopus oocytes and analyzed electrophysiologically. AMT1;1-Q57H was characterized by increased ammonium-induced and reduced methylammonium-induced currents. AMT1;1-Q57H possesses a 100× lower affinity for ammonium (Km) and a 10-fold higher Vmax as compared with the wild type form. To test whether the trans-regulatory mechanism is conserved in archaeal homologs, AfAmt-2 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus was expressed in yeast. The transport function of AfAmt-2 also depends on trans-activation by the C terminus, and mutations in pore-residues corresponding to Q57H of AMT1;1 suppress nonfunctional AfAmt-2 mutants lacking the activating C terminus. Altogether, our data suggest that bacterial and plant AMTs use a conserved allosteric mechanism to control ammonium flux, potentially using a gating mechanism that limits flux to protect against ammonium toxicity.

All organisms depend on an adequate supply of nutrients, especially nitrogen. For microorganisms and plants, which are able to assimilate ammonium, NH4+ represents the sole bioavailable nitrogen form. (Nitrate use requires enzymatic conversion to ammonia.) Plants preferentially take up ammonium; however, overaccumulation of NH4+ is toxic to microorganisms and plants (1, 2.) Levels above 50 μm become toxic for the central nervous system of most mammals (3, 4). A precise homeostasis of the cellular levels of ammonium is therefore critical.

Plant ammonium uptake is mediated by low affinity/high capacity and high affinity/low capacity transporters (5). Nonselective cation channels (2), potassium channels (6), and members of the aquaporin family appear to be able to mediate NH3/NH4+ low affinity uptake (7–9). High affinity uptake by transporters of the AMT/Mep superfamily is essential at supply levels in the micromolar to low millimolar range (10–12). AMT/Mep ammonium transporter genes were originally identified in yeast and plants by complementation of a yeast mutant deficient in ammonium uptake (13, 14). In contrast to potassium channels, which do not effectively differentiate between potassium and ammonium, AMTs are highly selective for ammonium and its methylated form, methylammonium (MeA).6 Plant AMT1 ammonium transporters were shown to be electrogenic when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, suggesting transport of charged NH4+ or co-transport of NH3 with a proton (15). Quantitation of charge movement and tracer uptake demonstrated that AMT1 transports exclusively the ionic form, i.e. each transported 14C-MeA molecule corresponded to the transfer of a single positive elementary charge across the membrane (16). The high affinity and low capacity of AMT1, which is too slow to be classified as a channel, suggests that it rather functions as a transporter, with significant conformational changes limiting its turnover numbers. Interestingly, it has been suggested that the bacterial homologs use a different mechanism, in that they mediate transport of uncharged NH3 (17), although this hypothesis has been disputed (18, 19).

Biochemical as well as structural analyses of bacterial and archaeal AMTs revealed a highly stable and conserved trimeric complex (15). Each monomer is composed of 11 transmembrane helices (TMHs) that form a noncontinuous channel through which the substrate can pass. Highly conserved residues are observed in positions that are likely crucial for function: a tryptophan located in a central extracellular surface cleft is thought to be part of a selectivity filter, discriminating K+ ions and water molecules from NH4+ via a cation-π interaction and H-bonds via neighboring residues. Below this cleft, a pair of phenylalanines is assumed to function as a gate that blocks the entrance of the channel, which, after that point, appears open to the cytoplasmic side. Two histidines on helices V and VI are in H-bonding distance and line the central part of the channel pathway.

Similar to the bacterial Na+/leucine and the Na+/arabinose transporters (20, 21), AMT monomers are built from an ancient duplication of a subunit of five TMHs, organized as a pseudo-2-fold axis in the membrane plane; in the case of the AMT/Meps, an additional 11th segment M11 (5 + 5 + 1), a 50-Å α-helix, belts the surface of the monomer at an angle of ∼50° relative to the normal vector of the membrane plane and connects to the cytosolic C terminus (17, 23, 24). Recent findings demonstrate that AMTs can exist in active and inactive states, probably controlled by phosphorylation of residues in the conserved C terminus (25).7 In the Arabidopsis thaliana AMT1, an allosteric trans-activation is mediated through the interaction of the C termini with cytosolic loops of the neighboring subunits in a trimer (25). This finding is consistent with a novel regulatory mechanism that can provide for rapid shut-off of transport. This feedback loop may potentially be important for protection against ammonium toxicity by limiting peak output, namely ammonium uptake capacity at high external supply. Analysis of >900 AMT homologs shows that the C terminus is highly conserved from cyanobacteria to fungi and plants, indicating that the regulatory mechanism may be conserved (25).

