Abstract

Protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3Rs) represents a mechanism for shaping intracellular Ca2+ signals following a concomitant elevation in cAMP. Activation of PKA results in enhanced Ca2+ release in cells that express predominantly InsP3R2. PKA is known to phosphorylate InsP3R2, but the molecular determinants of this effect are not known. We have expressed mouse InsP3R2 in DT40-3KO cells that are devoid of endogenous InsP3R and examined the effects of PKA phosphorylation on this isoform in unambiguous isolation. Activation of PKA increased Ca2+ signals and augmented the single channel open probability of InsP3R2. A PKA phosphorylation site unique to the InsP3R2 was identified at Ser937. The enhancing effects of PKA activation on this isoform required the phosphorylation of Ser937, since replacing this residue with alanine eliminated the positive effects of PKA activation. These results provide a mechanism responsible for the enhanced Ca2+ signaling following PKA activation in cells that express predominantly InsP3R2.

Hormones, neurotransmitters, and growth factors stimulate the production of InsP33 and Ca2+ signals in virtually all cell types (1). The ubiquitous nature of this mode of signaling dictates that this pathway does not exist in isolation; indeed, a multitude of additional signaling pathways can be activated simultaneously. A prime example of this type of “cross-talk” between independently activated signaling systems results from the parallel activation of cAMP and Ca2+ signaling pathways (2, 3). Interactions between these two systems occur in numerous distinct cell types with various physiological consequences (3–6). Given the central role of InsP3R in Ca2+ signaling, a major route of modulating the spatial and temporal features of Ca2+ signals following cAMP production is potentially through PKA phosphorylation of the InsP3R isoform(s) expressed in a particular cell type.

There are three InsP3R isoforms (InsP3R1, InsP3R2, and InsP3R3) expressed to varying degrees in mammalian cells (7, 8). InsP3R1 is the major isoform expressed in the nervous system, but it is less abundant compared with other subtypes in non-neuronal tissues (8). Ca2+ release via InsP3R2 and InsP3R3 predominate in these tissues. InsP3R2 is the major InsP3R isoform in many cell types, including hepatocytes (7, 8), astrocytes (9, 10), cardiac myocytes (11), and exocrine acinar cells (8, 12). Activation of PKA has been demonstrated to enhance InsP3-induced Ca2+ signaling in hepatocytes (13) and parotid acinar cells (4, 14). Although PKA phosphorylation of InsP3R2 is a likely causal mechanism underlying these effects, the functional effects of phosphorylation have not been determined in cells unambiguously expressing InsP3R2 in isolation. Furthermore, the molecular determinants of PKA phosphorylation of this isoform are not known.

PKA-mediated phosphorylation is an efficient means of transiently and reversibly regulating the activity of the InsP3R. InsP3R1 was identified as a major substrate of PKA in the brain prior to its identification as the InsP3R (15, 16). However, until recently, the functional consequences of phosphorylation were unresolved. Initial conflicting results were reported indicating that phosphoregulation of InsP3R1 could result in either inhibition or stimulation of receptor activity (16, 17). Mutagenic strategies were employed by our laboratory to clarify this discrepancy. These studies unequivocally assigned phosphorylation-dependent enhanced Ca2+ release and InsP3R1 activity at the single channel level, through phosphorylation at canonical PKA consensus motifs at Ser1589 and Ser1755. The sites responsible were also shown to be specific to the particular InsP3R1 splice variant (18). These data were also corroborated by replacing the relevant serines with glutamates in a strategy designed to construct “phosphomimetic” InsP3R1 by mimicking the negative charge added by phosphorylation (19, 20). Of particular note, however, although all three isoforms are substrates for PKA, neither of the sites phosphorylated by PKA in InsP3R1 are conserved in the other two isoforms (21). Recently, three distinct PKA phosphorylation sites were identified in InsP3R3 that were in different regions of the protein when compared with InsP3R1 (22). To date, no PKA phosphorylation sites have been identified in InsP3R2.

Interactions between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling pathways are evident in exocrine acinar cells of the parotid salivary gland. In these cells, both signals are important mediators of fluid and protein secretion (23). Multiple components of the [Ca2+]i signaling pathway in these cells are potential substrates for modulation by PKA. Previous work from this laboratory established that activation of PKA potentiates muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-induced [Ca2+]i signaling in mouse and human parotid acinar cells (4, 24, 25). A likely mechanism to explain this effect is that PKA phosphorylation increases the activity of InsP3R expressed in these cells. Consistent with this idea, activation of PKA enhanced InsP3-induced Ca2+ release in permeabilized mouse parotid acinar cells and also resulted in the phosphorylation of InsP3R2 (4).

Invariably, prior work examining the functional effects of PKA phosphorylation on InsP3R2 has been performed using cell types expressing multiple InsP3R isoforms. For example, AR4-2J cells are the preferred cell type for examining InsP3R2 in relative isolation, because this isoform constitutes more than 85% of the total InsP3R population (8). InsP3R1, however, contributes up to ∼12% of the total InsP3R in AR4-2J cells. An initial report using InsP3-mediated 45Ca2+ flux suggested that PKA activation increased InsP3R activity in AR4-2J cells (21). A similar conclusion was made in a later study, which documented the effects of PKA activation on agonist stimulated Ca2+ signals in AR4-2J cells (26). Any effects of phosphorylation observed in these experiments could plausibly have resulted from phosphorylation of the residual InsP3R1.

Although PKA enhances InsP3-induced calcium release in cells expressing predominantly InsP3R2, including hepatocytes, parotid acinar cells, and AR4-2J cells (4, 13, 21, 26, 27), InsP3R2 is not phosphorylated at stoichiometric levels by PKA (21). This observation has called into question the physiological significance of PKA phosphorylation of InsP3R2 (28). The apparent low levels of InsP3R2 phosphorylation are clearly at odds with the augmented Ca2+ release observed in cells expressing predominantly this isoform. The equivocal nature of these findings probably stems from the fact that, to date, all of the studies demonstrating positive effects of PKA activation on Ca2+ release were conducted in cells that also express InsP3R1. The purpose of the current experiments was to analyze the functional effects of phosphorylation on InsP3R2 expressed in isolation on a null background. We report that InsP3R2 activity is increased by PKA phosphorylation under these conditions, and furthermore, we have identified a unique phosphorylation site in InsP3R2 at Ser937. In total, these results provide a direct mechanism for the cAMP-induced activation of InsP3R2 via PKA phosphorylation of InsP3R2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

