Abstract

Purpose

Our aim was to assess the content validity of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) social health item banks by comparing a prespecified conceptual model with concepts that focus-group participants identified as important social-health-related outcomes. These data will inform the process of improving health-related quality-of-life measures.

Methods

Twenty-five patients with a range of social limitations due to chronic health conditions were recruited at two sites; four focus groups were conducted. Raters independently classified participants' statements using a hierarchical, nested schema that included health-related outcomes, role performance, role satisfaction, family/friends, work, and leisure.

Results

Key themes that emerged were fulfilling both family and work responsibilities and the distinction between activities done out of responsibility versus enjoyment. Although focus-group participants identified volunteerism and pet ownership as important social-health-related concepts, these were not in our original conceptual model. The concept of satisfaction was often found to overlap with the concept of performance.

Conclusion

Our conceptual model appeared mostly comprehensive but is being further refined to more appropriately (a) distinguish between responsibilities versus discretionary activities, and (b) situate the outcome of satisfaction as it relates to impairment in social and other domains of health.

Background

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) encompass aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) including symptoms, limitations, well-being, and patient preferences regarding health states, treatments, and costs. PROs measure patients' health status using information directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's responses by a physician or anyone else [1]. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) project was undertaken to help advance PRO measurement for clinical, social science, and epidemiological research, as well as for clinical practice. The overall aim of PROMIS is to develop reliable and valid approaches to measuring PROs using item response theory and computer-adaptive testing. A multidisciplinary panel of researchers from institutions nationwide collaborated to construct a framework for the measurement of general health concepts. As a starting point, PROMIS adapted the original structure of the World Health Organization's (WHO) physical, mental and social framework. The WHO framework is broad and inclusive, and flexible enough to allow integration of other theoretical perspectives [2-5]. More recently, the WHO (2001) has replaced its three-domain framework of health with an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [5]. Multiple domains were identified for each of the three original WHO health concepts (physical, mental and social); for more in-depth discussion of this process, see Cella et al. [2]. Five domains were ultimately selected for the initial work on PROMIS: pain, fatigue, emotional distress, physical functioning, and social role participation. These five constructs were chosen because each met the following criteria: 1) the construct cuts across many chronic health conditions; 2) the construct is frequently used as an outcome variable in clinical trials; 3) the latent trait level could be modeled on a continuum; and 4) candidate items could be measured on an ordinal scale and eventually tested with classic and modern psychometric methods [2, 3, 6]. The selected domains represent the initial foray of PROMIS toward developing a measurement system and are not intended to cover all areas of the ICF Framework.

This study focuses on the social domain, which is defined in PROMIS as perceived well-being regarding social activities and relationships, including the ability to relate to individuals, groups, communities and society as a whole. Primary components of social health and functioning measured in current research include social role participation, social network quality, interpersonal communication, and social support [7-12]. We were most concerned for PROMIS with social role participation and satisfaction since these concepts most closely align with outcomes rather than processes. The concept of social role participation is distinct from the others mentioned (social network quality, interpersonal communication, and social support), and reflects one's involvement in, and satisfaction with, usual social roles including those within marriage/partnership, parenting, work, and leisure activities [8, 13]. Social role participation has also been referred to as “social adjustment”[13]. In contrast, measures of social support generally seek information about a person's perception of the availability or adequacy of resources provided by other persons [14]. Social support was excluded from the social health domain because to date it has been generally deemed a “process,” not “outcome” variable.

For the social health domain, a multi-institutional panel of PRO experts convened regularly with two main initial objectives: to define the social health domain through a conceptual model (also termed “domain map”), and to construct banks of items to measure the most salient aspects of social health-related outcomes [3]. These two tasks were carried out concurrently and interdependently, and are described below. These objectives were in the larger goal of using both qualitative and quantitative data to inform the development of improved measures of HRQOL. The present study describes the use of qualitative focus group data.

