Abstract

A group of breast cancer patients with a higher probability of developing metastasis expresses a series of carboxyl-terminal fragments (CTFs) of the tyrosine kinase receptor HER2. One of these fragments, 611-CTF, is a hyperactive form of HER2 that constitutively establishes homodimers maintained by disulfide bonds, making it an excellent model to study overactivation of HER2 during tumor progression and metastasis. Here we show that expression of 611-CTF increases cell motility in a variety of assays. Since cell motility is frequently regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, we looked for phosphoproteins mediating the effect of 611-CTF using two alternative proteomic approaches, stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture and difference gel electrophoresis, and found that the latter is particularly well suited to detect changes in multiphosphorylated proteins. The difference gel electrophoresis screening identified cortactin, a cytoskeleton-binding protein involved in the regulation of cell migration, as a phosphoprotein probably regulated by 611-CTF. This result was validated by characterizing cortactin in cells expressing this HER2 fragment. Finally, we showed that the knockdown of cortactin impairs 611-CTF-induced cell migration. These results suggest that cortactin is a target of 611-CTF involved in the regulation of cell migration and, thus, in the metastatic behavior of breast tumors expressing this CTF.

Deregulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling network contributes to initiate and/or maintain malignant growth (1). One of these alterations, aberrant cellular motility, is necessary for invasive growth, which eventually culminates with the establishment of distant metastases, the leading cause of death in patients with cancer.

The epidermal growth factor receptor is the prototype of a family that also includes HER2 (ErbB2, Neu), HER3, and HER4 (ErbB3 and ErbB4). The analysis of cells expressing various HER receptors indicated that HER2 plays a critical role in the regulation of motility (2, 3). Upon activation through homo- or heterodimerization with other HER receptors, several tyrosines in the cytoplasmic tail of HER2 are phosphorylated and initiate intracellular signaling pathways, including the phospholipase C-γ1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways (4), which, in turn, promote cell migration through partially understood cascades. These cascades are largely regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of cellular components.

A subgroup of HER2-positive patients expresses a series of carboxyl-terminal fragments (CTFs)5 of HER2. HER2 CTFs can be generated by two independent mechanisms: proteolytic processing and alternative initiation of translation. Metalloproteases with the so-called α-secretase activity shed the extracellular domain of HER2, leaving behind a fragment, known as P95, that starts around alanine 648 (5) (see also Fig. 1A). Alternative initiation of translation of the mRNA encoding HER2 from the methionine codons 611 and 687 generates two fragments: 611- and 687-CTF. These differ by a stretch of 76 amino acids, which includes the transmembrane domain and a cysteine-rich short extracellular domain (6) (see also Fig. 1A).

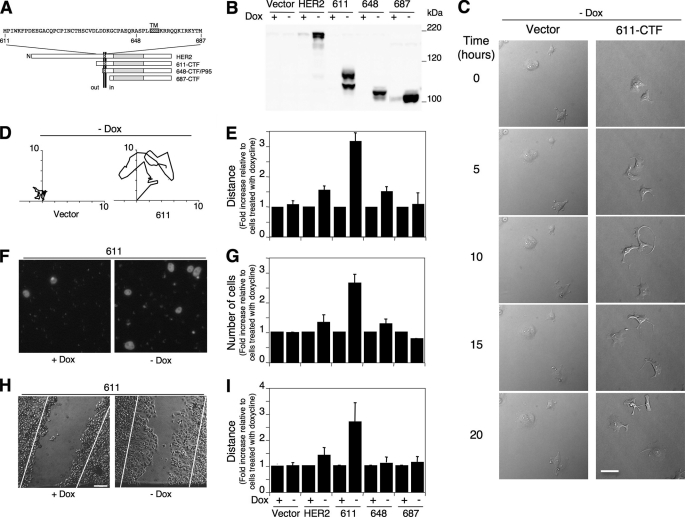

FIGURE 1.

Effect of HER2 CTFs on cell migration. A, schematic showing the different constructs used in these studies. The primary sequence of the extracellular and intracellular juxtamembrane domains of HER2 is shown. The transmembrane domain (TM) is represented by a hatched box. The positions of amino acids 611, 648, and 687 are indicated. The N at the beginning of the rectangle representing HER2 identifies the amino terminus. The vertical bold double line represents the plasma membrane, and the extracellular (out) and intracellular (in) regions are marked. B, MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with the empty vector (Vector) or with the vector containing the cDNAs encoding HER2 or 611-, 648-, or 687-CTFs under the control of a Tet/Dox-responsive element were kept with or without doxycycline for 24 h, lysed, and analyzed by Western blot with CB11, an antibody against the cytoplasmic domain of HER2. C, MCF7 Tet-Off cells transfected with empty vector or with 611-CTF were seeded in the absence of doxycycline, and motility was monitored by time lapse video microscopy. Representative fields of migrated cells at the indicated times are shown. Results indistinguishable from those corresponding to MCF7 Tet-Off cells transfected with vector and treated without doxycycline were observed when analyzing MCF7/611-CTF Tet-Off cells in the presence of doxycycline (data not shown). D, representative examples of the migratory behavior of MCF7 Tet-Off cells treated as in C. Digital images were taken every 30 min for 24 h (see supplemental videos), and the tracks were manually drawn. Results indistinguishable from those corresponding to MCF7 Tet-Off cells transfected with vector and treated without doxycycline were observed when analyzing MCF7/611-CTF Tet-Off cells in the presence of doxycycline (data not shown). E, tracks from cells analyzed as in D were measured in mm. Bars, average length ± S.D. of the tracks of five cells, each one on a different culture plate. F, MCF7 Tet-Off cells transfected with 611-CTF were seeded in the absence or the presence of doxycycline on transwell plates, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After 24 h, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. Representative fields are shown. G, MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with the empty vector (Vector) or with the vector containing the cDNAs encoding HER2 or 611-, 648-, or 687-CTFs were seeded on transwell plates with or without doxycycline as indicated. After 24 h, cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and counted. Bars, average of the cells counted in three independent experiments, each one performed in triplicate, ± S.D. H, representative examples of the images obtained by time lapse microscopy of the closure of wounds made in a monolayer of control MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with 611-CTF and treated with or without doxycycline as indicated. The lines drawn in the images represent reference lines marking the width of the scratch when it was made. I, average values of migration distances in scratch wound assays as in H. Bars, means from three independent experiments, each one derived from evaluation of 10 fields ± S.D.

