Abstract

Objectives

We sought to examine racial and ethnic disparities in police-reported intimate partner violence (IPV) and hospitalization rates and rate ratios among women with police-reported IPV relative to those without such reports.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study linked adult male-to-female IPV police records of non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white women residing in a south central U.S. city with regional hospital discharge data. Rates and incidence rate ratios (IRR) were calculated and age-adjusted where the data allowed.

Results

Police-reported IPV rates were 2 to 3 times higher among black and Hispanic women compared to white women. Overall, hospitalization rates were higher among black and white victims and lower among Hispanic victims than their counterparts in the comparison group (age-adjusted [a] IRR 1.23, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–1.41; aIRR 1.46, CI 1.19–1.79; and aIRR 0.68, CI 0.54–0.86, respectively). Rate ratios were significant for victims among 1) white women for any mental disorder (aIRR 2.02, CI 1.30–3.13) and for episodic mood/depressive disorders in particular (aIRR 2.18, CI 1.33–3.59); 2) black and white women for any injury-related diagnosis (aIRR 2.46, CI 1.48–4.10 and aIRR 3.20, CI 1.65–6.19, respectively); and 3) all women for intentional injury (IRR 10.45, CI 3.56–30.69) and self-inflicted injury (IRR 4.91, 2.12–11.37).

Conclusions

Exposure to IPV as reported to police increases the rate of hospital utilization among Black and white women but lowers the rate for Hispanic women. Screening for IPV in hospitals may identify a substantial number of IPV-exposed women. Primary and secondary prevention efforts related to IPV should be culturally informed and specific.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has a substantial impact on the health of women experiencing victimization as well as on the health care system. Women victims utilize healthcare services not only as a direct result of partner violence, but also for care associated with general medical as well as mental health and substance abuse problems (Campbell, 2002; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003; Petersen, Gazmararian, & Andersen, 2001; Plichta & Falik, 2001; Rivara et al., 2007; Ulrich et al., 2003). Several studies have shown increased nonprimary care use (i.e. emergency department, specialty outpatient, and inpatient hospitalization), in particular, among IPV victims, although the findings with regard to hospitalization have been mixed (Coker, Reeder, Fadden, & Smith, 2004; Kernic, Wolf, & Holt, 2000; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2004; Rivara et al., 2007). For example, the studies by Kernic et al. (2000) and Lipsky et al. (2004) demonstrated increased rates of hospitalization among IPV victims using criminal justice data to identify IPV victims. On the other hand, Coker et al. (2004) and Rivera et al. (2007) found no significant differences in hospitalization rates between women with and without IPV histories in clinical samples. In the study by Coker et al. (2004), however, severe IPV was associated with increased hospital expenditures.

Police-reported incidents of IPV are an important subset of partner violence, as they tend to be more severe than nonpolice-reported incidents, and victims are more likely to have been injured by their partners in those incidents (Bachman & Coker, 1995; McFarlane, Soeken, Reel, Parker, & Silva, 1997; U.S. Department of Justice, 1995). About 1.2 million incidents of IPV against women are reported to police annually, comprising one-fourth to one-half of physical IPV against women and less than one-fifth of intimate partner rape (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000; U.S. Department of Justice, 1995). Only a few studies have examined healthcare utilization using law enforcement or judicial system data to identify IPV victims (Kernic et al., 2000; Lipsky et al., 2004). These studies suggest that abused women are more likely to be hospitalized overall and to be hospitalized with mental health (including substance abuse) diagnoses and injury compared to the general population.

Health outcomes research focused on IPV and racial and ethnic disparities is even rarer. General health care utilization studies have shown that black men and women, and to a lesser extent Hispanics, are more likely to utilize emergency department and inpatient hospital services overall compared to non-Hispanic whites (Friedman & Basu, 2004; Gaskin & Hoffman, 2000; Zuckerman & Shen, 2004), even after adjusting for insurance status (Gaskin & Hoffman, 2000) or employment status (Zuckerman & Shen, 2004). Given the greater risk of severe IPV, including police-reported IPV, among black women (Bachman & Coker, 1995; Cunradi, Caetano, & Schafer, 2002; Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005) and the increased use of non-primary health care among black and Hispanic women, it is reasonable to suggest that black and Hispanic IPV victims in particular are more likely to utilize hospital services compared to their nonvictim counterparts.

This study is unique in its attempt to examine racial and ethnic disparities with regard to the impact of police-reported IPV victimization on women’s health and the healthcare system, providing a broader understanding of these relationships among ethnic minority populations. In addition, identification of abused women using law enforcement data is not dependent on subject recall, self-disclosure to healthcare providers or researchers, or access to healthcare. Further, using police and hospitalization data may better elucidate the relationship between what may be more severe IPV and major mental and physical health problems, including substance abuse.