cDNA Expression Constructs

Mouse InsP3R2 cDNA, a kind gift of Dr. Katsuhiko Mikoshiba (Riken, Japan), was used as the template for creation of EGFP-tagged subclones (29). All fragments were amplified by PCR with MluI and NotI restriction sites incorporated into the N termini and C termini, respectively. A BssHII site was incorporated into the N terminus of fragment 3 because of an internal MluI site in this fragment. PCR products were ligated with MluI- and NotI-digested pCI-Neo-EGFP (a kind gift from Dr. Sundeep Malik, University of Rochester) to create the mammalian expression vectors. The full-length rat InsP3R2 in the expression vector pCMV5 was a kind gift of Dr. Suresh Joseph (Thomas Jefferson University). A Kozak initiation motif was engineered into the receptor DNA using PCR. The modified receptor DNA was then cloned into the pEF6/V5-His Topo TA expression vector (Invitrogen).

Mutagenesis

All point mutations in the InsP3R2 fragments were created using QuikChange XL or QuikChange multisite mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Point mutations in the full-length InsP3R2 expression constructs to allow S937A and S2633A amino acid substitutions were constructed using a two-step QuikChange mutagenesis strategy (30).

DT40 Cell Lines

The cDNA construct for 3× hemagglutinin-tagged human type-3 muscarinic receptor (M3R) and wild type and mutated InsP3R2 constructs were linearized with MfeI. Linearized constructs were introduced into DT40-3KO cells, which are devoid of InsP3R, by nucleofection using an Amaxa nucleofector as described previously (31–33). After nucleofection, the cells were incubated in growth medium for 24 h prior to dilution in selection medium containing 2 mg/ml Geneticin. Cells were then seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates at ∼1000 cells/well and incubated in selection medium for at least 7 days. Wells exhibiting growth after the selection period were picked for expansion.

Phosphorylation of InsP3R2 in Intact Cells

COS-7 cells were transfected with InsP3R2 expression constructs 36–40 h prior to labeling with 32PO4− for 2 h in phosphate-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. ∼150 μCi were added to 1 ml of phosphate-free media in each well of a 6-well culture dish. After labeling, cells were washed three times in Tris-buffered saline, treated with forskolin for 15 min, and lysed in lysis buffer (10 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 100 mm NaF, 1 EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Science). Lysates were cleared with pansorbin prior to incubation with immunoprecipitation antibody for 2 h. Protein A/G beads were then added for 1 h. The beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were separated by PAGE on 5% polyacrylamide, and the gels were dried for phosphorimaging using a phosphor storage screen (Amersham Biosciences) and Amersham Biosciences PhosphorImager.

PKA Phosphorylation of InsP3R in Vitro

COS-7 cells were transfected with wild type or mutated InsP3R2 expression constructs 36–40 h before harvest. Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline prior to suspension in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche Applied Science). Cells were dispersed using a cell scraper (Corning Glass) and allowed to incubate on ice for 20 min. Lysates were cleared with pansorbin prior to incubation with immunoprecipitation antibody for 2 h. Protein A/G beads were then added for 1 h. The beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and three times in PKA phosphorylation buffer (120 mm KCl, 50 mm Tris, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.3 mm MgCl2, pH 7.2) and resuspended in phosphorylation buffer.

20 units of purified recombinant PKA (Promega) were added to the samples along with [γ-32P]ATP (∼5 μCi/reaction) and 0.5 μm unlabeled ATP. Kinase reactions were incubated for 0–15 min, and the beads were washed six times in lysis buffer prior to resuspension and SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with BioSafe Coomassie (Bio-Rad) and subsequently dried down for phosphorimaging. 32P signals were detected by phosphorimaging as described above.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies designed against a specific sequence in the rat InsP3R2 extreme C terminus (α-InsP3R2-CT; 2686GFLGSNTPHENHHMPPH2702) were generated by Pocono Rabbit Farms & Laboratories (Canadensis, PA). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against the region surrounding phosphorylated Ser937 of mouse InsP3R2 (934SRGpSIFPVSVPDAC946, where pS represents phosphoserine) was generated by Quality Controlled Biochemicals (Hopkinton, MA).

Phosphorylation of InsP3R2 Serine 937 in COS-7 Cells and Mouse Parotid Acinar Cells

Mouse parotid acinar cells were isolated by collagenase digestion, as described previously (4). COS-7 cells or mouse parotid acinar cells were treated with 10 μm forskolin and 100 μm IBMX for 15 min. Cell lysates were harvested in lysis buffer supplemented with 100 nm okadaic acid. InsP3R2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using α-InsP3R2-CT. Where noted, some immunoprecipitated samples were treated with 10 units of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) at 37 °C for 1 h. Samples were separated on SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated serine 937 was detected with α-Ser(P)937 by Western blotting. Blots were stripped and reprobed with α-InsP3R2-CT to verify equal amounts of total immunoprecipitated InsP3R2.

Digital Imaging of Intracellular Ca2+ in DT40 Cells

DT40 cells were loaded with 2 μm of the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fura-2 AM at room temperature for 15–30 min. Fura-2-loaded cells were allowed to adhere to a glass coverslip at the bottom of a perfusion chamber. Cells were perfused in HEPES-buffered physiological saline containing 137 mm NaCl, 0.56 mm MgCl2, 4.7 mm KCl, 1 mm Na2HPO4, 10 mm HEPES, 5.5 mm glucose, and 1.26 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4. Imaging was performed using an inverted Nikon microscope through a ×40 oil immersion objective lens (numerical aperture, 1.3). Fura-2-loaded cells were excited alternately with light at 340 and 380 nm by using a monochrometer-based illumination system (TILL Photonics), and the emission at 510 nm was captured by using a digital frame transfer CCD camera. In experiments where InsP3R or M3R were transiently expressed, cDNA encoding HcRed was included to indicate transfected cells. HcRed fluorescence was detected by excitation at 560 nm and observing the emission at >600 nm.