Domain definition

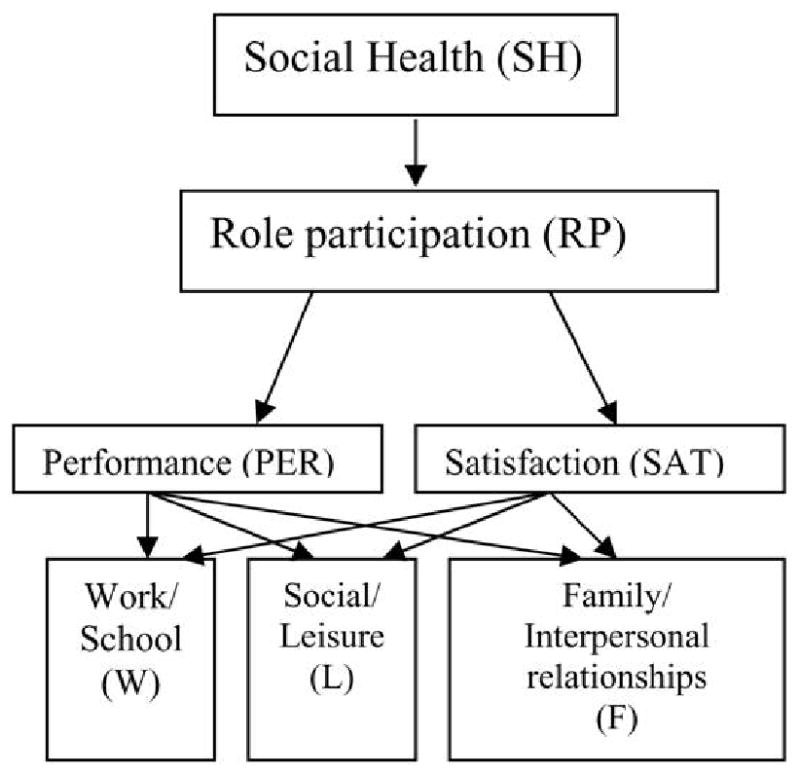

The strategy for defining the domain was to review past literature, draw on the expertise of the panel members and the larger PROMIS network, and come to consensus on the domain's subcategories. To reach consensus, we used the Delphi panel technique. This technique was originally designed in the 1950s to help forecast future events; it is now used in a number of fields to obtain expert input on planning activities from individuals who are widely dispersed geographically [15]. The process began with an open-ended query given to a panel of experts (“what are the outcome-related components of social health and well-being?”), who submitted itemized feedback in response. In subsequent iterations, the panel members rated the relative importance of the feedback received, and made changes to phrasing and content. Consensus was reached after three such iterations. Two subcategories of social role participation were proposed as a result of this consensus process - performance of and satisfaction with social roles in three contexts: family/friends, work/school, and leisure activities (Figure 1) [16].

Figure 1.

Social Health domain map

Item bank development

The strategy for item bank development was to identify, evaluate, and modify items from existing surveys, and lastly, to develop new items where necessary. To identify existing items, we conducted comprehensive literature searches for social health questionnaires resulting in 1781 social health items. Construction of the item banks and domain map, as well as the processes used to narrow the item pool are described in detail elsewhere [3]. To summarize, items were re-written to improve clarity, reduce the number of response options, and utilize a 7-day time frame. The final item pool contained 112 items, the majority of which resulted from new item development. When necessary, intellectual property agreements were obtained from instrument authors to provide PROMIS permission for use.

Content validity assessment

We were concerned that aspects of the domain that are important to patients may be over- or underemphasized in the academic literature. To address this problem, we conducted focus groups to elicit feedback directly from participants who had reported social health limitations. We aimed to obtain input that would help fill in potential conceptual gaps in the domain map, and inform writing of new items if necessary. Our goal was to qualitatively assess the content validity of the social health item banks by evaluating the fit between those concepts that make up the social health domain map and those concepts that focus group participants identified as important aspects of social health-related outcomes. A key assumption of this approach was that the focus group discussions would provide qualitative information that would either support or refute the concepts of the social health domain as it was defined.

We evaluated the extent to which the information gained from the focus groups confirmed, contradicted, or added to the social health domain map (Figure 1), via the following research questions:

- To what extent did the domain map describe and sample the variety of social health-related outcomes, i.e., was our domain map comprehensive in describing social health-related outcomes that participants identified as important?

- Did the subcategorizations in our domain map for social-health outcomes (Performance, Satisfaction; Family/Friends, Work/School, and Leisure) appropriately describe social health-related outcomes that participants identified as important?

Both in developing the item banks and in defining the domain, we aimed to capture aspects of social health and well-being that would be most likely associated with changes in health status.

Methods

We analyzed data from 25 participants who took part in four focus groups at two sites. Raters worked independently to classify participants' statements based on a schema derived from the domain map. The resultant coded transcripts were assessed to determine the comprehensiveness and appropriateness of the domain map in covering important social health PROs.

Because a goal of PROMIS is to design instruments to measure domains that cross many chronic health conditions, we did not believe it was feasible to conduct condition-specific focus groups. Instead, we adopted the strategy of selecting a sample of patients who stated they had experienced a range of social limitations [3, 17]. Recommendations for both the number of focus groups and sample size vary. The number of recommended sessions depends on the complexity of the study design and the target sample's level of distinctiveness [18-21]. Stewart et al. (2007) observed that rarely are more than 3-4 focus groups conducted in the social sciences. We felt that two groups at each site would limit bias that might be seen in a single group or site and allow us to examine themes common across groups. We chose a sample size of at least five participants per group because recommendations in the literature range from 4-8 participants [22], 4-12 participants [19], 6-12 participants [21, 23], or 8-12 participants per group [18]. Smaller groups allowed facilitators to do more in-depth follow-up queries about social limitations in order to examine the conceptual coverage for the PROMIS social health domain map. Finally, different facilitators conducted the groups in order to minimize the potential for investigator bias.

Sampling: recruitment and inclusion criteria

At both sites, we recruited outpatients who reported impairment in social functioning. A range of health conditions was represented (e.g., arthritis, heart disease, diabetes, and depression), and participants were heterogeneous with regard to mental versus physical impairment. Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics at two of the PROMIS study sites: the University of North Carolina (UNC) General Internal Medicine Clinics and the University of Pittsburgh adult outpatient psychiatric clinics at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC). A multimodal recruitment strategy (including print media, flyers, mailed letters, and health care provider referrals) was employed in order to get as many patients together as possible, and to aim for demographic diversity. A non-response rate could be calculated only for the portion of the sample that was recruited by mail (n=115). Of those, 96 (83%) did not respond to the letters. The majority of non-respondents were Caucasian and female, as were the majority of the respondents. Respondents and non-respondents did not differ significantly with respect to ethnicity, gender or education. To be included in the study, all participants had to be at least 18 years old; had seen a physician for a chronic or mental health condition within the past 5 years; had to speak and read English; and had responded affirmatively to recruitment materials asking for participants with limitations in their activities due to health problems. No participants who met the eligibility criteria were excluded.