The primary aims of this study are to (1) estimate rates of police-reported IPV victimization among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women; (2) estimate annual hospitalization rates and rate ratios by police-reported IPV status and race/ethnicity for all hospitalizations and by diagnostic category, including substance abuse, mental disorder, and injury.

Methods

Study Design and Study Population

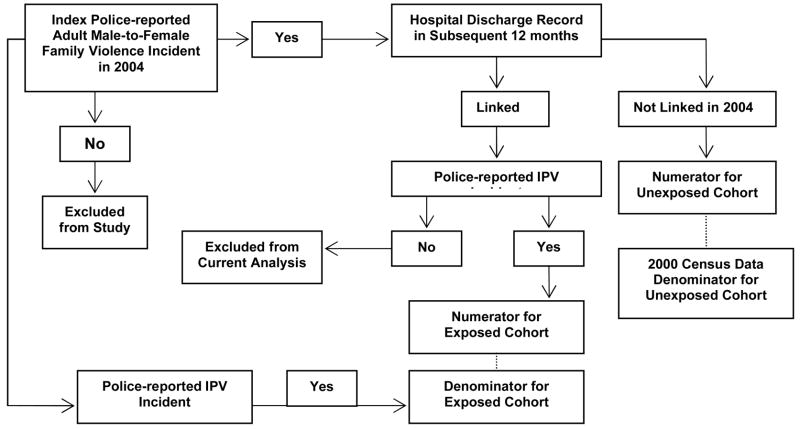

This is population-based retrospective cohort study included non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic black women 18 to 49 years of age residing in Dallas, Texas as the base population. Dallas Police Department family violence incident records were linked to regional hospital discharge records for 2004 and 2005 in the parent study, but only those women reporting an incident perpetrated by a male intimate partner were included in the current analysis (Figure 1). Thus, women residing in Dallas in 2004 who reported an IPV incident perpetrated by a male partner comprised the exposed cohort; these data reflect complainant reporting only, regardless of outcome (arrest or conviction). Women residing in Dallas without such an incident constituted the unexposed cohort or comparison group. The study sample was restricted in terms of age given the substantial decline in IPV victimization in older age groups (Breiding, Black, & Ryan, 2008; Greenfeld et al., 1998; Vest, Catlin, Chen, & Brownson, 2002). Race/ethnicity was restricted since few cases of police-reported family violence occurred in racial/ethnic groups other than white, Hispanic, and black women. This study was approved by the Committee for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board/Human Subjects Review Committee.

Figure 1.

Police-reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Hospitalization Study Flow Chart

Data Sources

Police records

Dallas Police Department computerized offense reports coded as family violence were initially included in the larger study if the victim-suspect relationship was classified as ‘spouse’, ‘ex-spouse’, ‘common-law spouse’, ‘roommate’, ‘other family’, or ‘unknown’. Written narratives from police reports with victim-suspect relationship of ‘roommate’, ‘other family’, and ‘unknown’ were reviewed to determine if an incident occurred between current/ex-intimate partners. Duplicate incidents and incidents which occurred after the index case were identified and deleted from the final police file. Of the 5912 incident cases, 1137 (19.2%) remained without a clear intimate partner relationship in the offense report. Cases with unconfirmed relationships were retained for linkage to hospital discharge records, but only those linkages with an IPV incident record were utilized in this analysis.

Hospital records

Hospital inpatient discharge data for Dallas residents were collected from 73 hospitals licensed by the State of Texas from 19 surrounding counties in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and submitted to a regional data collecting agency, the Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council, before submission to the Texas Department of State Health Services. Hospital discharge records with substance abuse diagnoses are required to be blinded (i.e. data is de-identified prior to release to the Council) in certain cases, for example if the patient is discharged from a substance abuse-designated hospital bed. Therefore, these records could not be linked to police records; by default, they would remain as hospitalizations among the comparison group. An analysis of the 2004 discharge data among females revealed that 1.5% of all hospital discharges were blinded due to substance abuse. Of those hospitalizations with a substance abuse diagnosis, 15.7% were blinded.

Data Linkage

After data linkage, 20 hospitalizations were found to be miscoded on ethnicity (i.e. not belonging to the three ethnic groups) and were excluded from the analysis. The total number of hospital discharges (hereafter referred to as hospitalizations) among the exposed cohort was 766. Women with miscoded ethnicity (n=15) were also removed from the denominator for the hospital analyses. A 10% simple random sample of hospital records among Dallas female residents that did not link to police-reported family violence incidents constituted the numerator for the comparison group; the denominator was derived from females residing in Dallas in the 2000 census (minus the number of family violence exposed women), from which a 10% stratified sample (within each race/ethnicity and age group) was taken. The comparison group consisted of 3831 hospitalizations and 28,050 women.

