Abstract

The 2.8-Å crystal structure of the complex formed by estradiol and the human estrogen receptor-α ligand binding domain (hERαLBD) is described and compared with the recently reported structure of the progesterone complex of the human progesterone receptor ligand binding domain, as well as with similar structures of steroid/nuclear receptor LBDs solved elsewhere. The hormone-bound hERαLBD forms a distinctly different and probably more physiologically important dimer interface than its progesterone counterpart. A comparison of the specificity determinants of hormone binding reveals a common structural theme of mutually supported van der Waals and hydrogen-bonded interactions involving highly conserved residues. The previously suggested mechanism by which the estrogen receptor distinguishes estradiol’s unique 3-hydroxy group from the 3-keto function of most other steroids is now described in atomic detail. Mapping of mutagenesis results points to a coactivator-binding surface that includes the region around the “signature sequence” as well as helix 12, where the ligand-dependent conformation of the activation function 2 core is similar in all previously solved steroid/nuclear receptor LBDs. A peculiar crystal packing event displaces helix 12 in the hERαLBD reported here, suggesting a higher degree of dynamic variability than expected for this critical substructure.

Steroid and nuclear hormones exert their influence on target cells by binding to cognate members of the steroid/nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors (Fig. 1A). Members of this family are modular in structure with domains A-F, including discrete DNA binding domains and ligand binding domains (LBDs) (3, 4). The receptors are targeted to their respective promoters through specific interaction with cognate hormone response elements (3, 4), and regulate transcription in a ligand-dependent manner with the aid of various coactivators and corepressors (5–8). Additional levels of regulation are achieved through interactions with other systems such as molecular chaperones (4), cAMP-regulated kinases (9, 10), and AP1 activators (4, 11, 12). Members of this superfamily also regulate each other’s expression through complex crosstalk pathways (13, 14). Together these form a rich and elaborate network by which lipophilic ligands regulate gene expression.

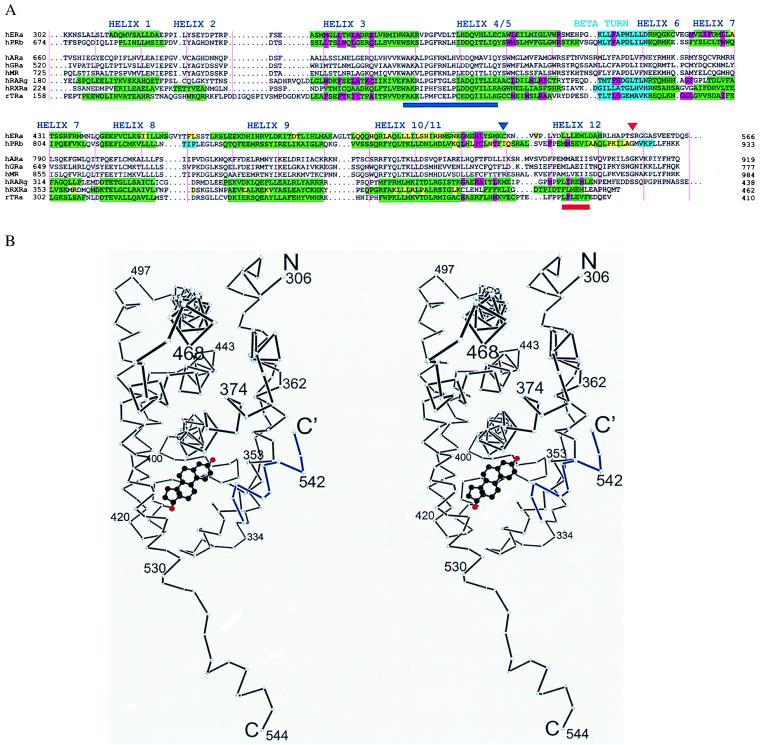

Figure 1.