Procedures

All participants provided written informed consent in person after hearing the facilitator describe the study and consent processes. Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the study (UNC IRB#05-2751; WPIC IRB#0511028), and all procedures were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Appendix A is a sample facilitator's script that was based on the domain map. Participants were not shown individual items from the item banks; rather, they were led through a series of open-ended discussion questions relating to social activities, well-being, and limitations. Each session lasted a maximum of 1.5 hours, was digitally recorded, and transcribed.

Content analysis

Three raters, each of whom was previously unfamiliar with the domain map, were trained to use qualitative analysis software (Atlas.ti 5.2) [24] to independently code statements within the social health focus group transcripts. Coding consisted of selecting and classifying statements that related to the following hierarchical, nested classification schema (see Table 1 for definitions and examples):

Table 1. Domain map term definitions.

| Item | Definition | Examples | Frequency: Rater 1 | Frequency:Rater 2 | Frequency: Rater 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related outcomea | A change in health status or well-being that results from developmental processes, disease and/or clinical intervention. Note: most statements were considered health-related, given the context and inclusion criteria for these focus groups | Doing things one used to do or wishes one could do Symptoms, including pain, fatigue, or sleep problems |

587 | 371 | 483 |

| Role Participation Performance | Involvement in socially expected or chosen behavior patterns in an individual's life situation | Ability to attend a special event Ability to make meals/care for others |

256 | 227 | 230 |

| Role Participation Satisfaction | The degree to which an individual judges his/her ability to take part in social roles to be adequate, to meet or exceed expectations, or to be a source of contentment for themselves and others | Happiness with how one is keeping up with family responsibilities Whether one is pleased with one's leisure activities |

37 | 55 | 72 |

| Family and Friends | Having an association or connection with others | Comforting others and giving emotional support Interacting socially with family, friends, or acquaintances (eating out, going to a party) Meeting new people Initiating interaction or maintaining relationships with spouse/partner, children, family members, and friends Maintaining connections with other people. |

103 | 90 | 216 |

| Workb | Activities related to one's job/career and involving activities necessary or important to maintaining one's lifestyle. This may include employment for pay or tasks undertaken not for pay that play a significant role in maintaining material or psychological well-being. | Going to one's place of work and performing tasks associated with one's job Performing or successfully delegating household tasks |

104 | 90 | 79 |

| Leisure | Discretionary activities free from work or duties that are pursued for their intrinsic value. | Taking part in quiet leisure activities (reading a book, watching TV) Entertaining others in your home Taking an out-of-town vacation Taking part in active leisure activities (playing sports, going to a movie, visiting a museum) |

118 | 115 | 51 |

| Other | Used for statements that met criteria for role participation performance and/or role participation satisfaction, but were not covered by family & friends, work, or leisure. | See Table 6 | 14 | 16 | 13 |

All of the examples in this table are health-related outcomes.

Work/school was included as a context for social health because fulfillment of one's role as an employee is not based solely on productivity, but also on the nature of social interactions with coworkers, clients, and bosses, and these social interactions are an omnipresent element of all work/school undertakings. They also represent an area where illness may impair one's ability to participate in the social roles that earning money or attending school demand

- Health-related outcome (HRO),

- Social role participation performance (RPP) and satisfaction (RPS), and

- Contexts of family and friends (F), work (W), leisure (L), or Other (O).

Each rater designated blocks of text independently, with the instruction to include more, rather than less, context for each given concept (i.e., raters were advised against selecting just one or two words at a time). Raters were instructed to assign multiple codes in cases where more than one concept was mentioned. The coding process was done iteratively in three passes, corresponding to the three schema levels above. In the first pass, raters read all text and assigned the “HRO” code to applicable statements. In the second pass, raters examined HRO statements, and assigned additional codes of “RPP” (role participation performance), “RPS” (role participation satisfaction), or “both RPP and RPS”. In the final pass, raters further refined the coding into one or more of the context areas (family/friends, work, leisure, or other).

If a statement was too general to be categorized beyond the HRO level, it was left as is. For example, the statement “I'm just not able to do things I used to do,” in the absence of further context or specificity, would be coded as “HRO.” However, if the participant gave multiple contexts (e.g., “…to do things I used to do, like playing tennis or spending time with my grandchildren”), this would also have been coded as both “leisure” and “family”. Statements in the last pass that were specific but did not fit into the categories of family/friends, work, or leisure were coded as “Other.” To improve consistency and address questions and ambiguities in the coding process, the raters reconvened for discussion after the completion of one transcript out of the four. The coding process was geared toward the content analysis and the assessment of the domain map. Thus, it involved non-mutual exclusivity of codes; it also lacked a finite set of instances for potential agreement between raters. These characteristics ruled out assessment of inter-rater agreement using tools that rely on these discrete counts, such as the kappa measure of agreement [25-27].