Single Channel Recordings

Whole cell patch clamp recordings of single InsP3R2 channel activity present in the plasma membrane (34, 35) were made from DT40-3KO cells stably expressing mouse InsP3R2. K+ was utilized as the charge carrier in all experiments, and free Ca2+ was clamped at 200 nm to favor activation of InsP3R (bath: 140 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 500 μm BAPTA, free Ca2+ 250 nm (pH 7.1); pipette: 140 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 100 μm BAPTA, 200 nm free Ca2+, 5 mm Na2-ATP unless otherwise noted (pH 7.1)). Borosilicate glass pipettes were pulled and fire-polished to resistances of about 20 megaohms. Following establishment of stable high resistance seals, the membrane patches were ruptured to form the whole cell configuration with resistances >5 gigaohms and capacitances of >8 picofarads. Currents were recorded under voltage clamp conditions at −100 mV using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp 9. Channel recordings were digitized at 20 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz with a −3 dB, 4-pole Bessel filter. Activity was typically evident essentially immediately following breakthrough with InsP3 in the pipette. Analyses were performed using the event detection protocol in Clampfit 9. Channel openings were detected by half-threshold crossing criteria. We assumed that the number of channels in any particular cell is represented by the maximum number of discrete stacked events observed during the experiment. The single channel open probability (Po) was calculated using the multimodal distribution for the open and closed current levels.

RESULTS

Activation of PKA Enhances Ca2+ Signaling in DT40-M3 Cells Expressing Mouse InsP3R2

Analyzing subtype-specific regulation of individual InsP3R isoforms in native tissue is hampered by the fact that most mammalian cell types express multiple isoforms and that the functional receptors can form heterotetrameric channels (36–38). Given these limitations, the functional properties of specific homotetrameric receptors must be determined in a defined system. Kurosaki and colleagues (40) developed such a system based on the DT40 chicken B-cell precursor line by creating a null background (DT40-3KO cells) following elimination of all three InsP3R isoforms through homologous recombination (39, 40). In order to examine the effects of PKA phosphorylation on InsP3R2, we transiently expressed this isoform in a DT40-3KO cell line (DT40-M3) stably expressing the human M3R (33).

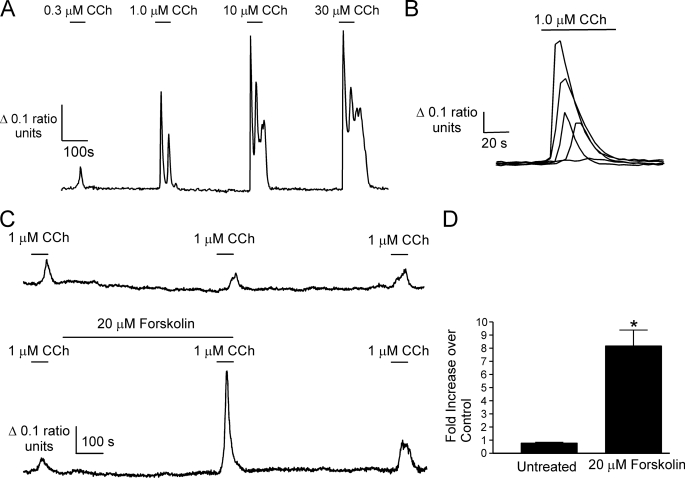

DT40-M3 cells transfected with mouse InsP3R2 cDNA, identified by expression of HcRed, responded to the muscarinic agonist carbachol (CCh) stimulation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Treatment with 1 μm CCh produced Ca2+ signals with a range of amplitudes, presumably as a consequence of a range of InsP3R2 expression levels following transient transfection (Fig. 1B). Cells that responded to 1 μm CCh with amplitudes no greater than 0.2 340 nm/380 nm ratio units were used for the purposes of analyzing the effects of raising cAMP. An example of a DT40-M3 cell expressing mouse InsP3R2 and treated three times with 1 μm CCh is shown in Fig. 1C. Treatment of cells with 20 μm forskolin after the first CCh treatment resulted in Ca2+ transients with >5-fold larger amplitudes as shown in Fig. 1C, indicating that activation of PKA enhances Ca2+ release from InsP3R2. This effect was only evident in cells that responded submaximally to 1 μm CCh. As previously observed, forskolin induced a rise in [Ca2+]i in some cells (27). This effect was evident in ∼50% of cells from six separate experiments, and these cells were excluded from analysis. The mechanism underlying this effect is presently unknown; however, it is independent of InsP3R as it occurs in DT40-3KO cells at approximately the same frequency. The activation of PKA by this treatment had clear enhancing effects on the Ca2+ signal (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Forskolin enhances CCh-evoked Ca2+ responses in DT40-M3 cells expressing mouse InsP3R2. An expression construct harboring cDNA for mouse InsP3R2 was introduced into DT40-M3 cells. A, a representative Fura-2 recording from a single cell showing increasing Ca2+-transient amplitudes with increasing CCh concentrations. B, the range of Ca2+ signal amplitudes observed in five cells from a single experiment to stimulation with 1 μm CCh. C, upper trace, a Fura-2 recording from a DT40-M3 cell expressing mouse InsP3R2 stimulated three times with 1 μm CCh (n = 3 experimental runs). Lower trace, the effect of raising cAMP with forskolin on a 1 μm CCh-evoked Ca2+ transient (n = 5 experimental runs). D, pooled data from the indicated number of experiments comparing the second 1 μm CCh treatment with the first in the absence and presence of forskolin (*, p ≤ 0.05, Student's unpaired t test).

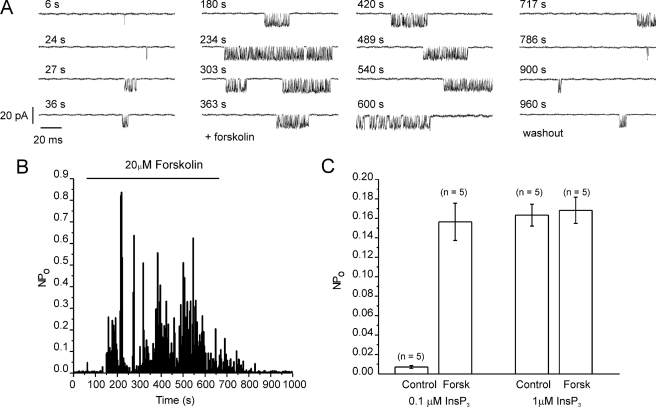

We also obtained additional evidence that PKA-induced phosphorylation results in increased InsP3R2 activity by examining the effects of activating PKA on the single channel activity of InsP3R2. Single InsP3R2 measurements were conducted using whole cell recordings of plasma membrane-resident InsP3R2 in DT40 cells stably expressing InsP3R2 (20, 31, 34, 35, 41). This configuration allows the monitoring of single InsP3R channels during the activation of endogenous PKA following exposure to forskolin (20). Fig. 2A shows an example of channel activity when low concentrations of InsP3 (100 nm) were included in the recording pipette. No channel activity is observed in this preparation in the absence of InsP3 or in DT40-3KO cells devoid of InsP3R (31). The open probability of the channel was markedly enhanced following exposure to forskolin (Fig. 2, B (diary plot for representative cell) and C (pooled data)). InsP3R2 channel activity returned to pre-PKA activation levels following washout of forskolin. Enhanced channel activity was readily evident at threshold [InsP3] but not observed at higher levels of InsP3 (1 μm; Fig. 2C). In total, these data provide clear evidence that activation of PKA results in enhanced Ca2+ release through increased activity of InsP3R2.