A suppressor screen using inactive mutants carrying a mutation in the cytosolic C terminus of AMT1;1 identified mutants that had lost their strict dependence on allosteric trans-activation (25). Here, we show that, when expressed in yeast, some of these mutants show increased ammonium transport capacity. Electrophysiological analysis of one of the pore mutants, AMT1;1-Q57H, demonstrates that transport is still electrogenic and that the increased ammonium sensitivity is due to a conversion from a saturable high affinity kinetic profile to low affinity and high capacity uptake kinetics. Mutation of the corresponding glutamine residue (Q53H) also suppresses an inactive mutant of the archaeal Archaeoglobus fulgidus AfAmt-2, demonstrating the conservation of these mechanisms from archaea to higher plants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Complementation Screen

The DL1 (Δmep1, Δmep2, Δmep3, and Δgap1) yeast strain (25) was transformed using LiAc (27) and selected on solid YNB (minimal yeast medium without nitrogen; 233520, Difco) supplemented with 3% glucose and 1 mm arginine. For growth assays, cells were precultured in liquid YNB supplemented with 3% glucose and 0.5 mm arginine until the stationary phase (overnight to 24 h) and diluted 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4 in water, and 5 μl of cell suspension from each dilution were spotted on solid YNB, either buffered with 50 mm MES/Tris, pH 5.2, and supplemented with either NH4Cl or (NH4+)2SO4 for ammonium growth complementation assays or buffered with 50 mm MES/Tris, pH 6.5, and supplemented with 0.1% proline and 5 mm methylammonium for methylammonium sensitivity assays. Experiments shown in Fig. 6 (A and B) were performed in YNB medium buffered with 50 mm MES/Tris, pH 6.4, 3% glucose, and 100 mm KCl with varying NH4Cl concentrations. After 3 or 4 days of incubation at 30 °C, cell growth was documented by scanning the plate at 600 dpi in grayscale mode.

FIGURE 6.

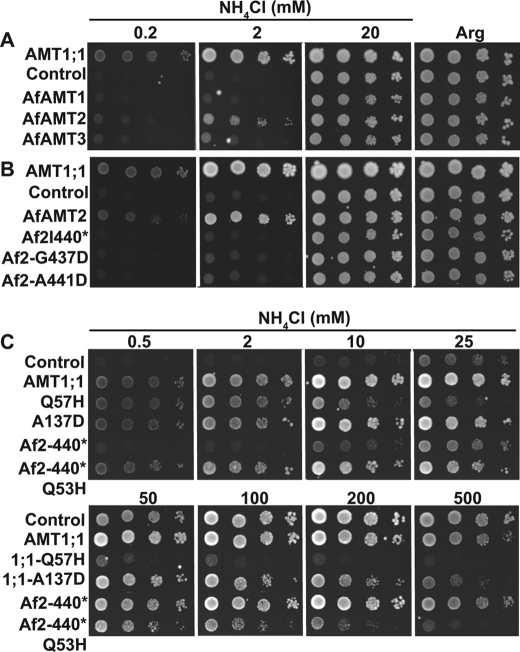

Q53H substitution renders AfAmt-2 independent of its C terminus. Growth assays of DL1 expressing AfAmt-1, -2, or -3 or AMT1;1 on YNB with NH4Cl or Arg recorded after 4 days (A); AMT1;1 or AfAmt-2 (Af2), AfAmt-2-I440stop, AfAmt-2-G437D, or AfAmt-2-A441D on YNB with NH4Cl or Arg recorded after 7 days (B). AMT1;1 (wild type), AMT1;1-Q57H, AMT1;1-A137D, AfAmt-2-I440 (Af2-440*), or AfAmt-2-Q53H-440* (Af2-440*/Q53H) on YNB with NH4Cl or Arg recorded after 3 days (C). Experiments were repeated at least twice independently.

Uptake Assays

For [14C]methylammonium and 15N-labeled ammonium uptake, yeast cells were grown in YNB supplemented with 3% glucose and 1 mm l-arginine. Cells were harvested at an A600 of 0.6–0.8, washed, and resuspended in 40 mm potassium phosphate buffer pH 7 to a final A600 of 8 for [14C]methylammonium uptake assays; or in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.5, to a final A600 of 13.5 for 15N-ammonium uptake assays. Methylammonium uptake assays were conducted with 100 μm of [14C]-labeled methylammonium (Amersham Biosciences) as described (25). For 15N-labeled ammonium uptake assays, 800 μl of cells kept on ice were supplemented with 100 μl of 6% glucose in 100 mm phosphate buffer, pH 5.5, and preincubated for 12 min at 30 °C. To start the reaction, 900 μl of prewarmed (30 °C) solution containing 100 mm phosphate buffer, pH 5.5, 40 mm ammonium chloride (20 mm 14N-ammonium chloride plus 20 mm 15N-ammonium chloride labeled at 99 atom %; Icon Isotopes) were added (final concentration of 20 mm NH4Cl). Cells were incubated in a shaker at 30 °C for 6 min. Cells were immediately transferred on ice for 20 s and then centrifuged for 20 s to pellet the cells and to discard the tracer solution. Cells were washed 3× in 1 ml of ice-cold 100 mm phosphate buffer, pH 5.5, followed by 20 s of centrifugation for each wash. After the last wash, cell pellets were frozen at −20 °C. Cells were dried at 65 °C for 72 h. For each sample, the complete cell pellet was used for 15N determination by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (12).