Measures

Outcome measures

The main outcome in this study was the annual rate of hospitalizations. In addition, rates for specific non-mutually exclusive categories of hospitalization were calculated for 1) an alcohol or other drug use diagnosis; 2) any mental health diagnosis unrelated to substance use; 3) an episodic mood or depressive disorder diagnosis; 4) any injury diagnosis; 5) intentional injury diagnosis (excluding self-inflicted injury); and 6) self-inflicted injury diagnosis.

Up to nine International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and the first external cause of injury (E) code were used to determine the diagnostic categories (see Appendix). Alcohol and other drug use-related codes, excluding tobacco use disorders, comprised the substance abuse disorder category. Mental health-related codes, excluding substance abuse disorders, comprised the mental health disorder category; episodic mood and depressive disorder codes were a subset of mental health disorders. Injury-related ICD-9 codes, excluding late effects of injury and allergic reactions, and E codes for any injury, excluding injury due to surgical and medical care, adverse reaction to correct drug properly administered, and late effects of injury, comprised the injury-related category. Intentional injury-related ICD-9 codes, including adult maltreatment/abuse/neglect, and E codes for homicide and injury purposely inflicted by others comprised the intentional injury category. E codes for suicide and self-inflicted injury comprised the self-inflicted injury category.

Appendix.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes and the first external cause of injury (E) code used to determine diagnostic categories.

| Diagnostic Category | ICD-9 Codes | E Codes | Exclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Abuse Disorders | 291, 303, 305.0, 535.30-31, 571.0-3, 790.3, 292,304, 305, V65.42 | 305.1 (tobacco use disorder) | |

| Mental Health Disorders | 293-316 | Substance Abuse Disorders | |

| Episodic Mood and Depressive Disorders | 296, 311 | ||

| Any Injury | 800-904, 910-995 | E800-848,E850-869, E880-928, E950-998 | 905-909 (late effects); 995.0-995.4, 995.86, 995.89, 995.90- 995.94 (allergic reactions); E870-879 (surgical and medical care), E930-949 (adverse reactions), E929, E999 (late effects) |

| Intentional Injury | 995.80-995.85 | E960-969 | |

| Self-Inflicted Injury | 950-959 |

Exposure Measures

IPV victimization was defined as a Dallas police-reported IPV incident perpetrated by a male with whom the female subject had an intimate relationship at the time of or prior to the incident. The first (index) incident in the study period was selected for linkage with hospital discharge records. If a subject had more than one incident with the same date, the incident with the more serious offense was utilized. Women from the general population of Dallas without a police-reported family violence incident in 2004 were considered nonexposed to police-reported IPV and thus constituted the comparison group.

Sociodemographic measures

Police-reported IPV exposed subjects’ race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic of any race), and age group (18–25, 26–34, 35–49), were initially determined from the police records. Hospitalization records were subsequently used to classify race/ethnicity and age group for the linked records. Agreement between police and hospital records on race/ethnicity was high; 98% of hospitalizations with race/ethnicity coded as black, 96% coded as Hispanic, and 85% coded as non-Hispanic white in the police records matched the race/ethnicity of the linked hospital records. The remainder of those hospitalizations classified as non-Hispanic white in the police file were classified as Hispanic in the hospital records (n=21). Race/ethnicity and age group for the comparison group were determined from hospitalization records for calculation of the numerator and from census data for the denominator.

Data Analysis

Annual police-reported IPV rates per 1000 women (point estimates and 95% confidence intervals [CI]) were calculated for Dallas female residents; CIs for age group-specific rates were calculated as Poisson exact to increase precision. Comparisons of proportions between cohorts within each age and each race/ethnicity strata also were conducted using Chi square analyses.

Annual hospitalization rates and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% CIs were calculated among the two cohorts; age-adjusted rates and rate ratios were calculated with the exception of age-specific estimates. Due to small subgroup sample sizes, it was not possible to calculate age-adjusted or race/ethnicity-specific rates for intentional and self-inflicted injury rates. IRRs were calculated with negative binomial maximum-likelihood or Poisson regression, both of which account for the scarcity of counts. If overdispersion of the dependent variable was indicated in the negative binomial model, that model was used; if no overdispersion was indicated, Poisson estimates were used. Poisson regression was also employed in cases where the negative binomial model would not converge after multiple (>100) iterations.

All analyses were conducted with Stata 9.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Police-reported intimate partner violence rates

The highest police-reported IPV rate in Dallas, Texas occurred in the 18–24 year age group, over twice that of the oldest age group (Table 1). The majority of police-reported IPV occurred among non-Hispanic black (46.2%) and Hispanic (37.7%) women; rates were two to three times higher in these groups compared to non-Hispanic white women.

Table 1.