Interpretation

In assessing fit between the domain map and focus group content, the first step was to identify recurrent themes among those statements coded as social health-related outcomes. The next step was to identify potential qualitative indicators of lack of fit. Prior to conducting the analysis, we envisaged two types of such potential indicators. Recurrent relevant themes among statements that were not assigned any code, or coded as “Other” would indicate that our domain map was not comprehensive. In addition, consistent difficulty by the raters in assigning the codes to particular content would indicate that our domain map was not appropriately specified.

Findings

Participant characteristics

A total of four focus groups were conducted, with 10 participants at the UNC site and 15 at the WPIC site, totaling 25 participants. Table 2 shows descriptive characteristics of the focus group participants, who were heterogeneous with regard to gender, mental/physical condition, and severity of impairment. Multiple chronic comorbidities were common.

Table 2. PROMIS Social Health Domain Focus Groups: Participant Demographics.

| Characteristic | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Gender – Female | 15 (60) |

| Age | |

| Median | 53 |

| Range | 22-83 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 15 (60) |

| African American | 8 (32) |

| Other | 2 (8) |

| Married | 10 (40) |

| Education | |

| Less than High School | 1 (4) |

| High School | 5 (20) |

| Post High School | 12 (48) |

| College Degree | 3 (12) |

| Advanced Degree | 4 (16) |

| Occupation | |

| Retired | 7 (28) |

| Employed – full time | 8 (32) |

| Employed – part time | 2 (8) |

| Disability or Leave of Absence | 5 (20) |

| Unemployed | 1 (4) |

| Other/Missing | 2 (8) |

| Literacy levelb | |

| Below High School | 5 (20) |

| High School | 3 (12) |

| Post High School | 17 (68) |

| Diagnosis/Conditionc | |

| Arthritis | 16 (64) |

| Heart Disease | 6 (24) |

| Diabetes | 5 (20) |

| Chronic Pain | 13 (52) |

| Cancer | 1 (4) |

| Kidney Disease | 0 (0) |

| Lung Disease | 0 (0) |

| Chronic Fatigue | 2 (8) |

| Fibromyalgia | 2 (8) |

| Mental Health | 16 (64) |

| Other | 24 (96) |

Note: The above includes data from four groups in total, with two at UNC-Chapel Hill and two at University of Pittsburgh. There were 25 total participants.

Numbers listed as value (percentage) unless otherwise noted.

Literacy measured by the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT)

Counts total to more than 100% due to multiple diagnoses per participant.

Themes in coded statements

Tables 3 and 4 show examples of quotes that were coded as role participation performance and/or role participation satisfaction. Participants expressed varying degrees of engagement in social roles involving family/friends, work, and leisure. A theme that emerged in statements about performance was the distinction between doing things out of responsibility (e.g., childcare) versus enjoyment (e.g., reading poetry); see Table 3. The balance between family, work, and leisure was also often cited as important to participants. In statements about satisfaction (Table 4), participants often spoke about frustration or other emotions associated with their ability to get along with others, carry out responsibilities, or do things for enjoyment.

Table 3. Components of Social Health Role PERFORMANCE.

| Topic Area | Participant Quote |

|---|---|

| Family/Friends | “I'm the oldest in my family. A lot of times they look up to me and I can't do the things that I used to do and they don't realize how I feel” “I'm home schooling the oldest. So, part of my day is spent preparing lessons for my son and getting everybody off to school, you know, childcare stuff.” “I haven't been to weddings, large groups” [about daughter] “I was just in a lot of physical pain yesterday and she just got on my nerves.” “I just don't answer the phone. So my friends and my family that are close to me know, just give me my space. Don't bother me.” [Facilitator, asking about children] “So you said ‘expectations’? You need to be there.” [Participant response] “Right. Getting up for them and then knowing that I have to get to work.” |

| Work/School | “…my daughter's in preschool so um, it's a mish-mash if you just want to look at it all together. Um, some mornings I get up and I'm with her all day and then… I go to work in the evening.” “My responsibilities are managing the house.” “I get up at 5:30, you know… shower and everything. Get ready for work. And my husband and I… he drops me off at my vanpool and I have an hour and 15 minute commute and I go to work all day. 4:30 I get back on the van and an hour and 15 minutes commute back home.” |

| Leisure | “So my downtime is when I can go and I read poetry and hang out with my buddies.” “I'm actually like going out and doing things, like things I've never done like fishing, and shooting archery.” |

| COMMENTS | Statements reflected involvement in and ability to carry out social roles. Most of the statements made fell into the subcategories (Family/Friends, Work, and Leisure) that were part of the domain map. Distinction between activities undertaken out of obligation versus enjoyment was important to participants. |

Table 4. Components of Social Health Role SATISFACTION.

| Topic Area | Participant Quote |

|---|---|

| Family/Friends | [about home-schooling son] “I would say for the last week, I really try to be very patient with him and I think I do a pretty good job.” [about life with spouse] “I get very aggravated if I can't do what I want to do.” “I think I only talk to 2 of my outside family members now. One of my father's brothers and one of my cousins. That is about it, which is shitty.” “It's hard. And I know I get up every day because… and I'm the strong one in the family so if (Name) falls apart, my husband is going to fall apart, my kid is going to fall apart, my mom is going to fall apart. So I feel like I'm holding everybody else on my shoulders.” |

| Work/School | “I wanted to go back into college and get a master's degree in medicine, but my physical health and my mental health are causing me not to be able to do this.” “I need to work on getting a job since I haven't worked in over 6 years. I hate sitting at home.” “I was angry all the time when I went to work because I hurt all the time and um, it was just the frustrating stuff.” |

| Leisure | “I'm actually like going out and doing things, like things I've never done like fishing, and shooting archery. It feels like I'm living it up for the first time.” “I love walking in Charleston but I didn't walk as much as I would have had I not been hurting so bad from the hotel bed.” “I just went on a week's vacation to Panama. Wow - it was nice. Weather was great. Got to see all the Survivor sites. That was a good time.” |

| COMMENTS | Statements often overlapped with statements about performance. Statements reflected emotional responses to the degree of fulfillment of expectations, wants, or needs in these areas. Most of the statements made fell into the subcategories (Family/Friends, Work, and Leisure) that were part of the domain map. |