FIGURE 2.

Activation of PKA results in increased InsP3R2 single channel activity. Whole cell patch clamp recordings were made in DT40-3KO cells stably expressing InsP3R2. A, representative sweeps from cells at a holding potential of −100 mV. Channel activity is observed with 100 nm InsP3 in the patch pipette. The activity is markedly enhanced following exposure to forskolin, which was applied at 60 s and removed at 660 s, as indicated by the bar in B. B, a diary plot of activity during each sweep. C, pooled data from experiments with both 100 nm and 1 μm InsP3.

PKA Phosphorylates Mouse InsP3R2 at Serine 937

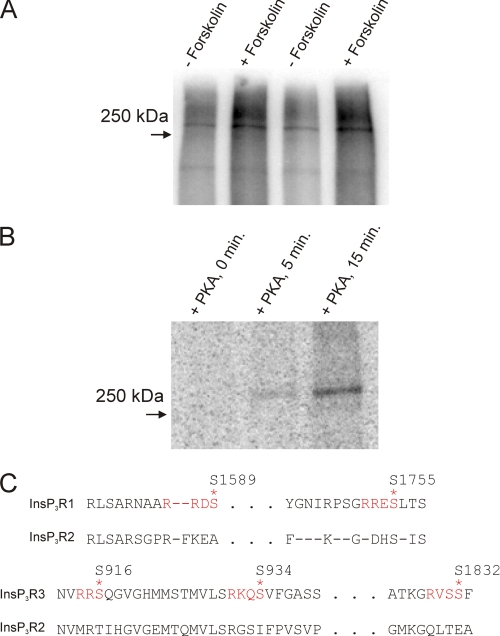

A likely mechanism for the positive effects of increasing cAMP on the Ca2+ signal is through direct phosphorylation of InsP3R2 by PKA. Because this signaling system is a rich source of potential PKA substrates, we cannot, however, discount other effects of PKA on the M3R-induced Ca2+ signals. Potential loci might include effects on InsP3 levels, Ca2+ clearance, or Ca2+ entry. In addition, cAMP at millimolar concentrations was recently reported to enhance Ca2+ release from InsP3R2 by a mechanism that did not require PKA activity (42). Establishing the PKA phosphorylation site(s) and subsequently performing mutagenesis of the putative sites in InsP3R2 are required to definitively rule out these and other possible mechanisms for the increased Ca2+ signal. Although PKA has been shown to phosphorylate InsP3R2 in a number of studies by independent groups (21, 26, 28), the site(s) of phosphorylation are not known. Experiments were performed following transient overexpression of InsP3R2 in COS-7 cells. This expression system was chosen because of low endogenous levels of InsP3R and the high transfection efficiency such that expressed receptor can be readily distinguished from endogenous protein (see supplemental Fig. S1). In addition, expressed receptors rarely form heterotetramers with endogenous InsP3R (43). Fig. 3 and the supplemental material confirm that InsP3R2 is a substrate for PKA. Both mouse and rat InsP3R2 were phosphorylated in intact cells (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1) and in vitro (Fig. 3B). Fig. 3C shows alignments of mammalian InsP3R protein sequences around the known phosphorylation sites in InsP3R1 and InsP3R3. None of these sites are conserved in InsP3R2 sequences, indicating that the phosphorylation evident in Fig. 3, A and B, occurs at a novel PKA phosphorylation site(s).

FIGURE 3.

Mammalian InsP3R2 is phosphorylated in response to raising cAMP in metabolically labeled COS-7 cells and in vitro by purified PKA. COS-7 cells were transfected with mouse InsP3R2 cDNA (A). 36 h after transfection, cells were metabolically labeled with 32PO4− prior to forskolin treatment, immunoprecipitation, and PAGE. A, phosphor image of a dried gel loaded with samples from mouse InsP3R2-expressing cells. Greater 32P incorporation into a ∼250 kDa band in the forskolin-treated transfected samples indicated phosphorylation of InsP3R2. B, mouse InsP3R2 was immunoprecipitated from COS-7 cells and incubated with purified PKA at 37 °C in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for the indicated times. Results are representative of at least two separate experiments for each condition. C, alignments of InsP3R sequences around the PKA phosphorylation sites in InsP3R1 and InsP3R3. None of the sites present in these isoforms are present in InsP3R2.

Optimal PKA phosphorylation sites are serines or threonines preceded by basic residues at the −2- and −3-positions (44). The primary amino acid sequences of individual mammalian InsP3R2 proteins combined harbor greater than 300 serine and threonine residues. Of these potential candidates, ∼30 have basic residues (arginine or lysine) upstream of the putative target serine or threonine. The single canonical PKA consensus sequence located in InsP3R2 (RRPS2508) is probably not accessible to the kinase, because it is located on the luminal side of the putative permeability (P) loop. Given the large number of potential putative PKA phosphorylation sites present in the primary sequence of InsP3R2, we developed a subcloning approach to identify novel PKA phosphorylation sites.