We have recently shown that 687-CTF seems to be inactive (7). In contrast, the two CTFs containing the transmembrane domain, 648- and 611-CTFs, expressed at levels similar to those found in human breast tumors, can activate different intracellular signal transduction pathways (7). The level of activation of these pathways by HER2 CTFs is quite different. 611-CTF activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the Akt pathways to a greater extent because it constitutively forms homodimers maintained through disulfide bonds (7). In contrast, 648-CTF does not seem to form homodimers, and its activity is comparable with that of full-length HER2 (7). Therefore, cells expressing transmembrane CTFs, particularly 611-CTF, constitute a relevant model to study the consequences of the overactivation of HER2 signaling in tumors. Supporting this conclusion, it has been shown that breast cancer patients expressing CTFs have worse prognosis and are more likely to develop nodal metastasis compared with patients expressing predominantly full-length HER2 (8).

Here we show that expression of 611-CTF enhances the migration of breast cancer cells as judged by monitoring single-cell migration, transwell migration, and wound healing assays. Since cell migration is frequently regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, we searched for phosphoproteins regulated by 611-CTF and probably contributing to cell migration using two independent proteomic approaches. The results of these analyses showed that difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE) is a particularly convenient methodology to analyze the regulation of multiphosphorylated proteins.

Cortactin, a cytoskeleton-binding protein involved in the regulation of cell migration, was identified by DIGE as a phosphoprotein likely to be regulated by 611-CTF. Several assays showed that expression of 611-CTF leads to an increase in the phosphorylation of cortactin and to the generation of cell protrusions resembling lamellipodia or invadopodia. Confirming a role of cortactin on the increased cell migration induced by 611-CTF, down-modulation of the former with short hairpin RNAs leads to an impairment of the cell migration induced by the HER2 fragment. These results unveil a role of cortactin in the increased cell migration induced by hyperactive HER2 and strongly suggest that cortactin-dependent increased cell migration contributes to the tendency of breast tumors expressing CTFs to metastasize.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells

MCF7 Tet-Off (BD Biosciences) transfected with full-length HER2, 611-CTF, 648-CTF, and 687-CTF have been recently characterized (7).

To generate cortactin knockdowns, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells were transfected with empty pRetroSuper vector or with the same vector expressing a hairpin targeting cortactin (5′-GAT CCC CCC ACA GAA TTT GCT AAT ATT TCA AGA GAA TAT TAG CAA ATT CTG TGG TTT TTA-3′). Stable transfectants were selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin, and the levels of cortactin were analyzed by Western blot. Two independent clones, 611 sh1 and 611 sh2, with ∼3.5- and ∼7-fold lower levels of cortactin compared with cells transfected with vector, respectively, were chosen for further analysis.

Antibodies

Antibodies were from Cell Signaling (P-Erk1/2 (catalog number 9101), Erk1/2 (catalog number 9102), P-Akt (catalog numbers 9275 and 9271), and Akt (catalog number 9272)), BioGenex (anti-HER2 (CB11)), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA) (anti-cortactin (clone H-191)), Abcam (anti-cortactin Y-421 (catalog number ab47768)) Sigma (anti-FLAG epitope), Upstate Biotechnology (anti-phosphotyrosine (clone 4G10) and anti-cortactin (clone 4F11)), Neomarkers (anit-p21WAF1), BD Pharmigen (anti-Bid), Amersham Biosciences (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated), and Invitrogen (anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgGs linked to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa 568). Anti-EF2 antibody was a kind gift from Dr. C. G. Proud (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada).

Western Blot

Extracts for immunoblots were prepared in modified radioimmune precipitation buffer (20 mm NaH2PO4/NaOH, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mm EDTA, 100 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 mm NaF, 16 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1.3 mm Na3VO4), and protein concentrations were determined with DC protein assay reagents (Bio-Rad). Samples were mixed with loading buffer (final concentrations: 62 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 12% glycerol, 2.5% SDS) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol and incubated at 99 °C for 5 min before fractionation of 15 μg of protein by SDS-PAGE. Where appropriate, signals in Western blots were quantified with the software ImageJ 1.38 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

For two-dimensional blots, protein extracts were isoelectrofocused on immobilized pH gradient strips (7 cm; pH 4–7) using an Ettan IPGphor system. After focusing, the strips were equilibrated for 15 min in a reducing solution (6 m urea, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 5 mg/ml dithiothreitol), and the focused proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Finally, the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) and immunoblotted with anti-cortactin antibodies.

Inhibitors

PP2 (Src inhibitor) and PD98056 (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor) were both from Calbiochem. Lapatinib was kindly provided by GlaxoSmithKline (Research Triangle Park, NJ).

Single Cell Time Lapse Video Recording

Cell motility data were generated using a single-cell time lapse video microscopy system consisting of an inverted microscope with ×10 magnification differential interference contrast objective (Olympus IX-81, Olympus, Japan); motorized xy-stage, z-focus drive, and shutter (Olympus, Japan); charge-coupled device camera (Olympus, Japan); and automated data acquisition software (CELL-R, Olympus, Japan). Individual cell tracks were manually drawn, from digital images taken every 30 min for 24 h, by plotting the position of the cell nucleus.

Transwell Chamber Assays

2.5 × 104 cells were plated onto serum-coated transwells (8-μm pore membranes; Corning Glass). After 48 h, cells of the upper side of the membrane were removed with a cotton swab, and the migrated cells in the lower side were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Finally, membranes were excised and mounted on glass slides, using mounting medium with DAPI (VectaShield; Vector Laboratories). Cells in the lower side of the membranes were counted in an epifluorescence microscope Nikkon Eclipse TE2000-S, assessing five random fields at ×20 magnification.

Scratch Wound Assays

Confluent cell monolayers were scratch-wounded with a yellow Gilson pipette tip and further cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline. The average migration distance was calculated by subtracting the wound width after 24 h of migration from that of the reference wound.

Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC)

MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells were seeded in SILAC DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with dialyzed serum (amino acid-free) and the appropriate normal or isotopically labeled amino acids: 12C14N (“light”) arginine and 12C (“light”) lysine or 13C15N (“heavy”) arginine and 13C (“heavy”) lysine. Cells were incubated for a total of 7 days, corresponding to ∼5 cell doublings.

Cells labeled with light or heavy isotopes were cultured with or without doxycycline, respectively, for 18 h in the presence of serum and an additional 6 h in serum-free media and lysed. Proteins in cell lysates were quantified and mixed 1:1. Phosphoproteins were purified with the Qiagen phosphoprotein purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors. Purified phosphoproteins were resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and subjected to one-dimensional electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gel.