Preparation and Injection of Oocytes

For electrophysiological analyses, the cDNAs of AMT1;1 and the mutant AMT1;1-Q57H were cloned into the pOO2 cloning vector (28). After linearization of the plasmid with BbrP1 (Roche), capped cRNA was transcribed in vitro by SP6 RNA polymerase using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). Xenopus laevis oocytes were obtained by surgery, manually dissected, and defolliculated with collagenase (Sigma). Oocytes, stage V and VI, were injected with 50 nl of water or cRNA (36 ng/oocyte). The cells were kept at 16 °C in ND96 medium containing 96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, containing gentamycin (50 μg/μl) and pyruvate.

Electrophysiological Assays

The electrical activity induced by AMT1;1 or AMT1;1-Q57H was recorded 4–6 days after cRNA injection by two-electrode voltage-clamping, using a Geneclamp 500B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) connected to a Compaq 486 computer through the digital analog converter Digidata 1200A (Molecular Devices). Voltage protocols and data acquisition were controlled by the Clampex and Clampfit programs included in the pClamp 6 software package (Molecular Devices). Borosilicate microelectrodes (P1174, Sigma) were filled with 1 m KCl with a tip resistance of 0.5–3 MΩ. Oocytes were bathed with a standard solution containing 1 mm MgCl2, 1.8 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm Tris/Mes, pH 7.0, with the osmolality adjusted to 240–260 mosmol/kg using d-sorbitol; the bath solution was maintained at a constant flow of 5 ml min−1. When the membrane potential read by the voltage and current electrodes was the same and stable for >2 min, experiments were started. For all measurements, oocytes were clamped at their resting membrane potential (between −110 and −120 mV). The currents carried either by AMT1;1 or AMT1;1-Q57H were activated by the inclusion of NH4Cl or different alkali cations in the standard solution. Experiments were performed on several oocytes from different donors for each condition. The data presented are the mean ± S.D. from a number (n) of independent experimental observations.

RESULTS

AMT1;1-Q57H and -A138P Mutants Cause Ammonium Toxicity in Yeast

A suppressor screen compensating for a defective cytosolic C terminus (CCT) (25) identified five residues in the pore region (TMH I and III) located within a range of ∼5 Å in the crystal structure. The mutations reactivate the nonfunctional AMT1;1-T460D mutant version of AMT1;1 (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S1) (25). The indispensable domain of ∼20 amino acids of the CCT comprising the intra- and inter-trans-interaction domains are highly conserved throughout the plant/fungal clade of AMTs (25). To characterize the properties of the suppressor mutants in detail, all five mutations (supplemental Table S1) were introduced into wild type AMT1;1 with an intact C terminus and expressed in a yeast strain lacking all three AMT homologs (DL1 (Δmep1, Δmep2, Δmep3, and Δgap1)). DL1 is unable to grow on media containing moderate ammonium levels. All five mutants restored growth on low levels of ammonium (Fig. 2).

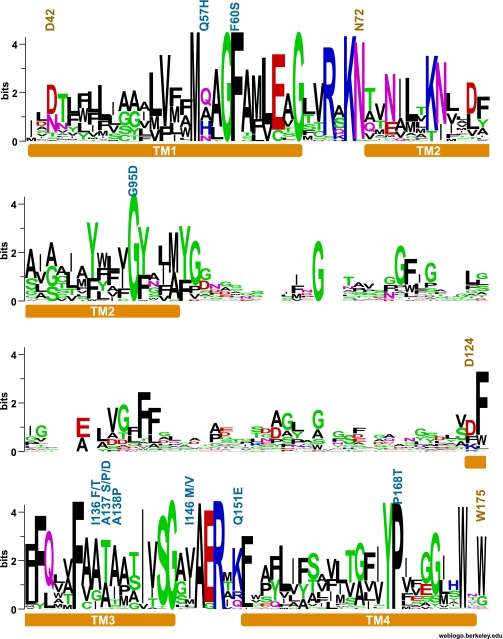

FIGURE 1.

Conservation of residues in TMH I–IV of the AMT/Mep transporter family. AMT sequences (933 sequences) were obtained from NCBI using the BLAST algorithm with the Arabidopsis AMT1;1 protein sequence (26); and after the phylogenetic analysis (25), the sequences were grouped into three clades. Clade 2 (246 sequences) includes all plant AMT1 sequences and homologs from eubacteria. (This clade does not include AMT2.) The graphic representation of the consensus sequence was obtained using WEBLogo (red, negatively charged; blue, positively charged; green and black, neutral amino acids).