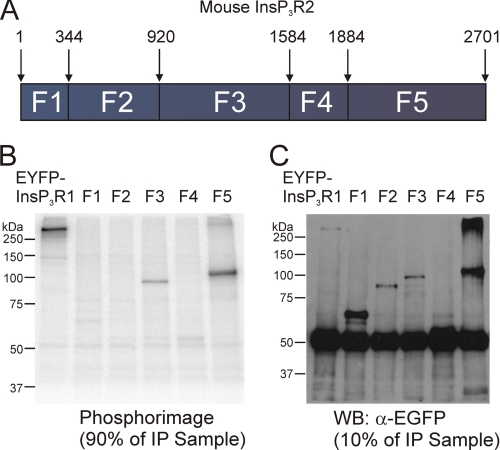

Limited trypsin digestion of InsP3R1 and InsP3R3 has established that InsP3R can be divided into five (in the case of InsP3R1) or four (in the case of InsP3R3) globular domains with intervening solvent-exposed trypsin digestion sites (22, 45, 46). In order to maintain domain structure as much as possible, InsP3R2 subclones were designed to correspond with predicted limited trypsin digestion products. The InsP3R2 sequence was therefore divided into five smaller fragment constructs with EGFP as an epitope tag on the N terminus of each fragment. As depicted in Fig. 4A, fragment 1 corresponded with residues 1–343, fragment 2 with residues 344–919, fragment 3 with residues 920–1583, fragment 4 with residues 1584–1883, and fragment 5 with residues 1884–2701.

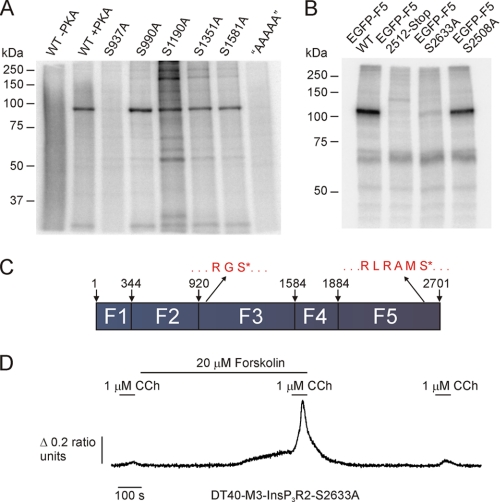

FIGURE 4.

PKA phosphorylates two different fragments of mouse InsP3R2. A, a schematic diagram depicting the boundaries of the fragments used to identify PKA-phosphorylated residues in mouse InsP3R2. The predicted sizes of the EGFP-tagged subclones are as follows: EGFP-F1, ∼65 kDa; EGFP-F2, ∼94 kDa; EGFP-F3, ∼102 kDa; EGFP-F4, ∼60 kDa; EGFP-F5, ∼120 kDa. EGFP-tagged subclones of mouse InsP3R2 were expressed in COS-7 cells, immunoprecipitated, and then subjected to in vitro PKA assays prior to PAGE. B, phosphor image from 90% of the immunoprecipitated sample. 32P was incorporated into samples containing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-InsP3R1, EGFP-fragment 3, and EGFP-fragment 5. C, a Western blot with the remaining 10% of the immunoprecipitated samples from B probed with α-GFP. Bands of the appropriate sizes indicate the successful immunoprecipitation of all five fragments.

Constructs coding for the five fragments were transfected into COS-7 cells and immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against EGFP. A separate sample was transfected with a construct coding for enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-tagged InsP3R1 and served as a positive control. Immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to in vitro PKA kinase assays, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Samples were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and 32P incorporation was determined by phosphorimaging. 32P was incorporated into the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-InsP3R1 samples as well as into samples from cells expressing fragment 3 and fragment 5 (Fig. 4B). Fig. 4C shows a Western blot probed with α-GFP antibody of the various fragments. Fragment 4, which contains a putative PKA phosphorylation site (KKDS1687) did not incorporate 32P under these conditions (Fig. 4B). Because fragment 4 was somewhat weakly expressed compared with the other fragments, these data do not formally rule out the possibility that a functional PKA-phosphorylation site is present in this domain (but see subsequent functional data). Nevertheless, these results indicate that PKA phosphorylation sites in InsP3R2 are probably harbored between residues 920 and 1583 and between residues 1884 and 2701 (Fig. 4A).

There are 5 serine residues present on fragment 3. Each of these serines was mutated to an alanine in isolation. Mutated fragment 3 was also generated with all 5 serines replaced with alanines. Immunoprecipitated wild type and mutated fragment 3 fusion proteins were subjected to in vitro PKA kinase reactions. The serine-free fragment 3 protein did not incorporate 32P (Fig. 5A). PKA phosphorylation was also completely eliminated by mutation of Ser937 alone (Fig. 5A). An arginine precedes Ser937 at position 935, fulfilling the minimum requirement for a PKA phosphorylation site. Ser937 is unique to InsP3R2, and it is present in all InsP3R2 sequences in the NCBI databases, thus making it a promising candidate serine for physiological PKA phosphorylation. Furthermore, the corresponding region in InsP3R3 contains two of the three PKA phosphorylation sites (Ser916 and Ser934), making fragment 3 a likely common region for modulation. Two candidate PKA phosphorylation sites present in the sequence for InsP3R2-fragment 5 corresponding to Ser2508 and Ser2633 in the full-length sequence were also mutated. Fig. 5B shows the results from in vitro PKA reactions with these mutations along with a fragment 5 fusion truncated at position 2512. Kinase reactions with the truncation mutant or the S2633A mutant failed to result in 32P incorporation, whereas phosphorylation was unaffected by the S2508A mutation, indicating that the PKA phosphorylation site on fragment 5 occurs exclusively at Ser2633.

FIGURE 5.

PKA phosphorylates fragment 3 of mouse InsP3R2 at Ser937 and fragment 5 at Ser2633. Mutants in InsP3R2 fragment 3 were generated corresponding to Ser937, Ser990, Ser1190, Ser1351, and Ser1581. Another mutant harboring all five mutations was also generated (AAAAA). A, the phosphor image from an in vitro PKA assay with wild type, S937A, S990A, S1190A, S1351A, S1581A, and “AAAAA” mutated fragment 3 fusions. PKA phosphorylated all fragments except S937A and “AAAAA,” indicating that Ser937 is the sole PKA phosphorylation site in fragment 3 of mouse InsP3R2. Mutations in fragment 5 corresponding to S2508A, a truncation at 2512, and S2633A were generated. B, phosphor image from an in vitro PKA assay with these samples. PKA phosphorylated the wild type and S2508A mutated fragment 5 fusions but failed to phosphorylate the truncated or S2633A mutated fusions. C, schematic diagram depicting the positions of the Ser937 and Ser2633 phosphorylation sites in the context of the full-length mouse InsP3R2. D shows that, following PKA activation, Ca2+ signals are still augmented in cells expressing InsP3R2 S2633A.