The one-dimensional gel lanes were cut into 20 horizontal slices, and each slice was subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion using modified porcine trypsin (Promega). The digests were then analyzed on an Esquire HCT IT mass spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen), coupled to a nano-high pressure liquid chromatography system (Ultimate; LC Packings). Peptide mixtures were first concentrated on a 300-mm inner diameter, 1-mm PepMap nanotrapping column and then loaded onto a 75-mm inner diameter, 15-cm PepMap nanoseparation column (LC Packings). Peptides were then eluted by an acetonitrile gradient (0–60% B in 150 min, where B is 80% ACN, 0.1% formic acid in water; flow rate ∼300 nl/min) through a PicoTip emitter nanospray needle (NewObjective, Woburn, MA) onto the nanospray ionization source of the IT mass spectrometer. MS/MS fragmentation (1.9 s, 100–2800 m/z) was performed on two of the most intense ions, as determined from a 1.2-s MS survey scan (310–1500 m/z), using a dynamic exclusion time of 1.2 min for precursor selection and excluding single-charged ions. An automated optimization of MS/MS fragmentation amplitude, starting from 0.60 V, was used.

Data processing for protein identification and quantitation was performed using WARP-LC 1.1 (Bruker, Bremen), a software platform integrating liquid chromatography-MS run data processing, protein identification through data base search of MS/MS spectra, and protein quantitation based on the integration of the chromatographic peaks of MS-extracted ion chromatograms for each precursor. Proteins were identified using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, UK) to search the International Protein Index-Human 3.26 data base (67,665 sequences, 28,462,007 residues) (9). MS/MS spectra were searched with a precursor mass tolerance of 1.5 Da, fragment tolerance of 0.5 Da, trypsin specificity with a maximum of 1 missed cleavage, cysteine carbamidomethylation set as fixed modification, and methionine oxidation and the corresponding Lys and Arg SILAC labels as variable modifications. The positive identification criterion was set as an individual Mascot score for each peptide MS/MS spectrum higher than the corresponding homology threshold score. The false positive rate for Mascot protein identification was measured by searching a randomized decoy data base, as described by Elias and Gygi (10), and estimated to be under 5%. A second round search restricted to the proteins positively identified in the first Mascot search was performed setting Ser, Thr, and Tyr phosphorylation as additional variable modifications. For protein quantitation, heavy/light (H/L) ratios were calculated averaging the measured H/L ratios for the observed peptides, after discarding outliers. For selected proteins of interest, quantitation data obtained from the automated WARP-LC analysis was manually reviewed.

DIGE

107 MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells were seeded and cultured with or without doxycycline for 18 h in the presence of serum and an additional 6 h in serum-free media and lysed. Phosphoproteins were purified from cell lysates with the Qiagen phosphoprotein purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions and in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors.

Purified phosphoproteins were adjusted to a concentration of 2 mg/ml by the addition of DIGE labeling buffer. 50 mg of each sample were labeled by the addition of 400 pmol of either Cy3 or Cy5 cyanine dyes (GE Healthcare) in 1 ml of anhydrous dimethylformamide. After 30 min of incubation on ice in the dark, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 10 mm lysine followed by a further 10 min of incubation. After labeling, the samples corresponding to cells not expressing (Cy3) and expressing 611-CTF (Cy5) were mixed and diluted 2-fold with isoelectric focusing sample buffer (8 m urea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 2% dithiothreitol, 2% pharmalytes, pH 3–10).

Two-dimensional electrophoresis was performed using GE Healthcare reagents and equipment. First dimension isoelectric focusing was performed on immobilized pH gradient strips (24 cm; pH 3–10) using an Ettan IPGphor system. Samples were applied via cup loading near the basic end of the strips, previously rehydrated overnight in 450 ml of rehydration buffer (8 m urea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 1% pharmalytes, pH 3–10, 100 mm DeStreak). After focusing for a total of 67 kV-h, the strips were equilibrated first for 15 min in 6 ml of reducing solution (6 m urea, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 5 mg/ml dithiothreitol) and then in 6 ml of alkylating solution (6 m urea, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 22.5 mg/ml iodoacetamide) for a further 15 min on a rocking platform. Second dimension SDS-PAGE was run by overlaying the strips on 12.5% isocratic Laemmli gels (24 × 20 cm), cast in low fluorescence glass plates, on an Ettan DALT VI system. Gels were run at 20 °C, at 2.5 watts/gel constant power during 30 min followed by 17 watts/gel until the bromphenol blue tracking front had run off the bottom of the gels (about 5 h).

Fluorescence images of the gels were acquired on a Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare). Cy3 and Cy5 images were scanned at 532-nm excitation/580-nm emission and 633-nm excitation/670-nm emission, respectively, at a 100 mm resolution. Image analysis was performed using DeCyder version 5.0 software (GE Healthcare). Selected proteins of interest were excised from the gels, subjected to trypsin digestion, and identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-tandem time of flight mass spectrometry as described (11).

In Vitro Phosphorylation of Cortactin

FLAG-tagged constructs were purified by immunoprecipitation with M2-anti-FLAG-agarose beads (Sigma) from transiently transfected HEK293 cells. Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer, containing 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm EDTA, 5 mm NaF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The kinase activity was determined by incubating the immunoprecipitated material for 4 h with lysates of MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with 611-CTF treated or not with doxycycline, in 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm MnCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 μm cold ATP, and 0.3 μm [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol).

To analyze in vitro kinase activity of 611-CTF, it was purified by immunoprecipitation with CB11 antibody from MCF7 Tet-Off cells treated or not with doxycycline and incubated for 24 h with cortactin-FLAG purified as above in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells for immunofluorescence microscopy seeded on glass coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. For blocking and antibody binding, we used phosphate-buffered saline with 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% saponin, and 0.02% NaN3, and for mounting, we used Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

RESULTS

Effect of CTFs on Cell Migration

To analyze the effect of individual CTFs on cell migration, we used MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with plasmids encoding HER2 or 611-, 648-, or 687-CTFs (Fig. 1A; see also Ref. 7) and, as control, the same cells transfected with the empty vector. Analysis by Western blot showed that, except for cells transfected with 611-CTF, each cell line predominantly expressed HER2 species of the expected molecular weight (Fig. 1B). In cells transfected with 611-CTF, we detected two isoforms (Fig. 1B). Previous characterization showed that the faster migrating one is an intracellular precursor, and the slower migrating form is N-glycosidated and located at the cell surface (7).