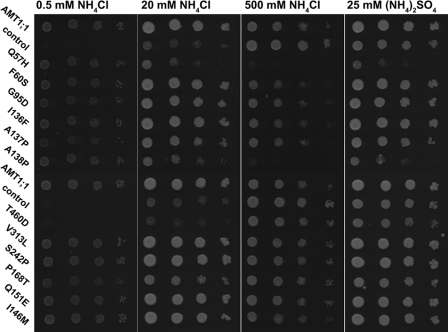

FIGURE 2.

Mutation of Q57H or A138P in AMT1;1 increases NH4+ toxicity. Growth assays of DL1 expressing AMT1;1 mutants were performed on YNB with NH4Cl or (NH4)2SO4 and recorded after 3 days. Experiments were repeated at least three times independently.

In standard yeast media, wild type yeast tolerates extraordinarily high ammonium levels (at least up to 1 m). Surprisingly, yeast expressing AMT1;1-Q57H or AMT1;1-A138P were sensitive to 20 mm ammonium; an effect that became more severe at higher concentrations (Fig. 2). To test whether toxicity was caused by increased permeability for ammonium or chloride ions, the growth assay was performed using ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2). Ammonium sulfate had a comparable effect as ammonium chloride. The ability to mediate growth on low ammonium levels suggests that ammonium sensitivity is due to an increased uptake capacity for ammonium. Consistent with an increase in ammonium transport capacity, both Q57H and A138P mutants mediated a >2-fold higher 15N-ammonium uptake compared with wild type (supplemental Fig. 1).

AMT1;1-Q57H Shows a Decreased Ability to Transport MeA in Yeast

Because AMT1;1 also transports the ammonium analog MeA, MeA toxicity was tested using growth assays (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, cells expressing the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant showed decreased MeA sensitivity compared with wild type, as did AMT1;1-F60S, whereas cells expressing AMT1;1-A138P were as sensitive as AMT1;1. AMT1;1-F60S mediated the highest MeA tolerance, followed by AMT1;1-P168T, -Q57H, and -A137P; weak tolerance was also observed in the case of AMT1;1-G95D. It thus seems possible to separate the capacity of ammonium and MeA transport by mutation of residues in TMH I–IV. Uptake assays with [14C]MeA demonstrated that AMT1;1-Q57H had reduced MeA uptake capacity (Fig. 3B).

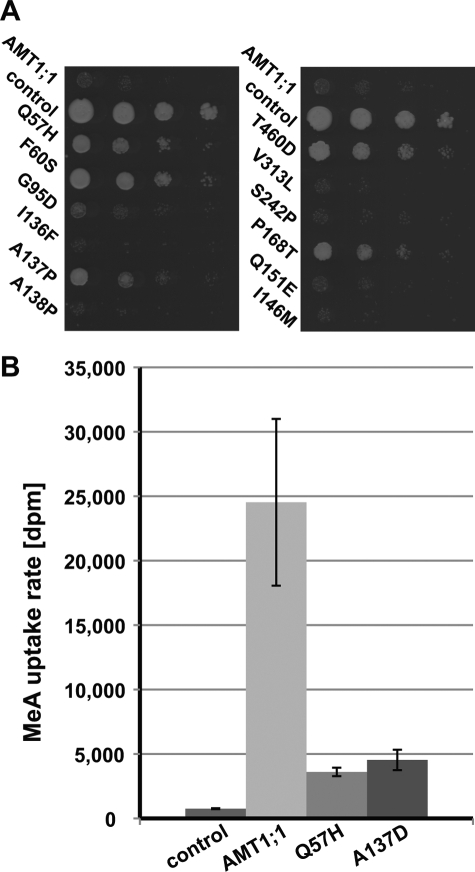

FIGURE 3.

Methylammonium uptake by AMT mutants. A, methylammonium tolerance was tested by plating DL1 expressing AMT1;1 mutants on YNB with 5 mm methylammonium and 0.1% proline. Empty vector served as a control. B, shown are methylammonium uptake rates mediated by AMT1;1-Q57H. Error bars indicate S.D. of nine replicates.