Serine 2633 is located in a consensus Akt phosphorylation site (RMRAMS2633), and this putative Akt phosphorylation site is present in all three InsP3R isoforms. Ser2633 has also been identified as a bona fide Akt phosphorylation site in InsP3R1 by two groups (47, 48). This site is, however, unlikely to represent a PKA site in the context of the full-length InsP3R2, since mutation of the known PKA phosphorylation sites in InsP3R1 and InsP3R3 completely eliminated PKA-induced 32P incorporation in vitro and in intact cells (22, 49). Presumably, expression of the truncated receptor renders Ser2633 more accessible to PKA. This could result from an altered conformation of the truncated protein. Regardless of whether Ser2633 is a substrate of PKA in the full-length receptor, Ca2+ release was still increased in cells expressing S2633A mutated InsP3R2 following PKA activation in DT40-M3 cells (Fig. 5D).

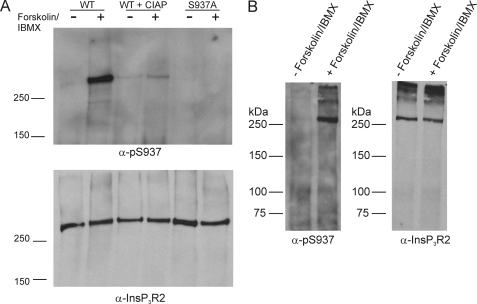

The sequence surrounding Ser937 shows considerable divergence from InsP3R1 and InsP3R3, making the region attractive for the design of a phospho-specific antibody. Similar strategies have been used to produce antibodies recognizing phosphorylated residues in InsP3R1 and InsP3R3 (22, 50). We designed an antibody to specifically recognize phosphorylated Ser937 in InsP3R2 (α-Ser(P)937). This antibody failed to recognize InsP3R2 immunoprecipitated from untreated COS-7 cells; however, the antibody readily reported a band in samples immunoprecipitated from forskolin-treated cells (Fig. 6A). Importantly, no signal was detected in parallel samples that were treated with alkaline phosphatase following immunoprecipitation. These data indicate that antibody recognition requires the presence of a phosphate group. Similarly, no signal was detected in samples immunoprecipitated from forskolin/IBMX-treated cells expressing S937A mutated InsP3R2. These results clearly show that mouse InsP3R2 can be phosphorylated at Ser937 by endogenous PKA, further enforcing the idea that InsP3R2 is a physiological substrate of PKA.

FIGURE 6.

PKA phosphorylates full-length mouse InsP3R2 at Ser937. Wild type and S937A mutated full-length mouse InsP3R2 were expressed in COS-7 cells. The cells were treated with forskolin and IBMX, and InsP3R2 proteins were immunoprecipitated and separated by PAGE. A, results of a Western blot probed with α-Ser(P)937. The antibody recognized a band at the appropriate size in the wild type sample but not in a parallel sample treated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase prior to PAGE. The antibody also failed to recognize a band in the S937A mutant sample. The lower panel shows a Western blot on the same membrane after stripping and reprobing with an α-InsP3R2 antibody, indicating equal expression in all samples. B, parotid acinar cells were isolated from mice and left untreated or treated with forskolin + IBMX. InsP3R2 was immunoprecipitated from the samples and separated by PAGE. The left panel shows a Western blot of samples probed with α-Ser(P)937. The antibody recognizes an appropriate band in the forskolin/IBMX-treated sample. The right panel shows a Western blot from the same membrane after stripping and reprobing with an antibody against InsP3R2.

These data demonstrating that PKA phosphorylates InsP3R2 at Ser937 were obtained using overexpressed recombinant InsP3R2. In order to determine if PKA can phosphorylate endogenous InsP3R2, we also probed for phosphorylation of Ser937 in InsP3R2 immunoprecipitated from mouse parotid acinar cells. We have demonstrated previously that forskolin treatment induces the apparent phosphorylation of InsP3R2 (4). In these experiments, InsP3R2 was detected in samples immunoprecipitated from forskolin-treated cells with an anti-phospho-Ser/Thr antibody. This experimental paradigm could not formally rule out the possibility that the apparent detection of phosphorylated InsP3R2 was the result of co-immunoprecipitation of non-phosphorylated InsP3R2 originally present in a heterotetrameric complex with phosphorylated InsP3R1. As shown in Fig. 6B, the α-Ser(P)937 antibody clearly recognized phosphorylated InsP3R2 in samples that were immunoprecipitated from forskolin/IBMX-treated parotid acinar cells but not in untreated cells. These results provide strong evidence that PKA phosphorylates endogenously expressed InsP3R2 at Ser937.

Replacement of Serine 937 with Alanine Eliminates the Enhancing Effects of PKA on InsP3R2

The results described above clearly demonstrate that PKA phosphorylates InsP3R2 at Ser937. We next sought to determine if this site is responsible for the positive effects of raising cAMP illustrated in Fig. 1. We generated a stable cell line expressing InsP3R2-S937A and compared the effects of PKA activation on Ca2+ signals with those of a cell line stably expressing wild type InsP3R2 (31). The cell lines were transiently transfected with the M3R to allow repeated stimulations with CCh. In these experiments, we utilized 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d- ribofuranosylbenzylimadazole-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate (cBIMPs), a specific, highly cell-permeable cAMP analogue, to activate PKA. Unlike forskolin, this treatment did not alter the basal Ca2+ levels. Application of cBIMPs resulted in enhanced Ca2+ signals in response to low [CCh] (Fig. 7A). The enhancing effects of cBIMPs were only evident in cells that responded minimally to CCh, indicating that PKA sensitizes InsP3R2 to low levels of stimulation. This effect was manifested as either a potentiation of a minimal response or alternatively generation of a response following cBIMPs incubation, which was not previously evident in the absence of PKA activation (see examples in Fig. 7A). Following washout of cBIMPs, the response was again reduced to pre-PKA activation levels. Cells stably expressing InsP3R2-S937A and transiently expressing M3 receptors did not significantly differ in their concentration versus response relationship to CCh (EC50 1.11 ± 0.023 versus 0.89 ± 0.02 μm; wild type- versus S937A-expressing cells). These data indicate that mutation of S937A per se did not adversely influence the activity of InsP3R. However, in contrast to the InsP3R2 wild type cells, treatment of cells stably expressing InsP3R2-S937A with cBIMPs failed in nine experimental runs from three separate transfections totaling 595 cells representative of various response patterns to result in enhanced CCh-induced Ca2+ signals (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that the sole effect of cBIMPs on InsP3R2 is to induce the phosphorylation of Ser937.