Rates of Police-Reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) by Demographic Characteristics, Dallas, Texas, 2004

| Police Reported IPVa (N=4775) | No Police Reported IPVb (N=28050) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Rate/1000 womenc (95% CI) | |

| Age Group (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 1528 (32.0) | 6152 (21.9)*** | 24.0 (22.8, 25.3) |

| 25–34 | 1947 (40.8) | 10194 (36.3)** | 18.7 (17.9, 19.5) |

| 35–49 | 1300 (27.2) | 11704 (41.7)*** | 11.0 (10.4, 11.6) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2205 (46.2) | 8099 (28.9)** | 26.9 (25.7, 28.0)d |

| Hispanic | 1798 (37.7) | 9796 (34.9)* | 17.1 (16.3, 17.9)d |

| Non-Hispanic White | 772 (16.2) | 10155 (36.2)** | 7.9 (7.3, 8.4)d |

Note. CI=Confidence interval. CIs for age group are calculated as Poisson exact.

Women residents of Dallas with police-reported adult male-to-female IPV

10% stratified sample of 2000 U.S. Census data for Dallas City residents (excluding women reporting family violence)

Rates based on full census for each subgroup

Age-adjusted rate

p<.05 comparing police-reported IPV group to no police-reported IPV group

p<.001 comparing police-reported IPV group to no police-reported IPV group

p<.001 comparing police-reported IPV group to no police-reported IPV group

Hospitalization rates and rate ratios

The overall and age-specific hospitalization rates among women with police-reported IPV were comparable to those of the comparison group (Table 2). Rates among non-Hispanic black and white women with police-reported IPV were significantly higher, however, than those of their counterparts in the comparison group. The highest rates were among those in the younger age groups, and only those rates were significantly greater among the exposed. Conversely, the rate among Hispanic women with IPV was nearly 40% lower than that of the comparison group; the rate ratios were significant only in the two older age groups.

Table 2.

Annual Hospitalization Rates per 1000 Woman Years and Incidence Rate Ratios, by Police-Reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Status; Dallas, Texas 2004–2005

| Police Reported IPVa (N=4760) | No Police Reported IPVb (N=28050) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate | N | Rate | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Total Hospitalizations | 766 | 147.1 | 3831 | 137.9 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) |

| By age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 380 | 250.2 | 1129 | 183.5 | 1.38 (0.86, 2.20) |

| 25–34 | 254 | 130.8 | 1451 | 142.3 | 0.93 (0.62, 1.40) |

| 35–49 | 132 | 101.6 | 1251 | 106.9 | 0.88 (0.60, 1.30) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 429 | 195.0 | 1195 | 148.2 | 1.23 (1.08, 1.41) |

| By age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 208 | 294.6 | 332 | 198.2 | 1.49 (1.25, 1.77) |

| 25–34 | 138 | 160.3 | 360 | 132.1 | 1.21 (1.00, 1.48) |

| 35–49 | 83 | 130.1 | 503 | 136.0 | 0.96 (0.76, 1.21) |

| Hispanic | 232 | 124.8 | 1710 | 163.5 | 0.68 (0.54, 0.86) |

| By age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 133 | 213.5 | 638 | 228.3 | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) |

| 25–34 | 74 | 95.9 | 744 | 190.8 | 0.50 (0.40, 0.64) |

| 35–49 | 25 | 64.4 | 328 | 105.8 | 0.61 (0.41, 0.91) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 105 | 145.0 | 926 | 91.8 | 1.46 (1.19, 1.79) |

| By age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 39 | 205.3 | 159 | 94.5 | 2.17 (1.53, 3.08) |

| 25–34 | 42 | 135.9 | 347 | 97.3 | 1.40 (1.01, 1.93) |

| 35–49 | 24 | 87.9 | 420 | 85.6 | 1.03 (0.68, 1.55) |

Note. IRR=Incidence rate ratio calculated using Poisson or Negative Binomial regression, age-adjusted except age-specific rate ratios; CI=confidence interval. Age-adjusted rates except age-specific rates.

Among women residents of Dallas with police-reported adult male-to-female IPV in 2004. Fifteen women were excluded from the denominator due to race/ethnicity coding errors in the hospital file.

Among women residents of Dallas without police-reported adult family violence in 2004; 10% random sample

Hospitalization by diagnostic group

Hospitalization rates associated with substance abuse diagnoses occurred at substantially higher rates among non-Hispanic black and white women compared to Hispanic women in both cohorts, although no statistically significant differences were detected between cohorts (Table 3). Significant rate ratios for any mental disorder and mood/depressive disorders were revealed for non-Hispanic whites only, with rates more than twice as high among those exposed. Episodic mood and depressive disorder diagnoses comprised the majority of mental disorder diagnoses among the exposed and comparison groups (74% and 67%, respectively).

Table 3.