Analysis of cell migration tracks by time lapse video microscopy showed that, while the expression of 687-CTF had no effect on cell migration, expression of full-length HER2 and 648-CTF induced a slight (∼1.5-fold) increase in cell migration speed (Fig. 1E). In contrast, the expression of 611-CTF led to a higher (∼3-fold) increase in the same assay and to the formation of very dynamic cell protrusions typical of migrating cells (Fig. 1, C–E, and supplemental videos). Equivalent results were observed when assaying cell migration in serum-coated transwells (Fig. 1, F and G). Although 687-CTF had no effect and HER2 and 648-CTF induced a modest increase in the number of cells that migrated through the transwell membrane (Fig. 1G), 611-CTF induced a ∼2.5-fold increase (Fig. 1, F and G).

Finally, and in agreement with the previous assays, cells expressing 611-CTF closed the wounds made in a confluent cell monolayer faster than control cells or cells expressing HER2 or 648- or 687-CTF (Fig. 1, H and I).

Similar results were obtained with an independent 611-CTF clone (data not shown) that expresses one-fifth the levels of the clone shown in Fig. 1. The levels of 611-CTF in this low expressing clone are similar to those found in human tumors (7). In summary, the results of the different assays consistently show that the expression of 611-CTF increases the ability of cells to migrate.

Identification of Phosphoproteins Regulated by 611-CTF by SILAC

Cell motility is frequently regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of cellular components. Consistently, treatment with lapatinib, a potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets both HER2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor (12) and is commonly used to analyze HER2-dependent processes (e.g. see Ref. 13), prevented the increase in cell migration observed in the transwell migration assay (supplemental Fig. S1). To identify phosphoproteins regulated by 611-CTF, we used two different proteomic techniques, SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture) (14) and DIGE (15). SILAC is considered the most accurate way of quantifying differential protein expression and is based on the labeling of proteins with isotopic variants of the same amino acids (16). DIGE is an alternative quantitative proteomic technique, which is based on the labeling of proteins with different fluorochromes. Labeled proteins are loaded onto a single two-dimensional gel, thereby overcoming the lack of reproducibility inherent to two-dimensional electrophoresis (15).

To perform the SILAC analysis, we cultured MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells with arginine and lysine labeled with light and heavy isotopes (Fig. 2A) (see “Experimental Procedures”). Then the expression of 611-CTF was induced by removal of doxycycline from the culture medium of cells labeled with heavy isotopes. Next, cells expressing 611-CTF as well as non-expressing control cells (i.e. cells labeled with light arginine and lysine and kept in the presence of doxycycline) were lysed (Fig. 2A). Cell lysates were mixed one to one, and phosphoproteins, purified from this mixture using metal affinity chromatography, were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). After separation, the gel was cut horizontally in 20 slices, and these gel segments were separately processed (see “Experimental Procedures”) to identify peptides by mass spectrometry and compare their relative abundance in lysates from control cells and cells expressing 611-CTF (Fig. 2A).

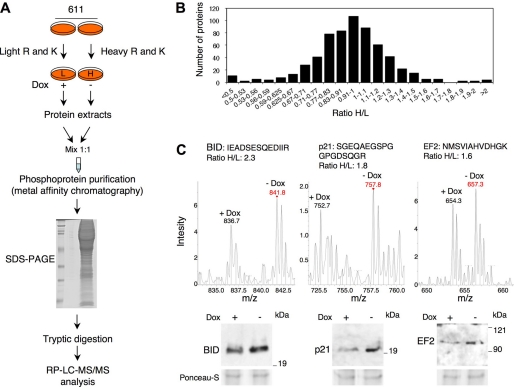

FIGURE 2.

Quantitative comparison between the phosphoproteome of control cells and cells expressing 611-CTF by SILAC. A, schematic showing the protocol used. MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with 611-CTF were grown with either light or heavy lysine and arginine for 7 days. Labeled cells were treated with or without doxycycline for 24 h and lysed. Protein extracts were mixed 1:1, and phosphoproteins were purified from the mixture by metal affinity chromatography. Purified phosphoproteins were fractionated through SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin, and loaded in the ion trap mass spectrometer after reverse phase chromatography. B, distribution of the average heavy/light ratios. The average heavy/light ratios of the proteins identified, distributed in the indicated intervals, were plotted against the number of proteins in each interval. C, individual analysis of selected proteins putatively regulated by 611-CTF as judged by SILAC. Upper panels, mass spectra of peptide doublets from the selected proteins. The sequences of the peptides are shown. Bottom panels, phosphoprotein fractions enriched by metal affinity chromatography were analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. Ponceau-stained membranes were used as loading and transfer controls.

3260 peptides from 658 individual proteins were identified. The distribution of the H/L ratios indicated that the majority of phosphoproteins were not affected by the expression of 611-CTF (Fig. 2B). Proteins exhibiting average H/L ratios outside the interval 0.8–1.3 are shown in supplemental Table S1. To illustrate these results, peptide doublets from BID, a proapoptotic factor that belongs to the Bcl-2 protein family, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21), and EF2 (translation elongation factor 2) are shown in Fig. 2C (upper panels). Direct determination of the levels of BID, p21, and EF2 in phosphoprotein fractions of cells treated without or with doxycycline (Fig. 2C, bottom panels) validated the results of the SILAC analysis. However, none of the proteins identified appeared to be firm candidates to regulate cell migration (supplemental Table S1).

Identification of Phosphoproteins Regulated by 611-CTF by DIGE

To identify additional phosphoproteins regulated by 611-CTF, we performed a DIGE screening (Fig. 3A). Phosphoproteins from cells expressing 611-CTF or control cells were purified by metal affinity chromatography. Purified phosphoproteins were labeled with the cyanine dyes Cy3 or Cy5 and analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3A). To visualize the protein spots, the gel was scanned with fluorophore-specific excitation and emission wavelengths, and two independent images were acquired (Fig. 3B), each corresponding to an individual Cy-labeled probe. Image analysis and determination of significant alterations in spot abundances were performed automatically with the DeCyder software.