(A) Sequence alignment of LBDs from selected steroid and nuclear receptors. Secondary structure determined by crystallography is in green (α helix) and cyan (β sheet). Residues are highlighted by function: magenta (hormone binding), yellow (dimerization), or brown (hormone contacts C-terminal to Cys530 in the hERαLBD) (1). Helix 12 is shown as described by Brzozowski et al. (1). A red triangle shows the C terminus of the hERαLBD used for crystallization, and a navy blue triangle indicates the position of the intermolecular disulfide bond. The activation function 2 core and “signature sequence” (2) are underlined in red and navy blue, respectively. Vertical pink lines denote every 10 residues. (B) Stereo plot of the Cα backbone of a hERαLBD subunit with bound estradiol (carbons black, oxygens red) presented here. Helix 12 from a neighboring molecule is in blue. Drawn with dplot (G. Van Duyne, personal communication).

The transcriptional response to hormones or antihormones is rooted in conformational changes induced by specifically bound ligands. These changes have been implicated by biochemical and genetic analysis to be involved in transactivation, dimerization, phosphorylation, chaperone interaction, and corepressor inhibition (4). To better understand the molecular mechanism of these responses in chemical terms, crystallographic analysis has been carried out elsewhere on the liganded LBDs of two nuclear receptors, the all-trans retinoic acid receptor (RAR) (15) and the thyroid hormone receptor (TR) (16), and on the unliganded 9-cis retinoic acid receptor (RXR) (17). To extend the structure-function analysis to the steroid subfamily we present here a comparison of the 2.8-Å crystal structure of the estradiol complex of the human estrogen receptor α LBD (hERαLBD) and the progesterone complex of the human progesterone receptor LBD (hPRLBD) (18). A parallel study of the estradiol and raloxifene complexes of hERαLBD recently was published (1), the descriptions of which also are used in the comparison.

Materials and Methods

A fragment of the human ERα (residues 297–554) that contains the entire ligand binding (“E”) domain with an N-terminal three residue (MDP) extension was overexpressed with pET23d in BL21(DE3)pLys S and purified in 5 M urea by estradiol-affinity chromatography (19) with 10 mM ammonium chloride added to prevent carbamylation of lysine residues. The purified product [a complex of hERαLBD with estradiol in 25 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5 M urea, 10 mM NH4Cl, 20 μM estradiol] was exchanged into 25 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 20 μM estradiol, 0.1% β-octyl glucoside via multiple dialysis steps and concentrated by ultrafiltration to 18 mg/ml. Crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion at 18°C using hanging drops containing an 8-μl 1:1 mixture of the above protein stock solution and a well solution composed of 100 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 480 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Mg acetate, 10% ethylene glycol, 5% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000. Triangular prisms (space group R32; a = b = 147 Å, c = 338 Å in the hexagonal setting; two dimers per asymmetric unit) grew to full size (150 × 150 × 300 microns) in 14 days and diffracted to 3.2 Å. When this same crystal form was stabilized in 0.1 to 10 mM potassium aurocyanide, a new unit cell formed that had the same space group and a and b axes, but had a halved c axis of 169 Å. Crystals were stabilized in 100 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 510 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Mg acetate, 10% ethylene glycol, 5.5% PEG 4000, 10 mM KAu(CN)2 for 18 hr at 18°C; cryoprotected by a 15-sec equilibration in 100 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 510 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Mg acetate, 25.5% ethylene glycol, and 5.5% PEG 4000, and flash-frozen in liquid propane at liquid nitrogen temperatures. X-ray data were collected at 90–110 K in a nitrogen gas stream. Anomalous diffraction data were collected at NSLS beamline X4a on image plates at the gold LIII edge. Initial phases were obtained by single wavelength anomalous scattering (SAS) based on gold sites determined from an anomalous difference Patterson synthesis. Using the gold adduct as the parent, phases were improved by multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) with derivatives produced in the presence of 0.1–1 mM KAu(CN)2 for 12 hr followed by 6 hr in a stabilizer with KAu(CN)2 and a second heavy metal (0.1 mM Au for ethyl mercury chloride, 1 mM Au for mersalyl and trimethyl lead acetate). Data from CHESS-A1 were collected on a 1 K × 1 K charge-coupled device at 0.91 Å. Home-source data were collected by using a Macscience DIP2000 image plate detector and mirror-conditioned Cu Kα. All data were processed by denzo (20) and merged with scalepack (20). Mercury and lead sites were found by difference Fourier synthesis, and heavy atom parameters were refined with ml-phare (21). Combined SAS and MIR phases were further improved by solvent flattening (22) using dphase (G. Van Duyne, personal communication) and by averaging density related by the noncrystallographic dyad with rave (23). The model was built with o (24) and refined by cns (25) by using a maximum likelihood target, bulk solvent correction, simulated annealing, noncrystallographic symmetry constraint and restraint, and restrained individual B factors. The structure was refined to an R factor of 22.3% and free R factor of 27.4%. See Table 1 for details on data collection and refinement.