Themes in uncoded text

Among the four transcripts analyzed, there were few instances of text left uncoded by the raters. Raters reported difficulties in coding and/or did not code text that was vaguely stated or inaudible, lacked precise context, expressed uncertainty, told stories about the past or about other people, contained philosophizing/observations about life, or described hypothetical and/or future scenarios that did not reflect reality in the present (see Table 5). It appeared that the uncoded text did not cover social health-related outcomes and therefore carried negligible implications for our assessment of the domain's comprehensiveness and appropriateness.

Table 5. Themes in text uncoded by any of the three raters.

| Topic area | Example participant quotes | Implication(s) for domain map fit |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Indistinguishable speech | “[muffled] …” | Unknown |

| 2. Interactions between those present | None | |

| Logistics | “I'll probably be towed by now. I don't care.” | |

| Jokes/sarcasm/facetiousness | “We should start a depression musical!” | |

| Sharing tips or information | “Dr. X down in [town], he's also a UNC doctor. He's very friendly.” | |

| Exchanging opinions | [in response to story] “I couldn't live with myself.” [in response to story] “I don't even know how you can talk about it.” [re: Dancing with the Stars] “their costumes are a little revealing.” |

|

| Support, sympathy, or encouragement | “It's not [too] late, honey.” | |

| Affirmation | “I think that's a fair summary.” | |

| 3. Description of others not present | None | |

| Factual personal information | “I have two kids.” | |

| Discussion of another person's medical or physical state | [about brother] “they removed a couple of toes” [about son] “His reproductive system doesn't work properly. He has an ostomy bag.” |

|

| 4. Philosophizing | None | |

| Non-religious | “You can't love another person until you love yourself. Who wrote that?” | |

| Religious | [about friend] “Just like the good Lord wanted us to get together.” | |

| 5. Description of self | None | |

| Factual personal information | “I am 24” | |

| Individual hobbies | “…crocheting” | |

| Medications or coping strategies | “But now I don't take nothing for no blood pressure, no pills.” | |

| Storytelling about the past | “They told me I had my workers sitting around for 3 days not doing anything because I knew how to do my drawing in geometry and the foreman wouldn't come around and inspect it until he finished. I got laid off. This was when I was young.” | |

| Speculation about the future | “…[I'm] just worried that I'll get something, like… diabetes.” | |

Themes among statements coded as “Other”

The concept of volunteerism was the only discernable theme that emerged and recurred in the statements coded as “Other.” Table 6 gives examples of such statements. The ability to do volunteer work was reported as a source of satisfaction and fulfillment; conversely, limitations in ability to engage in volunteerism were reported as a potential source of dissatisfaction. Volunteerism and work undertaken for pay may share certain aspects, such as contractual arrangement, defined tasks or outputs, expectation of a standard of quality, and time constraints. However, while in general the primary goal of work undertaken for pay is to support oneself financially, participants' statements implied that the primary goal of volunteerism was to gain a sense of well-being from the act of helping others. This well-being seemed to derive from the fulfillment of religious, spiritual, or moral beliefs about doing things for others, motivated by altruism.

Table 6. Theme in text coded as “Other”.

| Topic area | Example participant quotes | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Volunteerism | “I actually volunteer for a “meals on wheels” program at a local church and sometimes I help deliver the meals even along with, you know, preparing the meals and doing other stuff there also.” “I volunteer down at - in kindergarten and first grade, the reading program - and I do that three days a week. And it's wonderful - and to me it's the highlight of my week.” “I feel like I have an obligation to humanity that I'm not able to fulfill” “I often think this is why I do so much for others. It's because I hear a thank you or that was nice or that was great because I never get it at home.” “We give out food to these people every day. But um, that's where I get my enjoyment, it's helping people.” |

Participants' statements reflect a sense of well-being that is derived specifically from the act of helping others in their communities. |

Content-related coding difficulties

Three areas of content-related coding difficulties emerged in the coding process: overlapping concepts, hypothetical speech, and references to pets.

As mutual exclusivity among the domain subcategories was not one of our a priori goals, raters were instructed to assign more than one code where appropriate. Our examination of frequently overlapping themes informed our assessment of the domain map's appropriateness. The most common incidents of overlapping concepts occurred when participants spoke of responsibilities toward other family members, especially children, in the same way that they spoke of work responsibilities. Many participants had children, and their social well-being was often related to the degree to which they fulfilled expectations, desires, needs, and demands originating from the simultaneous requirements for both childcare and financial security. Another area of overlap was between the concepts of performance and satisfaction. The raters often simultaneously assigned both of these two codes to the same statements.