The Mutant AMT1;1-Q57H Is Electrogenic with Increased NH4+ Conductance

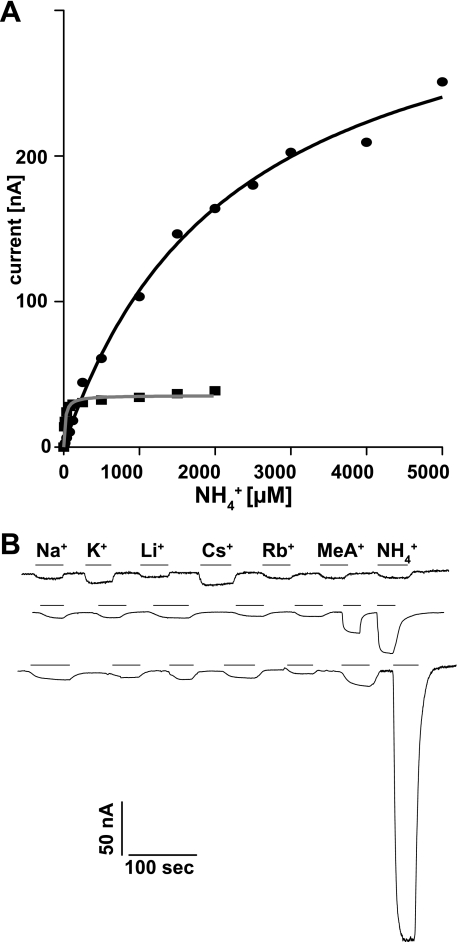

Because the selectivity of the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant (in AMT1;1 with a wild type C terminus) was altered and because Rh family homologs of AMTs were shown to transport uncharged ammonia (29), it is conceivable that the AMT1;1-Q57H mutation induces a change from the strict transport of ammonium ions to the transport of ammonia. To test electrogenicity of the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant, currents activated by extracellular ammonium in Xenopus oocytes were measured. The AMT1;1-Q57H mutant was electrogenic, and currents elicited by 1 mm ammonium in the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant were ∼10× larger compared with currents recorded for AMT1;1 (Fig. 4A). Fitting of the currents carried by AMT1;1 to Michaelis-Menten kinetics yielded a Km value for ammonium of 34 μm and a Vmax of 33 nA, (Fig. 4A, n = 13). Currents induced by ammonium in oocytes expressing AMT1;1-Q57H did not saturate within the range of ammonium levels that could be tested. When force fitted to Michaelis-Menten kinetics, the calculated Km was 2,232 μm with a Vmax of 365 nA (n = 13). Due to endogenous currents induced by high ammonium in untransfected oocytes (30), it was not possible to assess activities at NH4+ concentrations higher than 5 mm; thus, it remains open whether or not the mutant behaves as a channel. The currents were specific to ammonium because other monovalent cations including potassium, lithium, rubidium, and sodium did not elicit currents above background (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the pH independence of the currents, which had been observed for AMT1;1 (28), is retained for the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant (supplemental Fig. 2). As expected from the yeast experiments (Fig. 3B), MeA elicited significantly lower currents as compared with ammonium in oocytes expressing the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Functional expression of AMT1;1-Q57H mutant in oocytes. A, AMT1;1 showed saturation kinetics for NH4+-induced currents with a Km for ammonium of 34 ± 7 μm (n = 14), whereas the currents mediated by AMT1;1-Q57H did not saturate in the range tested (force fit to Michaelis-Menten kinetics yielded a Km = 2.2 ± 0.4 mm; n = 13). B, shown are the inward currents from different oocytes injected with water (H2O) or the cRNA from AMT1;1 (wild type) and the mutant AMT1;1-Q57H (Q57H). The original recordings show the currents induced with 1 mm of chloride salts of the different cations (indicated by the lines). Oocytes were clamped at −120 mV. Similar results were obtained from six oocytes.

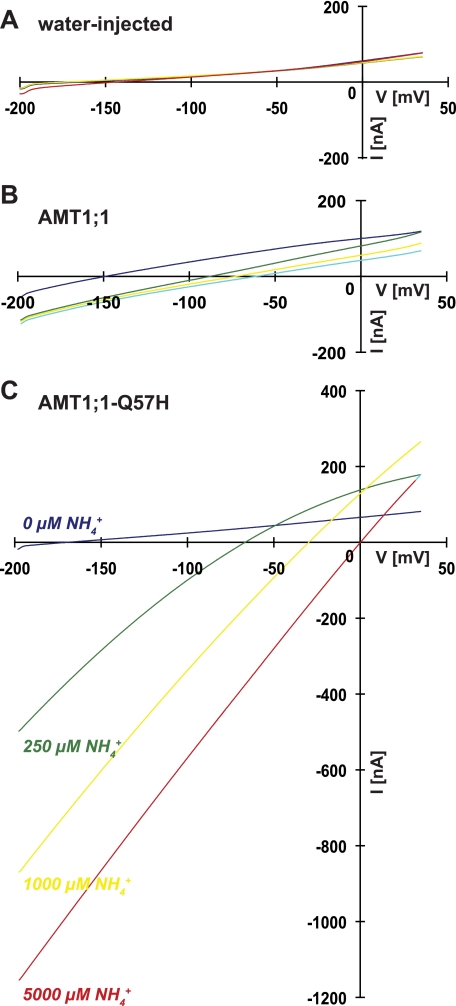

Application of voltage ramps to oocytes expressing the AMT1;1 or AMT1;1-Q57H exposed to different extracellular ammonium concentrations yielded larger shifts in the reversal potential Er toward more positive potentials with increasing ammonium concentrations, further supporting the notion that AMT1;1-Q57H is more permeable to ammonium (Fig. 5). Associated with the changes in Er, larger inward currents were recorded for AMT1;1-Q57H at all ammonium concentrations (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Q57H substitution in AMT1;1 enhanced its permeability for ammonium. Changes in magnitude and Er of the inward currents activated by increasing concentrations of ammonium in water injected (H2O), AMT1;1 (wild type), and AMT1;1-Q57H (Q57H). Currents induced by the application of voltage ramps from −200 to 30 mV. Representative recordings were from 4–10 oocytes.