Table 1.

Crystallographic analysis

| Data collection | ||||

| Data set | Parent | Mersalyl | Me3PbAC | EtHgCl |

| X-ray source | NSLS X4a | Laboratory | CHESS-A1 | CHESS-A1 |

| Wavelength | 1.0397 Å | 1.54 Å | 0.91 Å | 0.91 Å |

| Resolution | 50-2.8 Å | 40-3.5 Å | 40-3.0 Å | 40-4.0 Å |

| Unique refl | 33,401 | 8,827 | 14,560 | 6,029 |

| Completeness | 99.1% | 97.9% | 99.3% | 97.1% |

| Rsym | 6.8% | 10.5% | 7% | 6.1% |

| Reagent conc.* | 1 mM | 2.5 mM | 1 mM | |

| Soaking time* | 6 h | 6 h | 5 h | |

| Number of sites | 4 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Phasing power† | 1.45 | 1.11 | 1.1 | |

| Anomalous phasing power† | 0.5 | |||

| Mean f.o.m. 0.45 acentric/0.59 centric | ||||

| Refinement 50-2.8 Å (2σ data) | ||||

| Working R factor: 22.3% Free R factor: 27.4% | ||||

| Rms deviations Bond lengths 0.014 Å Bond angles 1.68° | ||||

Rsym = Σ|Ih− 〈Ih〉|/Σ Ih, where 〈Ih〉 is the average intensity over Friedel and symmetry equivalents. Phasing power = Σ|FH|/Σ∥FPHobs |−|FPHcalc∥. Anomalous phasing power Σ|FH|/Σ∥ADobs|−|ADcalc ∥, where AD is the Bijvoet difference. NSLS is the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, and CHESS is the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source.

See the Materials and Methods section for full details.

Acentric.

Overall Architecture

There are two ERαLBDs in the crystallographic asymmetric unit related by a nearly exact noncrystallographic dyad. This arrangement, which resembles that of unliganded RXR, likely represents the physiologically relevant homodimeric form of ERα in estrogen-dependent transcriptional activation (26), and corresponds to the stoichiometry and rotational symmetry of the ER’s DNA target (27). The fold of the individual ERαLBD is roughly similar to that seen in the structures of other liganded LBDs in the steroid/nuclear superfamily (1.2-Å rms deviation for ER vs. PR for helices 1–11). However, helix 12, which is not essential for the ligand binding or dimerization properties of the ERαLBD (28), extends away from the body of the domain and binds to the surface of a neighboring molecule (Figs. 1B and 2A). This intermolecular contact is somewhat similar to the intramolecular binding mode of helix 12 in the raloxifene-bound hERαLBD (1), where the antiestrogen displaces helix 12 from its position in the estradiol-bound complex. This artifactual interaction is caused by the perturbing effect of a fortuitous disulfide bond formed between the loops just preceding helix 12 in neighboring molecules as shown in Fig. 2A. The aberrant position of helix 12 seen in our hERαLBD structure underscores the high degree of positional variability exhibited by this important and inherently stable substructure.