Annual Hospitalization Rates per 1000 Woman Years and Incidence Rate Ratios, by Diagnostic Category and Police-Reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Status; Dallas, Texas 2004–2005

| Police Reported IPVa (N=4760) | No Police Reported IPVb (N=28050) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Category (ICD-9-CM) | N | Rate | N | Rate | IRR (95% CI) |

| Alcohol and Drug- related Diagnoses (291-292, 303-305)c | |||||

| Total | 39 | 9.2 | 198 | 6.9 | 1.28 (0.68, 2.39) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 27 | 12.1 | 89 | 10.7 | 1.25 (0.81, 1.94) |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1.2 | 24 | 2.4 | 0.46 (0.11, 1.96) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 10 | 12.0 | 85 | 8.0 | 1.71 (0.89, 3.30) |

| Mental Disordersd (293-302, 306-316) | |||||

| Total | 65 | 14.7 | 338 | 11.8 | 1.44 (0.89, 2.32) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 29 | 12.9 | 127 | 15.1 | 1.00 (0.67, 1.51) |

| Hispanic | 13 | 7.5 | 50 | 5.3 | 1.49 (0.81, 2.76) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23 | 30.0 | 161 | 15.2 | 2.02 (1.30, 3.13) |

| Episodic Mood and Depressive Disorderse (296 and 311) | |||||

| Total | 48 | 10.6 | 227 | 7.9 | 1.59 (0.98, 2.58) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20 | 9.0 | 73 | 8.7 | 1.16 (0.70, 1.91) |

| Hispanic | 10 | 5.8 | 35 | 3.8 | 1.66 (0.82, 3.36) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 18 | 23.3 | 119 | 11.1 | 2.18 (1.33, 3.59) |

Note. IRR=Incidence rate ratio calculated using Poisson or Negative Binomial regression, age-adjusted; CI=confidence interval; ICD-9-CM=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Age adjusted rates except age-specific rates.

Among women residents of Dallas with police-reported adult male-to-female IPV in 2004. Fifteen women were excluded from the denominator due to race/ethnicity coding errors in the hospital file.

Among women residents of Dallas without police-reported adult family violence in 2004;10% random sample

Excludes 305.1—Tobacco use disorder/dependence

Mental Disorders excluding alcohol or drug-related disorders

Subgroup of Mental Disorders

Injury-related Diagnoses

The rate associated with any injury diagnosis was 2.5 times higher among exposed non-Hispanic black women and three times higher among exposed non-Hispanic white women compared to their counterparts in the comparison group (Table 4). The rate of an intentional injury diagnosis was significantly higher among the exposed cohort. Although the data could not support race/ethnic-specific rates, 11 (69%) of the 16 hospitalizations associated with an intentional injury among the exposed occurred among non-Hispanic black women; four hospitalizations (25%) occurred among exposed Hispanic women and one (6%) among exposed non-Hispanic white women. The distribution among racial/ethnic groups in the comparison group was 56%, 11%, and 33%, respectively.

Table 4.

Annual Injury-Related Hospitalization Rates per 1000 Woman Years and Incidence Rate Ratios, by Police-Reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Status; Dallas, Texas 2004–2005

| Police Reported IPVa (N=4760) | No Police Reported IPVb (N=28050) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Category (E code and/or ICD-9-CM) | N | Rate | N | Rate | IRR (95% CI) |

| Any Injuryc | |||||

| Total | 46 | 10.2 | 114 | 4.0 | 2.48 (1.75, 3.50) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 25 | 11.2 | 40 | 4.8 | 2.46 (1.48, 4.10) |

| Hispanic | 10 | 5.4 | 27 | 2.7 | 1.98 (0.95, 4.10) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 11 | 13.4 | 47 | 4.6 | 3.20 (1.65, 6.19) |

| Intentional Injuryd (E960-E969; 995.80-995.85) | |||||

| Total | 16 | 3.4e | 9 | 0.3e | 10.44 (3.55, 30.69)f |

| Self-Inflicted Injuryg (E950-E959) | |||||

| Total | 10 | 2.1e | 12 | 0.4e | 4.91 (2.12, 11.37)f |

Note. IRR=Incidence rate ratio calculated using Poisson or Negative Binomial regression, age-adjusted except where noted CI=confidence interval; ICD-9-CM=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Age-adjusted rates except where noted.

Among women residents of Dallas with police-reported adult male-to-female IPV in 2004. Fifteen women were excluded from the denominator due to race/ethnicity coding errors in the hospital file.

Among women residents of Dallas without police-reported adult family violence in 2004;10% random sample

Includes External Causes of Injury and Poisoning Codes E800-848, E850-869, E880-904, E910-928, E950-995 and ICD-9-CM codes 800-904 and 910-995 (excluding certain adverse effects 995.0-995.4, 995.86, 995.89, 995.90-995.94)

Subgroup of Any Injury; includes homicide and injury purposely inflicted by other persons and adult maltreatment/abuse/neglect

Crude rate

Crude IRR

Subgroup of Any Injury; includes injuries in suicide and attempted suicide and self-inflicted injuries specified as intentional

The rate of self-inflicted injury was five times greater among exposed women. Again, the majority (60%) of hospitalizations among the exposed associated with a self-inflicted injury diagnosis occurred among non-Hispanic black women. The few remaining cases were distributed evenly among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. In the comparison group, 8%, 33% and 58% occurred among non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites, respectively.