The results demonstrate that a single nucleotide change in AMT1;1 resulting in a single amino acid change modulates the pore structure resulting in increased selectivity and reduced affinity toward ammonium. The amplitude and nonsaturated currents in AMT1;1-Q57H, together with the significant changes in Er caused by ammonium, suggest that AMT1;1-Q57H operates as a channel. Attempts to record single channel activity from the membrane of AMT1;1-Q57H-injected oocytes have not been successful.

Conservation of the Regulatory Mechanism in Archaebacteria

The extraordinary conservation of the C-terminal domain between bacteria, fungi, and plants and the structural evidence for an interaction of the C terminus with the loops of the neighboring subunit suggest that the allosteric regulatory mechanism is evolutionary highly conserved (25). To test for dominant interactions of subunits in the archaeal homologs, the Archaeoglobus AfAmt-1, -2, and -3 homologs were expressed in the yeast ammonium transport mutant DL1. After 4 days, only AfAmt-2 was able to confer the ability to grow on low ammonium to the yeast strain DL1 (Fig. 6A). To test whether the conserved C terminus of AfAmt-2 is also required for transport function, point mutations and deletions were introduced into the C terminus of AfAmt-2. AfAmt-2-I440* (deletion of the C-terminal 29 amino acids after position 440 in AfAmt-2) lacks the highly conserved part of the C terminus AfAmt-2-G437D carries a mutation leading to exchange of the highly conserved glycine to aspartate (Gly-456 in the Arabidopsis AMT1;1); and AfAmt-2-A441D is equivalent to the Arabidopsis AMT1;1-T460D mutation (25). All three mutants lost their ability to transport ammonium (Fig. 6B). To identify suppressor mutants able to reactivate the AfAmt-2-I440* mutant, a multicopy suppressor screen was performed (similar as in Ref. 25). Twenty-one suppressor mutants were isolated and sequenced (Table 1). All variants carried mutations affecting residue Gln-53 of AfAmt-2 (Q53H, Q53E, and Q53K). Gln-53 in AfAmt-2 corresponds to residue Gln-57 in AMT1;1, and all three suppressor mutations (Q53H, Q53E, and Q53K) obtained are identical to the ones found in the suppressor screen using the defective AMT1;1-T460A (25). Yeast cells expressing AfAmt-2-Q53H-I440* were able to grow on low ammonium concentrations (0.5 and 2 mm) but were sensitive to NH4+ concentrations above 100 mm (Fig. 6C).

TABLE 1.

Suppressor screen in yeast expressing AfAmt-2-I440stop. DL1 expressing AfAmt-2-I440stop was incubated on YNB supplemented with 2 mm NH4Cl at 28 °C for 14 days. Plasmids were isolated from 21 independent suppressors. The data represent the sequencing results of 21 independent AfAmt-2-I440stop suppressors.

| Mutation | Codons | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Q53H | CAT | 4 |

| Q53H | CAC | 7 |

| Q53E | GAG | 6 |

| Q53K | AAG | 4 |

| Total | 21 |

DISCUSSION

A careful analysis of AMT1 ammonium transporter mutants had revealed a novel allosteric regulatory mechanism, in which the C-terminal domain (CCT) is responsible for allosteric regulation of the activity of the three pores in the trimeric complex (25). When expressed in yeast (25) and oocytes (31), plant AMT requires a productive interaction of the subunits via the CCT; otherwise, all three pores of the trimer are closed. Certain mutations in the pore can relieve the complex from inactivation even when the trans-activating C terminus is deleted (25). Among the 9 suppressors identified from the AMT1;1-T460A suppressor screen, at least one variant, Q57H, showed significantly higher ammonium transport activity, compared with the wild type, as evidenced by elevated ammonium sensitivity, elevated uptake rates, and increased conductance measured by two-electrode voltage clamping. The kinetics changed from saturable with a Km of 30 μm in AMT1;1 to nonsaturable in case of the mutant AMT1;1-Q57H, characterized by at least 10× higher maximal currents. The finding that a mutation in the pore region leads to dramatically increased conductance suggests that the protein is normally kept in a “restricted state.” The findings here supports the notion that the actual substrate of both AMT1;1 and the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant is NH4+. This is further supported by the pH independence of the mutant transporter even when Vmax is massively increased. It is thus conceivable that AMTs have a gate that is defective in the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant. One may also hypothesize that the mutation leads to a conversion from a transporter to a channel mode. Analysis of the ClC family of chloride transporters/channels had suggested a continuum between transporters and channels (22). An alternative might be that the protein has two gates that need to be coordinated to produce saturable transport and that the coordination between the gates is defective in the AMT1;1-Q57H mutant (32). Taken together, the data presented here show that AMTs can exist in multiple states. For a full understanding of AMT function and regulation, it will be important to obtain crystal structures of the different states as recently achieved for the bacterial leucine transporter LeuT (32).