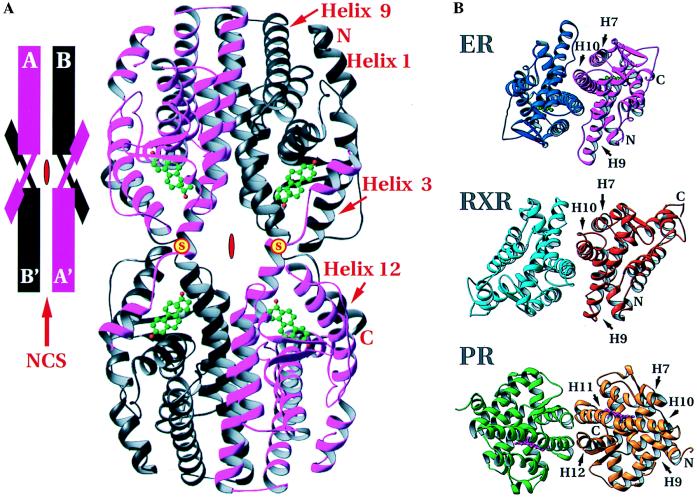

Figure 2.

Arrangement of hERαLBDs in the crystal structure. (A) The tetramer formed by the intermolecular disulfide bonds between Cys-530 of neighboring hERαLBD molecules and dimerization around the local dyad. (Inset) A schematization of the arrangement. Positions of the disulfides are marked with a yellow disc with red “S.” Red symbols in the center of the tetramer and schematic show the crystallographic dyad, and the red arrow in the inset indicates the noncrystallographic symmetry dyad. (B) Comparison of the dimers of holo-hERαLBD, apo-hRXRαLBD, and holo-hPRLBD viewed down the local dyad (17, 18). The dimer interfaces of holo-hERαLBD and apo-hRXRαLBD are similar, with helices 7–10 as the major contributors. The holo-hPRLBD dimer interface is substantially different, composed predominantly of helices 11 and 12, as well as the extreme C-terminal tail. Drawn with ribbons (29).

Dimer Interface

Fig. 2B shows the mode of hERαLBD dimerization and its similarity to that seen in the crystal structure of the unliganded hRXRαLBD. The dimer interface observed here has been shown by mutagenesis to be essential for ER dimer formation (28, 30). In the hERαLBD, each protomer contributes 1,477 Å2, or roughly 13.3% of its solvent-accessible surface area to the interface, which is comparable to the 1,333 Å2, or roughly 11.2% of solvent-accessible surface contributed to the dimer interface of apo-hRXRα (17). Both of these interfaces are larger than that seen in the hPRLBD, which buries 705 Å2 of surface for each protomer (18). The much smaller dimer interface of the hPRLBD (18) is distinctly different (Fig. 2B), as the β-structure formed by the C-terminal strand of the hPRLBD intrudes on the homodimer interface seen in the LBD crystal structures of hERα and hRXRα. Gel filtration experiments on a slightly longer fragment of hERαLBD (297–566) confirm that the estradiol-bound hERαLBD is a dimer in solution, whereas the progesterone-bound hPRLBD used for the crystal structure elutes as a monomer (data not shown).

The hERαLBD dimer interface contains residues from helices 7, 8, and 9 as well as the loop between helices 8 and 9, but is dominated by a conserved hydrophobic region at the N terminus of helix 10/11 that forms a right-handed convex interhelical contact similar to that in resolvase (31), but with a smaller crossing angle (∼40° for resolvase versus ∼29° for ER). This is distinctly different than the left-handed coiled-coil predicted on the basis of the leucine-containing heptad repeat sequences in the ER and TR LBDs (28). Nuclear receptors such as RAR, TR, and 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 receptor are likely to form heterodimers with ER/RXR-like dimer interfaces because the residues that correspond to those in the dimer interfaces seen in the hERα and hRXRα crystal structures are highly conserved in these receptors and have been implicated in dimerization by mutagenesis (17, 32–35).