Seven deaths, two in the exposed cohort and five in the comparison group, were recorded in the hospital discharge records (data not shown). None of the deaths were associated with an intentional or self-inflicted injury.

Discussion

These findings revealed significant racial and ethnic disparities in police-reported IPV and in the relationship between police-reported IPV and hospitalization. With regard to police-reported IPV, the National Crime Victimization Survey (Bachman & Coker, 1995; Catalano, 2007) and a population-based urban study among women during pregnancy (Lipsky et al., 2005) found that black and Hispanic women were more likely than white women to report IPV to the police. The increased rate of police-reported IPV among black women in particular is consistent with findings from other studies suggesting that black women experience more severe or fatal IPV overall (Cunradi et al., 2002; Paulozzi, Saltzman, Thompson, & Holmgreen, 2001), since police-reported IPV tends to be more severe (Bachman & Coker, 1995; McFarlane et al., 1997; U.S. Department of Justice, 1995). Disparities in reporting IPV to police also may be explained by other socioeconomic factors (Breiding et al., 2008; Field & Caetano, 2005; Pearlman, Zierler, Gjelsvik, & Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2003), which the current study was not able to take into account. On the other hand, racial and ethnic disparities have varied in general population surveys, with rates among black and Hispanic women higher than among white women in some surveys (Catalano, 2007) but not others (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). It is possible, then, that police-reported IPV may overrepresent the true prevalence of IPV among black and Hispanic women.

Our findings are unique with regard to race/ethnic-specific rates of hospitalization. Although we hypothesized that both black and Hispanic victims would utilize inpatient services at greater rates than their counterparts in the comparison group, this held true only for black women. In addition, non-Hispanic white victims also had higher rates of utilization compared to those in their comparison group. The lower rate among Hispanic women could be explained by social, cultural, and economic factors not accounted for in the current study (Bauer, 2000; Bent-Goodley, 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001, 2003; Lipsky, Caetano, Field, & Larkin, 2006; Vega & Alegría, 2001; West, Kantor, & Jasinski, 1998). Low acculturation, for example, contributes to a decrease in use in both health and social services among Hispanic victims (Lipsky et al., 2006; West et al., 1998). Several barriers to health care for abused Latina immigrant women have also been suggested, including social isolation, language barriers, discrimination, fear of deportation, dedication to family, shame, and cultural stigma of divorce (Bauer, 2000).

Another major finding revealed in the current study is that only non-Hispanic white women victims had hospitalization rates associated with mental disorder or substance abuse diagnoses that were significantly greater than the comparison group. These findings reflect the complexity of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and healthcare utilization (Borowsky et al., 2000; Das, Olfson, McCurtis, & Weissman, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Kessler et al., 2003; Van Voorhees, Walters, Prochaska, & Quinn, 2007; Vega et al., 2007; Wells, Klap, Koike, & Sherbourne, 2001). Mental health disorders may be less likely to occur or be diagnosed among blacks and Hispanics, but blacks and Hispanics also tend to report greater unmet need for mental health and substance abuse treatment compared to non-Hispanic whites (Blanco et al., 2007; Borowsky et al., 2000; Das et al., 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Hasin et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2003; Van Voorhees et al., 2007; Vega et al., 2007). Lipsky and Caetano (Lipsky & Caetano, 2007) however, found that Hispanic and non-Hispanic white, but not black, female IPV victims were more likely than their nonvictim counterparts in the general population to report unmet need for mental health treatment.