Another difficulty that the raters encountered was in coding participants' hypothetical statements or statements about the future. Such statements most likely reflected health and social concerns or worries on the part of participants. One stated: “You start thinking ‘what if I get cancer - and that's painful - how will I know I have cancer because I hurt all the time?’” All three raters labeled this statement as a health-related outcome, but none made a further designation.

There were numerous references to pets as significant members of participants' households. In the attachment literature, pets are considered secondary attachment figures; pet ownership has been found to have positive health correlates [28]. Focus group participants often expressed the sentiment that pets were a vital source of support and companionship. However, because we had chosen not to evaluate social support at this time, and because we chose to define the term “social” as having to do with other humans, our coding efforts focused mainly on those statements about taking care of pets as part of household responsibilities. It is nonetheless noteworthy that pet ownership was mentioned frequently when participants spoke of their satisfaction and well-being.

When asked whether they preferred a 30- versus 7-day timeframe for questions about social well-being, four UNC participants expressed a preference for 30 days. No WPIC participants expressed a preference and no UNC participants said they preferred a 7-day recall period. However, this feedback should be considered in light of the long-term quantitative measurement goal of PROMIS to retain accuracy. Recent FDA guidance on reliability in quantitative PRO measurement states that longer periods of recall may threaten the accuracy of PRO data [1]. Depending on the disease area and the frequency of those symptoms being assessed, shorter recall periods may be preferable to longer ones in quantitative assessment of PROs [29].

Conclusions

Social health is a complex construct in terms of conceptualization and measurement. Given also the variety of possible subdomains and their interactions with each other in a possible framework for social health, it was important to assess the adequacy of our domain map in defining social concepts of value to real people. Our aims in the present study were to assess whether our domain map and its subcategories were comprehensive and appropriate in describing social health-related outcomes.

Overall, the findings supported comprehensiveness of the domain map. However, as a result of our findings the subcategory of work was expanded to include volunteerism (see Recommendation 1, Table 7). In the future, if social support is eventually included in the domain, the concept of pets should be re-examined (Recommendation 2, Table 7).

Table 7. Recommendations for improving Social Health domain content validity.

| Recommendation | Supporting evidence from content analysis |

|---|---|

| Expand definition of “work” to include volunteerism, but retain the distinction between work undertaken for pay versus unremunerated work undertaken with the goal of altruism. | Volunteer work frequently brought up by participants (in statements coded as “Other”) as a source of fulfillment, satisfaction, and well-being. |

| If the domain is expanded to include social support in the future, we should consider how pets will be integrated into the conceptualization. | Pets were frequently mentioned by participants, but the Raters had difficulty coding such statements because social activities had been operationally defined as involving other humans. Pet ownership is known to affect health outcomes. |

| Make a distinction in the domain map between activities undertaken out of responsibility and/or obligation versus those undertaken for enjoyment. | This distinction emerged as important within the contexts of family/friends (childcare vs. social activities with friends) and work (job activities vs. volunteerism). |

| Revisit how satisfaction is integrated into the domain map. | Satisfaction did not emerge as a concept separate or distinct from performance in the content analysis (e.g., people often expressed satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their ability to perform a given activity). Statements about satisfaction frequently reflected strong emotions, and emotional distress is a separate PROMIS domain. |

In assessing appropriateness, we gained valuable information that will help us to improve the domain map. First, the distinction between activities undertaken out of obligation versus enjoyment was important to participants (Recommendation 3, Table 7). Second, our findings suggest that we should revise how the concept of satisfaction is integrated into the social health domain map (Recommendation 4, Table 7). Statements about satisfaction reflected the degree to which participants' social role expectations, desires, needs, or demands (imposed either internally or externally) were fulfilled. The theme of satisfaction was not distinct from performance, as many times statements coded as satisfaction reflected “satisfaction with [one's] ability to perform” a given activity. Pervasive overlap of these concepts in the content analysis prompted the question of how best to measure “performance” versus “satisfaction” (see Figure 1). Although the concepts were frequently mentioned together when raised in the focus group discussions, this does not necessarily imply that they cannot be distinguished conceptually. Further examination of conceptual distinctions between performance and satisfaction is warranted. In addition to coding difficulty surrounding the concept of satisfaction, strong expressions of emotion were also present in statements about satisfaction (Table 4). Because there is a separate emotional distress domain in PROMIS, further efforts should explore how the concept of satisfaction with social health overlaps with emotional distress.

Limitations

One limitation was that our findings on responsibility versus enjoyment may have been an artifact of the design of the interview guide (see Appendix), which asked participants to think specifically about things they are expected to do and things that they like to do. This question of potential circularity will be in part addressed in the quantitative analyses of the item banks underway; these analyses are expected to give us greater insight into the underlying latent traits for these measures.

Selection bias may have had an effect on our findings. First, volunteerism may have appeared as a salient theme among these participants because they had self-selected to be in the focus group. Second, the range of limitation represented by our sample excluded patients whose health problems would have prevented them from leaving their house (i.e., persons who were extremely socially disengaged). Since one overall goal of the PROMIS quantitative analysis is to reduce “floor” and “ceiling” effects of functionality and limitation, more diverse sampling procedures will be needed to cover a fuller range.

Lastly, the semi-public nature of any focus group study means that sensitive issues may be discussed less comprehensively than they would in a more private setting. Stronger personalities and “group think” threads of conversation may also have dominated the discussion and precluded some individuals from sharing as much as others.