Hormone Specificity

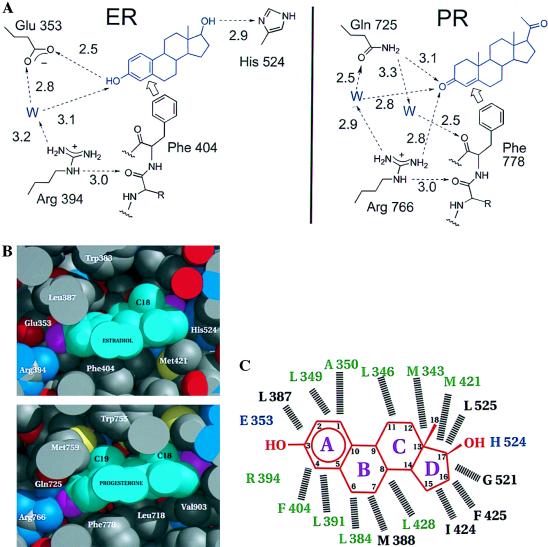

In the hERα and hPR ligand-binding pockets, the hormone is oriented by two types of contacts: hydrogen bonding at the two ends and hydrophobic van der Waals contacts along the body of the hormone. Estradiol and its analogues are unique in having a 3-hydroxyl group as opposed to the 3-keto group found in other steroids. The uniqueness of this estrogenic functionality is reflected in the hydrogen-bonding pattern of the hERα and hPR ligand-binding pockets shown in Fig. 3A and ref. 1. At the end of the binding pocket that holds the A-ring of the steroid, the estrogen receptor is unique in having a glutamate (Glu-353) to accept the hydrogen bond donated by the estrogenic 3-hydroxyl group. The other steroid receptors, which bind 3-keto steroids, have a conserved glutamine at the corresponding sequence position where the hPRLBD structure shows the amido NH2 group of the Gln-725 donating a hydrogen bond to the 3-keto group of progesterone (18). Fig. 3A also shows how the conserved arginine (Arg-394 in hERα, Arg-766 in hPR) serves to correctly orient and position the discriminating glutamate or glutamine side chain via highly polarized, water-mediated hydrogen bonds. Through a nearly identical structural arrangement in the hERαLBD and hPRLBD, the side chain of this arginine is itself braced by a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl of the residue preceding a conserved phenylalanine (Phe-404 in hERα, Phe-778 in hPR), which is fixed by its van der Waals contact to the A-ring of the steroid (Fig. 3 B and C). Thus, the recognition of the 3-oxy function of the hormone is coordinated with a van der Waals contact to its hydrophobic rings. At the other end of the ligand, however, the mechanism of discrimination is less clear. In the hERαLBD, the 17-hydroxyl is hydrogen-bonded to the δ nitrogen of His-524 (Fig. 4; ref. 1), whereas the hPRLBD (18) possesses a less definite discriminating functionality for progesterone’s 17-methyl-keto moiety (Fig. 3A). The hormone is positioned in the same orientation in the hERαLBD as in the hPRLBD (18), but both are in the opposite direction to that predicted on the basis of the nuclear receptor structures (2).

Figure 3.