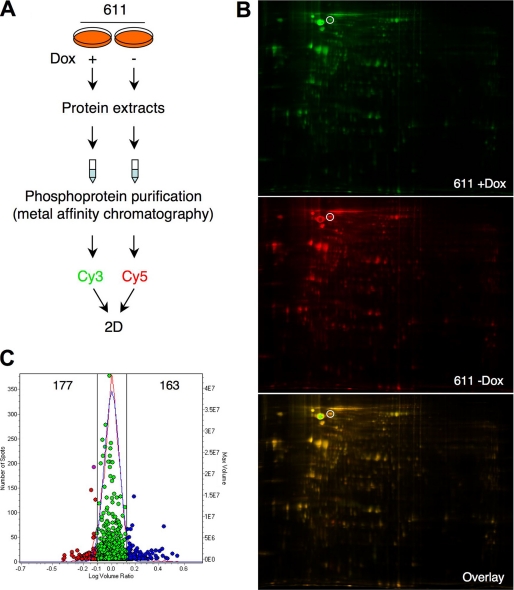

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative comparison between the phosphoproteome of control cells and cells expressing 611-CTF by DIGE. A, schematic showing the protocol used. MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with 611-CTF were treated with or without doxycycline for 24 h and lysed. Phosphoproteins purified from cell lysates by metal affinity chromatography were labeled with the cyanine dyes Cy3 and Cy5, mixed 1:1, and analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis. B, the two-dimensional gel was scanned with different wavelengths to visualize protein patterns corresponding to proteins labeled with Cy3 and Cy5. The positions of the spots corresponding to cortactin are marked with a white circle. C, experimental (red curve) and normalized model (blue curve) frequency distribution of volume ratios (volume in the Cy5 image divided by volume in the Cy3 image) for the spots detected in the fluorescence images of the DIGE experiment. The volume of each individual protein spot, represented as a single data point, is plotted on the right axis. The 163 spots in blue represent proteins with a higher than 1.3-fold increase in the phosphoprotein fraction of cells expressing 611-CTF. The 177 spots in red represent proteins with a more than 1.3-fold decrease.

In agreement with the results of the SILAC experiment, the majority of spots had a ratio of ∼1 (i.e. they were equally represented in control cells and in cells expressing 611-CTF). Only those protein spots exhibiting a variation in volume ratio above 1.3- or below 0.8-fold (Fig. 3C) were selected and processed (see “Experimental Procedures”) to identify the corresponding proteins. A search of the NCBI non-redundant data base peptide mass information identified 27 of the 340 protein spots analyzed, assigning them to 20 candidate proteins (supplemental Table S2). Underscoring the very different outputs of the proteomic techniques, only two proteins identified by SILAC, EPS8L2 (epidermal growth factor receptor kinase substrate-like protein 2) and the EF2, were also identified by DIGE.

Cortactin Is Regulated by 611-CTF Expression

Among the spots with ratios higher than 1.3 identified by DIGE (i.e. phosphoproteins up-regulated in cells expressing 611-CTF), we found cortactin (supplemental Table S2), a cytoskeleton-binding protein involved in the regulation of cell migration (17, 18). However, cortactin was not identified by SILAC as a candidate protein regulated by 611-CTF (supplemental Table S1). In fact, the relative abundance of peptides from cortactin labeled with light and heavy amino acids (i.e. cortactin from cells not expressing and expressing 611-CTF, respectively) was roughly the same (H/L ratio of 1.02 ± 0.1) (Fig. 4A) (data not shown). In agreement with this result, the levels of cortactin in phosphoprotein fractions from cells expressing 611-CTF were similar to those in control cells as judged by Western blot (Fig. 4B). Note that MCF7 cells express two isoforms of cortactin. Whereas the slower migrating isoform (Fig. 4B, band A) co-migrates with transfected full-length cortactin (data not shown), the faster migrating one (Fig. 4B, band B) probably represents an alternatively spliced isoform lacking one or two actin binding repeats (19).

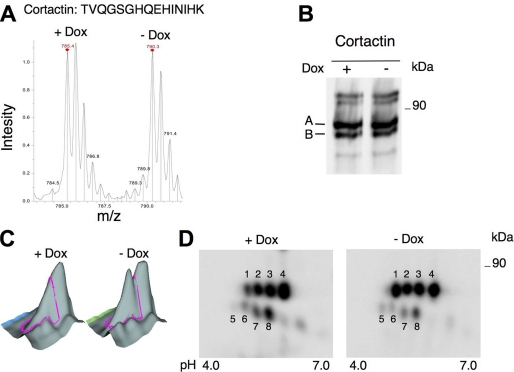

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of cortactin levels in the phosphoprotein fractions of MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline using different proteomic techniques. A, mass spectra of a peptide from cortactin in the SILAC experiment showing a ratio of 1.03. The sequence of the peptide is shown. B, phosphoproteins from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF treated with or without doxycycline for 24 h were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against cortactin. The two isoforms of cortactin detected are labeled A and B. C, three-dimensional profile for the spots corresponding to cortactin as determined by DIGE analysis. D, cell lysates from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF treated with or without doxycycline were analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis/Western blot with antibodies against cortactin. The spots corresponding to isoforms A and B observed were labeled 1–4 and 5–8, respectively.

In contrast to these results, three-dimensional view analysis of the spot identified as cortactin by DIGE showed a clear change between control cells and cells expressing 611-CTF (Fig. 4C). To reconcile these results, we analyzed cortactin levels by two-dimensional electrophoresis/Western blot. The pattern of cortactin in two-dimensional gels was complex, typical of a multiphosphorylated protein, and each isoform migrated as at least four spots (Fig. 4D). In agreement with the results of DIGE, the levels of at least one of the cortactin spots (Fig. 4D, spot 1) clearly increased in cells expressing 611-CTF. This result provides an explanation to the apparent discrepancy between the SILAC and DIGE analysis. Given the high basal phosphate content of cortactin, the phosphorylation induced by 611-CTF does not increase its affinity for the resin used to purify phosphoproteins. Since DIGE is based on the comparison of individual spots, it is particularly well suited to detect changes in proteins with multiple isoforms, such as cortactin.

Phosphorylation of Cortactin and Generation of Cortactin-positive Protrusions in Cells Expressing 611-CTF