Strengths

The main strength of the present study was that the information gained from this qualitative analysis helped us make substantive improvements in refining the domain map, making it more comprehensive and appropriate in covering social health concepts. These qualitative efforts are expected to contribute to an item bank for social health that improves upon past measures of social health: specifically, the PROMIS items are broadly applicable across different illnesses and health states, and in keeping with the definition of PROs [1], they do not impose external numeric thresholds on respondents' assessment of their own social well-being. For examples, several extant measures ask questions like “how many people do you feel you can count as close to you?”, creating a need for further interpretation of the marginal qualitative value of a response of “5” versus a “2”. In addition, the PROMIS effort has used a combination of methods - panel consensus, qualitative methods, and quantitative methods - to construct the item bank, integrating past literature, extant measures, and most importantly, the patient perspective. Thus these qualitative findings are an important step in a process that provides new and unique contributions to the existing methods and literature for assessing social health.

A wide variety of medical and psychiatric conditions was represented in the sample (e.g., arthritis, heart disease, diabetes, and depression). We were therefore able to capture a spectrum of social health limitations and themes in social health-related outcomes that would be pertinent in a variety of chronic health conditions. This fits with the overall goal of PROMIS to develop measures of HRQoL that can be used in a variety of contexts for medical and psychosocial evaluation.

Another strength of the present study was that data were collected across two different sites – one a predominantly rural area in the Southeast and the other a predominantly urban area in the Northeast – and using different facilitators; this design feature minimizes the potential for effects of investigator bias to bring about systematic bias in the findings.

Future research

Quantitative analyses of data collected in the social health domain should examine how the concepts of performance, satisfaction, responsibility, enjoyment, and limitation interact with each other to further inform our domain map. These analyses should also be able to identify areas for further potential refinements of the domain map (e.g., perhaps a distinction between relationships within versus outside the home). The decision to use focus groups in the present study was made on the basis of our need for qualitative information that would confirm, contradict, or add to the domain map. Thus, pre-coded methods such as pile sorting and concept mapping would not have allowed us to identify and assimilate new information. However, such methods may prove useful in further assessments of the revised domain, as well as in future cross-cultural applicability research [30].

Because our long-term goals are to create item banks that (a) are amenable to item response theory and computer adaptive testing for measuring constructs within social health, and (b) reflect and track with health outcomes and impairments in other areas of HRQoL, including other PROMIS domains (emotional distress, fatigue, pain, and physical functioning), further validation of the social health domain map and item bank through both qualitative and quantitative analysis efforts is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap initiative to develop a computerized system measuring patient-reported outcomes in respondents with a wide range of chronic diseases and demographic characteristics. PROMIS was funded by cooperative agreements to a Statistical Coordinating Center (Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, PI: David Cella, PhD, U01AR52177) and six Primary Research Sites (Duke University, PI: Kevin Weinfurt, PhD, U01AR52186; University of North Carolina, PI: Darren DeWalt, MD, MPH, U01AR52181; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, PhD, U01AR52155; Stanford University, PI: James Fries, MD, U01AR52158; Stony Brook University, PI: Arthur Stone, PhD, U01AR52170; and University of Washington, PI: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD, U01AR52171). NIH Science Officers on this project are William Riley, Ph.D., Susan Czajkowski, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, James Witter, MD, and Susana Serrate-Sztein, PhD. This manuscript was reviewed by the PROMIS Publications Subcommittee prior to external peer review See the web site at www.nihpromis.org for additional information on the PROMIS cooperative group.

This work was also supported by AHRQ National Research Service Award Research Training Grant T32 HS000032-17.

We gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by David Cella of Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, as well as the data coding efforts of the three raters at the UNC site: Katherine Buysse, Jessica Dilday, and Ashley Hink. Significant acknowledgements at the Pittsburgh site include Emily Huisman, Catherine Maihoefer, and Nathan Dodds.

List of Abbreviations

- F

family and friends

- HRO

health-related outcome(s)

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

- L

leisure

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PRO(s)

patient-reported outcome(s)

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- RPP

role participation performance

- RPS

role participation satisfaction

- UNC

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- W

work

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WPIC

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (University of Pittsburgh)

Appendix: Focus group discussion guide for social health focus groups

-

[Introductions]

Let's begin by going around the room and introducing ourselves to the group. First, tell us your name, then, tell us an example of something you do because you are expected to, and then follow up with an example of something you do just because you like doing it. Who would like to start?

Follow-up: Let's make these examples more specific. Thinking about your paid work or things you have done as a homemaker over the past 30 days, what are some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing.

Follow-up: Let's make these examples more specific. Thinking about your paid work or things you have done as a homemaker over the past 30 days, what are some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing. Follow-up: Thinking about the things you have done with family and friends in the past 30 days, what were some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing?

Follow-up: Thinking about the things you have done with family and friends in the past 30 days, what were some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing? Follow-up: Thinking about the things you have done for leisure and recreation in the past 30 days, what were some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing?

Follow-up: Thinking about the things you have done for leisure and recreation in the past 30 days, what were some things you were expected to do and things you just enjoyed doing? Follow-up: So far, we have discussed things we feel we should do or things we like to do that fall into the category of work, family, or leisure. What other categories of activities, if any, should be added to this list?