Interestingly, the selectivity of the Q57H mutant also changed with a dramatic increase in the selectivity for ammonium over methylammonium. It would be interesting to test whether the mutations of Phe-215 and Trp-212 in the pore of EcAmt-B, which show reduced methylammonium transport activity lead to increased ammonium conductivity (33).

The extreme conservation of the CCT even in cyanobacteria and archaebacteria has been surprising (25). The data shown here demonstrate that the CCT of the Archaeoglobus AfAmt-2 homolog also functions as a trans-activation domain. Interestingly, defects in the C-terminal trans-activation domain are suppressed specifically by mutations leading to Q53H, Q53E, or Q53K. Gln-53 in AfAmt-2 corresponds to Gln-57 in the Arabidopsis AMT1;1. These findings suggest that the allosteric regulatory mechanism originated early in evolution and has been perfectly retained. It thus appears that selective pressure on maintaining the allosteric regulation has persisted and still operates in bacterial fungi and higher plants. So far, we have not been able to identify a transporter lacking the CCT. Possibly, the regulatory function of the CCT is crucial for survival, because even single nucleotide mutations in residues corresponding to the pore, specifically Q57H, Q57E or Q57K, F60S, I136P, A137P, A137S or A137D, or A138P render the transport activity independent of allosteric trans-activation by the C-terminal trans-activation domain; thus, the C terminus should be free to evolve once a mutation leading to the modifications of at least one of the five residues Gln-57, Phe-60, Ile-136, Ala-137, or Ala-138 in the pore has occurred.

Alternatively, the C terminus could play a crucial role in linking the transporter to nitrogen regulation, as in the case of the Escherichia coli AMTB, which binds a PII-like protein, GlnK, connecting it to a signaling cascade that controls gene expression (34, 35). GlnK binds α-ketoglutarate and ATP/ADP and thus integrates carbon availability and energy status to control ammonium uptake (36). Interestingly, the only plant PII identified so far localizes to the chloroplast and thus does not appear to be available to interact with the plasma membrane AMTs (37, 38). It will be important to identify proteins that interact with the C terminus of the plant AMTs to determine whether a similar signaling mechanism using a different set of interactors exists in plants, which plays a role in signaling or metabolic integration.

Phosphoproteomic studies had shown that the CCT contains an unconventional kinase recognition motif in a surface-exposed loop in the hinge region between intra- and intermolecular interaction domains (25). The conserved residue Thr-460, which is essential for functionality of plant AMTs, was found to be phosphorylated in Arabidopsis cell cultures grown in high ammonium (39). Using a phospho-specific antiserum, we detected phosphorylation of AMT1-T460 in Arabidopsis roots by ammonium in a time- and concentration-dependent manner, thus linking extracellular ammonium levels to transport activity.7 Feedback inhibition of ammonium uptake by ammonium could explain the observation that plants pregrown on different levels of ammonium show a negative correlation between the ammonium levels in preculture and the uptake capacity (5).

To date, crystal structures of the Arabidopsis AMT1;1 and AfAmt-2 proteins are not available; thus, it is not yet possible to define the exact surroundings of the residues identified through suppressor mutants. However, three high-resolution crystal structures of Amt family members (E. coli Amt-B, A. fulgidus Amt-1, and Nitrosomonas europaea Rh50) show striking structural conservation. Amino acid sequence alignments in combination with secondary structure predictions allow tentative localization of the residues in AMT1;1 and AfAmt-2 (supplemental Fig. 3). AMT1;1 shows the highest amino acid sequence identity with AfAmt-1 (36%) and AfAmt-2 (34%) and the lowest with NeRh50 (17 and 13%, respectively). The residue corresponding to Gln-57 (AMT1;1) and Gln-53 (AfAmt-2) is Val-20 of AfAmt-1; Thr-100 corresponds to Ala-138 (AMT1;1). Both residues are located in close proximity of each other in TMH I and III, approximately in the middle of the membrane (supplemental Fig. 4). TMH I and III contribute to the predicted ammonium transport pathway of the pore. Interactions of residues Val-20 and Thr-100 with the rest of the protein are restricted to the neighboring amino acid residues from THM I, II, and III (supplemental Fig. 4). Furthermore, Ala-138 of the Arabidopsis AMT1 is located in the vicinity of the phenylalanine residue Phe-134, which is thought to form a gate for substrate transport (Phe-96 in AfAmt-1). Previous studies on EcAmt-B had shown that double point mutations of these two phenylalanine residues to alanine, despite yielding a visibly open pore, result in reduced MeA transport activity (33). It will be interesting to see whether the mutations also lead to increased ammonium transport.