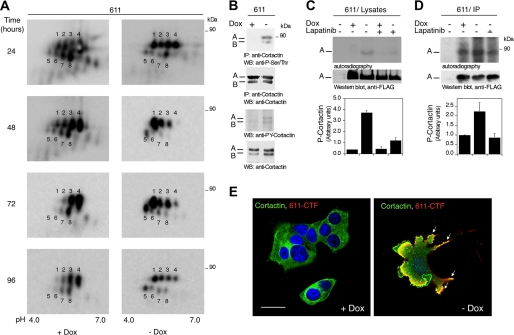

To characterize the regulation of cortactin by 611-CTF, we performed a time course experiment. Expression of 611-CTF induced an increase in the levels of the acidic spots, particularly spots 1 and 5, that peaks between 48 and 72 h (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Regulation of cortactin in cells expressing 611-CTF. A, lysates from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline for the indicated periods of time were analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis/Western blot (WB) with an antibody against cortactin. B, top panels, cortactin was immunoprecipitated (IP) from lysates from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline for 48 h. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed with anti-phosphoserine/phosphothreonine or anti-cortactin antibodies, as indicated. Bottom panels, lysates from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline for 48 h were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against the phosphorylated Tyr421 residue of cortactin, or cortactin, as indicated. C, cortactin tagged at the NH2 terminus with the FLAG epitope was purified from transiently transfected HEK-293 cells with an anti-FLAG antibody. Anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates from mock-transfected cells (first lane) or purified cortactin/FLAG were incubated for 4 h with [γ-32P]ATP, and aliquots of lysates from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline and lapatinib (100 nm), as indicated. Then purified cortactin/FLAG was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and revealed by autoradiography or analyzed by Western blot with anti-FLAG antibodies. The results of three independent experiments ± S.D. are shown. D, FLAG-tagged cortactin was purified as in C and incubated 24 h with [γ-32P]ATP and 611-CTF immunoprecipitated from MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline. Where indicated, 100 nm lapatinib was added to the kinase reaction. Then purified cortactin/FLAG was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and revealed by autoradiography or analyzed by Western blot with anti-FLAG antibodies. The results of five independent experiments ± S.D. are shown. E, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline for 48 h were analyzed in a confocal microscope by indirect immunofluorescence with the antibodies H-191 against cortactin (green) and CB11 against HER2 (red), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Merged images are shown. Bar, 30 μm.

These acidic spots probably corresponded to isoforms of cortactin with higher phosphate content. To confirm that 611-CTF increases the phosphorylation of cortactin, we analyzed cortactin immunoprecipitates and cell lysates with anti-phosphoserine/phosphothreonine and anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies specific for cortactin, respectively (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we incubated purified cortactin tagged with the FLAG epitope (FLAG-cortactin) with lysates from control cells or cells expressing 611-CTF. As shown in Fig. 5C, lysates from cells overexpressing 611-CTF specifically induced phosphorylation of FLAG-cortactin.

Different kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases, Src, and Met, phosphorylate cortactin (20). These kinases are activated by 611-CTF (7); thus, the result in Fig. 5, A–C, may be due to different kinases activated by 611-CTF. To find out if 611-CTF is able to directly phosphorylate cortactin, we incubated purified FLAG-cortactin with immunoprecipitated 611-CTF. The increase in the phosphorylation of FLAG-cortactin induced by incubation with 611-CTFs immunoprecipitates was highly reproducible (Fig. 5D) and indicated that the CTF can phosphorylate cortactin directly. However, there was a clear level of phosphorylation in the absence of the CTF (Fig. 5D, second lane), indicating the existence of additional kinase(s), such as Src, a major contributor to cortactin phosphorylation, able to phosphorylate FLAG-cortactin. Despite this complication, the inclusion of the HER2 inhibitor lapatinib in this assay confirmed that the increase in phosphorylation observed is due to the activity of 611-CTF (Fig. 5C).

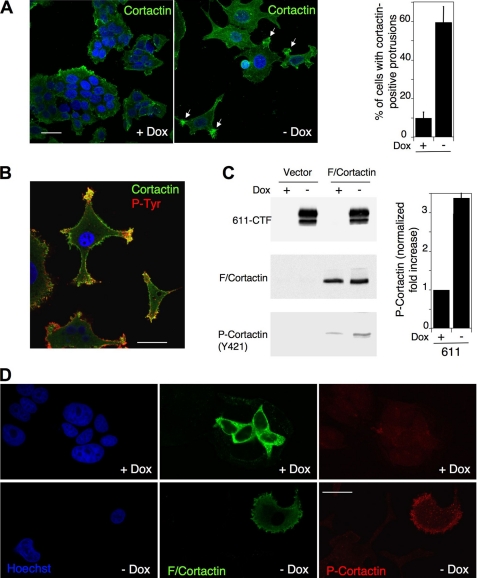

Cortactin was named after its subcellular localization at the cell cortex (21). Immunostaining of control cells with anti-cortactin antibodies was consistent with this subcellular distribution (Figs. 5D and 6). Consistent with the phosphorylation of cortactin by 611-CTF, there were distinct zones of co-localization between both molecules, particularly at cell protrusions (Fig. 5D, −Dox, arrows). In fact, the expression of 611-CTF induced the generation of these cortactin-positive cell protrusions in the majority of cells, as judged by immunofluorescence with two different antibodies (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 6.

611-CTF expression leads to the accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated cortactin at cellular protrusions. A, left, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated with or without doxycycline for 48 h were analyzed in a confocal microscope by indirect immunofluorescence with an antibody against cortactin. Representative cortactin-positive cellular protrusions are marked with white arrows. The bar in the first photograph represents 30 μm. Right, cells bearing cortactin-positive cellular protrusions were counted in five fields and expressed as percentages relative to total cells in the five fields. The averages of three independent quantifications ± S.D. are shown. B, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells treated without doxycycline for 48 h were analyzed in a confocal microscope by indirect immunofluorescence with the antibody H-191 against cortactin (green) and anti-phosphotyrosine (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Merged image is shown. Bar, 30 μm. C, left, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector or the same vector encoding mouse cortactin tagged with the FLAG epitope. Then cells were kept with or without doxycycline for 48 h, lysed, and analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against the cytoplasmic domain of HER2, the FLAG peptide, or the phosphorylated Tyr421 residue of cortactin. Right, the levels of phosphocortactin were quantified and normalized to the total levels of mouse cortactin. The results of three independent experiments ± S.D. are shown. D, cells transfected with mouse cortactin as in C were analyzed in a confocal microscope by indirect immunofluorescence with anti-FLAG (green) and anti-phosphocortactin (Tyr421) (red) antibodies, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Bar, 30 μm.

Tyrosine-phosphorylated cortactin is a marker of invadopodia (22, 23). To analyze the distribution of phosphorylated cortactin in cells expressing 611-CTF, we first co-stained cells with anti-cortactin and anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies and showed that co-localization was particularly apparent at cell protrusions (Fig. 6B). To refine this analysis, we used an antibody that specifically recognizes mouse cortactin when the tyrosine 421 residue is phosphorylated. Analysis of the levels of transfected cortactin phosphorylated at this residue confirmed the involvement of 611-CTF in the regulation of cortactin (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, cortactin phosphorylated at tyrosine 421 accumulated near the cell surface, at the cellular protrusions induced by 611-CTF (Fig. 6D). Since cortactin is considered a marker for invadopodia (24–26), and the cellular protrusions observed resembled these invasive structures, we concluded that 611-CTF probably induces the generation of invadopodia, the phosphorylation of cortactin, and its relocalization to these structures.