Follow-up: So far, we have discussed things we feel we should do or things we like to do that fall into the category of work, family, or leisure. What other categories of activities, if any, should be added to this list?

-

[Recent health impacts]

If we have health problems, it can sometimes be hard to do the things we think we should do or the things we just like to do. Thinking about your own lives over the past 30 days, what are some ways, if any, that your health problems have made it harder for you to do things you just enjoyed doing?

Follow-up: Thinking again about the past 30 days, what are some ways, if any, that your health problems made it harder for you to do things you just enjoyed doing?

Follow-up: Thinking again about the past 30 days, what are some ways, if any, that your health problems made it harder for you to do things you just enjoyed doing? Follow-up: How about with any roles not yet mentioned?

Follow-up: How about with any roles not yet mentioned?

-

[Long term health impacts]

Let's shift topics a bit. Let's talk about ways that the things you do now have changed, if at all, from the way they were before you began having to cope with your chronic health condition. As before, we will focus separately on work, family, and friends, and then leisure.

Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do at work, or in carrying out your homemaking responsibilities?

Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do at work, or in carrying out your homemaking responsibilities? Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do with your family and friends?

Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do with your family and friends? Follow-up: Has your chronic health problem affected how you get along with your family or friends? If so, how?

Follow-up: Has your chronic health problem affected how you get along with your family or friends? If so, how? Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do for leisure time or recreation?

Follow-up: How have things changed, if at all, with the things you do for leisure time or recreation?

-

[Coping]

Take a moment now to remember how life was before you started to have chronic health problems and the changes you have had to make to cope with them.

Follow-up: Which of the changes in your work, relationships, or leisure activities caused by your health condition have been the most disruptive or unpleasant?

Follow-up: Which of the changes in your work, relationships, or leisure activities caused by your health condition have been the most disruptive or unpleasant? Follow-up: Which changes have been harder for you, the changes you have been forced to make in the things you're expected to do or those changes you have made in things you do just for enjoyment?

Follow-up: Which changes have been harder for you, the changes you have been forced to make in the things you're expected to do or those changes you have made in things you do just for enjoyment? Follow-up: What has made one kind of change harder than the other?

Follow-up: What has made one kind of change harder than the other?

-

[Other health impacts]

We have just discussed a number of ways that your chronic health conditions have affected your lives. In the past 30 days, have those health conditions limited any of you in areas other than those we discussed today? If so, how?

-

[Time frame – 30 days vs. 7 days]

We have just discussed a number of ways that chronic health conditions have affected your life over the past 30 days. If we had asked you about the impact of chronic health conditions on your life over the past 7 days, how would your responses have been different?

-

[Close]

We are coming to the end of this session. I have asked you a lot of questions about how chronic illnesses affect your lives. What other questions, if any, should we be asking?

Follow-up: And, finally, what final thoughts or comments would you like to add before we close?

Follow-up: And, finally, what final thoughts or comments would you like to add before we close?

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions: LC, RD, DD, DI, and KW conceived of and designed the study. LC, DI, AS, and KW conducted the data collection. HB, LC, DD, EH, SE, MK, DI, AS, JM, and KW carried out analysis and interpretation. LC created the initial draft of the article. HB, RD, DD, EH, SE, DI, MK, AS, JM, and KW aided in subsequent drafting and critical revision. DD and RD obtained funding. LC held overall responsibility for this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims (DRAFT). US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER); Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) [Accessed December 18, 2007];2006 February; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/CDER/GUIDANCE/5460dft.pdf.

- 2.Cella D, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, et al. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birchwood M, Smith J, et al. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkers MP, Whiteneck G, et al. Measures of social outcomes in disability research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(12 Suppl 2):S63–80. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisen SV, Normand SLT, et al. BASIS-32 and the Revised Behavioral Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-R) In: Maruish M, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 759–790. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, et al. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):885–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(9):1111–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO DAS II) Interviewer's training manual. Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S, Syme SL. Issues in the study and application of social support. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social Support and Health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc.; 1985. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCampbell C, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science. 1993;9(3):458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn E, Cella D, et al. Social Well-being: The forgotten health status measure. Quality of Life Research. 1991;14(9) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis E, Redmond R. Focus groups in nursing research. Nurse Res. 2007;14(2):25–37. doi: 10.7748/nr2007.01.14.2.25.c6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger R. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (2nd ed) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan D. Focus groups as qualitative research. Qualitative research methods volume 16. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan D, editor. Successful focus groups: advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart D, Shamdasani P, et al. Focus groups: theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender D, Ewbank D. The focus group as a tool for health research: Issues in design and analysis. Health Transition Review. 1994;4(1):63–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhr T. User's Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. GmbH, Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey JW, Morgan M, et al. Intercoder Agreement in Analysis of Responses to Open-Ended Interview Questions: Examples from Tuberculosis Research. Field Methods. 1996;8(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorden RL. Basic Interviewing Skills. Long Grove: Waveland Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kupper LL, Hafner KB. On assessing interrater agreement for multiple attribute responses. Biometrics. 1989;45(3):957–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrald MM, Herrald MM, et al. Pet ownership predicts adherence to cardiovascular rehabilitation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32(6):1107–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frost MH, Reeve BB, et al. What is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures? Value Health. 2007;10 2:S94–S105. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ustun T, Chatterji S, et al., editors. Disability and Culture: Universalism and Diversity. Gottingen: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]