Finally, this study revealed increased rates of diagnoses related to injury among IPV victims, especially among non-Hispanic black and white women. Unfortunately, we were unable to assess rates of IPV-related injuries due to the few cases of intentional injury with perpetrator E codes. Few other studies have considered injury-related healthcare utilization and IPV outside of emergency department studies, particularly with regard to racial and ethnic disparities. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with other studies linking hospital and criminal justice data (Kernic et al., 2000; Lipsky et al., 2004). For example, Kernic et al. (Kernic et al., 2000) found higher rates of injury-related diagnoses among abused compared to nonabused women, although the relative risks were relatively comparable to the current findings. Our results are also congruent with those of Cokkinides et al. (Cokkinides, Coker, Sanderson, Addy, & Bethea, 1999) who reported a higher prevalence of trauma-related hospitalizations among pregnant women with a past year history of physical violence.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study include its diverse population base and its unique attempt to focus on racial and ethnic disparities in estimating the impact of police-reported IPV victimization on the health of women and the healthcare delivery system. Several limitations also should be noted. First, police data in general are limited by the willingness of police officers to respond to family violence calls and to accurately report those calls as family violence. Although underreporting by police is possible, the Family Violence Unit of the Dallas Police Department actively collaborates with family violence community organizations and programs, which may increase the responsiveness of police officers in family violence incidents. It is important to note that the data reflect reporting only, not arrests or convictions. Further, only Dallas Police Department data were used to identify police-reported IPV. Although the study was limited to Dallas City residents, women in the comparison group could have experienced police-reported violence while residing in other cities during the one-year study period and thus would have been misclassified as unexposed. This could have biased the estimate of the association between IPV and hospitalization downward if those individuals were hospitalized while also residing in Dallas during the study period. In addition, the use of police-reported IPV as the exposure of interest likely resulted in misclassification of the comparison group. There were certainly some women in the comparison group who had been victims of IPV but had not reported it to the police. This also would have biased the results toward the null. The study’s generalizability, then, is limited to those who report IPV to the police. Second, all police-reported family violence cases were included in the data linkage procedures for the parent study. The numerator for the comparison group — those hospitalizations that did not link to police records — would have excluded not only IPV confirmed cases but also other family violence cases. Thus, all family violence cases were excluded from the denominator of the comparison group. Therefore, the rates of hospitalization among the comparison group may have been underestimated, effectively overestimating the rate ratios. Findings from an analysis conducted on the total sample (unpublished data) followed similar patterns to the current study, however.

Third, hospitalizations associated with a substance abuse diagnosis may have been underestimated among the exposed cohort in this study since a portion of hospital discharge records with substance abuse diagnoses were blinded and would not have linked to police records. It is not possible to know the distribution of those cases by cohort, although the blinding would likely have resulted in nondifferential misclassification. A portion of the exposed cohort, potentially at greater risk of substance abuse, may have been more likely to have blinded hospital records, driving the rate ratio toward the null.

Finally, it was not possible to estimate IPV-related injury in this sample due to the few E codes with perpetrator data. In addition, only one E code was available per record. As Weiss et al. (Weiss, Ismailov, Lawrence, & Miller, 2004) have demonstrated, poor perpetrator coding in hospital discharge data limit our ability to assess serious IPV-related injury. Perpetrator coding also appears to be biased, with non-white women less likely to have a perpetrator code than white women, although we could not accurately assess this in the current study.

Conclusions

The findings from this study indicate that women experiencing police reported IPV, especially young non-Hispanic black and white women, are utilizing hospital services at higher rates overall as well as for injury and violence-related problems. This suggests that screening hospitalized women for IPV could assist in identifying those women at risk for further violence and other mental and physical health problems. Although the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence of the efficacy of IPV screening and intervention to recommend for or against routine IPV screening (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2004), many professional societies continue to recommend screening or assessing patients for IPV (American College of Emergency Physicians, 2008; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008; American Medical Association, 2005; Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 1992). Screening for IPV, if done sensitively, will demonstrate at a minimum that the healthcare provider cares; it is a window of opportunity to provide resources and referrals that may never have otherwise occurred (Lachs, 2004).

These findings also illustrate the need to focus more intensive primary as well as secondary prevention efforts on black and Hispanic communities, with police as well as community and public health organizations working together to provide education and resources. That victims appear to have more mental health and injury-related problems overall further substantiates the need for prevention, not only of IPV, but also those factors associated with partner violence. Finally, more research is needed to explore why Hispanic victims are less likely to use hospital services than Hispanic women in the general population. Future research should focus on ethnic-specific barriers and how those issues might be effectively addressed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant Number K01AA015187 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the University of Washington, Seattle. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health. We would also like to express our great appreciation to the City of Dallas Police Department for providing the police data and to the Dallas-Fort Worth Hospital Council for providing the hospital data and conducting the data linkage. Finally, a special thank you to Antoinette Krupski, PhD for her helpful comments on previous drafts and to Maria Dzikuli and Mary Laura Johnson for their assistance with data preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sherry Lipsky, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Center for Healthcare Improvement for Addictions, Mental Illness and Medically Vulnerable Populations (CHAMMP), University of Washington at Harborview Medical Center, Box 359911, 325 Ninth Ave, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, Phone: 206-744-1763 Fax: 206-744-3236 Email: lipsky@u.washington.edu.

Raul Caetano, Regional Dean and Professor, Division of Epidemiology, University of Texas School of Public Health at Houston, Dallas Regional Campus, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., V8.112, Dallas, Texas 75390-9128, Phone: (214) 648-1080 FAX: (214) 648-1081, Email: Raul.Caetano@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Peter Roy-Byrne, Chief of Psychiatry, Harborview Medical Center, Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Director, CHAMMP, University of Washington at Harborview Medical Center, 325 9th Avenue, Box 359911, Seattle, WA 98104, Phone: (206) 897-4201, Fax: 206-744-3236, Email: roybyrne@u.washington.edu.