Cortactin Is Required for the Migration of Cells Induced by 611-CTF

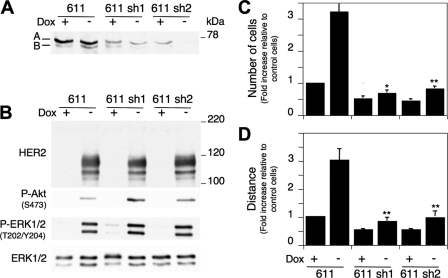

To determine if cortactin is required for the cell migration induced by 611-CTF, we stably transfected MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells with a vector encoding short hairpin RNA targeting cortactin or, as a control, with empty vector.

In the presence of doxycycline, two independent clones showed levels of cortactin ∼3.5- and 7-fold lower that those in parental MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells (Fig. 7A) (data not shown). For unknown reasons, the levels of cortactin in the cells transfected with short hairpins were consistently higher in cells treated with doxycycline (Fig. 7A). In agreement with previous reports (27–29), depletion of cortactin led to a decrease in cell migration in parental MCF7 cells (Fig. 7, C and D, compare bars corresponding to cells treated with doxycycline).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of cortactin knock down on the cell migration induced by 611-CTF. A, MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF cells stably transfected with empty vector or a vector containing short hairpin RNA targeting cortactin were treated with or without doxycycline for 48 h and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against cortactin. 611 sh1 and 611 sh2 are two independent clones. B, cells treated as in A were analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. C, the same cells as in A were seeded on transwell plates with or without doxycycline, as indicated. After 24 h, cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and counted. The bars represent the average of the cells counted in three independent experiments, each one performed in triplicate, ± S.D. D, monolayers of the same cells as in C were wounded with a pipette tip. The closure of the wounds was monitored by time lapse microscopy. Bars, means from three independent experiments, each one derived from evaluation of 10 fields, ± S.D. Analysis of the means using Student's t test showed statistically significant differences between MCF7 Tet-Off/611-CTF transfected with empty vector and 611 sh1 and 611 sh2 cells (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.05).

The down-modulation of cortactin did not have any effect on the levels of 611-CTF or its activity as judged by the activation of the Akt and Erk1/2 pathways (Fig. 7B). However, cells with low levels of cortactin showed a profound impairment in cell migration as judged by the transwell and the scratch wound assays (Fig. 7, C and D). Although we also observed a decrease in the cell migration as judged by time lapse microscopy, it was not statistically significant. These results show that cortactin is one of the factors involved in the increase in cell migration induced by 611-CTF and indicate that the regulation of cortactin by 611-CTF probably contributes to the increased likelihood of CTF-expressing patients to develop metastasis.

DISCUSSION

HER2 transmembrane CTFs are a relevant model to characterize overactivation of HER2 in tumor cells. 611-CTF and 648/P95-CTF occur naturally in the tumors of breast cancer patients with a tendency to develop metastasis (8). Both transmembrane CTFs are active, but they activate signaling pathways (including the mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Src, and phospholipase C-γ1 pathways) in a kinetically different manner and to different extents, with 611-CTF being by far the most active.

Moreover, in addition to common genes regulated by HER2, 611-CTF, and 648/P95-CTF, each isoform regulates a specific group of genes. Thus, the characterization of CTFs of HER2 can shed light not only on the pathogenesis of a subgroup of breast cancer patients but also on novel mechanisms and factors controlled by HER2 signaling.

In this paper, we show that, compared with full-length HER2 or 648/P95-CTF, 611-CTF is a potent activator of cell migration. Cell migration is regulated by protein phosphorylation. For example, the phosphorylation of adaptor molecules, such as paxilin (30) or CrkII (31), the heat shock protein 27 (32), or cell adhesion molecules, such as syndecan-4 (33) or α4β1 integrin (34), regulate cell migration. Thus, we looked for factors regulated by 611-CTF likely to participate in cell migration by comparing phosphoproteins, purified by metal affinity chromatography, from control cells or cells expressing the CTF.

SILAC is considered the most accurate way to quantitatively analyze proteins (16). In fact, we were able to detect and confirm small increments in the levels of different proteins, including Bid, p21, and EF2 (Fig. 2), in the phosphoprotein fraction of cells expressing 611-CTF. However, we found that, coupled to metal affinity chromatography, SILAC is not useful to detect changes in multiphosphorylated proteins. Presumably, an increase in the phosphate content of a highly multiphosphorylated protein does not lead to a significant increase in its affinity to the matrix-bound metal and to a subsequent increase in its levels in the purified fraction. In contrast, DIGE seems particularly well suited for this purpose, because it is based on two-dimensional electrophoresis, and typically, protein isoforms that differ even in only one phosphate are resolved in this type of electrophoresis. This was best exemplified by the case of cortactin; because of its high constitutive phosphate content, the increment in phosphorylation induced by 611-CTF was not enough to increase its binding to the metal affinity matrix, and the levels were similar in the phosphoprotein fraction from control cells or cells expressing 611-CTF (Fig. 4, A and B). However, analysis of the same samples by DIGE clearly identified the increase in the levels of the more acidic, albeit minor, spot (Fig. 4, C and D).

Among the different proteins identified by DIGE, we selected cortactin for further analysis, because it is clearly involved in the regulation of cell migration and invasion. Cortactin binds to and regulates the assembly of branched cytoskeletal filaments by interacting with actin and with the actin-related proteins 2 and 3 (Arp2/3) complex, (recently reviewed in Ref. 17). Cortactin is considered a major component of the subcellular protrusions associated with degradation of the extracellular matrix known as invadopodia, and it is required for migration of cells induced by CD44 or EGF (27–29). The tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin correlates with enhanced cell migration and metastasis (reviewed in Ref. 20). Conversely, inhibition of the tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin impairs cell migration and metastasis (reviewed in Ref. 20).

Confirming a role of cortactin in 611-CTF-induced cell migration, we showed that, concomitantly with an increase in cell migration, expression of 611-CTF led to the phosphorylation of cortactin and the generation of invadopodia-like structures. Furthermore, down-modulation of cortactin expression did not affect the signaling ability of 611-CTF but severely impaired the increase in cell migration (Fig. 7).