Specificity determinants of the hormone-binding site specifies 3-hydroxy vs. 3-keto steroids. (A) The hydrogen-bonding network as seen in the hERαLBD and hPRLBD (18). The discriminating relationship of Glu/Gln to the 3-hydroxy/keto of the steroid is supported by a network of water-mediated hydrogen bonds involving the side chain of a conserved Arg and backbone carbonyl of a conserved Phe that, in turn, are fixed by hydrophobic contacts with the steroid ring. Note that the PR has no obvious hydrogen bonding discrimination at the 20-keto position of progesterone comparable to the hydrogen-bonding interaction seen between the 17-hydroxyl of estradiol and His-524. (B) Space-filling representation of estradiol in the ligand-binding pocket of hERαLBD and progesterone in the ligand-binding pocket of hPRLBD (18). For the proteins, carbon atoms are gray, oxygen atoms red, sulfur atoms yellow and nitrogen atoms blue. For the hormones, carbon atoms are cyan, oxygen atoms magenta. Drawn with midas (36). (C) Schematic of estradiol in the hERαLBD ligand-binding pocket in the structure shown here; hormone (red) rings are lettered, and carbon atoms are numbered. Residues hydrogen bonded directly to the hormone are blue. Dashed lines indicate hydrophobic van der Waals contacts with the hormone. Residues conserved among the steroid receptors are green, and variable residues are black. Residues contributed by helix 12 (1) are not shown.

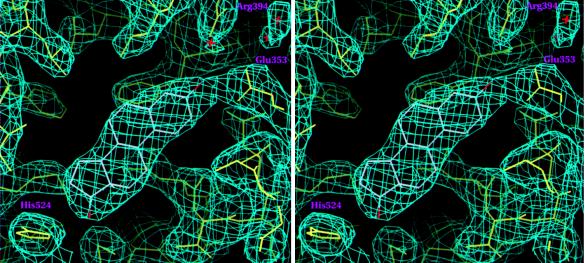

Figure 4.

A stereo view of the 2Fo-Fc Sigma A weighted (37) electron-density map contoured at 1.2σ showing estradiol in the hERαLBD hormone-binding pocket. Drawn with setor (38).

The hydrophobic residues implicated in direct hormone binding in the ER and PR structures are highly conserved (Figs. 1A and 3C), indicating a commonality of pocket architecture. Eighteen residues in ER contact bound estradiol; of those 18 sequence positions 14 are occupied by PR residues that contact bound progesterone and 10 of those have similar side chains in all of the steroid receptors (Fig. 3C). The variations in the van der Waals surface of the binding pocket, however, appear designed to complement the distinctive contours of the cognate hormone. A flat aromatic A-ring, and the absence of a 19-methyl group protruding from its surface distinguish the van der Waals surface of the estradiol molecule. Fig. 3B shows that the bulky side chain of Leu-387 in the ER’s binding pocket is replaced by the slender, more flexible methionine side chain in PR to accommodate progesterone’s 19-methyl group. These variations on a common theme indicate that it is highly unlikely that the natural ligands of the steroid receptor subfamily bind in a mode that is substantially different than that seen in the ER and PR.

The cooperative stereochemistry of ligand binding provided by the network of specific hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts underscores the importance of ligand-induced stability in the steroid/nuclear receptor superfamily. Note that the absence of hormone from the hERα and hPR LBDs would leave cavities of 450 Å3 (1) and 603 Å3 (18), respectively and thus would require significant readjustments to retain stability of the hydrophobic interior of the domain. In the two hormone-bound LBDs discussed here, it is clear that this cooperative network of hormone contacts not only accounts for the specificity of ligand binding, but allows the hormone to function as the structural core for the bottom half of the LBD, and therefore the scaffold around which this region folds.