FIGURE 7.

cBIMPs enhances muscarinic receptor-induced Ca2+ transients in cells stably expressing wild type, but not S937A mutated InsP3R2. Stable DT40 cell lines were generated expressing wild type (DT40-InsP3R2) or S937A mutated (DT40-InsP3R2-S937A) InsP3R2. Cells were transfected with cDNA expressing M3R, and Fura-2 measurements were made on cells treated with CCh in the presence or absence of cBIMPs, as indicated. In these experiments, the acquisition rate was decreased between CCh stimulations. A, examples of the effects of cBIMPs on DT40-InsP3R2 cells from four independent experiments; B, examples of responses in four independent experiments with DT40-InsP3R2-S937A cells.

DISCUSSION

Cross-talk between the cAMP- and Ca2+-signaling pathways can allow efficient regulation of the temporal and spatial aspects of cellular Ca2+ signals. This shaping of Ca2+ signals is thought to account for the wide range of physiological effects of intracellular Ca2+. Understanding the molecular determinants behind this cross-talk is important in gaining a clearer picture of cell function and may provide targets for possible pharmaceutical interventions. Phosphorylation of InsP3R by PKA constitutes a means of regulating Ca2+ signaling by directly altering the Ca2+ release event. We have described an InsP3R2-specific and receptor-distinct mechanism that may account for enhanced Ca2+ signaling in response to cAMP in cells expressing InsP3R2. Specifically, PKA phosphorylation of a unique serine residue (Ser937) increases the single channel Po and Ca2+ release activity of InsP3R2.

Phosphorylation of Ser937 in InsP3R2 clearly leads to enhanced channel activity, but the ultimate molecular mechanism behind this effect is still a major unanswered question. We have recently identified effects of phosphorylation on InsP3R1 channel activity by examining changes in single channel properties in phosphomimetic mutations of this isoform (20). Specifically, phosphorylation is thought to increase channel activity primarily by altering the probability of the channel exhibiting a high Po “burst” phase. It is currently unknown whether PKA phosphorylation of InsP3R2 exerts similar effects on this isoform. Analysis of an S937E/D phosphomimetic mutation could yield further mechanistic insights about the enhancing effects of PKA on InsP3R2.

In addition to remaining mechanistic questions, an understanding of the physiological consequence of InsP3R2 phosphorylation is lacking. Questions regarding the physiological significance of InsP3R phosphorylation will be greatly aided by the analysis of InsP3R2 knock-out mice (10, 11, 51). Cardiac myocytes, liver hepatocytes, and astrocytes all express InsP3R2 predominantly (8, 9). Analysis of agonist-induced Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes showed that acetylcholine, glutamate, and bradykinin-induced Ca2+ signals were completely absent in cells from InsP3R2-KO mice (10). As such, modulation of InsP3R2 by PKA and other mechanism would probably be important for astrocytic Ca2+ signaling. Similarly, activation of endothelin receptors in atrial myocytes produces arrhythmogenic Ca2+ signals that are eliminated in cells from InsP3R2-KO mice (11). β-Adrenergic activation is known to modulate a range of proteins involved in cardiac Ca2+ handling (52). Enhanced InsP3R2 Ca2+ signaling by this pathway may exacerbate the arrhythmogenic potential of endothelin receptor activation. Finally, cAMP production is known to potentiate InsP3-induced Ca2+ signaling in hepatocytes, where InsP3R2 is the predominant isoform (13, 27). Phosphorylation of Ser937 of InsP3R2 in hepatocytes could mediate this effect. Consistent with this idea, Ser937 was identified by mass spectroscopy as being phosphorylated in a global screen of hepatic phosphoproteins (53). The role of PKA phosphorylation of InsP3R2 in tissues such as liver and heart should be the subject of further study.

The effects of PKA phosphorylation on InsP3R2 were only evident at low levels of stimulation. InsP3R2 localization is correlated with sites of Ca2+ wave initiation in hepatocytes (54, 55). Similarly, regions of astrocyte ER that exhibit enhanced Ca2+ release are enriched with InsP3R2 (56). These results indicate that InsP3R2 might be involved with initiating and propagating Ca2+ waves in these cells. Sensitizing InsP3R2 to lower levels of InsP3 by PKA phosphorylation could lower the threshold for initiating global Ca2+ transients. A hierarchy of Ca2+ signals is produced in response to InsP3, ranging from Ca2+ puffs involving a few InsP3R to Ca2+ waves that recruit multiple Ca2+ release sites (57–59). Similarly, phosphorylation of a few InsP3R2s in a cluster could increase the probability that an elementary Ca2+ signal will result in a global Ca2+ wave.

In summary, the results presented here add significantly to our knowledge of the functional effects and the molecular determinants of PKA regulation of InsP3R2. The physiological importance of InsP3R2 is only beginning to be understood. It should be noted, however, that this isoform is expressed to some extent in most mammalian cells (8). This suggests that enhancing InsP3R2 activity by PKA will have profound effects on Ca2+ signaling and cell function in many different physiological contexts. Similarly, phosphorylation of InsP3R2 by other kinases, including PKC (60), Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (61), and Src kinase (62), has been reported. These and other kinases are thought to impact Ca2+ signaling by regulating InsP3R2 activity, but knowledge of phosphorylation sites is lacking. Application of the fragment-based approach described here should help to identify the molecular determinants behind the effects of kinases other than PKA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Lyndee Knowlton for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-DK054568 and RO1-DE016999 (to D. I. Y.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- InsP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- InsP3R

- InsP3 receptor

- CCh

- carbachol

- M3R

- human muscarinic M3R

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- cBIMPs

- 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzylimadazole-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP

- IBMX

- isobutylmethylxanthine

- BAPTA

- 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge M. J. (1993) Nature 361, 315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce J. I., Straub S. V., Yule D. I. (2003) Cell Calcium 34, 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Natarajan M., Lin K. M., Hsueh R. C., Sternweis P. C., Ranganathan R. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 571–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce J. I., Shuttleworth T. J., Giovannucci D. R., Yule D. I. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straub S. V., Wagner L. E., 2nd, Bruce J. I., Yule D. I. (2004) Biol. Res. 37, 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang G., Joseph J. W., Chepurny O. G., Monaco M., Wheeler M. B., Bos J. L., Schwede F., Genieser H. G., Holz G. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8279–8285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor C. W., Genazzani A. A., Morris S. A. (1999) Cell Calcium 26, 237–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wojcikiewicz R. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11678–11683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzclaw L. A., Pandhit S., Bare D. J., Mignery G. A., Russell J. T. (2002) Glia 39, 69–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petravicz J., Fiacco T. A., McCarthy K. D. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 4967–4973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X., Zima A. V., Sheikh F., Blatter L. A., Chen J. (2005) Circ. Res. 96, 1274–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X., Wen J., Bidasee K. R., Besch H. R., Jr., Wojcikiewicz R. J., Lee B., Rubin R. P. (1999) Biochem. J. 340, 519–527 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess G. M., Bird G. S., Obie J. F., Putney J. W., Jr. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 4772–4781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirono C., Sugita M., Furuya K., Yamagishi S., Shiba Y. (1998) J. Membr. Biol. 164, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walaas S. I., Nairn A. C., Greengard P. (1986) J. Neurosci. 6, 954–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Supattapone S., Danoff S. K., Theibert A., Joseph S. K., Steiner J., Snyder S. H. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 8747–8750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volpe P., Alderson-Lang B. H. (1990) Am. J. Physiol. 258, C1086–C1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Li W. H., Yule D. I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45811–45817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Li W. H., Joseph S. K., Yule D. I. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46242–46252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Joseph S. K., Yule D. I. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 3577–3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojcikiewicz R. J., Luo S. G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5670–5677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soulsby M. D., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2005) Biochem. J. 392, 493–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melvin J. E., Yule D., Shuttleworth T., Begenisich T. (2005) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 445–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giovannucci D. R., Groblewski G. E., Sneyd J., Yule D. I. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33704–33711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straub S. V., Giovannucci D. R., Bruce J. I., Yule D. I. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31949–31956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Regimbald-Dumas Y., Arguin G., Fregeau M. O., Guillemette G. (2007) J. Cell. Biochem. 101, 609–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajnóczky G., Gao E., Nomura T., Hoek J. B., Thomas A. P. (1993) Biochem. J. 293, 413–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soulsby M. D., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2007) Cell Calcium 42, 261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwai M., Tateishi Y., Hattori M., Mizutani A., Nakamura T., Futatsugi A., Inoue T., Furuichi T., Michikawa T., Mikoshiba K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10305–10317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W., Malcolm B. A. (2002) Methods Mol. Biol. 182, 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betzenhauser M. J., Wagner L. E., 2nd, Iwai M., Michikawa T., Mikoshiba K., Yule D. I. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21579–21587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betzenhauser M. J., Wagner L. E., 2nd, Won J. H., Yule D. I. (2008) Methods 46, 177–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner L. E., 2nd, Betzenhauser M. J., Yule D. I. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17410–17419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dellis O., Dedos S. G., Tovey S. C., Taufiq-Ur-Rahman, Dubel S. J., Taylor C. W. (2006) Science 313, 229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dellis O., Rossi A. M., Dedos S. G., Taylor C. W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 751–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wojcikiewicz R. J., He Y. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213, 334–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swatton J. E., Taylor C. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17571–17579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joseph S. K., Lin C., Pierson S., Thomas A. P., Maranto A. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23310–23316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maes K., Missiaen L., De Smet P., Vanlingen S., Callewaert G., Parys J. B., De Smedt H. (2000) Cell Calcium 27, 257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugawara H., Kurosaki M., Takata M., Kurosaki T. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 3078–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schug Z. T., da Fonseca P. C., Bhanumathy C. D., Wagner L., 2nd, Zhang X., Bailey B., Morris E. P., Yule D. I., Joseph S. K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2939–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tovey S. C., Dedos S. G., Taylor E. J., Church J. E., Taylor C. W. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 183, 297–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joseph S. K., Bokkala S., Boehning D., Zeigler S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16084–16090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shabb J. B. (2001) Chem. Rev. 101, 2381–2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshikawa F., Iwasaki H., Michikawa T., Furuichi T., Mikoshiba K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maes K., Missiaen L., Parys J. B., De Smet P., Sienaert I., Waelkens E., Callewaert G., De Smedt H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3492–3497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan M. T., Wagner L., 2nd, Yule D. I., Bhanumathy C., Joseph S. K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3731–3737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szado T., Vanderheyden V., Parys J. B., De Smedt H., Rietdorf K., Kotelevets L., Chastre E., Khan F., Landegren U., Söderberg O., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2427–2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soulsby M. D., Alzayady K., Xu Q., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2004) FEBS Lett. 557, 181–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pieper A. A., Brat D. J., O'Hearn E., Krug D. K., Kaplin A. I., Takahashi K., Greenberg J. H., Ginty D., Molliver M. E., Snyder S. H. (2001) Neuroscience 102, 433–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Futatsugi A., Nakamura T., Yamada M. K., Ebisui E., Nakamura K., Uchida K., Kitaguchi T., Takahashi-Iwanaga H., Noda T., Aruga J., Mikoshiba K. (2005) Science 309, 2232–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bers D. M. (2002) Nature 415, 198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villén J., Beausoleil S. A., Gerber S. A., Gygi S. P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1488–1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirata K., Pusl T., O'Neill A. F., Dranoff J. A., Nathanson M. H. (2002) Gastroenterology 122, 1088–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hernandez E., Leite M. F., Guerra M. T., Kruglov E. A., Bruna-Romero O., Rodrigues M. A., Gomes D. A., Giordano F. J., Dranoff J. A., Nathanson M. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10057–10067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sheppard C. A., Simpson P. B., Sharp A. H., Nucifora F. C., Ross C. A., Lange G. D., Russell J. T. (1997) J. Neurochem. 68, 2317–2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bootman M. D., Berridge M. J., Lipp P. (1997) Cell 91, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parker I., Choi J., Yao Y. (1996) Cell Calcium 20, 105–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marchant J. S., Parker I. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arguin G., Regimbald-Dumas Y., Fregeau M. O., Caron A. Z., Guillemette G. (2007) J. Endocrinol. 192, 659–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bare D. J., Kettlun C. S., Liang M., Bers D. M., Mignery G. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15912–15920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan Z., Cai T., Tian J., Ivanov A. V., Giovannucci D. R., Xie Z. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4034–4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.