References

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy Compendium. 2008. American College of Emergency Physicians; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening Tools-Domestic Violence. 2008 Retrieved August 31, 2008, from http://www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=17&bulletin=585.

- American Medical Association. Report 7 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A-05) 2005 Retrieved August 31, 2008, from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/15248.html.

- Bachman R, Coker AL. Police involvement in domestic violence: the interactive effects of victim injury, offender's history of violence, and race. Violence and Victims. 1995;10(2):91–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer HM, Rodriguez MA, Quiroga SS, Flores-Ortiz YG. Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2000;11:33–44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2007;8:90–104. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Patel SR, Liu L, Jiang H, Lewis-Fernandez R, Schmidt AB, et al. National trends in ethnic disparities in mental health care. Medical Care. 2007;45:1012–1019. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2007. (No. NCJ-210675) [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Reeder CE, Fadden MK, Smith PH. Physical partner violence and medicaid utilization and expenditures. Public Health Reports. 2004;119:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: maternal complications and birth outcomes. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;93:661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems, drug use, and male intimate partner violence severity among US couples. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AK, Olfson M, McCurtis HL, Weissman MM. Depression in African Americans: breaking barriers to detection and treatment. Journal of Family Practice. 2006;55:30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R. Intimate partner violence in the U.S. general population: progress and future directions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:463–469. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Basu J. The rate and cost of hospital readmissions for preventable conditions. Medical Care Research and Review. 2004;61:225–240. doi: 10.1177/1077558704263799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin DJ, Hoffman C. Racial and ethnic differences in preventable hospitalizations across 10 states. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;5(Suppl 1):85–107. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld L, Rand M, Craven D, Klaus P, Perkins C, Ringel C, et al. Violence by intimates. Analysis of Data on Crimes by Current or Former Spouses, Boyfriends, and Girlfriends. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 1-Standards. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 1992. Accreditation manual for hospitals. [Google Scholar]

- Kernic M, Wolf M, Holt V. Rates and relative risk of hospital admission among women in violent intimate partner relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1416–1420. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS. Screening for family violence: what's an evidence-based doctor to do? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:399–400. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Caetano R. Impact of intimate partner violence on unmet need for mental health care: results from the NSDUH. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:822–829. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Caetano R, Field CA, Larkin GL. The role of intimate partner violence, race, and ethnicity in help-seeking behaviors. Ethnicity and Health. 2006;11:81–100. doi: 10.1080/13557850500391410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Critchlow CW. Police-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the risk of antenatal hospitalization. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2004;8:55–63. doi: 10.1023/b:maci.0000025727.68281.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Critchlow CW. Police-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy: who is at risk? Violence and Victims. 2005;20:69–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MatchWare Technologies Inc. Automatch generalized record linkage system. Kennebunk, ME: MatchWare Technologies Inc.; [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Soeken K, Reel S, Parker B, Silva C. Resource use by abused women following an intervention program: associated severity of abuse and reports of abuse ending. Public Health Nursing. 1997;14:244–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Saltzman LE, Thompson MP, Holmgreen P. Surveillance for homicide among intimate partners--United States, 1981–1998. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summaries. 2001;50:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DN, Zierler S, Gjelsvik A, Verhoek-Oftedahl W. Neighborhood environment, racial position, and risk of police-reported domestic violence: a contextual analysis. Public Health Reports. 2003;118:44–58. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R, Gazmararian J, Andersen CK. Partner violence: Implications for health and community settings. Women’s Health Issues. 2001;11:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta S, Falik M. Prevalence of violence and its implications for women's health. Women’s Health Issues. 2001;11:244–258. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for family and intimate partner violence: recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:382–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich YC, Cain KC, Sugg NK, Rivara FP, Rubanowice DM, Thompson RS. Medical care utilization patterns in women with diagnosed domestic violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity-A supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Healthcare Disparities Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Violence against women: estimates from the redesigned survey. U.S. Department of Justice; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Walters AE, Prochaska M, Quinn MT. Reducing health disparities in depressive disorders outcomes between non-Hispanic Whites and ethnic minorities: a call for pragmatic strategies over the life course. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):157S–194S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Alegría M. Latino Mental Health and Treatment in the United States. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 179–208. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, Alvidrez J, Bernal G, Escamilla M, et al. Research issues for improving treatment of U.S. Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:385–394. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, Brownson RC. Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:156–164. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HB, Ismailov RM, Lawrence BA, Miller TR. Incomplete and biased perpetrator coding among hospitalized assaults for women in the United States. Injury Prevention. 2004;10:119–121. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.004382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CM, Kantor GK, Jasinski JL. Sociodemographic predictors and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior by Latina and Anglo American battered women. Violence and Victims. 1998;13:361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S, Shen YC. Characteristics of occasional and frequent emergency department users: do insurance coverage and access to care matter? Medical Care. 2004;42:176–182. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108747.51198.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]