AMTs appear to be kept in a restricted state that allows for high affinity/low capacity ammonium uptake. Mutations in residues corresponding to the pore region, mainly below the phenylalanine gate, can relieve this “restriction” and allow for high capacity transport. These mutations also overcome the dependence on allosteric trans-activation by the C terminus, thus linking gating to allosteric control, potentially to protect against ammonium toxicity. Crystal structures of AMTs and mutants in different states will be invaluable tools for unraveling the transport mechanism of this important class of transporters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Sylvie Lalonde (Carnegie Institution, Stanford University) for phylogenetic analyses and preparation of the WEBLogo presentation.

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Arabidopsis 2010 Program Grant MCB-0618402 (to W. B. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. 1–4.

V. Lanquar, D. Loque, F. Hörmann, S. Lalonde, N. von Wiren, and W. B. Frommer, submitted for publication.

- MeA

- methylammonium

- CCT

- cytosolic C-terminus

- TMH

- transmembrane helix

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hess D. C., Lu W., Rabinowitz J. D., Botstein D. (2006) PLoS Biol. 4, e351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szczerba M. W., Britto D. T., Ali S. A., Balkos K. D., Kronzucker H. J. (2008) J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3415–3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper A. J., Plum F. (1987) Physiol. Rev. 67, 440–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meijer A. J., Lamers W. H., Chamuleau R. A. F. M. (1990) Physiol. Rev. 70, 701–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M. Y., Glass A., Shaff J. E., Kochian L. V. (1994) Plant Physiol. 104, 899–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachtman D. P., Schroeder J. I., Lucas W. J., Anderson J. A., Gaber R. F. (1992) Science 258, 1654–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakhoul N. L., Hering-Smith K. S., Abdulnour-Nakhoul S. M., Hamm L. L. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281, F255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loqué D., Ludewig U., Yuan L., von Wirén N. (2005) Plant Physiol. 137, 671–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holm L. M., Jahn T. P., Møller A. L., Schjoerring J. K., Ferri D., Klaerke D. A., Zeuthen T. (2005) Pflugers Arch. 450, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubois E., Grenson M. (1979) Mol. Gen. Genet. 175, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan L., Loqué D., Kojima S., Rauch S., Ishiyama K., Inoue E., Takahashi H., von Wirén N. (2007) Plant Cell 19, 2636–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loqué D., Yuan L., Kojima S., Gojon A., Wirth J., Gazzarrini S., Ishiyama K., Takahashi H., von Wirén N. (2006) Plant J. 48, 522–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ninnemann O., Jauniaux J. C., Frommer W. B. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 3464–3471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marini A. M., Vissers S., Urrestarazu A., André B. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 3456–3463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludewig U., Wilken S., Wu B., Jost W., Obrdlik P., El Bakkoury M., Marini A. M., André B., Hamacher T., Boles E., von Wirén N., Frommer W. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45603–45610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer M., Dynowski M., Ludewig U. (2006) Biochem. J. 396, 431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khademi S., O'Connell J., 3rd, Remis J., Robles-Colmenares Y., Miercke L. J., Stroud R. M. (2004) Science 305, 1587–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong R. N., Kim K. S., Yoshihara C., Inwood W. B., Kustu S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18706–18711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrade S. L., Einsle O. (2007) Mol. Membr. Biol. 24, 357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faham S., Watanabe A., Besserer G. M., Cascio D., Specht A., Hirayama B. A., Wright E. M., Abramson J. (2008) Science 321, 810–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita A., Singh S. K., Kawate T., Jin Y., Gouaux E. (2005) Nature 437, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller C., Nguitragool W. (2009) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 364, 175–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrade S. L., Dickmanns A., Ficner R., Einsle O. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14994–14999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng L., Kostrewa D., Bernèche S., Winkler F. K., Li X. D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17090–17095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loqué D., Lalonde S., Looger L. L., von Wirén N., Frommer W. B. (2007) Nature 446, 195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–33402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gietz D., St. Jean A., Woods R. A., Schiestl R. H. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludewig U., von Wirén N., Frommer W. B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13548–13555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludewig U. (2004) J. Physiol. 559, 751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burckhardt B. C., Burckhardt G. (1997) Pflügers Arch 434, 306–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuhäuser B., Dynowski M., Mayer M., Ludewig U. (2007) Plant Physiol. 143, 1651–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gouaux E. (2009) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 364, 149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javelle A., Lupo D., Ripoche P., Fulford T., Merrick M., Winkler F. K. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5040–5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blakey D., Leech A., Thomas G. H., Coutts G., Findlay K., Merrick M. (2002) Biochem. J. 364, 527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay P. L., Hallenbeck P. C. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 71, 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg J., Hung Y. P., Yellen G. (2009) Nat. Methods 6, 161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsieh M. H., Lam H. M., van de Loo F. J., Coruzzi G. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13965–13970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuno Y., Berenger B., Moorhead G. B., Ng K. K. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 1477–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nühse T. S., Stensballe A., Jensen O. N., Peck S. C. (2004) Plant Cell 16, 2394–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.