In addition to Src, which seems to be the major contributor, several kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases, can phosphorylate cortactin (20). We have recently shown that 611-CTF is a potent activator of Src and Erk1/2 (see also Fig. 7B); thus, in addition to direct phosphorylation, 611- CTF may regulate cortactin through the activation of different kinases that, in turn, phosphorylate the cytoskeleton-binding protein. This possibility seems particularly likely in the case of the tyrosine kinase receptor Met, which is up-regulated by 611-CTF and has also been shown to phosphorylate cortactin (35). In contrast to non-expressing cells, cells expressing 611-CTF display a scattered distribution (i.e. they are separated from one another) (Figs. 5D and 6). This distribution is similar to that induced in cells treated with hepatocyte growth factor, the ligand for the Met receptor, also known as scatter factor, precisely because of this property (36), indicating that 611-CTF expression may lead to the up-regulation and subsequent activation of Met. Thus, it is possible that in addition to directly phosphorylating cortactin, 611-CTF regulates cell migration and cortactin phosphorylation through Met.

Since 611-CTF preferentially forms homodimers maintained by disulfide bonds and apparently does not interact with HER3 (data not shown), our results indicate that HER2 homodimers are responsible for the increase in cell migration. Assuming that enhanced cell migration favors metastasis, this result is in agreement with the increased likelihood of metastasis in patients expressing CTFs or high levels of full-length HER2 that are expected to form HER2 homodimers. Thus, we suggest that the regulation of cortactin by 611-CTF may contribute to the increased likelihood of metastasis observed in a subset of breast cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Intrasalud PI081154 and the network of cooperative cancer research), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and La Marató de TV3 (to J. A.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2, Figs. S1 and S2, and Movies S1 and S2.

- CTF

- carboxyl-terminal fragment

- DIGE

- difference gel electrophoresis

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- Dox

- doxycycline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yarden Y., Sliwkowski M. X. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spencer K. S., Graus-Porta D., Leng J., Hynes N. E., Klemke R. L. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 385–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt B. H., Roetger A., Dittmar T., Nikolai G., Seeling M., Merschjann A., Nofer J. R., Dehmer-Möller G., Junker R., Assmann G., Zaenker K. S. (1999) FASEB J. 13, 1939–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dittmar T., Husemann A., Schewe Y., Nofer J. R., Niggemann B., Zänker K. S., Brandt B. H. (2002) FASEB J. 16, 1823–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan C. X., Lasut A. L., Wynn R., Neff N. T., Hollis G. F., Ramaker M. L., Rupar M. J., Liu P., Meade R. (2003) Protein Expr. Purif. 29, 217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anido J., Scaltriti M., Bech Serra J. J., Josefat B. S., Todo F. R., Baselga J., Arribas J. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 3234–3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen K., Angelini P. D., Laos S., Bach-Faig A., Cunningham M. P., Ferrer-Ramón C., Luque-García A., García-Castillo J., Parra-Palau J. L., Scaltriti M., Ramón y Cajal S., Baselga J., Arribas J. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 3319–3331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molina M. A., Sáez R., Ramsey E. E., Garcia-Barchino M. J., Rojo F., Evans A. J., Albanell J., Keenan E. J., Lluch A., García-Conde J., Baselga J., Clinton G. M. (2002) Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 347–353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kersey P. J., Duarte J., Williams A., Karavidopoulou Y., Birney E., Apweiler R. (2004) Proteomics 4, 1985–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007) Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bech-Serra J. J., Santiago-Josefat B., Esselens C., Saftig P., Baselga J., Arribas J., Canals F. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5086–5095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusnak D. W., Affleck K., Cockerill S. G., Stubberfield C., Harris R., Page M., Smith K. J., Guntrip S. B., Carter M. C., Shaw R. J., Jowett A., Stables J., Topley P., Wood E. R., Brignola P. S., Kadwell S. H., Reep B. R., Mullin R. J., Alligood K. J., Keith B. R., Crosby R. M., Murray D. M., Knight W. B., Gilmer T. M., Lackey K. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 7196–7203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scaltriti M., Verma C., Guzman M., Jimenez J., Parra J. L., Pedersen K., Smith D. J., Landolfi S., Ramón y Cajal S., Arribas J., Baselga J. (2009) Oncogene 28, 803–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong S. E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D. B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Bergh G., Arckens L. (2004) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everley P. A., Zetter B. R. (2005) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1059, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver A. M. (2008) Cancer Lett. 265, 157–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uetrecht A. C., Bear J. E. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rossum A. G., Moolenaar W. H., Schuuring E. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 1658–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lua B. L., Low B. C. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 577–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H., Parsons J. T. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 120, 1417–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowden E. T., Onikoyi E., Slack R., Myoui A., Yoneda T., Yamada K. M., Mueller S. C. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 1240–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb B. A., Jia L., Eves R., Mak A. S. (2007) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 189–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bharti S., Inoue H., Bharti K., Hirsch D. S., Nie Z., Yoon H. Y., Artym V., Yamada K. M., Mueller S. C., Barr V. A., Randazzo P. A. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 8271–8283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark E. S., Whigham A. S., Yarbrough W. G., Weaver A. M. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 4227–4235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onodera Y., Hashimoto S., Hashimoto A., Morishige M., Mazaki Y., Yamada A., Ogawa E., Adachi M., Sakurai T., Manabe T., Wada H., Matsuura N., Sabe H. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 963–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryce N. S., Clark E. S., Leysath J. L., Currie J. D., Webb D. J., Weaver A. M. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 1276–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill A., McFarlane S., Mulligan K., Gillespie H., Draffin J. E., Trimble A., Ouhtit A., Johnston P. G., Harkin D. P., McCormick D., Waugh D. J. (2006) Oncogene 25, 6079–6091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothschild B. L., Shim A. H., Ammer A. G., Kelley L. C., Irby K. B., Head J. A., Chen L., Varella-Garcia M., Sacks P. G., Frederick B., Raben D., Weed S. A. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 8017–8025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petit V., Boyer B., Lentz D., Turner C. E., Thiery J. P., Vallés A. M. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 957–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takino T., Tamura M., Miyamori H., Araki M., Matsumoto K., Sato H., Yamada K. M. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 3145–3155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin K. D., Lee M. Y., Shin D. S., Lee S., Son K. H., Koh S., Paik Y. K., Kwon B. M., Han D. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41439–41448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhuri P., Colles S. M., Fox P. L., Graham L. M. (2005) Circ. Res. 97, 674–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldfinger L. E., Han J., Kiosses W. B., Howe A. K., Ginsberg M. H. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 731–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crostella L., Lidder S., Williams R., Skouteris G. G. (2001) Oncogene 20, 3735–3745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesko E., Majka M. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 1271–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.