Coactivator Binding

Coactivators are necessary for the hormone-bound ER and PR to stimulate transcription (39). The ligand-dependent interaction between steroid/nuclear receptors and coactivators depends on the activation function 2 (AF-2) core located in helix 12 (40). Crystal structures comparing the unliganded LBD from RXR and its liganded counterpart from RAR indicate that the bound hormone induces a dramatic repositioning of helix 12 (15, 17). Except for the artefactual alignment of helix 12 in the ER complex reported here, the structures of all hormone-bound LBDs solved to date (RAR, TR, ER, and PR) shows helix 12, and hence the AF-2 core in the same position (1, 15–18). Importantly, the crystal structure of the antiestrogen, raloxifene, bound to the hERαLBD (1), as well as modeling of the antiprogestin, RU486, bound to the hPRLBD (18), shows a displacement of helix 12 from this common “active” position, thereby reinforcing the generally accepted view that the active state produced by the hormone is caused by the contribution of the conserved helix 12 to a coactivator-binding surface. Helix 12 is fixed in this active position both by contacts with the hormone and residues on the surface of the domain (Fig. 5). The stabilizing effect originally attributed to an ionic interaction in RARγ between the conserved glutamate of the AF-2 core and a lysine in helix 4 does not seem to be general (15). In TRα, ERα, and PR, stability appears to arise from hydrophobic van der Waals contact between the invariant hydrophobic side chain that follows the conserved glutamate of helix 12 and the hydrophobic components of the side chains from helix 4 (1, 16, 18). In addition to helix 12, residues in ERα such as Lys-362 (41) and Val-364 (42) in the highly conserved loop between helices 3 and 4 [the so-called “signature sequence” (2) indicated in Fig. 1A] have been implicated by mutagenesis as contributing to a substructure responsible for coactivator interaction. These results suggest a coactivator-binding interface that appears to encompass the exposed surfaces of helices 3, 4, and 12, and the “signature sequence” loop, as seen in Fig. 5.

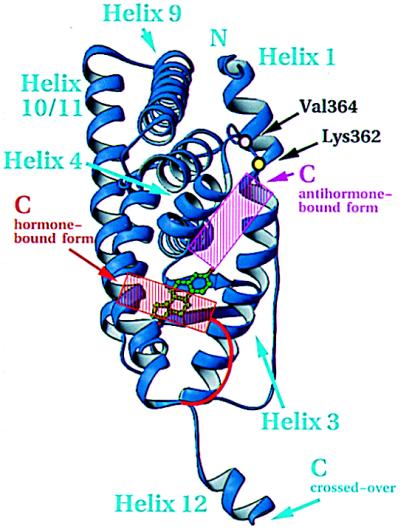

Figure 5.

Inferred coactivator-binding surface. View of hormone-bound hERαLBD and residues important for transactivation as determined by mutagenesis. The active (red) and inactive (magenta) positions of helix 12, red and magenta, are based on the published figures of the hormone- and antihormone-bound hERαLBD structures (1). The domain is oriented as in Fig. 1B. Drawn with ribbons (29).

Hormone-dependent activation is predicated on the movements of helix 12 from one position to another. It is noteworthy in this regard that helix 12 as seen in the unliganded RXR, the raloxifene complex of ER (1), and the aberrant interaction reported here, as well as in its hormone-stabilized active state, retains its structure irrespective of its position. Unlike most helices in globular proteins, the integrity of helix 12 is independent of specific stabilizing tertiary interactions. The positional variability of this robust substructure appears to be a critical attribute of the steroid/nuclear receptors in their variable response to both natural and synthetic ligands.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniel Gewirth for important contributions early in the project, Dr. Geoff Greene (University of Chicago) for supplying the plasmid from which the final construct was derived and the estrogen affinity column, Drs. Craig Ogata (NSLS X4a) and Steve Ealick (CHESS-A1) for synchrotron access, Dr. Roderick Hubbard (University of York, United Kingdom) for providing a stereo diagram of helix 12, and Drs. Dino Moras (Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Ilkirch, France) and Robert Fletterick (University of California, San Francisco) for coordinates of the liganded hRARγ and rTRα LBDs, respectively. D.M.T. was a National Institutes of Health predoctoral trainee (GM07227), and Y.W. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM15225.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- PR

progesterone receptor

- ER

estrogen receptor

- hERαLBD

human estrogen receptor-α LBD

- hPRLBD

human progesterone receptor LBD

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- TR

thyroid hormone receptor

- RXR

retinoic acid receptor

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Biology Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973 (reference nos. 1A52 and R1A52SF).

References

- 1.Brzozowski A M, Pike A C W, Dauter Z, Hubbard R E, Bonn T, Engström O, Öhman L, Greene G L, Gustafsson J, Carlquist M. Nature (London) 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wurtz J M, Bourguet W, Renaud J P, Vivat V, Chambon P, Moras D, Gronemeyer H. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:87–94. doi: 10.1038/nsb0196-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangelsdorf D J, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans R M. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzenellenbogen J A, Katzenellenbogen B S. Chem Biol. 1996;3:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thénot S, Henriquet C, Rochefort H, Cavaillès V. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12062–12068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J D, Evans R M. Nature (London) 1995;377:454–457. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horlein A J, Naar A M, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, Kurokawa R, Ryan A, Kamei Y, Soderstrom M, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. Nature (London) 1995;377:397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith C L, Nawaz Z, O’Malley B W. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:657–666. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Tanani M K K, Green C D. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:928–937. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.7.9939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, Auricchio F. EMBO J. 1996;15:1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G. Cell. 1995;83:851–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper G G, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J, Kushner P J, Scanlan T S. Science. 1997;277:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roman S D, Ormandy C J, Manning D L, Blamey R W, Nicholson R I, Sutherland R L, Clarke C L. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5940–5945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nardulli A M, Greene G L, O’Malley B W, Katzenellenbogen B S. Endocrinology. 1988;122:935–944. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-3-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renaud J P, Rochel N, Ruff M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Nature (London) 1995;378:681–689. doi: 10.1038/378681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner R L, Apriletti J W, McGrath M E, West B L, Baxter J D, Fletterick R J. Nature (London) 1995;378:690–697. doi: 10.1038/378690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourguet W, Ruff M, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Nature (London) 1995;375:377–382. doi: 10.1038/375377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams, S. P. & Sigler, P. B. (1998) Nature (London), in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Seielstad D A, Carlson K E, Katzenellenbogen J A, Kushner P J, Greene G L. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:647–648. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.6.8592511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otwinowski Z. In: Data Collection and Processing. Sawyer L, Isaacs N, Baily S W, editors. Warrington, U.K.: Science and Engineering Council/Daresbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collaborative Computing Project Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abahams J P, Leslie A G W. Acta Crystallogr D. 1996;52:30–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995008754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleywegt G T, Jones T A. In: From First Map to Final Model (CCP4) Baily S, Hubbard R, Waller D, editors. Warrington, U.K.: Science and Engineering Council/Daresbury Laboratory; 1994. pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones T A, Zou J Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;42:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams P D, Pannu N S, Read R J, Brunger A T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar V, Chambon P. Cell. 1988;55:145–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwabe J W, Chapman L, Finch J T, Rhodes D. Cell. 1993;75:567–578. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90390-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fawell S E, Lees J A, White R, Parker M G. Cell. 1990;60:953–962. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90343-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson M. J Appl Crystallogr A. 1991;24:958–961. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lees J A, Fawell S E, White R, Parker M G. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5529–5531. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang W, Steitz T A. Cell. 1995;82:193–207. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forman B M, Yang C R, Au M, Casanova J, Ghysdael J, Samuels H H. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1610–1626. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-10-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishikawa J, Kitaura M, Imagawa M, Nishihara T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:606–611. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeDouarin B, Zechel C, Garnier J M, Lutz Y, Tora L, Pierrat P, Heery D, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P, Losson R. EMBO J. 1995;14:2020–2033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perlmann T, Umesono K, Rangarajan P N, Forman B M, Evans R. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:958–966. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.8.8843412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Computer Graphics Laboratory, University of California, San Francisco. midasplus. San Francisco: Univ. of California; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed R J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1986;42:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans S V. J Mol Graphics. 1993;11:134–138. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(93)87009-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glass C K, Rose D W, Rosenfeld M G. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:222–232. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danielian P S, White R, Lees J A, Parker M G. EMBO J. 1992;11:1025–1033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henittu P M A, Kalkhoven E, Parker M G. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1832–1839. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McInerney E M, Ince B A, Shapiro D J, Katzenellenbogen B S. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1519–1526. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]